Abstract

Statin-induced necrotising autoimmune myopathy (SINAM) is a rare disease characterised by proximal muscle weakness and elevated creatine kinase levels that is usually in the thousands. Anti-3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl co-enzyme A reductase (HMGCR) antibodies are associated with SINAM. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an inflammatory disease of the liver that is usually of unknown aetiology but can also be associated with concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disorders. We are reporting a case of biopsy proven AIH associated with SINAM in a patient presenting with oropharyngeal dysphagia. The patient had elevated anti-HMGCR antibodies and anti-smooth muscle antibodies. SINAM and AIH were confirmed by muscle biopsy and liver biopsy, respectively. The patient had complete resolution of his symptoms and complete normalisation of his liver function tests after 6 months of the treatment.

Keywords: muscle disease, unwanted effects / adverse reactions, rheumatology, liver disease

Background

Around 43 million of the US population have been receiving prescriptions for lipid lowering drugs, out of which 90% are statins.1 Statins have been recommended to reduce the risk and complications of atherosclerotic disease, which is the leading cause of death in the USA. About 9%–20% of patients report muscle-related symptoms falling under the statin-induced myopathy spectrum.2 The spectrum includes myalgia, myositis, rhabdomyolysis and statin-induced necrotising autoimmune myopathy (SINAM).2

Case presentation

A male patient in his 60s was admitted to the hospital after he presented with dysphagia for 3 weeks. Symptoms started abruptly with dysphagia for both solids and liquids and progressively worsened. He was also experiencing regurgitation of food particles, halitosis and weight loss of 25 pounds over the 3-week period. He denied any nausea, vomiting, heartburn, odynophagia, hematemesis, melaena, joint pains or skin rashes. He had no history of neck cancers or masses and never had a prior endoscopy. His medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and a previous stroke of the central and left side of the pons with no residual deficits. His home medications included aspirin, atorvastatin 40 mg once daily, lisinopril and metformin. The patient started taking atorvastatin 1 year prior to presentation when he had the stroke. He denied history of smoking and he drank alcohol only occasionally. Age appropriate cancer screening was normal. On admission, his vital signs were within normal limits. He looked cachectic with prominent facial bones. He had slightly weak speech. Neurological exam revealed proximal muscle weakness in the bilateral deltoid muscles (3/5). The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

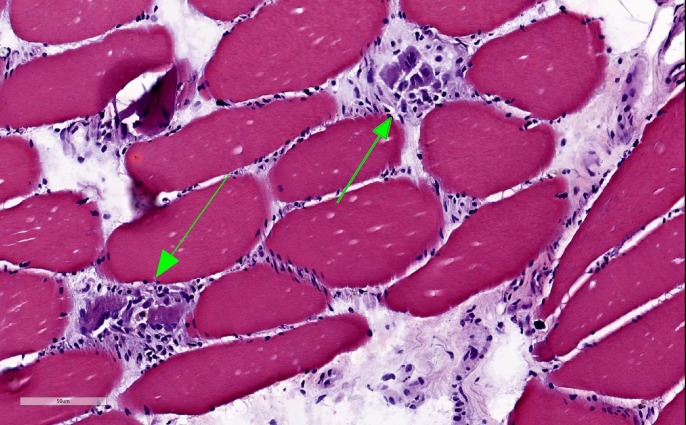

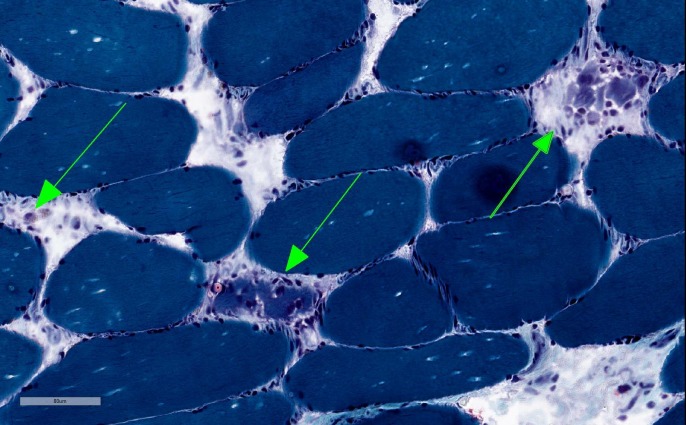

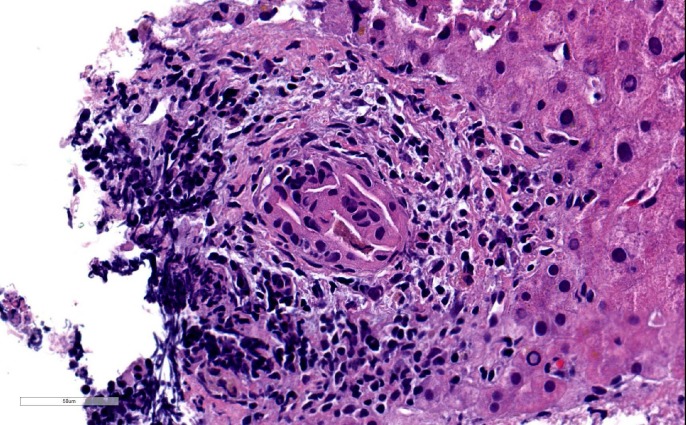

Initial laboratory results showed mild anaemia with haemoglobin at 12.2 g/dl, elevated aspartate transaminase (AST) at 735 Int Unit/L, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) at 426 Int Unit/L, elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) at 231 Int Unit/L, elevated creatine kinase (CK) at 18196 Unit/L, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate at 80 mm/hr and elevated C-reactive protein at 70 mg/L. Thyroid stimulating hormone and vitamin D were within normal limits. Albumin and total bilirubin were within normal limits. Hepatitis A IgM antibody, IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc), hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody were all negative. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was unremarkable and modified barium swallow was consistent with an oropharyngeal cause of dysphagia. MRI of the brain was obtained, which showed no acute findings. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed normal liver echogenicity without focal lesions and also no intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts dilation. All autoimmune serological tests were negative (ANA, Jo-1, MI-2, PL-7, PL- 12, PL-155/140, OJ, EJ, SRP, U2-snRNP, NXP-2, Ku, SSA, SSB, MDA-5, SAE1, PM-SCl, fibrillarin and TIF1) except for an elevated anti-3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl co-enzyme A reductase (HMGCR) antibodies with a level of more than 200 (normal range is 1–19) and also elevated anti-smooth muscle antibodies at 1:160 (normal ratio is 1:16). Muscle biopsy from left vastus lateralis muscle showed histopathological findings consistent with mild to moderately active necrotising myopathy (figures 1,2). Liver biopsy showed portal hepatitis with bile duct lymphocytic exocytosis (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Muscle biopsy showing necrotic myofibrils using H&E staining.

Figure 2.

Muscle biopsy showing necrotic myofibrils using trichrome staining.

Figure 3.

Liver biopsy showing bile duct lymphocytes with ductal degenerative changes using H&E staining.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, myasthenia gravis, polymyositis and statin-induced myopathy.

Treatment

The patient was started on oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily and was given intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 50 g daily for 3 days. Initially, he had a nasopharyngeal duodenal tube that was later replaced by a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube for feeding. Patient was continued on corticosteroids and he was transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility for physical and speech therapy. Prednisone dose was tapered as outpatient. Other immunosuppressive medications (eg, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate and rituximab) were not initiated at the time of presentation due to the lack of evidence-based therapeutic guidelines for SINAM treatment, patient’s preference and the fear of potential side effects.

Outcome and follow-up

Eventually, the patient started an oral diet after 3 months, and his PEG tube was removed about 6 months later. His liver function tests trended down to normal. His prednisone dose was tapered to 10 mg daily over 6 months.

Discussion

SINAM has an incidence of 2 per million cases per year.3 Its onset can be days to years after continuous exposure to statins.4 Most of the cases have been reported with atorvastatin, but no data on certain statins or dose dependency have been found.5 Pathogenesis of SINAM is still not completely understood, but an association has been observed between statin exposure and autoantibodies against HMGCR. Statins upregulate muscle expression of HMGCR, which persists in regenerating muscle fibres even after discontinuation of statin use, thus leading to sustained muscle damage and pointing to its autoimmune nature. Certain other genetic and environmental cofactors are hypothesised to be associated with this upregulation.6 Interestingly, these antibodies are also found without statin exposure, especially in young adults with chronic myopathies.3 Anti-HMGCR antibody (ELISA) can lead to the diagnosis of SINAM given supportive clinical findings. The ELISA test has a reported sensitivity of 94.4% and specificity of 99.3%.7 Definitive diagnosis can be established with muscle biopsy, which shows myofibre necrosis without significant inflammation (in contrast to dermatomyositis and polymyositis) and dominant macrophages with myophagocytosis.8 Other causes of SINAM such as malignancy (paraneoplastic necrotising myositis), anti-signal recognition particle (SRP) antibodies, connective tissue disorder and HIV should be considered.9 Inflammatory myopathies such as polymyositis and dermatomyositis must be excluded since both have an association with statins.10 AST and ALT can be elevated as a result of the muscle injury, but they might be a manifestation of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). AIH is known to present sometimes with other concurrent extrahepatic autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes mellitus and systemic lupus erythematosus.6 There is only one reported case of AIH associated with SINAM in which both diagnosis were confirmed by a histological examination.11 However, the patient in the reported case presented with proximal muscle weakness and pain, whereas our patient presented with dysphagia. Another case was reported to have elevated liver enzymes but it seems work up for AIH was not initiated.12 It was not clear whether the elevation in liver enzymes was due to hepatitis or myolysis. In our case, the significant elevation of AST and ALT and also the elevation of ALP lead to the suspicion of the presence of a hepatic disorder in addition to SINAM. The diagnosis of AIH was confirmed by the presence of positive anti-smooth muscle antibodies and the liver biopsy results.

Treatment of SINAM usually consists of high dose steroids. IVIG or other immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate and rituximab have been used in multiple cases with good outcomes. Evidence-based therapeutic guidelines for SINAM treatment do not exist. Clinical improvement in SINAM correlates with falling CK levels as well as anti-HMGCR antibody titres.8

Patient’s perspective.

At the time of my illness at the hospital, I was worried about my ability to eat again. Doctors comforted me and told me that this would take a few months. Fortunately, I was able to eat again and my feeding tube was removed.

I want doctors everywhere to be aware of my disease and be able to treat and diagnose it appropriately.

Learning points.

Perform an extensive neuromuscular exam in patients presenting with unexplained oropharyngeal dysphagia to help narrow down the differential diagnosis.

Statin-induced necrotising autoimmune myopathy (SINAM) should be on the differential diagnosis in patients who have myopathy, elevated creatine kinase levels and are taking statins.

Autoimmune hepatitis can be associated with SINAM and should be considered when there is a disproportionate elevation in aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, disproportionate elevation in ALT level compared with AST level or an elevation of other liver markers.

Recovery period in patients with SINAM is prolonged and can take up to 3 months for resolution of initial symptoms.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors substantially contributed to the design of the case, revised it critically, approved the final draft and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. NV wrote the initial case presentation and investigation parts. He reviewed the grammar and he was part of reviewing and editing the last version of the article. OQA and SK wrote and edited the summary, background, differential diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, discussion, learning points and references. They also reviewed and edited the case presentation and investigation parts. They reviewed the entire case and made editions on the last version of the article. Please note that SK and OQA contributed equally to this paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Mercado C, DeSimone AK, Odom E, et al. . Prevalence of cholesterol treatment eligibility and medication use among adults--United States, 2005-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1305–11. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6447a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nichols L, Pfeifer K, Mammen AL, et al. . An unusual case of statin-induced myopathy: anti-HMGCoA necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1879–83. 10.1007/s11606-015-3303-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohassel P, Mammen AL. Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy and anti-HMGCR autoantibodies. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:477–83. 10.1002/mus.23854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. . Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:234–5. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Essers D, Schäublin M, Kullak-Ublick GA, et al. . Statin-associated immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: a retrospective analysis of individual case safety reports from VigiBase. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2019;75:409–16. 10.1007/s00228-018-2589-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teufel A, Weinmann A, Kahaly GJ, et al. . Concurrent autoimmune diseases in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:208–13. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c74e0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamann PDH, Cooper RG, McHugh NJ, et al. . Statin-induced necrotizing myositis - a discrete autoimmune entity within the "statin-induced myopathy spectrum". Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:1177–81. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. . Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:4087–93. 10.1002/art.34673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liang C, Needham M. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:612–9. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834b324b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Padala S, Thompson PD. Statins as a possible cause of inflammatory and necrotizing myopathies. Atherosclerosis 2012;222:15–21. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palamuthusingam D, Mantha M, Dheda S. HMG CoA reductase inhibitor associated myositis and autoimmune hepatitis. Intern Med J 2017;47:1213–5. 10.1111/imj.13561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dixit A, Abrudescu A. A case of atorvastatin-associated necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, mimicking idiopathic polymyositis. Case Rep Rheumatol 2018;2018:1–3. eCollection 2018 10.1155/2018/5931046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]