Abstract

A protecting group-free strategy is presented for diastereo- and enantioselective routes that can be used to prepare a wide variety of Z-homoallylic alcohols with significantly higher efficiency than is otherwise feasible. The approach entails the merger of several catalytic processes and is expected to facilitate the preparation of a wide range of bioactive organic molecules. More specifically, Z-Chloro-substituted allylic pinacolatoboronate is first obtained through stereoretentive cross-metathesis between Z-crotyl–B(pin) (pin = pinacolato) and Z-dichloroethene, both of which are commercially available. The organoboron compound may then be used in the central transformation of the entire approach, namely, an α-, and enantioselective addition to an aldehyde, catalyzed by a proton-activated, chiral aminophenol-boryl catalyst. Catalytic cross-coupling can then furnish the desired Z-homoallylic alcohol in high enantiomeric purity. The olefin metathesis step can be carried out with substrates and a Mo-based complex that can be purchased. The aminophenol compound that is needed for the second catalytic step can be prepared in multi-gram quantities from inexpensive starting materials. A significant assortment of homoallylic alcohols bearing a Z-F3C-substituted alkene can be prepared with similarly high efficiency and regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity. What is more, trisubstituted Z-alkenyl chloride moiety can also be accessed with similar efficiency albeit with somewhat lower α-selectivity and enantioselectivity. The general utility of the approach is underscored by a succinct and protecting group-free, and enantioselective total synthesis of mycothiazole, a naturally occurring anticancer agent through a sequence that contains a longest linear sequence of nine steps (12 steps total), seven of which are catalytic, and generates mycothiazole in 14.5% overall yield.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Homoallylic alcohols are used widely in chemical synthesis, and many past studies have led to the development of catalytic methods that generate these entities efficiently and in high enantiomeric purity.1 However, several key shortcomings remain unaddressed, one of which is the efficiency and enantioselectivity with which a Z-homoallylic alcohol – especially those lacking an allylic substituent – can be accessed. These fragments can be found in numerous bioactive molecules, such as antitumor agent macrolactin A,2 anticancer and antifungal agent disorazole C1,3 antitumor mycothiazole4, and cytotoxic and antimalarial bipinnatin J (Scheme 1).5

Scheme 1. Representative Biologically Active Natural Products with One or More Z-Homoallylic Alcohol Derived Fragments.

A common strategy for preparation of enantiomerically enriched Z-homoallylic alcohols entails initial synthesis of the derivative that contains a monosubstituted alkene, either by diastereoselective addition of an unfunctionalized allyl unit to an enantiomerically enriched aldehyde,6 or by an enantioselective process that involves an achiral aldehyde.7 Typically, after alcohol protection, the monosubstituted alkene is converted to a Z-alkenyl iodide by oxidative alkene cleavage and a Wittig reaction (Scheme 2a).8 Another approach entails catalytic enantioselective aldol addition followed by secondary alcohol protection, reduction of the ester (to alcohol), oxidation of the primary alcohol to an aldehyde, and reaction with a halogen-substituted phosphonium salt (Scheme 2a).2c,8 The Z-alkenyl halide may then be transformed to a protected form of a Z-homoallylic alcohol by catalytic cross-coupling (stereoretentive). Alternative strategies include enzymatic kinetic resolution of an allylic alcohol and subsequent transformation to a homoallylic alcohol.9

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched Z-Homoallylic Alcohols: State-of-the-Art and The Aim of This Study.

aReactions (1a →3a) were carried out under N2 atm. Conv was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields are for purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

Z-Homoallylic alcohols that are without an allylic substituent and contain an alkenyl halide moiety may be prepared via enantiomerically enriched allyl boronates,10 but such strategies require extremely low temperatures, several days of reaction time, and/or do not furnish products in high enantiomeric ratio (er; Scheme 2b). There are a limited number of protocols that directly furnish Z-homoallylic alcohols.11 Again, one involves the use of a chiral auxiliary,11a and the other is a catalytic kinetic resolution for which a racemic secondary allyl–B(pin) compound is needed (Scheme 2b).11b Notably, the applicability of these approaches is confined to products that contain a simple n-alkyl-substituted olefin (mostly Me).

Despite the above advances, significantly more efficient routes and more broadly applicable strategies are needed, as is evident from two representative cases (Scheme 2c), performed in the context of natural product total synthesis. One relates to preparation of a segment of disorazole C1 (Scheme 2c).3d To access products in high stereochemical purity, stoichiometric amounts of an enantiomerically pure allylic silane reagent were required, and it was necessary to mask the hydroxy group prior to a cross-metathesis reaction that generated the derived Z-alkenyl boronate. Five steps, only one of which is catalytic, were therefore needed to convert the aldehyde to the desired Z-homoallylic alcohol.12 In the second instance, relating to the only reported enantioselective synthesis of mycothiazole (2015; Scheme 2c),4e preparation of the requisite β-siloxy aldehyde demanded 13 steps; this was followed by a Wittig reaction that had to be carried out with 10 equivalents of hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) in order for it to be highly Z-selective.

To design a more general and efficient catalytic strategy, we envisioned a route that would entail synthesis of an enantiomerically enriched homoallylic alcohol containing a terminal alkene followed by catalytic stereoretentive cross-metathesis to form a Z-alkenyl halide. This would provide a convenient diversification point for generating a range of Z-homoallylic alcohols through catalytic cross-coupling. We had two major concerns, however: protection of the alcohol would be necessary (Mo-based catalysts must be used as Ru complexes are ineffective12), and cross-metathesis is typically inefficient with alkenes that carry a β substituent, especially a sterically demanding one. To probe, we prepared homoallylic silyl ether 2 from aldehyde 1a4i–j (Scheme 2d), based on a reported catalytic enantioselective protocol (99:1 er).7a,f–h Subsequent studies revealed that under the best of circumstances, namely, with monoaryloxide pyrrolide (MAP) complex Mo-1a, cross-metathesis between 2 and Z-1,2-dichloroethene12,13 does not proceed beyond ~50% conversion (5.0 mol % loading; Scheme 2d). We could isolate Z-homoallylic alcohol 3a in only 34% yield and 98:2 Z:E ratio after silyl group removal. If the silyl ether form of 3 were desired, separating it from unreacted 2 would be difficult.

We reasoned that a more attractive option would be to combine a catalytic enantioselective allyl addition to an aldehyde and catalytic cross-metathesis in a different way: Z-allylic boronate 4a might be synthesized first and then used in an a- and enantioselective addition to aldehyde 1a (Scheme 2e). The latter step could be promoted by a chiral, proto-activated aminophenol-boryl catalyst,14 generating 3a directly. Ensuing catalytic cross-coupling reactions could then be used to establish a concise and protecting group free total synthesis of mycothiazole, a natural product recently prepared in 26 total steps (longest linear sequence = 20 steps; 1.8% overall yield).4e

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. α-Selective Additions of a Z-Cl-Substituted Allylboronate to Aldehydes.

2.1.1. Mechanistic considerations.

Since the discovery of chiral aminophenol-boryl catalysts,14 we have been focused on additions to various aldimines14,15 and ketones.16 Initial studies with aldehydes had shown that such transformations, although efficient, are minimally enantioselective. Considering that stereodifferentiation in additions to ketones is typically more challenging (smaller size difference between substituents), and because aldehydes are sterically less encumbered and more reactive (vs imines or ketones), we presumed that low er was due to fast and competitive non-catalytic addition of allylic boronates. To check the validity of this assumption, we examined a process with a deuterium-labeled allyl–B(pin) (Scheme 3a). If the reason for low er is fast and competitive uncatalyzed addition, a γ-selective process that proceeds via a six-membered transition structure, then the D atoms will be found attached to the terminal alkenyl carbon; if the catalytic process, which is α-selective, is the major pathway, then the D atoms will be at the sp3-hybridized methylene site. In the event, we established that our hypothesis was incorrect (Scheme 3a): the catalytic process is faster (vs non-catalytic) and is minimally enantioselective.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched Homoallylic Alcohols: The Initial Studies.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm. Conv was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

The above findings were somewhat surprising because, typically, it is easier to achieve high enantiofacial selectivity with an aldehyde, where the difference between the size of the two carbonyl substituents is more substantial (vs a ketone). Why would additions to aldehydes afford products with low er but not when aldimines (phosphinoyl- or Boc-protected)15a–c or ketones,16 including trifluoromethyl ketones,16a,c–d are involved? Examination of stereochemical models, which are based on former investigations, suggests that this is likely because a small hydrogen atom substituent renders reaction via II (Scheme 3a) too competitive when I is involved. We therefore wondered whether reactions with Z-allylic boronate 4a might prove to be more enantioselective. We considered this possibility based on the initial formation of chiral allylic boronate V, which would be generated by the reaction of III with 4a via IV (Scheme 3b).15b–c,16 c The main issue therefore was: Could it be that transformation via VI, which would afford an E-homoallylic alcohol, suffers from sufficient steric repulsion compared to VII to allow one to access a Z-homoallylic alcohol more enantioselectively?

2.1.2. Identification of an optimal catalyst.

Homoallylic alcohol 3b (Scheme 4) was indeed generated with considerably higher enantioselectivity when 4a was used in the presence of 2.0 mol % ap-1 (87:13 er) or related derivatives ap-2 and ap-3 (91:9 and 92:8 er, respectively). The transformations afforded the Z-alkenyl chloride isomer preferentially (97:3–98:2 Z:E) and were uniformly and exceptionally α-selective, particularly when the latter two aminophenols were involved (98:2 α:γ selectivity, respectively). We obtained higher er when we utilized hydroxyadamantyl-substituted ap-4 and ap-5, with the latter delivering 3b in 95% yield, complete α selectivity, 98:2 Z:E ratio, and 95:5 er (Scheme 4). The necessary enantiomerically pure amino alcohol, which is used in the commercial synthesis of saxagliptin,17 is readily available and less expensive than the parent adamantyl-containing variant (no hydroxy group). Control experiments indicate that the free hydroxy unit is not required, as it does not impact the outcome (e.g., reaction with the derived methyl ether aminophenol was similarly efficient and selective).

Scheme 4. Identification of an Effective Catalyst for α-Selective Addition with Cl-Substituted Allylic Boronate 4aa.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm. Conv (>98% in all cases) and α:γ selectivity was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields correspond to purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

2.1.3. Scope.

The method has considerable scope (Scheme 5). Aryl aldehydes, including those that contain a sterically demanding ortho substituent undergo reaction readily; for example, 3c and 3d were isolated with complete α selectivity, 83% and 86% yield, 98:2 and >98:2 Z:E ratio, and 95:5 and 94:6 er, respectively. The same applied to m- and p-substituted aryl aldehydes (3e-j) and those containing a heterocyclic moiety (3k-l). Notably, the reaction leading to 3g proceeded with complete chemoselectivity (<2% addition to ketone). Enals, as represented by homoallylic alcohols 3m and 3n, and alkyl-substituted aldehydes also emerged as suitable substrates (3o-p). Whereas 3o, derived from addition to an n-alkyl-substituted aldehyde was less enantioselective (79:21 er), reaction with cyclohexyl aldehyde afforded 3p in 93:7 er.

Scheme 5. Catalytic Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched Z-Cl-Substituted Homoallylic Alcoholsa.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm; Conv (>98% in all cases) and α:γ selectivity was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields correspond to purified a isomer products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). bPerformed at 40 °C for optimal efficiency; 40–50% conv was observed at 22 °C. Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

The α selectivities and Z:E ratios were uniformly high, and purified homoallylic alcohols were isolated in 82–96% yield (pure α-addition isomers in all cases). However, there were some variations. Reactions involving p-keto-, p-methoxy-, and p-thiomethyl-substituted aryl aldehydes afforded the corresponding products with lower enantioselectivity (3g-i; Scheme 5). The precise reason for this selectivity trend, which control experiments show is not due to adventitious uncatalyzed reaction, is unclear at the present time. The lower α selectivity in the case of cyclohexyl-substituted 3p is probably because adventitious borotropic shift15b is more competitive with addition to the relatively hindered and somewhat less electrophilic aldehyde. Still, the γ-addition isomer was easily removed and the desired product was obtained in 80% yield.

Two additional points are worthy of note:

The reaction with an n-alkyl substrate, leading to 3o, was less stereo-differentiating, a trend that is consistent with the proposed stereochemical model, as represented by complex VIII.

Use of excess aldehyde (1.5 equiv) is needed for maximum efficiency and α selectivity. For example, with 1.0 equiv of the aldehyde, under otherwise identical conditions, we obtained 3b and 3o in 67% and 56% yield (pure a isomer) and 78:22 and 73:27 α:γ ratio, respectively (vs 95% and 88% yield, and >98:2 and 95:5 α:γ ratio, respectively). This likely arises from less competitive borotropic shift prior to C–C bond formation, which would generate the corresponding γ-isomer. [As shown below (Scheme 8b), >95% of the unreacted aldehyde can be recovered].

Scheme 8. Catalytic Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched Z-F3C-Substituted Homoallylic Alcoholsa.

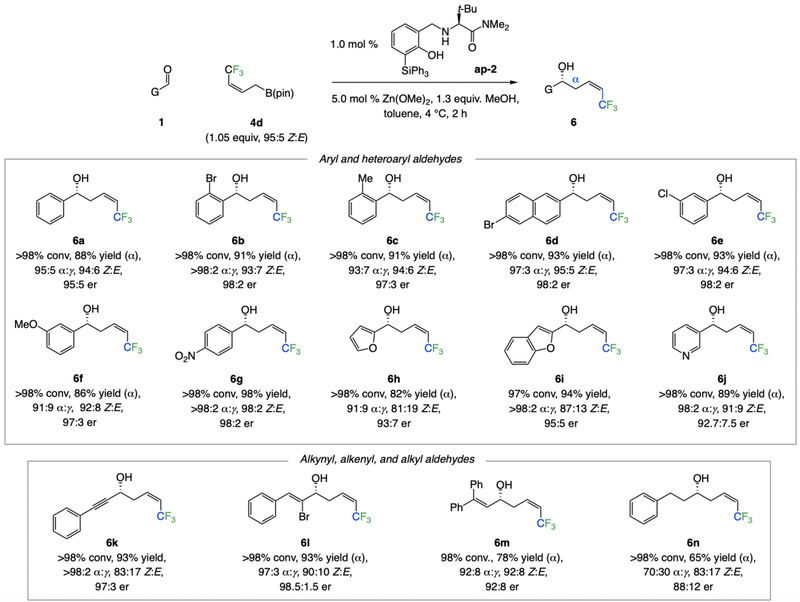

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm; Conv (>98% in all cases) and α:γ selectivity was determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields correspond to purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

Transformations with chiral (enantiomerically pure) aldehydes, an important but particularly challenging set of substrates,18 were carried out to enhance the scope of the approach as well as reveal additional mechanistic attributes (Scheme 6). Homoallylic alcohol 3q was isolated in 81% yield, 98:2 Z:E ratio and 83:17 dr. Product 3r was obtained in 85% yield, 97:3 α:γ ratio, 98:2 Z:E selectivity, and 97:3 dr. In contrast, when the alternative aldehyde enantiomer was used, while 3s was obtained with virtually the same regio- and stereoselectivity, the reaction was significantly less efficient (>98% vs 49% conv and 85% vs 32% yield for 3r and 3s, respectively). These findings show that, despite more severe steric pressure in the mismatched mode of addition represented by X (vs IX, based on the Felkin-Anh model), the process remains catalyst-controlled.

Scheme 6. Reactions with Enantiomerically Pure Chiral Aldehydesa.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm; α:γ selectivity was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields correspond to purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

An unusual feature of the additions to sterically demanding and less reactive chiral aldehydes (Scheme 6) is that significantly higher α:γ ratios were observed in the absence of MeOH. For example, 3r and 3s were generated with 53:47 and 32:68 α:γ selectivity with MeOH present (1.3 equiv), which led to considerably lower yields (51% and 14% of α-addition product, respectively; Z:E ratios and dr remained the same).19 While, as described previously,14 a proton source ensures rapid generation of the requisite aminophenol-boryl catalyst, we often find that residual moisture can serve as a suitable proton source. The present data indicate that in cases involving less reactive substrates, excess alcohol can cause borotropic shift of the initially generated chiral allylic boronates to occur faster than C–C bond formation (see Scheme 7b), resulting in lower α:γ ratios. Precisely how an alcohol can facilitate borotropic shifts requires more detailed investigations. Nonetheless, it is plausible that an increase in medium polarity and/or H-bonding with one of the Lewis basic sites within the chiral allylic boronate, as attributed formerly to the Lewis acidic Zn(II) cation,15b can lower the barrier to the formation of the less sterically hindered isomer.

Scheme 7. Additions with Trisubstituted Allylic Boronatesa.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm; Conv (>98% in all cases) and α:γ selectivity was determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields correspond to purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

Trisubstituted alkenyl chlorides may be used with similarly high efficiency and stereochemical control to afford valuable Z-trisubstituted homoallylic alcohols (e.g., see bipinnatin J, Scheme 1). For instance, allylic boronate 4c (Scheme 7a) was prepared (98:2 Z:E) from a commercially available alkenyl bromide and a boronic acid by a fully catalytic sequence of cross-coupling, hydroboration, and stereo-retentive cross-metathesis with MAP complex Mo-1b and via allylic boronate 4b.20 Homoallylic alcohols 5a-c, containing a trisubstituted alkenyl halide, were then obtained in 54–77% yield, 97:3–98:2 Z:E ratio, and 86:14–95:5 er. A variety of other trisubstituted homoallylic alcohols may be obtained through catalytic cross-coupling with 5a-c. Furthermore, the majority of the reagents, substrates, transition metal complexes and ligands are commercially available (i.e., many alkenyl boronic acids, pinacolatoborane, 1,2-E-dichloroethene, the Pd- and Ni-based complexes).

The lower α:γ selectivity in the reactions with a trisubstituted allylic boronate may be rationalized based on the relative rate of reaction of the initially formed branched/more hindered XI (Scheme 7b) compared to its isomerization to the lower energy XII (less hindered and more substituted alkene). Transformation via XII would generate the γ-addition isomer. Moreover, based on stereochemical models, the presence of a C2-methyl group within the allylic boronate leads to more steric pressure in XIII (Scheme 7c), allowing alternative modes of addition to become more competitive, resulting in lower er. While the precise identity of the latter minor pathways is unclear at the present time, it is noteworthy that, despite the increased steric repulsion in these latter reactions, products are formed in high Z:E ratios; this indicates that pathways leading to the E-alkenyl chlorides (XIV, Scheme 7c) remain less favored.

2.3. α-Selective Additions of a Z-F3C-Substituted Allylboronate to Aldehydes.

The present approach is not limited to the formation of Z-alkenyl chlorides. Another important class of homoallylic alcohols that can be readily accessed consist of those that contain a Z-F3C-substituted alkene (Scheme 8), a functional unit that has recently been used to generate, with high stereoselectivity, desirable and versatile allyl boronates21 and allyl silanes21c that contain a 1,1-difluoroalkene moiety. These transformations, involving the use of just 1.0 mol % ap-222 as the optimal ligand and allylic boronate 4d,23 which may also be accessed through catalytic stereoretentive cross-metathesis, are broadly applicable as well, affording the desired aryl- (6a-g), heteroaryl- (6h-j), alkynyl- (6k), alkenyl- (6l), or alkyl-substituted (6m-n) products in 65–98% yield (often of the pure a isomer), 70:30 to >98:2 α:γ selectivity, 81:19–98:2 Z:E selectivity, and 88:12–98:2 er.

2.4. A Concise, Protecting Group-Free, and Enantioselective Synthesis of Mycothiazole.

We began by synthesizing multigram quantities of aldehyde 1a and Z-chloro-substituted allylic boronate 4a (Scheme 9a). The former (1a) was synthesized (1.76 g) starting from commercially available 7 via 8 based on a procedure by Cossy4i–j in three steps and 77% overall yield.24 To prepare 4a, with 10 mol % pinacolatoborane (HB(pin), to remove residual moisture13) and with commercially available MAP complex Mo-1c, cross-metathesis was efficient, affording 4a in 81% yield and 98:2 Z:E. It is worth emphasizing that allylic boronate 4d and Z-1,2-dichloroethene are commercially available and did not require any purification before use. When monoaryloxide chloride (MAC) species Mo-223 was used (Scheme 9a), under otherwise identical conditions, 1.6 mol % loading was sufficient for us to access 4.3 g 4a in higher yield (purified by distillation) and similar stereochemical purity (96% yield, >98:2 Z:E).

Scheme 9. Application to a Concise Total Synthesis of Mycothiazole.

aReactions were carried out under N2 atm. Conv, regioselectivity, and diastereoselectivity were determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%). Yields are for purified products (±5%). Enantiomeric ratios were determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run at least in triplicate. See the Supporting Information for details.

We then turned our attention to another key fragment, namely, α-alkenyl boronate 11 (Scheme 9a). We first prepared allenyl carbamate 10 from propargyl carbamate 9 (obtained in one step from the commercially available propargyl amine).25 Organoboronate intermediate 11 was accessed directly through regioselective proto-boryl addition to the allene site of 10 catalyzed by the Cu–B(pin) complex derived from imid-1; use of i-PrOH (vs MeOH, as reported originally)26 allowed us to obtain the desired product with higher α selectivity (92:8 vs 96:4 α:β selectivity and 61% vs 76% yield of 11 with MeOH and i-PrOH, respectively). We were thus able to secure 1.5 g of 11 (76% yield, 96:4 α:β selectivity). With substantial amounts of Z-allylic boronate 4a available, we carried out the critical catalytic addition to aldehyde 1a under the same conditions as described above (Scheme 5): 1.76 g of the aldehyde was transformed to 1.30 g 3a in 86% yield, >98:2 α:γ ratio, >98:2 Z:E ratio, and 94:6 er (Scheme 9b). As was noted, reactions with 1.5 equiv 1a was optimal (53% yield, 80:20 α:γ with 1.0 equiv 1a, under otherwise identical conditions), and the unreacted aldehyde was recovered as part of product purification in high yield (i.e., 0.57 g, 97% recovery).

Next, two catalytic cross-coupling reactions were performed. The first was to accomplish the chemoselective merger of allyl–B(pin) at the C–Br site, catalyzed by 2.5 mol % of a catalyst derived from Pd(dppf)Cl2, according to a recent procedure by Aggarwal,27 to generate 12 in 72% yield. Next, we needed to establish whether the alkenyl chloride moiety would undergo efficient catalytic cross-coupling. We expected that conversion of 12 to 13 would be particularly challenging process for two reasons. Firstly, the diene moiety is sensitive and prone to isomerization/decomposition; accordingly, the reaction had to be performed in the dark and at 55 °C. Secondly, strongly basic conditions led to cleavage of the carbamate moiety, leading us to use the milder K3PO4 along with minimal amount of H2O instead. After optimization studies we were able to establish that alkenyl–B(pin) 11 and Z-alkenyl–chloride 12 react readily in the presence of 10 mol % ruphos–Pd-G3 and 10 mol % ruphos (both are commercially available), as outlined by Buchwald and co-workers,28 affording 13 in 71% yield (>98:2 Z:E). Various other cross-partners, including alkylzinc halide compounds (Negishi-type coupling) can be used efficiently with a Z-di- or trisubstituted alkenyl chloride.29 Synthesis of the 1,4-diene side chain was then carried out. Catalytic stereo-retentive cross-metathesis of 13 and commercially available 14 with Ru catechothiolate complex Ru-130 (9.0 mol %) delivered primary alcohol 15 in 77% yield (>98:2 Z/Z:Z/E). The ensuing conversion to the primary bromide and elimination of HBr was catalyzed by a phosphine–Pd complex, as outlined by Fu,31 affording mycothiazole in 56% overall yield (Scheme 9b). The above route allowed us to obtain 0.25 g of the natural product. The above route contains a total of 12 steps and a longest linear sequence of nine transformations, seven of which are catalytic. The antitumor natural product was isolated in 14.5% overall yield.

3. CONCLUSIONS

We introduce a catalytic strategy that may be used to access a wide variety of Z-homoallylic alcohols efficiently and with high levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity. The effectiveness of the approach is largely due to the involvement of three C–C bond forming transformations: catalytic stereoretentive cross-metathesis to generate Z-chloro-substituted allylic boronates, aminophenol-borylcatalyzed addition of the aforementioned organoboron compound to deliver a Z-chloroalkenyl-substituted homoallylic alcohol, and catalytic stereoretentive cross-coupling that can afford enantiomerically enriched Z-homoallylic alcohols bearing a C-based substituent. Furthermore, we show that the same approach may be used to generate a wide range of homoallylic alcohols that contain a Z-F3C-substituted alkene efficiently and with high regio- and stereochemical control. A strategically significant point is that catalytic cross-metathesis and catalytic allyl addition are utilized in a convergent manner: the organoboronate is prepared first and then used to generate a chloroalkene-substituted homoallylic alcohol enantioselectively. This is in contrast to performing cross-metathesis on a homoallylic alcohol or a related derivative. The need for a priori masking of the secondary alcohol was thus obviated. Since late transition metal complexes typically used in cross-coupling are not sensitive to hydroxy groups, the three-stage all-catalytic sequence may be performed without resorting to protection/deprotection strategies.

There are other factors that render the present advance noteworthy. Other than the synthetically useful yields, the transformations are scalable, the γ-addition isomer, if formed, can be easily removed in most cases, and diastereo- (up to 97:3 dr) or enantioselectivities are typically high (up to 98:2 er). The requisite aminophenol ligands can be prepared easily and are indefinitely stable, and a commercially available Mo complex can be used to synthesize the requisite allylic boronates. Perhaps the most convincing indicator of the utility of the approach is the 12-step and protecting group-free total synthesis of mycothiazole, a sequence that is considerably shorter than the one reported previously.4e

Development of additional multi-catalytic strategies that allow access to otherwise difficult-to-prepare and valuable fragments for use in chemical synthesis are in progress.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM-57212), the CNRS (Make Our Planet Great Again program, PRACTACAL project), and the Frontiers in Chemistry Research Fondation (University of Strasbourg).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at DOI:https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.9b11178 Experimental details for all reactions and analytic details for all products (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).For reviews on catalytic enantioselective addition of allylic groups to aldehydes, see:; (a) Denmark SE; Fu J Catalytic enantioselective addition of allylic organometallic reagents to aldehydes and ketones. Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2763–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yus M; González-Gómez JC; Foubelo F Catalytic enantioselective allylation of carbonyl compounds and imines. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 7774–7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).For structure determination and bioactivity of macrolactins, see:; (a) Gustafson K; Roman M; Fenical W The macrolactins, a novel class of antiviral and cytotoxic macrolides from a deep-sea marine bacterium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 7519–7524. [Google Scholar]; For a reported total syntheses, see:; (b) Smith III AB; Ott GR Total synthesis of (–)-macrolactin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 13095–13096. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim Y; Singer RA; Carreira EM Total synthesis of macrolactin A with versatile catalytic, enantioselective dienolate aldol addition reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1998, 37, 1261–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith III AB; Ott GR Total syntheses of (–)-macrolactin A, (+)-macrolactin E, and (–)-macrolactinic acid: an exercise in Stille cross-coupling chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 3935–3948. [Google Scholar]; (e) Marino JP; McClure MS; Holub DP; Comasseto JV; Tucci FC Stereocontrolled synthesis of (–)-macrolactin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 1664–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).For structure determination and bioactivity of disorazole C1, see:; (a) Wong FT; Jin X; Mathews II; Cane DE; Khosla C Structure and mechanism of the trans-acting acyltransferase from the disorazole synthase. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 6539–6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hopkins CD; Wipf P Isolation, biology, and chemistry of disorazoles: new anti-cancer macrodiolides. Nat. Prod. Rep 2009, 26, 585–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For reported total syntheses, see:; (c) Wipf P; Graham TH Total synthesis of (–)-disorazole C1. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15346–15347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Speed AWH; Mann TJ; O’Brien RV; Schrock RR; Hoveyda AH Catalytic Z-selective cross-metathesis in complex molecule synthesis: a convergent stereoselective route to disorazole C1. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16136–16139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).For structure determination and bioactivity of mycothiazole, see:; (a) Crews P; Kakou Y; Quiñoà E Mycothiazole, a polyketide heterocycle from a marine sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 110, 4365–4368. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sonnenschein RN; Johnson TA; Tenney K; Valeriote FA; Crews P A reassignment of (–)-mycothiazole and the isolation of a related diol. J. Nat. Prod 2006, 69, 145–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ahlmark M; Din Belle D; Kauppala M; Luiro A; Pajunen T; Pystynen J; Tianen E; Vaismaa M; Messinger J Catechol O-methyltransferase activity inhibiting compounds. US Patent Application US 2015/0218124 A1. [Google Scholar]; (d) Morgan JB; Mahdi F; Liu Y; Coothankandaswamy V; Jekabsons MB; Johnson TA; Sashidhara KV; Crews P; Nagle DG; Zhou Y-D The marine sponge metabolite mycothiazole: A novel prototype mitochondrial complex I inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2010, 18, 5988–5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For the only reported total synthesis, see:; (e) Wang L; Hale KJ Total synthesis of the potent HIF-1 inhibitory antitumor natural product, (8R)-mycothiazole, via Baldwin–Lee CsF/CuI sp3-sp2-Stille cross-coupling. Confirmation of the Crews assignment. Org. Lett 2015, 17, 4200–4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For more recent findings regarding the bioactivity of mycothiazole, see:; (f) Meyer KJ; Singh AJ; Cameron A; Tan AS; Leahy DC; O’Sullivan D; Joshi P; La Flamme AC; Northcote PT; Berridge MV; Miller JH Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 900–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For studies regarding the synthesis of mycothiazole, some of which correspond to the incorrect and initially assigned structure of the natural product, see:; (g) Sugiyama H; Yokokawa F; Shioiri T Asymmetric total synthesis of (–)-mycothiazole. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 2149–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Sugiyama H; Yokokawa F; Shioiri T Total synthesis of mycothiazole, a polyketide heterocycle from marine sponges. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 6579–6593. [Google Scholar]; (i) Le Flohic A; Meyer C; Cossy J Total synthesis of (±)-mycothiazole and formal enantioselective approach. Org. Lett 2005, 7, 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Le Flohic A; Meyer C; Cossy J Reactivity of unsaturated sultones synthesized from unsaturated alcohols by ring-closing metathesis. Application to the racemic synthesis of the originally proposed structure of mycothiazole. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9017–9037. [Google Scholar]; (k) Rega M; Candal P; Jiménez C; Rodríguez J Mycothiazole: synthesis of the C8–C18 subunit and further evidence of the (Z)-Δ14 double bond configuration. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2007, 934–942. [Google Scholar]; (l) Batt F; Fache F Towards the synthesis of the 4,19-diol derivative of (–)-mycothiazole: synthesis of a potential key intermediate. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2011, 6039–6055. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Tsubuki M; Takahashi K; Sakata K; Honda T Studies toward the synthesis of furanocembrane bipinnatin J: synthesis of 2,3,5-trisubstituted furfuryl ether intermediate. Heterocycles 2005, 65, 531–540. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang B; Bray CD; Pattenden G Total synthesis of (+)-intricarene using a biogenetically patterned pathway from (–)-bipinnatin J, involving a novel transannular [5+2] (1,3-dipolar) cycloaddition. Org. Biomol. Chem 2009, 7, 4448–4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).For selected cases, see:; (a) Brown HC; Jadhav PK Asymmetric carbon–carbon bond formation via B-allyldiisopinocamphenylborane. Simple synthesis of secondary homoallylic alcohols with excellent enantiomeric purities. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 2092–2093. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roush WR; Walts AE; Hoong LK Diastereo- and enantioselective aldehyde addition reactions of 2-allyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane-4,5-dicarboxylic esters, a useful class of tartrate ester modified allylboronates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 8186–8190. [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ; Mu C-M; Kim SS A practical and efficient method for enantioselective allylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 5495–5496. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kubota K; Leighton JL A highly practical and enantioselective reagent for the allylation of aldehydes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2003, 42, 946–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Burgos CH; Canales E; Matos K; Soderquist JA Asymmetric allyl- and crotylboration with the robust, versatile, and recyclable 10-TMS-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 8044–8049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Kim IS; Ngai M-Y; Krische MJ Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed allylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level via transfer hydrogenative coupling of allyl acetate: departure from chirally modified allyl metal reagents in carbonyl addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 14891–14899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rauniyar V; Zhai H; Hall DG Catalytic enantioselective allyl- and crotylboration of aldehydes using chiral diol•SnCl4 complexes. Optimization, substrate scope and mechanistic investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 8481–8490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rauniyar V; Hall DG Rationally improved chiral Brønsted acid for catalytic enantioselective allylboration of aldehydes with an expanded reagent scope. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 4236–4241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jain P; Antilla JC Chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed allylboration of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 11884–11886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hassan A; Townsend IA; Krische MJ Catalytic enantioselective Grignard Nozaki–Hiyama methallylation from the alcohol oxidation level: chloride compensates for π-complex instability. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 10028–10030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gao X; Zhang YJ; Krische MJ Iridium-catalyzed anti-diastereo- and enantioselective carbonyl (α-trifluoromethyl)allylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 4173–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zbieg JR; Yamaguchi E; McIntruff EL; Krische MJ Enantioselective C-H crotylation of primary alcohols via hydrohydroxyalkylation of butadiene. Science 2012, 336, 324–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Brito GA; Della-Felice F; Luo G; Burns AS; Pilli RA; Rychnovsky SD; Krische MJ Catalytic enantioselective allylations of acetylenic aldehydes via 2-propanol-mediated reductive coupling. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 4144–4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Gao S; Chen M Enantioselective syn- and anti-alkoxyallylation of aldehydes via Brønsted acid catalysis. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 6174–6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Stork G; Zhao K A stereoselective synthesis of (Z)-1-iodo-1-alkenes. Tetrahedron Lett 1989, 30, 2173–2174. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhu B; Panek JS Total synthesis of epothilone A. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 2575–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Chen M; Roush WR Highly (E)-selective BF3•Et2O-promoted allylboration of chiral nonracemic α-substituted allylboronates and analysis of the origin of stereocontrol. Org. Lett 2010, 12, 2706–2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For earlier associated studies, see:; (b) Hoffmann RW; Landmann B Transfer of chirality in the addition of chiral α-chloroallylboronate esters to aldehydes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1984, 23, 437–438. [Google Scholar]; (c) Carosi L; Lachance H; Hall DG Additions of functionalized a-substituted allylboronates to aldehydes under the novel Lewis and Brønsted acid catalyzed manifolds. Tetrahedron Lett 2005, 46, 8981–8985. [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Lee C-LK; Lee C-HA; Tan K-T; Loh TP An unusual approach to the synthesis of enantiomerically cis linear homoallylic alcohols based on the steric interaction mechanism of camphor scaffold. Org. Lett 2004, 6, 1281–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Incerti-Pradillos CA; Kabeshov MA; Malkov AV Highly stereoselective synthesis of Z-homoallylic alcohols by kinetic resolution of racemic secondary allyl boronates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 5338–5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).This sequence could be shortened by one step since direct conversion of the alkene to a Z-allylic bromide or chloride is now feasible. See:; Koh MJ; Nguyen TT; Zhang H; Schrock RR; Hoveyda AH Direct synthesis of Z-alkenyl halides through catalytic cross-metathesis. Nature 2016, 531, 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mu Y; Nguyen TT; van der Mei FW; Schrock RR; Hoveyda AH Traceless protection for more broadly applicable olefin metathesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 5365–5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Silverio DL; Torker S; Pilyugina T; Vieira EM; Snapper ML; Haeffner F; Hoveyda AH Simple organic molecules as catalysts for enantioselective synthesis of amines and alcohols. Nature 2013, 494, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Wu H; Haeffner F; Hoveyda AH An efficient, practical, and enantioselective method for synthesis of homoallenylamides catalyzed by an aminoalcohol-derived, boron-based catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 3780–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) van der Mei FW; Miyamoto H; Silverio DL; Hoveyda AH Lewis acid catalyzed borotropic shifts in the design of diastereo- and enantioselective γ-additions of allylboron moieties to aldimines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 4701–4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Morrison RJ; Hoveyda AH γ-, Diastereo-, and enantioselective addition of MEMO-substituted allylboron compounds to aldimines catalyzed by organoboron-ammonium complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 11654–11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Lee K; Silverio DL; Torker S; Robbins DW; Haeffner F; van der Mei FW; Hoveyda AH Catalytic enantioselective addition of organoboron reagents to fluoroketones controlled by electrostatic interactions. Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Robbins DW; Lee K; Silverio DL; Volkov A; Torker S; Hoveyda AH Practical and broadly applicable catalytic enantioselective additions of allyl-B(pin) compounds to ketones and α-ketoesters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 9610–9614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) van der Mei FW; Qin C; Morrison RJ; Hoveyda AH Practical, broadly applicable, α-selective, Z-selective, diastereoselective, and enantioselective addition of allylboron compounds to mono-, di-, tri-, and polyfluoroalkyl ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9053–9065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mszar NW; Mikus MS; Torker S; Haeffner F; Hoveyda AH Electronically activated organoboron catalysts for enantioselective propargyl addition to trifluoromethyl ketones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 8736–8741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fager DC; Lee K; Hoveyda AH Catalytic enantioselective addition of an allyl group to ketones containing a tri-, a di-, or a monohalomethyl moiety. Stereochemical control based on distinctive electronic and steric attributes of C–Cl, C–Br, and C–F bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 16125–16138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Savage SA; Jones GS; Kolotuchin S; Ramrattan SA; Vu T; Waltermire RE Preparation of saxagliptin, a novel DPP-IV inhibitor. Org. Proc. Res. Dev 2009, 13, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Schmitt DC; Dechert-Schmitt A-MR; Krische MJ Iridium-catalyzed allylation of chiral β-stereogenic alcohols: bypassing discrete formation of epimerizable aldehydes. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 6302–6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Similarly, cyclohexyl-substituted homoallylic alcohol 5p was formed in 96:4 α:γ selectivity in the absence of MeOH (vs 85:15). However, this did not reflect a significant increase in the yield of the pure α-addition compound. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Nguyen TT; Koh MJ; Mann TJ; Schrock RR; Hoveyda AH Synthesis of E- and Z-trisubstituted alkenes by catalytic cross-metathesis. Nature 2017, 552, 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Kojima R; Akiyama S; Ito H A copper(I)-catalyzed enantioselective γ-boryl substitution of trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes: synthesis of enantioenriched γ,γ-difluoroallylboronates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 7196–7199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao P; Yuan C; Zhao Y; Shi Z Copper-catalyzed asymmetric defluoroborylation of 1-(trifluoromethyl)alkenes. Chem 2018, 4, 2201–2211. [Google Scholar]; (c) Paioti PHS; del Pozo J; Mikus MS; Lee J; Koh MJ; Romiti F; Torker S; Hoveyda AH Catalytic enantioselective boryl and silyl substitution with trifluoromethyl alkenes: scope, utility, and mechanistic nuances of Cu–F β-elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).See the Supporting Information for details regarding the ligand screening studies.

- (23).Koh MJ; Nguyen TT; Lam JK; Torker S; Hyvl J; Schrock RR; Hoveyda AH Molybdenum chloride catalysts for Z-selective olefin metathesis reactions. Nature 2017, 542, 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).It is also possible to prepare 1a in two steps through the use of a one-step oxidation procedure but in lower yield (79% vs 88%). See:; Yu W; Mei Y; Kang Y; Hua Z; Jin Z Improved procedure for the oxidative cleavage of olefins by OsO4–NaIO4. Org. Lett 2004, 6, 3217–3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Crabbé P; Fillion H; André D; Luche J-L Efficient homologation of acetylenes to allenes. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1979, 859–860. [Google Scholar]; (b) Searles S; Li Y; Nassim B; Lopes M-TR; Tran PT; Crabbé P Observation on the synthesis of allenes by homologation of alk-1-ynes. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1, 1984, 747–751. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuang J; Ma S An efficient synthesis of terminal allenes from terminal 1-alkynes. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 1763–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jang H; Zhugralin AR; Lee Y; Hoveyda AH Highly selective methods for synthesis of (α-) vinylboronates through efficient NHC–Cu-catalyzed hydroboration of terminal alkynes. Utility in chemical synthesis and mechanistic basis for selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7859–7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhurakovskyi O; Türkmen YE; Löffler LE; Moorthie VA; Chen CC; Shaw MA; Crimmin MR; Ferrara M; Ahmad M; Ostovar M; Matlock JV; Aggarwal VK Enantioselective synthesis of the cyclopiazonic acid family using sulfur ylides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 1346–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Bruno NC; Niljiasnskul N; Buchwald SL N-Substituted 2-aminobiphenylpalladium methanesulfonate precatalysts and their use in C–C and C–N cross-couplings. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 4161–4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bruno NC; Tudge MT; Buchwald SL Design and preparation of new palladium precatalysts for C–C and C–N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 916–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).See the Supporting Information for details of additional catalytic cross-coupling reactions with the alkenyl halide moiety.

- (30).(a) Koh MJ; Khan RKM; Torker S; Yu M; Mikus MS; Hoveyda AH High-value alcohols and higher-oxidation-state compounds by catalytic Z-selective cross-metathesis. Nature 2015, 517, 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu C; Shen X; Hoveyda AH In situ methylene capping: a general strategy for efficient stereoretentive catalytic olefin metathesis. The concept, methodological implications, and applications to synthesis of biologically active compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 10919–10928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bissember AC; Levina A; Fu GC A mild, palladium-catalyzed method for the dehydrohalogenation of alkyl bromides: synthetic and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14232–143237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.