Abstract

Background

Terlipressin (triglycyl lysine vasopressin) is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin, which has been used in the treatment of acute variceal haemorrhage. In contrast to vasopressin, terlipressin can be administered as intermittent injections instead of continuous intravenous infusion and it has a safer adverse reactions profile. However, its effectiveness remains uncertain.

Objectives

To determine if treatment with terlipressin improves outcome in acute oesophageal variceal haemorrhage and is safe.

Search methods

Randomized clinical trials were identified by searching the following databases (November 1999): The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register on The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 1999), MEDLINE, EMBASE, Biosis, and Current Contents. The bibliographies of identified publications were checked. Experts in the field and the manufacturers of terlipressin were contacted. For the update of this review, no new randomised clinical trials were identified on any of the databases (October 2002).

Selection criteria

All randomised clinical trials, which compared terlipressin with: (a) placebo or no treatment, (b) balloon tamponade, (c) endoscopic treatment, (d) octreotide, (e) somatostatin and (f) vasopressin, in the setting of acute variceal haemorrhage.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility, trial quality assessment and data extraction were done independently by two reviewers. The primary outcome measure was mortality. Secondary outcomes were failure of initial haemostasis, rebleeding, procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding, transfusion requirements and length of hospitalisation.

Main results

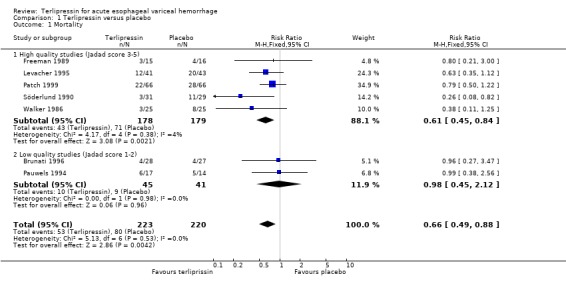

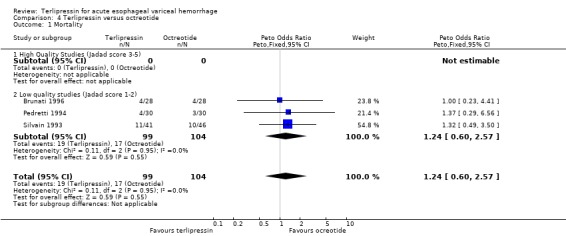

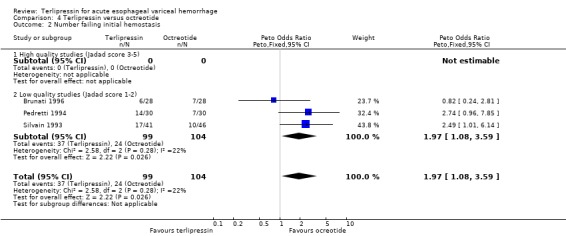

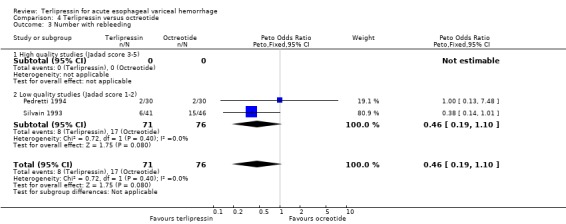

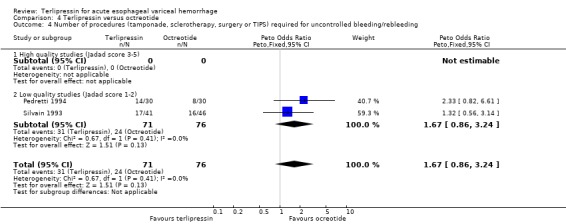

Twenty studies were identified for all the comparison groups, involving 1609 patients. There were seven studies (with 443 patients) comparing terlipressin to placebo, five of which were considered to be high quality studies based on the Jadad scale. The meta‐analysis indicates that terlipressin was associated with a statistically significant reduction in all cause mortality compared to placebo (relative risk 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.49 to 0.88). Three studies (with 302 patients) were identified comparing terlipressin to somatostatin, two of which were high quality studies; only one high quality study (219 patients) comparing terlipressin to endoscopic treatment was identified. Within the limited power provided by these small numbers of patients, no statistically significant difference was demonstrated between terlipressin and either somatostatin or endoscopic treatment in any of the outcomes. For the remaining comparison groups (terlipressin versus balloon tamponade, terlipressin versus octreotide, and terlipressin versus vasopressin) only small, low quality studies were identified and no difference was demonstrated in any of the major outcomes. There was no significant difference between the terlipressin group and any of the comparison groups in the number of adverse events that caused death or withdrawal of medication.

Authors' conclusions

On the basis of a 34% relative risk reduction in mortality, terlipressin should be considered to be effective in the treatment of acute variceal hemorrhage. Further, since no other vasoactive agent has been shown to reduce mortality in single studies or meta‐analyses, terlipressin might be the vasoactive agent of choice in acute variceal bleeding.

Plain language summary

Terlipressin is a safe and effective treatment for bleeding from oesophageal varices which is a life threatening complication of cirrhosis of the liver

Esophageal varices are abnormal dilatations of veins in the lower part of the swallowing tube (oesophagus) that may develop in patients with chronic liver damage (cirrhosis). Bleeding from these varices is a life threatening complication with mortality between 20 and 50 per cent. Bleeding from varices may be treated with medications and/or with an endoscope which is a flexible tube with a camera at the end which allows direct visualization and treatment of bleeding varices. The reviewers evaluated the safety and effectiveness of a drug called terlipressin: they reported that terlipressin appears to be as safe as other treatments and that terlipressin may reduce the mortality from variceal bleeding as compared to placebo. The reviewers did not have sufficient data to decide whether terlipressin was better or worse than other available treatments such as other drugs (somatostatin, octreotide) or endoscopic treatment.

Background

Acute oesophageal variceal bleeding constitutes a serious medical emergency and is associated with a 20 to 50 per cent in‐hospital mortality. The treatments for oesophageal variceal bleeding include 'vasoactive' medications (somatostatin, octreotide, vasopressin, and terlipressin), endoscopic treatments (sclerotherapy or ligation), balloon tamponade, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stenting (TIPS), and surgery. Of all these potential treatments, only the vasoactive medications can be initiated early by non‐specialized personnel. Their putative action is to reduce portal blood flow and/or intrahepatic resistance and hence reduce portal pressure. There is considerable controversy regarding their efficacy and wide variation in their use. Terlipressin (triglycyl lysine vasopressin, also known as glypressin) is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin and it is the only agent that has been reported to reduce mortality in the setting of acute variceal bleeding (Freeman 1989; Levacher 1995; Söderlund 1990; Walker 1986). It has a completely different bioavailability profile from vasopressin enabling it to be given as intermittent intravenous injections usually every four or six hours instead of by continuous intravenous infusion. It is believed to have an intrinsic vasoconstrictor effect of its own in addition to being slowly cleaved in vivo to vasopressin (Burroughs 1998). It is not thought to have an effect on plasminogen activator (as does vasopressin), which is clearly undesirable in the setting of acute variceal haemorrhage, and in clinical trials it has a much lower incidence of severe adverse reactions.

Objectives

The objective of the review is to evaluate the efficacy of terlipressin in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding as compared to: a. Placebo. b. Balloon tamponade. c. Endoscopic treatment (ligation or sclerotherapy). d. The other vasoactive drugs (somatostatin, octreotide, or vasopressin).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Language was not restricted to English and attempts were made to identify published as well as unpublished data. Abstracts as well as fully published articles were included. The quality of each study was assessed using the Jadad scale (Jadad 1994) in order to enable a sensitivity analysis in the event of significant heterogeneity between studies.

Types of participants

Patients with suspected or documented bleeding from oesophageal varices. Patients had documented cirrhosis (any cause, any Child's class) and presented with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Types of interventions

Terlipressin, any dose, route or duration compared to a) placebo, b) balloon tamponade, c) endoscopic treatment, d) octreotide, e) somatostatin, or f) vasopressin.

Types of outcome measures

1. Mortality (which is the primary outcome). 2. Number failing initial haemostasis. 3. Number with rebleeding. 4. Number requiring additional procedures (balloon tamponade, endoscopic treatment, TIPS and surgery) for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding. 5. Number of blood transfusions. 6. Length of hospitalisation. 7. Quality of life assessment. 8. Adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

All the major medical electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, Current Contents, Biosis) were searched using search strategies developed in collaboration with the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group and shown below. There was no language limitation and the following techniques were employed in an attempt to minimize publication bias: a) The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register both include controlled trials published in abstract. The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group maintains its own database which is developed in part by hand‐searching 24 of the most prominent gastroenterology and hepatology journals as well as the abstracts of the world's major gastroenterology and hepatology associations published in these journals. b) The bibliography of all the identified controlled trials and review articles was scanned. c) Many of the authors of the identified trials as well as other experts and the manufacturers of terlipressin were asked if they were aware of any additional published or unpublished studies.

The following MEDLINE search strategy was used: (exp "esophageal and gastric varices"/ or "?esophageal varices".mp. or "varice$".mp. or exp Gastrointestinal hemorrhage/) AND (exp vasopressin/ or "vasopressin$".mp. or "terlipressin$".mp. or "glypressin$".mp. or exp lypressin/ or "terlypressin$".mp. or exp somatostatin/ or "somatostatin$".mp. or exp octreotide/ or "octreotide$".mp. or "sandostatin$".mp.) AND (clinical‐trial.pt. or controlled‐clinical‐trial.pt. or randomized‐controlled‐trial.pt. or meta‐analysis.pt. or random$.ti,ad,sh. or ((doubl$ or singl$)and blind$).ti,ab,sh. or exp Clinical trials/ or crossover.ti,ab,sh.)

Time period of MEDLINE search: 1966 ‐ December Week 4 1999. Date of original MEDLINE search: 15/11/1999. Total number of articles retrieved by this search: 216. Date of last MEDLINE search: 30/10/2002.

The following EMBASE search strategy was used: (VARICE! OR HEMORRHAGE OR HAEMORRHAGE OR BLEED) AND (PLACEBO! OR CLINICAL‐TRIAL OR CONTROLLED‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL OR RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL OR RANDOMISED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL OR META‐ANALYSIS OR RANDOM! OR META‐ANAL! OR METAANALY! OR ((DOUBL! OR SINGL!)AND BLIND!) OR CROSSOVER OR EVIDENCE‐BASED‐MEDICINE) AND (TERLIPRESSIN OR TERLYPRESSIN OR VASOPRESSIN! OR GLYPRESSIN OR LYPRESSIN OR TRIGLYCYL‐LYSINE‐VASOPRESSIN OR SOMATOSTATIN! OR SANDOSTATIN! OR OCTREOTIDE!)

Time period of EMBASE search: no time limit. Date of last search: 14/11/1999. Number of articles retrieved by this search: 253.

The following search strategy was used for The Cochrane Library: (VARICE* OR ESOPHAGEAL‐AND‐GASTRIC‐VARICES*:ME OR (?ESOPHAGEAL AND VARICES) OR (GASTRIC AND VARICES) AND (VASOPRESSIN OR VASOPRESSINS*:ME OR TERLIPRESSIN* OR TERLYPRESSIN OR GLYPRESSIN OR LYPRESSIN OR LYPRESSIN*:ME OR SOMATOSTATIN OR SOMATOSTATIN*:ME OR OCTREOTIDE OR OCTREOTIDE*:ME OR SANDOSTATIN

Time period of Cochrane search: no time limit Date of original search: 14/11/99 (searching Issue 4 of the 1999 database) Number of articles retrieved from this search: 187. Date of most recent search: 30/10/2002 (searching Issue 3 of the 2002 database)

The following search strategy was used for The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register: vasopressin* or lypressin or terlipressin or glypressin or somatostatin or octreotide

Time period for search of the database of the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group: no time limit. Date of original search: 14/11/99 (this database is updated weekly) Number of articles retrieved from this search: 255. Date of most recent search: 30/10/2002

Data collection and analysis

Study selection, quality assessment, and data collection The studies identified by the search strategies were entered in a database, and the trials, which fulfilled the criteria of the review mentioned above, were selected. For each study we described important components of methodological quality including concealment of allocation, generation of a randomisation sequence, double‐blinding, and description of losses to follow‐up. Furthermore, the Jadad scale was employed in order to allow us to investigate whether our results were primarily driven by low quality (and potentially high bias) studies. The Jadad scale (Jadad 1994) was chosen a priori both because it had been validated to be able to separate studies into 'high quality score' (low bias) studies and 'low quality score' (high bias) studies and also because studies dealing with digestive diseases were included in the validation (Jadad 1996; Moher 1998). It consists of the following questions: 1) Was the study described as randomised (this includes the use of words such as randomly, random and randomisation)? One point. 2) Is the method of randomisation appropriate? One point is added if the method to generate the sequence of randomisation is described and it is appropriate (e.g., table of random numbers, computer generated). One point is deducted if the method to generate the sequence of randomisation is described and it is inappropriate (e.g., date of birth). Zero points if the method of randomisation is not described. 3) Was the study described as double blind? One point. 4) Is the method used appropriate? One point is added if the method of masking is described and it is appropriate (e.g., identical placebo). One point is deducted if the method of masking is described and it is inappropriate(e.g., comparison of tablet versus injection with no double dummy). Zero points if the method of masking is not described. 5) Is there a description of withdrawals and drop‐outs? One point is given if the numbers and reasons for withdrawal in each group are stated. If there are no withdrawals, the report must say so. If there is no statement on withdrawals, this item is given no points.

The scale awards a maximum of five points and in this report a study that scored three to five points was termed 'high quality', whereas a study that scored zero to two points was termed 'low quality', as in Moher 1998. In practice, since only randomised studies were included, all included studies scored one or more points.

The quality criteria of the Jadad scale and the outcome measures mentioned above were extracted independently by two reviewers, one of whom was blinded with respect to the authors and the journal of publication. Disagreement was resolved by arbitration between the two reviewers and the content expert. A copy of the data extraction form was sent to the corresponding author of each study, who was asked to correct erroneous data abstraction and provide missing information. We asked authors of abstracts to provide full information about methods and updated results.

Description of outcome measures The following outcomes were abstracted from the articles: 1) Mortality. Only all cause mortality was evaluated, in accordance with the Baveno consensus report in which any death up to 42 days after a variceal bleed was assumed to be caused by the bleed regardless of the mode of death. If a study reported mortality at different time intervals, the outcome for the longest time interval was used for this analysis, up to 42 days. If mortality up to a certain number of days was not reported, then the mortality at discharge from the hospital was used for the analysis.

2) Number failing initial haemostasis. Failure of haemostasis was defined in most studies as evidence of continued bleeding such as melena, hematemesis and bloody nasogastric aspirate or unstable haemodynamic parameters and haemoglobin levels or both. However, there was considerable variation in the time at which this outcome was assessed ranging from eight hours (Levacher 1995) to five days (Patch 1999). 3) Number with rebleeding. In most studies the evidence for rebleeding was the same as evidence for failure of haemostasis mentioned above. The rebleeding rate at the longest reported time interval was used for this analysis, up to 42 days. If rebleeding rates up to a certain number of days were not reported, then the rebleeding rate at discharge was used.

4) Number of procedures (balloon tamponade, sclerotherapy, surgery, or TIPS) required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding; this outcome was included as a measure of the degree and severity of uncontrolled bleeding/rebleeding. Therefore, procedures that were done routinely as part of the protocol of a study were not included in the analysis. For instance, in Walker 1986 all patients were offered balloon tamponade on admission, and in Patch 1999 and Levacher 1995 all patients with confirmed varices underwent sclerotherapy at initial endoscopy. These procedures were not included in this analysis.

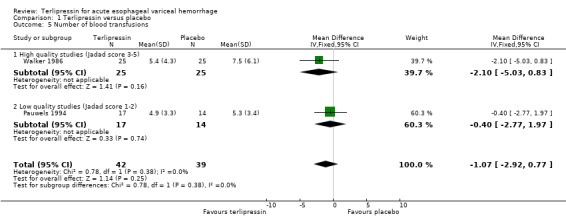

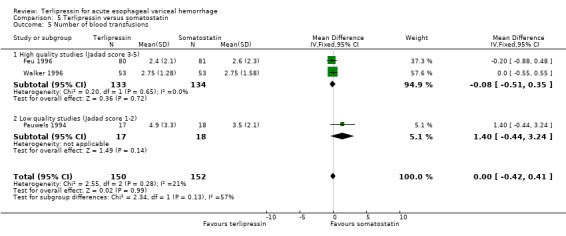

5) Number of blood transfusions. Unfortunately, because of the skewed distribution of blood transfusions a number of studies chose to report medians and ranges instead of means and standard deviations. There is no universally accepted, robust way of using medians and ranges in meta‐analysis. Therefore, only the results of the studies that report means and standard deviations are combined in the meta‐analysis; the results of all the studies are presented in separate tables (Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13). The number of blood transfusions at the longest reported time interval was used for this analysis. Most studies did not report precise criteria for transfusing blood.

1. Terlipressin versus placebo: Blood transfusion requirements.

| Study ID | Terlipressin‐TPN (n) | TPN Median/Mean | TPN Range/SD | Placebo (n) | Placebo Median/Mean | Placebo Range/SD |

| Brunati 1996 | 28 | Median = 2 | Range = 1‐5 | 27 | Median = 4 | Range = 2‐12 |

| Freeman 1989 | 15 | Median = 3 | Range = 1‐8 | 16 | Median = 4 | Range = 1‐8 |

| Levacher 1995 | 41 | Mean/day = 0.79 | SD = 0.6 | 43 | Mean/day = 1.94 | SD = 1.7 |

| Patch 1999 | ?62 | Median = 2.5 | Range = ND | ?61 | Median = 3 | Range = ND |

| Pauwels 1994 | 17 | Mean = 4.9 | SD = 3.3 | 14 | Mean = 5.3 | SD = 3.4 |

| Söderlund 1990 | 31 | Median = 2 | Range = 0‐6 | 29 | Median = 3 | Range = 0‐15 |

| Walker 1986 | 25 | Mean = 5.4 | SD = 4.3 | 25 | Mean = 7.5 | SD = 6.1 |

2. Terlipressin versus balloon tamponade: Blood transfusion requirements.

| Study ID | Terlipressin‐TPN (n) | TPN Median/Mean | TPN Range/SD | Tamponade (n) | Tamponade median/Mea | Tamponade Range/SD |

| Fort 1989 | 23 | Mean = 3.5 | Range = 0‐10 | 24 | Mean = 3.1 | Range = 0‐9 |

| Garcia ‐ Compean 1997 | 20 | Mean = 3 | SD = 3.2 | 20 | Mean = 5.7 | SD = 4.1 |

| Colin 1987 | 27 | Not recorded | Not recorded | 27 | Not recorded | Not recorded |

3. Terlipressin versus octreotide: Blood transfusion requirements.

| Study ID | Terlipressin TPN (n) | TPN Median/Mean | TPN Range/SD | Octreotide OCT (n) | OCT Median/Mean | OCT Range/SD |

| Brunati 1996 | 28 | Median=2 | Range=1‐5 | 28 | Median=3 | Range=1‐8 |

| Pedretti 1994 | 30 | Mean=1.8 | SD=1.50 | 30 | Mean=1.70 | SD=1.40 |

| Silvain 1993 | 41 | Mean=3.4 | SD=2.9 | 46 | Mean=1.60 | SD=1.70 |

4. Terlipressin versus vasopressin: Blood transfusion requirements.

| Study ID | Terlipressin TPN (n) | TPN Median/Mean | TPN Range/SD | Vasopressin VPN (n) | VPN Median/Mean | VPN Range/SD |

| D'Amico 1994 | 84 | Mean=1.7 | 1.6 | 81 | Mean=1.8 | SD=1.8 |

| Lee 1988 | 21 | Mean=2.7 | SD=2.3 | 24 | Mean=2.3 | SD=2.2 |

| Freeman 1982 | 10 | Median=3 | Range=3‐7 | 11 | Median=6 | Range=4‐12 |

6) Length of hospitalisation. The mean and standard deviation of the length of hospitalisation for the acute bleeding episode was abstracted.

7) Quality of life assessment. None of the studies identified so far reported any assessment of quality of life.

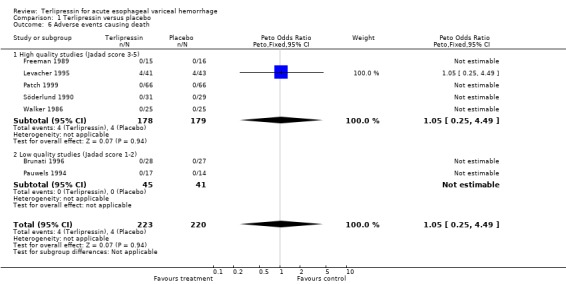

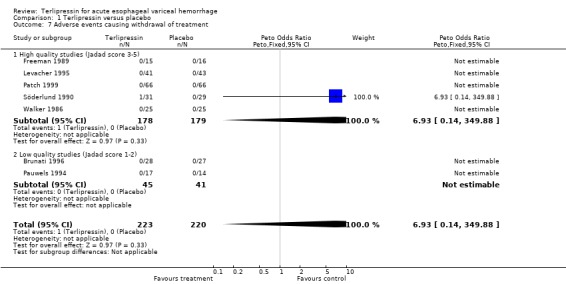

8) Adverse events. In critically sick patients, such as patients with acute variceal bleeding, when an unexpected complication occurs, it is difficult to know if this is due to the treatment or the disease itself. In order to balance out any potential reporting bias in adverse events we therefore decided to take advantage of the randomised design of the studies and directly compare the adverse events that were thought to occur in the terlipressin group to the adverse events that were thought to occur in each of the control groups. For this analysis we only used the adverse events that were reported to either cause of death or discontinuation of treatment. We reasoned that mild side‐effects such as facial pallor or headache, which do occur frequently with terlipressin, were clinically less important in the face of a life‐threatening problem.

Data analyses The relative risk was the measure of association for dichotomous variables and the weighted mean difference for continuous variables. All the results are presented such that a relative risk less than one and a weighted mean difference less than zero favour terlipressin. The Breslow‐Day test was used to test for homogeneity under the null hypothesis that the RRs were consistent across studies and homogeneity was rejected for P values < 0.10. The Mantel‐Haenszel method was used to calculate a combined relative risk for the dichotomous variables while the inverse variance method was used to calculate the weighted mean difference for continuous variables. For dichotomous variables, a modification of the Mantel‐Haenszel method was used (adding 0.5 to each cell) when any cell contained zero.

A priori, the following hypotheses were developed in order to try and identify differences in treatment and to explain potential statistical heterogeneity between studies: 1) Study results may be related to study quality. Quality was assessed by the Jadad scale and in order to determine if the results were related to study quality, the results were presented separately for the high quality and low quality studies for each outcome. 2) Study results may be related to the dose, duration or formulation of the intervention. 3) Study results may be related to the percentage of patients in each Child's class. 4) Study results may be related to whether patients with documented variceal bleeding were included as opposed to patients suspected of having variceal bleeding. 5) The results presented in fully published manuscripts may differ systematically from results published only in abstract form. 6) The results of studies in which all patients underwent endoscopic treatment may differ systematically from the results of studies in which endoscopic treatment was not available or studies in which endoscopic treatment was offered only for uncontrolled bleeding.

Results

Description of studies

The articles identified by all the computerized bibliographic searches were entered into one combined database with 346 articles. Of these, 162 articles were excluded after reading their computerized abstract because their content was obviously not relevant to terlipressin (described other treatments or made no reference to treatment). The remaining 184 articles were retrieved and their bibliography was scanned which identified another 32 potentially relevant articles that were retrieved. Of these 216 articles, 185 were excluded for the following reasons: 96 were background/review articles, 57 were studies of treatments other that terlipressin, 23 were studies of the haemodynamic effects of terlipressin on portal and variceal pressure and 9 were meta‐analyses. From the remaining 31 studies, detailed information was abstracted on a data abstraction sheet regarding the eligibility of the study, its methodological quality, and its results. Another 11 studies were excluded for the following reasons: no control group ( Arcidiacono 1992; Fiaccadori 1993; Chang 1991; De Franchis 1993), non‐randomised (Chen 1990; Heygere 1986; Olivero 1986; Vosmik 1977), not acute variceal bleeding (Palazzi 1989; Campisi 1993), inadequate data (Silk 1979). The remaining 20 studies with a total of 1609 patients were included in the systematic review and meta‐analysis. Of these 20 studies, The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register identified 16 (80%), The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register 15 studies (75%), MEDLINE 14 (70%), and EMBASE 14 (70%). Searching Biosis and Current Contents resulted in a much smaller number of articles all of which were included in each of the four main databases mentioned above. The remaining three studies were identified by searching the bibliography, whereas contacting experts and the drug manufacturers did not identify any additional studies. Two of the studies have so far been published only as abstracts (Brunati 1996; Patch 1999) and the remaining 18 were published as full reports. The analytical results of the search strategy are shown in Table 14.

5. Analytical results of search strategy.

| Study ID | Type of Publication | MEDLINE | EMBASE | CCTR | CHBG | Bibliography | Experts |

| Chiu 1990 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| D'Amico 1994 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Feu 1986 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Fort 1990 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Freeman 1982 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Freeman 1989 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Garcia‐Compean 1997 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Lee 1988 | Journal | No | No | No | No | Yes | Not applicable |

| Levacher 1995 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Pauwels 1994 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Pedretti 1994 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Silvain 1993 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Söderlund 1990 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Walker 1986 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Walker 1996 | Journal | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Brunati 1996 | Abstract | No | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Cooperative 1997 | Abstract | No | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Patch 1999 | Abstract | No | No | No | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Colin 1987 | Book | No | No | No | No | Yes | Not applicable |

| Desaint 1987 | Book | No | No | No | No | Yes | Not applicable |

| Yield or sensitivity | 14/20=70% | 14/20=70% | 16/20=80% | 15/20=75% | |||

Not all studies reported data on all the outcomes mentioned above. In addition, there were differences in the time after admission at which they reported each of the outcomes. The outcomes, reported by each study and the times at which they are reported, are documented in the table titled 'Characteristics of included studies'. Corroborative, corrective, and missing data were kindly provided by the authors of 12 studies (Brunati 1996; Escorsell 2000; D'Amico 1994; Feu 1996; Fort 1990; Garcia‐Compean 1997; Lee 1988; Levacher 1995; Silvain 1993; Söderlund 1990; Walker 1986; Walker 1996). This included very extensive data on methodology and outcomes from the authors of one of the two abstracts included in this review (Brunati 1996) and we have been in touch with the authors of the second abstract, Patch 1999, for additional information.

a) Terlipressin versus placebo Seven randomised placebo‐controlled trials were identified of which five are published in full (Freeman 1989; Levacher 1995; Pauwels 1994; Söderlund 1990; Walker 1986) and two are published as abstracts only (Brunati 1996; Patch 1999): see Table: 'Characteristics of included studies' for details. Four of these studies included only patients who had documented variceal bleeding by endoscopy (Brunati 1996; Freeman 1989; Söderlund 1990; Walker 1986). In two studies (Levacher 1995; Pauwels 1994) the patients, who had cirrhosis and presented with massive upper gastro‐intestinal bleeding, were randomised before endoscopy and therefore invariably a small proportion of these episodes were caused by sources other than varices. In three studies (Brunati 1996; Levacher 1995; Patch 1999) all patients with confirmed varices underwent sclerotherapy at the initial endoscopy as part of the trial protocol; in one study (Walker 1986) all patients were offered balloon tamponade on admission; and in the remaining three studies no procedures were routinely done in the first 24 hours after admission except in the event of uncontrolled bleeding. The dose of terlipressin varied from 1‐2 mg intravenously, the frequency from every four to every six hours and the duration from eight hours (Levacher 1995) to five days (Patch 1999). The time of initiation of treatment varied from starting treatment by the Emergency Services at the patient's home (Levacher 1995) to starting treatment within four hours of admission (Freeman 1989).

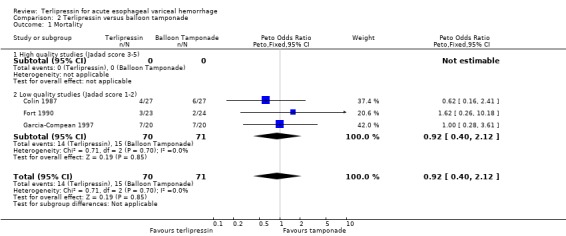

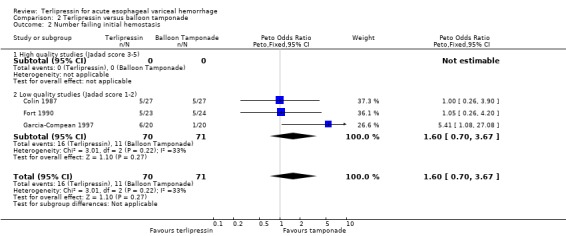

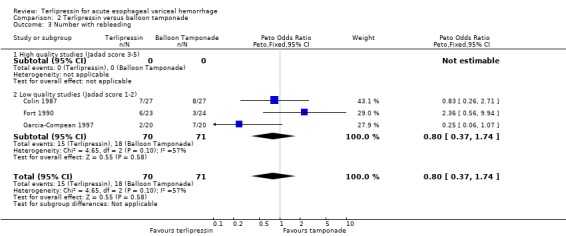

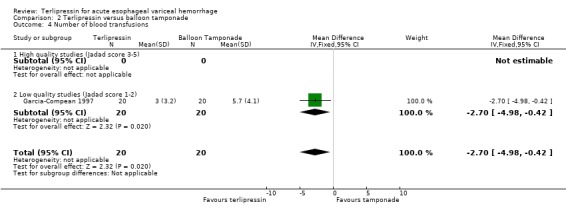

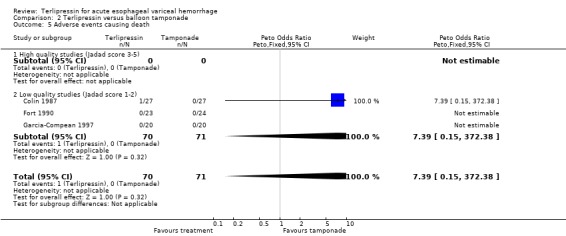

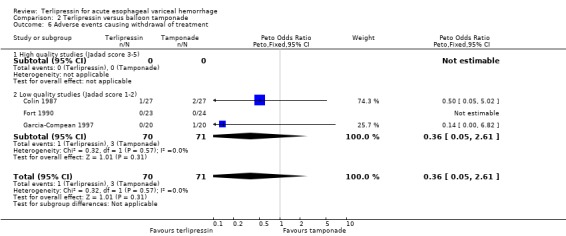

b) Terlipressin versus balloon tamponade Three randomised clinical trials were identified all published in full (Colin 1987; Fort 1990; Garcia‐Compean 1997): see Table "Characteristics of included studies" for details. In all three studies the patients were randomised after endoscopy and all had documented variceal bleeding. Sclerotherapy was not performed routinely in any of these studies. In Fort 1990, the patients who did not have control of bleeding at 12 hours received the alternative treatment, that is patients in the balloon tamponade group received terlipressin and vice versa. There was no cross over in the other two studies. The dose of terlipressin varied from 1‐2 mg intravenously, the frequency from every four to every six hours and the duration from 24‐48 hours.

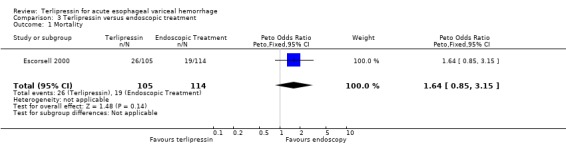

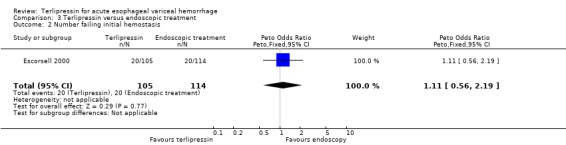

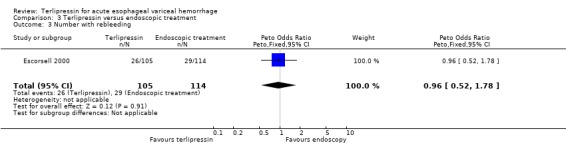

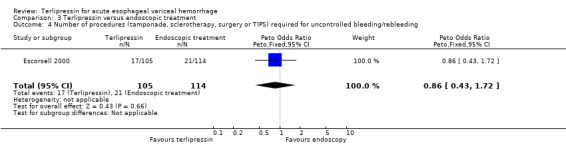

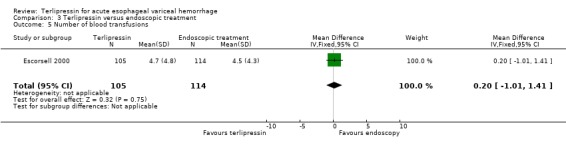

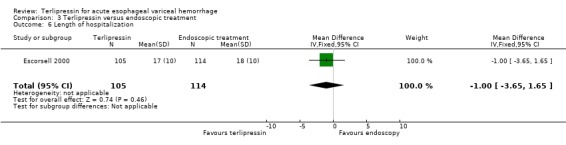

c) Terlipressin versus endoscopic treatment Only one study was identified (Escorsell 2000) which compared terlipressin to sclerotherapy and this was large, multicenter, randomised controlled trial. Patients were randomised after diagnostic endoscopy and all had endoscopically documented acute variceal bleeding. The dose of terlipressin used was 2 mg intravenous injection every four hours until bleeding was controlled and then 1 mg every four hours for five days. When the initial treatment failed to control bleeding, the patients received alternative therapy using either pharmacological therapy (except terlipressin), emergency sclerotherapy, balloon tamponade, TIPS, surgery , or combination thereof. Therefore, in the study, eight patients randomised to terlipressin received sclerotherapy because of failure to control bleeding and 18 patients randomised to sclerotherapy received vasoactive drugs.

d) Terlipressin versus octreotide Three randomised controlled trials were identified, of which two were published in full (Pedretti 1994; Silvain 1993) and one was published as an abstract only (Brunati 1996). In all three studies, the patients were randomised after endoscopy and all had documented variceal bleeding. In one study (Brunati 1996), all patients underwent sclerotherapy at the initial endoscopy whereas in the other two studies (Pedretti 1994; Silvain 1993) only patients with uncontrolled bleeding underwent emergency sclerotherapy. The dose of terlipressin varied from 1‐2 mg intravenously, the frequency from every four to every six hours and the duration from 24 hours to seven days. Octreotide was given either subcutaneously (100 mcg every eight to 12 hours) or intravenously (25 mcg/hour) for 24 hours to seven days.

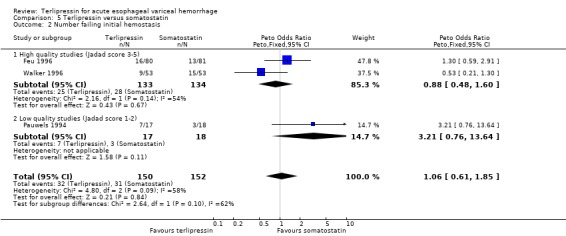

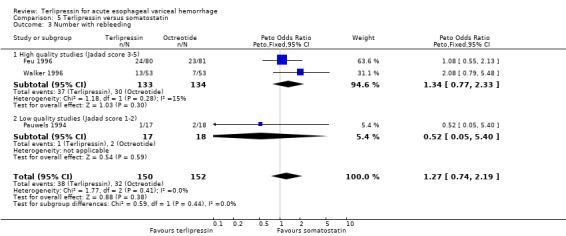

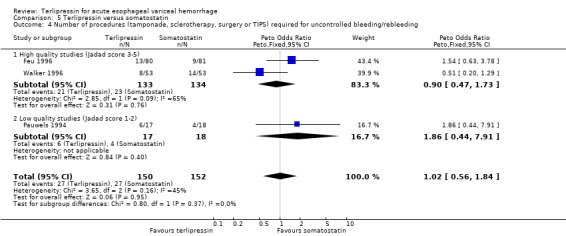

e) Terlipressin versus somatostatin Three randomised clinical trials were identified all of which were published in full (Feu 1996; Walker 1996; Pauwels 1994). In Feu 1996 and Walker 1996, patients were randomised after endoscopy and included only patients with variceal bleeding. In Pauwels 1994 patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension who presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding were randomised prior to endoscopy. However, the authors excluded from the analysis the patients whose bleeding was not felt to be variceal in origin after diagnostic endoscopy was performed. None of the studies performed sclerotherapy at the initial endoscopy. The dose of terlipressin varied from 1‐2 mg intravenously, the frequency from every four to every six hours and the duration from 24‐48 hours. The dose of somatostatin was 250 mcg/hour intravenous infusion for 24‐48 hours with or without boluses for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding.

f) Terlipressin versus vasopressin Five randomised clinical trials were identified, all of which were published in full (Freeman 1982; Desaint 1987; Lee 1988; Chiu 1990; D'Amico 1994). In D'Amico 1994, all patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension who presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding were randomised prior to endoscopy and therefore a small number of them actually had sources of bleeding other than varices. The other four studies only included patients with endoscopically documented acute variceal bleeding. In D'Amico 1994 all the patients with bleeding varices at initial endoscopy underwent sclerotherapy and, if that failed to control bleeding, balloon tamponade. None of the other four studies performed sclerotherapy or balloon tamponade routinely at presentation. The dose of terlipressin varied from 1‐2 mg intravenously, the frequency from every four to every six hours and the duration from 24 to 48 hours. The dose of vasopressin varied from 0.4 to 0.66 units/min intravenous infusion for 24 to 48 hours with (D'Amico 1994; Lee 1988) or without (Freeman 1982; Desaint 1987; Chiu 1990) nitroglycerine.

Risk of bias in included studies

a) Terlipressin versus placebo Five of the included studies achieved a 'high quality' score according to the Jadad scale which was a priori chosen to grade the quality of the studies (see 'Criteria for selecting studies for this review' for a description of the Jadad scale, and the Table 'Characteristics of included studies' for a description of each study's quality assessment). Two studies were graded 'low quality' (Pauwels 1994; Brunati 1996). Two studies described adequate concealment of the treatment allocation (Levacher 1995; Walker 1986); the others do not provide enough information to enable a decision on the adequacy of concealment.

b) Terlipressin versus balloon tamponade All three studies were graded low quality by the Jadad scale. This was partly due to the fact that none of these studies was double‐blinded which is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve in studies where the one arm of the trial involves balloon tamponade. None of the studies describes whether they attempted to conceal treatment allocation.

c) Terlipressin versus endoscopic treatment The one study identified in this category (Escorsell 2000) was graded high quality: the randomisation sequence was generated by computer separately for each participating centre and there was an adequate description of drop‐outs. The physicians and patients were not blinded, which, as for the balloon tamponade comparison, would have been extremely hard to accomplish. Personal communication with the authors confirmed that the outcome assessor was also not blinded. Concealment of treatment allocation was achieved through sealed, opaque, consecutively numbered envelopes. d) Terlipressin versus octreotide All three included studies (Pedretti 1994; Brunati 1996; Silvain 1993) were graded 'low quality' by the Jadad scale. None of these studies was double blind. Pedretti 1994 describes adequate concealment of treatment allocation whereas there is no description of concealment in Silvain 1993 or Brunati 1996 (personal communication).

e) Terlipressin versus somatostatin Two of the included studies (Feu 1996; Walker 1996) were graded "high quality" by the Jadad scale, and Pauwels 1994 was graded low quality. Feu 1996 and Walker 1996 described adequate concealment with the indistinguishable drugs pre‐packed in numbered boxes whereas there was no description of a method of concealment of treatment allocation in Pauwels 1994.

f) Terlipressin versus vasopressin All five studies were graded 'low quality' by the Jadad scale and only one study (D'Amico 1994) described an adequate method of concealment of treatment allocation.

Effects of interventions

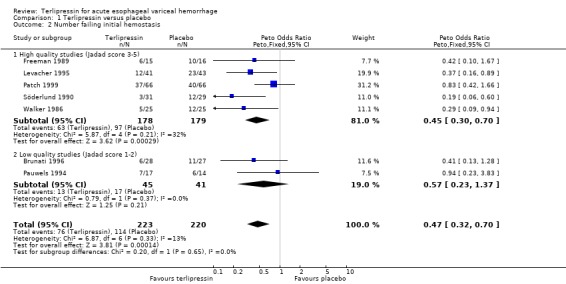

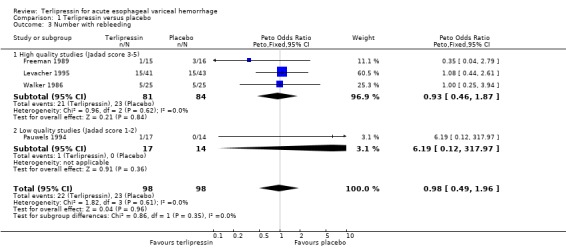

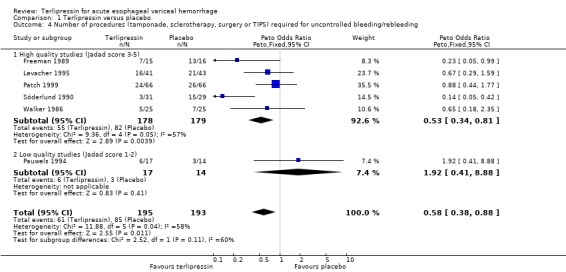

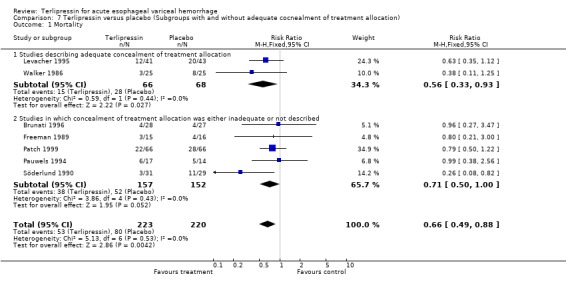

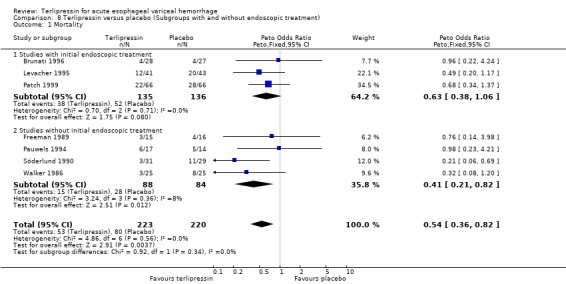

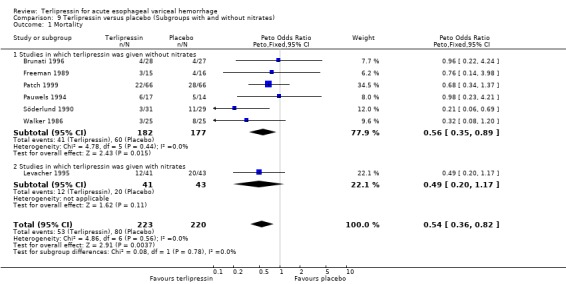

a) Terlipressin versus placebo A total of 443 patients from seven trials were included in the meta‐analysis. All seven trials reported data on mortality which is the primary outcome of this systematic review and there was no statistical heterogeneity between them (p = 0.56). There was a statistically significant mortality benefit in flavour of terlipressin with a relative risk of 0.66 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 0.88). Six of the seven trials reported the procedures that were performed in order to stop uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding: there was no statistical heterogeneity among the high quality studies and pooling the results showed a statistically significant benefit in favour of terlipressin with a relative risk of 0.72 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.93). All seven trials reported data on failure of initial haemostasias with a combined relative risk of 0.66 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.82). However, there is statistically significant heterogeneity between the trials, which persists even among the high‐quality trials. An analysis by the random effects model yielded a combined relative risk of 0.63 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.89) for all the trials and a combined relative risk of 0.57 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.90) for the high quality trials alone. In all seven trials of terlipressin versus placebo the blood transfusion requirements were less in the terlipressin group than in the placebo group (see Table 10). Unfortunately, four of these trials (Brunati 1996; Freeman 1989; Söderlund 1990; Patch 1999) used a median and a range to summarize their results and one study (Levacher 1995) reported the mean units per patient per day. Therefore, only the results of the remaining two trials were combined in meta‐analysis and there was no statistically significant difference with a weighted mean difference of ‐1.075 blood transfusions (95% CI ‐2.918 to 0.768). Only four trials reported rebleeding rates, and there was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and placebo. None of the trials reported data on length of hospitalisation.

In response to comments (Gøtzsche 2001, see comments), an additional post‐hoc analysis was performed in which the seven trials were sub‐divided based on whether they described adequate concealment of treatment allocation or not. Among the two trials that described adequate concealment (Levacher 1995; Walker 1986), terlipressin was associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality compared to placebo (relative risk 0.56, 95% CI 0.33‐0.93). There was no statistical heterogeneity between these two studies.

b) Terlipressin versus balloon tamponade A total of 141 patients from three trials were included in the meta‐analysis. There was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and balloon tamponade in mortality (relative risk 0.94, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.77), failure of initial haemostasis (relative risk 1.48, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.98) and rebleeding (relative risk 0.84, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.55). None of the trials reported the procedures, if any, that were required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding. Personal communication with the authors of Fort 1990 confirmed that sclerotherapy and TIPS were not available at the time of the study and that no patient underwent emergency surgery. Blood transfusions were not recorded in Colin 1987 and Fort 1990 reported the mean and range (without a standard deviation) which were approximately equal in the terlipressin and tamponade groups (see Table 11). Only in Garcia‐Compean 1997 are blood transfusions reported as means and standard deviations and there was no statistically significant difference between the terlipressin and balloon tamponade groups.

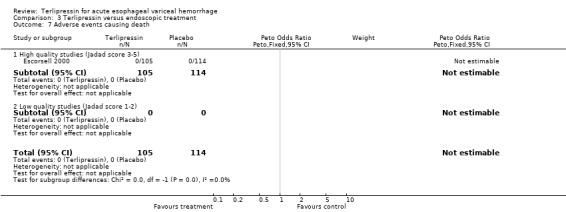

c) Terlipressin versus endoscopic treatment Only one trial was identified with 219 patients. There were no statistically significant differences between the terlipressin and endoscopic treatment groups in mortality (relative risk 1.49, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.52), failure of initial haemostasis (relative risk 1.09, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.90), rebleeding (relative risk 0.97, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.54), number of procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding (relative risk 0.88, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.57), number of blood transfusions (weighted mean difference = 0.20, 95% CI ‐1.01 to 1.41) and length of hospitalisation (weighted mean difference = ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐3.561 to 1.651).

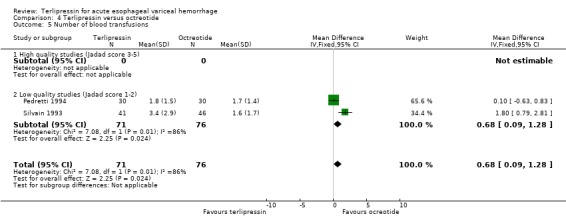

d) Terlipressin versus octreotide Meta‐analysis of all three identified trials with a total of 203 patients showed no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and octreotide in mortality (relative risk 1.20, 95% CI 0.66 to 2.15). There was a statistically significant difference in failure of initial haemostasis in favour of octreotide with a combined relative risk of 1.62 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.50) and no statistical heterogeneity. Rebleeding rates and procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding were only reported in two (Pedretti 1994; Silvain 1993) of the three trials and showed no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and octreotide. Brunati 1996 reported blood transfusions only as median and range: two units in the terlipressin group (range 1 to 5) and three units in the octreotide group (range 1to 8); see Table 12. The weighted mean difference for the other two studies was in favour of octreotide (0.684 units, 95% CI 0.090 to 1.279), however, there was significant statistical heterogeneity (Chi square = 7.08, df = 1). No study provided data on length of hospital stay.

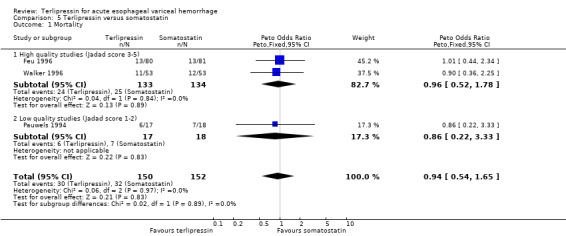

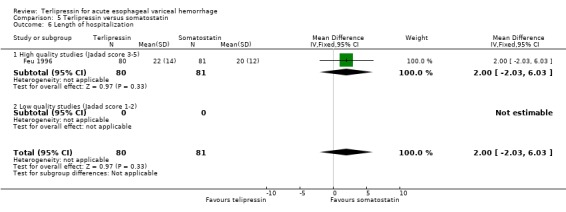

e) Terlipressin versus somatostatin A total of 302 patients from three trials were included in the meta‐analysis, which showed no difference between terlipressin and somatostatin in mortality (relative risk 0.95, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.48), failure of initial haemostasis (relative risk 1.05, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.63), rebleeding rates (relative risk 1.20, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.81) and procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding (relative risk 1.02, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.64). Blood and plasma transfusions together were reported in Walker 1996 and it was established through personal communication with the authors that they were given in approximately equal amounts. The reported mean was therefore divided by two and the reported standard deviation by four before combining the results with the other two studies. There was no difference in the weighted mean difference of the blood transfusions between terlipressin and somatostatin (weighted mean difference = ‐0.004, 95% CI ‐0.419 to 0.412). Length of hospitalisation (days) was only available from Feu 1996 and there was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and somatostatin (weighted mean difference = 2.00, 95% CI ‐2.03 to 6.03).

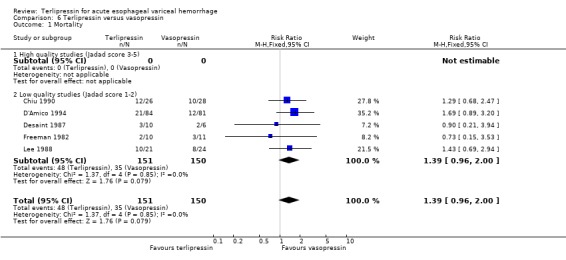

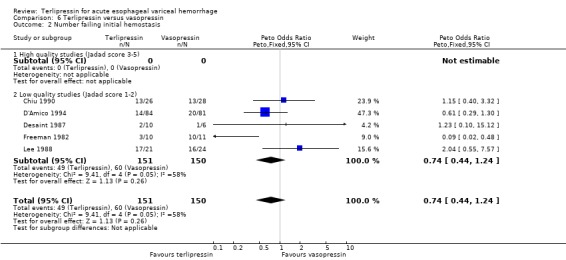

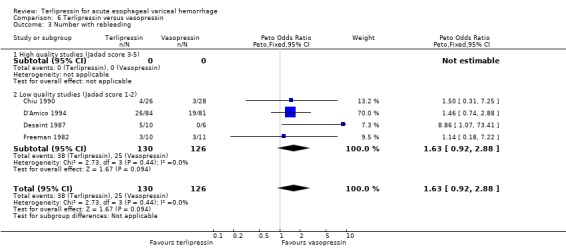

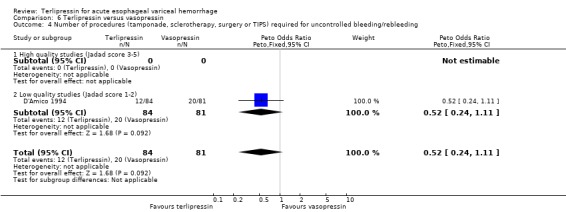

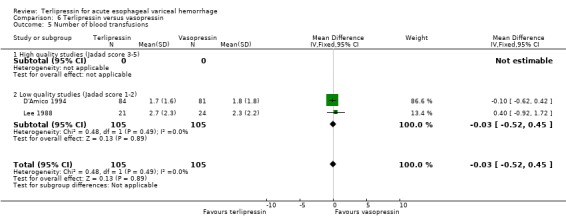

f) Terlipressin versus vasopressin A total of 301 patients from five studies were included in the meta‐analysis, which showed no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and vasopressin in mortality (relative risk 1.39, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.00), failure of initial haemostasis (relative risk 0.85, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.13) and rebleeding rate (data available from only four of the five studies giving a relative risk of 1.44 with a 95% CI 0.93 to 2.25). Only D'Amico 1994 reported the procedures that were performed for uncontrolled bleeding and there was no significant difference between the terlipressin and the vasopressin groups (relative risk 0.58, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.11). Desaint 1987 and Chiu 1990 did not report the blood transfusion requirements whereas Freeman 1982 reported only a median and a range with no mean or standard deviation (Table 13). In the remaining two studies (D'Amico 1994; Lee 1988) there was no statistically significant difference between the terlipressin and vasopressin groups (weighted mean difference = ‐0.033 blood transfusions, 95% CI ‐0.517 to 0.457).

g) Quality of life None of the included trials reported quality of life assessments.

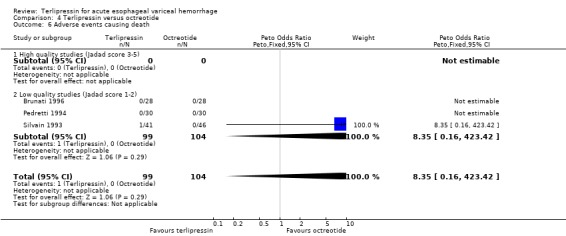

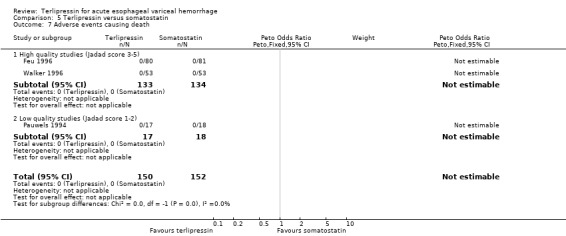

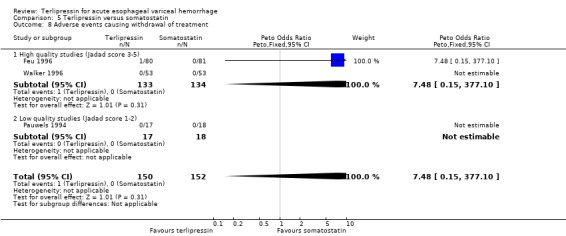

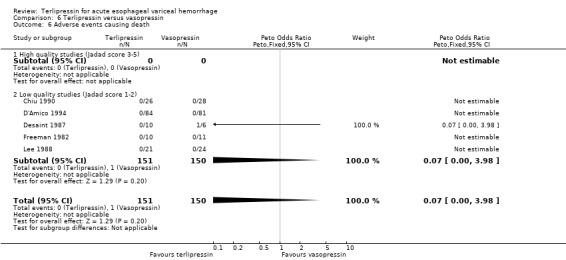

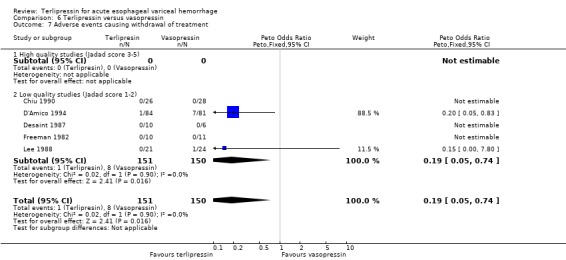

e) Adverse events There was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and any of the control groups (placebo, balloon tamponade, endoscopic treatment, or other vasoactive agent) in the number of deaths that were thought to be secondary to adverse events. There were six deaths out of 798 treated patients in the terlipressin group: four were attributed to fibrinolysis (Levacher 1995), one to left ventricular failure (Silvain 1993) and one was a 'sudden death' of unknown etiology (Colin 1987). There were five deaths out of 811 patients in the control groups: four were attributed to fibrinolysis and occurred in the placebo group of Levacher 1995 and one to arm necrosis which led to shock and death and occurred in the vasopressin group of Desaint 1987.

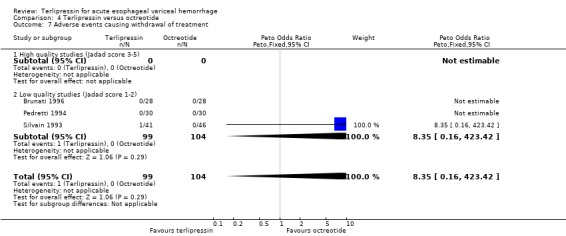

In the analysis of adverse events causing withdrawal of medication we excluded the one study which compared terlipressin to endoscopic treatment (Escorsell 2000) because in the endoscopic treatment group, where patients received sclerotherapy at the initial endoscopy, there could not be any 'withdrawal of treatment'. Among the remaining studies there was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and any of the control groups, except vasopressin. There were five withdrawals of treatment out of 693 patients in the terlipressin group: three were attributed to bradycardia (Söderlund 1990; Silvain 1993; D'Amico 1994), one to ventricular fibrillation (Feu 1996) and one to respiratory failure (Colin 1987). There were 11 withdrawals of treatment out of 697 patients in the control groups: two were attributed to stripping off tube and one to bleeding from compression ulcers in balloon tamponade groups (Colin 1987; Garcia‐Compean 1997); the other eight occurred in vasopressin groups and one was attributed to myocardial ischaemia (Lee 1988), one to severe headache (D'Amico 1994), three to abdominal pain (D'Amico 1994), one to bradycardia (D'Amico 1994) and two to hypertension (D'Amico 1994). The only sub‐group of studies with a statistically significant result was the terlipressin versus vasopressin subgroup with more withdrawals due to adverse events in the vasopressin group.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate whether terlipressin was better than placebo in acute variceal bleeding and whether it was better than the other commonly used treatments for this condition, namely endoscopic treatment, balloon tamponade, and the other vasoactive agents (vasopressin, somatostatin, and octreotide). Attempts were made to identify every published and unpublished study by searching The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Biosis, and Current Contents without any language restriction, by looking at the bibliography of all identified studies and review articles and by contacting experts in the field and the manufacturers of terlipressin. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using a well validated instrument, the Jadad scale. The searches, quality assessment and data abstraction were done independently by two investigators one of whom was blinded to the authors and periodical of publication of each study. For the majority of the studies we obtained additional data from the authors and asked them to verify our quality assessment and data abstraction.

All cause mortality was set a priori as the primary outcome measure of this systematic review, both because of the clinical importance of this outcome and also in the hope that there would be less heterogeneity between studies with regards to mortality than with regards to other outcomes such as rebleeding and control of bleeding which have been defined differently in different studies. In the terlipressin versus placebo category seven trials were identified five of which were graded high quality. With regards to mortality there was no statistical heterogeneity and there was a statistically significant reduction in mortality with terlipressin with a relative risk of 0.66 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.88). Assuming a mortality rate of 36% as was found in the control group in these seven trials (80 out of 220 patients died), one would need to treat 8.3 patients with terlipressin instead of placebo to prevent one death.

Most of the results for the secondary outcomes supported the beneficial role for terlipressin compared to placebo: there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding or rebleeding; there was a reduction in the number failing initial haemostasis, however, there was significant statistical heterogeneity in this outcome. This was not unexpected given the differences in the definition and the time of assessment of failure of initial haemostasis among different studies. We postulated that blood transfusion requirements would be a useful surrogate marker for the severity of bleeding and rebleeding and that we could avoid the problem of heterogeneity since there is no issue of different definitions and blood is usually readily available. Indeed, in each of the seven studies there were fewer blood transfusions in the terlipressin group than in the placebo group. However, we were not able to quantify this difference by meta‐analysis as the majority of the studies reported blood transfusion requirements as a median and range instead of a mean and standard deviation. There was no difference in rebleeding rates and none of the studies reported data on the length of hospitalisation.

Only two of the sub‐group analyses that we defined a priori could be performed due to the small number of identified studies. In the terlipressin versus placebo category there were five high quality and two low quality studies. There was a statistically significant mortality benefit in favour of terlipressin even among the high quality studies alone (relative risk 0.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.85). Usually, it is expected that the low‐quality studies tend to show a more exaggerated response to a treatment than the high quality studies, presumably due to the greater degree of bias in low quality studies Moher 1998. Surprisingly, in this systematic review, the relative risk for the high quality studies alone was lower than the relative risk for all the studies together. This finding is reassuring in that it excludes the possibility that the overall relative risk reduction was driven by low quality, high bias studies.

In the terlipressin versus placebo category there were three trials (Brunati 1996; Levacher 1995; Patch 1999) in which all patients were treated with endoscopic sclerotherapy at the initial diagnostic endoscopy. Therefore, these were trials where terlipressin plus sclerotherapy was compared to sclerotherapy alone. In this sub‐group there was a benefit for the terlipressin plus sclerotherapy group which approached statistical significance (relative risk 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.04). This suggests that even in centres that have the capability of 24‐hour, rapid, emergency endoscopic treatment for variceal bleeding, terlipressin might convey an additional mortality benefit.

In one of the studies that compared terlipressin to placebo (Levacher 1995), the patients in the terlipressin group also received a nitroglycerin patch whereas the patients in the placebo group did not. In order to investigate the possibility that the observed mortality effect of terlipressin was, at least in part, due to the nitroglycerin, an additional sub‐group analysis was performed including only the studies that did not use nitrates. In this sub‐group of studies there was a statistically significant mortality benefit in favour of terlipressin (relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.93). In fact, the relative risk is identical to that of all the studies together, with a slightly wider confidence interval. Nitrates were added to terlipressin empirically in an attempt to avoid the peripheral vasoconstrictive adverse reactions that were observed with vasopressin. However, these adverse reactions were not observed in the studies included in this meta‐analysis that did not use nitrates. In addition, there is no evidence that nitrates offer any benefit in acute variceal bleeding and in fact a recent study showed that when nitrates were added to somatostatin they induced more adverse effects (Junquera 2000). Therefore, nitrates should not routinely be added to terlipressin in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding.

Only one randomised controlled study was identified that compared terlipressin with endoscopic treatment, in this case sclerotherapy. Nevertheless, this was a high quality, multi‐centre trial and in fact was the largest single study in this review. There was no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and sclerotherapy in any of the outcomes examined: mortality, failure of initial haemostasis, rebleeding, emergency procedures, blood transfusions and length of hospitalisation. In the case of mortality there was a trend in favour of sclerotherapy (relative risk 1.49) which did not reach statistical significance. This is an important study because some centres around the world may not have skilled gastroenterologists available to perform 24‐hour, emergency therapeutic endoscopy whereas terlipressin administration could be possible almost anywhere. Assuming a baseline mortality of 25% in the terlipressin group then this study was powered to detect an absolute difference in mortality between terlipressin and sclerotherapy of 14% (alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.80). The study failed to show this, however. Larger studies will be needed to evaluate whether a smaller difference does indeed exist between the two treatments. In addition, the endoscopic treatment of choice is thought to be band ligation as opposed to sclerotherapy (Laine 1995) and, unfortunately, no studies comparing terlipressin to band ligation were identified.

Three trials comparing terlipressin to somatostatin were identified, of which two were high quality studies that contributed most of the weight in the meta‐analysis. The studies included a total of 302 patients and meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference between terlipressin and somatostatin in mortality or any of the secondary outcomes. As with the case of the terlipressin versus endoscopic treatment group, one cannot exclude that a small difference does exist between terlipressin and somatostatin which cannot be detected due to the relatively small number of patients involved.

Meta‐analysis of the trials in three groups (terlipressin versus balloon tamponade, terlipressin versus octreotide and terlipressin versus vasopressin) did not show any statistically significant differences between terlipressin and the other treatments in mortality or any of the secondary outcomes, with the exception of failure of initial haemostasis where there was a benefit in favour of octreotide. However, it is difficult to draw any reliable conclusions from these results: there was only a small number of patients involved in each group and all eleven trials in these three groups were graded low quality by the Jadad scale.

Terlipressin was initially developed as a synthetic analogue of vasopressin that would be both safer and easier to administer by intermittent injections rather that continuous intra‐venous infusion. It is generally very difficult to decide whether a complication that occurred during the treatment of a patient with acute variceal bleeding was due to an adverse reaction to the treatment or to the disease itself. Even allowing for this problem only six deaths out of 798 terlipressin‐treated patients were attributed to terlipressin compared to five deaths out of 811 patients in the control groups. Of these, four deaths in each group (terlipressin and placebo) occurred in Levacher 1995 and were attributed to 'fibrinolysis'. One can question, however, how any form of coagulopathy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis can be confidently attributed to a vasoactive agent as opposed to the disease itself. There was no difference between terlipressin and any of the comparison groups in adverse events causing withdrawal or death except for the terlipressin versus vasopressin group where more withdrawals occurred in the vasopressin group. Terlipressin was continued for up to seven days in Pedretti 1994 without any serious adverse reactions. This suggests that terlipressin may indeed be a safer drug than vasopressin and appears to be as safe as the other treatments used in variceal bleeding.

The seven studies that compared terlipressin to placebo span a time period of 14 years (1986‐2000): are the results of these studies relevant to the 'modern' management of acute oesophageal variceal bleeding? In the last 10 to 15 years two new trends have emerged, in addition to the use of vasoactive agents. Firstly, in centres that have the capability, urgent endoscopic treatment is performed in the form of either sclerotherapy or banding. These endoscopic treatments have been shown to improve control of bleeding and rebleeding but they have not been shown to reduce mortality. In addition, many centres around the world do not have the capability of rapid, 24‐hour emergent therapeutic endoscopy with expert personnel. Only three of the seven studies involved urgent endoscopic treatment and as mentioned above even in these studies there was a mortality benefit that approached statistical significance (relative risk 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.04). Therefore, terlipressin may reduce mortality both when used alone and when added to endoscopic treatment. In fact, it has been suggested (Levacher 1995; Avgerinos 1997), that the use of vasoactive agents and endoscopic treatments may be complementary: early use of vasoactive agents may reduce the amount of bleeding and therefore make subsequent endoscopic treatment easier and more effective. Secondly, a trend has emerged for additional endoscopic treatments (usually banding) during the initial hospitalisation. None of the seven terlipressin versus placebo trials involved such treatments. However, the effect of this practice has not yet been formally evaluated in randomised clinical trials and, therefore, it does not necessarily influence the relevance of the seven included trials to modern evidence‐based management of variceal bleeding.

The optimal duration of terlipressin administration is controversial. This issue could not be addressed in this systematic review by sub‐group analysis because all studies used terlipressin for less than 48 hours, except for two studies that used terlipressin for five days: Patch 1999 which was a comparison of terlipressin versus placebo and Cooperative 1997 which compared terlipressin to sclerotherapy. Only two studies have directly compared 48‐hour to seven day administration of terlipressin: Arcidiacono 1992 and Fiaccadori 1993. However, all the patients in the study by Arcidiacono 1992 have been included in the study by Fiaccadori 1993. This study involved 596 patients with acute variceal bleeding, who, after receiving terlipressin for 48 hours were randomised to either continue terlipressin for another five days or control. There was a statistically significant improvement in rebleeding in the group that continued terlipressin, but not in mortality. However, the study was not described as blinded and did not describe a method of randomisation or concealment of treatment allocation. It would, therefore, be graded as a low quality study both using the Jadad scale and based on the lack of concealment of treatment allocation.

This study cannot answer the question of which vasoactive agent is most effective because there was only a very small number of high quality studies that directly compared terlipressin with somatostatin analogues (somatostatin, octreotide, or vapreotide). However, no somatostatin analogue has ever been shown to improve mortality either in single trials or in meta‐analysis. In fact, a recently revised systematic Cochrane Review (Gøtzsche 2002), which included 12 trials of somatostatin analogues versus placebo/no intervention (ten of which included endoscopic treatment for all patients, just as in the present Review) with an even greater total number of patients than the trials presented here, did not show any mortality benefit for somatostatin analogues. Terlipressin is therefore the only vasoactive agent that has ever been shown to reduce mortality in acute variceal bleeding.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

On the basis of a 34% relative risk reduction in mortality, terlipressin should be considered to be effective in the treatment of acute variceal haemorrhage. In terms of serious adverse reactions, there was no difference between terlipressin and either placebo or octreotide or somatostatin suggesting that it may be as safe as the other commonly used vasoactive agents. However, since no other vasoactive agent has been shown to reduce mortality in single studies or meta‐analyses, terlipressin might be the vasoactive agent of choice in acute variceal bleeding.

Implications for research.

Ideally it would have been useful to have more trials comparing terlipressin to placebo, in which all patients receive endoscopic treatment. However, given that in this subset of trials this review demonstrates a mortality benefit that closely approaches statistical significance and that in all the studies that compare terlipressin to placebo this review does demonstrate a statistically significant mortality benefit, it may be unethical to perform more studies comparing terlipressin versus placebo.

The most useful future studies would compare terlipressin with somatostatin or octreotide and treat all patients with endoscopic treatments, preferably with endoscopic band ligation. Such studies would help decide which vasoactive agent is the safest and most effective, in the modern era of endoscopic treatment of variceal bleeding.

Feedback

Terlipressin for acute esophageal variceal hemorrh

Summary

Comment on the terlipressin Review

The reviewers found a statistically significant reduction in mortality with terlipressin compared with placebo. They regard this result as convincing and conclude that it may be unethical to perform more studies comparing terlipressin versus placebo.

I disagree on both points. The reviewers base their conclusion primarily on five high‐quality trials. But they define high quality as 3 points on the 5 point Jadad scale. According to their table of included studies, it can be discussed whether any of the trials had adequate concealment of allocation, perhaps with the exception of the Walker study (pre‐packed numbered boxes, but the randomisation method was not described and it reported on only 3 versus 8 deaths). Adequate concealment of allocation is the most important safeguard against bias and trials that do not report this, exaggerate the effect by 30%, on average, measured as the odds ratio (Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001; 323: 426). Furthermore, the trials were small and the reported results could therefore have been influenced by publication bias (the drug manufacturers did not identify any additional studies, but they are usually not willing to share negative, unpublished trial reports with meta‐analysts). Finally, none of the trials appeared to have described withdrawals/drop‐outs, and post‐hoc exclusions of rather few randomised patients can change the results of small trials substantially.

The reviewers' review demonstrates, once again, that the use of the Jadad scale for quality assessment is a risky affair that should be avoided, e.g., it does not give any points to adequate concealment. As far as I can see, high‐quality studies comparing terlipressin and placebo are needed and the reviewers should modify their review and its conclusions. I found a similar reduction in tranfusion needs with somatostatin analogues in my updated Cochrane review as the reviewers found in theirs for terlipressin, but I did not find a significant reduction in mortality (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.74‐1.24) although the number of included patients in my high‐quality trials (concealed allocation and double‐blind) was 967 as compared to only 357 in the terlipressin review. The reviewers found that one would need to treat only 8 patients with terlipressin instead of placebo to prevent one death. It is rather implausible to see such a dramatic effect when the effect of terlipressin is to spare one unit of blood per patient.

Peter C. Gøtzsche, December 2001

Reply

I would like to thank Dr Gøtzsche for his comments regarding:

1. Quality assessment of included studies.

In our meta‐analysis we employed the Jadad scale for quality assessment, using a cutoff of ·3 points to define a 'high quality' study. We agree that the Jadad scale does not capture all aspects of methodological quality (1‐4); in particular it does not include a description of concealment of randomisation. Nevertheless, for each study included in the review we clearly described each component of study quality, including concealment of treatment allocation, both in the text and in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'. The categorization of studies into 'high quality' and 'low quality' based on the Jadad scale, was employed only to enable us to investigate whether the results in favour of terlipressin were driven primarily by studies with lower score and potentially higher bias. This was not the case. In order to clarify this point, the relevant section under 'Methods' has been changed as follows: "For each study we described important components of methodological quality including concealment of allocation, generation of a randomisation sequence, double‐blinding, and description of losses to follow‐up. Furthermore, the Jadad scale was employed in order to allow us to investigate whether our results were primarily driven by low quality (and potentially high bias) studies. The Jadad scale (Jadad 1994) was chosen a priori both because it had been validated to be able to separate studies into 'high quality score' (low bias) studies and 'low quality score' (high bias) studies and also because studies dealing with digestive diseases were included in the validation (Jadad 1996; Moher 1998)".

Dr Gøtzsche favours, instead, the use of reported concealment of allocation to define a 'high quality study', quoting as evidence the BMJ article by Jüni et al. (4), which in turn quotes the study by Schulz et al. (2), demonstrating empirically that studies which report adequate concealment of allocation have a mean effect of the experimental intervention which is about 30% closer to the null effect compared to studies which did not report adequate concealment of allocation. However, an identical method of empiric 'validation' was employed for the Jadad scale (3) (using a cutoff of ·3 points), which demonstrated an almost identical 34% difference between 'high quality score' trials (i.e., scoring 3‐5 points) and 'low quality score' studies (i.e., scoring 1‐2 points). Therefore, based on the published data (1‐4), there is little to distinguish reported concealment of allocation from the Jadad scale, as methods of dividing up trials into potentially low and high bias studies for the purpose of investigating to what extent the results of a meta‐analysis may be driven by high‐bias studies. We decided a priori to choose the Jadad scale instead of reported concealment of allocation because:

a. The study validating the Jadad scale (3) used studies of gastrointestinal diseases for the validation, whereas the study validating reported concealment of allocation (2) used only studies of obstetrics and gynaecology. Since the publication of our Review, the study by Kjaergard et al. has been published (4), evaluating both quality components and the Jadad scale in a number of different therapeutic areas. Although this study finds several shortcomings of the Jadad scale (exclusion of the allocation concealment component; large weight of double blinding in the scale and hence considerable overlap between this component and the Jadad scale), Kjaergard et al. (4) also demonstrates that the Jadad scale meaningfully divides trials into those with significant overestimation of intervention effects and those without significant overestimation. These findings are in perfect agreement with the results of Jüni et al. based on one meta‐analysis (5).

b. Since there has been a lot of emphasis on reporting concealment of allocation since the publication of Schulz's influential study in 1995, it is much more likely for studies published after 1995 to report concealment of allocation, than for studies of identical quality published before 1995. Therefore, use of reported concealment of allocation as the method of quality assessment, would lead to underestimating the quality of studies published before 1995, relative to studies published after 1995.

In summary, we do not think that there is convincing data, or consensus, that the best way to dichotomize a group of studies with respect to their 'quality' is based on the report of concealment of allocation. As explained above the Jadad scale is a perfectly adequate and validated tool for this purpose and we chose it a priori, as evidenced by the description of the protocol of our systematic review which was published long before the review was performed. Furthermore, the fact that the combined relative risk of the studies with a high Jadad score included in our review was not further away from the null than the combined relative risk of all included studies, suggests that our results were not driven by low quality and potentially high bias studies. We think that this adds even more credibility to our conclusions that terlipressin is superior to placebo.

In response to comments received from Dr Gøtzsche, we performed an additional post‐hoc analysis in which the seven included trials were sub‐divided based on whether they described adequate concealment of treatment allocation or not. Even among the two trials that described adequate concealment (Levacher 1995, Walker 1986), terlipressin was associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality compared to placebo (relative risk 0.56, 95% CI 0.33‐0.93). There was no statistical heterogeneity between these two studies. This post hoc analysis has now been included in the review.

2. "the trials were small".

The fact that the trials are small does not necessarily mean that the trials were biased. Kjaergard et al. (4) demonstrated that small trials with adequate double blinding or generation of a random sequence on average do not overestimate the effect size. The studies included in our review that were graded 'high quality' by the Jadad were all double blind and some additionally described adequate generation of randomisation sequence or concealment of allocation. Therefore, despite their small size they would not be expected to exaggerate their results away from the null.

3. Results "could have been influenced by publication bias".

Publication bias is, of course, a concern in any meta‐analysis. However, there is no reason to suspect that publication bias has played a significant role in our meta‐analysis. First, we included both fully published trials as well as trials published only in abstract. Second, we made every attempt possible to identify unpublished data, including contacting authors and the manufacturers and finding out about studies published only in abstract. Third, funnel plots of odds ratio versus study size (or standard error) for the studies of terlipressin versus placebo, do not suggest publication bias.

4. Description of withdrawals/drop‐outs.

It is true that only a minority of the included studies explicitly described withdrawals/drop‐outs. Nevertheless, reporting withdrawals/drop‐outs is a component of the Jadad scale and, therefore, this aspect of quality has already been incorporated in our overall estimate of quality assessment. It is also possible that most studies failed to report withdrawals/drop‐outs, because they did not have any withdrawals/drop‐outs, given the relatively short follow‐up period: three out of seven studies followed patients until discharge, one up to 5 days, one up to 30 days, and two up to 42 days.

5. Inconsistency with results of somatostatin.

Dr Gøtzsche points out an apparent "inconsistency" namely that the somatostatin and terlipressin meta‐analyses demonstrated similar reductions in blood transfusion requirements, yet terlipressin appeared to have an effect on mortality whereas somatostatin did not. I think there are a number of flaws to this argument. Firstly, we did not quantify in our meta‐analyses an overall mean difference between terlipressin and control groups in blood transfusion requirements. This was impossible to do in any meaningful way because some studies reported means and others medians, some studies reported total number of transfusions and others reported transfusions/day, and finally it was almost impossible to say whether studies measured the total number of transfusions throughout the hospitalisation or transfusions performed during the terlipressin infusion period. Therefore, it is impossible to say that terlipressin and somatostatin resulted in similar reductions in blood transfusion requirements. Even if that could be ascertained with any degree of accuracy, one would need to make the additional assumptions that reductions in blood transfusions are proportional to (or at least, related to) reductions in mortality, and that the relation between blood transfusion reductions and mortality reductions is the same for terlipressin and somatostatin. Both these assumptions are questionable.

6. "the authors base their conclusions primarily on five high quality studies…it can be discussed whether any of the trials had adequate concealment of allocation…trials were small…could have been influenced by publication bias…the authors should modify the review and its conclusions".

Dr Gøtzsche questions our conclusion that terlipressin is superior to placebo for acute variceal oesophageal bleeding. We have attempted to address his concerns about concealment of treatment allocation, small trial size, and publication bias above. Furthermore, we would like to make the following points in support of our conclusion:

a. The effect of terlipressin was consistent across all outcomes measured (mortality, blood transfusions, failure of haemostasis, rebleeding, procedures required for uncontrolled bleeding).

b. The effect of terlipressin was similar in the sub‐group of 'high quality' studies (as measured by a validated instrument, the Jadad scale) and in all studies combined.

c. Five out of the seven included studies had sufficient features of methodological quality to score 3 or more points on the Jadad scale. Although concealment of treatment allocation was less often reported this may be influenced by the fact that five out of the seven included studies predated the publication of Schulz's article on the importance of reporting concealment of allocation. The other two included studies have been published only in abstract and therefore could not be judged in this respect. Overall, we do not think that the quality of the included studies is such as to question our conclusions.

7. What should future studies address?

It would of course be welcome if more high quality studies of terlipressin versus placebo were available to help us more accurately define the role of terlipressin. However, studies performed over the last 15 years have consistently suggested benefits favouring terlipressin in mortality as well as in secondary outcomes. Furthermore, terlipressin is safe and relatively cheap compared to the total costs of hospitalisation in these patients. For these reasons, we still think that studies directly comparing vasoactive agents with each other are currently more useful than studies comparing vasoactive agents with placebo.

References

1. Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001; 323:42‐46.

2. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408‐412.

3. Moher D, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P, Klassen TP. Does quality of reports of randomized trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta‐analyses? Lancet 1998;352:609‐613.

4. Kjaergard LL, Willumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomised trials in meta‐analyses. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:982‐989.

5. Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta‐analysis. JAMA 1999;282:1054‐1060.

George Ioannou, February 2002

Contributors

Comment: Peter C. Gøtzsche ‐ e‐mail: <p.c.gotzsche@cochrane.dk> Response: George Ioannou ‐ e‐mail: <GeorgeI@medicine.washington.edu>

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

All the authors of the studies who kindly provided additional and confirmatory data.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Terlipressin versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality | 7 | 443 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.49, 0.88] |

| 1.1 High quality studies (Jadad score 3‐5) | 5 | 357 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.45, 0.84] |

| 1.2 Low quality studies (Jadad score 1‐2) | 2 | 86 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.45, 2.12] |

| 2 Number failing initial hemostasis | 7 | 443 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.32, 0.70] |

| 2.1 High quality studies (Jadad score 3‐5) | 5 | 357 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.30, 0.70] |

| 2.2 Low quality studies (Jadad score 1‐2) | 2 | 86 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.23, 1.37] |

| 3 Number with rebleeding | 4 | 196 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.49, 1.96] |

| 3.1 High quality studies (Jadad score 3‐5) | 3 | 165 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.46, 1.87] |

| 3.2 Low quality studies (Jadad score 1‐2) | 1 | 31 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.19 [0.12, 317.97] |

| 4 Number of procedures (tamponade, sclerotherapy, surgery or TIPS) required for uncontrolled bleeding/rebleeding | 6 | 388 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.38, 0.88] |

| 4.1 High quality studies (Jadad score 3‐5) | 5 | 357 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.34, 0.81] |

| 4.2 Low quality studies (Jadad score 1‐2) | 1 | 31 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [0.41, 8.88] |