Abstract

Self-regulation processes assume a major role in health behaviour theory and are postulated as important mechanisms of action in behavioural interventions to improve health prevention and management. The need to better understand mechanisms of behaviour change interventions for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) called for conducting a meta-review of meta-analyses for interventions targeting self-regulation processes. The protocol, preregistered on Open Science Framework (OSF), found 15 eligible meta-analyses, published between 2006 and August 2019, which quantitatively assessed the role of self-regulatory mechanisms and behaviour change techniques (BCTs). Quality of the meta-analyses varied widely according to AMSTAR-2 criteria. Several BCTs, assumed to engage self-regulatory mechanisms, were unevenly represented in CVD meta-analytic reviews. Self-monitoring, the most frequently studied self-regulatory BCT, seemed to improve health behaviour change and health outcomes but these results merit cautious interpretation. Findings for other self-regulatory BCTs were less promising. No studies in the CVD domain directly tested engagement of self-regulation processes. A general challenge for this area stems from reliance on post-hoc tests of the effects of BCTs in multiple-component interventions. Recent advances in BCT taxonomies and the experimental medicine approach to engaging self-regulation mechanisms, however, provide opportunities to improve CVD prevention and management behavioural interventions.

Keywords: meta-review, self-regulation, prevention, intervention, behaviour change techniques, cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has contributed to the soaring worldwide prevalence of health and economic burdens (Benjamin et al, 2019). The latest released estimates suggest that as of 2016, approximately 17 million deaths can be attributed to CVD globally, representing about a 14% increase from 10 years earlier, although age-adjusted estimates trend more positively (Benjamin et al, 2019). The prevalence of morbidity and mortality from infectious disease has fluctuated slightly from decade to decade globally, but these statistics show a sharp decrease over the last century (Armstrong, Conn, & Pinner, 1999). This favourable trend has not been mirrored in the prevalence of “degenerative and man-made diseases,” at least in the United States (U. S. Burden of Disease Collaborators et al, 2018). Rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, and other CVD conditions have plateaued and increased in some groups (Vaughan, Ritchey, Hannan, Kramer, & Casper, 2017). In the United States, CVD claims more lives each year than cancer and chronic lung disease combined, and it remains the number one cause of death (Benjamin et al, 2019). In one recently conducted estimate, by 2035, over 45% of the U.S. population will likely have some type of CVD, with costs of these diseases projected to total 1.1 trillion U.S. dollars (RTI International, 2016). The commonness and cost of CVD events makes the prevention and successful management of CVD of paramount importance.

All major national and international guideline and advisory groups recommend interventions, which rely on successful health behaviour change, to prevent CVD events (Piepoli et al, 2016; LeFevre M.L. & U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2014). Their recommendations follow from epidemiological findings attributing the majority of global CVD conditions to modifiable risk factors, particularly unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, such as smoking, lack of physical inactivity, and an unhealthy diet (Benjamin et al, 2018). In the United States, offering or referring adults at CVD risk (e.g., those with elevated body mass index or hypertension) to intensive behavioural counselling interventions to promote a healthful diet and healthful physical activity (PA) is a primary CVD prevention strategy and is recommended nationally (LeFevre M.L. & U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2014). Healthful dietary counselling includes recommendations on decreasing total and saturated fat and total calories and on increasing fruits and vegetables. Exemplar dietary interventions are the Diabetes Prevention Program (Knowler et al, 2002) and the PREMIER intervention (Elmer et al, 2006).

Most CVD prevention recommendations and guidelines rely on research that tests the efficacy of health behaviour change interventions. However, even when an intervention changes a health behaviour, such as increasing PA, how the intervention succeeded often remains unclear, effectively limiting its implementation. So, identifying the mechanisms of action (MoA)—the causal processes that underlie successful health behaviour change—seems vital. Most CVD prevention and management guidelines targeting health behaviour recommendations, however, lack the description of the mechanism(s) of action required to produce health behaviour change.

According to several health behaviour theories (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Bandura, 2004; Carver & Scheier, 1982; Michie & Johnston, 2012), self-regulation is a central MoA in health behaviour change. “Self-regulation” refers to the “ability to flexibly activate, monitor, inhibit, persevere, and/or adapt one’s behaviour, attention, emotions, and cognitive strategies in response to direction from internal cues, environmental stimuli and feedback from others, in an attempt to attain personally-relevant goals” (Moilanen, 2007 in van Genugten, Dusseldorp, Massey, & van Empelen, 2017; also see Naragon-Gainey, McMahon, & Chacko, 2017). Self-efficacy is an example of a particular self-regulation MoA, and one that is highly relevant to successful behaviour change (Bandura, 2004).

The science of behaviour change for CVD prevention and management assumes that self-regulatory MoA’s can be set in motion by particular behavioural strategies included in interventions. Referred to as “behaviour change techniques” (BCTs), the strategies represent the “active ingredients” of behaviour change theories and are observable, replicable, irreducible intervention components (Abraham & Michie, 2008; Michie et al., 2011;Michie et al, 2013). These include self-monitoring, goal setting, problem-solving, etc. Frequently, behavioural intervention trials often bundle many BCTs.

This meta-review was conducted to evaluate the state of knowledge about the coverage and efficacy of self-regulatory processes in CVD behaviour change interventions. We identified meta-analyses of behavioural intervention studies including measures of self-regulation and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) postulated to trigger self-regulation processes. (e.g., Bandura, 2004; Michie et al., 2013). Then, empirical coverage in the meta-analyses of MoA’s and BCTs and their associations with health behaviour change and relevant health outcomes are reviewed. As an example, a meta-analysis might evaluate CVD behavioural intervention studies using both self-monitoring and goal review (i.e., BCTs) to enhance self-efficacy (i.e., MoA), which increases PA (the health behaviour), which improves physical fitness (the health outcome). By conducting a comprehensive meta-review, we hoped to better understand the science of behaviour change and identify the gaps in evidence for CVD prevention and management.

Methods

Preregistration materials for this meta-review can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF; osf.io/yheg8). An initial list of meta-analyses of CVD-relevant behavioural interventions was obtained from a broader search conducted in August 2017 to identify quantitative reviews of behavioural intervention studies across several health domains (Hennessy et al., in press. Seven eligible CVD meta-analyses were retrieved. For the sake of comprehensiveness and timeliness, a second search conducted in August 2019 and focusing only on CVD, identified another eight meta-analyses. Prior to both searches, senior research team members experienced in systematic review processes trained undergraduate and graduate students on the protocol, screening instruments and data extraction, and the assessment of meta-analytic quality. Eppi-Reviewer (Thomas, Brunton, & Graziosi, 2010) enabled the literature screening and the survey function in RedCap (Harris et al, 2009) facilitated data extraction, including AMSTAR 2 quality assessment. Analyses relied on Stata 15.1 (2017). The next sections describe the steps and procedures used for screening, data extraction, and quality assessment.

Inclusion Criteria

To be eligible, CVD meta-analyses had to evaluate single or multi-component health behaviour intervention trials that quantitatively assessed self-regulation mechanisms or specific BCTs that we determined would initiate the process of self-regulation. The meta-analyses needed to be applicable to the general public or noninstitutionalised individuals, although reviews which included restrictions to population diagnoses of certain disorder(s) could also qualify. For example, if the population only consisted of individuals diagnosed with a depressive disorder, but not institutionalised due to the diagnosis, then the meta-analysis remained eligible.

Reviews of drug-based treatments were excluded unless a component of the intervention addressed improving medication adherence and not the effects of the drug itself. Exclusion criteria also extended to reviews that focused on self-regulation strategies outside the context of an intervention/treatment and behaviour change (e.g., the impact of PA on cognition). Reviews qualified for inclusion if the studies had used any of several comparator groups composed of another intervention of equal, lesser, or greater intensity than the one of primary interest (e.g., treatment as usual, wait-list control, intervention + additional components).

Health behaviours and health-related outcomes of those behaviours had to be linked to CVD (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019). Illustrative behaviours were nutrition, PA, blood pressure (BP) monitoring, substance abuse, and tobacco use. Specific health outcomes of interest included diet, medical regimen adherence, reduced weight, fitness level (i.e., ability to withstand a physical workload and to recover in a timely manner), BP levels, substance use and mortality.

Primary outcomes consisted of quantitative associations between any self-regulatory MoA or BCT theorised to affect self-regulation and any CVD-relevant behaviour change and/or outcome. Initial screening by research team members indicated that BCTs appeared frequently in CVD meta-analyses. Consequently, the team reviewed and discussed the most current and complete behaviour change taxonomies for intervention techniques relevant to self-regulation. These discussions resulted in consensus that interventions including any of the following 11 BCTs were most relevant to self-regulatory processes (Michie et al, 2013) and eligible for the review: (1) goal setting, (2) review of goals, (3) self-monitoring, (4) emotional control training, (5) self-talk, (6) stress management, (7) action planning, (8) barrier identification/problem-solving, (9) relapse prevention/coping planning, (10) time management, and (11) provision of feedback.1 Other BCTs (from behaviour change taxonomies; see below) and closely related intervention methods, such as “inhibitory control training,” also received consideration. Any additional candidate intervention components found during coding were discussed by the team and included in the review if consensus was reached. Neither search, however, found any CVD meta-analyses meeting inclusion criteria and reporting BCT results, other than the 11 noted above.

To be eligible, meta-analyses had to quantitatively compare behavioural (e.g., physical activity) and/or health (e.g., fitness level) outcomes as a function of the presence/absence of the 11 intervention techniques, or directly test the efficacy of a self-regulatory MoA. The reviews reported post-hoc statistical tests that compared pooled data across different trial conditions or conducted subgroup analysis, meta-regression, or sensitivity analysis. To be relevant to current practice (Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer, & Eikermann, 2014; Thomson, Russell, Becker, Klassen, & Hartling, 2010), meta-analyses published before 2006 were excluded unless they were linked to an updated review published after that date. Fifteen meta-analyses met the inclusion criteria for this CVD meta-review.

Search, Training and Screening Process

For the original search, two reference librarians piloted searches to refine the search strategy, and two team members searched multiple electronic databases in August 2017. The PubMed search terms, which were modified to suit other electronic databases, can be found in the online supplemental materials. The searches used the following electronic databases: PubMed (National Library of Medicine), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), EMBASE (Scopus), PsycINFO (American Psychological Association), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane). Searches for additional eligible meta-analyses examined the bibliographies of eligible reviews and meta-reviews. Reviews with any type of publication status or language of publication were eligible.

Following the electronic searches, training for full-text screening commenced with eight team members independently screening the same 25 titles and abstracts. Discrepancies were reviewed and the screening protocol was clarified. Then 10% of the meta-analyses were screened independently and in duplicate at the title/abstract level (approximately 411 per person). After computing discrepancy statistics, discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Prior to full-text review, the scope was modified to focus only on behaviours and not mental health outcomes. Three of the senior project members re-reviewed potentially eligible titles/abstracts and categorised them as mental health outcomes only or behavioural outcomes. If a meta-analysis focused on behaviour and mental health outcomes, it was eligible, but only the behaviour outcomes were used in the descriptive synthesis. This subset of potentially eligible titles/abstracts with behaviour outcomes populated a list of full-text articles to retrieve and screen.

Next, training for full-text screening commenced with eight team members independently screening a random set of 15 meta-analyses from the initial 66 (all health domains). Screening of these 15 was reviewed, discrepancies were discussed, and the screening manual was updated with clarifications. The remaining set of full texts was split between the team with the first 25 in each set used to assess agreement between screeners (independently and in duplicate), in which senior members were paired with junior team members. Junior team members were then paired with another team member for double-screening, and senior team members screened the remaining full texts independently.

All 66 meta-analyses retrieved in the first literature search and considered eligible for the parent meta-review were again reviewed by three senior team members and thematically categorised via discussion and consensus into health domains of interest (e.g., CVD, diabetes, substance use, tobacco). Based on the initial search, seven meta-analyses qualified for the CVD meta-review.

To be comprehensive and timely as possible, in August 2019, searches were updated in PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. The terms from the original searches were combined with CVD-specific terms (“cardiovascular OR CVD OR coronary OR cardiac OR heart OR myocardial OR hypertens* OR ‘high blood pressure’”). Copies of all of the search strategies are in the Appendix. Database records were de-duplicated in EndNote and the bibliographies of the eligible studies checked for any potential additional reviews. Records were screened for eligibility at the title and abstract stage, and then by two independent reviewers at the full-text stage. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow chart for the meta-analysis screening process for both searches.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart: Flow of reports and meta-analyses into the meta-review.

Note. MH = Mental Health.

Data Extraction

The first third (l = 22) of the 66 meta-analyses from the initial search and meeting the inclusion criteria were coded independently and in duplicate by three independent reviewers using a standardised coding form (see the Coding Form in the online supplemental materials). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. For the remaining studies from the initial search and the updated search, one coder independently extracted data that were checked for accuracy by one senior team member. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Coders indicated whether a self-regulatory MoA was tested and which of the 11 BCTs and self-management interventions were reported in each meta-analysis (see the “Key” sheet in the Data File in the online supplemental materials). Type of population, health behaviours, health outcomes (and whether objective and/or subjective) were also coded. Coders extracted (a) if a subgroup analysis was conducted, the number of studies with the BCT component; (b) the number without the BCT; (c) the total number of primary studies contributing to the effect size; (d) whether the BCT produced significantly better results; (e) any heterogeneity statistics provided; (f) whether heterogeneity was significant; and (g) the I2 value (see the “Key” sheet in the Data File in the online supplemental materials). Descriptive and inferential statistics for the study interventions (see the “All Outcomes” sheet in the Data File in the online supplemental materials) and BCTs were extracted from each meta-analysis and recorded on separate sheets for each BCT (e.g., “Self-Monitoring”, “Goal Setting”). Sample sizes and other pertinent data were also recorded (see the “All Outcomes” sheet in the Data File in the online supplemental materials with variables and data). Coders also extracted other kinds of information (see the “Key” sheet in the Data File in the online supplemental materials) that are not critical for this meta-review.

Assessment of Meta-Analysis Quality

Two independent reviewers used the AMSTAR-2 tool (Shea et al, 2007) to assess the risk of bias of the meta-analyses that met the inclusion criteria of the parent meta-review on 16 dimensions (e.g., tested for heterogeneity of effects, tested for publication bias). The first third (I = 22) of the meta-analyses meeting the inclusion criteria in the initial search were independently rated and in duplicate. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. For the remaining meta-analyses from the first search and for all meta-analyses in the updated search that met inclusion criteria, one coder independently assessed the risk of bias, and ratings were checked for accuracy by one senior member. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Table 1 (column 1) lists the quality criteria, such as describing study selection criteria, details about coding, tested for risk of bias, tested for heterogeneity, etc. “PICO,” indicates how many of following four criteria —population, intervention, comparator group, and outcome—were satisfied. (PICO, preceded AMSTAR-2, but is included in the latter, because it is a convenient and easily memorised framework [Shea et al., 2007].) The AMSTAR-2 tool was slightly modified for the two questions that address the primary study design of included studies. These two questions were broken into two parts to capture those meta-analyses that included only randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) versus those that included both RCTs and nonrandomised studies of interventions (NRSIs) because the appropriate methods for addressing each type of study design in a review differ.

Table 1.

AMSTAR-2 Quality Coding X Review X Quality Criteria

| Study |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Criteria | Bray (2010) | Chase (2016) | Fletcher (2015) | Glynn (2010) | Goodwin (2016) | Janssen (2013) | Kanejima (2019) | Mills (2018) | Morrissey (2017) | Murray (2017) | Parry (2018) | Sakakibara (2017) | Samdal (2017) | Tucker (2017) | Yue (2019) |

| PICO | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Protocol | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | PY | Y | PY | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Study design criteria | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Literature search | PY | PY | PY | Y | N | N | N | PY | Y | N | N | N | PY | PY | N |

| Study selection | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Coding | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Excluded studies | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Included studies – detail | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| RoB - RCTs | N | PY | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| RoB - NRSIs | NA | N | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Funding sources | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Meta-analysis methods - RCTs | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Meta-analysis methods - NRSIs | NA | N | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Assess RoB impact | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Incorporate RoB | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Heterogeneity | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Publication bias | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| COIs reported | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

Note. PICO = specification of inclusion criteria including the population, intervention, comparison, outcome; RoB = risk of bias; RCT = randomised controlled trial; NRSI = non-randomised studies of interventions; COI = conflicts of interest; Y = yes; N = no; PY = partial yes; NA = not applicable.

To gain a clearer understanding of the relative quality of reviews included in this meta-review, we calculated an overall summary score based on the proportion of AMSTAR-2 items that reviews met. AMSTAR-2 items with No/Partial Yes/Yes options received scores of 0/1/2, respectively, while items with No/Yes options were given scores of 0/2. The total calculation of the AMSTAR completion score for each meta-analysis represented the sum of only the applicable items. For example, in the case of a meta-analysis that excluded nonrandomised trials, risk of bias of nonrandomised trials was not applicable (NA). The overall AMSTAR-2 item completion score for each meta-analysis represents the proportion of items satisfying the total number of relevant quality criteria, with a score of 1.00 signifying all criteria were satisfied. Practices for meta-reviews vary with respect to whether all meta-analyses are included regardless of quality or meta-analyses of lower quality are excluded from consideration (Wu et al, 2019). A compromise strategy, adopted here, reports the results of all 15 CVD meta-analyses, but with qualifiers based on the AMSTAR-2 item completion score or specific criteria. Table 1 presents a fine-grained coding of subsets of AMSTAR-2 items to indicate whether, for example, all or only a partial number of PICO aspects satisfied the criteria. As a rough guide to relative quality, meta-analyses satisfying at least 75% of the items were considered of higher quality, 50 to 66% of medium quality, and less than 50% of lower quality.

Syntheses

Specific aims of this meta-review of 15 CVD meta-analyses involved the determination of (a) the range of coverage for direct tests of self-regulatory mechanisms and 11 self-regulatory BCTs, (b) their associations with improved performance of CVD-relevant health behaviours and health outcomes, and (c) the quality of each meta-analysis. We also calculated the degree of overlap of primary studies across meta-analyses (Pieper et al, 2014) because we expected reviews of the CVD domain included some of the same primary studies. Appreciable overlap could obscure conclusions of the meta-review by over-representing findings that contributed to more than a single meta-analysis. When such overlap was evident, we provided the appropriate caveats (see below).

Results

Across the fifteen meta-analyses, the number of eligible studies ranged from 3 to 100 (M = 25.6, SD: 19.6). Thirteen of 15 meta-analyses reported the year when searches for eligible studies were conducted, with a range from 2008 to 2017. The lag from search to publication was between 1 and 3 years, except for Goodwin, Ostuzzi, Khan, Hotopf, and Moss-Morris (2016), which was published in the same year as the search. For the 14 reviews reporting the number of participants, the mean was 16,236 (range 693–61,690). Thirteen of the 15 reviews required a study to be a randomised or quasi-randomised clinical trial to be included.

Study Overlap Among Meta-analyses

The incidence of overlapping studies in the 15 meta-analyses was less than 2%, which is considered minimal (Pieper et al., 2014). However, there was a greater degree of overlap for six meta-analyses (52.4%) (Bray, Holder, Mant, & McManus, 2010; Fletcher, Hartmann-Boyce, Hinton, & McManus 2015; Glynn, Murphy, Smith, Schroeder, & Fahey, 2010; Mills et al, 2018; Tucker et al, 2017; Yue et al, 2019). All of these studies reviewed interventions for the control of blood pressure (BP) or hypertension. While four had similar inclusion criteria (Bray et al., 2010; Fletcher et al., 2015; Tucker et al, 2017), Yue et al (2019) considered only e-health interventions and limited the years of publication from 2000 to 2017, and Mills et al (2018) looked for trials comparing the effect of implementation strategies versus usual care. A major difference among these meta-analyses was their reported search strategies: Yue et al (2019) used 10 databases; Bray et al (2010) used six and contacted study authors for additional information; Glynn et al (2010) and Tucker et al (2017) used three; and Fletcher et al (2015) and Mills et al (2018) used only two. Interestingly, Mills et al (2018), which only searched two databases, found the highest number of primary studies. The study overlap among the BP control meta-analyses merits a special note of caution for one BCT (see below).

Methodological Quality of the Meta-Analyses

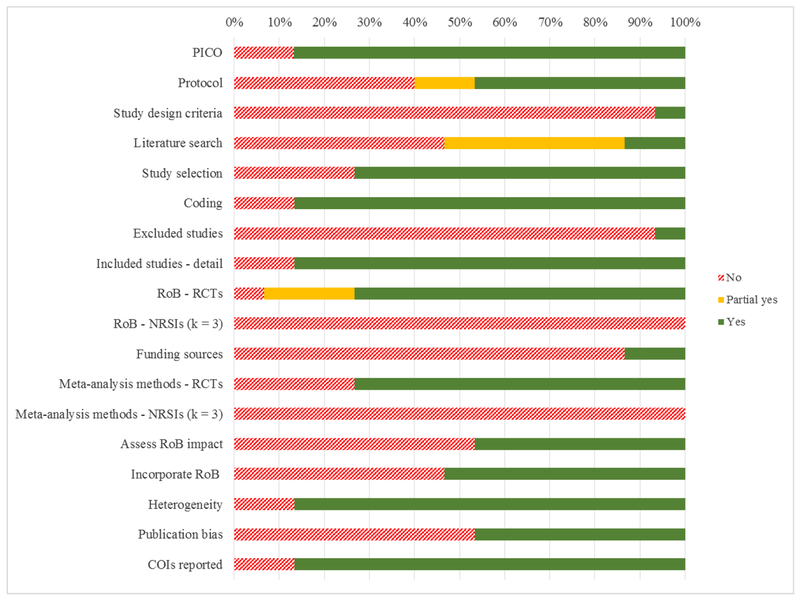

Table 1 lists whether each meta-analysis satisfied, partly satisfied, or failed to satisfy the AMSTAR-2 criteria. Table 2 (Column #2) includes each review’s AMSTAR-2 item completion proportion score. On average, the meta-analyses achieved 56.5% completion of AMSTAR-2 quality dimensions (SD = 0.14), with a range of 31 to 88%. The majority of meta-analyses presented details about the study coding (13/15), provided sufficient details about study inclusion (13/15), tested for risk-of-bias (14/15) and for heterogeneity of effects (13/15), and reported conflicts of interest (13/15). Thirteen of the 15 meta-analyses satisfied the four PICO elements. However, only a little more than half specified the protocol (9/15) or details of the literature search (8/15), approximately one half assessed the impact of risk of bias (7/15) or publication bias (7/15), and only a little more than half incorporated risk of bias (8/15). Depicted in Figure 2, the variability in quality suggests the results from several of the meta-analysis should be considered tentatively.

Table 2.

Outcomes of Cardiovascular Disease Behavioural Intervention Meta-analyses

| Citation | AMSTAR | Population | Author description of BCT (specific application) | Beh. or Health Outcome | Outcome: Subj. or Obj. | k with | ES with BCT [95% CI] or (SE) | k w/o | ES without BCT [95% CI] or (SE) | Q-Between, Z, and/or p-value between groups | Heterogeneity | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-monitoring | ||||||||||||

| Morrissey et al., 2017 | 0.88 | Patients who were prescribed hypertension medication | Home BP Monitoring | SBP | Obj. | NR | NR | NA | Chi2 = .00, df = 1, p = .99, I2 = 0% | No advantage for BCT | ||

| Morrissey et al., 2017 | 0.88 | Patients who were prescribed hypertension medication | Home BP Monitoring | DBP | Obj. | NR | NR | NA | Chi2 = 5.21, df = 1, p = .02, I2 = 80.8% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Tucker et al., 2017 | 0.84 | Patients with hypertension managed via outpatient care | BP self-monitoring | Clinic SBP, 12 months | Obj. | 15 | MD = −3.24 [−4.92, −1.57] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Tucker et al., 2017 | 0.84 | Patients with hypertension managed via outpatient care | BP self-monitoring | Clinic DBP, 12 months | Obj. | 15 | MD = −1.50 [−2.24, −0.75] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | BCT 2.3 self-monitoring of behaviour (short term) | PA and/or diet (≤6 months) | Obj. & subj. | 50 | b=0.398 (0.164, 0.632), p= 0.001, r2= 35.3 | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | BCT 2.3 self-monitoring of behaviour (long term) | PA and/or diet (≥12 months) | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b=0.184 (0.009, 0.360), p= 0.040, r2=30.8 | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour | PA | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b = 0.06 (−0.14, 0.27), p= 0.54 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Prompt self-monitoring of behavioural outcome | PA | Obj. & subj. | 3 | b = 1.44 (0.78, 2.10), p<0.01 (univariable model); b = 1.46 (0.87, 2.05), p<0.01 (multivariable model) | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Mills et al., 2018 | 0.56 | Adult patients with hypertension (average SBP <= 140 mmHg, DBP <= 90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medicine) | Home BP Monitoring: self-monitoring of patient BP and recording of measurements either manually or by automatic electronic transmission; BP readings given to providers | SBP reduction | Obj. | 25 | MD= −2.2 [ −3.5, −1.0] | NA | I2= 0.588; p<0.001 | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Mills et al., 2018 | 0.56 | Adult patients with hypertension (average SBP <= 140 mmHg, DBP <= 90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medicine) | Home BP Monitoring: self-monitoring of patient BP and recording of measurements either manually or by automatic electronic transmission; BP readings given to providers | DBP reduction | Obj. | 25 | MD= −1.5 [−2.0, −1.0] | NA | I2=0.514; p=0.22 | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Fletcher et al., 2015 | 0.53 | Patients with hypertension who were receiving ambulatory or outpatient care | Self-monitoring of blood pressure | Office DPB - 6 months | Obj. | 11 | −2.02 [−2.93, −1.11] | NA | Q= 5.07, p=0.89, T2= 0, I2= 0% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Fletcher et al., 2015 | 0.53 | Patients with hypertension who were receiving ambulatory or outpatient care | Self-monitoring of blood pressure | Office SBP - 6 months | Obj. | 9 | −4.07 [−6.71, −1.43] | NA | Q = 24.29, p = 0.002, T2 = 9.46, I2 = 67% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Fletcher et al., 2015 | 0.53 | Patients with hypertension who were receiving ambulatory or outpatient care | Self-monitoring of blood pressure | MA | Obj. & subj. | 13 | d = 0.21 [0.08, 0.34] | NA | Q= 20.88, p=0.05, T2=0.02, I2 = 43% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Glynn et al., 2010 | 0.53 | Patients with essential hypertension in an ambulatory setting | Self-monitoring of blood pressure management | SBP (mmHg) | * | 12 | WMD = −2.5 [−3.7, −1.3] | NA | Chi2 = 26.79, df = 11 (p = 0.005); I2 =59% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Glynn et al., 2010 | 0.53 | Patients with essential hypertension in an ambulatory setting | Self-monitoring of blood pressure management | DBP (mmHg) | * | 14 | WMD = −1.8 [−2.4,−1.2] | NA | Chi2 = 20.71, df = 13 (p = 0.08); I2 =37% | Sig. diff. with BCT | ||

| Glynn et al., 2010 | 0.53 | Patients with essential hypertension in an ambulatory setting | Self-monitoring of blood pressure management | Blood pressure control | * | 6 | OR = 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] | NA | NS | |||

| Bray et al., 2010 | 0.47 | Nspec. | Self-measurement of BP without medical professional input, if usual care did not include patient self-monitoring | Office target SBP (mmHg) | Obj. | 21 | WMD = −3.82 [−5.61, −2.03] | NA | I2=71.9%, p< 0.001 | Sig. diff. for BCT present | ||

| Bray et al., 2010 | 0.47 | Nspec. | Self-measurement of BP without medical professional input, if usual care did not include patient self-monitoring | Office target DBP (mmHg) | Obj. | 23 | WMD = −1.45 [−1.95, −0.94] | NA | I2= 42.1%, p<0.01 | Sig. diff. for BCT present | ||

| Bray et al., 2010 | 0.47 | Nspec. | Self-measurement of BP without medical professional input, if usual care did not include patient self-monitoring | Mean day-time ambulatory SBP (mmHg) | Obj. | 3 | WMD = −2.04 [−4.35, 0.27] | NA | I2<0.05%, p=0.89 | No advantage for BCT | ||

| Bray et al., 2010 | 0.47 | Nspec. | Self-measurement of BP without medical professional input, if usual care did not include patient self-monitoring | Mean day-time ambulatory DBP (mmHg) | Obj. | 3 | WMD = −0.79 [−2.35, 0.77] | NA | I2<0.05%, p= 0.96 | No advantage for BCT | ||

| Bray et al., 2010 | 0.47 | Nspec. | Self-measurement of BP without medical professional input, if usual care did not include patient self-monitoring | Change in proportion of people with office-measured BP controlled below target between TX and CT | Obj. | 12 | RR = 1.09 [1.02, 1.16) | NA | I2=73.6, p<0.01 | Sig. diff. for BCT present | ||

| Kanejima, Kitamura, & Izawa, 2019 | 0.38 | Patients with CVD’s managed in outpatient care from recovery to maintenance | Self-monitoring intervention | Steps per day | Obj. | 4 | d = 0.97 [0.71, 1.22] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Chase et al., 2016 | 0.33 | Patients with CAD diagnosis | Self-monitoring of medications | MA | Obj. & subj. | 3 | d = 0.492, SE= 0.267 | 25 | d = 0.195, SE= 0.045 | QB= 1.198, p= 0.274 | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups | |

| Goal setting | ||||||||||||

| Samdal et al. (2017) | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | Goal setting (behavior, short term) | PA and healthy eating (≤6 months) | Obj. & subj. | 50 | b=0.480 [0.257, 0.705] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Samdal et al. (2017) | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | Goal setting (behavior, long term) | PA and healthy eating (≥12 months) | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b=0.228 [0.056, 0.400] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Samdal et al. (2017) | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | Goal setting (outcome) | PA and healthy eating | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b=0.256 [0.095, 0.416] | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Goal setting (behavior) | PA | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b = 0.17 [−0.06, 0.40], p= 0.15 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Goodwin et al., 2016 | 0.56 | CHD patients | Goal setting and action planning | Mortality | Obj. | 15 | b = −0.06 [−0.28, 0.15] | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Chase et al., 2016 | 0.33 | Patients with CAD | Nspec | MA | Obj. & subj. | 5 | d = 0.183, SE= 0.135 | 23 | d = 0.227, SE= 0.050 | QB= 0.095, p= 0.758 | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups | |

| Barrier identification/Problem solving | ||||||||||||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight and obese adults | BCT 1.2 Problem solving (long term) | PA and/or diet (≥12 months) | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b = 0.161 [−0.005, 0.327], p = 0.057, r2= 25.1 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Barrier identification/problem solving | PA | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b = 0.04 [−0.16, 0.25], p= 0.67 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Chase et al., 2016 | 0.33 | Patients with CAD | Problem solving | MA | Obj. & subj. | 6 | d= 0.188, SE= 0.08 | 22 | d= 0.245, SE= 0.054 | QB= 0.307, p= 0.580 | No advantage for BCT | |

| Feedback | ||||||||||||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight or obese adults | Feedback on behavior | PA | Obj. & subj. | 50 | b= 0.219 [−0.040, 0.479] | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight or obese adults | Feedback on outcome (short term) | PA (≤6 months) | Obj. & subj. | 50 | b=0.243 [0.040, 0.527) | NA | Sig. diff. with BCT | |||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight or obese adults | Feedback on outcome (long term) | PA (≥12 months) | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b=0.249 [0.085, 0.412] | NA | Sig. diff with BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Provide feedback on performance | PA | Obj. & subj. | 27 | b = −0.04 [−0.24, 0.16], p= 0.71 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Goodwin et al, 2016 | 0.56 | CHD patients | Providing feedback | Mortality | Obj. | NR | b = −0.03 [−0.20, 0.15] | NA | I2=−0.03% | No advantage for BCT | ||

| Yue et al., 2019 | 0.44 | Clinical diagnosis of hypertension, with or without adequate BP control | Automated feedback generated by system without HCP and individualized goal-directed feedback by HCP | SBP | Obj. & subj. | 14 | MD = −5.29 95% CI [−8.63, −1.95] | NA | T2=38.64; Chi2=309.71; p<0.00001, I2=95% | Sig. diff with BCT | ||

| Yue et al., 2019 | 0.44 | Clinical diagnosis of hypertension, with or without adequate BP control | Automated feedback generated by system without HCP and individualized goal-directed feedback by HCP | DBP | Obj. & subj. | 14 | MD= −3.00 95% CI [−5.97, −0.04] | NA | T2=32.07; Chi2=742.84; p<0.00001, I2=98% | Sig. diff with BCT | ||

| Goal review | ||||||||||||

| Samdal et al., 2017 | 0.78 | Overweight or obese adults | BCT 1.5 review behavioural goals (long term) | PA (≥12 months) | Obj. & subj. | 32 | b= −0.319 [−0.678, 0.040], p= 0.078, r2= 19.8 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Prompt review of behavioural goals | PA | Obj. & subj. | 10 | b = −0.13 [−0.37, 0.11], p= 0.29 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Goodwin et al., 2016 | 0.56 | CHD patients | Review of goals/self-monitoring | Mortality | Obj. | 15 | RR = −0.07 [−0.25, 0.11] | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Relapse prevention/Coping planning | ||||||||||||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Relapse prevention/coping planning | PA | Obj. & subj. | 11 | b = −0.14 [−0.39, 0.11], p= 0.28 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Action planning | ||||||||||||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Action planning | PA | Obj. & subj. | 11 | b = −0.15 [−0.36, 0.07], p= 0.18 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Stress management | ||||||||||||

| Goodwin et al., 2016 | 0.56 | CHD Patients | Stress management | Mortality | Obj. | 22 | b = 0.08 [−0.13, 0.30] | NA | NA | No advantage for BCT | ||

| Time management | ||||||||||||

| Murray et al., 2017 | 0.64 | Adults (ages 18–64) | Time management | PA | Obj. & subj. | 2 | b = 0.08 [−0.68, 0.85], p= 0.82 | NA | No advantage for BCT | |||

| Self-Management | ||||||||||||

| Parry et al., 2018 | 0.56 | Adult women >=18 with CAD and cardiac pain | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Individual follow up, on cardiac pain proportion at 6 months | Subj. | 5 | RD = −0.09 [−0.14, −0.04], P < 0.001 | NA | p = 0.39; I2 = 3%, T2= 0 | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Parry et al., 2018 | 0.56 | Adult women >=18 with CAD and cardiac pain | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Non-obstructive CAD on cardiac pain frequency at 3 months | Subj. | 4 | d = −0.76 [−1.11, −0.40], p < 0.001 | NA | p = 0.09; I2= 53%, T2=0.07 | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Parry et al., 2018 | 0.56 | Adult women >=18 with CAD and cardiac pain | Self-management interventions – Multiphased | Individual follow up, on cardiac pain frequency at 6 months | Subj. | 10 | d = −0.29 [−0.46, −0.12], p < 0.001 | NA | p = 0.98; I2 = 0%, T2=0 | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | PA | Obj. & subj. | 7 | d = 0.08 [−0.08, 0.25] | NA | Chi2 = 4.82, df = 6, (p = 0.57), I2 = 0% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Diet and nutrition | Obj. & subj. | 5 | d = 0.14 [−0.08, 0.36] | NA | Chi2 = 4.09, df = 4 (p = 0.39), I2 = 2% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Smoking | Subj. | 5 | d = 0.20 [−0.18, 0.58] | NA | Chi2= 4.60, df = 4, (p = 0.33), I2 = 13% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Alcohol consumption | Subj. | 3 | d = 0.12 [−0.37, 0.61] | NA | Chi2= 1.28, df =2, (p = 0.53), I2= 0% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Medication adherence | Obj. & subj. | 5 | d = 0.31 [0.07, 0.56] | NA | Chi2 = 5.25, df = 4, (p = 0.26), I2 = 24% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Sakakibara et al., 2017 | 0.31 | Adults >=18 who have had a stroke or TIA | Self-management interventions - Multiphased | Cholesterol | Obj. | 5 | d = −0.06 [−0.24, 0.12] | NA | Chi2 = 1.21, df = 4, (p = 0.88), I2 = 0% | Sig. diff. of intervention | ||

| Self-Regulation Techniques High vs. Low | ||||||||||||

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Smoking (Post-TX) | * | 9 | OR = 1.33 | 6 | OR = 1.17 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Exercise (Post-TX) | * | 8 | g = 0.60 | 6 | g = 0.17 | p<0.05 | NR | Sig. diff. for BCT present |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Fat intake (Post-TX) | * | 8 | g = 0.46 | 5 | g = 0.14 | p<0.05 | NR | Sig. diff. for BCT present |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Energy intake (Post-TX) | * | 5 | g = 0.38 | 3 | g = 0.11 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Smoking (follow-up) | * | 6 | OR = 1.50 | 2 | OR = 1.04 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Exercise (follow-up) | * | 5 | g = 0.19 | 2 | g = 0.09 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Fat intake (follow-up) | * | 5 | g = 0.21 | 3 | g = 0.16 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

| Janssen et al., 2013 | 0.66 | CHD patients | Sr techniques high vs. low | Energy intake (follow-up) | * | 3 | g = 0.14 | 2 | g = 0.13 | NS | NR | NS diff. between BCT and non-BCT groups |

Notes. AMSTAR = A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews. Beh. = Behavioural. BCT = behaviour change technique. BP = blood pressure. CAD = Coronary Artery Disease. CHD = Coronary Heart Disease. CT = Control. CVD = Cardiovascular Disease. DBP = Diastolic blood pressure. Diff. = Difference. ES = Effect size. g = Hedges’ effect size. HCP = Health care professional. k with = Number of studies including the BCT. k w/o = Number of studies without the BCT. MA = Medication adherence. MD = Mean difference. NA = Not applicable. NR = Not reported. NS = Non-significant. Nspec = Not specified. Obj.= Objective measure. OR = Odds ratio. PA = Physical activity. RD = Risk difference. RR = Risk ratio. SBP = Systolic blood pressure. SE = Standard error. Sig. = Significant. Sr = self-regulation. Subj. = Subjective measure. TX = Treatment. WMD = Weighted mean difference.

= No information provided whether the outcome was measured objectively and/or subjectively.

Figure 2.

Quality Assessment Results according to AMSTAR 2 ratings

Represents satisfaction of 16 criteria across 15 meta-analyses (two of the original criteria were split to distinguish between reviews that included only RCTs and those including RCTs and NRSIs). The figure displays the proportion of Yes’, Partial Yes’, and No’s satisfying criteria for all meta-analyses. Coding of subsets of items that supported a “Yes/Partial Yes/No” distinction for each review is found in Supplement 2. COIs = Conflicts of interest. k= Number of reviews. NRSIs = Nonrandomised studies of healthcare interventions. PICO = Population, intervention, control group, outcome. RCTs = Randomised controlled trials. RoB = Risk of bias.

Self-Regulation and BCT Coverage

None of the 15 CVD meta-analyses reported about underlying self-regulation MoA’s. So, not knowing the links between self-regulatory mechanisms and changes in CVD-relevant health behaviours limits knowledge about to improve health behaviours and outcomes that may effectively prevent or manage this serious health condition. Of the 15 reviews, only four formally an established system for classifying BCTs. Samdal, Eide, Barth, Williams, and Meland (2017) used the Behaviour Change taxonomy (BCTTv1) (Michie et al, 2013); Goodwin et al., (2016) and Murray, Brennan, French, Patterson, Kee and Hunter (2017) used the CALO-RE taxonomy (Michie, Ashford, Sniehotta, Dombrowski, Bishop, & French, 2011); and Janssen, Gucht, Dusseldorp, & Maes (2013) adapted elements from Linden, Stossel, and Maurice (1996) and Mullen, Mains, and Velez (1992). The other 11 reviews did not use and/or reference any of the established behavioural intervention taxonomies, but they provided a description of the particular intervention technique that matches a technique in the taxonomy. Four reviews restricted their attention to self-monitoring, which reduced the need for a taxonomy.

Most meta-analyses used post-hoc tests to compare the presence and effects of specific BCTs in multi-component intervention trials. Figure 3 is a 3D heatmap depicting the number of BCTs that were assessed in each review and the AMSTAR-2 composite quality score for each review, indicated by color-coding (ranging from green representing the highest scores [0.78 to 0.88] and red the lowest scores [0.31–0.33]). (See the online supplemental materials for the raw data and variable labels for CVD.)

Figure 3.

3-D heatmap depicting the BCTs (X-axis) assessed in each of the fifteen meta-analyses (Y-axis) and the number of studies contributing to each BCT analysis (Z-axis)

Color (i.e., red, orange, yellow, light green, green) indicates AMSTAR quality; red through green represent from lower- to higher-quality meta-analyses. For reviews including multiple health outcomes for the same intervention component, the analysis with the greatest number of studies was selected for this figure. For the analyses conducted on self-monitoring and feedback by Morrissey et al. (2017) and Goodwin et al. (2016), the eligible number of studies is depicted on the Z-axis because the number of studies included in testing specific BCTs analysis was unavailable. Sr= Self-Regulation.

Across the 15 reviews, nine out of the 11 targeted BCTs were tested, but representation was highly uneven (see Figure 3). Ten meta-analyses covered self-monitoring; four covered goal setting and feedback; and three included barrier identification/problem-solving and goal review. Relapse/prevention, action planning, stress management, and time management appeared rarely (each in only one meta-analysis). Emotional control and self-talk did not appear in any of the CVD reviews. Three of the 15 meta-analyses adopted somewhat distinctive approaches. Both Parry et al (2018) and Sakakibara, Kim, and Eng (2017) evaluated “self-management” interventions that included some BCTs along with other elements, but the reviews did not assess the effects of specific BCTs. A third self-management review coded only four BCTs (Janssen, Gucht, Dusseldorp, & Maes, 2013) and categorized each intervention as “high” versus “low” in self-regulation techniques based on the proportion of the four included in each primary study’s intervention. “High vs. low” served as a dichotomous variable to calculate associations with health behaviours and health outcomes. The outcomes of these three somewhat unique meta-analyses will be presented in a separate section.

Lifestyle Behaviours and Health Outcomes

Interventions included several lifestyle behaviour and health outcomes relevant to primary or secondary CVD risk: PA, dietary control (or fat or energy intake), medication adherence (mainly to anti-hypertensive medication), systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP), fitness level (i.e., ability to withstand a physical workload and to recover in a timely manner), body weight, smoking, and all-cause mortality 2 (see Table 2, column 5). Some CVD-relevant health behaviours and outcomes received little to no coverage (e.g., limiting sodium intake, statins for CVD management) in this literature.

Target Self-Regulation via Tests of Intervention Components

Reviews commonly used meta-regression or multivariate meta-regression to statistically test the associations of specific BCTs with health behaviours or outcomes. In the majority of cases, these involved post-hoc tests. Depending on the metric and the analysis of each review, effect sizes took the form of odds ratios, standardised mean differences, or regression coefficients (Table 2; for the raw data see the Data File in the online supplementary materials). Table 2 presents the effect size, number of studies (k) contributing to the effect size in the condition with the BCT, number of studies (k w/o) contributing to the effect size in the condition without the BCT and the test of heterogeneity (i.e., degree to which the effect applied to all the relevant studies). The outcomes reported below and in Table 2 correspond to the metric reported in the original 15 meta-analyses. In the next sections, the primary BCT results from the meta-analysis with the highest AMSTAR (quality) completion score are presented first and then moves to the next-lower ranked and so on. This approach was used more to provide a rationale for the presentation order than to highlight the relative quality of the reviews.

Self-monitoring.

Morrisey, Durand, Nieuwlaat, Navarro, Brian-Haynes, Walsh & Molloy (2017) pooled results for patients prescribed medication for hypertension instructed to monitor their BP at home versus usual care/minimal education. The authors reported self-monitoring was significantly associated with lower DBP (although results varied considerably according to the heterogeneity test), but not with SBP. (Statistical values were not included, however.) (See Table 2.)

Out of all 15 meta-analyses, only Tucker et al (2017) pooled individual patient data, a procedure considered to be more powerful than the conventional practice to pool data at the study level (Tudur Smith et al, 2016). In a set of 15 primary studies with hypertensive outpatients, self-monitoring (vs. usual care) reduced SBP (MD = −3.24, 95% CI [−4.9, −3.2]) and DBP (MD = −1.50, 95% CI [−2.4, −0.60]) at 12 months. Reductions in blood pressure appeared, however, to depend on self-monitoring being combined with self-management, systematic medication titration, or lifestyle counselling.

Samdal, Eide, Barth, Williams, and Meland (2017) identified RCTs for overweight and obese participants that included a variety of behaviour and/or cognitive techniques to increase PA activity and healthy eating versus usual care, waiting list control, or less intensive interventions. The lifestyle interventions produced short-term (6 months or less) and long-term (12 months or more) benefits on both subjective and objective measures of PA and/or diet. In meta-regressions, self-monitoring seemed to significantly improve short-term (b = 0.39, p < .001) and long-term (b = 0.184, p < .04) PA and diet and accounted for a moderate amount of variability (r2 = 35.3 and r2 = 30.8, respectively).

Murray et al (2017) reported on studies testing the long-term effects (>6 months) of multicomponent behavioural interventions on validated PA measures in nonclinical samples of adults 18–64 years of age. Meta-regression using coding with the BCTTv1 (Michie et al, 2013) and the CALO-RE taxonomy (Michie et al, 2011) identified self-monitoring of behavioural outcomes as a facilitator of PA (b = 1.46, p <0.01).

Moving to analyses that had 56% or lower AMSTAR quality completion, Mills et al (2018) assessed the efficacy of self-monitoring (and multi-level, multi-component implementation strategies,) versus usual care/minimal education to reduce SBP and DBP levels in RCT trials lasting at least 6 months. Self-monitoring alone was associated with reductions in SBP (MD = −2.2, 95% CI −3.5, −1.0) and DBP levels (MD = −1.5, 95% CI −.2.0, −1.0).

In interventions possibly also including telemedicine and physician education, Fletcher et al. (2015) assessed the effects of self-monitoring on adult antihypertensive medication adherence (MA), blood pressure, PA, and dietary outcomes (see Table 2). Level of adherence relied on electronic medication monitoring system data, pharmacy fill data, pill counts, or self-report. Pooled analysis of all adherence measures (2 weeks to 12 months) yielded a small but significant overall effect in favour of self-monitoring (0.21, 95% CI 0.08, 0.34). Objective measures of adherence (especially electronic monitoring) versus self-report showed larger effect sizes. Self-monitoring appeared to lower DBP (−2.02, 95% CI −2.93, −1.11) and SBP at 6 months (−4.07, 95% CI −6.71, −1.43). The high variability among SBP outcomes (Q = 24.29, p = .002, τ2 = 9.46, I2 = 67%), however, suggests self-monitoring may not be helpful for all patients with hypertension. A subset of studies assessed dietary and PA outcomes, but self-monitoring seemed to have no effects.

Glynn et al. (2010) also reviewed the effects of self-monitoring on BP control in community-residing adults with hypertension; several of the RCTs also included education and appointment reminders. Both SBP (−2.5 mmHg, 95% CI [−1.3, −3.7]) and DBP (−1.8 mmHg, 95% CI [−2.4, −1.2 mmHg]) declined after instruction about self-monitoring. The substantial heterogeneity associated with the SBP and DBP results (SBP: X = 26.79, p = .005, I2 = 59%; DBP: X = 20.71, p = .08, I2 = 37%), however, suggests that the association with self-monitoring may not generalize to certain populations with hypertension. A subset of studies that used clinic definitions of BP control showed no evidence of improvement associated with self-monitoring (OR = 1.0, 95% CI [0.8, 1.2]). The timing for collection of the BP outcomes was not provided.

In studies of adults with hypertension from different sources (e.g., primary care, community screenings), Bray et al. (2010) assessed the role of self-monitoring (interventions also included education, nurse-led support, etc.) versus usual care on several outcomes: office and ambulatory SBP and DBP levels, as well as the proportion of patients meeting office target pressures. Self-monitoring was associated with a significant SBP reduction of −3.82 mmHg, 95% CI [−5.61, −2.03] and DBP reduction of −1.45 mmHg, 95% CI [−1.95, −0.94]. A greater proportion of patients who self-monitored had their BP under control (a risk ratio of 1.09, 95% CI [1.02, 1.16]) than patients assigned to usual care. Length of follow-up ranged from 0 to 36 months with 6 months being the most common. Office pressures had appreciable heterogeneity, but variability declined, and more patients met the BP clinic target when another co-intervention accompanied self-monitoring.

Kanejima, Kitamura, and Izawa (2019) identified interventions conducted to improve PA in patients with a history of angina or myocardial infarction who experienced heart failure and had a cardiovascular surgery. Study inclusion required pedometers or accelerometers, and patients had to report steps and energy expenditure. Of the six studies that qualified, only four reported sufficient information, but their pooled data indicated self-monitoring had benefits (d = 0.97, 95% CI 0.71, 1.22). None of the interventions implemented self-monitoring alone, however, and the review indicated no attempt to identify the independent role of self-monitoring. Although the review had methodological limitations, its conclusions about the BP benefits of self-monitoring concurred with several earlier reviews.

Chase, Bogener, Ruppar, & Conn (2016) evaluated studies of medical adherence interventions, including self-monitoring, with CAD patients. Self-monitoring was not significantly associated with improved adherence (QB = 1.198, p = .274). This meta-analysis had a very low AMSTAR completion score.

In summary, although quality varied substantially across the meta-analyses (0.88 to 0.33), self-monitoring had significant benefits on BP, diet, PA, and medication adherence in most of them. Interpretation should be cautious, however, because several studies tested the effects of self-monitoring on BP control—the one domain with the most primary study overlap across reviews.

Goal setting.

Of the four relevant meta-analyses that assessed goal setting (see Table 2), only Samdal et al. (2017) found increases in PA and healthy diet (both at ≤ 6 months [b = 0.480, p < .001] and at ≥ 12 months [b = 0.228, p < .04]) in overweight and obese adults. Goal setting accounted for a larger amount of heterogeneity in these improvements than did self-monitoring (r2 = 49.2 and r2 = 38.5, respectively). Goal setting also had an effect on one health outcome, lower total saturated fat (b = 0.256, p < .003).

Murray et al.’s (2017) meta-analysis of behavioural interventions on the long-term effects (>6 months) on PA in community adult samples tested the role of goal setting (coded with BCTTv1 [Michie et al., 2013] and the CALO-RE [Michie et al., 2011]). Goal setting provided no apparent improvement.

Goodwin et al.’s review of behavioural change interventions versus usual care for patients with coronary artery disease found no evidence that goal setting/action planning reduced mortality risk. A review by Chase et al. (2016) also focusing on cardiac patients, identified multi-component behavioural interventions, which included education, reminders, special packaging, and self-monitoring, feedback, etc., on medication adherence. Although there was an intervention effect (d = 0.18, SE = 0.14), goal setting demonstrated no additional benefits than interventions without goal setting (QB = 0.095, p = .758).

Goal setting has received much less attention than self-monitoring in the CVD context and fewer kinds of prevention/management behaviours/outcomes have been assessed. The lower quality reviews showed no benefits of goal setting.

Problem-solving/barrier identification.

Only three meta-analyses examined problem-solving (in combination with barrier identification in one review) as a BCT (see Table 2). Samdal et al., (2017) reported no improvements in long-term PA or diet (b = 1.61, p < .057) associated with problem-solving for overweight/obese adults. Murray et al (2017) found no effect on PA in community residing adults, and Chase et al. (2016) found no effect on medication adherence in cardiac patients (d = .19, SE = .05). In brief, problem-solving had no demonstrable benefit for improving CVD prevention and management.

Feedback.

Samdal et al. (2017) reported associations between feedback and short- (b = 0.243, p < .09) and long-term (b = 0.249, p < .004) PA improvements. Feedback’s association with long-term improvement in PA showed weaker effects than self-monitoring or goal setting (r2 = 12 and r2 = 43.8, respectively).

Murray et al.’s (2017) review of multi-component interventions for increasing PA in adults assessed benefits of feedback, but it conferred no benefits (b = −.04, 95% CI −.24, −0.16). Goodwin et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis of studies with cardiac patients also found that feedback had no benefit for all-cause mortality (b = .03, 95% CI −.0.20, −0.16). Yue et al. (2019) considered only studies that used e-health technologies (e.g., internet, mobile health applications) providing automated and health care provider feedback (e.g., BP values and monitoring frequency, medication adherence) to improve BP control in hypertensive patients. Both SBP (MD = −5.59, 95% CI −8.63, −1.95) and DBP (MD = −3.00, 95% CI −5.97, −0.04) declined with receipt of feedback, but effects had high heterogeneity. Also, Yue et al (2019) had the lowest AMSTAR completion score of the four reviews reporting the feedback component.

Reviewing goals.

Three eligible CVD meta-analyses assessed the effects of reviewing goals (see Table 2). Samdal et al. (2017) found no effect of goal review on PA or diet in the long-term (b = −0.319, 95% CI [−0.678, 0.040], p = .078, r2 = 19.8) in obese or overweight participants. Similarly, Murray et al.’s (2017) review of studies including goal review as part of the interventions reported no benefits for young to older adults (b = −.013, 95% CI −0.37, 0.11). The third review (Goodwin et al., 2016) reported on interventions with cardiac patients that included review of goals in combination with self-monitoring. All-cause mortality (b = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.28, 0.15]) did not decline with the addition of goal review. In sum, goal review remains unpromising, at least with respect to CVD prevention and management.

Relapse prevention/Coping planning.

Only Murray et al.’s (2017) review considered this BCT. Relapse prevention/coping planning failed to confer any improvement in PA as part of multi-component interventions in community-residing youth to older adults (b = −.014, 95% CI −0.39, 0.11).

Action planning.

The only meta-analysis to review the effects of action planning was by Murray et al. (2017). No improvements in PA obtained with inclusion of action planning in multi-component interventions (b = −0.15, 95% CI −0.36, 0.11).

Stress management.

Goodwin et al. (2016) reviewed analyses of interventions, including stress management, with cardiac patients. Providing stress management skills did not reduce the risk of all-cause mortality (b = 0.08, 95% CI −0.13, 0.30).

Time management.

A single meta-analysis (Murray et al, 2017) assessed the role of time management as part of multi-component behavioural interventions to increase PA. No benefits accrued among young to older adult populations (b = 0.08, 95% CI −.68, 0.85).

Self-management interventions.

Two meta-analyses identified and evaluated the efficacy of multiple component interventions, which the authors deemed to promote “self-management” that they defined as “…patients actively [participating] in their own care and treatment” (p. 459; Parry et al., 2018) (see Table 2). In a search for studies of women who had CAD and experienced cardiac pain, Parry et al. (2018) identified several techniques such as goal setting, self-monitoring and planning, along with other components (e.g., education about condition-specific knowledge). The self-management interventions were associated with lower cardiac pain, but no specific “self-regulatory” BCTs seemed to be effective alone (see Table 2).

Sakakibara et al. (2017) reviewed intervention studies with adult stroke patients to reduce their risk factors/behaviours. To be eligible, any intervention had to provide at least one self-management/skill technique (e.g., goal setting, self-monitoring), but the review did not conduct analyses to identify the effects of specific techniques. Pooled data showed self-management interventions improved medical adherence immediately after treatment (d = 0.31 95% CI 0.07, 0.56) but no benefits were found for other behaviours or outcomes (e.g., across risk factors, smoking, diet/nutrition/cholesterol) (p’s > .05).

These two reviews were described for the sake of completeness, but because BCTs were tested in aggregate, the reviews could not identify which specific strategies had efficacy. Also, to place these reviews in context, Parry et al.’s (2018) AMSTAR completion score fell in the middle of the “pack”, while Sakakibara et al. (2017) ranked the lowest of the 15.

Interventions that were high versus low in self-regulatory components.

A meta-analysis on studies with cardiac patients (Janssen et al., 2013) (see Table 2) retrieved studies of behavioural interventions and coded them for the presence of four BCTs: goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and planning. Instead of pooling study data for each BCT and testing their separate effects—the typical strategy used in the majority of meta-analyses—Janssen et al. (2013) summed how many of the four BCTs were included in each study to classify interventions as “high” versus “low” in self-regulatory BCTs and then entered High/Low as a categorical predictor. For interventions including more of the four BCTs (i.e., high), exercise increased (g = 0.60) and fat intake decreased (g = 0.46). No effects emerged for smoking or lower energy intake (see Table 2). Although this review’s quality was ranked on the higher end of the continuum (.66), no single technique or combination of techniques could be unambiguously credited for the benefits because BCT’s effects were tested as a group.

Discussion

Fifteen meta-analyses meeting inclusion criteria tested several behavioural techniques postulated to relate to self-regulation (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Bandura, 2004; Carver & Scheier, 1982; Michie & Johnston, 2012). The reviews ranged widely in quality according to AMSTAR-2 scoring; only three satisfied 70 to 88% of the quality criteria. Of 11 BCTs proposed to improve self-regulation, nine were the subject of at least one meta-analysis. Most BCTs, however, appeared in four reviews or less, and two BCTs received no consideration in any meta-analysis. Whether these gaps result from investigators’ beliefs that certain BCTs have limited value for CVD prevention and management, or the BCTs are perceived to be difficult to test or implement remains unclear. Identifying why these gaps exist and what strategies can eliminate them merits empirical attention. A “null finding,” but substantive in its implications, is that none of the meta-analyses included studies testing whether self-regulation changed as a result of behavioural intervention. In short, CVD researchers appear to not be assessing how a successful intervention changes behaviour (i.e., the MoA). Even if a technique produces beneficial outcomes, researchers and practitioners remain in a state of ignorance about “why.”

Self-monitoring was the most frequently studied BCT (i.e., 10 reviews), sometimes as the sole component or as part of a multi-component intervention. This behavioural strategy provided modest but statistically significant benefits for hypertension control, medication adherence, PA, and diet in nine out of 10 meta-analyses. Some reviews, however suggested self-monitoring may need the support of other components to be successful (Kanejima et al, 2019; Tucker et al, 2017). Despite the apparent efficacy of self-monitoring, the heterogeneity of effects calls for more investigation of different combinations of populations and interventions to determine for whom self-monitoring is most successful. Furthermore, several meta-analyses reviewed some of the same primary studies (for BP control), potentially inflating the estimate of self-monitoring’s efficacy.

Four meta-analyses assessing feedback found it provided some benefits for overweight and obese adults and adults with hypertension. The remaining BCTs (e.g., goal setting, goal review, action planning) were not well represented in the meta-analyses and few benefits emerged. Two distinctive meta-analyses (Parry et al, 2018; Sakakibara et al., 2017) reviewed multi-component “self-management” trials that included some BCTs, such as self-monitoring and goal review. Health behaviour and health outcomes appeared to improve (especially in Parry et al, 2018). A third article, using a different analytic approach, found benefits for interventions including more “self-regulatory” BCTs (Janssen et al., 2013). These three unique reviews, however, did not perform statistical tests to identify BCT-specific associations. Thus, it is clear that the interventions produced significant effects, but the exact mechanism is unclear.

Methodological Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

Most meta-analyses satisfied the following items on the AMSTAR-2 (Shea et al., 2007): PICO inclusion criteria, provided information about screening and coding, used appropriate meta-analytic methods for RCTs, and tested for heterogeneity. But only about half fully described the literature search, assessed the impact or corrected for risk of bias, or examined publication bias. Describing study-design criteria for eligibility or the basis for excluding studies were also rare. These limitations suggest that even the positive outcomes reported above warrant cautious interpretation.

No evidence emerged about BCTs for emotional control, inhibitory control, and self-talk, which figure prominently in some health behaviour change theories (Nielsen et al, 2018). Testing a wider array of BCTs in the CVD prevention and management domain is recommended. Associations between BCTs and some CVD-related health behaviours, such as sodium intake, substance use, and cardiac rehabilitation attendance, also remain understudied. With respect to health outcomes, cardiac events and cardiac mortality are rarely linked in the chain of evidence to the health behaviour change.

BCTs have been typically bundled in multi-component interventions, so assessing the contributions of specific techniques has been primarily post-hoc. In our meta-analytic sample, the effects of specific BCTs frequently could only be inferred from post-hoc, statistical tests adjusting for the other factors and other BCTs. Primary studies testing an intervention comprised of a single BCT would yield better evidence to infer cause-effect. Such a strategy is potentially more informative, but clinicians may be understandably reluctant to intervene with a single putative BCT. Despite this reluctance, testing single component interventions may represent an earlier intervention development stage (Rounsaville et al., 2006) that is needed in a rigorous and efficient program of research to guide the eventual selection of BCTs to be bundled together to produce maximum benefit in future clinical trials.

A related alternative may be the adoption of the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST), an engineering-inspired framework for optimising and evaluating multicomponent behavioural interventions. This approach uses a factorial design to simultaneously test multiple individual components using fewer resources than if one were to sequentially test combinations of components (Collins, Dziak, & Li, 2009). MOST methodology is grounded on two engineering principles: continuous optimization and resource management (Collins, Murphy, & Strecher, 2007). Continuous optimization refers to the process of developing highly potent, optimized interventions by iteratively testing individual intervention components. Resource management refers to the process of making design choices that consume the fewest resources during testing and implementation. Similar to conventional multi-component RCTs, promising components are selected after careful review of the literature and consideration of theory and clinical experience; however, in the MOST approach, rather than test multiple components as a package, one first decides which ones to include based on empirical data from randomized experiments. Only those components found to be effective in these experiments are retained for future inclusion in multicomponent interventions; those that are least effective are discarded. The use of the two engineering principles guide the constant evaluation of the most useful behavior change components to initially test, then refine, and decide to retain in any behavior change intervention (see Collins, Nahum-Shani, & Almirall, 2014).

We encourage more individual patient meta-analyses like Tucker et al.’s (2017), which pooled individual patient data across primary studies. As data sharing and more advanced statistical approaches (e.g., multi-level analysis) (Diez-Roux, 2000) become common practices, finer-grained analyses will be possible. Furthermore, intensive data capture of (daily) health behaviours and physiologic outcomes, made possible with advances in technology and measurement (Hedeker, Mermelstein, Berbaum, & Campbell, 2009; Smyth et al, 2018), offer greater precision about the effects of individual BCTs as they are introduced in cardiovascular prevention and management trials.

Two decades ago, Dusseldorp, van Elderen, Maes, Meulman, and Kraaij (1999) published a meta-analysis of studies testing the efficacy of interventions for CVD prevention and management, and made this sobering observation:

In general, the studies included in this meta-analysis did not shed sufficient light on effective mechanisms or components of cardiac rehabilitation programmes. In most studies, programmes are described only vaguely, without explicit reference to a theoretical model or to empirical findings supportive of specific causal relationships between a given strategy or intervention and positive effects on outcome or intermediate indicators of success. (p. 533)

We have to conclude that progress since 1999 seems modest. A contributing factor has been the continuing practice of testing multicomponent behavioural interventions in aggregate. Contemporary researchers, however, have advanced the basic science of self-regulation (Nielsen et al, 2018) and can achieve greater precision with which to identify and classify the MoA’s and BCTs (Michie et al, 2013) they are testing. They can also use more sophisticated design and statistical tools (Collins, Nahum-Shani, & Almirall, 2014). These advances afford the opportunity to learn what works to improve CVD behaviour prevention and management—and why. We hope a future meta-review on this topic will look quite different and be more sanguine about the prospects for health behaviour change.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 1. PubMed search terms

Supplement 2. Coding Form for meta-analysis

Supplement 3. Data File: Descriptive and inferential statistics extracted from seven CVD meta-analyses across seven BCTs

Supplement 4. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Science of Behavior Change Common Fund Program through an award administered by the National Institute on Aging (U24AG052175). The authors acknowledge Jennifer Holmes, ELS, for copy editing.

Footnotes

Michie et al (2013) instructed 18 experts to “…group together (93) BCTs which have similar active ingredients, i.e. by the mechanism of change” (p. 85). Hierarchical clustering analysis found a 16-cluster solution was the best fit with a Dunn index value of .57 (see Table 5, pp 92–93). BCT clusters #8, 9, 14, and 16 included these 11 strategies.

The health outcome, all-cause mortality, is quite different from the vast majority of health outcomes (e.g., BP; increased fitness; improved medical adherence) described in this meta-review, but it was included in the Goodwin et al. (2016) meta-analysis. We reported results for all-cause mortality in the interest of comprehensiveness.

Contributor Information

Jerry Suls, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Northwell Health.

Jazmin N. Mogavero, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Northwell Health

Louise Falzon, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Northwell Health.

Linda S. Pescatello, University of Connecticut

Emily A. Hennessy, University of Connecticut

Karina W. Davidson, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Northwell Health

References

- Abraham C, & Michie S (2008). A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, & Conner M (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behavior: a meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(Pt 4): 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GL, Conn LA, & Pinner RW (1999). Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281(1), 61–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education and Behavior, 31(2), 143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP,…American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. (2019). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 139(10), e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, …American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. (2018). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 137(12), e67–e492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EP, Holder R, Mant J, & McManus RJ (2010). Does self-monitoring reduce blood pressure? Meta-analysis with meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Medicine, 42(5), 371–386. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.489567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & Scheier MF (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111–135. 10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase JAD, Bogener JL, Ruppar TM, & Conn VS (2016). The effectiveness of medication adherence interventions among patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 31(4), 357–366. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]