Abstract

Ischemic stroke remains a serious threat to human life. There are limited effective therapies for the treatment of stroke. We have previously demonstrated that angiogenesis and neurogenesis in the brain play an important role in functional recovery following ischemic stroke. Recent studies indicate that increased arteriogenesis and collateral circulation are determining factors for restoring reperfusion and outcomes of stroke patients. Danshensu, the Salvia miltiorrhiza root extract, is used in treatments of various human ischemic events in traditional Chinese medicine. Its therapeutic mechanism, however, is not well clarified. Due to its proposed effect on angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, we hypothesized that danshensu could benefit stroke recovery through stimulating neurogenesis and collaterogenesis in the post-ischemia brain. Focal ischemic stroke targeting the right sensorimotor cortex was induced in wild-type C57BL6 mice and transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) to label smooth muscle cells of brain arteries. Sodium danshensu (SDS, 700 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 10 min after stroke and once daily until animals were sacrificed. To label proliferating cells, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 50 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered, starting on day 3 after ischemia and continued once daily until sacrifice. At 14 days after stroke, SDS significantly increased the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in the peri-infarct region. SDS-treated animals showed increased number of doublecortin (DCX)-positive cells. Greater numbers of proliferating endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells were detected in SDS-treated mice 21 days after stroke in comparison with vehicle controls. The number of newly formed neurons labeled by NeuN and BrdU antibodies increased in SDS-treated mice 28 days after stroke. SDS significantly increased the newly formed arteries and the diameter of collateral arteries, leading to enhanced local cerebral blood flow recovery after stroke. These results suggest that systemic sodium danshensu treatment shows significant regenerative effects in the post-ischemic brain, which may benefit long-term functional recovery from ischemic stroke.

Keywords: neurogenesis, collaterogenesis, angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, cell migration, danshensu, ischemic stroke

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common causes of human death and a primary cause of disability. However, so far, there are limited effective therapies for the treatment of stroke. Recent research has increasingly focused on therapies improving tissue repair and functional recovery in the post-stroke brain1. Prior studies have shown that cerebral ischemia induces increased proliferation of endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells in the subventricular zone (SVZ), followed by their migration toward the ischemic boundary2–4. Our previous results showed that peripheral whisker stimulation enhanced endogenous neurogenesis, accompanied with increased blood flow restoration in the post-ischemic barrel cortex region5. On the other hand, inhibition of neurogenesis by X-irradiation exacerbated the outcome from cerebral ischemia6, and transgenic ablation of doublecortin (DCX)-expressing cells resulted in increased infarct size and more severe neurologic deficits after focal cerebral ischemia7. Taken together, these studies indicate that neurogenesis may contribute to brain tissue repair after ischemic stroke.

However, it is known that endogenous neurogenesis can be insufficient for effective tissue repair and functional improvements after stroke8. Many newly formed cells die due to multiple injurious mechanisms in the ischemic environment. We propose that long-term survival of these neuroblast and neuronal cells depends heavily on the local blood flow supply. In stroke patient cases, a greater density of cerebral blood vessels in the ischemic border was correlated with increased survival rate9. The growth of new capillaries (angiogenesis) and the growth/remodeling of pre-existing arterioles into physiologically relevant arteries (arteriogenesis) help local perfusion in the ischemic brain and may benefit long-term functional recovery10. This vascular regeneration is likely coupled with neurogenesis in the brain and provides a restorative microenvironment within the ischemic tissue for an improved neurologic function after stroke11–13. Specifically, the most recent clinical data demonstrate that collateral artery and collateral circulation are determining factors for the outcomes of stroke patients. In the DEFUSE-3 clinical trial, patients with richer collateral circulation had a much better prognosis after thrombolysis treatments14. Meanwhile, angiogenic vessels produced trophic factors and cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), that are beneficial and even critical for regenerative repair of damaged brain tissues15–18. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is primarily responsible for generating NO in vascular endothelium. In eNOS−/− mice, the decreased arteriogenesis resulted in more severe neurological functional deficit; an NO donor treatment promoted arteriogenesis, as well as functional outcomes after stroke19. Therefore, we tested a strategy of enhancing vascular regenerative effects by focusing on collaterogenesis as a potential treatment for ischemic stroke.

Danshen, the dried root of Salvia miltiorrhiza, is a popular traditional Chinese medicine and has been widely used in both Asian and Western countries for boosting blood circulation, dilating the coronary arteries and improving blood flow20,21. Danshensu is one of the major active hydrophilic components from Danshen. In animal studies, it has been shown to dilate coronary arteries, inhibit platelet aggregation and improve microcirculation21. Research on Danshen or S. miltiorrhiza and its derivatives, has focused on cardiovascular ischemia and shown pro-angiogenic, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects22–24. A derivative of salvianolic acid B, SMND-309, may have a protective effect in a rat cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury model via activating the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway25. Magnesium lithospermate B, an active component of Danshen, as well as Salviaolate have antioxidant properties in the heart and brain26,27. Salvianolic acid B can attenuate apoptosis and inflammation via sirtulin 1 (Sirt-1) activation in a rat stroke model28. Different components of Danshen were neuroprotective and reduced cerebral infarction in mice29. In a mouse transient ischemic mouse stroke model, salvianolic acid B increased the level of antioxidant substances and decreased free radical production. Salvianolic acid B may exert the neuroprotective effect through a mitochondria-dependent pathway30.

Due to its hydrophilic properties and paracellular absorption–transport pathway, danshensu, from Danshen extracts, has poor intestinal permeability and presumably low permeability through the blood–brain barrier (BBB). On the other hand, sodium danshensu (SDS) showed enhanced oral absorption and demonstrated to pass through the BBB31. Thus, SDS has a greater potential in clinical applications32,33. The present investigation tested the novel hypothesis that systemic administration of SDS could promote neurogenesis and collaterogenesis in the post-stroke brain, thus improving sustained local blood flow and functional recovery after ischemic stroke.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Focal Ischemic Stroke Model of Mice

The investigation was performed in young adult male C57BL/6 mice (20–25 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), and male C57BL/6 mice expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of an of an alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) promoter (Transgenic Mice Facility of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD). Expression of the GFP in smooth muscle cells allows the visualization of brain arteries. Animals were housed at Emory University Animal Facility in standard cages in 12-h/12-h light–dark cycles. All experiments and surgery procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and met the NIH standards.

Focal cerebral ischemia targeting the sensorimotor cortex was induced based on our previously established stroke model 2 Cell Transplantation modified with artery occlusion procedures34. Briefly, anesthesia was induced using 3.5% isoflurane followed by a maintenance dose of 1.5% isoflurane. Both the tail and paws of the animal were pinch-tested for anesthetic depth. The right middle cerebral artery (MCA) was permanently ligated using a 10-0 suture (Surgical Specialties Co., Reading, PA), accompanied by bilateral common carotid artery (CCA) ligations for 7 min. This modified ischemic procedure is suitable and sufficient for the induction of focal ischemia in the mouse cortex, resulting in specific infarct formation in the right sensorimotor cortex. During surgery and recovery periods, body temperature was monitored and maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5 oC using a temperature control unit and heating pad. Sham group received exposure of the dura, but no ligation of the branches35. Animals were sacrificed by decapitation 14–28 days after ischemic stroke. The brain was immediately removed and mounted in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA) at –80 oC for further processing.

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Culture and Neural Induction

Mouse induced pluripotent stem cell–derived neural progenitor cells (iPSC-NPCs) were differentiated from iPSCs originally generated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Stemgent Inc., Cambridge, MA) as previously described36. The pluripotent stem cells and the iPSC-NPCs used in this study were harvested during passages 18 to 25. To maintain the pluripotency of the stem cells, we used an inhibitor cocktail of small molecules with some modifications37. Briefly, iPSCs were cultured in the N2B27 serum free medium at 20% O2, 5% CO2, at 37° C. The medium was prepared with 45% Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium: nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 45% Neurobasal (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ), 0.5% N2 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% GlutaMAX, 1% nonessential amino acids (Sigma Aldrich), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME; Sigma Aldrich), 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich), 5% knockout serum replacement (KSR; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The small molecules were recombinant leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; 10 ng/mL; Millipore, Billerica, MA), CHIR 99021 (3 µM; Tocris), (S)-(+)-Dimethindene maleate (2 µM; Tocris) and minocycline hydrochloride (2 µM; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)37. Before differentiation experiments, the iPSCs were cultured in DMEM (Sigma Aldrich), 10% ES-FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), GlutaMAX, nonessential amino acids, nucleoside mix, LIF, β-ME (Sigma Aldrich), LIF, b-ME, and penicillin/streptomycin. All cells used in this study were harvested and ready for transplantation after an established ‘4−/4+’ retinoic acid (RA, 1 μM; Sigma Aldrich) neural differentiation protocol38.

Sodium Danshensu and 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine Administration

Sodium danshensu (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in saline (0.1% DMSO final concentration). In animal studies, SDS (700 mg/kg) or vehicle solution was administrated by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) 10 min after ischemia and continued once per day after ischemic surgery until sacrifice. To label proliferating cells, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma Aldrich) was administrated to all animals (50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) beginning on day 3 after ischemia and continued once daily until sacrifice.

For cell culture study, sodium danshensu (100 µM) or vehicle solution was added into the culture medium for 8 h on the last day of the designated ‘4−/4+’ RA (1 μM) induction. To label proliferating cells, BrdU (10 µM) was added into the medium 1 h before phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) wash and 10% formalin fixation (Azer Scientific, Morgantown, PA). When analyzing by immunostaining, BrdU was co-stained with Nestin (mouse anti-Nestin; 1:400; Millipore, Burlington, MA). The colabelled BrdU and Nestin cells were counted as newly formed neural progenitor cells.

Sensorimotor Measurement

Adhesive removal test is a sensitive and accurate measurement of the integrity of the sensorimotor pathway involving peripheral sensation to central reception and motor control39. To evaluate sensorimotor function, time for a mouse to remove adhesive pads from both forepaws was measured as previously described40. In brief, a small adhesive dot was placed on one forepaw, and the time needed to contact and remove the sticker from each forepaw was recorded. Mice were trained three times before stroke surgery and the average time was used in data analysis. Animals with response time of more than 120 s were considered insensitive to the tactile stimulus and were excluded from further examinations. Stroke animals usually undergo spontaneous sensorimotor functional recovery during the first 1–2 weeks after stroke. This process is facilitated by repeated functional tests due to activity-dependent neuroplasticity and effects of learning. To detect the SDS effect in a delayed time point, animals were not subjected to multiple tests on different days after stroke (Table 1)41.

Table 1.

Experimental design and sample sizes for in vivo experiments.

| Figure | Experiment | Post-stroke days | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Western | 14 | 6 |

| 3 | DCX/BrdU for neuroblast proliferation | 14 | 6 |

| 3 | NeuN/BrdU for neurogenesis | 28 | 6 |

| 4 | Col IV/BrdU for angiogenesis | 14 | 6 |

| 4,5 | αSMA/BrdU for arteriogenesis | 21 | 5 |

| 6 | GLUT-1/BrdU for angiogenesis | 21 | 6 |

| 6 | Laser Doppler for blood flow | 21 | 6–10 |

| 6 | Adhesive removal test | 21 | 12–16 |

The time points for different assessments after stroke were based on the consideration of the time course of the event. Immature DCX-positive cells and vascular marker Col IV were inspected early (14 day post-stroke) because they label neural progenitor cells and vascular cells during the early stage (within 7–14 days after stroke) of neurogenesis and angiogenesis7,51,71,72, while the delayed time point of 28 days post-stroke was selected for measuring neurogenesis due to the longer time needed for neuronal differentiation of mature neurons (up to 4 weeks) (http://www.functionalneurogenesis.com/blog/tag/timecourse/).

Sample sizes for different groups were chosen based on preliminary studies that were performed with a small group of animals per group (n = 2 for Westerns and immunohistochemistry, and n = 3 for behavior). Using the difference in means (estimate of effect size) determined with the preliminary studies and the sample sizes used, priori power analysis was performed (two tailed, α error probability = 0.05, power (1-β error probability = 0.8) using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2, Universitat Düsseldorf, Germany). Detailed sample sizes for each experimental group are specified in figure legends.

DCX: doublecortin; BrdU: 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; Col IV: collagen IV; GLUT-1: glucose transporter 1; αSMA: alpha smooth muscle actin.

Collateral Arterial Diameter Measurement

The αSMA-GFP mouse was used to visualize the brain arteries. After sacrifice, fresh brains were immediately examined by photographing under the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; green) excitation wavelength at ×4 fluorescent microscopy (BX61; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Photoshop Professional (Adobe Photoshop CS 8.0, San Jose, CA) was used to make an image mosaic. Diameter was measured using the imaging software ImageJ (NIH Image, Bethesda, MD, USA). Six collaterals and six areas of each collateral were measured. The data are presented as average diameter and further compared between the two groups.

Western Blot Analysis

Angiogenic and neurogenic gene expressions were detected at 14–28 days after stroke. This was based on different time courses of angiogenesis and neurogenesis (Table 1). The peri-infarct region was defined as previously described by a 500 µM boundary extending from the edge of the infarct core, medial, and lateral to the infarct42. Tissue samples were taken from the peri-infarct region of the cortex and proteins were extracted by homogenization in protein lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (Sigma Aldrich) (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% SDS, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 100 mM sodium fluoride (NaF), 1% Triton (Sigma Aldrich), leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin). Tissue was centrifuged at 13,000 RPM (16,200 g) for 20 min to pellet insoluble fraction and supernatant was collected. Protein concentration of each sample was determined using the Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Proteins from each sample (50 µg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in a Hoefer Mini-Gel system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and transferred in the Hoefer Transfer Tank (Amersham Biosciences) to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were blocked in 7% evaporated milk diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% tween-20 (TBST) at room temperature for at least 2 h, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary antibodies: VEGF, BDNF, stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), eNOS (1:500–1:4000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Mouse α-tubulin antibody (Sigma) was used for protein loading control. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, membranes were washed with TBST, followed by three washes with TBS. The signal was detected by the addition of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) solution (Sigma), quantified, and analyzed using the imaging software Image J and Photoshop Professional. The intensity of each band was measured and subtracted by the background. The expression ratio of each target protein was then normalized against α-tubulin.

Brain Infarct Measurement

Staining 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma) was performed as previously described43. Briefly, at three days post-stroke, animals in different groups were sacrificed and TTC staining was used to reveal damaged/dead brain tissue. The brain was removed and placed in a brain matrix and then sliced into several 1-mm coronal sections. Slices were incubated in 2% TTC at 37 °C for 5 min, followed by storage in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h. Digital images of the caudal aspect of each slice were obtained by a flatbed scanner. Infarct, ipsilateral hemisphere, and contralateral hemisphere areas were measured using ImageJ software. Infarct volume was calculated using the indirect method.

Immunohistochemistry and Cell Counting

Fresh frozen brains were sliced into coronal sections at 20 μm thickness using a cryostat vibratome (Ultapro 5000, St Louis, MO, USA). Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Whitaker et al., 2007 ). Primary antibodies used for double-staining or triple-staining were as follows: goat anti-collagen IV (1:400; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) for endothelial cells, mouse anti-αSMA for smooth muscle cells (1:1000; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), mouse anti-NeuN (1:400; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) for mature neurons, rat anti-BrdU (1:400; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for cell proliferation, goat anti-doublecortin (anti-DCX; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for migrating neuroblasts, rabbit anti-glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) (1:400, Chemicon, Millipore) for vessels. Secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit, anti-goat, anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), cyanine-3 (Cy3)-conjugated anti-rat, anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen) or Cy5-conjugated anti-goat IgG (1:400; Invitrogen). Hoechst 33342 was applied at a concentration of 1:25,000 for 5 min and washed with PBS. Staining was visualized by fluorescent and confocal microscopy (BX61; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For systematic random sampling in design-based stereological cell counting, six coronal brain sections per mouse were selected, spaced 100 μm apart across the same region of interest in each animal. Coronal sections of 10-μm thickness were used for counting NeuN-labeling cells. For multistage random sampling, six fields per brain section were randomly chosen in the ischemic border region under ×40 magnification of a light microscope or in confocal images. Neurogenesis in the ischemic border region was evaluated by counting the number of NeuN/BrdU-colabeled cells. Angiogenesis in the ischemic border region was evaluated by counting the number of collagen IV/BrdU-colabeled cells. Arteriogenesis in the ischemic border region was evaluated by counting the number of αSMA/BrdU-colabeled cells. Neuroblast migration was evaluated by counting the number of DCX-positive cells in white matter between the SVZ and ischemic cortex. All counting assays were performed under blind conditions.

Local Cerebral Blood Flow Measurement (LCBF)

Laser scanning imaging was used to measure LCBF as previously described44 at three time-points: immediately before ligation, right after occlusion, and 21 days after ischemia. Briefly, under anesthesia, a crossing skin incision was made on the head to expose the whole skull. Laser scanning imaging measurements and analyses were performed using the PeriScans system and LDPIwin (Perimed AB, Stockholm, Sweden) on the intact skull. The scanning region had a center point of medial–lateral (ML) + 4.1 mm, and the six edges of the infarct area were ML + 2.9 mm, ML + 5.3 mm, anterior–posterior (AP) − 1.5 mm, and AP + 2.0 mm, respectively. In laser scanning imaging, the ‘single mode’ with medium resolution was used to scan the photo image of LCBF. The laser beam was pointed to the center of the ischemic core (ML + 4.1 mm, AP 0 mm), the scan range parameter was set up as 5 × 5 and the intensity was adjusted to 7.5–8.0. The conventional ‘duplex mode’ was used to record the Doppler image with the laser beam pointed to exact the same point on the border of the stroke core (ML − 0.5 mm, AP 0 mm). Corresponding areas in the contralateral hemisphere were similarly surveyed as internal controls.

Statistical analysis

Student’s two-tailed t test was used for the comparison of the two experimental groups. Multiple comparisons were done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey test for multiple pairwise examinations. Changes were identified as significant if P was less than 0.05. Mean values were reported together with the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Sodium Danshensu Increased Expression of Trophic Factors and Neurovascular Regulatory Proteins in the Peri-Infarction Cortex

In ischemic stroke mice, SDS (700 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected 10 min after the onset of the ischemic insult. This acute treatment did not show significant reductions in the infarct size measured at 3 days after stroke (23.67 ± 8.36 mm3, n = 6 and 20.29 ± 6.05 mm3, n = 7; P > 0.05, for stroke control and stroke plus SDS, respectively). The present investigation, therefore, focused on chronic effects on regenerative activities on different days after stroke. In the focal ischemic stroke model of the mouse, sham control and stroke animals received vehicle or SDS treatment (700 mg/kg, i.p., 10 min after ischemia and once daily) for 14 days. At 14 days after stroke and SDS or vehicle treatment, Western blot analysis showed that the SDS treatment enhanced the expression of VEGF, BDNF, SDF-1, and eNOS in the perfi-infarct region compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 1A to E).

Fig. 1.

Effects of sodium danshensu on expression of neurovascular regulatory factors.

The protein levels of VEGF, BDNF, SDF-1, and eNOS were detected by Western blot analysis. (A) Representative electrophoresis gels show the expression level of VEGF, BDNF, SDF-1, and eNOS in the ischemic peri-infarct region at 14 days after stroke. (B–E) densitometry analysis for comparisons of each factor. Gray intensity was normalized against tubulin and quantified by Image J software. Sodium danshensu enhanced the expression of VEGF, BDNF, SDF-1, and eNOS when compared with vehicle control group. n = 6 animals for each test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

* P < 0.05 compared with sham group, # P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; SDF-1: stromal-derived factor-1; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; SEM: standard error of the mean.

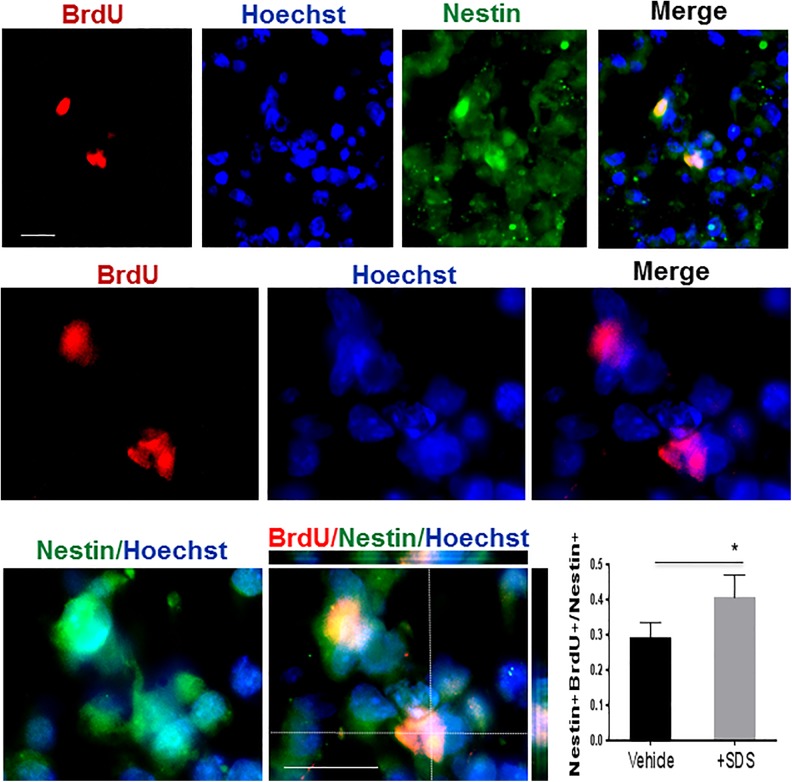

Sodium Danshensu Enhanced Cell Proliferation in Neural Progenitor Cultures and Neurogenesis after Focal Ischemic Stroke

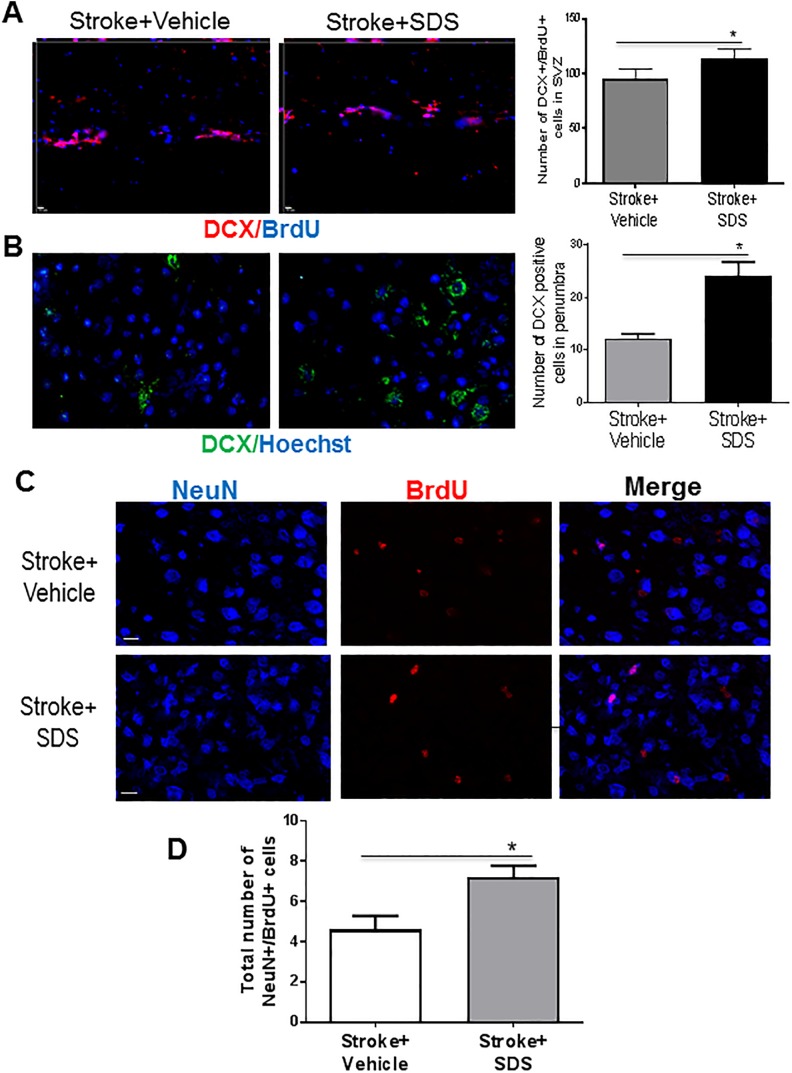

Microtubule-associated protein doublecortin (DCX) is a marker for migrating neuroblasts as well as for endogenous neurogenesis after brain injuries45,46. Testing in mouse iPSC-NPC cultures, SDS (100 μM) significantly increased Nestin and BrdU co-labelled cells (Fig. 2), indicating increased proliferation of neural progenitor cells. In animal experiments of the focal ischemic stroke of the mouse, the SDS treatment of 14 days increased the number of DCX-positive cells in the SVZ and peri-infarct region compared with stroke vehicle groups, supporting increased proliferation of neural progenitor cells in stroke animals (Figs. 3A and 3B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of sodium danshensu on proliferation of neural stem cells.

Proliferation of iPSC-derived neural progenitors cultures were analyzed by immunostaining. Representative image showing the Nestin-expressing and BrdU positive cells of neurospheres upon the end of the 4−/4+ RA induction. Sodium danshensu increased the Nestin and BrdU double-labelled cells when compared with those in the vehicle group. Green: Nestin, red: BrdU and blue: Hoechst 33342. n = 5 assays. Data are shown as mean ± SD. * P < 0.05 compared with the vehicle group. iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell; BrdU: 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; RA: retinoic acid; SD: standard deviation.

Fig. 3.

Doublecortin expression in subventricular zone and ischemic boundary region.

(A) Double labeling for DCX (red) and BrdU (blue) in the SVZ region of vehicle and SDS-treated mice. The total number of both DCX and BrdU positive cells in SVZ of SDS treatment group is more than vehicle control group. (B) More DCX positive cells were found in the boundary region of stroke in SDS treatment group. Green, DCX-positive cells; red, NeuN positive cells. (C, D) SDS enhanced neurogenesis. Neurogenesis in the peri-infarct region was examined by the colocalization of the neuronal marker NeuN (blue) and the proliferation marker BrdU (red) 28 days after stroke (C). In SDS-treated mice, there were more both NeuN- and BrdU-positive cells compared with vehicle control mice. In the bar graph of (D), cell count was performed in six randomly chosen fields in the peri-infarct region; six regions per section. The total number of cells in three sections was summarized for each animal. Cell counts showed increased number of NeuN-/BrdU-positive cells in SDS-treated mice compared with vehicle control mice. n = 6 animals in each group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

* P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. DCX: doublecortin; SVZ: subventricular zone; BrdU: 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; SDS: sodium danshensu; SEM: standard error of the mean.

To verify the proliferation activity, the proliferation marker, BrdU (50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) was injected 3 days after stroke and repeated once a day. At 28 days after stroke, SDS treatment significantly increased the number of NeuN and BrdU co-labeled cells in the peri-infarct region compared with stroke vehicle controls (Figs. 3C and 3D). These results indicated that the SDS treatment promoted neurogenesis in the post-stroke brain.

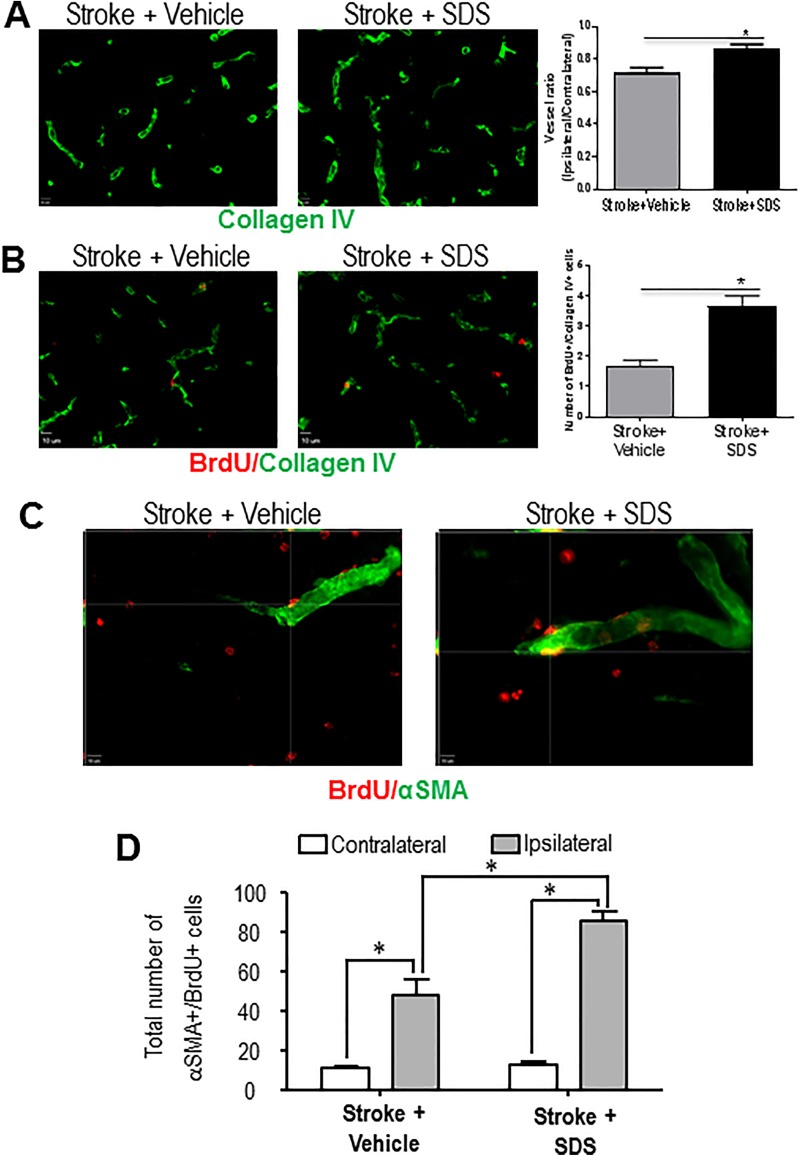

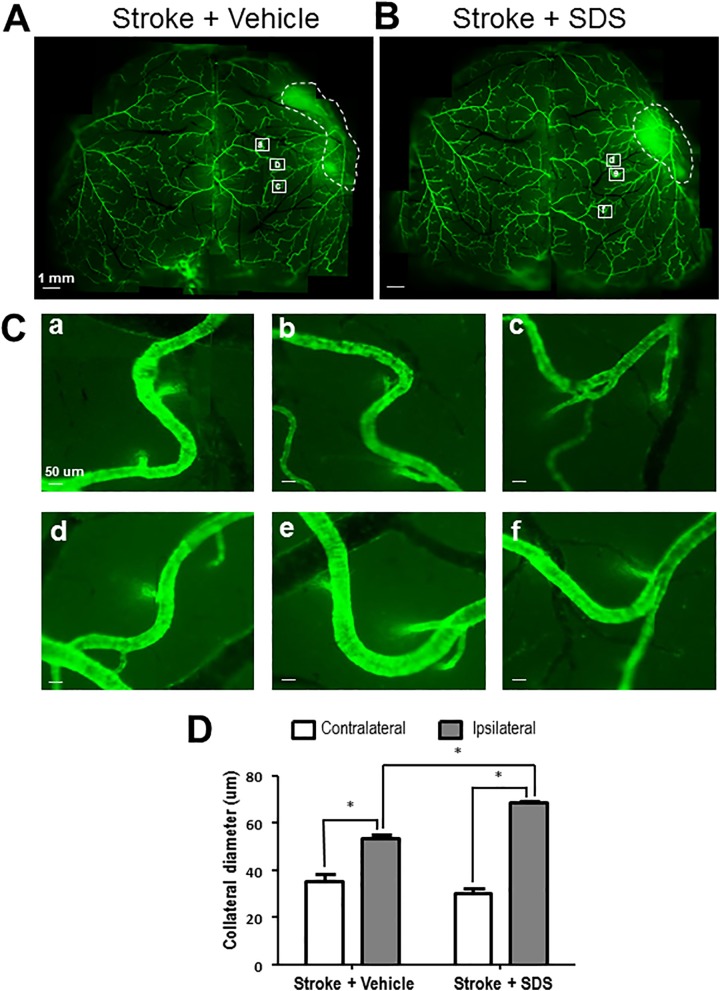

Sodium-Danshensu-Enhanced Collaterogenesis in the Peri-Infarct Cortex

Functional collateral circulation relies on intact capillary and small artery networks. It was shown that therapies promoting angiogenic and arteriogenic factors remarkably improve collaterogenesis in cardiomyocytes47. Angiogenesis and arteriogenesis in the peri-infarct region were determined by newly generated endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, respectively. In immunohistochemical staining 14 days after stroke, collagen-IV-labeled vessel density and the number of newly generated BrdU and collagen IV double-positive cells increased in the SDS-treated mouse brain compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figs. 4A and 4B). Increased new capillary was shown using the BrdU and collagen IV double labeling after stroke, and shown an increase in the SDS-treated brain (Fig. 4B). In the αSMA transgenic mouse, collateral arteries can be visualized by the green fluorescence of αSMA (Fig. 4C). Co-labeling of BrdU and αSMA was used to reveal proliferating arterial smooth muscle cells, and the SDS treatment showed a marked effect of increasing the number of BrdU and αSMA double-positive cells measured at 21 days after stroke (Fig. 4D). In the peri-infarct region, where collaterogenesis is active in the post-ischemic brain, the diameter of ipsilateral collaterals was significantly higher than that in the contralateral cortex. The SDS treatment further increased the diameter of these collaterals in the ipsilateral cortex, suggesting a remodeling of collateral arteries (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Enhanced angiogenesis and collaterogenesis by sodium danshensu.

(A) Representative images of vascular density in the peri-infarction cortex of vehicle control mice and SDS-treated mice at 14 days after stroke. (B) Endothelial cell proliferation was revealed by co-staining with collagen IV and BrdU. At 14 days after stroke, more BrdU-positive endothelial cells were seen in SDS-treated mice compared with vehicle control mice. Vessel ratio and BrdU-positive endothelial cells in the peri-ischemic cortex at 14 days after MCAO for each group were quantified. Administration of SDS significantly increased vascular density and endothelial cell proliferation 14 days after focal cortical infarction. n = 6 animals in each group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. (C) Enhanced arteriogenesis by SDS. Colocalization of the smooth muscle cell marker αSMA (green) and the proliferation marker BrdU (red) in the peri-infarct region was examined 21 days after stroke. In SDS-treated mice, there were more both αSMA- and BrdU-positive cells compared with vehicle control mice. (D) Cell count was performed in six randomly chosen fields in the peri-infarct region; six regions per section. The total number of cells in six sections was summarized for each animal. Cell counts showed increased number of αSMA-/BrdU-positive cells in SDS-treated mice compared with vehicle control mice. n = 5 animals in each group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. SDS: sodium danshensu; BrdU: 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion; SEM: standard error of the mean; αSMA: alpha smooth muscle actin.

Fig. 5.

Enhanced collateral dilation by sodium danshensu.

The diameter of collaterals was measured by the imaging software ImageJ 21 days after stroke. (A, B) The arteries’ image of vehicle control mice (A) and SDS-treated mice (B). (C) The enlarged representative collaterals in vehicle control mice (a, b, c) and SDS-treated mice (d, e, f). (D) Mean diameter of collaterals in each group. Increased diameter of ipsilateral collaterals was shown 21 days after stroke and the dilation of ipsilateral collaterals was enhanced by SDS treatment. Six collaterals and six areas of each collateral were measured. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. SDS: sodium danshensu; SEM: standard error of the mean.

Restoration of Local Cerebral Blood Flow and Functional Activity by Sodium Danshensu Treatment

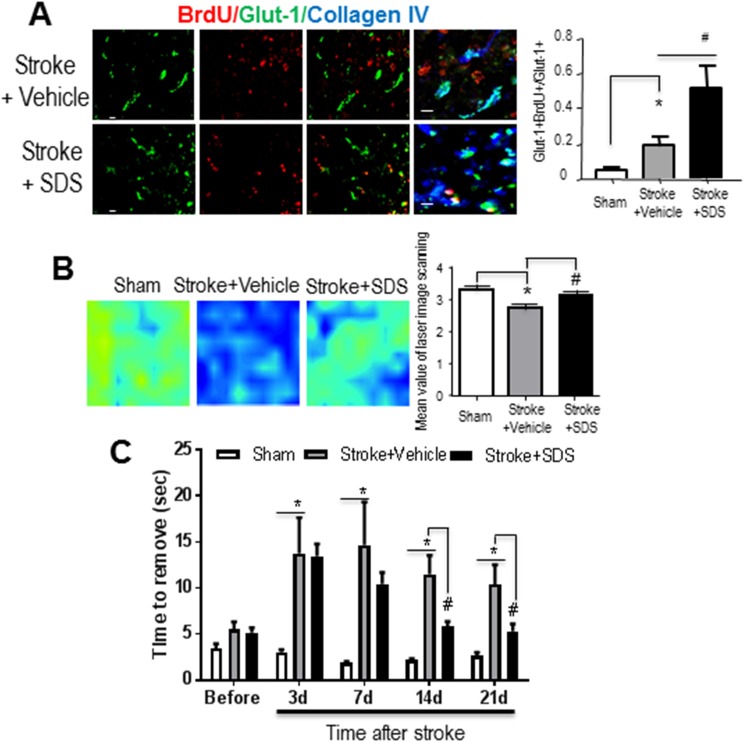

In the peri-infarct region 21 days after stroke, we identified BrdU-labeled GLUT-1-positive endothelial cells co-localized with the collagen IV staining (Fig. 6A). To understand whether the newly formed vessels could benefit reperfusion, local blood flow was measured using laser Doppler imaging. Enhanced blood flow was seen in SDS-treated ischemic cortex compared with vehicle treatment; the flow level recovered to a near-normal level (Fig. 6B). To assess sensorimotor function, the adhesive removal test was employed. Rodents show prolonged times in perceiving and removing of the attached sticky dot from their affected forepaws after stroke, indicating the damaged sensorimotor cortex and the neuronal pathway. The SDS treatment significantly reduced the delay in removing the adhesive tape in the test (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Restoration of local cerebral blood flow in the ischemic cortex.

(A) Representative images of double labeling for GLUT-1 and BrdU in the peri-infarction cortex of vehicle control mice and SDS-treated mice. (B) Local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) was measured by PeriScans laser image scanner. Laser scanning images of LCBF in the stroke region 21 days after ischemia in the sham-operated group, stroke + vehicle group and stroke + SDS treatment group were presented. Marked LCBF recovery can be seen in the mice receiving SDS after stroke. SDS-treated mice showed significantly higher local blood flow compared with vehicle control mice. n = 6 animals in each group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control group. (C) Adhesive removal performance. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Time to removal of the adhesive tape on the contro-lesional paw in each group of animals before or after ischemic stroke are presented. After stroke, time to removal of the adhesive tape was markedly increased, and after SDS treatment, it was reduced. * P < 0.05 compared with the sham group; # P < 0.05 compared with the vehicle control group. n = 6 in the sham and vehicle control group, and n = 10 in the danshensu treatment group. GLUT-1: glucose transporter 1; BrdU: 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; SDS: sodium danshensu; SEM: standard error of the mean.

Discussion

In the present investigation, we examined regenerative effects of sodium danshensu in a mouse focal ischemic stroke model. SDS increased NPC proliferation and several key trophic and regenerative factors from these cells. A chronic SDS treatment after an ischemic insult promoted endogenous neurogenesis and collaterogenesis, demonstrated by increased newborn neurons, endothelial cell/vessel proliferation, and generation of collateral arteries. The SDS treatment helped to restore local blood flow, which is consistent with increased functional angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, and collateral circulation. The improved regenerative activities ultimately lead to long-term sensorimotor functional recovery from the focal ischemic stroke. Thus, this study demonstrates a strong regenerative property of the active element from the herb plant Danshen and its central effects for a regenerative treatment after ischemic stroke.

Considering that neurogenesis occurs in the adult brain48, we analyzed newly formed NPCs in the post-stroke brain. Cells in normal animals regularly migrate to the olfactory bulb, differentiate into interneurons and join the neural network49,50. After brain injuries such as cerebral ischemic stroke, the SVZ neuronal precursors proliferate and migrate into the ischemic lesion and differentiate into neurons and forming synapses with neighboring striatal cells51–53. Unfortunately, the number of new cells and surviving neurons from the SVZ are far from sufficient for tissue repair. In the examination of this regenerative mechanism, DCX is regarded as a marker for migrating neuroblasts and used to follow stroke-induced neurogenesis4,54. We showed in our previous study that stroke induces increased DCX-positive cells starting from 1 day after stroke46. In DCX knockout mice, severe morphological defects in the rostral migratory stream and delayed neuronal migration were found55. These studies indicate that DCX-positive cells and endogenous neurogenesis are important regenerative mechanisms45,46. The present investigation examined long-term effects of SDS on the chronic phase of neurogenesis 14 to 28 days after stroke. SDS increased the number of cells double-labeled with DCX, BrdU, and/or NeuN in the peri-ischemic cortex. SDS may achieve this effect by reducing cell death, increasing proliferation of NPCs, enhancing migration of the DCX-positive cells, and promoting trophic supports in peri-infarct regions. Danshen is a clinically used herb medicine with few side effects. The new sodium compound danshensu has the ability to cross the BBB31,56–58. With the recent observation that collateral circulation is critical for the outcomes of stroke patients, the effect of SDS on promoting collaterogenesis has promising potential to be used clinically for improving post-stroke reperfusion and functional recovery of ischemic stroke patients.

Danshensu and Danshen derivatives decreased inflammation56 and might protect against the secondary injury responses following ischemia. Other S. miltiorrhiza active components were shown to reduce inflammation caused by ischemic stroke59. Salvianolic acid B reduced chronic oxidative stress in animals with a high-fat diet, decreased nuclear factor-κB, cyclooxygenase-2, and inducible NO synthesis, and increased nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2. Salvianolic acid B was also inhibited glial fibrillary acidic protein, Iba-1 , interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α in ischemic brains60. We believe that further tests using S. miltiorrhiza extract can clarify its relationship to brain inflammation. Whether danshensu alone regulates inflammation needs to be investigated as well in future studies.

The key mechanism proposed in this study is the increased trophic support in the peri-infarct regions. The promoted migration of neuronal cells to the peri-infarct regions may be due to increased chemoattractant and neurotrophic molecules. Among them, the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 play an important role after cerebral ischemia in directing the migration of neuroblasts to ischemic lesion61,62. After stroke, the SDF-1 expression is markedly up-regulated in and around the lesion site63,64. Blocking the SDF-1/CXCR4 chemoattractant axis by neutralizing antibody against CXCR4 significantly attenuated stroke-induced NPC migration65. In the current study, SDS administration enhances SDF-1 expression and promotes homing of NPCs after cerebral ischemia. SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling has also been reported to promote VEGF-mediated angiogenesis through the protein kinase pathway66. Treatment with SDF-1 after stroke resulted in more neurovascular structures in the ischemic peri-infarct region. VEGF is essential for endothelial cell proliferation and formation of new microvessels that are linked to neurogenesis16,67. BDNF is another link between neurogenesis and angiogenesis, which is secreted by endothelial cells after angiogenic stimulation and induces neurogenesis17. SDS treatment increases both VEGF and BDNF expression, which contributes to the enhancement of neurogenesis and angiogenesis in the post-stroke brain.

VEGF may also contribute to native collateral formation and arteriogenesis. Blocking VEGF by antagonists attenuated ischemic collateral remodeling and growth68. Attenuated perfusion and impaired collateral remodeling after stroke were also found in VEGF low-expressing mice69. This is consistent with our finding that SDS increased VEGF expression, as well as arteriogenesis/collaterogenesis. We also found an eNOS increase by SDS in the ischemic brain. Remarkably, eNOS plays important roles in the post-ischemic revascularization process. It can participate in endothelial cell proliferation and migration, smooth muscle cell differentiation, angiogenic processes, and arterial–venous differentiation70 , 71. Significant decreases in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and arteriogenesis after stroke were reported in the eNOS knockout mice, suggesting its important role in arteriogenesis and long-term repair from ischemia19.

In summary, sodium danshensu shows strong effects on enhancing endogenous neurogenesis and collaterogenesis by upregulating different factors to promote NPCs to proliferate and differentiate to mature neurons, promoting endothelial cell proliferation and formation of new microvessels, as well as collateral remodeling and growth. All these events benefit tissue repair and functional recovery after ischemia. Our study provides new insights into the therapeutic mechanism of SDS against ischemia-induced injury. Further studies may identify the specific molecules and signaling pathways that are involved in the regulation of neurovascular plasticity and collateral circulation by SDS treatment.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: We confirm that Ethical Committee approval was sought where necessary and is acknowledged within the text of the submitted manuscript.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All animals were housed in the Animal Facility at Emory University. The treatment and pre-, post-surgery care followed the approved animal protocol 2003524 and matched to the NIH standard.

Statement of Informed Consent: We confirm that guidelines on patient consent have been met and any details of informed consent obtained are indicated within the text of the submitted manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: The work was supported by NIH grants NS085568 (LW/SPY), NS091585 (LW), and by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China 81371355, 81771235 and 81671191 (YBZ), and 81500989 (ZZW). We also thank Dr. Shanshan Zou (Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University) for her technical help.

References

- 1. Beck H, Plate KH. Angiogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(5):481–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jin K, Minami M, Lan JQ, Mao XO, Batteur S, Simon RP, Greenberg DA. Neurogenesis in dentate subgranular zone and rostral subventricular zone after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4710–4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parent JM, Vexler ZS, Gong C, Derugin N, Ferriero DM. Rat forebrain neurogenesis and striatal neuron replacement after focal stroke. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(6):802–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang R, Zhang Z, Wang L, Wang Y, Gousev A, Zhang L, Ho KL, Morshead C, Chopp M. Activated neural stem cells contribute to stroke-induced neurogenesis and neuroblast migration toward the infarct boundary in adult rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(4):441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li WL, Yu SP, Ogle ME, Ding XS, Wei L. Enhanced neurogenesis and cell migration following focal ischemia and peripheral stimulation in mice. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68(13):1474–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raber J, Fan Y, Matsumori Y, Liu Z, Weinstein PR, Fike JR, Liu J. Irradiation attenuates neurogenesis and exacerbates ischemia-induced deficits. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin K, Wang X, Xie L, Mao XO, Greenberg DA. Transgenic ablation of doublecortin-expressing cells suppresses adult neurogenesis and worsens stroke outcome in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):7993–7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ding DC, Lin CH, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Neural stem cells and stroke. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(4):619–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1994;25(9):1794–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wei L, Erinjeri JP, Rovainen CM, Woolsey TA. Collateral growth and angiogenesis around cortical stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(9):2179–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leventhal C, Rafii S, Rafii D, Shahar A, Goldman SA. Endothelial trophic support of neuronal production and recruitment from the adult mammalian subependyma. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13(6):450–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palmer TD, Willhoite AR, Gage FH. Vascular niche for adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425(4):479–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shen Q, Goderie SK, Jin L, Karanth N, Sun Y, Abramova N, Vincent P, Pumiglia K, Temple S. Endothelial cells stimulate self-renewal and expand neurogenesis of neural stem cells. Science. 2004;304(5675):1338–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, McTaggart RA, Torbey MT, Kim-Tenser M, Leslie-Mazwi T, Sarraj A, Kasner SE, Ansari SA, Yeatts SD, Hamilton S, Mlynash M, Heit JJ, Zaharchuk G, Kim S, Carrozzella J, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM. et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging N Engl J Med.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang R, Wang L, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, Chopp M. Nitric oxide enhances angiogenesis via the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor and cgmp after stroke in the rat. Circ Res. 2003;92(3):308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jin K, Zhu Y, Sun Y, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(18):11946–11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenberg DA, Jin K. From angiogenesis to neuropathology. Nature. 2005;438(7070):954–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang L, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang R, Chopp M. Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1732–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cui X, Chopp M, Zacharek A, Zhang C, Roberts C, Chen J. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase in arteriogenesis after stroke in mice. Neurosci. 2009;159(2):744–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MS. Danshen: An overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(12):1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu B, Liu M, Zhang S. Dan shen agents for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2): CD004295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ai F, Chen M, Li W, Yang Y, Xu G, Gui F, Liu Z, Bai X, Chen Z. Danshen improves damaged cardiac angiogenesis and cardiac function induced by myocardial infarction by modulating HIF1alpha/VEGFa signaling pathway. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(10):18311–18318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yin Q, Lu H, Bai Y, Tian A, Yang Q, Wu J, Yang C, Fan TP, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Zheng X, Li Z. A metabolite of danshen formulae attenuates cardiac fibrosis induced by isoprenaline, via a NOX2/ROS/p38 pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(23):5573–5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang CC, Chang YC, Hu WL, Hung YC. Oxidative stress and salvia miltiorrhiza in aging-associated cardiovascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4797102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu H, Zou L, Tian J, Du G, Gao Y. SMND-309, a novel derivative of salvianolic acid b, protects rat brains ischemia and reperfusion injury by targeting the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;714(1-3):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hur KY, Seo HJ, Kang ES, Kim SH, Song S, Kim EH, Lim S, Choi C, Heo JH, Hwang KC, Ahn CW, Cha BS, Jung M, Lee HC. Therapeutic effect of magnesium lithospermate b on neointimal formation after balloon-induced vascular injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;586(1-3):226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lou Z, Ren KD, Tan B, Peng JJ, Ren X, Yang ZB, Liu B, Yang J, Ma QL, Luo XJ, Peng J. Salviaolate protects rat brain from ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibition of NADPH oxidase. Planta Med. 2015;81(15):1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lv H, Wang L, Shen J, Hao S, Ming A, Wang X, Su F, Zhang Z. Salvianolic acid b attenuates apoptosis and inflammation via Sirt1 activation in experimental stroke rats. Brain Res Bull. 2015;115:30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin LL, Wang W, Cheng MH, Liu AJ. Protection of different components of danshen in cerebral infarction in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(6):511–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jiang YF, Liu ZQ, Cui W, Zhang WT, Gong JP, Wang XM, Zhang Y, Yang MJ. Antioxidant effect of salvianolic acid b on hippocampal ca1 neurons in mice with cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21(7):516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang ZC, Xu M, Sun SF, Guo H, Qiao X, Han J, Wang BR, Guo DA. Determination of danshensu in rat plasma and tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci. 2008;46(2):184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou L, Chow MS, Zuo Z. Effect of sodium caprate on the oral absorptions of danshensu and salvianolic acid b. Int J Pharm. 2009;379(1):109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang J, Ma Z, Wang W, Hong Z, Song J. [Comparative pharmacokinetic study of sodium danshensu and salvia miltiorrhiza injection in rat]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2009;34(22):2943–2945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei L, Cui L, Snider BJ, Rivkin M, Yu SS, Lee CS, Adams LD, Gottlieb DI, Johnson EM, Jr, Yu SP, Choi DW. Transplantation of embryonic stem cells overexpressing BCL-2 promotes functional recovery after transient cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19(1-2):183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wei L, Craven K, Erinjeri J, Liang GE, Bereczki D, Rovainen CM, Woolsey TA, Fenstermacher JD. Local cerebral blood flow during the first hour following acute ligation of multiple arterioles in rat whisker barrel cortex. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5(3):142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wei ZZ, Lee JH, Zhang Y, Zhu YB, Deveau TC, Gu X, Winter MM, Li J, Wei L, Yu SP. Intracranial transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells alleviates neuropsychiatric defects after traumatic brain injury in juvenile rats. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(5):797–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang Y, Liu B, Xu J, Wang J, Wu J, Shi C, Xu Y, Dong J, Wang C, Lai W, Zhu J, Xiong L, Zhu D, Li X, Yang W, Yamauchi T, Sugawara A, Li Z, Sun F, Li X, Li C, He A, et al. Derivation of pluripotent stem cells with in vivo embryonic and extraembryonic potency. Cell. 2017;169(2):243–257, e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chau M, Deveau TC, Song M, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Yu SP, Wei L. Transplantation of iPS cell-derived neural progenitors overexpressing SDF-1alpha increases regeneration and functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Oncotarget. 2017;8(57):97537–97553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bouet V, Boulouard M, Toutain J, Divoux D, Bernaudin M, Schumann-Bard P, Freret T. The adhesive removal test: A sensitive method to assess sensorimotor deficits in mice. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(10):1560–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Freret T, Bouet V, Leconte C, Roussel S, Chazalviel L, Divoux D, Schumann-Bard P, Boulouard M. Behavioral deficits after distal focal cerebral ischemia in mice: Usefulness of adhesive removal test. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123(1):224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wei ZZ, Zhang JY, Taylor TM, Gu X, Zhao Y, Wei L. Neuroprotective and regenerative roles of intranasal Wnt-3a administration after focal ischemic stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017:271678X17702669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci. 2006;26(50):13007–13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee JH, Wei L, Gu X, Won S, Wei ZZ, Dix TA, Yu SP. Improved therapeutic benefits by combining physical cooling with pharmacological hypothermia after severe stroke in rats. Stroke. 2016;47(7):1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li Y, Lu Z, Keogh CL, Yu SP, Wei L. Erythropoietin-induced neurovascular protection, angiogenesis, and cerebral blood flow restoration after focal ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(5):1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q. Neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and mri indices of functional recovery from stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(suppl 2):827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu SP, Lee SD, Lee HT, Liu DD, Wang HJ, Liu RS, Lin SZ, Su CY, Li H, Shyu WC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor activating HIF-1alpha acts synergistically with erythropoietin to promote tissue plasticity. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu H, Xu X, Zhang M, Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Li C, Lin H, Yao G, Sun H, Qi L, Tang M, Dai H, Zhang Y, Su R, Bi Y, Zhang Y, Cao Y. Combinatorial protein therapy of angiogenic and arteriogenic factors remarkably improves collaterogenesis and cardiac function in pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(29):12140–12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiang MQ, Zhao YY, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Wei L, Yu SP. Long-term survival and regeneration of neuronal and vasculature cells inside the core region after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(4):480–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Ischemic stroke and neurogenesis in the subventricular zone. Neuropharmacol. 2008;55(3):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ohab JJ, Carmichael ST. Poststroke neurogenesis: Emerging principles of migration and localization of immature neurons. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(4):369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Song M, Yu SP, Mohamad O, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Jiang MQ, Wei L. Optogenetic stimulation of glutamatergic neuronal activity in the striatum enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of normal and stroke mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;98:9–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yamashita T, Ninomiya M, Hernandez Acosta P, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Sunabori T, Sakaguchi M, Adachi K, Kojima T, Hirota Y, Kawase T, Araki N, Abe K, Okano H, Sawamoto K. Subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts migrate and differentiate into mature neurons in the post-stroke adult striatum. J Neurosci. 2006;26(24):6627–6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med. 2002;8(9):963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Schaubeck S, Aigner R, Vroemen M, Weidner N, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, Kuhn HG, Aigner L. Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Koizumi H, Higginbotham H, Poon T, Tanaka T, Brinkman BC, Gleeson JG. Doublecortin maintains bipolar shape and nuclear translocation during migration in the adult forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(6):779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang T, Fu F, Han B, Zhang L, Zhang X. Danshensu ameliorates the cognitive decline in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by attenuating advanced glycation end product-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;245(1-2):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Seetapun S, Yaoling J, Wang Y, Zhu YZ. Neuroprotective effect of danshensu derivatives as anti-ischaemia agents on sh-sy5y cells and rat brain. Biosci Rep. 2013;33(4) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kwon G, Kim HJ, Park SJ, Lee HE, Woo H, Ahn YJ, Gao Q, Cheong JH, Jang DS, Ryu JH. Anxiolytic-like effect of danshensu [(3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-lactic acid)] in mice. Life Sci. 2014;101(1-2):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lyu M, Yan CL, Liu HX, Wang TY, Shi XH, Liu JP, Orgah J, Fan GW, Han JH, Wang XY, Zhu Y. Network pharmacology exploration reveals endothelial inflammation as a common mechanism for stroke and coronary artery disease treatment of danhong injection. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fan Y, Luo Q, Wei J, Lin R, Lin L, Li Y, Chen Z, Lin W, Chen Q. Mechanism of salvianolic acid b neuroprotection against ischemia/reperfusion induced cerebral injury. Brain Res. 2018;1679:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Imitola J, Raddassi K, Park KI, Mueller FJ, Nieto M, Teng YD, Frenkel D, Li J, Sidman RL, Walsh CA, Snyder EY, Khoury SJ. Directed migration of neural stem cells to sites of cns injury by the stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha/CXC chemokine receptor 4 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(52):18117–18122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Yen PS, Su CY, Chen DC, Wang HJ, Li H. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha promotes neuroprotection, angiogenesis, and mobilization/homing of bone marrow-derived cells in stroke rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(2):834–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hill WD, Hess DC, Martin-Studdard A, Carothers JJ, Zheng J, Hale D, Maeda M, Fagan SC, Carroll JE, Conway SJ. SDF-1 (CXCL12) is upregulated in the ischemic penumbra following stroke: Association with bone marrow cell homing to injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(1):84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miller JT, Bartley JH, Wimborne HJ, Walker AL, Hess DC, Hill WD, Carroll JE. The neuroblast and angioblast chemotaxic factor sdf-1 (cxcl12) expression is briefly up regulated by reactive astrocytes in brain following neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robin AM, Zhang ZG, Wang L, Zhang RL, Katakowski M, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang C, Chopp M. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha mediates neural progenitor cell motility after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(1):125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liang Z, Brooks J, Willard M, Liang K, Yoon Y, Kang S, Shim H. CXCR4/CXCL12 axis promotes VEGF-mediated tumor angiogenesis through Akt signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359(3):716–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Breier G, Albrecht U, Sterrer S, Risau W. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor during embryonic angiogenesis and endothelial cell differentiation. Development. 1992;114(2):521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Toyota E, Warltier DC, Brock T, Ritman E, Kolz C, O’Malley P, Rocic P, Focardi M, Chilian WM. Vascular endothelial growth factor is required for coronary collateral growth in the rat. Circulation. 2005;112(14):2108–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Clayton JA, Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Vascular endothelial growth factor-a specifies formation of native collaterals and regulates collateral growth in ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103(9):1027–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Zhang QQ, Tan MS, Cao L, Wang HF, Lu J, Gao Q, Zhang YD, Tan L. Angiotensin-(1-7) induces cerebral ischaemic tolerance by promoting brain angiogenesis in a Mas/eNOS-dependent pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(18):4222–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen J, Cui X, Zacharek A, Roberts C, Chopp M. Enos mediates to90317 treatment-induced angiogenesis and functional outcome after stroke in mice. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2532–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim H, Wei Y, Lee JY, Wu Y, Zheng Y, Moskowitz MA, Chen JW. Myeloperoxidase inhibition increases neurogenesis after ischemic stroke. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;359(2):262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]