Abstract

Objective:

Although Indigenous women are exposed to high rates of risk factors for perinatal mental health problems, the magnitude of their risk is not known. This lack of data impedes the development of appropriate screening and treatment protocols, as well as the proper allocation of resources for Indigenous women. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to compare rates of perinatal mental health problems among Indigenous and non-Indigenous women.

Methods:

We searched Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science from their inceptions until February 2019. Studies were included if they assessed mental health in Indigenous women during pregnancy and/or up to 12 months postpartum.

Results:

Twenty-six articles met study inclusion criteria and 21 were eligible for meta-analysis. Indigenous identity was associated with higher odds of mental health problems (odds ratio [OR] 1.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25 to 2.11). Odds were higher still when analyses were restricted to problems of greater severity (OR 1.95; 95% CI, 1.21 to 3.16) and young Indigenous women (OR 1.86; 95% CI, 1.51 to 2.28).

Conclusion:

Indigenous women are at increased risk of mental health problems during the perinatal period, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance misuse. However, resiliency among Indigenous women, cultural teachings, and methodological issues may be affecting estimates. Future research should utilize more representative samples, adapt and validate diagnostic and symptom measures for Indigenous groups, and engage Indigenous actors, leaders, and related allies to help improve the accuracy of estimates, as well as the well-being of Indigenous mothers, their families, and future generations.

Trial Registration:

PROSPERO-CRD42018108638.

Keywords: Aboriginal health, common mental disorders, Indigenous people, pregnancy, postpartum

Abstract

Objectif :

Bien que les femmes autochtones soient exposées à des taux élevés de facteurs de risque de problèmes de santé mentale périnatale, l’ampleur de leur risque n’est pas connue. Ce manque de données entrave le développement de protocoles de dépistage et de traitement appropriés, ainsi que la juste allocation de ressources aux femmes autochtones. Cette revue systématique et cette méta-analyse avaient pour objectif de comparer les taux des problèmes de santé mentale périnatale chez les femmes autochtones et non autochtones.

Méthodes :

Nous avons recherché les bases de données Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, et Web of Science depuis leur création jusqu’à février 2019. Les études étaient incluses si elles évaluaient la santé mentale des femmes autochtones durant leur grossesse et/ou jusqu’à 12 mois du postpartum.

Résultats :

Vingt-six articles satisfaisaient aux critères d’inclusion des études et 21 étaient admissibles à la méta-analyse. L’identité autochtone était associée à des probabilités plus élevées de problèmes de santé mentale (RC 1,62; IC à 95% 1,25 à 2,11). Les probabilités demeuraient plus élevées quand les analyses étaient restreintes à des problèmes de plus grande gravité (RC 1,95; IC à 95% 1,21 à 3,16), et à de jeunes femmes autochtones (RC 1,86; IC à 95% 1,51 à 2,28).

Conclusion :

Les femmes autochtones sont à risque accru d’éprouver des problèmes de santé mentale durant la période périnatale, particulièrement la dépression, l’anxiété et l’abus de substances. Cependant, la résilience chez les femmes autochtones, les enseignements culturels, et les questions méthodologiques peuvent influer sur les estimations. La future recherche devrait utiliser des échantillons plus représentatifs, adapter et valider les mesures des diagnostics et des symptômes pour les groupes autochtones, et recruter des acteurs et des leaders autochtones et des alliés connexes pour aider à améliorer l’exactitude des estimations ainsi que le bien-être des mères autochtones, de leurs familles et des générations futures.

Enregistrement de l’essai :

PROSPERO-CRD42018108638

Introduction

Up to 20% of women experience problems with their mental health during the perinatal period,1 with adverse effects for the mother, her family, and the health-care system.2-4 A past history of mental illness,5 poor social support,6 poverty,7 intimate partner violence,8 childhood sexual abuse,9 and other forms of trauma all increase risk.

One group that experiences very high rates of these and other risk factors are Indigenous women. Despite this, very little is known about their mental health during the perinatal period.10 Indigenous populations are the original inhabitants of ancestral land prior to the establishment of borders with cultural identities distinct from the dominant society’s.11 However, because of colonization and assimilation efforts, they now live with structural risks that have contributed to poorer health outcomes than their non-Indigenous counterparts.12

Although not all Indigenous women develop perinatal mental health problems, it is important to understand the mental health problems experienced by Indigenous women around the world so that those who may be suffering can be helped and the intergenerational transmission of risk to their children can be reduced. Resilience processes can also be examined in Indigenous women and their children who are thriving, so protective factors against the development of mental health problems can be elucidated. By understanding the scope of the problem facing Indigenous women and their families, we will then be able to better prioritize and study the relevant risk and resilience mechanisms through which perinatal mental health problems may be transmitted. Synthesizing the literature on Indigenous perinatal mental health should ultimately lead to the development of early screening, identification, and treatment protocols and help guide the development of policies to help future generations.

Bowen and colleagues conducted a systematic search and narrative summary of the literature (up to 2010) on the perinatal mental health of Indigenous women, identifying 16 quantitative articles.13 Thirteen measured perinatal depression and reported antenatal prevalence rates from 17% to 47%. Although this review advanced our understanding of perinatal depression among Indigenous women, a number of gaps remain. Point estimates of absolute and relative risks are not yet known, and some of the studies that provided prevalence data were designed to validate questionnaires rather than estimate these rates, potentially introducing sampling bias.

It is also not known how country of residence, severity of illness, or other factors affect the risk of developing psychopathology among Indigenous perinatal women. It is important to know which mental health problems Indigenous women are most vulnerable to, so that appropriate screening and intervention protocols can be developed and applied (e.g., pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments, public health policies, etc.). Screening and intervention can allow for earlier detection and potentially the prevention of intergenerational transmission of psychopathology to help reduce the burden on the mother, her family, and the health-care system. Finally, little data exist on outcomes other than depression although problems like perinatal substance misuse and anxiety are significant risk factors.14,15

Since the review of Bowen and colleagues synthesized data published nearly a decade ago, accompanied with the increasing appreciation of the importance of the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples and the impact perinatal mental health problems can have on future generations, it is important to have a comprehensive and contemporary understanding of the prevalence and relative risk of these difficulties among Indigenous women.16,17 The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine rates of perinatal mental health problems among Indigenous women from the first trimester of pregnancy up to 12 months postpartum and compare them to non-Indigenous women.

Methods

Search Strategy

The study protocol guiding this systematic review and meta-analysis was published in the PROSPERO database on October 11, 2018 (CRD42018108638). The guidelines and checklists from the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) and meta-analyses and meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) were followed.18,19 Indigenous collaborators of Mohawk (AJ), Red River Métis (CG), and Oji/Cree (BD) heritage were consulted to help create search strategies, plan the subgroup and sensitivity analyses, analyze and interpret the data, and review the final draft of the manuscript.

A systematic search of electronic databases (Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science) was conducted from their inceptions until February 25, 2019. Search strategies/terms were developed in collaboration with a health sciences librarian and clinicians/researchers of Mohawk, Red River Métis, and Oji/Cree heritage to ensure terms were specific and inclusive (please see Supplemental Material data). In general, searches were centered on three Medical Subject Heading terms: Indigenous populations, pregnancy or postpartum period, and mental disorders. Despite terms to describe Indigenous populations being changed over time, we elected to generate all possible terms in order to best capture all potential articles related to perinatal Indigenous mental health. The ancestry approach was also used, where the reference lists of relevant articles were hand-searched to identify additional studies.

Eligibility Criteria

Observational (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort) studies were included if (1) participants were Indigenous women (as defined by World Health Organization20 or other valid criteria [i.e., self-identification]21), (2) participants were assessed anywhere from the start of pregnancy to 12 months postpartum, (3) mental health outcomes were assessed, (4) studies used diagnostic interviews or self-report questionnaires to measure mental health outcomes, and (5) outcomes were reported separately for Indigenous and non-Indigenous women. Although diagnostic manuals have defined the perinatal period to last from the first trimester of pregnancy until 4 weeks postpartum, we elected to extend this time period up to 12 months postpartum to align with clinical practice of diagnosing women with mental health problems if they experience them within a year of delivery.22 All mental health outcomes that had a nonorganic cause and were indexed under “mental health disorders” on the databases (“mental disease” for Embase) were included. For an exhaustive list, please see the Supplemental Material data. All efforts were made to find the English translation of non-English articles.

Data Extraction and Methodological Bias Assessment of Studies

Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (MF and SO) and any disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer (RV). Data were extracted using a standardized form which was pilot-tested with five randomly selected studies to ensure adequate data capture. Information regarding study location was extracted, as were study design, sample size and type, participant inclusion/exclusion criteria, mental health outcomes assessed, measures and clinical cutoffs used, timing of outcome assessment, and prevalence rates.

The methodological bias of eligible studies was assessed using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case–control studies.23 Selection, comparability, and outcome bias were graded using this measure’s star system, where the greater the number of stars represented higher methodological quality and lower risk of bias. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots generated through RevMan 5.3 and the Egger test.

Statistical Analyses

A random effects meta-analysis was conducted. Odds ratios (ORs) were expressed with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Cochrane Q test was performed to assess for statistical heterogeneity, and Higgins I 2 statistic was used to determine the extent of variation between effect estimates (0% to 100%).

In accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook, when needed, study groups were combined so that only two distinct groups (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) were present.24 It is important to note that Indigenous groups within and outside country borders have unique cultural histories, social structures, and lived experiences. Combining these heterogenous groups into a single group could mask any differential effects between and within Indigenous groups. However, we elected to study Indigenous women as a whole as it increased statistical power and since there was limited information on certain Indigenous groups within the searched databases (e.g., Métis women).

Our primary analysis meta-analyzed all eligible studies. Planned subgroup analyses were then conducted to examine the influence of a specific type of mental health problem (e.g., depression, anxiety), reproductive stage (pregnancy, postpartum), and country of residence. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to assess the impact of risk of bias (excluding studies with a score ≤ 4 on the NOS). Research has also shown that young maternal age is a risk factor for the development or recurrence of perinatal mental health problems.25,26 Since Indigenous mothers tend to be younger than their non-Indigenous counterparts,27 we conducted a sensitivity analysis that only included studies reporting that Indigenous participants were younger than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine how different clinical cutoffs defining illness severity affected prevalence rates since different ethnicities may have different thresholds for presenting symptoms of mental health problems.28 RevMan 5.3 and R 3.4.2 Software (R Development Core Team) were used to complete statistical analyses.

Search Results

Our search identified 4,583 potentially relevant articles, and 3,941 underwent title and abstract screening (after removal of duplicate citations). We identified 41 articles for full-text review and found 23 that met our inclusion criteria. Three additional articles were identified via the ancestry approach. Inter-rater agreement was high (Cohen κ = 0.86).

Of these 26 studies, 21 were eligible for meta-analysis (see Figure 1). Tables 1a, b, and c, outline the characteristics of studies during antenatal, postnatal, and combined antenatal/postnatal periods, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart displaying the number of articles identified, screened, deemed eligible, and included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1a.

Characteristics of Antenatal (Pregnancy) Studies.

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Indigenous Group (n) | Comparison Group(s), (n) | Mental Health Outcomes | Time Point | Measure(s) | Effect Estimates: Indigenous vs. Comparison | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns et al., 2006, Australia50,51 | Retrospective case–control | Indigenous (9,018) (n = 8,935 for alcohol use) |

Australian-born (297,649) (n = 297,140 for alcohol use) |

(a) Illicit drug use (b) Alcohol usea |

Pregnancy | ICD-10-AM | (a) 6.0% vs. 1.4% (b) 0.8% vs. 0.1% |

Low |

| Signal et al., 2017, New Zealand29 | Cross-sectional | Maori (406) | Non-Maori (738) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Antenatal anxiety |

35 to 37 weeks gestation | (a) EPDS (≥13) (b) EPDS—Anxiety subscale (≥6) |

(a) 22.4% vs. 15.3% (b) 25.1% vs. 20.1% |

Low |

| Buist and Bilszta, 2005, Australia35 | Cross-sectional | Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander (611) | Non-Aboriginal (39,722)b | Antenatal depression | 16 to 33 weeks gestation | EPDS (≥13) | 19.0% | Low |

| Gavin et al., 2011, United States32 | Prospective cohort | Asian/Pacific Islanders (273) | Non-Hispanic White (1,372), Latina (202), Black (150) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Antenatal panic disorder |

27.4 weeks gestation (average) | (a) PHQ-15 (b) PHQ-15 panic disorder |

(a) 5.9% vs. 5.1% (b) 1.1% vs. 3.5% |

Low |

| Dodgson et al., 2014, United States 41 | Retrospective case–control | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander with PTSD (55) | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander without PTSD (91) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Antenatal PTSD |

Second trimester | (a) CES-D (≥16) (b) Primary care PTSD screen (≥2) |

(a) 31.7% (b) 37.7% |

Low |

| Bowen et al., 2008, Canada39,52 | Cross-sectional | Aboriginal (256) (n = 255 for antenatal anxiety) | Non-Aboriginal (134) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Antenatal anxietyc (c) Antenatal alcohol use (d) Antenatal drug use |

15.2 weeks gestation (average) | (a) EPDS (≥13) (b) EPDS Qs—#3-5 (c) Current drinker (d) Current drug user |

(a) 32.0% vs. 26.9% (b) SMD = 0.00, SE = 0.15 (c) 13.3% vs. 6.7% (d) 23.5% vs. 8.1% |

High |

| Morland et al., 2007, United States53 | Prospective cohort | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (39) | Asian (40), Caucasian (21), Other (1) | Antenatal PTSD | First trimester | Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire + PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version | 24.0% vs. 14.8% | High |

| Shah et al., 2011, Canada and Pakistan40 | Cross-sectional | Aboriginal (128) | Pakistani (128), Canadian Caucasians (128) | Antenatal depression | First, second, or third trimester |

EPDS (≥13) | 31.3% vs. 27.7% | High |

| Goebert et al., 2007, United States30 | Prospective cohort | Native Hawaiian (24) | Asian (39), Caucasian (21) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Antenatal anxiety (c) Antenatal alcohol use |

Pregnancy | (a) CES-D (≥16) (b) STAI (≥40) (c) TWEAK (≥2) |

(a) 41.7% vs. 33.3% (b) 29.2% vs. 26.7% (c) 9.0% vs. 15.0% |

High |

| Mah et al., 2017, Australia54 | Prospective cohort | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (147) | N/A | Antenatal PTSD | First trimester | Impact of Event Scale–Revised | 10.2% | High |

Table 1b.

Characteristics of Postnatal Studies.

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Indigenous Group (n) | Comparison Group(s), (n) | Mental Health Outcomes | Time Point | Measure(s) | Effect Estimates: Indigenous vs. Comparison | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al., 2018, United States47 | Prospective cohort | Asian/Pacific Islander (463) | White (838), Hispanic (985), Black (724) | Postnatal depression | 3.9 months postpartum (average) | PRAMS-3D | 16.8% vs. 16.8% | Low |

| Liu et al., 2016, United States44 | Prospective cohort | Asian/Pacific Islander (516) | White (799), Hispanic (596), Black (464) | Postnatal depression | 9.3 weeks postpartum (average) | Two items from PHQ (depression and loss of interest) | 7.6% vs. 9.5% | Low |

| Abbott and Williams, 2006, New Zealand36 | Prospective cohort | Samoan (646), Tongan (285), Cook Islands Maori (227), Niuean (59), Other Pacific (47) | Non-Pacific (99) | Postnatal depression | 6 weeks postpartum | EPDS (≥13) | 16.1% vs. 21.2% | Low |

| Hayes et al., 2010, United States 45 | Prospective cohort | Hawaiian (1,549), Other Pacific Islander (278), Samoan (165) | Filipino (1,394), White (1,345), Japanese (830), Chinese (775), Korean (340), Black (147), Hispanic (117), Other Asian (110), Other (101) | Postnatal depression | Early postpartum | Two items from PHQ (depression and loss of interest) | 47.2% vs. 44.1% | High |

| Roberson et al., 2016, United States46 | Prospective cohort | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (20,851) | White (12,813), Filipina (9,922), Japanese (5,191), Other Asian (4,034), Other (2,880) | Postnatal depression |

3 to 4 months postpartum (average) | Hawaii PRAMS Depression Scale (≥10) | 9.4% vs. 8.8% |

High |

| Stock et al., 2013, Australia34 | Cross-sectional | Indigenous (3) | Non-Indigenous (197) | Postnatal depression | 3.6 months postpartum (average) | EPDS (≥13) | 66.7% vs. 15.2% | High |

| Wei et al., 2008, United States48 | Cross-sectional | Lumbee Tribe (305) | African-American (142), Hispanic (81), White (51), Non-Hispanic Other (7) | Postnatal depression | 6 weeks postpartum | PDSS (≥60) | 29.2% vs. 20.7% | High |

| Huang et al., 2007, United States42 | Prospective cohort | American Indian (267), Asian and Pacific Islander (37) | Non-Hispanic White (3,918), Non-Hispanic Black (1,274), Hispanics (1,246), Non-Hispanic Asians (918) | Postnatal depression | 6 to 12 months postpartum | CES-D | 47.4% vs. 41.5% | High |

| Wang et al., 2003, China and Taiwan49 | Cross-sectional | Aborigines—Pingtung County (99) | Taiwanese (210), Chinese (196) | Postnatal depression |

6 weeks postpartum | BDI (≥10) | 59.6% vs. 35.0% | High |

| Sugarman et al., 1994, United States43 | Cross-sectional | American Indian (444) | Black (3,849), White (3,489) | Postnatal depression | Up to 1 year postpartum | CES-D (≥16) | 32.0% vs. 27.9% | High |

| Webster et al., 1994, New Zealand38 | Cross-sectional | Maori (42) | European (163) | Postnatal depression | 4 weeks postpartum | EPDS (≥13) | 14.3% vs. 6.1% | High |

| Onoye et al., 2009, United States31 | Prospective cohort | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (22) | Asian (20), Caucasian (12) | (a) Postnatal depression (b) Postnatal PTSD (c) Postnatal anxiety (d) Postnatal alcohol use |

4 to 8 weeks postpartum | (a) CES-D (≥16) (b) Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire + PTSD Checklist–Civilian (c) STAI (≥40) (d) TWEAK (≥2) |

(a) 31.8% vs. 15.6% (b) 4.5% vs. 0% (c) 31.8% vs. 12.5% (d) 9.1% vs. 15.6% |

High |

Table 1c.

Characteristics of Combined Antenatal and Postnatal Studies.

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Indigenous Group (n) | Comparison Group(s), (n) | Mental Health Outcomes | Time Point | Measure(s) | Effect Estimates: Indigenous vs. Comparison | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becares and Atatoa, 2016, New Zealand37 | Prospective cohort | Maori (1,260), Pacific Islander (1,029) | European (3,265), Asian (1,051) | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Postnatal depression |

Third trimester of pregnancy (average) 9 months postpartum |

(a) EPDS (≥13) (b) EPDS (≥13) |

(a) 24.5% vs. 12.2% (b) 16.0% vs. 8.4% |

Low |

| Hayes et al., 2010, Australia33 | Prospective cohort | Torres Strait Islander (92) | N/A | (a) Antenatal depression (b) Postnatal depression (c) Antenatal drug use (d) Antenatal alcohol use |

Pregnancy to postpartum (anytime) | (a) EPDS (≥13) (b) EPDS (≥13) (c) and (d) Demographic psychosocial assessment form |

(a) 37.8% (b) 14.1% (c) 15.0% (d) 18.5% |

High |

If the study used specific cutoffs to define a mental health problem, they are provided in parentheses under the column “Measurement(s).” BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ICD-10-AM = International Classification of Diseases Version 10 Australian Modification; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; N/A = not applicable; PDSS = Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; PRAMS-3D = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System-3 Depression questions; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; SE = standard error; SMD = standardized mean difference; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TWEAK = Tolerance, Worry, Eye-opener, Amnesia, & Cut-down drinking.

a Antenatal alcohol use was an outcome reported in a separate paper (also by Burns et al., 2006), but since both studies contained the same participants, we placed all outcomes together.

b Number of non-Aboriginal women who were depressed was not reported in the study.

c Antenatal anxiety was an outcome reported in a separate paper (also by Bowen et al., 2008), but since both studies contained the same participants, we placed all outcomes together.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Participant characteristics

A total of 444,672 perinatal women were included across the 26 studies, with 39,734 women identifying as Indigenous and 404,938 as non-Indigenous.

Study characteristics

Studies were conducted in the United States (n = 12), Australia (n = 6), New Zealand (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), and Taiwan (n = 1). Twelve studies sampled women during pregnancy, 12 during the postpartum period, and two during pregnancy and the puerperium.

Some studies assessed more than one outcome in their sample.29-32 Twenty-one studies assessed depression with nine using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),29,33-40 five using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D),30,31,41–43 two using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2),44,45 two using a unique depression screening instrument designed for that study,46,47 and one study each using the PHQ-15,32 Postpartum Depression Screening Scale,48 and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).49 Six studies measured alcohol and drug use, with two studies using diagnostic interviews,50,51 two using the Tolerance, Worry, Eye-Opener, Amnesia, & Cut-Down Drinking Questionnaire,30,31 and two relied on self-reports of use.33,39 Four studies measured anxiety with two using the EPDS Anxiety subscale,29,52 while two utilized the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) State subscale.30,31 Four studies assessed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with two studies using both the Traumatic Life Events and PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version,31,53 one using the Primary Care PTSD Screen,41 and one the Impact of Events–Revised Scale.54 Finally, one study measured panic disorder using the PHQ-15 Panic module.32

The studies that were not eligible for meta-analysis either had no comparison group33,35,41,54 or reported only continuous outcomes.52 We completed a narrative synthesis of the results of these studies.

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Of 26 studies, 16 were rated as having a high risk of bias (score ≤ 4 on the NOS—please see Table S1 in Supplemental Material data). This was most frequently due to sample selection bias (i.e., ascertainment of exposure) and outcome measurement bias.

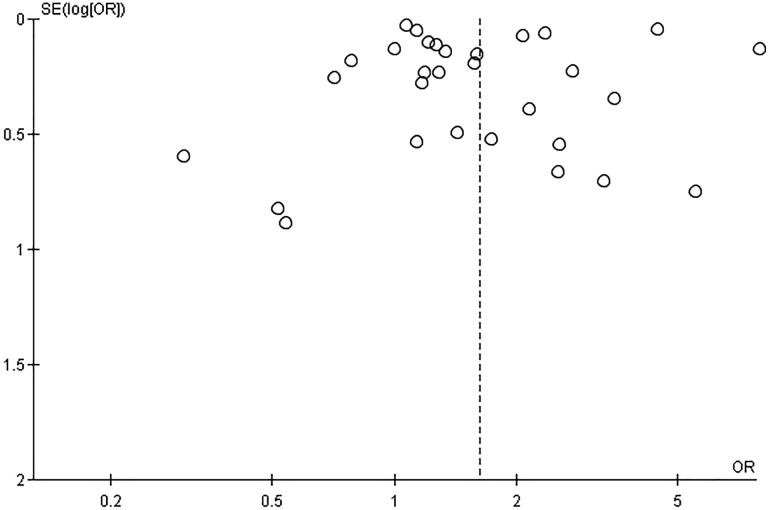

Publication Bias

The symmetrical pattern of the funnel plot formed around the OR of 1.7 is not suggestive of publication bias (see Figure 2). Further, formal statistical tests (i.e., Egger test) suggest that symmetry exists in the funnel plot (P = 0.79) and also supports an absence of publication bias.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot with a symmetrical pattern and an effect estimate about 1.7, suggesting an absence of publication bias.

Primary Analysis

When all types of mental health problems were considered, Indigenous identity was associated with 62% higher odds of experiencing such a problem than non-Indigenous women (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.11; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perinatal mental problem among Indigenous and non-Indigenous women by type of problem.

Subgroup Analyses

Type of mental health problem

Drug or alcohol use problems had the highest OR of all problems (OR 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02 to 5.40; Figure 3), followed by depression (OR 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.65) and anxiety (OR 1.37; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.80). ORs for PTSD were not higher in Indigenous than non-Indigenous women but were based on just two studies. Indigenous women were less likely to have panic disorder (OR 0.30; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.97), although this is only based on a single study.

Reproductive stage

Indigenous women were found to be at elevated risk of developing mental health problems during pregnancy (OR 1.79; 95% CI, 1.23 to 2.59) and the postpartum period (OR 1.34; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.60).

Country of study

In every country (Canada, United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Taiwan), Indigenous women manifested increased odds of any mental health problem relative to non-Indigenous women.

Sensitivity Analyses

Methodological risk of bias

Including only studies with a low risk of bias produced a comparable effect estimate (OR 1.59; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.44) to our primary analysis containing all eligible studies (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.11).

Younger Indigenous participants

When analyses were restricted to only studies that reported Indigenous perinatal participants were younger than their non-Indigenous counterparts, the size of the OR for Indigenous women increased to 1.86 (95% CI, 1.51 to 2.28).

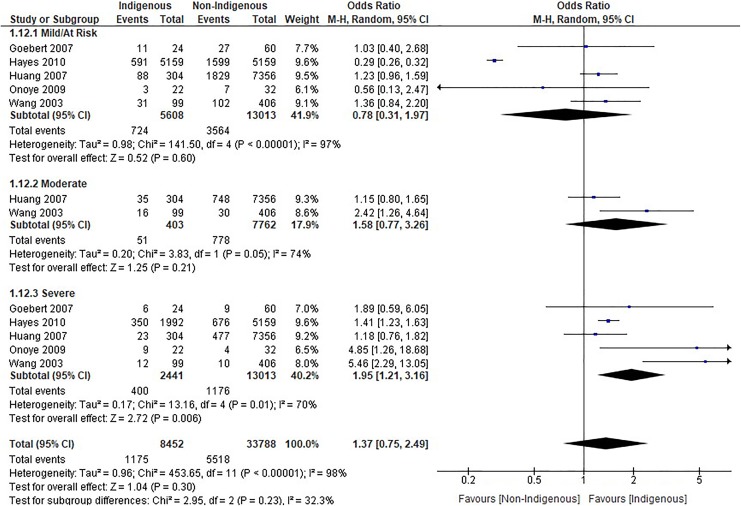

Severity of illness

Five studies categorized their participants according to varying levels of severity of mental health problem (i.e., at risk/mild, moderate, severe; Figure 4). The odds of mild perinatal mental health problems among Indigenous women were not increased (OR 1.78; 95% CI, 0.31 to 1.97), nor were they when studies examined problems of moderate severity (OR 1.58; 95% CI, 0.77 to 3.26). However, Indigenous women were nearly twice as likely to manifest a severe mental health problem (OR 1.95; 95% CI, 1.21 to 3.16).

Figure 4.

Perinatal mental problem among Indigenous and non-Indigenous women by severity.

Narrative Synthesis

Antenatal drug or alcohol use

Hayes et al. (2010) found that 15.0% and 18.5% of Indigenous women self-reported any drug and alcohol use, respectively, during pregnancy.33 For context, antenatal drug and alcohol use among the general pregnant population ranges from 3.7% to 4.3% and 5.4% to 11.6%, respectively.55

Antenatal depression

Three of the five studies not eligible for meta-analysis reported data on prevalence rates of antenatal depression among Indigenous women from the United States41 and Australia.33,35 Hayes et al followed a group of 92 women who identified as Torres Strait Islanders and found that 37.8% of these women reported antenatal depression using the EPDS.33 Dodgson et al. (2014) examined Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander women with and without antenatal PTSD and found antenatal depression prevalence rates of 31.7% among all women using the CES-D.41 Finally, Buist and Bilszta (2005) conducted a cross-sectional study with 611 antenatal women identifying as Aboriginal Strait Islanders and found that 19% of them endorsed symptoms of antenatal depression through the EPDS.35

Antenatal anxiety

Bowen et al. (2008) conducted a prospective cohort study with 389 pregnant women from Canada (255 identifying as Aboriginal) and found no significant differences in antenatal anxiety between the two groups using the EPDS Anxiety subscale.52

Antenatal PTSD

Mah and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study with 147 antenatal women from Australia identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and reported antenatal PTSD prevalence rates of 10.2% using the Impact of Events Scale–Revised.54 Dodgson et al. (2014) found antenatal PTSD prevalence rates at 37.7% using the Primary Care PTSD Screen.41 In the general perinatal population, antenatal PTSD rates are 3.3%.56

Postnatal depression

Hayes et al. (2010) reported that 14% of their sample expressed postnatal depressive symptoms, as assessed by an EPDS score ≥ 13.33

Overall, rates for depression and PTSD were similar to ones reported in the meta-analysis while anxiety rates were higher in the meta-analyzed studies, and drug/alcohol use rates were lower in studies contained in our meta-analysis.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that Indigenous women are at increased risk of mental health problems across the perinatal period, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance misuse. When analyses are limited to higher levels of symptoms and younger Indigenous perinatal women, odds in Indigenous women are higher still.

These findings are consistent with a recent Canadian study (that was not eligible for this review) that showed that postpartum depression rates were higher in First Nations (12.9%), Inuit (10.6%), and Métis (9.1%) women compared to their non-Indigenous peers (5.6%).57 Using the same data, another group reported that Indigenous women were twice as likely to have postpartum depression compared to their non-Indigenous peers (OR 2.11; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.09).58

However, previous meta-analyses on the mental health of Indigenous males and females of a wide range of ages living in the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand suggested that the prevalence of mental health problems is generally not increased relative to non-Indigenous groups, and in some cases, may even be lower.59,60 These findings have been hypothesized to be due to the resiliency and cultural teachings of Indigenous peoples. Despite colonization and its ongoing effects, assimilation efforts, and current systematic racism hindering their quality of life, Indigenous peoples across the globe have shown profound resilience, particularly because of connectedness to traditional land and culture.59,61 In fact, studies have shown that the more involved a community is with their culture (e.g., cultural facilities, self-governance), the lower the suicide rate in that community.62

Indigenous peoples have faced unique social origins of mental health problems including a collective history of forced displacement, colonization, and dissolution of traditional family units (e.g., Indian Residential Schools, Sixties Scoop, Stolen Generation), combined with present-day systematic oppression, racism, forced evacuation birthing for Indigenous women living in remote and Northern areas of Canada, and high rates of intimate partner violence (up to 45 times more than their non-Indigenous counterparts).63-65 Given these numerous structural disadvantages, it may be surprising that our reported rates of mental health problems are not higher.

The reasons for discrepancies between what might be expected based on high rates of exposure to adversities and reported risks of mental health problems are not well understood. Of relevance to perinatal psychopathology, in some Indigenous spiritualities, pregnancy is viewed as a sacred journey and gift from the Creator.66 During this time, women are taught to honor their traditional teachings and immerse themselves in positive and good thoughts as these are a medicine for herself and her baby.67 Therefore, perinatal Indigenous women may receive a greater level of support from their communities during this time which may, in part, protect against the development or recurrence of perinatal mental health problems.

Certainly, this review suggests that Indigenous women are at increased risk of psychopathology in the perinatal period. However, subgroup and sensitivity analyses suggest that rates may actually be even higher. Our sensitivity analysis showed that the odds were even higher in young Indigenous mothers (OR 1.86; 95% CI, 1.51 to 2.28) relative to when all Indigenous women were included (OR 1.62; 95% CI, 1.25 to 2.11). Regardless, methodological limitations present in many extant studies particularly limitations in sampling, measurement, and Indigenous engagement may affect the size of detected effects.

Indeed, 18 of the 26 studies eligible for this review employed convenience sampling to recruit participants and most studies were small and enrolled participants mainly recruited from tertiary care centers, potentially limiting the representativeness of their samples. A number of other studies specifically recruited women who were socioeconomically disadvantaged as control participants, potentially leading to overestimates of mental health problems in non-Indigenous comparison groups.39,40,48,52

Limitations in existing measures, particularly their lack of cultural validity, could also affect effect estimates. Of the 26 studies, 24 reviewed used self-report measures, mainly questionnaires that have not been validated in Indigenous women (i.e., BDI, STAI, CES-D, or PHQ). The expression of poor mental health can vary from culture to culture. For instance, research has shown that some Indigenous groups may express depression as anger or somatic symptoms.68 Using measurements normed primarily in Caucasian groups runs the risk of underestimating the prevalence of perinatal mental health problems in Indigenous women. Further, the scales used in the studies have not been formally validated in Indigenous teenagers despite research showing that Indigenous mothers tend to be younger and more likely to be teenagers.27 To our knowledge, there are no validation studies for these scales (e.g., BDI, CES-D, EPDS, PHQ, STAI) conducted exclusively in Indigenous teenagers. This further limits our interpretation of the data, as symptom expression and illness severity may be different in teenagers compared to their older counterparts. Even questionnaires that have been previously validated may have limitations as these validation studies were completed using small samples and showed only poor predictive validity for mental health problems in Indigenous women.69-72 Just two studies in this meta-analysis utilized structured diagnostic interviews, the gold standard for assessing psychiatric disorders. Consistent with our subgroup analyses relating to disorder severity, the two studies that utilized structured diagnostic interviews reported some of the highest ORs seen in this review (removing these two studies from the meta-analysis reduces the magnitude of our overall effect estimate from 1.62 [95% CI, 1.25 to 2.11] to 1.41 [95% CI, 1.20 to 1.66]). These findings suggest that mental health problems endorsed by Indigenous women may be better detected through clinical interviews and questionnaires that have been culturally validated and adapted.73,74 Although no structured diagnostic interview (i.e., The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders) has specifically been validated in Indigenous populations, studies have highlighted the cultural acceptability with these structured73 or semistructured interviews.74

A lack of Indigenous consultation and collaboration in included studies is another factor that could affect the size of effect estimates. Indeed, only 5 of the 26 studies employed Indigenous research methodologies29,33 or had Indigenous research team members that interacted with participants.36,42,54 Working with Indigenous researchers, clinicians, actors, and leaders would promote the inclusion of appropriate measurements, outcomes, and methodological design in such studies. For example, while no studies specifically examined Inuit women, it is well-known that pregnant women living in Northern and remote locations in Canada must be evacuated (by themselves) to a larger city in order to deliver their baby.75 Research has elucidated the isolation, depression, and loss of control that these new mothers face without their family and friends nearby.75 Such negative birthing experiences certainly contribute to poor maternal mental health, yet were not highlighted in any of the studies in our review. Actively seeking and involving Inuit actors and leaders from study inception may circumvent such methodological problems in future research. Further, given past medical research atrocities involving Indigenous groups, participants may not have been as open or trusting of non-Indigenous researchers which may have led to decreased reporting of problems overall (including those relating to mental health). Relatedly, Indigenous women who have greater trust in Western settler researchers may have been more likely to participate and been healthier, which contributed to underestimates in prevalence rates.76,77

Future Directions

To develop accurate estimates of Indigenous perinatal mental health problems, future research should aim to address methodological issues surrounding sampling, measurement, and Indigenous inclusion, as described earlier. Such research will help optimize screening processes, the proper allocation of resources, and elucidate the risk and resilience processes in Indigenous perinatal women and their families.

First, studies must aim to recruit representative samples. While convenience sampling is simpler, it can introduce biases that can lead to inaccurate estimates. The use of weighted samples can ensure that typically underrepresented populations (e.g., Métis women, women living on-reserve/reservation) are appropriately represented. In Canada, most of the research in the field has focused on First Nations and Inuit, or generically, in Indigenous peoples compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. There is also a need for disaggregated data when studying Indigenous populations, something that has been called a topic of primary importance by the United Nations Permanent Forum.21 Disaggregated data, which break down data into its component parts (e.g., sex, race, geographical district), are often lacking or even nonexistent in Indigenous research, yet it can increase the utility and employment of data collection in different communities which are governed by different jurisdictions, health-care systems, and cultures.21

Second, we propose that structured diagnostic interviews be adapted and validated to be culturally relevant and safe for Indigenous women to assess psychiatric problems. Cultural adaptation can include (a) capturing problems which may be specific to Indigenous peoples (i.e., wounded spirit), (b) asking about symptoms that may be endorsed differently (e.g., depression endorsed as anger), (c) understanding the social origins of mental health (e.g., forced geographic displacement, colonization, dissolution of traditional family units), or (d) employing methods guided by Indigenous knowledge, such as storytelling in clinical interviews.76,78 Given that the administration of diagnostic interviews comes with many barriers (i.e., must be done by a trained and qualified professional, time-consuming, often conducted in-person), questionnaires must concurrently be adapted and validated so that accurate prevalence rates can be estimated in an efficient, barrier-free manner.

Third, Indigenous researchers, collaborators, communities, and related allies need to be involved in all stages of projects examining perinatal mental health problems in Indigenous women. Research groups working with First Nations should employ research standards that adhere to the ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) principle, which provide First Nations with OCAP of the data being collected.79 Employing the “nothing about us without us” principle will provide these communities with the empowerment, capacity, and resources to make changes that can benefit their own community members and future generations.21,80

Limitations

In addition to limitations in sampling, measurement, and Indigenous inclusion, limitations of studies included in the review warrant mention. First, over half (16/26) were assessed to have a high risk of methodological bias. Second, none of the studies sampled women living on-reserve/reservation, which limits our full understanding of the prevalence of perinatal mental health problems among Indigenous women. Third, some studies had a small sample of Indigenous women and thus were not adequately powered to detect differences in their primary outcome. Fourth, gray literature was not searched. Finally, we were not able to report adjusted ORs as 15 of the included studies failed to adjust for risk factors between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women.

Conclusion

The present review suggests that Indigenous identity increases the risk of developing a perinatal mental health problem by 62%. In order to most accurately detect and treat perinatal mental health problems in Indigenous women, future studies must utilize representative samples, adapt and validate assessment methods to establish cultural equivalency, and engage Indigenous communities and allies under the OCAP research standard to reduce the impact of mental health problems on women, their children, and future generations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, CINAHL_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Embase_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Medline_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, PsycINFO_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_tables_2a_and_2b for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Web_of_Science_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jo-Anne Petropoulos for her help in reviewing the search strategies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Sawayra Owais, MSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3966-1215

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3966-1215

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(2):139G–149G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, Iemmi V, Adelaja B. The costs of perinatal mental health problems. London (UK): Centre for Mental Health and London School of Economics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khazaie H, Ghadami MR, Knight DC, Emamian F, Tahmasian M. Insomnia treatment in the third trimester of pregnancy reduces postpartum depression symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):901–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Posmontier B. Sleep quality in women with and without postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(6):722–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chmielowska M, Fuhr DC. Intimate partner violence and mental ill health among global populations of Indigenous women: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):689–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi KW, Sikkema KJ, Vythilingum B, et al. Maternal childhood trauma, postpartum depression, and infant outcomes: avoidant affective processing as a potential mechanism. J Affect Disord. 2017;211:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson SE, Wilson K. The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:93–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Indigenous Populations. World Health Organization. 2019. [accessed December 7, 2018]. https://www.who.int/topics/health_services_indigenous/en/.

- 12. Phillips-Beck W, Sinclair S, Campbell R, et al. Early-life origins of disparities in chronic diseases among Indigenous youth: pathways to recovering health disparities from intergenerational trauma. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(1):115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowen A, Duncan V, Peacock S, et al. Mood and anxiety problems in perinatal Indigenous women in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States: a critical review of the literature. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(1):93–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibberd AJ, Simpson JM, Jones J, Williams R, Stanley F, Eades SJ. A large proportion of poor birth outcomes among Aboriginal Western Australians are attributable to smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, and assault. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaplan SD, Lanier AP, Merritt RK, Siegel PZ. Prevalence of tobacco use among Alaska natives: a review. Prev Med. 1997;26(4):460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Government Commits $4.7B to Indigenous Funding in 2018 Budget. Ottawa, Canada: CTV News; 2018. [accessed January 9, 2019]. https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/government-commits-4-7b-to-indigenous-funding-in-2018-budget-1.3821350. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Message from Dr. Carrie Bourassa: IIPH moves to the University of Saskatchewan. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; September 7, 2018. [accessed January 9, 2019]. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51138.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. United Nations. Indigenous Peoples at the UN; c2019. [accessed January 24, 2019]. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/about-us.html.

- 21. United Nations. Data and indicators. Data collection and disaggregation for Indigenous Peoples; 2019. [accessed January 24, 2019]. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/mandated-areas1/data-and-indicators.html.

- 22. O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2019. [accessed December 3, 2019]. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JPT, Green S. (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org.

- 25. Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, Zlotnick C. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(4):357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Field T. Prenatal depression risk factors, developmental effects and interventions: a review. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2017;4(1):301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boulet V, Badets N. Early motherhood among off-reserve First Nations, Métis and Inuit women. Statistics Canada. 2017. [accessed July 2, 2019] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2017001/article/54877-eng.htm.

- 28. Chiu M. Ethnic differences in mental health and race-based data collection. Healthc Q. 2017;20(3):6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Signal TL, Paine SJ, Sweeney B, et al. The prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety, and the level of life stress and worry in New Zealand Māori and non-Māori women in late pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(2):168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goebert D, Morland L, Frattarelli L, Onoye J, Matsu C. Mental health during pregnancy: a study comparing Asian, Caucasian and Native Hawaiian women. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(3):249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Onoye JM, Goebert D, Morland L, Matsu C, Wright T. PTSD and postpartum mental health in a sample of Caucasian, Asian, and Pacific Islander women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(6):393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gavin AR, Melville JL, Rue T, Guo Y, Dina KT, Katon WJ. Racial differences in the prevalence of antenatal depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hayes BA, Campbell A, Buckby B, Geia LK, Egan ME. The interface of mental and emotional health and pregnancy in urban indigenous women: research in progress. Infant Ment Health J. 2010;31(3):277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stock A, Chin L, Babl FE, Bevan CA, Donath S, Jordan B. Postnatal depression in mothers bringing infants to the emergency department. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buist A, Bilszta J. The beyondblue national postnatal depression program; 2005:p. 1–108. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/8.-perinatal-documents/bw0075-report-beyondblue-national-research-program-vol2.pdf?sfvrsn=2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36. Abbott MW, Williams MM. Postnatal depressive symptoms among Pacific mothers in Auckland: prevalence and risk factors. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(3):230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Becares L., Atatoa-Carr P. The association between maternal and partner experienced racial discrimination and prenatal perceived stress, prenatal and postnatal depression: findings from the growing up in New Zealand cohort study. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Webster ML, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Werry JS. Postnatal depression in a community cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1994;28(1):42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bowen A, Stewart N, Baetz M, Muhajarine N. Antenatal depression in socially high-risk women in Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(5):414–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shah SMA, Bowen A, Afridi I, Nowshad G, Muhajarine N. Prevalence of antenatal depression: comparison between Pakistani and Canadian women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(3):242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dodgson JE, Oneha MF, Choi M. A socioecological predication model of posttraumatic stress disorder in low-income, high-risk prenatal native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59(5):494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(3):257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sugarman JR, Brenneman G, LaRoque W, Warren CW, Goldberg HI. The urban American Indian oversample in the 1988 national maternal and infant health survey. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(2):243–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu CH, Giallo R, Doan SN, Seidman LJ, Tronick E. Racial and ethnic differences in prenatal life stress and postpartum depression symptoms. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hayes DK, Ta VM, Hurwitz EL, Mitchell-Box KM, Fuddy LJ. Disparities in self-reported postpartum depression among Asian, Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Women in Hawaii: pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 2004-2007. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roberson EK, Hurwitz EL, Li D, Cooney RV, Katz AR, Collier AC. Depression, anxiety, and pharmacotherapy around the time of pregnancy in Hawaii. Int J Behav Med. 2016;23(4, SI):515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu CH, Phan J, Yasui M, Doan S. Prenatal life events, maternal employment, and postpartum depression across a diverse population in New York city. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(4):410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei G, Greaver LB, Marson SM, Herndon CH, Rogers J; Robeson Healthcare Corporation. Postpartum depression: racial differences and ethnic disparities in a tri-racial and bi-ethnic population. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(6):699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang S, Jiang Y, Jan W, Chen C. A comparative study of postnatal depression and its predictors in Taiwan and mainland China. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burns L, Mattick RP, Cooke M. The use of record linkage to examine illicit drug use in pregnancy. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2006;101(6):873–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Burns L, Mattick RP, Cooke M. Use of record linkage to examine alcohol use in pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(4):642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bowen A, Bowen R, Maslany G, Muhajarine N. Anxiety in a socially high-risk sample of pregnant women in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(7):435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Morland L, Goebert D, Onoye J, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and pregnancy health: preliminary update and implications. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(4):304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mah B, Weatherall L, Burrows J, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in pregnant Australian Indigenous women residing in rural and remote New South Wales: a cross-sectional descriptive study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(5):520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chapman SLC, Wu LT. Postpartum substance use and depressive symptoms: a review. Women Health. 2013;53(5):479–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:634–645. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nelson C, Lawford KM, Otterman V, Darling EK. Mental health indicators among pregnant Aboriginal women in Canada: results from the Maternity Experiences Survey. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(7-8):269–276 [Article in English, French; Abstract available in French from the publisher]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Daoud N, O’Brien K, O’Campo P, et al. Postpartum depression prevalence and risk factors among Indigenous, non-Indigenous and immigrant women in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(4):440–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kisely S, Alichniewicz KK, Black EB, Siskind D, Spurling G, Toombs M. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in indigenous people of the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:137–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Black E, Kisely S, Alichniewicz K, Toombs M. Mood and anxiety disorders in Australia and New Zealand’s indigenous populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hatala AR, Pearl T, Bird-Naytowhow K, Judge A, Sjoblom E, Liebenberg L. . “I Have Strong Hopes for the Future”: Time orientations and resilience among Canadian Indigenous Youth. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(9):1330–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kirmayer L, Simpson C, Cargo M. Healing traditions: culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australas Psychiatry. 2003;11(s1):S15–S23. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(3):320–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Questions and Answers about Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Australian Human Rights Commission; December 14, 2012. [accessed January 24, 2019]. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/questions-and-answers-about-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-peoples [Google Scholar]

- 65. Petchkovsky L, Roque CS, Jurra RN, et al. Indigenous maps of subjectivity and attacks on linking: forced separation and its psychiatric sequelae in Australia’s stolen generation. Aust E J Adv Ment Health. 2004;3(3):113–128. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ontario’s Maternal Newborn and Early Child Development Resource Centre. Beginning Journey: First Nations Pregnancy Resource; 2013:p. 1–115. https://resources.beststart.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/E33-A.pdf.

- 67. Perinatal Services BC. Our Sacred Journey Aboriginal Pregnancy Passport; 2015:p. 1–37. http://www.perinatalservicesbc.ca/Documents/Resources/Aboriginal/AboriginalPregnancyPassport.pdf.

- 68. Thomas A, Cairney S, Gunthorpe W, Paradies Y, Sayers S. Strong Souls: development and validation of a culturally appropriate tool for assessment of social and emotional well-being in indigenous youth. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Clarke PJ. Validation of two postpartum depression screening scales with a sample of First Nations and Metis women. Can J Nurs Res. 2008;40(1):113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: the traumatic life events questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):210–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lealaiauloto R, Bridgman G. Pacific Island postnatal distress. Auckland, New Zealand: Mental Health Foundation of Aotearoa/New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Heck JL. Screening for postpartum depression in American Indian/Alaska Native women: a comparison of two instruments. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res Online. 2018;25(2):74–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nasir BF, Toombs MR, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, et al. Common mental disorders among Indigenous people living in regional, remote and metropolitan Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6): e020196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Esler D, Johnston F, Thomas D, Davis B. The validity of a depression screening tool modified for use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(4):317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lawford KM, Giles AR, Bourgeault IL. Canada’s evacuation policy for pregnant First Nations women: resignation, resilience, and resistance. Women Birth. 2018;31(6):479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hyett S, Marjerrison S, Gabel C. Improving health research among Indigenous Peoples in Canada. CMAJ. 2018;190(20):E616–E621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. MacDonald NE, Stanwick R, Lynk A. Canada’s shameful history of nutrition research on residential school children: the need for strong medical ethics in Aboriginal health research. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(2):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Caxaj CS. Indigenous storytelling and participatory action research: Allies toward decolonization? Reflections from the Peoples’ International Health Tribunal. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2015;2:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. First Nations Information Governance Centre. Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAPTM): The Path to First Nations Information Governance; May 23, 2014. [accessed January 24, 2019] https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/ocap_path_to_fn_information_governance_en_final.pdf.

- 80. Smylie J, Anderson M. Understanding the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: key methodological and conceptual challenges. CMAJ. 2006;175(6):602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, CINAHL_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Embase_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Medline_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, PsycINFO_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_tables_2a_and_2b for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental Material, Web_of_Science_search_strategy for The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La Santé Mentale Périnatale des Femmes Autochtones: Une Revue Systématique et Une Méta-Analyse by Sawayra Owais, Mateusz Faltyn, Ashley V. D. Johnson, Chelsea Gabel, Bernice Downey, Nick Kates and Ryan J. Van Lieshout in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry