Abstract

Guillardia theta anion channelrhodopsin 1 is a light-gated anion channel widely used as an optogenetic inhibitory tool. Our recently published crystal structure of its dark (closed) state revealed that the photoactive retinylidene chromophore is located midmembrane in a full-length intramolecular tunnel through the protein, the radius of which is less than that of a chloride ion. Here we show that acidic (glutamate) substitutions for residues within the inner half-tunnel enhance the fast channel closing and, for residues within the outer half-tunnel, enhance the slow channel closing. The magnitude of these effects was proportional to the distance of the mutated residue from the photoactive site. These data indicate that the local electrical field across the photoactive site controls fast and slow channel closing, involving outward and inward charge displacements. In the purified mutant proteins, we observed corresponding opposite changes in kinetics of the M photocycle intermediate. A correlation between fast closing and M rise and slow closing and M decay observed in the mutants suggests that the Schiff base proton is one of the displaced charges. Opposite signs of the effects indicate that deprotonation and reprotonation of the Schiff base take place on the same (outer) side of the membrane and explains opposite rectification of fast and slow channel closing. Оur comprehensive protein-wide acidic residue substitution screen shows that only mutations of the residues located in the intramolecular tunnel confer strong rectification, which confirms the prediction that the tunnel expands upon photoexcitation to form the anion pathway.

Significance

GtACR1 is a recently discovered photoactivated anion channel that is the most potent optogenetic tool available to silence neurons with light. Our findings here reveal a key property of its molecular mechanism, namely that charge transfers entailing proton transfers between the retinylidene Schiff base chromophore and the apoprotein within the photoactive site modulate fast and slow channel closing of the channel. Our results explain the rectification pattern in GtACR1 and its mutants, as well as confirm our hypothesis, that the full-length intramolecular tunnel that we recently identified defines the anion-conducting path upon photoactivation. These fundamental findings impact future research on ACRs as well as anion conductance in other systems and facilitate tailoring ACRs to expand their optogenetic applications.

Introduction

Anion channelrhodopsins from the cryptophyte alga Guillardia theta anion channelrhodopsins (GtACRs) are the most potent optogenetic inhibitors of neuronal firing and regulators of animal behavior currently available (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). The unitary conductance of GtACRs estimated by noise analysis is ∼20-fold higher than that of cation-conducting ChR2 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (1). Recently we obtained a high-resolution X-ray structure of the dark (closed) state of G. theta anion channelrhodopsin 1 (GtACR1), which exhibits a narrow continuous intramolecular tunnel (7), in contrast to available structures of cation channelrhodopsins (CCRs) from green algae, in which only unconnected cavities were found (8, 9, 10). However, no open-channel GtACR1 structure is yet available, and many questions regarding its gating mechanisms remain unanswered.

Deconvolution of single-turnover GtACR1 photocurrents evoked by nanosecond-laser flashes revealed two kinetic components (11). The fast current decay component accelerated, and its contribution to the overall amplitude increased upon depolarization of the membrane, i.e., showed outward rectification when tested with nearly symmetrical concentrations of the permeant ion species on the two sides of the membrane (11). In contrast, the slow decay component became even slower upon depolarization, and its contribution showed inward rectification. The opposite directions of rectification of the fast and slow current decay components when combined produce the virtually linear voltage dependence of the peak GtACR1 photocurrent (1).

To gain further insight into the mechanism of channel closing and rectification in GtACR1, we performed quantitative kinetic analysis of laser flash-evoked photocurrents in several mutants with glutamate (Glu) substituted for the native residues on the extracellular or cytoplasmic side of the photoactive site. Glu substitutions produced opposite effects on two channel closing components depending of the location of the mutated residues with respect to the Schiff base. The presented data along with our previous observations led us to the hypothesis that two-step channel closing is modulated by the electrostatic field across the reaction site. This hypothesis also explains opposite rectification of fast- and slow-decaying currents in the wild type.

We have shown earlier that in the wild-type GtACR1 kinetics of the fast decay component roughly correlates with the appearance of the blue-shifted M intermediate of the photocycle (deprotonation of the Schiff base), and that of the slow decay component, with M dissipation (reprotonation of the Schiff base) (12). In the current study we confirm that such coupling holds true also for mutants with opposite directions of rectification, which we expressed and purified from Pichia.

Our protein-wide carboxyl residue substitution screen revealed that mutations only of the residues contributing to the intramolecular tunnel (7) caused strong changes in rectification of the current-voltage dependence, which confirmed our hypothesis that the pathway for anion passage is indeed created by expansion of this tunnel upon photoexcitation.

Materials and Methods

Electrophysiological characterization of GtACR1 mutants was performed using whole-cell photocurrent recording as previously described (1). HEK293 (human embryonic kidney) cells were transfected using the ScreenFectA transfection reagent (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). Photocurrents were recorded 48–72 h after transfection in whole-cell voltage clamp mode at room temperature (25°C) with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) and digitized with a Digidata 1440A using pClamp 10.7 software (both from Molecular Devices). Laser excitation was provided by a Minilite Nd:YAG laser (532 nm, pulsewidth 6 ns, energy 12 mJ; Continuum, San Jose, CA). Continuous light pulses were provided by a Polychrome V light source (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Kaufbeuren, Germany) at 15 nm half-bandwidth in combination with a mechanical shutter (Uniblitz Model LS6, half-opening time 0.5 ms; Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY). The holding potential values were corrected for liquid junction potentials calculated using the Clampex built-in LJP calculator (13). The sample size was estimated from previous experience and published work on a similar subject, as recommended by the NIH guidelines (14).

Absorption spectra of purified GtACR1 mutants in the ultraviolet-visible range were recorded using a Cary 4000 spectrophotometer (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Light-induced absorption changes were measured with a laboratory-constructed crossbeam apparatus. Excitation flashes (532 nm, 6 ns, up to 40 mJ) were provided by a Surelite I Nd-YAG laser (Continuum).

Homology models of the GtACR1 mutants were created by I-TASSER suite (15) using the wild-type GtACR1 structure (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 6EDQ) as the template. PyMOL software (http://www.pymol.org) was used for visualization and analysis of molecular structures. The intramolecular tunnel was identified by CAVER software (16). Sequence logos were created using WebLogo algorithm (17).

A detailed description of the acquisition, processing, and analysis of the data is provided in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Results

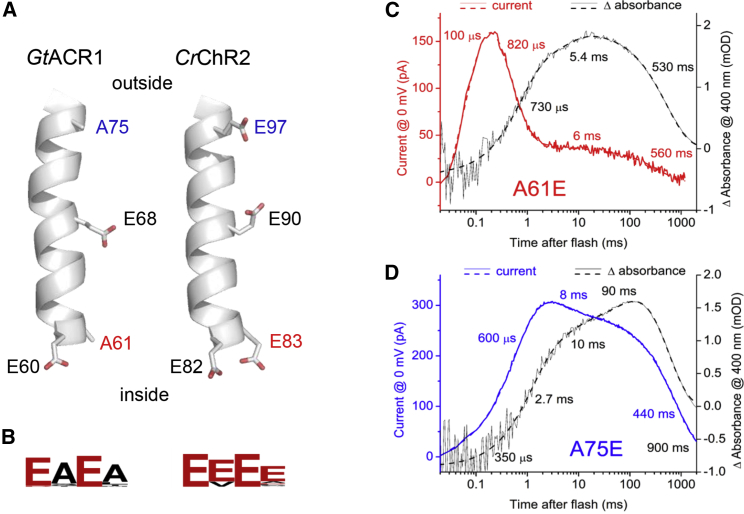

Two of the four Glu residues conserved in the second transmembrane helix (TM2) of CCRs are neutral residues in anion channelrhodopsins (ACRs), most frequently Ala (Fig. 1, A and B). In GtACR1, these are Ala61 in the cytoplasmic end of the intramolecular tunnel detected in the dark structure (7), inward of the Schiff base, and Ala75 in the extracellular end of the tunnel, outward of the Schiff base. The A61E and A75E mutations caused strong but opposite changes in the kinetics of photocurrent elicited by 6-ns laser flashes at zero voltage (Fig. 1, C and D). In each mutant channel, closing proceeded in two kinetically different phases, as in the wild type. We performed multiexponential fitting of the current traces and obtained the times constants (τ) and amplitudes of the two components of the photocurrent decay. The rate and contribution of the fast closing component were greatly enhanced in the A61E mutant, whereas the A75E mutation led to the opposite effect: enhancement of slow channel closing.

Figure 1.

Glu substitutions at positions 61 and 75 change current decay kinetics and voltage dependence in the opposite directions. (A) Structures of TM2 in GtACR1 (PDB: 6EDQ) and C. reinhardtii channelrhodopsin 2 (PDB: 6EID). The side chains of the Glu residues conserved in CCRs and their counterparts in ACRs are shown as sticks. (B) Residue conservation logos of the corresponding positions in currently known functional ACRs and CCRs. (C and D) Photocurrent traces (red and blue, left axis) and absorbance changes monitored at 400 nm (black, right axis) recorded in response to laser flash excitation from the A61E mutant (C) and A75E mutant (D). To model current traces at 0 mV with an improved signal-to-noise ratio, we subtracted the traces recorded at −20 mV from those at 20 mV, which have the same shape but the opposite signs. The solid lines show experimental data, and the dashed lines show multicomponential fits. To see this figure in color, go online.

To probe the influence of the introduced acidic group on the photoactive site, we expressed and purified these mutants from Pichia and carried out measurements of laser flash–induced absorbance changes. In each of these mutants we observed temporal correlation between the Schiff base deprotonation (M formation) and the fast channel closing, and between Schiff base reprotonation (M decay) and slow channel closing (Fig. 1, C and D), as we reported earlier in the wild-type GtACR1 (12). Absorption change differences between the two mutants were also observed at other characteristic wavelengths (Fig. S1, A and B). The maxima of the absorption spectra of the purified A61E and A75E mutants were identical at 511 nm and differed only 4 nm from that of the wild type (Fig. S1 C), which indicates that neither glutamate residue introduced by mutation became a counterion directly interacting with the chromophore, as expected from their location >9 Å from the Schiff base.

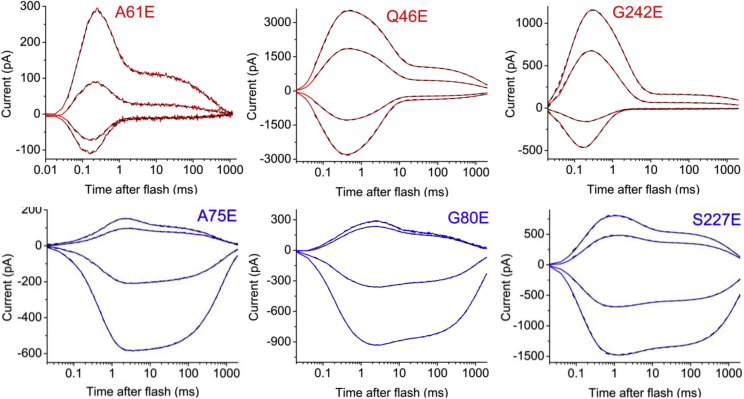

Next, we tested these and four other glutamate substitution mutants, in two of which a presumably negatively charged side chain was introduced inward of the photoactive site (Q46E and G242E), and in two, outward of it (G80E and S227E), at different holding potentials (Fig. 2). Substitution with a glutamate residue caused a strong perturbation of the kinetics of single-turnover laser flash–induced currents in all these mutants (Fig. 2). At −60 mV, the ratio of the τ values of slow to fast closing increased from 20 to 1000-fold in the mutants, as compared to the wild type (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Photocurrent traces recorded at different voltages from Glu substitution GtACR1 mutants upon excitation with laser flashes. The traces were recorded at −60, −30, 30, and 60 mV at the amplifier output (from bottom to top). The solid colored lines show the experimental data, and the dashed black lines show multiexponential fits. To see this figure in color, go online.

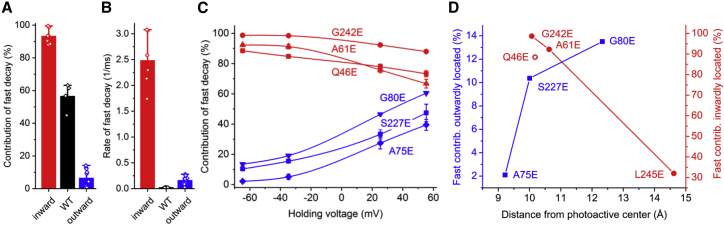

In all analyzed mutants, the amplitude of the fast component showed no or outward rectification (Fig. S3), as in the wild type. However, the slow component showed strong inward rectification only in the mutants in which the negative charge was placed outward of the Schiff base (Fig. S3). Next, we analyzed contributions of the amplitude of the fast component to the overall current (its ratio to the sum of the two components). At −60 mV, this contribution was roughly an order of magnitude greater in the mutants, in which a negative charge was placed inward of the Schiff base than in those in which it was placed outward, whereas in the wild type the amplitudes of the components were almost equal (Fig. 3 A). The rate of the fast closing increased in all mutants, as compared to the wild type, but it was almost an order of magnitude greater in the mutants with Glu substitutions of inwardly than outwardly located residues (Fig. 3 B). Upon shifting of the holding voltage to more positive values, the contribution of the fast phase decreased for the inwardly located mutations and increased for the outwardly located mutations (Fig. 3 C). In summary, introduction of inward of the photoactive site enhanced fast, outwardly rectifying channel closing, whereas placement of a negative charge outward of the photoactive site shifted the channel closing in favor of the slow, inwardly rectifying current component.

Figure 3.

Influence of Glu substitutions on the kinetics of laser flash–induced photocurrents. (A and B) Mean contributions (A) and rates (B) of the fast current decay phase in the mutants of the residues located inwardly of the Schiff base (red), the wild type (black), and the mutants of the residues located outwardly of the Schiff base (blue). (C) Voltage dependence of the contribution of the fast decay phase in the individual mutants. The data points are the mean values ± SE (n = 3–4 cells). (D) Dependence of the contribution of the fast decay phase on the distance from the side chain of the mutated residue to the photoactive site. To see this figure in color, go online.

We hypothesized that the opposite effects of an acidic group placed outward or inward of the photoactive site on the channel kinetics and rectification was due to its electrostatic influence on the photoactive site. For distance measurements, we defined this site as the protonated retinylidene Schiff base and its two potential proton acceptors, Glu68 and Asp234 (11,12). To test our hypothesis, we made homology models of the mutants (Fig. S4) and calculated the mean distances from the introduced Glu side chain to the Schiff base, Glu68, and Asp234 for each mutant. The mean distances were very similar in the A61E, Q46E, and G242E mutants. Therefore, we added to our analysis a fourth outwardly rectifying mutant, L245E, in which the introduced glutamate is located further away from the photoactive site than in the other three mutants. A series of laser flash–evoked current traces generated by GtACR1_L245E is shown in Fig. S5 A. In this mutant, the contribution of the fast decay phase at −60 mV was smaller than in the other three analyzed mutants with Glu substitutions inward of the Schiff base, consistent with the more distant location of the mutated residue from the photoactive center, but its voltage dependence was similar to that in the other mutants of this group (Fig. S5 B). In each group of the mutants, with Glu substitutions inward or outward of the Schiff base, the contribution of the fast phase was proportional to the distance of the mutated residue from the photoactive site (Fig. 3 D). The contribution measured in the Q46E mutant was smaller than expected from the monotonic proportionality. The smaller value may be explained by this residue’s location outside of the dark-state tunnel unlike the other residues analyzed.

In the wild-type GtACR1, the two currents of approximately equal amplitudes with opposite directions of rectification result in the apparent absence of rectification of the peak current (1,11). However, introduction of glutamate residues into the tunnel caused such a strong imbalance between the fast and slow current components that rectification of the main current peak was observed even with continuous light pulses (Fig. S6, A and B). Replacement of Asp61 with polar Ser or Thr residues did not influence rectification (Fig. S6 C), which confirmed that its change was brought about by a negative charge of the side chain.

Replacement of Ala at positions 61 or 75 (in the inner and outer half-tunnels, respectively) with Arg, expected to be positively charged, did not influence substantially the kinetics of laser flash-induced photocurrents (Fig. S7 A). Closing of the channel remained biphasic with comparable component amplitudes. The τ values of fast closing were only slightly altered in both mutants. Also, the current-voltage relationship of the peak current recorded from these mutants in response to pulses of continuous light was similar to that in the wild type, i.e., did not show strong rectification (Fig. S7 B). It appears that the presumed positive charges at these positions are shielded in the open channel state. These data confirm that it is the negative charge and not the mass of the Glu residues at these positions that alters the closing rates of the channel.

For a protein-wide acidic residue substitution screen we used continuous light stimulation and determined the rectification index (RI) defined as the ratio of the peak current at 60 mV to that at −60 mV in response to 1-s light stimulus. The mean RI values for all 75 tested mutants are shown in Fig. S8, and the mean current amplitudes recorded at 60 and −60 mV are shown in Figs. S9 and S10, respectively. Using the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test at p < 0.01, we classified the mutants into five categories according to their median RI values: RI < 0.5, 0.5 < RI < 1, RI = 1, 1 < RI < 2, and RI > 2 (see Table S1 for raw numerical data and full statistical analysis). All mutations that caused strong rectification in either direction also reduced the current amplitude, as compared to the wild type, even at the favorable voltage (Fig. S11). Glu replacement of Leu64 and Thr101, which, together with Met101, form the central constriction of the intramolecular tunnel (7), caused such dramatic reduction of photocurrents that the RI could not be determined.

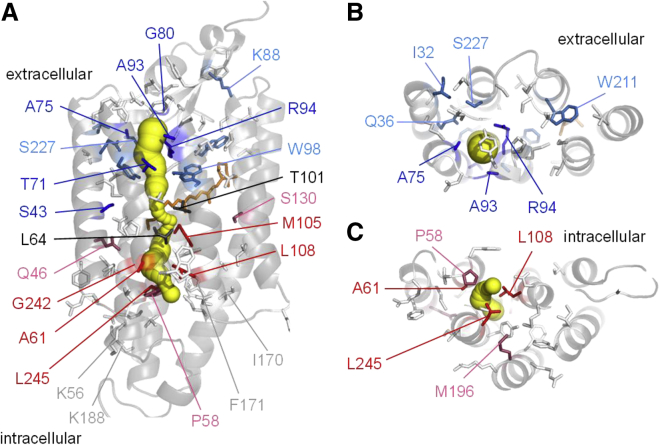

Distribution of the residues mutation of which showed statistically significant rectification within the GtACR1 molecule displayed a clear pattern (Fig. 4). Strong rectification in either direction (RI < 0.5 or >2) was observed almost exclusively in the mutants of the residues that line the intramolecular tunnel. These results support our hypothesis that the anion conduction pathway is created in illuminated GtACR1 by expansion of the intramolecular tunnel we detected in its dark (closed) state structure (7).

Figure 4.

Side (A), top/extracellular (B), and bottom/intracellular (C) views of GtACR1 structure (PDB: 6EDQ [7]) showing the side chains of the tested residues color-coded according to the RI measured in their mutants. Only 15-Å slabs centered on Ala75 and Ala61, respectively, are shown in (B and C) for clarity. The intramolecular tunnel is shown in yellow. The color code for amino acid side chains is as follows: dark blue, RI < 0.5; light blue, 0.5 < RI < 1; light gray, RI = 1; pink, 1 < RI < 2; red, RI > 2, as determined by the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test at p < 0.01; black, RI could not be determined because of severe suppression of photocurrents. To see this figure in color, go online.

The direction of rectification observed in the mutants correlated with the position of the mutated residue within the tunnel. Residues, replacement of which with acidic residues caused strong inward rectification (Thr71, Ala75, Gly80, Ala93, and Arg94), form the extracellular portion of the tunnel (Fig. 4). Oppositely, residues, replacement of which caused strong outward rectification (Ala61, Met105, Leu108, Gly242, and Leu245) form the tunnel’s cytoplasmic portion (Fig. 4). Of all tested residues outside the tunnel only replacement of Ser43 caused strong rectification (RI < 0.5). Modest rectification (i.e., with RI between 0.5 and 2, but significantly different from 1) resulted from Glu or Asp substitutions of several other residues (including Gln46 and Ser130) that do not contribute to the tunnel in the dark state. Our interpretation is that mutations of these residues either indirectly influence the chloride pathway via long-range interactions or that these residue positions become exposed to the tunnel after illumination.

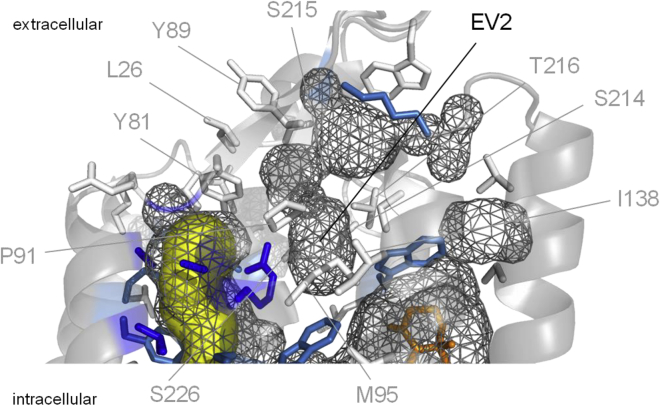

An intramolecular cavity opened to the extracellular space (a vestibule) was found in the GtACR1 dark structure (7) in addition to the continuous tunnel (Fig. 5). The crystal structure of the hybrid CCR known as C1C2 (8) also shows a vestibule in the corresponding position (EV2), which is thought to represent the main extracellular entry into the channel pore in this molecule. In the dark GtACR1 structure, EV2 is separated from the intramolecular tunnel by hydrogen-bonded Tyr81, Arg94, and Glu223 (7,18). However, it could not be excluded that upon photoexcitation, this hydrogen-bonded network is broken and the second vestibule is merged with the tunnel. To test this hypothesis, we measured the RI in the mutants of the residues that line the second vestibule. Individual Glu replacement of nearly all of these residues (Pro91, Met95, Ser214, Ser 215, Thr216, and Ser226) did not affect rectification (Fig. S6), which suggests that the second extracellular vestibule plays only a minor, if any, role in anion conduction in GtACR1. Thus, our functional data provide empirical confirmation of the stability of hydrogen bonding between Tyr81, Arg94, and Glu223 deduced from all-atom molecular dynamic simulations of GtACR1 (19).

Figure 5.

The second extracellular vestibule in GtACR1 (EV2). The side chains of contributing residues are color-coded according to the RI measured in their mutants, as defined in the Fig. 4 legend. The intramolecular tunnel is shown in yellow, and the intramolecular surface is shown as gray mesh. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

In the current study, we performed analysis of photocurrents in GtACR1 mutants with acidic substitutions introduced along the intramolecular tunnel that we detected earlier in the dark (closed) state structure (7). The results led us to the hypothesis that closing of the channel is strongly modulated by the electric field across the photoactive site. This interpretation is based on three observations:

-

1)

The changes in the current kinetics were opposite depending on the position of the mutagenetically introduced negative charge in the tunnel. When negative charge was introduced into the cytoplasmic half-tunnel, fast closing of the channel was enhanced (i.e., its rate and contribution were increased). In contrast, when negative charge was placed in the outer half-tunnel, slow closing was enhanced. Such changes in the kinetics were qualitatively similar to the dependence of fast- and slow-closing photocurrents on holding potential in the wild type (11). Therefore, the fast or slow channel closing in GtACR1 was selectively enhanced depending on the direction in which the electric field was changed, regardless of whether it was achieved by alteration of the holding potential or by mutation.

-

2)

The magnitude of the effect of mutations on current kinetics was inversely proportional to the distance from the introduced Glu to the photoactive site, as is expected from the distance-dependent strength of the induced electric field.

-

3)

The observed effects of mutations cannot be attributed to direct interaction of the introduced Glu with the chromophore because purified mutant proteins that showed opposite effects on photocurrent kinetics had identical absorption spectra maxima.

In the wild-type GtACR1, the rates of fast channel closing and Schiff base deprotonation (M formation) increased upon depolarization of the membrane or upon increase in the bath pH (12), which is expected if the Schiff base proton is transferred to an outwardly located acceptor (i.e., against the electric field). In contrast, the rate of slow channel closing, which temporarily correlated with Schiff base reprotonation (M decay), decreased upon depolarization of the membrane, which indicated that during this step the proton moved in the opposite direction (i.e., along the field), the reduction of which by depolarization slowed the movement of the proton. This means that deprotonation and reprotonation of Schiff base take place on the same (outer) side.

We had shown earlier that in the wild-type GtACR1 kinetics of the fast-decay component roughly correlates with the appearance of the blue-shifted M intermediate of the photocycle (deprotonation of the Schiff base) and that of the slow-decay component with M dissipation (reprotonation of the Schiff base) (12). However, such correlation can be followed only at zero holding potential, the strength of the potential across the protein in the purified protein in micellar suspensions. Nevertheless, the field can be modified by Glu substitutions within the protein tunnel. In the current study, we show that the temporal correlation between fast and slow current decay and de- and reprotonation of the Schiff base holds true also for the two mutants that exhibit opposite effects on the current kinetics and rectification of the current-voltage relationship (A61E and A75E).

The radius of the intramolecular tunnel that we detected in the dark-state crystal structure is less than the radius of the chloride ion along almost its entire length (7). There are two possibilities: either this tunnel expands upon illumination to pass ions, or a sufficiently wide path for ions is created elsewhere in the protein. To discriminate between these two possibilities, mutation scanning with a functional test was needed. Measuring the current at any given voltage would not be sufficiently specific because a mutation may cause a protein folding defect rather than specifically block the conduction pathway. Therefore, we measured the RI, which is a property of the ion flux, and found that it was changed only by mutations of the residues that form the tunnel. Our interpretation is that the ions indeed flow through this tunnel after its expansion and not somewhere else in the protein.

The physical mechanisms that cause rectification of the current-voltage dependence in anion channels remain poorly understood. Published mutagenetic analysis of rectification in such channels has so far been limited to only a few key residues implicated in gating (20,21). The results of our protein-wide mutant screen may be relevant not only to ACRs but also to other, structurally unrelated types of anion channels.

Conclusions

Glutamate replacement only of residues that form the intramolecular tunnel (7) caused major changes in the balance between fast and slow channel closing and rectification of the current-voltage dependence. The sign of the effect was opposite for mutations in the inner and outer half channel, and the magnitude of these changes was proportional to the distance of the mutated residue from the photoactive site. These results indicate that channel closing and rectification are controlled by the local electrical field in the photoactive site of the protein. The temporal correlation between the kinetic phases of channel closing and intramolecular movements of the Schiff base proton in GtACR1 (12) persisted even when the balance between the two phases was altered by mutations.

Author Contributions

O.A.S., E.G.G., and J.L.S. designed the research. O.A.S. and E.G.G. carried out patch clamp recording, absorption spectroscopy, and flash photolysis measurements. H.L. and X.W. expressed and purified GtACR1 mutants from Pichia. O.A.S., E.G.G., and J.L.S. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM027750, the Hermann Eye Fund, and Endowed Chair AU-0009 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation to J.L.S. J.L.S., E.G.G., O.A.S., and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston have filed patent applications that relate to ACRs (PCT application PCT/US2016/023095, titled “Compositions and Methods for Use of Anion Channel Rhodopsins”).

Editor: Sudha Chakrapani.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.10.009.

Supporting Material

Sheet 1: Peak current amplitudes recorded at 60 mV at the amplifier output in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 2: Peak current amplitudes recorded at -60 mV at the amplifier output in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 3: Rectification index measured in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 4: The output of the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test applied to the data in Sheet 3.

References

- 1.Govorunova E.G., Sineshchekov O.A., Spudich J.L. Natural light-gated anion channels: a family of microbial rhodopsins for advanced optogenetics. Science. 2015;349:647–650. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa7484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahn M., Gibor L., Yizhar O. High-efficiency optogenetic silencing with soma-targeted anion-conducting channelrhodopsins. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4125. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06511-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messier J.E., Chen H., Xue M. Targeting light-gated chloride channels to neuronal somatodendritic domain reduces their excitatory effect in the axon. eLife. 2018;7:e38506. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mardinly A.R., Oldenburg I.A., Adesnik H. Precise multimodal optical control of neural ensemble activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:881–893. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Z.D., Chen Z., Shen W.L. Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:921–932. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shang C., Liu A., Cao P. A subcortical excitatory circuit for sensory-triggered predatory hunting in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:909–920. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H., Huang C.Y., Spudich J.L. Crystal structure of a natural light-gated anion channelrhodopsin. eLife. 2019;8:e41741. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato H.E., Zhang F., Nureki O. Crystal structure of the channelrhodopsin light-gated cation channel. Nature. 2012;482:369–374. doi: 10.1038/nature10870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkov O., Kovalev K., Gordeliy V. Structural insights into ion conduction by channelrhodopsin 2. Science. 2017;358:eaan8862. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oda K., Vierock J., Nureki O. Crystal structure of the red light-activated channelrhodopsin Chrimson. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3949. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sineshchekov O.A., Govorunova E.G., Spudich J.L. Gating mechanisms of a natural anion channelrhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:14236–14241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513602112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sineshchekov O.A., Li H., Spudich J.L. Photochemical reaction cycle transitions during anion channelrhodopsin gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E1993–E2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525269113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry P.H. JPCalc, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correcting junction potential measurements. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1994;51:107–116. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dell R.B., Holleran S., Ramakrishnan R. Sample size determination. ILAR J. 2002;43:207–213. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.4.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J., Yan R., Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlikova B., Sebestova E., Sochor J. CAVER Analyst 1.0: graphic tool for interactive visualization and analysis of tunnels and channels in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2684–2685. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y.S., Kato H.E., Deisseroth K. Crystal structure of the natural anion-conducting channelrhodopsin GtACR1. Nature. 2018;561:343–348. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato H.E., Kim Y.S., Deisseroth K. Structural mechanisms of selectivity and gating in anion channelrhodopsins. Nature. 2018;561:349–354. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0504-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linsdell P. Location of a common inhibitor binding site in the cytoplasmic vestibule of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8945–8950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulino C., Neldner Y., Dutzler R. Structural basis for anion conduction in the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A. eLife. 2017;6:e26232. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sheet 1: Peak current amplitudes recorded at 60 mV at the amplifier output in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 2: Peak current amplitudes recorded at -60 mV at the amplifier output in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 3: Rectification index measured in individual HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated mutants. Sheet 4: The output of the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test applied to the data in Sheet 3.