Abstract

With increasing union dissolution and changing gender behaviour, questions have emerged about possible links between gender equality and union stability. The aim of this article is to examine whether and how early fathers’ involvement in child-rearing is associated with union dissolution in three Nordic countries. All three countries have reserved part of their parental leave to be used by one parent in order to promote fathers’ engagement in child-rearing. Our analysis uses fathers’ parental leave as a proxy for his involvement, and we distinguish between fathers who take no leave (“non-conforming fathers”), fathers who take only the reserved part (“policy-conforming fathers”) and fathers who take more than the reserved part (“gender-egalitarian-oriented fathers”). We find that couples in which the father uses parental leave have a lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which the father takes no leave. The pattern is consistent for all countries, for the whole study period 1993–2011, and for cohabiting and married couples. However, we do not find support for asserting that the couples with greatest gender equality, in which fathers take longer leave than the policy reserves, are the most stable unions, as the pattern is not uniform in the three countries. We attribute this to the fact that gender equality within the family in the Nordic countries is still an ongoing process, and the relationship between gender behaviour and union stability is still in flux.

Keywords: Union dissolution, Gender behaviour, Father involvement, Parental leave, Nordic countries

Introduction

With increasing union dissolution and changing gender behaviour, questions have emerged about possible links between gender behaviour and union stability. Theoretical explanations have changed over time. In the past, women’s economic dependence on their spouses was said to be an important reason for union stability, and increasing risks of union dissolution were linked to increasing female employment. The reason brought forth to support this assumption is that women in paid work are less economically dependent on their partner and have less to gain from marriage, and this increases the risk of divorce (Becker 1981). With increasing female employment and greater request for gender equality in society, the focus shifted from the role of women’s participation in the labour market to men’s participation in family work. The gender revolution theory links union dissolution risks to the stalled progress in men’s behaviour regarding family obligations (Goldscheider et al. 2015). It postulates that a more equal sharing of family responsibilities relieves women of the triple burden of employment, household work and care, leads to greater couple satisfaction and to closer ties between the children and their father. This in turn results in a higher threshold for couples to dissolve their relationship (Goldscheider et al. 2015).

The Nordic countries have a long tradition of promoting gender equality. With the explicit goal to reach gender equality, family policies have actively supported employment of mothers with young children. These have been complemented by policy amendments aiming at fathers’ earlier involvement in child-rearing and at changing the gendered division of unpaid work and care towards a gender-equal sharing of family responsibilities in general (Duvander and Lammi-Taskula 2011). To this end, the Nordic countries reserved a part of their gender-neutral parental leave to be used by one parent only, and this part may not be used by the other parent. This is intended as an incentive for fathers to take parental leave and start sharing child-rearing early on. Policies may also have consequences for areas of life that are not explicitly addressed when the policy is implemented and are thus also often overlooked by researchers investigating policy effects. One such aspect is the relationship between the use of parental leave and union dissolution. The point of departure for this study is to assess whether the theoretical postulation that greater gender equality within the family has a stabilizing effect on the union holds with respect to sharing parental leave between the parents.

The aim is to examine this relationship in three Nordic countries—Iceland, Norway and Sweden. The fact that part of the parental leave in these countries is reserved to each parent, thus exclusively to be used by the father (and the mother), offers the unique opportunity to explore how fathers taking no leave, only the reserved leave or more than the reserved leave is associated with union dissolution. This also offers us the opportunity to reflect on the role of policies as social norms and thus add a policy perspective to the theoretical assumptions about the links between gender equality and union dissolution. Iceland, Norway and Sweden rank highest on measures of gender equality. They also have similar family policies, similar high levels of female labour-force participation and relatively similar political and social conditions as well as similar patterns of family dynamics. We use administrative registers of the whole populations of (men and women) in Iceland, Norway and Sweden to consider leave used by fathers as a proxy for their involvement in child-rearing—measured here in the first 18 months after the first child is born. In all three countries, parents receive financial compensation during parental leave that replaces between about 80 and 100% of their previous income. Reserving part of the leave for one parent started as a unique Nordic feature more than 20 years ago first in Norway, followed by Sweden and Iceland, and although the reserved shares of the leave varied over time and across countries, studies show fathers use the reserved leave (Dahl et al. 2014; Duvander and Johansson 2012; Arnalds et al. 2011). In the two other Nordic countries, Denmark and Finland, policies have been less consistent with respect to reserving part of the parental leave for the father.

Following the implementation of a reserved part of the parental leave, the taking of leave by fathers developed into a social norm in all three countries. Fathers are expected to take at least the reserved part of the leave, and the vast majority of fathers nowadays does so. In the present study, we group couples according to their different policy-related behaviour. Fathers who take no leave represent “non-policy-norm” behaviour, and since taking leave is a social norm, justification for such behaviour is often expected. Fathers who take up to their reserved part represent “policy-norm”-conforming behaviour, while fathers taking more than their reserved part represent “gender-egalitarian” behaviour. By examining union dissolution among these groups, we provide new insights into how a policy with the explicit aim to change the division of care and unpaid responsibilities within the family is associated with union stability. By replicating our analysis in three contexts, we provide evidence that the postulated relationship between early father involvement and union stability has a general application, but we also show that the assumption that greater gender equality is associated with more union stability needs to be more nuanced.

Theoretical Considerations

Two main theories have dominated the interpretation of the relationship between gender equality and union stability. One theory focuses on the changing gender composition of the labour market, the other one on gender (in)equality in the family. We add a third approach to these, namely a political perspective of the tension between norms induced by a policy and gender-egalitarian norms prevalent in society. We briefly outline each of these and how they are related to each other.

Women’s Labour-Force Participation and Union Dissolution

The theoretical assumptions about women’s employment and union stability start from the notion of gender inequality in the family as a prevailing social norm and the economic gains from it. In traditional male breadwinner-female caregiver societies, gender specialization is said to increase couples’ mutual dependence, and this in turn is seen as maintaining union stability (Becker 1981). Women’s increasing labour-force participation is argued to empower women economically and to reduce their dependence upon men (Oppenheimer 1994). This poses a threat to the benefits of specialization and increases the risk of divorce (Becker 1985; for a critical view of this assumption, see Oppenheimer 1994, 1997; for a discussion Cooke 2006).

From an intra-couple perspective, Breen and Cooke (2005) argue that when both men and women participate in the labour market, the division of paid and unpaid work becomes the result of negotiations between the spouses. Women’s economic empowerment increases their bargaining power and this may have two consequences: either men cooperate more in family work and this will contribute to the sustainability of the union, or men are non-cooperative and this will increase divorce risks. Breen and Cooke (2005) furthermore maintain that only an increase in the share of women with sufficient economic autonomy to threaten non-cooperative men with divorce will lead to a change in men’s gender ideology and in the division of household work within a society.

The Gender Revolution and Union Dissolution

The gender revolution theory (Goldscheider et al. 2015) focuses on family dynamics and relates union dissolution to two phases of change in the gender behaviour of women and men. According to this theory, the first phase of the gender revolution is characterized by a dramatic increase in female employment and a gain in women’s financial autonomy. Despite women’s breadwinning contributions to the family, the gender division of work within the family remains largely unchanged. This multiplies the burden on women, weakens the family and increases the risks of union dissolution.

The second phase of the gender revolution is characterized by men taking on more or the same domestic obligations as women. The theory predicts that this leads to a new work–life balance and a more gender-equal relationship between the partners, resulting in greater union stability (Goldscheider et al. 2015). Similarly to Breen and Cooke (2005), the gender revolution theory attributes the risk of union dissolution in the second stage of the gender revolution to men remaining non-cooperative, while during the first stage of the gender revolution, the risk of union dissolution is mainly attributed to women’s increasing employment.

Researchers of the labour-market-centred as well as of the gender-revolution-centred approaches argue that the dynamics between women’s increased labour-force participation, men’s sharing of household work and union dissolution may depend on the social and policy context (Breen and Cooke 2005; Cooke 2006; Goldscheider et al. 2015). Several studies of union dissolution in different countries support their assumption (Cooke 2006; Sigle-Rushton 2010; Oláh 2001). Cooke et al.’s investigation of divorce risks in eleven Western countries reveals that the stabilizing effect of a gendered division of labour has ebbed, yet still differs across policy contexts: in liberal and gender-conservative countries, wives’ employment has no or an elevating effect on divorce risks, but in countries with policies supporting gender equality, wives’ employment is negatively associated with divorce risk (Cooke et al. 2013).

Policy Norms, Gender Norms and Union Dissolution

The theoretical and empirical work by scholars outlined above suggests that policies set the frame for women’s employment, for negotiating a more gender-equal sharing of family obligations among the partners, and for men’s involvement in domestic work. One policy that directly affects the gender division of family work and employment is parental leave, that is, paid leave from employment to care for a newly born child during the first year(s) of his or her life. It has usually been mothers who took this leave. To provide an incentive for fathers to take leave and initiate a more gender-equal division of parental leave and subsequent child-rearing, several countries have reserved part of the parental leave for one parent, and this part may not be used by the other parent. Such a reserved part of parental leave poses a challenge to the theoretical assumptions about women’s employment, men’s family work, gender equality and union dissolution, for the employment-centred and the gender-revolution-centred theories assume that the changes in gender behaviour are part of a social development and occur without direct state intervention. The reserved part of the parental leave to fathers may generate a tension between the politically assigned option for a more gender-equal division of care and the existing social norms regarding gender and care. This may alter the theoretically assumed relationship between gender (in)equality and union dissolution. The direction of the change may depend on the construction of the parental leave and on the gender norms in society.

The introduction of a reserved part of the parental leave may foster a faster development towards more gender-equal norms in society at large. The reserved part leads to a new norm of fatherly behaviour regarding parental leave. It eases intra-couple negotiations about whether the father should or should not take leave and it bestows each partner with the legal right to request and take at least the politically allocated part. Couples in which fathers take more leave than the reserved part go beyond this policy norm and strive for a more gender-egalitarian ideal. The gender revolution theorists would argue that this strengthens the union and reduces the risk of union dissolution (Goldscheider et al. 2015). The more employment-centred researchers would contend that it only strengthens the union if gender egalitarianism is ideologically and practically shared by the majority of the population (Breen and Cooke 2005); otherwise, it would put pressure on the couple and increase the risk of break-up. In essence, we may conclude that the risk of union dissolution associated with the father taking the reserved part or more may depend on the match or mismatch between the leave policy and gender-egalitarian norms in society. From a policy perspective, we may therefore conclude that the dynamics between the changing gender relationships in employment and the family and union dissolution is intersected by existing policies as well as by existing norms regarding sharing of parental leave between parents. Both may change over time, and this may alter their association with union dynamics. Theoretically and empirically, these interdependent dynamics need to be considered when looking at the relationship between fathers’ use of leave and union dissolution.

Empirical Investigations and Assumptions

According to the theoretical assumptions of the employment-centred and gender-revolution-centred approaches, fathers’ use of parental leave in societies that have progressed beyond the first phase of the gender revolution should strengthen the union and reduce divorce risks. The reasons given for this are manifold and concern primarily the influence that fathers’ use of parental leave has on a more gender-equal sharing of work and care between the partners and their relationship to each other. Although we are not able to investigate these factors with our data, we briefly refer to them in order to link them to our hypotheses. Because our empirical investigation concentrates on Nordic countries, we limit this review to findings from them.

First, studies in these countries reveal differences with respect to fathers’ worktime allocation, the division of care for sick children, and mothers’ earnings, depending on the use of parental leave. Fathers who take parental leave in Sweden reduce their working hours after their leave (Duvander and Jans 2009). Yet, there is only a minor effect of fathers’ use of the reserved part on the division of care for sick children (Duvander and Johansson 2018). Several studies report that parental leave decreases the future earnings of both parents, but the dynamic of mothers’ and fathers’ earnings development differs (Evertssson 2016; Johansson 2010). A Norwegian study finds an incremental negative effect on fathers’ earnings since the introduction of the reserved part of the leave. This is consistent with the increase in fathers’ uptake of parental leave since then (Rege and Solli 2013). In all cases, the loss of income is small so that we may assume that fathers’ use of leave does not expose the couple to financial strains that may increase the risk of union dissolution. On the contrary, since fathers’ use of leave has a positive effect on women’s wages and is also associated with fathers’ engaging more in household work and care, we may assume that fathers’ use of parental leave reduces a couple’s risk of break-up.

Second, the theories also predict that a more gender-equal allocation of domestic duties results in greater couple satisfaction. Studies for Norway confirm this assumption. They report fewer conflicts over the division of household chores even more than a decade after the introduction of the reserved part for fathers (Kotsadam and Finseraas 2011), and a higher relationship quality for women in couples with a more gender-equal sharing of household work (Barstad 2014). A Swedish study corroborates the link between women’s satisfaction with the sharing of household duties and lower union dissolution risks (Ruppanner et al. 2018), while another one finds that men’s satisfaction with the division of parental leave is associated with couple satisfaction and union stability (Brandén et al. 2016).

Third, studies furthermore demonstrate that fathers who take parental leave are more satisfied with their relationship with their children than those who do not (Haas and Hwang 2008). They may also stay more involved with their children later on (Kruk 2010; Duvander and Jans 2009). Having a close relationship to one’s children may make it more difficult for a parent to dissolve a union, even in the Nordic countries where joint custody is norm.

Overall, these studies confirm that fathers’ parental leave use may strengthen intra-family relationships and thus decrease the risk of union dissolution. In the light of these empirical findings and our theoretical considerations regarding fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1

Couples in which the father takes parental leave are at lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which the father does not take leave.

We argued above that whether a longer leave is associated with a lower risk of union dissolution than a shorter leave is a contentious matter. The aim of the policy, namely that fathers take the reserved part, and the fact that this part may be lost if not taken may provide assurance and protection, while longer leaves may need to be negotiated more intensely and may entail greater unease and insecurity, e.g. regarding employment and careers. This may burden and jeopardize a partnership, so that one may conjecture that if the father takes longer leaves than the reserved part, the couple is more at risk of breaking-up.

By contrast, if a gender-equal division of care is regarded as the fair sharing in a society, then a more equal sharing should lower the risk of union dissolution. This assumption is backed by the gender revolution theory which infers that more gender equality in the family strengthens unions. Findings about the long-term implications of fathers’ parental leave, such as a more gender-equal division of work, more relationship satisfaction with fathers’ more intense involvement in care, or the closer father–child connection through fathers’ parental leave (see above) support these claims. Fathers who take more leave than the reserved part may also be more family-oriented and/or they may be more committed to a more equal sharing of family obligations in general. We therefore assume that:

H2

Couples in which the father has taken more parental leave than the reserved part have a lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which the father takes leave only up to the reserved part.

In the Nordic countries, many cohabitants live in long-term relationships and cohabitation has become an accepted way of life not only for childless couples but also for those with children (Lappegård and Noack 2015). Nonetheless, cohabiting couples are a more diverse group than married couples (Hiekel et al. 2014). Besides, cohabitation is generally less stable than marriage, even if the couple has children, and cohabitants are less satisfied with their relationship than married couples (Wiik et al. 2012). In the Nordic countries, many couples marry after the transition to parenthood (Holland 2013; Perelli-Harris et al. 2012). Couples who are married at the time of the first birth might be more traditional than couples who marry later and may thus be more inclined to divide their parental leave in a conventional way. By contrast, cohabitants may be more unconventional and regard a more equal sharing of parental leave as pursuant to their ideals and their lifestyle. Cohabitants may also need to invest more in their relationship to stay together. We argue that greater father’s involvement and a more gender-equal use of parental leave have a stronger protective role among cohabitants than among spouses, and we therefore presume that:

H3

The association between fathers’ length of parental leave and the risk of union dissolution is stronger among cohabiting couples than among married couples.

In our theoretical reflections, we indicated that the effect of fathers’ use of parental leave may change over time. This may be due to how prevalent gender-egalitarian norms were at the time of the policy implementation and how they developed subsequently. It may also be connected to who was eligible or was making use of the policy option at its onset and later on, and it may be linked to policy changes over time. For example, at the time of its introduction Norwegian fathers’ eligibility was tied to the mothers’ eligibility and thus not universal. Duvander and Johansson (2018) show for Sweden that the implementation of the reserved part led to take up by middle and lower educated fathers, so that they caught up with the highly educated who, to some extent, had already made use of the option for leave offered by the gender-neutral parental leave law even before the reserved part was enacted. Duvander and Johansson (2012) find that the introduction of the reserved part had a greater mobilizing effect on fathers than its extension later on. The introduction was long overdue, and many other areas in society had come much further regarding gender equality. This suggests that the risk of union dissolution in the first period after the reserved part was introduced may differ from that in later periods, and we state:

H4

The association between fathers’ use of the parental leave and the risk of union dissolution will diminish with time since the reserved part of the leave was introduced.

Our examples and argumentation suggest that the fathers’ use of parental leave may play out differently in the three countries, due to differences in the time of implementation, in policy regulations, policy discourse, and gender context. Although the three countries have strong norms towards gender equality and fathers’ involvement, there are differences in the consistency of the norms and the pace of the development of the norms. Due to these and to the regulations in the three countries, the proportion of fathers taking parental leave differs across the countries.

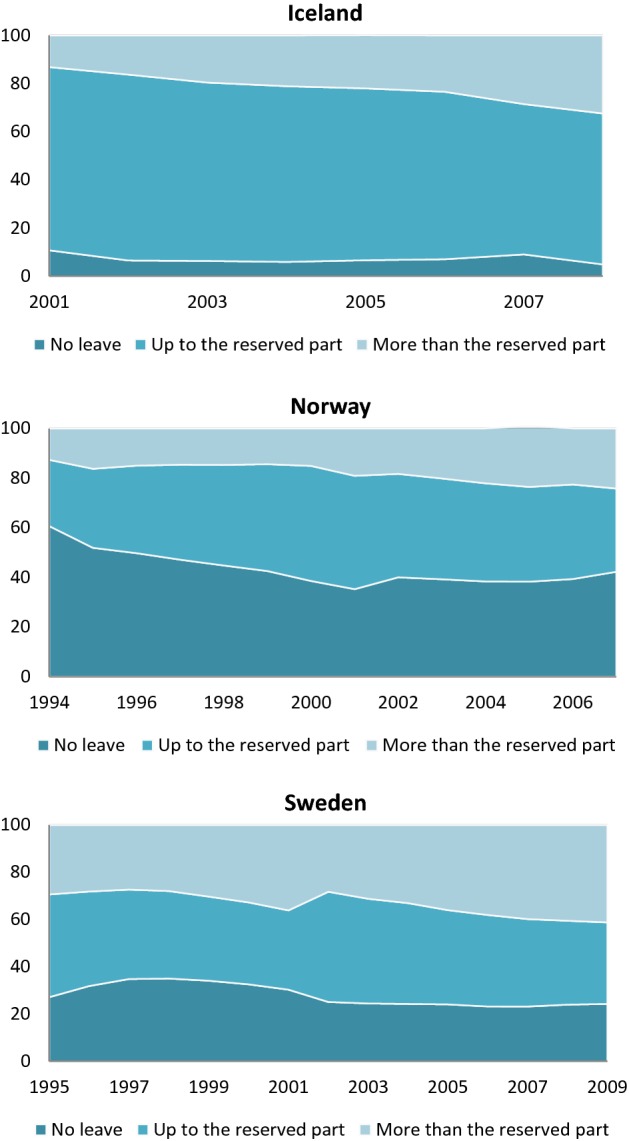

Norway was the first country to reserve part of the leave for one parent. However, a large proportion of fathers did not make use of this option at the beginning, so that family behaviour with regard to sharing of parental leave was initially polarized. In Sweden with its more consistent orientation towards gender equality, a larger share of fathers were using parental leave even before the reserved part was introduced, and expectations about fathers’ taking leave were widely present. The fathers using parental leave were thus less of a select group than in Norway. When Iceland implemented its reserved part, it scored already high on gender equality, e.g. female employment, and fathers immediately embraced the possibility to take parental leave (Arnalds et al. 2011) (Fig. 1). Given the different developments of a reserved part of leave and of gender equality, one may therefore assume that there are differences in the association between fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution in the three countries. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Fig. 1.

Fathers’ use of parental leave by birth year of first child. Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Percent

H5

The association between fathers’ use of parental leave and the risk of union dissolution is weaker in Sweden than in Iceland and Norway.

The Nordic Parental Leave Programme

The paid parental leave systems in Iceland, Norway and Sweden are quite similar with respect to their aims and basic principles, but there are also some distinct differences. The Nordic countries are often described as welfare states that use policies to support a dual-earner–carer family model (Sainsbury 1996; Ferrarini and Duvander 2010; Eydal and Gíslason 2011). The parental leave programme grants parents the right to stay at home with their children after birth without suffering financially or losing their jobs. Parents receive financial compensation during the leave period (see below) and have the legal right to return to their jobs afterwards. Today the total length of parental leave is 49 or 59 weeks in Norway depending on the level of the income compensation; in Sweden, it is 56 weeks with income-related benefit and 12 weeks with a low flat rate, and Iceland has a parental leave of 35 weeks of leave (for a summary of the three policy contexts, see Table 1). In all three countries, for reasons of gender equality (Duvander and Lammi-Taskula 2011), the leave is divided into three parts: one part is reserved for the father, one for the mother, and one may be shared between the parents as they wish (for detailed description of the leave policies and its development, see annual updates at leavenetwork.org).

Table 1.

Overview of the policy context in Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

Source: Eydal and Gíslason (2008), Cedstrand (2011), Brandth and Kvande (2017); www.leavenetwork.org

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental leave | |||

| Introduced | 1981 | 1978 | 1974 |

| Current length/rate of income compensation | 35 weeks/75% compensation | 49 weeks/100% compensation or | 56 weeks/80% compensation and |

| 59 weeks/80% compensation | 12 weeks/low flat rate | ||

| Reserved part to fathers | |||

| Introduction/changes | 2001: 4 weeks | 1993: 4 weeks | 1995: 4 weeks |

| 2002: 8 weeks | 2005: 5 weeks | 2002: 8 weeks | |

| 2003: 12 weeks | 2006: 6 weeks | 2016: 12 weeks | |

| 2009: 10 weeks | |||

| 2011: 12 weeks | |||

| 2013: 14 weeks | |||

| 2014: 10 weeks | |||

| 2018: 15 weeks | |||

Changes not included in the study period marked in italic

The issue of reserving a part of the leave for fathers was debated in Sweden in the 1970s already (Cedstrand 2011), but was not implemented until 1995. At the time of implementation, the reserved part in Sweden was 4 weeks; it was extended to 8 weeks in 2002 and 12 weeks in 2016. The reserved part in Norway was introduced in 1993, and as in Sweden, it was 4 weeks when initially implemented. From 2005, it was extended incrementally, first to 5 weeks in 2005, then to 6 weeks in 2006, 10 weeks in 2009, 12 weeks in 2011 and 14 weeks in 2013. After a change of government, the reserved part was reduced to 10 weeks in 2014, but extended to 15 weeks in 2018. In Iceland, the reserved part was introduced in 4-week increments over a 3-year period (2001–2003) up to the current 12 weeks and was divided into three equal parts from the beginning. The radical policy of 3 months reserved for each parent made Iceland the leading country as regards gender equality (Eydal and Gíslason 2011; Arnalds et al. 2011).

There is extensive variation in fathers’ use of parental leave (see Fig. 1) across the countries. The general tendency in all countries is that more fathers are taking leave and that they are taking longer leaves. Iceland still has the largest proportion of fathers taking leave, Norway the largest proportion of fathers not taking leave, and Sweden the largest proportion of fathers taking more than the reserved part.

Income compensation is around 80% of a parent’s previous income, up to a relatively high earnings ceiling in all three countries. In Norway, parents have the option to receive 100% income compensation, if they choose the shorter, 49 weeks of leave. This is the preferred option among parents in Norway. For earnings above the ceiling, there are often collective agreements supplementing the benefit with extra payment to compensate, partly or wholly, for any loss of income. In Iceland, income compensation was reduced to 75% for parents with income above a fixed ceiling in 2010, in response to the financial crisis. The ceiling had already been lowered in 2009 to an amount well below the mean monthly regular salary for men in that same year, which resulted in fathers taking less leave (Eydal and Gíslason 2014).

Fathers’ eligibility for parental leave varies somewhat across the three countries. In both Sweden and Iceland, all parents are included in the parental leave programme. Parents with no earnings prior to their leave receive a low flat rate benefit. In Norway, eligibility for parental leave benefit is dependent on employment prior to childbirth. Until 2000, the father’s eligibility for parental leave benefit in Norway was also dependent on the mother’s employment prior to childbirth, but after that, fathers gained an individual right to parental leave, except for the reserved part of the leave, which is still dependent on the mother’s employment. In Norway, mothers who are not entitled to income-related leave benefit receive a lump-sum, tax-free cash payment on the birth of the child (Brandth and Kvande 2017).

The parental leave programme in all countries is flexible to allow parents to arrange it according to their care and employment needs. A parent does not need to take all the leave at once, but may alternate with the other parent or parents may even divide the week between them. In Sweden and Iceland, parents may also combine paid and unpaid days of leave and take half-day leave. This flexibility is widely used by parents (Duvander and Viklund 2014) and results in great variation in total leave length. Unlike in Norway and Sweden, parents in Iceland have the opportunity to take leave at the same time and this option is often used (Arnalds et al. 2011).

Data and Methods

We use data from the national population registers that cover the whole population. Each resident has a unique identification number. This allows us to link data from different administrative registers, and we construct data sets that contain longitudinal information on union status. The data cover almost 20 years and include the period 1993–2011. Most importantly, we have information on the use of parental leave, and we focus on the period in which there has been a reserved part of the parental leave for fathers in each country. This means that the period observed is shorter in Iceland than in Norway and Sweden. The samples contain cohabiting and married couples who have their first child together. We have excluded couples with children born abroad and couples with multiple births from the sample.

We make use of a discrete-time hazard model in which we estimate the association between fathers’ use of parental leave and the risk of parents dissolving their union. The estimated risk reflects both the timing and the quantum of the event we study. We start following couples when they have their first child together, and we only consider parental leave taken for the first child. The couples may have additional children during the exposure time, but we do not consider the use of parental leave for these children because it will create endogeneity problems. In general, there is a similar pattern in the use of parental leave but first-child parents share somewhat more equally than higher-parity parents (Sundström and Duvander 2002; Lappegård 2010). Although there is a possibility that some couples may change their use of parental leave between parities, we consider the use of leave in connection with the first birth to be a good proxy for fathers’ involvement in general.

We start the clock at t3, where t1 is defined as the year of birth of the couple’s first common child. Couples are followed until the union dissolves, t12 or 2011 (2012 in Sweden) whatever comes first. We also stop following the couples if one of the parents dies or moves abroad. The reason for starting at t3 is the manner in which union status is defined. We have annual information about union status, which means that if there is a change in union status from 1 year to the next year, we do not know at what point during the year the change has occurred. There may also be a lag in the registration of people’s residential addresses, which means that some cohabiting couples are not officially registered as cohabiting until the year after the child is born. In order to have the most accurate information about union status at the time of the birth, we use the year after the birth (t2) for measuring the union status. This means that we miss any union dissolution that occurs during the first year after the child is born, which is less than 5%.

The use of parental leave by fathers is our main explanatory variable. We distinguish between three groups of users: fathers who take no leave, fathers who take leave but not more than the reserved part and fathers who take more than the reserved part. Note that the reserved part changed over time in all countries (see Table 1), and this implies that both the “reserved part” and “more than the reserved part” changed accordingly. To make sure we capture the major part of the use of parental leave when the child still needs much care, we measure the use of the leave up to 18 months after the child is born. This time window is especially important for Sweden, which has the longest leave period; in order to maintain a comparative design, we choose this time window for all three countries. We only include the parents of children born between January and June. Since leave is measured until the child turns 18 months, we only include the parents of children born between January and June of t1, with the clock for observing union dissolution subsequently starting t3. We do this to avoid endogeneity, as including parents of children born between July and December of t1 would also imply measuring use of parental leave until the first semester of t3, which is after we started the clock.

The couples may have additional children during the exposure time, and the number of children is included as a time-varying variable. We control for the ages of the parents, whether the parents were born abroad, union status at first birth (cohabiting or married at t2), education (measured the year before the first birth), and time period in which the first birth occurs. The time period of the first birth differs somewhat across countries, and the first period includes the year when the reserved part of the leave was introduced in each country. Although some cohabitants may marry after they have their first child, we only consider whether there are differences between couples cohabiting or married at the time they had their first child. Unfortunately, as we do not have information about duration of partnerships among cohabitors before the first birth, we do not control of duration of partnerships in our models. For descriptive statistics of all variables included in the analysis, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables included in analysis

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Union dissolutions | |||

| Yes | 9.5 | 18.7 | 13.2 |

| No | 90.5 | 81.3 | 86.8 |

| Fathers’ use of parental leave | |||

| Not used | 6.7 | 44.5 | 27.3 |

| Up to the reserved part | 73.4 | 37.8 | 39.8 |

| More than the reserved part | 19.9 | 17.7 | 32.9 |

| Union status at first birth | |||

| Cohabiting | 65.2 | 50.3 | 59.3 |

| Married | 34.8 | 49.7 | 40.7 |

| Time period at first birth | |||

| 1994–1997a | 36.5 | 24.3 | |

| 1998–2000 | 25.4 | 22.9 | |

| 2001–2004 | 65.9 | 35.6 | 30.1 |

| 2005–2009b | 34.1 | 12.5 | 22.7 |

| Mother’s education | |||

| Low | 12.8 | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Medium | 23.4 | 48.9 | 53.1 |

| High | 57.2 | 42.7 | 37.3 |

| Missing | 6.6 | 3.5 | 2.9 |

| Father’s education | |||

| Low | 14.9 | 6.5 | 9.1 |

| Medium | 30.9 | 57.6 | 61.5 |

| High | 41.0 | 33.7 | 27.0 |

| Missing | 13.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Immigrant background | |||

| Neither parent born abroad | 87.6 | 83.1 | 78.7 |

| Father born abroad | 2.8 | 4.7 | 5.8 |

| Mother born abroad | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| Both born abroad | 3.6 | 6.2 | 9.5 |

| Mother’s age (mean) | 27.2 | 28.1 | 28.1 |

| Father’s age (mean) | 29.9 | 31.1 | 30.4 |

| Number of children (continuous) | |||

| 1 | 16.2 | 25.1 | 24.3 |

| 2 | 63.4 | 58.9 | 63.6 |

| 3 + | 20.4 | 16.1 | 12.1 |

| Number of observations (person-year exposure) | 19,085 | 919,348 | 1,476,611 |

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Percent (numbers correspond to exposure time)

a1995 for Sweden

b2007 for Norway

Results

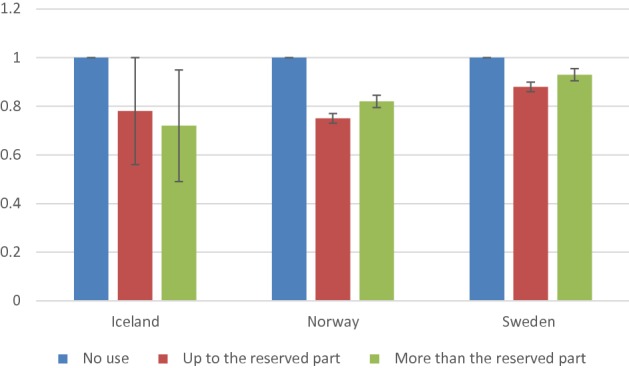

Table 3 shows the risks of union dissolution for couples with at least one child in Iceland, Norway and Sweden. We are primarily interested in the connection with fathers’ use of parental leave (see Fig. 2). The overall picture is similar in all countries: couples in which the father has taken any parental leave have a lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which the father has not taken leave. This supports hypothesis 1 and confirms our theoretical expectation that early father involvement is positively associated with union stability. In our second hypothesis, we assume a linear relationship between fathers’ duration of parental leave and union dissolution, namely that parents who share parental leave more equally are less likely to dissolve their union. This is not supported, as there are country differences in the fathers’ use of leave and the risk to dissolve the union. In Iceland, we find a linear relationship between the length of the father’s leave and union dissolution, although the estimate for fathers who take maximally the reserved part is not significant. In other words, couples in which the father takes more than the reserved part have the lowest risk of union dissolution in Iceland. This is not the case in Norway and Sweden. There, we observe the lowest risk of break-up among couples in which the father has taken no more than the reserved part. The difference in dissolution intensity between policy-conforming and gender-egalitarian fathers seems to be somewhat stronger in Norway than in Sweden. In Sweden, the difference between the two groups is significant, but the confidence interval for the two groups is very close.

Table 3.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | |

| Fathers’ use of parental leave | ||||||

| Not used | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Up to the reserved part | 0.78 | 0.59–1.02 | 0.75** | 0.73–0.77 | 0.88** | 0.86–0.90 |

| More than the reserved part | 0.72* | 0.52–0.99 | 0.82** | 0.80–0.85 | 0.93** | 0.91–0.96 |

| Union status at first birth | ||||||

| Cohabiting | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Married | 0.74* | 0.60–0.91 | 0.41** | 0.40–0.42 | 0.73** | 0.72–0.75 |

| Time period at first birth | ||||||

| 1994–1997a | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1998–2000 | 1.23** | 1.20–1.27 | 1.04** | 1.02–1.07 | ||

| 2001–2004 | 1 | 1.46** | 1.42–1.51 | 0.91** | 0.89–0.93 | |

| 2005–2009b | 0.76* | 0.63–0.91 | 2.37** | 2.29–2.44 | 0.89** | 0.87–0.91 |

| Mother’s education | ||||||

| Low | 0.98 | 0.78–1.24 | 1.18** | 1.13–1.23 | 1.46** | 1.42–1.50 |

| Medium | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 0.73* | 0.59–0.89 | 0.92** | 0.89–0.94 | 0.77** | 0.76–0.79 |

| Father’s education | ||||||

| Low | 1.17 | 0.94–1.46 | 1.22** | 1.17–1.26 | 1.27** | 1.23–1.30 |

| Medium | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| High | 0.80* | 0.64–0.99 | 0.89** | 0.87–0.92 | 0.92** | 0.89–0.94 |

| Immigrant background | ||||||

| Neither parent born abroad | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Father born abroad | 1.60* | 0.07–2.38 | 1.32** | 1.25–1.38 | 1.61** | 1.56–1.66 |

| Mother born abroad | 1.04 | 0.71–1.53 | 1.13** | 1.08–1.19 | 1.33** | 1.29–1.38 |

| Both born abroad | 0.90 | 0.58–1.41 | 0.81** | 0.77–0.86 | 1.28** | 1.24–1.32 |

| Mothers age | 0.79* | 0.67–0.94 | 0.83** | 0.81–0.85 | 0.85** | 0.83–0.86 |

| Mothers age sq | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00** | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00** | 1.00–1.00 |

| Fathers age | 0.88* | 0.79–0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.92** | 0.91–0.93 |

| Fathers age sq | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00** | 1.00–1.00 |

| Number of children (continuous) | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 0.27** | 0.22–0.32 | 0.42** | 0.41–0.43 | 0.43** | 0.43–0.44 |

| 3 + | 0.17** | 0.12–0.23 | 0.28** | 0.27–0.29 | 0.31** | 0.30–0.32 |

| Log likelihood | − 2324.16 | − 147,504.38 | − 202,146.72 | |||

| Number of observations (person-year exposure) | 19,085 | 919,348 | 1,476,611 | |||

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Odds ratio

**0.001; *0.05

a1995 for Sweden

b2007 for Norway

Fig. 2.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child. Iceland (2001–2009), Norway (1994–2007) and Sweden (1995–2009). Odds ratio. Note Estimates from Table 3

Before we continue with the other hypotheses, we briefly comment on the control variables included in the model (see Table 3). In all countries, married couples have a lower risk of union dissolution than cohabitants. The difference seems significantly larger in Norway than in Iceland and Sweden. In addition, in all countries the risk of union dissolution decreases with both the mother’s and the father’s level of education, their age, and the number of children. The risk of union dissolution increases if one of the parents is born abroad, especially if the father is born abroad. The pattern is similar in all three countries. For the time period of the first birth, we find a different pattern in the risk of union dissolution in the three countries. In Iceland, the risk of union dissolution is lower in the period 2005–2009 than in the period 2001–2004. In Norway, the risk of union dissolution increases over time, while in Sweden, it first increases slightly and then decreases slightly. As a sensitivity test, we ran the model without including the number of children, as other studies have found an association between fathers’ use of parental leave and having more than one child (Duvander et al. 2010; Lappegård 2010). The general pattern remains the same when the number of children is not included (numbers not shown).

Our third hypothesis predicts a stronger association between fathers’ use of parental leave and the risk of union dissolution among cohabiting couples than among married couples. To investigate this, we included an interaction between fathers’ use of parental leave and union status. A likelihood ratio test shows a significantly improvement of the model including the interaction over the model not including the interaction in Norway (LR χ2(2) = 84.28) and Sweden (LR χ2(2) = 49.18), but not in Iceland (LR χ2(2) = 3.40). Table 4 shows computed odds ratios for the risk of union dissolution. The hypothesis is partly supported: in Iceland and Sweden, there are more differences in dissolution risks among the three groups of cohabiting couples than among married couples, while the pattern is more similar among cohabitants and married couples in Norway. More specifically, in Iceland, there is no significant difference between married couples in which the father takes more than the reserved part, and those in which the father does not take leave (see Table 6). The estimate for married couples in which the father uses up to the reserved part is significant, but the difference to couples in which the father uses no leave is small (odds ratio of 0.98). Among cohabitants, there is a clear pattern that couples in which the father has taken leave (either up to or more than the reserved part) have a lower risk of union dissolution compared to couples where the father has not taken any leave. However, there is no significant difference between the two groups in which the father uses leave. In Sweden there is hardly any difference among married couples, while there is a significant difference among cohabitants; couples in which the father has taken leave up to the reserved part have a lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which he has taken more than the reserved part. In Norway, the pattern is similar for cohabitants and married couples. It is the same as the general pattern when all couples are considered together: fathers’ use of parental leave is associated with a lower risk of union dissolution, and couples in which the father has used up to the reserved part of the leave have the lowest risk to dissolve the union.

Table 4.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohabitants | Married | Cohabitants | Married | Cohabitants | Married | |

| Not used | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Up to the reserved part | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.97 |

| More than the reserved part | 0.61 | 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 1.01 |

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Computed odds ratios. Fathers’ use of parental leave and union status

Controlled for: time period, mother’s/father’s age, education and immigrant background, and number of children. Computed odds ratios is based on estimates from Table 6

Table 6.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | |

| Fathers’ use of parental leave * union status at first birth | ||||||

| Not used * cohabiting | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Up to the reserved part * cohabiting | 0.72* | 0.53–0.98 | 0.79** | 0.77–0.81 | 0.84** | 0.82–0.86 |

| More than the reserved part * cohabiting | 0.61* | 0.43–0.88 | 0.87** | 0.84–0.90 | 0.89** | 0.87–0.92 |

| Not used * married | 0.53* | 0.29–0.96 | 0.45** | 0.44–0.47 | 0.67** | 0.64–0.69 |

| Up to the reserved part * married | 0.52* | 0.36–0.74 | 0.29** | 0.27–0.30 | 0.65** | 0.63–0.67 |

| More than the reserved part * married | 0.62 | 0.39–1.01 | 0.32** | 0.30–0.33 | 0.68** | 0.66–0.70 |

| Log likelihood | − 2322.46 | − 147,462.24 | − 202,122.13 | |||

| Number of observations (person-year exposure) | 19,085 | 919,348 | 1,476,611 | |||

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Odds ratio. Including interaction between fathers’ use of parental leave and union status

**0.001; *0.05; Same model as Table 3

Our fourth hypothesis predicts the association between fathers’ use of the parental leave and the risk of union dissolution to diminish with time since the reserved part of the leave to father’s was introduced. To investigate this, we included an interaction between fathers’ use of parental leave and the period of first birth on the risk of union dissolution. A likelihood ratio test shows that the model including the interaction improves significantly compared to the model not including the interaction in Norway (LR χ2(6) = 121.26) and Sweden (LR χ2(6) = 30.08), but not in Iceland (LR χ2(2) = 1.38). Table 5 shows the computed odds ratios for the risk of union dissolution by fathers’ use of parental leave and the time period. The hypothesis is not supported as the general finding is consistent over time in each country: couples in which fathers use parental leave are less likely to dissolve their union. However, the pattern for how different use of leave plays out over time in each country differs. In Iceland, we only distinguish between two time periods, 2001–2004 and 2005–2009, and there are few significant estimates. There are no significant differences in the risk of union dissolution in the first period when the reserved part was available to fathers in Iceland, but in the second period there were. This implies that both couples in which the father uses up to the reserved part or couples in which he uses more have a lower risk of ending their union than couples in which fathers did not take any leave. However, there is no significant difference between the two groups of couples in which the father takes parental leave. In both Norway and Sweden, there is a significant difference in all periods observed between couples in which the father does not take any leave and couples in which the father does take leave. In Norway, there are significant differences between couples in which the father takes the reserved part and couples in which the father takes more than the reserved part in the first two periods or until 2000. Here the pattern is the same as the overall pattern, i.e. couples in which the father takes up to the reserved part have the lowest risk of union dissolution. Interestingly, this pattern changes, and from 2001 onwards there is no longer a significant difference. In Sweden, there are no significant differences in any periods between couples in which fathers take up to the reserved part and couples in which fathers take more than the reserved part.

Table 5.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994–1997 | 1998–2000 | 2001–2004 | 2005–2009 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2000 | 2001–2004 | 2005–2009 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2000 | 2001–2004 | 2005–2009 | |

| Not used | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Up to the reserved part | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.84 | ||

| More than the reserved part | 0.83 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.84 | ||

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Computed odds ratios. Fathers’ use of parental leave and time period

Controlled for: union status at first birth, mother’s/father’s age, education, immigrant background, and number of children. Computed odds ratio is based on estimates from Table 7

Our last and fifth hypothesis predicts that the association between fathers’ use of parental leave and the risk of union dissolution is weaker in Sweden than in Iceland and Norway. This is partly supported. The general pattern is the same in Sweden as in Iceland and Norway, couples in which fathers use parental leave have a lower risk of union dissolution than couples in which they do not use any leave. Although we should be careful in comparing the magnitude of the estimates across the country models, the differences between the two groups are somewhat smaller in Sweden. Also, in Sweden the difference between the couples in which the father uses leave is smallest.

Discussion

This study investigates the relationship between gender behaviour and union stability in three countries, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, which are recognized as forerunners in gender equality. To achieve gender and social equality in all spheres of life has been an explicit policy goal in the Nordic countries. Although the Nordic countries have moved further ahead in the process towards greater gender equality, it is still a long way off until men and women contribute equally to unpaid domestic responsibilities. To promote a more equal sharing of family work, the Nordic countries we investigate have reserved part of the parental leave for one parent that may not be used by the other parent. This policy addressed especially fathers. Our study explores the relationship between fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution—and asks whether there is a difference in break-up risks between couples in which the father takes no leave, couples in which the father takes only the reserved part and couples in which the father takes more than the reserved part. We thus aim to elicit differences or commonalities in union dissolution between those who conform to the policy norm regarding fathers’ leave and those who follow more gender-egalitarian norms.

Our study starts from the most common theories in demography about the relationship between changing gender behaviour and union stability. These theories have shifted their focus over time from women’s employment to men’s contribution to family work. The view turned from regarding female employment as reducing the gains from marriage and increasing divorce risks (Becker 1981) to more gender-equal sharing of family responsibilities, resulting in greater couple satisfaction, closer fatherly ties to children and lower risk of union dissolution (Goldscheider et al. 2015). We add a new theoretical dimension to these approaches by highlighting the role that policies play as normative and factual guidelines. We argue that the reserved part of parental leave sets a norm for expected behaviour. Taking no leave or taking more than the reserved share deviates from such a policy norm and may have different consequences for union dissolution. In the case of the Nordic countries, the policy-induced norm of taking the reserved month(s) of parental leave needs to be viewed in the light of the overarching political aim to achieve gender equality and thus to share family work gender equally. We distinguish between fathers who take no leave, those who take only the reserved share of the leave and those who take more than that. Our study is thus also a study on the links between different normative behaviours of fathers and union dissolution, namely “non-conforming behaviour”, “policy-norm behaviour” and “gender-equal behaviour”.

Our main theoretical prediction that couples in which the father uses parental leave have lower risk of union dissolution finds support in all three countries (Table 3). The pattern holds for all time periods and for married as well as for cohabiting couples, as shown in the interaction models (Tables 4, 5). Resorting to findings from other investigations, we attribute the negative association between fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution risk to two factors. On the one hand, equal sharing of family obligations may lead to greater couple satisfaction and thus lessen the risk of union dissolution. On the other hand, more investment in children by the father may lead to stronger family ties and thus create stronger barriers against the break-up of the relationship. Our results also support the gender revolution theory, which predicts that unions become more stable if men engage more actively in family work (Goldscheider et al. 2015). They furthermore support the more employment-focused arguments that increasing union dissolution in dual-earner societies can be seen as a response to men’s lack of involvement in the home (Cooke 2006).

The theoretical assumptions about the relationship between gender equality and union dissolution commonly infer that the more gender equal a couple divides family work, the less likely it is to break up. Our results show that this does not hold. Except for Iceland (non-significant result), it is the couples in which the father takes only the reserved parental leave that have the lowest risk of union dissolution. This implies that the more “policy conform” the father’s behaviour, the less likely the couple is to break up. To some extent, this is corroborated by the results for cohabiting and married couples as well as the development of union dissolution and fathers’ policy-conforming versus gender-egalitarian uptake of parental leave over time. In neither case do we find that a more gender-equal sharing of parental leave lowers the risk of union dissolution significantly.

It is important to underline that our findings cannot distinguish selection effects from causality. Moreover, especially regarding differences in the country results, one needs to keep in mind that the three countries introduced their policies at different times and that family dynamics, parental leave policies, fathers’ uptake of parental leave, and the move towards gender equality developed differently in the three countries over time (see, e.g. Table 1; Fig. 1). Given these and other differences, e.g. in economic development, our common results for all countries are even more noteworthy. The differences in union dissolution risks between couples in which the father takes no leave and couples in which the father takes leave emphasize that early father’s involvement is positively associated with union stability. Active participation in child-rearing seems to have become a desired activity and a shared norm in the Nordic countries, and abstaining from taking leave for whatever reasons is correlated with a higher risk of union dissolution.

We do not find support for asserting that the most gender-equal couples in terms of fathers taking more than the reserved part are the most stable unions, as the pattern is not uniform in the three countries or over time. Thus, our results indicate that the theoretical assumptions that greater gender equality within the family will result in more stable unions (Breen and Cooke 2005; Goldscheider et al. 2015) needs to be more nuanced. This does not imply that we should shed the goal of gender equality. On the contrary, gender equality within the family in the Nordic countries is still an ongoing process, and the relationship between gender behaviour and union stability is still in flux. Our results indicate that at this stage, policies that are set up to promote gender equality in the family may, with time and when accepted, also contribute to union stability.

Appendix

Table 7.

Risk of union dissolution for couples with at least one child

| Iceland | Norway | Sweden | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | |

| Fathers use of parental leave * time period at first birth | ||||||

| Not used * 1994–1997 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Up to the reserved part * 1994–1997 | 0.64** | 0.61–0.66 | 0.86** | 0.83–0.90 | ||

| More than the reserved part * 1994–1997 | 0.78** | 0.74–0.83 | 0.95* | 0.90–0.99 | ||

| Not used * 1998–2000 | 1.19** | 1.15–1.23 | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | ||

| Up to the reserved part * 1998–2000 | 0.87** | 0.83–0.90 | 0.92** | 0.88–0.96 | ||

| More than the reserved part * 1998–2000 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | ||

| Not used * 2001–2004 | 1 | 1.36** | 1.31–1.41 | 0.88** | 0.85–0.92 | |

| Up to the reserved part * 2001–2004 | 0.81 | 0.58–1.14 | 1.09** | 1.04–1.13 | 0.81** | 0.78–0.84 |

| More than the reserved part * 2001–2004 | 0.83 | 0.55–1.25 | 1.15** | 1.09–1.22 | 0.86** | 0.82–0.89 |

| Not used * 2005–2009 | 0.88 | 0.52–1.48 | 2.09** | 2.01–2.18 | 0.93* | 0.89–0.98 |

| Up to the reserved part * 2005–2009 | 0.63* | 0.44–0.91 | 1.90** | 1.82–2.00 | 0.78** | 0.75–0.82 |

| More than the reserved part * 2005–2009 | 0.52* | 0.34–0.79 | 1.85** | 1.75–1.95 | 0.78** | 0.75–0.82 |

| Log likelihood | − 2323.47 | − 147,443.75 | − 202,131.68 | |||

| Number of observations (person-year exposure) | 19,085 | 919,348 | 1,476,611 | |||

Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Odds ratio. Including interaction between fathers’ use of parental leave and time period

**0.001; *0.05; same model as Table 3

Funding

This work is part of the Project “Nordic Family Policy and Demographic Consequences (NORDiC)” supported by the Research Council of Norway (217915/F10). Additionally, Gerda Neyer acknowledges additional funding from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) via the Linnaeus Center on Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe (SPaDE) (Grant 349-2007-8701); Gerda Neyer and Ann-Zofie Duvander from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under Grant Agreement No. 320116 for the research project Families And Societies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arnalds A, Eydal GB, Gíslason IV. Equal rights to paid parental leave and caring father: The case of Iceland. Stjórnmál & Stjórnsýsla. 2011;1:34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barstad A. Equality is bliss? Relationship quality and the gender division of household labour. Journal of Family Issues. 2014;35(7):972–992. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14522246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A treatise on the family. London: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics. 1985;3(2):S33–S58. doi: 10.1086/298075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandén M, Duvander A-Z, Ohlsson-Wijk S. Sharing the caring: Attitude–behaviour discrepancies and partnership dynamics. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography. 2016;2016:17. [Google Scholar]

- Brandth, B., & Kvande, E. (2017). Country report: Norway. International network on Leave Policies & Research. http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/country_reports/. Accessed 1 July 2018.

- Breen R, Cooke LP. The persistence of the gendered division of domestic labour. European Sociological Review. 2005;21:43–57. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cedstrand, S. (2011). Från idé till politisk verklighet. Föräldrapolitiken i Sverige och Danmark [From idea to political reality. Parental politics in Sweden and Denmark]. Doctoral Dissertation, School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg.

- Cooke LP. ‘Doing’ gender in context: Household bargaining and risk of divorce in Germany and the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;112:442–472. doi: 10.1086/506417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LP, Erola J, Evertsson M, Gähler M, Härkönen J, Hewitt B, Jalovaara M, Kan M-Y, Lyngstad TH, Mencarini L, Mignot J-F, Mortelmans D, Poortman M, Schmitt C, Trappe H. Labour and love: Wives’ employment and divorce risk in its socio-political context. Social Politics. 2013;4:482–509. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxt016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl GB, Løken KV, Mogstad M. Peer effects in programme participation. American Economic Review. 2014;104(7):2049–2074. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.7.2049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Jans A-K. Consequences of fathers’ use of parental leave: Evidence from Sweden. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research. 2009;2009:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Johansson M. What are the effects of reforms promoting fathers’ use of parental leave? Journal of European Social Policy. 2012;22:319–330. doi: 10.1177/0958928712440201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Johansson M. Does fathers’ care spill over? Evaluating reforms in Swedish parental leave program. Feminist Economics. 2018 doi: 10.1080/13545701.2018.1474240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Lammi-Taskula J. Parental leave. In: Gislason IV, Eydal GB, editors. Parental leave, childcare and gender equality in the Nordic countries (Tema Nord 2011:562) Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers; 2011. pp. 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Lappegård T, Andersson G. Family policy and fertility: Fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy. 2010;20(1):45–57. doi: 10.1177/0958928709352541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duvander A-Z, Viklund I. Kvinnors och mäns föräldraledighet. [Women’s and men’s parental leave] In: Boye K, Nermo M, editors. Lönsamt arbete—Familjeansvarets fördelning och konsekvenser. [Gainful work—Division and consequences of family responsibilities] (SOU 2014:28) Stockholm: Fritzes; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evertssson M. Parental leave and careers: Women’s and men’s wages after parental leave in Sweden. Advances in Life Course Research. 2016;29:26–40. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eydal GB, Gíslason IV. Paid parental leave in Iceland—History and context. In: Eydal GB, Gíslason IV, editors. Equal rights to earn and car—Parental leave in Iceland. Reykjavik: Félagsvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands; 2008. pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Eydal GB, Gíslason IV. Parental leave, childcare and gender equality in the Nordic countries (Tema Nord 2011:562) Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eydal GB, Gíslason IV. Hrunið og fæðingaorlof Áhrif á foreldra og löggjöf [The financial crash and parental leave: The effect on parents and the law] Íslenska þjóðfélagið. 2014;5(2):77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini T, Duvander A-Z. Earner–carer model at the crossroads: Reforms and outcomes of Sweden’s family policy in a comparative perspective. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40(3):373–398. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.3.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Bernhardt E, Lappegård T. The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behaviour. Population and Development Review. 2015;41(2):207–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas L, Hwang P. The impact of taking parental leave on fathers’ participation in childcare and relationships with children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work & Family. 2008;11(1):85–104. doi: 10.1080/13668800701785346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiekel N, Liefbroer AC, Poortman A-R. Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population. 2014;30(4):391–410. doi: 10.1007/s10680-014-9321-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. Love, marriage and the baby carriage? Marriage timing and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research. 2013;29(11):275–306. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E.-A. (2010). The effect of own and spousal parental leave on earnings. Working paper 2010:4. Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation.

- Kotsadam A, Finseraas H. The state intervenes in the battle of the sexes: Causal effects of paternity leave. Social Science Research. 2011;40:1611–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk E. Parental and social institutional responsibilities to children’s needs in the divorce transition: Fathers’ Perspective. The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2010;18(2):159–178. doi: 10.3149/jms.1802.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård T. Family policies and fertility in Norway. European Journal of Population. 2010;26:99–116. doi: 10.1007/s10680-009-9190-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård T, Noack T. The link between parenthood and partnership in contemporary Norway. Findings from focus group research. Demographic Research. 2015;32(9):287–310. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oláh LS. Gender and family stability: Dissolution of the first parental union in Sweden and Hungary. Demographic Research. 2001;4:27–96. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2001.4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20:293–343. doi: 10.2307/2137521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women’s employment and the gain of marriage: The specialization and trading model. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:431–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B, Kreyenfeld M, Sigle-Rushton W, Keizer R, Lappegård T, Jasilioniene A, Berghammer C, Di Giulio P. Changes in union status during the transition to parenthood: An examination of 11 European countries. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. 2012;66(2):167–182. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.673004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rege M, Solli IF. The impact of paternity leave on fathers’ future earnings. Demography. 2013;50:2255–2277. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppanner L, Brandén M, Turunen J. Does unequal housework lead to divorce? Evidence from Sweden. Sociology. 2018;52(1):75–94. doi: 10.1177/0038038516674664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury D. Gender equality and welfare states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sigle-Rushton W. Men’s unpaid work and divorce: Reassessing specialization and trade in British families. Feminist Economics. 2010;16:1–26. doi: 10.1080/13545700903448801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundström M, Duvander A-Z. Gender division of childcare and the sharing of parental leave among new parents in Sweden. European Sociological Review. 2002;18(4):433–447. doi: 10.1093/esr/18.4.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiik KA, Keizer R, Lappegård T. Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:389–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00967.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]