Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive conceptual framework designed to foster research in the changing needs of caregivers and persons with dementia as they move through their illness trajectory. It builds on prior theoretical models and intervention literature in the field, while at the same time addressing notable gaps including inadequate attention to cultural issues; lack of longitudinal research; focus on primary caregivers, almost to the exclusion of the person with dementia and other family members; limited outcome measures; and lack of attention to how the culture of health care systems affects caregivers’ quality of life. The framework emphasizes the intersectionality of caregiving, sociocultural factors, health care systems’ factors, and dementia care needs as they change across time. It provides a template to encourage longitudinal research on reciprocal relationships between caregiver and care recipient because significant changes in the physical and/or mental health status of one member of the dyad will probably affect the physical and/or mental health of the partner. This article offers illustrative research projects employing this framework and concludes with a call to action and invitation to researchers to test components, share feedback, and participate in continued refinement to more quickly advance evidence-based knowledge and practice in the trajectory of dementia caregiving.

Keywords: Dyad, Family, Longitudinal

Approximately 34 million family caregivers (CGs) provide support and often complex unpaid care to an adult age 50 or older experiencing significant and chronic limitations in their cognitive, physical, and/or mental function (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015). The CG role is typically stressful and economically costly, particularly when caregiving involves care recipients (CRs) with significant neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related forms of dementia, resulting in increased mental and physical health problems compared with CGs of persons with other forms of chronic illness (Ory, Hoffman, Yee, Tennstedt, & Schulz, 1999). Although a great deal of research has focused on the trajectory of dementia—how it changes over time, the impact of progressive cognitive impairment on language and function—little has focused on the trajectory of CG experiences. The National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine report on family caregiving (Schulz & Eden, 2016) identified multiple caregiving trajectories to capture the variability of experiences across caregiving situations (e.g., cancer, dementia, etc.) and differences in how caregiving can unfold over time. Given the public health significance of dementia, and the greater burden experienced by dementia CGs (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2017), this article focuses on that particular chronic illness. The purpose of this article is to present a conceptual framework designed to capture the complexity of the dementia caregiving trajectory.

Persons with dementia (PWD) are characterized by progressive declines in cognition and function that typically begin as mild but then progress variably to a point of intense care and supervision. According to the Alzheimer’s Association (2019), 5.8 million Americans currently live with Alzheimer’s disease of which 5.6 million are aged 65 and older, with 80% above age 75. Their CGs provide about 1.8 billion dollars of unpaid care that would otherwise occur in institutional settings. Two-thirds are women, and of these, 34% are age 65 or older and about 25% also care for dependent children. Two-thirds identify as non-Hispanic white, whereas 10% identify as black/African American, 8% as Hispanic/Latinx, and 5% identify with Asian heritage. These CGs are expected to provide physical, emotional, spiritual, financial, and social support to their CRs, mostly on an unpaid basis, for an average of 10 hr/week; many provide care for 40 hr/week or more over a duration of 4–20 years, depending on time of the diagnosis.

Impacts of Dementia Family Caregiving on Physical and Mental Health

Over the past 20 years, the findings from multiple studies with CGs of PWD reveal significant negative health outcomes. Physical health problems include impaired immune function, increased dysregulation of the HPA axis affecting stress hormonal regulation, metabolic disturbances, telomere erosion, low engagement in health maintenance behaviors, and self-reported fair or poor health (Schulz & Eden, 2016; Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003). In terms of emotional distress, multiple studies found increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, frustration, guilt, burden, and/or a general sense of strain, and low subjective well-being (Schulz & Eden, 2016; Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995; Schulz & Sherwood, 2008). Positive benefits from caregiving are also reported (Bell, Livingston, & Patten, 2015; Benz, Tompson, & Willcoxon, 2014). Bertrand and colleagues (2012) noted certain tasks of caregiving (e.g., scheduling, paying bills, managing complex medication regimens) were associated with better memory performance and processing speed when compared with non-CGs. These benefits tended to coexist with reported distress.

Introduction to the Trajectory of Dementia Family Caregiving

All CGs of PWD undertake a range of tasks that vary across the disease trajectory. A stage is used widely in both medical and community settings to describe changes in the progression of AD (the most prevalent type of age-related dementia) and corresponding changes in caregiving demands. AD typically progresses slowly in three general stages with mild symptom profiles indicating early stage, a moderate profile indicating middle stage, and a severe profile indicating late stage. Timing and severity of symptoms vary for each individual. There are also wide individual differences in timing and type of interventions, services, and supports needed based on multiple interacting factors including cultural values and beliefs; CG physical/mental health status; availability of supports; and interactions with health care systems (HCSs).

There is a great deal of interest and enthusiasm at present to study the caregiving process and associated intervention strategies along this trajectory. It is widely recognized that what is effective in early stages may not be appropriate in middle or late stages and vice-versa, though there is little empirically derived information on this topic. Why is this a necessary step in the development of CG intervention research? Because most family caregiving theories are individual focused rather than dyadic or family-centered and lack consideration of the realities of multigenerational caregiving. As such, researchers have limited guidance to study the complexities of context and trajectory and evaluate the comparability of interventions and outcomes across trajectories. This article presents a comprehensive conceptual framework to foster research in the changing needs of CGs and PWD as they move through the illness trajectory. It emphasizes the intersectionality of caregiving, sociocultural factors, HCS factors, and dementia care needs as they change across time, providing a template for longitudinal research in the reciprocal relationship between CG and CR. The article concludes with a call to action and invitation to other researchers to test components, share feedback, and participate in continued refinement of research methods. The overarching goal is to advance evidence-based knowledge and practice in the changing needs of CGs and PWD as they move through the illness trajectory. In the following sections, components of this research framework are explained; selected theoretical models that have guided extant research are reviewed, along with major studies resulting from them; and gaps in existing knowledge are identified that potentially can be addressed.

Key Elements of the Conceptual Framework to Guide Intervention Research Across the Trajectory of Dementia Caregiving

Cultural Context

Culture must be a significant component in the conceptualization and implementation of any framework to describe and explain variations in the inter-relationship of factors involved in CG well-being and function. While dementia caregiving has a substantial body of descriptive literature on CGs’ cultural beliefs and needs (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005; Yeo, Gerdner, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2019), rarely are these juxtaposed to the beliefs and practices of the cultures of various health care systems. The reciprocal is true as well—cultures of health care systems affect CGs as individuals and in turn affect the patient, CG/CR dyad, and the family. In this framework the term culture is used to reflect the broad sociocultural context of families, including their customary beliefs, social forms, and traits of their racial, religious, and social groups (i.e., heritage culture), and the shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices of the health care organizations (i.e., culture of HCS) in which families access services. The term health care systems refers to a wide range of settings and services including outpatient (e.g., primary care physician, specialists); inpatient (e.g., ED visits, unscheduled hospitalizations), short-term (e.g., rehabilitation centers); long-term (e.g., assisted living, nursing homes); community-based (e.g., day care/health centers; respite care; disease-specific support groups), and home-based care (e.g., visiting nurses, occupational therapists, in-home support services).

Heritage culture

The sociocultural context of caregiving was well-described in a classic paper by Aranda and Knight (1997) and more recently by Apesoa-Varano, Tang-Feldman, Reinhard, Choula, and Young (2015). Broadly defined, one’s heritage culture is the backdrop from which caregiving beliefs and practices emanate. Culture encompasses the values, beliefs, and attitudes embraced by CG, CR, and the family. These are integral to one’s identity and shape how roles are structured as well as how dementia is understood, for example, as a neurological disorder versus an imbalance of ying and yang (Dilworth-Anderson & Gibson, 2002; Hinton, Franz, Yeo, & Levkoff, 2005; Sun, Gao, Shen, & Burnette, 2014). It is also key to understanding the extent to which caregiving is seen as a normative part of family life (Meyer, Nguyen, Dao, Vu, Arean, & Hinton, 2015; Polenick et al., 2018). These views in turn can have direct and indirect effects on CG distress and can affect willingness to seek out and engage in interventions (Pharr, Dodge Francis, Terry, & Clark, 2014). For example, many Latinx and Asian groups postpone seeking formal services from HCS and community-based providers until later stages of dementia (Bilbrey et al., 2019). Thus, when the PWD is finally evaluated by the HCS, they are in a more advanced stage where less can be done to improve well-being and reduce behavior problems.

Culture of HCS

It is well-known that hospitals have their own culture of acceptable and unacceptable behaviors (Wilson-Stronks & Galvez, 2007), with certain expectations of CG involvement, including time spent at bedside and participation in or exclusion from care decisions (Ghatak, 2011). Divergent HCS–CG expectations may lead to conflict, especially considering variations across HCSs, for example, how decisions are made (team approach, hierarchical), how complaints/problems are handled, which services are provided, and payment/reimbursement models. CGs must learn to navigate HCSs since it is virtually impossible for PWD to navigate on their own except perhaps in the very early stages. Though the CR spends a significant amount of time in HCSs (e.g., for diagnostics, screenings, health visits, therapies/treatments), the CG is rarely considered an integral part of these teams. Yet CGs manage increasingly complex medical needs and procedures as the health of the CR declines, particularly when other medical comorbidities are present as is usually the case. As Schulz and Czaja (2018) note, to optimize the role of CGs within HCSs requires their identification, assessment and support throughout the trajectory of dementing illness. In these cultural contexts, in addition to dimension noted, stigma may be experienced and play a significant role in how persons and systems interact (Burton, Wang, & Pachankis, 2018). For example, in many cultures, dementia is regarded as a form of mental illness and mental illness is highly stigmatized (Guo, Levy, Hinton, Weitzman, & Levkoff, 2000). Although it is beyond the scope of this article to more fully describe the role that stigma can play in caregiving research, it is a relevant construct for further study.

Trajectory: Early, Middle, and Late Stages

A wealth of stage-specific descriptive information exists for both the PWD and CG although the progression through stages is not strictly linear. In fact, “stages” overlap and the PWD may be at a more advanced point cognitively on their trajectory while socially, they maintain relevant skills and behave appropriately in many situations (Gitlin & Wolff, 2012).

Early stage

Mace and Rabins (2017) note that the initial tasks in early-stage AD for both the CG and the CR align as they obtain and adapt to the realities of the diagnosis and its future implications. Gradually, CGs find themselves assisting with instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., making phone calls to schedule appointments for the PWD; monitoring medication compliance) to support the person as short-term memory loss and mild confusion increase. The PWD–CG dyad faces new demands as they adapt to new knowledge gained from interactions with HCSs, and care coordination and CG role adoption begins. Baseline assessment of the strengths and vulnerabilities of both CG and CR should occur during this stage. Interventions may include providing information and support to smooth role transitions and programs to encourage engagement in positive activities that enhance CG and CR moods (e.g., joining a book or walking club).

Middle stage

CR behavior problems (e.g., wandering, disinhibition, sleep disturbances) manifest and worsen over time and are stressful for CGs to manage (Mace & Rabins, 2017). CGs assume daily care responsibilities for chronic comorbidities (e.g., health care decision making, wound care/nursing-related tasks). The CR’s continued decline in condition can lead to multiple ED visits, hospitalizations, and readmissions. By this time, at least one highly involved CG is identified as a point of contact and is now considered the primary CG. As empirical evidence associates family member involvement with better health outcomes, the primary CG needs to be an integral member of existing care teams, as key interactions or information may otherwise be missed (Wolff & Roter, 2008). At this stage, depressive symptoms and high burden are common (Schulz & Eden, 2016), as are disruptions in the CG/CR relationship, with escalating demands for more varied and complex care effectively reducing positive dyad experiences (Quinn, Clare, & Woods, 2009). Interventions during this phase may include environmental modification, behavior management, and stress reduction programs for CGs and for the dyad, when possible. Also, there is increasing need for other family members to step up and actively participate in caregiving and proactively assist CGs to seek interventions for their own health and well-being.

Late stage

CRs may not recognize their CGs by name, may need help with personal activities (e.g., bathing, dressing, toileting), and eventually may require specialized end-of-life care. Planning for long-term and palliative care becomes necessary. Some PWD are placed in long-term care or other settings outside their family home, posing unique challenges for CGs, such as interacting with facility staff of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. In addition, staff conflicts with family members who are not heavily involved in day-to-day care of the PWD are common (Qualls & Williams, 2013). Finally, with the CR’s diminishing functional capabilities, greater use of formal HCSs occurs. CG stress and burden escalate as personal care tasks increase, along with greater dependence on the family unit, the HCS, and community support networks (as applicable to the CG’s cultural context). Interventions that balance self-care, caregiving tasks, and teach skills for shared decision making with key family members may be useful.

Transition Points

Transition points refer to periods of noticeable shift in need for resources to accommodate the PWD’s changing care needs, for example, moving from one care setting to another. Gitlin and Wolff (2012) first pointed out that the study of trajectories should include transition points in which identified care needs and care settings are included in the research design. Although most current transitional care programs report reductions in CR readmission rates, Gitlin and Wolff note that there is no report on the financial, mental, or physical effects of these transitions or programs on the CG. Studies of when these transition points occur and how HCSs interact with CGs/CRs to enable effective transitions are needed. In fact, these points of need (Kim, Bell, Reed, & Whitney, 2016) provide relevant portals for intervention and present exciting opportunities for further research.

Measurement Issues to Consider in Employing the Conceptual Framework

The success of future intervention research requires research designs that reflect thorough baseline assessments of both CG and CR psychological and physical health. Questionnaires can be used to assess strengths and personal resources, vulnerabilities, subjective physical health, psychological distress, coping styles, sources of support, resilience factors, cultural values and beliefs related to health care, and cognitive function. Family Caregiver Alliance (Feinberg, 2004) published the first comprehensive set of questionnaires to assess CG psychological and social functioning. This fully vetted research inventory—substantially updated in 2012—can be downloaded from: https://www.caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/SelCGAssmtMeas_ResInv_FINAL_12.10.12.pdf (Family Caregiving Alliance, 2012). Although the inventory is comprehensive and an excellent resource for research, there are some limitations. As most of the measures were developed with Caucasian/non-Hispanic CGs, caution should be used when using these measures with minority participants. Of note, some measures have been translated and validated for use with other cultures (e.g., CG self-efficacy scale; Steffen et al., 2018) but mostly that is not the case.

Actual physical health data (e.g., current illnesses, body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol levels) can be collected at in-person clinic visits. Blood and/or urine samples can track biomarkers such as indices of immune suppression and hypothalamic, pituitary, adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction. A recent meta-analysis by Roth and colleagues (2019) notes the inconclusive data on whether there is evidence of inflammation or compromised immunity in family CGs and calls for study of resilience factors that may help explain why some CGs appear stronger and healthier over time, supporting the need for longitudinal research to study these issues in depth. Also crucial is the ability to reevaluate CG and CR on several of these key dimensions over time, and at key transition points, particularly when interventions have been employed in the interim, to evaluate the impact of interventions on multiple outcomes.

Finally, assessment of outcomes should be more specific than in the past when broad indices of distress were used—a fact that may contribute to the relatively modest effect sizes reported in most reviews (Schulz & Eden, 2016). Outcomes that align with the intervention goal should produce stronger effects. For example, if both CG and CR are significantly depressed, an intervention that provides antidepressant medication or targets dysfunctional thoughts and incorporates behavioral activation should affect depression. It will not necessarily affect physical health parameters collected at the same time. If these interventions are part of HCSs, then interactions with that system should be factored into the design. In addition, tailored activity-based programs may encourage greater participation if compatible with the dyad’s cultural background.

Brief Review of Theoretical Models Guiding Most Existing CG Intervention Research

A large number of intervention studies reflecting a variety of theoretical perspectives were conducted in the past few decades, with the goal to improve CG mental and physical health outcomes. The selective review that follows omits contributions from some influential theory builders, such as Bandura (1986a, 1986b) whose delineation of the construct of self-efficacy has influenced caregiving research. However, self-efficacy has primarily been studied as a moderator of outcome—not as an outcome in itself—and a few, if any, studies have considered strengthening self-efficacy as a primary intervention.

Major theories that spawned influential intervention research include the original stress and coping model of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), modified by Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, and Skaff (1990). They added assessment of primary and secondary stressors (e.g., functional limitations of CR and role strain from employment outside the home) as well as psychosocial resources available to CGs to buffer stressors (e.g., personality traits such as optimism and reliable support networks). Examples of evidence-based interventions developed from these stress and coping models include REACH II (Belle et al., 2006), REACH-VA (Nichols, Martindale-Adams, Burns, Zuber, & Graney, 2016), and Savvy Caregiver Program (Hepburn, Lewis, Sherman, & Tornatore, 2003; Samia, Aboueissa, Halloran, & Hepburn, 2014). The sociocultural stress and coping model incorporates these key dimensions plus evaluation of cultural values and beliefs associated with one’s race and/or ethnicity as potential buffers or stressors affecting CG health (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Hilgeman et al., 2009; Knight & Sayegh, 2010; Montoro-Rodriguez & Gallagher-Thompson, 2009). Most extant research based on this model is observational in nature (Hinton, 2010). Qualitative studies with Vietnamese American families (Ta Park et al., 2018), Chinese American families (Sun & Coon, 2019), and Cuban American families (Arguelles & Arguelles-Borge, 2013) can be used to inform future research. Some intervention studies were developed from this model as well, for example, home-based cognitive and behavioral skill training program developed with Chinese Americans incorporates key cultural values (e.g., filial piety and belief in the balance of yin and yang; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2007). The review by Llanque and Enriquez (2012) discusses several other programs (e.g., REACH I, REACH II) that have modified materials for cultural relevance with Latino/Spanish-speaking families.

Lawton, Moss, Kleban, Glicksman, and Rovine (1991) emphasized the importance of measuring CGs’ subjective appraisal of stress. This spawned studies evaluating the value of teaching CGs skills to modify cognitive vulnerabilities (e.g., dysfunctional thoughts), rooted in the cognitive model of depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, and Emery, 1979). An example of an evidence-based intervention program using this model is Coping with Caregiving (CwC; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2000, 2012). CwC teaches skills to modify dysfunctional thinking patterns and increase everyday positive activities through active engagement of CGs in small group discussion and home practice.

Models focused on modifying family dynamics and increasing effective problem-solving among family members have spawned several intervention studies. One example is New York University’s Family Support Program for spousal CGs that provided individual and family counseling plus on-demand telephone support (Gaugler et al., 2016; Mittelman, Ferris, Shulman, Steinberg, & Levin, 1996). Other intervention programs were developed from dyadic theories of change in which reciprocal relationships are studied, with both members of the CG/CR dyad included as intervention targets. One example—Care of Persons with Dementia in their Environment program (COPE; Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, Hodgson, & Hauck, 2010)—uses occupational therapy practices to improve both CG and CR quality of life. Other programs aim to reduce PWD behavioral problems and improve quality of life for both CG and CR. For example, Teri and associates provide a systematic, structured yet individualized approach that teaches CGs to monitor behavior problems, identify events that trigger behaviors, and develop more effective responses (McCurry, Logsdon, Pike, LaFazia, & Teri, 2018; Teri et al., 2003). These protocols improve quality of life of both members of the dyad: when fewer behavior problems are experienced, positive interactions increase and subjective burden decrease. Finally, Schulz and Eden describe an enhanced conceptual model for studying the dementia care trajectory that depicts changes over time in CG roles and responsibilities as the CR declines (2016, p. 77). The conceptual framework presented in this article builds on their work in that greater emphasis is placed on reciprocal interactions among CG/CG dyads and HCSs and on recognition (and measurement) of the impact of cultural factors on CG mental and physical health.

Research Gaps as a Backdrop for Understanding How This Conceptual Framework Can Be Used to Guide to Future Research

The overall state of caregiving intervention research has been critically evaluated and summarized in several recent reviews (Cheng, Au, Losada, Thompson, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2019; Gilhooly et al., 2016; Gitlin, Marx, Stanley, & Hodgson, 2015; Maslow, 2012; Schulz & Eden, 2016). The meta-review by Gilhooly (2016) classified interventions according to focus (e.g., PWD or CG or both), type of program (i.e., psychosocial, psychoeducation, therapy, technological, support groups, multicomponent), and whether benefits were found (e.g., psychological well-being, knowledge and coping skills, institutional delay). They concluded that virtually all interventions had some benefit; benefits varied according to outcomes assessed. However, they note that most studies were short-term and measured only a small set of outcomes. Cheng and colleagues (2019) recently completed meta-analysis of 131 randomized controlled trials published between 2006 and 2018. They classified programs as psychoeducational, counseling/psychotherapy, mindfulness-based programs, support groups, care coordination/case management, CR training with CG involvement, multicomponent programs, and miscellaneous with technology assistance. Again, statistically significant effects were found for virtually all categories; effects varied according to outcome measures used. Effect sizes were small to medium, overall, with psychoeducation and multicomponent the strongest. They also note several limitations: few studies measured whether physical health or social support were actually affected by the program; few studied the impact of cultural values and beliefs; longitudinal research was sorely lacking; and little knowledge of which interventions are most effective for CGs (and PWD) along the continuum of care. These conclusions echo earlier research gaps noted by Apesoa-Varano and colleagues (2015) and Schulz and Eden (2016). These “top 5” gaps provide a backdrop for the framework presented in this article by addressing: diversity and heterogeneity; adopting the longitudinal lens; reflecting CG/CR dyad; incorporating risk and needs assessments; and expanding the scope of outcome measures.

Diversity and Heterogeneity

In addition to the CR illness and the severity of their condition, diversity and heterogeneity requires examining how illness is understood and responded to, considering heritage culture, as highlighted in the framework—particularly with CGs who are first- or second-generation immigrants for whom beliefs and practices regarding chronic illness may differ significantly from those of the dominant culture. For CGs who are not strongly identified with their culture of origin, other diversity markers probably come into play such as religious orientation/spiritual beliefs; gender roles and expectations; sexual identification and orientation; family composition; and socioeconomic status. Research is needed that carefully measures key aspects of diversity and evaluates intervention access, participation, and outcomes.

Longitudinal Lens

At present, little is known about which interventions are best suited to which CGs, and which are most effective at different points along the way. Intervention research with dementia CGs needs to be longitudinal in design, with multiple measurements over an extended period—1 or 2 years is not sufficient; a longitudinal span of at least 10 years is needed to ensure sufficient time for a subset of CGs to experience the trajectory and receive targeted interventions at crucial points of need along the way. Unfortunately, most existing CG intervention research is cross-sectional or includes only short-term follow-up (such as 3–6 months or 1–2 years). The NSOC (National Health and Aging Trends Study, 2019) includes multiple waves of CG interviews; however, the study did not include interventions or their impacts. The full trajectory of caregiving needs to be studied from an intervention perspective. By following multiple families with varying sociocultural characteristics over time, including pivotal transition points as highlighted in the model, valuable information can be gained for interventions that are most beneficial at those points and over time.

Caregiver/Care Recipient Dyad

The dyad should be the unit of study because of the reciprocal effects of one on the other. Although existing data are limited, a handful of studies demonstrate cross-over effects (e.g., changes in one partner affecting the other, in both positive and negative ways). Research with breast cancer dyads (Dorros, Card, Segrin, & Badger, 2010) and heart failure patients and spouses (Trivedi, Piette, Fihn, & Edelman, 2012; Vellone, Chung, Alvaro, Paturzo, & Dellafiore, 2018) found cross-over effects in distress outcomes. In the study by Dorros and colleagues (2010), high levels of depression and stress in women with breast cancer were associated with partners’ lower self-reported health and well-being. Similarly, Trivedi et al. (2016) found that depression in older male heart failure patients was positively correlated with spouse depression and, in turn, correlated with lower patient confidence in heart failure management. A subsequent dyadic-focused intervention on communication skill training supports the conclusion that there is a real, measurable interrelatedness between heart failure patient and spouse distress indices (Vellone et al. 2018). Laver, Milte, Dyer, and Crotty (2017) reviewed the small number of PWD–CG dyadic studies, noting encouraging results and the need for more research. Some argue that the family, whether self-identified or biological, should be the unit of study rather than any one specific CG (Jacobs, Broese van Groenou, Aartsen, & Deeg, 2016; Qualls & Williams, 2013; Spillman, Freedman, Kasper, & Wolff, 2019; Wilmoth & Silverstein, 2017); however, this approach is rare in dementia research.

Risk and Need Assessments

As dyads enter HCSs for dementia evaluation and care, comprehensive baseline evaluation of both CG and CR are needed, with a focus on strengths and vulnerabilities as part of CR risk assessments and CG need assessments. Because caregiving is a dynamic process, these markers and needs will change over time as the CR–CG dyad encounters a variety of HCSs and services, requiring systematic re-assessment to ensure the right interventions provided at the right time along the caregiving trajectory.

Expanded Scope of Outcome Measures

Researchers, family members, and health care providers need to work collaboratively to develop and implement a comprehensive set of measures to evaluate the impact of interventions on physical and mental health in a comprehensive manner. Measures of key HCS characteristics and interactions with CG–CR dyads are also needed to explore ways HCS cultures affect illness progression. In addition, new measures may be needed to appropriately assess social/psychological constructs that may moderate outcomes. Particularly for ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse CGs, existing measures may not adequately capture their experiences. Last, brief and focused measures to capture key markers of stress and decision making at times of transition are needed and should be developed collaboratively with health care providers.

Future Directions for Caregiving Intervention Research Using This Conceptual Framework

In this final section, suggestions of possible research projects are proposed that take into account multiple variables, interactions among them, and diverse sources of measurement. Identification of research barriers to overcome and recommendations are offered to employ the conceptual framework more broadly, including application to other chronic illnesses.

First, future research directions need to include ways to better identify points of need along the trajectory, linking these points to transitions in HCSs, and working with diverse stakeholders to develop culture-friendly interventions to meet those specific needs. An information-gathering phase, using focus group methodology with key stakeholders, would be informative, for example, with questions about the kind of information to deliver to CGs/CRs in early stages, as well as how, when, by whom, and in what setting information are optimally delivered (Sherifali et al., 2018). A novel program—the Support, Health, Activities, Resources and Education program (SHARE; Orsulic-Jeras, Whitlatch, Szabo, Shelton, & Johnson, 2019)—assesses core values of PWD for future care and then facilitates discussion with a trained counselor to build balanced and realistic future care plans. Using the proposed conceptual framework as a guide, this program’s content could be tailored for diverse populations, with additional measures of physical and mental health status collected at baseline to measure change across time. In addition, timing for program delivery could be tailored to dyadic needs, rather than automatically providing it at the point of diagnosis.

As dementia progresses and cognitive and behavioral problems become more frequent and challenging to manage, CGs may benefit from skill-building programs, for example, Coping with Caregiving (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2000, 2012), Savvy Caregiver (Hepburn et al., 2007; Samia, Aboueissa, Halloran, & Hepburn, 2014), COPE (Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, Hodgson, & Hauck, 2010), or one of the REACH derivatives (Belle et al., 2006; Nichols et al., 2016). A novel program developed by Cheng and associates (2017) using techniques for finding benefits in caregiving to enhance positive aspects and build resilience may also be relevant at this stage. Applying the proposed framework to these programs suggests offering the programs in modular formats so CGs can participate in skill trainings at several points along the trajectory as their needs and resources change (e.g., after a difficult hospitalization for hip fracture). Currently, these programs are not structured for that level of flexibility. In addition, if programs are offered in community or hospital settings, opportunities for collaboration with health care providers will be enhanced. Because providers typically focus on the PWD (not the CG), this type of reciprocal engagement will require system-level changes. New intervention programs can be developed to build in flexibility, HCS interaction and collaboration from the outset, using community-based participatory research models to engage diverse stakeholders in the process.

Finally, in later stages, the PWD may need to be placed in a nursing home or other long-term care facility due to their extensive care needs, although some families can and do keep the PWD at home until death despite the hardships involved (Mausbach et al., 2004; McBride, 2019). Placement decisions probably include a combination of CG and CR variables (e.g., severe CG burden; CR immobility; reduced/absent social supports). Interventions will, therefore, vary considerably, depending on cultural values and beliefs, access to hospice and other palliative care services, and extent of personal preparation for impending loss. Using the framework proposed in this article, research can illuminate this process, identifying triggers affecting timing of these decisions. Fruitful research topics and intervention targets include CG needs to support their decision; CG interactions with nursing home staff/administration; CG interactions with family members, including their criticisms as well as preparation for loss, and key sociocultural characteristic variations.

Moving Forward, Research Barriers to Overcome

Several key barriers need to be addressed, so that research in caregiving complexities and intersectionalities can be implemented. First, significant funding is needed to mount innovative longitudinal research focused on CG–CR dyads (including families) and HCS interactions, including specific attention to HCS-level factors that support and promote HCS interactions with CGs. Historically, studies have focused on the CR’s longitudinal decline, in part because their trajectory is more easily defined and measured by biological, cognitive, and behavioral markers. Although CGs have probably been present at medical visits, they are rarely asked to complete assessments about their own health. To address this barrier, HCSs need to incorporate CGs into treatment planning. A major policy shift will take time to accomplish (Schulz & Czaja, 2018), although ratification of the CARE ACT (Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable) in 40 states and territories in just 4 years (Reinhard, Young, Ryan, & Choula, 2019) is a significant step in the right direction. This reflects policy maker recognition of the support family CGs’ need to perform the medical/nursing tasks required following the CR’s discharge from hospital.

Second, the lack of operationalized definitions and standard measurements across multiple research studies and sites remains a challenge, limiting cross-study comparisons. If consensus can be reached on a common set of baseline measures (possibly spearheaded by NIA and NINR), data could be stored in a repository with easy access for cross-site comparisons and opportunities to answer questions about which interventions are most successful for specific outcomes of interest.

Third, many CGs cannot participate in research for practical reasons, especially those whose burden became overwhelming over time, including financial hardship, emotional challenges, or no transportation (Boise, Hinton, Rosen, & Ruhl, 2016). Many historically underrepresented groups such as Latinx, Asian groups, and LGBTQ individuals may have little to no trust of researchers—clearly, these factors limit their participation (Askari, Bilbrey, Garcia Ruiz, Humber, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2018). Targeted outreach to include CGs/CRs of diverse sociocultural and socioeconomic backgrounds is critical to engagement of these disenfranchised groups (Apesoa-Varano et al., 2015).

Conclusions and Call to Action

The authors acknowledge the debt owed to researchers who, for the past 30 plus years, have conducted intervention studies with limited resources. Each project has revealed a piece of the puzzle. Building on this extensive body of literature the proposed conceptual framework offers a comprehensive and well-fleshed-out first step in developing a new theoretical model to guide the study of CR/CG changing needs across illness trajectories, an exceedingly complex area of research. Although the conceptual framework is disease specific, focused on dementia, it may serve as a general template for other diseases, with necessary modifications as required by the specific illness. For example, trajectories in different cancers can be much swifter than in dementia, thus posing unique research challenges.

This work evolved from the family caregiving summit (Harvath et al., 2020) and is closely aligned with the summit research priorities. The goal of the conceptual framework presented here is to guide future research by encouraging colleagues to test components, share their results, and give feedback, so that continual refinements can occur that accurately reflect the real world of caregiving intervention research. In an ideal world—with sufficient funding and without constraints of time and challenges of recruitment—this framework would be tested in its entirety. Meanwhile, it is crucial to learn which components are feasible for study and how these studies can be implemented and evaluated with diverse CGs. There may very well be other key variables as yet unidentified which will be discovered and will illuminate future research. As Zarit (2018) thoughtfully points out, caregiving should be viewed as a developmental process—an idea that is complementary to the research framework presented in this article.

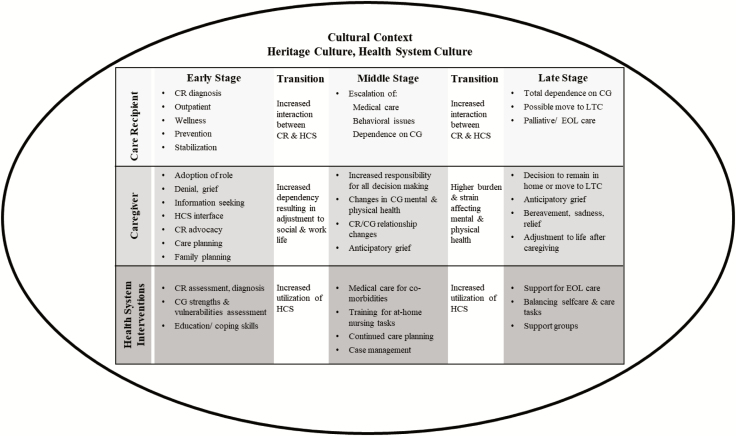

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. This figure illustrates key variables affecting the caregiving dyad as they progress through the trajectory of dementia. It includes transition points as they move from one disease stage to the next. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient; HCS = health care system; LTC = long-term care; EOL = end of life.

Author Notes

We call for family-centered caregiving research, in alignment with the research priorities of the summit discussed earlier; however, definitions of family vary across cultural groups—for example, in the LGBTQ community, families may be constructed rather than biological; in African American families, “fictive kin” who are not blood relatives are part of the family unit; and among Latinx interactions and decision making with extended family, who may live in other states or countries, is common. With the complexity of family definitions, and the likelihood of various definitions across CGs studied, the term “caregiver” is used in this article. Despite limitations of this term, typically, there will be one CG who is the primary point of contact for the PWD. Furthermore, by studying both members of the dyad (encouraged in this framework), knowledge of which interventions are most appropriate for whom, and when, will increase. Clearly, this is not a substitute for family-focused research, but given the current state of the art, and the definitional issues noted, it is a pragmatic decision designed to foster research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ladson Hinton, Department of Psychiatry at UC Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA, for his thoughtful comments on earlier drafts. We also thank faculty and staff of the Family Caregiving Institute at Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, UC Davis, for their insights and support throughout this process. An early draft of this article was presented by invitation at the Research Priorities in Caregiving Summit: Advancing Family-Centered Care Across the Trajectory of Serious Illness, sponsored by the Family Caregiving Institute at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at the University of California–Davis in March 2018.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which established the Family Caregiving Institute at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at University of California–Davis (Grant Agreement #5968). This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored and funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers & Dementia, 15, 321–387. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010 [Google Scholar]

- Apesoa-Varano E. C., Tang-Feldman Y., Reinhard S. C., Choula R., & Young H. M (2015). Multi-cultural caregiving and caregiver interventions: A look back and a call for future action. Generations, 39, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda M. P., & Knight B. G (1997). The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 37, 342–354. doi:10.1093/geront/37.3.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguelles T., & Arguelles-Borge S (2013). Working with Cuban American families. In Yeo G. & Gallagher-Thompson D. (Eds.), Ethnicity and the dementias (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Askari N., Bilbrey A. C., Garcia Ruiz I., Humber M. B., & Gallagher-Thompson D (2018). Dementia awareness campaign in the Latino community: A novel community engagement pilot training program with promotoras. Clinical Gerontologist, 41, 200–208. doi:10.1080/07317115.2017.1398799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1986a). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4, 59–373. doi:10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359 [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1986b). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Rush A. J., Shaw B. F., & Emery G (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J., Livingston G., & Patten E (2015). Family support in graying societies: How Americans, Germans and Italians are coping with an aging population (Vol. 21). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Social & Demographic Trends; Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/21/family-support-in-graying-societies/ [Google Scholar]

- Belle S. H., Burgio L., Burns R., Coon D., Czaja S. J., Gallagher-Thompson D.,…Zhang S.; Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) II Investigators (2006). Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145, 727–738. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz J. K., Tompson T. N., & Willcoxon N (2014). Long-term care in America: Expectations and reality. Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research; Retrieved from https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/project/long-term-care-in-america-expectations-and-reality/ [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand R. M., Saczynski J. S., Mezzacappa C., Hulse M., Ensrud K., & Fredman L (2012). Caregiving and cognitive function in older women: Evidence for the healthy caregiver hypothesis. Journal of Aging and Health, 24, 48–66. doi:10.1177/0898264311421367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbrey A. C., Angel J. L., Humber M. B., Chennapragada L., Garcia-Ruiz I., Kajiyama B., & Gallagher-Thompson D (2019). Working with Mexican American Families. In Yeo G. & Gallagher-Thompson D. (Eds.), Ethnicity and the dementias (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boise L., Hinton L., Rosen H. J., & Ruhl M (2016). Will my soul go to heaven if they take my brain? Beliefs and worries about brain donation among four ethnic groups. The Gerontologist, 57, 719–734. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton C. L., Wang K., & Pachankis J. E (2018). Does getting stigma under the skin make it thinner? Emotion regulation as a stress-contingent mediator of stigma and mental health. Clinical Psychological Science, 6, 590–600. doi:10.1177/2167702618755321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S. T., Au A., Losada A., Thompson L. W., & Gallagher-Thompson D (2019). Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: What we have achieved, what we have learned. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, 59. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1045-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S. T., Mak E. P., Fung H. H., Kwok T., Lee D. T., & Lam L. C (2017). Benefit-finding and effect on caregiver depression: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 521–529. doi:10.1037/ccp0000176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P., & Gibson B. E (2002). The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 16(Suppl 2), S56–S63. doi:10.1097/00002093-200200002-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorros S. M., Card N. A., Segrin C., & Badger T. A (2010). Interdependence in women with breast cancer and their partners: An interindividual model of distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 121–125. doi:10.1037/a0017724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Caregiving Alliance. (2012). Selected caregiver assessment measures: A resource inventory for practitioners (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L. F. (2004). The state of the art: Caregiver assessment in practice settings. San Francisco, CA: Family Caregiver Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D., Gray H., Tang P., Pu C. Y., Leung L. Y., & Wang P. C (2007). Impact of in-home intervention versus telephone support in reducing depression and stress of Chinese caregivers: Results of a pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15, 425–434. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180312028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D., Lovett S., Rose J., McKibbin C., Coon D., Futterman A., & Thompson L. W (2000). Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 6, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D., Tzuang Y. M., Au A., Brodaty H., Charlesworth G., Gupta R...Shyu Y. I (2012). International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: A review. Clinical Gerontologist, 35, 316–355. doi:10.1080/07317115.2012.678190 [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Reese M., & Mittelman M. S (2016). Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on primary subjective stress of adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. The Gerontologist, 56, 461–474. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak R. (2011). A unique support model for dementia patients and their families in a tertiary hospital setting: Description and preliminary data. Clinical Gerontologist, 34, 160–172. doi:10.1080/07317115.2011.539512 [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly K. J., Gilhooly M. L. M., Sullivan M. P., McIntyre A., Wilson L., Harding E...Crutch S (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 106. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. N., Marx K., Stanley I. H., & Hodgson N (2015). Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. The Gerontologist, 55, 210–226. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. N., Winter L., Dennis M. P., Hodgson N., & Hauck W. W (2010). A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: The COPE randomized trial. JAMA, 304, 983–991. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. N., & Wolff J (2012). Family involvement in care transitions of older adults: What do we know and where do we go from here? Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 31, 31–64. doi:10.1891/0198-8794.31.31 [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Levy B. R., Hinton W. L., Weitzman P. F., & Levkoff S. E (2000). The power of labels: Recruiting dementia-afflicted Chinese American elders and their caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 6, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Harvath T. A., Mongoven J. M., Bidwell J., Cothran F. A., Sexson K. E., Mason D. J., Buckwalter K. 2020. Research priorities in family caregiving: Process & outcomes of a conference on family-centered care across the trajectory of serious illness. The Gerontologist, 60(S1), S5–S13. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn K., Lewis M., Tornatore J., Sherman C. W., & Bremer K. L (2007). The Savvy Caregiver program: the demonstrated effectiveness of a transportable dementia caregiver psychoeducation program. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33, 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn K. W., Lewis M., Sherman C. W., & Tornatore J (2003). The savvy caregiver program: Developing and testing a transportable dementia family caregiver training program. The Gerontologist, 43, 908–915. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgeman M. M., Durkin D. W., Sun F., DeCoster J., Allen R. S., Gallagher-Thompson D., & Burgio L. D (2009). Testing a theoretical model of the stress process in Alzheimer’s caregivers with race as a moderator. The Gerontologist, 49, 248–261. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L. (2010). Qualitative research on geriatric mental health: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L., Franz C. E., Yeo G., & Levkoff S. E (2005). Conceptions of dementia in a multiethnic sample of family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53, 1405–1410. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M. T., Broese van Groenou M. I., Aartsen M. J., & Deeg D. J (2016). Diversity in older adults’ care networks: The added value of individual beliefs and social network proximity. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, 326–336. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. K., Bell J. F., Reed S. C., & Whitney R (2016). Coordination at the point of need. In Hesse B., Ahern D., & Beckjord E. (Eds.), Oncology informatics (pp. 81–100). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight B. G., & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 5–13. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver K., Milte R., Dyer S., & Crotty M (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing carer focused and dyadic multicomponent interventions for carers of people with dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 29, 1308–1349. doi:10.1177/0898264316660414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M. P., Moss M., Kleban M. H., Glicksman A., & Rovine M (1991). A two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. Journal of Gerontology, 46, P181–P189. doi:10.1093/geronj/46.4.p181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R., & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Llanque S. M., & Enriquez M (2012). Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: A review of the literature. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 27, 23–32. doi:10.1177/1533317512439794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace N. L., & Rabins P. V (2017). The 36-hour day: A family guide to caring for people who have Alzheimer disease, other dementias, and memory loss. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow K. (2012). Translating innovation to impact: Evidence-based interventions to support people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers at home and in the community. Washington, DC: Administration on Aging and Alliance for Aging Research; Retrieved from https://aoa.acl.gov/AoA_Programs/HPW/Alz_Grants/docs/TranslatingInnovationtoImpactAlzheimersDisease.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach B. T., Coon D. W., Depp C., Rabinowitz Y. G., Wilson-Arias E., Kraemer H. C.,…Gallagher-Thompson D (2004). Ethnicity and time to institutionalization of dementia patients: A comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 1077–1084. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride M. (2019). Working with Filipino families. In Yeo G., Gerdner L., & Gallagher-Thompson D. (Eds.), Ethnicity and the Dementias (3rd ed., pp. 274–292). New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- McCurry S. M., Logsdon R. G., Pike K. C., LaFazia D. M., & Teri L (2018). Training area agencies on aging case managers to improve physical function, mood, and behavior in persons with dementia and caregivers: Examples from the RDAD-Northwest Study. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61, 45–60. doi:10.1080/01634372.2017.1400486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O. L., Nguyen K. H., Dao T. N., Vu P., Arean P., & Hinton L (2015). The sociocultural context of caregiving experiences for Vietnamese dementia family caregivers. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 263–272. doi:10.1037/aap0000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman M. S., Ferris S. H., Shulman E., Steinberg G., & Levin B (1996). A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 276, 1725–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro-Rodriguez J., & Gallagher-Thompson D (2009). The role of resources and appraisals in predicting burden among Latina and non-Hispanic white female caregivers: A test of an expanded socio-cultural model of stress and coping. Aging & Mental Health, 13, 648–658. doi:10.1080/ 13607860802534658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the US 2015. NAC and the AARP Public Institute. Washington DC: Greenwald & Associates. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2017). Dementia caregiving in the U.S. Washington, DC: Greenwald & Associates. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Aging Trends Study. (2019). National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) Retrieved from https://nhats.org/scripts/QuickLinkNSOC.htm

- Nichols L. O., Martindale-Adams J., Burns R., Zuber J., & Graney M. J (2016). REACH VA: Moving from translation to system implementation. The Gerontologist, 56, 135–144. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsulic-Jeras S., Whitlatch C. J., Szabo S. M., Shelton E. G., & Johnson J (2019). The SHARE program for dementia: Implementation of an early-stage dyadic care-planning intervention. Dementia, 18, 360–379. doi:10.1177/1471301216673455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory M. G., Hoffman R. R. 3rd, Yee J. L., Tennstedt S., & Schulz R (1999). Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. The Gerontologist, 39, 177–185. doi:10.1093/geront/39.2.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Mullan J. T., Semple S. J., & Skaff M. M (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharr J. R., Dodge Francis C., Terry C., & Clark M. C (2014). Culture, caregiving, and health: Exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. ISRN Public Health, 2014, 8. doi:10.1155/2014/689826 [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2005). Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 45, 90–106. doi:10.1093/geront/45.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick C. A., Struble L. M., Stanislawski B., Turnwald M., Broderick B., Gitlin L. N., & Kales H. C (2018). “The Filter is Kind of Broken”: Family caregivers’ attributions about behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 548–556. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualls S. H., & Williams A. A (2013). Caregiver family therapy: Empowering families to meet the challenges of aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/13943-000 [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C., Clare L., & Woods B (2009). The impact of the quality of relationship on the experiences and wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 13, 143–154. doi:10.1080/13607860802459799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard S. C., Young H. M., Ryan E., & Choula R. B (2019). The CARE Act implementation: Progress and promise. Spotlight: March 2019. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Roth D. L., Sheehan O. C., Haley W. E., Jenny N. S., Cushman M., & Walston J. D (2019). Is family caregiving associated with inflammation or compromised immunity? A meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 59, e521–e534. doi:10.1093/geront/gnz015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samia L. W., Aboueissa A. M., Halloran J., & Hepburn K (2014). The Maine Savvy Caregiver Project: Translating an evidence-based dementia family caregiver program within the RE-AIM Framework. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 640–661. doi:10.1080/01634372.2013.859201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., & Czaja S. J (2018). Family caregiving: A vision for the future. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 358–363. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., & Eden J. (Eds.). (2016). Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., O’Brien A. T., Bookwala J., & Fleissner K (1995). Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist, 35, 771–791. doi:10.1093/geront/35.6.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., & Sherwood P. R (2008). Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Journal of Social Work Education, 44(Suppl 3), 105–13 doi:10.5175/JSWE.2008.773247702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherifali D., Ali M. U., Ploeg J., Markle-Reid M., Valaitis R., Bartholomew A.,…McAiney C (2018). Impact of internet-based interventions on caregiver mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20, e10668. doi:10.2196/10668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillman B. C., Freedman V. A., Kasper J. D., & Wolff J. L (2019). Change over time in caregiving networks for older adults with and without dementia. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbz065 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen A. M., Gallagher-Thompson D., Arenella K. M., Au A., Cheng S. T., Crespo M...Nogales-González C (2018). Validating the revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy: A cross-national review. The Gerontologist, 59, e325–e342. doi:10.1093/geront/gny004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., & Coon D. W (2019). Working with Chinese American families. In Yeo G., Gerdner L., & Gallagher-Thompson D. (Eds.), Ethnicity and the dementias (3rd ed., pp. 261–273). New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Gao X., Shen H., & Burnette D (2014). Levels and correlates of knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease among older Chinese Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29, 173–183. doi:10.1007/s10823-014-9229-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta Park V., Nguyen K., Tran Y., Yeo G., Tiet Q., Suen J., & Gallagher-Thompson D (2018). Perspectives and insights from Vietnamese American mental health professionals on how to culturally tailor a Vietnamese dementia caregiving program. Clinical Gerontologist, 41, 184–199. doi:10.1080/07317115.2018.1432734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L., Gibbons L. E., McCurry S. M., Logsdon R. G., Buchner D. M., Barlow W. E.,…Larson E. B (2003). Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 290, 2015–2022. doi:10.1001/jama.290.15.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R. B., Piette J., Fihn S. D., & Edelman D (2012). Examining the interrelatedness of patient and spousal stress in heart failure: Conceptual model and pilot data. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 27, 24–32. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182129ce7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R., Slightam C., Fan V. S., Rosland A. M., Nelson K., Timko C.,…Piette J. D (2016). A couples’ based self-management program for heart failure: Results of a feasibility study. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 171. doi:10.3389/fpubh. 2016.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellone E., Chung M. L., Alvaro R., Paturzo M., & Dellafiore F (2018). The influence of mutuality on self-care in heart failure patients and caregivers: A dyadic analysis. Journal of Family Nursing, 24, 563–584. doi:10.1177/10748407 18809484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano P. P., Zhang J., & Scanlan J. M (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 946–972. doi:10.1037/0033-2909. 129.6.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth J. M., & Silverstein M. D. (Eds.). (2017). Later-life social support and service provision in diverse and vulnerable populations: Understanding networks of care. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Stronks A., & Galvez E (2007). Exploring cultural and linguistic services in the Nation’s hospitals: A report of findings. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J. L., & Roter D. L (2008). Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1409–1415. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G., Gerdner L., & Gallagher-Thompson D. (Eds.). (2019). Ethnicity and the dementias, 3rd ed. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S. H. (2018). Past is prologue: How to advance caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 22, 717–722. doi:10.1080/13607863.2017.1328482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]