Abstract

Background

The prevalence of bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA) is high and antimicrobial resistance is likely to increase mortality from these infections. Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae are of particular concern, given the widespread reliance on ceftriaxone for management of sepsis in Africa.

Objectives

Reviewing studies from sSA, we aimed to describe the prevalence of 3GC resistance in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Salmonella BSIs and the in-hospital mortality from 3GC-R BSIs.

Methods

We systematically reviewed studies reporting 3GC susceptibility testing of E. coli, Klebsiella and Salmonella BSI. We searched PubMed and Scopus from January 1990 to September 2019 for primary data reporting 3GC susceptibility testing of Enterobacteriaceae associated with BSI in sSA and studies reporting mortality from 3GC-R BSI. 3GC-R was defined as phenotypic resistance to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime or ceftazidime. Outcomes were reported as median prevalence of 3GC resistance for each pathogen.

Results

We identified 40 articles, including 7 reporting mortality. Median prevalence of 3GC resistance in E. coli was 18.4% (IQR 10.5 to 35.2) from 20 studies and in Klebsiella spp. was 54.4% (IQR 24.3 to 81.2) from 28 studies. Amongst non-typhoidal salmonellae, 3GC resistance was 1.9% (IQR 0 to 6.1) from 12 studies. A pooled mortality estimate was prohibited by heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Levels of 3GC resistance amongst bloodstream Enterobacteriaceae in sSA are high, yet the mortality burden is unknown. The lack of clinical outcome data from drug-resistant infections in Africa represents a major knowledge gap and future work must link laboratory surveillance to clinical data.

Introduction

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacteria is recognized as a global public health problem.1 Drug-resistant infections (DRIs) caused by AMR bacteria threaten human health worldwide, with the greatest mortality burden expected to occur in low- and middle-income countries.2 In settings where antibiotics and advanced diagnostics are available and affordable, DRIs can be treated with tailored regimens using second- or third-line antibiotics; however, these agents cost more and increase healthcare expenditure.3 In sub-Saharan Africa (sSA), where bacterial bloodstream infection (BSI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality,4 diagnostic facilities are scarce and antibiotics such as carbapenems and semi-synthetic aminoglycosides (e.g. amikacin) are either unavailable or prohibitively expensive, the morbidity and mortality from DRIs is predicted to be high.2,5

In many sSA hospitals, limited nursing capacity favours the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials with a once-daily dosing regimen and this has led to the widespread adoption of the third-generation cephalosporin (3GC) ceftriaxone for the empirical management of hospitalized patients with suspected sepsis.6 ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, which are resistant to penicillins and 3GCs, represent a threat to the treatment of BSI in this setting and have been identified as priority pathogens on which all national AMR programmes should focus their surveillance and reporting.2,7

Comprehensive AMR surveillance in sSA is limited by lack of quality-assured diagnostic microbiology laboratories, but knowledge of the prevalence and spatiotemporal trends of 3GC-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae is critical to inform national and international antibiotic prescribing guidelines. Additionally, securing access to effective second- and third-line antibiotics in Africa will not only require an understanding of the prevalence of 3GC resistance, but also of the burden and impact of these pathogens on patients and healthcare systems.8 We have therefore systematically reviewed published reports of 3GC susceptibility amongst key Enterobacteriaceae in sSA, including surveillance data and clinical cohorts. Robust clinical outcome data are needed to support the estimates and assumptions that the greatest global burden associated with AMR will occur in sSA5 and we have therefore also reviewed studies that describe mortality from 3GC-R BSI. The aim of this systematic review was to determine the prevalence of 3GC resistance amongst Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp. and Salmonella BSI in sSA and to provide an estimate of the associated mortality burden from these infections.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We systematically reviewed articles published between 1 January 1990 and 31 August 2019, according to a pre-specified protocol, prepared in February 2017 (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online) with no language restrictions, following PRISMA guidelines (Table S2). We searched PubMed and Scopus according to a predefined strategy with search terms relating to BSI and susceptibility testing (Table S3). A search string that included all sSA countries as defined by the UN list of 54 African sovereign states returned more articles than a string using ‘Africa’ alone. References cited in selected articles were reviewed for additional articles and authors were contacted to obtain original data, where percentages but not absolute numbers of resistant organisms were provided.

Studies were included if they tested E. coli, Klebsiella spp. or Salmonella spp. for 3GC resistance. Methods of confirmatory ESBL testing, such as double-disc synergy or PCR, were extracted from articles if they were reported, but we did not exclude studies that did not confirm ESBL status. We included surveillance data in addition to studies reporting clinical cohorts, but excluded case reports, case series, expert opinions and reviews.

Data extraction

Two authors (R.L. and P.M.) independently searched the literature and screened the abstracts of all retrieved records. The full text of remaining English articles was reviewed by one author (R.L.) and of French language articles by another (N.V.G.). Articles in other languages were not found in the search. Disputes about article inclusion were resolved through discussion, with recourse to a third reviewer (N.A.F.) if required. Predefined variables were extracted from each article (Table 1). Variables included study design and setting, clinical data such as age and HIV prevalence of clinical cohorts, and information on laboratory methods including antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) method and guideline, and method of ESBL confirmation. Mortality data were extracted as they were reported in the articles, as case-fatality rates, ORs or relative risks (RRs).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author | Country, year of publication | Years of data collection | Study type | Healthcare setting | Age category | HIV, n (%) | Blood culture method, organism identification | AST method, AST breakpoint guideline | ESBL confirmatory test | External lab QC | Blood culture positivity in study population, n (%) | Prevalence of 3GC resistance, n (%) | Other findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquah41 | Ghana | 2011–12 | Retrospective analysis of positive blood cultures | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 86/331 (26.0) | Klebsiella spp. 1/12 (8.3) | |

| 2013 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Apondi42 | Kenya | 2002–13 | Retrospective analysis of Klebsiella isolates | Urban referral hospital | All ages | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | NR | Klebsiella spp. 68/78 (87.2) | |

| 2016 | NR | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Bejon43 | Kenya | 1994–2001 | Retrospective analysis of Gram-negative bacilli | Rural district hospital | Paediatric | NR | Manual (<1998) then automated | Etest | NR | NR | NR | E. coli 0/141 | |

| 2005 | Klebsiella spp. 4/63 (6.0) | ||||||||||||

| NR | |||||||||||||

| NTS 0/296 | |||||||||||||

| Blomberg17 | Tanzania 2007 | 2001–02 | Prospective cohort of children with suspected systemic infection | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric (0–7 years) | (16.8) | Automated Manual | Disc diffusion and Etest | Etest, PCR | NR | 255/1828 (13.9) | E. coli 9/37 (24.3) Klebsiella spp. 9/52 (17.0) NTS 1/39 (2.6) | Significantly higher 3GC resistance in HAI E. coli than CAI |

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Breurec44 | Senegal | 2007–08 | Prospective cohort of neonates with suspected systemic infection | Urban referral hospitals (three sites) | Paediatric (neonates) | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | Double-disc synergy | NR | 77/226 (34.0) | Klebsiella spp. 33/39 (84.6) | Distinguish EOS from LOS but difference in 3GC resistance NR |

| 2016 | Manual | FSM | |||||||||||

| Brink45 | South Africa | 2006 | Prospective review of bacterial isolates | Private urban hospitals (12 sites) | All ages | NR | NR | Mixture of disc diffusion and automated (VITEK 2) | Mixture of VITEK 2 and double-disc synergy | Yes | NR | E. coli 47/471 (10.0) | |

| 2007 | Klebsiella spp. 293/636 (46.0) | ||||||||||||

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Buys21 | South Africa | 2006–11 | Retrospective review of K. pneumoniae isolates | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric | 82/410 (20.0) | Automated | Mixture of VITEK 2, disc diffusion and Etest CLSI | Mixture of VITEK and double-disc synergy | NR | NR | Klebsiella spp. 339/410 (83.0) | Higher 3GC resistance in HAI than HCAI or CAI |

| 2016 | Automated (VITEK 2) | ||||||||||||

| Reports trends but no definite pattern over time | |||||||||||||

| Crichton46 | South Africa | 2012–15 | Cross-sectional review of BSI | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric | 18/141 (12.8) | Automated | Mixture VITEK/disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 938/7427 (12.6) | E. coli 8/36 (22) | Possibly higher 3GC resistance in CAI but no statistical analysis |

| 2018 | Automated (VITEK 2) | ||||||||||||

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Dramowski47 | South Africa | 2009–13 | Retrospective cohort of HA neonatal BSI | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric (neonates) | NR | Automated | VITEK 2 | NR | Yes | 717/6251 (11.5) | E. coli 7/58 (12.1) | All HAI |

| Automated (VITEK 2) | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 172/235 (73.2) | |||||||||||||

| 2015a | |||||||||||||

| Dramowski10 | South Africa | 2008–13 | Retrospective review of paediatric BSI | Urban referral | Paediatric (excluding neonates) | (13.4) | Automated | VITEK 2 | NR | Yes | 935/17 001 (5.5) | E. coli 12/97 (12.4) | No significant difference in 3GC resistance between HAI and CAI; no increase in 3GC resistance over study period |

| Automated (VITEK 2) | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| 2015b | Klebsiella spp. 122/158 (77.2) | ||||||||||||

| Eibach20 | Ghana | 2007–09 | Prospective cohort of patients with fever/history of fever or suspected neonatal sepsis | Rural district hospital | All | NR | Automated | VITEK 2 | Double-disc synergy and PCR | Yes | NR | E. coli 5/50 (10) | Possible lower 3GC resistance in CAI, but no statistical analysis |

| 2016 | 2010–12 | Mixed (API with MALDI-TOF confirmation) | EUCAST | Klebsiella spp. 34/41 (82.9) | |||||||||

| NTS 0/215 | |||||||||||||

| Jaspan48 | South Africa 2008 | 2002–06 | Retrospective cohort of HIV-infected children | Urban referral | Paediatric (3 months–9 years) | (100) | NR Manual | Disc diffusion ± Etest | NR | NR | NR | Klebsiella spp. 11/11 (100) | All Klebsiella were HAI |

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Kalonji13 | DRC | 2011–14 | Multisite prospective surveillance of Salmonella BSI | Mixed urban referral and private | Paediatric (excluding neonates) | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | Double disc synergy and PCR | Yes | 2353/14 110 (16.7) | NTS 49/776 (6.3) | |

| 2015 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| S. Typhi 0/164 | |||||||||||||

| Kariuki49 | Kenya 2006 | 2002–05 | Prospective cohort of children with NTS in blood/CSF or stool | Urban referral and private hospital | Paediatric (4 weeks to 84 months) | NR | Manual Manual | Disc diffusion and Etest | Double-disc synergy | Yes | NA | NTS 0/198 | |

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Kariuki49,50 | Kenya | 1994–2005 | Cross-sectional review of NTS isolates over 12 years | Rural district hospital | Children (0–13 years) | NR | NR | Disc diffusion | Double-disc synergy | Yes | NA | NTS 0/336 | Trends reported, no change over time |

| 2006 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Ko16 | South Africa | 1996–97 | Prospective cohort of patients with CA K. pneumoniae | Urban multisite | Adults >16 years | 7/40 (18) | NR | NR | Broth dilution or double-disc synergy | NR | NA | K. pneumoniae 3/40 (7.5) | CAI only |

| Automated (VITEK 2) | NR | ||||||||||||

| 2002 | |||||||||||||

| Kohli51 | Kenya | 2003–08 | Retrospective analysis of positive blood cultures | Urban referral | All | 123/1092 (11.3) | Automated | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 1092/18 750 (5.8) | E. coli 10/69 (14.5) | |

| 2010 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 5/38 (13.1) | |||||||||||||

| NTS 0/143 | |||||||||||||

| Labi52 | Ghana | 2010–13 | Retrospective review of Salmonella blood culture isolates | Urban referral | All | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 2768/23 708 (11.7) | NTS 12/198 (6.1) | |

| 2014 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Lochan53 | South Africa 2017 | 2011–13 | Retrospective cohort of children with culture-confirmed BSI | Urban referral | Paediatric | 17/524 (13.4) | Automated Automated (VITEK 2) | VITEK 2, disc diffusion and Etest CLSI | VITEK 2 or double-disc synergy | NR | 958/16 951 (5.7) | E. coli 31/92 (33.7) Klebsiella spp. 68/88 | No obvious difference in 3GC resistance between CAI, HAI and HCAI but no statistical analysis |

| Lunguya54 | DRC | 2007–11 | Prospective cohort of invasive NTS | Mixed multisite—full details NR | All | NR | Manual | VITEK 2 | VITEK and double-disc synergy | Yes | 989/9364 (10.3) | NTS 3/233 (1.3) | |

| 2013 | Manual with VITEK 2 confirmation | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Mahende14 | Tanzania | 2013 | Prospective cohort of children with fever or history of fever | Rural district hospital | Paediatric (2–59 months) | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 26/808 (3.2) | S. Typhi 1/17 (5.9) | |

| 2015 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Maltha15 | Burkina Faso | 2012–13 | Prospective cohort of children with fever or signs of severe illness | Rural district hospital and health centre | Paediatric <15 years | 8/711 (1.1) | Automated | Disc diffusion | Double-disc synergy | NR | 63/711 (8.9) | NTS 1/21 (4.8) | |

| Manual | CLSI | S. Typhi 0/12 | |||||||||||

| 2014 | |||||||||||||

| Marando22 | Tanzania | 2016 | Prospective cohort of neonates with suspected sepsis | Rural district hospital | Neonates | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | Double-disc synergy | NR | 60/304 (19.7) | Klebsiella spp. 21/26 (80.8) | |

| 2018 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Mengo12 | Kenya | 2004–06 | Cross sectional study of S. Typhi isolates | Urban referral and private | All | NR | NR | Disc diffusion | NR | NR | NA | S. Typhi 6/100 (6.0) | |

| 2010 | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| Mhada55 | Tanzania | 2009–19 | Prospective cohort of neonates with suspected sepsis | Urban referral hospital | Neonates | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | NR | NR | 5/330 (1.5) | E. coli 2/14 (14.3) | Differentiates LOS and EOS but not by AMR patterns |

| 2012 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 4/22 (18.2) | |||||||||||||

| Morkel56 | South Africa | 2008 | Retrospective cohort of positive blood cultures on NICU | Urban referral hospital | Paediatric (neonates) | HIV exposed 9/54 (16.6) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 58/503 (11.5) | Klebsiella spp. 10/17 (58.8) | |

| 2014 | |||||||||||||

| Mshana57 | Tanzania | NR | Cross-sectional review of Gram-negative isolates from blood/urine/swabs | Urban referral hospital | NR | NR | NR | Disc | Double disc synergy | Yes | NR | Klebsiella spp. 29/31 (93.5) | |

| 2009 | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| Musicha6 | Malawi | 1998–2016 | Retrospective isolate surveillance from patients admitted with suspicion of sepsis | Urban referral hospital | All | NR | Automated | Disc | Double disc synergy | Yes | 29 183/194 53958 | E. coli 140/1311 (10.7) | Trends show increase in 3GC resistance over time |

| 2017 | Manual, confirmed with WGS | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 260/542 (48.0) | |||||||||||||

| Ndir11 | Senegal | 2012–13 | Case–control of patients with Enterobacteriaceae in blood | Urban referral | Paediatric | NR | NR | Disc | Double disc | 173/1800 (9.6) | E. coli 7/12 (58.3) | HAI only | |

| 2016 | Manual | FSM | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 33/40 (82.5) | |||||||||||||

| Obeng- Nkrumah59 | Ghana | 2008 | Prospective cohort of patients with Enterobacteriaceae in blood culture | Urban referral | All ages | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | Double disc | NR | NR | E. coli 5/17 (29.4) | |

| 2013 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 13/26 (50.0) | |||||||||||||

| Culture criteria NR | |||||||||||||

| Obeng- Nkrumah60 | Ghana | 2010–13 | Retrospective analysis of children with BSI | Urban referral | Paediatric (excluding neonates) | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | NR | NR | 1451/15 683 (9.3) | E. coli 63/112 (56.2) | |

| 2016 | Manual | CLSI | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 40/68 (58.8) | |||||||||||||

| Ogunlesi61 | Nigeria | 2006–08 | Mixed prospective/retrospective cohort of neonates with presumed or probable sepsis | Urban referral | Neonates | NR | Broth | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | 174/1050 (16.6) | E. coli 6/16 (37.5) | |

| 2011 | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp. 12/33 (36.4) | |||||||||||||

| Oneko62 | Kenya | 2009–13 | Prospective cohort of children with invasive NTS (nested cohort in RTS,S trial) | Rural district | Paediatric (6–12 weeks and 5–17 months) | 131/1696 (7.7) | Automated | Disc diffusion and broth microdilution | NR | Yes | 134/1692 (7.9) | NTS 17/102 (16.7) | |

| 2015 | Manual | ||||||||||||

| CLSI | |||||||||||||

| Onken19 | Tanzania (Zanzibar) | 2012–13 | Prospective cohort of patients with suspected systemic infection | Urban referral | All ages | NR | Manual, confirmed with automated | Mixed disc diffusion, confirmed with VITEK 2 | ESBL Etest and PCR | Yes | 66/470 (14.0) | E. coli 1/10 (10) | |

| Klebsiella spp. 5/11 (45.5) | |||||||||||||

| 2015 | |||||||||||||

| Manual | EUCAST | ||||||||||||

| Paterson63 | South Africa | 1996–97 | Prospective cohort of patients with K. pneumoniae BSI | Urban multisite | Adults >16 years of age | NR | Mixed | NR | Broth dilution | NR | NR | Klebsiella spp. 28/76 (37.0) | HAI only |

| Reports mortality data for 3GC resistance but not split by country | |||||||||||||

| 2004 | |||||||||||||

| Part of multi-country surveillance | |||||||||||||

| Perovic64 | South Africa | 2010–12 | Multisite prospective surveillance of K. pneumoniae isolates | Academic urban centres (multisite) | All | NR | NR | MicroScan | 14% confirmed with PCR from each region | NR | NR | Klebsiella spp. 1895/2774 (68.3) | Reports trends with increase over 3 years |

| Automated (VITEK 2) | CLSI/EUCAST and/or MicroScan guidelines | ||||||||||||

| 2014 | |||||||||||||

| Preziosi65 | Mozambique | 2011–12 | Prospective cohort of adults with fever | Urban referral hospital | Adults ≥18 years | 652/841 (77.5) | Automated | Disc diffusion | Double-disc synergy | NR | 63/841 (7.5) | E. coli 1/14 (7.1) | |

| Manual | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| 2015 | 2013–14 | ||||||||||||

| NTS 4/10 (40.0) | |||||||||||||

| Sangare66 | Mali | 2014 | Prospective cohort, patients with suspected systemic infection, referred from other health centres | Urban referral hospital | All | NR | Automated | Disc diffusion | Double disc | Yes | NR | E. coli 8/34 (23.5) | Referral patients only but not defined as HAI |

| 2016 | Manual with VITEK /MALDI-TOF confirmation | EUCAST | |||||||||||

| Klebsiella 10/34 (29.4) | |||||||||||||

| Seboxa18 | Ethiopia | 2012–13 | Prospective cohort of adults with clinically suspected sepsis and retrospective study of blood cultures positive for Gram-negative bacilli | Urban referral | All | 123/399 (30.1) | Automated (manual for retrospective cohort) | Disc diffusion | NR | NR | 38/299 (12.7) | E. coli 8/16 (50) | |

| 2015 | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| Klebsiella spp 30/35 (85.7) | |||||||||||||

| Manual | |||||||||||||

| Wasihun67 | Ethiopia | 2014 | Prospective cohort of febrile outpatients | Urban referral | All | NR | Manual | Disc diffusion | NR | Yes | NR | E. coli 9/16 (56.2) | |

| Standard biochemical | CLSI | ||||||||||||

| 2015 | |||||||||||||

| Febrile, no antibiotics for 2 weeks |

CAI, CA infection; DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; EOS, early-onset sepsis; FSM, French Society of Microbiology; HAI, HA infection; HCAI, HCA infection; LOS, late-onset sepsis; NR, not reported.

Data analysis

Prevalence is described as proportions of 3GC-R isolates, calculated from numbers of isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) or Salmonella Typhi tested against a 3GC and the number of resistant strains. Forest plots were generated, illustrating proportion estimates for each study with 95% CI calculated using the Wilson’s score method. The I2 statistic was calculated to quantify heterogeneity.

Our initial analysis plan aimed to calculate a pooled proportion of 3GC resistance for each pathogen, using random-effects meta-analysis with subanalysis by African region. However, high levels of heterogeneity amongst included studies precluded meaningful meta-analysis and we therefore present median prevalence of 3GC resistance for each pathogen, with corresponding IQR to provide an assessment of the wide range in resistance prevalence. Medians were calculated for sSA and for each African region as defined by the United Nations Statistics Division.9

Heterogeneity of proportion estimates was explored using predefined subgroup analysis by African region and a post hoc subgroup analysis by age group of study population. Visual inspection of resulting forest plots was carried out and a test for subgroup differences applied where visual inspection suggested a likely difference in subgroup proportion estimates and where more than two studies contributed to each subgroup. We additionally examined for trends in proportions estimates over time using visual inspection of forest plots, ordered by year of publication, and a linear meta-regression model. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Risk of bias assessment

In terms of delineating a population estimate, we noted that the most likely risk of bias is patient selection. Additionally, the laboratory techniques and their implementation may differ in sensitivity and specificity and could also introduce bias. We modified the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist to design a risk-of-bias assessment to fit our research question, assessing risk of bias in patient recruitment and laboratory techniques used (Table S4). The assessment was performed by both R.L. and P.M. and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

To explore for indirect evidence of publication bias, we examined 3GC resistance estimates against the number of isolates included in the study, as smaller studies may be subject to publication bias.

Results

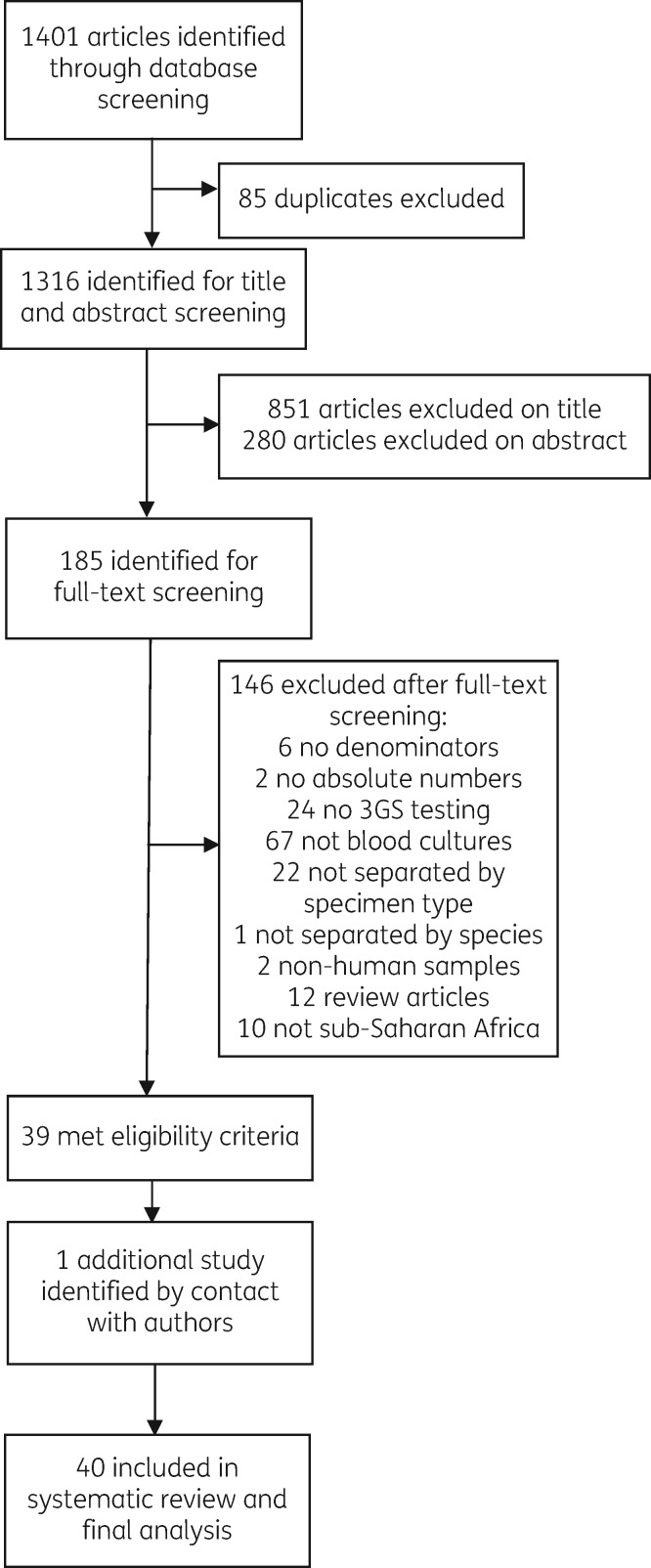

The online database search combined with reference review from key papers generated 1401 articles and, of these, 185 abstracts were selected for full-text review (Figure 1). Original data for one article were retrieved by direct communication with authors.10 Forty articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review, which synthesizes 11 404 isolates. Of these, 20 articles reported proportions of 3GC resistance in E. coli and 28 in Klebsiella spp. Twelve studies reported proportions of 3GC resistance in NTS and four in S. Typhi.

Figure 1.

Study selection.

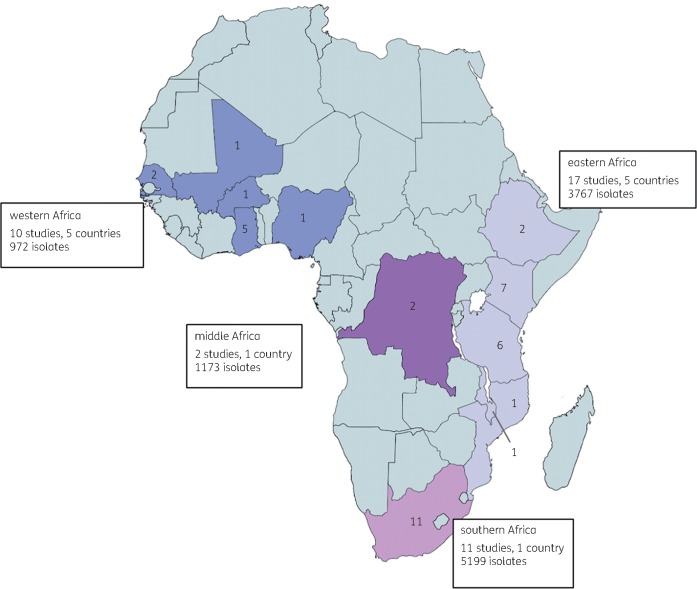

Table 1 presents the characteristics of all included studies. Data were available from 12 countries across all four sSA regions (Figure 2), with the highest proportion of studies (11/40) from South Africa. All studies were observational. There were 30 studies that recruited cohorts of patients with confirmed or suspected BSI, 16 of which were prospective, 13 retrospective and 1 mixed. Four studies were cross-sectional reviews of isolates and three tested isolates collected as part of longitudinal multisite surveillance. There was one case–control study, designed to estimate mortality from 3GC-R BSI.11

Figure 2.

Geographical location of studies reporting proportions of 3GC resistance amongst E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and NTS. Numbers in country indicate the number of studies included in the review for each country. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

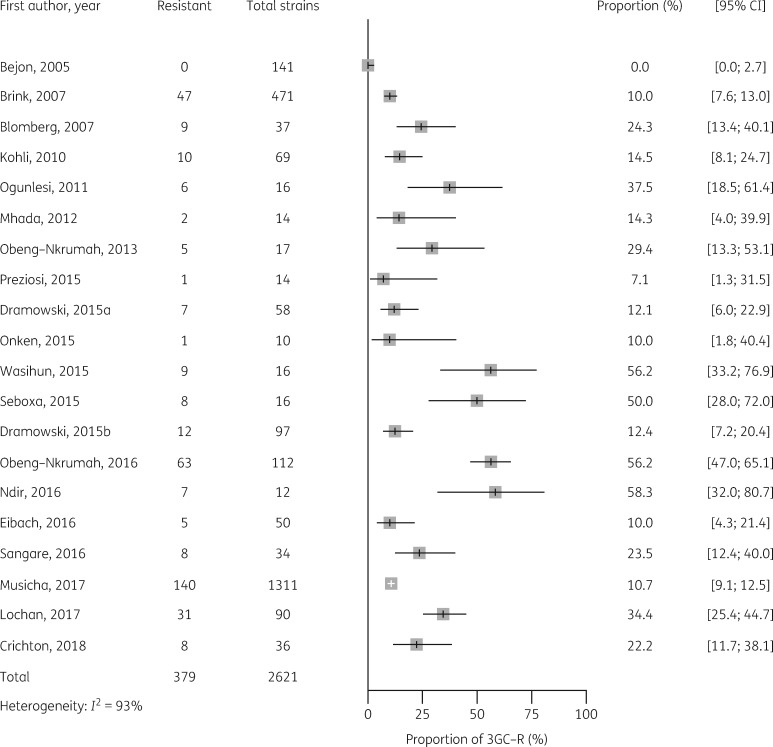

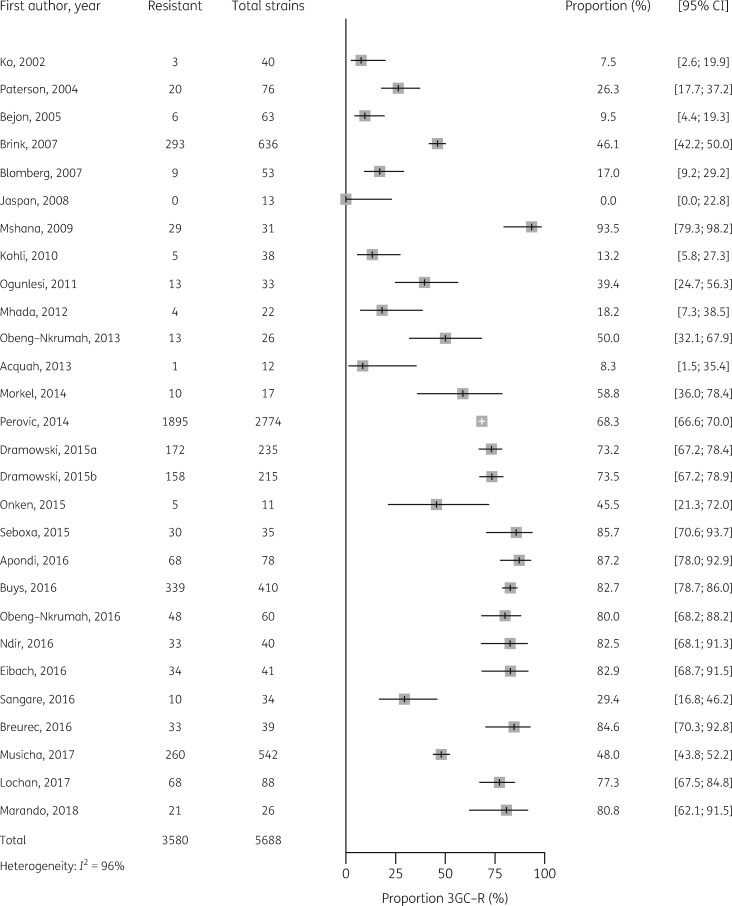

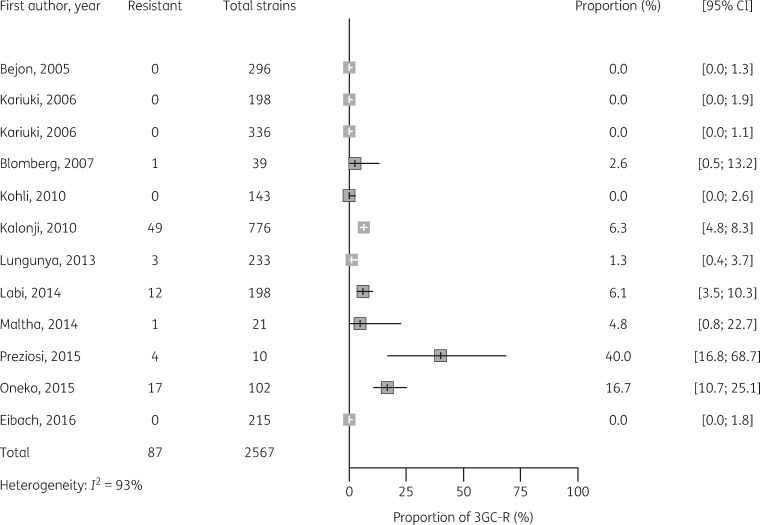

Median estimates of 3GC resistance in E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and salmonellae for sSA are shown in Table 2, together with median estimates by African region, and forest plots of individual studies are shown in Figures 3–5. The median point estimate of 3GC resistance in E. coli BSI from 20 studies was 18.4% (IQR 10.5 to 35.2) (Table 2). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 93%) (Figure 3) and not explained by prespecified subgroup analysis by African region (Figure S1). Median point estimates of 3GC resistance in Klebsiella BSI were higher across all regions than for E. coli, with an overall estimate of 54.4% (IQR 24.3 to 81.2) from 28 studies (Table 2, Figure 4). As with E. coli, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 96%) and not explained by differences in African region (Figure S1).

Table 2.

Median prevalence of 3GC resistance in E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and NTS BSI, shown by African region

| Prevalence, % (IQR) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | overall 3GC resistance | eastern | middle | western | southern |

| E. coli | 18.4 (10.5–35.2) | 14.3 (10.0–24.3) | no data | 33.5 (25.0–51.6) | 12.4 (12.1–22.2) |

| 20 studies | 9 studies | 6 studies | 5 studies | ||

| Klebsiella spp. | 54.4 (24.3–81.2) | 46.7 (17.3–84.5) | no data | 58.3 (34.6–82.6) | 63.6 (39.1–76.2) |

| 28 studies | 10 studies | 8 studies | 10 studies | ||

| NTS | 1.9 (0–6.1) | 0 (0–9.6) | 1.3, 6.3 | 4.8 (2.4–5.4) | no data |

| 12 studies | 7 studies | 2 studies | 3 studies | ||

Figure 3.

Proportion of 3GC resistance in 2621 E. coli BSI isolates from 20 studies.

Figure 4.

Proportion of 3GC resistance in 5688 Klebsiella spp. BSI isolates from 28 studies.

3GC resistance amongst NTS was low, at a median of 1.9% (IQR 0 to 6.1) in isolates from 12 studies (Figure 5). The highest proportions of 3GC resistance in NTS came from eastern Africa (Kenya and Mozambique) but subgroup analysis by African region did not explain interstudy variability (Figure S1). Four studies in this review carried out 3GC susceptibility testing on S. Typhi isolates.12–15 Of these, two studies from Kenya12 and Tanzania14 found 3GC resistance with prevalence of 6% (6/100) and 5.9% (1/17), respectively. These studies did not report confirmatory ESBL testing on cephalosporin-resistant S. Typhi strains.

Figure 5.

Proportion of 3GC resistance in 2567 NTS BSI isolates from 12 studies.

The earliest published reports of 3GC resistance in Gram-negative BSI are from 2002.16 Graphical exploration of forest plots, ordered by year of publication (Figures 3–5), suggested a trend towards increased 3GC resistance over time for Klebsiella, NTS and E. coli. Meta-regression by year of publication supported a significant trend towards increased resistance over time for Klebsiella (P<0.01), NTS (P=0.02) and E. coli (P=0.02).

Studies reporting mortality estimates from 3GC-R BSI are shown in Table 3. Only one study, a paediatric case–control study in Senegal, was designed to determine attributable mortality from 3GC resistance as a primary outcome, finding that 3GC-R BSI remained the only significant independent risk factor for death in multivariable logistic regression, (OR=2.9, 95% CI 1.8–7.3, P=0.001) regardless of antibiotic treatment choice.11 Seven further studies10,17–22 provide mortality estimates for patients with 3GC-R BSI, but were not designed to estimate attributable mortality from these infections. These studies were a mixture of retrospective and prospective designs, variably providing ORs, RRs and case-fatality rates and incorporating different characteristics in multivariable models. It was therefore not possible to combine these into a single mortality estimate using meta-analysis. Where available, case-fatality rates from individual studies were high, ranging from 60% to 100%, with all but one study concluding 3GC-R BSI to be a predictor of fatal outcome in patients.

Table 3.

Studies reporting mortality in patients with 3GC-R BSI

| Study, publication year | Study type | Population | Country | Total patients in study | Pathogens | Case-fatality rate, 3GC-R 3GC-S n (%) | Adjusted mortality estimate from 3GC-R BSI (95% CI) | Author conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blomberg17 | Prospective cohort | Paediatric; 0–7 years | Tanzania | 1632 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | 15/21 (71.0) | OR 12.87 (4.95–33.48) | Inappropriate antimicrobial therapy due to 3GC resistance predicts fatal outcome |

| NR | Multivariable model adjusted for: age <1 month, sex, HIV status, malaria, other underlying disease, polymicrobial blood culture | |||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| Urban referral hospital | ||||||||

| Children with suspected systemic infection based on IMCI | ||||||||

| Dramowski10 | Retrospective cohort | Paediatric; 0–14 years | South Africa | 864 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae (mortality data available for Klebsiella spp.) | 21/122 (17.2) | Not reported by AMR type | AMR not associated with BSI mortality |

| Urban referral hospital | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| NR | ||||||||

| Children with suspected sepsis or severe focal infection | ||||||||

| Onken19 | Prospective cohort | All ages; no range reported | Zanzibar | 469 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | 3/5 (60.0) | Not reported | No significantly higher case-fatality rate in 3GC-R compared with susceptible infections, but small numbers |

| 2015 | Urban referral hospital | 4/11 (36.0) | ||||||

| Patients with fever (≥38.3°C in adults, ≥38.5°C in children) or hypothermia (<36.0°C), tachypnoea >20/min, tachycardia >90/min or suspected systemic bacterial infection | ||||||||

| Seboxa18 | Prospective cohort | Adults; 13–98 years | Ethiopia | 232 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | 11/11 (100) | RR 9.00 (1.42–57.12) | Inappropriate antimicrobial therapy due to 3GC-R infections predicts fatal outcome |

| 2015 | Urban referral hospital | 1/9 (11.1) | No multivariable analysis | |||||

| Patients with clinical suspicion of septicaemia and 2 of the 3 following criteria: axillary temperature ≥38.5°C or ≤36.5°C, pulse ≥90 beats/min and frequency of respiration ≥20/min | ||||||||

| Buys21 | Retrospective cohort | Paediatric; IQR 2–16 months | South Africa | 410 | Klebsiella spp. | NR | OR 1.09 (0.55–2.16) | MDR K. pneumoniae BSI is associated with high mortality in children |

| Urban referral hospital | Multivariable model adjusted for: age, gender, nutrition, HIV, ESBL, patient in PICU, patient needing to go to PICU, continuous IV infusion for >3 days before the BSI, Klebsiella BSI without source, chronic underlying medical condition excluding HIV, and skin erosions | |||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| Electronic list of Klebsiella bloodstream isolates from hospital database | ||||||||

| Eibach20 | Prospective cohort | All ages; IQR 1–18 years | Ghana | 7172 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | NR | Whole cohort:

|

3GC-R BSI is associated with higher mortality than non-3GC-R, but this is highly dependent on age |

| 2016 | Rural primary healthcare centre Patients with fever ≥38°C or history of fever within 24 h after admission or neonates with suspected neonatal sepsis | |||||||

| No mortality difference from 3GC-R infections in neonates and higher overall mortality | ||||||||

| Ndir11 | Case–control | Paediatric; 0–17 years | Senegal | 173 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | NR (54.8) | OR 2.9 (1.8–7.3) | 3GC-R BSI is associated with fatal outcome in HA-BSI |

| 2016 | Urban referral hospital | NR (15.4) | Multivariable model adjusted for: age <1 month, prematurity, underlying comorbidities, admission diagnoses, invasive procedures, inappropriate antibiotics | |||||

| Cases—patients with an HA-BSI caused by Enterobacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Controls—patients who did not experience an infection during the study period, randomly selected from the hospital database | ||||||||

| Marando44 2018 | Prospective cohort | Neonates; IQR 4–8 days | Tanzania | 304 | Mixture of Enterobacteriaceae | NR (34.4) NR | HR 2.4 (1.2–4.8), Cox regression | Neonates infected with 3GC-R BSI have significantly higher mortality than EBSL negative or non-bacteraemic patients |

| OR 2.71 (1.22–6.03), multivariable model adjusted for age and sex | ||||||||

3GC-S, 3GC susceptible; IMCI, integrated management of childhood infection.

Additional study population characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were 22 studies in paediatric populations, including 6 exclusively in neonates. Four studies recruited adults over 16 years of age, 13 recruited from all age groups and one study did not report age of participants from which blood cultures were obtained. Given that age categories were generally well reported and could explain differences between proportion estimates, we carried out post hoc stratified analysis by age group (Figure S2). Visual inspection of resulting forest plots suggested no difference in proportion estimates by age group for E. coli (Figure S2a), but potentially higher proportion estimates for 3GC-R Klebsiella in children than in adults (Figure S2b). A higher proportion estimate for 3GC resistance in NTS was seen in adults (Figure S2c) but there was only one study in this age group.

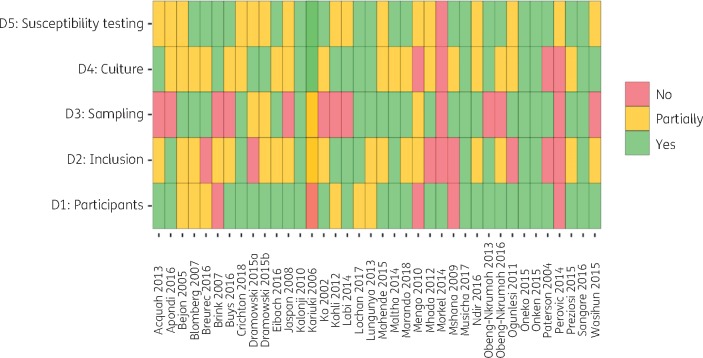

Results of the risk-of-bias assessment are shown in Figure 6. Bias in prevalence estimates was most likely introduced through selection of study participants. Many studies did not report criteria for blood culture sampling in the population recruited and many were conducted in special populations such as neonatal ICUs (NICUs). Most studies described blood culture methods well, but few reported external quality control (QC) in laboratory methods, resulting in a moderate risk of bias introduction across this domain for most studies.

Figure 6.

Results of risk-of-bias assessment. Domain 1: are the characteristics of participants adequately described? Domain 2: are the inclusion criteria explicit and appropriate? Domain 3: are the criteria for blood culture sampling explicit? Domain 4: are the blood culture methods precise and reported? Domain 5: are the AST methods precise and reported? This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

As a measure of potential publication bias, plots of 3GC resistance estimates against study size, for E. coli and Klebsiella spp., are shown in Figure S2. For E. coli and Klebsiella, the larger studies tended to report lower resistance estimates (Figure S3), suggesting a potential for publication bias against studies reporting a smaller number of isolates.

Blood culture processing techniques varied. An automated system for blood culture incubation was used in 18 studies, whilst manual systems were used in 10. Three studies reported a mixture of manual and automated techniques and nine did not report which methods were used. AST methods varied, but most laboratories used disc diffusion (22/40). Four studies used VITEK 2, with the remainder using Etest, MicroScan or a mixture of techniques. Three studies did not report which AST methods were used. Most studies (30/40) used CLSI breakpoint guidelines, with the remainder using national or international guidelines as shown in Table 1. Twenty-two studies carried out ESBL confirmatory testing in 3GC-R isolates. Of these, 10 used double-disc synergy, with the remainder using broth dilution, PCR or a mixture of methods.

The classification of isolates by source, for example whether community-acquired (CA) or hospital-acquired (HA), or urban versus rural, is key to the interpretation of these data. Thirty studies tested BSIs from patients presenting to public referral or private hospitals in urban settings, with nine recruiting from rural district hospitals and one from a mixed urban/rural setting. HIV status of individuals who had blood culture sampling was recorded in only 11 studies and 1 study was exclusively a cohort of HIV-infected individuals. Six studies investigated the difference in blood culture pathogens and prevalence of resistance between CA and HA or healthcare-associated (HCA) infection. Of these, five found a higher prevalence of 3GC resistance in HA infections. Two studies were cohorts of patients with HA infection and one study included only patients with suspected CA BSI. Of the six neonatal studies, two differentiated early-onset from late-onset neonatal sepsis but did not report on differences in proportions of 3GC resistance between the two groups.

Discussion

Our systematic review has synthesized over 11 000 blood culture isolates from patients in sSA, finding high levels of 3GC resistance amongst the key Enterobacteriaceae, E. coli and Klebsiella spp., and emerging resistance amongst salmonellae. Ceftriaxone is one of the most widely used broad-spectrum antibiotics in Africa, indicated in the empirical management of adult and paediatric patients at district-, regional- and tertiary-level care facilities.23–25 Limited access to carbapenems and aminoglycosides may make 3GC-R BSI untreatable in some settings.8 The striking lack of mortality data we describe in this review is therefore a major barrier to a comprehensive understanding of the burden of AMR in this setting.

We found a high median prevalence of 3GC resistance in E. coli BSI, greater than estimates from high-income countries, which are typically less than 10%.26 Interpreting the significance of proportion estimates in the absence of trend data is challenging and the latter will require long-term, high-quality surveillance. Some of the most comprehensive published trend data come from Malawi, where blood culture surveillance for 18 years has shown a recent, rapid rise in 3GC resistance amongst Enterobacteriaceae in adult8 and paediatric patients.27 Between 2003 and 2016, the proportion of 3GC-R E. coli rose from 0.7% to 30.3%, with similar trends in other non-Salmonella Enterobacteriaceae.8 The alarming trends described in Malawi highlight the urgent need for systematic AMR surveillance data from Africa that will inform both policy on access to antimicrobials and public health programmes aimed at reducing DRIs.

Resistance amongst Klebsiella spp., at 50.0%, was higher than for E. coli. Klebsiella spp. frequently acquire AMR genes and are a common cause of BSI in vulnerable populations, often causing localized outbreaks in settings such as NICUs and paediatric ICUs (PICUs).28 3GC-R Klebsiella spp. are a particular challenge in neonatal infection as, in addition to the vulnerability of this age group to severe bacterial infection, many antimicrobials are either relatively contraindicated (e.g. chloramphenicol) or not locally available as IV agents (e.g. ciprofloxacin). In the single study from this review in which mortality from 3GC-R Klebsiella was recorded, all patients died; clearly, prospective studies investigating transmission dynamics of this nosocomial pathogen are required in order to support targeted interventions to reduce their development and spread.21

Although resistance to first-line antimicrobials, such as ampicillin, chloramphenicol and co-trimoxazole, is common among NTS in sSA,29 3GC resistance has remained low, but may represent an emerging problem (Figure 5).30 Our review found sporadic cases of ceftriaxone resistance amongst S. Typhi from three countries, but these studies did not carry out confirmatory testing for the presence of ESBL genes. Although not captured by our inclusion criteria, ESBL-producing S. Typhi have been detected in sSA.31,32 In light of the recent outbreak of fluoroquinolone-resistant and ESBL-producing S. Typhi in Pakistan, resulting from the acquisition of ESBL-encoding plasmids by the H58 haplotype (genotype 4.3.1) known to be prevalent in Africa, this is concerning.33 Surveillance of S. Typhi non-susceptibility in Africa will be essential, as emergence of drug-resistant strains is associated with increase in transmissibility of typhoid and resurgence of disease.34

We found marked heterogeneity amongst 3GC resistance proportion estimates, which was not explained by differences in African region or age group of patients. Prevalence of resistance amongst key pathogens is likely to be influenced by a variety of clinical parameters including HIV status, healthcare attendance and prior antibiotic use, but these data were rarely reported and subgroup analysis by these factors was impossible. Detailed clinical and demographic parameters should be collected by studies that aim to understand the epidemiology of DRIs and the drivers of transmission of AMR pathogens.

We aimed to provide an estimate of the mortality burden from 3GC-R BSI, but this was prohibited by the scarcity of outcome data and heterogeneity of study designs. DRIs are associated with adverse patient outcomes in high-income settings, including high mortality and increased length of hospital stay.35,36 In Africa, where the prevalence of bacterial sepsis is high,4 late presentation to secondary care is common and the availability of alternative antimicrobials and advanced laboratory diagnostics is limited, the impact of AMR on patients is predictable, but currently unknown.

This review has a number of limitations. Heterogeneity is highly likely with reviews of this nature and the variety of populations described make a true general population estimate difficult. Potential sources of heterogeneity that we have not explored include the diversity of laboratory microbiological methods used, both for organism identification and for AST. Most studies did not report whether or how they engaged with external quality assurance programmes. We did not exclude these from the review, as they likely represent the vast majority of facilities in sSA, but this may be an important source of variation in estimates. Confirmatory testing for ESBL production using phenotypic or molecular methods is recommended for any organisms showing reduced susceptibility to an indicator 3GC, but such confirmatory methods were employed in just under half the studies included in this review. However, resistance to 3GCs on primary screening tests is sufficient evidence to infer 3GC resistance; therefore, again, we did not exclude these studies from the analysis. Our assessment of publication bias suggested a potential bias against publication of studies reporting on a small number of isolates. However, the differences in resistance estimates reported by studies of different sizes are much more likely explained by differences in the included populations, particularly since the majority of studies were not designed to estimate resistance, but reported estimates as part of blood culture surveillance or sepsis cohorts.

The limitations of available data we highlight in this review, together with the high level of unexplained interstudy heterogeneity, prompt the need for standardization of AMR research. In future, studies should be required to provide a clear account of the microbiological sampling criteria, study or surveillance sampling frame and laboratory methods used to generate resistance data. Studies should collect and report clinical metadata associated with the sample, including empirical antibiotic regimens, HIV status and the clinical setting, including level of the health system and intensity of care. There are increasing efforts in the AMR surveillance community to identify exactly which data are minimally acceptable and which data are ideal, to produce useful prevalence estimates that contribute to global repositories such as the WHO’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS).37

We have documented proportions of 3GC-R BSI from a large number of bloodstream isolates across sSA, expanding on previous reviews that have focused on clinical syndromes,38 paediatric populations39 or limited African regions.40 Using inclusion criteria that captured surveillance studies in addition to clinical cohorts, we have, to our knowledge, captured the largest AMR dataset available from sSA and therefore provide the most comprehensive summary of 3GC-R BSI from the continent. In doing so, we demonstrate the lack of available clinical data and show that the burden of DRIs on patients in Africa remains unknown. Low-income countries have multiple, competing priorities for limited healthcare resources and budgets, therefore clinicians, researchers and policymakers will need to demonstrate that AMR is a priority for patients in these settings. This information does not currently exist and AMR prevalence studies from sSA, however comprehensive, will need to be accompanied by robust morbidity, mortality and economic outcome data, to allow for a true understanding of the burden of AMR on patients and health systems.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Clinical PhD Fellowship to R.L., University of Liverpool block award grant number 203919/Z/16/Z).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S. et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016; 387: 168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Essack SY, Desta AT, Abotsi RE. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the WHO African region: current status and roadmap for action. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017; 39: 8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42 Suppl 2: S82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reddy EA, Shaw AV, Crump JA.. Community-acquired bloodstream infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 417–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O’Neill J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2014. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf.

- 6. Musicha P, Cornick JE, Bar-Zeev N. et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infection isolates at a large urban hospital in Malawi (1998-2016): a surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 1042–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ardal C, Outterson K, Hoffman SJ. et al. International cooperation to improve access to and sustain effectiveness of antimicrobials. Lancet 2016; 387: 296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Statistics Division. Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use. 1999. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

- 10. Dramowski A, Cotton MF, Rabie H. et al. Trends in paediatric bloodstream infections at a South African referral hospital. BMC Pediatr 2015; 15: 33.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ndir A, Diop A, Faye PM. et al. Epidemiology and burden of bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae in a pediatric hospital in Senegal. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0143729.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mengo DM, Kariuki S, Muigai A. et al. Trends in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi in Nairobi, Kenya from 2004 to 2006. J Infect Dev Ctries 2010; 4: 393–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalonji LM, Post A, Phoba MF. et al. Invasive Salmonella infections at multiple surveillance sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2011-2014. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 4: S346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahende C, Ngasala B, Lusingu J. et al. Bloodstream bacterial infection among outpatient children with acute febrile illness in north-eastern Tanzania. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 289.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maltha J, Guiraud I, Kaboré B. et al. Frequency of severe malaria and invasive bacterial infections among children admitted to a rural hospital in Burkina Faso. PLoS One 2014; 9: e89103.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ. et al. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 2002; 8: 160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blomberg B, Manji KP, Urassa WK. et al. Antimicrobial resistance predicts death in Tanzanian children with bloodstream infections: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2007; 7: 43.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seboxa T, Amogne W, Abebe W. et al. High mortality from blood stream infection in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is due to antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0144944.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Onken A, Said AK, Jørstad M. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of microbes causing bloodstream infections in Unguja, Zanzibar. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0145632.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eibach D, Belmar Campos C, Krumkamp R. et al. Extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae causing bloodstream infections in rural Ghana, 2007-2012. Int J Med Microbiol 2016; 306: 249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buys H, Muloiwa R, Bamford C. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections at a South African children’s hospital 2006-2011, a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 570.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marando R, Seni J, Mirambo MM. et al. Predictors of the extended-spectrum-beta lactamases producing Enterobacteriaceae neonatal sepsis at a tertiary hospital, Tanzania. Int J Med Microbiol 2018; 308: 803–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO. Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Illnesses with Limited Resources—Second Edition. 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/81170/9789241548373_eng.pdf? sequence=1. [PubMed]

- 24.WHO. IMAI District Clinician Manual: Hospital Care for Adolescents and Adults: Guidelines for the Management of Illnesses with Limited Resources. 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77751/9789241548281_Vol1_eng.pdf? sequence=1.

- 25.Malawi Ministry of Health. Malawi Standard Treatment Guidelines—Fifth Edition. 2015. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23103en/s23103en.pdf.

- 26. Bou-Antoun S, Davies J, Guy R. et al. Descriptive epidemiology of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England, April 2012 to March 2014. Euro Surveill 2016; 21: pii=30329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iroh Tam PY, Musicha P, Kawaza K. et al. Emerging resistance to empiric antimicrobial regimens for pediatric bloodstream infections in Malawi (1998-2017). Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69: 61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haller S, Eller C, Hermes J. et al. What caused the outbreak of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit, Germany 2009 to 2012? Reconstructing transmission with epidemiological analysis and whole-genome sequencing. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007397.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feasey NA, Masesa C, Jassi C. et al. Three epidemics of invasive multidrug-resistant Salmonella bloodstream infection in Blantyre, Malawi, 1998-2014. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 4: S363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kariuki S, Okoro C, Kiiru J. et al. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium sequence type 313 from Kenyan patients is associated with the blaCTX-M-15 gene on a novel IncHI2 plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 3133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Phoba MF, Barbe B, Lunguya O. et al. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi producing CTX-M-15 extended spectrum β-lactamase in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65: 1229–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akinyemi KO, Iwalokun BA, Alafe OO. et al. bla CTX-M-I group extended spectrum beta lactamase-producing Salmonella typhi from hospitalized patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist 2015; 8: 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klemm EJ, Shakoor S, Page AJ. et al. Emergence of an extensively drug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi clone harboring a promiscuous plasmid encoding resistance to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins. MBio 2018; 9: e00105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pitzer VE, Feasey NA, Msefula C. et al. Mathematical modeling to assess the drivers of the recent emergence of typhoid fever in Blantyre, Malawi. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 4: S251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cosgrove SE, Kaye KS, Eliopoulous GM. et al. Health and economic outcomes of the emergence of third-generation cephalosporin resistance in Enterobacter species. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG. et al. Burden of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay associated with bloodstream infections due to Escherichia coli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turner P, Fox-Lewis A, Shrestha P. et al. Microbiology Investigation Criteria for Reporting Objectively (MICRO): a framework for the reporting and interpretation of clinical microbiology data. BMC Med 2019; 17: 70.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leopold SJ, van Leth F, Tarekegn H. et al. Antimicrobial drug resistance among clinically relevant bacterial isolates in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 2337–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williams PCM, Isaacs D, Berkley JA.. Antimicrobial resistance among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: e33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sonda T, Kumburu H, van Zwetselaar M. et al. Meta-analysis of proportion estimates of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in East Africa hospitals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2016; 5: 18.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Acquah SE, Quaye L, Sagoe K. et al. Susceptibility of bacterial etiological agents to commonly-used antimicrobial agents in children with sepsis at the Tamale Teaching Hospital. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 89.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Apondi OE, Oduor OC, Gye BK. et al. High prevalence of multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary teaching hospital in Western Kenya. Afr J Infect Dis 2016; 10: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bejon P, Mwangi I, Ngetsa C. et al. Invasive Gram-negative bacilli are frequently resistant to standard antibiotics for children admitted to hospital in Kilifi, Kenya. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56: 232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Breurec S, Bouchiat C, Sire JM. et al. High third-generation cephalosporin resistant Enterobacteriaceae prevalence rate among neonatal infections in Dakar, Senegal. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 587.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brink A, Moolman J, da Silva MC. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of selected bacteraemic pathogens from private institutions in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2007; 97: 273–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crichton H, O’Connell N, Rabie H. et al. Neonatal and paediatric bloodstream infections: pathogens, antimicrobial resistance patterns and prescribing practice at Khayelitsha District Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2018; 108: 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dramowski A, Madide A, Bekker A.. Neonatal nosocomial bloodstream infections at a referral hospital in a middle-income country: burden, pathogens, antimicrobial resistance and mortality. Paediatr Int Child Health 2015; 35: 265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaspan HB, Huang LC, Cotton MF. et al. Bacterial disease and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in HIV-infected, hospitalized children: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2008; 3: e3260.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kariuki N. et al. Characterisation of community acquired non-typhoidal Salmonella from bacteraemia and diarrhoeal infections in children admitted to hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Microbiol 2006; 6: 101.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kiiru J. et al. Decreasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella isolated from children with bacteraemia in a rural district hospital, Kenya. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2006; 28: 166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kohli R, Omuse G, Revathi G.. Antibacterial susceptibility patterns of blood stream isolates in patients investigated at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J 2010; 87: 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Addison NO. et al. Salmonella blood stream infections in a tertiary care setting in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 3857.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lochan H, Pillay V, Bamford C. et al. Bloodstream infections at a tertiary level paediatric hospital in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 750.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lunguya O, Lejon V, Phoba MF. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in invasive non-typhoid Salmonella from the Democratic Republic of the Congo: emergence of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility and extended-spectrum beta lactamases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2103.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mhada TV, Fredrick F, Matee MI. et al. Neonatal sepsis at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; aetiology, antimicrobial sensitivity pattern and clinical outcome. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 904.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morkel G, Bekker A, Marais BJ. et al. Bloodstream infections and antimicrobial resistance patterns in a South African neonatal intensive care unit. Paediatr Int Child Health 2014; 34: 108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mshana SE, Kamugisha E, Mirambo M. et al. Prevalence of multiresistant gram-negative organisms in a tertiary hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Res Notes 2009; 2: 49.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388: 1603–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Obeng-Nkrumah N, Twum-Danso K, Krogfelt KA. et al. High levels of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in a major teaching hospital in Ghana: the need for regular monitoring and evaluation of antibiotic resistance. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89: 960–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Obeng-Nkrumah N, Labi AK, Addison NO. et al. Trends in paediatric and adult bloodstream infections at a Ghanaian referral hospital: a retrospective study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2016; 15: 49.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ogunlesi TA, Ogunfowora OB, Osinupebi O. et al. Changing trends in newborn sepsis in Sagamu, Nigeria: bacterial aetiology, risk factors and antibiotic susceptibility. J Paediatr Child Health 2011; 47: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oneko M, Kariuki S, Muturi-Kioi V. et al. Emergence of community-acquired, multidrug-resistant invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease in rural Western Kenya, 2009-2013. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 4: S310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A. et al. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in nosocomial infections. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Perovic O, Singh-Moodley A, Duse A. et al. National sentinel site surveillance for antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in South Africa, 2010 - 2012. S Afr Med J 2014; 104: 563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Preziosi M, Zimba TF, Lee K. et al. A prospective observational study of bacteraemia in adults admitted to an urban Mozambican hospital. S Afr Med J 2015; 105: 370–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sangare SA, Maiga AI, Guindo I. et al. Prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from blood cultures in Mali. J Infect Dev Ctries 2016; 10: 1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wasihun AG, Wlekidan LN, Gebremariam SA. et al. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of blood culture isolates among febrile patients in Mekelle Hospital, Northern Ethiopia. Springerplus 2015; 4: 314.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.