Abstract

Background

Root-knot nematodes transform vascular host cells into permanent feeding structures to withdraw nutrients from the host plant. Ecotypes of Arabidopsis thaliana can display large quantitative variation in susceptibility to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita, which is thought to be independent of dominant major resistance genes. However, in an earlier genome-wide association study of the interaction between Arabidopsis and M. incognita we identified a quantitative trait locus harboring homologs of dominant resistance genes but with minor effect on susceptibility to the M. incognita population tested.

Results

Here, we report on the characterization of two of these genes encoding the TIR-NB-LRR immune receptor DSC1 (DOMINANT SUPPRESSOR OF Camta 3 NUMBER 1) and the TIR-NB-LRR-WRKY-MAPx protein WRKY19 in nematode-infected Arabidopsis roots. Nematode infection studies and whole transcriptome analyses using the Arabidopsis mutants showed that DSC1 and WRKY19 co-regulate susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita.

Conclusion

Given the head-to-head orientation of DSC1 and WRKY19 in the Arabidopsis genome our data suggests that both genes may function as a TIR-NB-LRR immune receptor pair. Unlike other TIR-NB-LRR pairs involved in dominant disease resistance in plants, DSC1 and WRKY19 most likely regulate basal levels of immunity to root-knot nematodes.

Keywords: Meloidogyne incognita, Arabidopsis, DSC1, WRKY19, Root-knot nematodes, TIR-NB-LRR receptor pair

Background

The root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita is currently ranked as one of the most invasive plant disease-causing agents, having major impact on global agricultural productivity [1]. Infective second stage juveniles (J2) of M. incognita penetrate their host at the root elongation zone. Thereafter, they migrate through the cortex to the root tip and enter the vascular cylinder via the columella and quiescence center. Inside the differentiating vascular cylinder, the J2 carefully puncture the cell walls of several host cells with their stylet to initiate the formation of a permanent feeding site [2–5]. This permanent feeding site includes several giant cells, which are formed by major structural and metabolic changes in host cells, most likely in response to stylet secretions of M. incognita [2, 6]. Juveniles of M. incognita take up their nutrients from these giant cells during the course of several weeks while undergoing three molts to enter the adult stage. Adult females produce eggs, which are held together in a gelatinous matrix at the surface of the roots [2–4].

Plants have developed several lines of defense to protect themselves against attacks by parasitic nematodes [3]. The first line of defense is thought to be structural, where plants make use of rigid cell walls to prevent host invasion (i.e., by migratory ectoparasites). Next, plant cells carry surface-localized receptors to detect molecular patterns in the apoplast that are uniquely associated with host invasion by endoparasitic nematodes [4, 7, 8]. For example, root-knot nematodes release small glycolipids commonly referred to as ascarosides that are recognized as invasion-associated molecular patterns [9]. The exposure of Arabidopsis seedlings to these ascarosides activates basal plant defenses to a broad range of pathogens. Furthermore, Arabidopsis mutant analyses (including BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1)-associated receptor kinase 1 (BAK1)) have shown that receptor-mediated basal immunity plays a significant role in the susceptibility of plants to root-knot nematodes [10]. Interestingly, root-knot nematodes have effectors capable of selectively suppressing responses activated by surface-localized immune receptors, which indicates adaptation to this line of defense [11–14].

At a later stage in the infection process, nematode resistant plants can counteract the establishment of a permanent feeding site with effector-triggered immunity, which is predominantly based on sensing nematode effectors by intracellular immune receptors [3, 15]. Effector-triggered immunity to root-knot nematodes often involves a hypersensitive-response in- and around giant cells, which interrupts the flows of assimilates towards the feeding nematodes. As a consequence of insufficient supply of nutrients, this type of major resistance induces a developmental arrest in juveniles.

The largest group of intracellular plant immune receptors is formed by the nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR) superfamily of immune receptors. These NB-LRRs consist of a central nucleotide-binding domain attached to a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain and a variable N-terminal domain that can either be a coiled-coil (CC) or a Toll-interleukin-1 receptor (TIR)-like domain [4, 16–18]. Three major resistance (R) genes encoding intracellular NB-LRR immune receptors conferring resistance to M. incognita are cloned, one of which is encoding a CC-NB-LRR receptor (Mi-1.2 from Solanum peruvianum) and two encode TIR-NB-LRR proteins (Ma from Prunus cerasifera and PsoRPM2 from Prunus sogdiana) [19–21]. Most of the commercially grown tomato varieties (Solanum lycopersicum) carry introgressions of the Mi-1.2 gene, conferring high levels of resistance to several tropical root-knot nematode species (e.g., M. incognita, M. javanica and M. arenaria) [22, 23]. Resistance based on Mi-1.2 is currently losing efficacy in the field due to its temperature sensitivity and because of natural selection of virulent nematode populations [19, 24, 25]. The breakdown of Mi-1.2 resistance and the small number of major resistance genes currently available for root-knot nematodes has prompted a search for alternative strategies to develop durable nematode resistant crops.

Previously, we used genome-wide association mapping to identify less conducive allelic variants of genes that critically determine susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita (i.e. S-genes [26, 27];). In total, we identified 19 QTL (quantitative trait loci) in the genome of Arabidopsis contributing to quantitative variation in reproductive success of M. incognita. We selected Arabidopsis as a model host for our studies because it is thought to lack major resistance to M. incognita. However, one of the QTL with minor effect on susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita harbors homologs of the TIR-NB-LRR class of resistance genes. Here, we report on the functional characterization of these TIR-NB-LRR genes that were previously annotated as DSC1 and WRKY19. DSC1 encodes a typical TIR-NB-LRR immune receptor [28], whereas WRKY19 also includes a WRKY domain and MAPx domain at the C-terminus [29]. Our data from mutant analyses and whole transcriptome analyses suggest that the coordinated activity of DSC1 and WRKY19 as a receptor pair may be involved in regulating basal defense of Arabidopsis to M. incognita.

Results

Multiple TIR-NB-LRR protein encoding genes in a QTL for susceptibility

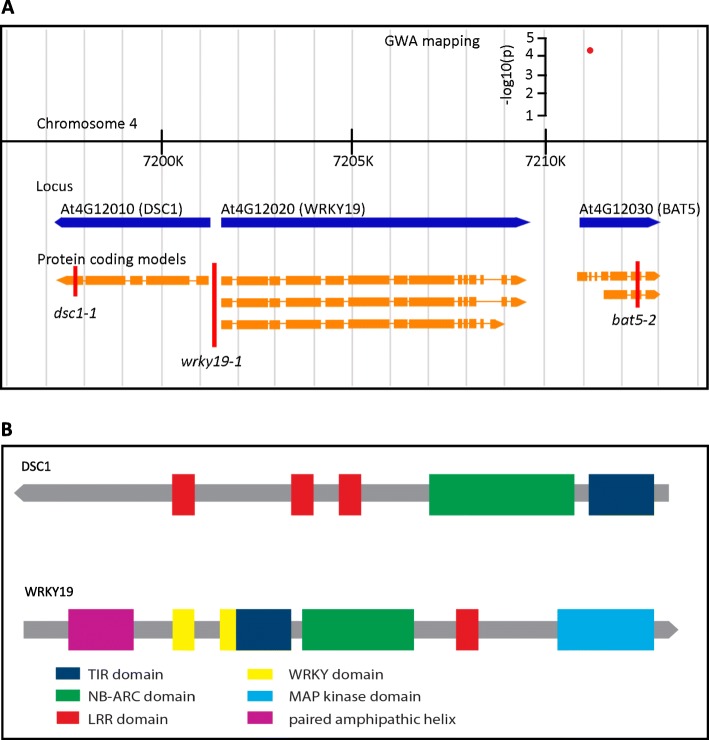

In our previously published GWA (genome-wide association) study of the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita we identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) marker on chromosome 4, which was closely linked to two genes with similarity to TIR-NB-LRR-type immune receptors [26]. This SNP marker (138442) was located inside an exon of BILE ACID TRANSPORTER 5 (BAT5; At4G12030) and leads to a non-synonymous mutation (Val to Ala) close to the amino terminus of the protein (Fig. 1a). However, located directly upstream of BAT5 are DOMINANT SUPPRESSOR of Camta3 NUMBER 1 (DSC1; At4G12010) and MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE-WRKY19 (WRKY19; At4G12020), which both possess TIR, NB-ARC and LRR domains (Fig. 1a and b). BAT5, DSC1 and WRKY19 are all within 10 kb of SNP marker 138,442 and could therefore be causal for the effect on susceptibility to M. incognita associated with this marker.

Fig. 1.

Genomic orientation of BAT5, WRKY19 and DSC1, including the protein domains present in WKRY19 and DSC1. a, Representation of the genomic region around significantly associated SNP marker 138,422. The red dot represents the SNP with the corresponding –log10(p) score from the genome wide association mapping. The blue arrows represent the predicted genes. Transcripts derived from these genes are indicated in orange, with rectangles marking the protein coding exons. The red vertical line indicates a T-DNA insert with the corresponding name. b, Schematic representation of protein domains present in DSC1 and WRKY19. Colored blocks represent the different domains present in the protein sequence

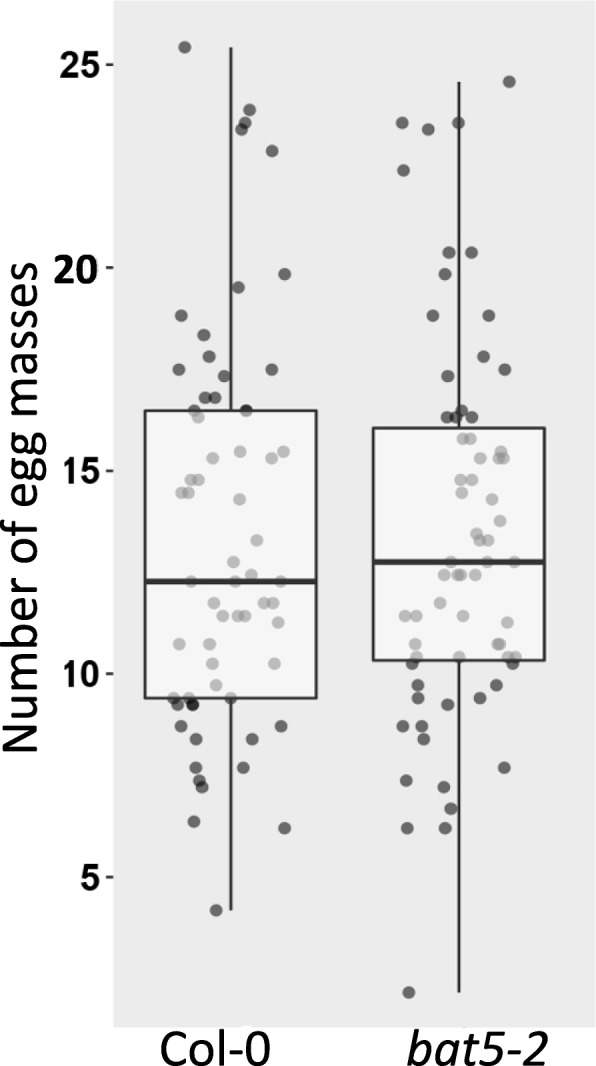

BAT5 is not causally linked to susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita

Since SNP marker 138,442 is located inside the coding sequence of BAT5, we first tested if this gene is required for susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita. Thereto, we inoculated the roots of in vitro grown plants of the homozygous Arabidopsis T-DNA insert line bat5–2 with infective J2 of M. incognita. The bat5–2 mutant harbors a T-DNA insertion in the second last exon, resulting only in a slight reduction of mRNA levels of BAT5 (Fig. 1a; Additional file 1). However, as the insert in bat5–2 disrupts the open reading frame in BAT5, mRNAs are probably not translated into a functional protein. Nonetheless, six weeks after inoculation the number of egg masses produced by M. incognita per plant were not significantly different between bat5–2 and wildtype Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 2). We also investigated the root architecture of the bat5–2 mutant line at the time of inoculation (dpi = 0) as this may affect the susceptibility score of Arabidopsis for M. incognita, but we observed no significant difference in the number of root tips per plant for the bat5–2 mutant compared to the wildtype Arabidopsis control plant Col-0 (Additional file 2). Altogether, our results provide no evidence for a significant role for BAT5 in susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita.

Fig. 2.

Susceptibility of the homozygous Arabidopsis T-DNA line bat5–2 to M. incognita. Number of egg masses per plant at 6 weeks post inoculation on bat5–2 and wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0 plants. Bars reflect the averages and standard error of the mean of three independent experiments (n > 18 per experiment). Data were statistically tested for significance with ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test (p < 0.05)

DSC1 and WRKY19 may both regulate susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita

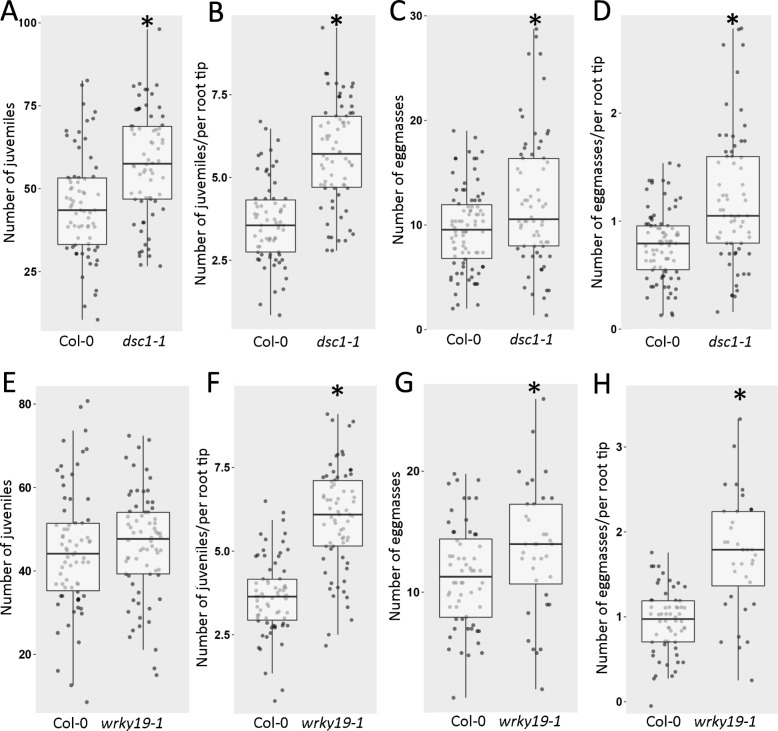

To study whether DSC1 and WRKY19 were involved in susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita, we also tested the homozygous Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 in nematode infection assays. The T-DNA insert in dsc1–1 is located in the last exon of DSC1, which causes a complete knock-out of gene expression (Additional file 1). In contrast, the T-DNA insert in wrky19–1 is located in the putative promotor regions of both genes, which leads to strong upregulation of WRKY19 expression and a small but significant down-regulation of DSC1 (Additional file 1). Susceptibility of the mutant and wildtype plants was tested at 7 days post inoculation in this study, which corresponds to an early stage in root-knot nematode parasitism that includes the successful invasion of the roots and the initiation of a proper feeding site for further development and reproduction (two hallmarks for host susceptibility to plant-parasitic nematodes). At seven days after inoculation with M. incognita, we observed a significantly higher number of juveniles inside roots of the dsc1–1 mutant plants compared to the roots of wildtype Arabidopsis control plants (Fig. 3a). The number of juveniles inside the roots of the wrky19–1 overexpressing mutant was also slightly, but not significantly, higher as compared to wildtype Arabidopsis control plants (Fig. 3e). However, it should be noted that we also observed a significant lower number of root tips per plant for both the dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 mutants compared to wildtype Arabidopsis plants at the time of inoculation (dpi = 0; Additional file 3). When we corrected our data for this difference in root architecture, the number of juveniles per root tip was significantly higher in roots of both dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 mutant lines as compared to wildtype Arabidopsis control plants (Fig. 3b and f). Likewise, at six weeks after inoculation the number of egg masses per plant root system and the number of egg masses per root tip was significantly higher in both the dsc1–1 knock-out mutant line and wrky19–1 overexpressing mutant line as compared to the wildtype Arabidopsis control plants (Fig. 3c, d, g, and f).

Fig. 3.

Susceptibility of homozygous Arabidopsis T-DNA lines dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 to M. incognita. a, e number of parasitic juveniles per plant at 7 days post inoculation (dpi = 7) on dsc1–1, wkry19–1 and wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 plants. b, f number of parasitic juveniles per plant at 7 days post inoculation on dsc1–1, wkry19–1 and wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 plants corrected for the number of root tips at the start of the infection (dpi = 0). c, g Number of egg masses per plant at 6 weeks post inoculation on dsc1–1, wrky19–1 and wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 plants. d, h Number of egg masses per plant at 6 weeks post inoculation on dsc1–1, wkry19–1 and wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 plants corrected for the number of root tips at the start of the infection. Boxplot represent data of three independent experiments (n > 12 per experiment). Data were statistically tested for significance with ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD (* p < 0.05)

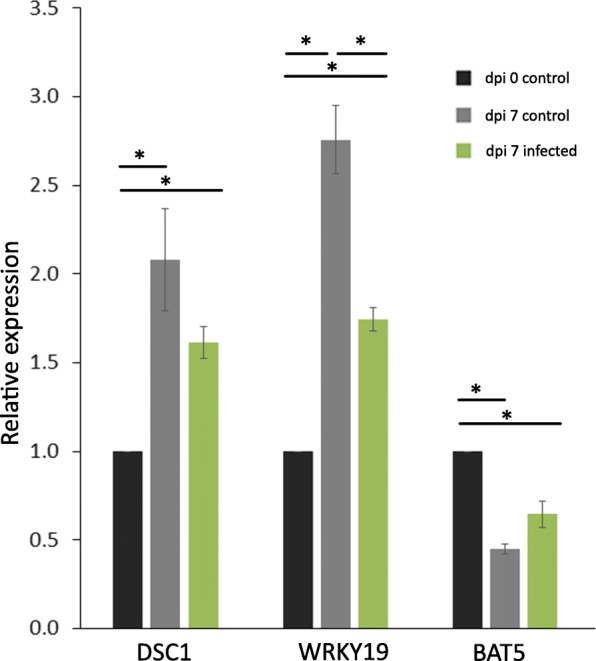

Our observations on the wrky19–1 mutant line suggest that quantitative differences in expression levels of DSC1 and WRKY19 could influence both root development and susceptibility to M. incognita in opposite ways. We therefore investigated if the expression of DSC1 and WRKY19 is indeed regulated during root development and nematode infections in wildtype Arabidopsis plants using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) with gene specific primers (Fig. 4). Interestingly, both DSC1 and WRKY19 were upregulated in non-infected roots of Arabidopsis Col-0 when comparing 14 day old and 21 day old plants. This is consistent with a positive role for both genes in root development as suggested by the root phenotype of the dsc1-1 and wrky19–1 mutant lines. In contrast, we only observed a significant down-regulation of WRKY19 in nematode-infected roots at 7 days post inoculation with M. incognita. This is consistent with a role for WRKY19 as a negative regulator of defense responses to M. incognita, as suggested by the increased number of nematodes on the wrky19–1 mutant line, which is overexpressing WRKY19. Neither DSC1 nor BAT5 were significantly regulated in the roots of wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 plants at seven days post inoculation with M. incognita. The lack of change in DSC1 gene expression seems inconsistent with the observed increase in nematode infection on the dsc1–1 mutant plants. However, this could indicate that no de novo synthesis of DSC1 is required for a role in regulating nematode susceptibility, or that we were not able to detect a local change in gene expression at the infection site due to the use of whole roots as input for the qRT-PCR analysis.

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of DSC1, WRKY19 and BAT5 in roots of Arabidopsis infected with and without M. incognita. Data is shown for whole roots collected at the time of inoculation with M. incognita (0 days control), for whole roots collected at 7 days after mock-inoculation (7 days control) and 7 days after inoculation with M. incognita (7 days infection). Data is represented as comparison against the expression level at 0 days control. Data is based on three independent experiments with three technical replicates per experiment. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Data was analyzed with a student t-test (* = p < 0.05)

DSC1 and WRKY19 regulate gene expression during M. incognita infection

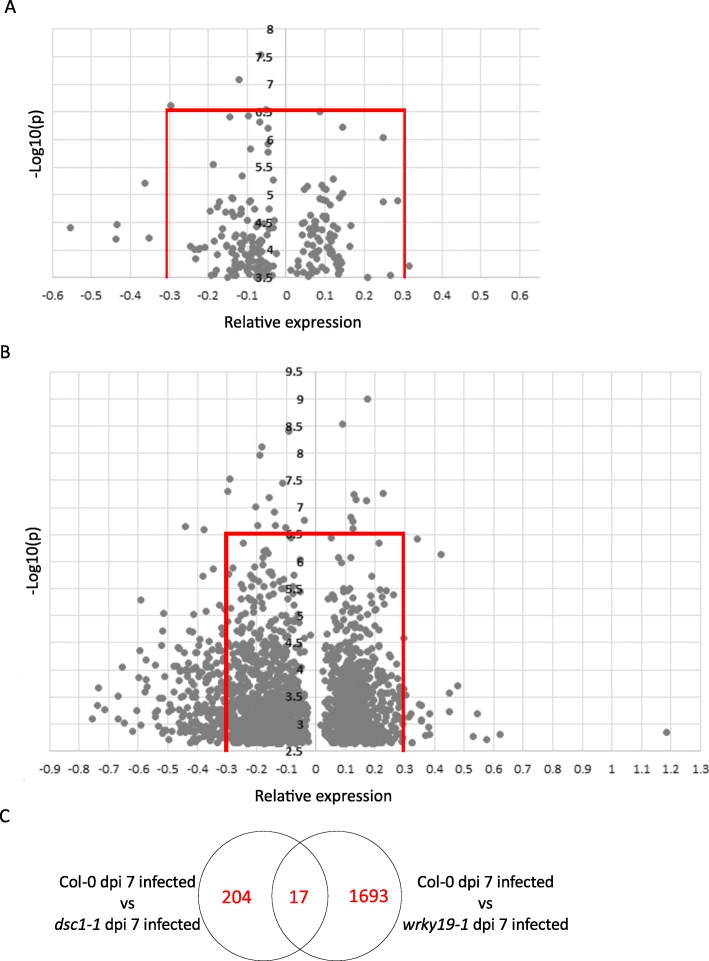

To gain more insight in the possible role of DSC1 in susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita, we analyzed the transcriptome of whole roots of the dsc1–1 mutant line and wildtype Arabidopsis control seven days after inoculation with M. incognita using Arabidopsis gene expression microarrays. As expected, in non-infected roots of the dsc1–1 mutant expression of DSC1 was absent, but – to our surprise – no other genes were differentially expressed in comparison with non-infected roots of wildtype Arabidopsis plants of the same age (at -log10(P) > 3.5). However, we observed the differential expression of 221 genes in a comparison between nematode-infected roots of the dsc1–1 mutant and wildtype Arabidopsis control plants at seven days after inoculation (Fig. 5a). To determine which genes were strongly affected by the mutation in dsc1–1, we focused on genes that were either standing out because of a large change in expression level (i.e., mean normalized log2-change in probe intensities < − 0.3 or > 0.3), because of high statistical support of the changes (−log10(P) > 6.5)), or both (Fig. 5a). Applying these criteria resulted in a list of twelve differentially expressed genes in the absence of DSC1, which included several genes –like DSC1 – with a link to abiotic- and biotic stress responses (Table 1, Fig. 5a). Three genes were selected for testing by qRT-PCR (Additional file 6) to confirm the observed changes in gene expression in the microarray analysis. Similar expression patterns were observed (Fig. 6), supporting the up- or downregulation of the selected genes in M. incognita-infected roots of the dsc1–1 mutant at 7 dpi as observed in the microarray analysis.

Fig. 5.

Differential expression analysis of dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 seven days after M. incognita infection. a, 221 genes were differentially expressed in dsc1–1 compared to Col-0. The dot which represents the expression of DSC1 with a significance of 10.5 and an effect size of − 2.50 is excluded from this figure for clarity. The red lines indicate the threshold for significance of 7 and effect size of 0.3. b, 1710 genes were differentially regulated in wrky19–1 compared to Col-0. The red lines indicate the threshold for significance of 7 and effect size of 0.7. c, Venn diagram indicating the comparison between differently expressed genes in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 7 days after infection with M. incognita

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 at 7 days post inoculation with M. incognita

| Gene ID | Significance | Relative expression | Gene description | WRKY domain in promotor | Associated with |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated in dsc1–1 | |||||

| AT4G12010 | 10.71 | −2.50 | Dominant suppressor of CAMTA3 1 (DSC1) | N | Biotic stress response [28] |

| AT1G28040 | 7.55 | −0.07 | Ring/U-box superfamily protein | – | Putative ubiquitin ligase |

| AT2G38380 | 7.08 | −0.12 | Peroxidase superfamily protein | Y | Abiotic stress response [30] |

| AT4G16745 | 6.62 | −0.29 | Exostosin family protein | N | Pollen germination [31] |

| AT1G70360 | 6.54 | − 0.05 | F-box family protein | N | Putative ubiquitin ligase |

| AT5G57655 | 6.50 | 0.08 | Xylose isomerase family protein | N | Recovery from abiotic stress [32] |

| AT3G52970 | 5.21 | −0.36 | Cytochrome P450, family 76, subfamily G, polypeptide 1 | Y | |

| AT5G06905 | 4.46 | −0.44 | Cytochrome P450, family 93, subfamily D peptide 1 | Y | Putative oxygen-binding activity |

| AT4G29690 | 4.41 | −0.56 | Alkaline-phosphatase-like family protein | Y | Hormone signaling and responses [33] |

| AT1G68040 | 4.22 | −0.35 | S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase superfamily protein | N | Defense [34] |

| AT5G06900 | 4.21 | − 0.44 | Cytochrome P450, family 712, subfamily A polypeptide 2 | Y | Putative oxygen-binding activity |

| AT1G56280 | 3.72 | 0.32 | drought-induced 19 (Di19) | N | Abiotic stress response [35] |

| Regulated in wrky19–1 | |||||

| AT2G38330 | 9.00 | 0.18 | Mate Efflux family protein | Y | Biotic stress response [36] |

| AT5G51860 | 8.53 | 0.09 | K-box and MADS box transcription factor family protein (AGL72) | Y | Cell differentiation [37] |

| AT5G45380 | 8.41 | −0.09 | DEGRADATION OF UREA 3 (DUR3) | Y | Urea uptake [38] |

| AT1G34320 | 8.11 | − 0.18 | PSK SIMULATOR 1 (PSI1) | Y | Cell growth [39] |

| AT5G14470 | 7.96 | −0.19 | Galactokinase 2 (GALK2) | Y | Abiotic stress response [40] |

| AT1G64790 | 2.84 | 1.19 | ILITHYIA (ILA) | Y | Biotic stress [41] |

| AT1G66870 | 2.80 | 0.62 | Carbohydrate-binding X8 domain superfamily protein | Y | |

| AT3G48740 | 2.71 | 0.57 | Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporter 11 (SWEET11) | Y | Biotic stress [42] |

| AT3G27940 | 3.13 | 0.54 | LOB domain containing protein 26 (LBD26) | Y | Leaf development [43] |

| AT5G23660 | 2.77 | 0.53 | Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporter 12 (SWEET 12) | N | Biotic stress [42] |

| AT4G26010 | 3.68 | −0.73 | Peroxidase super family protein | Y | Abiotic stress [44] |

| AT5G38910 | 3.34 | −0.74 | RmLC-like cupins superfamily protein | Y | Abiotic stress response [45] |

| AT3G47340 | 3.28 | − 0.71 | glutamine-dependent asparagine synthase 1 (ASN1) | Y | Metabolic pathways [46] |

| AT5G08250 | 3.09 | −0.76 | Cytochrome P450 superfamily protein | N | |

| At1G34510 | 3.09 | −0.66 | Peroxidase superfamily protein | Y | Wound response [47] |

Gene expression of dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 is compared to Col-0. For each gene the level of significance and relative expression is stated, and the presence of a WRKY domain in the promotor region. The genes regulated in dsc1–1 are ranked based on significance, whereas genes regulated in wrky19–1 are presented in the following order: first the 5 most significant genes followed by the 5 genes most up-regulated and next, the 5 genes which are most down-regulated

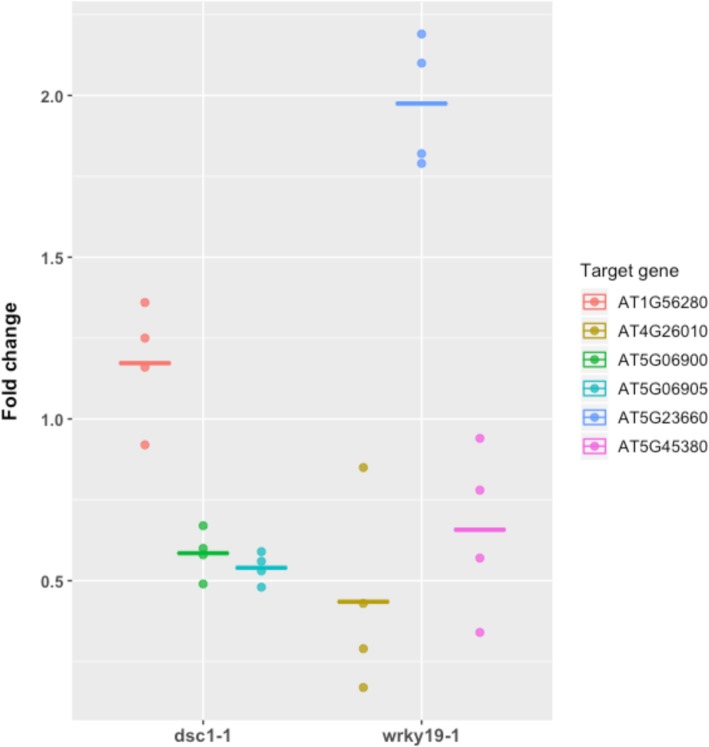

Fig. 6.

Relative expression of a selected set of genes identified in the microarray of dsc1–1 or wrky19–1 mutant plants (Table 1) relative to the wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 background as determined by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. Expression levels shown are represented as fold change measured in plants infected by M. incognita at the same time of inoculation (dpi =7). The data of each gene set consist of four biological replicates each comprising of three technical replications. Crossbar represents mean fold change

To identify genes regulated in association with WRKY19, we also analyzed the transcriptome of whole roots of the wrky19–1 mutant in non-infected and M. incognita infected plants. When comparing non-infected roots of the wrky19–1 mutant and wildtype Arabidopsis control plants, no differentially expressed genes were observed (threshold for significance -log10(P) > 3.5). As expected, the expression of WRKY19 was slightly – but not significantly – upregulated in the wrky19–1 mutant line as compared to wildtype Arabidopsis (significance -log10(P) = 1.67; relative expression 0.22). However, in nematode-infected roots we detected 1710 differently expressed genes in a comparison between wrky19–1 and wildtype Arabidopsis plants at 7 days after inoculation (Fig. 5b). Notably, the expression of DSC1 was significantly reduced in the wrky19–1 mutant (significance -log10(P) = 5.2; relative expression − 0.31). To determine which genes are greatly affected in wrky19–1, we focused on genes that were above the threshold of significance of -log10(P) > 6.5 or had a relatively large change in relative expression (relative expression < − 0.3 or > 0.3). In total, 253 differentially expressed genes matched these criteria (Additional file 4). It was noted that 13 out of the 15 most significantly regulated genes - or those with largest relative expression of wrky19–1 – contain a W-box motif ((T/A) TGAC(T/A)) in the corresponding promotor region (Table 1) consistent with a regulatory role for WRKY19 during nematode infection. Three genes from each category in Table 1 were selected for testing by qRT-PCR to confirm the observed changes in gene expression using the Arabidopsis microarray. Similar expression patterns were observed (Fig. 6), supporting the up or downregulation of the selected genes in M. incognita-infected roots of the wrky19–1 mutant at 7 dpi. Most of the genes in this subset have been linked to biotic and abiotic stresses like observed for the dsc1–1 mutant. For instance, the gene with by far the highest relative expression in wrky19–1 is ILITHYIA (ILA, At1G64790), which encodes a HEAT-repeat protein required for basal defense to Pseudomonas syringea [41].

Discussion

Previously, we mapped a QTL on chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis linked to reproductive success of M. incognita harboring two genes encoding TIR-NB-LRR proteins [26]. Although the SNP marker identified at this locus is located in BAT5, we did not find further evidence that allelic variation in this gene can be causal for variation in the number of M. incognita egg masses per plant at six weeks after inoculation (Fig. 2). Others have shown that BAT5 is associated with jasmonic acid-dependent signaling and wound responses [48], which are also relevant processes in the context of M. incognita infections [49–51]. Nevertheless, our data of the bioassays with the bat5–2 knock-out mutant makes it unlikely that BAT5 plays a significant role in regulating the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita.

After eliminating BAT5 as a candidate susceptibility factor for M. incognita infections in Arabidopsis, we focused on the TIR-NB-LRR-encoding genes DSC1 and WRKY19 to explain the phenotypic variation associated with this locus. We show that the loss of DSC1 expression in the dsc1–1 Arabidopsis mutant significantly increases the number of juveniles per plant shortly after inoculation and the number of egg masses at the end of the life cycle of M. incognita (Fig. 3). This demonstrates that allelic variation linked to DSC1 may indeed contribute to the phenotypic variation in the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita [26].

Less straightforward is the interpretation of the data from our nematode infections assays with the wrky19–1 Arabidopsis mutant. The T-DNA insert in wrky19–1 is located 191 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site of WRKY19 and 71 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site of the reversely oriented DSC1 gene. Our qRT-PCR study suggested that the wrky19–1 T-DNA insert decreases expression of DSC1 but increases expression of WRKY19 (Fig. S1). The microarray analysis shows also that DSC1 expression is significantly reduced in roots of the wrky19–1 mutant, but relative weakly. The expression of WRKY19 is also increased in this mutant as expected, but not significantly (Fig. 5b). Although the transcriptional effects on either DSC1, WRKY19 or both are mild in wrky19–1, we observe a significant phenotype in root architecture and susceptibility to M. incognita indicating that this mutation and the subsequent changes in WRKY19 and DSC1 expression has an impact on the condition of the plant.

We used transcriptome analyses by microarray to further investigate possible regulatory networks underlying the enhanced susceptibility of both dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 Arabidopsis mutants to M. incognita. Overall, we observe only a small overlap (17 genes) in the sets of differentially expressed genes in nematode-infected roots of dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 (Fig. 5c). Despite this small overlap in commonly regulated genes, we note that both sets are enriched for genes with a regulatory W-box in their putative promoter sequences (Table 1). The W-box is thought to be the consensus of the DNA binding site of WRKY domains of WRKY transcription factors [52]. The overrepresentation of the W-box could indicate that the regulation of these genes is indeed under control of the WRKY domain present in WRKY19. However, as we did not observe a major change in WRKY19 expression in nematode-infected roots of the wrky19–1 mutant as compared to wildtype Arabidopsis, this needs further investigation.

Another striking observation is the number of differentially expressed genes in nematode-infected roots of both dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 related to responses to abiotic stress (Table 1). This is in line with data from our earlier multi-trait genome wide association study showing that the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita cross-correlates with responses to osmotic stress [53]. Likewise, we have recently shown that the transcription factor ERF6, which functions as a mediator of abiotic stress, is also required for susceptibility of Arabidopsis to M. incognita [26]. Altogether, these findings suggest that the ability to mitigate abiotic stress is one of the key regulating factors in susceptibility of the Arabidopsis to M. incognita.

The fact that many of the genes differentially regulated in the dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 mutants upon M. incognita infection have been linked to plant defense and responses to abiotic stress before might not be surprising. It is clear that nematode-infections are likely to cause stress in Arabidopsis roots. Furthermore, it has already been shown that DSC1 functions in plant immunity [28]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge this is the first time that DSC1 can be linked to immunity to plant parasitic nematodes. DSC1 is a dominant suppressor of the calmodulin-binding transcription activator CAMTA3, which regulates resistance to various pathogens [54, 55]. The loss of DSC1 could increase the activity of CAMTA3 in nematode-infected roots of the dsc1–1 mutant, leading to suppression of defense responses. However, no changes in CAMTA3 expression was detected in the transcriptome data to support this model (data not shown). How DSC1 contributes to nematode defense needs further investigations.

Although, we cannot directly pinpoint the probable cause for the enhanced susceptibility of the wrky19–1 mutant to M. incognita, our analyses of the transcriptome of nematode-infected roots of this mutant reveal a remarkably strong upregulation of the defense related gene ILITYHIA (ILA). ILA encodes a HEAT repeat protein, which is required for basal defense, resistance mediated by a subset of CC- and TIR-NB-LRR proteins, and systemic acquired resistance against Pseudomonas syringae [41]. ILA has not been linked to susceptibility of Arabidopsis to nematodes before, but the relative expression level of this gene in the microarray analyses is so high (relative expression of 1.19) that it could in fact be causal to the increased susceptibility of the wrky19–1 mutant to M. incognita.

TIR-NB-LRR encoding genes can confer dominant disease resistance to Arabidopsis [56], but our data on the role of DSC1 and WRKY19 in nematode-infected roots does not point into that direction. First of all, the relatively low level of significance and small effect size of SNP marker 138,442 do not fit the typical dominant phenotype of a major resistance based on TIR-NB-LRR type R genes. Second, the differences in reproductive success of M. incognita on the dsc1–1 knock-out mutant and the wrky19–1 overexpressing mutant as compared to wildtype Arabidopsis plants were significant, but relatively small, and unlike major disease resistance responses conferred by R genes. We therefore conclude that DSC1 and WRKY19, either separately or together as a pair, do not confer major resistance against M. incognita in Arabidopsis to the population tested. Instead, they are most likely involved in basal immunity to root-knot nematodes during early stages of the compatible interaction with Arabidopsis as a host plant.

A role for DSC1 and WRKY19 in basal immunity is consistent with observations by others that DSC1 transcript levels increase upon application of SA (salicylic acid) or flg22 (flagellin 22) [57] and that WRKY19 is thought to be an early component in regulatory networks of PTI [58]. Likewise, other TIR-NB-LRR proteins have been found to contribute to basal defense in Arabidopsis against Pseudomonas syringae (TN13) and the hemibiotrophic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans (RLM3) [59, 60]. Furthermore, the head-to-head genomic orientation of DSC1 and WKRY19 could indicate that they form an immune receptor pair [56, 57, 61]. So far, other R-gene pairs have been identified in Arabidopsis consisting of two tightly linked NB-LRR coding genes located in a similar head-to-head tandem arrangement [61]. For instance, the genomic organization of DSC1 and WRKY19 pair shows much similarity with that of the resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum RRS1 and the resistance gene to Pseudomonas syringae RPS4 suggesting that they may act as a TIR-NB-LRR pair in plant immunity [56, 57, 61]. This is further supported by the similarities in protein architecture including the presence of functional domains required for immune receptor activity like the NB-ARC and LRR domain [62].

Conclusion

Here, we provide first evidence for a functional role of DCS1 and WRKY19 in basal plant immunity to a plant pathogen as a TIR-NB-LRR gene pair. It will be interesting to investigate whether DSC1 and WRKY19 form indeed a functional protein complex and how this complex contributes to basal immunity in plants to root-knot nematodes.

Methods

Plant material

The following homozygous Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutant lines were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre [63]: SALK_145043 with T-DNA insert in At4G12010 (dsc1–1); SALK_014300 with T-DNA in At4G12020 (wrky19–1); SALK_201408 with T-DNA in At4G12030 (bat5–2). The T-DNA insert lines were all generated in the background of Columbia-0 (Col-0 N60000), which was used as wildtype Arabidopsis throughout this study.

The presence and homozygosity of the T-DNA insert in the mutant lines was verified with PCR on genomic DNA isolated from leaf material of twelve seedlings [27]. The detection of the wild type allele or the T-DNA insert by PCR was performed as previous described [26] with different combination of primers for each line (Additional file 5) and the T-DNA-insert specific Lbl3.1 primer [63].

The expression of the T-DNA insertion affected gene was checked with reverse transcription quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR), the RNA was isolated as previous described [26]. To quantify the expression level for the gene of interest we used a gene specific forward and reverse primer (Table S1). For the qRT-PCR we used conditions as described below for gene expression analysis. Relative expression ratio between the gene of interest and the reference gene was calculated as described elsewhere [64].

Nematode bioassay

Eggs of Meloidogyne incognita were obtained by treating tomato roots infected with M. incognita (strain ‘Morelos’ from INRA, Sophia Antipolis, France) as described [27].

To test the susceptibility of Arabidopsis seedlings, seeds were vapour sterilized and grown as described previously [27]. Individual seedlings were inoculated with 180 infective J2s of M. incognita per plant and incubated at 24 °C in the dark. The number of egg masses per plant were counted six weeks after inoculation by visually inspecting the roots with a dissection microscope. Each Arabidopsis genotype was tested in at least three independent experiments and 18 replicates per experiment. The obtained values were batch-corrected using the following equation: variable corrected = variable + (total mean (variable) - batch mean (variable)). The differences in counts per plants were statistically analysed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Tukey HSD test in R (version 3.0.2, www.r-project.org).

To collect roots of infected and non-infected Arabidopsis seedlings for gene expression analyses with microarrays and qRT-PCR, seeds were treated as described above for the susceptibility test. Seedlings were grown and inoculated and sampled as described [26].

Root phenotype

The root phenotype of Arabidopsis seedlings was determined as described [26]. Differences in the total root length per seedling in cm and number of root tips were statistically analysed with a two-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD test in R (p < 0.05).

Gene expression analysis

Expression analysis for genes of interest was performed on the stored root samples produced during the nematode infection study. Whole root systems were cut from aerial parts of the seedlings and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated from whole roots of twelve 14-days-old plants of dsc1–1, wrky19–1, bat5–2 and Col-0 wildtype. The RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis for quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) from the roots was performed as described [26]. cDNA matching Arabidopsis thaliana elongation factor 1 alpha was amplified as a reference for constitutive expression using primers as indicated in Table S1 [65]. To quantify the expression level for the gene of interest specific gene primers were used (Table S1 & S2). The efficiencies of these primer sets were tested prior to the qRT-PCR analysis. For the qRT-PCR 5 ng cDNA was used with the following conditions: 15 min at 95 °C, forty cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 62 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C, and a final incubation of 5 min at 72 °C. Relative expression ratio between the gene of interest and the reference gene was calculated as described elsewhere [64]. Relative expression ratio was statistically analysed for significance and compared with a student t-test (P-value< 0.05).

For microarray analysis, approximately 200 ng of total RNA of each sample of Col-0, dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 were used for gene expression analysis on an Arabidopsis V4 Gene Expression Microarray (4x44K, Agilent Technologies). The microarray was performed as described i [26]. Two sets of data were generated: a set for comparison between Col-0 and dsc1–1 and a set for the comparison between Col-0 and wrky19–1. The different sets for Col-0 contained different experimental samples. Each sample had at least three biological replicates.

Microarray analysis

After scanning, the spot intensities of the microarrays were not background corrected [66]. Gene expression profiles were normalized using the Loess (within array normalization) and the quantile method (between array normalization) [67] in the Bioconductor Limma package [68]. The normalized intensities were log2-transformed for further analysis.

A linear model was used to identify differentially expressed genes in a side-by-side comparison. The following treatments were compared: day-0 control Col-0 versus mutant, day 7 control Col-0 versus mutant, day 7 infected Col-0 versus infected mutant, and day 7 control Col-0 versus infected Col-0. Each treatment consisted of three biological replicates. We used the linear model

where the log2-normalized expression (E) of spot i (i in 1, 2, ..., 45,220) was explained over treatment (T). Afterwards, the obtained significances were corrected for multiple testing using the FDR procedure in p.adjust [69].

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Confirmation of T-DNA insert in line bat5–2, dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 with PCR. A, allele specific PCRs on genomic DNA isolated from each Arabidopsis mutant line. PCR amplification products using primer combinations for only the wildtype gene allele (P1) and for the wildtype allele including the T-DNA insert (P2). B-D, Relative gene expression of the genes harbouring the T-DNA insert in the mutant lines as compared to the wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 using quantitative RT-PCR on roots of 14-day old seedlings. B, represents the relative gene expression of BAT5 in bat5–2. C, represents the relative gene expression of DSC1 in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1. D, represents the relative gene expression of WKRY19 in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1. Data (B-D) was generated with three independent biological replicates with three technical replicates each.

Additional file 2 Number of root tips for bat5–2 on 14-day-old seedlings. Statistically tested with ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test (p = 0.05). Data represents two biological replicates.

Additional file 3 The number of root tips for dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 on 14 day old seedlings. Statistically tested with ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test (p = 0.05); letters determine the group based on the level of significance. Data represents three biological replicates.

Additional file 4 245 regulated genes in wrky19–1 during M. incognita infection with significance > 7 or with a relative expression of <− 0.3 or > 0.03.

Additional file 5. Overview of primers used in qRT-PCR and for confirmation of T-DNA insert.

Additional file 6. Overview of primers used in qRT-PCR for a set of selected genes in Table 1

Acknowledgments

The PhD thesis by Sonja Warmerdam entitled “Susceptibility genes, a novel strategy to improve resistance against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita” (2019) of the Wageningen University under supervision of prof. dr. J. Bakker (promoter) and dr. G. Smant and dr. A. Goverse (co-promoters) - ISBN 9789463435949 - p161 includes a chapter which was used as a draft of this paper and as such, submitted as a slightly modified version to BMC Plant Biology for publication.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BAK1

BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1)-associated receptor kinase 1

- BAT5

BILE ACID TRANSPORTER 5

- CAMTA3

Calmodulin-binding transcription activator number 3

- CC

Coiled-coil domain

- DSC1

DOMINANT SUPPRESSOR OF Camta 3 NUMBER 1 immune receptor

- flg22

Flagellin 22

- GWA

Genome-wide association

- HEAT repeat

Acronym for a structural motif present in the four proteins Huntingtin, elongation factor 3 (EF3), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and the yeast kinase TOR1

- ILA

HEAT repeat protein ILITYHIA (after the Greek goddess of childbirth)

- MAPx

MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE

- Mi-1.2 gene

Meloidogyne incognita resistance gene number 1.2

- NB-LRR

Nucleotide-binding site (NB) leucine-rich repeat (LRR) immune receptor

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

- QTL

Quantitative Trait Locus

- R gene

Resistance gene

- RLM3

Resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans 3

- RPS4

Resistance to Pseudomonas syringae 4

- RRS1

Resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum 1

- SA

Salicylic acid

- S-gene

Susceptibility gene

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- T-DNA

Transfer DNA

- TIR

Toll-Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR)-like domain

- TN13

TIR-NBS protein number 13

- W-box

WRKY binding motif

- WRKY

Conserved WRKY amino acid signature sequence

- WRKY19

TIR-NB-LRR-WRKY-MAPx domain containing protein number 19

Authors’ contributions

J.B., G.S., A.G. and S.W. conceived and designed the experiments. S.W., M.S., O.C.A.S., M.E.P.O., C.C.v S. and J.L.L.T. performed the experiments. S.W., M.S., O.C.A.S., J.L.L.T., A.G., J.B. and G.S analyzed the data. S.W., M.S., O.C.A.S., J.B., G.S. and A.G. wrote the article. All authors edited and approved the final article.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, Perspectives Programme ‘Learning from Nature to Protect Crops’; STW grant 10997).

Availability of data and materials

All microarray data were deposited in the ArrayExpress database at EMBL-EBI (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-6897. All other data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sonja Warmerdam, Email: Sonja.warmerdam@wur.nl.

Mark G. Sterken, Email: Mark.sterken@wur.nl

Octavina C. A. Sukarta, Email: octavina.sukarta@wur.nl

Casper C. van Schaik, Email: Casper.vanschaik@wur.nl

Marian E. P. Oortwijn, Email: Marian.oortwijn@wur.nl

Jose L. Lozano-Torres, Email: Jose.lozano-torres@wur.nl

Jaap Bakker, Email: Jaap.bakker@wur.nl.

Geert Smant, Email: Geert.smant@wur.nl.

Aska Goverse, Email: Aska.Goverse@wur.nl.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-020-2285-x.

References

- 1.Bebber DP, Holmes T, Gurr SJ. The global spread of crop pests and pathogens. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2014;23(12):1398–1407. doi: 10.1111/geb.12214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gheysen G, Mitchum MG. How nematodes manipulate plant development pathways for infection. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14(4):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goverse A, Smant G. The activation and suppression of plant innate immunity by parasitic nematodes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2014;52(1):243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantelin S, Thorpe P, Jones JT. Suppression of plant Defences by plant-parasitic nematodes. Adv Bot Res. 2015;73:325–337. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2014.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caillaud M-C, Dubreuil G, Quentin M, Perfus-Barbeoch L, Lecomte P, de Almeida EJ, Abad P, Rosso M-N, Favery B. Root-knot nematodes manipulate plant cell functions during a compatible interaction. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(1):104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escobar C, Barcala M, Cabrera J, Fenoll C. Overview of root-knot nematodes and Giant cells. Adv Bot Res. 2015;73:1–32. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook DE, Mesarich CH, Thomma BPHJ. Understanding plant immunity as a surveillance system to detect invasion. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2015;53(1):541–563. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080614-120114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444(7117):323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manosalva P, Manohar M, von Reuss SH, Chen S, Koch A, Kaplan F, Choe A, Micikas RJ, Wang X, Kogel K-H, et al. Conserved nematode signalling molecules elicit plant defenses and pathogen resistance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7795. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira MA, Wei L, Kaloshian I. Root-knot nematodes induce pattern-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. New Phytol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Lozano-Torres JL, Wilbers RHP, Warmerdam S, Finkers-Tomczak A, Diaz-Granados A, van Schaik CC, Helder J, Bakker J, Goverse A, Schots A, et al. Apoplastic venom allergen-like proteins of cyst nematodes modulate the activation of basal plant innate immunity by cell surface receptors. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(12):e1004569. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaouannet M, Magliano M, Arguel MJ, Gourgues M, Evangelisti E, Abad P, Rosso MN. The root-knot nematode Calreticulin mi-CRT is a key effector in plant defense suppression. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2012;26(1):97–105. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-12-0130-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Shiyan, Chronis Demosthenis, Wang Xiaohong. The novel GrCEP12 peptide from the plant-parasitic nematodeGlobodera rostochiensissuppresses flg22-mediated PTI. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2013;8(9):e25359. doi: 10.4161/psb.25359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C, Liu S, Liu Q, Niu J, Liu P, Zhao J, Jian H. An ANNEXIN-like protein from the cereal cyst nematode Heterodera avenae suppresses plant defense. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson VM, Kumar A. Nematode resistance in plants: the battle underground. Trends Genet. 2006;22(7):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zipfel C. Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(7):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boller T, Felix G. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60(1):379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takken FLW, Goverse A. How to build a pathogen detector: structural basis of NB-LRR function. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15(4):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson VM. Root-knot nematode resistance genes in tomato and their potential for future use. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36(1):277–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claverie M, Dirlewanger E, Bosselut N, Van Ghelder C, Voisin R, Kleinhentz M, Lafargue B, Abad P, Rosso MN, Chalhoub B, et al. The Ma gene for complete-spectrum resistance to Meloidogyne species in Prunus is a TNL with a huge repeated C-terminal post-LRR region. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(2):779–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu X, Xiao K, Cui H, Hu J. Overexpression of the Prunus sogdiana NBS-LRR Subgroup Gene PsoRPM2 Promotes Resistance to the Root-Knot Nematode Meloidogyne incognita in Tobacco. Front Microbiol. 2017:8(2113). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Williamson VM. Plant nematode resistance genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2(4):327–331. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi M, Goggin FL, Milligan SB, Kaloshian I, Ullman DE, Williamson VM. The nematode resistance gene mi of tomato confers resistance against the potato aphid. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(17):9750–9754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devran Z, Söğüt MA. Occurrence of virulent root-knot nematode populations on tomatoes bearing the mi gene in protected vegetable-growing areas of Turkey. Phytoparasitica. 2010;38(3):245–251. doi: 10.1007/s12600-010-0103-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaloshian I, Williamson VM, Miyao G, Lawn DA, Westerdahl BB. "resistance-breaking" nematodes identified in California tomatoes. Calif Agric. 1996;50(6):18–19. doi: 10.3733/ca.v050n06p18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warmerdam S, Sterken MG, Van Schaik C, Oortwijn MEP, Lozano-Torres JL, Bakker J, Goverse A, Smant G. Mediator of tolerance to abiotic stress ERF6 regulates susceptibility of Arabidopsis to Meloidogyne incognita. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20(1):137–152. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warmerdam S, Sterken MG, van Schaik C, Oortwijn MEP, Sukarta OCA, Lozano-Torres JL, Dicke M, Helder J, Kammenga JE, Goverse A, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of the architecture of susceptibility to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2018;218(2):724–737. doi: 10.1111/nph.15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lolle S, Greeff C, Petersen K, Roux M, Jensen MK, Bressendorff S, Rodriguez E, Sømark K, Mundy J, Petersen M. Matching NLR Immune Receptors to Autoimmunity in camta3 Mutants Using Antimorphic NLR Alleles. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(4):518–529. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(5):247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim BH, Kim SY, Nam KH. Genes encoding plant-specific class III peroxidases are responsible for increased cold tolerance of the brassinosteroid-insensitive 1 mutant. Mol Cells. 2012;34(6):539–548. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Zhang W-Z, Song L-F, Zou J-J, Su Z, Wu W-H. Transcriptome analyses show changes in gene expression to accompany pollen germination and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;148(3):1201. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oono Y, Seki M, Satou M, Iida K, Akiyama K, Sakurai T, Fujita M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Monitoring expression profiles of Arabidopsis genes during cold acclimation and deacclimation using DNA microarrays. Funct Integr Genomics. 2006;6(3):212–234. doi: 10.1007/s10142-005-0014-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chini A, Fonseca S, Fernández G, Adie B, Chico JM, Lorenzo O, García-Casado G, López-Vidriero I, Lozano FM, Ponce MR, et al. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2007;448(7154):666. doi: 10.1038/nature06006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen F, D'Auria JC, Tholl D, Ross JR, Gershenzon J, Noel JP, Pichersky E. An Arabidopsis thaliana gene for methylsalicylate biosynthesis, identified by a biochemical genomics approach, has a role in defense. Plant J. 2003;36(5):577–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu W-X, Zhang F-C, Zhang W-Z, Song L-F, Wu W-H, Chen Y-F. Arabidopsis Di19 functions as a transcription factor and modulates PR1, PR2, and PR5 expression in response to drought stress. Mol Plant. 2013;6(5):1487–1502. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ascencio-Ibáñez JT, Sozzani R, Lee T-J, Chu T-M, Wolfinger RD, Cella R, Hanley-Bowdoin L. Global analysis of Arabidopsis gene expression uncovers a complex Array of changes impacting pathogen response and cell cycle during Geminivirus infection. Plant Physiol. 2008;148(1):436–454. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.121038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorca-Fornell C, Gregis V, Grandi V, Coupland G, Colombo L, Kater MM. The Arabidopsis SOC1-like genes AGL42, AGL71 and AGL72 promote flowering in the shoot apical and axillary meristems. Plant J. 2011;67(6):1006–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zanin L, Tomasi N, Wirdnam C, Meier S, Komarova NY, Mimmo T, Cesco S, Rentsch D, Pinton R. Isolation and functional characterization of a high affinity urea transporter from roots of Zea mays. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stührwohldt N, Hartmann J, Dahlke RI, Oecking C, Sauter M. The PSI family of nuclear proteins is required for growth in arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;86(3):289–302. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Q, Yu D, Chang H, Guo X, Yuan C, Hu S, Zhang C, Wang P, Wang Y. Regulation and function of Arabidopsis AtGALK2 gene in abscisic acid response signaling. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(12):6605–6612. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2773-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monaghan J, Li X. The HEAT repeat protein ILITYHIA is required for plant immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(5):742–753. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walerowski P, Gündel A, Yahaya N, Truman W, Sobczak M, Olszak M, Rolfe SA, Borisjuk L, Malinowski R: Clubroot Disease Stimulates Early Steps of Phloem Differentiation and Recruits SWEET Sucrose Transporters within Developing Galls. Plant Cell 2018:tpc.00283.02018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Matsumura Y, Iwakawa H, Machida Y, Machida C. Characterization of genes in the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2/LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES (AS2/LOB) family in Arabidopsis thaliana, and functional and molecular comparisons between AS2 and other family members. Plant J. 2009;58(3):525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renault H, El Amrani A, Berger A, Mouille G, Soubigou-Taconnat L, Bouchereau A, Deleu C. Gamma-Aminobutyric acid transaminase deficiency impairs central carbon metabolism and leads to cell wall defects during salt stress in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36(5):1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/pce.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swindell WR. The association among gene expression responses to nine abiotic stress treatments in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2006;174(4):1811–1824. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaufichon L, Marmagne A, Belcram K, Yoneyama T, Sakakibara Y, Hase T, Grandjean O, Clément G, Citerne S, Boutet-Mercey S, et al. ASN1-encoded asparagine synthetase in floral organs contributes to nitrogen filling in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant J. 2017;91(3):371–393. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taki N, Sasaki-Sekimoto Y, Obayashi T, Kikuta A, Kobayashi K, Ainai T, Yagi K, Sakurai N, Suzuki H, Masuda T, et al. 12-Oxo-Phytodienoic acid triggers expression of a distinct set of genes and plays a role in wound-induced gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139(3):1268–1283. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gigolashvili T, Yatusevich R, Rollwitz I, Humphry M, Gershenzon J, Flügge U-I. The Plastidic Bile acid transporter 5 is required for the biosynthesis of methionine-derived Glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21(6):1813–1829. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooper WR, Jia L, Goggin L. Effects of Jasmonate-induced defenses on root-knot nematode infection of resistant and susceptible tomato cultivars. J Chem Ecol. 2005;31(9):1953–1967. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-6070-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou J, Jia F, Shao S, Zhang H, Li G, Xia X, Zhou Y, Yu J, Shi K. Involvement of nitric oxide in the jasmonate-dependent basal defense against root-knot nematode in tomato plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:193. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holbein J, Grundler FMW, Siddique S. Plant basal resistance to nematodes: an update. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(7):2049–2061. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciolkowski I, Wanke D, Birkenbihl RP, Somssich IE. Studies on DNA-binding selectivity of WRKY transcription factors lend structural clues into WRKY-domain function. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;68(1–2):81–92. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thoen MP, Davila Olivas NH, Kloth KJ, Coolen S, Huang PP, Aarts MG, Bac-Molenaar JA, Bakker J, Bouwmeester HJ, Broekgaarden C, et al. Genetic architecture of plant stress resistance: multi-trait genome-wide association mapping. New Phytol. 2017;213(3):1346–1362. doi: 10.1111/nph.14220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen C, Yang Y, Du L, Wang H. Calmodulin-binding transcription activators and perspectives for applications in biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(24):10379–10385. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du L, Ali GS, Simons KA, Hou J, Yang T, Reddy ASN, Poovaiah BW. Ca2+/calmodulin regulates salicylic-acid-mediated plant immunity. Nature. 2009;457:1154. doi: 10.1038/nature07612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narusaka M, Shirasu K, Noutoshi Y, Kubo Y, Shiraishi T, Iwabuchi M, Narusaka Y. RRS1 and RPS4 provide a dual resistance-gene system against fungal and bacterial pathogens. Plant J. 2009;60(2):218–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR–encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(4):809–834. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Birkenbihl RP, Kracher B, Ross A, Kramer K, Finkemeier I, Somssich IE. Principles and characteristics of the Arabidopsis WRKY regulatory network during early MAMP-triggered immunity. Plant J. 2018;96(3):487–502. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staal J, Dixelius C. RLM3, a potential adaptor between specific TIR-NB-LRR receptors and DZC proteins. Commun Integr Biol. 2008;1(1):59–61. doi: 10.4161/cib.1.1.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth C, Ludke D, Klenke M, Quathamer A, Valerius O, Braus GH, Wiermer M. The truncated NLR protein TIR-NBS13 is a MOS6/IMPORTIN-alpha3 interaction partner required for plant immunity. Plant J. 2017;92(5):808–821. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cesari S, Bernoux M, Moncuquet P, Kroj T, Dodds PN. A novel conserved mechanism for plant NLR protein pairs: the “integrated decoy” hypothesis. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:606. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma Y, Guo H, Hu L, Martinez PP, Moschou PN, Cevik V, Ding P, Duxbury Z, Sarris PF, Jones JDG. Distinct modes of derepression of an <em>Arabidopsis</em> immune receptor complex by two different bacterial effectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(41):10218–10227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811858115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. Genome-wide Insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301(5633):653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Czechowski T, Bari RP, Stitt M, Scheible W-R, Udvardi MK. Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant J. 2004;38(2):366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zahurak M, Parmigiani G, Yu W, Scharpf RB, Berman D, Schaeffer E, Shabbeer S, Cope L. Pre-processing Agilent microarray data. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8(1):142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31(4):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Confirmation of T-DNA insert in line bat5–2, dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 with PCR. A, allele specific PCRs on genomic DNA isolated from each Arabidopsis mutant line. PCR amplification products using primer combinations for only the wildtype gene allele (P1) and for the wildtype allele including the T-DNA insert (P2). B-D, Relative gene expression of the genes harbouring the T-DNA insert in the mutant lines as compared to the wildtype Arabidopsis Col-0 using quantitative RT-PCR on roots of 14-day old seedlings. B, represents the relative gene expression of BAT5 in bat5–2. C, represents the relative gene expression of DSC1 in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1. D, represents the relative gene expression of WKRY19 in dsc1–1 and wrky19–1. Data (B-D) was generated with three independent biological replicates with three technical replicates each.

Additional file 2 Number of root tips for bat5–2 on 14-day-old seedlings. Statistically tested with ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test (p = 0.05). Data represents two biological replicates.

Additional file 3 The number of root tips for dsc1–1 and wrky19–1 on 14 day old seedlings. Statistically tested with ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test (p = 0.05); letters determine the group based on the level of significance. Data represents three biological replicates.

Additional file 4 245 regulated genes in wrky19–1 during M. incognita infection with significance > 7 or with a relative expression of <− 0.3 or > 0.03.

Additional file 5. Overview of primers used in qRT-PCR and for confirmation of T-DNA insert.

Additional file 6. Overview of primers used in qRT-PCR for a set of selected genes in Table 1

Data Availability Statement

All microarray data were deposited in the ArrayExpress database at EMBL-EBI (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-6897. All other data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.