Abstract

Citrus black spot (CBS) and post-bloom fruit drop (PFD), caused by Phyllosticta citricarpa and Colletotrichum abscissum, respectively, are two important citrus diseases worldwide. CBS depreciates the market value and prevents exportation of citrus fruits to Europe. PFD under favorable climatic conditions can cause the abscission of flowers, thereby reducing citrus production by 80%. An ecofriendly alternative to control plant diseases is the use of endophytic microorganisms, or secondary metabolites produced by them. Strain LGMF1631, close related to Diaporthe cf. heveae 1, was isolated from the medicinal plant Stryphnodendron adstringens, and showed significant antimicrobial activity, in a previously study. In view of the potential presented by strain LGMF1631, and the absence of chemical data for secondary metabolites produced by D. cf. heveae, we decided to characterize the compounds produced by strain LGMF1631. Based on ITS, TEF1 and TUB phylogenetic analysis, strain LGMF1631 was confirmed to belong to D. cf. heveae 1. Chemical assessment of the fungal strain LGMF1631 revealed one new seco-dihydroisocoumarin [cladosporin B (1)] along with six other related, already known dihydroisocoumarin derivatives and one monoterpene [(–)-(1S,2R,3S,4R)-p-menthane-1,2,3-triol (8)]. Among the isolated metabolites, compound 5 drastically reduced the growth of both phytopathogens in vitro, and completely inhibited the development of CBS and PFD in citrus fruits and flowers. In addition, compound 5 did not show toxicity against human cancer cell lines or citrus leaves, at concentrations higher than used for the inhibition of the phytopathogens, suggesting the potential use of (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) to control citrus diseases.

Keywords: Phyllosticta citricarpa, Colletotrichum abscissum, Postbloom fruit drop, Citrus black spot

Introduction

Endophytic fungi comprise a heterogeneous and diverse group of species that colonizes interior organs of plants for part of their life without causing any negative effects on the host plant (Chutulo & Chalannavar, 2018). The long relationship of endophytes with medicinal plants may result in sharing metabolic pathways, thereby influencing the endophytes’ natural bioactivity (Chithra et al., 2014) and secondary metabolites (Masi et al., 2018). Among endophytes, Diaporthe represents the most common genus in several plants (Ferreira et al., 2015; dos Santos et al., 2016; Hokama et al., 2017; Ferreira et al., 2017). This genus is widely distributed, with broad host ranges (Gomes et al., 2013), and great biotechnological potential as a producer of secondary metabolites with antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxic and biological control abilities (Santos et al., 2016; Tonial et al., 2017; Tanapichatsakul et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2018; de Medeiros et al., 2018).

Several Diaporthe species (such as D. helianthi, D. miriciae, D. terebinthifolii) have been reported to produce bioactive secondary metabolites (Specian et al., 2012; Carvalho et al., 2018; de Medeiros et al., 2018). However, no studies were reported so far about the metabolites produced by the species Diaporthe cf. heveae. D. cf. heveae, originally isolated from the Brazilian medicinal plant Hevea brasiliensis (Gomes et al., 2013), and commonly used for extraction of milky latex, which is the primary source of natural rubber (Mooibroek & Cornish, 2000).

In a previous study performed by our research group, one isolate, close related to D. cf. heveae 1, strain LGMF1631, showed great activity against the citrus phytopathogens Colletotrichum abscissum and Phyllosticta citricarpa (Noriler et al., 2018). C. abscissum is the epidemiological agent of post-bloom fruit drop (PFD) (Silva et al., 2017), and in favorable climatic conditions, commonly observed when rainy days coincide with the bloom period, PFD drastically reduces citrus production (Lima et al., 2011). P. citricarpa causes citrus black spot (CBS) disease in Brazil. It is controlled applying carbendazim and/or strobilurins (Baldassari et al., 2006), however this compounds only decrease the disease incidence, not eliminate the fungus. Therefore, the use of secondary metabolites produced by endophytes active against both diseases (PFD and CBS), could be a more ecofriendly alternative to control these phytopathogens and reduce the usage of fungicides in citrus orchards (Santos et al., 2016; Noriler et al., 2018).

In this context, we have decided to scale-up and characterize the secondary metabolites produced by strain LGMF1631, and evaluated the isolated pure compounds for their ability to inhibit the development of the two major citrus fungal pathogens (C. abscissum and P. citricarpa) in vitro and in plant tissues.

Material and Methods

Organisms and media

The fungus LGMF1631 was isolated from the leaves of Stryphnodendron adstringens in 2016 (Noriler et al., 2018) and it has been deposited in the culture collection of Microbiological culture collection of Paraná State, deposit number CMRP3912. Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, IBI Scientific) media was used for the maintenance of strains LGMF1631, Phyllosticta citricarpa LGMF06 (isolated from Citrus sp. with positive results in CBS pathogenicity tests according to Baldassari et al. 2007) and Colletotrichum abscissum CA142 (isolated from PFD lesions according to Silva et al. 2017). The strains are deposited in the Microbiological culture collection of the Rede Paranaense de Coleções Biológicas - Taxonline (http://taxonline.bio.br/colecoes/index.php?id=2-coleçõesmicrobiológicas). Malt Extract Broth (MEB, 20 g of malt extract, 1 g of peptone and 20 g of glucose per liter) culture media was used for the fermentation.

Species identification using multi-locus analysis

Strain LGMF1631 was cultivated on PDA for 3 days at 28 °C, and genomic DNA extraction was performed according to Raeder and Broda (1985). The internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) region was amplified using the primers V9G (De Hoog & Gerrits Van Den Ende, 1998_S1_Reference19) and ITS4 (White et al., 1990), primers EF1–728F and EF1–986R (Carbone & Kohn, 1999) were used to amplify part of the translation elongation factor 1-α gene (TEF1) and primers T1 (O’Donnell & Cigelnik, 1997) and Bt-2b (Glass & Donaldson, 1995) were used to amplify part of the β-tubulin gene (TUB). DNA sequences were obtained on an ABI Prism 3500 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Chromatograms were inspected using MEGA 7 software (Kumar et al., 2015) and BioEdit 7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999). The phylogenetic analysis was performed as described by Noriler et al. (2018) using sequences from the available type strains of Diaporthe genus, deposited in the MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org/). Sequences obtained were deposited in GenBank, access codes: MK007529 (TEF1), MK007530 (TUB) and MG976433 (ITS).

Scale-up fermentation and secondary metabolites isolation

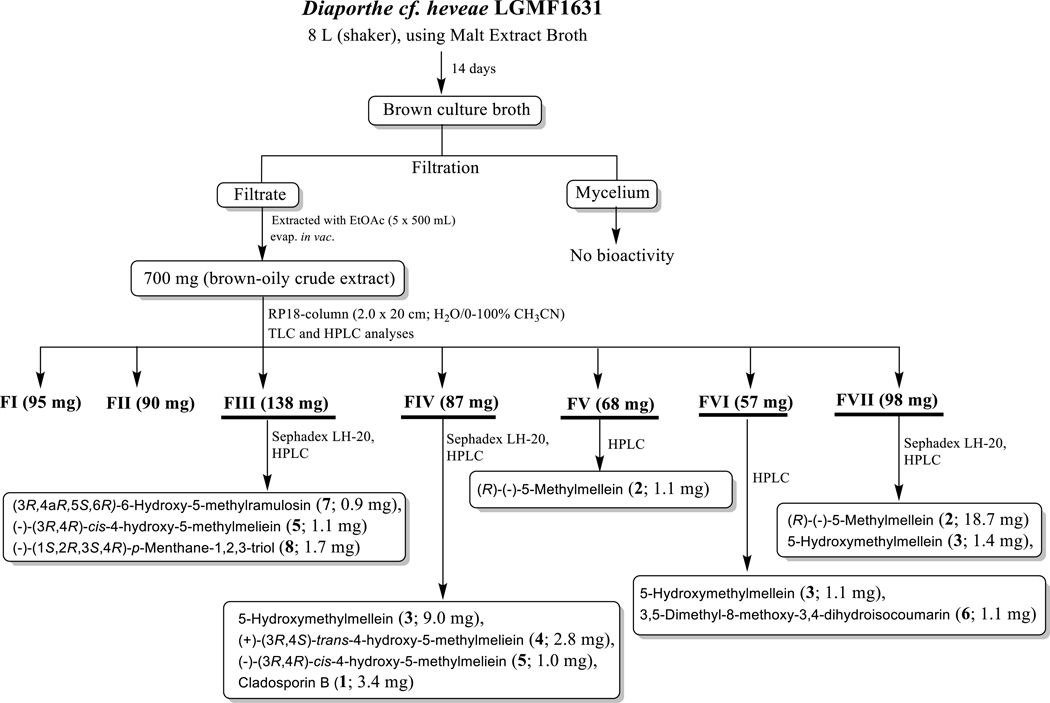

As depicted in figure 1, strain LGMF1631 was cultivated in PDA at 28 ºC for 3 days. The fully grown agar plate of strain LGMF1631 was cut into 8 mm plugs, and 5 plugs were used to inoculate each of the 32 Erlenmeyer flasks (500 mL) containing 250 mL of MEB medium. Fermentation (8 L) was continued at 28 ºC for 14 days on rotary shaker (120 rpm). The obtained brown culture broth was filtered-off on Whatman no. 4, and the mycelium was discarded, since it has no antifungal activity. The supernatant was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 x v/v) and the recovered organics were evaporated in vacuo at 40 °C to yield 700 mg of brown-oil crude extract. The crude extract was subjected to a Reverse Phase C18 column chromatography (20 × 2.0 cm, 250g) eluted with a gradient of H2O - CH3CN (100:0 – 0:100), followed by TLC and HPLC analysis to produce seven fractions (FI–FVII). Purification of fractions FIII–VII using Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH; 1 × 20 cm) and HPLC yielded compounds 1 (3.4, pale-yellow solid), 2 (19.8 mg, pale-yellow solid), 3 (11.5 mg, pale-yellow solid), 4 (2.8 mg, pale-yellow solid), 5 (2.1 mg, pale-yellow solid), 6 (1.1 mg, pale-yellow solid), 7 (0.9 mg, colorless solid) and 8 (1.7 mg, colorless solid) in pure forms. Finally, fractions FI and FII were discarded based on TLC and HPLC analyses, since they contained only sugars and other media components, with no biological activity (Figure 1, and see Supporting Information for the physicochemical properties of compounds 1–8).

Figure 1.

Work-up scheme of the metabolites produced by the fungus Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631

NMR spectra were recorded on Varian (Palo Alto, CA) Vnmr 400 (1H, 400 MHz; 13C, 100 MHz) spectrometer, δ-values were referenced to the respective solvent signals [CD3OD, δH 3.31 ppm, δC 49.15 ppm; DMSO-d6, δH 2.50 ppm, δC 39.51 ppm]. HPLC-MS analyses were accomplished using a Waters (Milford, MA) 2695 LC module (Waters Symmetry Anal C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm; solvent A: H2O/0.1% formic acid, solvent B: CH3CN/0.1% formic acid; flow rate: 0.5 mL min−1; 0–4 min, 10% B; 4–22 min, 10–100% B; 22–27 min, 100% B; 27–29 min, 100%−10% B; 29–30 min, 10 % B). HPLC analyses were performed on an Agilent 1260 system equipped with a photodiode array detector (PDA) and a Phenomenex C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Semi-preparative HPLC was accomplished using Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) C18 column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) on a Varian (Palo Alto, CA) ProStar Model 210 equipped with a photodiode array detector and a gradient elution profile (solvent A: H2O, solvent B: CH3CN; flow rate: 5.0 mL min−1; 0–2 min, 25% B; 2–15 min, 25–100% B; 15–17 min, 100% B; 17–18 min, 100%−25% B; 18–19 min, 25% B). Size exclusion chromatography was performed on Sephadex LH-20 (25–100 μm; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (PTLC). All solvents used were of ACS grade and purchased from the Pharmco-AAPER (Brookfield, CT).

Antifungal analysis against the citrus pathogens P. citricarpa and C. abscissum

In vitro analysis

The antifungal activity of compounds 1-8 was evaluated by spread 100 μg of each compound over the surface of Petri dish containing PDA medium, and one mycelial disc of each phytopathogen was inoculated in the center of the plates. The fungicide carbendazim (1.0 mg/mL) was used as positive control and methanol as the negative control. Plates were incubated in BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) at 28 °C. The antifungal activity was evaluated after 7 days in the experiment using C. abscissum (CA142) and after 21 days in the experiment using P. citricarpa (LGMF06). The growth inhibition was determined by comparing the diameter of the colony in the presence of treatment with controls (Savi et al., 2015). The experiment was performed in triplicate and the data were submitted to analysis of parametric variance (ANOVA) in GraphPad Prims v. 6.01.

Inhibition of citrus black spot (CBS) development in citrus fruits

For this analysis detached Citrus sinensis fruits were used. The mycelium of P. citricarpa was introduced in the fruit through a wound with a cutting drill, and 10 μg of each compound was added to the wounds. The wound was sealed with tape and maintained in a light chamber at 28 ºC, applying continuous light. The qualitative activity was evaluated after 21 days of incubation, comparing the development of lesions in the treatments with the negative control (only the phytopathogen) and the positive control (with 50 μg of the fungicide carbendazim).

Inhibition of post-bloom fruit drop (PFD) development in citrus flowers

Citrus flowers were obtained from citrus plants, without PFD symptoms, located at University Federal of Paraná, Brazil. A 5 μL of C. abscissum spore solution (108 spores/mL) and 5 μg of isolated compounds were inoculated in each flower. The inoculated flowers were deposited in transparent plastic boxes (volume of 500 ml, r = 5.5 cm, h = 8 cm) containing water-agar medium (15 grams of agar per 1 L of deionized H2O), incubated at room temperature and analyzed after 24, 36 and 48 hours of inoculation (protocol adapted from Agostini et al., 1992). A positive control consisted of inoculation only the spore solution, and as a negative control was established by inoculation of 10 μL saline solution. In addition, we used a fungicide control (inoculation of 10 μg of carbendazim). Five flowers were used in each treatment.

Toxicity of compounds

Cytotoxicity against human cancer cells

Mammalian cell line cytotoxicity [A549 (non-small cell lung) and PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines from American Type Culture Collection] assays were accomplished in triplicate following our previously reported protocols (Shaaban et al., 2014; Shaaban et al., 2015; Shaaban et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017, Savi et al., 2018, Abbas et al., 2018). To assay the viability of human lung non-small cell carcinoma A549 and prostate adenocarcinoma PC3 cell against compounds 1–8 (Figure 5), the conversion of resazurin (7-hydroxy-10-oxido-phenoxazin-10ium-3-one) to its fluorescent product resorufin was monitored. DMEM/F-12 Kaighn’s modification media (Life Technologies, NY, USA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL, streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine was used to grow A549 and PC3 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in 96-well clear bottom culture plates (Corning, NY, USA), incubated 24 hours at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and subsequently exposed to known toxins (1.5 mM hydrogen peroxide or 10 μg/mL actinomycin D, positive controls) and the test compounds for 72 hours. To assess cell viability, 150 μM of resazurin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well, plates were shaken briefly for 10 seconds and incubated for another 3 hours at 37 °C to allow viable cells to convert resazurin into resorufin. The fluorescence intensity for resorufin was detected on a scanning microplate spectrofluorometer FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA) using an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm.

Figure 5.

Viability of A549 (non-small cell lung cancer) and PC3 (prostate cancer) human cell lines at 100 μM of compounds 1–8 assessed by the conversion of resazurin to its fluorescent product resorufin.

Phytotoxicity in citrus leaves

For phytotoxicity analysis, the leaf disks were collected from intact mature leaves of Citrus sinensis and placed on Petri dishes containing water-agar medium. 10 μg and 20 μg of compound that showed the best antifungal activity against both phytopathogens were applied onto the leaf disks. A 30 μL sample of 10% lactic acid was used as the positive control, and 30 μL of methanol was used as the negative control. Incubation was carried out at 24 °C for approximately 48 h.

Results

Species identification

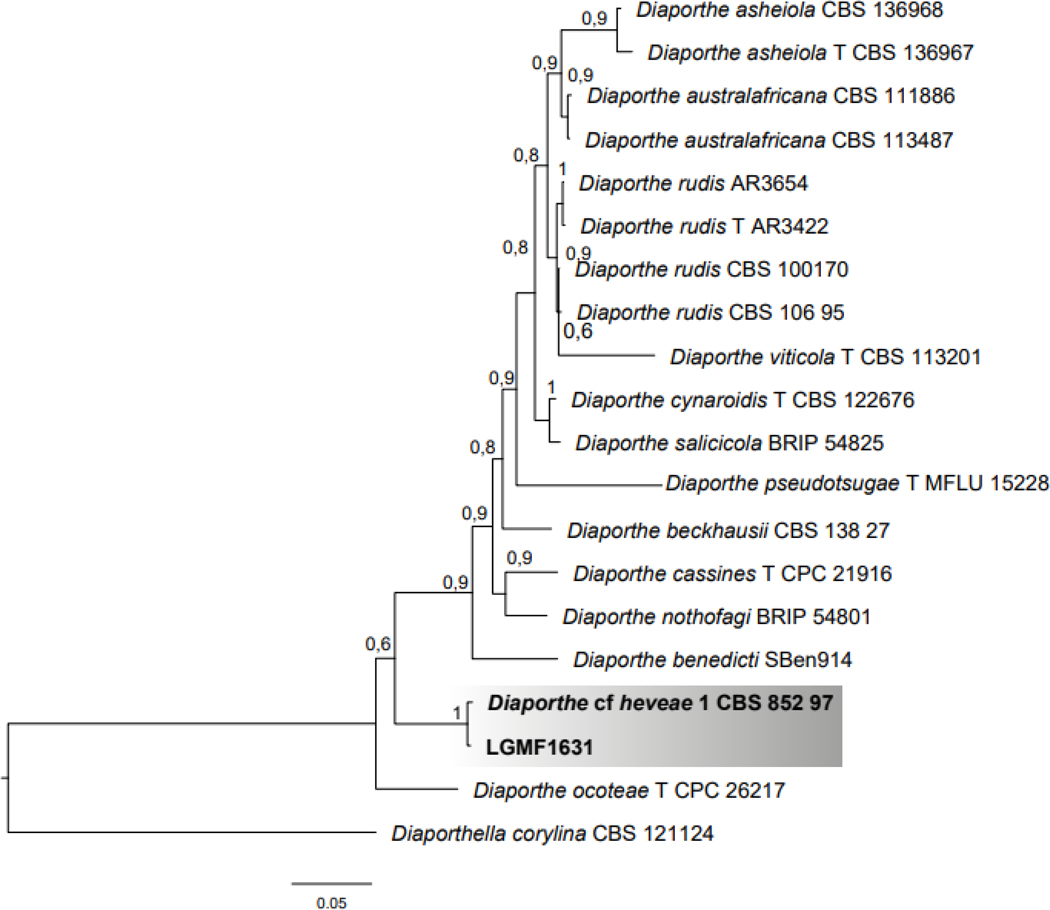

For species identification we used a multilocus analysis comprising 2305 pb of ITS, TEF1 and TUB sequences. The Bayesian phylogenetic analysis showed strain LGMF1631 in clade 1 (Supporting Information, Figure S1) composed by 12 Diaporthe species, and on the same branch Diaporthe cf. heveae (CBS852.97) is located (Identities = 1952/1961), and sharing 99.5% sequence similarity (Figure 2). Thus, isolate LGMF1631 was confirmed as belonging to the Diaporthe cf. heveae species.

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of the combined ITS+TUB+TEF1 regions of Diaporthe species belonging to Clade 1 (Sup. Inf. Figure S1) and strain LGMF1631. The species Diaporthella corylina was used as outgroup. Values on the node indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities. Bar indicates 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Secondary metabolites produced by Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631

Scale-up fermentation, isolation and purification

As summarized in Figure 1, scale-up fermentation (8 L) of strain LGMF1631 using malt extract broth, followed by extraction afforded 700 mg of brown-oil crude extract. This crude extract (700 mg) was subjected to reverse phase C18-column chromatography, followed by Sephadex LH-20 and HPLC purification to provide compounds 1–8 in pure form (Figure 1).

Structure elucidation

The physico-chemical properties of compounds 1–8 are summarized in the Supporting Information. The chemical structures of the known compounds 2-8 (Figure 1) were determined by 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (MS) data analyses (Supporting Information, Tables S1–3 and Figures S2-S3), and by comparison with literature data. Compounds 2-8 were identified and established as 5-methylmellein (2), 5-hydroxymethylmellein (3), (+)-(3R,4S)-trans-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (4), (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5), 3,5-dimethyl-8-methoxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (6), (3R,4aR,5S,6R)-6-hydroxy-5-methylramulosin (7) and (–)-(1S,2R,3S,4R)-p-menthane-1,2,3-triol (8). Compounds 2-7 are dihydroisocoumarinderived molecules, however compound 8 is a monoterpene-derived natural product (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of compounds 1-8 isolated from Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631, and cladosporin.

Compound 1 was isolated as pale-yellow solid using standard chromatographic techniques as depicted in Figure 1. The UV spectrum of 1 (λmax 220, 254, 312 nm) suggested the presence of the same chromophore as in compounds 2-6 (Supporting Information; Figure S4, S19, S29, S38, S47 and S53). The molecular formula of 1 was deduced as C16H24O5 on the basis of (‒)-HRESI-MS (m/z 295.1542 [M – H]‒; calcd for C16H23O5, 295.1550) and NMR. The proton NMR data of 1 in DMSO-d6 and CD3OD (Supporting Information, Table S2) revealed an array of aliphatic proton signals and one additional aromatic signal at δ 5.89 (s, 2H). In addition, one proton singlet observed at δ 14.55 (s, 1H) suggested the presence of one chelated hydroxy group with a carbonyl carbon (-CO-). The 13C NMR/HSQC spectra of 1 (Supporting Information, Table S1) displayed 16 signals corresponding to one methyl, seven methylene, three methine and five carbons. In addition, 13C NMR highlighted the presence of a carboxylic acid/or carboxamide and two singlet proton signals [δ 5.89 (s, 2H), δC 105.8] in conjunction with four aromatic carbon signals [δC 143.5, 102.9, 161.9, 161.9], one methylene carbon [δH 2.35 (dd, 13.1, 6.3), 2.46 (dd, 13.0, 6.5); δC 44.5] and one oxy-methine [δH 3.57 (m); δC 70.8] further confirmed the presence of a dihydroisocoumarin chromophore (as in compounds 2-6) in 1. Comparison with compounds 2-6 (Supporting Information, Tables S1 and 2), and analyses of the 1H,1H-COSY/TOCSY/NOESY/HMBC spectra of 1 (Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S2) revealed that the doublet methyl signal observed in compounds 2-6 (3-CH3) is replaced in compound 1 by a heptyl side chain at 3-position [-(CH2)6CH3]. In addition, the upfield chemical shift of the oxymethine carbon (δC 70.8) as well as the missing 3J HMBC correlation from CH-3 (δH 3.57) to C-1 (δC 173.8) indicated the absence of the lactone ring (of compounds 2-6) and instead the presence of a free acid (-COOH) at 8a-position of compound 1. Key 3J/2J HMBC correlations [anomeric proton signal (H-5, δ 5.89) to C-4 (δ 44.5), C-8a (δ 102.9) and CH-7 (δ 105.8); CH2-4 (δ 2.35/2.46 to CH-3 (δC 70.8), CH2-9 (δC 36.4), CH-5 (δC 105.8), and C-8a (δC 102.9); CH3-15 (δH 0.84) to CH2-14 (δC 22.1) and CH2-13 (δC 31.3); Supporting Information, Figure S2] confirmed the dihydroxy-benzoic acid chromphore and with a heptyl side chain at 3-position (Supporting Information, Figure S2, and Tables S1 and S2]. Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of 1 to that of the closely-related analogues 2–6 revealed a common aromatic core with major structural divergence at the 3-position (3-methyl in 2-6 versus an 3-heptyl in 1; lactone in 2-6 versus free acid in 1; the absence of 5-methyl/methylene group of 2-6 in 1; Tables S1 and S2). All of the remaining HMBC correlations (Supporting Information, Figure S2) and NMR data (Supporting Information, Tables S1 and S2) are supportive of structure 1. In summary, analyses of 1D (1H, 13C) and 2D (HSQC, 1H,1H-COSY, TOCSY, HMBC and NOESY) NMR and comparison with the data of compounds 2-6, the structure of 1 (Figures 1; Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S3) was established as a new seco-cladosporin analogue, and 1 was subsequently named cladosporin B.

Antifungal analysis against P. citricarpa and C. abscissum

In vitro analysis

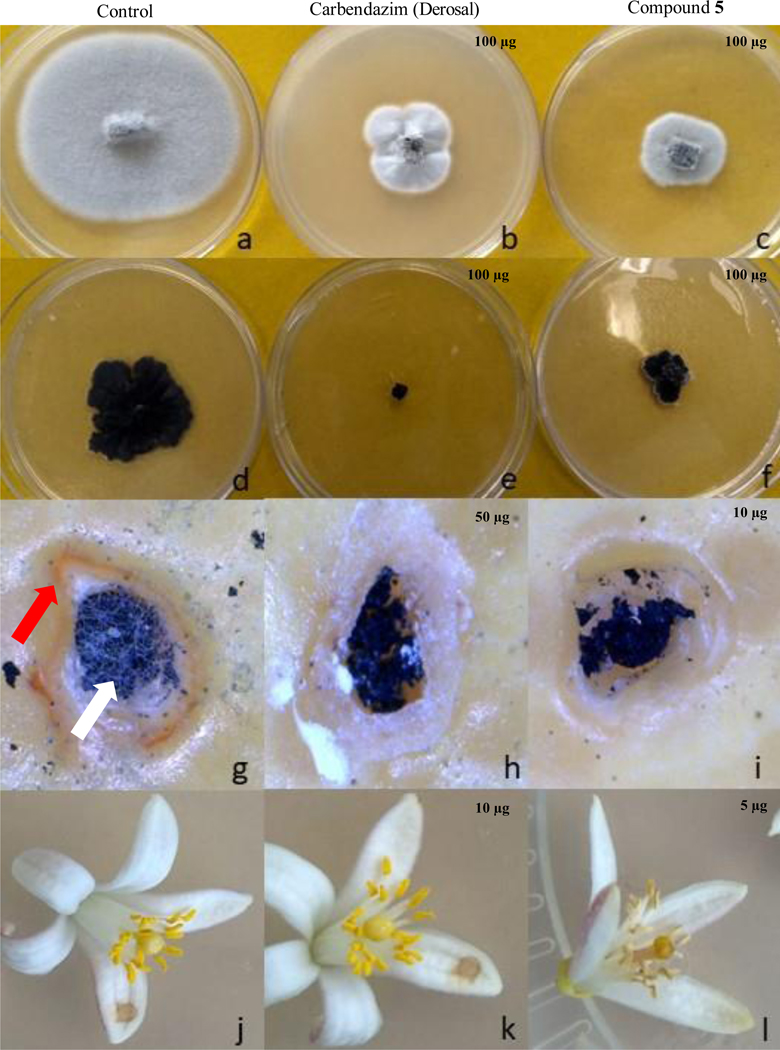

The antifungal ability of compounds 1–8 to inhibit the development of two important citrus pathogens, P. citricarpa and C. abscissum, the causal agent of citrus black spot and post-bloom fruit drop, respectively, was evaluated (Table 1). In the screening in Petri dishes, 100 μg of compounds 3-5 and 7 inhibited P. citricarpa development, with lower growth rates in the present of (–)-(3R, 4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) (Table 1, Figure 4). Against C. abscissum, only compound 5 had significant inhibition of phytopathogen development (Table 1, Figure 4).

Table 1.

Growth (in cm) of the phytopathogens Phyllosticta citricarpa and Colletotrichum abscissum in petri dishes, and development of citrus black spot (CBS) and post-bloom fruit drop (PFD) symptoms in the presence of compounds 1–8 from Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631.

| Compounds |

Phyllosticta citricarpa |

Colletotrichum abscissum |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petri dishes | CBS symptoms | Petri dishes | PFD symptoms | |

| Cladosporin B (1) | 2.3 +/− 0.6 | NE | 5.6 +/− 0.3 | NE |

| 5-Methylmellein (2) | 3.0 +/− 0.25 | NE | 6.4 +/− 0.3 | NE |

| 5-Hydroxymethylmellein (3) | 2.1 +/− 0.3* | + | 5.8 +/− 0.4 | NE |

| (+)-(3R,4S)-trans-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (4) | 1.9 +/− 0.3* | - | 6.1 +/− 0.2 | NE |

| (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) | 1.2 +/− 0.1* | - | 2.4 +/− 0.1* | - |

| 3,5-Dimethyl-8-methoxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (6) | 2.2 +/− 0.5 | NE | 5.6 +/− 0.2 | NE |

| (3R,4aR,5S,6R)-6-Hydroxy-5-methylramulosin (7) | 1.5 +/− 0.1* | - | 6.3 +/− 0.1 | NE |

| (–)-(1S,2R,3S,4R)-p-Menthane-1,2,3-triol (8) | 2.8 +/− 0.25 | NE | 5.9 +/− 0.2 | NE |

| Carbendazim | 0* | - | 3.2 +/− 0.3* | + |

| Control with methanol | 3.3 +/− 0.2 | + | 5.7 +/− 0.2 | + |

samples that were significant in the reduction of growth compare to the control in the ANOVA, p < 0.001, - absence of symptoms, + presence of symptoms, NE not evaluated.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of Colletotrichum abscissum (a-c) and Phyllosticta citricarpa growth (d-f) and development of citrus black spot (g-i) and post-bloom fruit drop (j-l) symptoms by (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5). a, d, g and j) control with only the phytopathogen; b, e, h and k) treatment with carbendazim (derosal); c, f, i and l) treatment with (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5). Note: Red arrow: necrotic zone; White arrow: fungal growth.

In planta analysis

Inhibition of Citrus Black Spot in citrus fruits

Using detached citrus fruits, we evaluated the efficiency of compounds 3–5 and 7 to inhibit the CBS symptoms. (+)-(3R, 4S)-trans-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (4), (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) and (3R,4aR,5S,6R)-6-hydroxy-5-methylramulosin (7) completely inhibited CBS symptoms in different concentrations, such as 50 μg (Figure 4h) and 10 μg (Figure 4i), wherein only the residual mycelium that was used for fungal inoculation was observed, different from the positive control (Figure 4g) in which is possible to observe fungal growth and the necrotic zone around the lesion (Table 1, Figure 4g-i), characteristic of CBS lesion.

The application of 5-hydroxymethylmellein (3) did not inhibit P. citricarpa development and a small necrotic area around of the fungal inoculation was observed after 21 days of inoculation (Table 1). The remaining compounds were not evaluated because they did not show antifungal activity in the screening.

Inhibition of post-bloom fruit drop development in citrus flowers

The ability of compound 5 that showed great antifungal activity against C. abscissum, to inhibit the PFD development in citrus flowers was evaluated. Compounds 2-4 and 6 were not evaluated because they did not show activity in Petri dishes (Table 1). 5 μg of (–)-(3R, 4R)-cis-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) completely inhibit the fungal growth and PFD symptoms in flowers (Figure 4-l), different from the treatment with the fungicide carbendazim that reduced, but not eliminated the fungal development (Figure 4-k).

Toxicity of compounds

None of the isolated compounds (1-8) produced by strain LGMF1631 showed significant toxicity (less than 50% of cell growth) to human cell lines A549 and PC3 at high concentration as 100 μM (Figure 5), and only two compounds stimulated the PC3 cell growth (compounds 1 and 7). In addition, compound 5 did not display phytotoxicity to citrus leaves when deposited in the surface of leaf at concentrations higher than required to inhibit CBS and PFD symptoms development, 20 μg (Figure 6), in comparison with an acid lactic solution (10%) that produced a brown necrotic area in the leaf.

Figure 6.

Phytotoxicity in Citrus sinensis leaf disks at 10 and 20 μg of (-)-(3R, 4R)-cis-4hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) [c+: 30 μL of 10% lactic acid]

Discussion

Strain LGMF1631 was isolated during our screening program about biodiversity and bioprospecting of endophytes of the medicinal plant S. adstringens, present in Brazil (Noriler et al., 2018). Extracts from LGMF1631 showed promising results in antimicrobial screenings (Noriler et al., 2018), and the strain was selected herein to expand the potential as a producer of bioactive secondary metabolites.

Based on multilocus analysis strain was identified as Diaporthe cf. heveae, species described in 2013 by Gomes et al., as an endophyte of Hevea brasiliensis. Since then, D. cf heveae has been isolated only twice, from the ant Atta cephalotes (Reis et al., 2015) and the Glycine max soybean (Fernandes et al., 2015) in Brazil. Due to the low distribution and frequency of isolation, there was no report on the production of bioactive secondary metabolites by D. cf heveae and its metabolic potential remained unknown. Therefore, we decided to characterize the major compounds produced by strain LGMF1631.

Eight compounds were identified, compound 1 was established as a new seco-cladosporin analogue, named cladosporin B, compound 5-methylmellein (2) [a known metabolite of the almond pathogen Fusicoccum amygdali, Hypoxylon illitum, Numularia spp., Phomopsis oblonga, Semecarpus spp. of plants, Valsa ceratosperma and sterile mycelium derived from marine-derived green algae (Ballio et al., 1966; de Alvarenga et al., 1978; Carpenter et al., 1980; Anderson et al., 1983; Claydon et al., 1985; Okuno et al., 1986; El-Beih et al., 2007; Arora et al., 2017; Shigemoto et al., 2018)], 5-hydroxymethylmellein (3) [known metabolic product of Hypoxylon illitum and Valsa ceratosperma (Anderson et al., 1983; Okuno et al., 1986; El-Beih et al., 2007)], (+)-(3R, 4S)-trans-4-hydroxy5-methylmellein (4) and (–)-(3R, 4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) [both of compounds 4 and 5 were previously reported as the metabolic products of Valsa ceratosperma and the endophytic fungus Cytospora rhizophorae (Okuno et al., 1986, El-Beih et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2017)], 3,5-dimethyl-8-methoxy-3,4-dihydroisocoumarin (6) [previously produced by the fungus Cytospora eucalypticola (Kokubun et al., 2003)], (3R, 4aR, 5S, 6R)-6-hydroxy-5methylramulosin (7) [known metabolic product of the sterile mycelium fugus derived from the marine-derived green alga Codium fragile (El-Beih et al., 2007)], and (–)-(1S, 2R, 3S, 4R)-p-menthane-1,2,3-triol (8) [previously reported from the fungus Phomopsis amygdali (Sassa et al., 2003)]. Compounds 2-7 are dihydroisocoumarin-derived molecules, however compound 8 is a monoterpene-derived natural product (Figure 3).

An AntiBase 2017 (Laatsch, 2017) query revealed that nearly 200 isocoumarin/dihydroisocoumarin derivatives were reported from microorganisms (mainly from fungi and bacteria), of which only about 30 were cladosporin/asperentin-related fungal metabolites. These includes cladosporin [Figure 1, produced by Cladosporium cladosporioides, Aspergillus flavus, Eurotium glabrum and other spp. (Scott et al., 1971; Anke & Zahner, 1978; Reese et al., 1988; Wang et al., 2016; Cochrane et al., 2016)], isocladosporin [produced by Cladosporium cladosporioides (Jacyno et al., 1993)], the asperentins [produced by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus sydowii, Aspergillus sp. F00785 (Grove, 1972; Kimura et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2014; Wiese et al., 2017)], the monocerins [produced by Helminthosporium monoceras, Fusarium lavarum, endophytic Exserohilum rostratum, Readeriella mirabilis (Aldridge & Turner, 1970; Scott et al., 1984; Sappapan et al., 2008)] and the fusarentins [produced by Fusarium larvarum (Grove & Pople, 1979)]. This highlights 1 as the first example of a seco-lactone cladosporin-class of metabolites. Isocoumarins/Dihydroisocoumarins (3,4-dihydroisocoumarin) scaffolds are lactone containing natural products [consisting of a six-membered oxygen heterocycle (pyranone) and one benzene ring; 1H-2-Benzopyran-1-one], abundant in microbes and higher plants including endophytic and pathogenic fungi (Okuno et al., 1986; Evidente et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017; Elias et al., 2018, de Medeiros et al., 2018). These molecules were reported having a broad range of biological activities including anticancer, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antimalarial and fungicidal potential (Hussain & Green, 2017).

In view of absence of data about isocoumarins/dihydroisocoumarins as possible biological controllers for CBS and PFD, and the necessity of alternatives to decrease the impact of fungicide applications in the field, we decided to evaluate the potential of isocoumarins to control the development of P. citricarpa and C. abscissum in citrus fruits and flowers.

Compound 5 inhibited both phytopathogens, P. citricarpa and C. abscissum, in vitro and in vivo. (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-Hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) was originally isolated from an apple phytopathogen (Valsa ceratosperma) with low toxicity in apple fruits, different from the isomer (+)-(3R,4S)-trans-4-hydroxy-5methylmellein (4), also produced by V. ceratosperma, that showed the highest impact in the host (Okuno et al., 1986). Compound 5 was also isolated from a marine and an endophytic sterile fungus (El-Beih et al., 2007; Hussain et al., 2009); however, none of these studies explored the biotechnological aspects of this compound. Therefore we have reported herein for the first time the antifungal potential of (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5).

The ability of 5 into inhibit the development of P. citricarpa in citrus fruits suggest that this compound could be used for CBS control, especially since carbendazim was banned in the United States (U.S. EPA, 2012), and anti-resistance strategies recommend the use of strobilurins only in one third of the total fungicide applications (Miles et al., 2004; Dewdney et al., 2016). In addition, despite the efficiency of fungicides to control PFD, outbreaks were described in favorable climatic conditions, reducing 80% of the production (Lima et al., 2011). In this scenario, recent studies have been suggesting that the natural metabolites produced by endophytes can be one alternative to control PFD during conditions that result in the outbreaks (Klein et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2016; Che et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). Since (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) completely inhibited the development of C. abscissum in flowers at low dose (as 5 μg), the use of D. cf. heveae LGMF1631 may be an environmentally safe alternative to help to control PFD and other citrus diseases, thereby reducing the use of fungicides (Klein et al., 2016; Tonial et al., 2017; Noriler et al., 2018). However, it is important that the active compounds did not cause any damage to the plant host or human cells (Félix et al., 2018). Compound 5 did not show significant toxicity to human cell lines A549 and PC3 (lower than 50%) at high concentration as 100 μM, much more than required for the inhibition of CBS and PFD development (Figure 5). In addition, compound 5 did not display phytotoxicity to citrus leaves, even at concentrations higher than required to inhibit CBS and PFD symptoms development (10 and 5 μg), which suggests the potential use of (–)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (5) to be used in the control of CBS and PFD diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the College of Pharmacy NMR Center (University of Kentucky) for NMR support.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R24 OD21479 (JST), the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001998 and UL1TR000117). Additional support came from NIH grants CA 91091, GM 105977 and an Endowed University Professorship in Pharmacy to J.R. It was also supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - Brazil grant 424738/2016-3 and CNPq309971/2016-0 to C.G., and CAPES-Brazil - grant to D.C.S.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Agostini JP, Timmer LW, Mitchell DJ (1992) Morphological and pathological characteristics of strains of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides from Citrus. APSnet 82:1377–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas M, Elshahawi SI, Wang X, Ponomareva LV, Sajid I, Shaaban KA, Thorson JS 2018. Puromycins B-E, Naturally Occurring Amino-Nucleosides Produced by the Himalayan Isolate Streptomyces sp. PU-14G. J Nat Prod 81:2560–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge DC, Turner WB (1970) Metabolites of Helminthosporium monoceras: structures of monocerin and related benzopyrans. J Chem Soc Perkin 1:2598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Edwards RL, Whalley AJS (1983) Metabolites of the higher fungi. Part 21. 3-Methyl-3,4dihydroisocoumarins and related compounds from the ascomycete family xylariaceae. J Chern Soc Perkin Trans 1:2185–2192. [Google Scholar]

- Anke H, Zahner H (1978) Metabolic products of microorganisms. 170. On the antibiotic activity of cladosporin. Arch Microbiol 116:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora D, Kumar A, Gupta P, Chashoo G, Jaglan S (2017) Preparation, characterization and cytotoxic evaluation of bovine serum albumin nanoparticles encapsulating 5-methylmellein: A secondary metabolite isolated from Xylaria psidii. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 27:5126–5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari RB, Reis RF, Goes A (2006) Susceptibility of fruits of the ‘Valencia’ and ‘Natal’ sweet orange varieties to Guignardia citricarpa and the influence of the coexistence of healthy and symptomatic fruits. Fitopatol Brasil 31:337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari RB, Wickert E, Goes A (2007) Pathogenicity, colony morphology and diversity of isolates of Guignardia citricarpa and G. mangiferae isolated from Citrus spp. Eur J Plant Pathol 120:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ballio A, Barcellona S, Santurbano B (1966) 5-Methylmellein, a new natural dihydroisocoumarin. Tetrahedron Lett 7:3723–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM (1999) A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91:553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CR, Ferreira-da Silva A, Wedge DE, Cantrel CL, Rosa LH (2018) Antifungal activities of cytochalasins produced by Diaporthe miriciae, an endophytic fungus associated with tropical medicinal plants. Can J Microbiol 6:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RC, Sotheeswaran SS, Sultanbanwa MU, Balasubramaniam S (1980) (−)-5-Methylmellein and catechol derivatives from four Semecarpus species. Phytochemistry 19:445–447. [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Liu B, Liu G, Chen Q, Lan J (2017) Volatile organic compounds produced by Lysinibacillus sp. FJAT4748 possess antifungal activity against Colletotrichum acutatum. Biocontrol Sci Technol 27:1349–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Chithra S, Jasim B, Sachidanandan P, Jyothis M, Radhakrishnan EK (2014) Piperine production by endophytic fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides isolated from Piper nigrum. Phytomedicine 21: 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutulo EC, Chalannavar RK (2018) Endophytic mycoflora and their bioactive compounds from Azadiracha indica: a comprehensive review. J Fungi 4:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claydon N, Grove JF, Pople M (1985) Elm bark beetle boring and feeding deterrents from Phomopsis oblonga. Phytochemistry 24:937–943. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane RV, Sanichar R, Lambkin GR, Reiz B, Xu W, Tang Y, Vederas JC (2016) Production of New Cladosporin Analogues by Reconstitution of the Polyketide Synthases Responsible for the Biosynthesis of this Antimalarial Agent. Angew Chem Int Ed 55:664–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alvarenga MA, Fo RB, Gottlieb OR, de P Dias JP, Magalhães AF, Magalhães EG, de Magalhães GC, Magalhães MT, Maia JGS, Marques R, Marsaioli AJ, Mesquita AAL, de Moraes AA, de Oliveira AB, de Oliveira GG, Pedreira G, Pereira SK, Pinho SLV, Sant’ana AEG, Santos CC (1978) Dihydroisocoumarins and phthalide from wood samples infested by fungi. Phytochemistry 17:511–516. [Google Scholar]

- De Hoog GS, Gerrits van den Ende AH (1998) Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous Basidiomycetes. Mycoses 41:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros AG, Savi DC, Mitra P, Shaaban KV, Jha AK, Thorson JS, Rohr J, Glienke C (2018) Bioprospecting of Diaporthe terebinthifolii LGMF907 for antimicrobial compounds. Folia Microbiol 63:499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewdney MM, Schubert TS, Estes MR, Roberts PD, Peres NA (2016) Florida Citrus Pest Management Guide. eds. University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Services, Gainesville. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos TT, de Souza Leite T, de Queiroz CB, de Araújo EF, Pereira OL, de Queiroz MV (2016) High genetic variability in endophytic fungi from the genus Diaporthe isolated from common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Brazil. J Appl Microbiol 120:388–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Beih A, Kato H, Ohta T, Tsukamoto S (2007) (3R,4aR,5S,6R)-6-Hydroxy-5-methylramulosin: a new ramulosin derivative from a marine-derived sterile mycelium. Chem Pharm Bull 55:953–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias LM, Fortkampa D, Sartori SB, Ferreira MC, Gomes LH, Azevedo JL, Montayac QV, Rodrigues A, Ferreira AG, Lira SP (2018) The potential of compounds isolated from Xylaria spp. as antifungal agents against anthracnose. Braz J Microbiol 49:840–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evidente M, Cimmino A, Zonno MC, Mais M, Berestetskyi A, Santoro E, Superchi S, Vurro M, Evidente A (2015) Phytotoxins produced by Phoma chenopodiicola, a fungal pathogen of Chenopodium album. Phytochem 117:482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félix C, Salvatore MM, DellaGreca M, Meneses R, Duarte AS, Salvatore F, Naviglio D, Gallo M, Jorrín-Novo JV, Alves A, Andolfi A, Esteves AC (2018) Production of toxic metabolites by two strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae, isolated from a coconut tree and a human patient. Mycol 31:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes EG, Pereira OL, Silva CC, Bento CBP, Queiroz MV (2015) Diversity of endophytic fungi in Glycine max. Microbiol Res 181:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MC, Cantrell CL, Wedge DE, Gonçalves VN, Jacob MR, Khan S, Rosa CA, Rosa LH (2017) Antimycobacterial and antimalarial activities of endophytic fungi associated with the ancient and narrowly endemic neotropical plant Vellozia gigantean from Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 112:692–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MC, Vieira MLA, Zani CL, Alves TMA, Sales Junior PA, Murta SMF, Romanha AJ, Gil LHVG, Carvalho AGO, Zilli JE, Vital MJS, Rosa CA, Rosa LH (2015) Molecular phylogeny diversity, symbiosis and discover of bioactive compounds of endophytic fungi associated with the medicinal Amazonian plant Carapa guianensis Aublet (Meliaceae). Biochem Syst Ecol 59:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Glass NL, Donaldson G (1995) Development of primer sets designed for use with PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environm Microbiol 61:1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes RR, Glienke C, Videira SIR, Lombard L, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW (2013) Diaporthe: a genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Persoonia 31:1–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove JF (1972) New metabolic products of Aspergillus flavus. I. Asperentin, its methyl ethers, and 5’hydroxyasperentin. J Chem Soc Perkin 119: 2400–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove JF, Pople M (1979) Metabolic products of Fusarium larvarum fuckel. The fusarentins and the absolute configuration of monocerin. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1:2048–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Hall T (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids Symp. Ser 41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hokama Y, Savi DC, Assad B, Aluizio R, Gomes-Figueiredo J, Adamoski D, Possiede YM, Glienke C (2017) Endophytic fungi isolated from Vochysia divergens in the pantanal, Mato Grosso do Sul: diversity, phylogeny and biocontrol of Phyllosticta citricarpa, in Endophytic Fungi: Diversity, Characterization and Biocontrol, 4th Edn, ed Hughes E (Hauppauge, NY: Nova; ), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain H, Green IR (2017) A patent review of two fruitful decades (1997–2016) of Isocoumarin research. Expert Opin Ther Pat 27:1267–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain H, Krohn K, Draeger S, Meier K, Schulz B (2009) Bioactive Chemical Constituents of a Sterile Endophytic Fungus from Meliotus dentatus. Rec Nat Prod 3:114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jacyno JM, Harwood JS, Cutler HG, Lee MK (1993) Isocladosporin, a biologically active isomer of cladosporin from Cladosporium cladosporioides. J Nat Prod 56:1397–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MN, da Silva AC, Kupper KC (2016) Bacillus subtilis based-formulation for the control of postbloom fruit drop of citrus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MN, Silva AC, Lopes MR, Kupper KC (2013) Application of microorganisms, alone or in combination, to control postbloom fruit drop in citrus. Trop Plant Pathol 38:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Shimomura N, Tanigawa F, Fujioka S, Shimada A (2012) Plant growth activities of aspyran, asperentin, and its analogues produced by the fungus Aspergillus sp. Z Naturforsch C 67:587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokubun T, Veitch NC, Bridge PD, Simmonds MS (2003) Dihydroisocoumarins and a tetralone from Cytospora eucalypticola. Phytochemistry 62:779–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2015) MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laatsch H (2017) AntiBase: The natural compound identifier, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Lima WG, Spósito MB, Amorim L, Gonçalves FP, Filho PAM (2011) Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, a new causal agent of citrus post-bloom fruit drop. Eur J Plant Pathol 131:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Liu HX, Tan HB, Liu Y, Chen YC, Li SN, Sun ZH, Qiu SX, Zhang WM (2017) Three new highly-oxygenated metabolites from the endophytic fungus Cytospora rhizophorae A761. Fitoterapia 117:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Lin X, Tao H, Wang J, Li J, Yang B, Zhou X, Liu Y (2018) Isochromophilones A–F, Cytotoxic Chloroazaphilones from the Marine Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Diaporthe sp. SCSIO 41011. J Nat Prod 81:934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi M, Nocera P, Reveglia P, Cimmino A, Evidente A (2018) Fungal metabolites antagonists towards plant pests and human pathogens: structure-activity relationship studies. Molecules 23:834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles AK, Willingham ABSL, Cooke AW (2004) Field evaluation of strobilurins and a plant activator for the control of citrus black spot. Austral Plant Pathol 33:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Mooibroek H, Cornish K (2000) Alternative sources of natural rubber. Appl. Microbiol. Biotech 53, 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noriler SA, Savi DC, Aluizio R, Palácio-Cortes AM, Possiede YM, Glienke C (2018) Bioprospecting and structure of fungal endophyte communities found in the Brazilian, Pantanal, and Cerrado. Front Microbiol 9:1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E (1997) Two divergent intragenomic rDNAITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol Phylog Evol 7:103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno T, Oikawa S, Goto T, Saw Ai K, Shirahama H, Matsumoto T (1986) Structures and Phytotoxicity of Metabolites from Valsa ceratosperma. Agric Biol. Chem 50:997–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Raeder J, Broda P (1985) Rapid Preparation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Let Appl Microbiol 1:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Reese PB, Rawlings BJ, Ramer SE, Vederas JC (1988) Comparison of stereochemistry of fatty acid and cladosporin biosynthesis in Cladosporium cladosporioides using deuterium-decoupled proton, carbon-13 NMR shift correlation. J Am Chem Soc 110:316–318. [Google Scholar]

- Reis BMS, Silva A, Alvarez MR, Oliveira TB, Rodrigues A (2015) Fungal communities in gardens of the leafcutter and Atta cephalotes in forest and cabruca agrosystems of Southern Bahia state (Brazil). Fungal Biol 119:1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos PJ, Savi DC, Gomes RR, Goulin EH, da Costa Senkiv C, Tanaka FA, Almeida AM, Galli-Terasawa L, Kava V, Glienke C (2016) Diaporthe endophytica and D. terebinthifolii from medicinal plants for biological control of Phyllosticta citricarpa. Microbiol Res 186:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savi DC, Haminiuk CWI, Sora GTS, Adamoski DM, Kensiki J, Winnischofer SMB, Galli-Terasawa LV, Kava V, Glienke C (2015) Antitumor, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of secondary metabolites extracted by endophytic actinomycetes isolated from Vochysia divergens. Int J Pharm Chem Biol Sci 5:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Savi DC, Shaaban KA, Gos F, Ponomareva LV, Thorson JS, Glienke C, Rohr J (2018) Phaeophleospora vochysiae Savi & Glienke sp. nov. Isolated from Vochysia divergens Found in the Pantanal, Brazil, Produces Bioactive Secondary Metabolites. Sci Rep 8:3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappapan R, Sommit D, Ngamrojanavanich N, Pengpreecha S, Wiyakrutta S, Sriubolmas N, Pudhom K (2008) 11-Hydroxymonocerin from the plant endophytic fungus Exserohilum rostratum. J Nat Prod 71:1657–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa T, Kenmoku H, Sato M, Murayama T, Kato N (2003) (+)-Menthol and its hydroxy derivatives, novel fungal monoterpenols from the fusicoccin-producing fungi, Phomopsis amygdali F6a and Niigata 2. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott FE, Simpson TJ, Trimble LA, Vederas JC (1984) Biosynthesis of monocerin. Incorporation of 2H-, 13C-, and 18O-labelled acetates by Drechslera ravenelii. J Chem Soc Chem Commun 756–758. [Google Scholar]

- Scott PM, Van Walbeek W, MacLean WM (1971) Cladosporin, a new antifungal metabolite from Cladosporium cladosporioides. J Antibiot 24:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban KA, Elshahawi SI, Wang X, Horn J, Kharel MK, Leggas M, Thorson JS (2015) Cytotoxic Indolocarbazoles from Actinomadura melliaura ATCC 39691. J Nat Prod 78:1723–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban KA, Saunders MA, Zhang Y, Tran T, Elshahawi SI, Ponomareva LV, Wang X, Zhang J, Copley GC, Sunkara M, Kharel MK, Morris AJ, Hower JC, Tremblay MS, Prendergast MA, Thorson JS (2017) Spoxazomicin D and Oxachelin C, Potent Neuroprotective Carboxamides from an Appalachian Coal Fire-Associated Isolate Streptomyces sp. RM-14–6. J Nat Prod 80:2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban KA, Singh S, Elshahawi SI, Wang X, Ponomareva LV, Sunkara M, Copley GC, Hower JC, Morris AJ, Kharel MK, Thorson JS (2014) Venturicidin C, a new 20-membered macrolide produced by Streptomyces sp. TS-2–2. J Antibiot 67:223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Matsumoto T, Masuo S, Takaya N (2018) 5-Methylmellein is a novel inhibitor of fungal sirtuin and modulates fungal secondary metabolite production. J Gen Appl Microbiol 64:240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AO, Savi DC, Gomes FB, Gos FMWR, Silva GJ Jr, Glienke C (2017) Identification of Colletotrichum species associated with postbloom fruit drop in Brazil through GAPDH sequencing analysis and multiplex PCR. Eur J Plant Pathol 147:731–748. [Google Scholar]

- Specian V, Sarragiotto MH, Pamphile JA, Edmar C (2012) Chemical characterization of bioactive compounds from the endophytic fungus Diaporthe helianthi isolated from Luehea divaricata. Braz J Microbiol 43:11741182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanapichatsakul C, Monggoot S, Gentekaki E, Pripdeevech P (2018) Antibacterial and antioxidant metabolites of Diaporthe spp. isolated form flowers of Melodorum fruticosum. Curr Microbiol 75:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Guo K, Li XY, Zheng XY, Kong XJ, Zheng ZH, Xu QY, Deng X (2014) Three new asperentin derivatives from the algicolous fungus Aspergillus sp. F00785. Mar Drugs 12:5993–6002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonial F, Maia BHLNS, Sobottka AM, Savi DC, Vicente VA, Gomes RR, Glienke C (2017) Biological activity of Diaporthe terebinthifolii extracts against Phyllosticta citricarpa. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364, (doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx026). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (2012) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—risk assessment for safety of orange juice containing fungicide carbendazim, http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/factsheets/chemicals/carbendazim-fs.htm.

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee J, Taylor J (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, and White TJ (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wedge DE, Cutler SJ (2016) Chemical and Biological Study of Cladosporin, an Antimicrobial Inhibitor: A Review. Nat Prod Commun 11:1595–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang Y, Ponomareva LV, Qiu Q, Woodcock R, Elshahawi SI, Chen X, Zhou Z, Hatcher BE, Hower JC, Zhan C-G, Parkin S, Kharel MK, Voss SR, Shaaban KA, Thorson JS (2017) Mccrearamycins A-D, Geldanamycin-Derived Cyclopentenone Macrolactams from an Eastern Kentucky Abandoned Coal Mine Microbe. Angew Chem Int Ed 56:2994–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese J, Aldemir H, Schmaljohann R, Gulder TAM, Imhoff JF (2017) Asperentin B, a New Inhibitor of the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B. Mar Drugs 15:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.