INTRODUCTION

In August 2019, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) released its new hypertension guidelines.1 This article highlights the key recommendations and changes since 2011.

DIAGNOSING HYPERTENSION

The diagnostic threshold for hypertension remains 140/90 mmHg on clinic blood pressure (BP). As previously, it is recommended that diagnosis is based on out-of-office measurement, given the risk of white-coat hypertension, defined as a difference of >20/10 mmHg between clinic readings and average daytime home or ambulatory measurements. The gold standard is ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) but, as this is not suitable or tolerated by everyone, home BP monitoring (HBPM) is offered as an alternative. For HBPM, patients should be advised to take at least two recordings, 1 minute apart, twice a day for 4 to 7 days. The first day of readings should be discounted and the mean of the remaining readings used. If the mean BP is close to the diagnostic threshold, ABPM may be needed to confirm the diagnosis, particularly in younger people (for example, aged <60 years) where the implications of a new hypertension diagnosis may be more significant. The diagnostic threshold for ABPM or HBPM remains 135/85 mmHg. Standing BP should be measured in those with type 2 diabetes, aged ≥80 years, and patients with symptoms of postural hypotension. The standing BP should be measured after the person has been standing for at least 1 minute. Where there is a significant postural drop in systolic BP (>20 mmHg), treatment should be targeted at the standing BP.

BETWEEN-ARM BLOOD PRESSURE DIFFERENCES

BP should be checked in both arms at the time of diagnosis as a significant difference in readings between arms is an important marker of vascular disease and can lead to undertreatment.2 In recognition, NICE lowered its definition of what is considered a significant between-arm difference from 20 mmHg to 15 mmHg. BP should be measured consistently in the arm with higher BP during subsequent monitoring where possible.

RECOGNITION OF MALIGNANT HYPERTENSION

Urgent admission for BP assessment or control is only recommended for individuals with stage 3 hypertension (BP >180/120 mmHg) (Table 1) who also have signs of acute end organ damage, including papilloedema or retinal haemorrhage, or life-threatening symptoms such as acute chest pain, confusion, or decompensated heart failure. Urgent admission is also recommended if a phaeochromocytoma is suspected based on significant hypertension alongside symptoms such as headache, abdominal pain, pallor, or diaphoresis.

Table 1.

Hypertension stages

| Hypertension stage | CBPM threshold | ABPM/HBPM threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | 140/90 | 135/85 |

| Stage 2 | 160/100 | 150/95 |

| Stage 3 | 180/120 | Does not Require ABPM/HBPM |

ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure measurement.

CBPM = clinic blood pressure measurement.

HBPM = home blood pressure measurement.

In the absence of one of these indications for acute referral, NICE suggests assessing for target organ damage and, if present, considering initiating treatment without waiting for ABPM or HBPM. If there is no evidence of target organ damage, the clinician should repeat a clinic BP within 1 week and re-evaluate.

TREATMENT THRESHOLDS

Patients newly diagnosed with hypertension should be offered tests for target organ damage (fundoscopy, urinalysis, renal function, ECG) and a cardiovascular risk score calculated (for example, using the latest version of the QRISK score for patients residing in the UK). Treatment is now suggested for patients aged <80 years with stage 1 hypertension who have a 10-year risk score of ≥10%, or those with either target organ damage, renal disease, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes. This brings the risk threshold for treatment in hypertension in line with that for statins.3 The reduction in risk threshold from 20% was driven by a new cost-effectiveness analysis, which found that initiating treatment at the 10% threshold gave an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of 10 000 GBP at age 60 years and therefore was deemed to be cost-effective.4 Treating at a 5% risk threshold may be also cost-effective in patients aged <60 years and, given risk calculators tend to underestimate lifetime cardiovascular risk in these younger people, NICE suggests considering treatment for patients diagnosed before 60 years of age where the QRISK is <10%, based on shared decision making and patient preference. The recommendation means that most patients with stage 1 hypertension aged between 60 and 80 years will now be eligible for treatment. In practice around 50% of those with uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension in the UK are already prescribed BP-lowering medication and many of these have <10% risk, suggesting that a shift in treatment focus might mean little additional workload.5

Other than the landmark HyVET trial, which used a treatment threshold of 150 mmHg systolic BP, there is a lack of evidence regarding treatment targets for patients aged >80 years and the potential risks of treatment are greater in this group.6 NICE therefore advocates clinicians judging whether to recommend treatment based on individual case merit but taking into account factors such as frailty and other comorbidities, particularly where treatment below 150 mmHg is being considered.

Hypertension in patients with diabetes is now included in the guideline and, importantly, the thresholds for both diagnosis and treatment have been brought into line with the recommendations for patients without diabetes. The ACCORD study found no benefit in terms of fatal and non-fatal major cardiovascular events when patients with type 2 diabetes were treated to a target systolic BP of 120 mmHg compared with 140 mmHg.7,8

For patients aged <80 years, treatment should aim to reduce clinic BP below 140/90 mmHg or 135/85 mmHg if using HBPM. Unlike recent US and European guidance, NICE does not suggest aiming for lower BP targets, because of a lack of evidence in primary prevention as well as the increased risk associated with this strategy, including falls and electrolyte imbalance.4,9

TREATMENT APPROACH

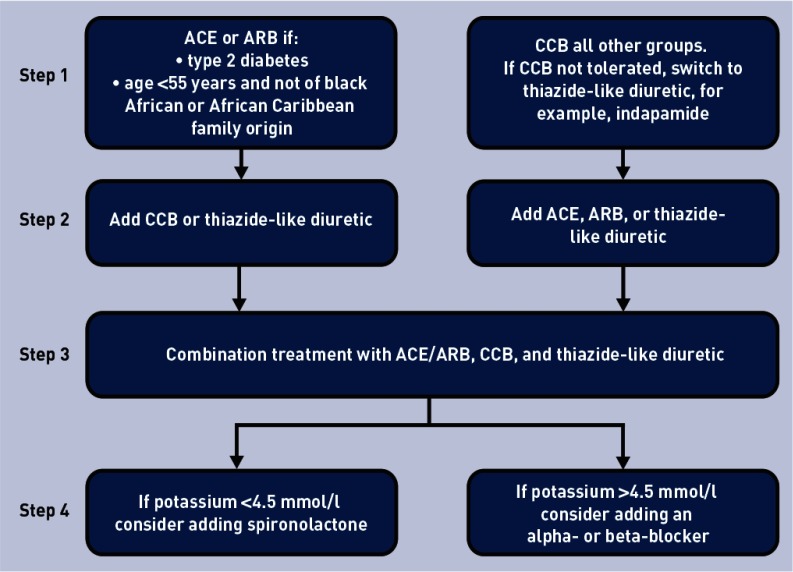

Clinicians should offer regular lifestyle advice, including diet and exercise, to all patients with suspected or diagnosed hypertension. Figure 1 shows the treatment flow chart for people with hypertension. Dual therapy (for example, with an ACE and CCB) is not recommended in the first instance, even if a combined pill is used, as NICE found insufficient evidence regarding the risks and benefits of this approach, and suggests further research is needed in this area.

Figure 1.

Treatment flow chart. aAt each step optimise medication dose and check adherence. At step 4, consider confirming the blood pressure measurement is accurate with home or ambulatory readings. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme. ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker. CCB = calcium channel blocker.

Patients with hypertension should receive at minimum an annual review, to discuss BP, lifestyle, symptoms, and medication. If BP control is inadequate on a single agent, a second drug should be added (Figure 1). Step 3 treatment combines an ACE/ARB, CCB, and thiazide-like diuretic at optimal tolerated doses. Patients who remain hypertensive despite this are considered to have resistant hypertension. Adherence should be checked and BP readings using ABPM or HBPM confirmed. If further treatment is indicated, low-dose spironolactone may be most suitable for those with a potassium level of ≤4.5 mmol/l, or an alpha- or beta-blocker for other patients. More frequent monitoring and expert advice may be required.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NICE.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management NG136. 2019. https://www.niceorg.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed 11 Dec 2019). [PubMed]

- 2.Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Campbell JL. The difference in blood pressure readings between arms and survival: primary care cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification CG181. 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 (accessed 11 Dec 2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunström M, Carlberg B. Association of blood pressure lowering with mortality and cardiovascular disease across blood pressure levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):28–36. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheppard JP, Stevens S, Stevens RJ, et al. Association of guideline and policy changes with incidence of lifestyle advice and treatment for uncomplicated mild hypertension in primary care: a longitudinal cohort study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e021827. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckett N, Peters R, Tuomilehto J, et al. Immediate and late benefits of treating very elderly people with hypertension: results from active treatment extension to Hypertension in the Very Elderly randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;344:d7541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjeldsen SE, Hedner T, Jamerson K, et al. Hypertension optimal treatment (HOT) study: home blood pressure in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1998;31(4):1014–1020. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.4.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accord Study Group. Cushman WC, Evans GW, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheppard JP, Stevens S, Stevens RJ, et al. Benefits and harms of antihypertensive treatment in low-risk patients with mild hypertension. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1626–1634. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]