Abstract

This review describes the additions of allylmagnesium reagents to carbonyl compounds and to imines, focusing on the differences in reactivity between allylmagnesium halides and other Grignard reagents. In many cases, allylmagnesium reagents either react with low stereoselectivity when other Grignard reagents react with high selectivity, or allylmagnesium reagents react with the opposite stereoselectivity. This review collects hundreds of examples, discusses the origins of stereoselectivities or the lack of stereoselectivity, and evaluates why selectivity may not occur and when it will likely occur.

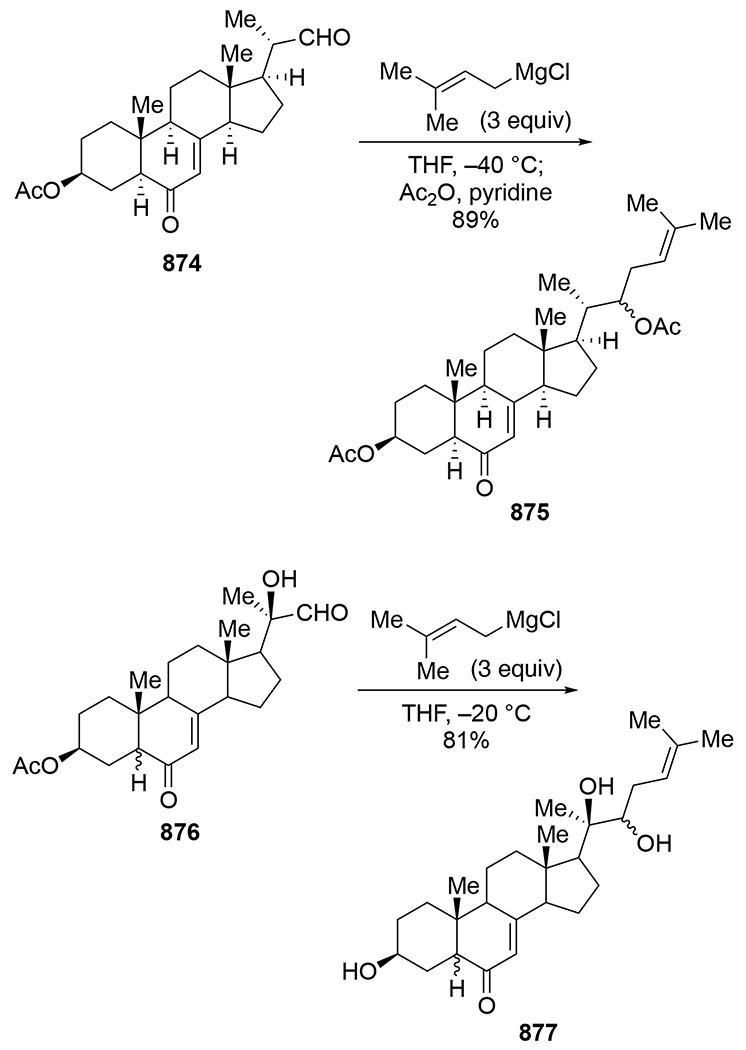

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Allylmagnesium Reagents Exhibit Unique Reactivities

The additions of allylic nucleophiles to carbonyl compounds are powerful transformations because they form synthetically useful homoallylic alcohols. Although allylmetal reagents containing zinc, cerium, boron, titanium, and tin groups can be used in many instances,1 synthetic strategies often depend upon commercially available allylmagnesium reagents to introduce the synthetically useful allyl group (Scheme 1).2

Scheme 1.

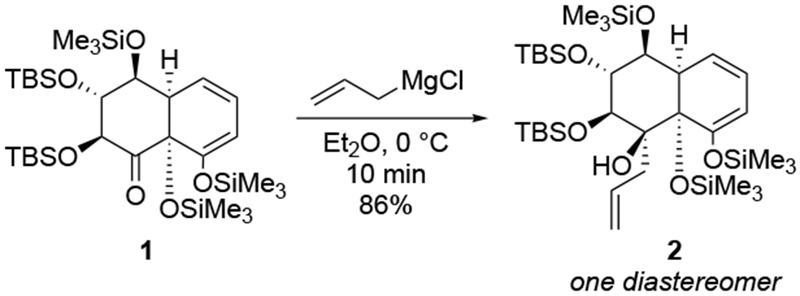

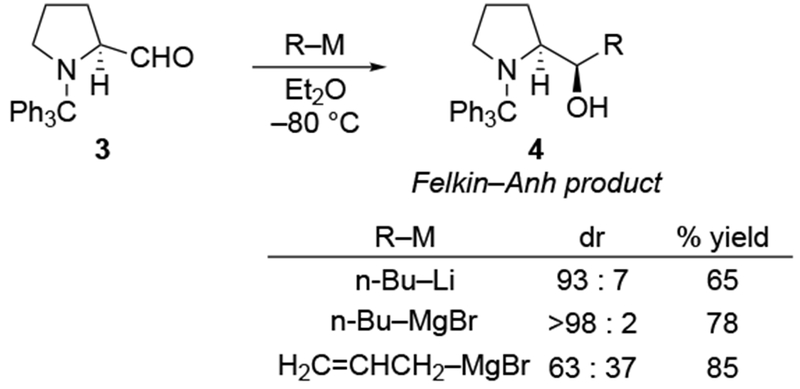

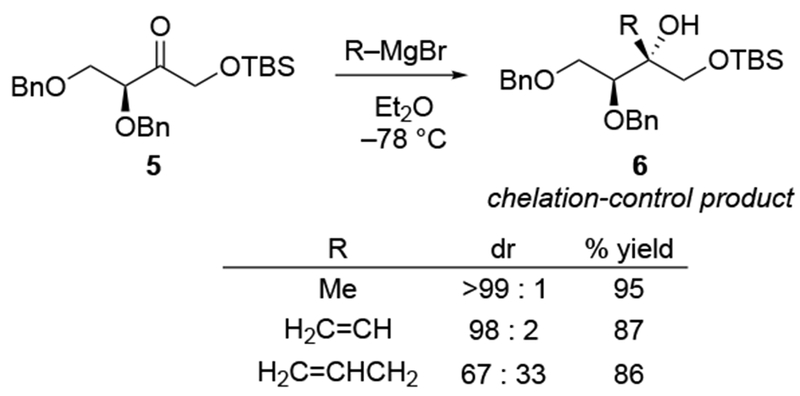

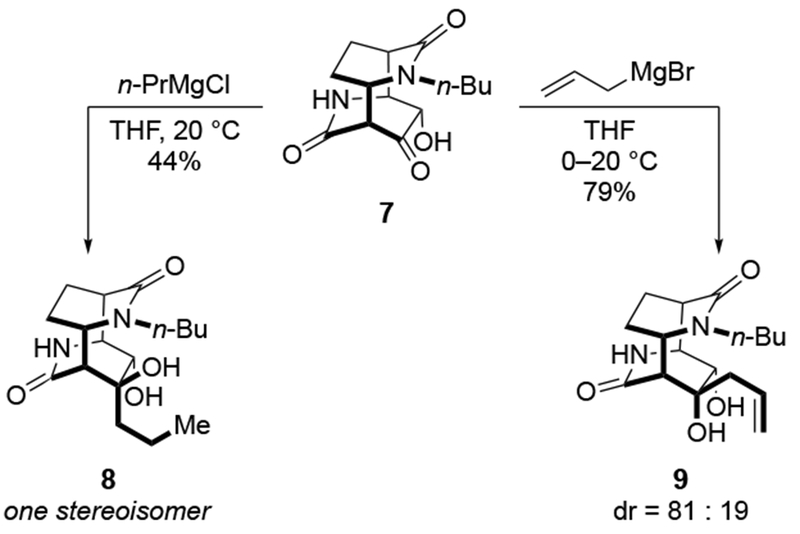

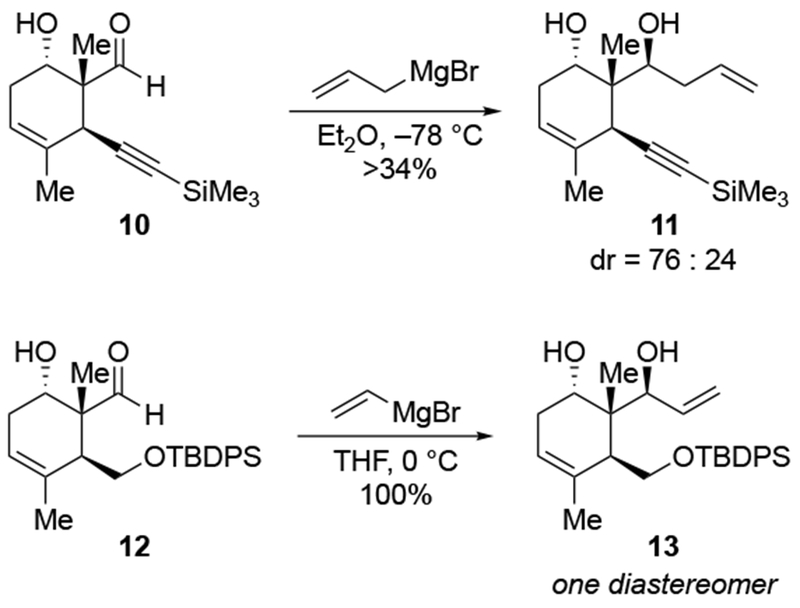

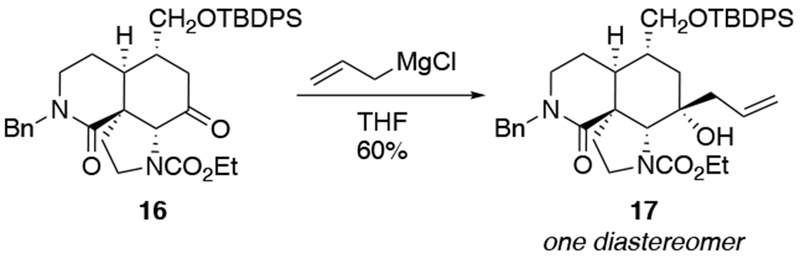

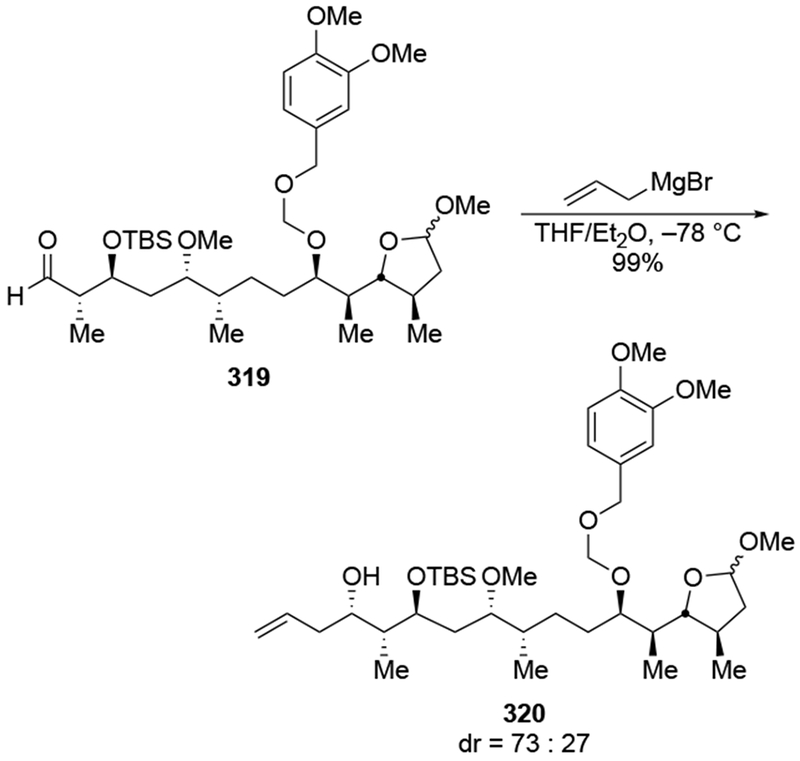

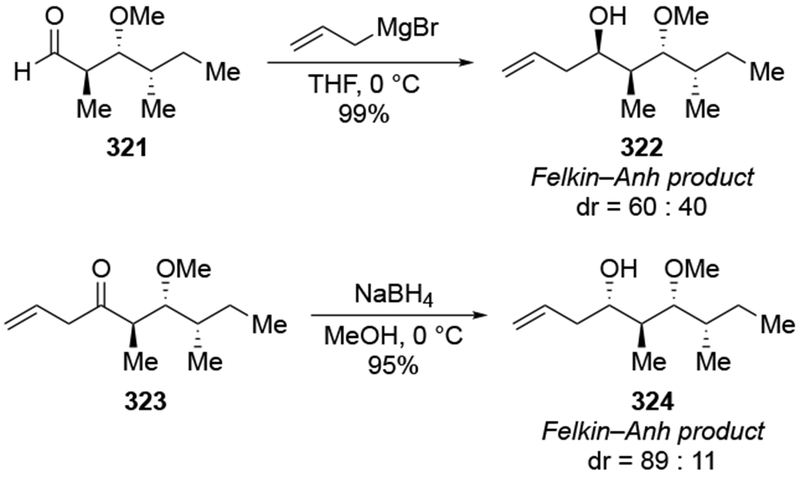

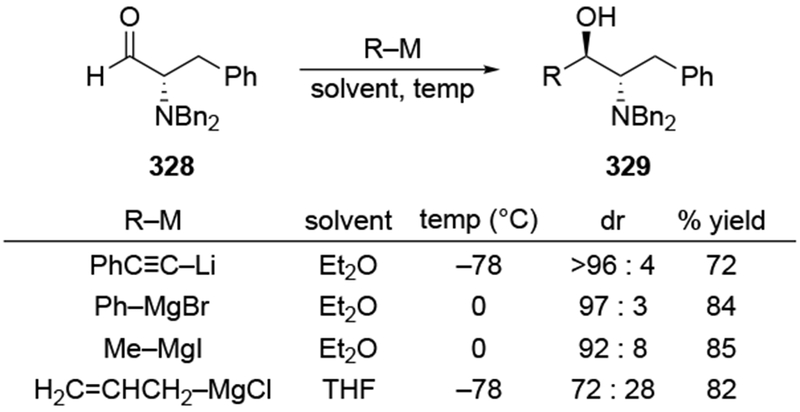

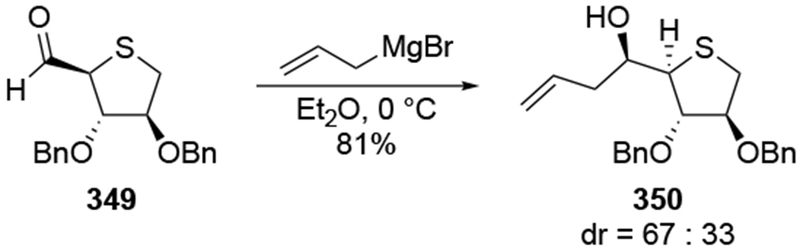

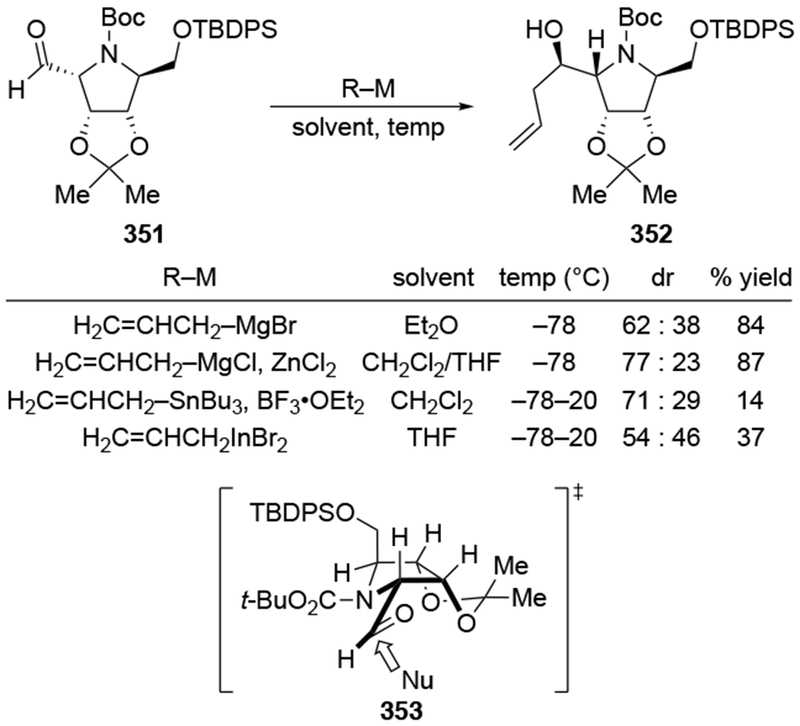

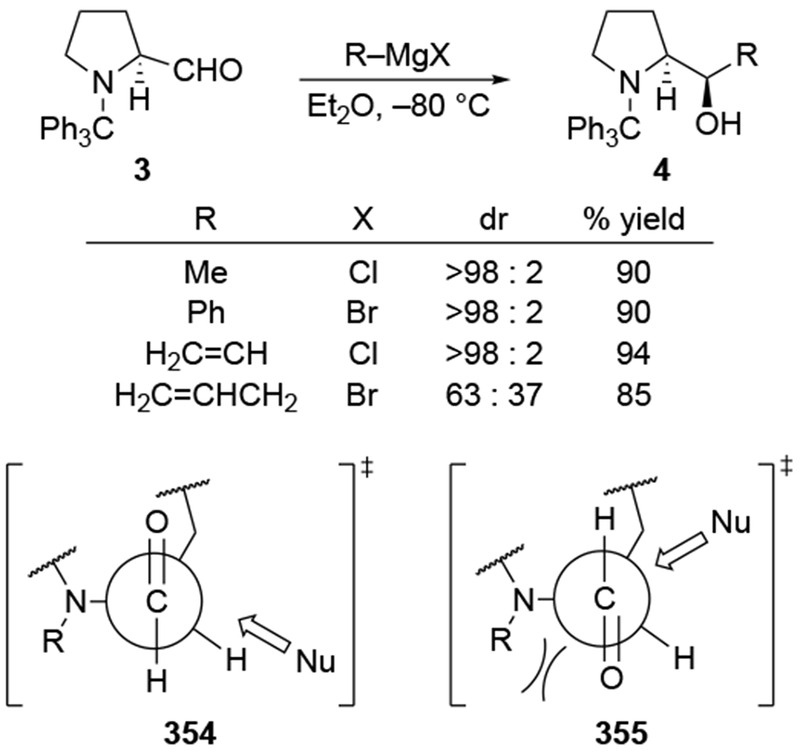

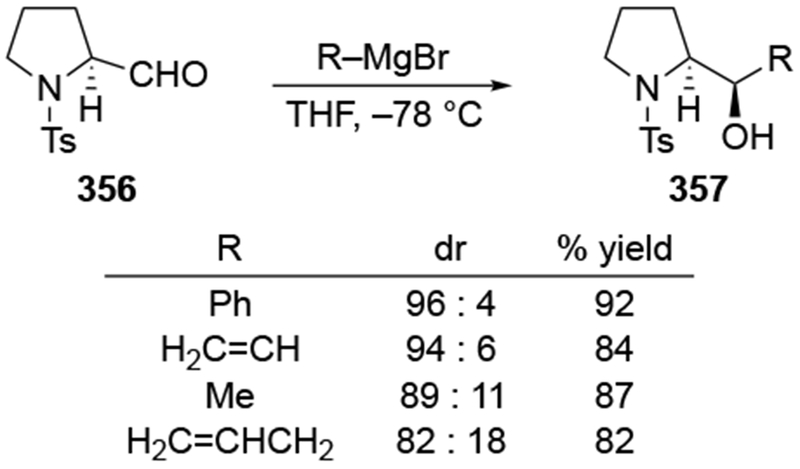

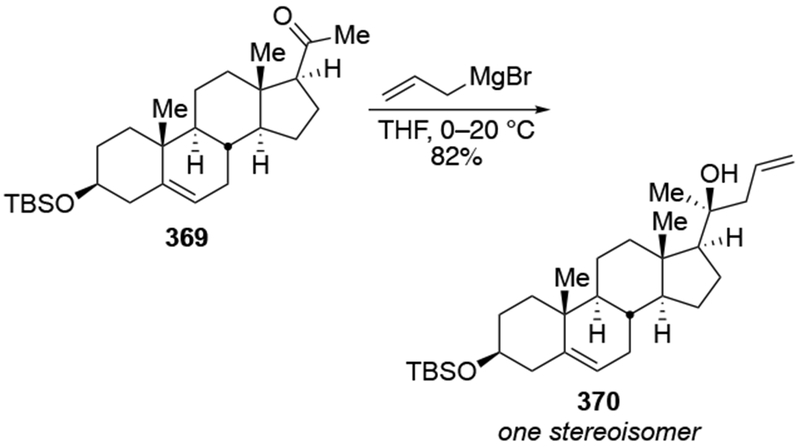

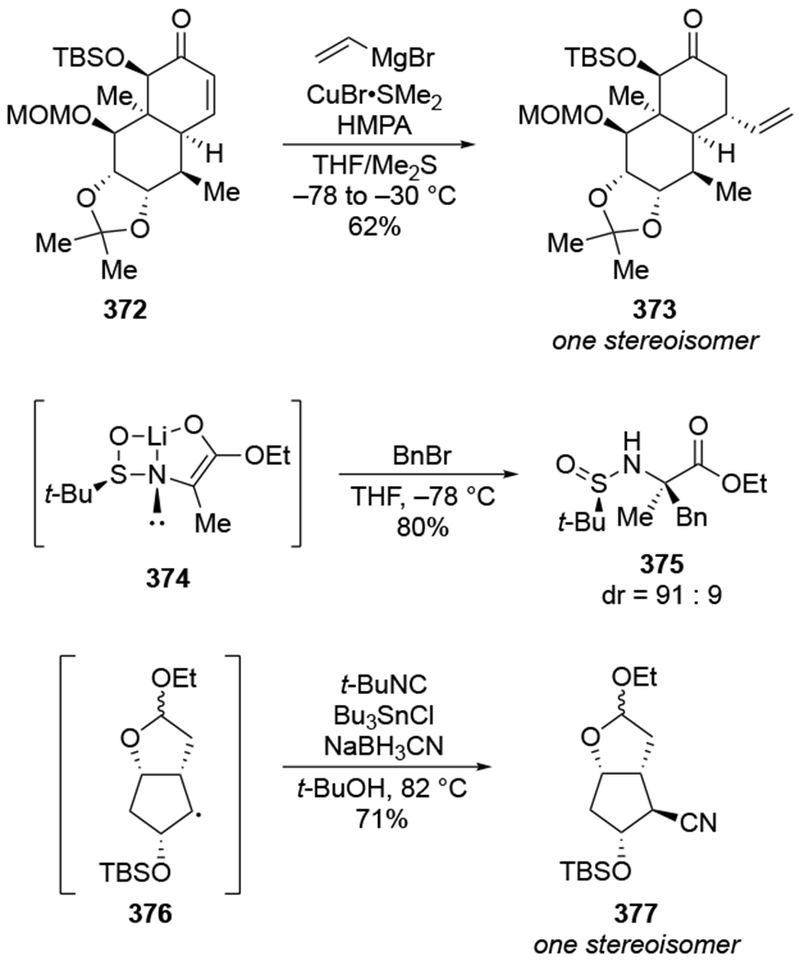

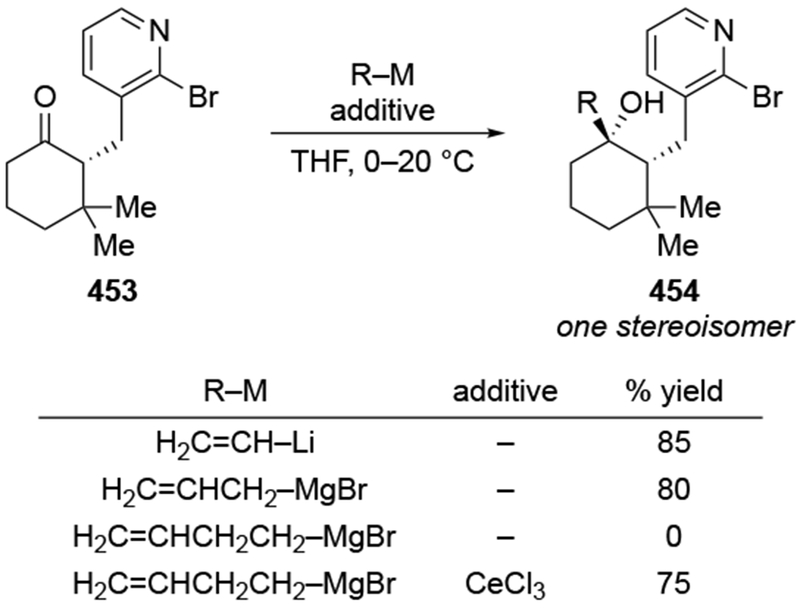

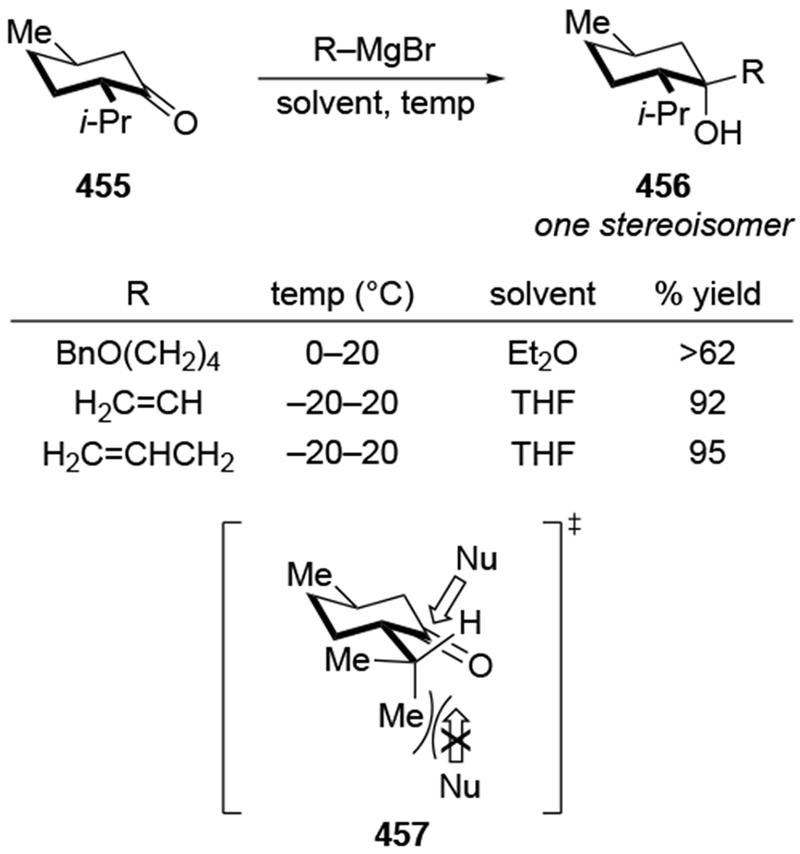

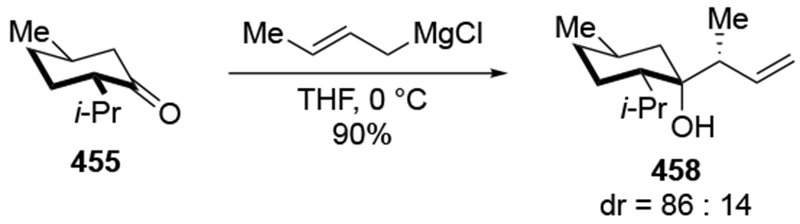

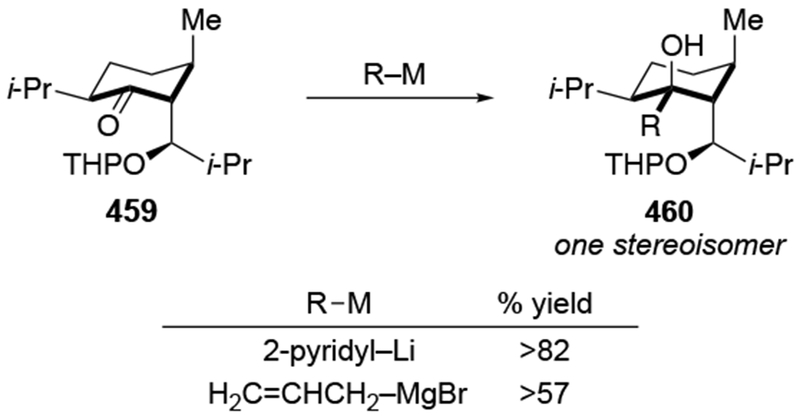

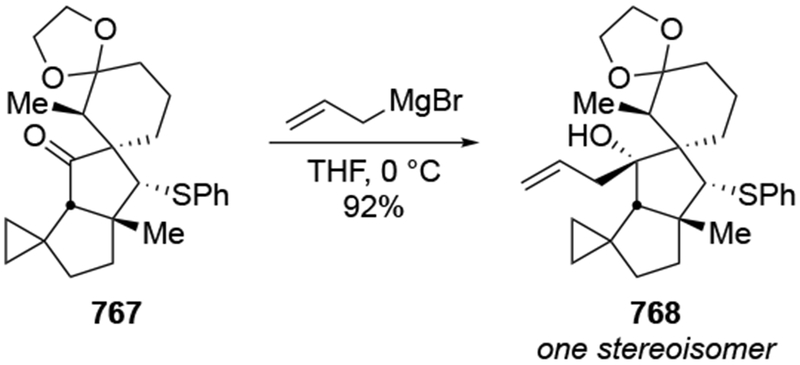

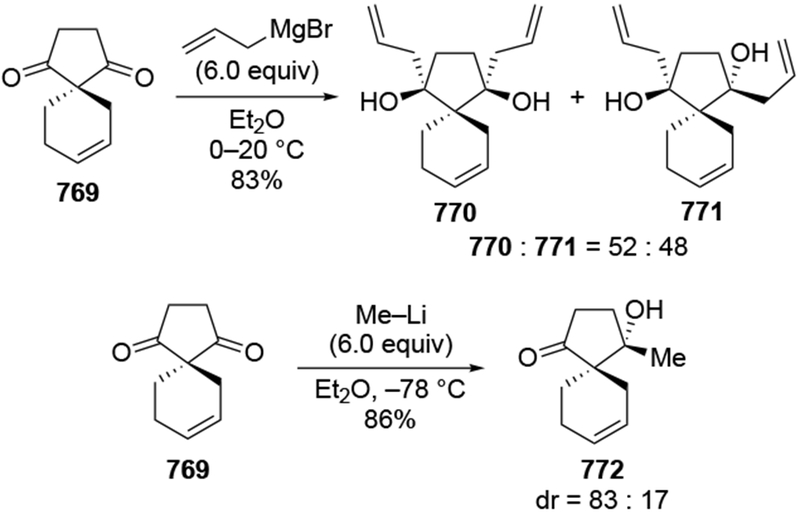

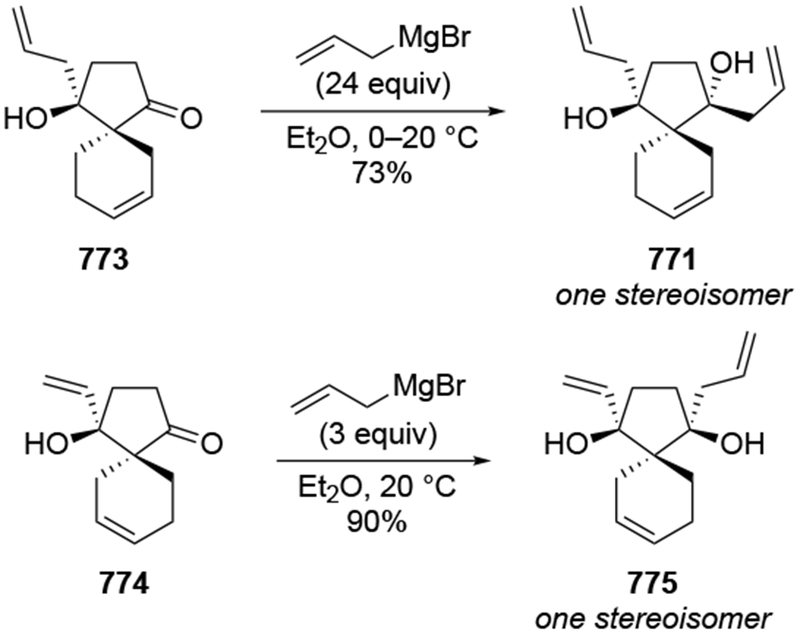

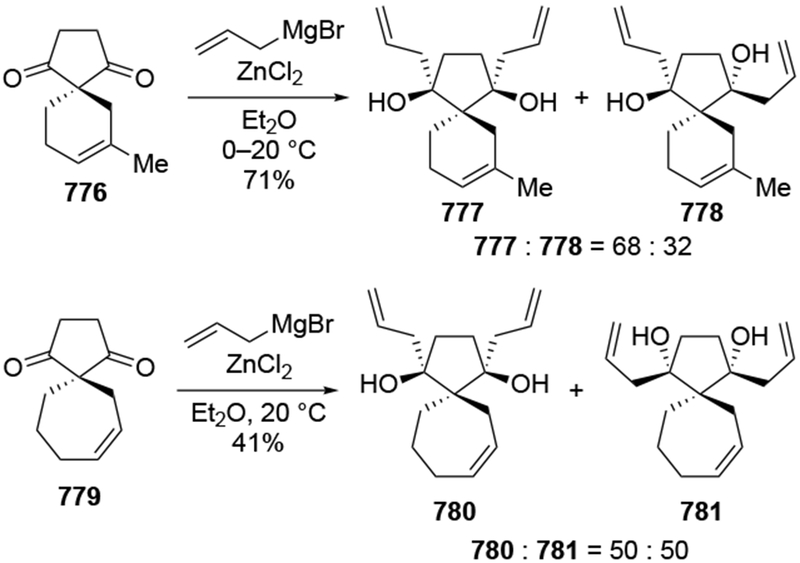

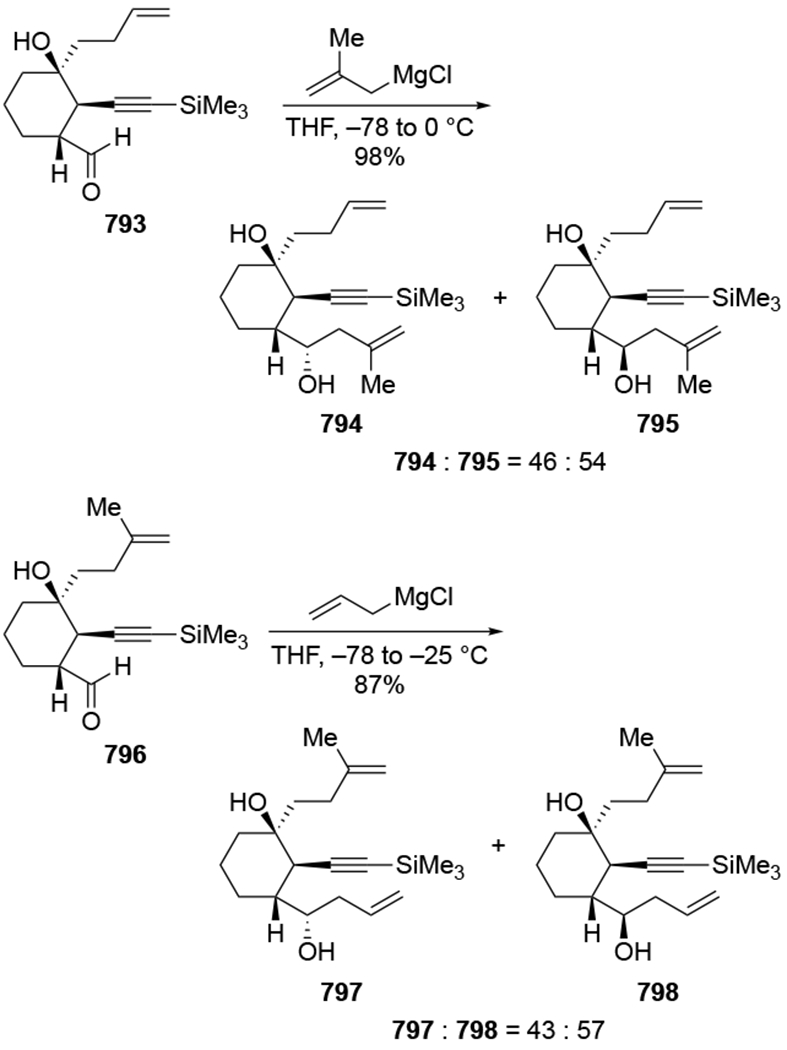

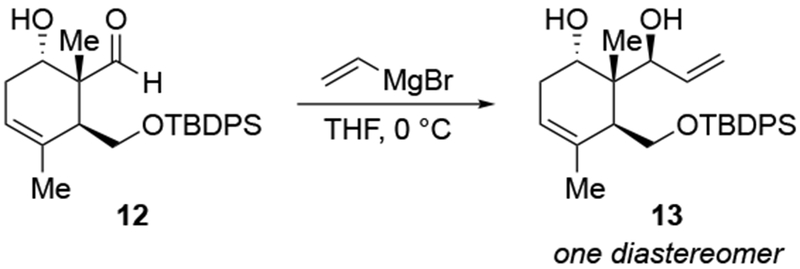

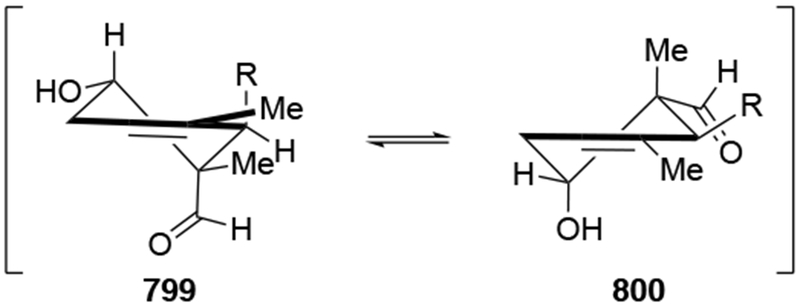

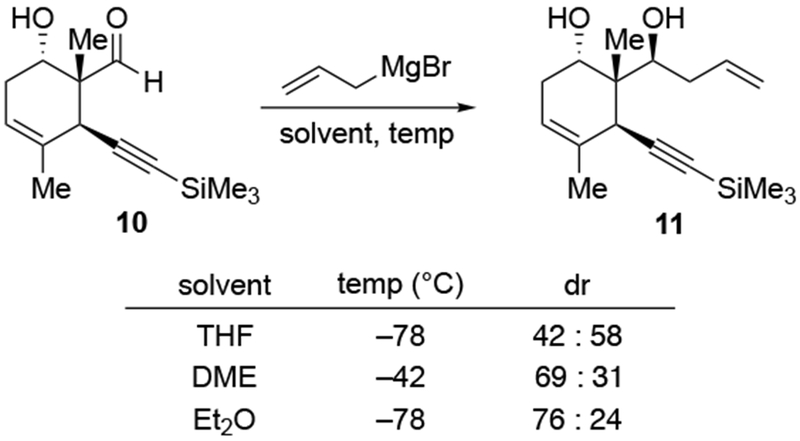

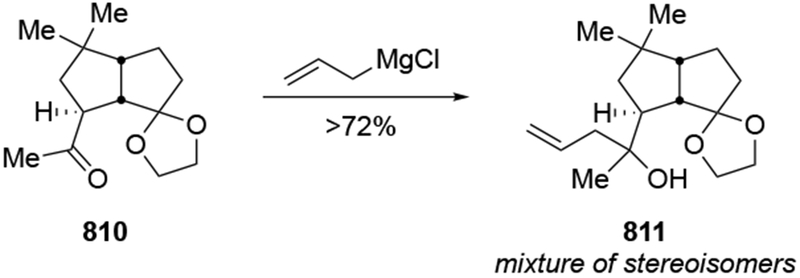

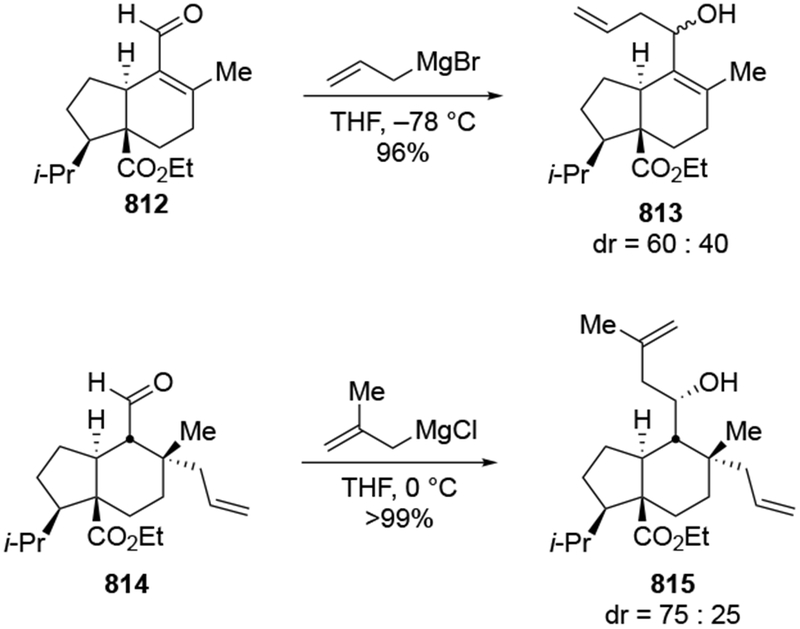

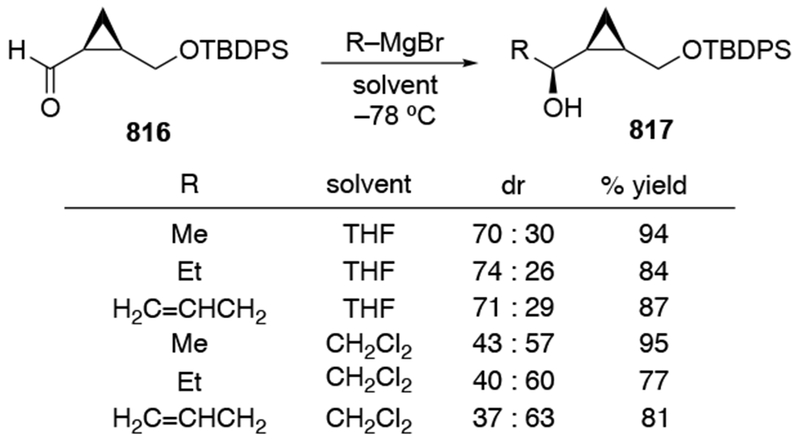

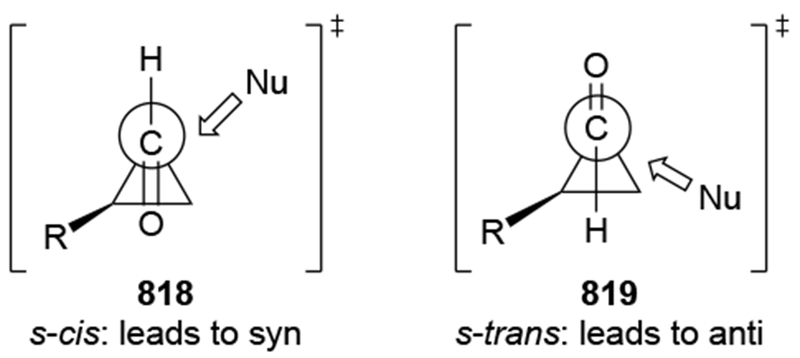

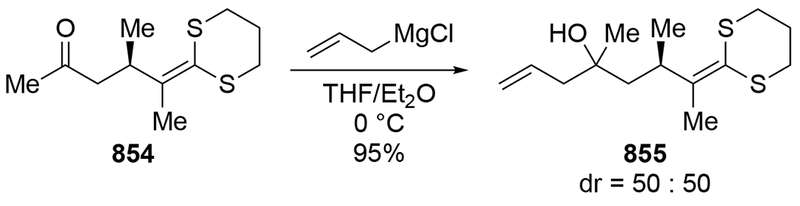

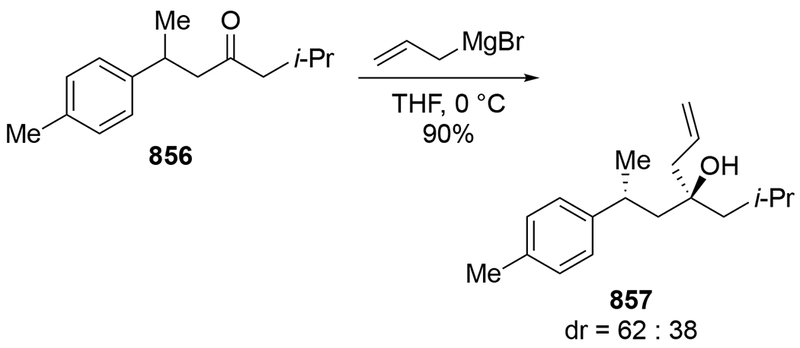

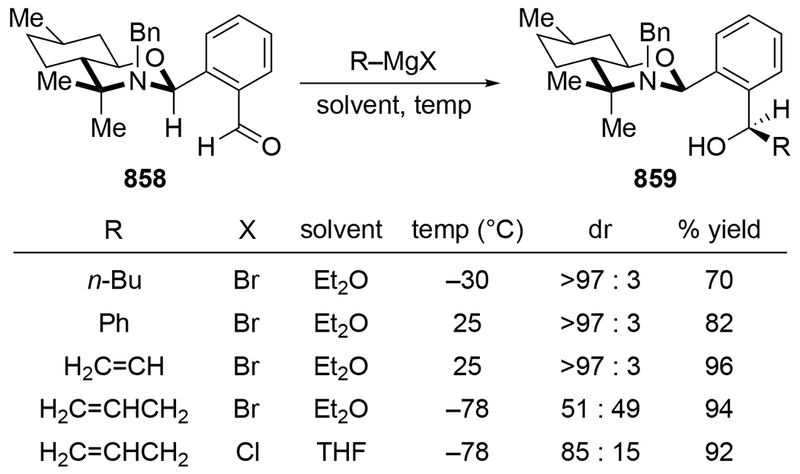

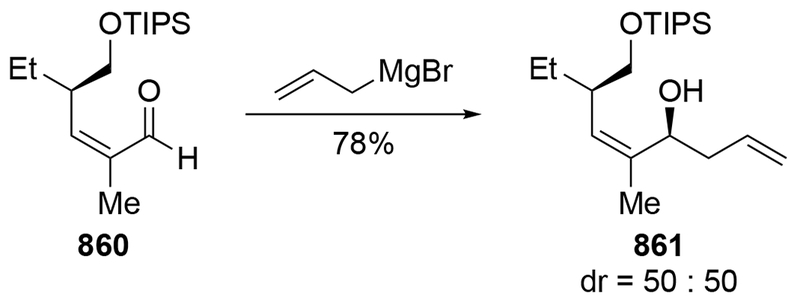

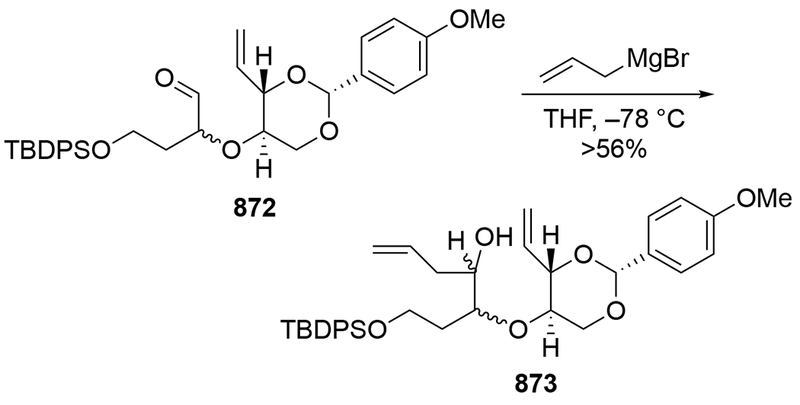

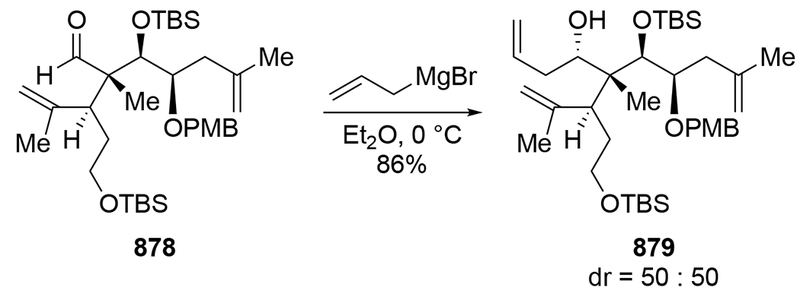

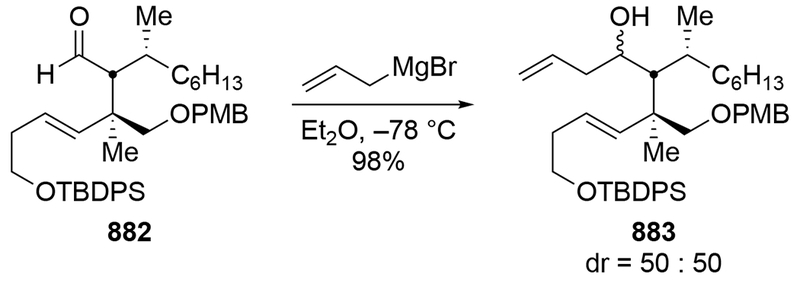

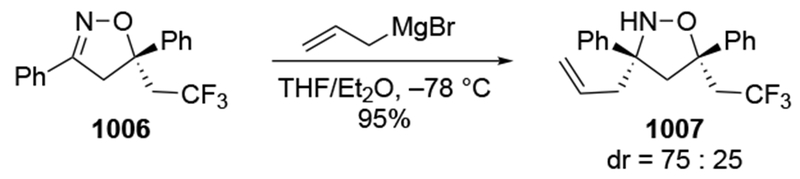

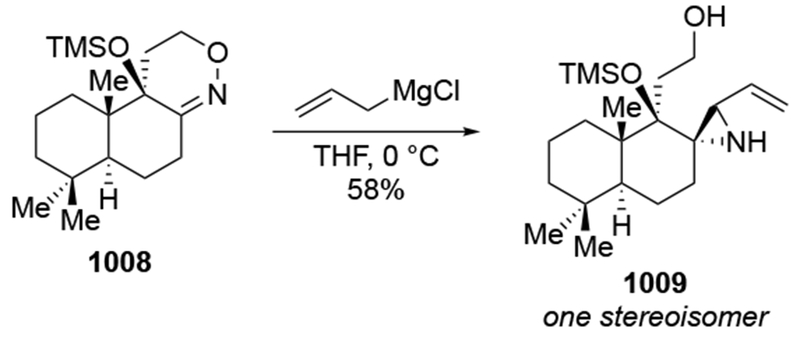

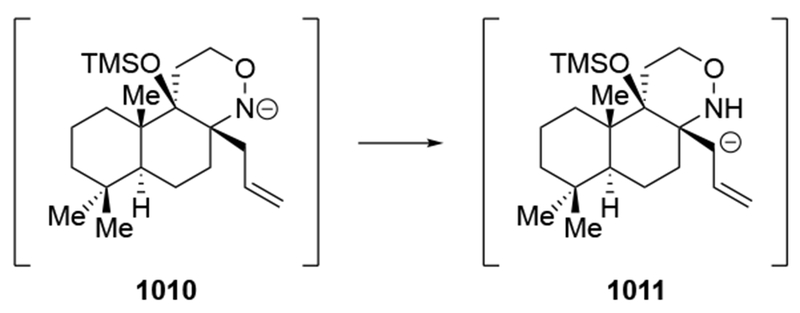

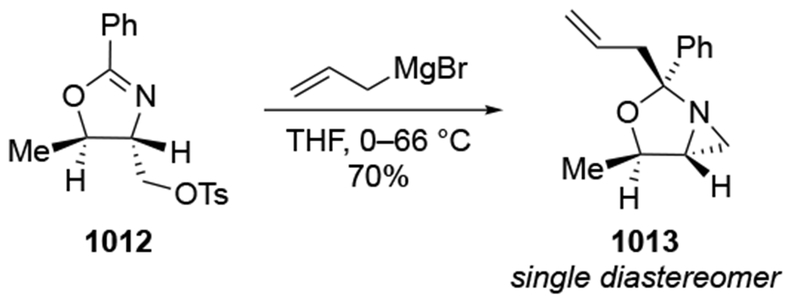

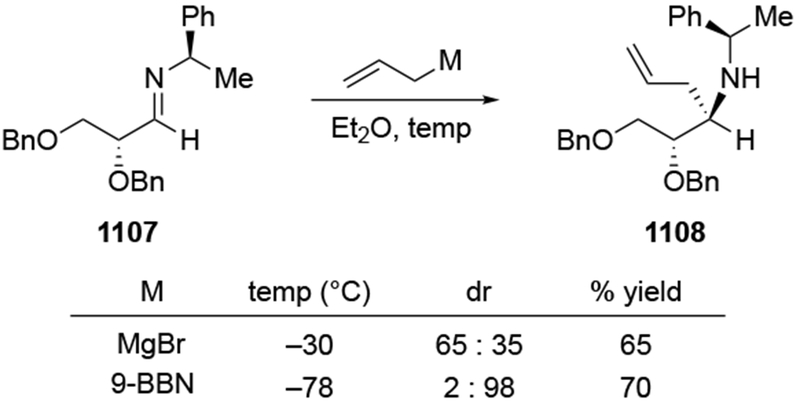

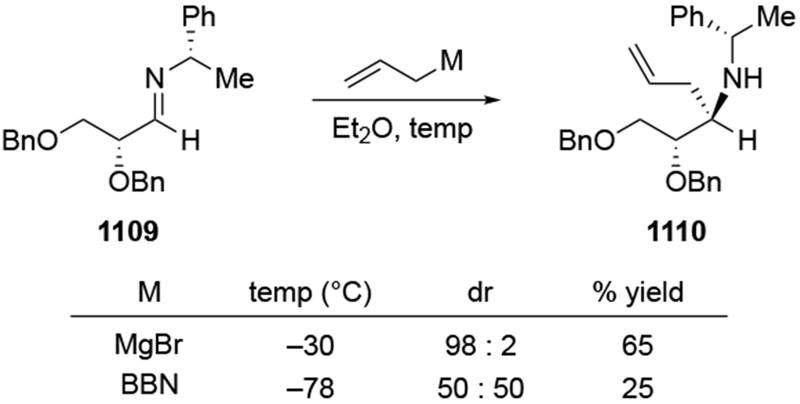

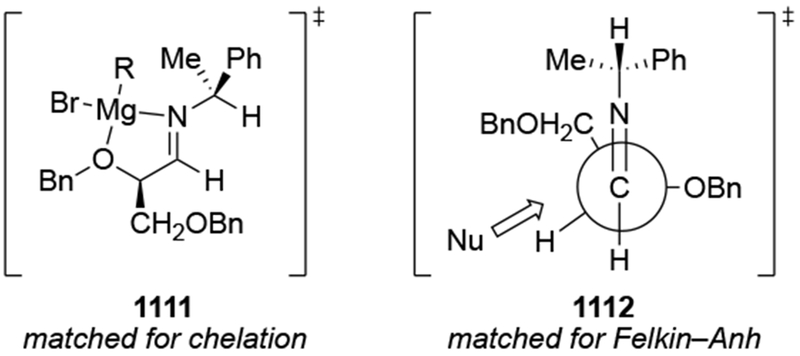

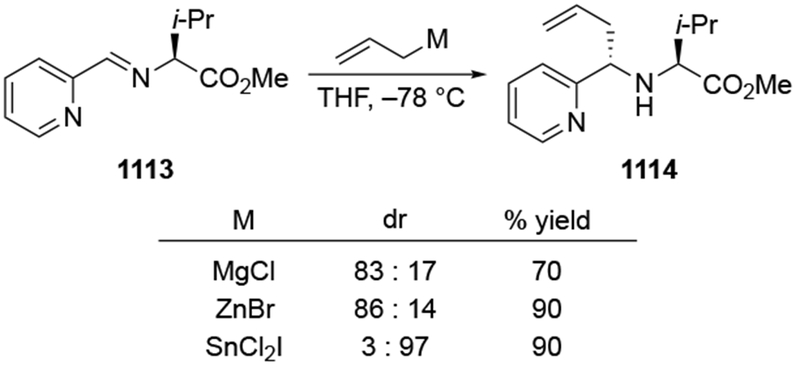

The reactions of allylmagnesium reagents, unfortunately, do not always follow models normally used to predict and explain the stereochemical outcomes of additions to carbonyl compounds. The Felkin–Anh or related models (for example, Scheme 23) and the chelation-control model (for example, Scheme 34) often fail to rationalize the product obtained in these transformations, although they can explain selectivities observed for additions of other organometallic nucleophiles. In some cases, allylmagnesium reagents react with opposite selectivity to other Grignard reagents5–7 (for example, Scheme 4).8 These problems can hinder efforts to develop stereoselective syntheses of natural products using allylmagnesium reagents, as illustrated for additions to structurally similar substrates 109 and 12,(Iwasaki et al. 2006, #301) which occur with contrasting selectivities (Scheme 5). Synthetic chemists often use allylation reactions because of the operational simplicity of the transformation, the commercial availability of the reagent, and the synthetic utility of the products,10–14 even when these reactions are not stereoselective or their outcome cannot be predicted.15,16

Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

Scheme 5.

1.2. Purpose of the Review

This review documents the additions of allylmagnesium nucleophiles to chiral carbonyl compounds, imines, and related electrophiles to provide a guide to understanding when these reactions will likely occur with stereoselectivity and when they will likely not. The outcomes of the reactions described herein are analyzed using common stereochemical models and analysis of possible transition states. Because these models often fall short of explaining the outcomes of additions of allylmagnesium reagents, in some cases the analysis provided in the original papers will be supplemented with an analysis guided by our recent studies of the unusual reactivity of these reagents.17,18 The review focuses on examples reported since this topic was reviewed in 197119, although additions to chiral carbonyl compounds were not discussed in that review. The present review will emphasize more recent examples through 2018, particularly those applying to complex target synthesis, although some older work will be discussed for context. Comparisons to either different organomagnesium reagents or different allylmetal reagents have been provided in many cases to illustrate the unusual behavior of allylmagnesium reagents. Considering that other allylmetal reagents and their reactivities have been reviewed recently,20,21 that material will not be covered in depth. Generally, reactions that use allylmagnesium reagents directly, without transmetallation to other organometallic species, will be discussed, although some examples of such reactions will be included for comparison.

The purpose of this review is several-fold. It should inform chemists who see unexpected results with allylmagnesium reagents that their observations are not unique: many authors see divergent results for these reagents compared to other organomagnesium reagents. This review is also intended to explain why the selectivities might be different based upon the latest understanding of the mechanism of these reactions and the implications of that mechanism. With that information available, researchers should be able to report their results using mechanistically sound arguments and by comparing their observations to related work. Furthermore, the review intends to show that mechanistic arguments using transition state models are not infallible, and that the underlying assumptions governing their application must be considered thoughtfully. It is necessary, in light of mechanistic information about how additions of allylmagnesium reactions occur,18 that stereochemical analyses use the most recent and relevant information. Consequently, many stereochemical outcomes are reconsidered here based on those insights. This review is also intended to help synthetic chemists predict what might happen in planned reactions, so that synthetic approaches can be devised with the highest probability of success. Finally, this review pays respect to the contributions of the authors who are cited because they have contributed to our understanding of the important synthetic reactions that use allylmagnesium reagents.

1.3. Experimental Details

The experimental details of these reactions are important to consider. Information such as solvents and temperatures are provided to facilitate comparisons, considering the influence that some solvents22 and temperature23 can have on the outcomes of additions of allylic organomagnesium reagents. In most cases, such details were available either in the text or Supporting Information of any article, but, on occasion, such information was unavailable. Other cases clearly document that allylations and other types of additions were performed, but no details such as diastereoselectivity were provided, so no specific insight could be gleaned.24 When temperatures were not listed, it was assumed that the reactions were conducted at room temperature if that were implied; otherwise, temperatures were not listed. Yields are reported as greater than some value if a yield were reported over multiple steps that include the addition reaction (in most cases, only the addition reaction was shown for clarity). Diastereomeric ratios are provided, although in some cases authors only note a single product, so that fact is indicated in the Scheme. In several cases, the text, figures, and experimental results reported deviate slightly in issues such as solvent, temperature, product ratios, and yields. In such cases, the values from the experimental sections were used, although it should be stressed that such differences are minor and do not affect conclusions. Finally, stereochemical assignments in all cases are based upon the analysis provided by the authors of the individual papers and are assumed to be correct.

1.4. How to Use this Review

Although it would be ideal to read this review in its entirety, that idealistic view will only be possible for a reader with a considerable amount of time to devote to this subject. A reader could still appreciate the topic by selecting a specific topic from the Table of Contents and focusing on the examples therein. As the reader then generates questions regarding reaction mechanisms and reasons for stereochemical outcomes, then the introductory sections might be more useful.

2. Impact of the Mechanism of Addition Upon Stereoselectivity

2.1. Current Understanding of the Mechanism of Additions of Allylmagnesium Reagents to Carbonyl Compounds

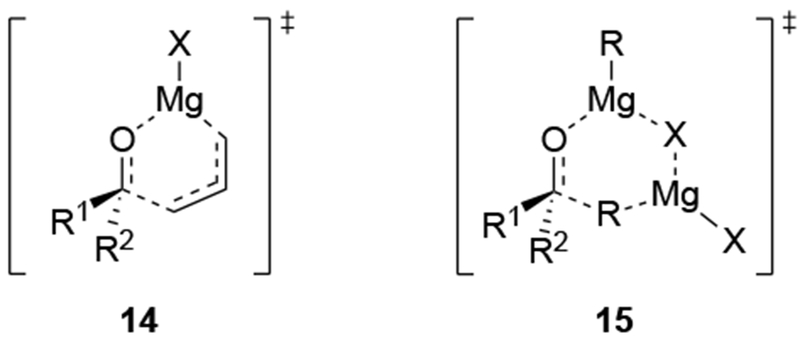

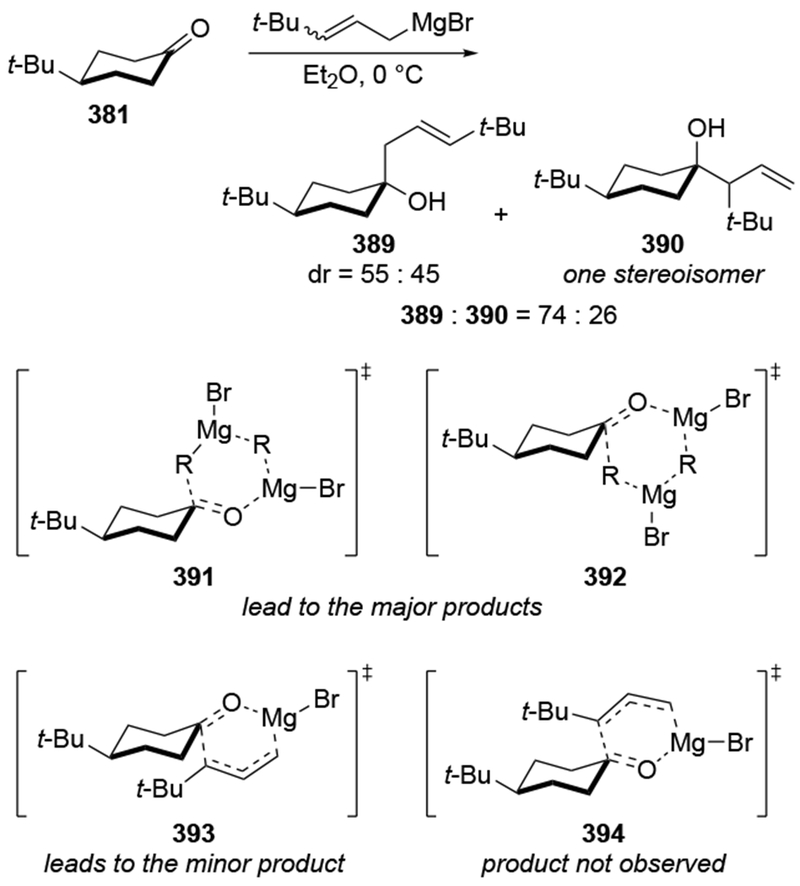

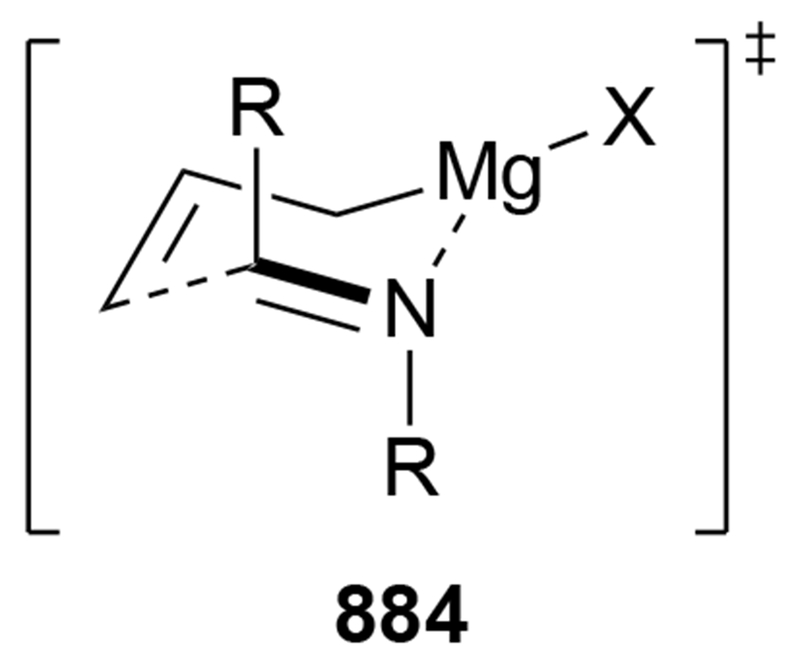

Recent studies provided insight into the mechanism of additions of allylmagnesium reagents to carbonyl compounds.18 Computational25 and experimental23 studies suggest that a concerted, six-membered-ring transition state is most likely responsible for the addition (i.e., 14, Scheme 6). This pathway, which was proposed many years ago based upon mechanistic studies with substituted allylic organomagnesium reagents,26 is unique among pathways for additions of organomagnesium reagents to carbonyl compounds. Non-allylic Grignard reagents react through different types of transition states, including four-center transition states and six-membered-ring transition states involving dimers of the reagents (i.e., 15).27 Considering the differences in addition mechanisms between allylic and non-allylic organomagnesium reagents, it may not be surprising that the stereochemical outcomes of addition reactions are different.

Scheme 6.

2.2. Diffusion-Controlled Additions

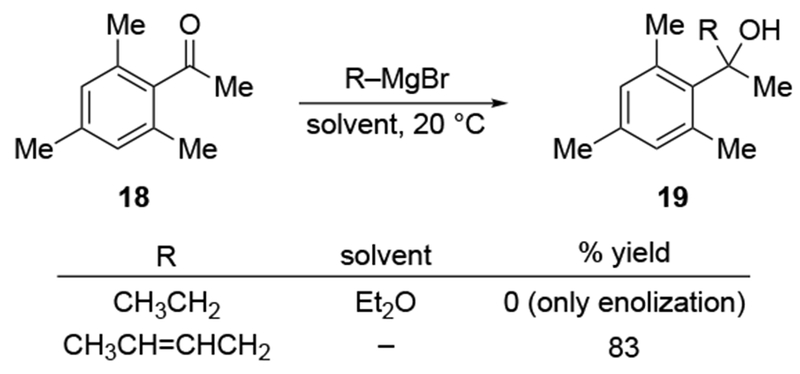

The most important mechanistic consequence of the six-membered-ring transition states through which allylmagnesium halides react is that these addition reactions proceed unusually quickly. Anecdotally, researchers noted the high reactivity of allylmagnesium reagents, a fact established carefully decades ago.28,29 This high reactivity allows allylmagnesium reagents to add to ketones for which no other organometallic nucleophile will add (Scheme 7)30 or to ketones that generally only undergo enolization (Scheme 8).31,32 In particular, additions of allylic Grignard reagents to unhindered carbonyl compounds likely occur at rates approaching the diffusion rate limit,28 although rates would be slower for additions to particularly hindered carbonyl compounds.17 This high reactivity can be synthetically useful and provides a strongly compelling reason to continue to use these reagents.

Scheme 7.

Scheme 8.

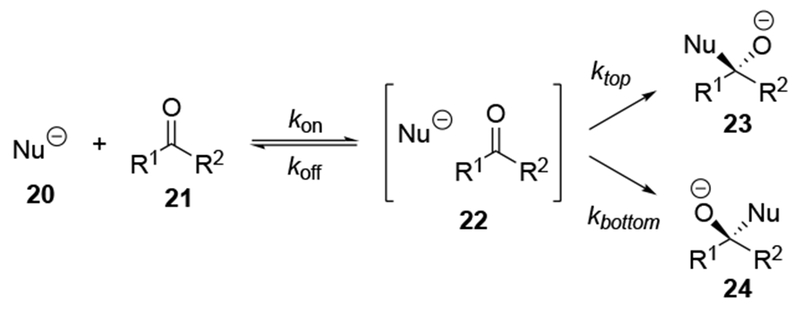

The high reactivity of allylmagnesium reagents comes at a cost of decreased stereoselectivity. This problem is best illustrated by considering the key steps involved in addition to a carbonyl compound (Scheme 9). Before the new carbon–carbon bond is formed, the nucleophile and electrophile must diffuse toward each other and form an encounter complex (i.e., 22) with a rate constant of kon. At that point, the nucleophile can attack the prochiral carbonyl compound (21) from either the top or bottom face, two processes that are competitive with the separation of encounter complex (the path labeled koff). As addition to the carbonyl group becomes faster with more reactive reagents, eventually the rates of ktop and kbottom become faster than the rate at which the two reaction partners can dissociate from each other (that is, ktop, kbottom >> koff). In this case of high reactivity, the transition state for bond formation no longer exclusively determines the selectivity of a reaction, but the manner in which the two components diffuse to one another (i.e., kon) will also influence diastereoselectivity. This change of the selectivity-controlling step from bond formation to diffusion has been documented for chemoselective additions to carbocations33 and stereoselective reactions of oxocarbenium ions.34–37 Therefore, as the rates of carbon–carbon bond formation approach the diffusion rate limit, the stereochemistry-determining step can be the approach of the reagents to each other (i.e., the step corresponding to kon), as illustrated in Scheme 9. Stereochemical models do not hold in this scenario because facial selectivity is determined before the carbon–carbon bond forming step.38 Therefore, any analysis of stereoselectivity must first consider whether these reactions might be diffusion-controlled or not. If the reaction were under diffusion control, then the diffusion step must be analyzed, not the bond-forming step.

Scheme 9.

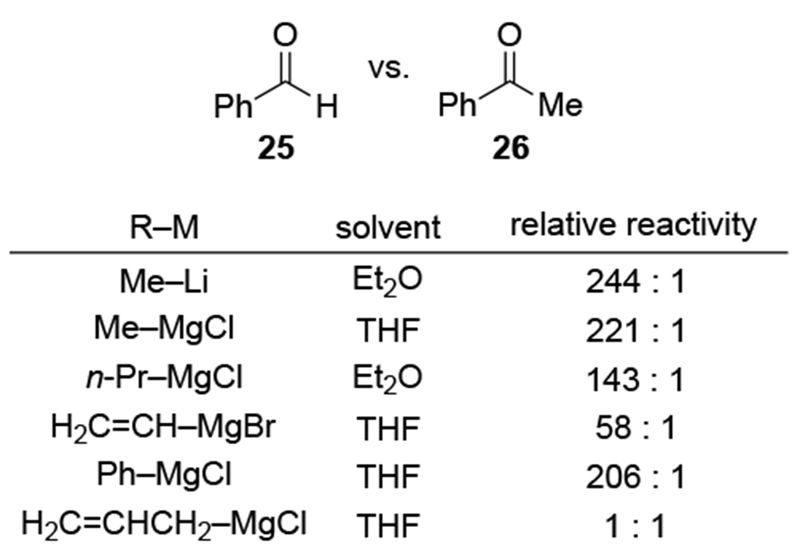

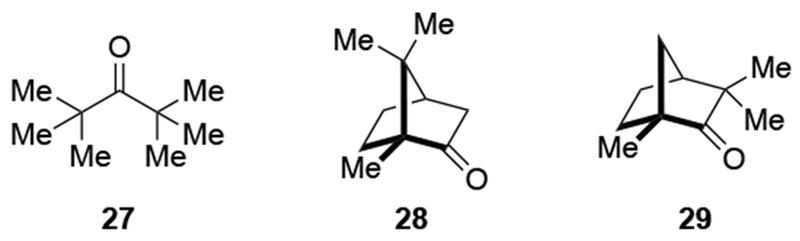

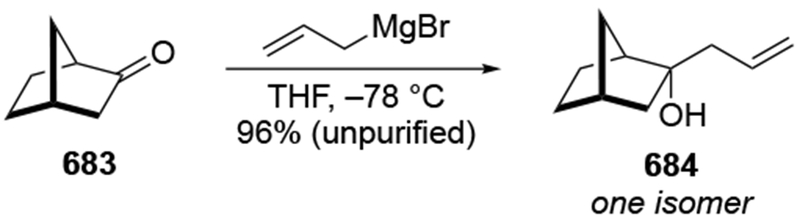

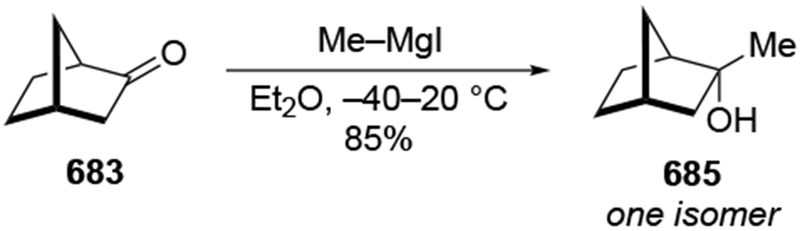

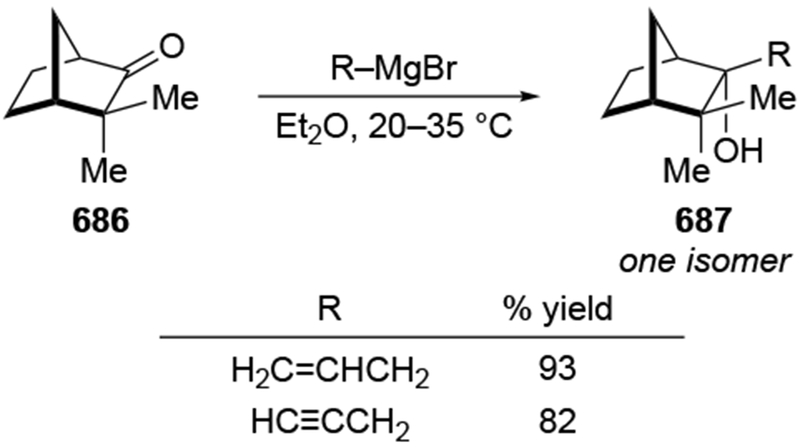

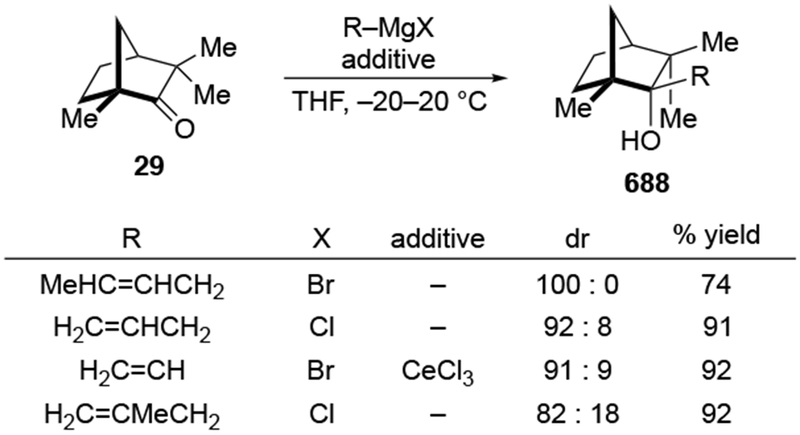

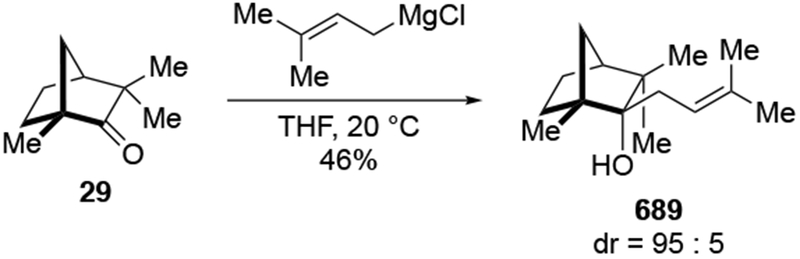

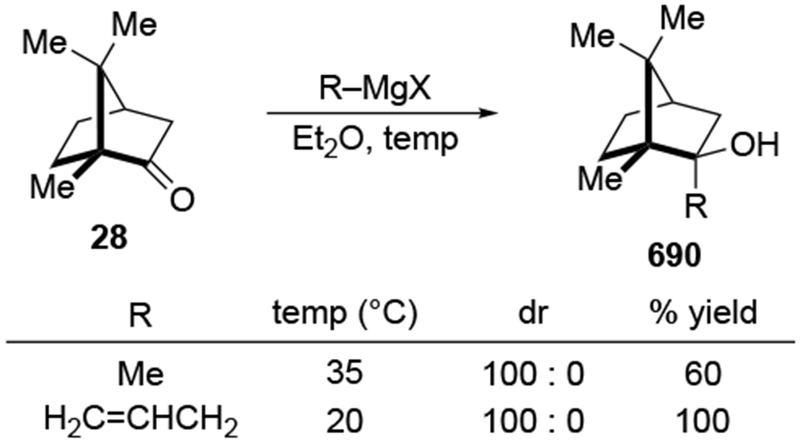

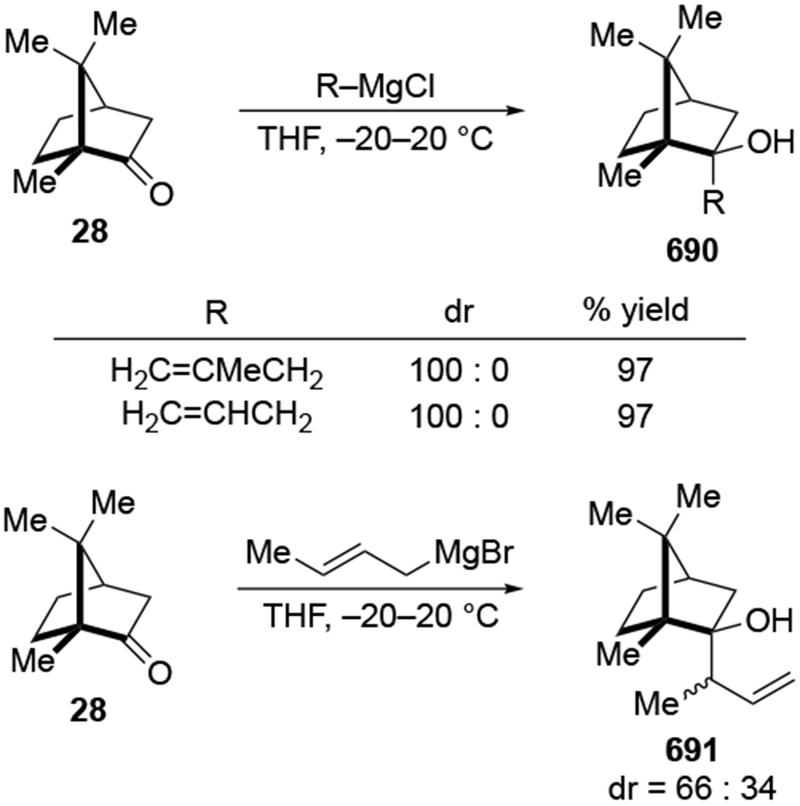

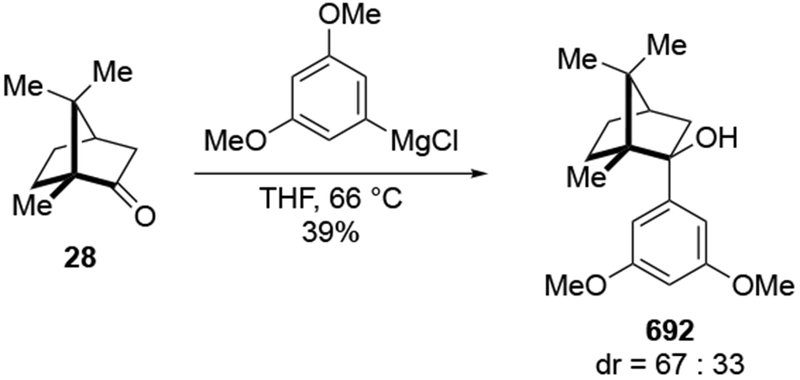

Recent studies suggest that additions of allylmagnesium reagents to aldehydes and most ketones occur at the diffusion rate limit.17,18 While most other organomagnesium reagents (and methyllithium) show dramatically different rates of addition to acetophenone and benzaldehyde, allylmagnesium reagents react with both at the same rate (Scheme 1017).28 These facts lead to the conclusion that many reactions of allylmagnesium reagents with ketones cannot be analyzed using transition state models, but, instead, must be analyzed by considering the diffusion step. Only in the case of highly hindered ketones, such as di-tert-butyl ketone (27), camphor (28), and fenchone (29, Scheme 11), do rates likely fall below the diffusion rate limit.17,23 The much slower addition of allylic Grignards to these hindered ketones is consistent with the fact that the reduction of di-tert-butyl ketone (27) by NaBH4 at 0 °C is over 5,000 times slower than the reduction of acetone.39 The rapid rate of addition of allylmagnesium reagents to most carbonyl compounds suggests that these reactions cannot be made faster by catalysis.40,41

Scheme 10.

Scheme 11.

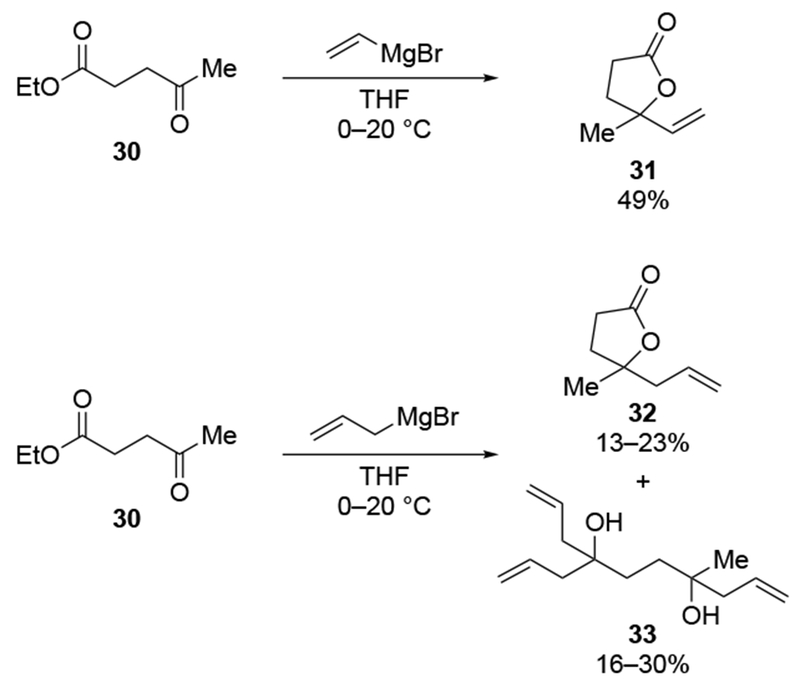

The lack of chemoselectivity resulting from the high rates at which allylmagnesium halides react presents a problem for multiply-substituted electrophiles commonly encountered in synthesis. Scheme 12 illustrates the problematic behavior of allylmagnesium bromide compared to vinylmagnesium bromide in such a system.42 Addition of vinylmagnesium bromide to compound 30, which contains both carbonyl and carboethoxy groups, resulted in addition to the carbonyl group followed by transesterification. Conversely, allylmagnesium bromide added to both the carbonyl and carboethoxy groups of compound 30 at comparable rates. Alternatively, the rate of addition to the carboethoxy group could be comparable to the rate of the intramolecular transesterification. Other evidence of the similar rates of additions of allylmagnesium reagents to aldehydes and esters have been reported.17 The ability of allylmagnesium reagents to add to esters rapidly can be useful for the analysis of triacylglyerols by facilitating deprotection of multiple ester groups,43 although it can complicate their application in natural product synthesis.44

Scheme 12.

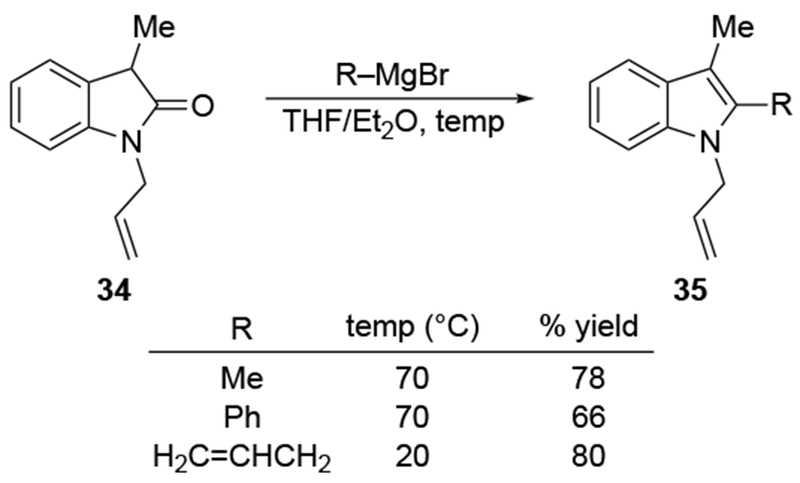

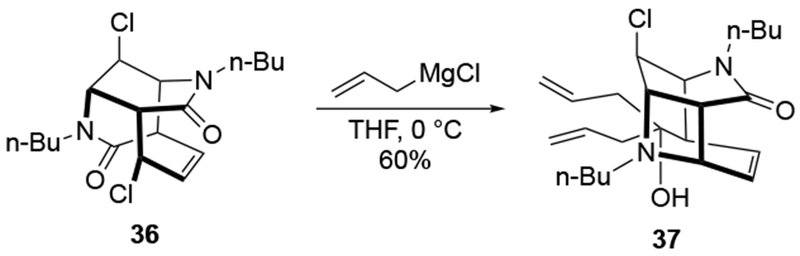

The high reactivity of allylmagnesium reagents even extends to the carboxamide functional group. In the addition to cyclic amide 34 (Scheme 13), allylmagnesium bromide reacted at room temperature, whereas higher temperatures were required to generate product 35 in good yield with the methyl and phenyl Grignard reagents.45 Multiple additions to amides are also not uncommon for allylmagnesium reagents, as illustrated in Scheme 14.46 It is notable that one of the two carboxamide groups of 36 does not react with the reagent, suggesting that chemoselectivity in allylic Grignard additions to complex molecules is possible. Other authors have noted similar behavior of allylmagnesium reagents with amides.47

Scheme 13.

Scheme 14.

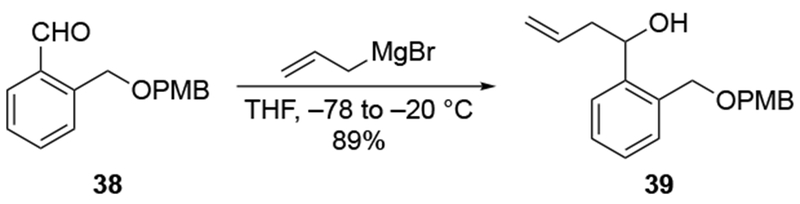

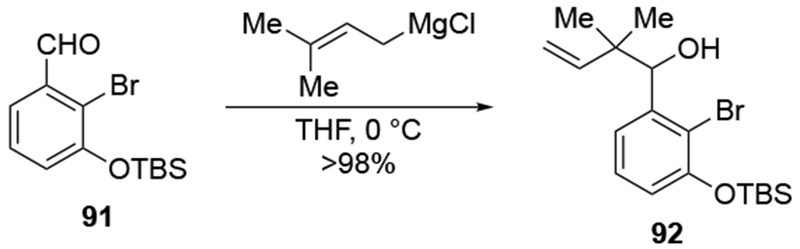

Even for reactions with seemingly simple electrophiles, the reactivity of allylmagnesium reagents can be quite useful (Scheme 15).48 Addition to aromatic aldehyde 38 using allylmagnesium bromide occurred in high yields, but efforts to achieve this allylation with allyltrimethylsilane and Lewis acids either gave no reaction or resulted in decomposition. This example illustrates the value of allylmagnesium reagents among the many reagents used to form allylated products.

Scheme 15.

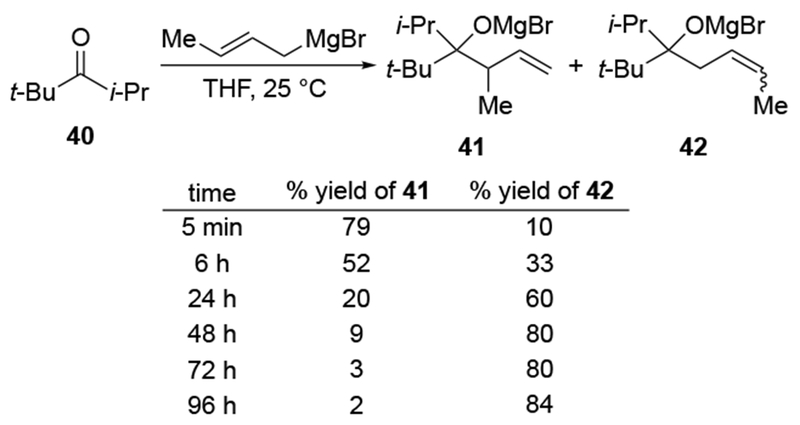

2.3. Reversibility of Addition Reactions

For highly hindered carbonyl compounds, additions of some organomagnesium reagents can be reversible. The reversibility of additions of allylic magnesium reagents was first examined by Benkeser and co-workers, who monitored the isomerization of homoallylic magnesium alkoxides formed after addition of a crotyl Grignard reagent (Scheme 16).49,50 The observation of reversible reactions was established with sterically hindered ketones and long reaction times to achieve complete equilibration. In the case of addition of the smaller reagent, allylmagnesium bromide, to di-tert-butyl ketone (27), the reverse reaction required heating to reflux in THF.51 Other reversible additions are also slow: the reverse of the additions of benzylmagnesium reagents were performed at 140 °C for three to ten days.52 As a result, reversibility is not likely to occur, even in hindered systems, if reactions were quenched after the addition reaction.23 This protocol is normally followed by synthetic chemists.

Scheme 16.

2.4. Importance of Reaction Rate to Understanding Stereoselectivity

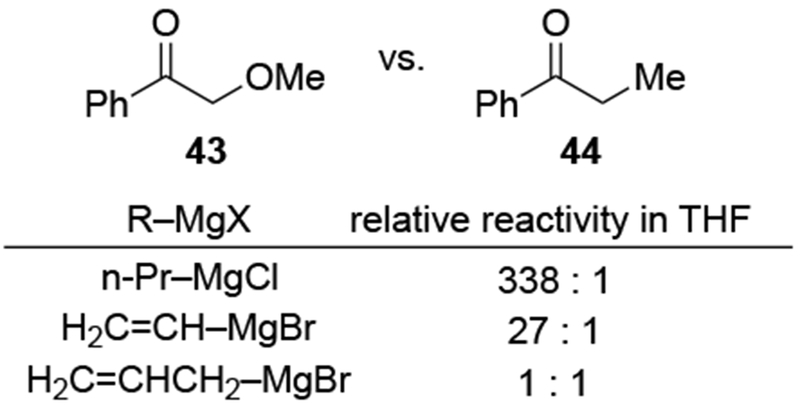

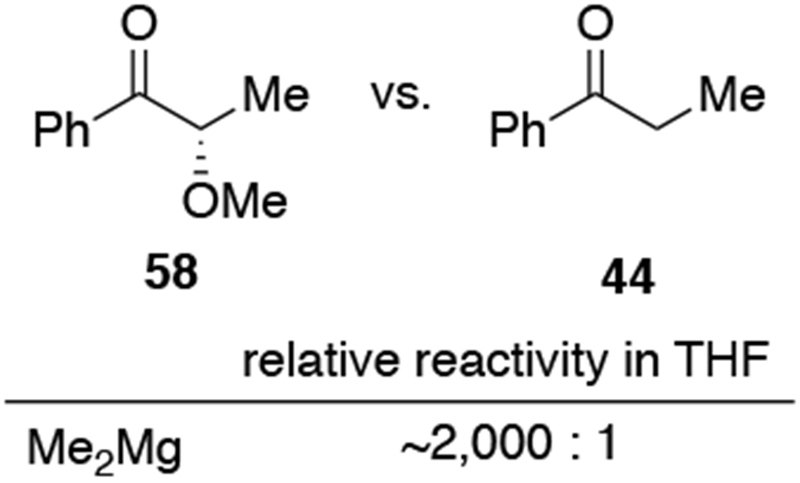

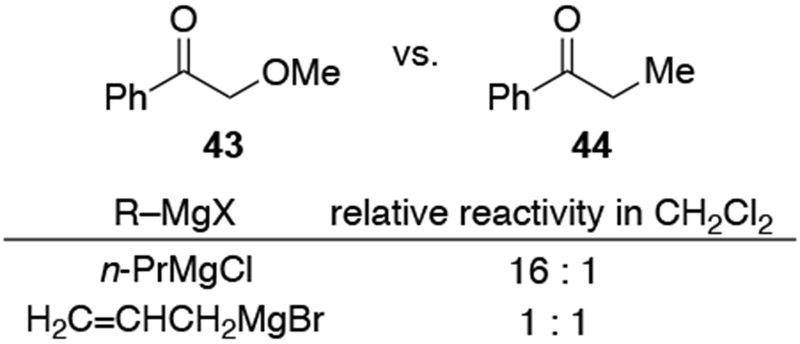

Competition experiments provide important insights into if and when stereoselectivity should be expected from reactions. Because the rate at which allylmagnesium nucleophiles react with carbonyl compounds approaches the diffusion limit, traditional rate measurements (or even stopped-flow measurements) cannot provide rate constants for these reactions.28,29 Such competition experiments can provide insight not only into chemoselectivity (Scheme 10 above) but also can reveal why, in some cases, additions of allylmagnesium reagents may not be diastereoselective. For example, competition experiments suggest why additions of allylmagnesium halides to α-alkoxy ketones in ethereal solvents are not generally diastereoselective (Scheme 17).22 Considering that addition through a chelated transition state should be faster than additions through a non-chelated transition state,53–55 the fact that addition of an allylmagnesium reagent to a chelating ketone is not faster than addition to a non-chelating ketone22 suggests that any explanations for stereochemical control involving chelation should be considered with some skepticism. Consequently, additions that can be analyzed using Felkin–Anh, Cieplak, Cornforth, and related models56,57 would also need to be evaluated as to whether or not the stereochemical outcome arises instead from diffusion-controlled behavior. Such studies would be relatively simple to perform in cases where sufficient quantities of the carbonyl compound were available, as is often the case in methodological studies. Information about relative reaction rates of reactions can be obtained using carefully controlled competition experiments.17 As a result of the recent relative rate studies of allylic Grignard reagents, the analyses reported in this review will necessarily make assumptions about relative rates based upon reasonable comparisons, as will be described below.

Scheme 17.

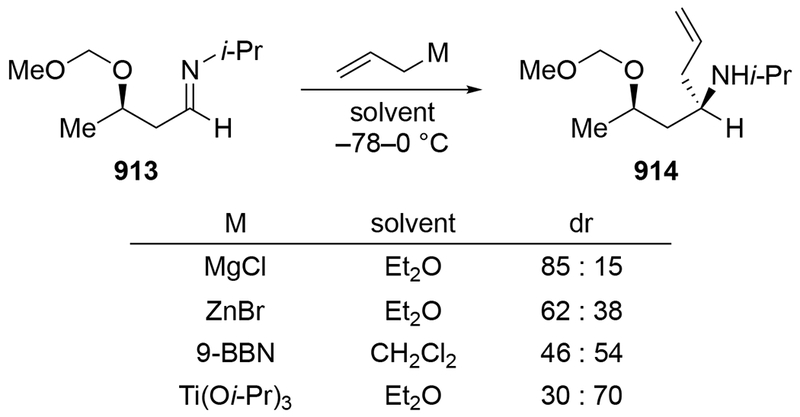

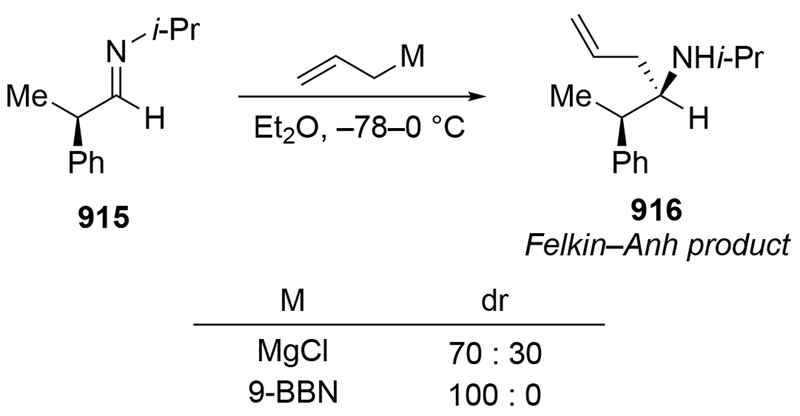

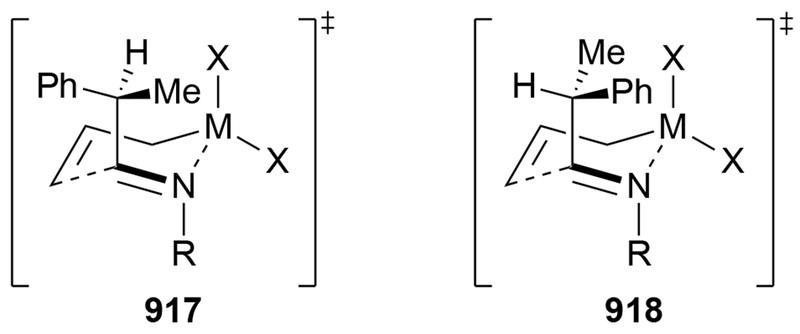

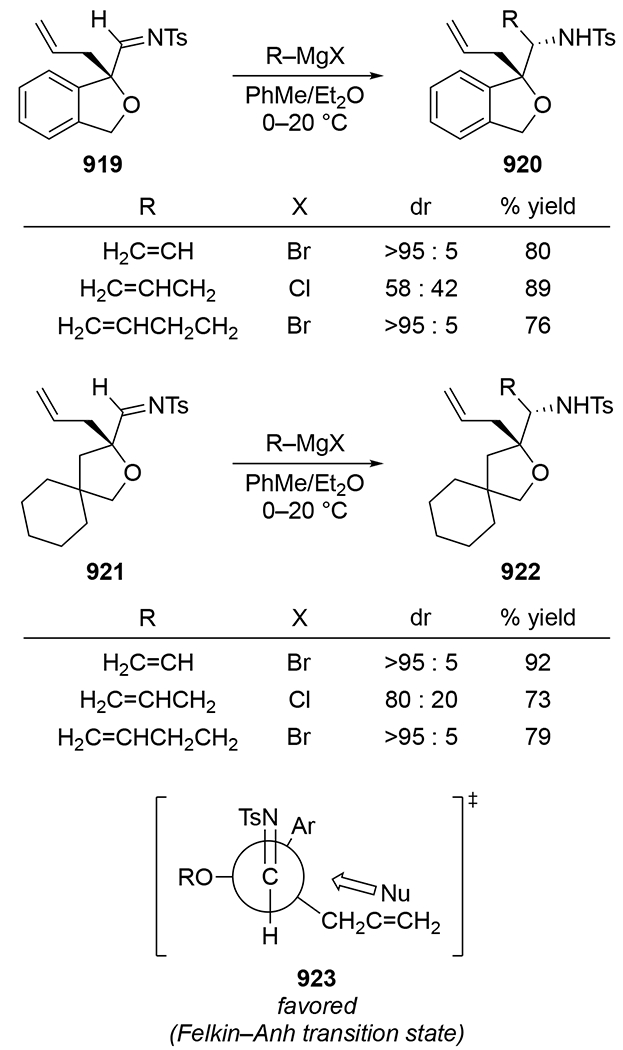

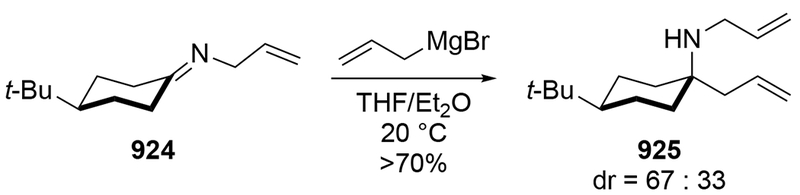

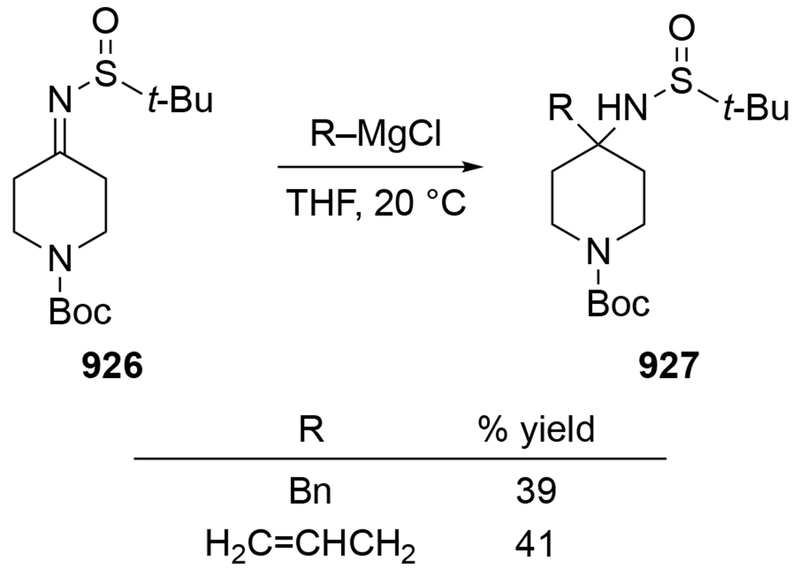

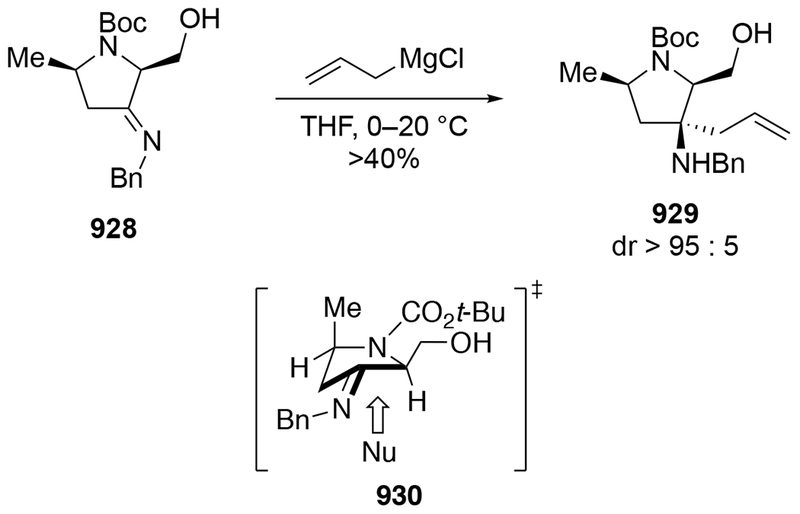

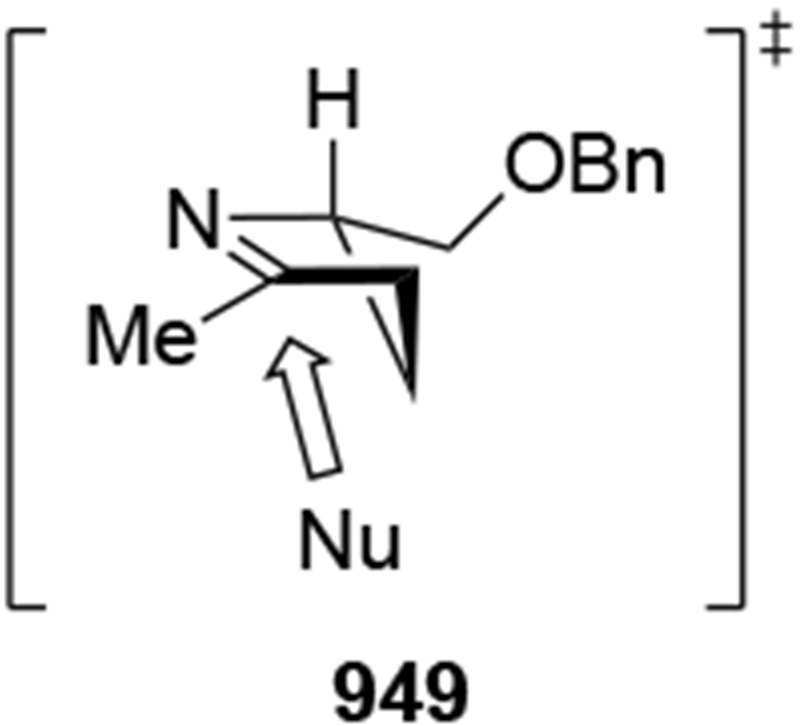

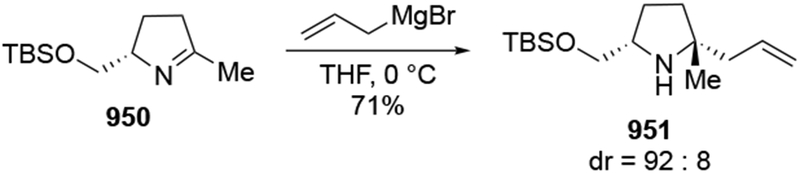

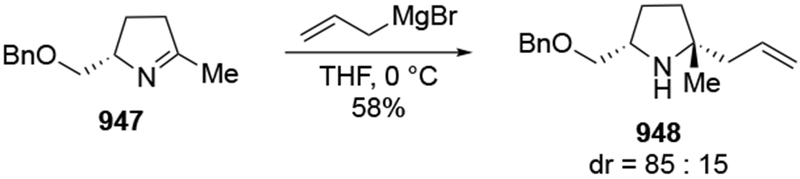

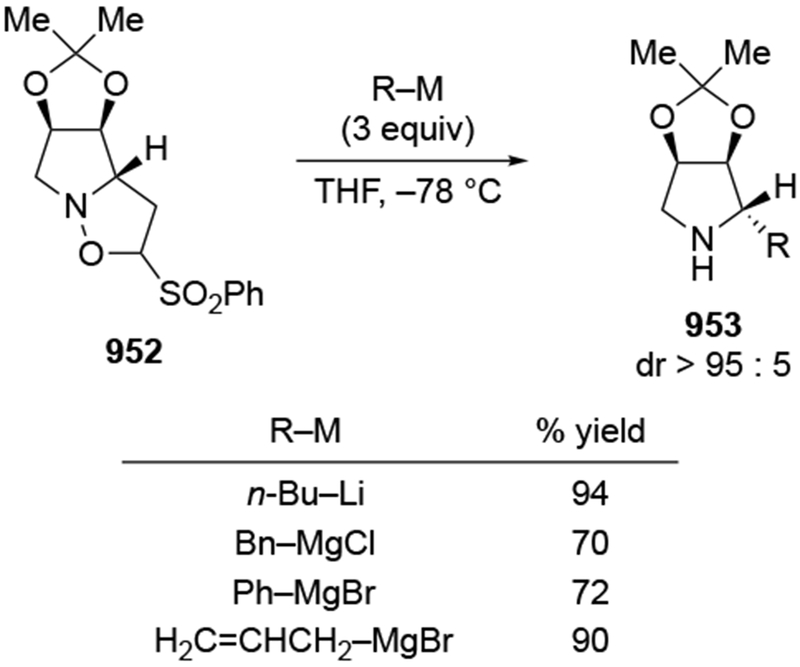

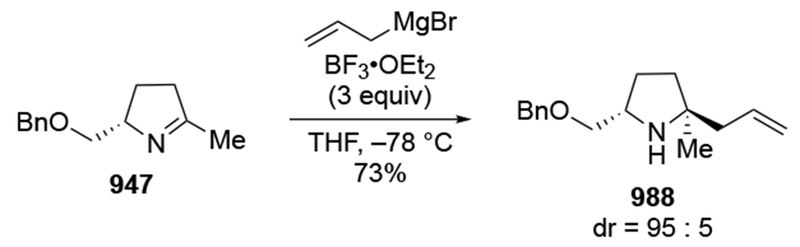

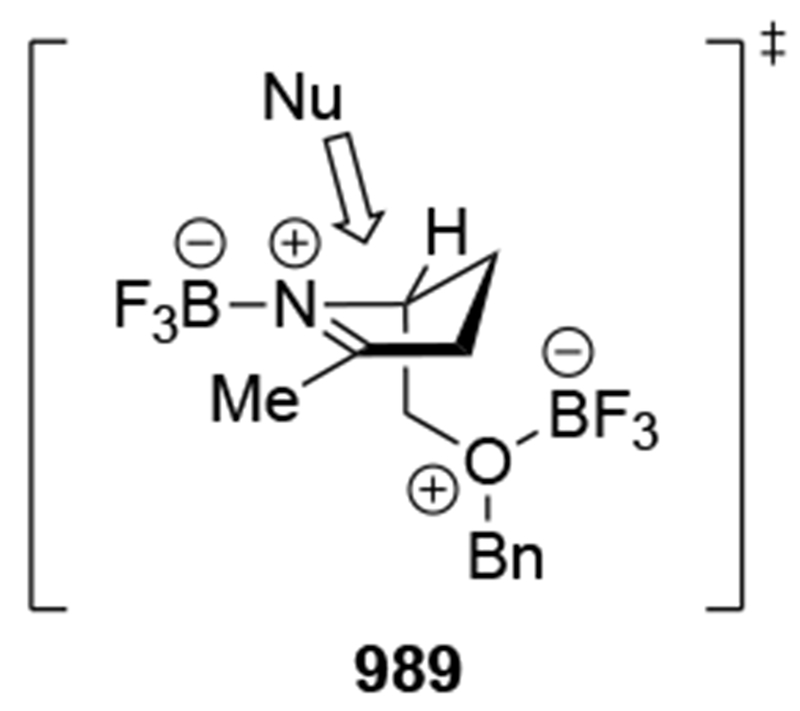

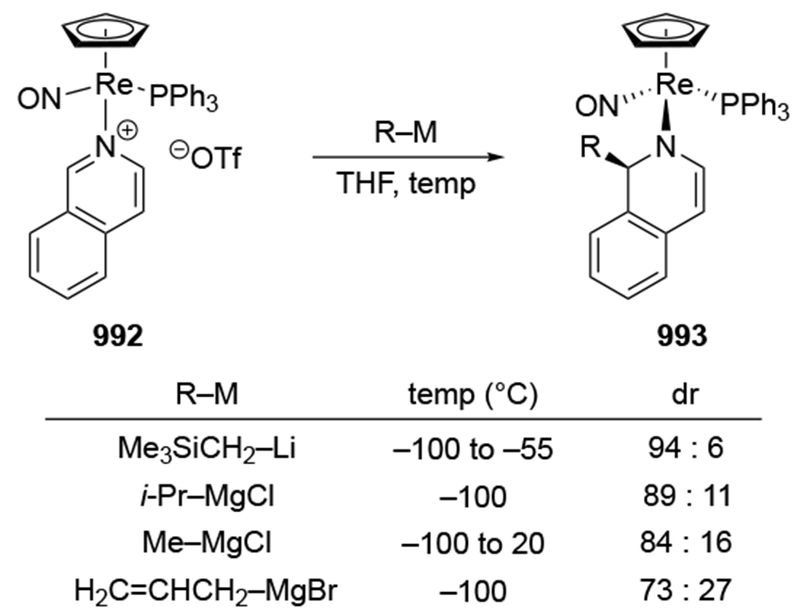

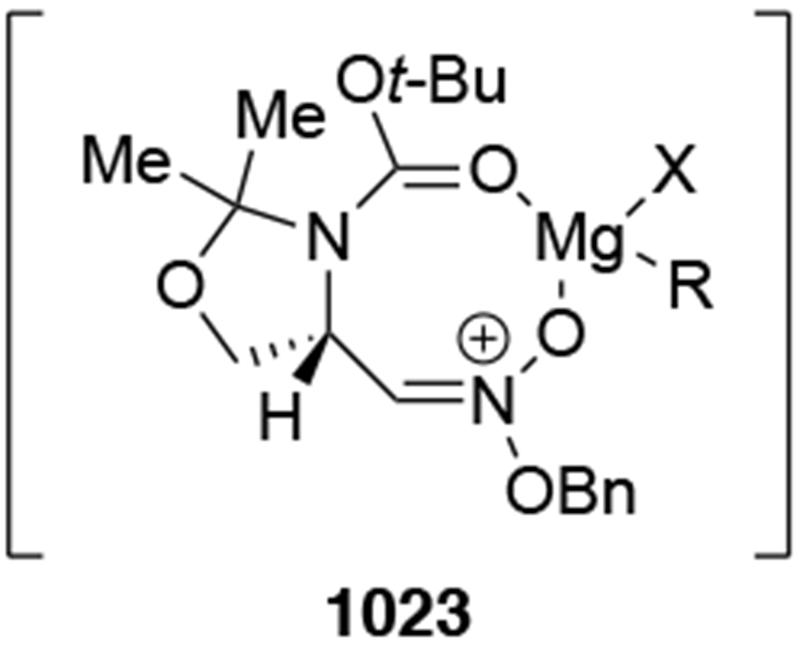

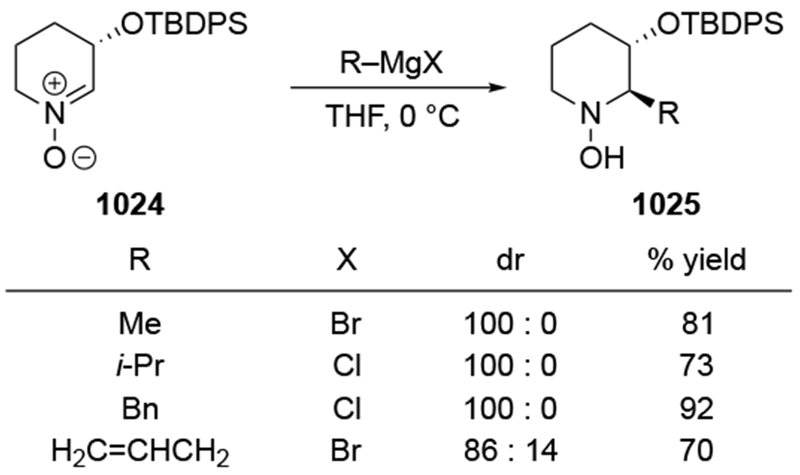

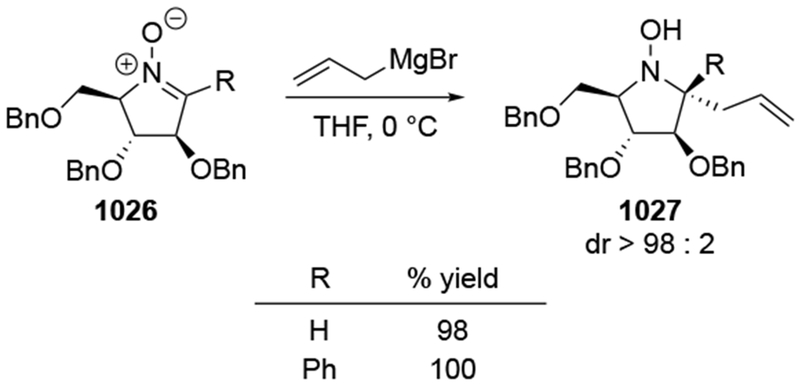

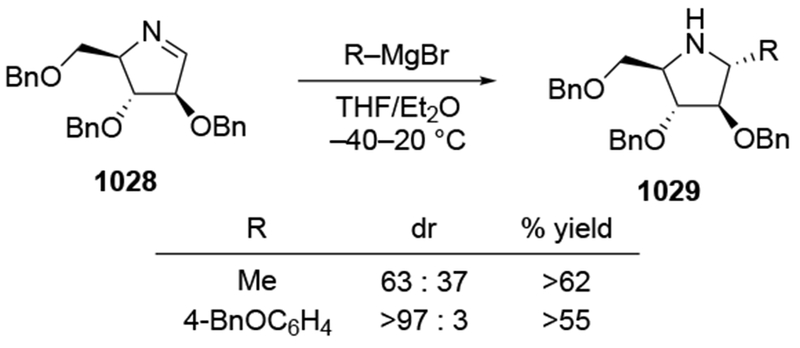

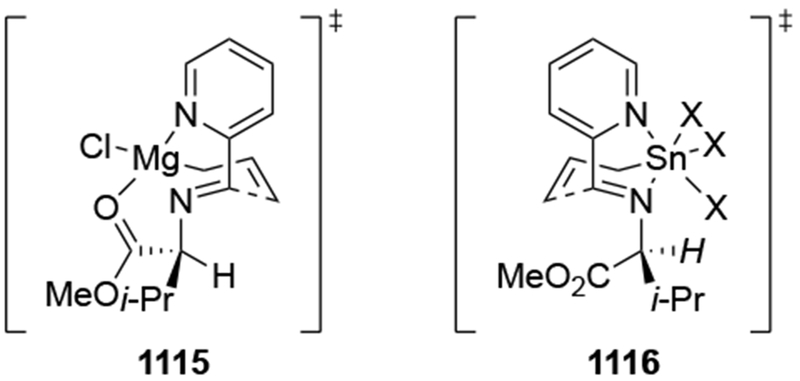

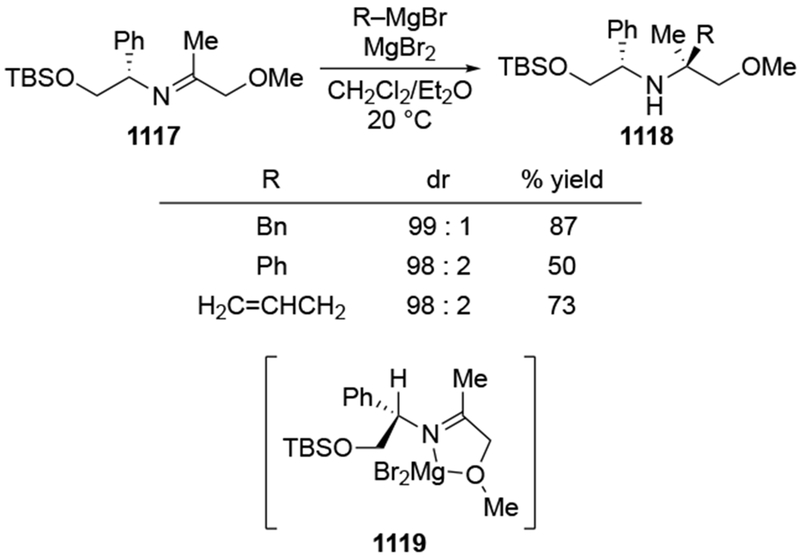

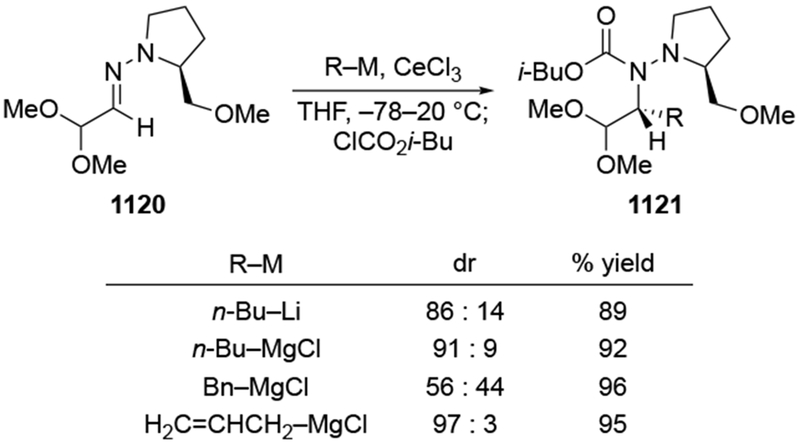

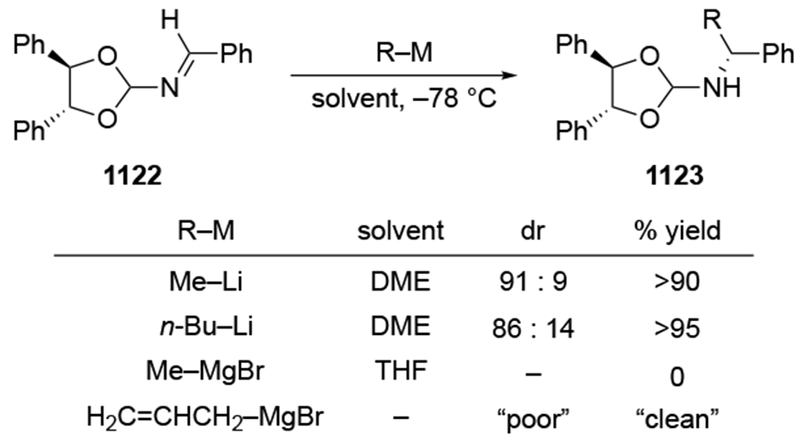

2.5. Additions to Imines

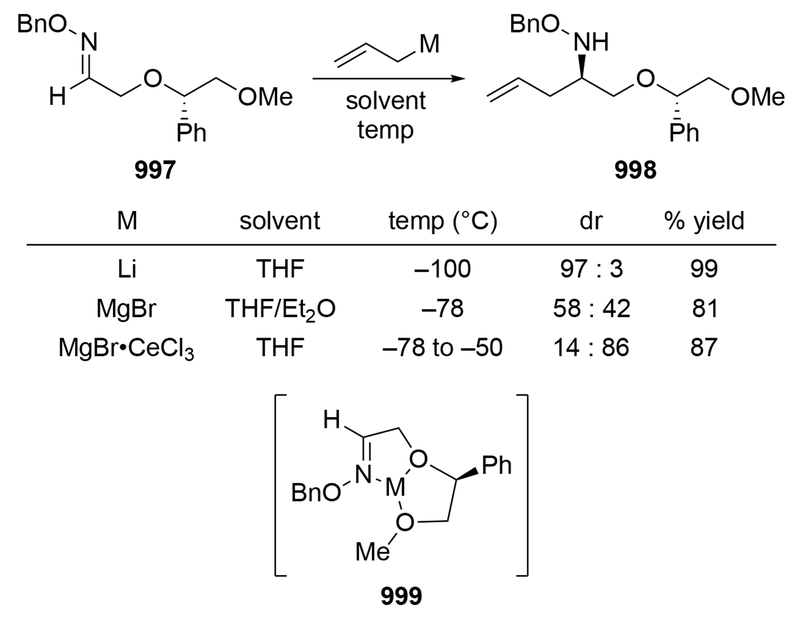

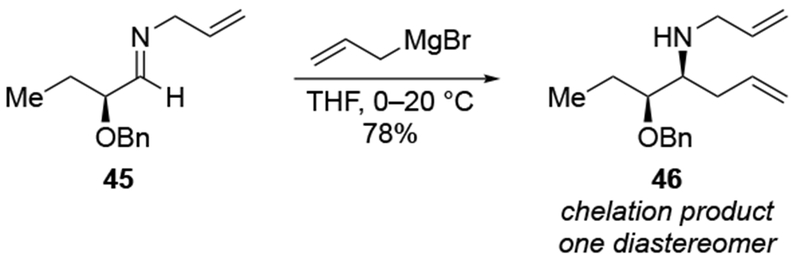

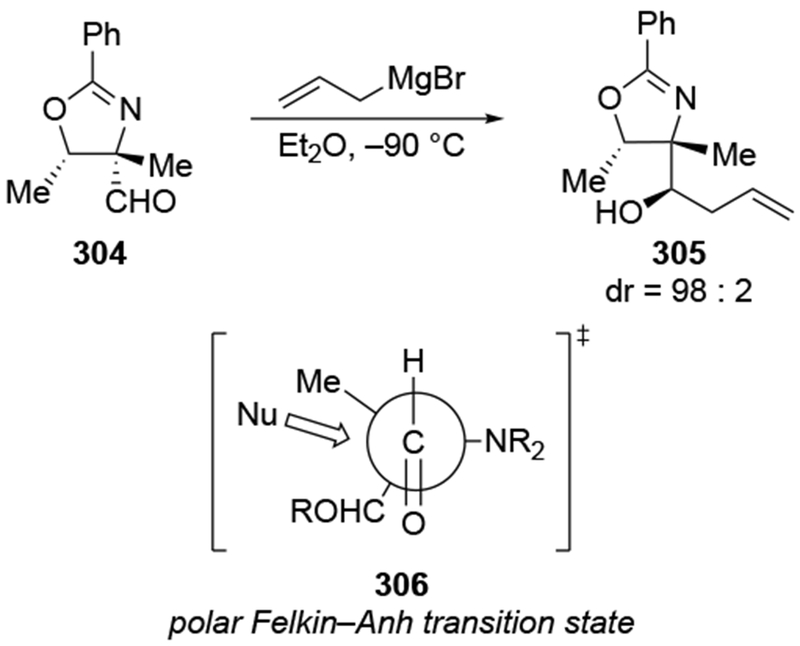

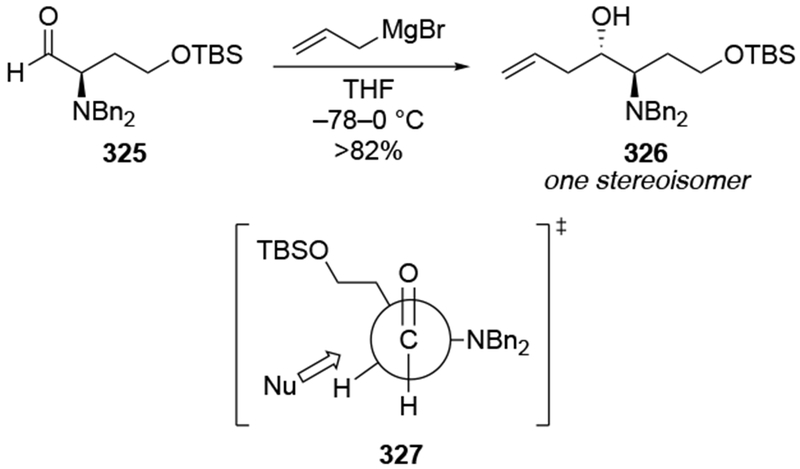

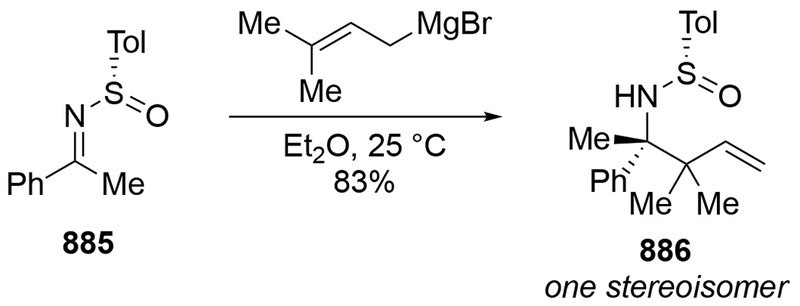

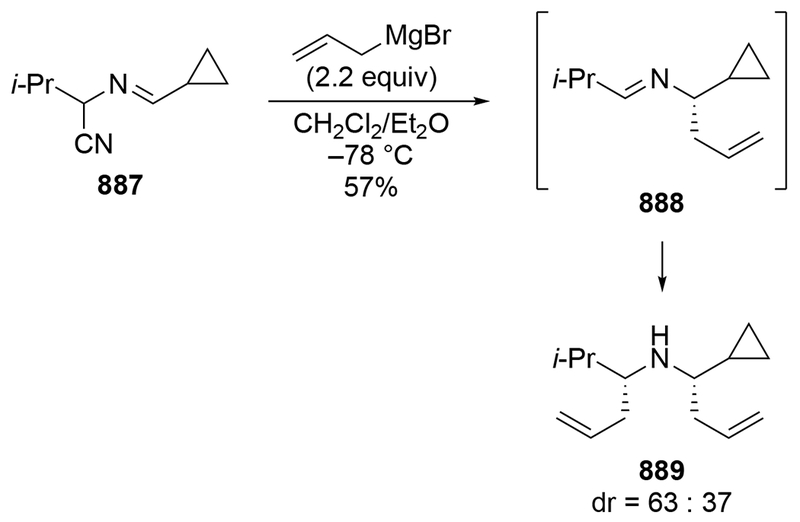

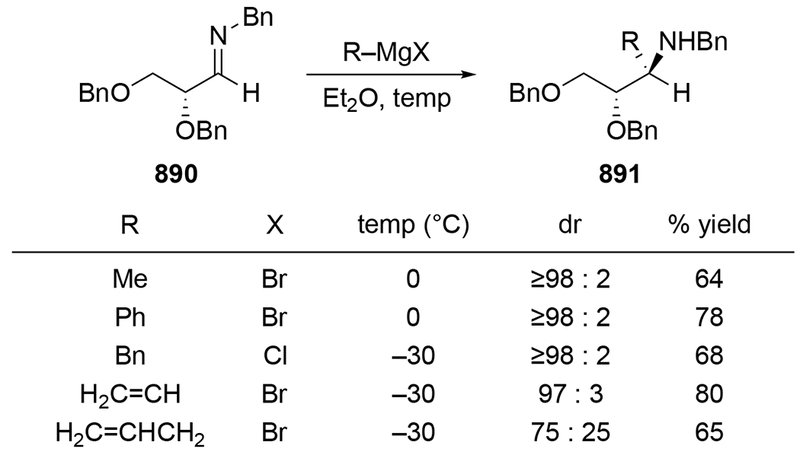

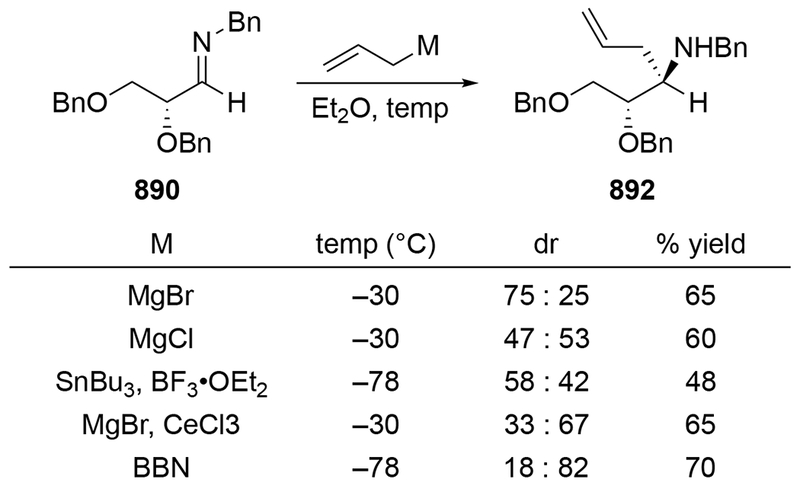

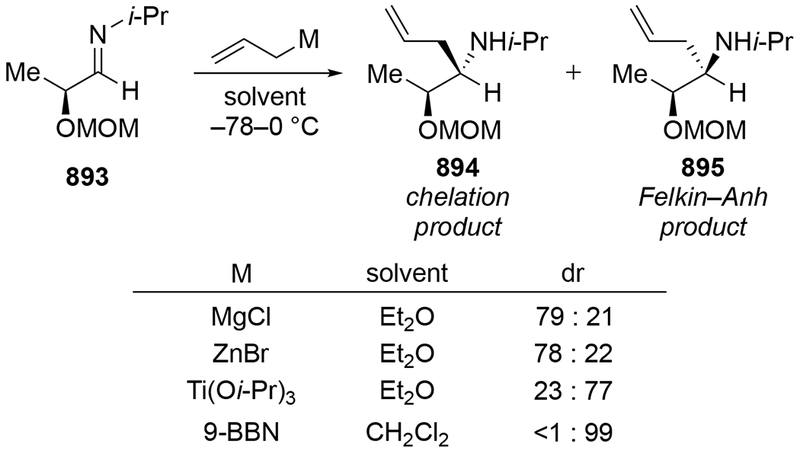

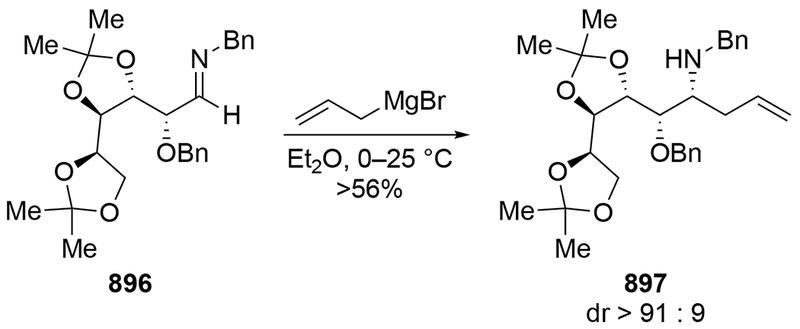

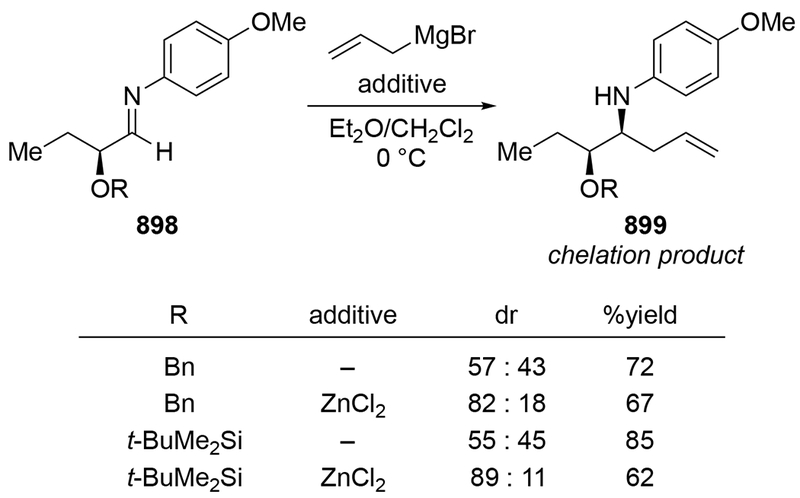

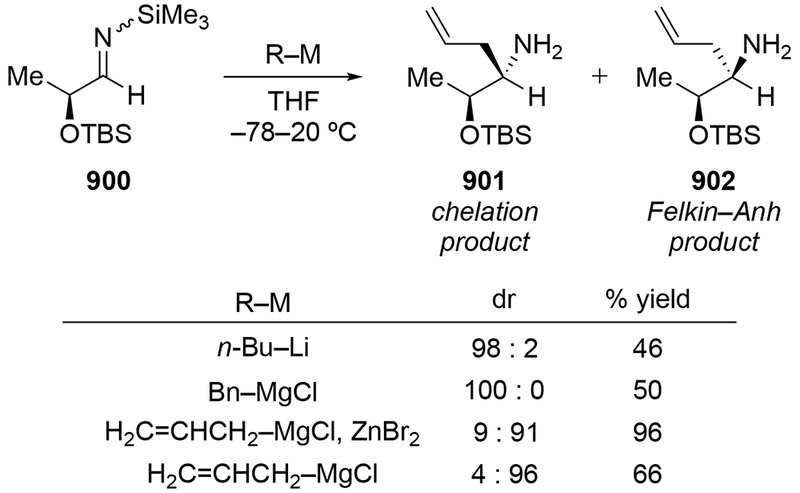

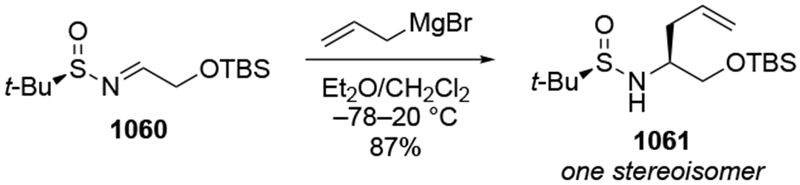

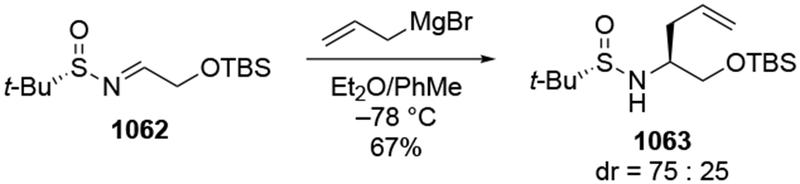

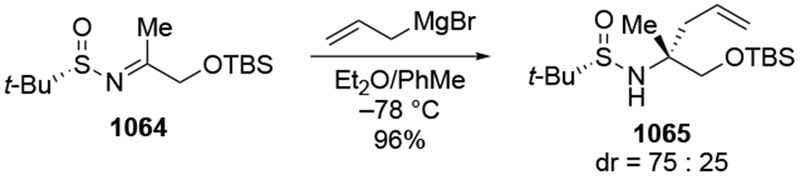

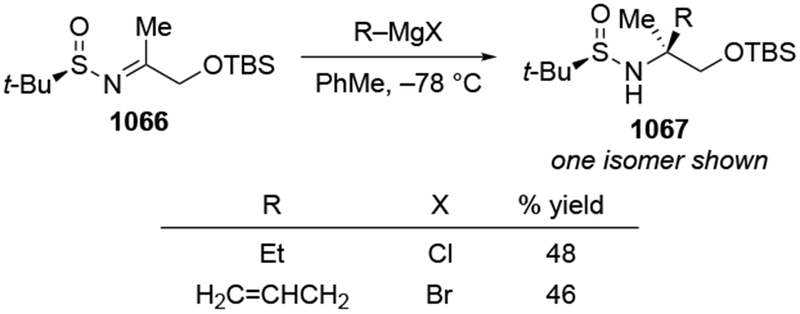

Although this review will focus on reactions of ketones and aldehydes, reactions of allylmagnesium reagents with imines and related electrophilic carbon–nitrogen double bonds will be discussed to provide comparisons. Much less is known about the mechanism of additions of allylmagnesium reagents to imines and other electrophiles with carbon–nitrogen double bonds. It is reasonable to assume that the six-membered ring transition state suggested above (14, Scheme 6) operates for additions of allylmagnesium reagents to imines. The rates of the reactions, however, must be considerably slower than additions to carbon–oxygen double bonds, although additions to activated imines such as N-sulfonylimines, could be even faster.58 As a result, stereochemical models such as the Felkin–Anh model may operate, so there may not be the same unpredictability or loss of stereoselectivity as observed with ketones and aldehydes. For example, addition of allylmagnesium bromide to chiral α-alkoxy aldimine 45 proceeded with high diastereoselectivity (Scheme 1859), as compared to the additions of allylmagnesium reagents to α-alkoxy aldehydes and ketones (as illustrated in Scheme 3).

Scheme 18.

3. Caveats Regarding Stereochemical Models

Stereochemical models are powerful tools that help organic chemists rationalize and predict the stereochemical outcomes of reactions, but they need to be used wisely. Many stereochemical models are predicated on the assumption that the carbon–carbon bond-forming step is also the stereochemistry-determining step. As the rates of bond formation approach the diffusion limit, however, the bond-forming step may no longer determine the stereochemical outcome, and thus the model would no longer apply. Similarly, in some cases, reactions are diastereoselective, but it is not a difference in enthalpy that determines selectivity; differences in entropy in the corresponding transition states control diastereoselectivity.60–62

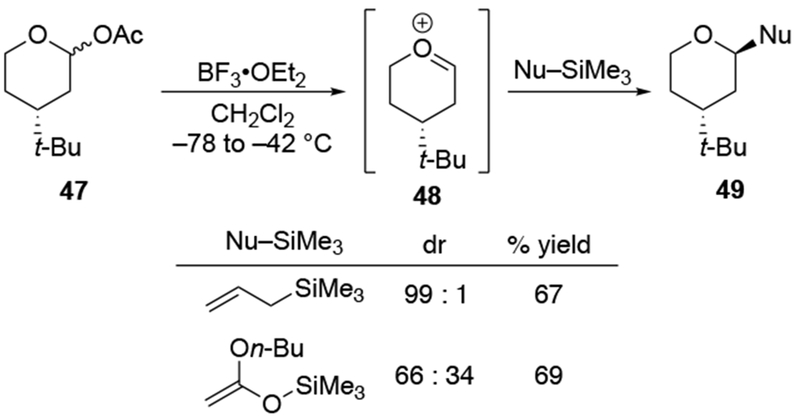

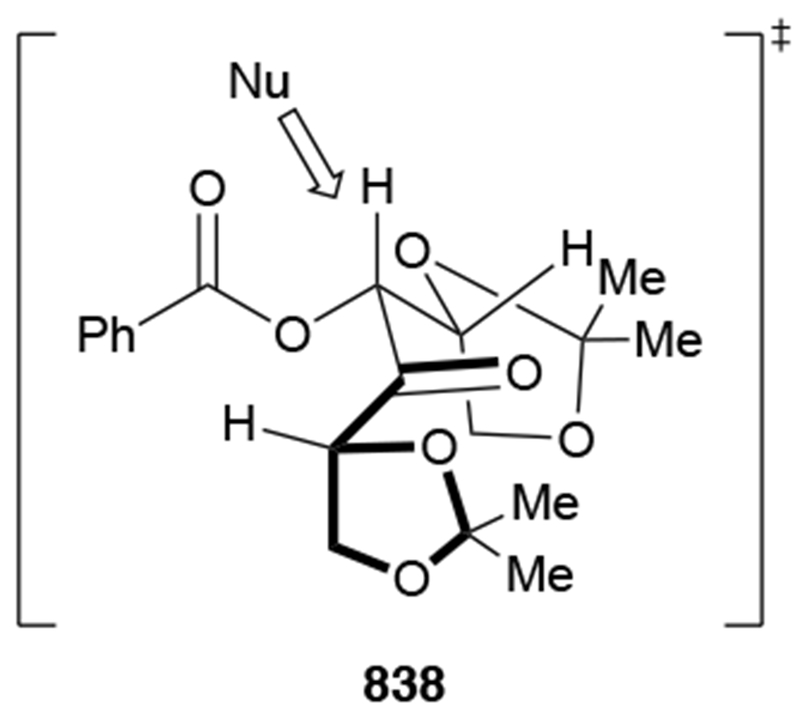

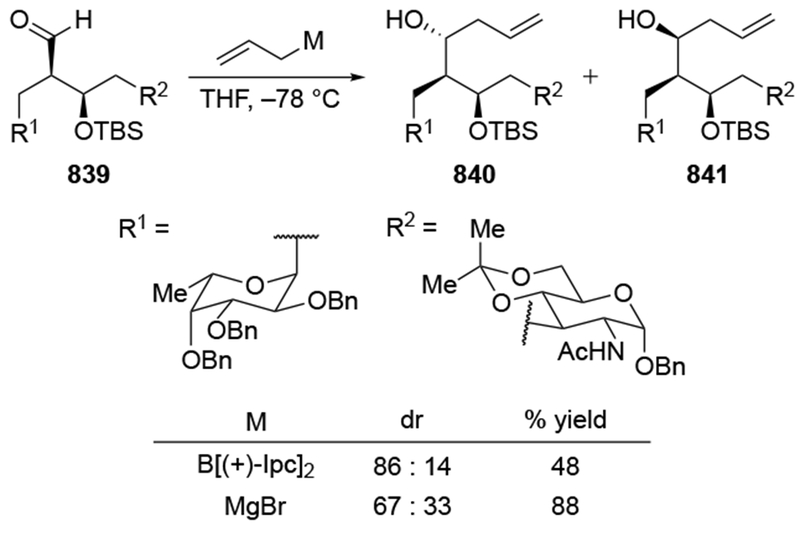

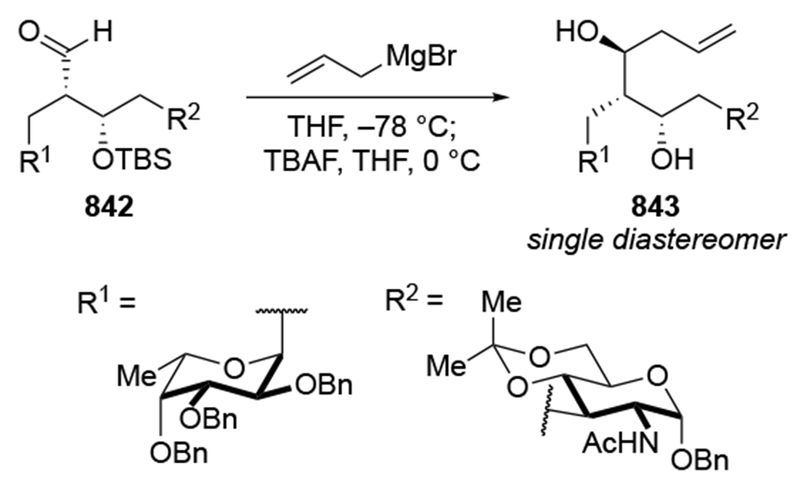

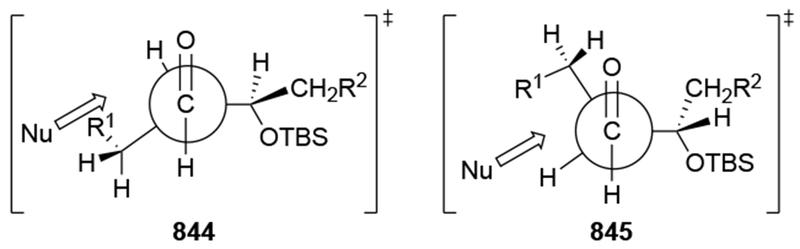

The failures of stereochemical models due to rapid reaction rates have been documented for the reactions of a family of electrophiles closely related to carbonyl compounds, namely oxocarbenium ions. The standard stereochemical models can fail to explain the outcomes of reactions of these electrophiles with some of the most reactive π-nucleophiles, Me3SiCN, and alcohols.34–37 When nucleophiles become more reactive, additions to these highly reactive oxocarbenium ions occur with decreased stereoselectivity (Scheme 19) likely because these reactions occur at rates approaching the diffusion limit and, therefore, the addition step is no longer the stereochemistry-determining step.36 While in this situation the electrophile is the highly reactive partner, the reactions of highly reactive allylmagnesium reagents with carbonyl compounds are likely to be analogous.22 As a result, stereochemical models need to be used wisely to prevent their being applied in settings in which their necessary conditions are not met. Such precise thinking requires discipline on the part of both authors and readers.

Scheme 19.

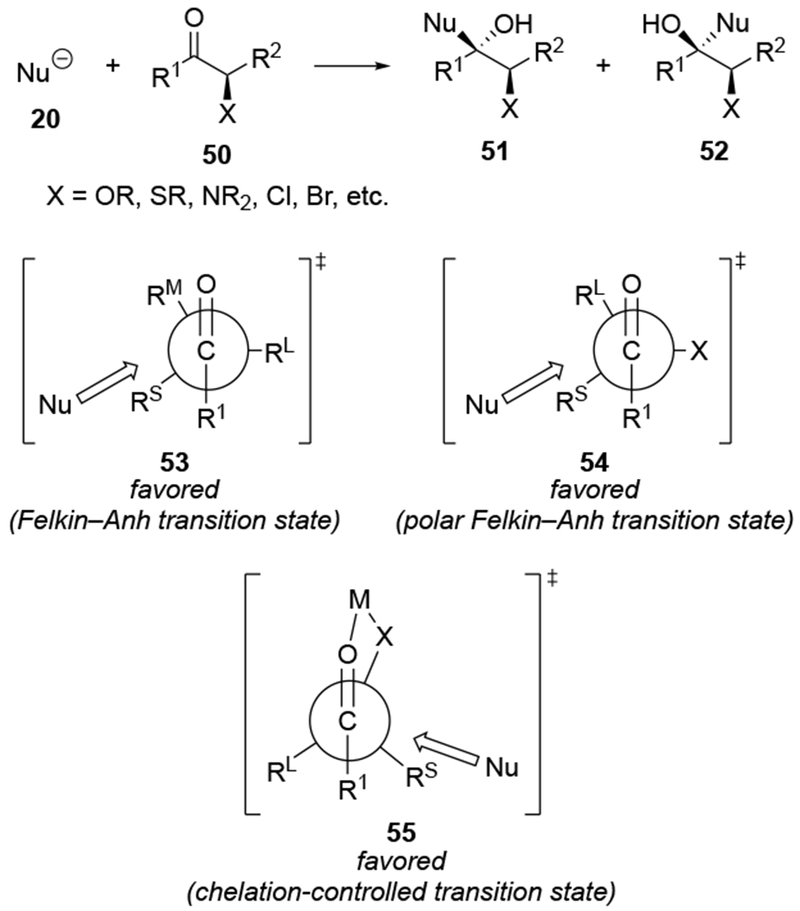

It is also imperative that any explanation of reactivity is logically sound. An example is illustrated for additions of nucleophiles to prochiral carbonyl compounds (Scheme 20). In this case, only two possible stereochemical products can be formed. Each of these products (resulting from addition to the Re or Si face) is generally ascribed to one of two different stereochemical models. The Cram chelate model can be used to explain how one product is formed, whereas the Felkin–Anh model would explain how the opposite stereoisomer would be formed.57 Haphazard use of these models can perpetuate a logical fallacy that confuses cause and effect. One could assume that if the product of chelation-control were favored, then the reaction must have proceeded through a transition state involving chelation-control. Conversely, if the diastereomer expected from the Felkin–Anh model were formed in excess, it could be proposed that the transition state for this reaction would involve the types of conformational preferences and interactions stipulated by that model. Although these explanations are consistent with the outcomes, they do not require that the particular mechanistic pathway described by the stereochemical model is operating.

Scheme 20.

This point is particularly clear for reactions generally analyzed using the Felkin–Anh model. This model is not the only explanation for formation of products with the same configuration. The original Felkin model,63 without the benefit of the insights applied by Anh and Eisenstein,64 also explained the formation of the same diastereomer (and other models have analyzed the same transition state differently65). The Felkin transition state, however, is just one of a number of possible transition states leading to the same product, and, in some cases, other models might be more consistent with the results, even though the same diastereomer of the product was formed.66 As a result, simply because a reaction yields the product expected from the proposed transition state model, that is insufficient to prove that this reaction proceeded through that transition state. Instead, the outcome is merely consistent with that transition state; other transition states could have led to the same outcome.

This issue is also relevant to product ratios. It is common in papers for authors to discuss the origin of the major product of a reaction, but a more sophisticated argument would need to explain the formation of minor products as well. If the major product were formed by, for example, a Felkin–Anh-like transition state, then application of the false logic described above would require that the minor product would necessarily arise from a chelation-controlled transition state. But such an argument is not universally applicable, particularly in cases where chelation would not be possible. Thus, it makes more sense that the minor product occurs from some higher-energy, Felkin–Anh-like transition state or possibly a completely different type of transition state altogether. It is conceivable that the final product ratio might be the result of a statistical average of several different pathways, based on their relative energies, as has been argued for additions to chiral carbonyl compounds67 and oxocarbenium ions68 and for the asymmetric hydrogenation of alkenes using chiral catalysts.69

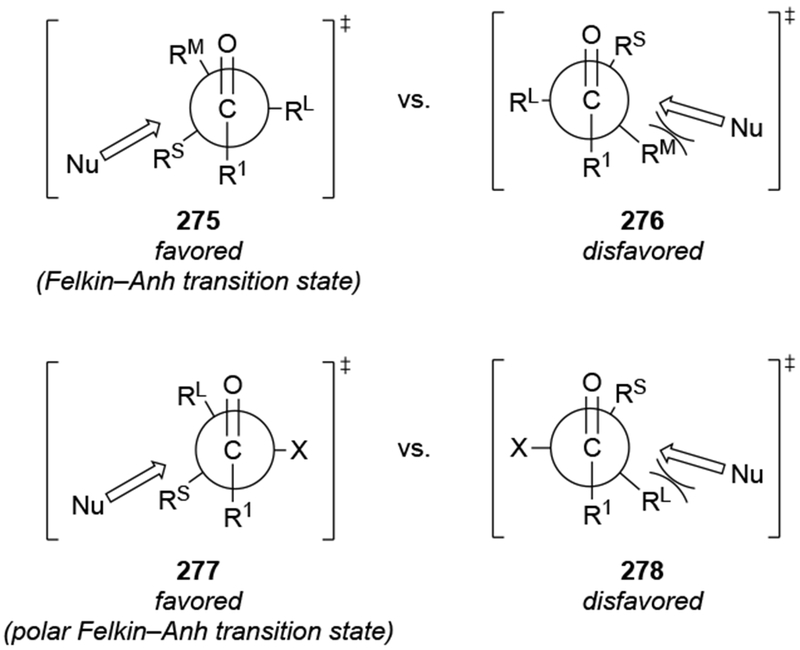

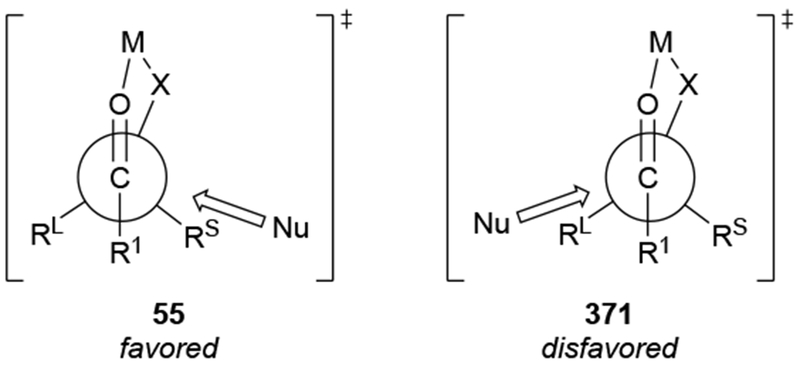

These arguments would also apply to many other modes of stereochemical control. For the purposes of this review, we have analyzed the results of reactions of allylmagnesium halides with chiral carbonyl compounds and imines using four distinct models: the Cram chelation model (as formulated by Eliel and Frye,53–55 although with caveats obtained from more recent results22,70), the Felkin–Anh model, the torsional strain model71 associated with additions to cyclic ketones, and the concept of steric approach control.

This last model deserves additional introduction. Steric approach control addresses which face of a carbonyl group is attacked strictly based upon which face is more sterically accessible.72 What sets this model apart is that it is not analyzed in the same way as the other stereochemical models. Other models consider a number of possible transition states, analyze which transition state would have the lowest energy, and conclude that the reaction occurred through the lowest-energy transition state. Those models, by definition, assume a Curtin–Hammett kinetic scenario73 in which a number of different intermediates (such as encounter complexes and conformational isomers) are rapidly interconverting but the major fraction of molecules follows the lowest-energy pathway among all possible pathways.

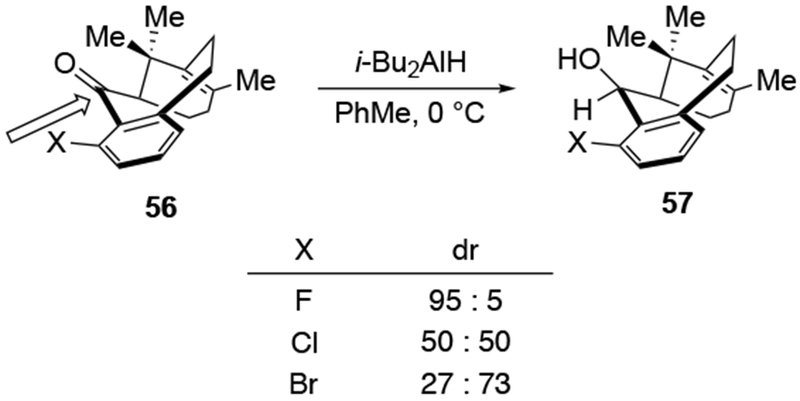

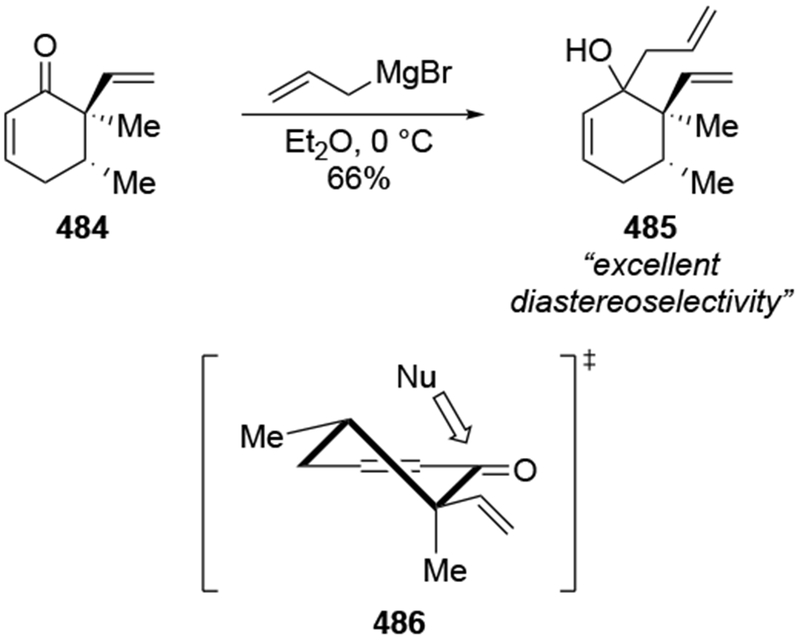

Steric approach control, however, does not assume a Curtin–Hammett kinetic scenario. Instead, it focuses on what steric interactions develop upon bringing a reagent close to the starting material.74,75 Such steric interactions in the transition state can be sufficient to define selectivity. It is correct that steric approach is involved in the other modes of stereocontrol as well (as in determining which face is attacked once chelation had occurred or what interactions occur in the Felkin–Anh transition state once orbital interactions are optimized), but steric approach control requires only steric factors developing between the components of a reaction to explain selectivity. For example, additions to ketone 56 (Scheme 21) have been argued to be the result of steric approach control: the face of the carbonyl group that is preferentially attacked is determined by balancing the steric destabilization that would occur from attack of the opposing faces.76 This balance shifts as the size of the substituent on the nearby aromatic ring increases in size.

Scheme 21.

Although, on one level, it may be a semantic point to discuss steric approach as a separate mode of stereochemical control, it is a useful mode of thinking that enables different possibilities for analyzing stereochemistry. Analysis of the results in Scheme 21 illustrates how steric approach control can be used. Neither the Felkin–Anh model nor the chelation control model can explain these results adequately. It is also difficult to analyze these experiments by considering torsional effects in the transition states of addition, which should be similar for the three halogen-containing substrates. It is reasonable, however, to argue that the exo face of the carbonyl group becomes less accessible as the halogen atom increases in size, causing attack from that face to be slower.

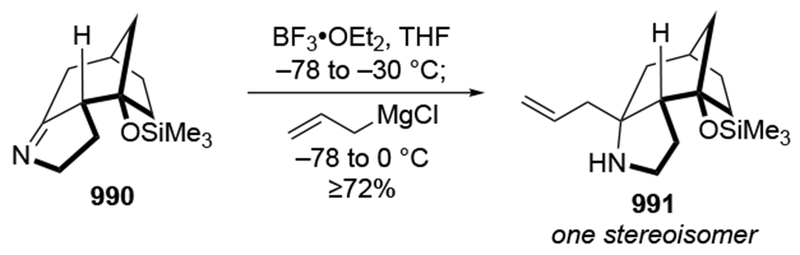

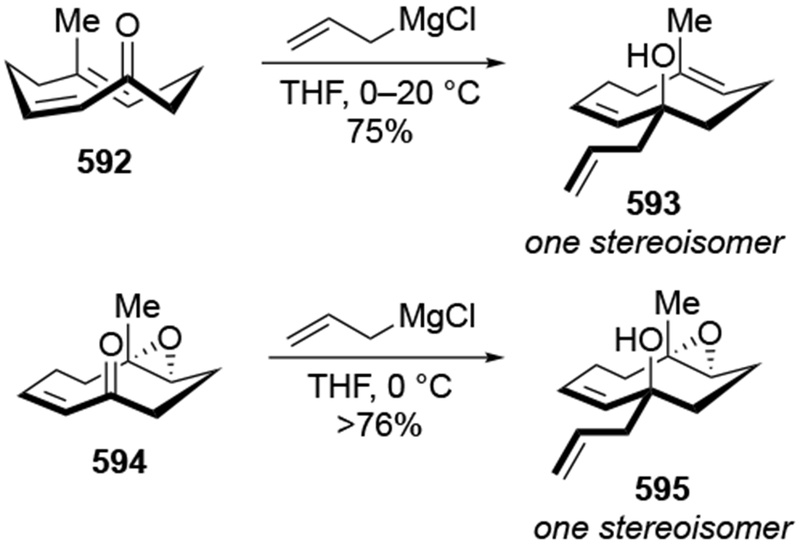

Steric approach control can be a powerful mode of controlling stereochemistry, and it is worth acknowledging it as a possibility with the same importance as Felkin–Anh or chelation control models. A classic example of steric approach control involves the commonly used arguments to analyze approach to a π-system from the convex face of a bicyclic (or multicyclic) system. This “convex vs. concave” mode of analysis is an important stereochemical controlling element with a long history in organic chemistry.83,84

It should not be construed that steric approach control does not consider differences in energies of competing transition states. Rather, it evaluates which face of a molecule is more accessible to reagents. Those interactions are among the many factors that influence selectivity. Steric approach control, such as evaluating convex vs. concave faces, can be of secondary importance compared to other stereochemical control elements.85–87 Nevertheless, the analysis of which face of a π-system is more easily approached by a reagent can be useful when considering reactions in which the approach of the reagents (i.e., diffusion), and not the transition state for bond formation, is important for stereoselectivity. It is precisely this situation that may occur in the case of additions of allylmagnesium reagents to carbonyl compounds. The stereoselectivity of these reactions is no longer controlled by transition states that include bond formation, so, as rates approach the diffusion limit, transition-state models will no longer operate.38

4. Diastereoselectivities of Reactions with Carbonyl Compounds that Can Chelate

4.1. Stereochemical Control by the Chelation-Control Model

Chelation control is a commonly used method for controlling the stereochemistry of additions to carbonyl compounds. This approach is most useful in the case of α-substituted carbonyl compounds (particularly α-alkoxy ketones), but chelation can be observed with more remotely substituted substrates. In comparison, α-alkoxy aldehydes react with lower selectivity than ketones do, likely because of the generally higher reactivity of the aldehyde functional group.17,28,88

Chelation-controlled selectivity was not intended to denote an electronic difference between chelated and non-chelated transition states. As originally formulated, the model explained the high selectivity based upon the presence of a rigid intermediate with sterically differentiated faces in which the α-heteroatom and the carbonyl group are chelated to the organometallic reagent (Scheme 22).67 Approach to one face of the chelate 55 is sterically blocked by a larger substituent (in this case, Rl), so attack occurs from the less sterically hindered face. As a result, chelation control is a form of steric approach control: the difference in energy between the transition states of addition to one side of the chelated intermediate compared to the other is caused by the different steric destabilizations that develop between the incoming nucleophile and the substrate.

Scheme 22.

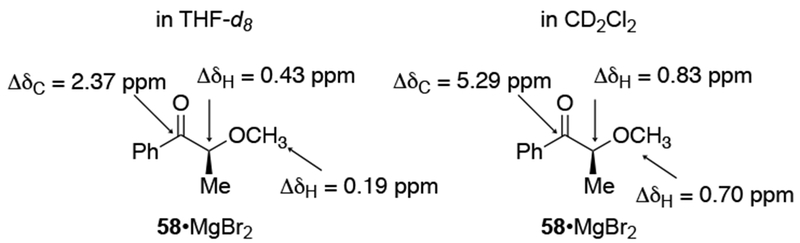

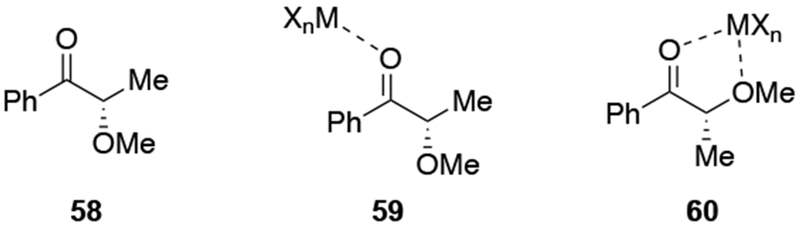

Chelation-controlled selectivity is not so simple to analyze, however. The contributions of Eliel, Frye, and co-workers are particularly important to the understanding of this model.53–55 Their studies revealed that chelated intermediate 58 is likely not the major intermediate present in solution in THF, one of the most common solvents used for reactions involving organomagnesium reagents. 1H NMR spectroscopy of ketones in the presence of MgBr2•(OEt2)2 (as a surrogate for the organomagnesium nucleophile) demonstrated that the chelated intermediate is a minor component in ethereal solution (Scheme 23).

Scheme 23.

Solvent choice can make a significant difference in the quantity of the chelated intermediate. For example, complexation was much more pronounced in CD2Cl2 compared to THF-d8, as evidenced by the significant differences in chemical shifts observed upon addition of MgBr2 to an α-alkoxy ketone (Scheme 23).22 Other metal salts, such as EtZnCl, also formed significant quantities of chelated species with α-silyloxy ketones in CD2Cl2.89

The origin of stereoselectivity in systems where chelation is possible is more complex than just recognizing that chelation can occur. The difficulty is caused by the fact that many intermediates could be present in solution, such as those shown in Scheme 24, but the chelated intermediate, a minor component, must be more reactive than other species. Eliel, Frye, and co-workers measured reaction rates for additions of Me2Mg to ketones that could and could not form chelated intermediates.53,54 For α-methoxy ketones, reaction rates were up to 2,000 times higher than for ketones without a chelating group (Scheme 25).53 As a result, the chelation-control model is an example of a Curtin–Hammett kinetic scenario:73 a minor amount of a highly reactive species (i.e., the chelate 60) must undergo reaction with the organometallic reagent faster than any other species in solution reacts. Furthermore, the chelated carbonyl compound must react much faster considering the generally high stereoselectivities observed. It was suggested that the chelated carbonyl compound was more reactive because the carbon–carbon bond formation is unimolecular instead of bimolecular,54 a suggestion that has been supported computationally.90

Scheme 24.

Scheme 25.

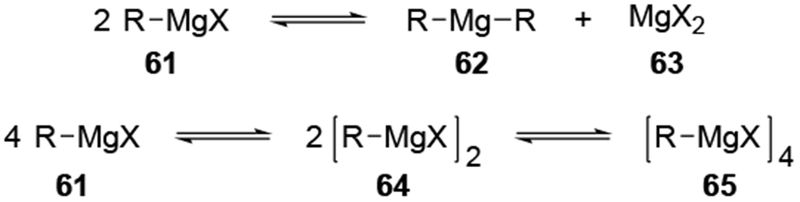

This conclusion, however, may only be the case for the monomeric dialkylmagnesium species examined in those studies. The structures of the more commonly used organomagnesium halides are likely to be more complicated (Scheme 26). The Schlenk equilibrium, which exchanges ligands on magnesium atoms, enables different types of organomagnesium reagents to be the nucleophilic species.91 Grignard reagents also readily form aggregates, depending on the solvent, concentration, halide, and nature of the organic group, all of which would complicate this picture significantly.91,92 Although the aggregation state of organomagnesium halides vary widely, multimeric species are plausible intermediates in which there is a synergy between the complexation of the carbonyl compound to one equivalent of a magnesium species and a second magnesium species.93–95 This type of mechanism parallels observations with organozinc reagents, which show chelation-controlled selectivity in the presence of dimeric zinc species.96

Scheme 26.

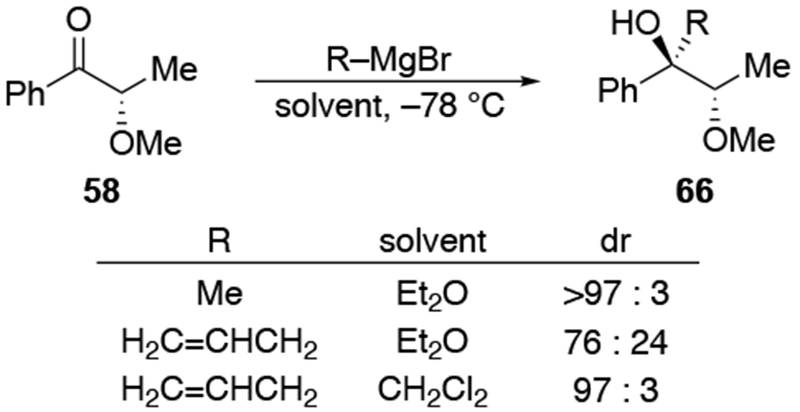

As suggested above, the use of non-ethereal solvents can change the stereochemical outcome dramatically. For example, whereas addition of methylmagnesium halides followed the chelation-control mode in ethereal solvents, addition of allylmagnesium reagents were generally poorly selective, as would be expected from a reaction whose stereochemistry-determining step was diffusion (Scheme 27).22 By contrast, additions in the non-complexing solvent CH2Cl2 were highly diastereoselective. In non-ethereal solvents such as CH2Cl2, the chelated form of the carbonyl compound was demonstrated to be more favored compared to ethereal solvents (Scheme 23),22 which might be expected to increase the amount of product formed from this intermediate.

Scheme 27.

Other experiments, however, show that the observation of highly diastereoselective reactions with allylmagnesium halides in CH2Cl2 cannot be explained by the chelation control model as currently defined. That model includes the stipulation that chelation is accompanied by acceleration of the reaction rate,53,54 but no chelation-induced rate acceleration was observed for allylmagnesium halides (Scheme 28).22 The chelation-control model describing additions of Grignard reagents to α-alkoxy ketones can therefore be broadened to state that the product arising from addition to the favored face of the chelated intermediate should be the major product of a reaction in either of two scenarios: a small amount of the chelated intermediate is the most reactive species in solution, or the chelated intermediate must be the major species in solution. Therefore, the nature of the solvent needs to be considered in any analysis of additions of organometallic nucleophiles to ketones capable of chelation.

Scheme 28.

The nature of stereocontrol through chelation is likely even more complicated. One final example reinforces the general caveats noted about the stereochemical models used by organic chemists (Section 3). In studies of hydride reduction reactions, it was demonstrated that the product expected from chelation control was formed without any evidence that it was either a result of a highly reactive chelated intermediate or that the major species in solution was a chelated intermediate.70 Therefore, it is important to remember that all that is required for stereoselectivity is that the diastereotopic faces of the carbonyl compound are sufficiently differentiated.

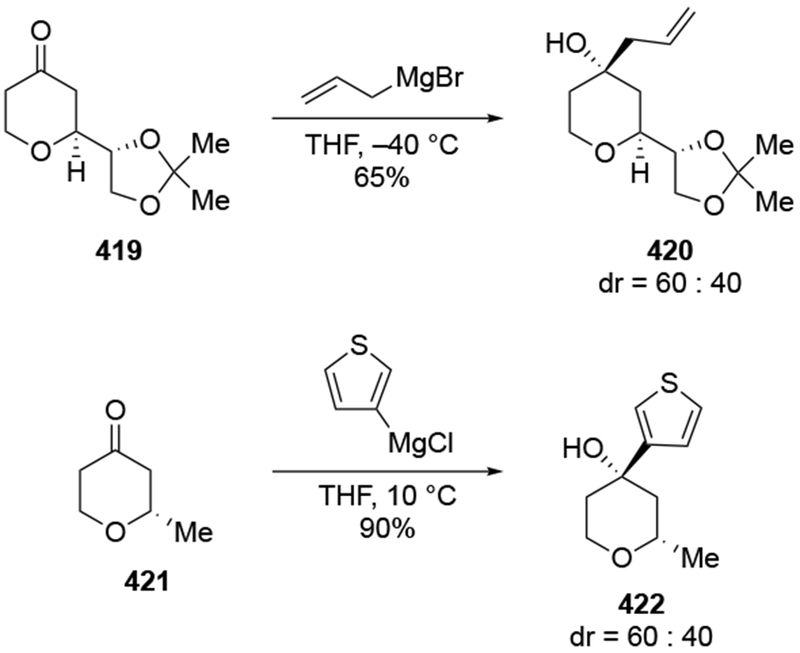

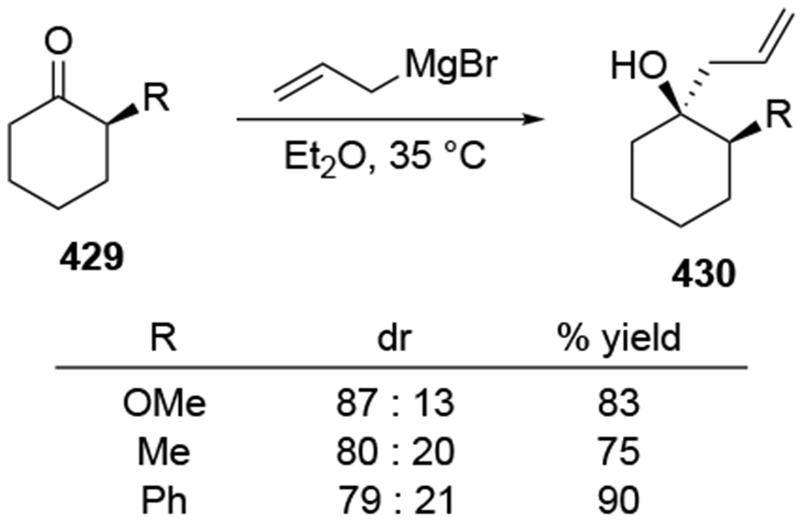

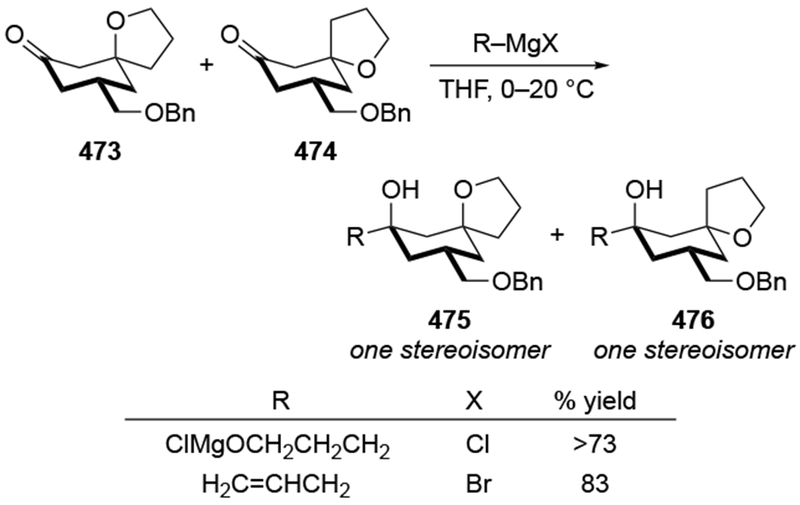

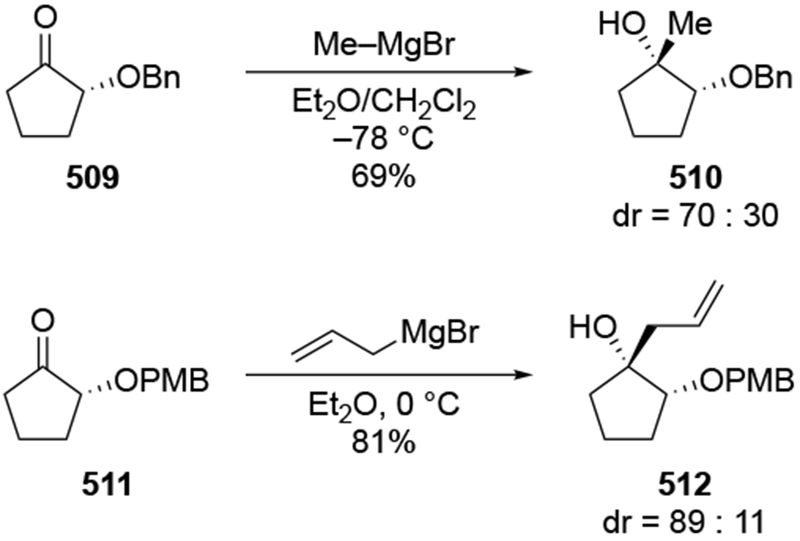

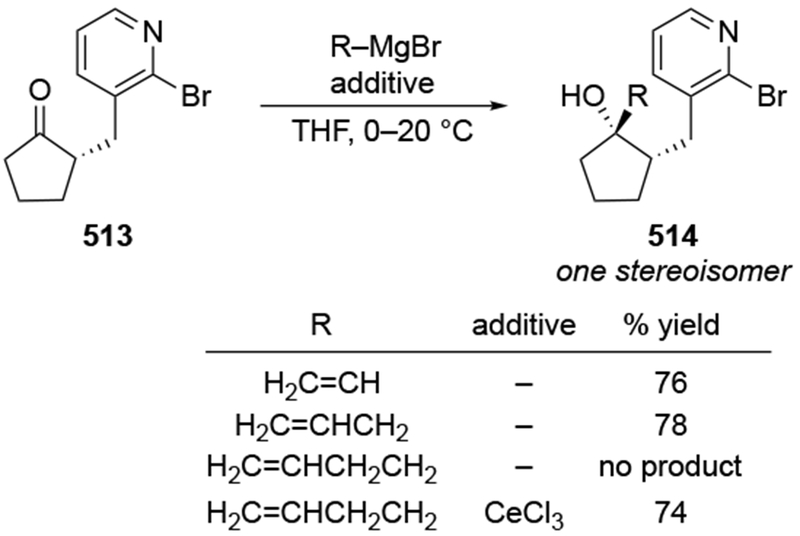

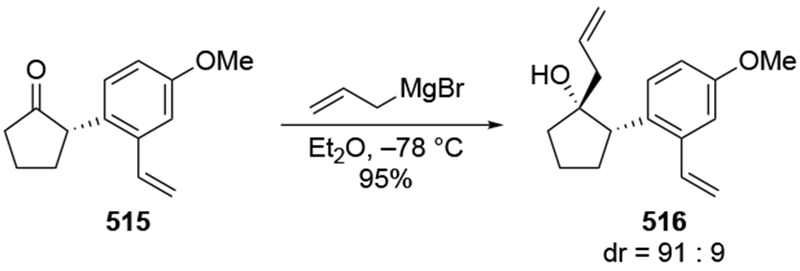

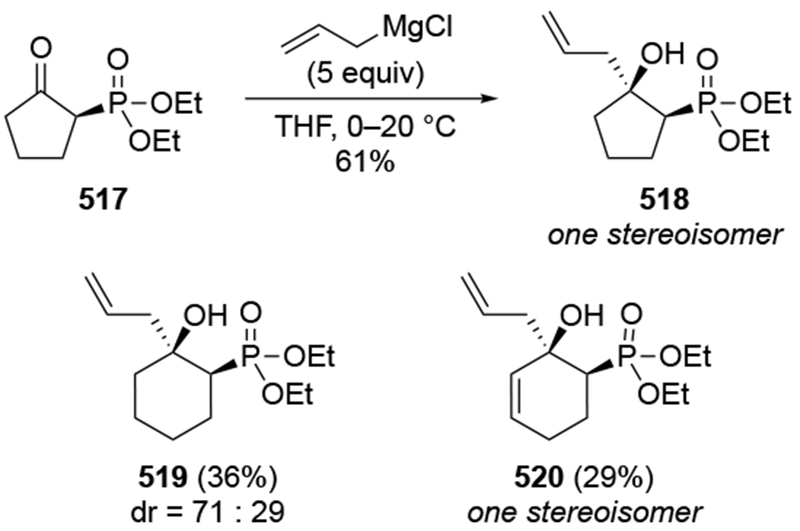

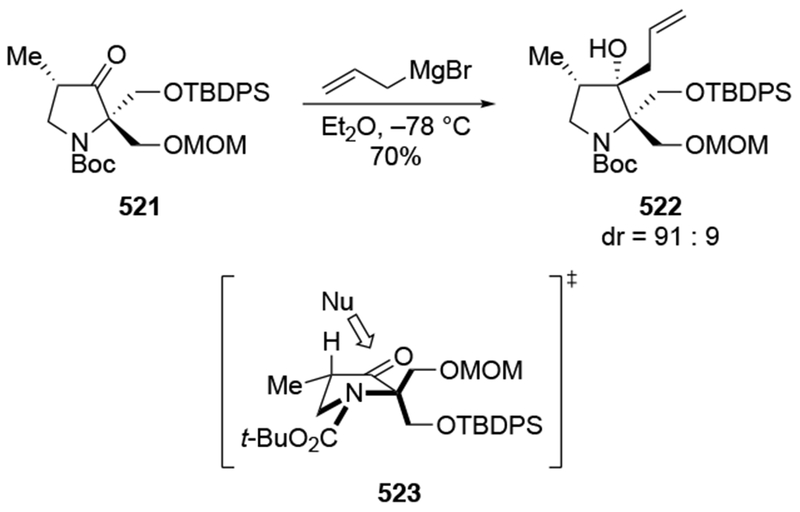

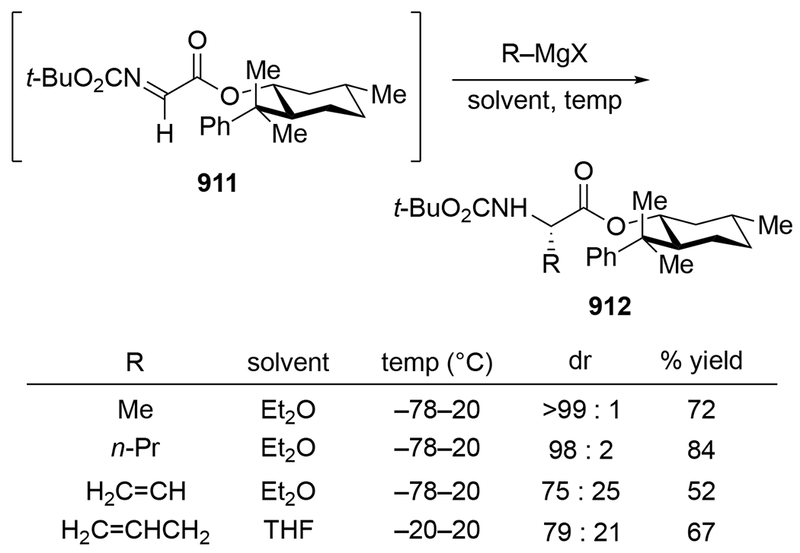

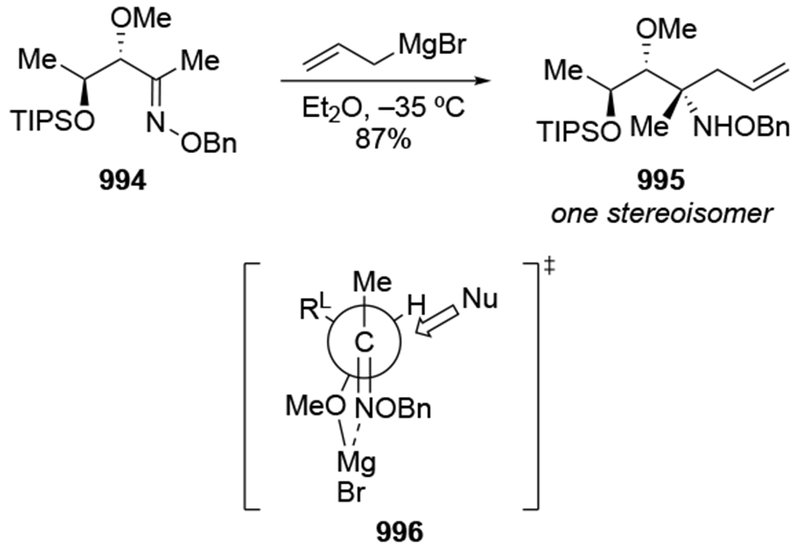

4.2. Additions of Allylmagnesium Reagents to α-Substituted Carbonyl Compounds Capable of Chelation

Among the more consistent problems in using allylmagnesium reagents is their general reluctance to engage in chelation-controlled additions. This point is illustrated in Scheme 3 in the Introduction section. The striking difference in diastereoselectivity can be attributed to the high rates of additions of allylmagnesium reagents, which approach the diffusion rate limit. In this section, examples of chelation-controlled and non-chelation-controlled additions are documented. These examples will focus on reactions of allylmagnesium reagents; the studies of chelation-controlled additions by other organometallic reagents such as organotitanium or organozinc reagents have been reported elsewhere.97–100

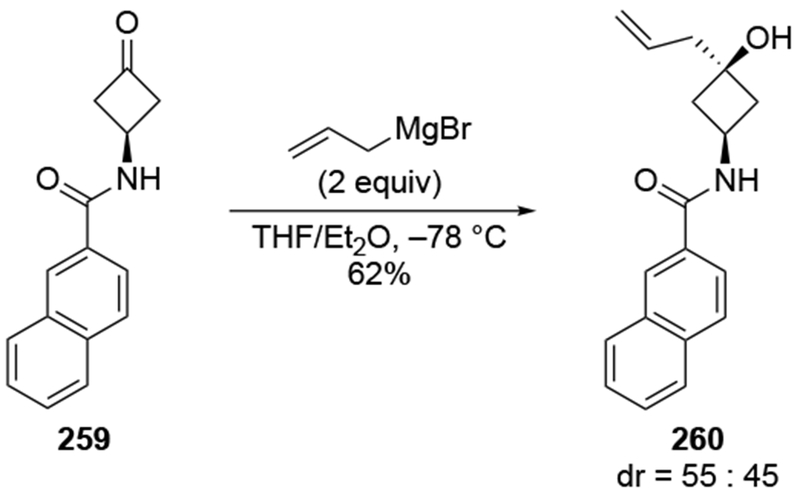

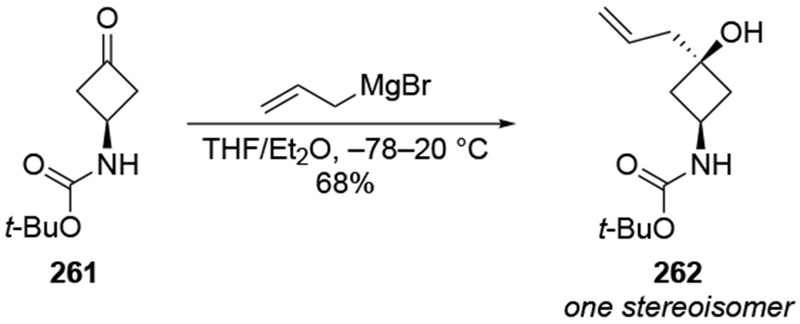

4.2.1. Additions to Acyclic Ketones and Aldehydes

4.2.1.1. Additions to α-Alkoxy Ketones

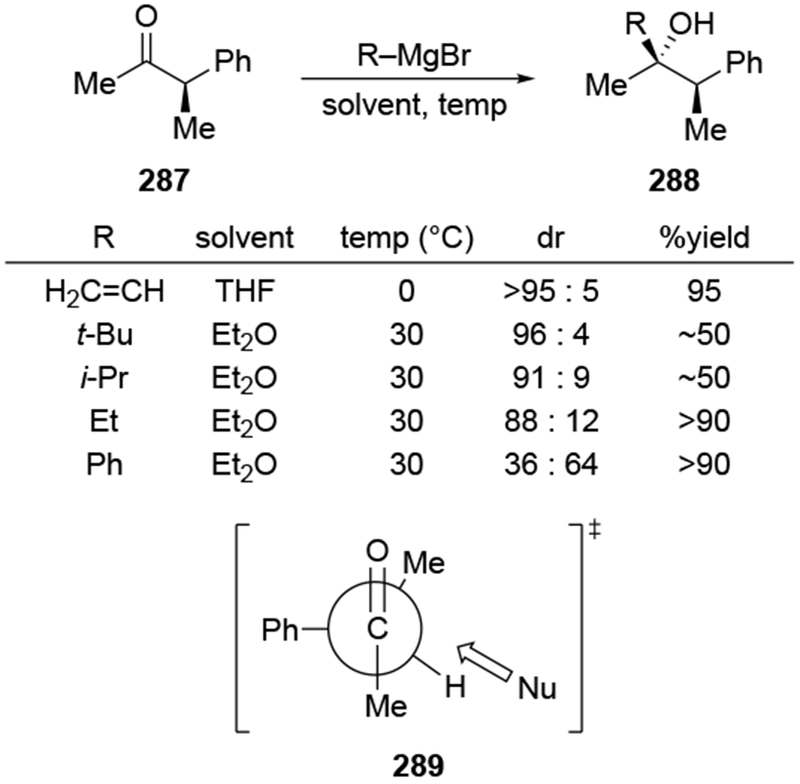

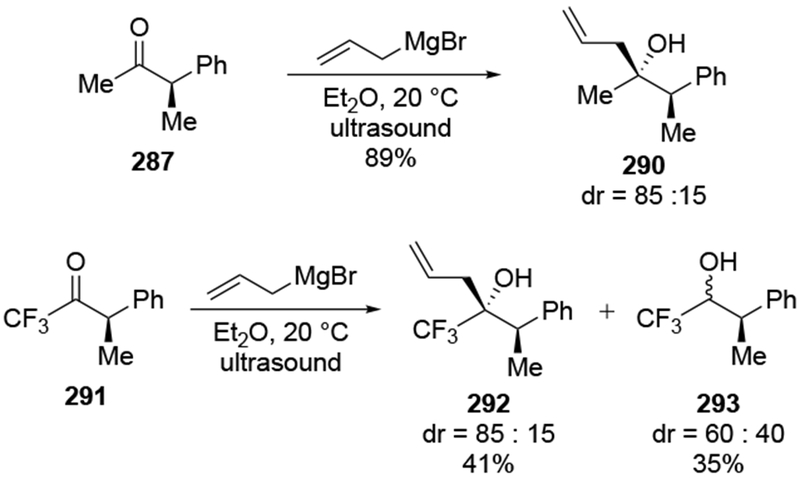

As noted in the Introduction section (Section 1), additions of allylmagnesium reagents to chiral, α-alkoxy ketones are generally unselective. The examples shown in Scheme 29 below are illustrative.4,101 Addition of an alkyllithium reagent preferentially gave the Felkin–Anh product (albeit with low selectivity), likely because chelation to the lithium atom is generally weaker.102,103 On the other hand, most organomagnesium reagents reacted with high chelation-controlled stereoselectivity. Among the organomagnesium reagents investigated, however, only allylmagnesium bromide reacted with no stereoselectivity. Similar observations were made using other protecting group schemes.104

Scheme 29.

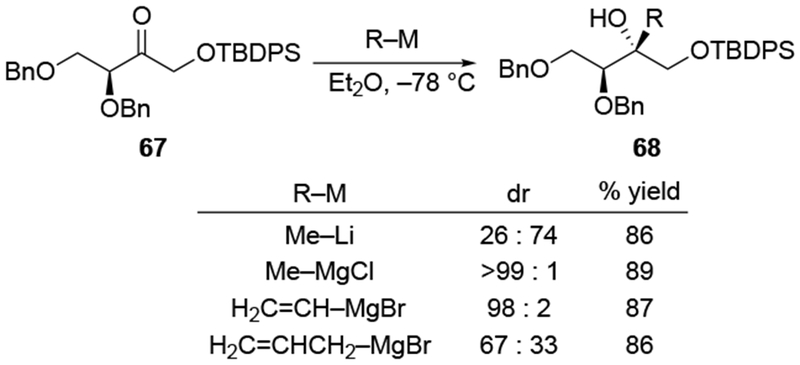

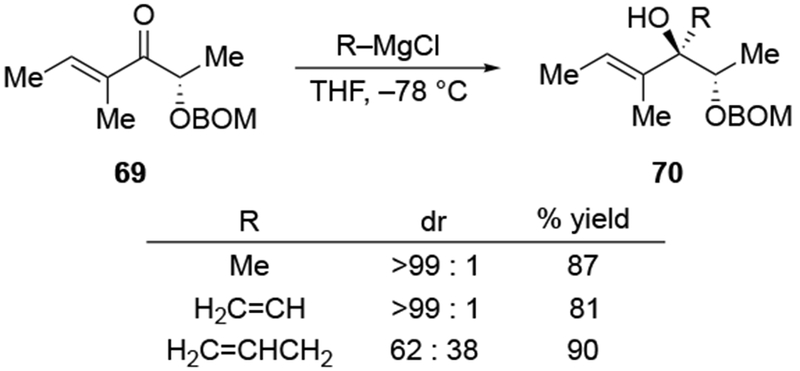

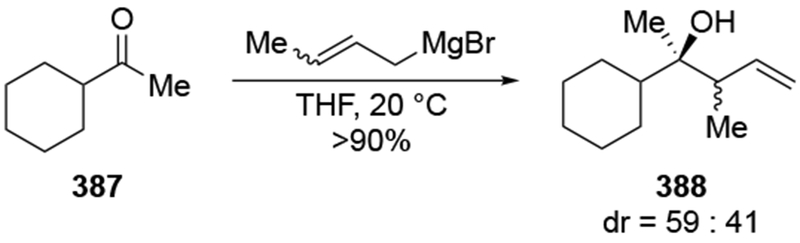

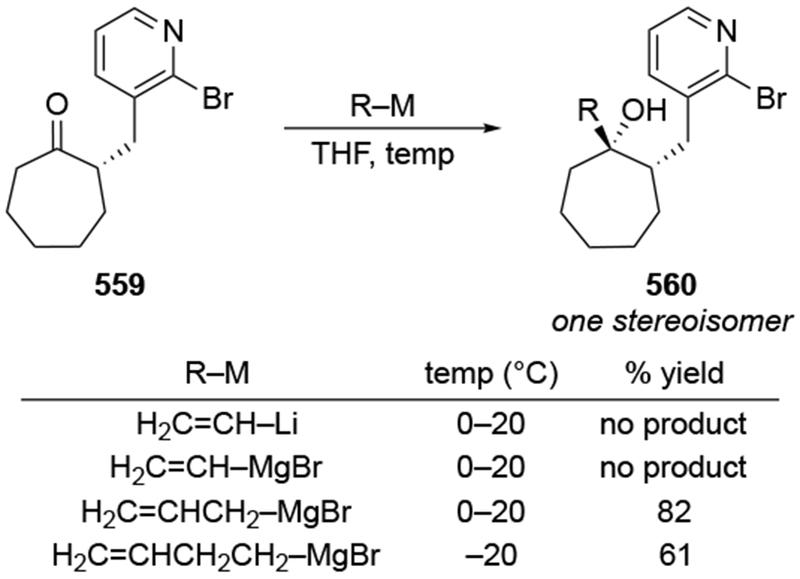

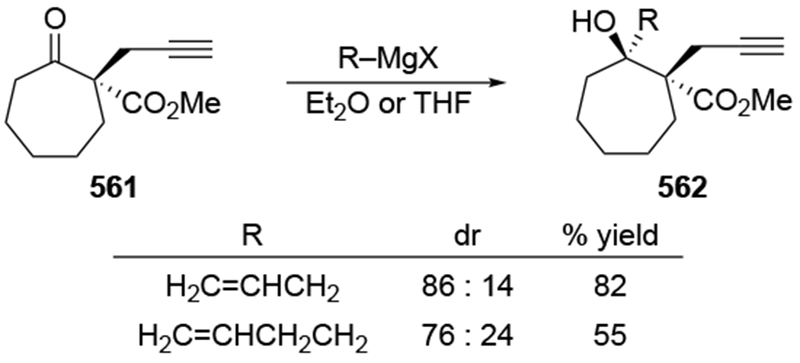

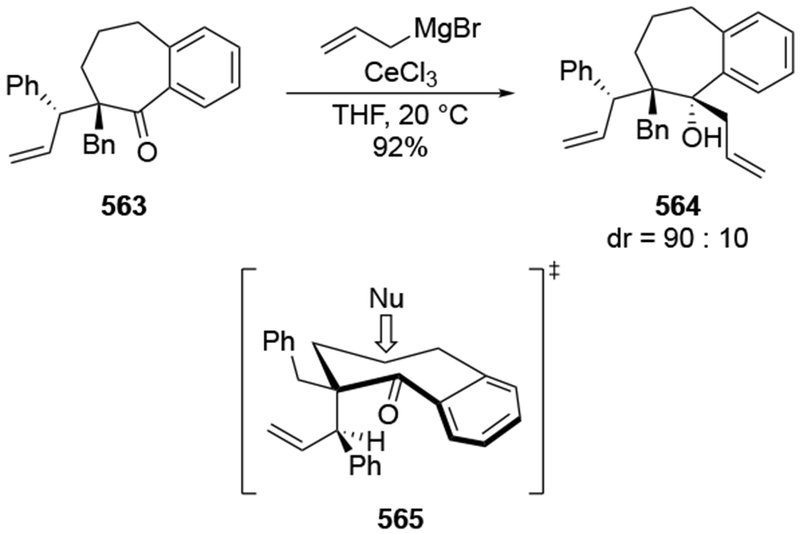

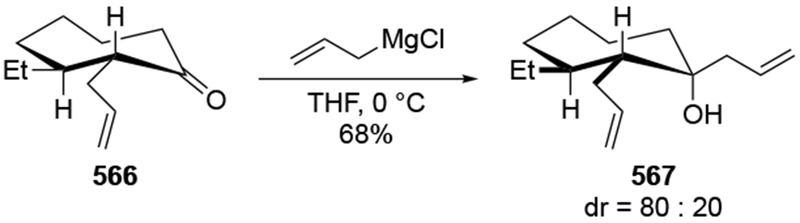

The contrasting reactivity of allylmagnesium reagents compared to other organomagnesium reagents is a general observation. Among several Grignard reagents examined for additions to ketone 69 and related substrates, allylmagnesium bromide was notable for its lack of chelation-controlled diastereoselectivity (Scheme 30).105

Scheme 30.

Even in conformationally controlled systems, these reactions are not generally stereoselective (Scheme 31).101 In this case, the low stereoselectivity was not a problem because the authors were interested in exploring the biological activity of different stereoisomers of the final product. That advantage does not apply to most situations, however.

Scheme 31.

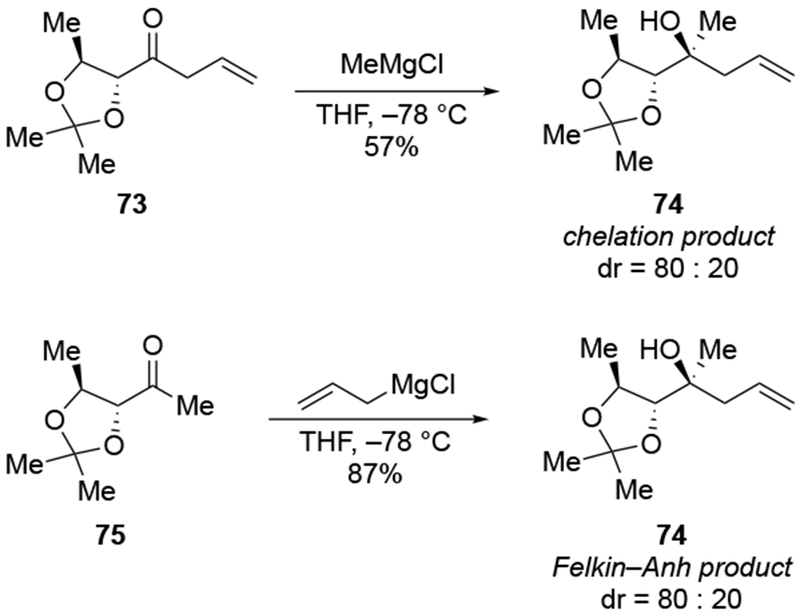

In some cases, addition of an allylmagnesium reagent occurred with the opposite stereoselectivity from what was expected (Scheme 32).106 Whereas addition of MeMgCl to the ketone 73 occurs with some selectivity for the product expected from chelation control, addition of allylmagnesium chloride to ketone 75 provided similar selectivity but for the opposite stereoisomer (i.e., the product of addition consistent with the Felkin–Anh model).

Scheme 32.

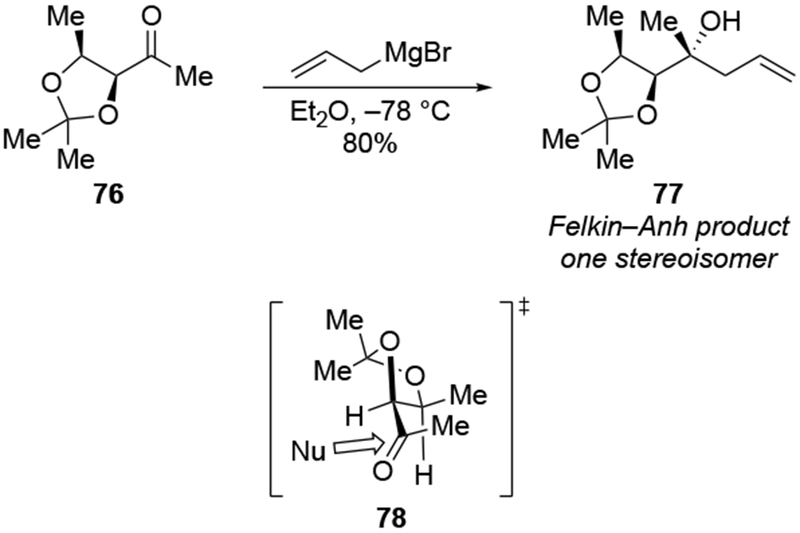

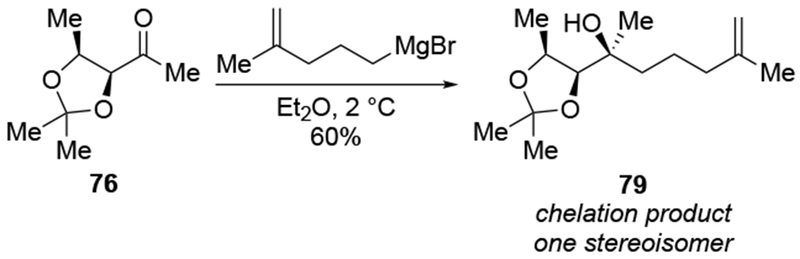

The importance of the overall structure of a compound and not just the potentially chelating α-stereocenter is illustrated by comparing the results shown in Scheme 32 to studies of a related ketone 76, Scheme 33 based upon the figure drawn in the paper and its conversion to a cyclic acetal).107 Addition to this ketone, the diastereomer of 75, gave much higher selectivity, but that reaction also did not form the chelation-control product: the transformation was highly Felkin–Anh selective. This reaction may be an example of a reaction selective for the Felkin–Anh product that does not proceed through a Felkin–Anh transition state, as discussed in Section 3. It is likely that the ketone exists predominantly in the conformation 78, which would minimize dipole interactions and avoid a potential syn-pentane-like interaction between the β-methyl group on the ring and the methyl group on the carbonyl carbon atom. Addition from the more accessible face would then give the observed product. This analysis also makes it easier to rationalize the fact that addition of a different organomagnesium reagent to ketone 76 occurred with the opposite sense of facial selectivity, giving the product expected from chelation control as a single stereoisomer (Scheme 34).108 The rate acceleration required of chelation control53,54 could be necessary for addition of an alkylmagnesium reagent to this hindered ketone. Addition of allylmagnesium halide would not need such rate acceleration for the reaction to proceed;22 addition could occur from the lowest-energy conformer.

Scheme 33.

Scheme 34.

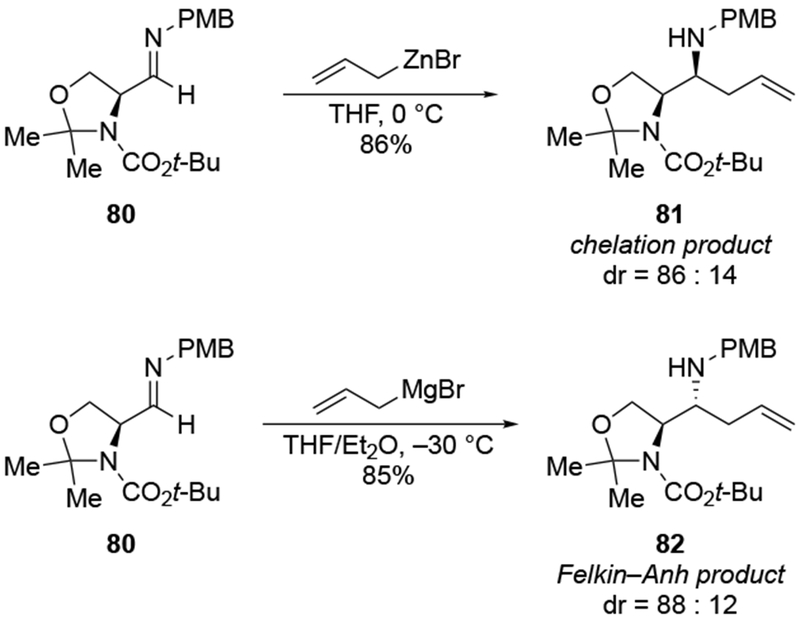

A similar comparison could be made with the addition to an imine, although these reactions will be discussed in more detail in a later section (Section 7). Addition of an allylzinc reagent to imine 80 gave the product expected from chelation control, whereas addition of the allylmagnesium reagent gave the Felkin–Anh product (Scheme 35).109

Scheme 35.

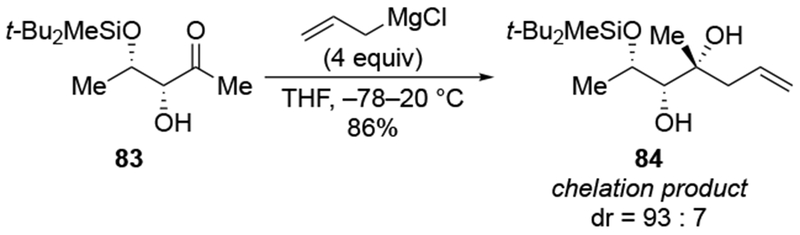

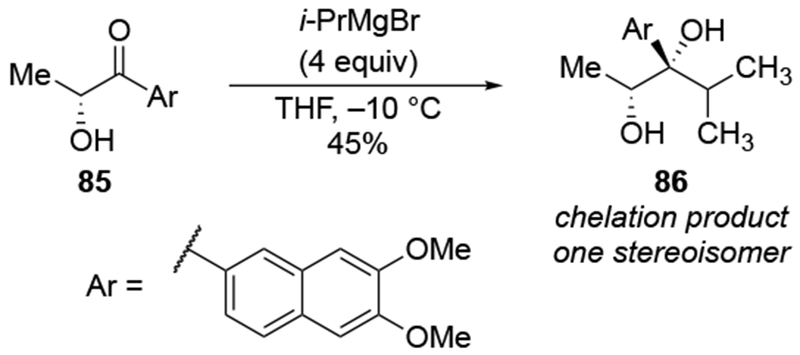

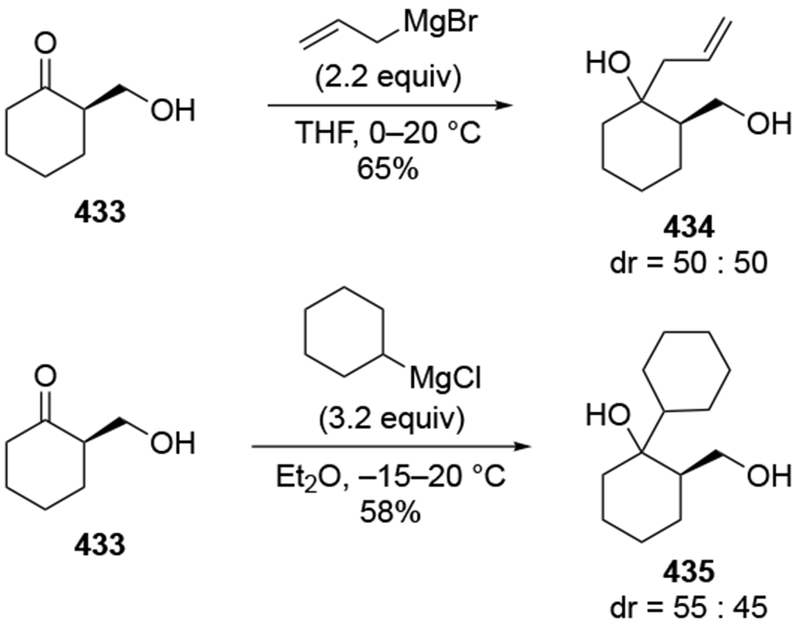

High selectivity for allylation can be observed in the case of α-hydroxy ketones, where the chelating group may be an OMgX group, not an OR group. The addition of an excess of allylmagnesium chloride to ketone 83 gave high selectivity for the product anticipated from chelation to the α-OMgCl group (Scheme 36).106 This type of addition has been seen previously (for example, with ketone 85, Scheme 37).110

Scheme 36.

Scheme 37.

Analyzing these selectivities by assuming that deprotonation of the hydroxyl group occurred first followed by chelation-controlled addition may or may not be logical. The rate of deprotonation of an alcohol by an alkylmagnesium reagent is much faster than addition, but for allylmagnesium reagents, the rate of addition to a carbonyl group is competitive with proton transfer from a relatively acidic OH group.111 Consequently, it cannot be assumed that the nearby OH group has been converted to OMgX prior to addition to the carbonyl group for every molecule of the reaction mixture.

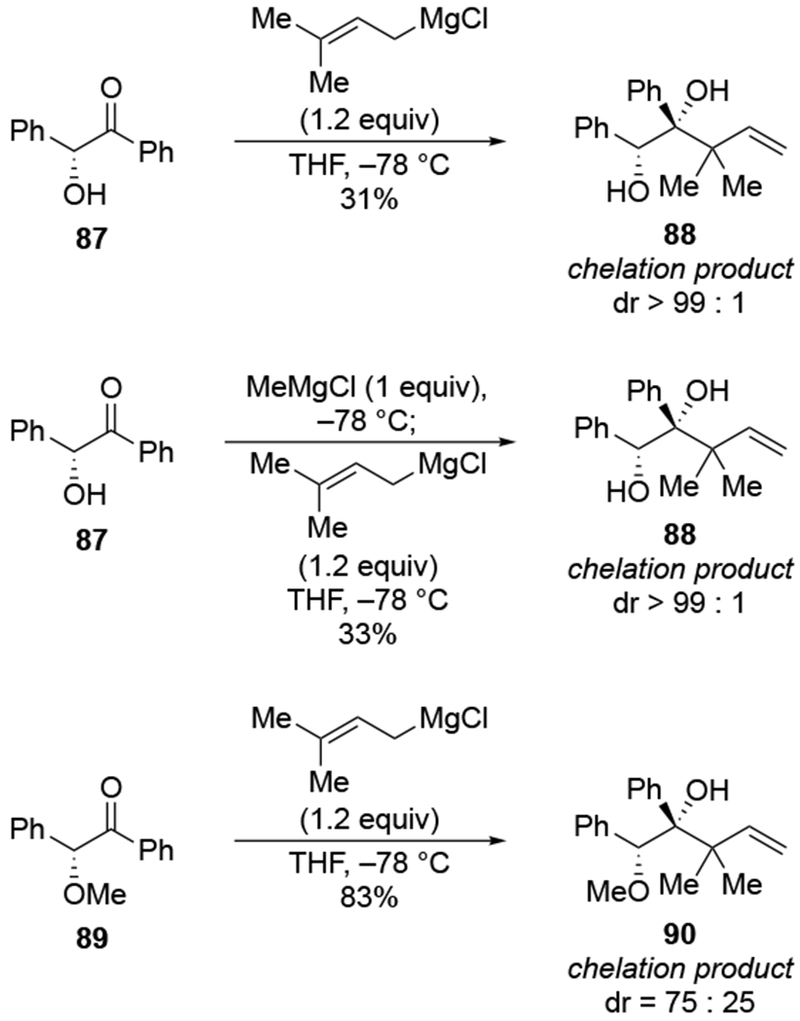

Evidence supporting the chelating ability of the OMgX group is illustrated by a comparison using prenylmagnesium chloride, a substituted allylmagnesium reagent (Scheme 38).23 Addition of one equivalent of prenylmagnesium chloride to the α-hydroxy ketone 87 gave high selectivity for the diol 88, which would be anticipated from chelation control (Scheme 38). The low yield of the product could result from competitive deprotonation of the hydroxyl group. A control experiment indicated that chelation to an OMgCI group is most likely responsible for selectivity. Initial deprotonation of the OH group was performed with MeMgCI. No addition of a methyl group occurred under these conditions, which is consistent with the fact that proton transfer should be much faster with an alkylmagnesium reagent.111 Subsequent addition of prenylmagnesium chloride to the resulting alkoxide gave the chelation-control product with similar selectivity and yield as in the original experiment. By comparison, prenylation of the corresponding α-methoxy ketone 89 occurred with low stereoselectivity.

Scheme 38.

These experiments also suggest a reason why additions to α-hydroxy ketones are more stereoselective than to α-alkoxy ketones. It is likely that with a negative charge present on the molecule, addition to the carbonyl group could be relatively slow (that is, with a rate constant that is slower than the rate of separation of the encounter complex, as discussed in Section 2.2). Additionally, with the magnesium atom now tightly bound to the α-oxygen atom, complexation of the carbonyl group to the metal atom becomes a unimolecular process, not a bimolecular one. That chelation should lead to faster addition54 to the magnesium alkoxide and therefore stereoselectivity. It is also worth noting that the general regioselectivity exhibited by prenylmagnesium reagents and the presence of this functional group in natural products make this reagent an attractive nucleophile for use in synthesis (for example, Scheme 39112). Oxidation of alcohol 92, followed by asymmetric reduction of the ketone provided the stereoisomer needed for the synthetic route.

Scheme 39.

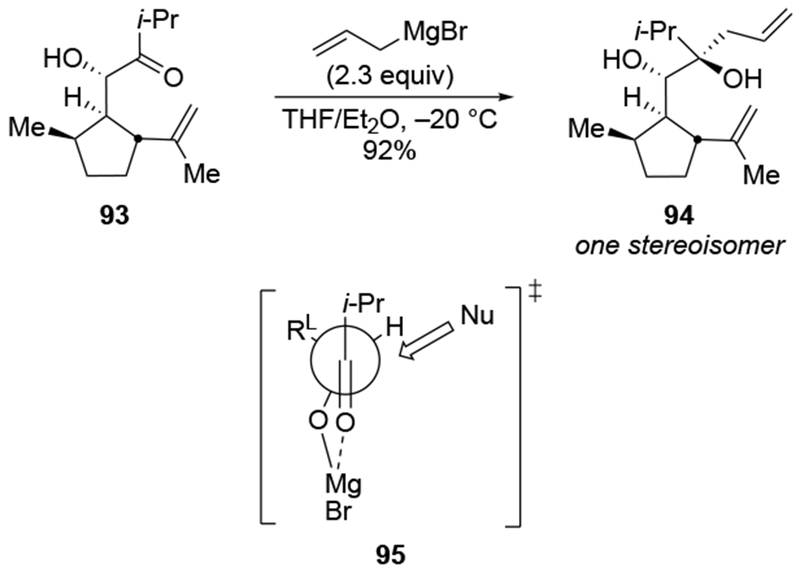

Addition of an allylmagnesium reagent to a more structurally complex α-hydroxy ketone also resulted in high stereoselectivity (Scheme 40).113 The stereoselectivity can again be rationalized by considering chelation to an α-OMgX group (as in 95).

Scheme 40.

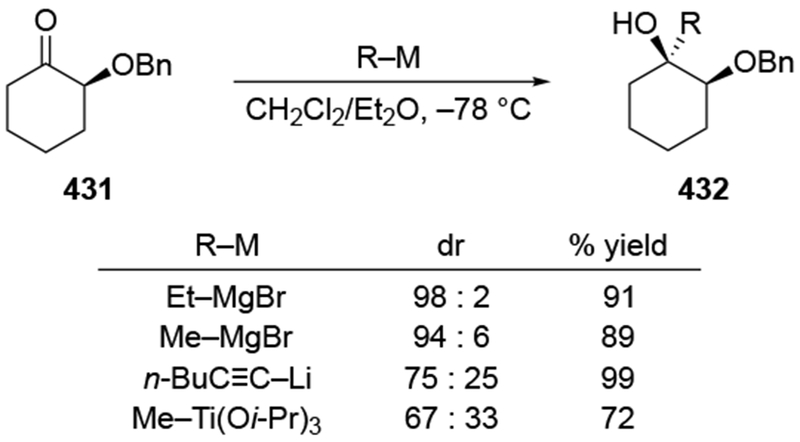

4.2.1.2. Use of Non-Coordinating Solvents to Improve Selectivities of Allylations of α-Alkoxy Ketones

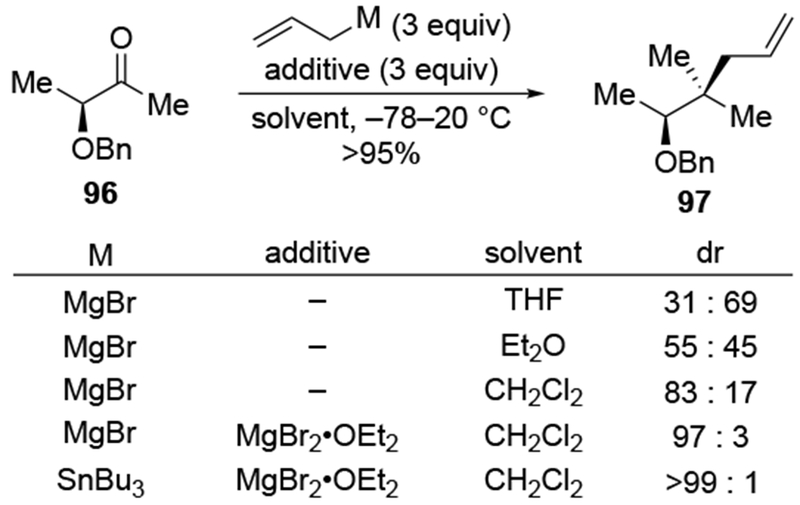

As noted above (Section 4.1), the use of non-ethereal solvents in reactions with allylmagnesium halides can give rise to more stereoselective reactions. Strictly speaking, however, these selectivities cannot be explained using the chelation-control model under Curtin-Hammett kinetics, as formulated by Eliel and Frye.53–55 Instead, stereoselectivity could arise because the major species in solution is the chelated intermediate.22 Allylations that are not selective in ethereal solvents show some improvement using halogenated solvents (Scheme 41).114 The selectivity for allylation of ketone 96 can be improved under carefully controlled conditions.22 The presence of additional magnesium salts under these conditions can improve the selectivity further, likely by increasing the proportion of a chelated species in solution compared to unchelated substrate. The selectivities under these conditions are comparable to those observed for the addition of allylstannanes with chelating Lewis acids.114 This combination of non-coordinating solvents and additional magnesium salts also can increase the stereoselectivity of additions of other organomagnesium reagents to α-alkoxy ketones.115

Scheme 41.

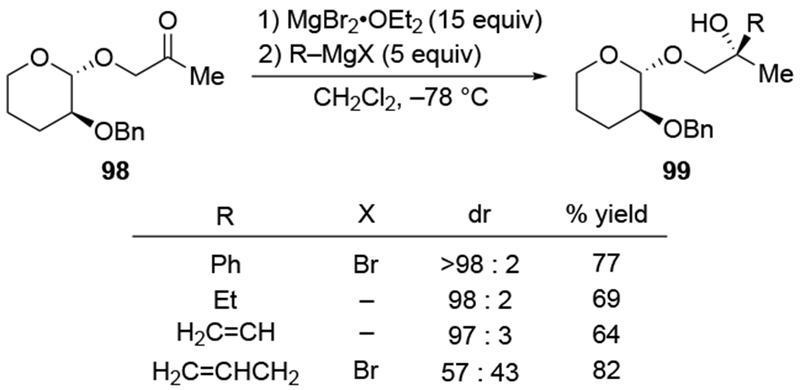

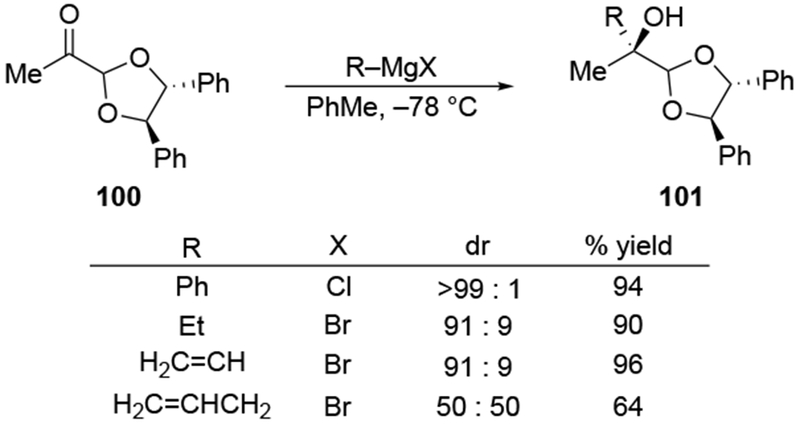

The use of halogenated solvents, although it should be considered as a possible solution, cannot solve all selectivity issues. For example, in a study using a chiral auxiliary to control selectivities for additions to a carbonyl group, additions of a number of organomagnesium reagents in CH2Cl2 with excess magnesium salts led to highly diastereoselective reactions (Scheme 42). Only in the case of allylmagnesium halides was this reaction unselective, even under these optimized conditions (the counterion was not specified in all cases).114 Another example of the failure of non-complexing solvents to solve the issues of low selectivity is illustrated for ketone 100, where allylmagnesium reagents once again reacted with uniquely low stereoselectivity (Scheme 43).116

Scheme 42.

Scheme 43.

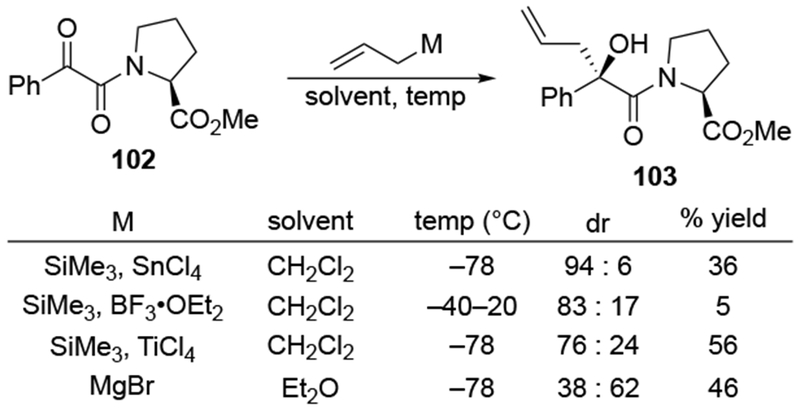

Related additions to an α-keto amide gave little diastereoselectivity for reactions of allylmagnesium halides (Scheme 44).117 Whereas selectivity could be achieved in some additions of allylmetal reagents in halogenated solvents, the addition of allylmagnesium bromide in Et2O was unselective (the other diastereomer was somewhat favored). Reactions of methylmagnesium and methyllithium reagents in Et2O with a similar substrate were similarly unselective, reacting with the same sense of selectivity as the allylmagnesium reagent (Scheme 45).118

Scheme 44.

Scheme 45.

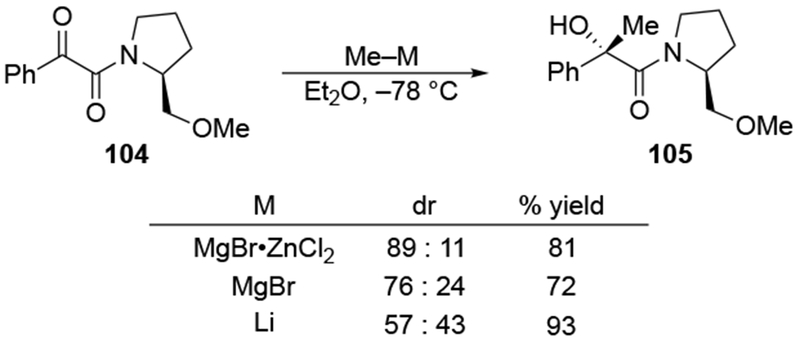

4.2.2. Additions to α-Alkoxy Acyl Silanes

Just as with additions to α-alkoxy ketones, additions of most organomagnesium halides to α-alkoxy acyl silanes can also be achieved with chelation control (Scheme 46).119 The additions of allylmagnesium reagents, however, proceeded with little stereoselectivity. In this case, use of a different allylmetal reagent formed product 107 selectively. These results demonstrate that although acyl silanes are more electrophilic than the corresponding ketones,120 they appear to follow similar trends of diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 46.

4.2.3. Additions to β-Alkoxy Carbonyl Compounds

4.2.3.1. Additions to β-Alkoxy Ketones

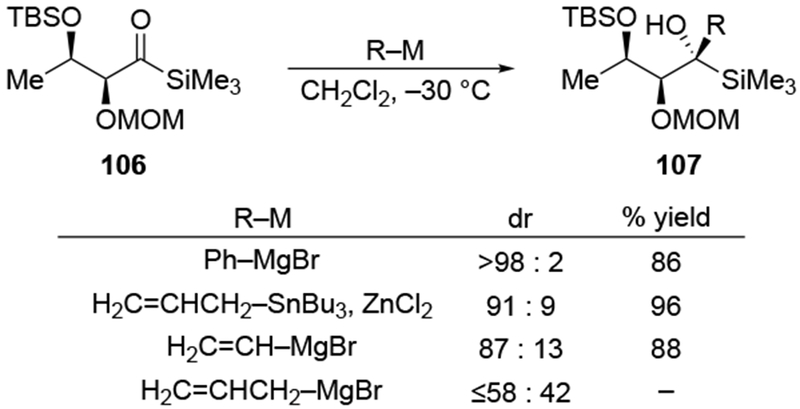

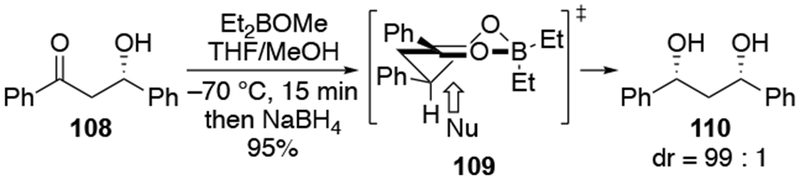

Additions of nucleophiles to β-alkoxy ketones using chelation control can be stereoselective. A particularly useful example is the stereoselective reductions of β-hydroxy ketones (Scheme 47).121 This reaction involves chelation of a boron reagent to the β-hydroxyl and carbonyl groups followed by reduction of the chelate 109 from the stereoelectronically favored face.122,123 Methods for performing chelation-controlled reductions of β-alkoxy ketones have also been reported.124

Scheme 47.

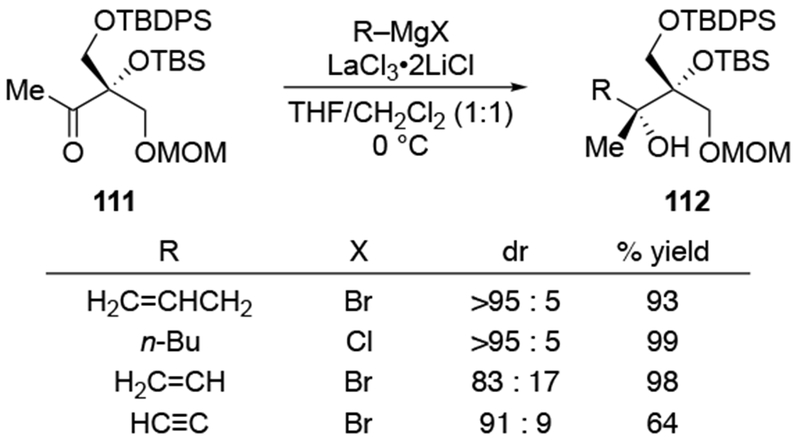

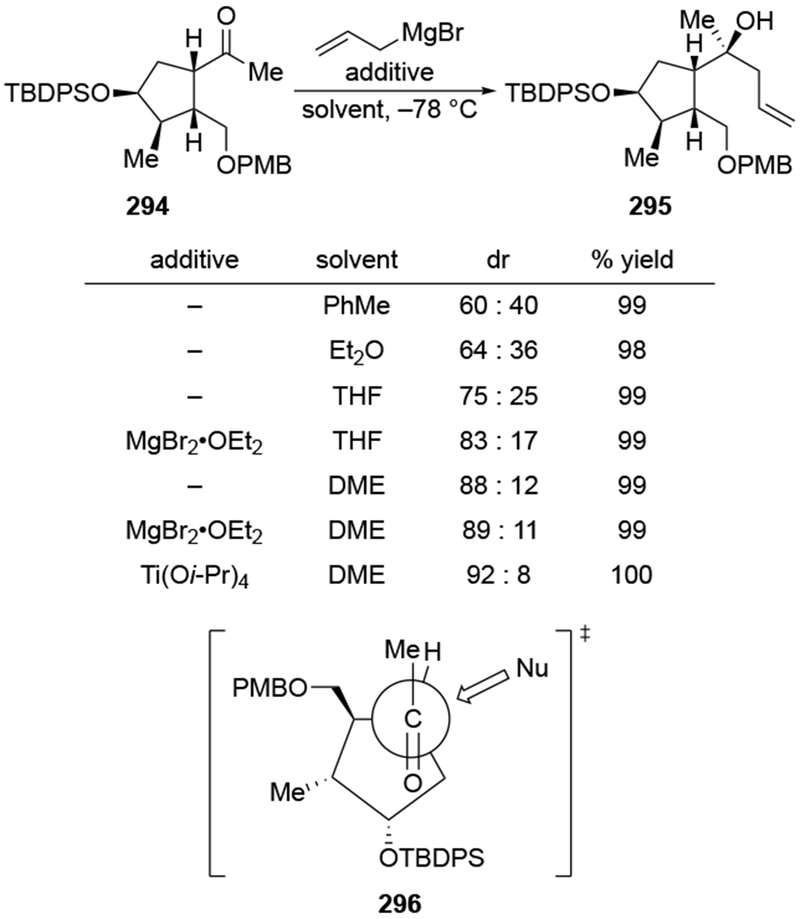

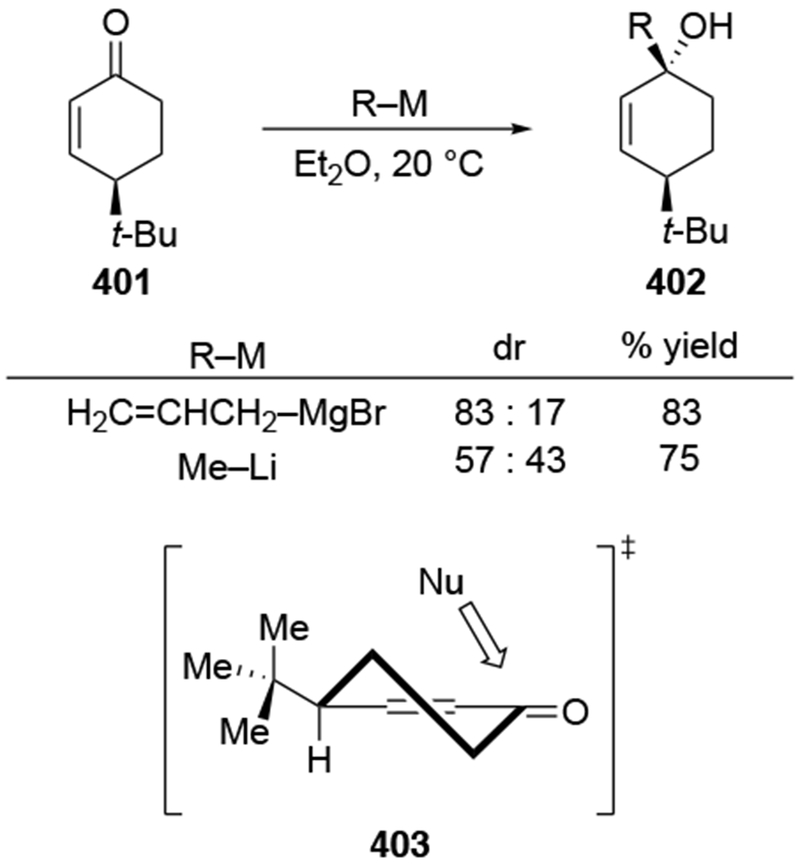

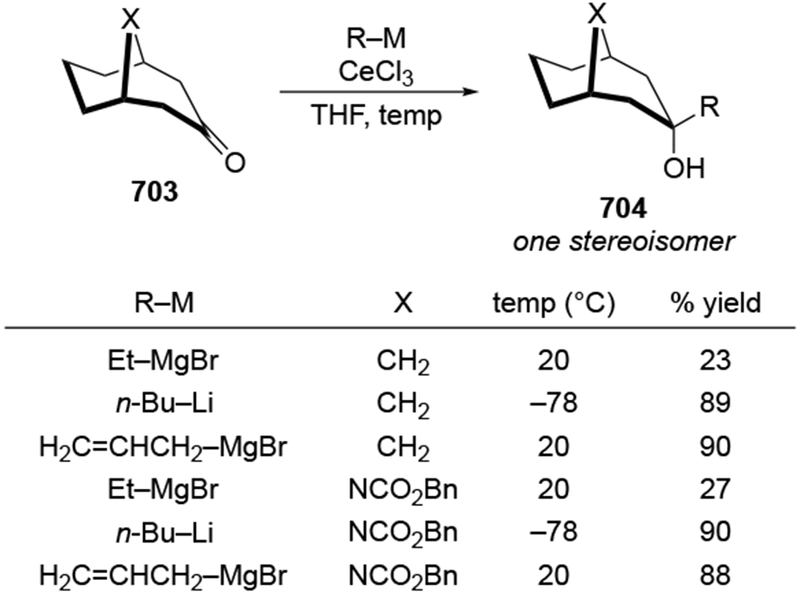

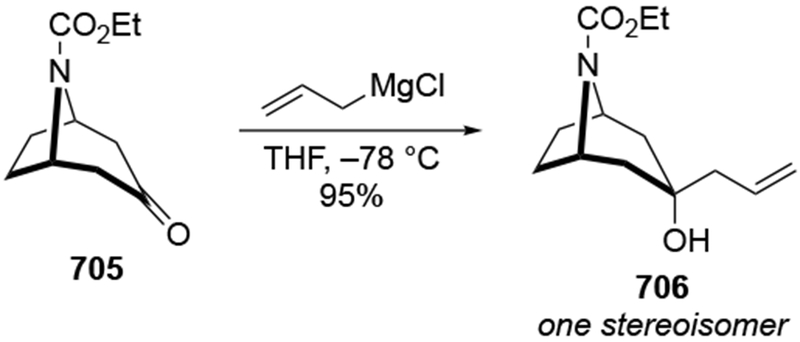

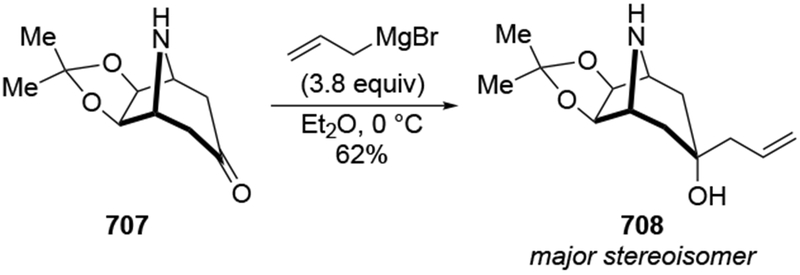

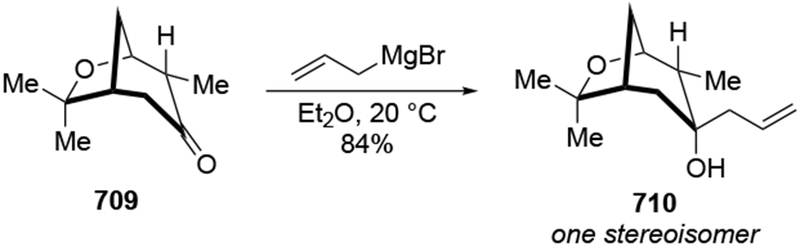

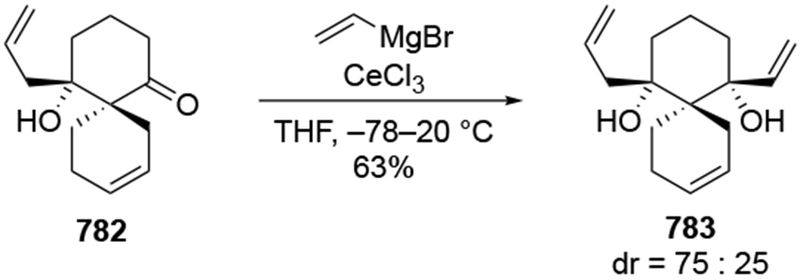

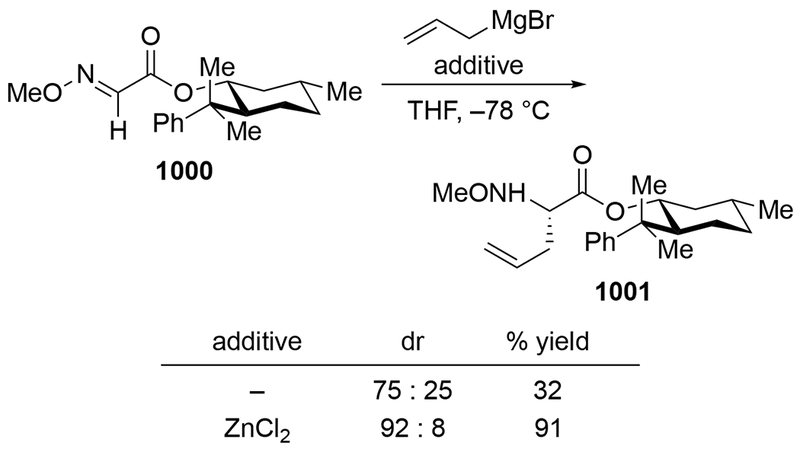

As a general rule, additions of Grignard reagents to β-alkoxy ketones are much less selective than the corresponding reactions of α-alkoxy ketones.100 Nevertheless, attempts to obtain the β-chelation product have been successful in some cases.125 In the presence of lanthanum salts, additions of organomagnesium reagents can be stereoselective in some cases (Scheme 48). Selectivity was also higher in mixtures of THF and CH2Cl2 instead of THF alone. No information was provided regarding the selectivities without the use of the metal salt and whether these conditions resulted in transmetallation to form an organolanthanum intermediate. The higher selectivity of the allylation reaction in this case may also reflect the fact that this ketone is highly hindered, so it should undergo additions more slowly, possibly below the diffusion rate limit.

Scheme 48.

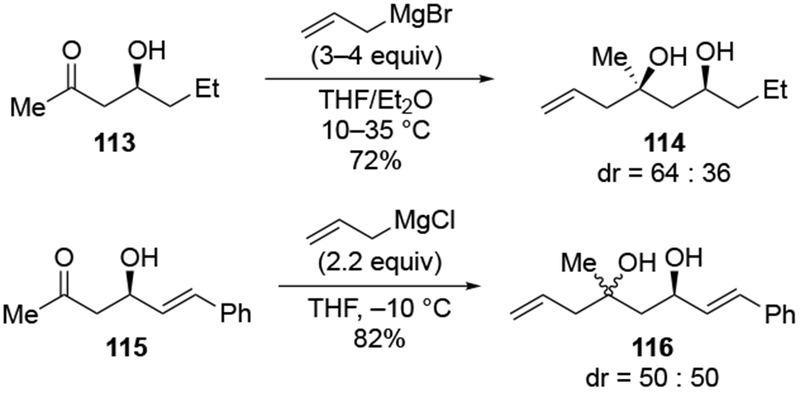

Attempts to achieve chelation-controlled addition using an OMgX group at the β-position were not selective (Scheme 49).126,127 Additions of allylmagnesium halides to β-hydroxy ketones 113 and 115 resulted in low selectivity. This lack of selectivity appears to be general.128

Scheme 49.

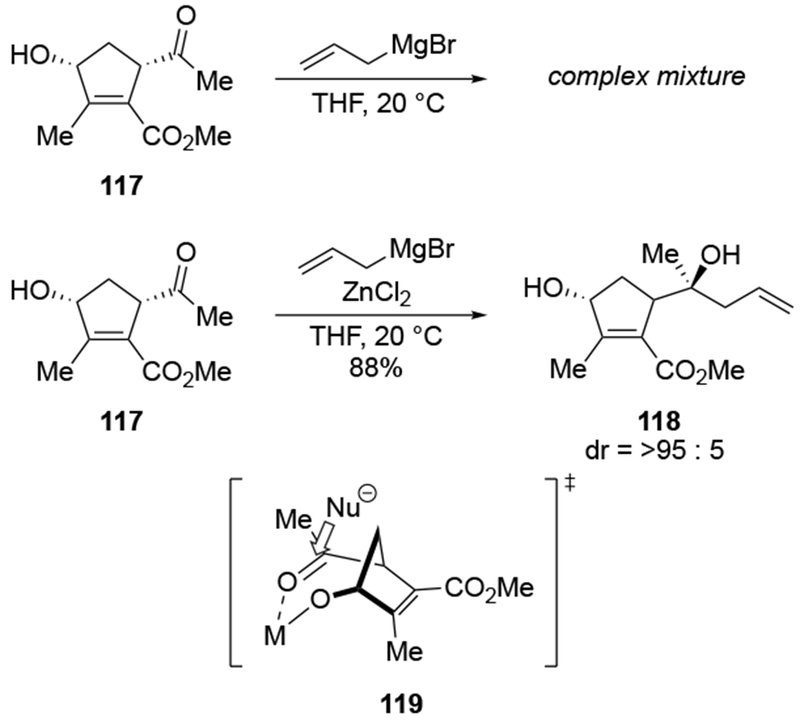

In more complex settings, however, there have been examples of remote complexation of an alkoxide anion (Scheme 50).129 In the case of hindered ketone 117, treatment with allylmagnesium bromide gave a complicated mixture of products, likely because the carbonyl and carboxyl groups reacted with allylmagnesium reagents at competitive rates.17 Deprotonation of the hydroxyl group also likely occurred at a similar rate.111 Transmetallation to zinc did allow for a stereoselective addition reaction, which the authors attributed to chelation of the remote alkoxy group of compound 117.129 It is also likely that the ketone adopts a conformation resembling 119 to minimize destabilizing steric interactions (i.e., allylic strain130) between the two carbonyl groups.

Scheme 50.

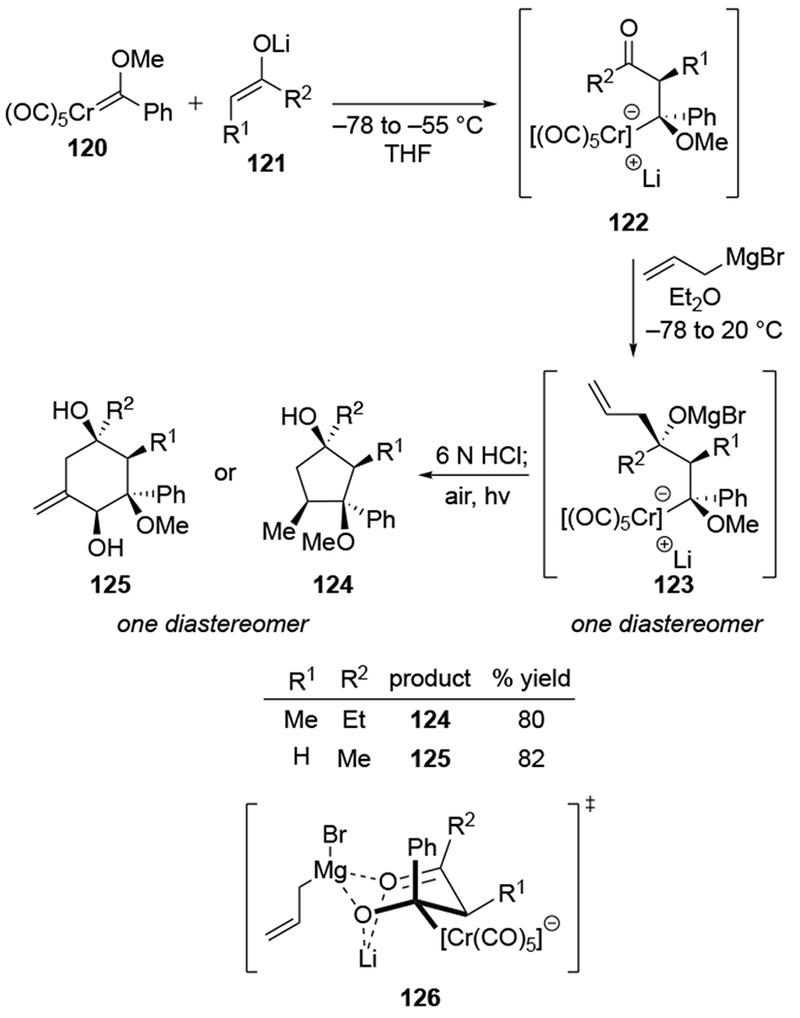

A case of β-chelation controlled addition was reported in the context of a chromium-mediated transformation (Scheme 51).131 This reaction incorporates the allyl fragment into the ring by an addition reaction onto β-alkoxy-substituted ketone 122. The product of that step, alkoxide 123, was attributed by the authors to be formed through the chelated transition state 126, where the nucleophile was delivered to the external face of carbonyl group, which faces away from the ring. Further transformations that close the ring to the five- and six-membered rings involve reactions of chromium carbenes.

Scheme 51.

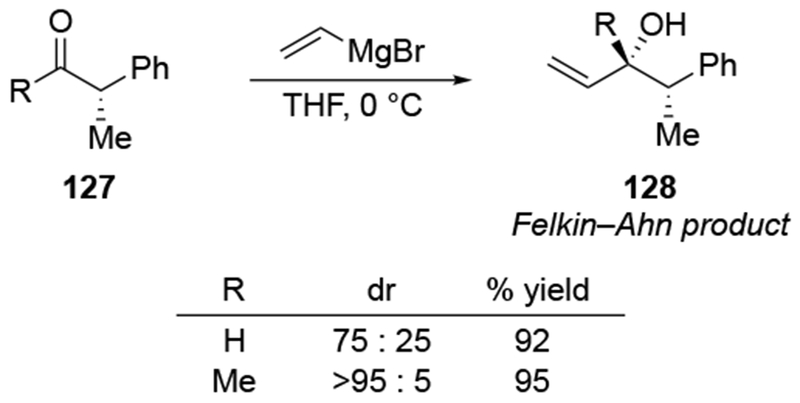

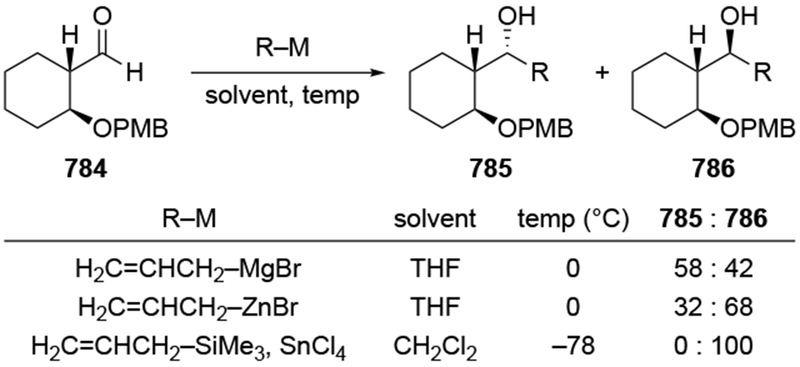

4.2.4. Additions to α-Substituted Aldehydes

Generally, additions to chiral aldehydes are much less stereoselective than the corresponding additions to ketones, even for non-allylic Grignard reagents 22,132–134.This difference in selectivity likely relates to the significantly higher electrophilicity of aldehydes compared to ketones.17,135 The difference in selectivity can be illustrated by several examples using Grignard reagents. For example, Felkin–Anh selective additions to aldehydes are generally poorly selective, but additions to the corresponding ketones can be highly stereoselective (Scheme 52).136

Scheme 52.

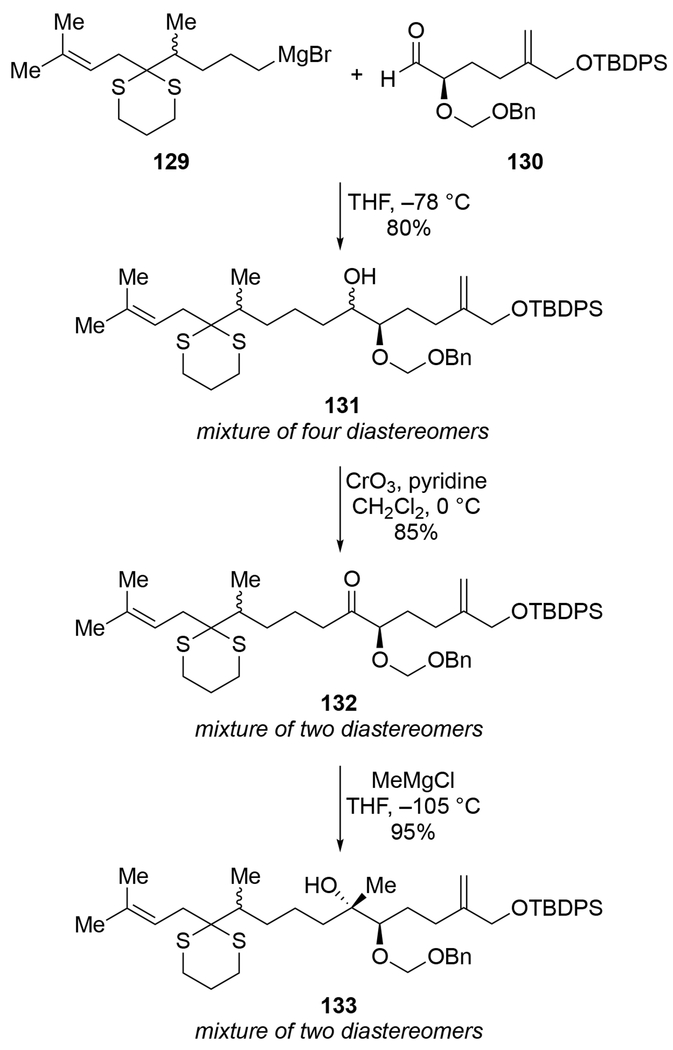

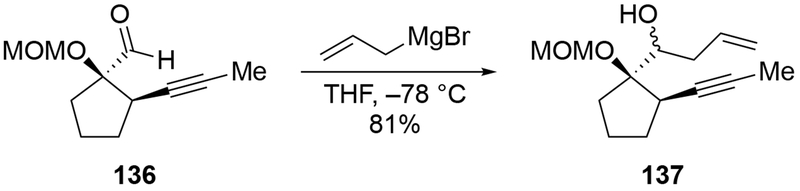

A more complicated example is illustrated in Scheme 53.137 Addition of racemic alkyl Grignard reagent 129 to racemic aldehyde 130 (shown as only one enantiomer to simplify the discussion) gave a mixture of four diastereomeric products (each as its racemate). This lack of selectivity shows that the BnOCH2– protecting group, though capable of chelation, could not control the stereoselectivity of addition to the aldehyde. Upon oxidation to ketone 132, one of the stereocenters was removed, leaving only two diastereomers detectable by NMR spectroscopy. Addition of MeMgCl to ketone 132 formed only two detectable stereoisomers, which indicates that the new stereocenter was formed with high stereoselectively. The relative configuration of this product, which is consistent with chelation-controlled addition to the ketone directed by the α-BnOCH2O group, was established upon conversion of tertiary alcohol 133 into the natural product zoapatanol. The stereoselectivity of the third step (132 → 133) was not an artifact of the order of addition: reversing the order of the synthetic steps in which the Grignard reagents were added gave the tertiary alcohol 133 with the opposite configuration at the newly formed stereogenic center. That result arose from chelation-controlled alkylation of a methyl ketone intermediate (not shown). These results demonstrate that, even for alkylmagnesium reagents, chelation-controlled additions to ketones can be stereoselective while additions to aldehydes are not.

Scheme 53.

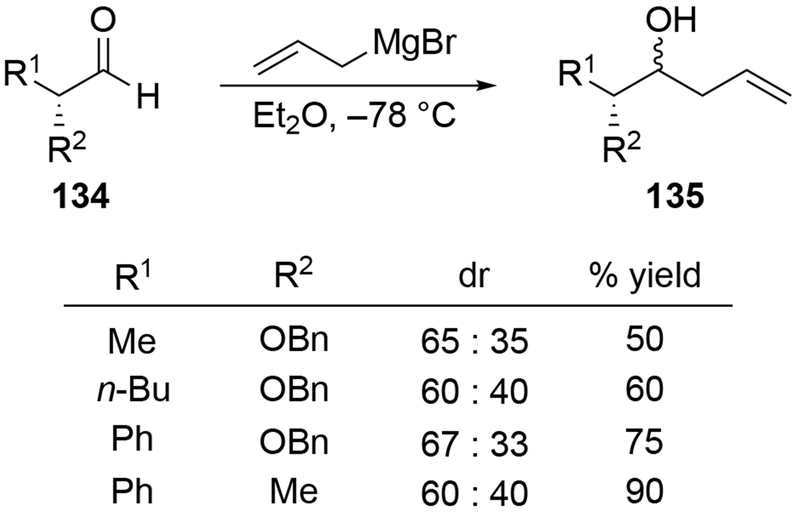

The above results reinforce observations involving allylmagnesium reagents (Scheme 54).138 Regardless of the substitution pattern on the aldehyde, stereoselectivity of addition to the α-alkoxy aldehyde was poor. The diastereoselectivity was comparable to that of a simple ketone that did not contain a chelating group (R1 = Ph, R2 = Me). Other examples confirm that additions of allylmagnesium reagents to α-alkoxy aldehydes proceed with low stereoselectivity (Scheme 55).139

Scheme 54.

Scheme 55.

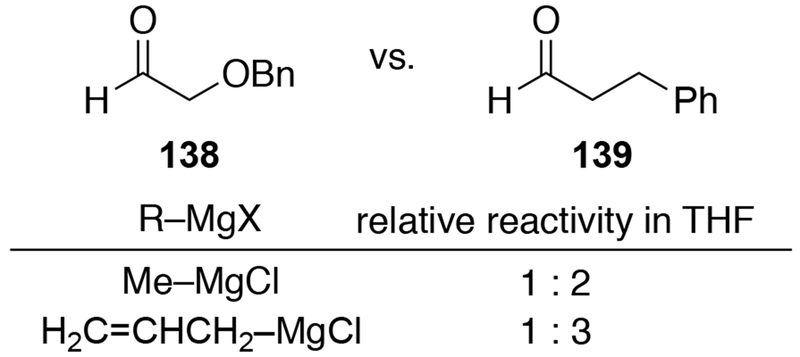

Recent experiments suggest a possible explanation for why α-alkoxy aldehydes are not generally able to undergo chelation control with any Grignard reagent. Competition experiments using THF as solvent revealed that no rate acceleration occurred for additions to an aldehyde capable of forming a chelated intermediate (138) versus an aldehyde that cannot (139) for either allyl- or methylmagnesium chloride (Scheme 56). As discussed in Section 4.1, the rate acceleration observed for additions to β-alkoxy ketones was essential for diastereoselectivity because these systems operate under Curtin–Hammett control, where the majority of the product is formed through the lower-energy, chelated transition state. If rate acceleration were not present, the chelated transition state would no longer be favored, so addition could occur to any of the many forms of the aldehyde in solution (i.e., not complexed to RMgX (58), complexed to RMgX but not chelated (59), and chelated to RMgX (60), as illustrated in Scheme 24), resulting in low stereoselectivity.22 It is possible that, because reactions of allylmagnesium halides with α-alkoxy ketones are not chelation-controlled due to the high rate constants associated with addition reactions, reactions involving all organomagnesium halides with α-alkoxy aldehydes are generally not amenable to chelation control due to the higher reactivity of aldehydes compared to ketones.17,88

Scheme 56.

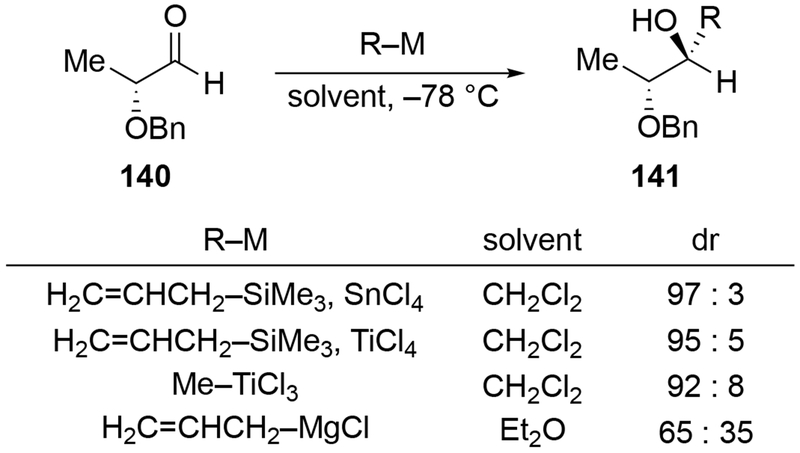

4.2.4.1. Use of Other Metals to Increase Selectivity of Allylation

A commonly used strategy to solve the problem of low stereoselectivity for allylation of aldehydes using allylmagnesium halides is to use other allylmetal reagents. Considering that this topic was reviewed in considerable detail,1,20 only some foundational studies will be described here. The high diastereoselectivity that can sometimes be obtained in reactions of α-alkoxy aldehydes with a number of different allylmetal reagents is illustrated in Scheme 57.97,138,140,141 Transmetallation can be effective for providing products with high chelation-controlled diastereoselectivity, and the use of allylsilanes or allylstannanes in the presence of Lewis acids provides another alternative. This solution can be general (Scheme 58).142 The preference for the Felkin–Anh product in the case of the allylboron nucleophile (pin = OCMe2CMe2O) reflects the fact that the boron atom cannot accommodate the extra coordination required for observing chelation-controlled addition.

Scheme 57.

Scheme 58.

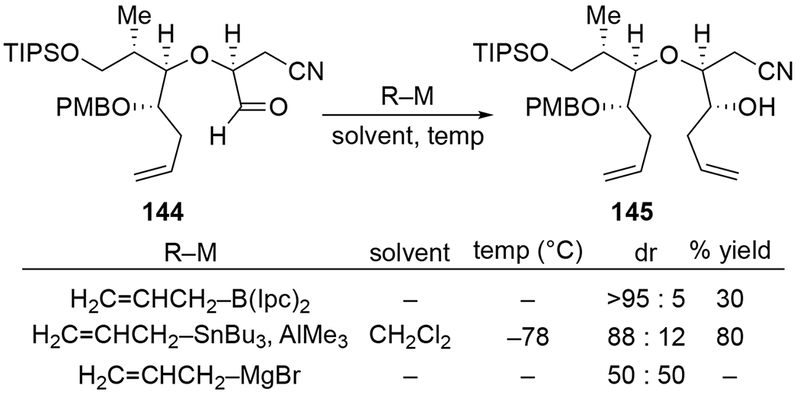

Related studies show that the use of other allylmetal reagents can be effective to control the diastereoselectivity of additions to α-alkoxy aldehydes (Scheme 59).143 Allylmagnesium bromide added to aldehyde 144, but the product was formed with little stereoselectivity (reaction conditions were not provided). Attempts at allylation using allyltrimethylsilane gave no reaction, but addition of allyltributylstannane with AlMe3 as a Lewis acid gave good diastereoselectivity. A common method to performing stereoselective allylations involves using a chiral boron reagent,144 but in this case that reagent did not add efficiently.

Scheme 59.

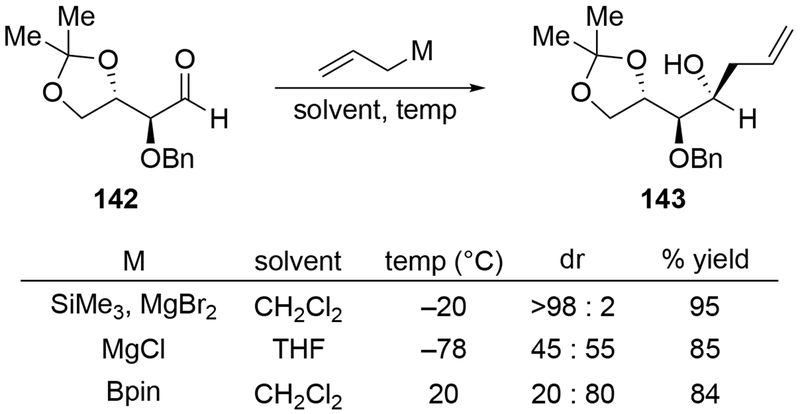

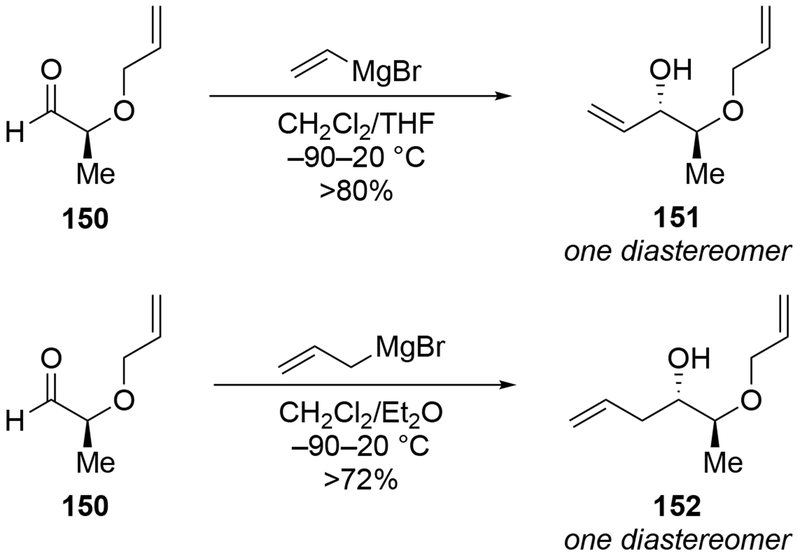

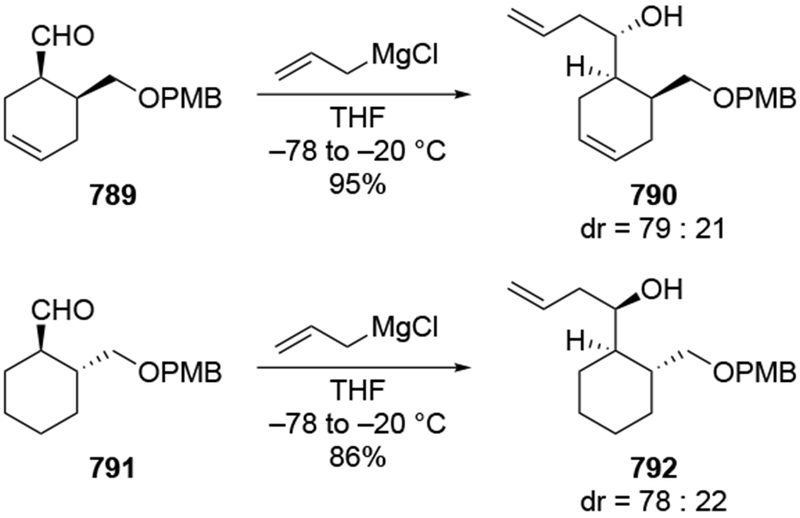

4.2.4.2. Use of Non-Coordinating Solvents and Salts to Improve Selectivities of Allylation

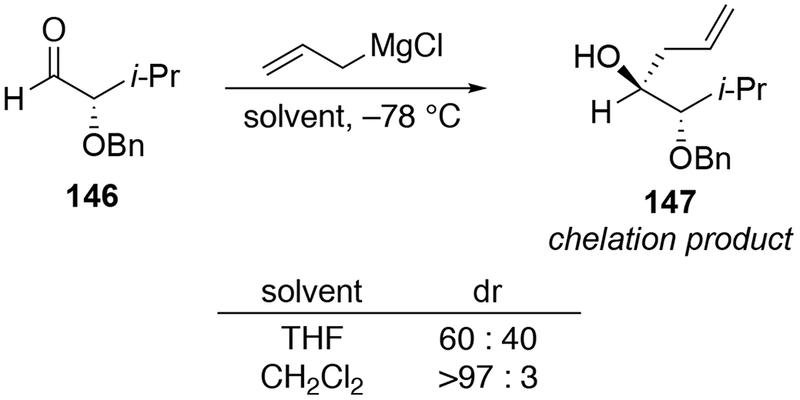

As with ketones, non-coordinating solvents such as CH2Cl2 can be used to obtain the chelation-controlled product in the absence of chelation-induced rate acceleration (Scheme 60).22 Addition of a suspension of allylmagnesium bromide in CH2Cl2 to aldehyde 146 was able to form alcohol 147, the product expected by chelation control, as a single diastereomer. By comparison, the addition in THF gave a mixture of diastereomers. As with α-alkoxy ketones, however, this protocol is not always successful (Scheme 61).145

Scheme 60.

Scheme 61.

Other examples of highly selective additions to α-alkoxy aldehydes using CH2Cl2 as the solvent have been reported. For both additions of vinyl- and allylmagnesium bromide to aldehyde 151, chelation-control products were formed stereoselectively (Scheme 62).146 Changing the protecting group on the hydroxyl group of 150 to a non-coordinating silyl ether led to high diastereoselectivity favoring the product with the opposite configuration (Scheme 121, Section 5.3).

Scheme 62.

Scheme 121.

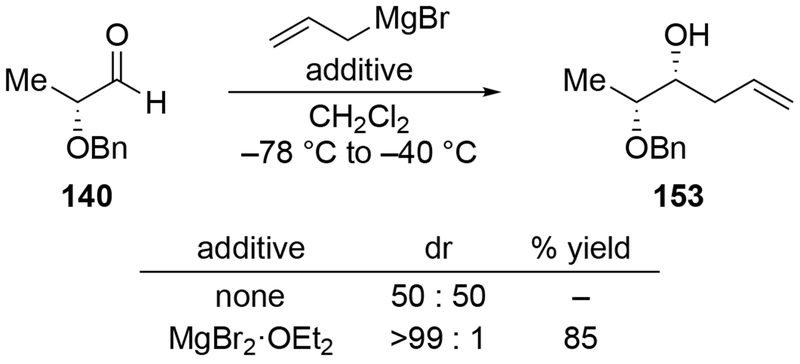

As with ketones, when an α-alkoxy aldehyde is already in a noncoordinating solvent, the addition of metal salts can increase the diastereoselectivity of reactions with allylmagnesium halides.147 Whereas addition to 140 gave low selectivity without additives, the authors report high selectivity in the presence of a magnesium salt (Scheme 63).114,147 It should be noted that for the more hindered aldehyde 146 with an α-benzyloxy group (Scheme 60), the addition of magnesium salts were not necessary to observe high selectivity, but the use of CH2Cl2 as solvent was.

Scheme 63.

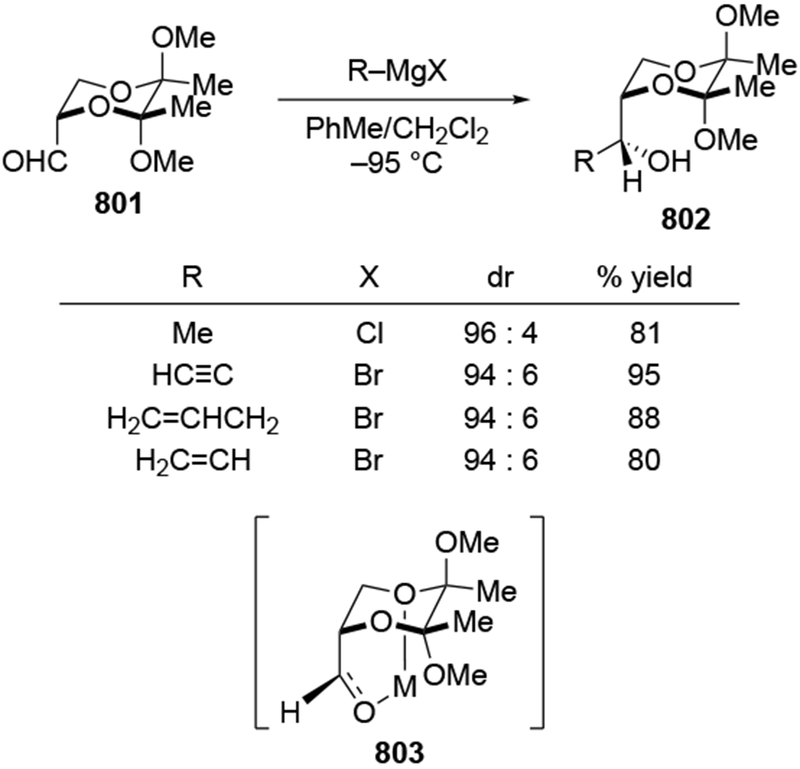

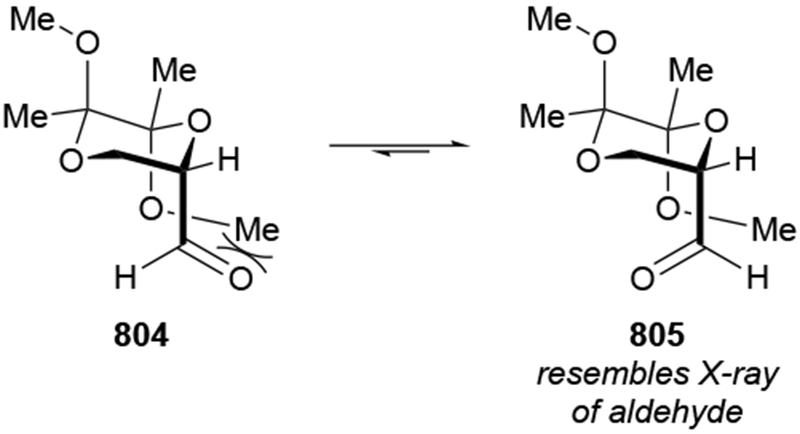

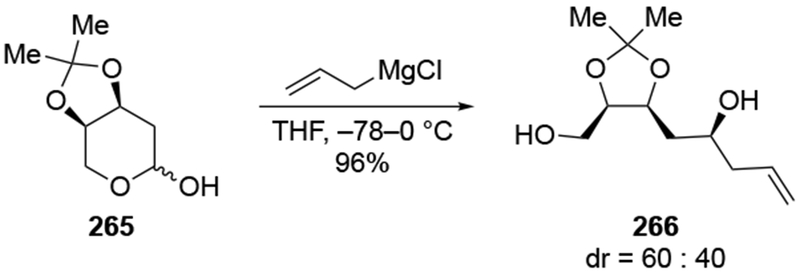

4.2.4.3. Allylations of α-Alkoxy Aldehydes

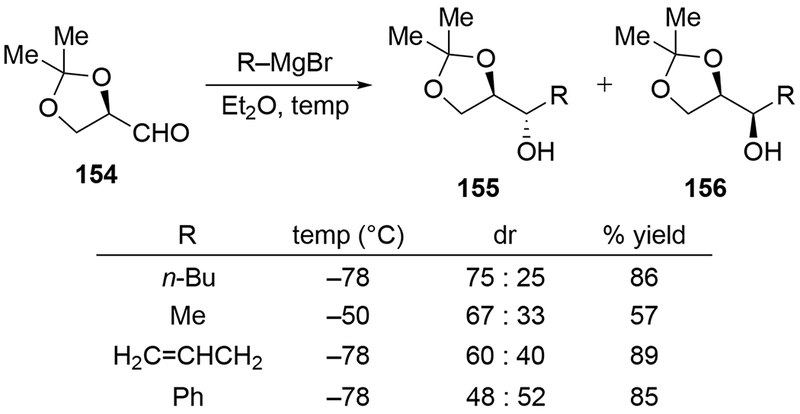

A common example of a substrate that is reluctant to undergo chelation-controlled, stereoselective additions by Grignard reagents is protected glyceraldehyde acetonide (154). Although a useful protecting group for 1,2- and 1,3-diols, the acetonide is not generally optimal for obtaining chelation-controlled addition products from α-alkoxy aldehydes (Scheme 64).99,148 Addition of a variety of Grignard reagents, including allylmagnesium bromide, to aldehyde 154 proceeded with low diastereoselectivity. This lack of selectivity was attributed to the presence of the second oxygen atom at the β-position, which could chelate through a six-membered ring transition state. As a result, better selectivities are usually observed with different protection schemes, particularly with a benzyl group at the α-oxygen atom.149,150 Additions to a more elaborated version of this aldehyde (157) were also unselective (Scheme 65).151

Scheme 64.

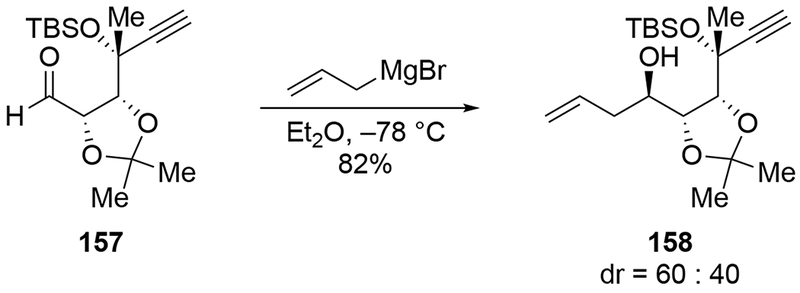

Scheme 65.

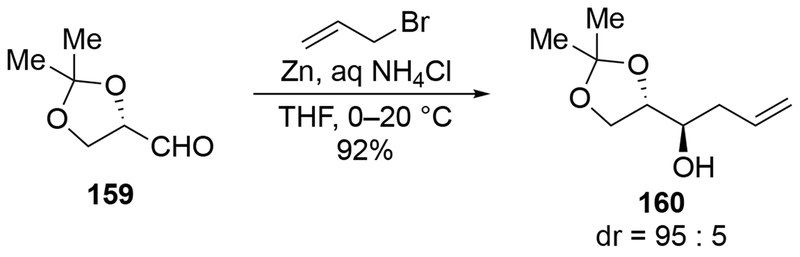

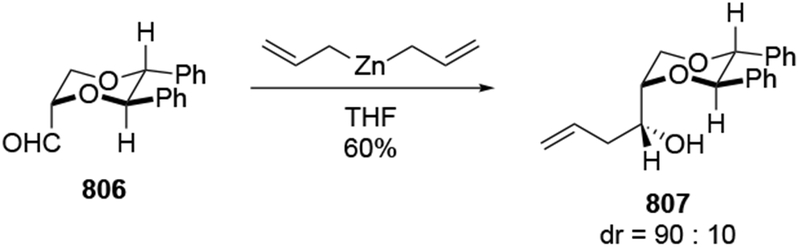

It is possible to observe highly stereoselective reactions of glyceraldehyde acetonide (159). Whereas no selectivity was observed above with allylmagnesium bromide (Scheme 64),148 additions of an allylzinc reagent to aldehyde 159 proceeded with high diastereoselectivity, favoring the product expected had Felkin–Anh control operated (Scheme 66).152

Scheme 66.

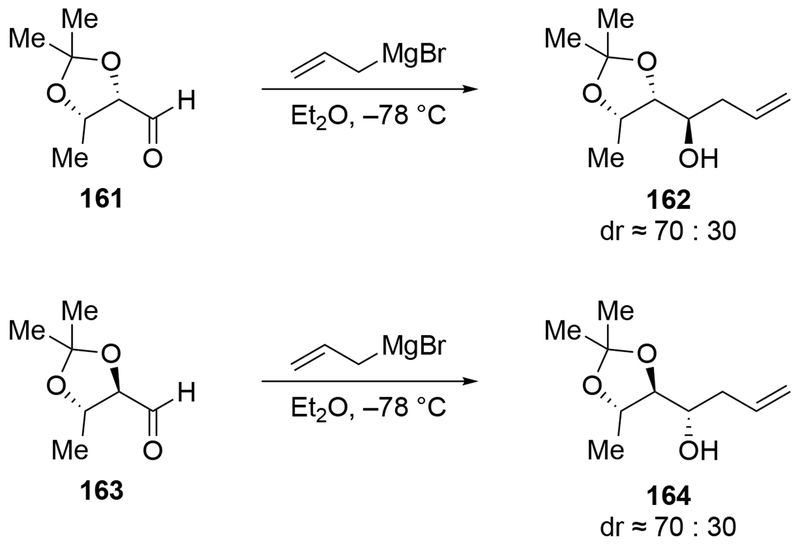

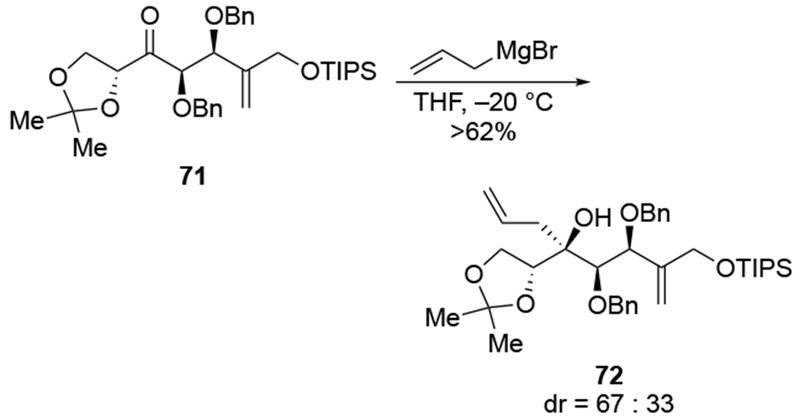

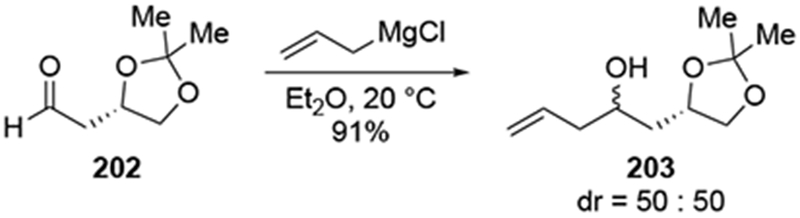

Generally, however, allylmagnesium reagents add to acetonide derivatives with low diastereoselectivity (Scheme 67).107 Regardless of the relative stereochemistry of the starting material, additions are unselective.

Scheme 67.

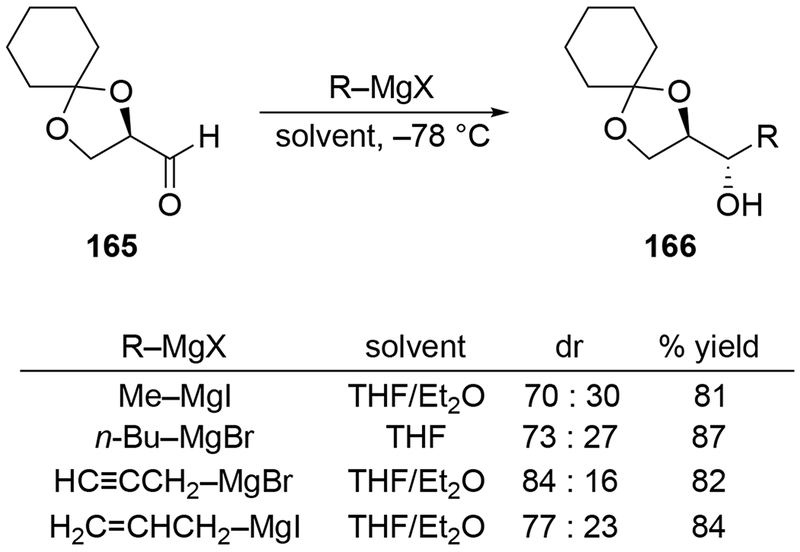

With other types of ketal-protected α,β-dihydroxy aldehydes, stereoselectivities were also low (Scheme 68).153. Despite this low stereoselectivity, the allylation reaction of aldehyde 165 has been used in natural product synthesis after separation of the desired stereoisomer from the undesired one.154,155

Scheme 68.

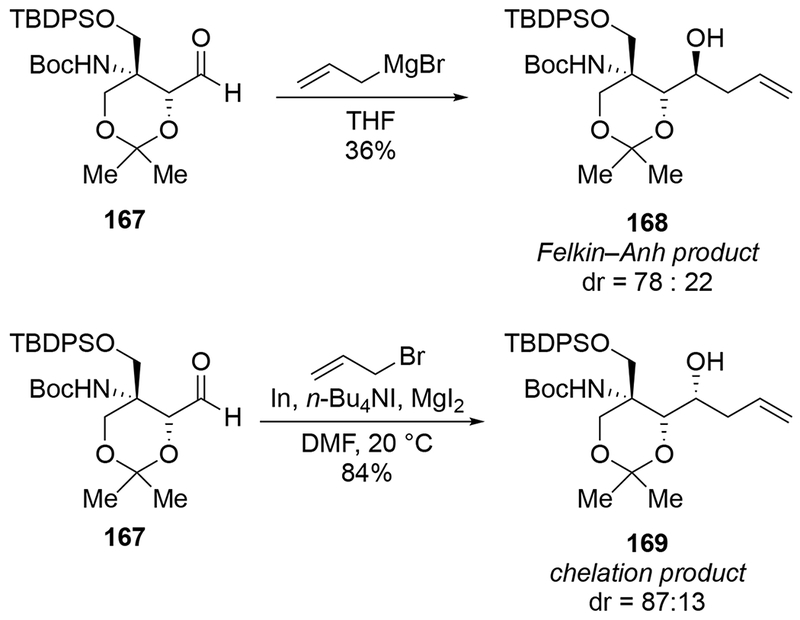

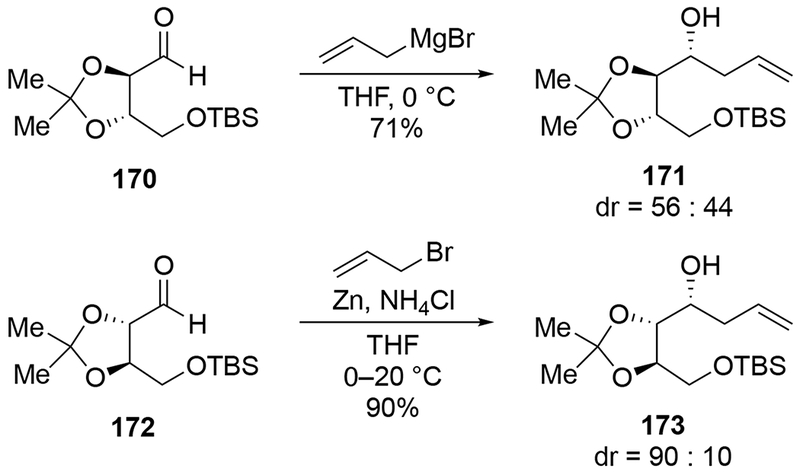

In some cases with potentially chelating alkoxy groups, allylation gave unexpected products (Scheme 69).156 Instead of forming the product expected from chelation control, addition to 167 resulted in low stereoselectivity in favor of the Felkin–Anh product. As noted earlier (Section 3), the formation of the Felkin–Anh product need not be the result of a Felkin–Anh transition state; other transition states could be responsible for formation of this product. Ultimately, achieving the desired stereochemical outcome required using organoindium reagents, which are generally useful for achieving chelation-controlled additions.157 A similar observation was made with aldehyde 170, which underwent allylation with allylmagnesium bromide unselectively (Scheme 70).158 The opposite diastereomer was obtained using an organozinc reagent.

Scheme 69.

Scheme 70.

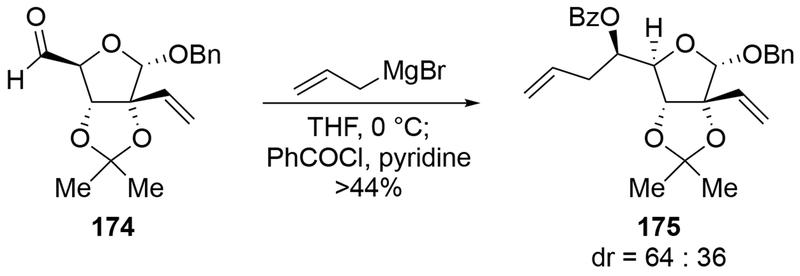

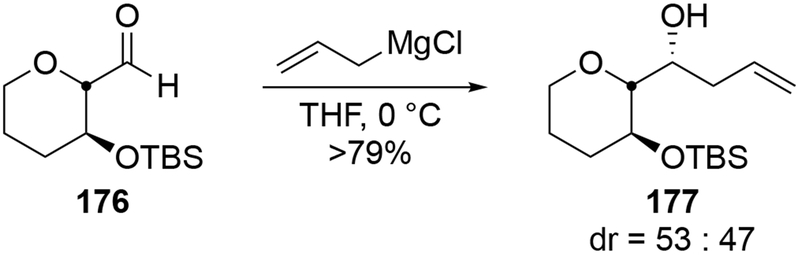

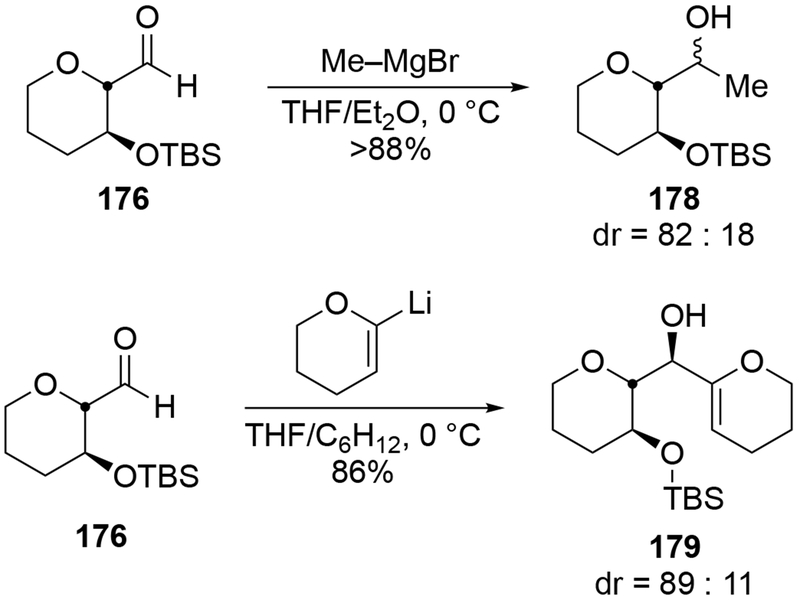

Other cyclic ethers bearing formyl groups also reacted unselectively. Additions to furanose-derived aldehyde 174 gave an inseparable mixture of diastereomers, which were carried on in a subsequent ring-closing metathesis reaction to prepare nucleoside analogues (Scheme 71).159 This type of furan generally gives low stereoselectivity for additions of nucleophiles.160,161 Low selectivity was also observed in the pyran series (Scheme 72).162 The pyran-substituted aldehyde 176 can react diastereoselectively: addition of methylmagnesium bromide was moderately diastereoselective (the stereochemistry of the major product was not assigned),163 and addition of an alkenyllithium reagent was highly stereoselective (Scheme 73).164

Scheme 71.

Scheme 72.

Scheme 73.

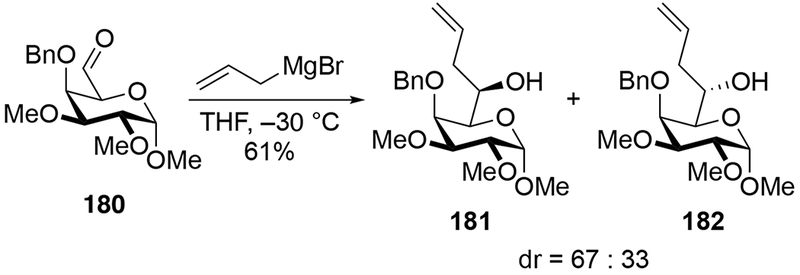

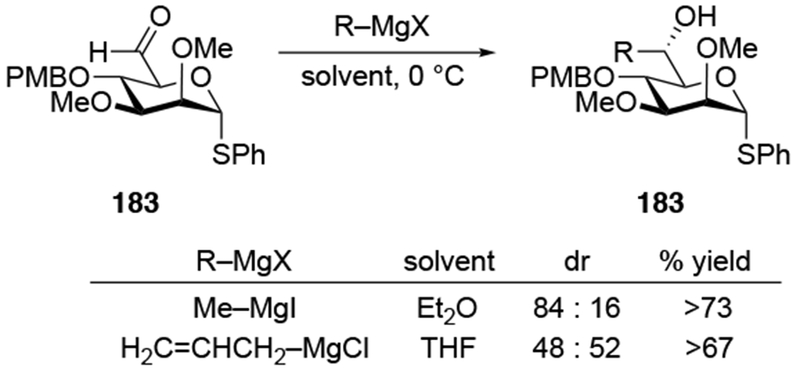

Addition of allylmagnesium halides to aldehydes derived from pyranosides show lower diastereoselectivities than additions of other organomagnesium reagents. Allylation of aldehyde 180 was not stereoselective (Scheme 74).165 Addition of methylmagnesium iodide to related aldehyde 183 gave product 184 in higher diastereoselectivity, however (Scheme 75).166 The difference in stereoselectivity was attributed to the difference in counterion for magnesium and for the difference in solvent. Comparing the results in Scheme 76 to the examples discussed in this review, however, suggest that the difference in selectivity for forming 184 is more likely the result of the nature of the nucleophile, with allylmagnesium reagents generally giving poor stereoselectivity in cases when other organomagnesium reagents are selective. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the counterion and ethereal solvent does not significantly affect the diastereoselectivity of a reaction between Grignard reagents and α-alkoxy carbonyl compounds.22

Scheme 74.

Scheme 75.

Scheme 76.

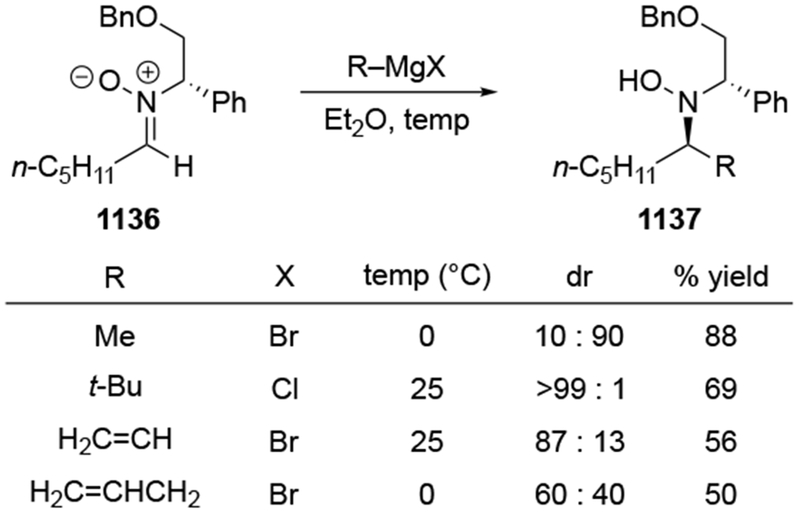

4.2.4.4. Allylations of α-Nitrogen Atom-Substituted Aldehydes

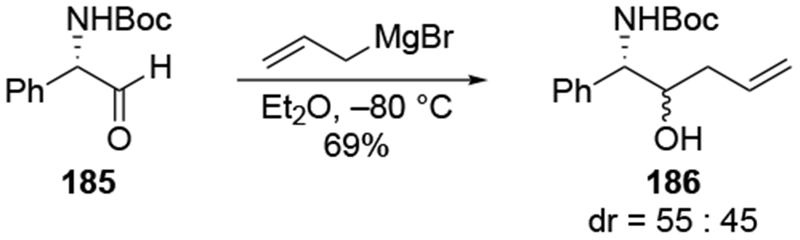

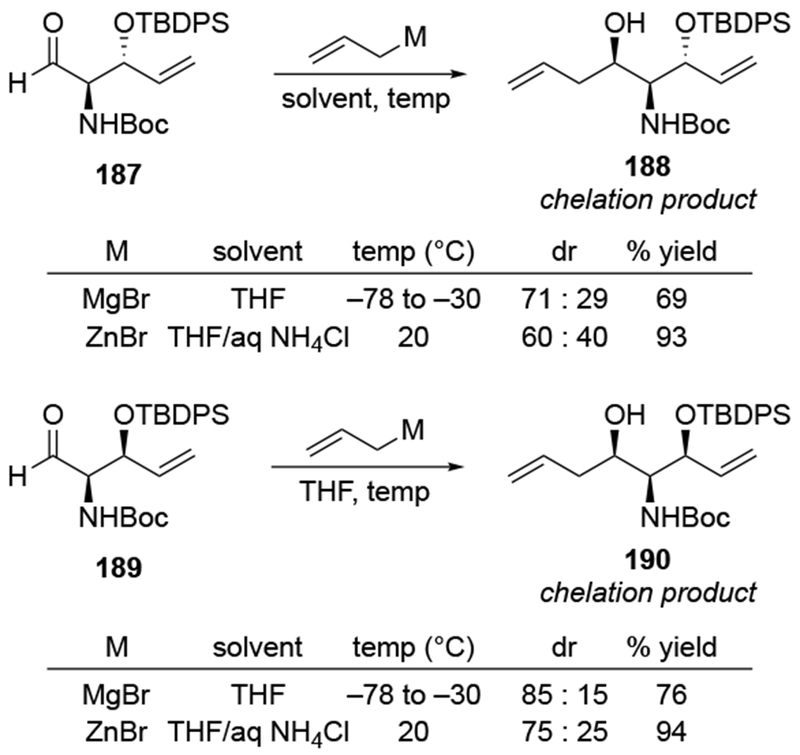

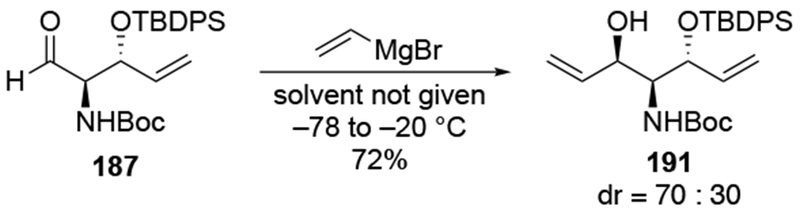

Similar efforts to achieve chelation-controlled addition of an allylmetal reagent using a nitrogen atom were met with limited success. Attempted allylation of a chiral aldehyde with a potentially chelating carbamoyl group (185) led to no selectivity (Scheme 76).167 Similarly, additions of either allylmagnesium or allylzinc reagents gave chelation-control product 188 in low diastereoselectivity (Scheme 77).168 In the case of diastereomeric ketone 189, the product expected by the chelation-control model (190) was formed with slightly higher stereoselectivity. In both of these examples, the allylmagnesium reagent formed the product more diastereoselectively than the allylzinc reagent, which is atypical (Scheme 70). These diastereoselectivities do not seem to be restricted to allylmetal reagents: additions of other organometallic reagents also proceeded with low diastereoselectivity (Scheme 78).169 Related reactions also occurred with low stereoselectivity.170, 171

Scheme 77.

Scheme 78.

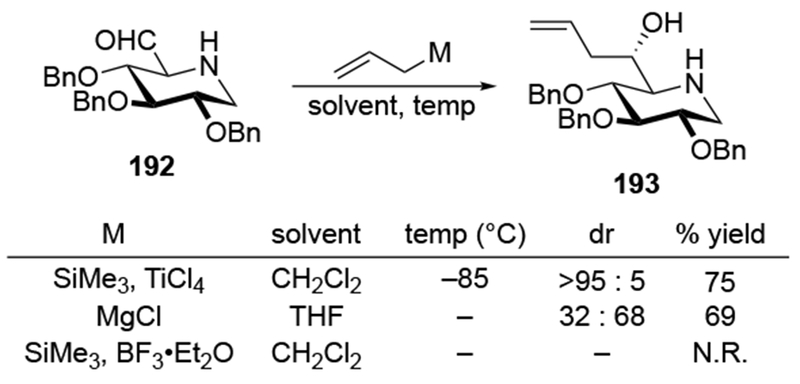

Reactions of amino sugars behaved much as additions with pyrans related to sugars (Scheme 79). Low selectivity was observed upon addition of allylmagnesium chloride to aldehyde 192.172 By contrast, allylation using allyltrimethylsilane with TiCl4 gave high diastereoselectivity. Reactivity of that nucleophile, however, depended upon the choice of Lewis acid.

Scheme 79.

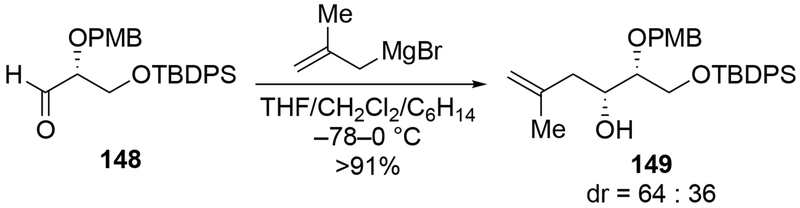

4.2.5. Additions to β-Substituted Aldehydes

4.2.5.1. Additions to β-Alkoxy Aldehydes

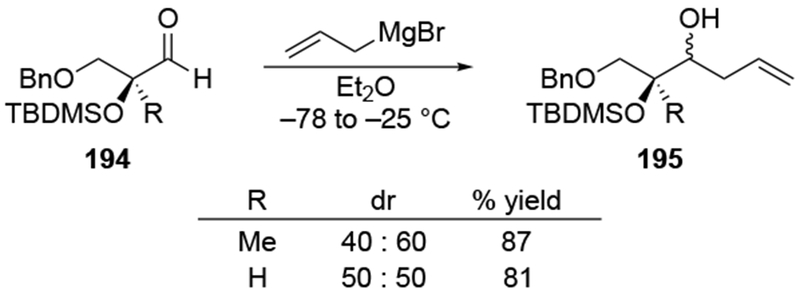

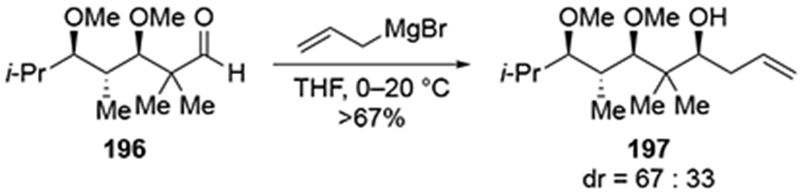

Similar to the additions to β-alkoxy ketones discussed in Section 4.2.3.1, additions to β-alkoxy aldehydes generally proceed with little diastereoselectivity. For example, with or without a fully substituted α-carbon atom, which would cause considerable steric hindrance towards nucleophilic attack, stereoselectivity was low (Scheme 80).173 Low stereoselectivity was also observed for another sterically congested aldehyde (Scheme 81).174.

Scheme 80.

Scheme 81.

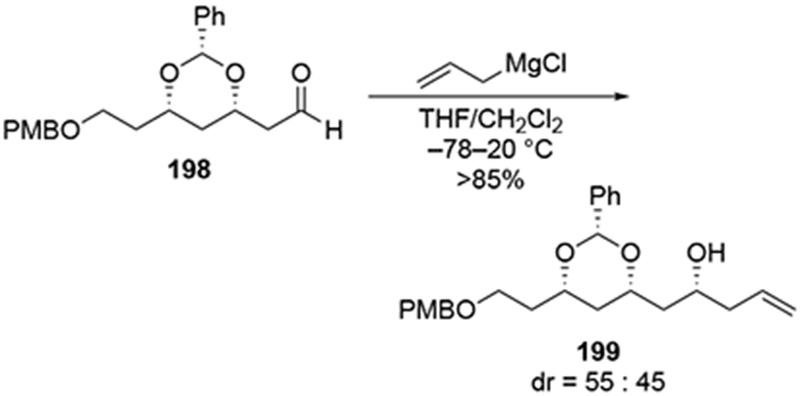

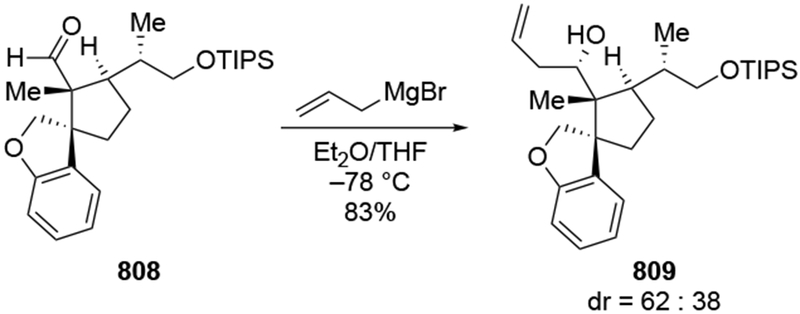

The challenges associated with allylation and the efforts to correct undesired configurations are illustrated for the β-alkoxy aldehyde 198 (Scheme 82).175,176 In the course of a natural product synthesis, it was necessary to achieve a diastereoselective synthesis of polyoxygenated products such as 199. The addition reactions of allylmagnesium halides were efficient, but they were not stereoselective. Efforts to repair this stereochemical course by oxidation of both diastereomers followed by hydride reduction were also ineffective, forming allylic alcohol 199 as an 80:20 mixture of diastereomers. The only reasonable solution was to employ chiral allyl silane reagents177 to control the new stereogenic center efficiently. Other authors have observed similarly low stereoselectivity in related systems, which could be repaired by an oxidation-reduction sequence.178 Stereochemical inversion through further elaboration to correct issues of stereochemistry is a common course of action made to remedy the low diastereoselectivity in reactions of allylmagnesium halides.

Scheme 82.

An aldehyde with a β-tetrahydropyranyl group also reacted with little selectivity in the presence of allylmagnesium bromide (Scheme 83).179 In the course of this synthesis, it was important to obtain this diastereomer selectively, but the authors note that efforts using chiral reagents to control the stereoselectivity were unsuccessful. In the end, a circuitous repair involved isolating the minor diastereomer and inverting the homoallylic configuration using a Mitsunobu reaction.180

Scheme 83.

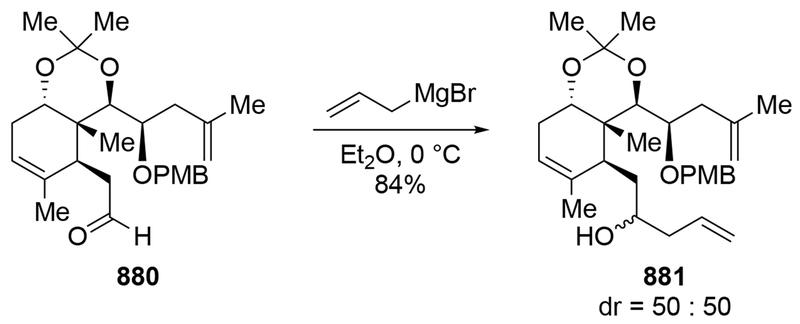

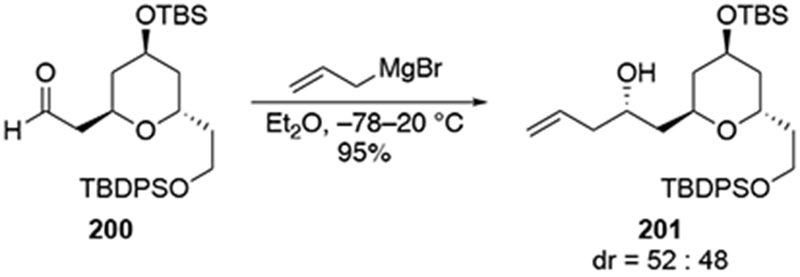

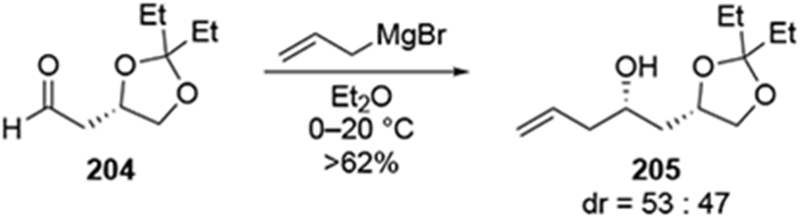

In the course of a natural product synthesis, it was shown that the allylation of a β-alkoxy aldehyde 202 by allylmagnesium chloride was unselective (Scheme 84).181 The undesired diastereomer was recycled to the desired diastereomer through a two-step sequence which inverted the configuration at the homoallylic position. Low diastereoselectivity was also observed in the addition of allylmagnesium bromide to a similar β-alkoxy aldehyde (204, Scheme 85).182 Although the use of chiral reagents (allylboranes, in this case) were effective at controlling the stereochemistry, the authors found it operationally easier, considering the scales of their reactions, to use the readily available allylmagnesium bromide despite the low diastereoselectivity that resulted. The two diastereomeric alcohols of 205 were first separated, and then the undesired stereoisomer was converted to the desired alcohol by a Mitsunobu inversion followed by ester hydrolysis.

Scheme 84.

Scheme 85.

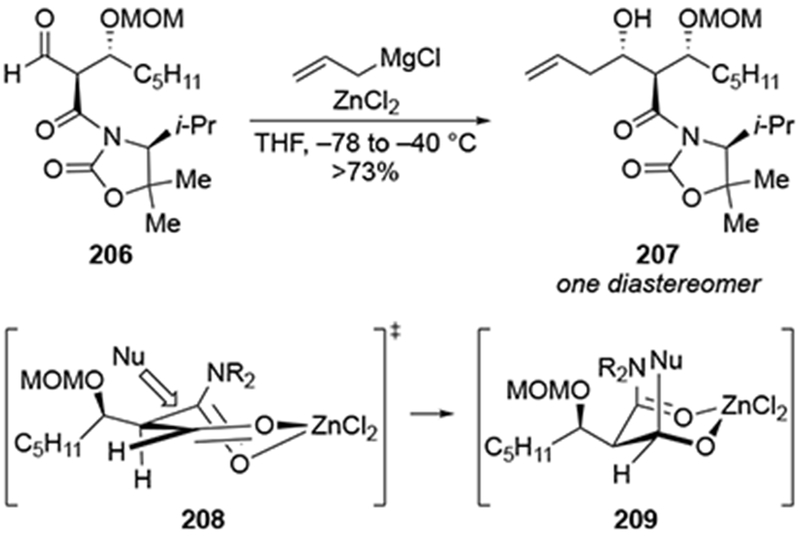

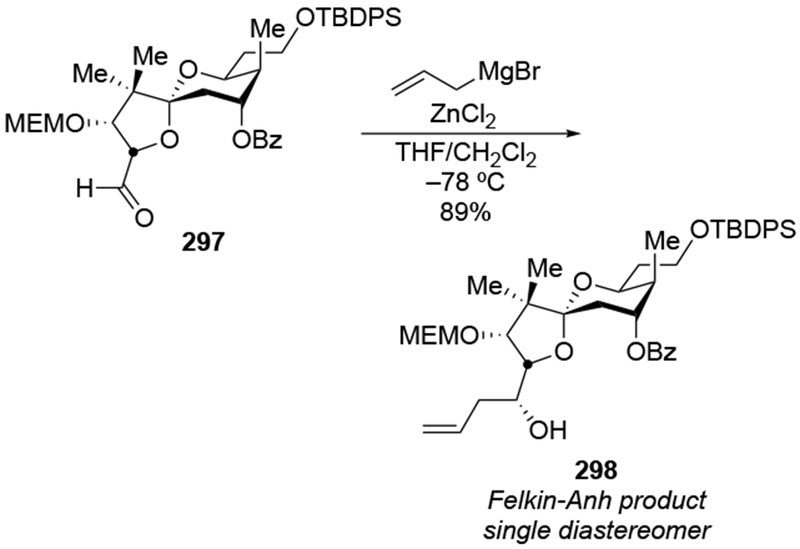

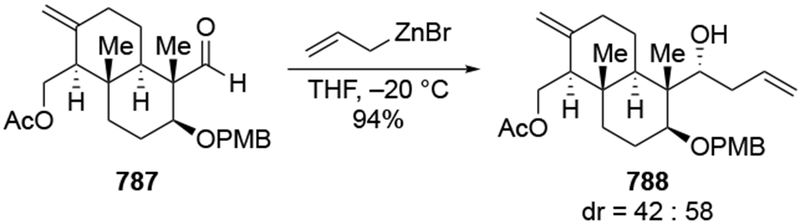

Chelation-controlled additions to β-substituted aldehydes can be achieved using other metal salts as additives.183 The addition of ZnCl2 to the addition of aldehyde 206 led to a completely stereoselective reaction (Scheme 86). No experiment without the use of zinc salts was reported, so the outcome of addition of the magnesium reagent is not known. Although the authors did not comment on the origin diastereoselectivity, it is consistent with addition through a transition state resembling 208 where chelation occurs to the carbonyl oxygen atom in the β-position rather than the β-alkoxy group.

Scheme 86.

4.2.5.2. Additions to β-Silyloxy Aldehydes

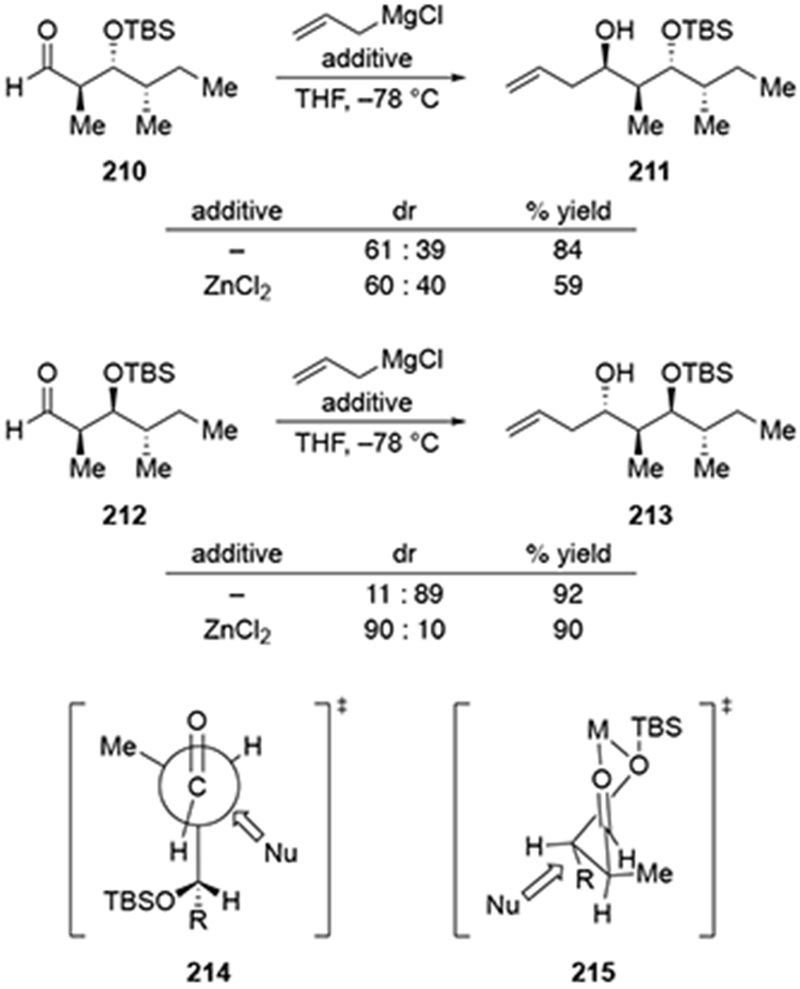

Efforts toward the synthesis of a natural product and its analogues led to investigations of methods to obtain the product expected by chelation-control in the allylation of β-silyloxy aldehydes (Scheme 87).184 Chelation-controlled selectivity could not be achieved with the β-silyloxy aldehyde 210 using allylmagnesium or allylzinc reagents. By contrast, additions to aldehyde 212 were diastereoselective. The reaction with allylmagnesium chloride formed the diastereomer of product 213. This diastereomer is formally the product of addition through a Felkin–Anh transition state. Instead, this product was likely formed through a transition state resembling 214, which is consistent with the modified Cornforth model.185 This model is justified because aldehydes 210 and 212 resemble aldehydes investigated by Evans to understand how substituents at the α- and β-positions of carbonyl compounds influence the diastereoselectivities of addition reactions.186 Alternatively, in the presence of zinc salts, a chelate resembling 215 would be favored, leading to the illustrated product.

Scheme 87.

Addition to aldehyde 212 formed the desired diastereomer of 213 expected by the chelation-control model in the presence of ZnCl2. This reaction may or not involve transmetallation from magnesium to zinc, considering that the zinc salt was first combined with the aldehyde followed by addition of the organomagnesium reagent. As a result, transmetallation would need to compete with addition to the carbonyl group. Because complexation of alkylzinc halides to α-silyloxy ketones has been established,89,187 it is possible that product 213 could be obtained by chelation, as illustrated in transition state 214.

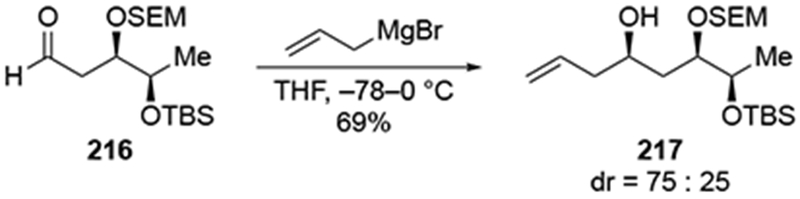

Additional experiments provide added justification for the above analysis. When a group is not present at the α-position to reinforce stereochemistry, as depicted with aldehyde 216 below (Scheme 88), allylation was less selective than the “matched” case (212) but more selective than the “mismatched” case (210) shown in Scheme 87.188 It is also worth noting that in this system the use of a chiral allylborane reagent or an allylstannane reagent in the presence of a Lewis acid also did not afford product 217 with high stereoselectivity.

Scheme 88.

4.2.5.3. Additions to β-Nitrogen-substituted Aldehydes

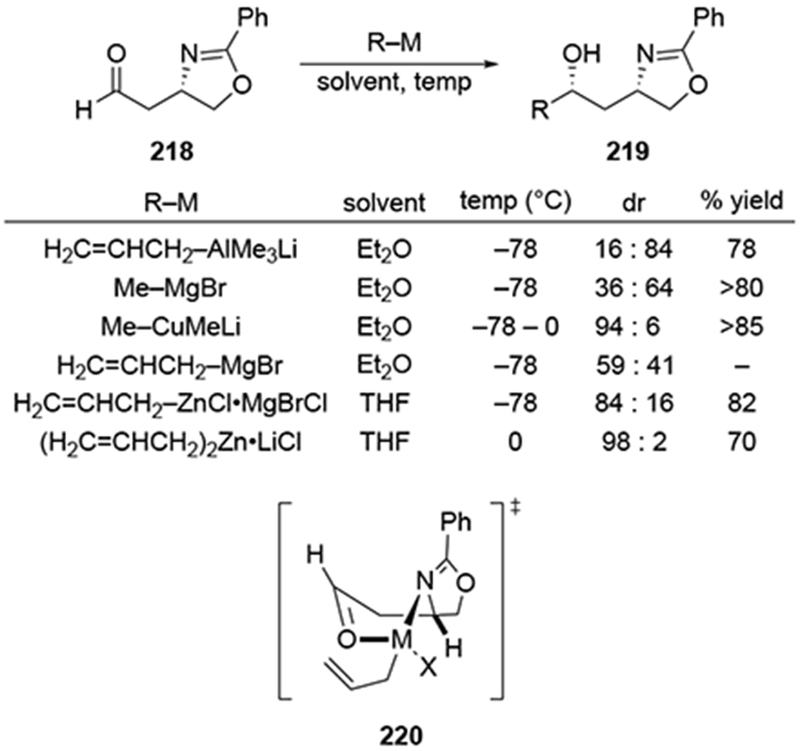

An example of β-chelation was observed in the case of aldehyde 219, which contains a β-nitrogen atom capable of metal complexation (Scheme 89).189,190 Additions of both MeMgBr and allylmagnesium bromide led to low stereoselectivity. In contrast to reactions with simpler systems,191 the methyl cuprate reagent gave low diastereoselectivity. Selectivities for the allylation reaction could be improved by transmetallation to zinc. The stereochemical outcome for addition of the β-chelation product was different than for addition of an allylzinc reagent to a β-alkoxy carbonyl compound, however.192 It was argued that a boat-like chelate was favored in this system because the nitrogen atom is trigonal planar. Subsequent intramolecular delivery of the nucleophilic group would occur as illustrated in transition state 220. By comparison, the aluminate complex would react through a more standard cyclic chelating transition state, thus favoring the opposite product.

Scheme 89.

4.2.6. Additions to Aldehydes with Distant Chelating Groups

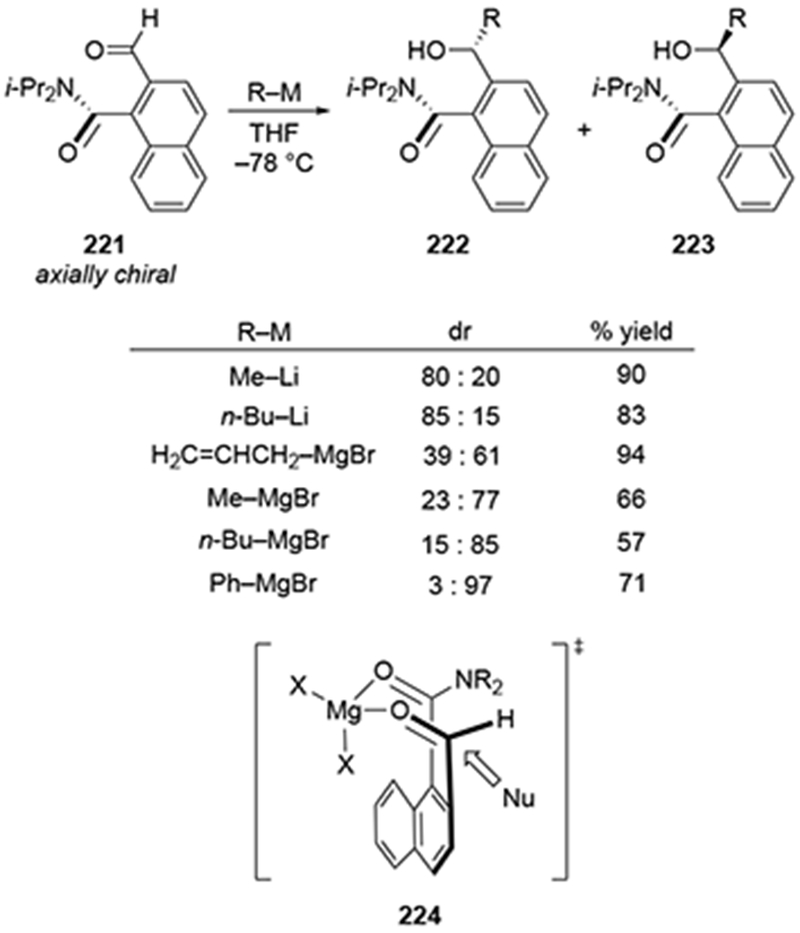

Groups other than alkoxy substituents can be used to control the stereoselectivity of addition to carbonyl compounds from remote positions using chelation. Axially chiral aldehyde 221 underwent diastereoselective reactions with a number of different nucleophiles (Scheme 90).193 In the case of organolithium reagents, it was believed that chelation was not possible, but in the presence of magnesium ions, chelation could occur (as illustrated in transition structure 224), leading to the diastereoselective formation of alcohol 222. Selectivity was moderate with methyl- and n-butylmagnesium reagents, but phenylmagnesium bromide formed 223 with a diastereomeric ratio of 97:3. As with other reactions, allylmagnesium reagents underwent this reaction with low diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 90.

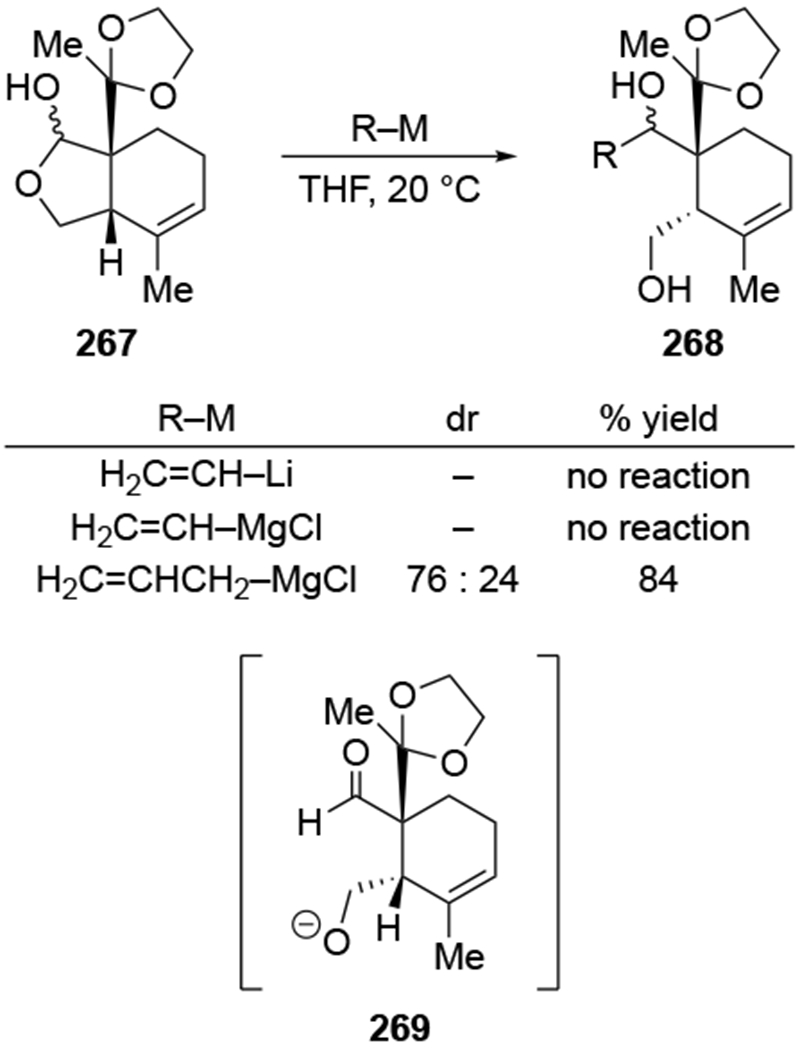

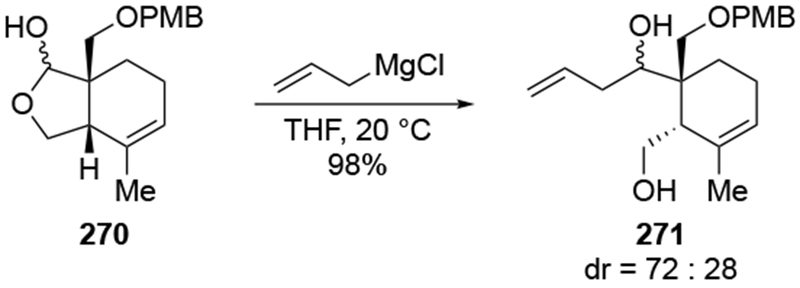

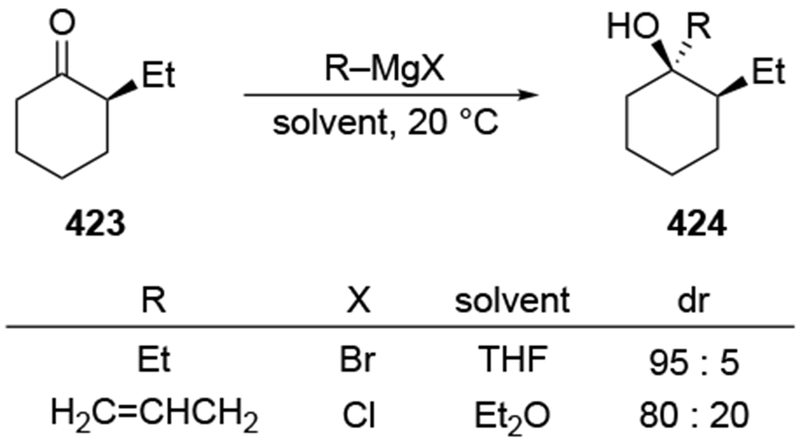

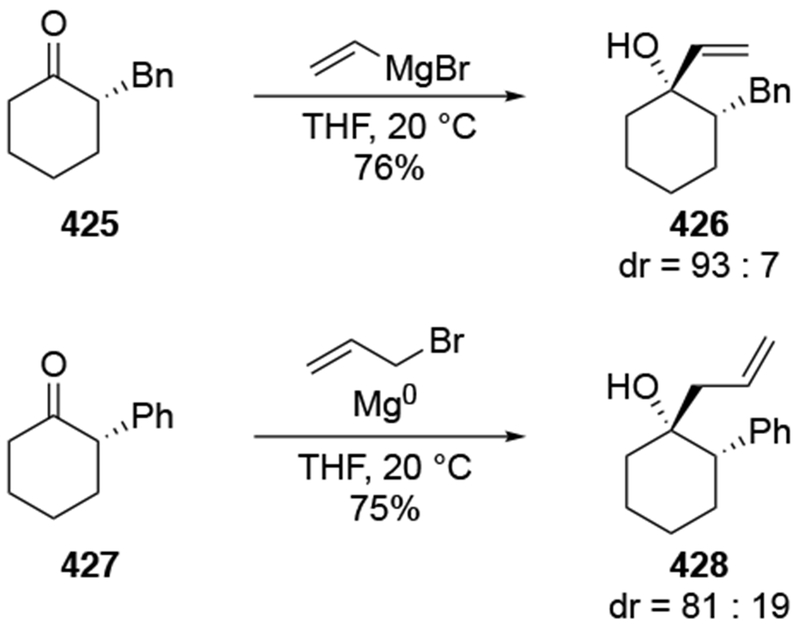

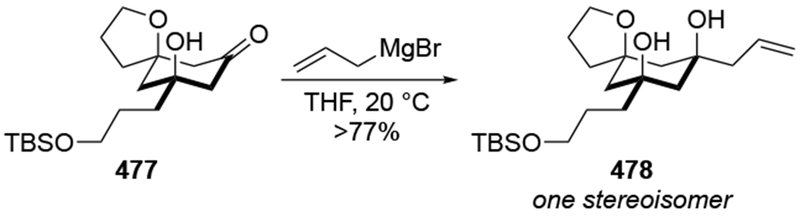

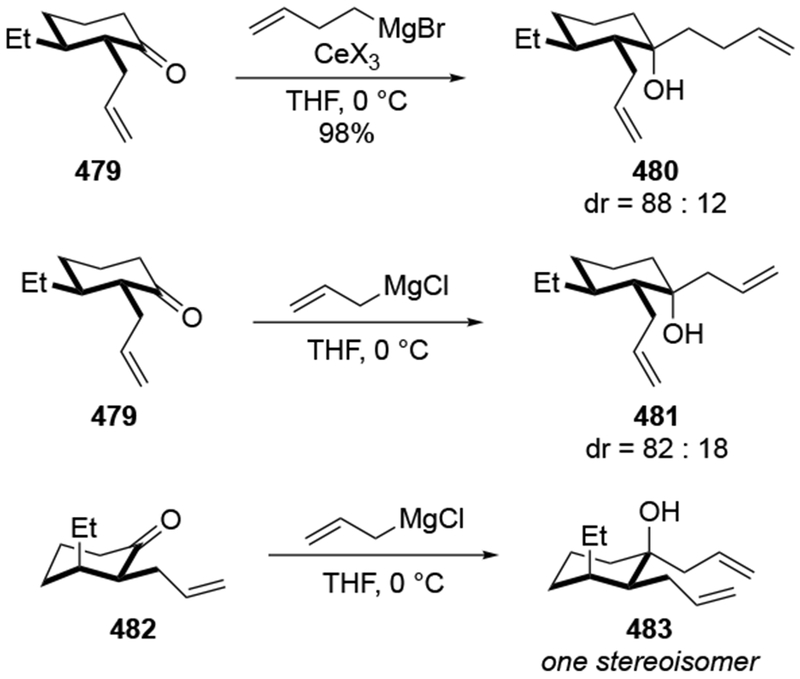

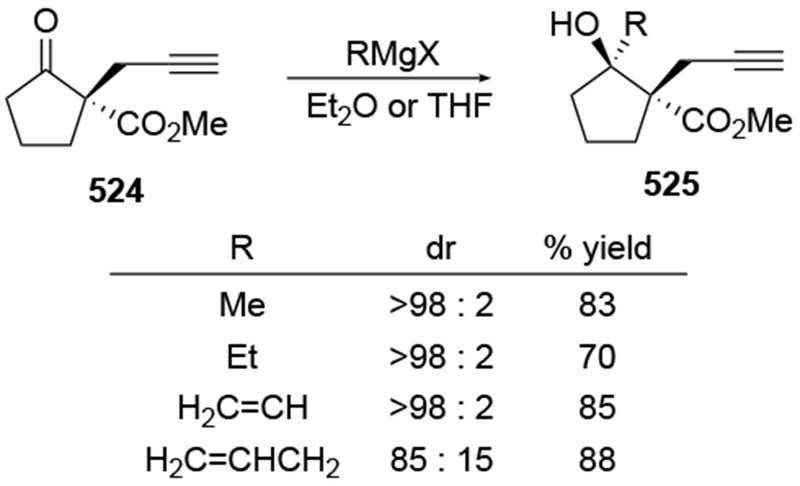

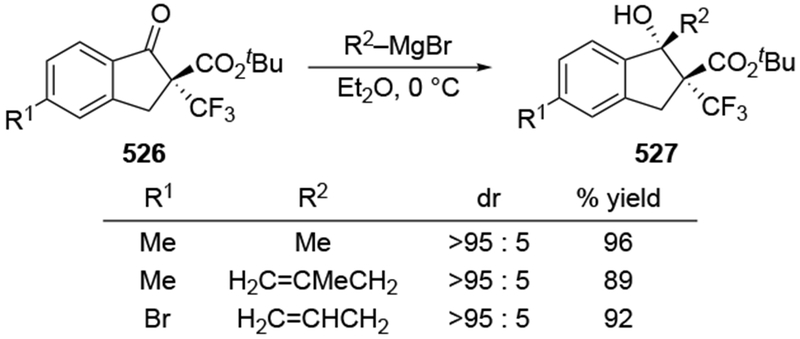

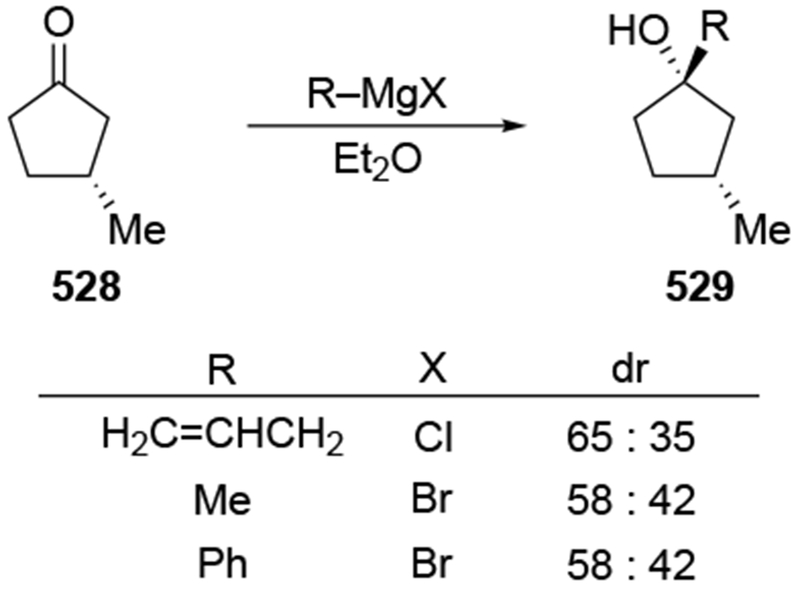

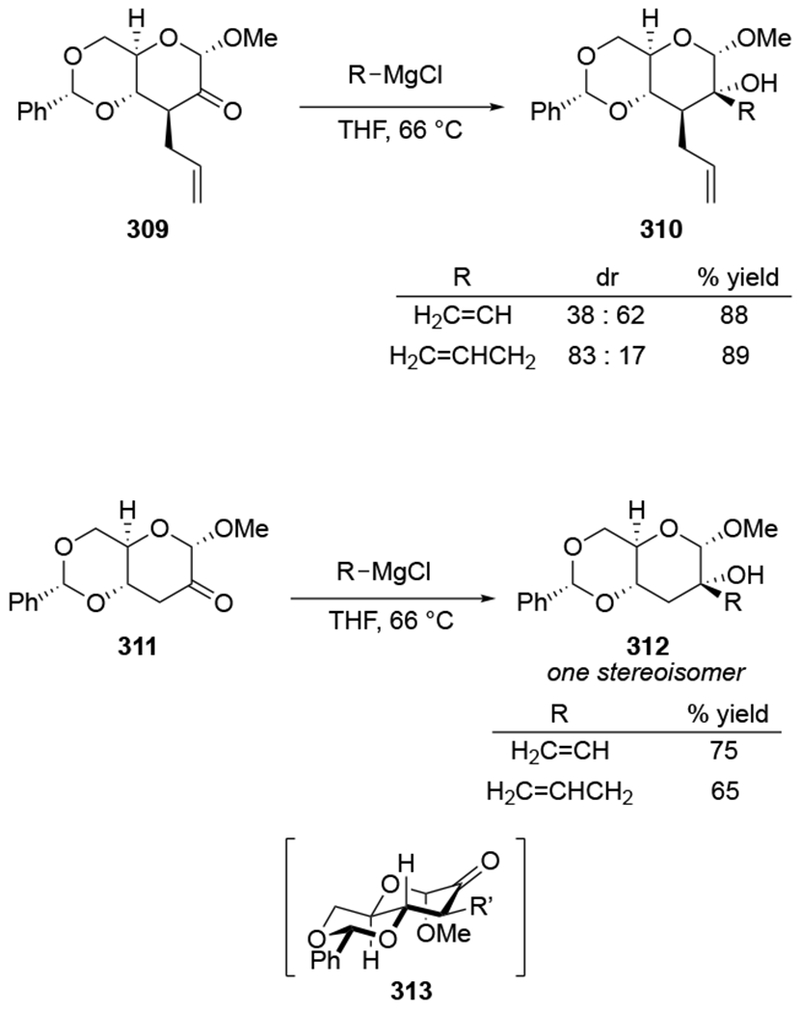

4.3. Additions to Cyclic Ketones

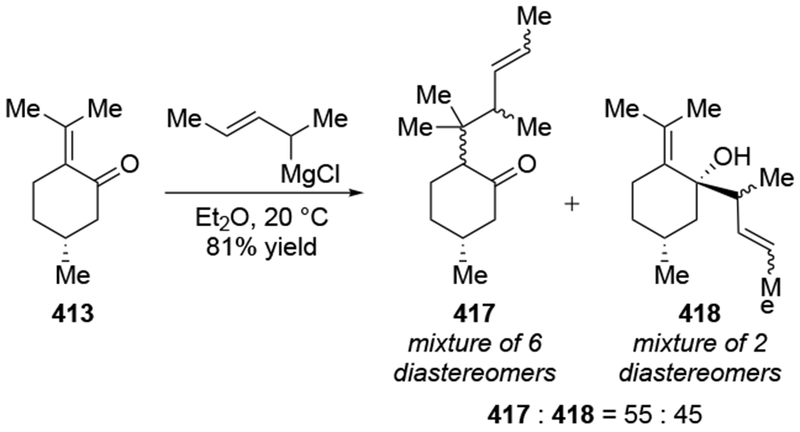

4.3.1. Alkoxy-substituted Cyclic Ketones

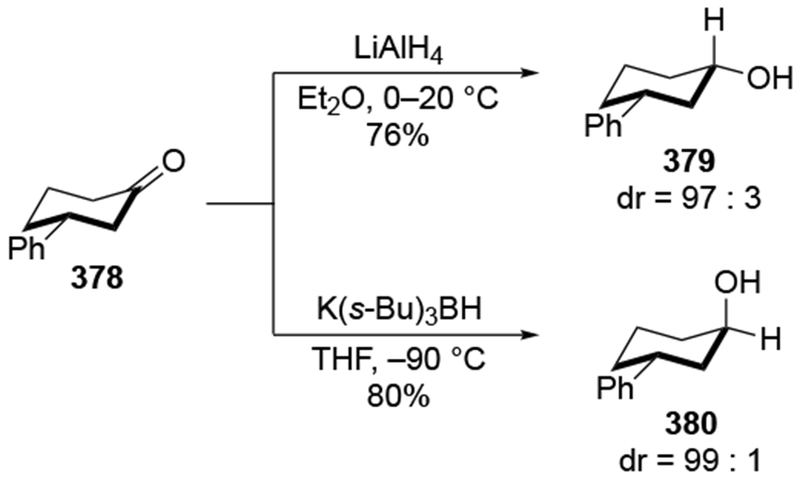

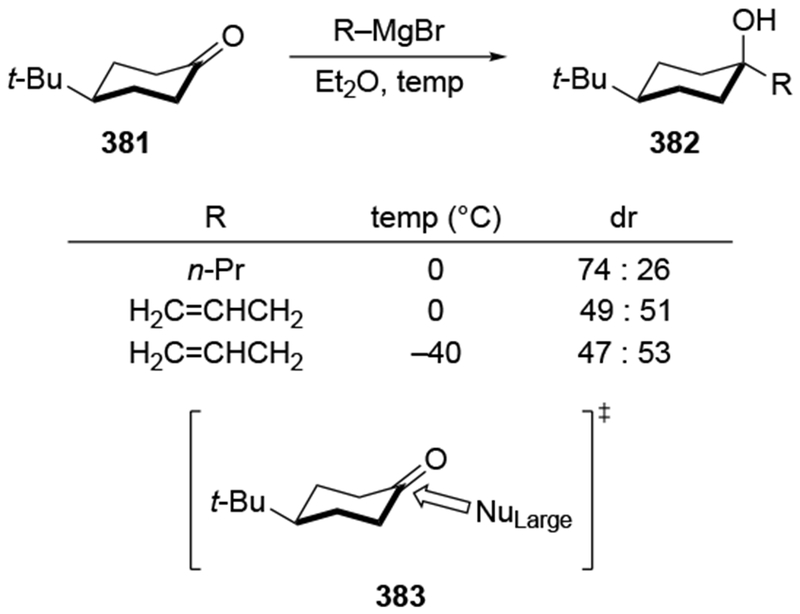

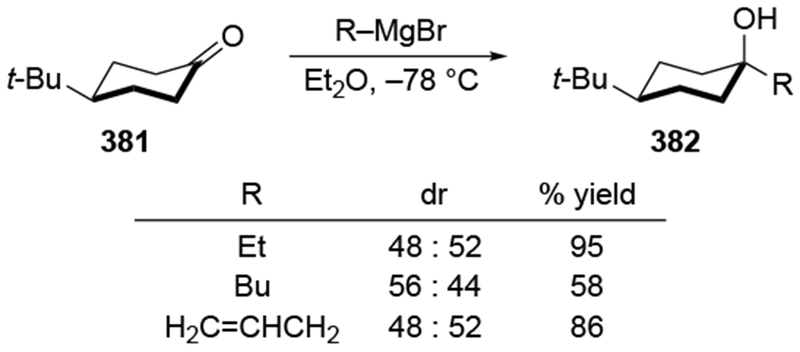

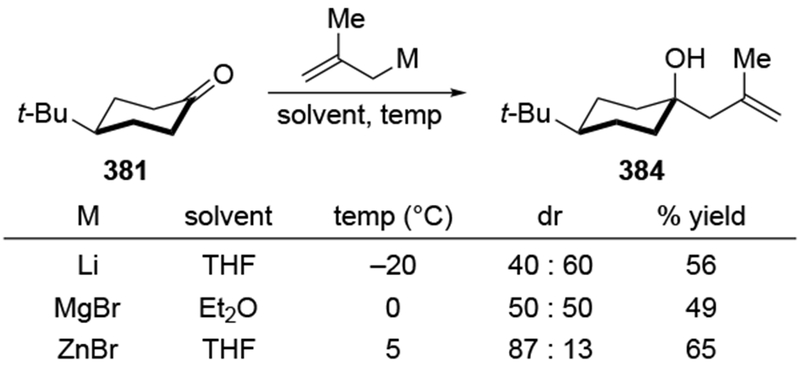

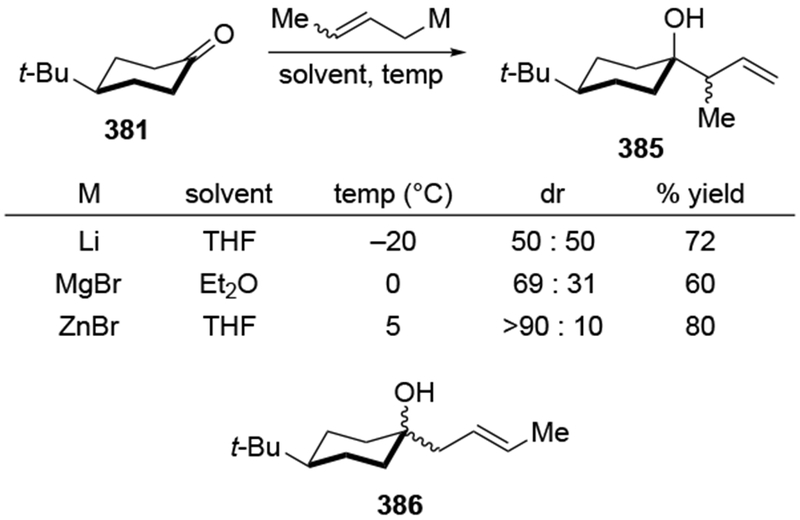

The stereochemical outcome for nucleophilic addition to cyclic ketones is often influenced by distinct factors from their acyclic counterparts. Although they were among the early examples studied when stereochemical models such as the work of Felkin were originally formulated,194 these systems are more complicated than those of acyclic ketones. Bond rotation is restricted in acyclic ketones, and torsion angles and torsional strain exert strong influences upon the preferences for nucleophilic attack.71 Approach of the nucleophile to one face of the carbonyl could be favored judging by the steric environment, but torsional strain in the transition state could favor the opposing side. Also, distinct electronic effects can operate, leading to selectivities that need to be analyzed separately.65,195 It is not essential to master these subtleties to notice the disparate reactivity profile of allylmagnesium reagents compared to other Grignard reagents.

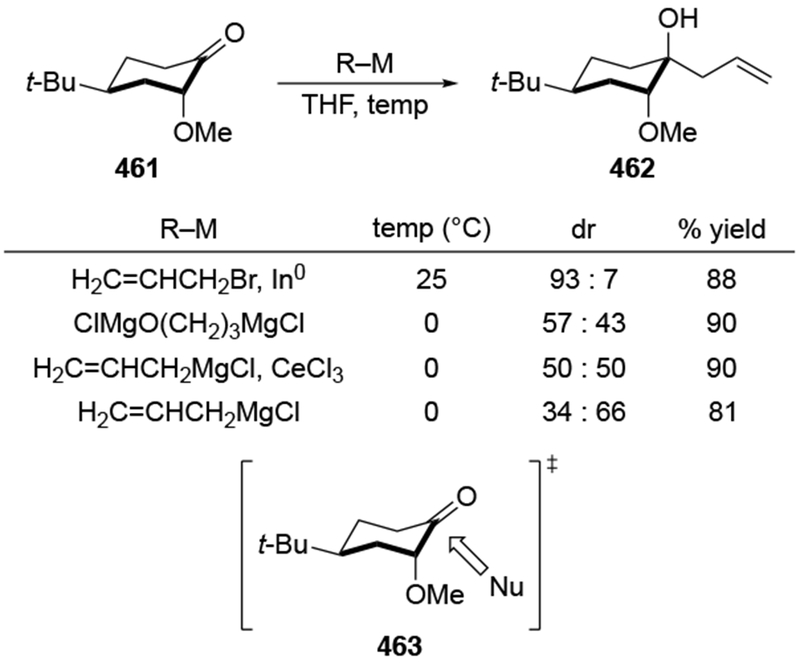

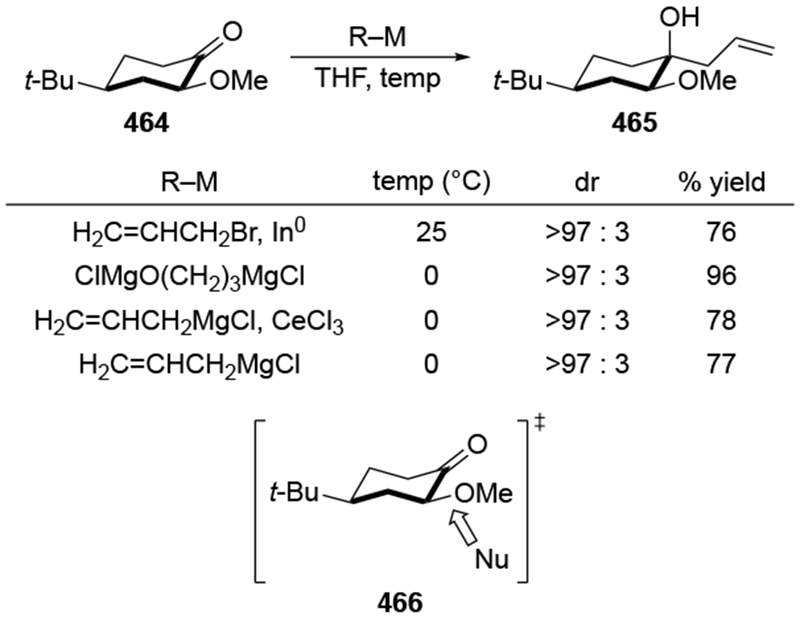

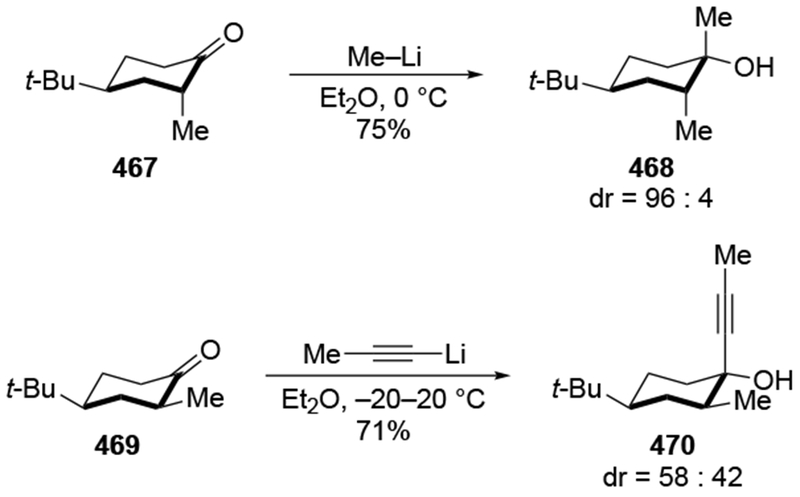

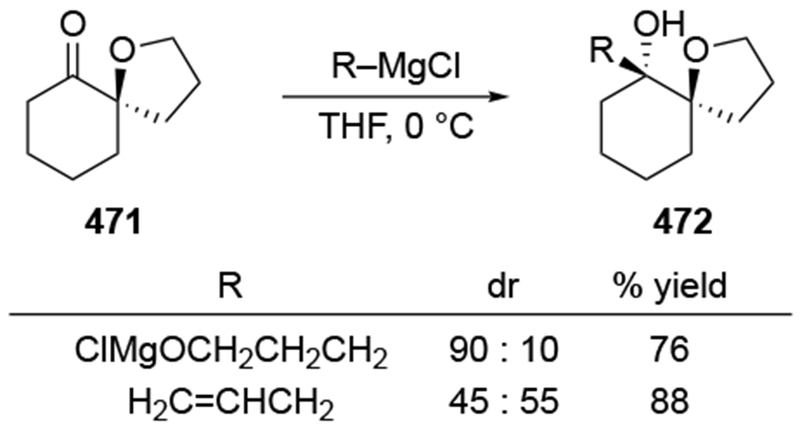

4.3.1.1. α-Oxygenated Six-Membered-Ring Ketones

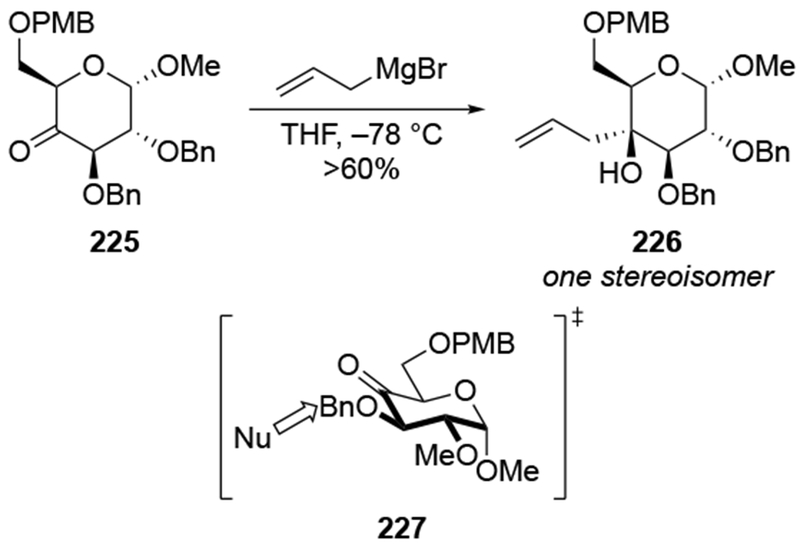

In some cases, the diastereoselectivities for allylations of alkoxy-substituted cyclohexanones can be quite high using Grignard reagents. Nucleophilic addition to highly substituted α-alkoxy ketone 225 proceeded with high selectivity for addition anti to the alkoxy group (Scheme 91).196 Whether this reaction is the result of chelation-controlled addition or simply addition to the lowest-energy conformer (227) from the sterically more accessible side cannot be established. Nevertheless, this example provides a good comparison for other highly functionalized, six-membered-ring ketones.

Scheme 91.

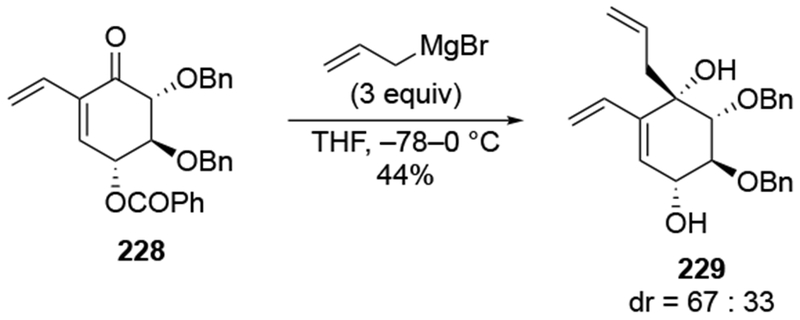

The presence of an α-alkoxy group is not sufficient to observe selectivity, however. Addition to substituted cyclohexenone 228 occurred with low selectivity for addition anti to the α-benzyloxy group, at the same time removing the benzoyl protecting group (Scheme 92).197 Nevertheless, the major isomer could be converted to a substrate that underwent an efficient intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction leading to the scaffold of a natural product.

Scheme 92.

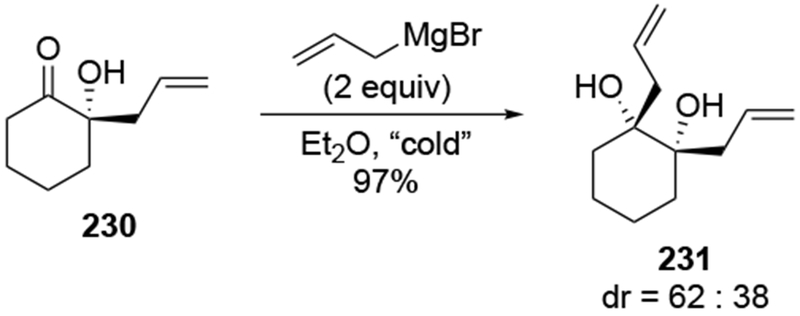

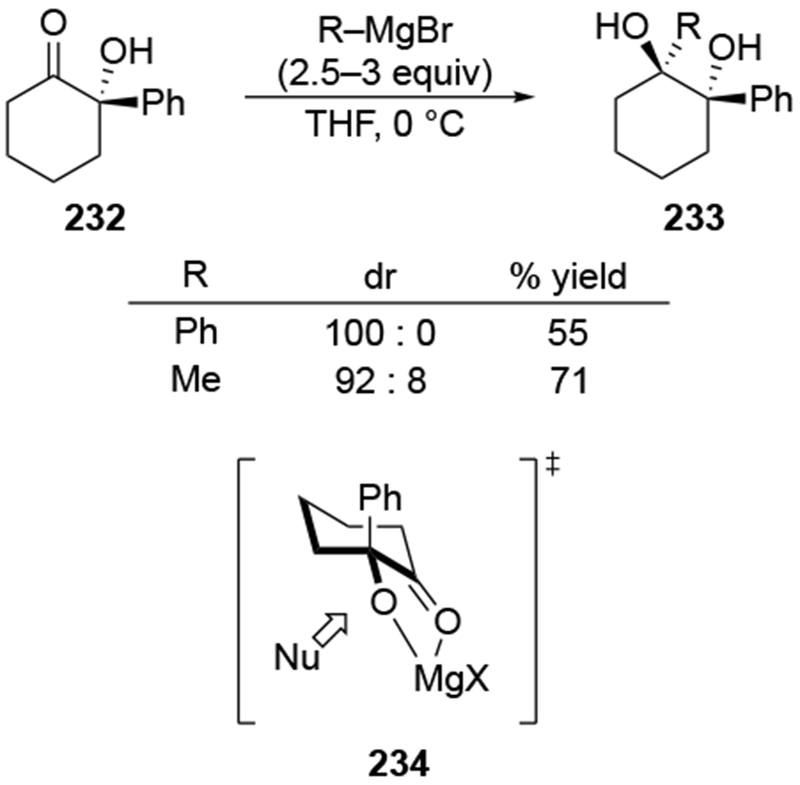

Another example suggests that allylation with chelation-controlled selectivity should not be expected in cyclic ketones. Ketone 230 (Scheme 93).198 contains an α-hydroxyl group that might be expected to undergo highly stereoselective reactions considering that the presence of hydroxyl groups can lead to high selectivity for the chelation-control product in acyclic systems (as illustrated by, for example, Scheme 36). Instead, low selectivity was observed. By comparison, additions of phenyl and methyl Grignard reagents to α-hydroxy ketone 232 were highly stereoselective (Scheme 94).199 likely by formation of chelate 234 and addition from the face not blocked by the axial phenyl group.

Scheme 93.

Scheme 94.

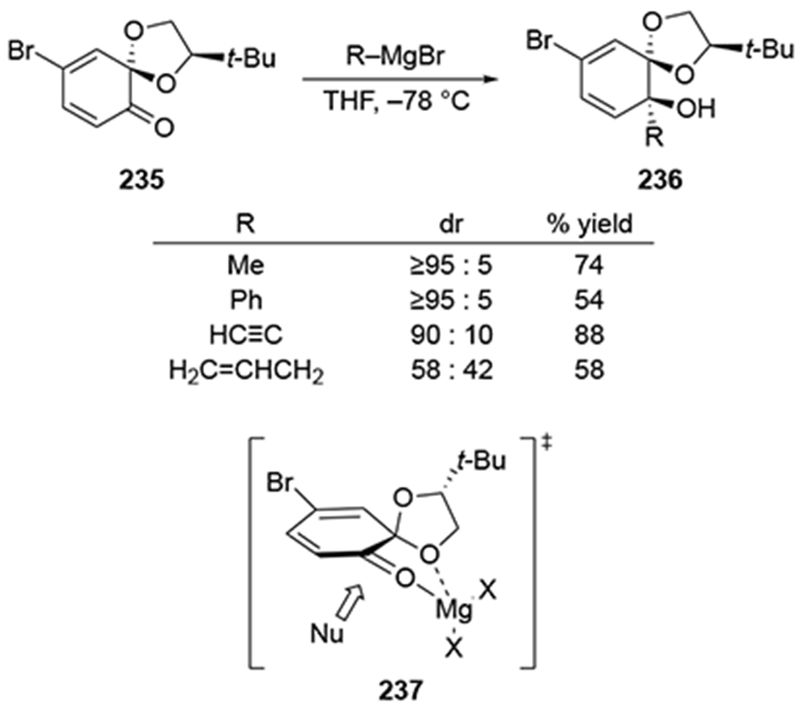

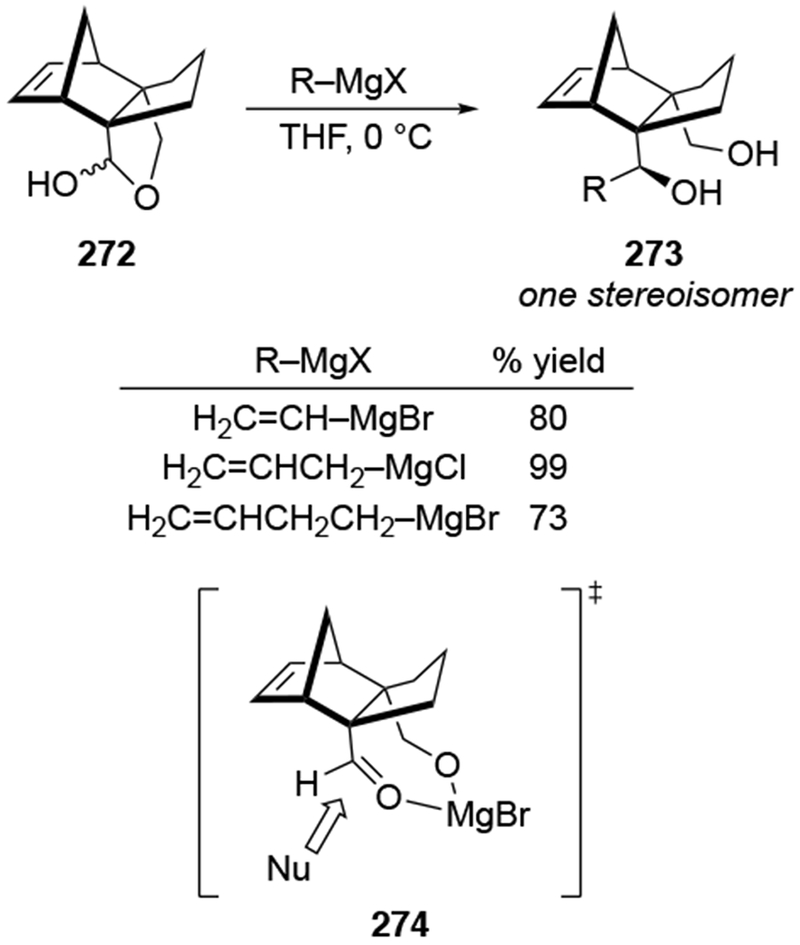

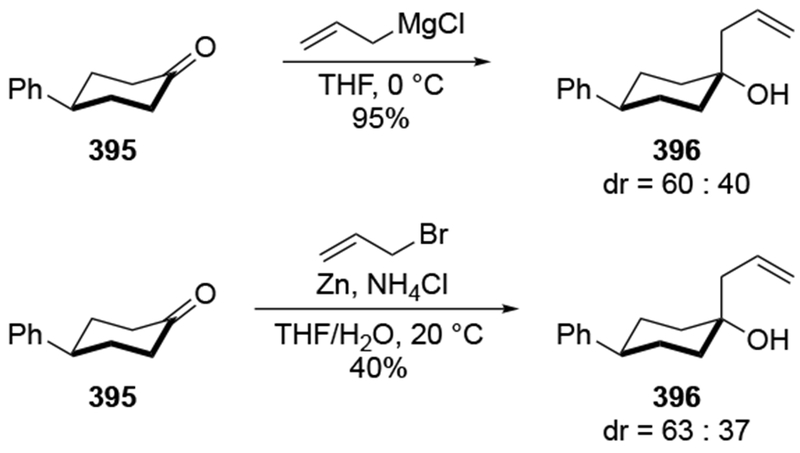

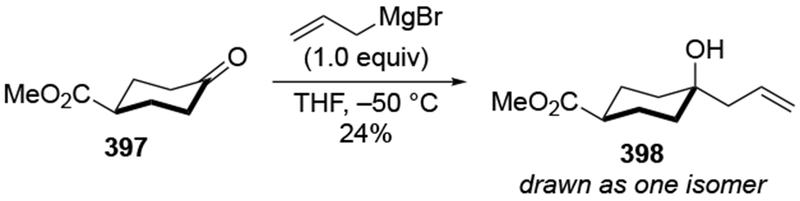

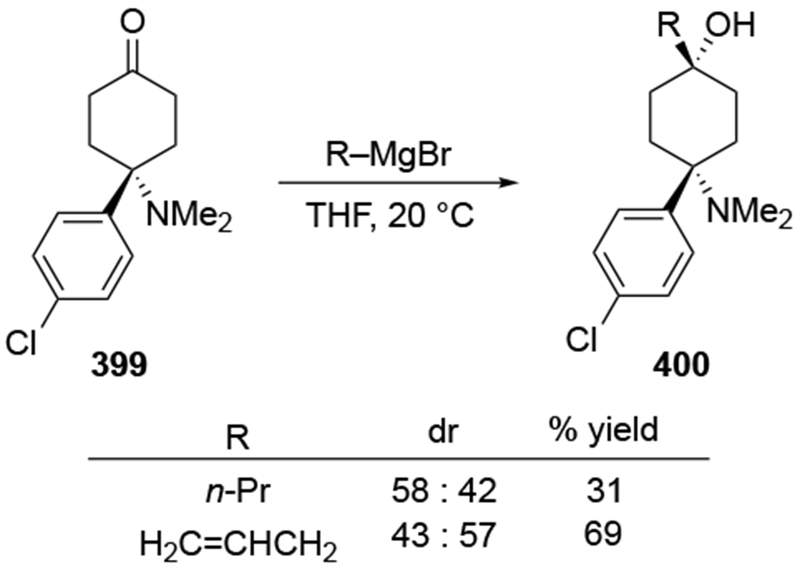

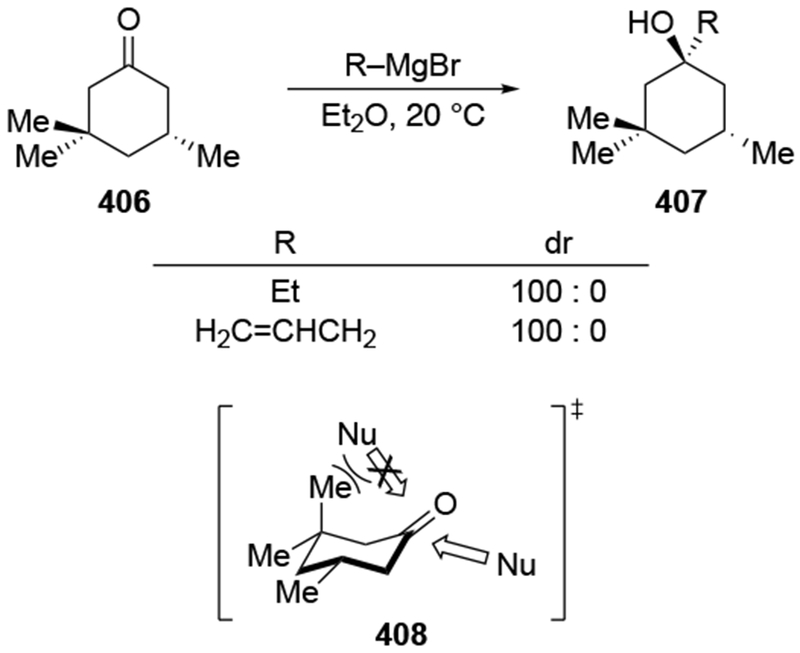

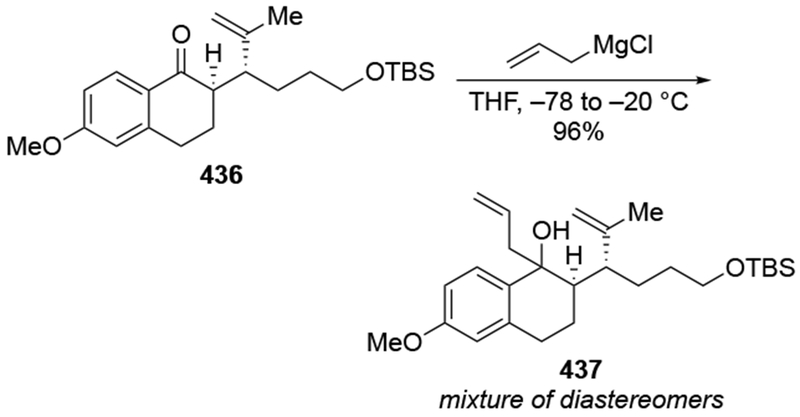

Although the examples shown in Schemes 91 and 92 did not include a direct comparison between an allylmagnesium reagent and other organomagnesium reagents, it appears that, just as for acyclic systems, allylmagnesium reagents add to cyclic ketones with low selectivity (Scheme 95).200 Additions of several organomagnesium bromides to ketone 235 occurred with high stereoselectivity, favoring a product that could arise through addition to the more accessible face of the multicyclic chelate 237. On the other hand, allylmagnesium bromide added with no stereoselectivity. This difference in selectivity mirrors other losses of diastereoselectivity with allylic organomagnesium reagents compared to nonallylic organomagnesium reagents.17,22,23 Considering that this cyclohexadienone structure is likely to be highly flattened, it might be anticipated that the two faces of the carbonyl group should show little stereochemical differentiation without chelation. Therefore, the allylmagnesium reagent, which does not benefit from rate acceleration conferred by chelation,22 added with little stereochemical discrimination.

Scheme 95.

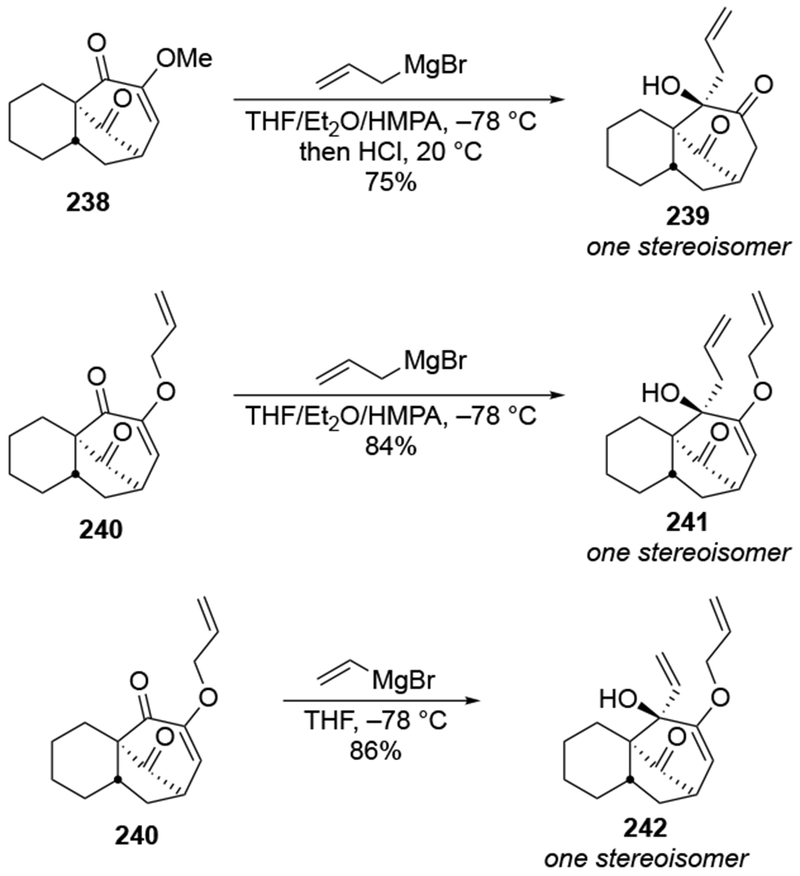

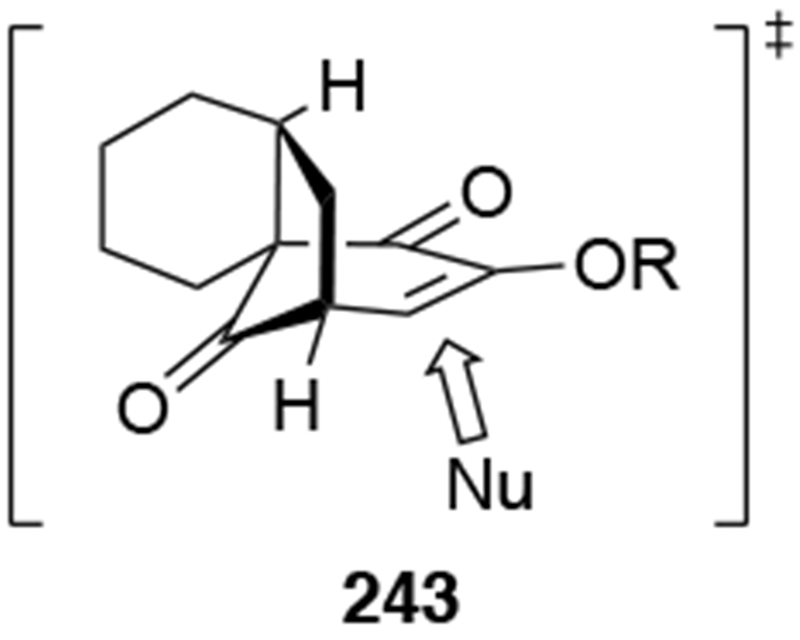

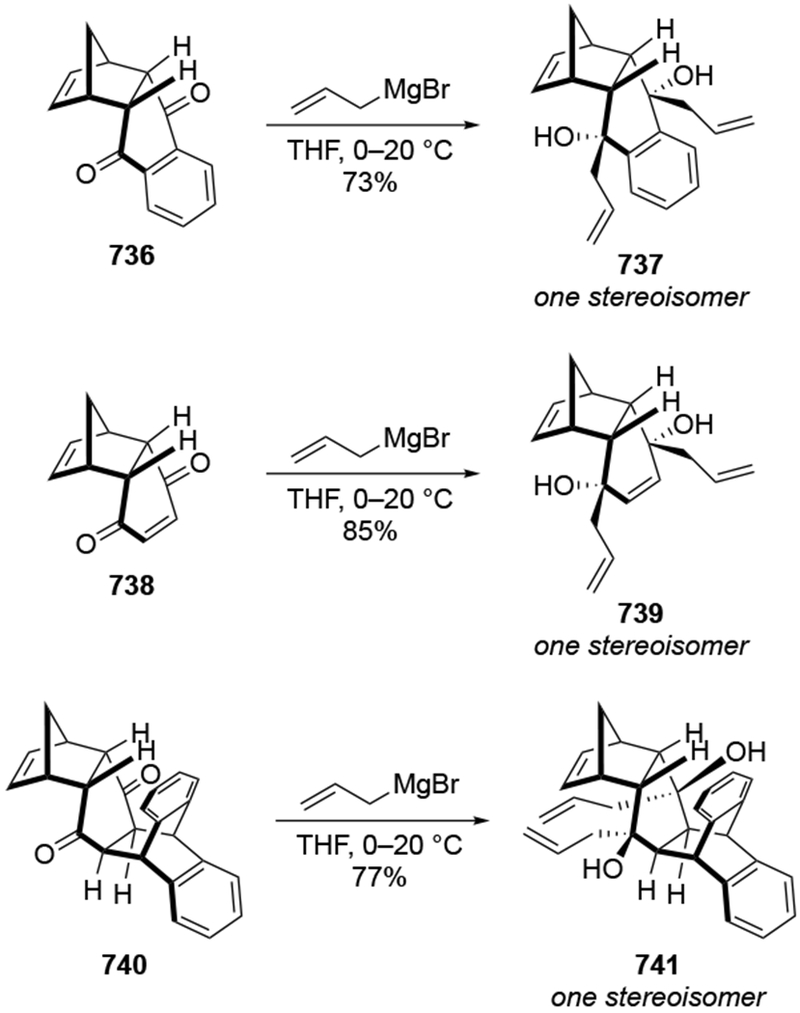

Chelation in bridged six-membered ring ketones has been invoked both to explain stereoselectivity and reactivity of ketones.201. For the bicyclic ketones 238 and 240, attack of allylmagnesium bromide occurred at the conjugated carbonyl group instead of the hindered carbonyl group on the one-atom bridge (Scheme 96). It was suggested that the addition to the conjugated carbonyl group was the result of chelation to the nearby alkoxy group, which would be consistent with the kinetic acceleration conferred by chelation.54 The authors did not discuss why HMPA was used as the solvent, which should complex tightly to magnesium, likely breaking up dimeric species202 and disrupting chelation.

Scheme 96.

An alternative explanation for the chemoselectivity and stereoselectivity of this addition relies on the overall structure of this bicyclic ketone. The carbonyl group on the three-carbon bridge appears to be more sterically accessible than the carbonyl group on the one-carbon bridge (the reactions of allylmagnesium reagents with ketones with the carbonyl group in a bridge will be discussed in Section 6.8). Addition to the bottom face of this ketone, which should be less hindered considering that longer bridge with the additional ring occupies the top face, should lead to stereoselectivity (Scheme 97).

Scheme 97.

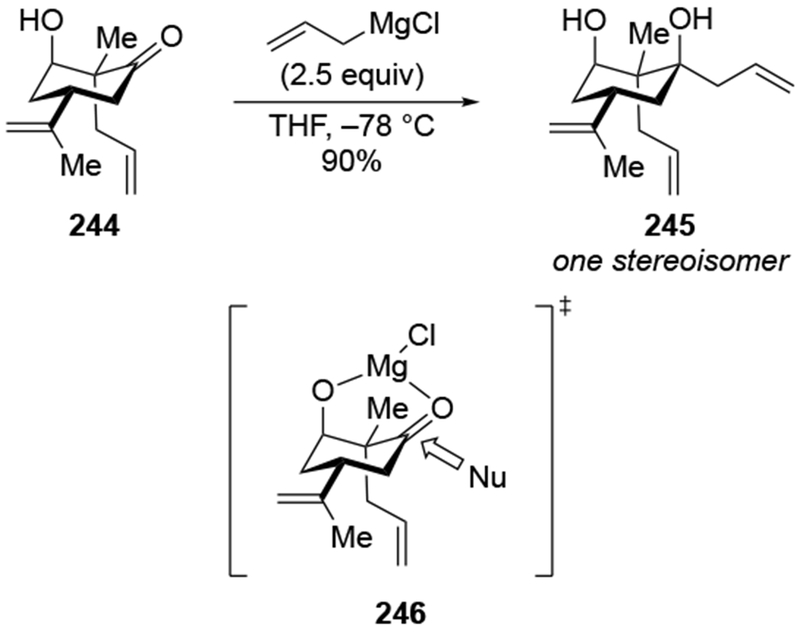

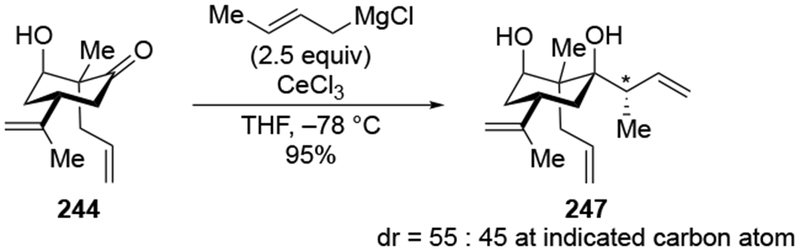

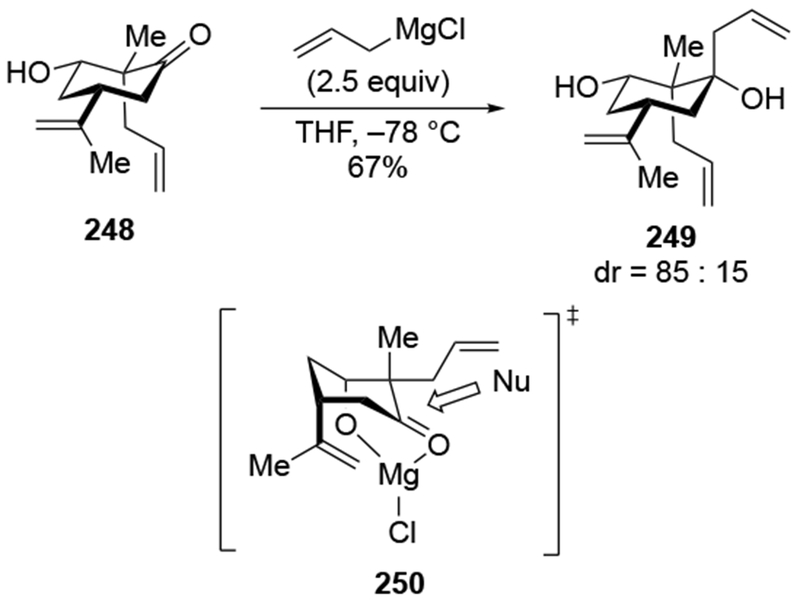

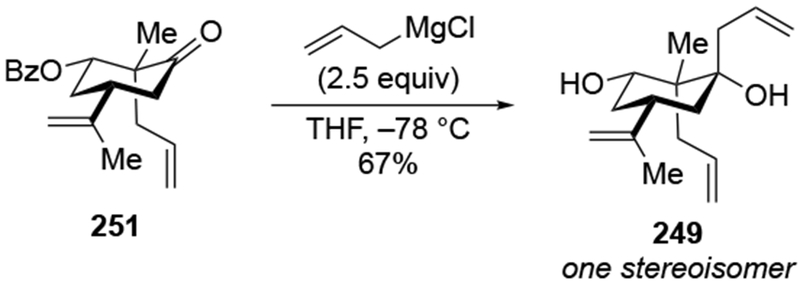

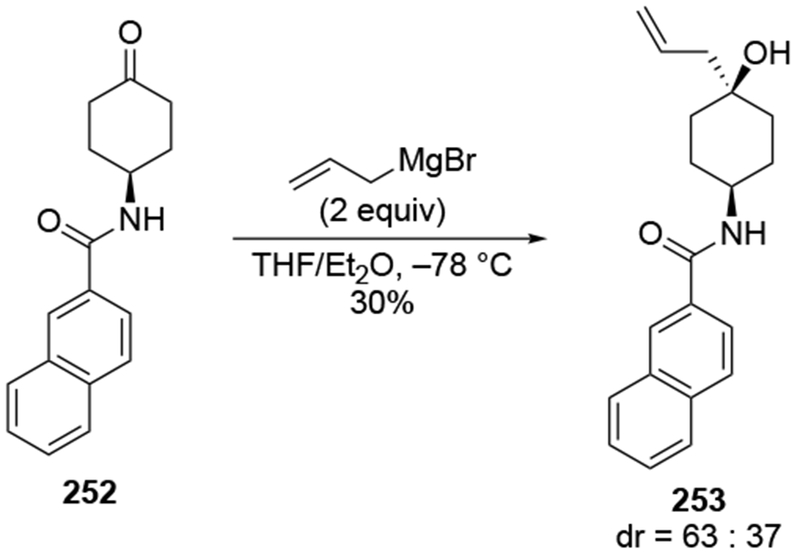

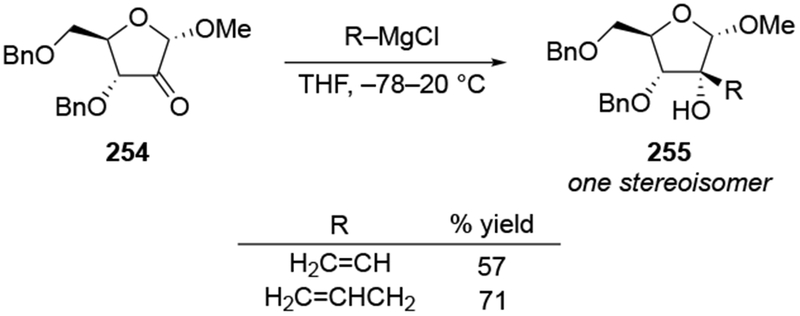

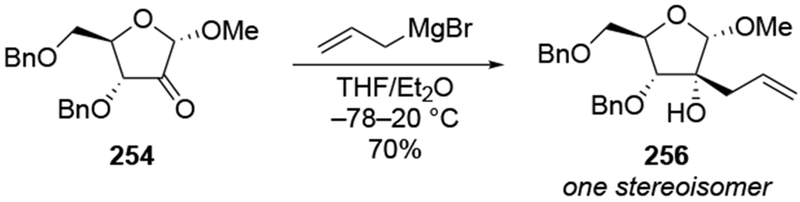

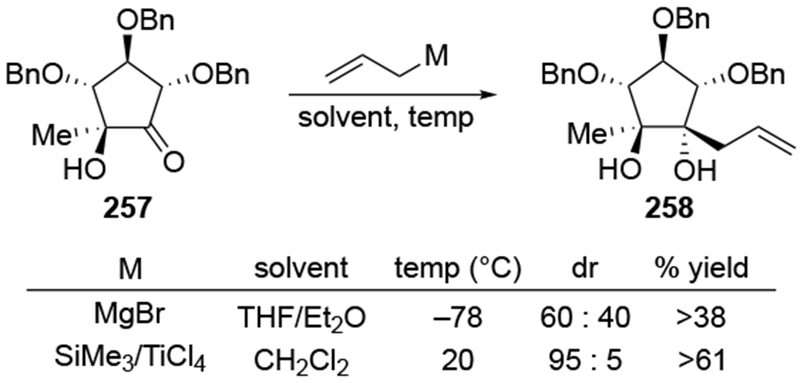

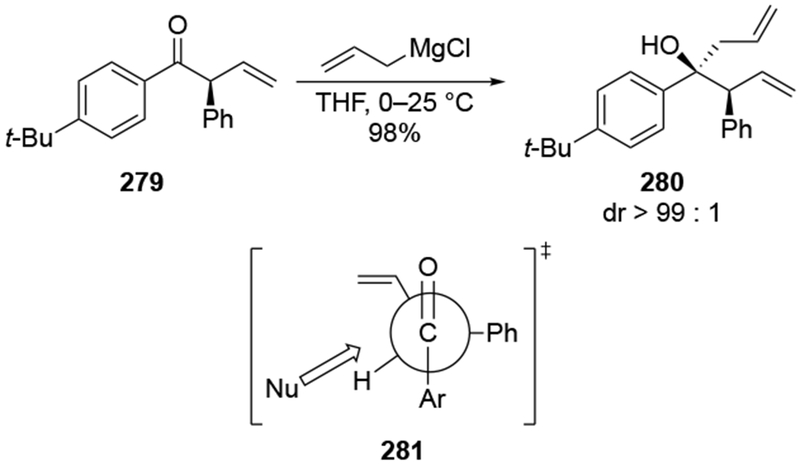

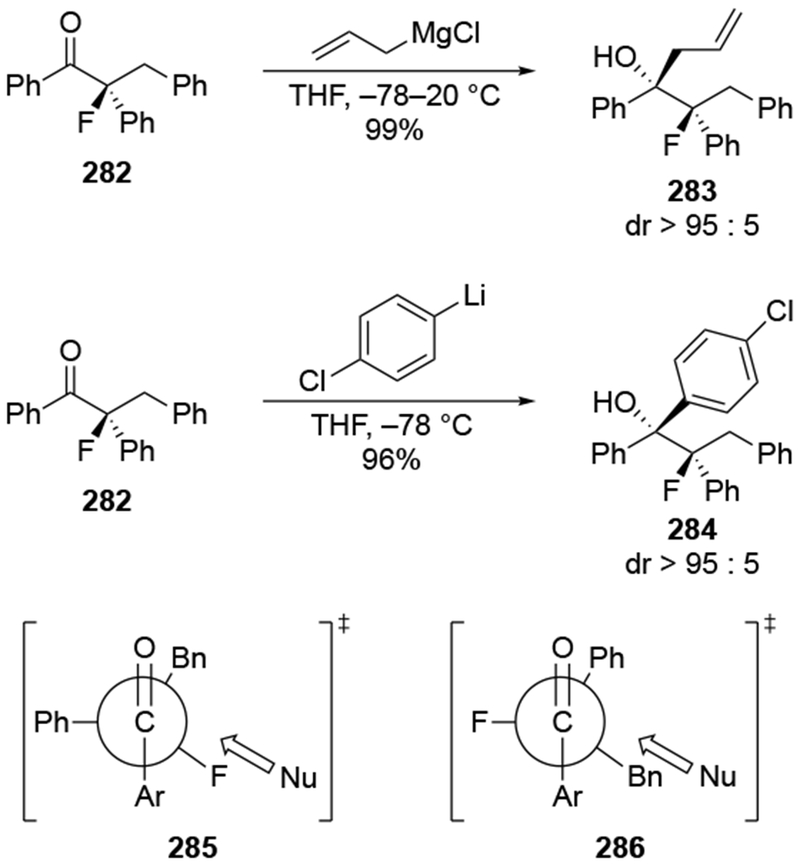

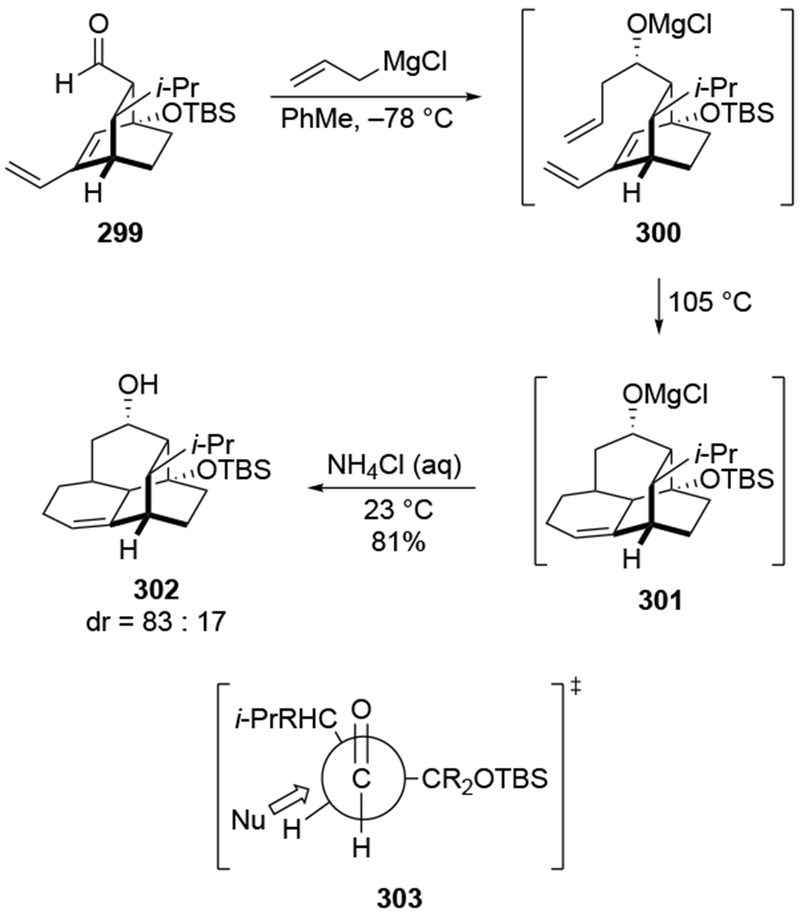

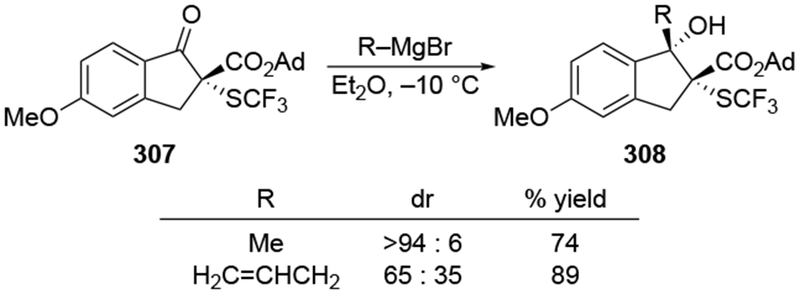

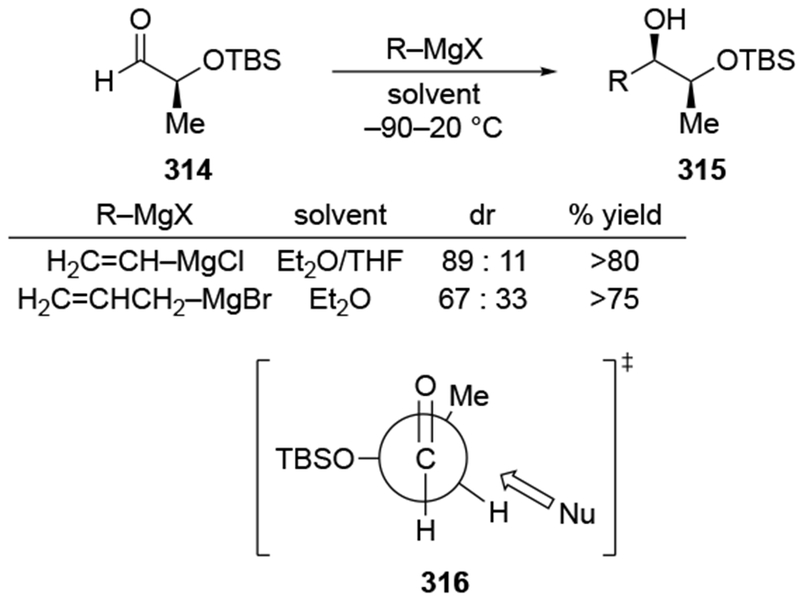

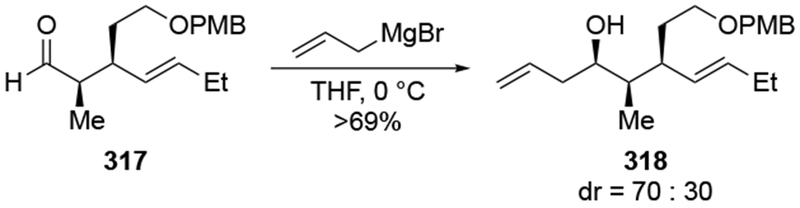

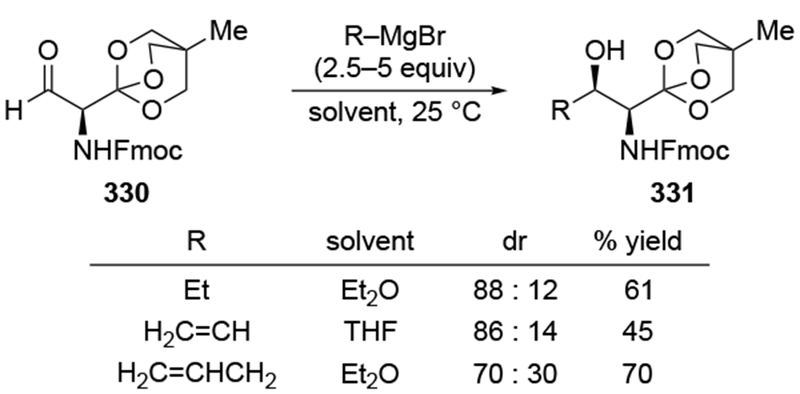

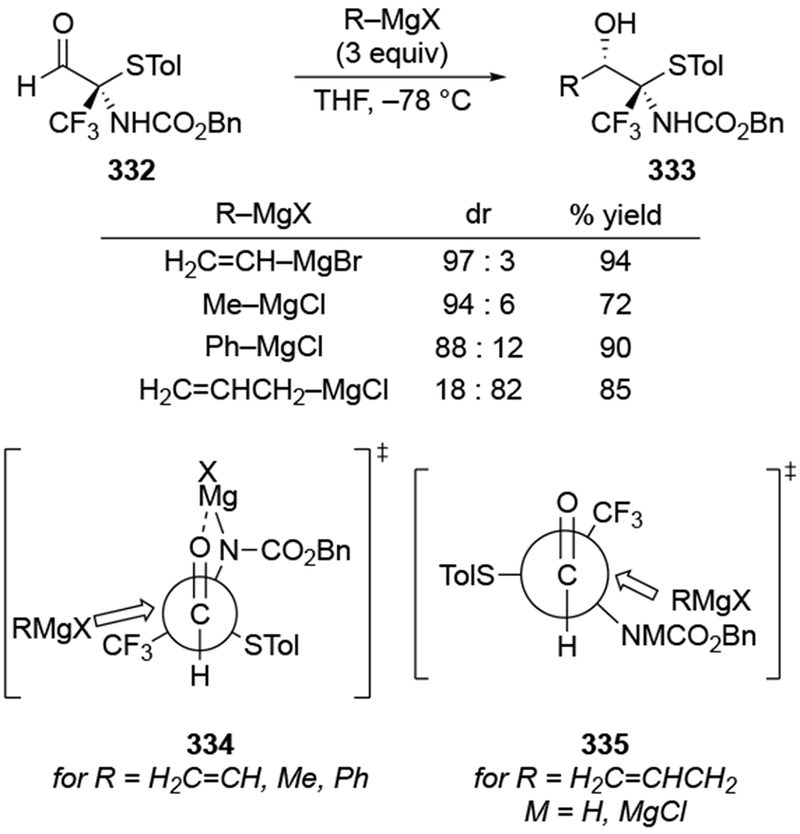

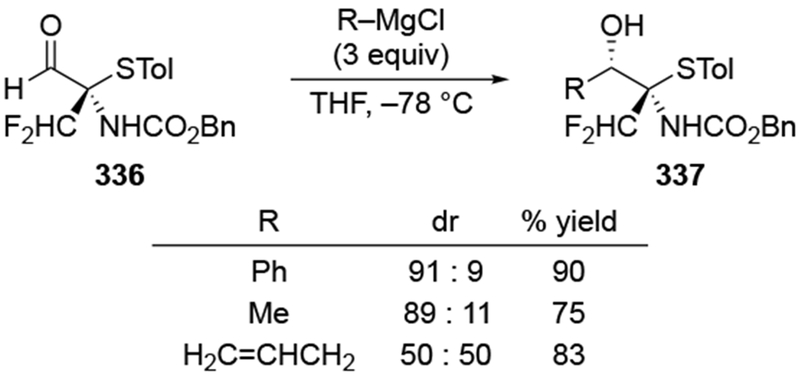

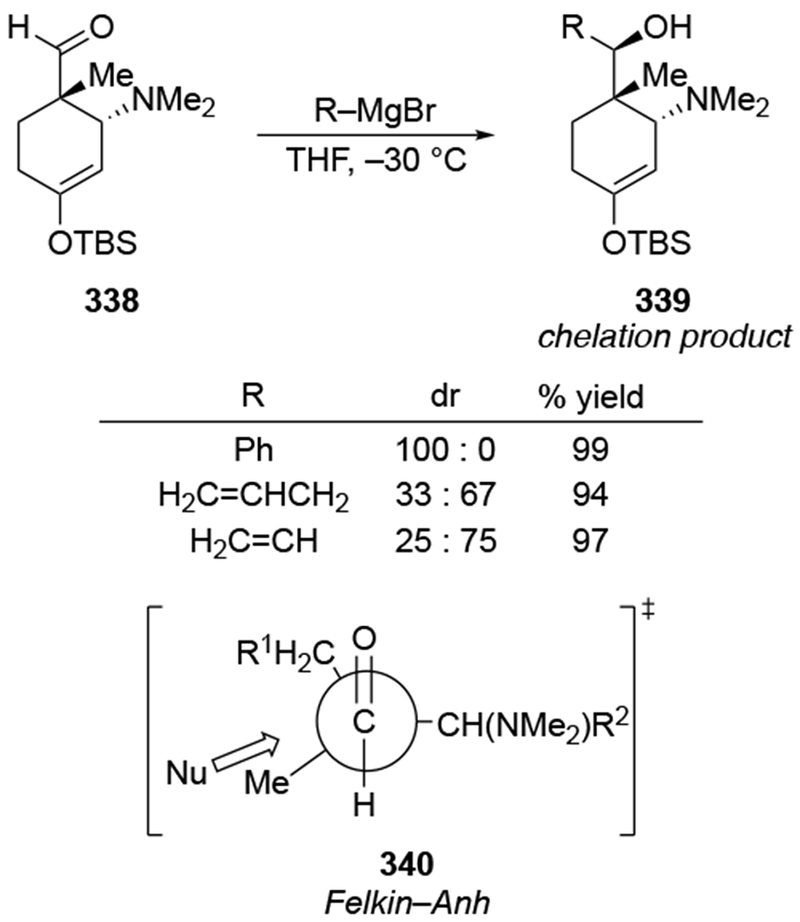

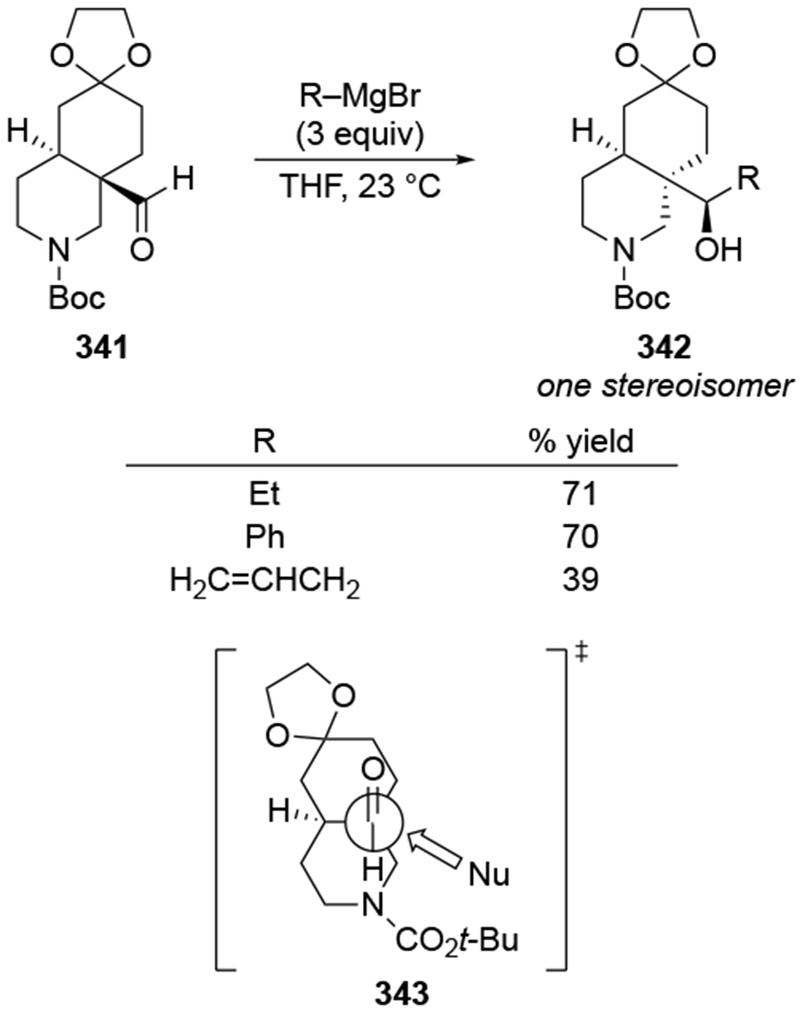

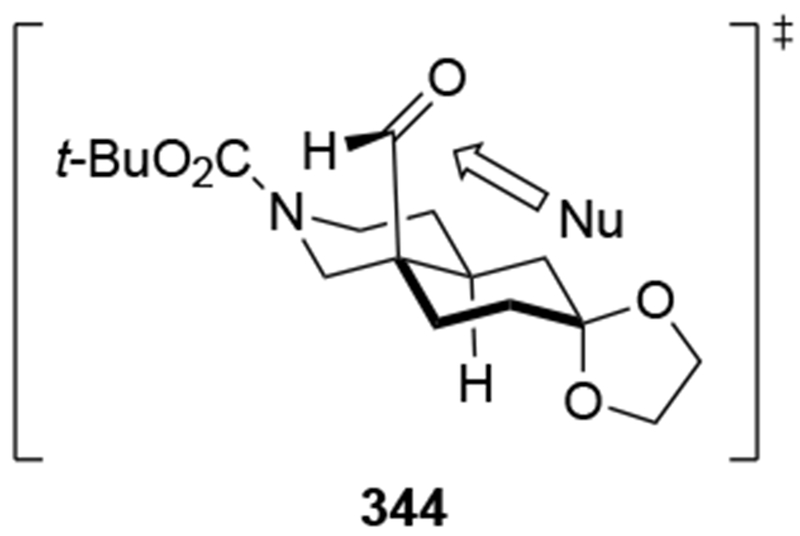

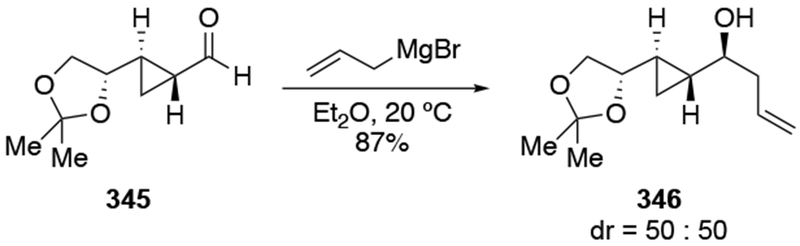

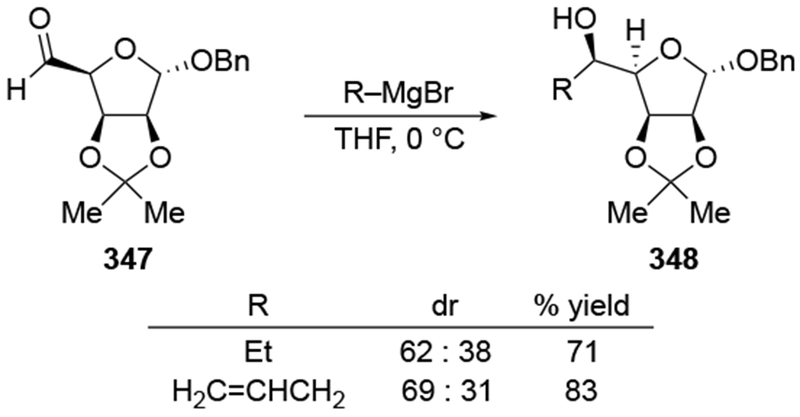

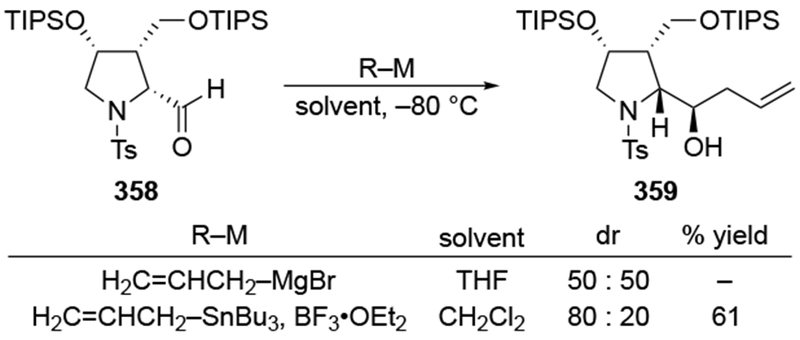

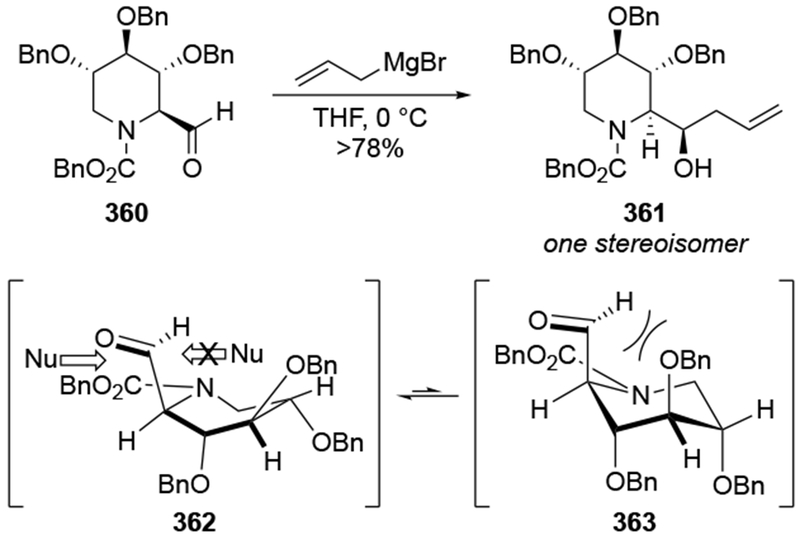

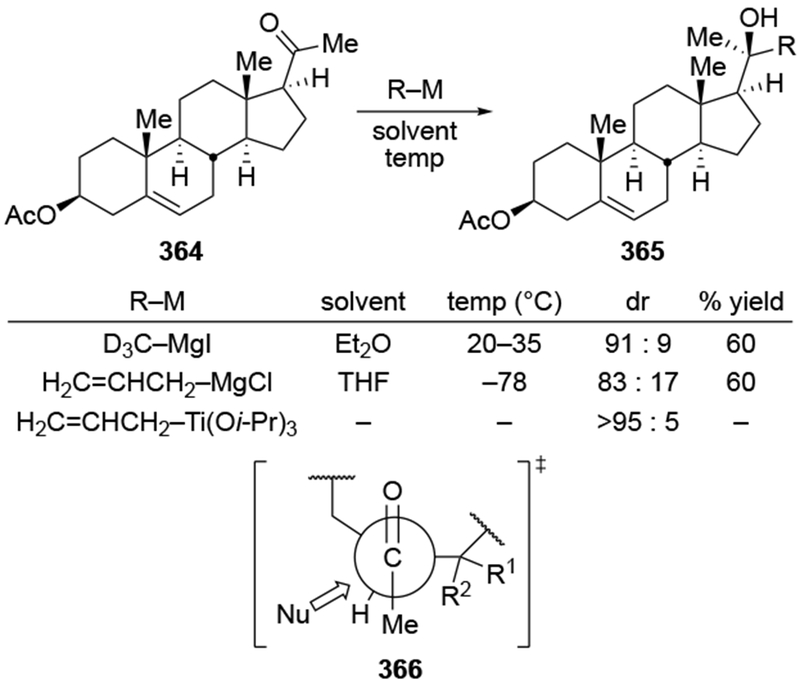

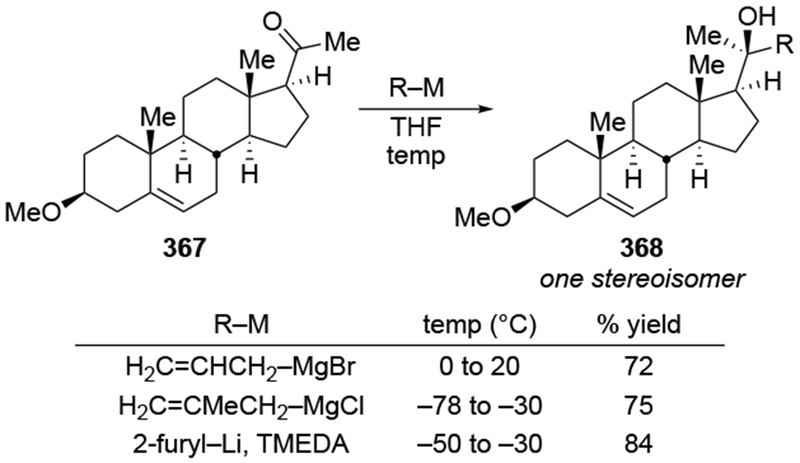

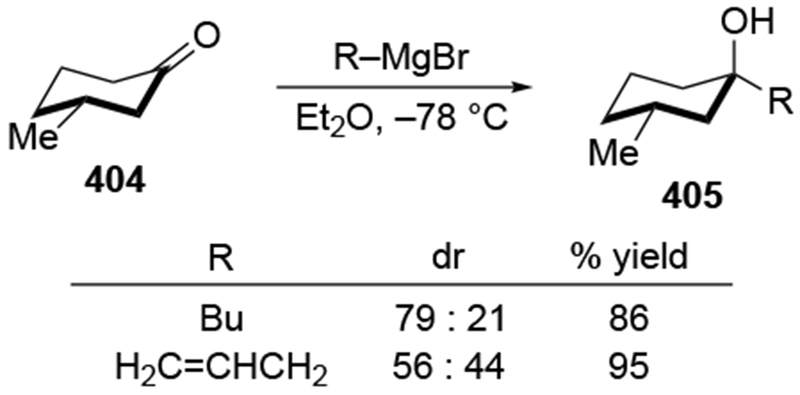

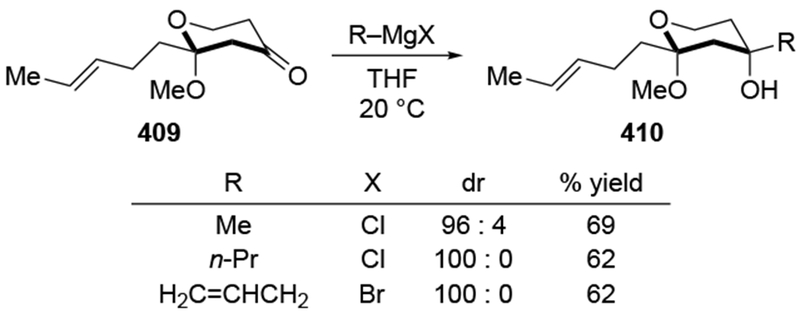

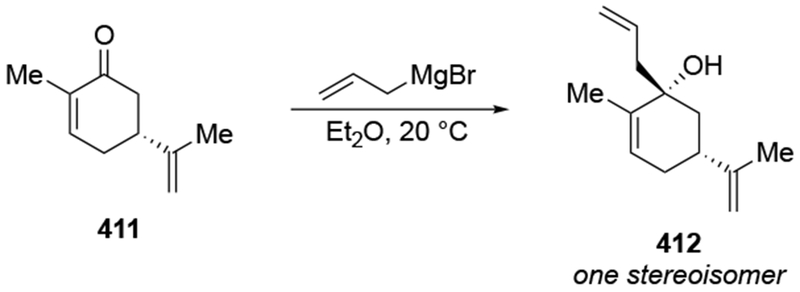

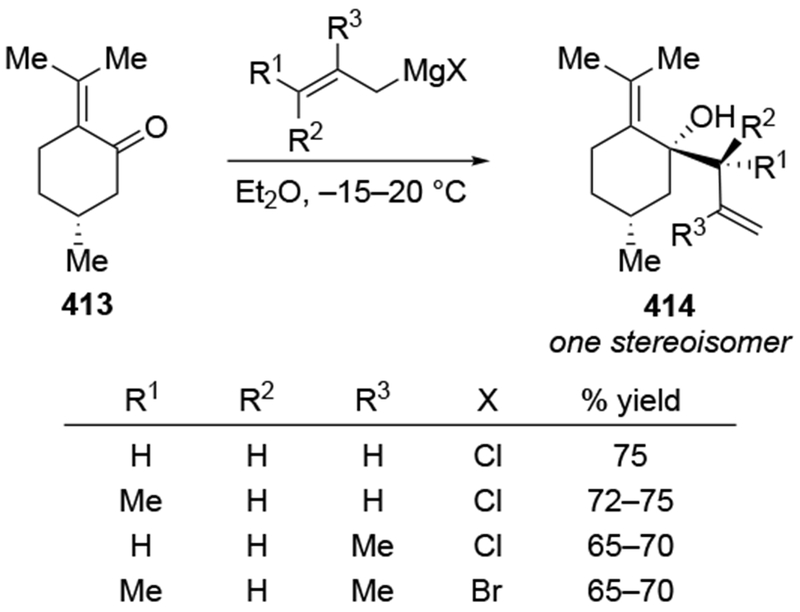

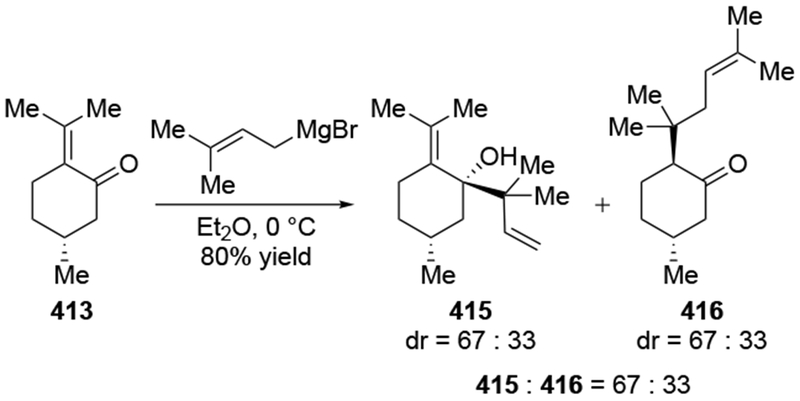

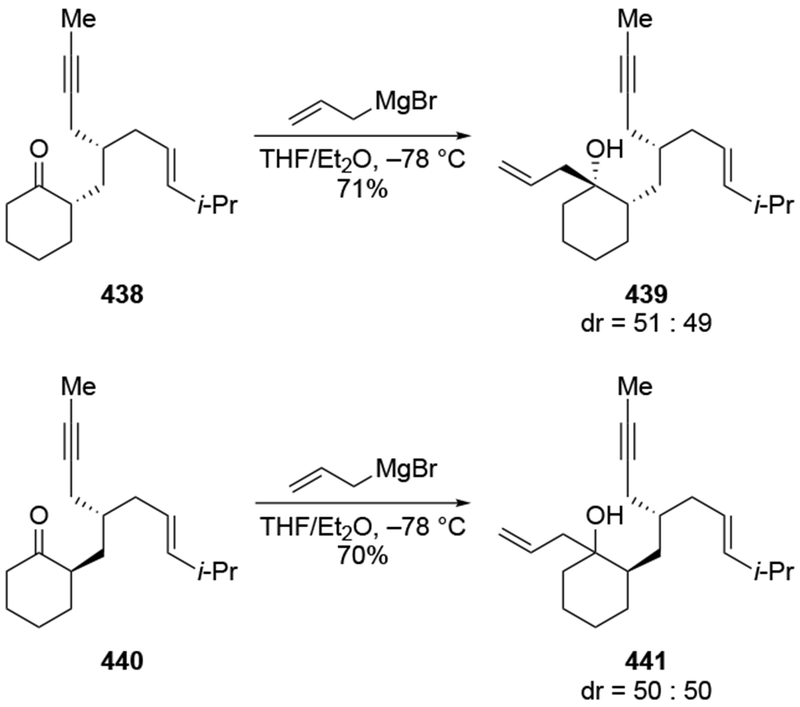

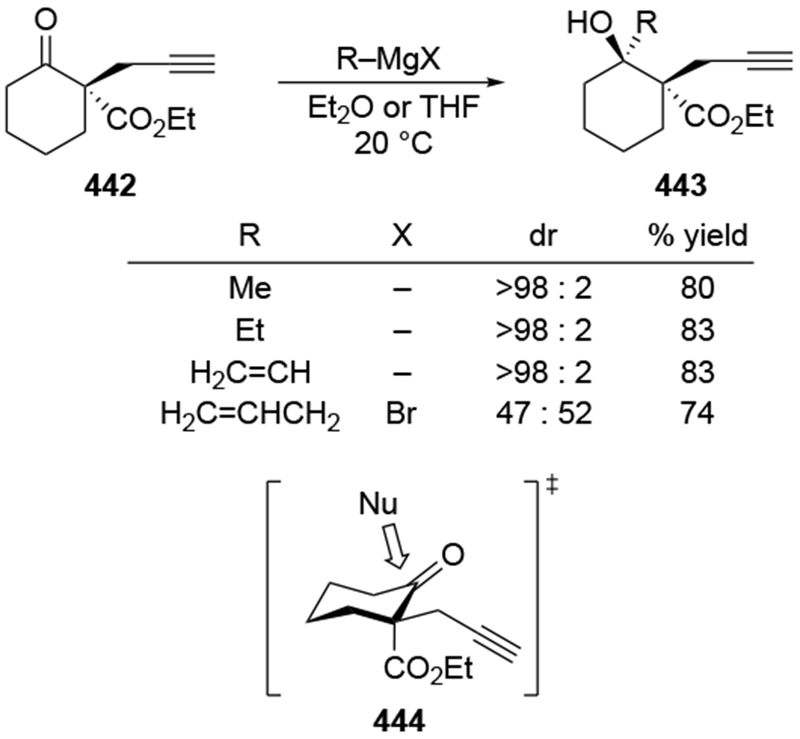

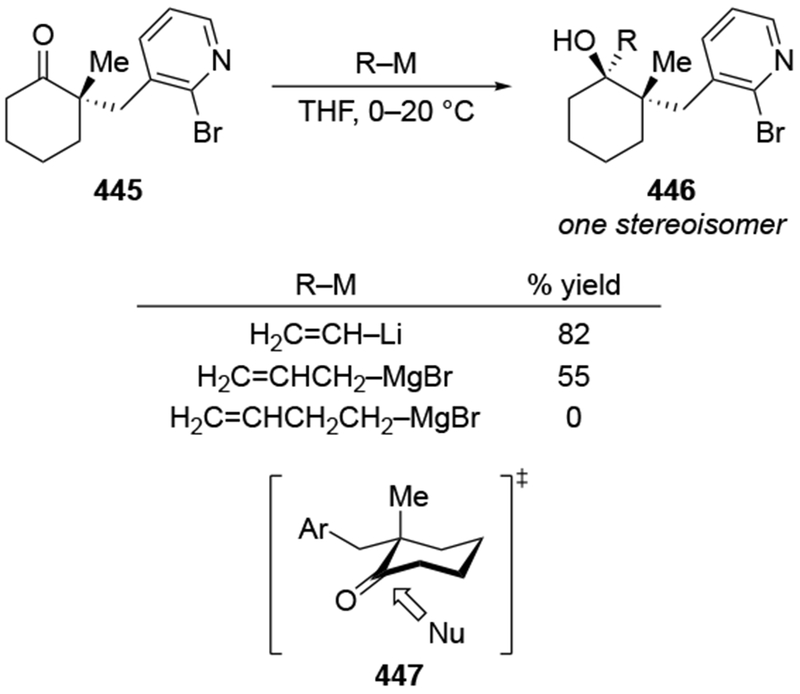

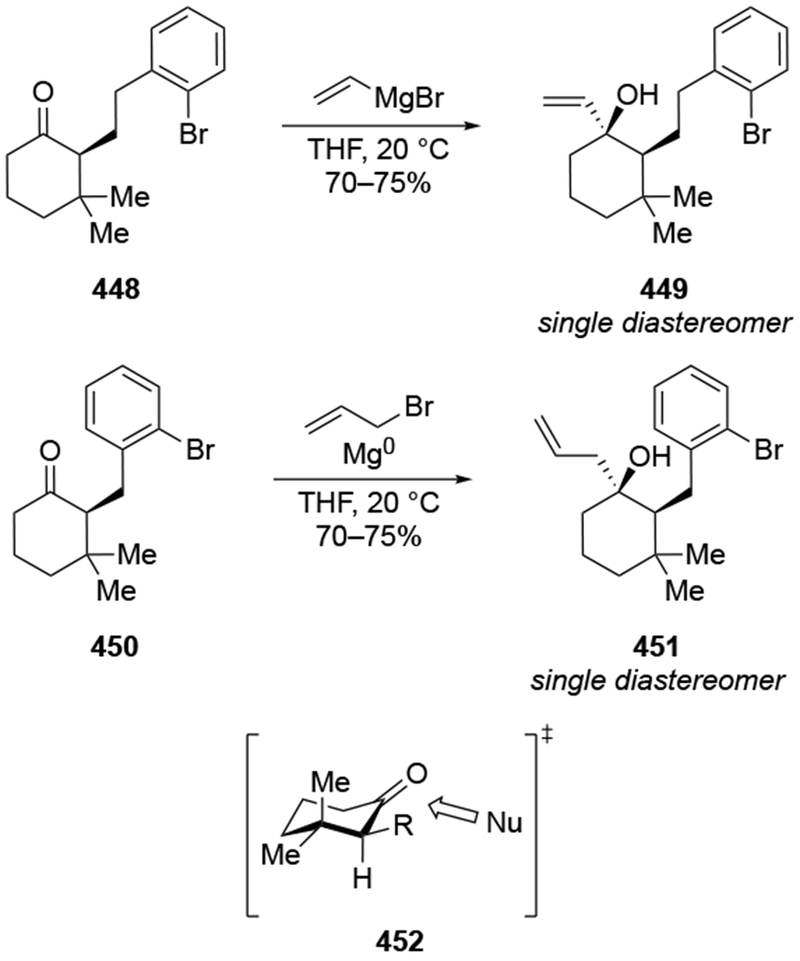

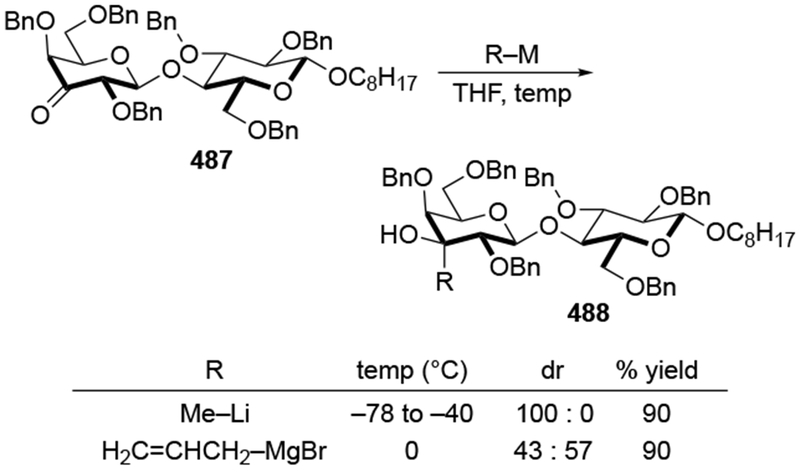

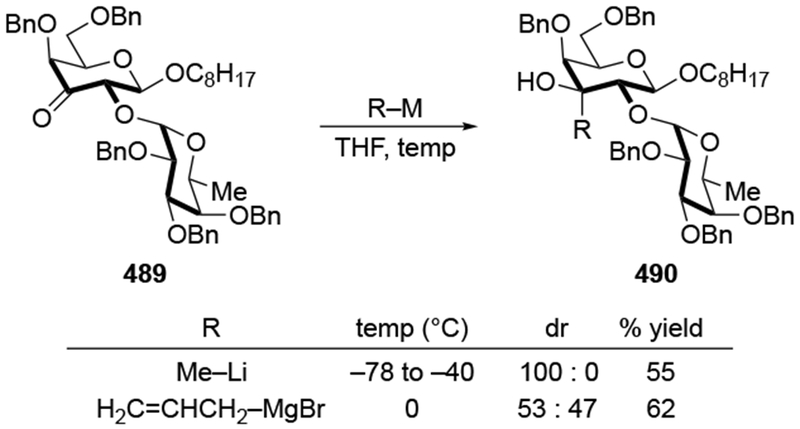

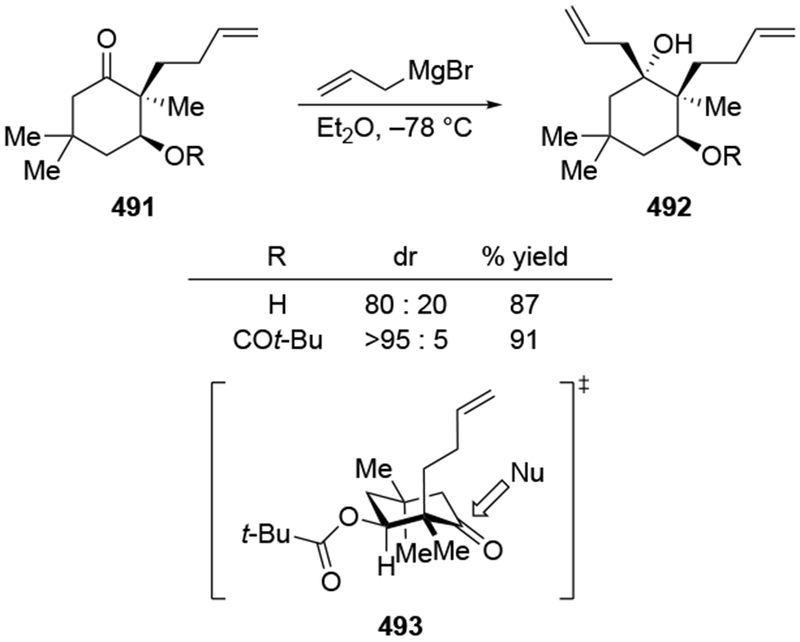

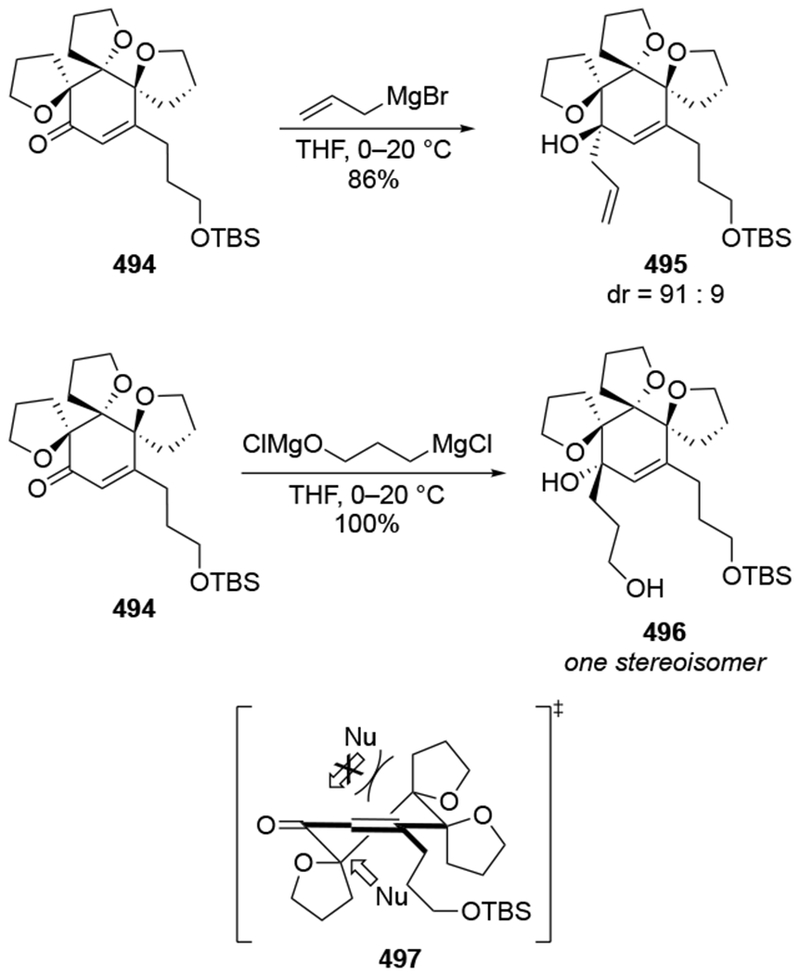

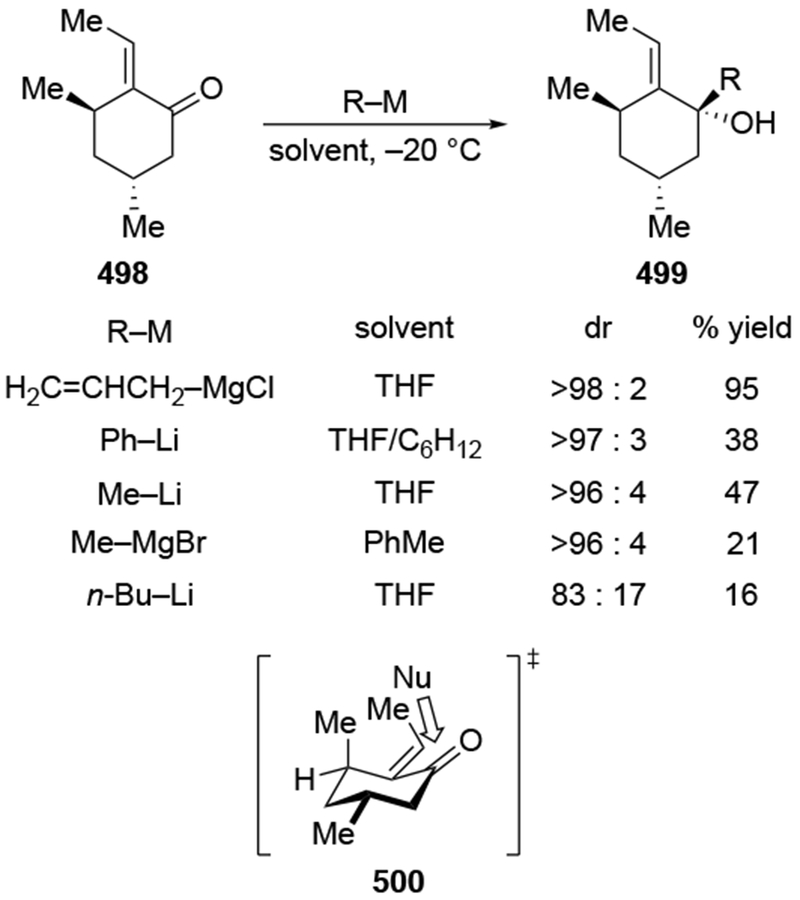

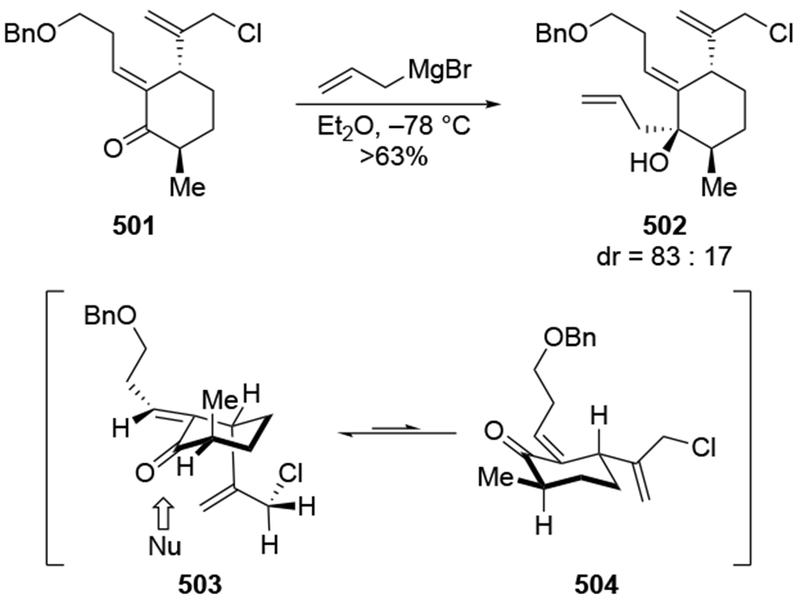

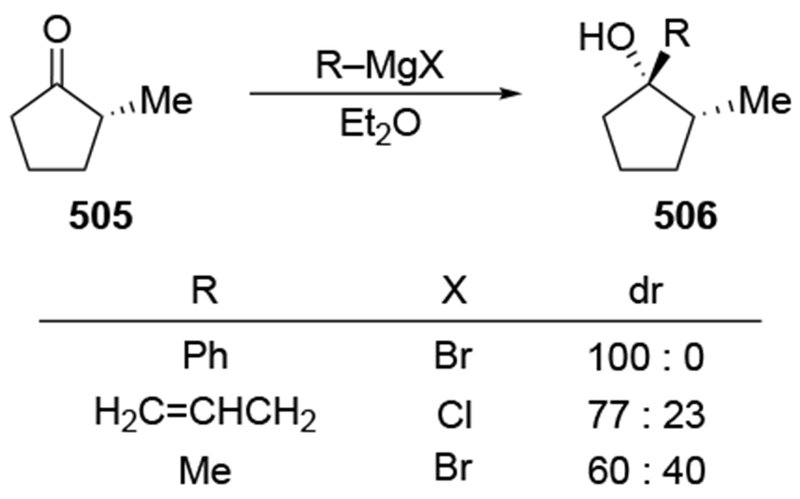

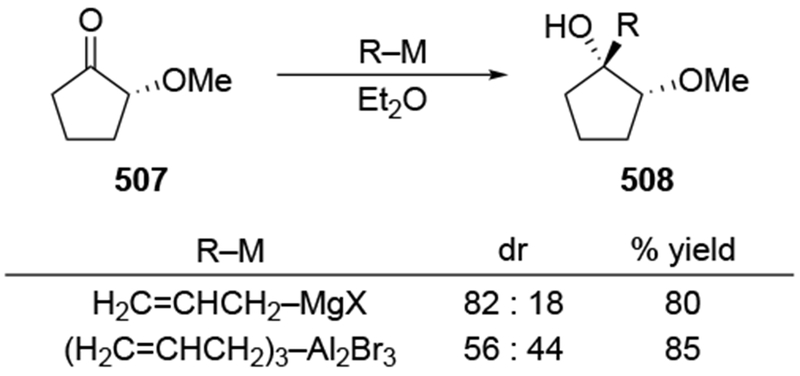

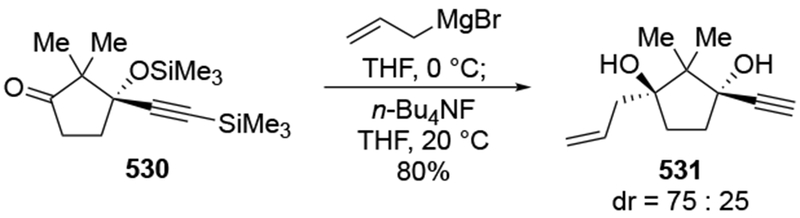

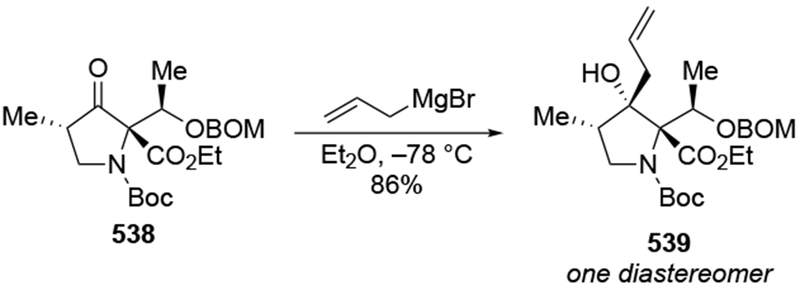

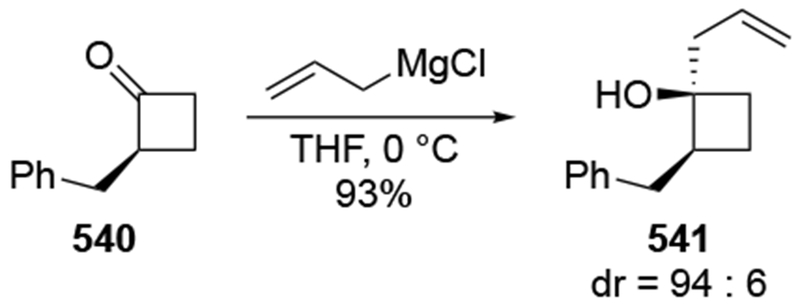

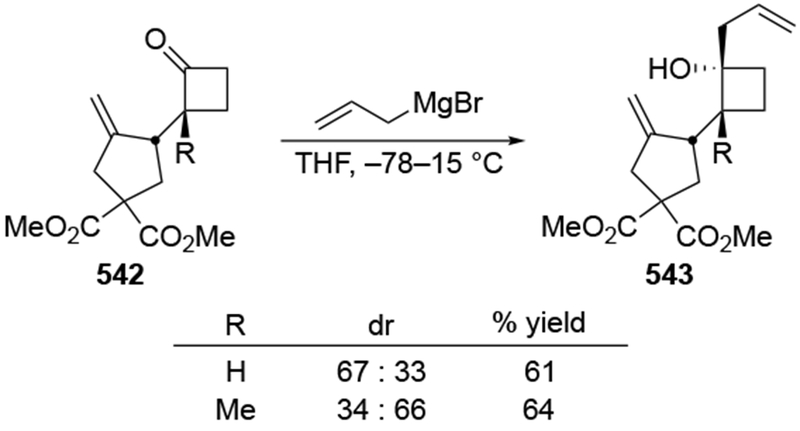

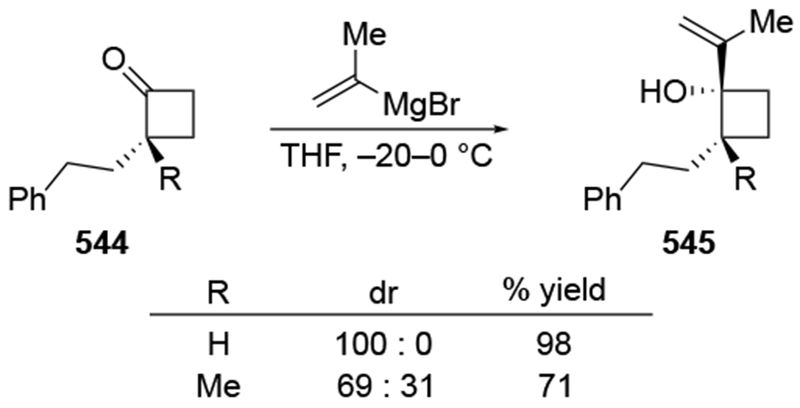

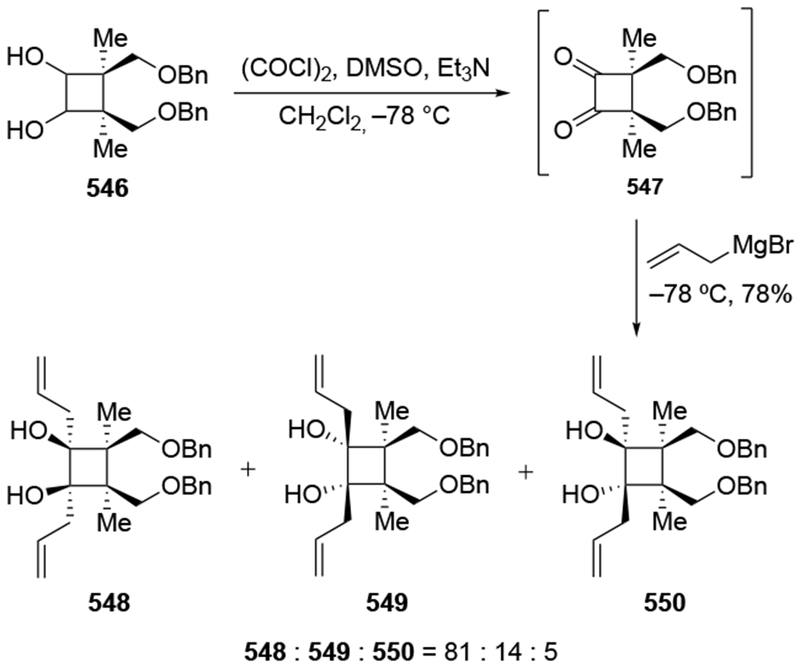

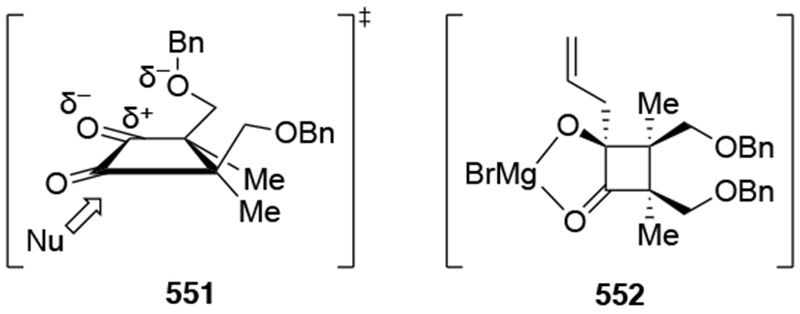

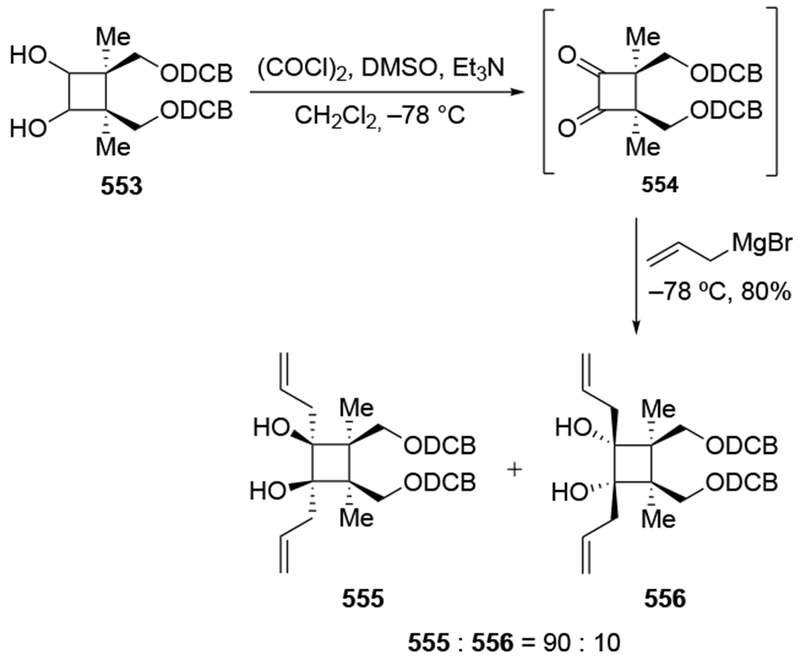

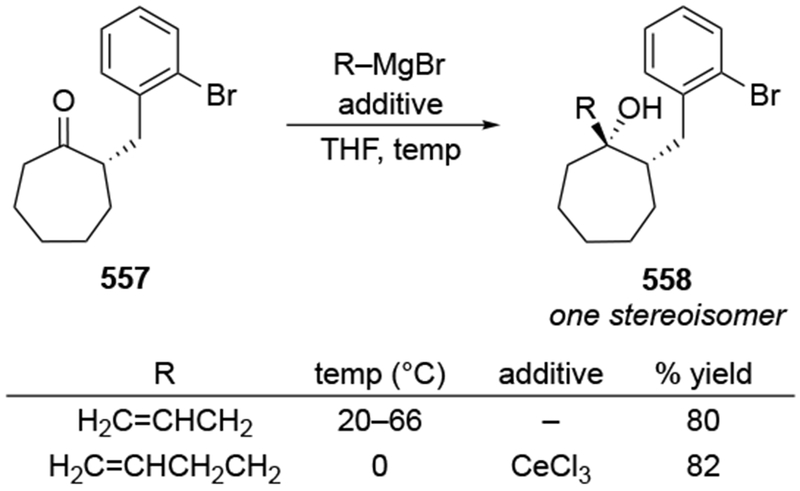

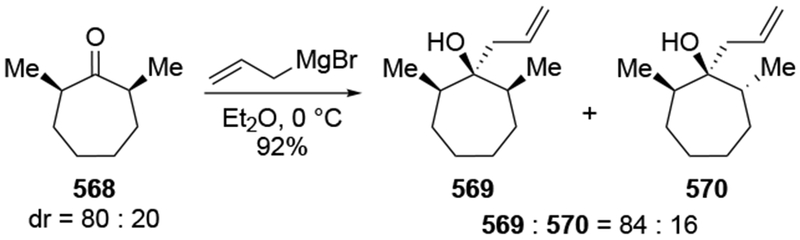

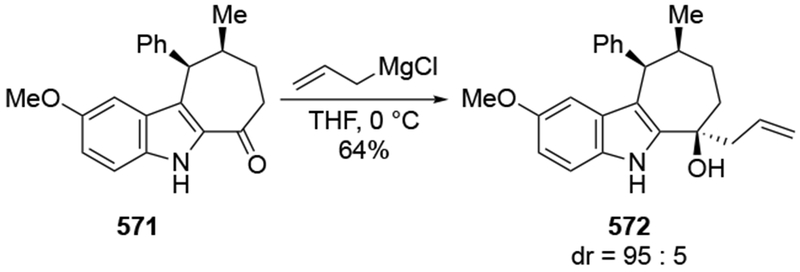

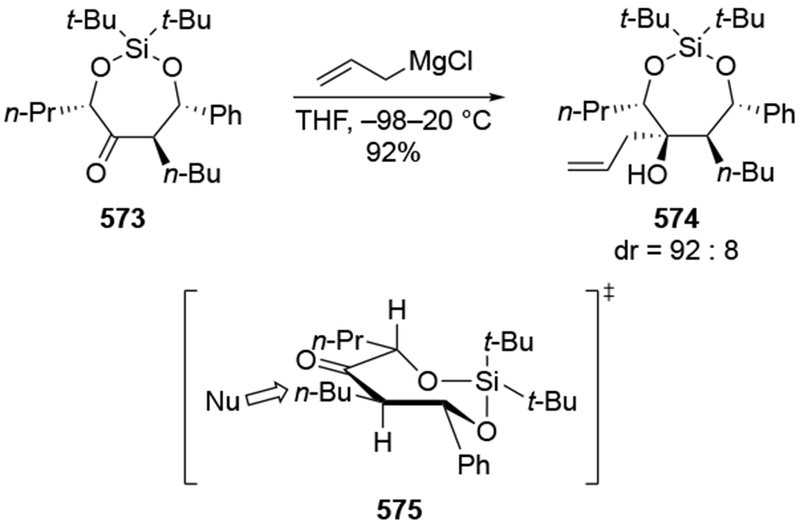

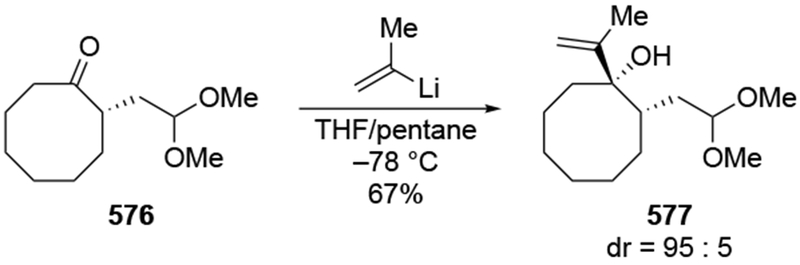

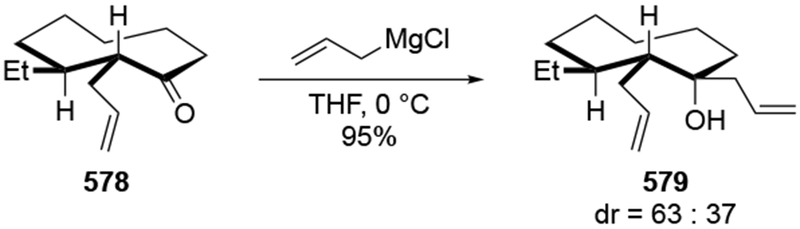

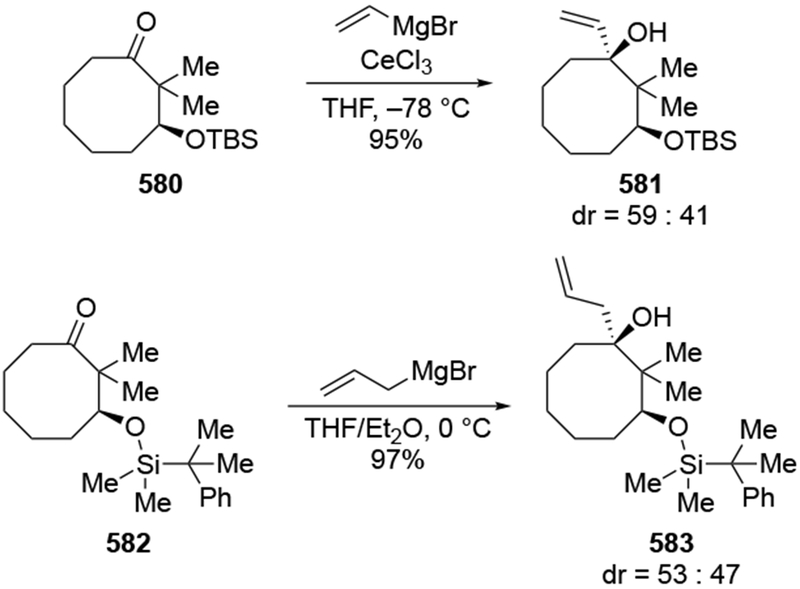

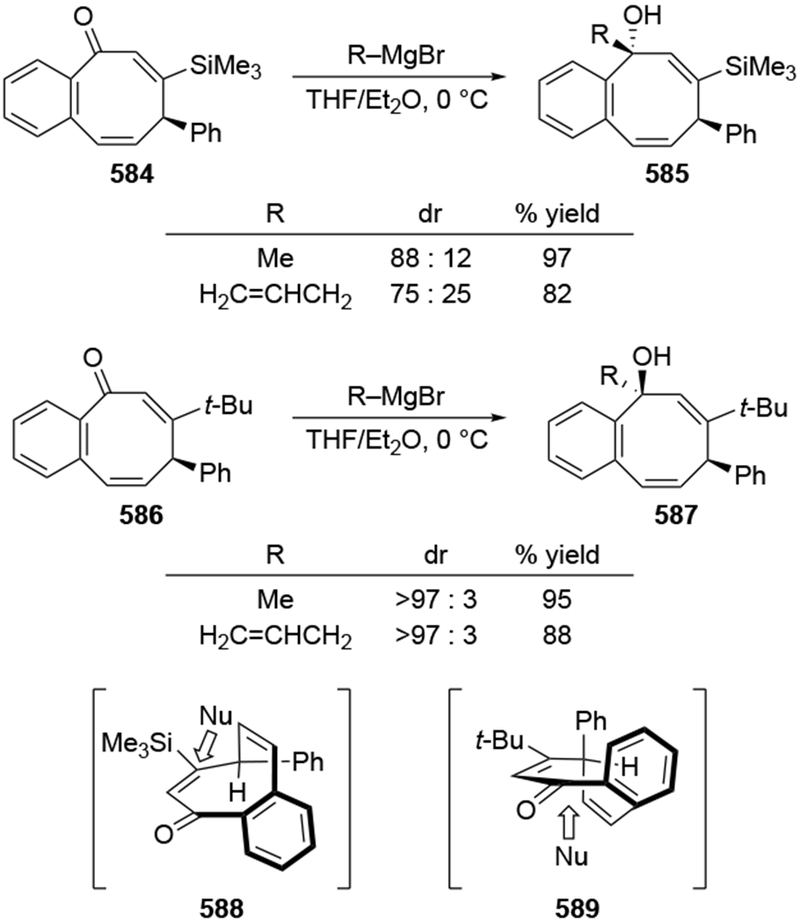

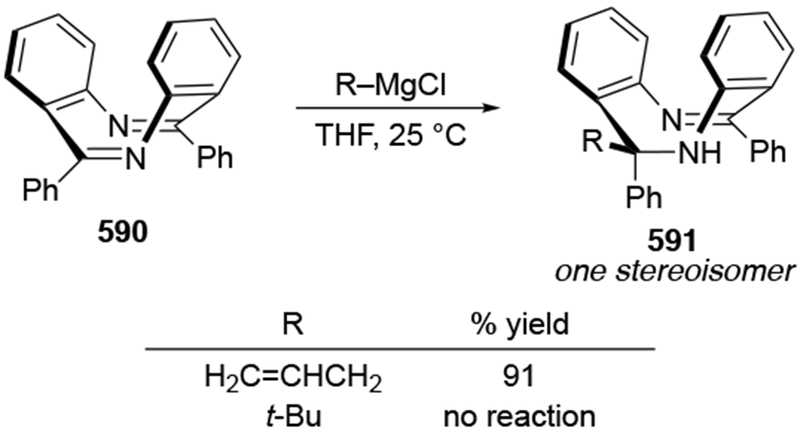

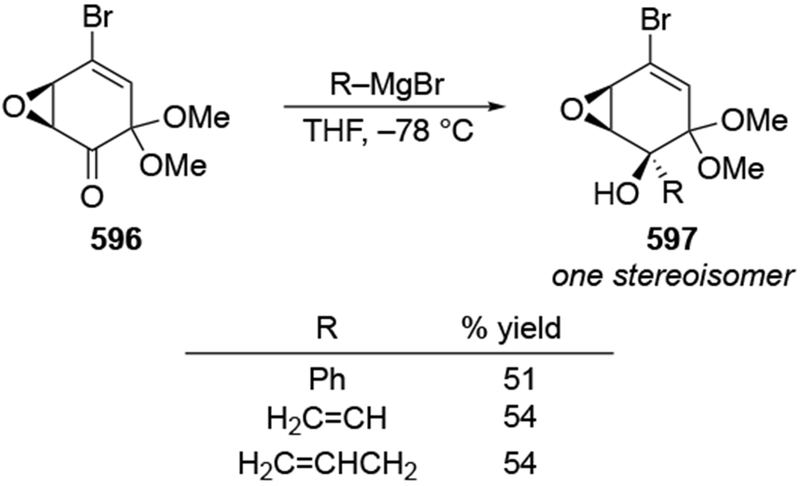

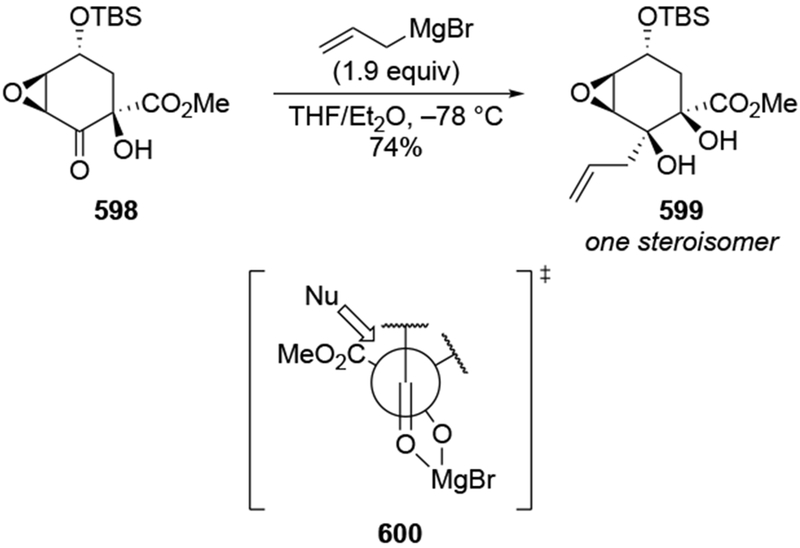

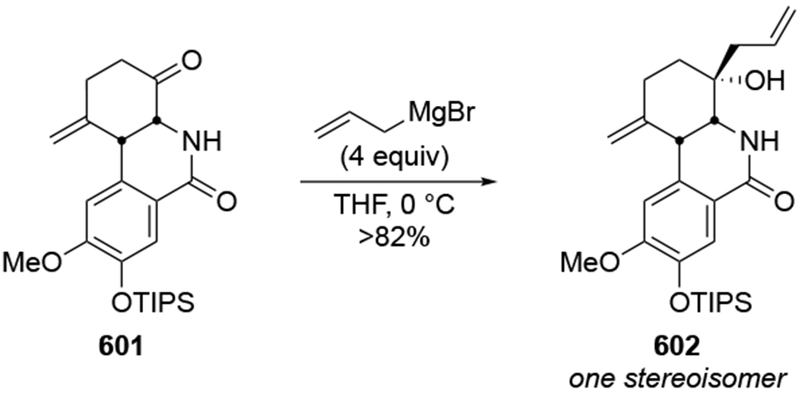

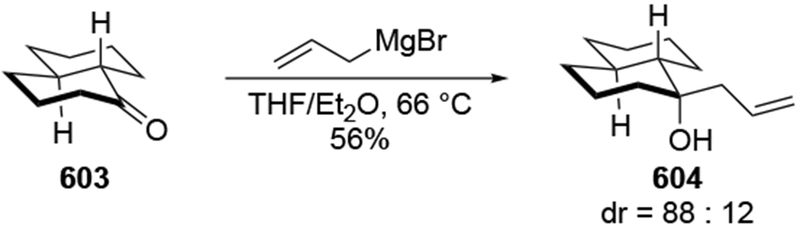

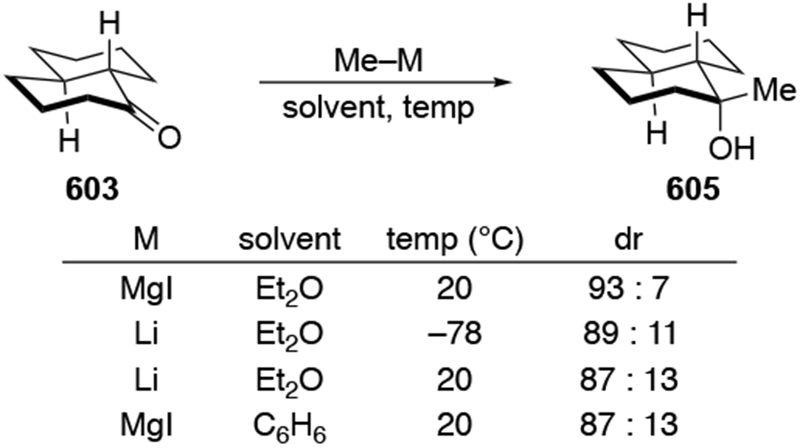

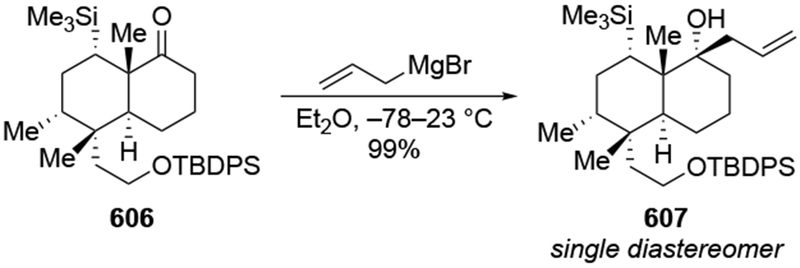

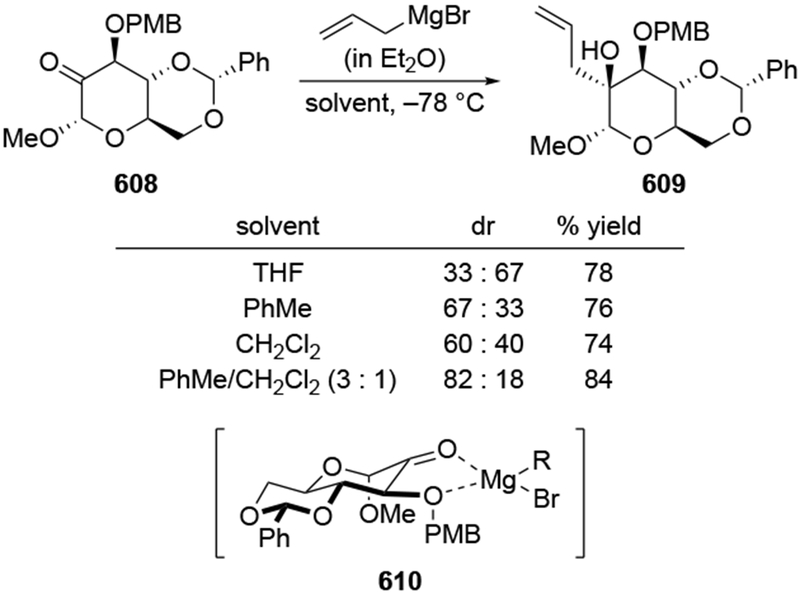

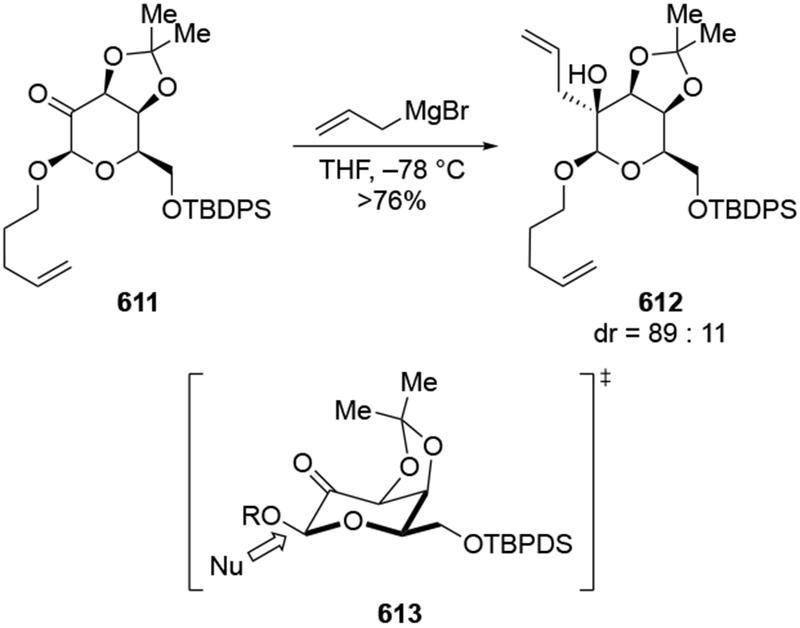

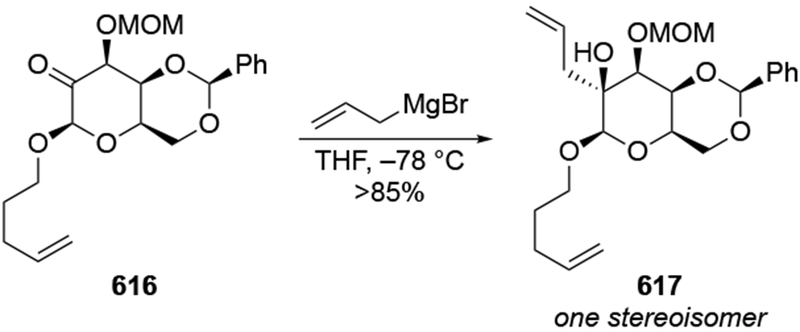

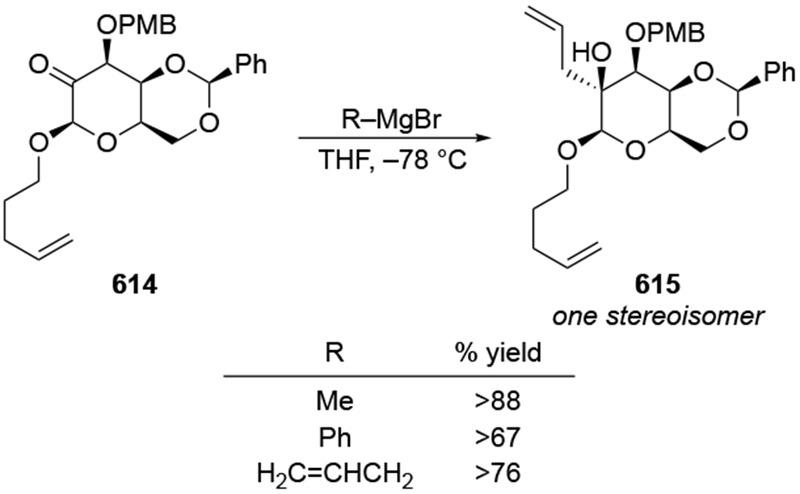

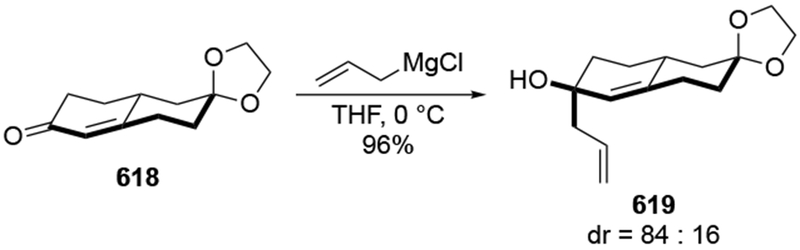

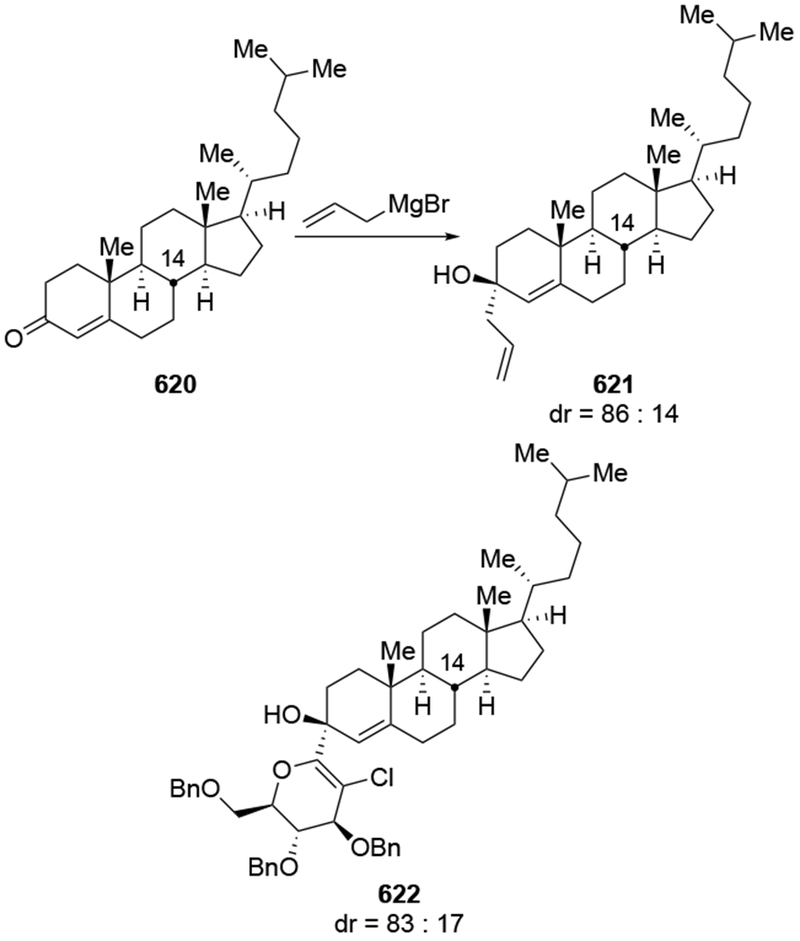

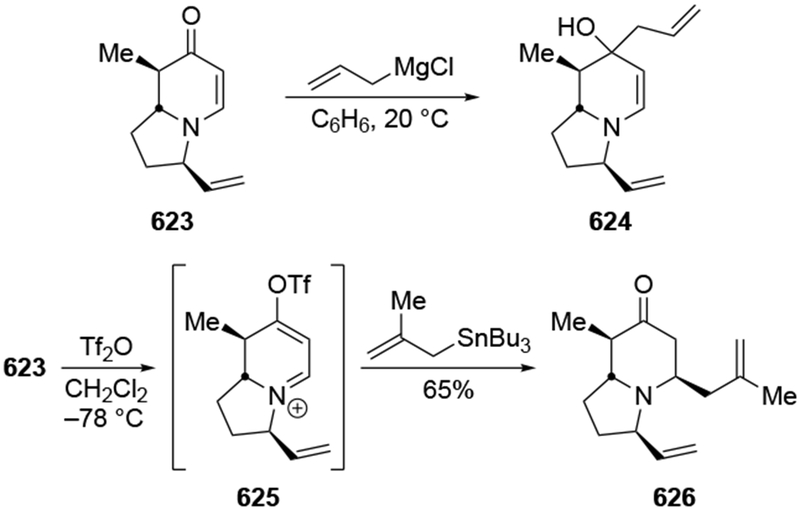

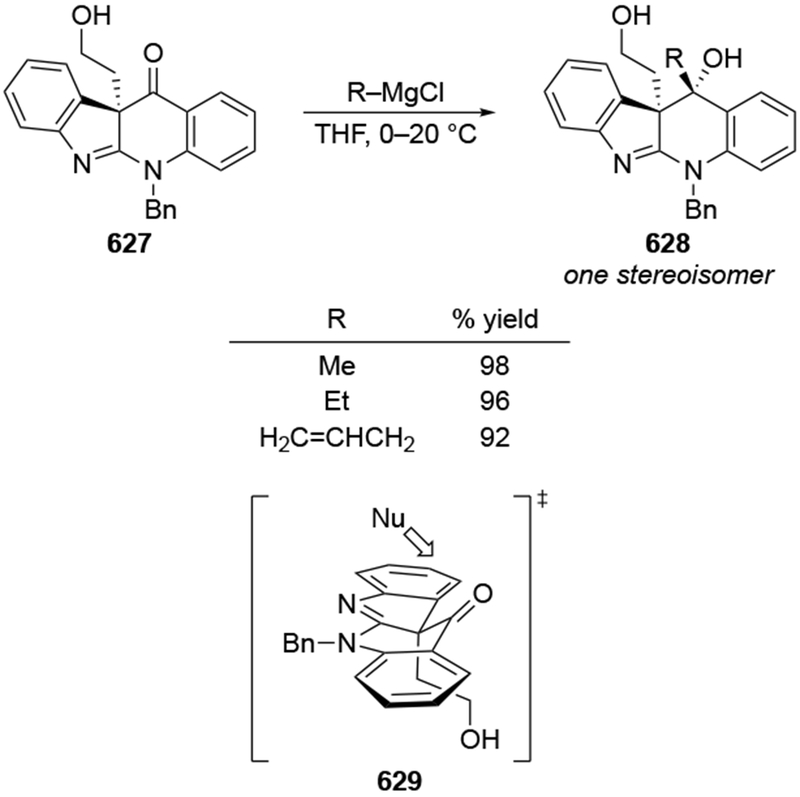

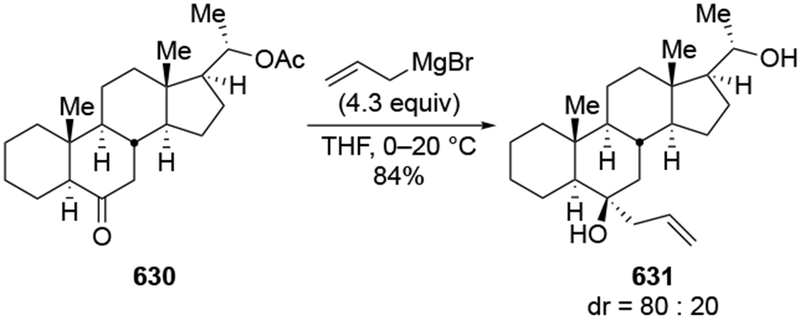

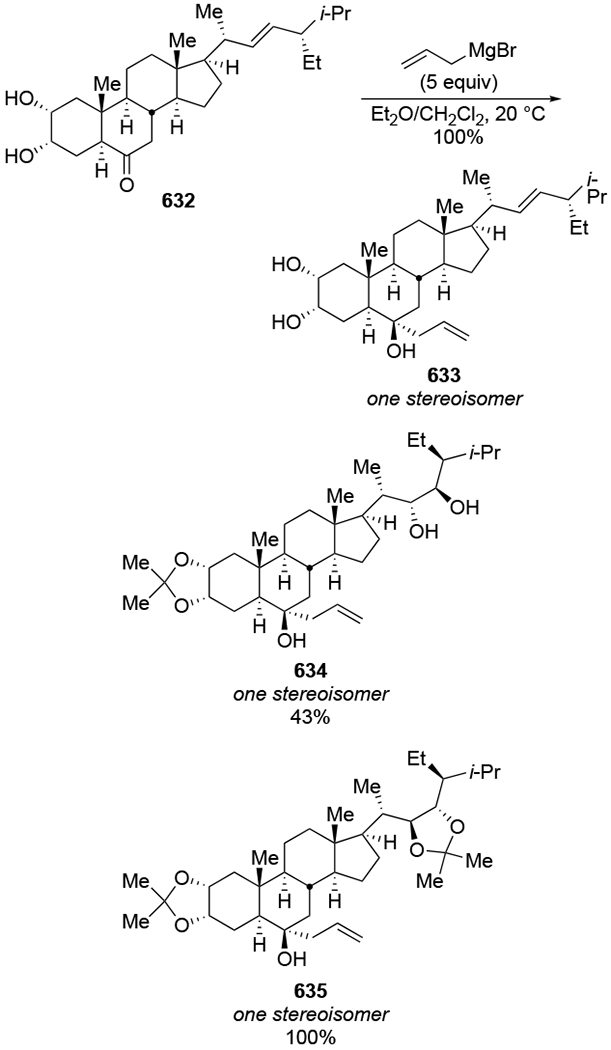

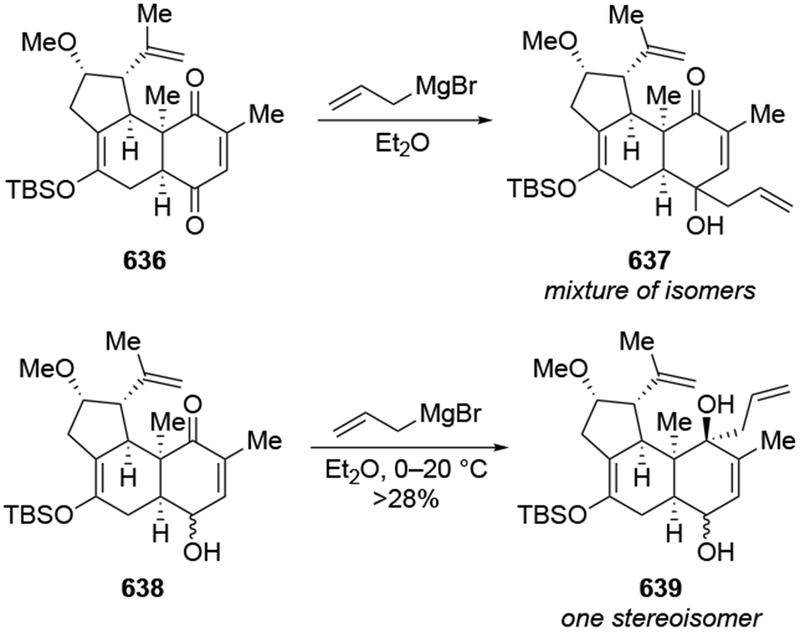

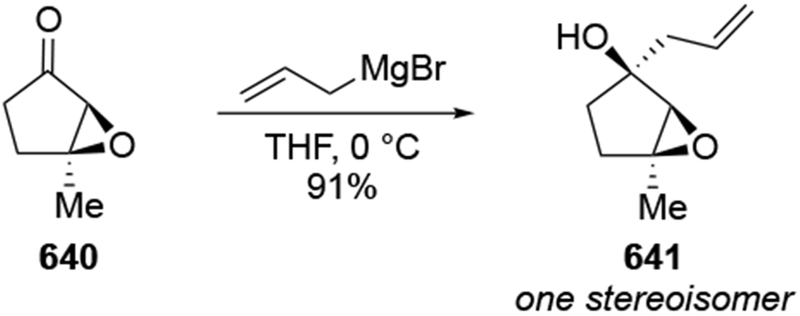

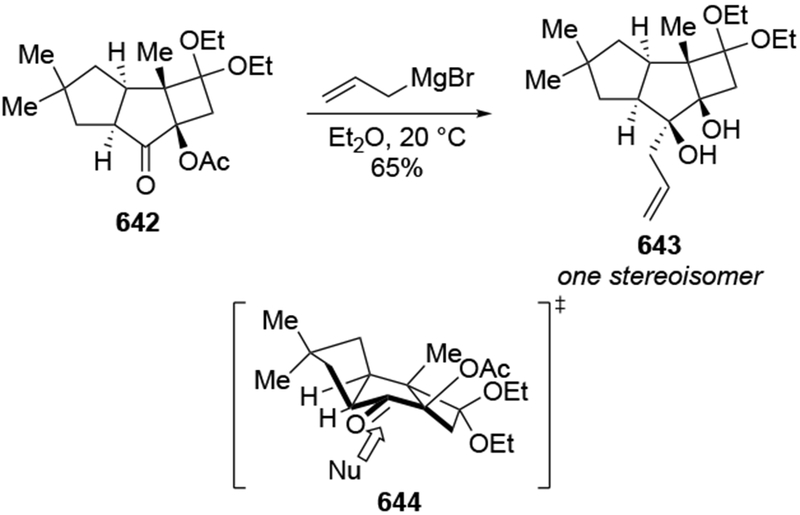

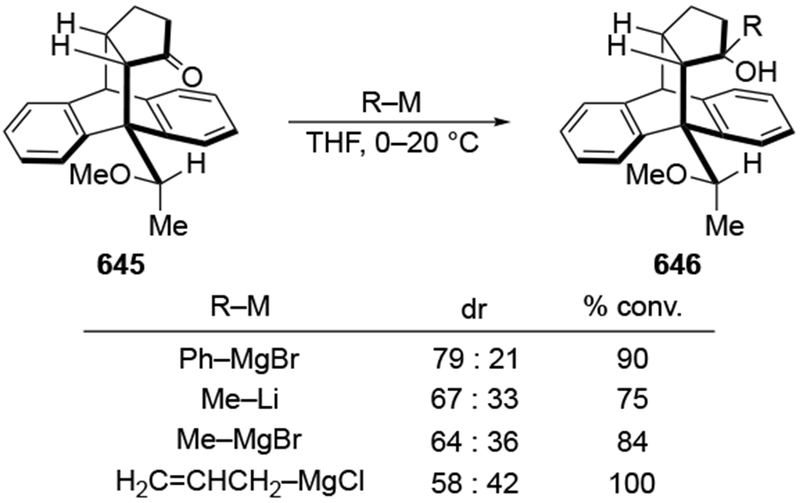

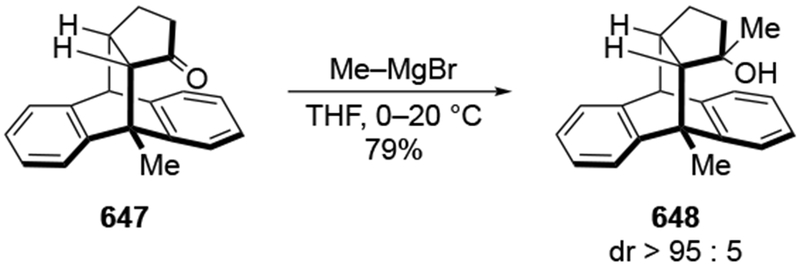

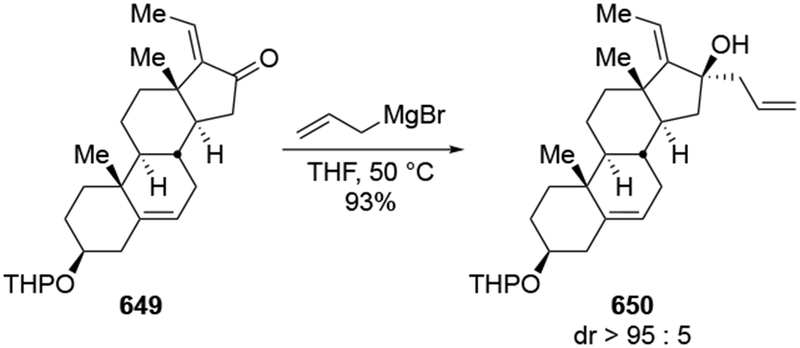

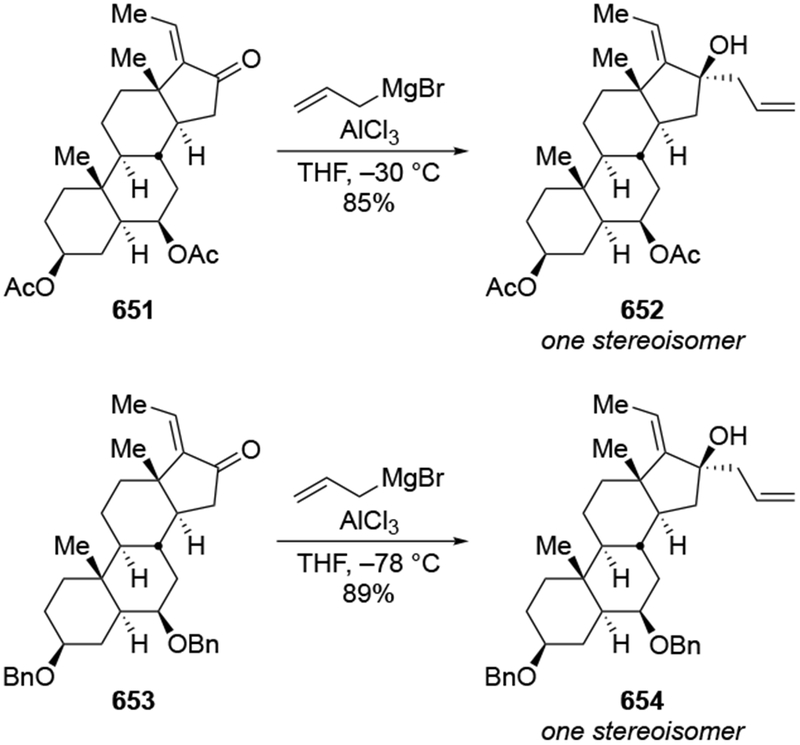

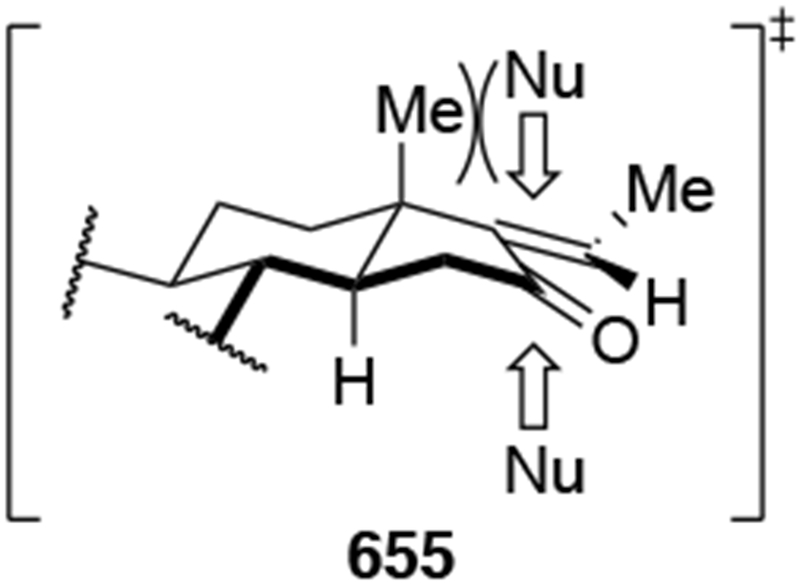

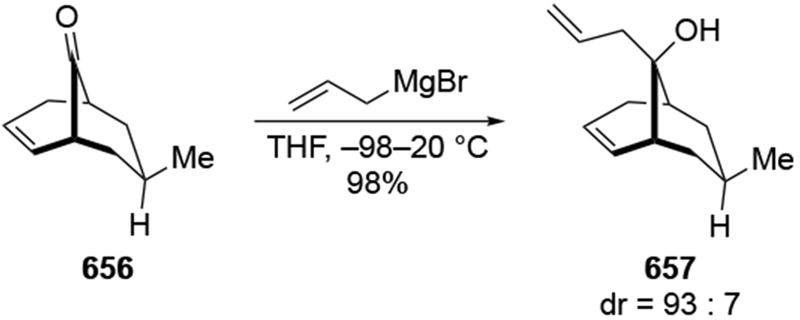

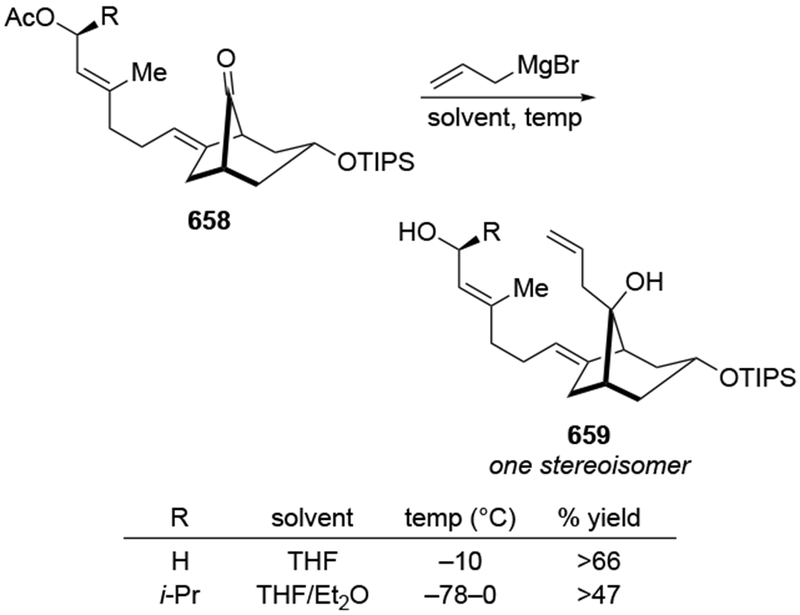

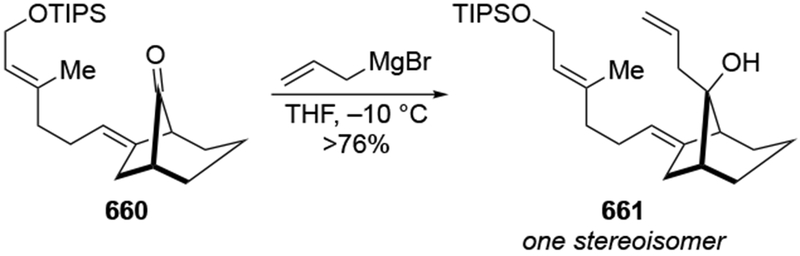

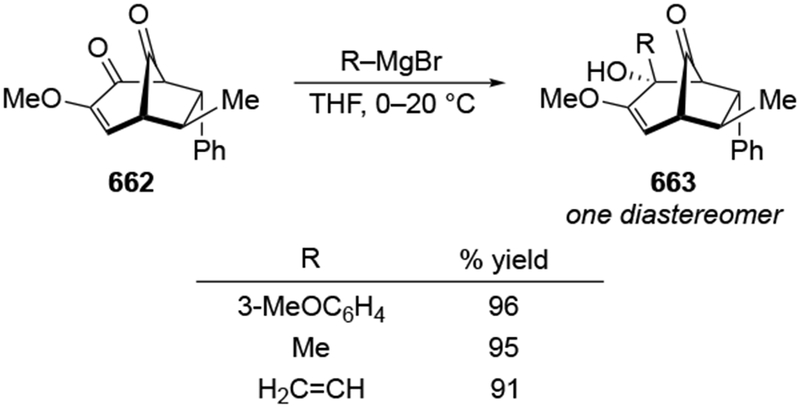

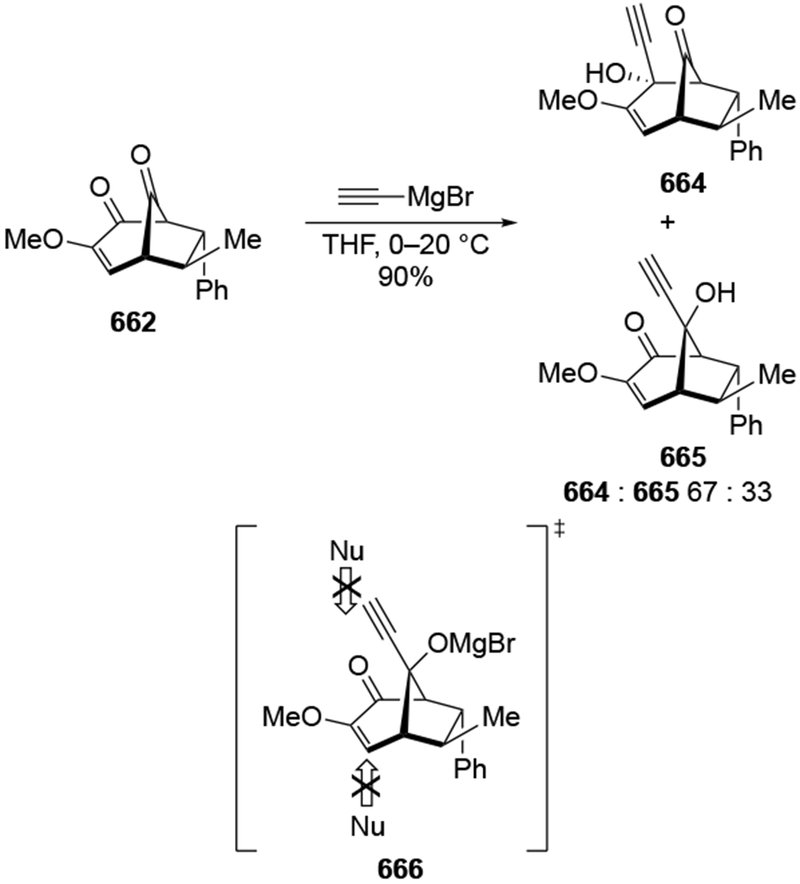

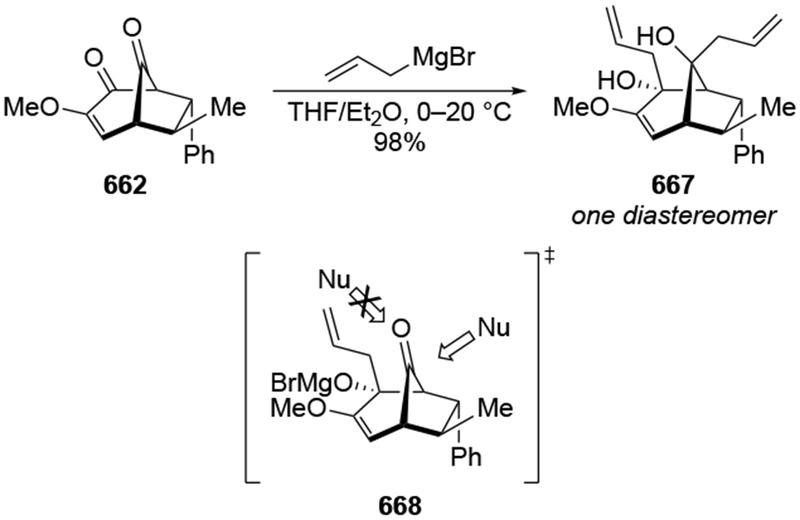

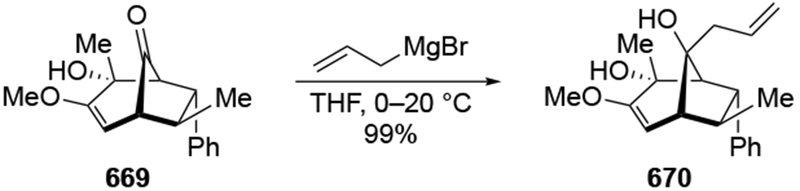

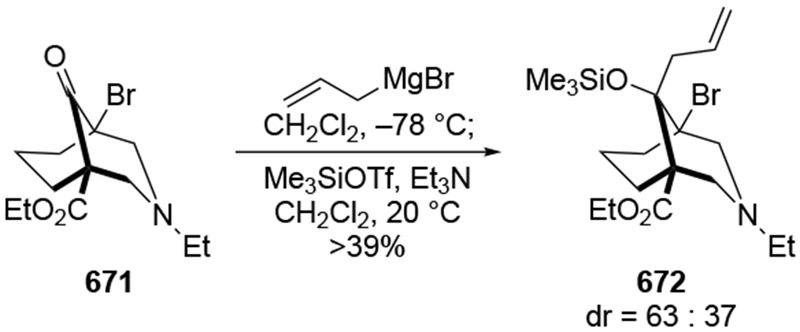

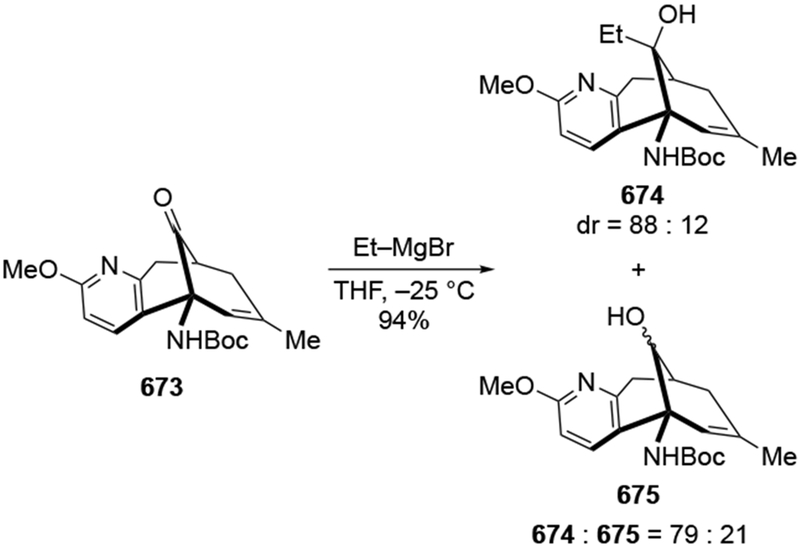

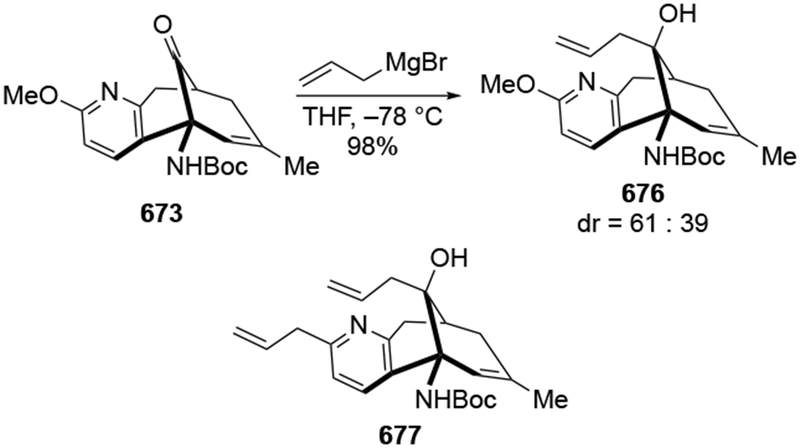

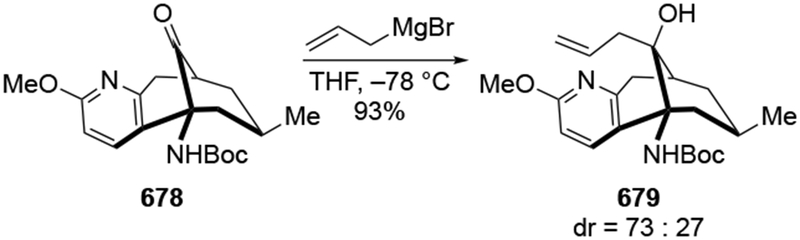

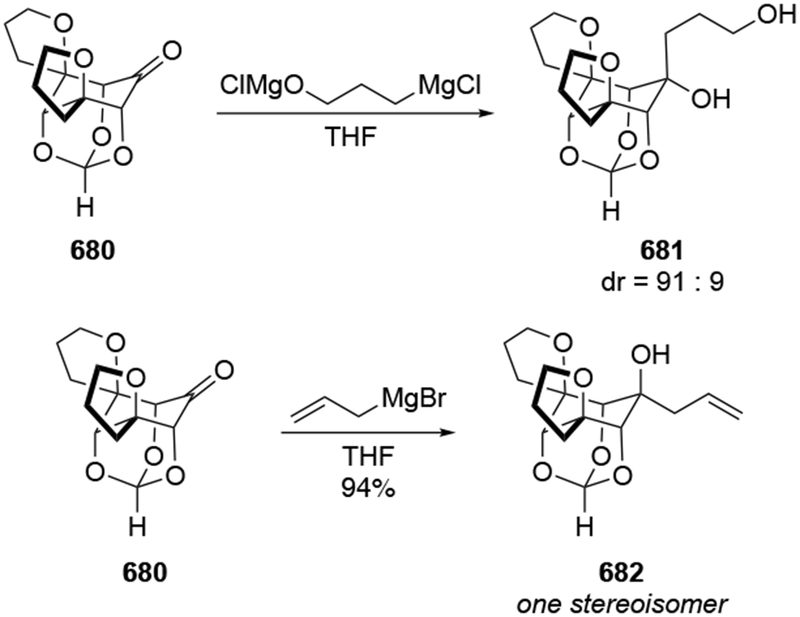

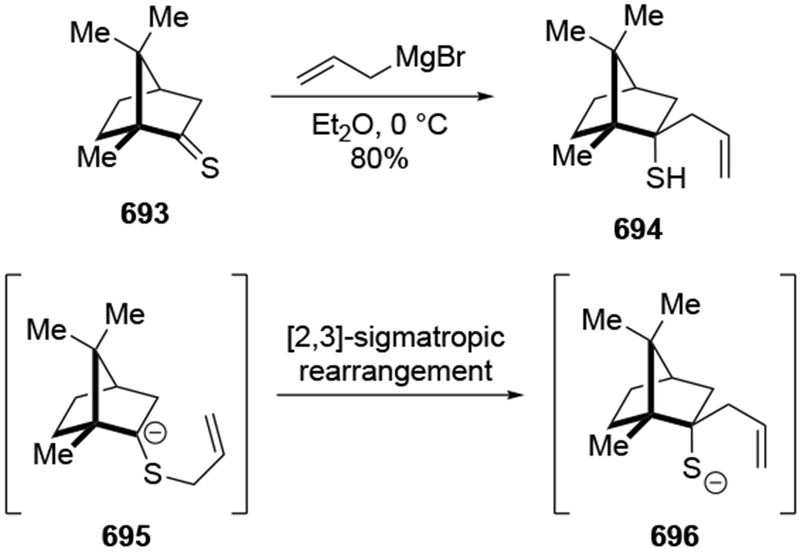

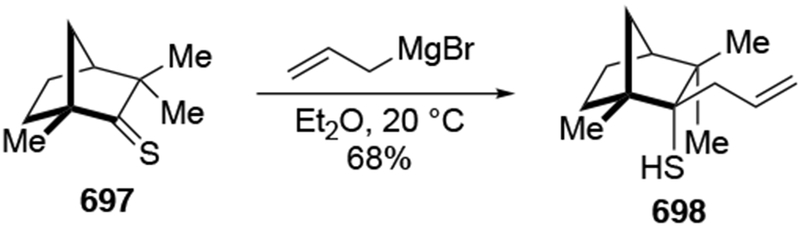

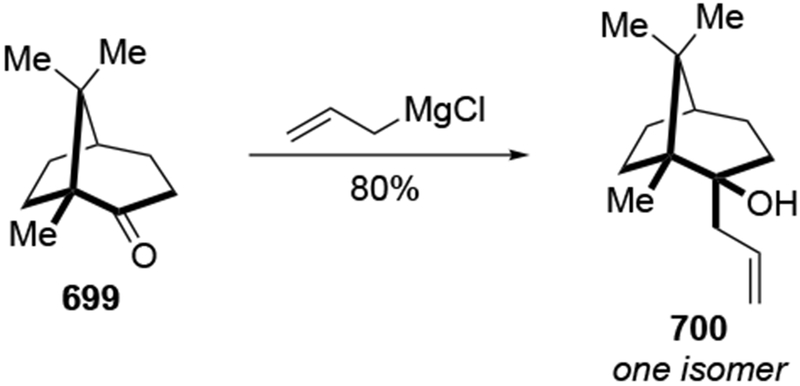

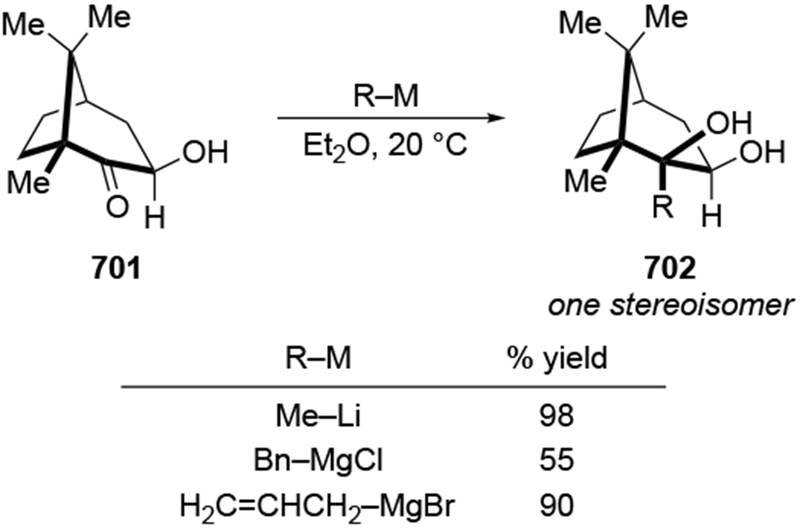

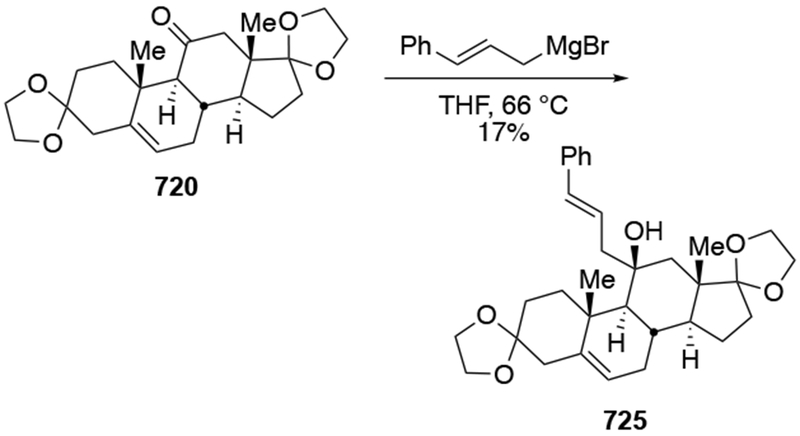

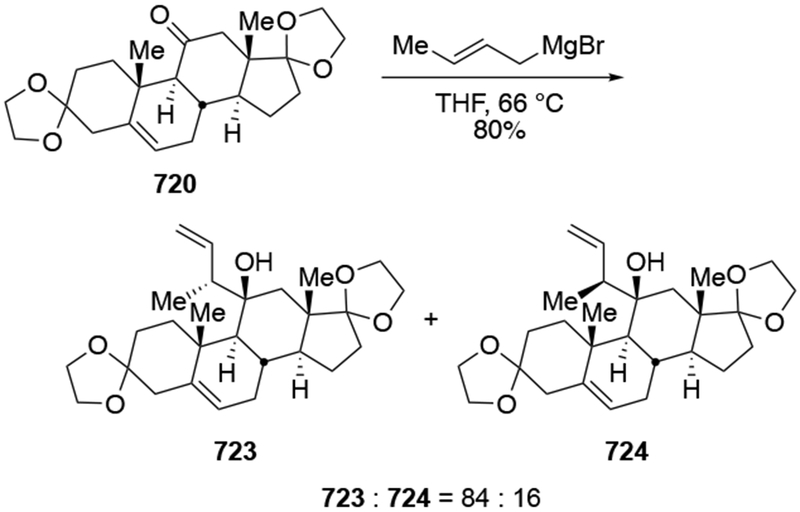

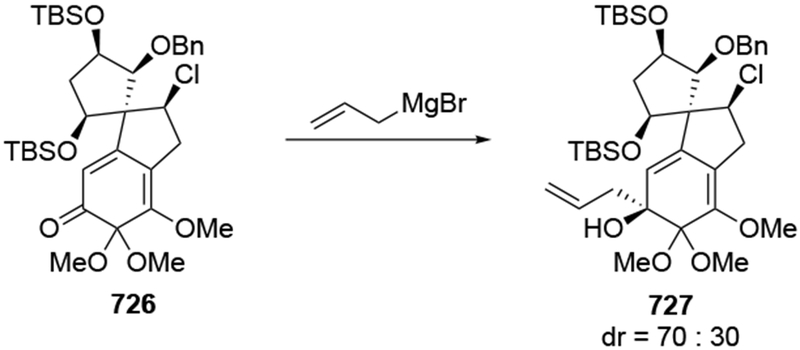

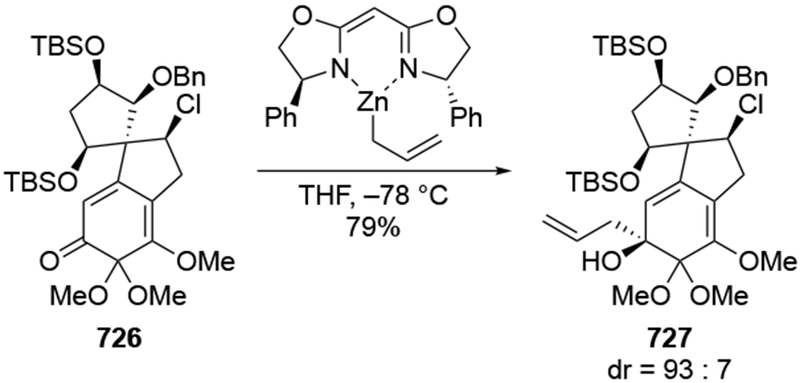

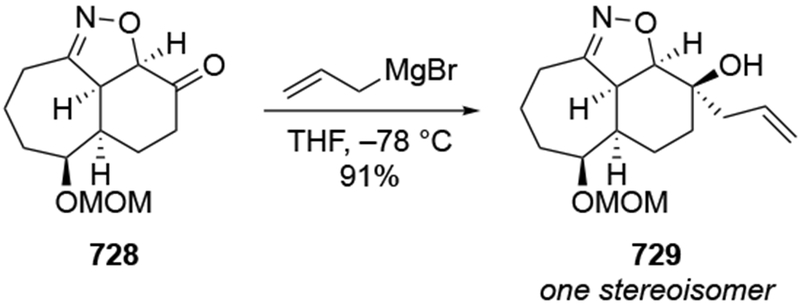

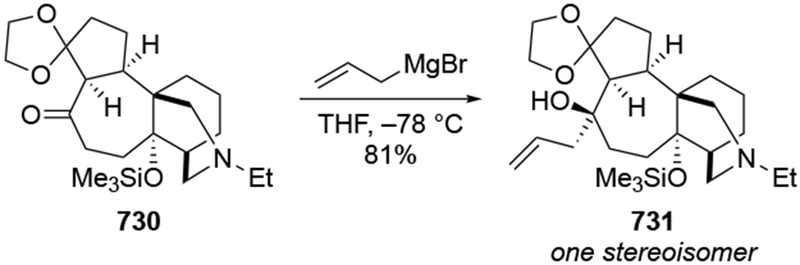

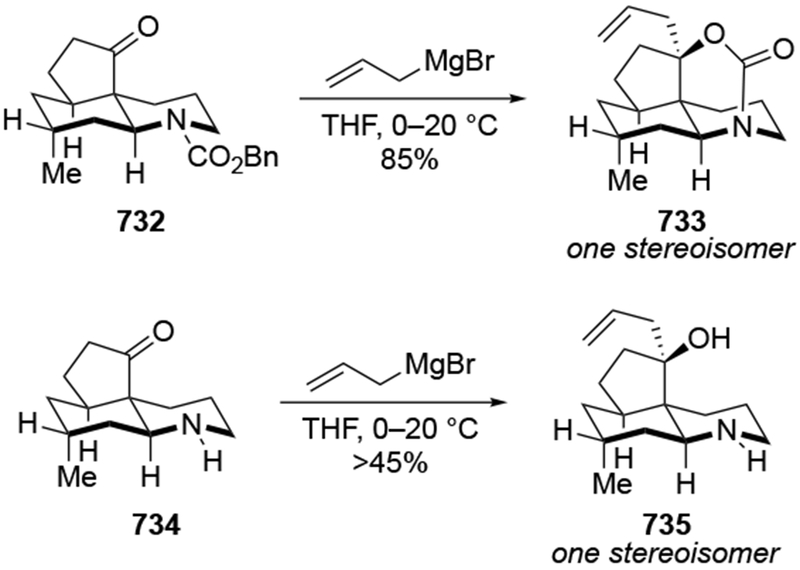

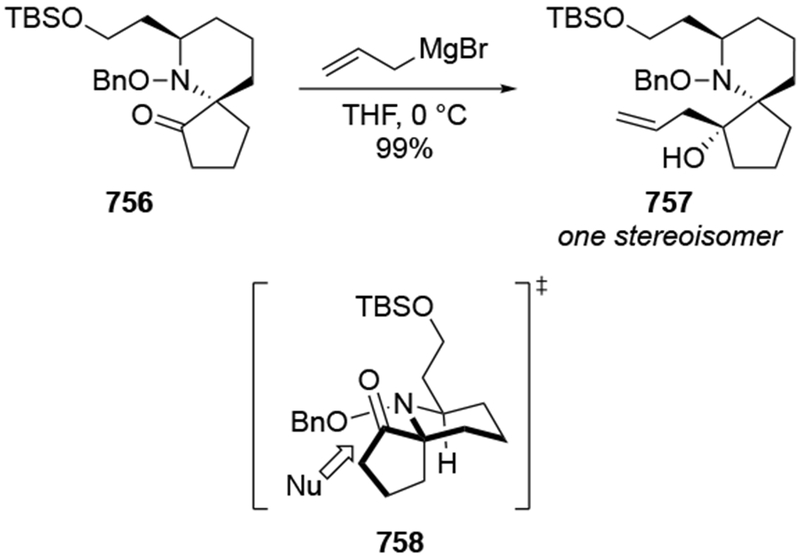

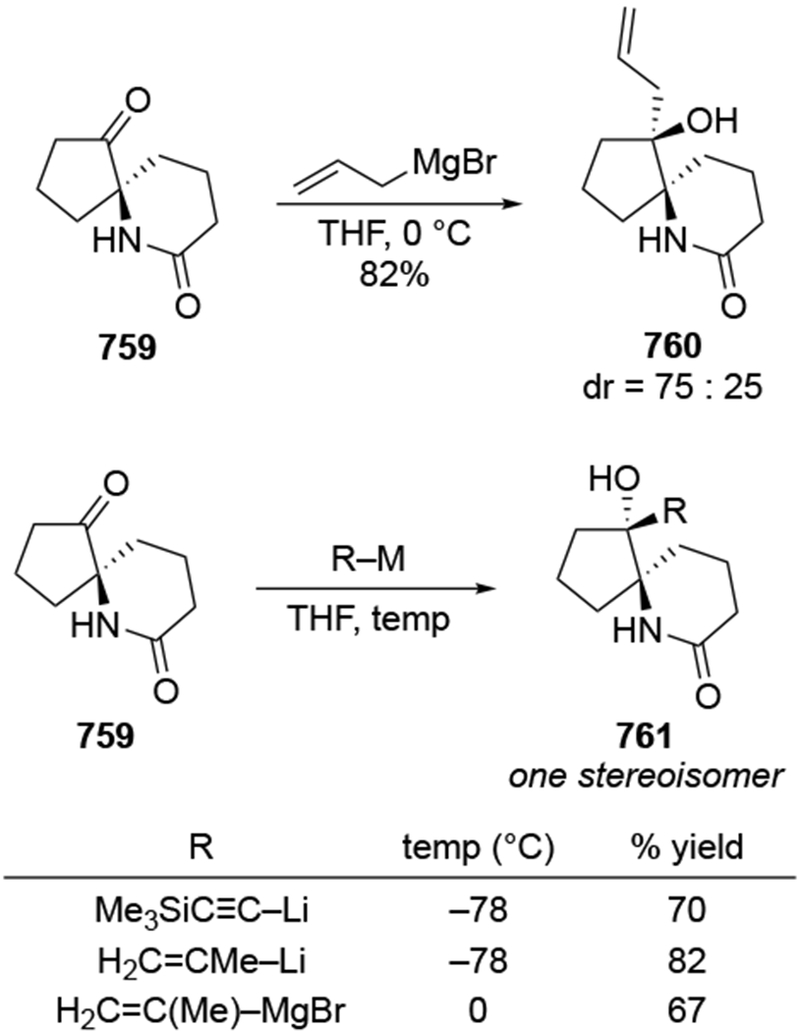

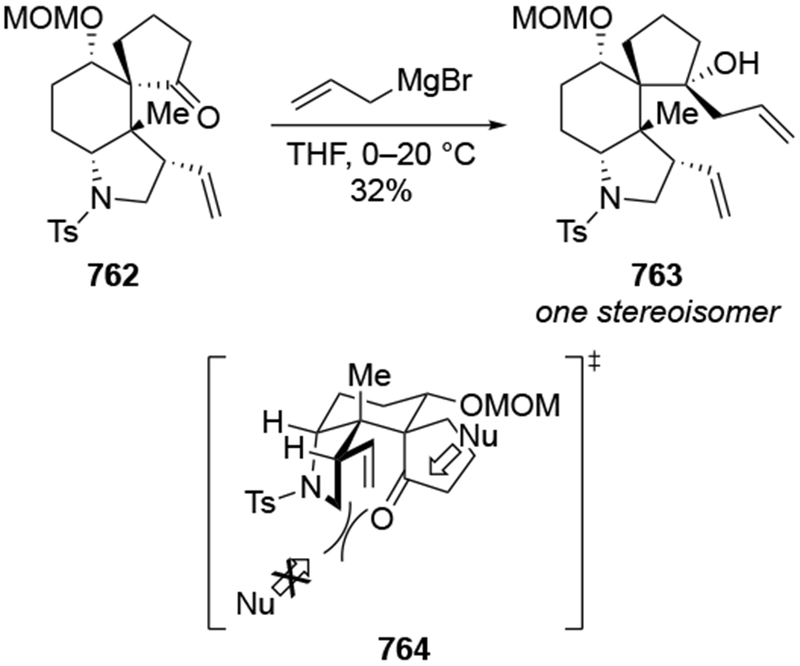

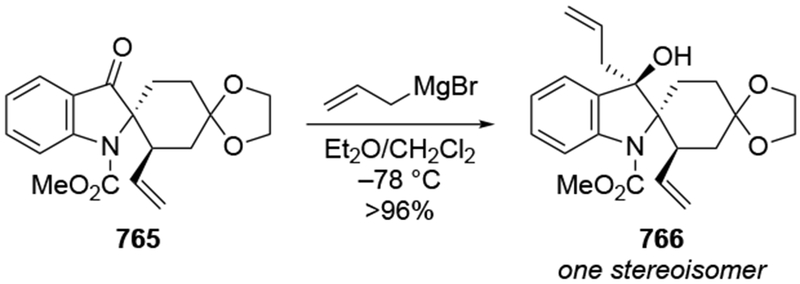

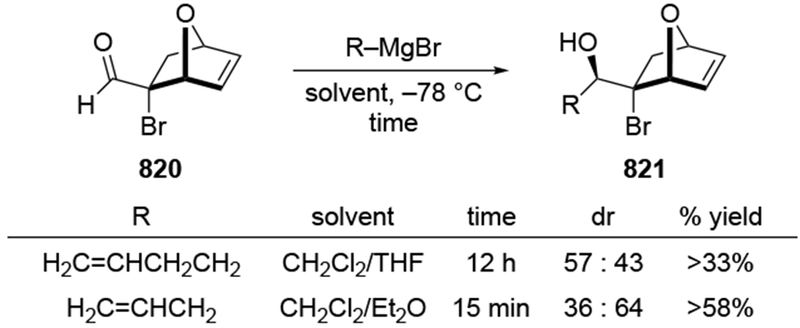

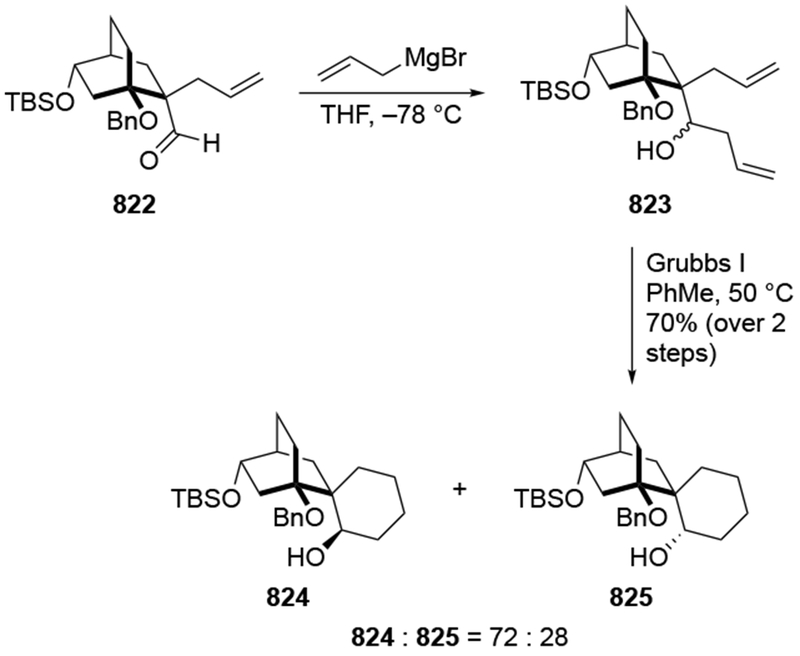

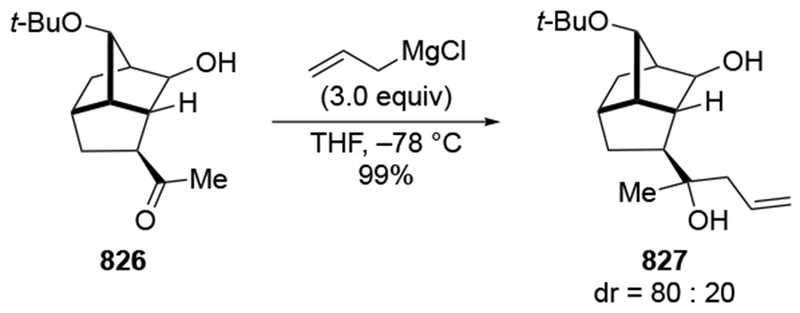

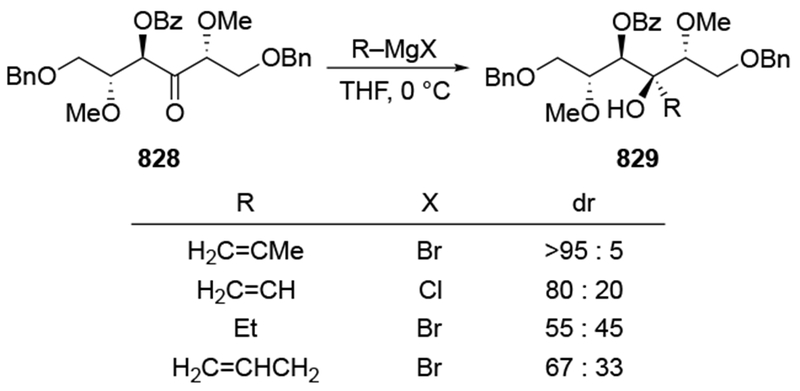

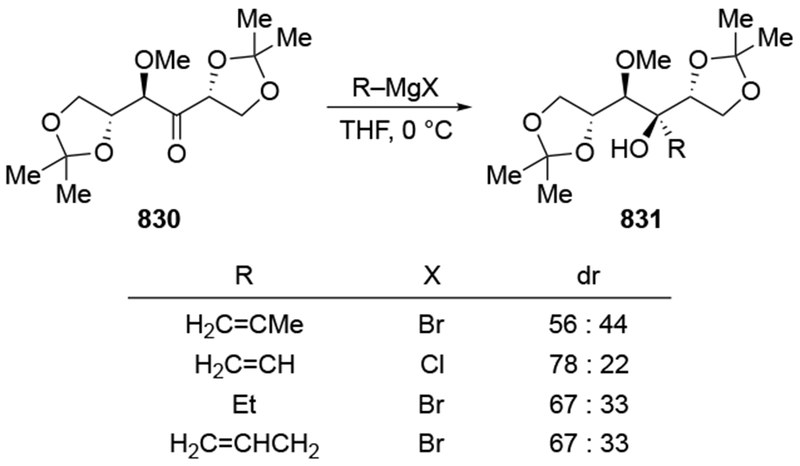

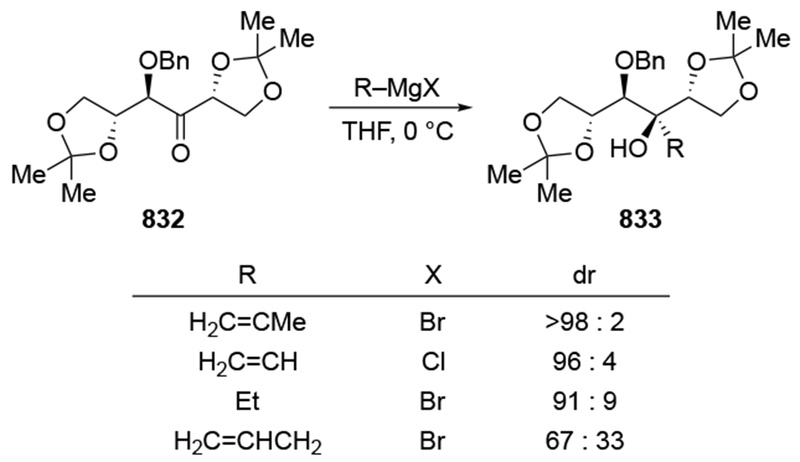

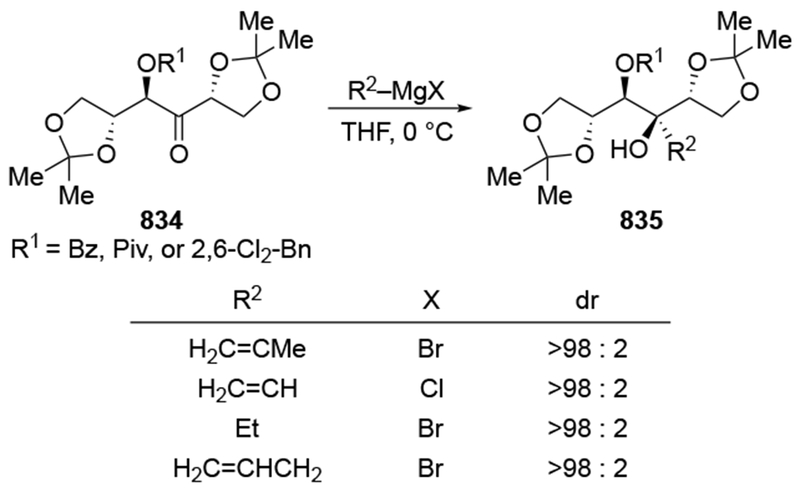

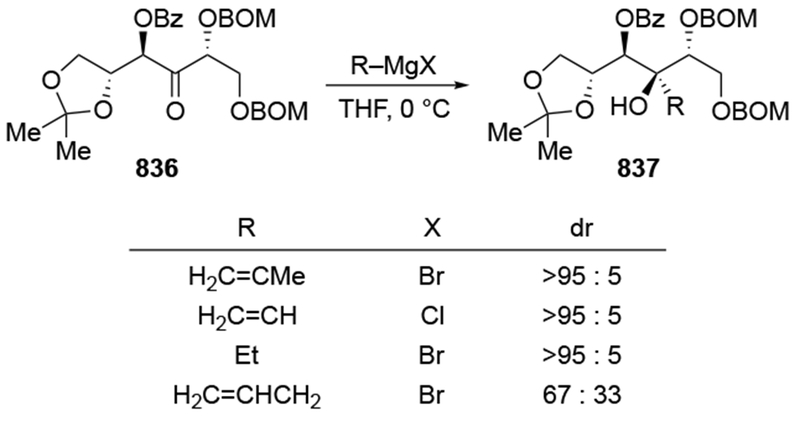

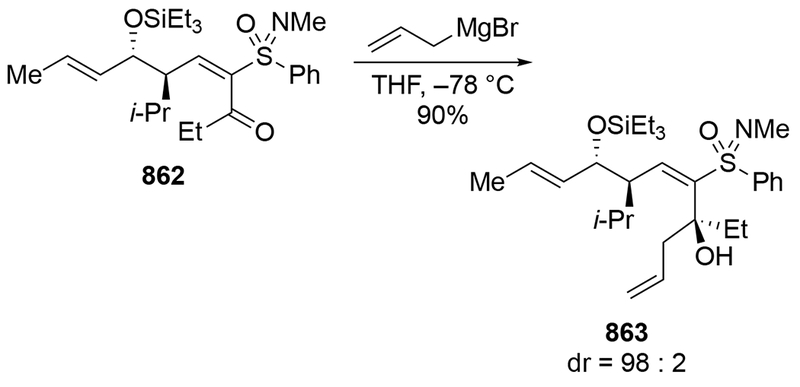

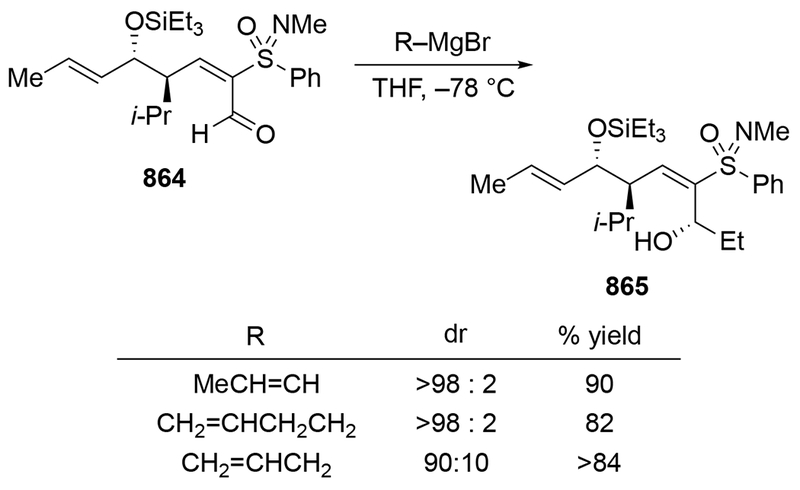

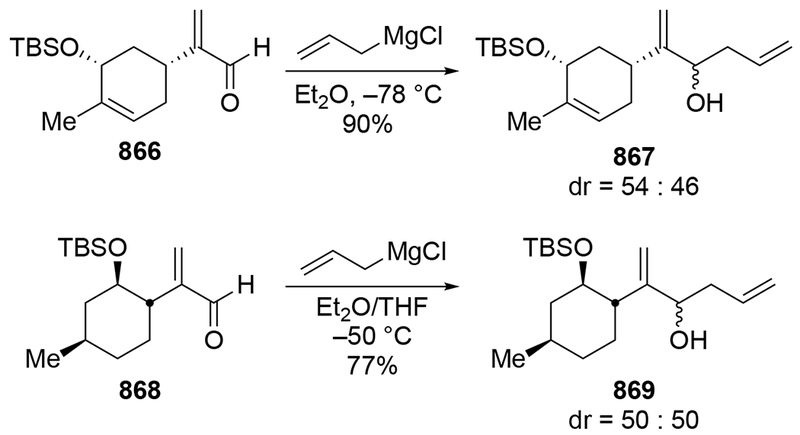

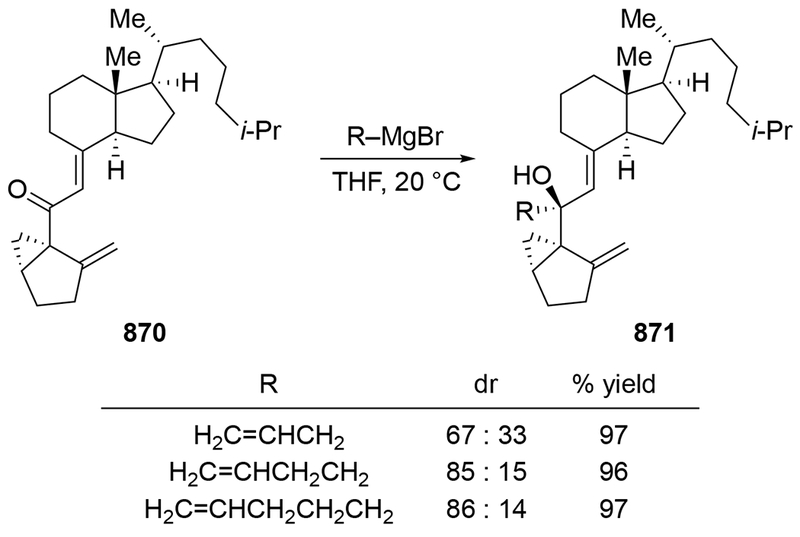

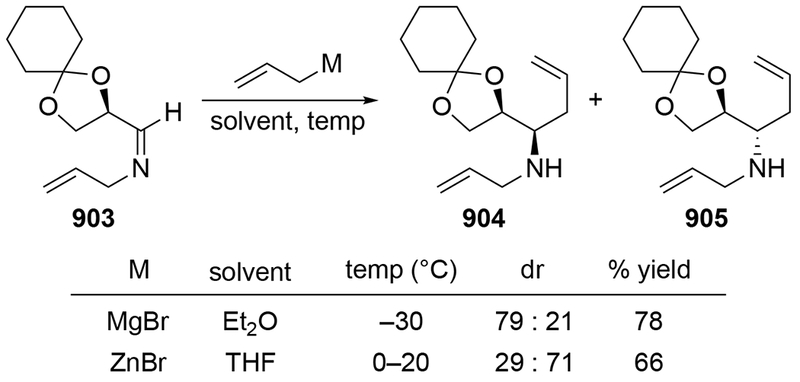

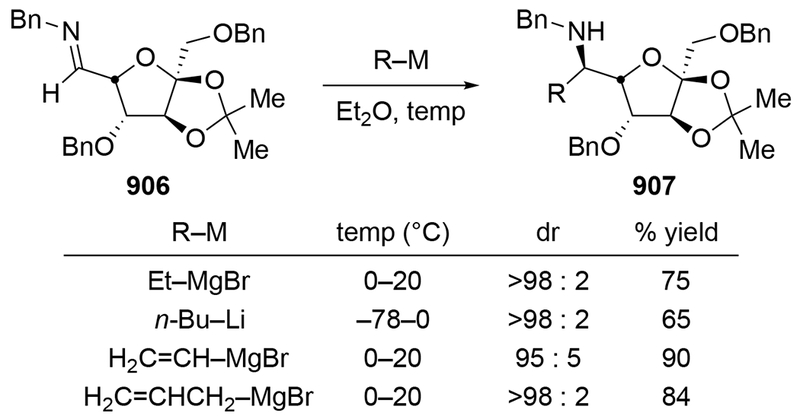

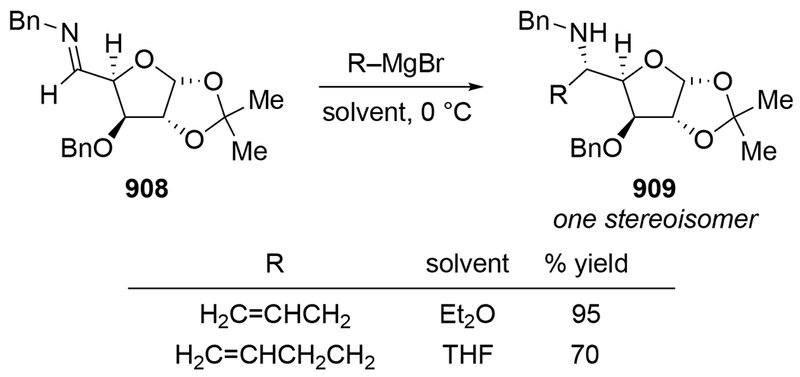

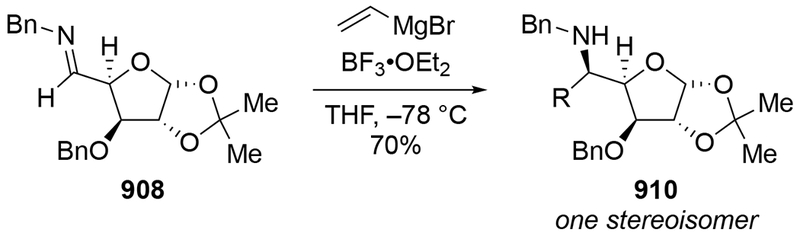

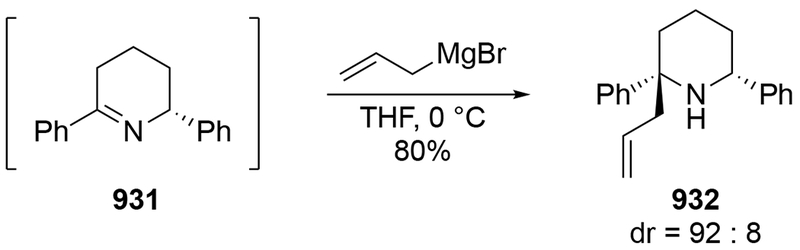

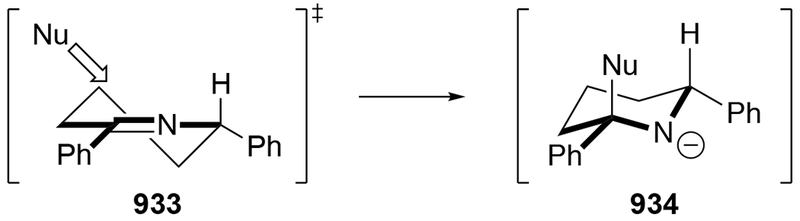

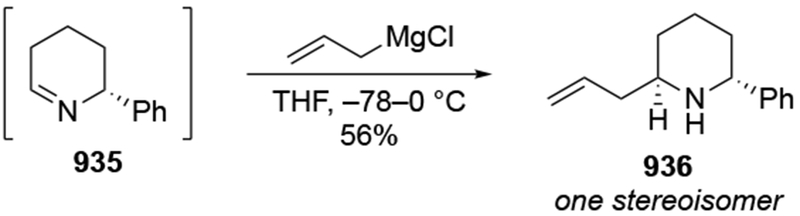

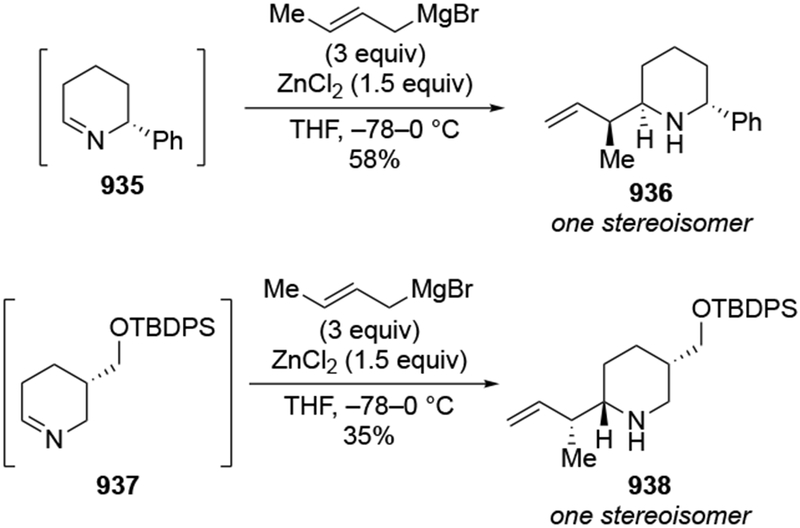

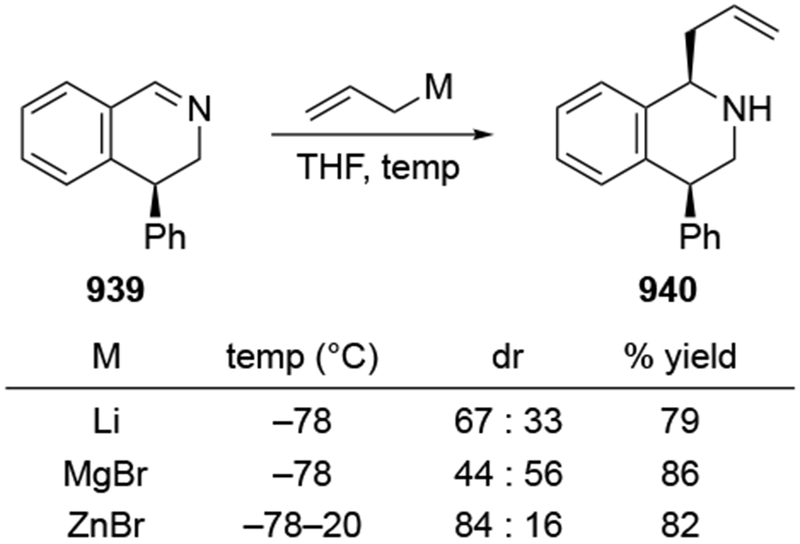

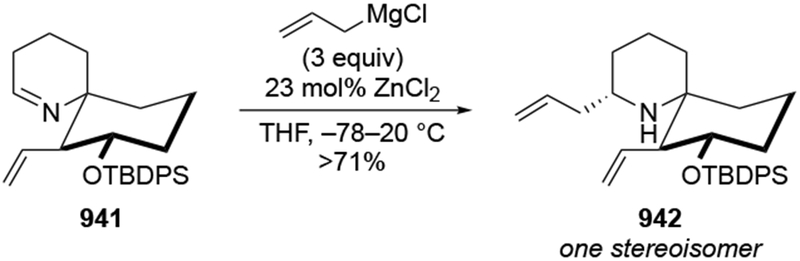

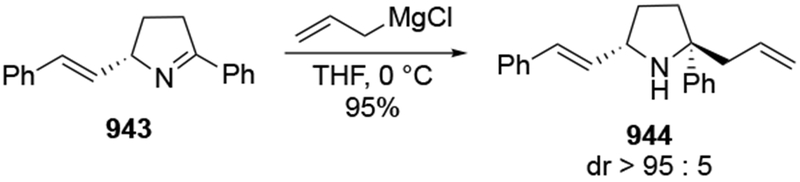

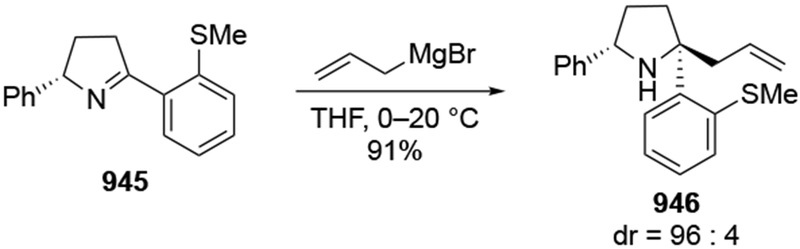

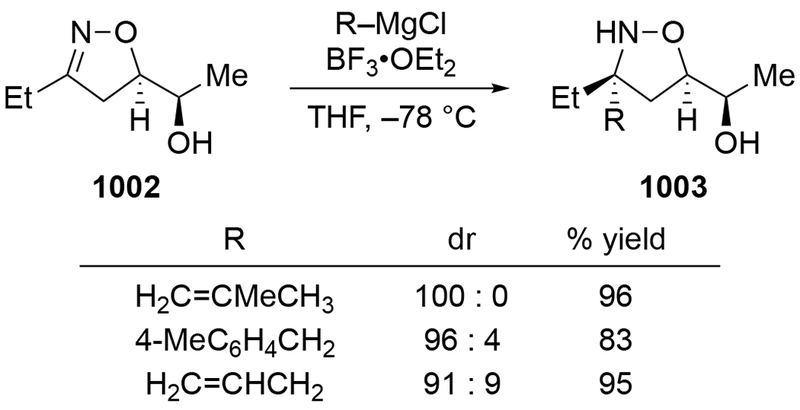

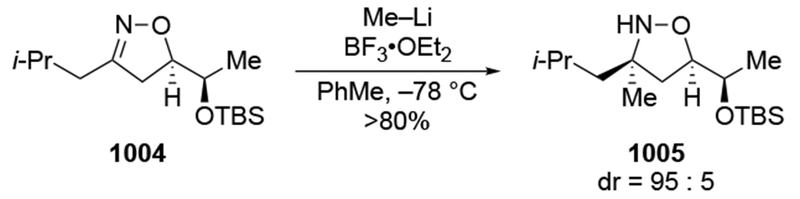

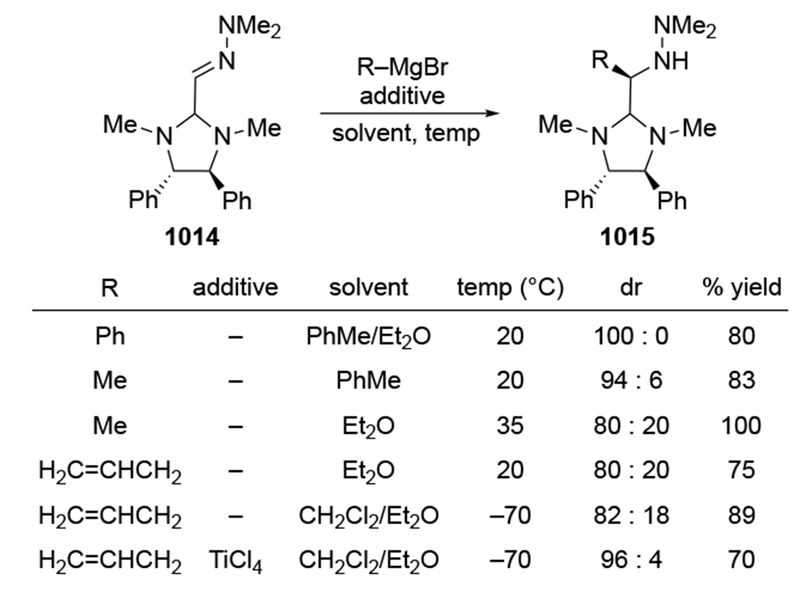

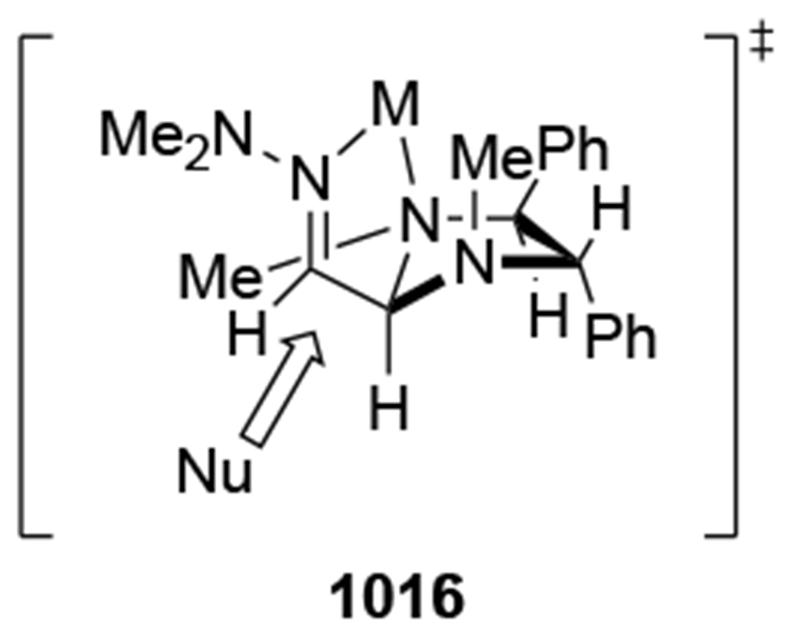

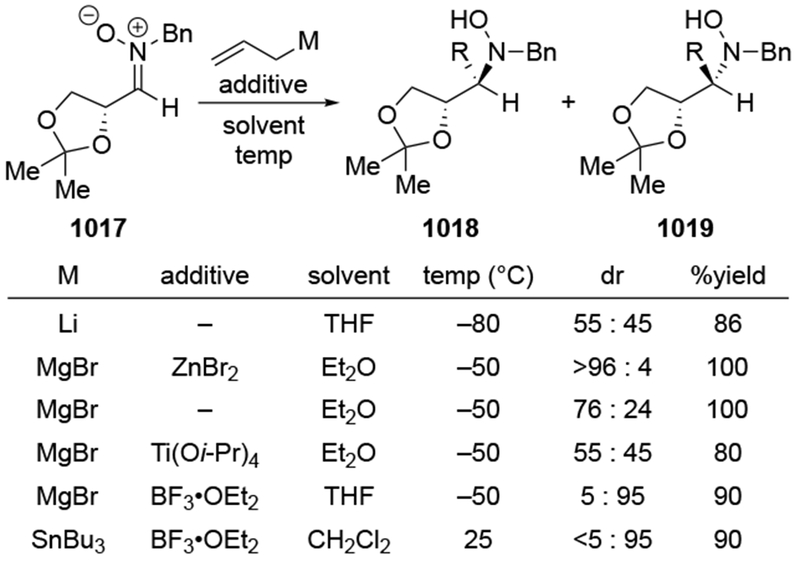

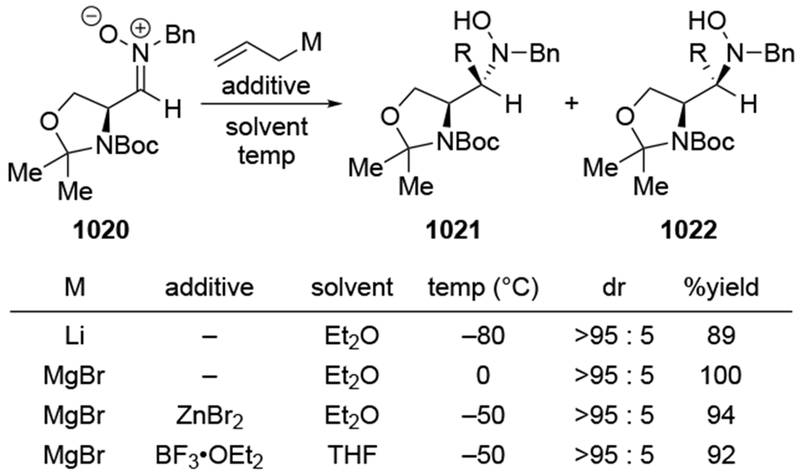

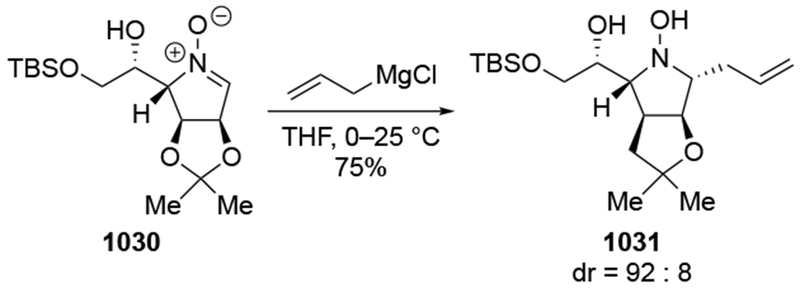

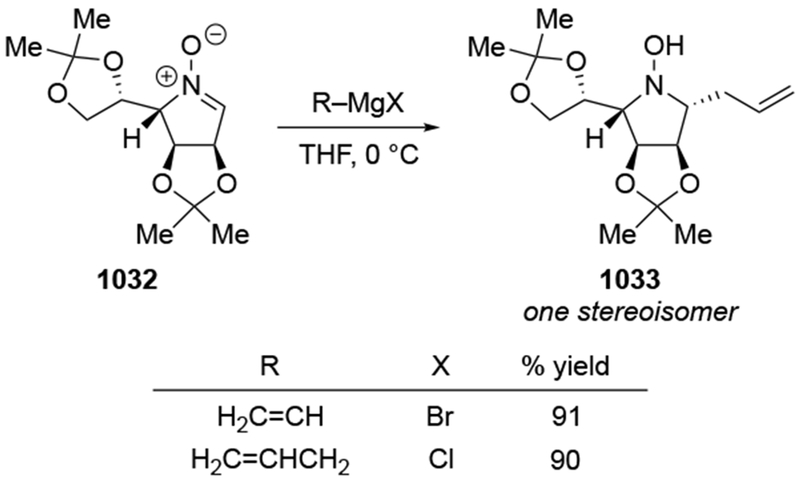

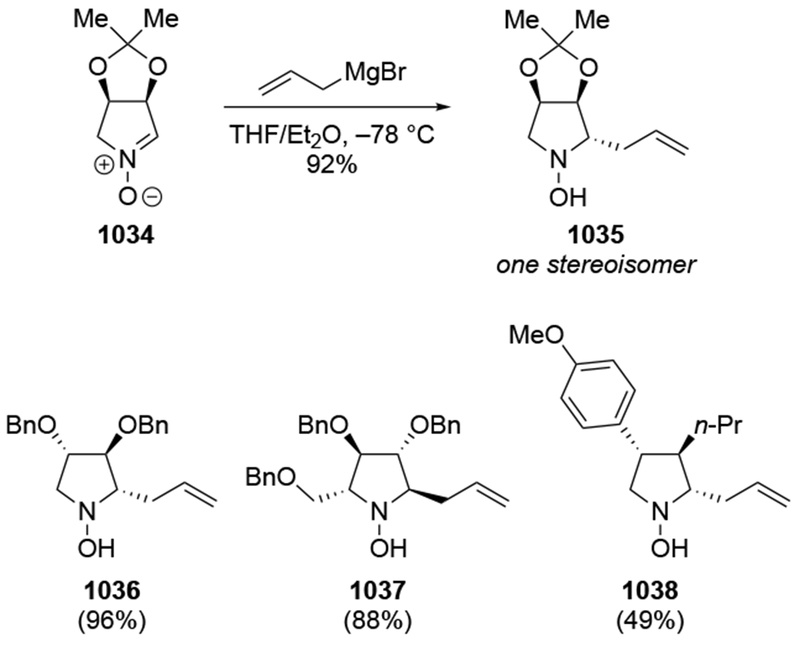

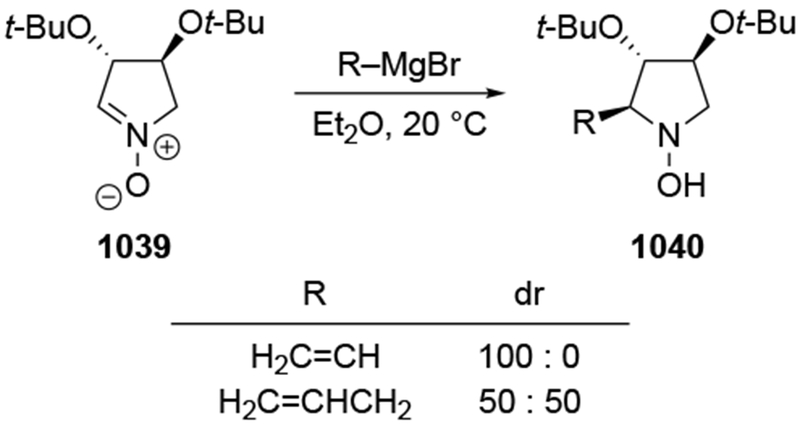

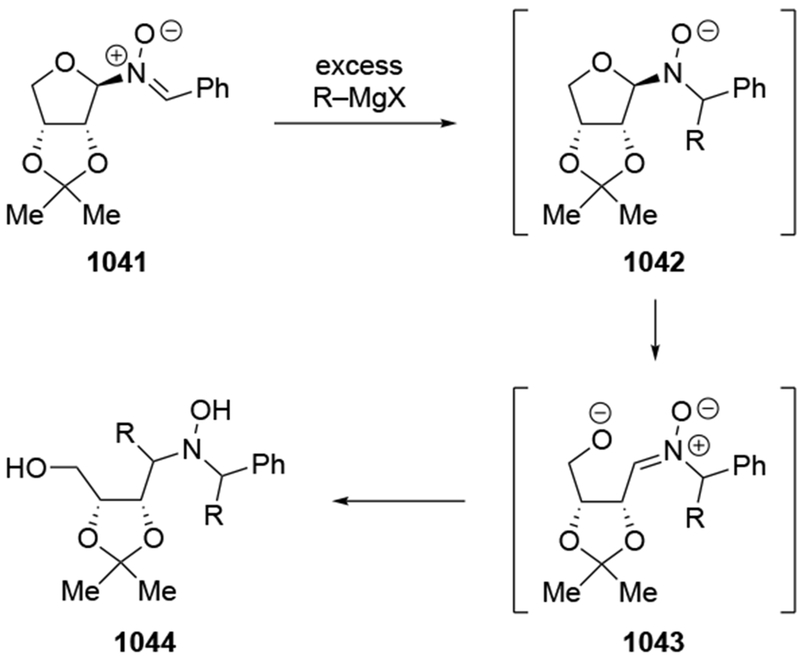

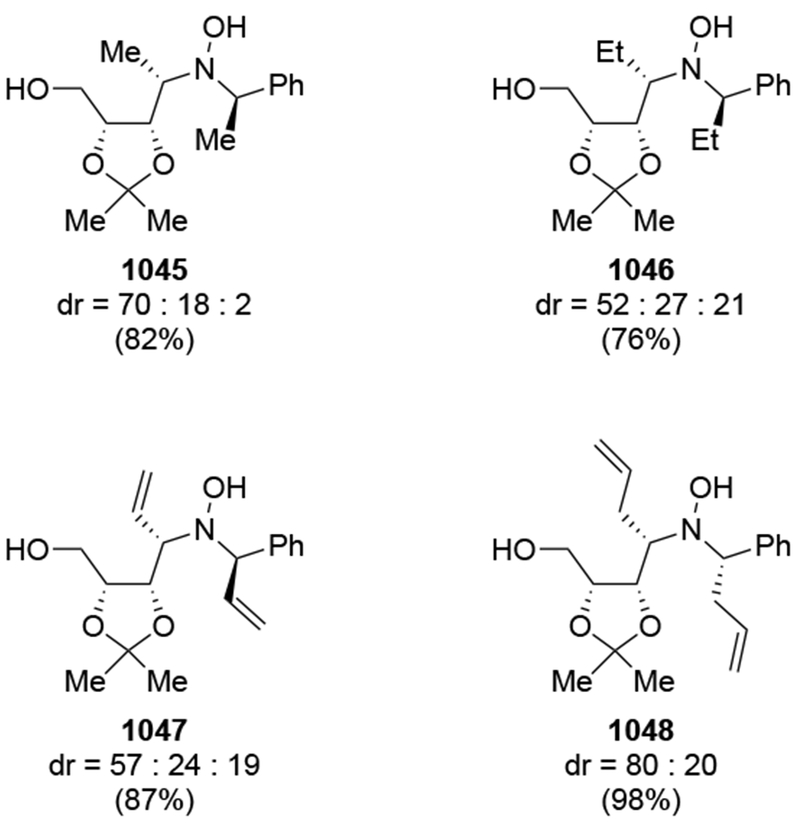

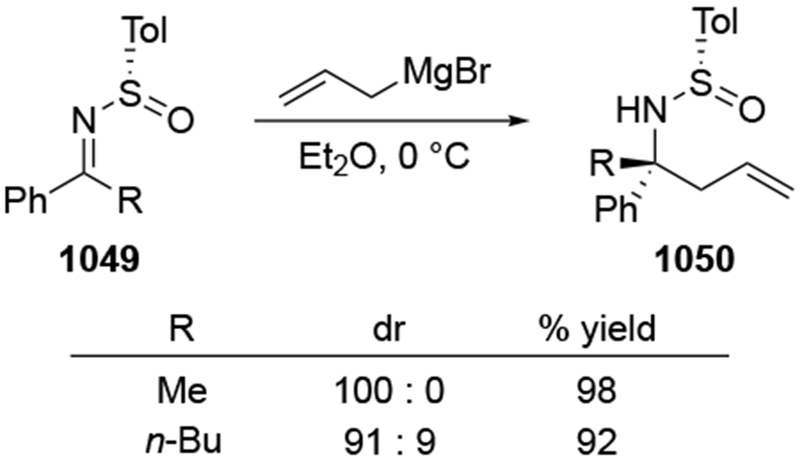

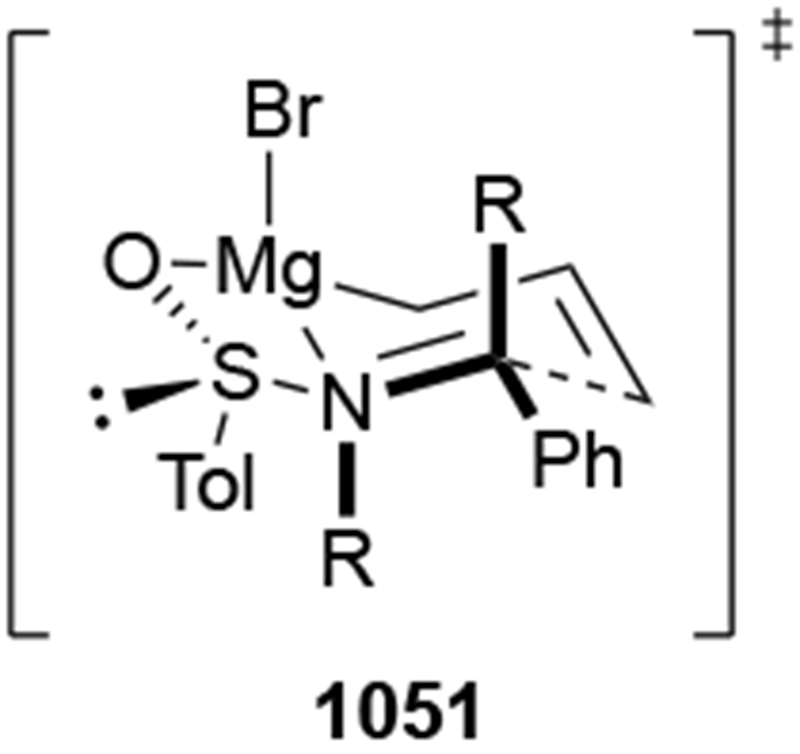

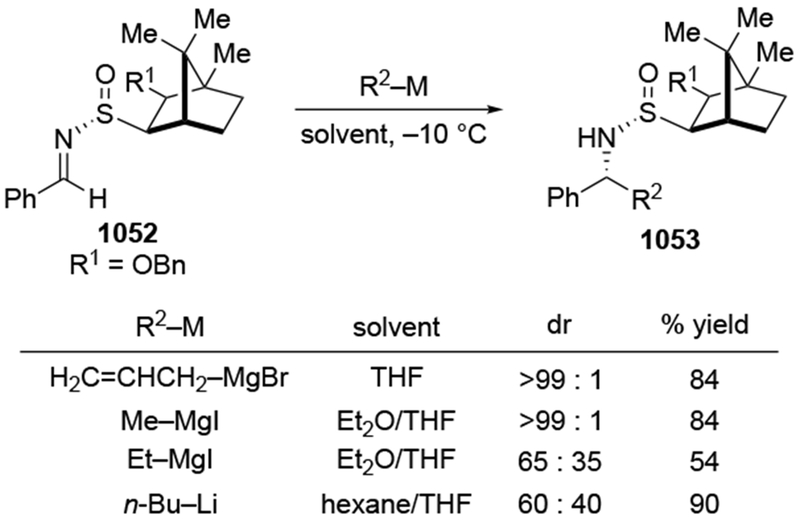

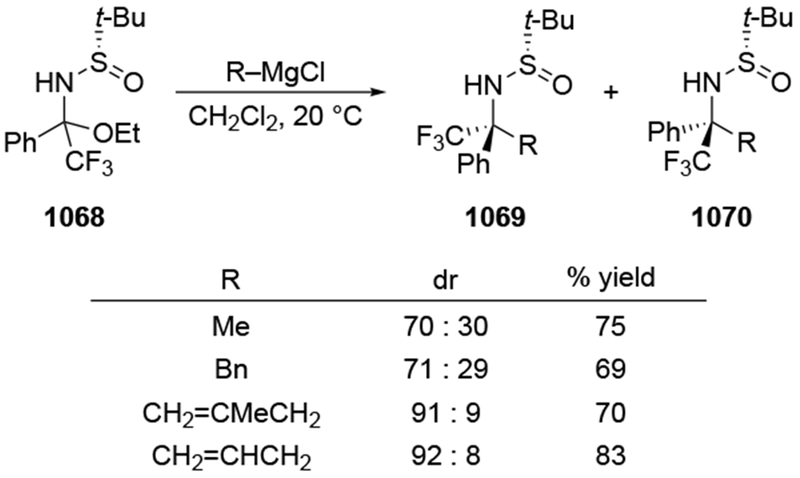

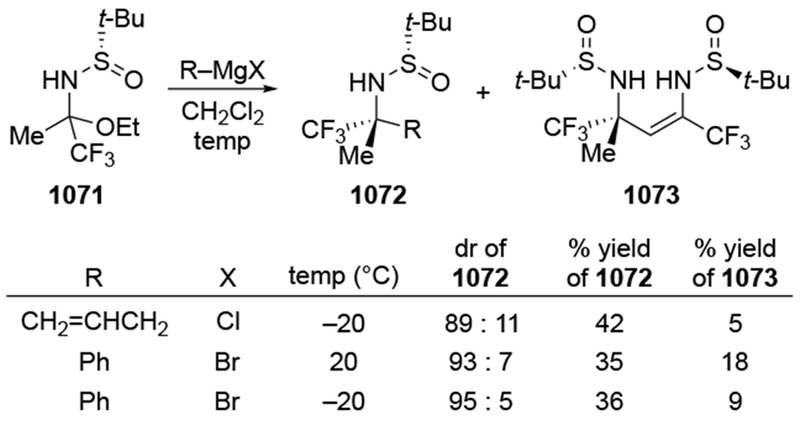

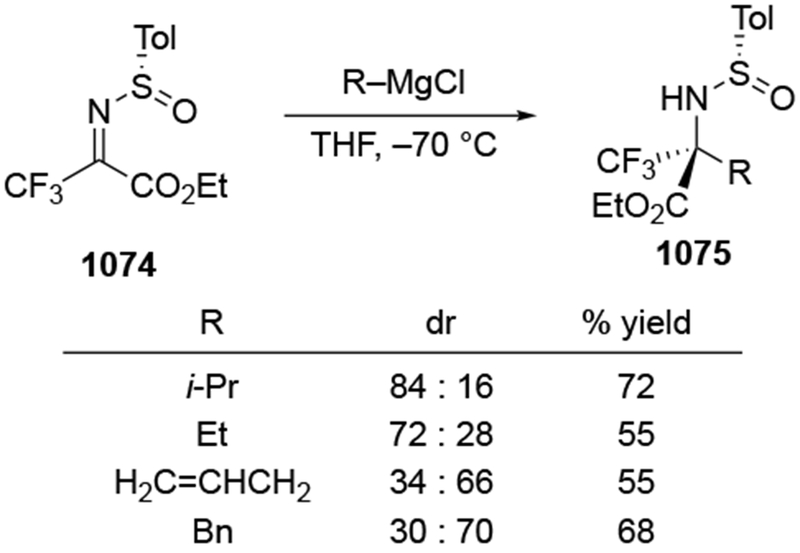

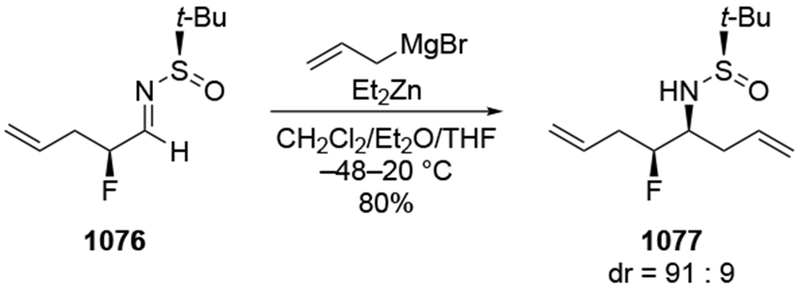

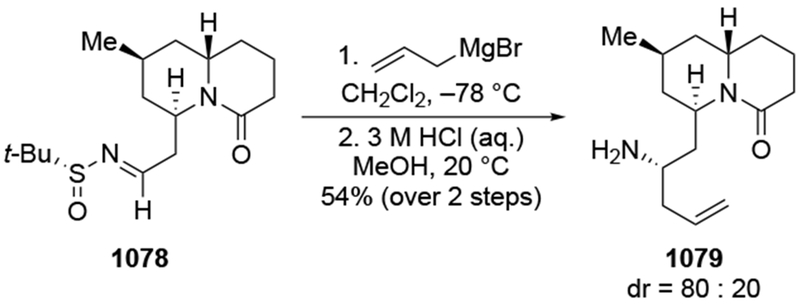

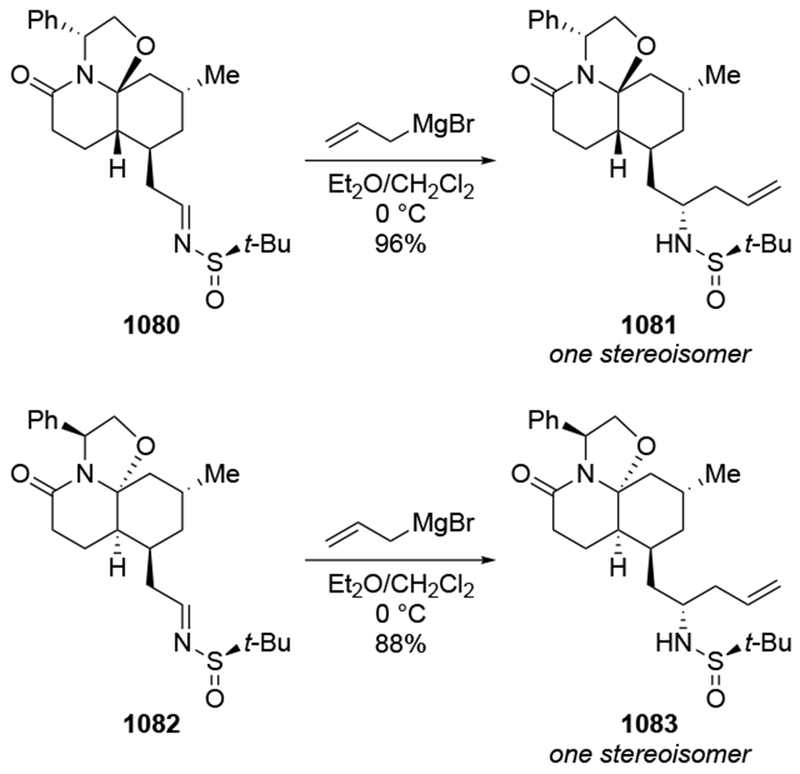

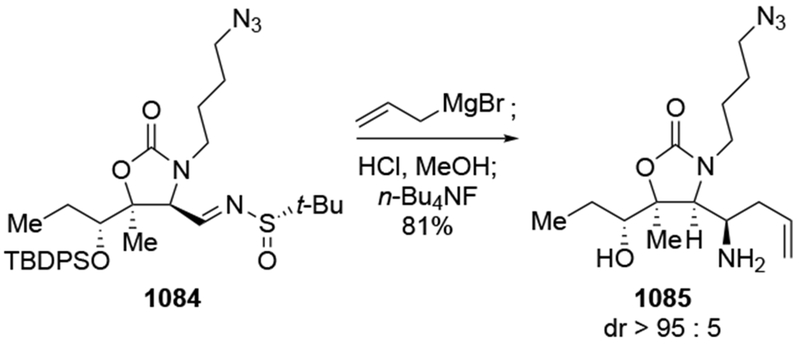

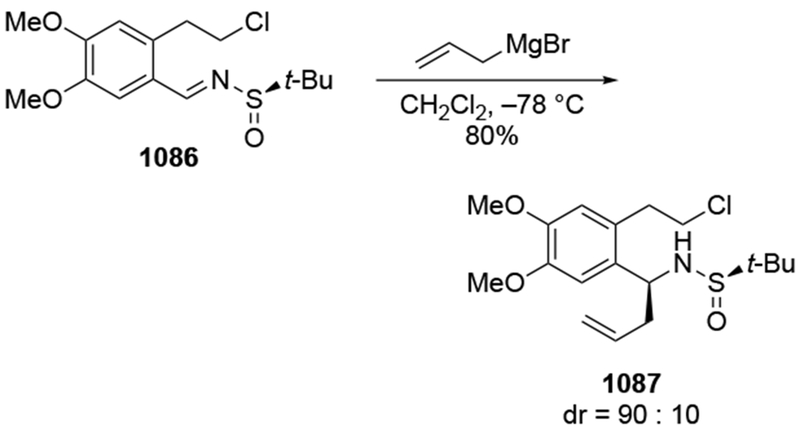

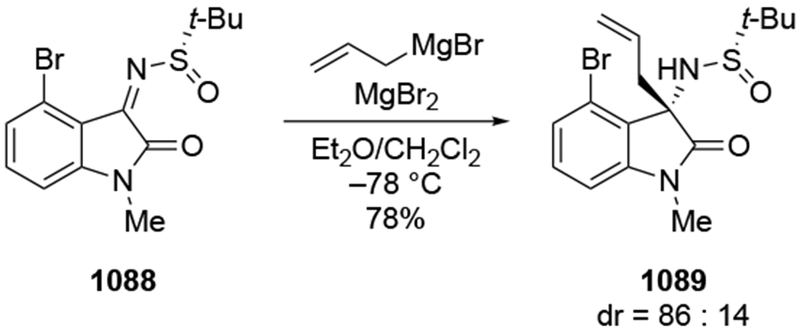

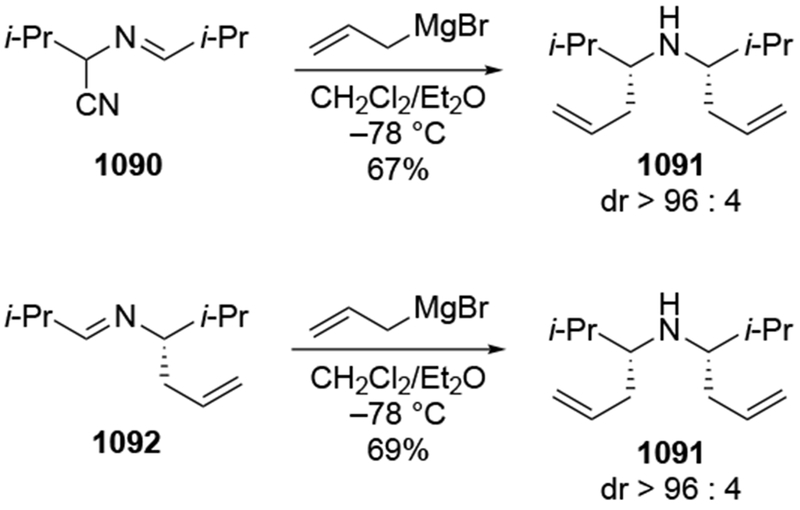

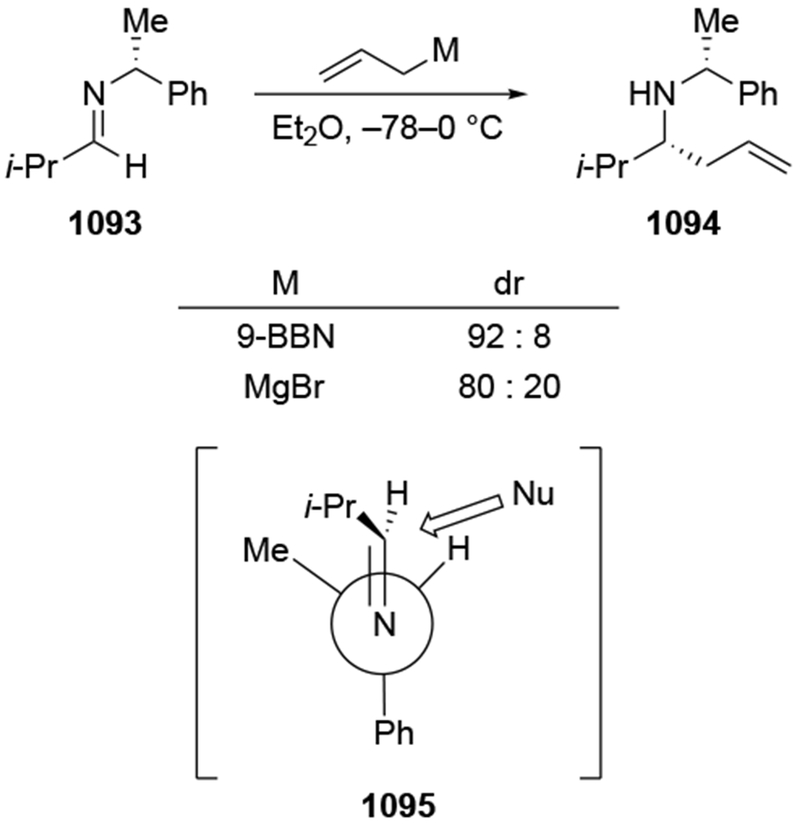

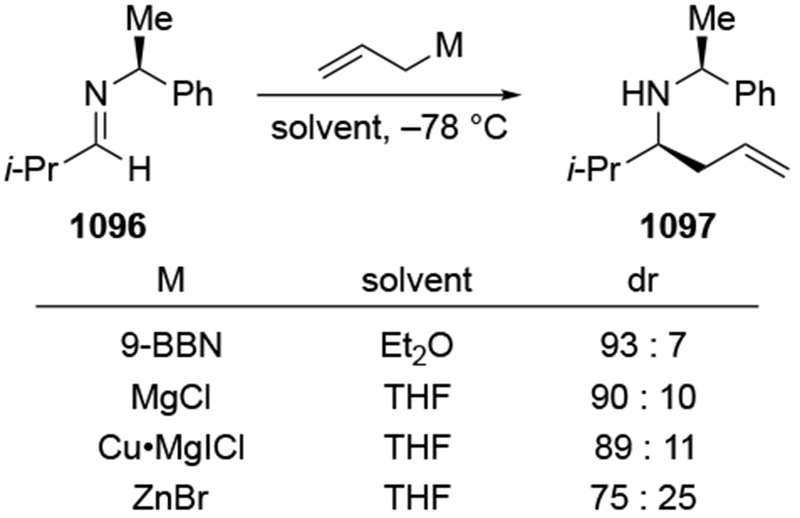

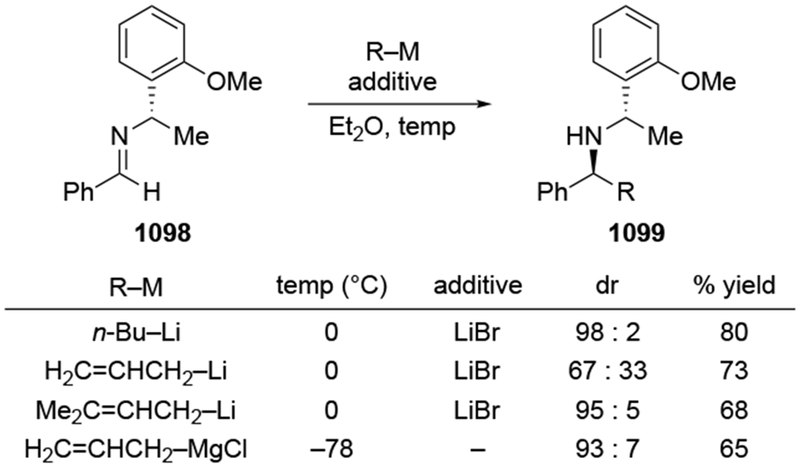

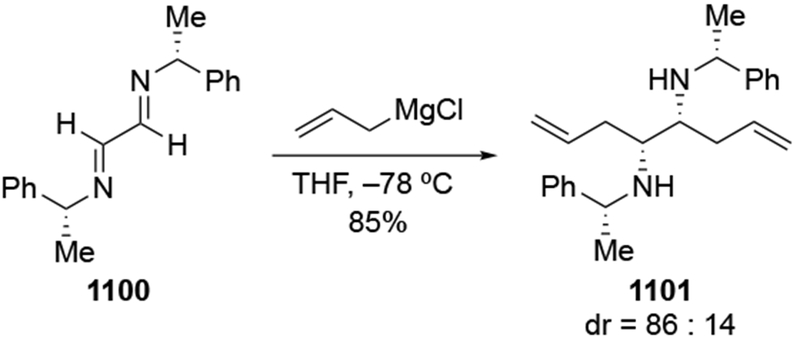

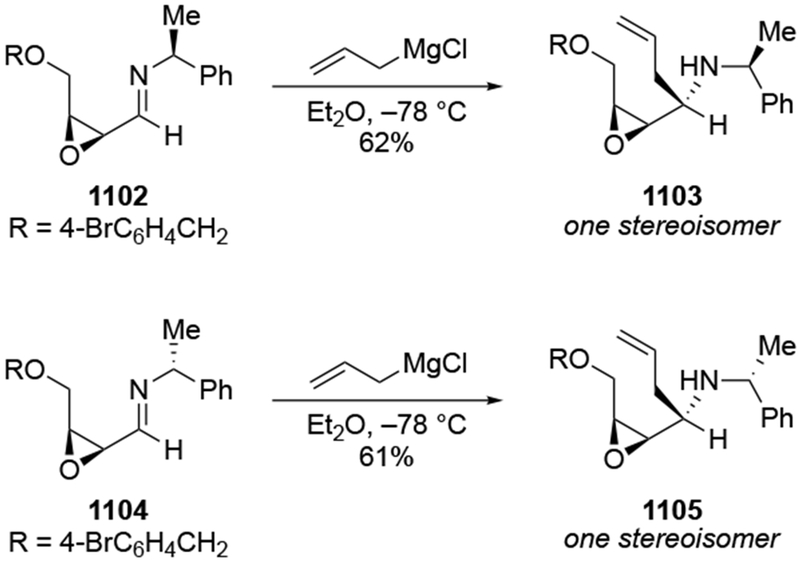

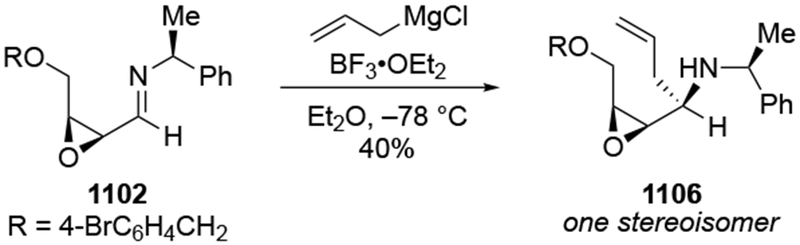

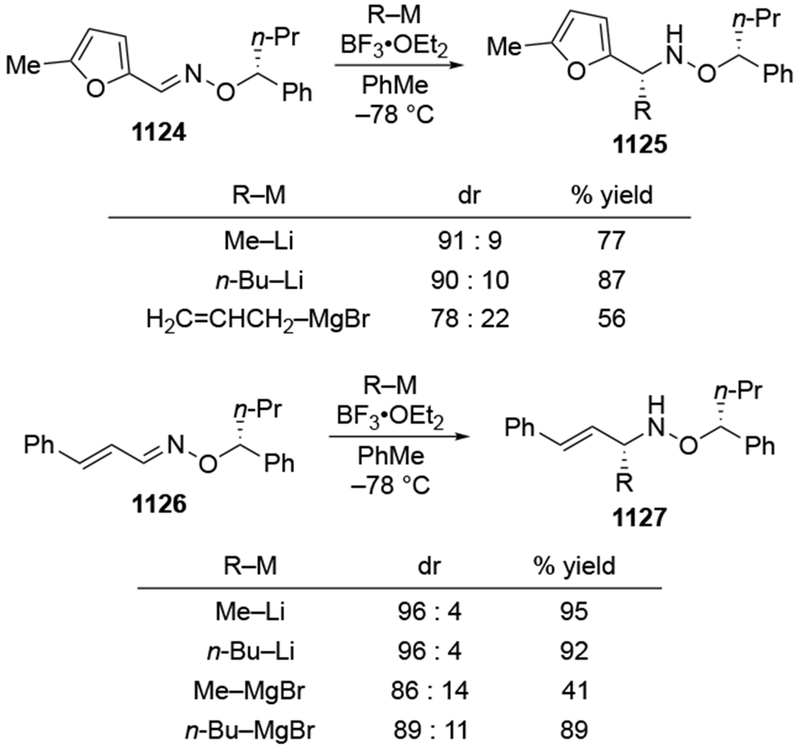

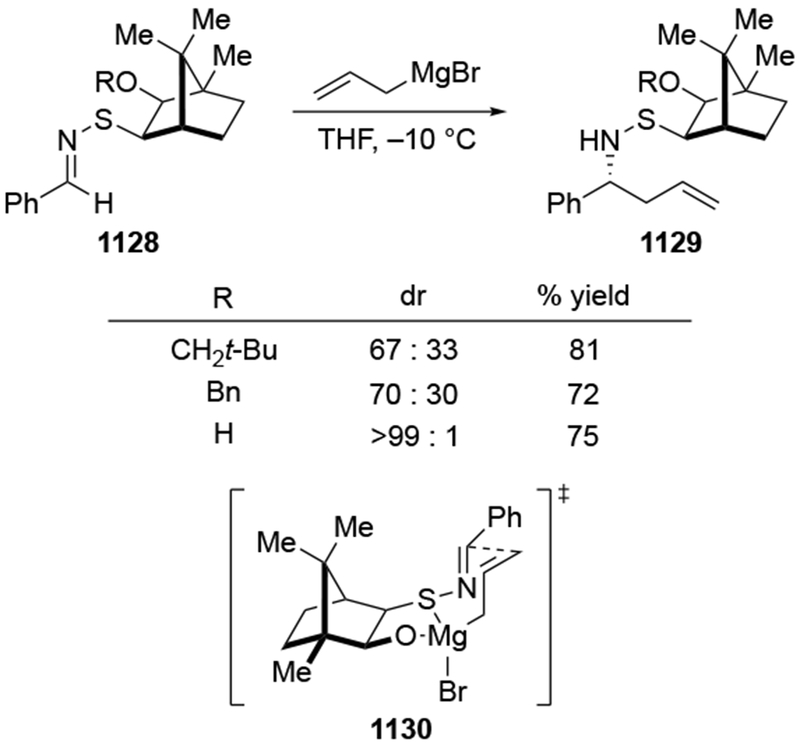

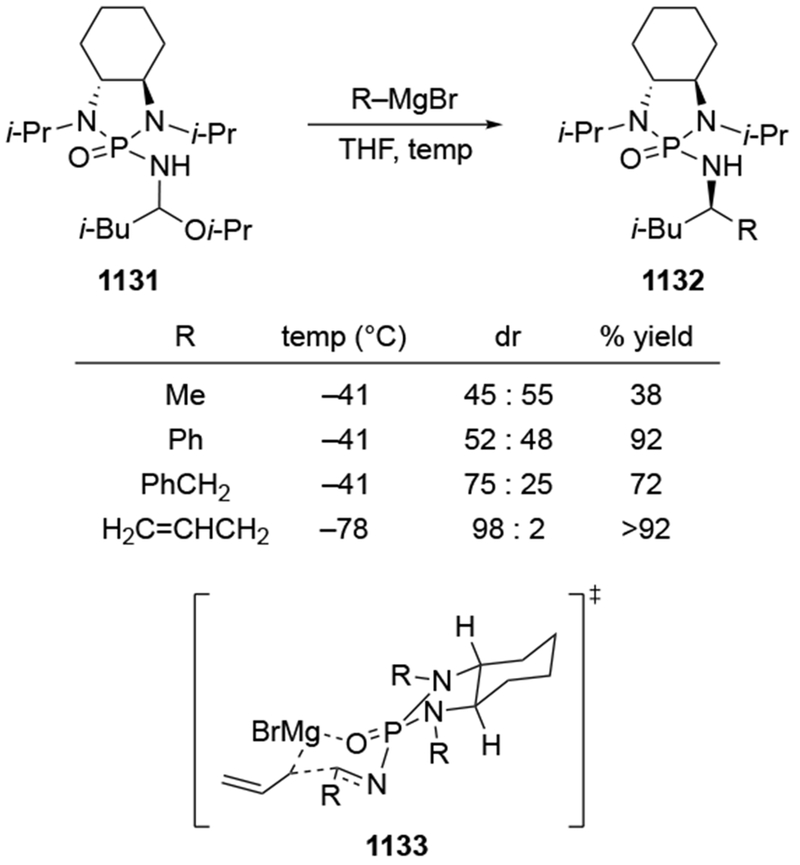

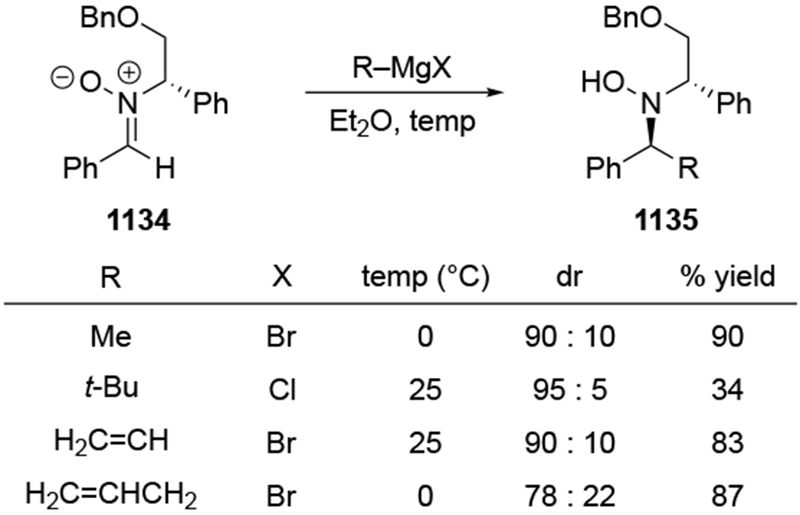

4.3.1.2. Additions to β-Hydroxycyclohexanones