Abstract

Background/aim

While C-reactive protein (CRP) is a well-studied marker for predicting treatment response and mortality in sepsis, it was aimed to assess the efficacy of the neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictor of mortality and treatment response in sepsis patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Materials and methods

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, sepsis patients were divided according to the presence of septic shock on the 1st day of ICU stay, and then subgrouped according to mortality. Patient demographics, acute physiologic and chronic health evaluation II and sequential organ failure assessment scores, NLR and CRP (on the 1st, 3rd, and last day in the ICU), microbiology data, antibiotic responses, ICU data, and mortality were recorded. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the area under curve (AUC) were calculated for the inflammatory markers and ICU severity scores for mortality.

Results

Of the 591 (65% male) enrolled patients, 111 (18.8%) were nonsurvivors with shock, 117 (19.8%) were survivors with shock, 330 (55.8%) were survivors without shock, and 33 (5.6%) were nonsurvivors without shock. On the 1st day of ICU stay, the NLR and CRP were similar in all of the groups. On the 3rd day of antibiotic response, the NLR was increased (11.8) in the nonresponsive patients when compared with the partially responsive (11.0) and responsive (8.5) patients. If the NLR was ≥15 on the 3rd day, the mortality odds ratio was 6.96 (CI: 1.4–34.1, P < 0.017). The NLR and CRP on the 1st, 3rd, and last day of ICU stay (0.52, 0.58, 0.78 and 0.56, 0.70, 0.78, respectively) showed a similar increasing trend for mortality.

Conclusion

The NLR can predict mortality and antibiotic responsiveness in ICU patients with sepsis and septic shock. If the NLR is >15 on the 3rd day of postantibiotic initiation, the risk of mortality is high and treatment should be reviewed carefully.

Keywords: Septic shock, intensive care unit, respiratory failure, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

1. Introduction

Early recognition of sepsis can lead to early treatment and a potential reduction in septic shock development [1]. Despite treatment improvements with the global sepsis campaign, patients with septic shock have a high mortality rate in the intensive care unit (ICU) [2–4].

Acute physiological and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE) and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores are well known mortality predictors in ICU patients with sepsis [5,6]. C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin are the most studied inflammatory markers of bacterial sepsis, particularly for making decisions regarding antibiotic treatment in the ICU [7–11]. SOFA and APACHE II scores are calculated to assess disease severity, treatment response, and risk of mortality in the ICU, and these are not easy to calculate at the bed side in daily practice.

There are some inflammatory markers, such as the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), that are used to assess treatment response in sepsis patients for their simplicity [12,13].

Procalcitonin and CRP are the most used biomarkers to discriminate bacterial sepsis from other inflammatory diseases [14]. However, CRP can increase in both infectious and noninfectious diseases and, even though procalcitonin has a well-defined role as a sepsis biomarker, it has inconsistent and variable results for the diagnosis of infectious sepsis, not to mention it is expensive to assess [15,16]. Recently, studies have been undertaken on inflammatory markers obtained from complete blood counts (CBCs) with simple calculations for early recognition of infection and assessing treatment response [17–22]. Inflammatory markers obtained by CBCs, such as the NLR, PLR, platelet to mean platelet volume (MPV), have been assessed in different disease groups for their association with hospital mortality [12,13,22,23]. The NLR has been recommended as an infection biomarker since 2001 [24] and there have since been studies evaluating NLR alone, or as part of a multiple biomarker model, for the diagnosis of adult patients with suspected community onset sepsis [25,26]. High NLR combined with lymphocytopenia may be a better predictor of bacteremia than other routinely used parameters in the emergency department, such as CRP and the leucocyte count [26]. In addition, higher NLR and lymphocytopenia values were correlated with disease severity [24].

It was aimed herein to determine whether NLR obtained from CBCs and with simple calculation can be used to predict mortality and treatment response in patients with sepsis and septic shock in the ICU.

2. Materials and methods

This study was performed in a level 3 ICU, in a chest diseases and thoracic surgery training and research hospital after approval from the hospital’s local ethics committee, as prescribed by the Helsinki Declaration. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no informed consent was obtained from the patients.

The ICU was operated by the same intensivist/pulmonologist team over a 7-day period and each ICU team followed the same ICU procedures, as defined by written protocols (such as sepsis, mechanical ventilation, weaning, etc.).

2.1. Patients

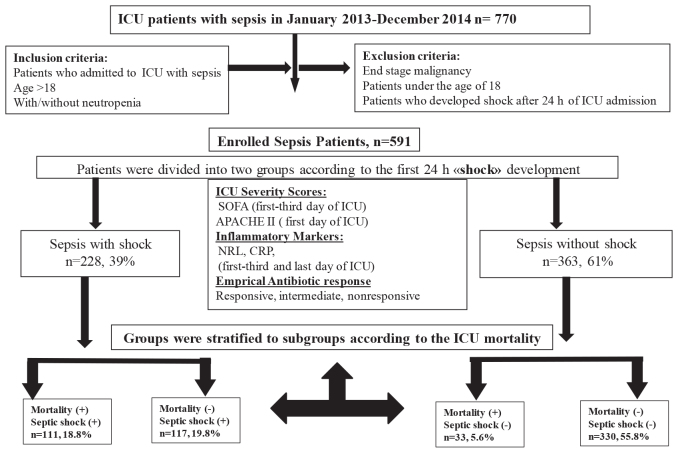

This was designed as a retrospective, observational, and cross-sectional study, from January 2013 to April 2015. Patient data, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, the presence of septic shock on admission to the ICU, ICU mortality, and assignment according to the presence of septic shock, are summarized in a flow chart in Figure 1. Patients admitted to the ICU had pulmonary sepsis and septic shock that was either community acquired pneumonia or acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patients were stratified according to ICU mortality; categorized as early death (day 1 to 4), or late death (day 5 or after) [27].

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

Table 1.

A comparison of sepsis patient demographics, ICU data, and inflammatory markers relative to the presence of septic shock.

| Septic shock on admission to the intensive care unit | |||||

| Absent, n = 392 | Present, n = 199 | ||||

| Variable | n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | P-value |

| Age | 392 | 65 (56–75) | 199 | 71 (62–79) | <0.001 |

| Sex, Male n (%) | 363 | 248 (63) | 228 | 133 (67) | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 361 | 23 (21–28) | 183 | 23 (20–28) | 0.36 |

| Comorbid diseases | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 | 23% | 51 | 26% | 0.51 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 196 | 50% | 95 | 48% | 0.58 |

| Hypertension | 158 | 40% | 84 | 42% | 0.67 |

| Coronary arterial disease | 49 | 13% | 31 | 16% | 0.30 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 38 | 10% | 28 | 14% | 0.11 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 27 | 7% | 20 | 10% | 0.17 |

| Lung cancer | 37 | 9% | 29 | 15% | 0.06 |

| Extra-pulmonary cancer | 21 | 5% | 14 | 7% | 0.41 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 | 3% | 9 | 5% | 0.36 |

| Obesity hypoventilation syndrome | 24 | 6% | 7 | 4% | 0.17 |

| ICU data | |||||

| APACHE II score on admission | 388 | 18 (15–23) | 197 | 29 (23–33) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score on admission | 361 | 3 (2–4) | 228 | 7 (5–9) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score on the 3rd day of ICU stay | 325 | 2 (2–3) | 202 | 5 (3–8) | 0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, | 94 | 26% | 42 | 18% | 0.001 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation, | 257 | 71% | 130 | 57% | 0.001 |

| Noninvasive ventilation failure, | 32 | 9% | 54 | 24% | 0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay, days | 392 | 6 (4–9) | 199 | 7 (4–12) | 0.14 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation duration, days | 120 | 3 (2–6) | 160 | 4 (2–8) | 0.02 |

| Antibiotic responsiveness | |||||

| Responsive | 211 | 58% | 69 | 30% | 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 130 | 36% | 123 | 54% | |

| Nonresponsive | 22 | 6% | 36 | 16% | |

| CRP, mg/L | |||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 292 | 90 (33–160) | 174 | 98 (44–182) | 0.13 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 263 | 73 (2135) | 167 | 125 (62–182) | 0.001 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 304 | 43 (20–198) | 182 | 82 (42–155) | 0.001 |

| NLR | |||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 363 | 10.50 (5.76–19.56) | 228 | 13.48 (7.54–23.48) | 0.001 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 326 | 8.64 (5.23–15.33) | 199 | 10.97 (6.73–18.41) | 0.002 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 356 | 5.93 (3.93–10.25) | 220 | 8.19 (4.47–16.39) | 0.001 |

IQR: interquartile range. APACHE II: acute physiologic and chronic health evaluation II. SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment, NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, CRP: C-reactive protein.

Study endpoint: ICU mortality and discharge from ICU in patients with septic shock and sepsis alone.

2.2. Definitions

2.2.1. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis-septic shock

Definitions used in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign; an International Guideline for the Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock (2012), were deemed valid for the study period. SIRS is defined by the following criteria: a pulse rate of 90/min and above or 2 standard deviations above the normal value for age; a respiratory rate of 20 and above or a partial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) of 32 mmHg and below; alteration of consciousness; a white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 12,000 µL–1 or below 4000 µL–1; a temperature less than 36 °C or greater than 38.3 °C; plasma glucose levels of >40 mg/dL; a plasma CRP level 2 standard deviations above the normal value; and an inspired oxygen fraction of the partial arterial oxygen concentration (PaO2/FiO2) of <300.

Patients with 2 or more SIRS criteria and with a suspected or proven infection were defined as having sepsis [28]. Sepsis induced hypotension was defined as a systolic arterial pressure of £90 mmHg, a mean arterial pressure of £65 mmHg, or a decrease in systolic arterial pressure of >40 mmHg in patients with no other health issues causing hypotension. As a vasopressor, noradrenalin was initiated at 0.01–3 µg/kg/min intravenous infusion, and if necessary, dopamine was added at 5–20 µg/kg/min.

2.3. Recording data

Patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2]), arterial blood gas (ABG) values (Rapidlab, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), and the presence of comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [29], hypertension [30], diabetes mellitus [31], lung cancer, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, Alzheimer’s disease, chronic renal failure, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome, were recorded on admission and discharge from the ICU. CBC values, including the WBC, hematocrit (Htc), platelet, MPV, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count on the 1st, 3rd, and last day of ICU stay, calculated NLR, and CRP on the 1st, 3rd, and last day of ICU stay, were also recorded. In addition, biochemical values on ICU admission and discharge were recorded. The APACHE II score was recorded on the day of ICU admission, and the SOFA score was recorded on the day of admission and 3rd day in the ICU. The use of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) was noted. Culture results, duration of ICU stay in days, and ICU mortality were also recorded.

2.4. Calculations

The NLR was calculated as the neutrophil absolute value over the lymphocyte absolute value. According to the literature, the patients were grouped according to whether their NLR values were above or below 10 and 15 on the 1st, 3rd, and last day of ICU stay [32].

2.5. Mechanical ventilation application

In the ICU, all patients not absolutely contraindicated were initially given NIMV. Contraindications included: 1) heart and/or pulmonary arrest, 2) unconsciousness (excluding hypercarbia), 3) nonrespiratory organ failure, severe encephalopathy, shock, heart pathology leading to unstable hemodynamics, or severe upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, 4) lack of airway protection, 5) inability to remove secretions, 6) risk of aspiration, 7) upper airway obstruction, and 8) facial surgery, trauma, deformity, or burning [33]. NIMV failure was defined as the continuation of acidosis in ABG after NIMV application, aggravation of respiratory distress, mask and NIMV incompatibility, hemodynamic instability, cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, and a loss of consciousness [34]. Patients with NIMV failure, or in cases where NIMV application was contraindicated, received IMV via endotracheal intubation. IMV was defined as volume- or pressure-controlled, assisted control ventilation, performed based on the 6–8 mL/kg tidal volume for ideal body weight, or a plateau pressure equal to or less than 30 cmH2O. For COPD patients, FiO2 was titrated to 88%–92% oxygen saturation, and for cardiac ischemic patients, it was titrated to 95% and above. Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) was titrated, taking into account hemodynamic parameters in patients with COPD, to 5–6 cmH2O, together with the mean arterial pressure (65 mmHg and above) and plateau pressure (30 cmH2O and below). Patients undergoing IMV were followed up with a fentanyl/midazolam/propofol infusion as sedation and pain palliation was assessed using the Richmond agitation and sedation scale [35]. Sedation was interrupted daily and the patients’ clinical condition was assessed.

2.6. Weaning protocol

For those patients with improved clinical and laboratory values, mechanical ventilation support was reduced and a spontaneous breathing trial was performed. The spontaneous breathing trial was performed once per day using a 30-min T-tube test or pressure support ventilation with a PEEP of 5 cmH20 and pressure support of 8 cmH2O [36].

2.7. Microbiology

Deep tracheal aspirations were cultured for intubated patients. Sputum cultures were obtained for nonintubated patients. In patients with a temperature of <36 °C or >38 °C, blood cultures were taken for aerobes and anaerobes. In the study period, blood cultures were not taken from patients with normothermia, as per the hospital infectious committee protocol for ICU sepsis.

2.8. Antibiotic response

· Responsive: A sensitive culture response or significant improvement in the clinical and laboratory values to treatment showed no culture or a nonreproductive culture response.

· Partially responsive: Treatment with a moderately sensitive culture response or partial improvement in the clinical and laboratory values, in that patients had a noncultured or nonreproductive culture response.

· Nonresponsive: Treatment with a resistant culture response or significant deterioration in the clinical and laboratory values, in that patients had a noncultured or nonreproductive culture response.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Study data were analyzed using the SPSS v.20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) portable package program. The continuous numerical values of the binary groups were compared using Student’s t-test for uniform distribution and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Nonuniform distribution was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test and median quarter-to-quarter ratio. Dichotomous values were summarized using the chi-square test. Comparisons of 2 or more groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test for unevenly distributed data. Assessment of mortality markers was shown using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC). Multilogistic regression analysis was performed using known mortality markers affecting mortality in the ICU (APACHE II and SOFA scores), inflammatory markers (CRP, NLR), demographic characteristics affecting mortality, such as age, male sex, BMI, and comorbidities found to be significant in binary variants (heart failure, IMV, antibiotic sensitivity response, shock upon ICU admission, and length of ICU stay). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Distribution of the study patients into the defined groups is summarized in Figure 1. During the study period, 591 of 770 patients were included in the study (381 [65%] were male). The median age was 67 (19–99) years old. Septic shock within the first 24 h was seen in 39%, and ICU mortality occurred in 144 (24.4%) of the 591 patients.

The demographic characteristics of the patients relative to the presence of septic shock are shown in Table 1. Patients with septic shock were found to have a significantly higher APACHE II score on ICU admission; they were older and had more cardiac arrhythmias than those without septic shock (Table 1). The inflammatory markers and antibiotic responses are summarized in Table 1.

Patient NLR and CRP values relative to antibiotic responsiveness over the duration of the ICU stay are summarized in Table 2. The NLR and CRP values on the 3rd day in the ICU were significantly higher in patients with partial resistance and resistance to antibiotics, compared to the antibiotic-sensitive group. Following treatment, CRP values were similar between the groups on the last day of ICU stay, but the NLR was statistically lower in the antibiotic-sensitive group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the NLR and CRP values in response to antibiotic therapy in septic shock patients in the ICU.

| Responsive to antibiotherapy | Partially responsive to antibiotherapy | Nonresponsive to antibiotherapy | |||||

| Inflammatory markers | n = 280 | Values, median (IQR) | n = 253 | Values, median (IQR) | n = 58 | values, median (IQR) | P-value |

| CRP, mg/L | |||||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 213 | 99 (38–175) | 204 | 90 (36–157) | 49 | 95 (43–182) | 0.86 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 201 | 79 (27–140) | 190 | 105 (42–167) | 39 | 115 (84–180) | 0.005 |

| Last day of ICU stayv | 245 | 51 (22–108) | 199 | 62 (24–139) | 42 | 74 (20–121) | 0.35 |

| NLR | |||||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 280 | 11.2 (6.6–17.9) | 253 | 12.7 (6.2–25.1) | 58 | 10.0 (5.4–20.7) | 0.17 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 256 | 8.5 (5.5–14.1) | 220 | 11.0 (6.2–18.0) | 49 | 11.8 (6.5–21.7) | 0.008 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 273 | 5.7 (3.8–9.0) | 247 | 9.7 (4.5–15.9) | 56 | 8.4 (4.2–15.7) | 0.001 |

IQR: interquartile ratio, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test.

Table 3 summarizes the ICU data and inflammatory markers of those patients with pulmonary sepsis relative to mortality in the ICU within 5 days. Age and sex were similar in both the survivors and nonsurvivors within 5 days. Apart from lung cancer and COPD, comorbid diseases were similar whether the patients died within 5 days or not. A significantly higher rate of nonresponsiveness to antibiotic treatment, IMV application, and the presence of septic shock were found in those patients who died within 5 days. Among the inflammatory markers, only the NLR was significantly higher on the 1st day of ICU stay in those patients who died within 5 days.

Table 3.

ICU data and inflammatory markers for patients with pulmonary sepsis relative to mortality in the ICU within 5 days.

| Survivors in 5 days | Nonsurvivors in 5 days | P-value | |||

| n | Values | n | Values | ||

| Age | 535 | 67 (57–77) | 56 | 71 (57–80) | 0.19 |

| Sex, Male | 347 | 65% | 34 | 61% | 0.54 |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 495 | 23 (21–28) | 22 | 22 (19–25) | 0.017 |

| Comorbid diseases | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 130 | 24% | 12 | 21% | 0.63 |

| Hypertension | 220 | 41% | 22 | 39% | 0.78 |

| COPD | 275 | 52% | 16 | 29% | 0.001 |

| Coronary heart diseases | 75 | 14% | 5 | 9% | 0.29 |

| Lung cancer | 50 | 9% | 16 | 29% | 0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 135 | 25% | 15 | 27% | 0.80 |

| APACHE II score, 1st day of ICU stay | 535 | 20 (16–27) | 55 | 30 (25–38) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score, 1st day of ICU stay | 535 | 4 (2–6) | 55 | 8 (5–10) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score, 3rd day of ICU stay | 503 | 3 (2–5) | 24 | 9 (6–10) | 0.001 |

| Septic shock | 184 | 34% | 44 | 79% | 0.001 |

| Culture study | 363 | 68% | 28 | 50% | 0.007 |

| Positive culture | 91 | 25% | 12 | 43% | 0.039 |

| Antibiotic responsiveness | |||||

| Responsive | 273 | 51% | 7 | 13% | 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 221 | 41% | 32 | 57% | |

| Nonresponsive | 41 | 8% | 17 | 30% | |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||

| Noninvasive | 363 | 68% | 24 | 43% | 0.001 |

| Noninvasive failure | 76 | 14% | 10 | 18% | 0.46 |

| Invasive | 243 | 45% | 37 | 66% | 0.003 |

| CRP, mg/L | |||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 427 | 94 (34–165) | 39 | 91 (50–187) | 0.48 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 419 | 94 (36–153) | 11 | 180 (116–288) | 0.006 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 464 | 53 (21–111) | 22 | 193 (118–333) | 0.001 |

| NLR | |||||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 535 | 11.23 (6.19–-20.57) | 56 | 17.47 (9.28–27.12) | 0.016 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 501 | 9.33 (5.67–15.67) | 24 | 17.40 (8.42–33.80) | 0.004 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 529 | 6.24 (3.95–11.01) | 47 | 17.74 (9.58–31.97) | 0.001 |

Table 4 shows a comparison of the pulmonary sepsis patients; demographics, ICU data, and inflammatory markers of survivors versus nonsurvivors. Older age, a higher level of inflammatory markers, and a higher rate of nonresponsiveness to antibiotherapy were found in the nonsurvivors when compared with the survivors.

Table 4.

Comparison of pulmonary sepsis patients; demographics, ICU data and inflammatory markers of survivors versus nonsurvivors.

| Survivors | Nonsurvivors | P-values | |

| Number of patients | 447 | 144 | - |

| Male, % | 64.4 | 64.6 | 0.97 |

| Age, years | 66 (57–75) | 74 (60–81) | 0.001 |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 23 (21–28) | 23 (20–26) | 0.07 |

| Comorbid diseases, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 194 (43.5) | 48 (33.3) | 0.031 |

| Coronary artery diseases | 66 (14.8) | 14 (9.7) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 110 (24.6) | 32 (22.2) | 0.56 |

| Arrhythmias | 102 (22.8) | 48 (33.3) | 0.012 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases | 240 (53.8) | 51 (35.4) | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 416 (93.1) | 128 (88.9) | 0.11 |

| Obesity hypoventilation | 30 (6.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0.005 |

| Chronic renal failure | 12 (2.7) | 9 (6.7) | 0.044 |

| Lung cancer | 34 (7.6) | 32 (22.2) | 0.001 |

| ICU data | |||

| APACHE II on admission to the ICU | 19 (16–24) | 29 (24–35) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score on admission to the ICU | 3 (2–5) | 7 (5–10) | 0.001 |

| SOFA score on the 3rd day of ICU stay | 3 (2–4) | 6 (4–9) | 0.001 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 6 (4–9) | 5 (3–12) | 0.23 |

| Septic shock | 117 (26.2) | 111 (77.1) | 0.001 |

| Noninvasive ventilation, n (%) | 304 (68) | 83 (57.6) | 0.023 |

| Noninvasive ventilation days | 4 (2-7) | 2 (1-4) | 0.001 |

| Noninvasive failure to invasive ventilation, n (%) | 45 (10.1) | 41 (28.5) | 0.001 |

| Invasive ventilation, n (%) | 173 (38.7) | 107 (74.3) | 0.001 |

| Invasive ventilation days | 3 (2-6) | 7 (5-10) | 0.008 |

| Sepsis protocol | |||

| Empirical antibiotic, n (%) | |||

| · responsive | 262 (58.6) | 18 (12.5) | 0.001 |

| · intermediate | 164 (36.7) | 89 (61.8) | |

| · unresponsive | 21 (4.7) | 37 (25.7) | |

| Insulin infusion, n (%) | 22 (4.9) | 19 (13.2) | 0.001 |

| Steroid (60 mg/day), n (%) | 10 (2.2) | 12 (8.3) | 0.001 |

| Culture sample, N (%) | 294 (65.8) | 97 (67.4) | 0.73 |

| Positive culture sample, n (%) | 62 (21.1) | 41 (41.8) | 0.001 |

| Inflammatory markers | |||

| CRP, mg/L | |||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 89 (29–163) | 112 (56–169) | 0.029 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 81 (28–145) | 126 (91–194) | 0.001 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 44 (20–92) | 136 (81–219) | 0.001 |

| NLR | |||

| 1st day of ICU stay | 10.36 (5.94–19.56) | 14.85 (7.54–26.58) | 0.006 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | 8.56 (5.25–15.27) | 13.02 (8.40–19.90) | 0.001 |

| Last day of ICU stay | 5.50 (3.69–8.71) | 15.74 (8.00–28.33) | 0.001 |

Table 5 shows a comparison of the patient APACHE II and SOFA scores, NLR, and CRP in patients with or without the occurrence of septic shock and mortality. APACHE II scores on ICU admission were significantly higher in those patients who died in the ICU, independent of septic shock. APACHE II values were similar between those patients who were in septic shock and those that died in the ICU. Patients without septic shock had similar SOFA scores on ICU admission, regardless of their mortality in the follow-up period. There was a significant difference between all of the other patient groups. The NLR on ICU admission was significantly higher in those patients with septic shock and those who died in the ICU, when compared with patients without septic shock and survivors. On the 3rd day in the ICU, the SOFA scores were statistically different in the 4 subgroups. In the subgroup of survivors with no septic shock, the CRP values on the 3rd day in the ICU were significantly lower than in the other groups, and their NLR values were significantly lower than in the septic shock patients, independent of mortality. The CRP values of the survivors on the last day of ICU stay were statistically similar, regardless of the presence of septic shock, but these values were significantly different in the nonsurvivor subgroups. The NLR values on the last day of ICU stay were significantly higher in the nonsurvivors, independent of the presence of septic shock (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of the inflammatory markers and ICU severity scores with the presence of mortality and septic shock in pulmonary sepsis patients in the ICU.

| Variables | aShock – mortality – | bShock – mortality + | cShock + mortality - | dShock + mortality + | P-values | ||||

| n = 330 | Values | n = 33 | Values | n = 117 | Values | n = 111 | Values | ||

| ICU admission | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APACHE II score | 327 | 17 (15–22) | 32 | 24 (20–27) | 117 | 25 (20–30) | 109 | 30 (26–36) | a vs. b < 0.001a vs. c < 0.001a vs. d < 0.001b vs. c = 0.87b vs. d < 0.001c vs. d < 0.001 |

| SOFA score | 329 | 3 (2–4) | 32 | 3 (3–4) | 117 | 6 (5–8) | 111 | 8 (6–10) | a vs. b = 0.68a vs. c < 0.001a vs. d < 0.001b vs. c < 0.001b vs. d < 0.001c vs. d < 0.001 |

| CRP | 264 | 86 (3160) | 28 | 113 (52–152) | 95 | 91 (27–189) | 79 | 102 (57–176) | a vs. b = 0.99a vs. c = 0.97a vs. d = 0.24b vs. c = 0.99b vs. d = 0.24c vs. d = 0.61 |

| NLR | 330 | 10.1(5.7–18.9) | 33 | 13.6 (8.1–22.2) | 117 | 12.7 (7.9–21.5) | 111 | 15.7 (7.5–26.6) | a vs. b = 0.86a vs. c = 0.58a vs. d = 0.009b vs. c = 0.99b vs. d = 0.73c vs. d = 0.38 |

| 3rd day of ICU stay | |||||||||

| SOFA score | 298 | 2 (2–3) | 27 | 4 (3–5) | 117 | 4 (3–6) | 85 | 8 (5–10) | a vs. b = 0.000a vs. c = 0.000a vs. d = 0.000b vs. c = 0.91b vs. d = 0.000c vs. d = 0.000 |

| CRP | 242 | 70 (24–132) | 21 | 112 (80–180) | 100 | 119 (54–175) | 67 | 135 (97–196) | a vs. b = 0.045a vs. c = 0.001a vs. d = 0.000b vs. c = 0.94b vs. d = 0.78c vs. d = 0.09 |

| NLR | 298 | 8.4 (5.0–15.1) | 28 | 12.9 (9.2–17.9) | 115 | 10.1 (6.2–15.4) | 84 | 13.5 (8.3–20.8) | a vs. b = 0.05a vs. c = 0.045a vs. d = 0.000b vs. c = 0.75b vs. d = 0.99c vs. d = 0.32 |

| Last day of ICU stay | |||||||||

| CRP | 282 | 40 (18–92) | 22 | 103 (51–202) | 107 | 53 (23–92) | 75 | 151 (85–221) | a vs. b < 0.001a vs. c = 0.61a vs. d < 0.001b vs. c < 0.001b vs. d = 0.97c vs. d < 0.001 |

| NLR | 324 | 5.5 (3.8–8.6) | 32 | 15.1 (8.2–24.5) | 117 | 5.4 (2.4–8.7) | 103 | 16.0 (8.0–30.5) | a vs. b < 0.001a vs. c = 0.99a vs. d <0.001b vs. c < 0.001b vs. d = 0.31c vs. d < 0.001 |

*Non-parametric Kruskal Wallis Test, median values (25%–75%).

Potential mortality risk factors assessed in the pulmonary sepsis patients during their ICU stay using binary logistic regression are summarized in Table 6. NLR values of 10 and 15, CRP of 100 mg/L and above on admission to the ICU, age and BMI, arrhythmia, shock on admission, number of days in the ICU, and IMV application were not found to be risk factors for mortality in the patient group. However, mortality was shown to be increased by 35.4 times in patients with resistance to the empirical antibiotic treatment (Table 6), and 10.3-fold in patients with partial antibiotic resistance. Mortality increased 7-fold in patients with NLR values of 15 and above on the 3rd day of ICU stay. Each value increase in the APACHE II score on admission to the ICU increased mortality 1.13-fold. Each value increase in the SOFA score on the 3rd day of ICU stay increased mortality 1.5-fold, while each value increase in the SOFA score on the 1st day of ICU stay decreased mortality 0.3-fold (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mortality risk factors evaluated by binary logistic regression in pulmonary sepsis patients in the ICU.

| Odds ratio | CI 95% lower-upper | P-values | |

| Antibiotic response | |||

| Partially responsive | 10.3 | 3.3–31.5 | <0.001 |

| Nonresponsive | 35.4 | 7.9–158.3 | <0.001 |

| 3rd day NLR of ≥15 | 6.96 | 1.42–34.1 | 0.017 |

| 3rd day NLR of ≥10 | 2.71 | 0.63–11.63 | 0.18 |

| 1st day NLR of ≥15 | 1.27 | 0.32–4.92 | 0.72 |

| 1st day NLR of ≥10 | 0.53 | 0.14–2.01 | 0.36 |

| 3rd day SOFA score | 1.57 | 1.23–2.01 | <0.001 |

| 1st day SOFA score | 0.69 | 0.54–0.89 | 0.005 |

| 1st day APACHE II score | 1.12 | 1.03–1.23 | 0.005 |

| 1st day CRP of >100 | 1.04 | 0.40–2.68 | 0.92 |

| 3rd day CRP of >100 | 0.64 | 0.21–1.97 | 0.44 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.94–1.02 | 0.36 |

| BMI | 0.96 | 0.89–1.03 | 0.27 |

| IMV | 2.38 | 0.73–7.76 | 0.15 |

| Arrhythmia | 2.48 | 0.85–7.17 | 0.09 |

| Shock on admission | 2.54 | 0.92–6.99 | 0.07 |

| ICU days | 1.00 | 0.94–1.06 | 0.85 |

CI: confidence interval, BMI: body mass index, IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation.

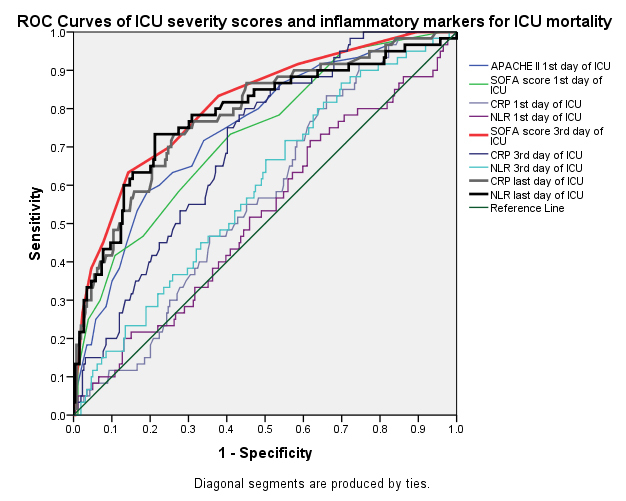

A ROC analysis to predict ICU mortality based on the APACHE II scores (on ICU admission), SOFA scores (on ICU admission and on the 3rd day of ICU stay), and NLR and CRP values (1st, 3rd and last day of ICU stay) is shown in Figure 2, and the AUC values are summarized in Table 7. The AUC values were clinically and statistically significant for the APACHE II and SOFA scores on admission to the ICU, the SOFA scores and CRP values on the 3rd day of ICU stay, and CRP and NLR values on the last day of ICU stay (Table 7).

Table 7.

Area under the curve for mortality in pulmonary sepsis patients in the ICU.

| Test result variable(s) | Area | P-values | Asymptotic 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| SOFA, 3rd day of ICU stay | 0.807 | 0.001 | 0.744 | 0.870 |

| CRP, last day of ICU stay | 0.780 | 0.001 | 0.712 | 0.849 |

| NLR, last day of ICU stay | 0.778 | 0.001 | 0.705 | 0.851 |

| APACHE II, 1st day of ICU stay | 0.740 | 0.001 | 0.672 | 0.809 |

| SOFA, 1st day of ICU stay | 0.723 | 0.001 | 0.652 | 0.795 |

| CRP, 3rd day of ICU stay | 0.699 | 0.001 | 0.632 | 0.766 |

| NLR, 3rd day of ICU stay | 0.579 | 0.06 | 0.501 | 0.658 |

| CRP, 1st day of ICU stay | 0.562 | 0.14 | 0.487 | 0.638 |

| NLR, 1st day of ICU stay | 0.515 | 0.73 | 0.431 | 0.599 |

Figure 2.

Mortality prediction markers in pulmonary sepsis patients in the ICU; ROC curve analysis.

4. Discussion

This study showed that CRP was similar in patients with sepsis and septic shock that developed within the first 24 h following admission to the ICU. Significantly higher NLR levels were found on ICU admission in patients with septic shock when compared with those with sepsis alone. The NLR and CRP values behaved similarly relative to the patient severity and response to treatment during the ICU stay and ICU outcome. The CRP and NLR values on the last day of ICU stay were significant predictors of ICU mortality. The present study also showed that if treatment with inappropriate antibiotics was initiated, mortality increased 35-fold. NLR values equal to or greater than 15 on the 3rd day of ICU stay were associated with a 7-fold increase in mortality. The NLR and CRP showed similar changes when monitoring the response to antibiotics.

4.1. ICU mortality predictors: APACHE II and SOFA scores, NLR, and CRP

Recently, Yu et al. compared different evaluating systems to predict the prognosis of patients with infections outside of the ICU. During the first 12 h before clinical worsening, they reported the AUC for the SOFA score as 0.78, and 0.72 for the APACHE II score [37]. A very recent study by Jain at al., that investigated the SOFA score/ICU mortality relationship, similarly determined that the higher the SOFA score on the 1st, 3rd, and 5th day of ICU stay, the higher the ICU mortality. However, they also showed that SOFA scores on the 7th and 9th day were not associated with mortality [38]. In the present study, the AUC for SOFA score on the 3rd day was the highest value among the other severity indices (Figure 2 and Table 7).

Salciccioli et al. assessed NLR values as a risk factor for mortality in the general ICU. They separated patients into 4 groups based on their NLR values and reported that the presence of sepsis was not an additional risk for mortality when compared with nonsepsis patients [39]. In the same study, 3rd and 4th quarter NLR values were found to be a risk factor for mortality in general ICU patients. The mortality risk coefficients for the 3rd quarter (75%, NLR = 8.90–16.21) and 4th quarter (75%–100%, NLR of ≥16.21) NLR were 1.35 and 1.75, respectively. These were similar to the NLR values of the nonsurvivor sepsis patients in the ICU in the current study (Table 4). Riché et al. investigated the relationship between NLR in patients with septic shock and time of death, i.e. early death (before 5 days) and late death (5th day and after) during ICU stay [27]. The patient groups had either abdominal sepsis (n = 130) or extra-abdominal sepsis (n = 31), and their NLR median values on admission to the ICU were similar (9.0 [interquartile range (IQR) of 4.6–17.9] and 11.5 [IQR of 5.5–18.5], respectively) [27]. In contrast, in the present study, the septic patient populations were of a pulmonary sepsis origin and the early death patients had significantly higher NLR values than in the study by Riché et al. (median NLR 17 vs. 5) (Table 5). It was also shown that early nonsurvivor sepsis patients had a significantly higher rate of septic shock, and higher inflammatory marker values and ICU severity scores than sepsis patients without shock.

4.2. Antibiotic response: CRP, NLR, and procalcitonin

Schmit et al. investigated the clinical course of CRP in response to initial antibiotic therapy in sepsis patients. They found CRP to predominantly increase within the first 48 h of treatment, and by at least 2.2 mg/dL [40]. These findings were similar in patients in the current study who were partially sensitive or resistant to antibiotics; they tended to have elevated CRP levels on the 3rd day of ICU stay. Renny et al. indicated that a drop in CRP of 50 mg/dL or more from ICU admission to the 4th day of ICU stay was a good cutoff value for anticipating recovery in sepsis patients [41]. The CRP and NLR values on the 1st and 3rd day of ICU stay in sepsis patients in the present study were assessed according to guidelines that suggested that the response to the initial antibiotic therapy should be assessed by a regression in biomarkers and clinical response within the first 48–72 h [42]. While the CRP and NLR values increased on the 3rd day in the partially-sensitive and antibiotic-resistant patient groups, the CRP and NLR values decreased on the last day following treatment modification.

Gürol et al. assessed procalcitonin as a reference and predictor of sepsis and septic shock and compared it with the NLR, CRP and leucocyte counts using ROC analysis [43]. They concluded that the strongest indicator for sepsis was NLR. If the NLR was equal to 5 or above, it indicated a sepsis diagnosis, and the requirement for treatment and follow-up of infection in a critically ill patient. The authors defined procalcitonin values from 2–10 ng/mL in patients with sepsis and 10 ng/mL in patients with septic shock. They also defined values for NLR in the range of 13–15 for patients with sepsis and over 15 for patients with septic shock. Unlike their study, in which admission values with suspected bacteremia were taken into account, patients in the present study had pulmonary sepsis. Significantly higher values of NLR and CRP were observed in patients with sepsis and septic shock in the ICU (Table 1). After empirical antibiotic therapy, the NLR and CRP were significantly higher on the 3rd day in the nonresponsive sepsis/septic shock patients (Table 2).

4.3. Limitations

A limitation of this study was that it was retrospective and single-centered. However, given that the center where the patients’ records were taken from and the study was done at had a consistent team of ICU physicians who implemented a specific sepsis protocol, we can say that the data were controllable, even if acquired retrospectively. We believe that the results presented herein are significant, as the number of patients assessed was high and they were treated and followed by a specific group of physicians. A further limitation was that the sepsis patients were of a pulmonary origin and the study was conducted in the pulmonary ICU. Thus, we could not generalize our results for other causes of sepsis. Nevertheless, pulmonary originated sepsis is a frequently occurring type of sepsis encountered by intensivists in the intensive care [44]. We believe that our data is valuable for ICU physicians in clinical practice.

4.4. Conclusions

For patients with sepsis and septic shock, NLR and CRP values on admission to the ICU (within the first 24 h) are not as valuable as the 1st day SOFA and APACHE II scores for predicting mortality. The NLR is as valuable as CRP for assessing the response to empirically initiated antibiotic treatment in sepsis patients. NLR values of >15 on the 3rd day of ICU stay can be used to predict mortality. We suggest using NLR values for sepsis patients in the first 3 days to assess follow-up and antibiotic treatment. Further studies are required to clarify these results and to assess the utility of NLR as a predictor of mortality and treatment response in other sepsis and septic shock patient populations.

References

- Bone RC Balk RA Cerra FB Dellinger RP Fein AM Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. 1992;101:1644. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MM Fink MP Marshall JC Abraham E Angus D Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31:1250. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RP Carlet JM Masur H Gerlach H Calandra T Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32:858. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000117317.18092.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger RP Levy MM Rhodes A Annane D Gerlach H Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41:580. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus WA Zimmerman JE Wagner DP Draper EA Lawrence DE. APACHE -acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1981;9:591. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL Moreno R Takala J Willatts S Mendon De The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Medicine . 1996;22:707. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez-Camacho C Losa J Biomarkers for sepsis. Biomed Research International. 2014;10 doi: 10.1155/2014/547818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakos C Vincent JL Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Critical Care. 2010;14 doi: 10.1186/cc8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstern C Brenner T Bardenheuer HJ MA Weigand Predictors of survival in sepsis: what is the best inflammatory marker to measure? Current Opinion Infectious Diseases. 2012;25:328. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283522038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet P Christen G Seematter G Que YA Eggimann P Usefulness of biomarkers of sepsis in the ICU. Revue Medicale Suisse. 2011;7:2430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker C Prkno A Brunkhorst FM Schlattmann P Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2013;13:426. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y Mao Y He X Sun Y Huang S The values of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in predicting 30 day mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. . BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2016;16:123–123. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0304-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadesham VP Lagarde SM Immanuel A Griffin SM Systemic inflammatory markers and outcome in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. British Journal of Surgery. 2017;104:401. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LE Alhazzani W Levy MM Antonelli M Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Medicine. 2017;43:304. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigl M Raggam RB Wagner J Prueller F Grisold AJ Procalcitonin fails to predict bacteremia in SIRS patients: a cohort study. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2014;68:1278. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand D Das S Bhargava S Srivastava LM Garg A Procalcitonin as a rapid diagnostic biomarker to differentiate between culture-negative bacterial sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a prospective, observational, cohort study. Journal of Critical Care. 2015;30:218–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif SK Sumange Rukka AB Wahyuni S. Comparison of neutrophils-lymphocytes ratio and procalcitonin parameters in sepsis patient treated in intensive care unit Dr. Wahidin Hospital. 2017;17:17. [Google Scholar]

- Naess A Nilssen SS Mo R Eide GE Sjursen H. Infection Role of neutrophil to lymphocyte and monocyte to lymphocyte ratios in the diagnosis of bacterial infection in patients with fever. Infection. 2017;160:299. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0972-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde VS Kakrani VA Gokhale VS Thombre SK Landge JA Comparison of neutrophil to lymphocyte count ratio, APACHE II score and SOFA score as prognostic markers in the setting of emergency medicine. International Journal of Healthcare and Biomedical Research. 2016;4:46. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SY Shin TG Jo IJ Jeon K Suh GY Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in critically-ill septic patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;35:234. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh GH Chung SP Park YS Hong JH Lee HS Mean platelet volume to platelet count as a promising predictor of early mortality in severe sepsis. Shock. 2017;47:323. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W Wang X Zhang W Ying H Xu Y Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio are 2 new inflammatory markers associated with pulmonary involvement and disease activity in patients with dermatomyositis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2017;465:11. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman D Aksoy E Agca MC Kocak ND Ozmen I The utility of inflammatory markers to predict readmissions and mortality in COPD cases with or without eosinophilia. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2015;10:2469. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S90330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahorec R Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratislavske Lekarske Listy. 2001;102:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernestig m L Jacobsson AK Andersson G Usener R B Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin, neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio, C-reactive protein, and lactate in patients with suspected bacterial sepsis. PLoS ONE. 12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jager CP Wijk PT Mathoera RB de Jongh-Leuvenink J van der Poll T Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Critical Care. 2010;14 doi: 10.1186/cc9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich Gayat E my R Le Dorze M o J Reversal of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte count ratio in early versus late death from septic shock. Critical Care. 2015;233:439–439. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd J Rodriguez-Roisin SS R The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of-why and what? Clinical Respiratory Journal. 6:208. doi: 10.1111/crj.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt rk C Karakurt Z Adiguzel N Kargin F Sari R Does eosinophilic COPD exacerbation have a better patient outcome than non-eosinophilic in the intensive care unit. International Journal o. f Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2015;25210:1837. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S88058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger P Hill N Criner G. Clinical indications for noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in chronic respiratory failure due to restrictive lung disease, COPD, and nocturnal hypoventilation-a consensus conference report. Chest. 1999;116:521. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava S Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2009;374:250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler CN Gosnell MS Grap MJ Brophy GM Neal PV The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002;8217166:1338. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles JM Bion J Connors A Herridge M Marsh B Weaning from mechanical ventilation. See comment in PubMed Commons belowThe European Respiratory Journal. 2007;29:1033. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S Leung S Heo M Soto GJ Shah RT See comment in PubMed Commons Comparison of risk prediction scoring systems for ward patients: a retrospective nested case-control study. Critical. 2014;18 doi: 10.1186/cc13947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A Palta S Saroa R Palta A Sama S Sequential organ failure assessment scoring and prediction of patient’s outcome in intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital. . 2016;32:364. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.168165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salciccioli JD Marshall DC Pimentel MA Santos MD Pollard T The association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mortality in critical illness: an observational cohort study. Critical Care. 2015;19:13–13. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0731-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reny JL Vuagnat A Ract C Benoit MO Safar M Diagnosis and follow-up of infections in intensive care patients: value of C-reactive protein compared with other clinical and biological variables. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30:529. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland HD O Neal T Biek D CANVAS 1 and 2: analysis of clinical response at day 3 in two phase 3 trials of ceftaroline fosamil versus vancomycin plus aztreonam in treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotheraphy. 821756:2231. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05738-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürol G Terizi HA Atasoy AR Ozbek A Are there standardized cutoff values for neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in bacteremia or sepsis? Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2015;25:521. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1408.08060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calandra T Cohen J The international sepsis forum consensus conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33:1538. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168253.91200.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]