Abstract

HIV infection remains a significant public health problem especially among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) ages 13–18. At the same time, there is a dearth of evidence-based HIV prevention interventions for YMSM at high risk for HIV. We adapted the MyPEEPS intervention – an evidence-based, group-level intervention for YMSM – to individual-level delivery via mobile application (app), for greater reach to the target population. The purpose of this study is to describe the adaptation of the group-based intervention curriculum to a mobile app. We used an expert panel (n=8) review, in-depth interviews with targeted end-users (n=40), and weekly meetings with the investigative team and the software development company to translate the group-based intervention into a mobile app. The expert panel recommended changes to the MyPEEPS intervention in the following key areas: 1) biomedical interventions, 2) salience of intervention content, 3) age group relevance, 4) technical components, and 5) stigma content. Interview findings from YMSM largely reflected current areas of focus for the intervention and recommendations of the expert panel for new content. In regular meetings with the software development firm, guiding principles included development of dynamic content, while maintaining fidelity of the original curriculum and shortening intervention content overall for mobile delivery. Given the strength of the original evidence-based MyPEEPS curriculum and our rigorous mobile adaptation process, we anticipate that MyPEEPS Mobile will be novel, innovative, and scalable resulting in a strong public health impact.

Keywords: adolescents, HIV Prevention, mHealth, sexual minority, adaptation

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains a significant public health problem especially among men who have sex with men (MSM), who represent only 4% of the male population in the United States (US) but account for 70% of new HIV infections among males1, highlighting the need for intensive HIV prevention strategies. In 2016, of the 39,782 people in the US newly diagnosed with HIV2, 6,848 (17.2%) were YMSM ages 13–243. Among youth, YMSM account for 81% of new diagnoses3, which are linked to high-risk sexual behavior and disproportionately occur in African American/Black and Latino/Hispanic YMSM4.

Yet, there remains a dearth of evidence-based HIV prevention interventions for racially and ethnically diverse YMSM. To address this need, our research team used mixed methods to adapt“Male Youth Pursuing Education, Empowerment & Prevention around Sexuality” (MyPEEPS), a theory-driven, multi-ethnic, group-level intervention for diverse YMSM5. MyPEEPS is based on the Social-Personal Framework6 which builds on Social Learning Theory7 and adds important psychosocial (e.g., affect dysregulation) and contextual risk factors (e.g., family, peer, and partner relationships) related to youth risk-taking. MyPEEPS is a manualized curriculum consisting of six interactive group sessions (2 hours each), delivered twice weekly for three weeks focusing on: HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) epidemiology in YMSM, building knowledge and skills for safer sex, minority stress, emotion regulation, interpersonal and substance-related risk factors, developing risk reduction plans, and condom negotiation5. In the MyPEEPS curriculum, the learning process is facilitated through the stories of four “peeps” (Philip, Nico, Artemio, and Tommy) who are featured in a series of scenarios that open each session. The characters were composites of YMSM who participated in the formative phase of intervention development8,9. A running theme throughout the intervention was sexual risk reduction and goal-setting through an activity, “BottomLine,” in which participants were challenged to articulate how much risk is acceptable for different sexual acts and to continually re-consider these limits after exposure to session content. MyPEEPS was initially tested from 2009–2010 with 101 diverse (23% white, 39% black, 27% Latino, 12% other) YMSM ages 16–20 years old. Over the entire follow-up period, intervention participants were less likely than controls to engage in any sexual behavior while under the influence of substances (p < .05), and a decreasing trend in unprotected anal sex while under the influence of substances was also observed in this group (p = .08), which is an important risk factor for acquiring HIV.10 Thus, the MyPEEPS intervention demonstrated evidence of preliminary efficacy in reducing sexual risk, specifically sexual risk while under the influence of substances.11

Similar to challenges faced by other in-person, group-level interventions in at-risk populations, the initial MyPEEPS trial participants reported that a key difficulty with the intervention was travel distance to access the group-based intervention11, therefore we did not think that it was feasible to conduct a larger trial of the face to face intervention. To overcome this challenge, we adapted the MyPEEPS intervention to a mobile application (app), given the increased ubiquity of smartphones in the daily life of many adolescents since the initial trial, especially among 13–18 year olds12. Mobile devices have the advantage of simple interface for users, accessibility anywhere Internet access is available, relative affordability, and have been promoted specifically to reach stigmatized and disenfranchised populations13,14. A recent review of 62 HIV-specific mobile health (mHealth) studies suggest positive effects for health promotion across the HIV care continuum13. Among high risk MSM, mHealth approaches for HIV prevention show significant effects for both reduction of HIV risk behavior and promotion of HIV testing15. Among youth ages 13–29, evidence suggests that web-based interactive and educational approaches16,17 are efficacious for delaying sexual initiation and increasing knowledge of HIV/STIs and condom self-efficacy18.

In addition to the adaptation for mobile format, we also sought to: 1) adapt the MyPEEPS comprehension suitability for a younger audience (ages 13–15) including those not yet sexually initiated, 2) include the most recent bio-behavioral HIV prevention approaches, and 3) appeal broadly across US regions (specifically in the study cities of Chicago, IL; Birmingham, AL; New York City, NY; and Seattle, WA) and racial/ethnic groups. This paper describes the process of adapting the original MyPEEPS interventionto a mobile response-driven web-based platform, accessible by smartphone or other web-enabled devices and for racially/ethnically-diverse sexual minority youth to better support the potential for this mobile solution to be efficacious in improving health outcomes.

Methods

We used a series of methodologies, including expert panel review meeting which was held prior to the start of other study activities. Following this meeting, we conducted, in-depth interviews with targeted end-users, and, in parallel, held weekly meetings between the investigative team and the software development company, to translate the group-based intervention to a mobile app.

This protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Columbia University Medical Center with a waiver of parental permission for participation of minors (aged 13–17). Table 1 illustrates an outline of the original MyPEEPS sessions and content.

Table 1.

MyPEEPS Original Curriculum Components

| Session | Topics |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction and Communication | Intervention overview: discuss effective interpersonal communication and HIV/STI epidemiology in YMSM |

| 2. HIV/AIDS and STIs | Safer sex specific to YMSM, effective condom use, and STIs |

| 3. Managing Minority Stress | Minority stress, its influence on motivation to practice safer sex, and safer sex strategies in situations involving minority stress. |

| 4. Affect and Emotional Regulation | The influence of emotion regulation on motivation to practice safer sex, and safer sex strategies related to session content. |

| 5. Interpersonal and Substance-related Risk Factors | The influence of partner communication and substance use on motivation to practice safer sex, and safer sex strategies related to session content. |

| 6. Goal-making and wrap up | Review intervention content, develop personal risk reduction plans, and identify strategies to overcome barriers to success. |

Expert Review Panel

We first reviewed the original intervention content with an expert panel to validate the language, images, and formatting/visual cues in the original intervention curriculum to reach consensus on content addition or deletion for the app. We recruited an expert panel (N =8) of clinicians (N =4) and public health practitioners (N=3) who are also HIV prevention experts and represent diverse backgrounds and a diverse community leader (N=1). The experts were selected during our grant submission process based on their prior publication history and/or experience working diverse young men. Our expert panel members all provided a letter of support agreeing to serve in this role as part of our grant application.

Prior to the meeting, panel members and study team members received a copy of the original MyPEEPs curriculum for review. Expert panel members (N=8), study team members (N=12) comprised of clinicians (N=5), public health experts (N=5) and community leaders (N=2) participated in a 2-day meeting at Columbia University School of Nursing. We identified five priority topics not included in the original curriculum: 1) Biomedical Intervention, 2) Racial Ethnic Relevance/Geographic Considerations, 3) Age Group Relevance (ages 13–18), 4) Technical Components, and 5) Stigma Management.

Extensive notes from breakout sessions were recorded and summarized to the group to validate key themes and suggestions. Following each breakout session, the expert panel and study team members re-convened and provided consolidated suggestions for revising the curriculum. To confirm fidelity to the original curriculum, a smaller group of investigators reviewed and consolidated recommendations into two categories: 1) those considered feasible and consistent with the aim of adaptation and 2) maintaining the fidelity of the original curriculum. A paper-and-pencil version of the revised curriculum was then created and circulated to the expert panel, including rough programing suggestions directed to the software developers.

Software Development and Investigator Team Meetings

The software development firm has experience in building apps for smartphones, tablets, smartwatches, and the Web. The development team included a project director, programmer, and artistic director who reviewed the paper-and-pencil version of the revised curriculum before a meeting with investigators (RS, LMK, MAH), and created examples of potential directions for adaptation to mobile platforms. In this initial, in-person 2-day meeting, the group reviewed each intervention activity in detail to inform the mobile content design. Following this meeting, the development and investigative team met at least every other week via video conference to review the progress on the visual design and prototyping of the app.

In-Depth Interviews

In parallel with on-going app development, we aimed to further refine app content by conducting in-depth interviews with the target population across the five priority topics. The app was not yet available for the participants to view. Inclusion criteria were: 1) age 13–18, 2) sex assigned male at birth and identify as male, non-binary, genderqueer, or gender non-conforming, 3) comfortable speaking and reading in English, 4) has a smartphone, 5) same-sex sexually active or attracted, and 6) HIV-negative or status unknown (self-report). Participants were recruited at each study location (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; New York, NY; and Seattle, WA) via convenience sampling (e.g., flyers, posting on social media, and direct outreach at community-based organizations). Sample size was N=40 (10 at each site), which we estimated would be sufficient to reach saturation based on similar mobile development projects19–21. Participants provided written informed assent (ages 13–17) and consent (age 18). Audio-recorded interviews were conducted face-to-face using a semi-structured interview guide. Data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a directed content analysis approach22 by two study team members until consensus was reached. Findings from interview data analysis were then used to refine the mobile app content.

Results

We outline the findings according to the methodology we employed to adapt the original MyPEEPS intervention—expert review panel, software development and investigator team meetings, and in-depth interviews.

Expert Review Panel

A summary of key findings from the expert panel, arranged by topic area and relevance to the adaptation of the MyPEEPS intervention, follows:

Biomedical Interventions

The expert panel discussed integration of content regarding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), as well as home-based HIV testing, which were not included in the original intervention. Given participants’ young age, the group recommended providing basic information for each prevention strategy (e.g., What is it? What and who is it for? How do I get it?), information on how to access these services in each city, and on adolescents’ legal rights to confidential sexual health care. PrEP access may require parental permission, therefore the group recommended including information about how to talk to parents or other trusted adults about sexual health. Experts agreed that it is important that app content direct users to seek further information from healthcare providers. Finally, they recommended development of a protocol to add new substantive app content on these technologies as it becomes available (e.g., new testing innovations, extension of clinical guidelines for PrEP to minors).

Racial Ethnic Cultural Relevance

Because this adaptation extends the target population of MyPEEPS to include minority groups who were not represented in the original MyPEEPS study (e.g., Native Americans, Asian Americans), the expert panel recommended additional sensitivity and balance in the intervention content regarding language and/or references rooted in beliefs and practices of the Western Hemisphere. Furthermore, the panel noted that there is more awareness of multiple identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic class) in popular culture and this should be reflected to the degree possible in the curriculum. The panel also acknowledged that the content is specific to cisgender, male identity and, therefore, not likely to be appropriate for those who identify as transgender or female. Finally, because the mobile app will have widespread reach, the panel recommended removing references and language that may not be understood across geographic regions.

Age Group Relevance

The panel recommended that the language of the app be tailored to a 6th −8th grade reading level, be as conceptually concrete as possible, and include engaging and dynamic functionality, such as sounds and videos. There were suggestions to consider delivering two types of content targeted to different developmental stages and/or age, i.e., older kids (16–18 year olds) versus younger kids (13–15 year olds). There was a recommendation to revise the MyPEEPS characters to ensure that one character is under 16 years of age and one character represents a Native American background. Finally, the panel recommended consideration of strategies to reduce the risk of “outing” participants via app use, i.e., to protect their privacy.

Technical Components

The original group-based MyPEEPS was designed to be highly interactive, with the psycho-educational content delivered through a series of games, scenarios, and role-plays within each session. The panel recommended that the app reflect this original design with interactive activities and “gamification” components. Panel members suggested using narrative to drive user engagement, e.g., cliff-hangers and choosing your own adventure. They also recommended keeping all content active for the period of intervention (i.e., content should not expire and can be re-visited), but also having minimum expectations for completion activities in a linear manner given that it would be easier to skip activities in an app in comparison to group-based intervention. The panel recommended encouraging this progression with positive reinforcement including positive feedback and rewards, such as “points”, and real or virtual monetary incentives. Finally, they discussed the need to create a protocol to regularly validate outside content accessed through hyperlinks in the app.

Stigma

The panel members extensively discussed how to handle content on “outness” and coming out. The group recommended that, given the participants’ young age and diversity among geographic sites, content should reflect lack of disclosure due to stigma, safety, or other concerns. They recommended that the focus should be on activating self-reflection about how social stigma may influence personal sexual health decisions. It was also noted that content include information on elements of healthy relationships.

Software Development and Investigator Team Meetings

Using responsive web design, a conventional web site is viewable on small screens and works well with touch screens. On a smartphone, a web-app is flexible for use across multiple devices and appears and functions very similarly to a native app to end-users. To highlight, a web-app has the capacity to be accessed both online via a computer or laptop and also through an app. This underscores the accessibility features that are critical to the adaptation of this intervention.

The investigative and development teams ensured the adaptation stayed true to the original curriculum while increasing the content engagement level through activities and games and condensing the overall curriculum for mobile delivery. The original six in-person sessions were translated into 21 mobile app activities (5–10 minutes per activity), re-arranged for better flow, and divided into four sequential modules or “PEEPScapades.” We incorporated as many recommendations of the expert panel as possible, resulting in a gamified, dynamic, and engaging app environment with more concrete, shorter activities, targeted to a younger and less sexually experienced group of YMSM. We maintained the psychoeducational approach of the intervention, and most of the original activities were adapted to mobile format and more prominently featured the “peeps” in scenarios and reflection activities. Table 2 illustrates the summary of the mobile app activities, divided into their respective PEEPScapades. The mobile app was developed within Drupal, an open-source content management system, allowing the study team to update the intervention content as needed.

Table 2.

MyPEEPS Adaptation to a Mobile Platform

| Mobile app activity | Summary |

|---|---|

| PEEPScapade 1: Introduction | |

| 1. Set Up MyPEEPS Profile | Introduction to the app explaining what the user should expect. User inputs name, telephone number, e-mail address, and how they prefer to get notifications. |

| 2. BottomLine | User is asked the furthest they will go with a one-time hookup in a number of sexual scenarios (when I give head, when I top, etc.) and given a selection of responses about what they will and won’t do and how they will do it (always use condom, won’t use condom, will never do this). |

| 3. Underwear Personality Quiz | User completes personality quiz and is introduced to characters in the app. Characters’ personality traits and identities are shared with “gossip.” |

| 4. My Bulls-I | User is asked to think about identity traits and create list of their top five important or unique identity traits after seeing an example of activity completed by one of the app characters, “P” (Philip). |

| PEEPScapade 2: #realtalk | |

| 5. P’s On-Again Off-Again BottomLine | Video animation of text conversation between two characters, P and Nico, about P’s new relationship that has led him to ignore his BottomLine. The user is asked to complete questions about why P should be concerned about his BottomLine. There are two videos with two sets of questions (Video → questions → video → questions). |

| 6. Sexy Settings | User is presented several settings in which sex takes place and potential threats to BottomLine and asked to match each setting to correct threat. |

| 7. Goin’ Downhill Fast | User is presented with information about effects of alcohol and common illicit or misused drugs. Resources for additional information on each substance are provided via external web links. After reading through information, users match substances to potential threats to the BottomLine in specific scenarios. |

| 8. Step Up, Step Back | User is introduced to personal identities and characteristics that may place them at a societal advantage or disadvantage, termed “VIP (privileged)/Non-VIP (non-privileged)” status. User is then asked series of questions related to their own life experience and an avatar representing user moves back and forth in a line for entry to a night club as they answer questions from their own experience. User is then asked to consider how these experiences impact them personally and may make them vulnerable to risk. |

| 9. HIV True/False | User completes a series of True/False questions related to HIV, with detailed fact-based information provided for each response. |

| 10. Checking In On Your BottomLine | User is given opportunity to review and make changes to their BottomLine, taking into consideration any information they learned from completed activities. |

| PEEPScapade 3: P Woke Up Like This | |

| 11. P Gets Woke About Safer Sex | User is presented scenario about P trying to make his way to clinic for HIV testing on public transportation. P experiences difficulties and rude behavior on the bus and user is presented with recommendations for managing anger and frustration. |

| 12. Testing With Tommy | User watches a video animation about Tommy’s first experience being tested for HIV. Video presents clinic scenario and discussion with the HIV test counselor to communicate basic information about access to HIV testing services and what to expect. |

| 13. Well Hung?? | User completes an activity matching (dragging and dropping, i.e., “hanging”) a given sexual act with its corresponding level of risk (no risk, low, medium, high), to apply lessons learned in prior activities specific to HIV/STI transmission risk. |

| 14. Ordering Steps to Effective Condom Use | User is presented with 12 steps for effective condom use, and must correctly order the steps by selecting them sequentially from list of all steps. |

| 15. Checking In On Your BottomLine Again | User is again given the opportunity to review and make changes to their BottomLine, taking into consideration any information learned in prior activities. |

| PEEPScapade 4: Making Tough Situations LITuations | |

| 16. Peep in Love | User is presented scene where P is confronted with a “swirl of emotions” related to a sexual encounter with his current boyfriend. User is then asked to identify those feelings and provided with affect management techniques to stick to their BottomLine. |

| 17. 4 Ways To Manage Stigma | User is presented with four different strategies to manage stigma. They are then asked to match those strategies to scenarios presented as comic panels. |

| 18. Rubber Mishap | User is asked to answer a series of questions about threats to BottomLine while screen on their device shakes to mimic being under the influence of drugs or alcohol. |

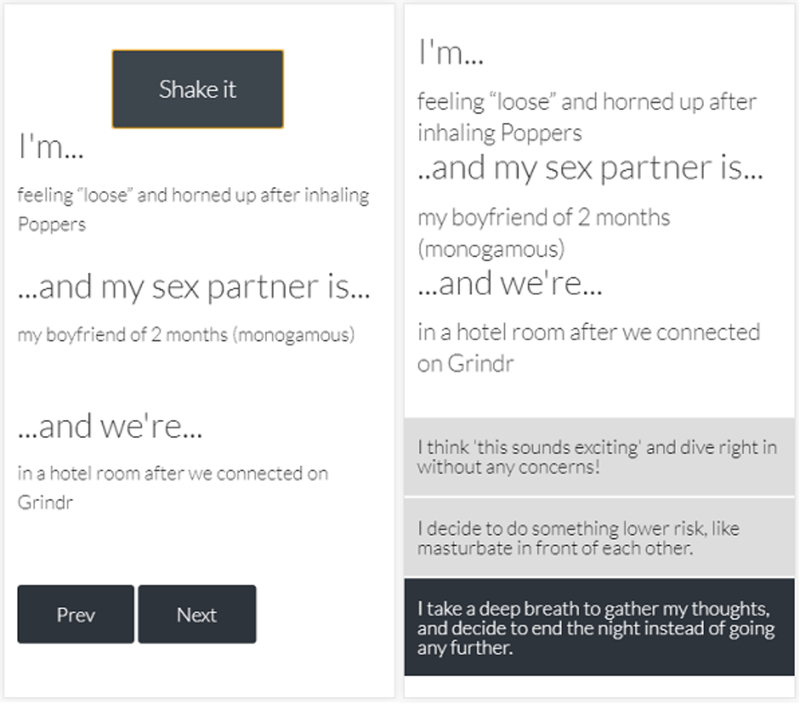

| 19. Get a Clue! | User is presented with a “slot machine” activity in which, using either a shake of the phone or press of a button, combinations of feelings, partner characteristics, and settings are presented and they are asked what sexual decision they would make in each scenario, keeping BottomLine and communication strategies in mind. |

| 20. Last Time Checking In On Your Bottom Line | User is given final opportunity to review and make changes to their BottomLine, taking into consideration any information learned from completing prior activities. |

| 21. BottomLine Overview | User is presented with chronology of how their BottomLine changed throughout the course of intervention based on activities in each PEEPScapade and encouraged to continue to stick to their goals for sexual safety. |

In-Depth Interviews

To further refine app content, a total of 40 interviews (10 in each city) with YMSM ages 13–18 in each city were completed between July and December 2017. Mean age was 17 (range 14 to 18) and race/ethnicity was self-identified by participants as 12.5% Black, 45% White, 27.5% Latino, 7.5% Mixed Race, and 7.5% Asian/ Pacific Islander.

Interview data reflected current areas of focus for the MyPEEPS intervention (e.g., vulnerability due to low sexual health knowledge and/or skills to negotiate partner dynamics) as well as recommendations of the expert panel for new content. Overall, participants demonstrated low knowledge of HIV transmission risk and new prevention technologies. For example, one participant shared the following:

“I feel like I don’t have the symptoms of HIV which I don’t know what are the symptoms either so I could just feel like I’m, my health is normal from what I have seen from the past before I started having sex. So, like I think I’m fine but you never know….”

(18-year-old Chicago youth, male, Latino/Mexican, and queer/heteroflexible)

In response to a question about prior HIV-related knowledge, one participant recalled a recent “scare” following an episode involving anal sex in which the condom broke. He said:

“… I didn’t know what to do. So I pulled over and started like looking up my risks and how…He wasn’t HIV positive. I didn’t register in my brain that they have to be HIV positive to infect you with the virus. So I just kind of freaked out and went everywhere and looked at all my resources. And I called a hotline. And that’s where they talked to me. And they were like; well, if the other person is not HIV-positive, then you can’t get infected with HIV.”

(18-year old Birmingham youth, male, White, and gay)

Basic sexual health information (including HIV/STI transmission risk) was included in the original MyPEEPS intervention and translated to the app. Additional information regarding PrEP was added in the “HIV True/False” activity, including information on adolescent rights to confidential sexual health services (see example, Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

HIV true/false

Emergent themes in the interview data included the importance of fluid gender and sexual identities/attractions, the increasing use of geosocial and social media apps for “hook-ups,” concern about confidentiality for HIV testing and PrEP use, and the importance of understanding characteristics of healthy relationships. For example, regarding both sexual and gender identity fluidity, a participant in Chicago described himself as “Heteroflexible” and another participant in Chicago explained:

“I identify as a male. I definitely like, I don’t really fit between like feminine or masculine. I guess I’m kind of like in between. I kind of tend to lean toward the masculine side of it.”

(17-year-old, Hispanic/Latino, and gay)

A participant in Birmingham described his sexual attraction by stating “My pattern of attraction, I guess, is like trans-masculine people/fem boys.” Similarly, a youth in Seattle spoke of fluidity in gender expression stating:

“It goes back and forth. At times I am masculine because I can get a little violent because that’s fun competition and stuff like that. I wrestle at school, so that’s a thing. There are other times when I am just really feminine. I don’t know how to describe it.”

(16-year-old, Vietnamese, and gay)

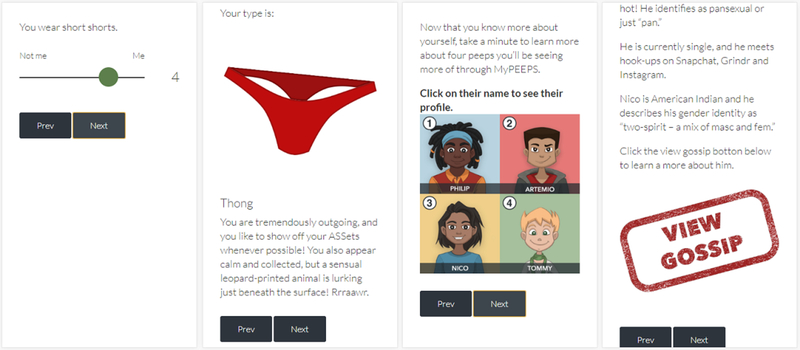

Although the original MyPEEPS content does reflect fluid gender expression, additional content was added to the “peeps” profiles in the “Underwear Personality Quiz” activity (Figure 2) to better reflect these varying identities, attractions, and expressions. Regarding concern about the confidentiality of sexual health services, one participant told us:

“I don’t know, I guess I’ve just been kind of scared to go by myself. And if I go to like, a doctor to do it, like I’m still underage so I guess the fear of them telling my parents.”

(17-year old Chicago youth, male, Hispanic/Latino, and gay)

Interviewees often mentioned use of geosocial and social media apps to find hook-ups and romantic partners and were concerned about this resulting in vulnerability, especially for those new to the app. According to one participant:

“I made an account, and Grindr, it’s people that’s living kind of close to you. So, I deleted it after two days because there was a lot of people who was texting me. I think like in the first two days it was at least 40 people. So I started feeling unsafe. So I was like, okay, I’m going to delete the app.”

(18-year old NYC youth, male, Dominican, and bisexual).

Thus, we integrated references to the use of these apps to both the “peeps” profiles in the “Underwear Personality Quiz” (Fig. 2), as well as to risk scenarios in the “Get a Clue!” activity (Fig. 3). Participants also emphasized the importance of healthy relationships. For example, one participant said,

“When you practice safe sex you are more likely…there was some statistic, I don’t remember…but you are more likely to retain the relationship with whoever you had sex with due to the fact that they won’t be worried, especially if it is a male/female relationship due to the fact that the female will not be worried about…will not be as worried about an unexpected pregnancy or teen pregnancy.”

(17-year old Birmingham youth, male, White, and “pan”)

Thus, in the “Peep in Love” activity, we added “healthy relationship tips” including getting tested together and/or sharing results with a partner(s) and building trust through mutual respect (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2.

Underwear personality quiz.

FIGURE 3.

The Get a Clue! activity

FIGURE 4.

The Peep in Love activity

Discussion

Long-term sustainability of in-person, group-level behavioral interventions, such as MyPEEPS, has been problematic for dissemination in at-risk populations, particularly among young racial and ethnic minority groups5. In response to this challenge, MyPEEPS Mobile allows us to deliver an HIV behavioral intervention to diverse high-risk YMSM at a relatively low cost23–25, engage YMSM where they meet sex partners26, and enable YMSM to participate privately on a computer, tablet, or smartphone on their own schedule as opposed to in a structured setting27.

The mobile app simulates a group-based “feel” with the multiple “peeps” scenarios and the invitation for participants to reflect and respond to the circumstances they present. The learning activities in each session were adapted to mobile format, using automated responses, videos, and games to engage participants. To be consistent with the original curriculum, the mobile intervention content are delivered by “peeps”. Much like the current group-based in-person version of MyPEEPS, the “BottomLine” feature allows participants to reflect on their own sexual health goals and challenges them through exposure to settings and situations that convey risk.

The approach that we presented is an iterative process that included a needs assessment, functional requirement identification, user interface design, and rapid prototyping. This approach supports the potential for high acceptability of MyPEEPS Mobile using formative techniques (e.g. user-centered design) involving YMSM and expert review panels to adapt and then refine the intervention—an effective method which was recently employed to refine a behavioral intervention involving YMSM28. Each of these techniques has been used in prior technology development29–31. Nonetheless, our approach provides a blueprint for the adaptation of a group-based in-person behavioral health intervention into a mobile app.

Limitations and Strengths

Two major limitations deserve mention. First, due to the high cost of software development, we were unable to incorporate every recommendation provided by the expert panel. For example, the group recommended we review the content for specificity to both “Western” and “Eastern” worldviews to be most inclusive of Native American and Asian YMSM; however, the content would have needed ground-up development, which was cost prohibitive. Second, whereas we sought the opinions of a diverse group of YMSM of younger ages (i.e., 13–15), the adaptation process did not allow for a longer timeline needed for recruitment of younger YMSM, thus interview data largely reflects older youth with a plurality of White YMSM.

The methods described in this paper allowed us to refine intervention content to focus on the recommendations by experts and end-users. At each stage of the adaptation, changes were made to the app, demonstrating that each iteration resulted in modifications to the content and functionality of the app. We iteratively refined the app content and design to meet the end-users’ needs while remaining true to the original core content. The software development firm created the app to allow us to modify the text within the app which facilitated meeting project timelines. This functionality allowed most of the app development to precede the interviews which were delayed (i.e., due to central IRB and subcontracting negotiation). The use of a content management system also allows us, even with limited programming expertise, to makes changes to the app content without the developers’ intervention as other advances in biomedical prevention emerge.

Given the strong pilot data from the group-based intervention and our rigorous mobile adaptation process, MyPEEPS Mobile is innovative, novel, and scientifically sound. Further research will be conducted to rigorously evaluate the efficacy of the MyPEEPS mobile app as well as the collection of app usage data to better understand the effectiveness of mobile technology for the delivery of behavioral health interventions. The future trial will be the first to test the efficacy of a scaled-up, mobile version of an existing HIV prevention intervention originally developed for, designed by, and piloted for, a diverse group of YMSM.

Finally, this paper describes an iterative and comprehensive adaptation process which can be applied more broadly for behavioral interventions delivered via a mobile platform. There is also a more specific opportunity for taking the MyPEEPS intervention to other audiences (eg. women of color at risk for HIV). There is some content that is universal and perhaps wouldn’t require change or adaptation; there is other that would require minimal adaptation, e.g. photos, scenario changes; and then there is other content that would require a full overhaul. This underscores that that once the mobile adaptation process is followed, future adaptations can be simpler in the mobile space than in person.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our expert panel who provided invaluable feedback in the development of the MyPEEPS app: Bobbie Berkowitz, PhD, RN, FAAN; David Breland, MD, MPH; Tri Do, MPH, MD; Geri Donenberg, PhD; Lisa Hightow-Weidman, MPH, MD; Errol Fields, MD, MPH, PhD; Jose Bauermeister, PhD and Harlan Pruden. Special thanks for Kyle Bullock for assistance with interview data coding and app editing and Steven Houang for assisting with final edits to the app.

Funding Information

This study is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under Award Number U01MD011279. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. HIV among gay and bisexual men. 2017a; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/msm/cdc-hiv-msm.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2018.

- 2.CDC. HIV surveillance report, 2016. 2017b; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 3.CDC. HIV and youth. 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/age/youth/cdc-hiv-youth.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- 4.CDC. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidalgo MA, Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Johnson AK, Mustanski B, Garofalo R. The MyPEEPS randomized controlled trial: A pilot of preliminary efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of a group-level, HIV risk reduction intervention for young men who have sex with men. Archives of sexual behavior. 2015;44(2):475–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donenberg G, Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry’s role in a changing epidemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):728–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandura A Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bird JD, LaSala MC, Hidalgo MA, Kuhns LM, Garofalo R. “I had to go to the streets to get love”: Pathways from parental rejection to HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. Journal of homosexuality. 2017;64(3):321–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidalgo MA, Cotten C, Johnson A, Kuhns LM, Garofalo R. ‘Yes, I am more than just that,’:Gay/bisexual young men residing in the United States discuss the influenceof minority stress on their sexual risk behavior prior to HIV infection. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2013;25(4):291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balaji A, Bowles K, Le B, et al. High HIV incidence and prevalence and associated risk factors among young MSM, 2008. AIDS. 2013;27:269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hidalgo M, Kuhns L, Hotton A, Johnson A, Mustanski B, Garofalo R. The MyPEEPS Randomized Controlled Trial: A Pilot of Preliminary Efficacy, Feasibility, and Acceptability of a Group-Level, HIV Risk Reduction Intervention for Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):475–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teens Lenhart A., Social Media< & Technology Overview, 2015.: Pew Charitable Trust;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalani C, Philbrick W, Fraser H, Mechael P, Israelski DM. mHealth for HIV Treatment & Prevention: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Open AIDS J. 2013;7:17–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devi BR, Syed-Abdul S, Kumar A, et al. mHealth: An updated systematic review with a focus on HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis long term management using mobile phones. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122(2):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnall R, Travers J, Rojas M, Carballo-Dieguez A. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention in high-risk men who have sex with men: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bull S, Pratte K, Whitesell N, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Effects of an Internet-based intervention for HIV prevention: the Youthnet trials. AIDS and behavior. 2009;13(3):474–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markham CM, Shegog R, Leonard AD, Bui TC, Paul ME. +CLICK: harnessing web-based training to reduce secondary transmission among HIV-positive youth. AIDS care. 2009;21(5):622–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guse K, Levine D, Martins S, et al. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2012;51(6):535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan B, Lee Y, Rodriguez M, Tiase V, Schnall R. A comparison of usability factors of four mobile devices for accessing healthcare information by adolescents. Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(4):356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnall R, Rojas M, Bakken S, et al. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health (mHealth) applications (apps). J Biomed Inform. 2016;60:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnall R, Bakken S, Rojas M, Travers J, Carballo-Dieguez A. mHealth Technology as a Persuasive Tool for Treatment, Care and Management of Persons Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2015;19 Suppl 2:81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiasson M, Parsons J, Tesoriero J, Carballo-Dieguez A, Hirshfield S, Remien R. HIV behavioral research online. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(1):73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pequegnat W, Rosser BR, Bowen AM, et al. Conducting Internet-based HIV/STD prevention survey research: considerations in design and evaluation. AIDS and behavior. 2007;11(4):505–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stall R, van Griensven F. New directions in research regarding prevention for positive individuals: questions raised by the Seropositive Urban Men’s Intervention Trial. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 1:S123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosser BR, Oakes JM, Horvath KJ, Konstan JA, Danilenko GP, Peterson JL. HIV sexual risk behavior by men who use the Internet to seek sex with men: results of the Men’s INTernet Sex Study-II (MINTS-II). AIDS and behavior. 2009;13(3):488–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA, Parsons JT. Effects of a peer-led behavioral intervention to reduce HIV transmission and promote serostatus disclosure among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 1:S99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pachankis J, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub S, Parsons J. Developing an online health intervention for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behavior. 2013;17(9):2986–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnall R, Cimino JJ, Bakken S. Development of a Prototype Continuity of Care Record with Context-Specific Links to Meet the Information Needs of Case Managers for Persons Living with HIV. International journal of medical informatics. 2012;81(8):549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyun S, Johnson SB, Stetson PD, Bakken S. Development and evaluation of nursing user interface screens using multiple methods. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(6):1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon P, Camhi E, Hesse R, et al. Processes and outcomes of developing a continuity of care document for use as a personal health record by people living with HIV/AIDS in New York City. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012;81(10):e63–e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]