Abstract

Point mutations in cysteine string protein-α (CSPα) cause dominantly inherited adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (ANCL) – a rapidly progressing and lethal neurodegenerative disease with no treatment. ANCL mutations are proposed to trigger CSPα aggregation/oligomerization, but the mechanism of oligomer formation remains unclear. Here we use purified proteins, mouse primary neurons, and patient-derived induced neurons, to show that the normally palmitoylated cysteine string region of CSPα loses palmitoylation in ANCL mutants. This allows oligomerization of mutant CSPα via ectopic binding of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters. The resulting oligomerization of mutant CSPα causes its mislocalization, and consequent loss of its synaptic SNARE-chaperoning function. We then find that pharmacological iron-chelation mitigates the oligomerization of mutant CSPα, accompanied by partial rescue of the downstream SNARE-defects and the pathological hallmark of lipofuscin accumulation. Thus, the iron-chelators deferiprone (L1) and deferoxamine (Dfx), already in human use for treating iron-overload, offer a novel approach for treating ANCL.

INTRODUCTION

CSPα is a DnaJ co-chaperone, which is palmitoylated in its eponymous cysteine string to mediate membrane targeting (1). This membrane binding is presumably useful in its targeting to synaptic membranes and in recruiting a chaperone complex containing Hsc70 (heat shock cognate 70 kDa) and SGT (small glutamine rich tetratricopeptide repeat containing protein) to its synaptic membrane-bound substrate SNAP-25, which is also palmitoylated (2, 3). The CSPα/Hsc70/SGT chaperone complex stabilizes SNAP-25 to facilitate the formation of synaptic SNARE-complexes, which are necessary for fusion of synaptic vesicles with the plasma membrane and neurotransmitter release (3, 4).

Two mutations within the cysteine string region of CSPα (L115R and L116Δ) were found to cause adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (ANCL) (5–7). ANCL, also known as autosomal dominant Kufs disease and Parry disease, is a lysosomal lipofuscin-storage disorder with onset at 30-40 years of age, followed by progressive neurodegeneration and expected post-diagnosis survival of 8-12 years, and no available treatment (8). Subsequent to the discovery of ANCL mutations in CSPα, two observations were reported in how these mutations may disrupt CSPα function: first, palmitoylation is reduced by both mutations (6, 9, 10), and second, both mutations cause oligomerization/aggregation of the protein (9–12). Yet, how loss of palmitoylation is connected to oligomerization of the mutant proteins remains unclear; oligomerization is proposed to be palmitoylation-dependent (11, 12) as well as palmitoylation-independent (10).

Here we identify a molecular mechanism of CSPα oligomerization due to ANCL-causing mutations: We provide evidence that reduced palmitoylation of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ mutant proteins allows them to bind Fe-S clusters, leading to oligomerization. Importantly, we show that iron-chelators can reduce this oligomerization and promote palmitoylation of mutant CSPα in primary neurons and in patient-derived induced neurons, ameliorating downstream phenotypes.

RESULTS

ANCL mutations in CSPα lead to its reduced palmitoylation and oligomerization via Fe-S cluster-binding

We first studied the effect of ANCL mutations on CSPα in vitro, using recombinant proteins. Visual analysis of purified CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ showed an amber-brown color, suggesting metal-binding, possibly via cysteine (Cys) residues of the Cys-string (Fig. 1a inset). Substitution of 13 Cys residues of the Cys-string to serines, termed serine string protein-α (SSPα), led to colorless protein (Fig. 1a inset), suggesting that the Cys-string is coordinating the bound metal. X-ray fluorescence identified the metal bound to CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ as iron, which is absent from SSPα (Fig. 1a).

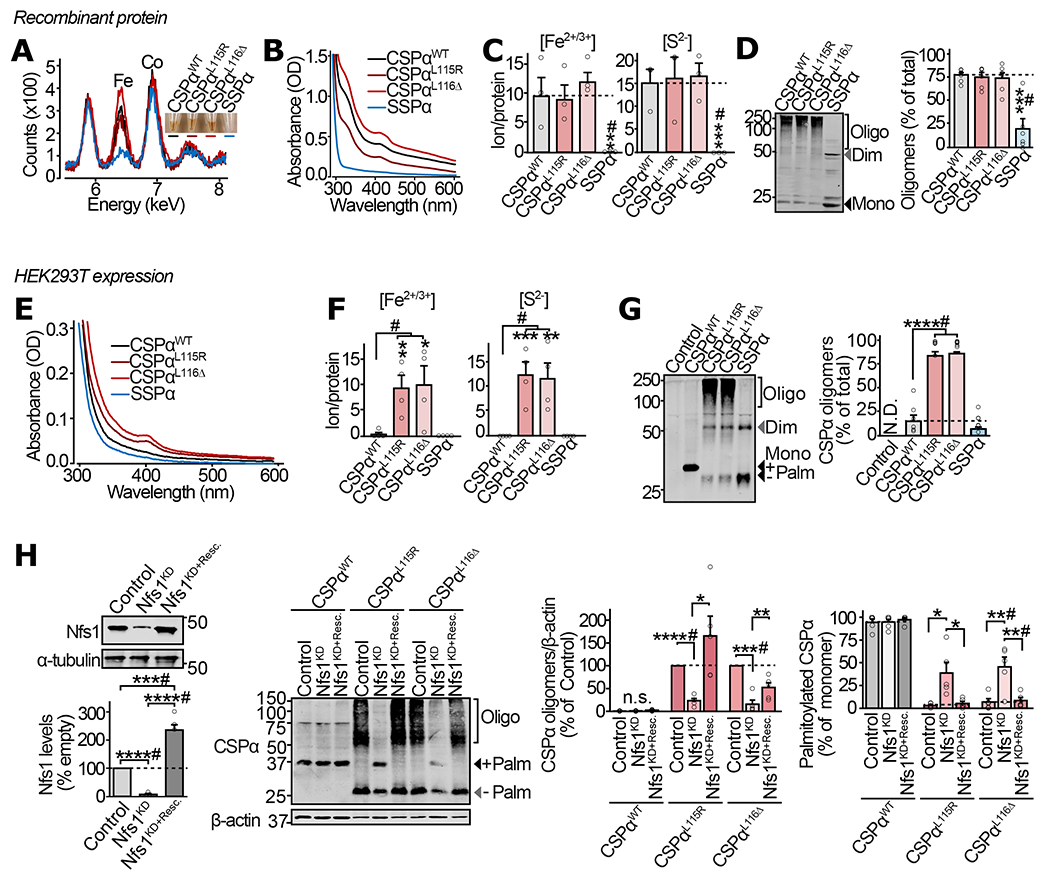

Figure 1 |. Fe-S cluster binding and oligomerization of CSPα in vitro and in mammalian cells.

(a-d) From purified recombinant proteins: (a) Color of purified CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ, and SSPα (inset), and detection of Fe in these protein solutions by X-ray fluorescence. (b) UV-Vis absorbance spectra of the indicated versions of the purified CSPα protein. (c) Fe2+/3+ ion content, measured in indicated protein by ferrozine colorimetry (left), and S2− content measured by methylene blue colorimetry (right). (d) Oligomerization of the indicated protein measured by SDS-PAGE separation and quantitative immunoblotting against CSPα (left), shown as % of total protein in each lane (right). (e-h) From HEK293T cells expressing myc-tagged CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ and SSPα: (e) UV-Vis absorbance spectra of indicated proteins immunoprecipitated using anti-myc antibody and eluted by trypsinization. (f) Fe2+/3+ ion content (left) and S2− content (right), measured as in (c), on the indicated protein immunoprecipitated and eluted as in (e). (g) Oligomerization of indicated CSPα variants was measured by SDS-PAGE separation and quantitative immunoblotting against CSPα. Representative immunoblot (left), and quantitation as % of the total protein detected in corresponding lane (right); Control = empty plasmid; N.D. = not detected. (h) Oligomerization and palmitoylation of CSPα variants, with Nfs1 knockdown (Nfs1KD), and rescue of knockdown by overexpression of shRNA-resistant Nfs1 (Nfs1KD+Resc.). In (d, g-h), Mono = monomer; Dim = dimer; Oligo = oligomers of higher mass than dimer; Palm = palmitoylated. Data are from (a) representative synchrotron measurement from n=3, (b) representative from n=4 , (c) n=3, and (d) n=6, where n is independent protein-purification; (e) representative from n=3 immunoprecipitations, (f) n=4 immunoprecipitations, (g) n=6 transfections, and (h) n=5 transfections. In (c-d) and (f-h) data represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t-test. #P<0.05 by Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U test. Uncropped blots are shown in Source Data Fig 1.

Cys-dependent iron-binding often indicates coordination of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, which is detectable by spectrometry. UV-Vis spectrometry detected peaks at ~330 nm and ~417 nm, characteristic of Fe-S clusters (13), in CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ, but not in SSPα (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the Cys-string is coordinating Fe-S clusters. Accordingly, upon acid treatment which disrupts Fe-S clusters, the amber-brown proteins lost color and their UV-Vis peaks were reduced (Supplementary Fig. S1a).

Ferrous/ferric iron (Fe2+/3+) as well as inorganic sulfide (S2−) ions bound to CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ were quantified as ~10 Fe2+/3+ and ~15 S2− ions per protein molecule (Fig. 1c). Neither Fe2+/3+ nor S2− ions were detected in SSPα samples (Fig. 1c), suggesting that CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ interact with Fe-S clusters via the Cys-string.

Since Fe-S clusters can covalently bridge protein monomers to cause oligomerization (14, 15), we hypothesized that cross-linking by Fe-S clusters may be the mechanism of mutant CSPα oligomerization. We thus measured the SDS-resistant oligomerization status of CSPα variants. Recombinant CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ oligomerized into large aggregates, while SSPα was mostly monomeric, with some dimer formation (Fig. 1d). Oligomers of CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ were disassembled into smaller oligomers and monomers, almost completely by acid treatment, while L-cysteine had no significant effect (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Limited proteolysis experiments in native conditions found that CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ are more resistant to trypsin cleavage than SSPα (Supplementary Fig. S1c), suggesting seclusion of trypsin cleavage-sites in the oligomers. Accordingly, acid treatment made CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ similarly susceptible to trypsin cleavage as SSPα (Supplementary Fig. S1d).

These results from recombinant proteins suggest that CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ oligomerize by Fe-S cluster-binding via their Cys-string regions. However, in eukaryotic cells, the Cys residues of CSPα’s Cys-string are heavily palmitoylated (16), bringing the Cys-string into close apposition with lipid membranes, which may obviate their reaction with Fe-S clusters.

Therefore, we expressed CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ and SSPα in HEK293T cells. As previously reported (1, 10), ~90% of CSPαWT was palmitoylated, while the ANCL mutants CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ revealed severely reduced palmitoylation (Supplementary Fig. S1e), detected by the mass-shift due to chemical depalmitoylation by hydroxylamine. When isolated by immunoprecipitation, only CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ showed the signature peaks of Fe-S clusters, while CSPαWT and SSPα lacked these peaks (Fig. 1e). Acid treatment eliminated the signature of Fe-S clusters in the UV-Vis profiles of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ (Supplementary Fig. S1f). Fe2+/3+ and inorganic S2− were detected only in CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ, with Fe:S ratios near 0.75-0.9 (Fig. 1f), pointing to Fe-S cluster binding specifically by the ANCL mutants of CSPα via their Cys-string in HEK293T cells. This binding of Fe-S clusters specifically to CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ was accompanied by their oligomerization, while CSPαWT and SSPα did not form oligomers (Fig. 1g).

These oligomers of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ were not sensitive to the reducing agents L-cysteine and DTT, but were partially disassembled by reducing agent dithionite and oxidant H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. S1g). DTT-insensitivity also suggested that the high molecular mass oligomers are not cross-linked via disulfide bonds. Polyubiquitination of CSPα mutants could also resemble oligomers on SDS-PAGE, however ubiquitination levels were similar between CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ (Supplementary Fig. S1h); with ubiquitinated versions displaying distinct banding patterns from those of CSPα oligomers, and no sensitivity to acid treatment.

Importantly, shRNA knockdown (KD) of the critical Fe-S cluster assembly protein Nfs1 reduced oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ and allowed partial palmitoylation of these mutants; and this effect of Nfs1 KD was reversed by expression of a KD-resistant version of Nfs1 (Fig. 1h).

Taken together, these results from recombinant and eukaryotic cell-derived proteins suggest that deficient Cys-palmitoylation allows oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ via Fe-S cluster binding at their Cys-string region.

CSPα Mutants are Misrecognized by the Cytosolic Fe-S Cluster Assembly Machinery in Neurons

CSPα is heavily expressed in neurons (17, 18), and the most devastating symptoms and pathology of ANCL are neurological (19, 20). We thus expressed CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ or SSPα in primary cortical neurons from CSPα knockout (CSPα−/−) mice. As expected, CSPαWT was nearly fully palmitoylated in neurons, and neither CSPαWT nor SSPα formed large oligomers (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S2a). In contrast, found that CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ accumulated as oligomers with large molecular masses (Fig. 2a). These oligomers could be dissociated by acid treatment – revealing a mass-shift in the monomer, indicative of severe palmitoylation deficit in CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ (Supplementary Fig. S2a).

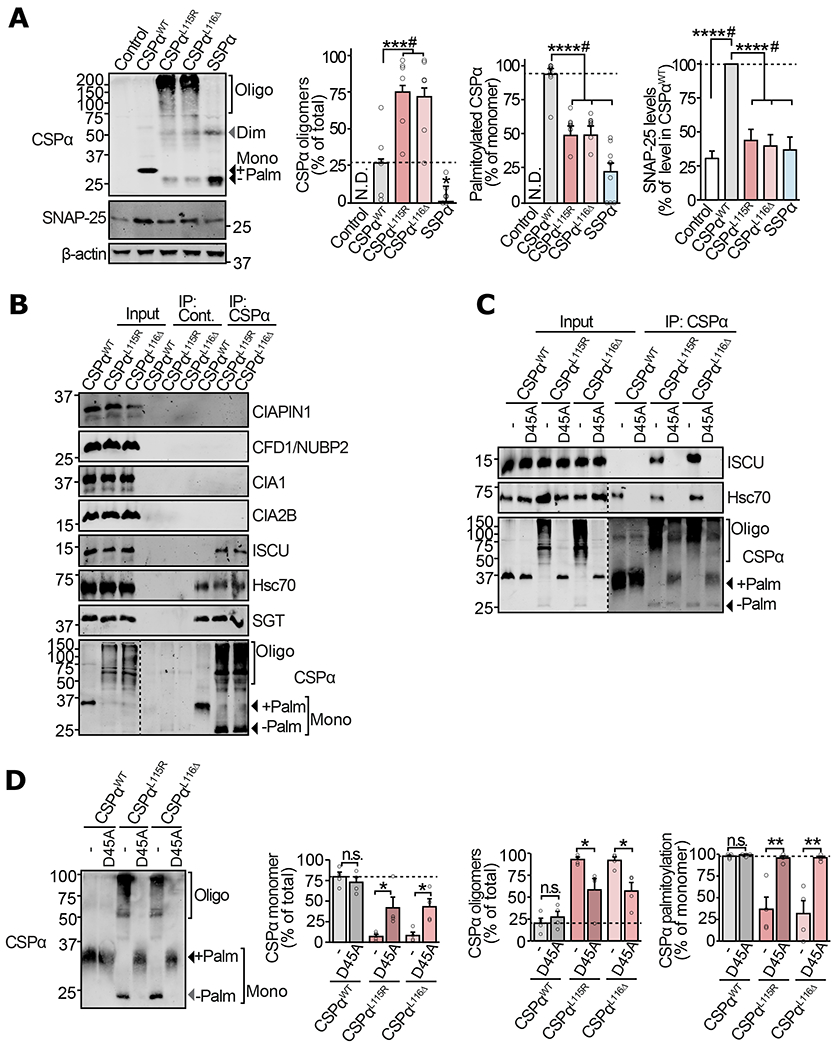

Figure 2 |. Mechanism of Fe-S cluster binding to the ANCL mutants of CSPα in neurons.

(a-d) Primary cortical neurons from neonatal CSPα−/− mice were infected with lentiviruses expressing the indicated myc-tagged version of CSPα on 7 days in vitro (DIV). (a) Neurons expressing CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ, SSPα, or empty virus (control) were lysed on 17 DIV and CSPα oligomerization, palmitoylation, and SNAP-25 levels were measured by quantitative immunoblotting. SNAP-25 was normalized to β-actin and is shown as percent of its expression in CSPαWT expressing neurons. (b) Neurons expressing CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, or CSPαL116Δ were lysed on DIV14 and subjected to anti-myc immunoprecipitation. The eluate was immunoblotted to detect co-immunoprecipitated members of the CIA machinery. Hsc70 and SGT are known interactors of CSPα. (c) Neurons expressing CSPαWT, CSPαWT/D45A, CSPαL115R, CSPαL115R/D45A, CSPαL116Δ, and CSPαL116Δ/D45A were lysed on DIV14, subjected to anti-myc immunoprecipitation and immunoblotted to detect co-immunoprecipitation of Hsc70 or ISCU. (d) Lysates from neurons expressing CSPαWT, CSPαWT/D45A, CSPαL115R, CSPαL115R/D45A, CSPαL116Δ, and CSPαL116Δ/D45A were immunoblotted (left) to measure oligomerization and palmitoylation (right) as % of the total protein detected in each lane. Mono = monomer; Dim = dimer; Oligo = oligomers; Palm = palmitoylated. Data shown are from (a) n=6 for CSPα oligomerization, n=9 for CSPα palmitoylation, and n=13 for SNAP-25 levels (n = independent transductions); (b-c) representatives of n=3 immunoprecipitations; (d) n=4 transductions. In (a) and (d) Data represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; n.s. = not significant by two-tailed Student’s t-test. #P<0.05 by Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U test. Uncropped blots are shown in Source Data Fig 2.

How the two identified ANCL mutations interfere with palmitoylation of CSPα remains unclear. The two mutated Leu residues reside next to the Cys-string, and are conserved from invertebrates to humans, as well as among the three paralogs (CSPα, CSPβ and CSPγ), suggesting their significance to the structure-function of the Cys-string. Yet, they do not conform to any known motif which affects palmitoylation or depalmitoylation. Substitution of one or both Leu residues to Ala, thus maintaining the aliphatic structure and hydrophobicity, allowed normal palmitoylation and did not cause aggregation of CSPα (Supplementary Fig. S2b). However, either adding charge with mutation L115D (albeit, opposite charge compared to the ANCL mutation L115R), or removal of one Leu side chain with mutation L116G (similar to L116Δ but maintaining the backbone-length), strongly reduced palmitoylation and caused formation of oligomers (Supplementary Fig. S2b), suggesting that the two tandem hydrophobic side chains of Leu residues are required for normal palmitoylation of CSPα.

We next addressed how Fe-S clusters are targeted to mutant CSPα, by postulating that mutant CSPα interacts with the cytosolic Fe-S protein assembly (CIA) machinery. We found that both CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ, but not CSPαWT, co-immunoprecipitated with one particular protein – ISCU (Fig. 2b), which functions as a part of the Hsc70/Hsc20/ISCU complex in the CIA machinery (21). This suggests that the Fe-S cluster scaffolding protein ISCU, which normally transfers Fe-S clusters to recipient apo-proteins (22), is mis-loading Fe-S clusters onto mutant CSPα.

In analogy to the native CSPα/Hsc70/SGT chaperone complex, where the J-domain of CSPα binds Hsc70, the interaction of mutant CSPα with the Hsc70/ISCU complex presented the possibility that Hsc70 in this CIA complex recruits the mutant CSPα via its J-domain. To test this, we mutated the HPD motif, necessary for J-domain proteins to interact with Hsc70. We introduced a D45A mutation in CSPαWT, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ, obliterating their interaction with Hsc70 (23) (Fig. 2c). Fe-S cluster-binding by CSPαL115R/D45A and CSPαL116Δ/D45A was diminished, when measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy (from proteins expressed in HEK cells, Supplementary Fig. S2c). Strikingly, in neurons, the loss of Hsc70-binding by CSPαL115R/D45A and CSPαL116Δ/D45A led to reduced oligomerization and recovery of palmitoylation (Fig. 2d).

These results suggest that reduced palmitoylation and membrane-association of mutant CSPα allows it to interact with an Fe-S cluster-transferring complex, where it binds Hsc70 through the classic DnaJ-DnaK binding mechanism and receives the Fe-S clusters from the scaffolding protein ISCU.

Oligomerization of the ANCL Mutant CSPα and the Downstream SNARE Defects are Mitigated by Fe-chelators in Neurons

CSPα is a pre-synaptically localized chaperone, where it binds and stabilizes the synaptic SNARE protein SNAP-25 (2, 3, 24, 25). Since ANCL mutations in CSPα (a) severely reduce palmitoylation, affecting membrane-binding, and (b) lead to Fe-S cluster-dependent oligomerization; these mutations may affect the localization and pre-synaptic function of CSPα.

CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ or SSPα expressed in primary CSPα−/− cortical neurons revealed that the ANCL mutations cause mislocalization of CSPα – while CSPαWT localizes to synapse-like puncta on neurites, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ accumulate mostly within the cell body with minimal localization at neurites (Fig. 3a).

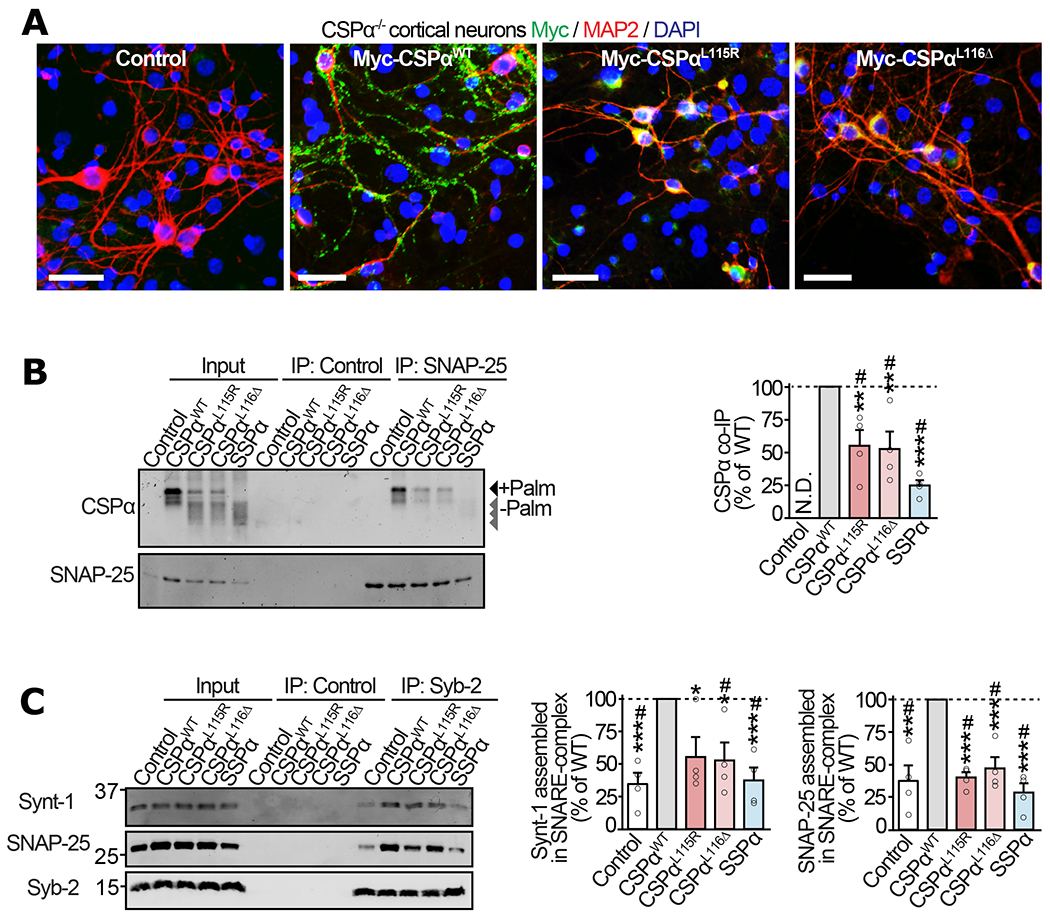

Figure 3 |. Mislocalization of ANCL mutants of CSPα leads to deficiencies in SNAP-25 levels and SNARE-complex assembly in neurons.

Primary cortical neurons from neonatal CSPα−/− mice were infected with lentiviruses expressing myc-tagged CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ, SSPα, or empty lentivirus (Control) on 7 days in vitro (DIV) and examined on 17 DIV. (a) Localization of CSPα variants visualized by immunofluorescence against myc (green), somatodendritic marker MAP2 (red), and nuclear stain DAPI (blue); bar = 50 μm. (b) Interaction of CSPα variants with SNAP-25 was measured via co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay. SNAP-25 IP was followed by quantitative immunoblotting of the co-IP’d CSPα (top blot), and normalized to the IP’d SNAP-25 (bottom blot). Control = sham IP without IgG. N.D. = not detected. (c) Synaptic SNARE-complex assembly was measured by synaptobrevin-2 (Syb-2) IP followed by quantitative immunoblotting of co-IP’d SNARE-complex partners syntaxin-1 (Synt-1) and SNAP-25, each normalized to the IP’d Syb-2. Control = sham IP with plain rabbit serum. Data are from (a) representative of n=3 transductions, (b) n=4 SNAP-25 immunoprecipitations, and (c) n=4 Syb-2 immunoprecipitations. In (b-c) data represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t-test. #P<0.05 by Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U test. Uncropped blots are shown in Source Data Fig 3.

This mislocalization of the ANCL mutants CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ away from synapses prompted us to examine their interaction with the synaptic SNARE protein SNAP-25, the best characterized client of CSPα’s chaperone function (3, 26, 27). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments from CSPα−/− neurons expressing CSPα variants showed that compared to CSPαWT, the interaction of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ with SNAP-25 was severely reduced (Fig. 3b). In CSPα−/− mice, complete loss-of-function is known to result in reduced SNAP-25 protein levels (3, 26, 27). While expression of CSPαWT in CSPα−/− neurons increased SNAP-25 levels as expected, CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ expression led to no significant improvement in SNAP-25 levels, similar to the SSPα mutant (Fig. 2a); suggesting an almost complete loss of CSPα function due to ANCL mutations, likely due to its oligomerization and mislocalization away from the client SNAP-25.

Reduced SNAP-25 levels can affect the assembly of SNARE-complexes (3), which comprise SNAP-25, syntaxin-1 (Synt-1), and VAMP-2/ synaptobrevin-2 (Syb-2), and is the functional core-unit that catalyzes synaptic vesicle release. To quantify SNARE-complex assembly in CSPα−/− neurons expressing the CSPα variants, we immunoprecipitated Syb-2 and measured the co-immunoprecipitated SNAP-25 and syntaxin-1. SNARE-complex assembly in CSPα−/− neurons was more-than-doubled by CSPαWT expression, while CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ and SSPα had no significant effect (Fig. 3c).

Overall, these data suggest that ANCL mutations in CSPα cause: a) reduced palmitoylation of the Cys-string, allowing for b) Fe-S cluster binding at the Cys-string, leading to c) oligomerization and mislocalization of CSPα. This sequestration of mutant CSPα away from the synapses cause a downstream deficit in interaction with its synaptic client SNAP-25, reducing SNAP-25’s proteins levels and its assembly into SNARE-complexes. With this understanding of the molecular-cellular cascade of defects caused by ANCL mutations, we aimed at modifying the Fe-S cluster-dependent oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ.

Pharmacological iron chelation is known to reduce Fe-S cluster assembly in recombinant proteins (28) and in cells (29). Thus, iron-chelators may be useful in mitigating Fe-S cluster binding and oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ. Iron chelators deferiprone (L1) and deferoxamine (Dfx) are already in use for treating iron-overload in humans due to transfusions or inherited disorders (30, 31), and L1 is known to efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier (32–34). Both L1 and Dfx reduced the oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ expressed in CSP−/− neurons in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4a–b). Interestingly, palmitoylation of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ was also improved by the same treatments in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4a–b), suggesting a competition for CSPα’s Cys residues between the physiological modification by acyl chains (palmitoylation) versus oligomerization via Fe-S clusters.

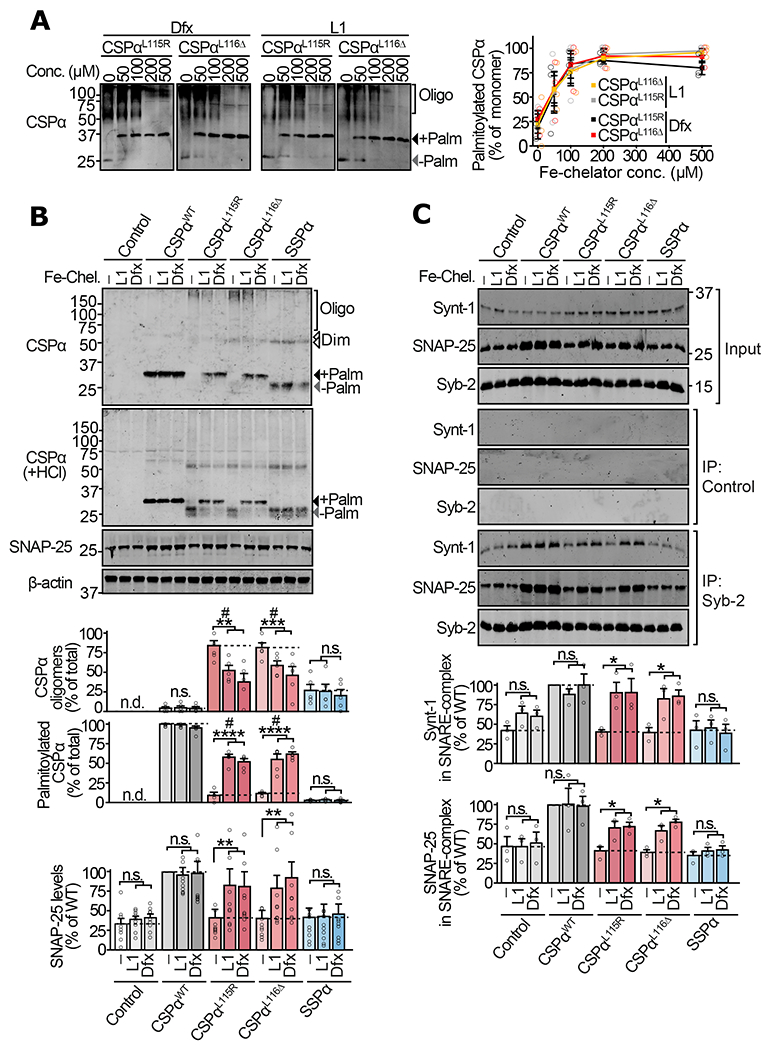

Figure 4 |. Iron-chelation in neurons alleviates oligomerization of mutant CSPα and the downstream SNARE defects.

Primary cortical neurons from neonatal CSPα−/− mice were infected with lentiviruses expressing the indicated versions of CSPα on day 5 in vitro. On day 12 in vitro, these neurons were incubated with vehicle (DMSO), or iron chelators deferiprone (L1) and deferoxamine (Dfx) for 72 hours. (a) Neurons expressing myc-tagged CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ were treated with indicated concentrations of L1 or Dfx, and lysates were immunoblotted for CSPα. +Palm = palmitoylated; −Palm = non-palmitoylated; Oligo = oligomers. (b) Neurons expressing myc-tagged CSPαWT, CSPαL115R, CSPαL116Δ, SSPα, or empty virus (Control) were treated with DMSO vehicle (−), L1 (200 μM), or Dfx (200 μM). Oligomerization was measured by SDS-PAGE separation and quantitative immunoblotting against CSPα. Palm = palmitoylated; Dim = dimer; Oligo = oligomers of higher mass than dimer. To measure palmitoylation, oligomers were disrupted by lysing neurons in 0.1 N HCl plus 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at 4 °C, followed by SDS-PAGE and quantitative immunoblotting against CSPα. SNAP-25 levels were measured from total lysate by quantitative immunoblotting against SNAP-25, normalized to β-actin. (c) Synaptic SNARE-complex assembly was measured by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment. Syb-2 IP was followed by quantitative immunoblotting of co-IP’d SNAP-25 and Synt-1, each normalized to the IP’d Syb-2. Control = sham IP with plain rabbit serum. Data are from (a) n=3 transductions, (b) n=5 for CSPα oligomerization and palmitoylation, and n=10 for SNAP-25 levels (n = transduction plus treatment), and (c) n=3 Syb-2 immunoprecipitations. Data represent means ± SEM. For (a) P<0.05 for both CSPα variants at >100 μM compared 0 μM. For (b-c) *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t-test. #P<0.05 by Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U test. n.s. = not significant; n.d. = not detected. Uncropped blots are shown in Source Data Fig 4.

Reduced oligomerization and improved palmitoylation of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ by L1 and Dfx were accompanied by augmentation of SNAP-25 levels by approximately two-fold in neurons expressing CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ (Fig. 4b), bringing SNAP-25 levels closer to those in CSPαWT expressing neurons. Neither L1 nor Dfx affected SNAP-25 levels in neurons expressing CSPαWT or SSPα (Fig. 4b), indicating that L1 and Dfx affect SNAP-25 only indirectly, via salvaging the synaptic-chaperone activity of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ. SNARE co-immunoprecipitation experiments show that L1 and Dfx treatment led to amelioration of SNARE-complex assembly defects in CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ expressing neurons, and had no effect in neurons expressing either CSPαWT or SSPα (Fig. 4c).

Taken together, these studies show that L1 and Dfx not only improve palmitoylation and reduce oligomerization of CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ in neurons, but this also leads to functional rescue – evident from the increase in SNAP-25 levels and its improved assembly into synaptic SNARE-complexes.

CSPα mutations are autosomal dominant in ANCL patients, while a loss of a single allele has no detectable phenotype in CSPα hemizygous mice (35). Thus, a dominant-negative pathogenic mechanism has been proposed for ANCL, based on the observation that oligomers of mutant CSPα protein incorporates WT CSPα protein as well (10); possibly initiated via the well-documented physiological dimerization of CSPα (36, 37). In concurrence with these findings, when we co-expressed myc-CSPαWT with GFP-CSPαWT, GFP-CSPαL115R, or GFP-CSPαL116Δ, only the ANCL mutants GFP-CSPαL115R and GFP-CSPαL116Δ (but not GFP-CSPαWT) induced oligomerization of myc-CSPαWT (Supplementary Fig. S3). This dominant-negative effect of the ANCL-mutant CSPα on WT CSPα is apparent in the following studies, which we performed in ANCL patient-derived fibroblasts and induced neurons (iNs), which co-express the CSPαWT and CSPαL116Δ alleles.

CSPα Oligomerization as well as the Downstream Cellular Defects are Mitigated by Fe-chelators in ANCL Patient-derived Induced Neurons

Next, we used fibroblasts from an ANCL patient who carried the CSPαL116Δ allele (7). CSPα as well as it’s well-characterized interactors Hsc70 and SGT were expressed in fibroblasts, derived either from an ANCL patient (ANCL) or from an unaffected sex- and age-matched individual (WT) (Supplementary Fig. S4b). When CSPα was immunoprecipitated from ANCL or WT fibroblasts, UV-Vis spectroscopy showed absorbance peaks characteristic of Fe-S clusters only in ANCL fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. S4a).

Whereas the CSPα/Hsc70/SGT chaperone complex is expressed in fibroblasts, the neuronal client of this complex – SNAP-25 – was not observed in fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. S4b). This prompted us to convert the patient fibroblasts into iNs, by lentiviral co-expression of the four transcription factors Brn2, Ascl1, Myt1l, and NeuroD1 (38) (Supplementary Fig. S4b). In the ANCL iNs, CSPα palmitoylation was reduced, accompanied by its oligomerization, compared to WT iNs (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Accordingly, levels of its neuronal client SNAP-25 were markedly reduced in ANCL iNs (Supplementary Fig. S4c), which is likely a result of the severely reduced interaction of CSPα with SNAP-25 in the ANCL iNs (Supplementary Fig. S4d). CSPα chaperones the natively unfolded monomeric SNAP-25, and prevents its rapid degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (3). We thus measured SNAP-25 turnover in iNs using the cycloheximide chase method, and found that SNAP-25 degradation was accelerated in ANCL iNs (T1/2 ~ 12.5h) compared to WT iNs (T1/2 > 24h) (Supplementary Fig. S4e), confirming a defect in the SNAP-25 chaperoning function of CSPα.

While SNAP-25 is only one of the proposed CSPα clients expressed in neurons (39), the pathological hallmark of ANCL is accumulation of the autofluorescent pigment lipofuscin in neuronal lysosomes (20, 40). Unlike primary neurons, we could maintain iNs for months, which led to progressive accumulation of lipofuscin in ANCL iNs, as observable by autofluorescence at 56 days post iN conversion (Supplementary Fig. S4f). Lipofuscin was quantifiably elevated specifically in the ANCL iNs, when measured by immunoblotting against the mitochondrial ATP-synthase subunit C (ATP5G), a major lysosomal storage-component in ANCL (41), and by lipofuscin ELISA (Supplementary Fig. S4g–h).

With the above observations affording us a patient-derived model of the molecular-cellular pathobiology of ANCL, we next tested the effect(s) of iron-chelators on the ANCL iNs.

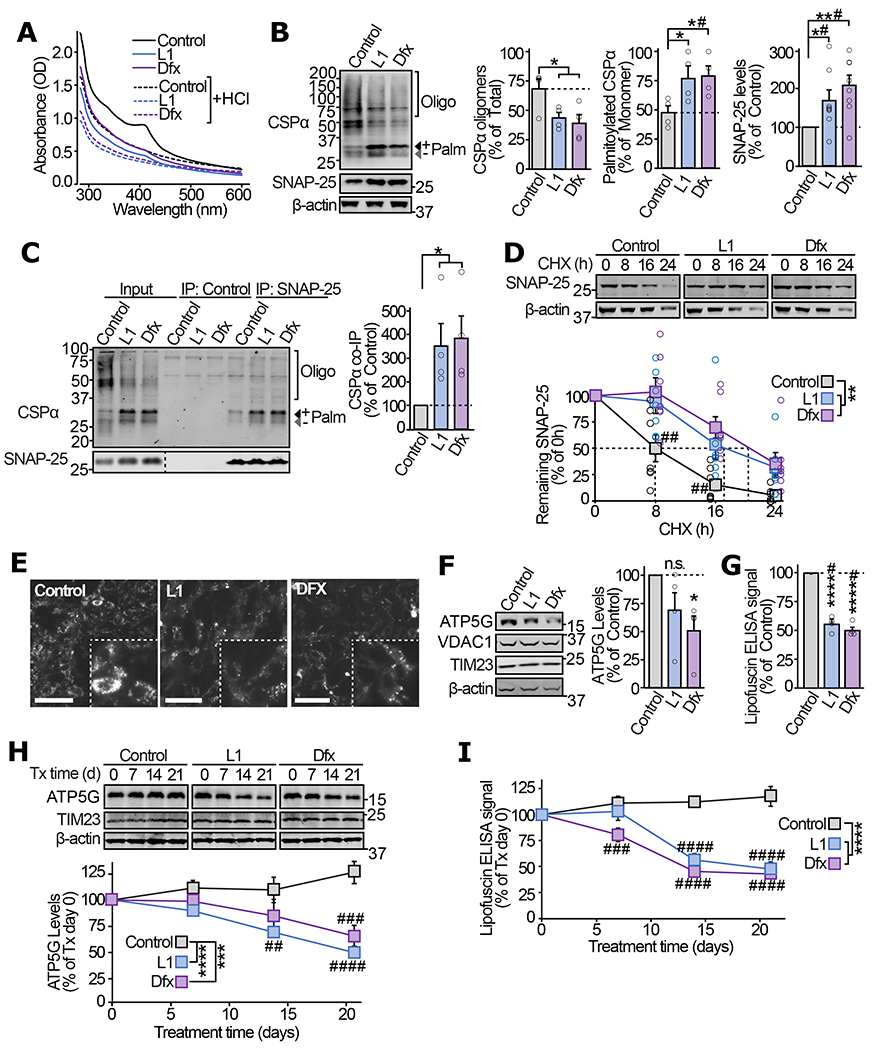

Both L1 and Dfx reduced the UV-Vis signature of Fe-S clusters bound to immunoprecipitated CSPα from ANCL fibroblasts (Fig. 5a). L1 and Dfx also improved palmitoylation and reduced the oligomerization of CSPα in ANCL iNs (Fig. 5b). These effects of L1 and Dfx were accompanied by improved interaction of CSPα with SNAP-25 in ANCL iNs (Fig. 5c; note that mainly CSPα monomers but not oligomers bind to SNAP-25.). As a consequence, SNAP-25 levels in ANCL iNs were augmented by both L1 and Dfx (Fig. 5b). Cycloheximide chase studies show that rapid turnover of SNAP-25 in ANCL iNs was ameliorated by both L1 and Dfx, with ~2x increase in SNAP-25 half-life (Fig. 5d); suggesting that the SNAP-25 chaperoning function of CSPα is restored by these iron-chelators in ANCL patient-derived iNs.

Figure 5 |. In ANCL patient-derived iNs iron-chelators alleviate CSPα oligomerization, the SNAP-25 chaperoning defect, and lipofuscin accumulation.

(a) ANCL patient-derived fibroblasts were treated with 200μM of L1 or Dfx, or 0.1% DMSO (Control) for 72 h. UV-Vis absorbance spectra of immunoprecipitated CSPα were measured before and after HCl treatment. (b-d) In ANCL iNs treated with L1, Dfx, or vehicle for 72 h following the iN conversion: (b) levels of oligomerized and fully palmitoylated CSPα as well as total SNAP-25 were measured by quantitative immunoblotting. Oligo = oligomers; Palm = palmitoylated. (c) The interaction of CSPα with SNAP-25 was measured by immunoprecipitating SNAP-25 followed by quantitative immunoblotting of co-immunoprecipitated CSPα (normalized to SNAP-25 IP). Control = IP without IgG. (d) Turnover of SNAP-25 was determined by cycloheximide chase, while maintaining the iron-chelators or vehicle in the medium. (e-g) ANCL iNs treated with L1, Dfx, or vehicle for 56 d were analyzed for (e) lipofuscin autofluorescence (Ex 465-495, Em 515-555 nm; scale bar = 50 μm), (f) ATP5G levels by quantitative immunoblotting (VDAC1 and TIM23 indicate overall mitochondrial protein expression), and (g) lipofuscin accumulation by ELISA. (h-i) 56 day old untreated ANCL iNs were treated with L1, Dfx, or vehicle, and analyzed for (h) ATP5G levels by quantitative immunoblotting and (i) lipofuscin by ELISA, at indicated days of treatment. Data are from (a) representative of n=4, (b) n=4 for CSPα oligomerization and palmitoylation, and n=8 for SNAP-25 levels, (c) n=4, (d) n=7, (e) representative of n=3, (f) n=4, (g) n=4, (h) n=6, (i) n=3. In (a, c) n = immunoprecipitation; in (b, d-i) n = iN conversions. Data in (b-d, f-i) represent means ± SEM. In (b-c, f-g) *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ****P<0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t-test. #P<0.05 by Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U test. In (d, h-i) **P < 0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001 by two-way ANOVA; ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001; ####P<0.0001 by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Uncropped blots are shown in Source Data Fig 5.

In addition, lipofuscin autofluorescence was reduced in ANCL iNs after L1 and Dfx treatment (Fig. 5e), which corresponded with a trend toward reduced accumulation of ATP5G (Fig. 5f), and a significant reduction in lipofuscin ELISA signal (Fig. 5g). In the above experiments, L1 and Dfx were introduced immediately after fibroblast-to-neuron conversion, suggesting efficacy of the iron-chelators in preventing lipofuscin accumulation. As a treatment paradigm, we also added iron-chelators post-accumulation of lipofuscin. When L1 and Dfx were added to ANCL iNs after 56 days of lipofuscin accumulation, the ATP5G and lipofuscin levels diminished over the subsequent 3 weeks, down to similar levels as observed in the prevention experiments (Fig. 5h–i).

DISCUSSION

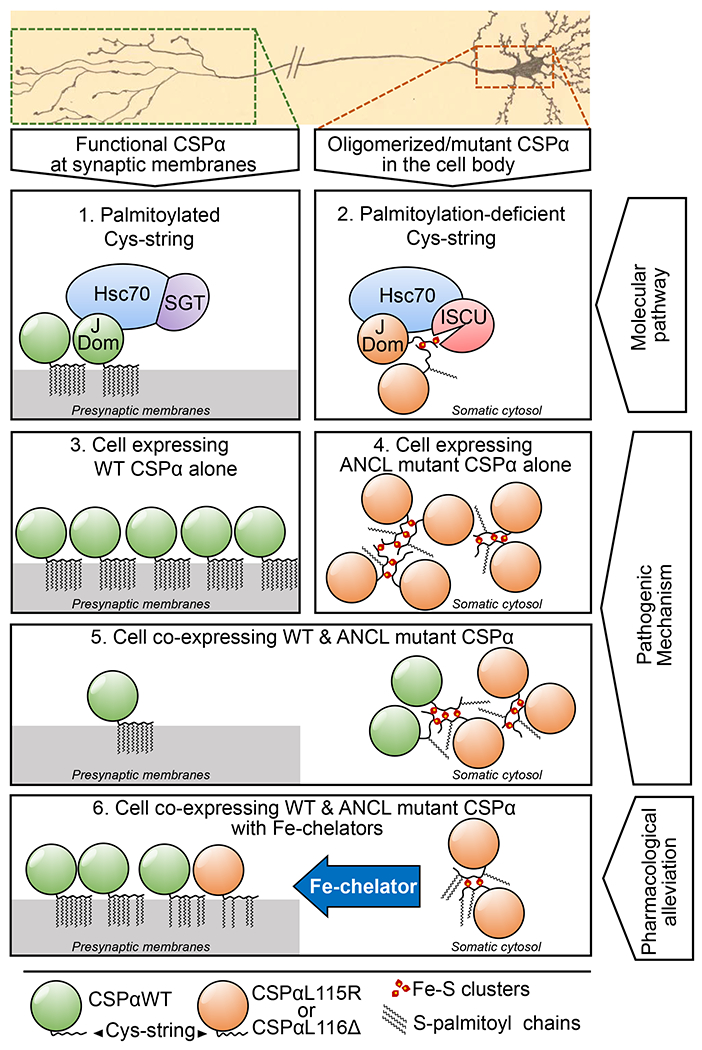

Our results reveal a surprising mechanism for the oligomerization of CSPα carrying ANCL mutations, which had previously been observed (10, 11), but had remained mechanistically unexplained. We find that this oligomerization is dependent on mis-loading of Fe-S clusters onto the Cys-string of mutant CSPα with diminished palmitoylation. Whereas Fe-S clusters are known to crosslink proteins into physiological/functional oligomers (14, 15), ectopic binding of Fe-S clusters has never been reported to generate pathogenic oligomers/aggregates. Importantly, the Fe-S cluster binding and oligomerization of mutant CSPα can be mitigated by iron-chelators (Summarized in Fig. 6), partially restoring the presynaptic chaperone function of CSPα.

Figure 6 |. Model depicting the mechanism of CSPα oligomerization in ANCL and its alleviation by Fe-chelators.

CSPαWT is heavily palmitoylated, allowing its localization to presynaptic membranes (panel 1), where it forms a functional chaperone complex with Hsc70 and SGT; which chaperones synaptic SNARE SNAP-25. The ANCL mutants CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ are inefficiently palmitoylated, and mislocalized away from synapses, where mutant CSPα’s J-domain (J Dom) recruits a CIA complex containing Hsc70, and ISCU – an Fe-S cluster transferring protein (panel 2). This molecular interaction leads to pathogenic oligomers of mutant CSPα: CSPαWT expressed alone is not oligomerized beyond its native homodimerization (panel 3), while the loss of palmitoylation in the ANCL mutants CSPαL115R and CSPαL116Δ accompanies ectopic binding of their reactive Cys-strings to Fe-S clusters, cross-linking the mutant CSPα molecules into oligomers. These oligomers mainly reside away from the synapse, causing loss of CSPα’s chaperone function at the synapse (panel 4). In the CSPαL115R or CSPαL116Δ heterozygous cells, mutant CSPα is able to recruit CSPαWT into oligomers, leading to less than hemizygous level of CSPα function at the synapse (panel 5). Iron-chelator treatment leads to reduction in the Fe-S cluster-bound oligomers, allowing improved CSPα function at the synapse (panel 6). This increase in functional CSPα leads to partial alleviation of the downstream SNAP-25 instability and lipofuscin accumulation phenotypes.

Mechanistically, we found that interaction of mutant CSPα with the CIA machinery, in particular with the ISCU/Hsc70 complex, is necessary for mis-loading of Fe-S clusters onto the Cys-string. Fe-S mis-loading is likely to be a secondary outcome of the palmitoylation defect of mutant CSPα, and targeting of its Cys-string region by the CIA machinery seems to be a case of mistaken substrate identity; since, the mutant CSPα participates in the Hsc70/ISCU complex via its J domain, and at the same time provides a high local-concentration of a “substrate-like” peptide with its ineffectually palmitoylated Cys-string. This molecular case of misrecognition may be further enhanced by similarities in the normally S-palmitoylated sites of CSPα and the motifs recognized by the CIA machinery (e.g. CX2C or CX13CX2CX5C motifs where “X” is any residue (42)).

While our data support the loss of mutant CSPα localization and function at the synapse, whether the loss of SNAP-25 chaperoning causes lipofuscin storage remains unknown. CSPα has multiple proposed clients (39), and loss of chaperoning of any one or more of the clients may affect lysosomal biogenesis, trafficking, or function, and may otherwise alter the levels of lysosomally stored metabolites. Further functional studies of the CSPα interactome may reveal the downstream client(s) relevant to the lysosomal phenotype of ANCL.

Our findings point to pharmacological iron chelation as a potential mechanism-based treatment for ANCL – which is currently intractable to treatment. One of the iron chelators used here, L1, efficiently crosses the blood-brain barrier (32–34) and is orally available. Side effects of long term L1 use are considered acceptable in chronic iron-overload disorders (43), and these side effects become more acceptable in the context of ANCL, where progressive neurodegeneration begins at 30-40 years of age, with expected survival of 8-12 years (8). This new use for iron-chelating drugs – which are already approved by regulatory agencies and in use for decades – can accelerate their use for ANCL treatment by bypassing the early stages of development and safety testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thomas C. Südhof for kindly sharing the CSPα knockout mouse line and antibodies against CSPα and neuronal SNARE proteins, and Dr. Gregory Petsko for his advice on experimental approaches and the manuscript. Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) experiments were supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR-1332208. This work was supported by grants from Alzheimer’s Associaton (NIRG-15-363678 to MS), American Federation for Aging Research (New Investigator in Alzheimer’s Research Grant to MS), NIH’s National Institute for Aging (1R01AG052505 to MS) and National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS095988 to MS) and (1R01NS102181 to JB), as well as F31 studentship (NS098623 to NN).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors have no competing interests as defined by Nature Research, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD, The cysteine-string domain of the secretory vesicle cysteine-string protein is required for membrane targeting. Biochem J 335 ( Pt 2), 205–209 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobaben S et al. , A trimeric protein complex functions as a synaptic chaperone machine. Neuron 31, 987–999 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma M, Burré J, Südhof TC, CSPα promotes SNARE-complex assembly by chaperoning SNAP-25 during synaptic activity. Nat Cell Biol 13, 30–39 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Südhof TC, Rothman JE, Membrane Fusion: Grappling with SNARE and SM Proteins. Science 323, 474–477 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benitez BA et al. , Exome-sequencing confirms DNAJC5 mutations as cause of adult neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. PLoS One 6, e26741 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosková L et al. , Mutations in DNAJC5, encoding cysteine-string protein alpha, cause autosomal-dominant adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Am J Hum Genet 89, 241–252 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velinov M et al. , Mutations in the gene DNAJC5 cause autosomal dominant Kufs disease in a proportion of cases: study of the Parry family and 8 other families. PLoS One 7, e29729 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephson SA, Schmidt RE, Millsap P, McManus DQ, Morris JC, Autosomal dominant Kufs’ disease: a cause of early onset dementia. Journal of the neurological sciences 188, 51–60 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson MX et al. , Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis with DNAJC5/CSPalpha mutation has PPT1 pathology and exhibit aberrant protein palmitoylation. Acta neuropathologica, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y-Q, Chandra SS, Oligomerization of Cysteine String Protein alpha mutants causing adult neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842, 2136–2146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greaves J et al. , Palmitoylation-induced aggregation of cysteine-string protein mutants that cause neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Biol Chem 287, 37330–37339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diez-Ardanuy C, Greaves J, Munro KR, Tomkinson NC, Chamberlain LH, A cluster of palmitoylated cysteines are essential for aggregation of cysteine-string protein mutants that cause neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. 7, 10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dailey HA, Finnegan MG, Johnson MK, Human ferrochelatase is an iron-sulfur protein. Biochemistry 33, 403–407 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson C, Kavanagh KL, Gileadi O, Oppermann U, Reversible sequestration of active site cysteines in a 2Fe-2S-bridged dimer provides a mechanism for glutaredoxin 2 regulation in human mitochondria. J Biol Chem 282, 3077–3082 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesecke N, Mittler S, Eckers E, Herrmann JM, Deponte M, Two novel monothiol glutaredoxins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae provide further insight into iron-sulfur cluster binding, oligomerization, and enzymatic activity of glutaredoxins. Biochemistry 47, 1452–1463 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gundersen CB, Mastrogiacomo A, Faull K, Umbach JA, Extensive lipidation of a Torpedo cysteine string protein. J Biol Chem 269, 19197–19199 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinsmaier KE et al. , A cysteine-string protein is expressed in retina and brain of Drosophila. J Neurogenet 7, 15–29 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohan SA et al. , Cysteine string protein immunoreactivity in the nervous system and adrenal gland of rat. J Neurosci 15, 6230–6238 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin JJ, Adult type of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Dev Neurosci 13, 331–338 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goebel HH, Braak H, Adult neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Clin Neuropathol 8, 109–119 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maio N, Rouault TA, Mammalian Fe-S proteins: definition of a consensus motif recognized by the co-chaperone HSC20. Metallomics : integrated biometal science 8, 1032–1046 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouault TA, Biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters in mammalian cells: new insights and relevance to human disease. Disease models & mechanisms 5, 155–164 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD, The molecular chaperone function of the secretory vesicle cysteine string proteins. J Biol Chem 272, 31420–31426 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zinsmaier KE, Eberle KK, Buchner E, Walter N, Benzer S, Paralysis and early death in cysteine string protein mutants of Drosophila. Science 263, 977–980 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umbach JA et al. , Presynaptic dysfunction in Drosophila csp mutants. Neuron 13, 899–907 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernández-Chacón R, Schlüter OM, Südhof TC, Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123, 383–396 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma M et al. , CSPα knockout causes neurodegeneration by impairing SNAP-25 function. EMBO J 31, 829–841 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malkin R, Rabinowitz JC, The reactivity of clostridial ferredoxin with iron chelating agents and 5,5’-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid. Biochemistry 6, 3880–3891 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong W-H, Rouault TA, Functions of mitochondrial ISCU and cytosolic ISCU in mammalian iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis and iron homeostasis. Cell Metab 3, 199–210 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldus WP, Fairbanks VF, Dickson ER, Baggenstoss AH, Deferoxamine-chelatable iron in hemochromatosis and other disorders of iron overload. Mayo Clinic proceedings 53, 157–165 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffbrand AV, Cohen A, Hershko C, Role of deferiprone in chelation therapy for transfusional iron overload. Blood 102, 17–24 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbruzzese G et al. , A pilot trial of deferiprone for neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Haematologica 96, 1708–1711 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habgood MD et al. , Investigation into the correlation between the structure of hydroxypyridinones and blood-brain barrier permeability. Biochemical pharmacology 57, 1305–1310 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fredenburg AM, Sethi RK, Allen DD, Yokel RA, The pharmacokinetics and blood-brain barrier permeation of the chelators 1,2 dimethly-, 1,2 diethyl-, and 1-[ethan-1’ol]-2-methyl-3-hydroxypyridin-4-one in the rat. Toxicology 108, 191–199 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Chacón R et al. , The synaptic vesicle protein CSP alpha prevents presynaptic degeneration. Neuron 42, 237–251 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun JE, Scheller RH, Cysteine string protein, a DnaJ family member, is present on diverse secretory vesicles. Neuropharmacology 34, 1361–1369 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD, Activation of the ATPase activity of heat-shock proteins Hsc70/Hsp70 by cysteine-string protein. Biochem J 322 ( Pt 3), 853–858 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang ZP et al. , Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature 476, 220–223 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y-Q et al. , Identification of CSPα clients reveals a role in dynamin 1 regulation. Neuron 74, 136–150 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson GW, Goebel HH, Simonati A, Human pathology in NCL. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832, 1807–1826 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall NA, Lake BD, Dewji NN, Patrick AD, Lysosomal storage of subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase in Batten’s disease (ceroid-lipofuscinosis). Biochem J 275 ( Pt 1), 269–272 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Netz DJ, Mascarenhas J, Stehling O, Pierik AJ, Lill R, Maturation of cytosolic and nuclear iron-sulfur proteins. Trends in cell biology 24, 303–312 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piga A et al. , Deferiprone. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1202, 75–78 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.