Abstract

A 9-year-old female with Trisomy 21 with complex craniovertebral instability causing severe cervicomedullary compression underwent occipitocervical fusion. This paper will discuss the anaesthetic management and highlight the use of the Narcotrend monitor not only as a depth of consciousness monitor but more importantly as a tool to detect surgery-induced cerebral hypoperfusion by monitoring the right and left cerebral hemispheres independently and simultaneously.

Keywords: healthcare improvement and patient safety, anaesthesia, orthopaedic and trauma surgery

Background

Trisomy 21 is the most common chromosomal abnormality with an incidence of 1 in every 800 births.1 It affects all races and both genders. Aside from distinct facial features (flattened nasal bridge, upslanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds and large protruding tongue), several organ systems are also affected in varying degrees. The effects on the musculoskeletal system include hypotonia, joint hyperflexibility and atlantoaxial instability (AAI).

Among Trisomy 21 patients, 10%–20% will present with AAI.2 It is usually an asymptomatic condition and is diagnosed radiographically. However, 1%–2% will progress to symptomatic AAI due to spinal cord compression by the displaced odontoid. Symptomatic AAI patients require urgent evaluation and intervention to prevent further neurological deterioration.

We report a case of a complex craniovertebral instability with a dystopic os odontoideum and an irreducible C1–C2 instability causing severe cervicomedullary compression necessitating occipito-C1–C2–C3 fusion with C1 laminectomy and foramen magnum decompression. This paper will demonstrate how the use of the Narcotrend monitor supplemented the anaesthetic management and complemented the image-guided navigation system and patient-specific drill guide template in the safe completion of the surgical procedure in an immature and deformed spine.

Case presentation

A 9-year-old 24.9 kg ASA 2 female with Trisomy 21 presented with a 10-month history of progressive quadriparesis. Diagnostic imaging revealed atlantoaxial subluxation of C1 and C2, upper spinal canal stenosis, severe cervicomedullary junction compression and dystopic os odontoideum (figures 1 and 2). An occipito-C1–C2–C3 fusion with C1 laminectomy and foramen magnum decompression was planned to address this.

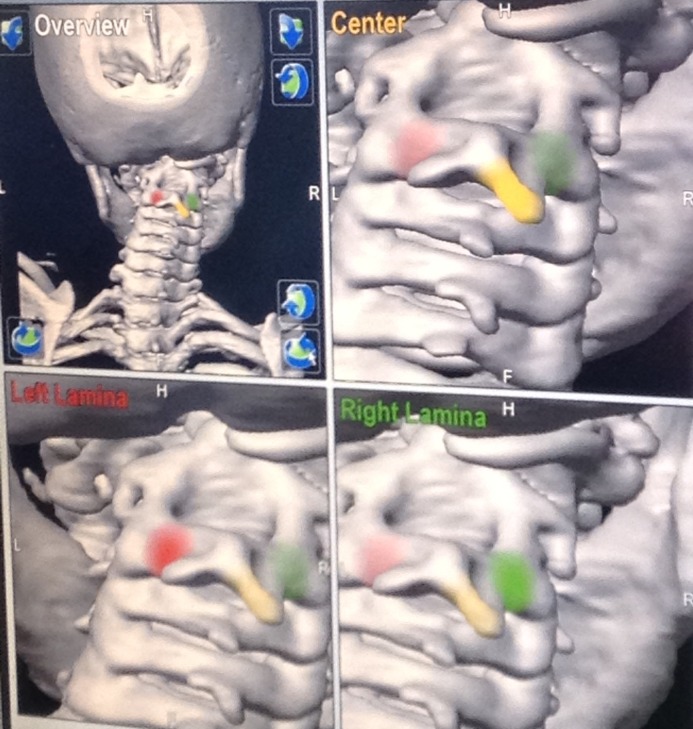

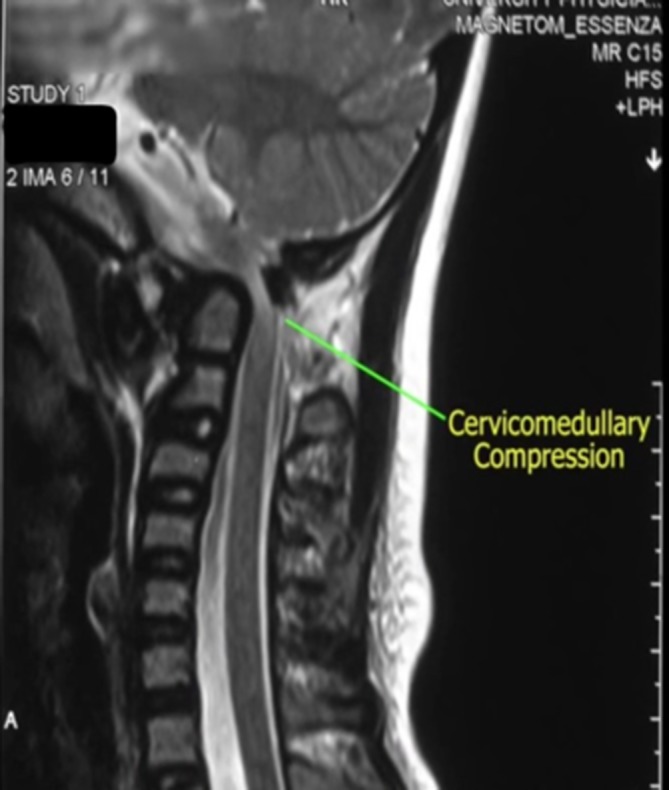

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of patient’s CT scan showing irreducible C1C2 instability.

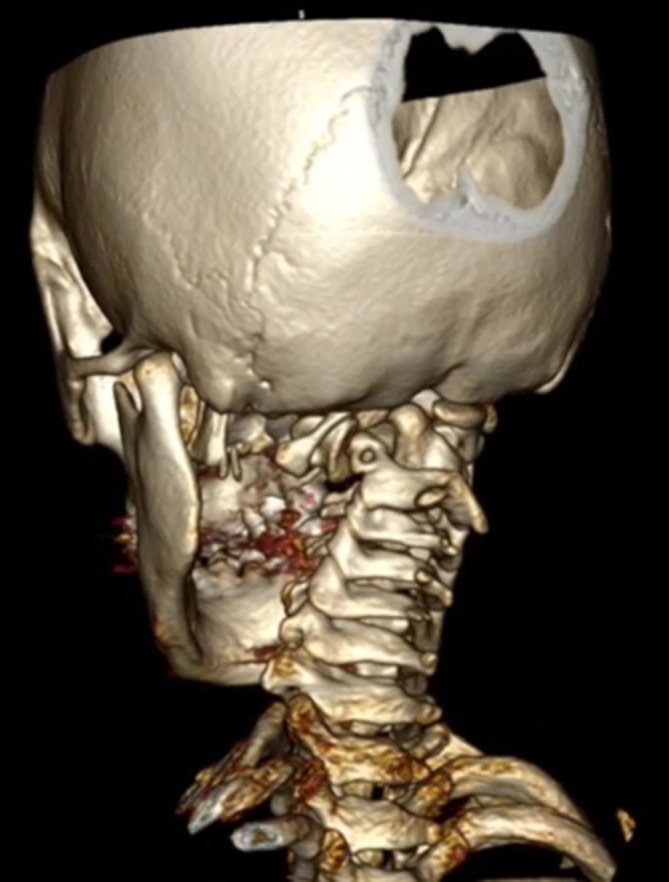

Figure 2.

MRI showing severe spinal canal stenosis.

She had medically controlled hypothyroidism and had a previous VSD closure and PDA ligation at 1 year of age. Developmental milestones were at par with age. Pertinent physical examination findings include macroglossia, three fingerbreadth mouth opening, adequate thyromental distance and no loose teeth. Full cervical range of motion was not assessed but she did not exhibit any pain across the typical range of motion. She did not have a neck collar in situ prior to the surgery.

Preoperatively, a 1:1 three-dimensional (3D) model of the patient’s skull and cervical spine was created using a desktop 3D printer to map out the extent of decompression and to serve as a guide for the fabrication of patient-specific drill guide templates for pedicle screw fixation (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional printed model of patient’s skull base and cervical spine showing extent of planned decompression.

Figure 4.

Depiction of planned surgical approach using 3D printed model of patient’s skull base and cervical spine and patient-specific drill guide template. 3D, three dimensional.

She was received with the following vital signs: blood pressure (BP): 100/50 mm Hg, heart rate (HR): 90, respiratory rate (RR): 18, SpO2: 100%. Intravenous induction commenced with midazolam 1 mg, fentanyl 12.5 μg, atropine 0.25 mg, propofol 50 mg, rocuronium 25 mg. Glottic opening was visualised using a Macintosh 2 blade and the trachea intubated with a cuffed 5.0 ETT. No difficulty was encountered during the mask ventilation, laryngoscopy and intubation. An oral pack was placed. She was then maintained on sevoflurane 3 vol%.

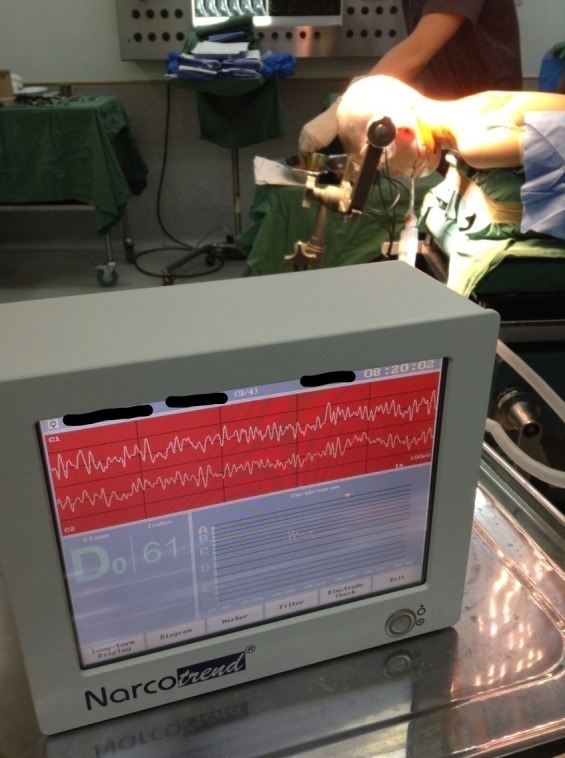

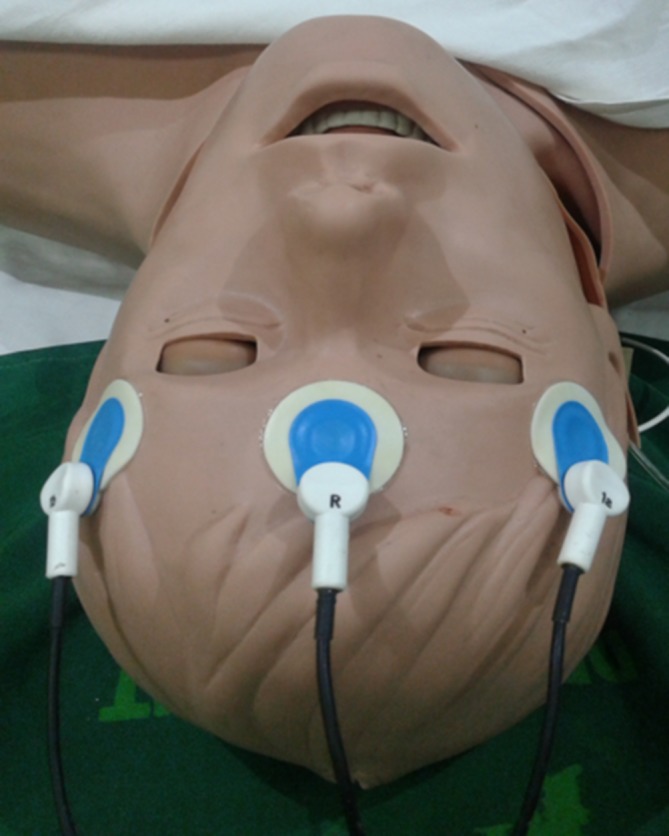

While on a supine position, lidocaine 1%+ bupivacaine 0.25%+ epinephrine 1:100 000 was infiltrated subcutaneously on the area where the pins were fixed. Once placed in the prone position, her head was fixed with a Mayfield head clamp. Additional rocuronium 10 mg and fentanyl 12.5 μg were also given. Bony prominences and pressure points were padded. The Narcotrend monitor two-channel lead electrodes were attached accordingly giving an initial Narcotrend stage of D0 and similar degree of electrical cortical activity on both hemispheres of the brain (figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Narcotrend two-channel lead electrodes being checked and readjusted to address the impedance shown in the Narcotrend monitor.

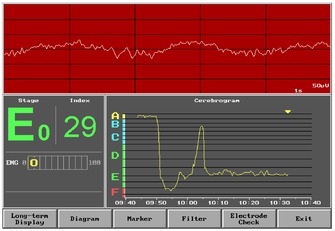

Figure 6.

Patient placed in the prone position with Narcotrend two-channel leads in place. The raw EEG waves from the right and left side of the brain monitored independently and simultaneously are shown on the upper portion of the screen. The Narcotrend stage and index showing anaesthetic depth is depicted on the lower left portion of the screen. Cerebrogram is depicted in the right lower portion showing the trend of Narcotrend stage. EEG, electroencephalography.

She was placed on mechanical ventilation with the following settings: tidal volume: 200 mL (8 mL/kg), RR: 16, PEEP: 4, I:E ratio: 1:2. Prior to incision, cefazolin was given intravenously while lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:100 000 was infiltrated locally over the posterior midline incision area.

Intraoperatively, vital signs were BP: 90–120/50–70 mm Hg, HR: 70–90 bpm, SpO2: 98%–100%. Additional doses of fentanyl and rocuronium as well as ephedrine boluses were given. Instead of relying solely on haemodynamic values (eg, BP, HR), Narcotrend was used as a guide on whether additional anaesthetic (sevoflurane or fentanyl), decreased concentration of sevoflurane or additional vasopressor, will be given during the surgery. For anatomic guidance, an image-guided navigation system (Brainlab Kolibri V.1) was used (figure 7), while Narcotrend (MonitorTechnik, Bad Bramstedt, Germany) was used for neurophysiological monitoring. Narcotrend stage was maintained at stage D0–D1 (Narcotrend index 48–60) throughout the operation with no note of sudden fluctuations in brain activity pattern on the involved hemisphere or discrepancies between the two raw electroencephalography (EEG) waveforms even during the crucial decompression and instrumentation phase. To ensure proper screw placement, patient-specific 3D-created drill guide templates were used for pedicle screw fixation. Estimated blood loss was 400 mL and 1 unit of packed red blood cells was transfused. Total operative time was 4 hours and 35 min.

Figure 7.

Monitor view of the navigation system used for anatomic guidance intraoperatively.

After the surgery, she was placed back on a supine position. Local anaesthetic was infiltrated subcutaneously over the sites where the fixator of the halo-vest was applied. Postoperative analgesics were intravenous nalbuphine 5 mg every 6 hours and intravenous ketorolac 15 mg every 6 hours. She was kept intubated and transferred to the paediatric intensive care unit. Rocuronium drip (0.5 mg/kg/hour) and midazolam drip (4 μg/kg/min) were initially administered to facilitate mechanical ventilation and keep her calm and relatively immobile. She was slowly weaned off the mechanical ventilator and extubated on the fourth postoperative day. She was discharged after 11 days with resolution of her neurological deficits.

Outcome and follow-up

She was discharged on the 11th postoperative day with resolution of her neurological deficits. Since the operation, she has been on constant follow-up with her orthopaedic surgeon. Her halo-vest has been removed and she has been able to resume her usual daily activities with no recurrence of her preoperative neurological deficits.

Discussion

Due to the limited space and intimate anatomic relationship, posterior cervical spine surgery inherently puts neural structures at risk. Reported incidence of neurological complications associated with these procedures in the paediatric population is variable (0, 0.3%, 3.3%).3–5

Intraoperative electrophysiologic neurological monitoring was introduced to check spinal cord function intraoperatively. Somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) evaluates the dorsal column function while transcranial electric motor evoked potential (MEP) evaluates the anterolateral cortical spinal tracts. When used in combination for scoliosis surgery, the risk of postoperative neurological deficit was decreased to 0.12%.6 Other studies yielded similar results.7–9

SSEP and MEP in posterior cervical spine surgeries in children have been shown to be an effective diagnostic tool with a sensitivity of 75%–100% and a specificity of 98.5%–100%.10 11 However, it did not always lead to prevention or reversal of neurological deficits. Moreover, presence of pre-existing neurological deficits may either prevent obtaining baseline MEP signals or provide variable signals intraoperatively resulting in unnecessary wake-up test.11–13

The vertebral artery was also deemed in danger. From the subclavian artery at the lower anterior neck, it ascends, takes on a serpentine course and ends up traversing the foramen magnum where it merges intracranially to form the basilar artery to provide blood supply to the brainstem.14 It is most susceptible to injury anterior to C7, laterally along C3 to C7 and posteriorly at C1 and C2.15 Considering the surgical approach, an undetected inadvertent vertebral artery compression at C1 and C2 level leading to brainstem ischaemia during the instrumentation phase in a limited and preoperatively compromised surgical field is a concern for this patient.

Inadvertent vertebral artery injury during cervical spine surgery is rare with a reported incidence of 0.08%.16 Outcomes vary ranging from pseudoaneurysm, reversible neurological deficit, infarction, late-onset bleeding and even death. Four cases of unrecognised brainstem ischaemia during cervical spine surgery have been reported.17–20 These all involved adult patients who underwent anterior cervical spine decompression and instrumentation surgery. Three had unrecognised brainstem ischaemic stroke while one had a haematoma that compressed on the vertebral artery. All were haemodynamically stable intraoperatively except for one patient who had a transient reduction in the systolic BP. All patients did not have intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring and the events were only discovered after completion of the surgery.

Generally, in procedures wherein brain ischaemia is a concern, SSEP and EEG are the neuromonitoring modalities of choice.21 It is worth noting that a 5.4% incidence of postoperative neurological deficits were noted in patients who had no accompanying SSEP changes.21

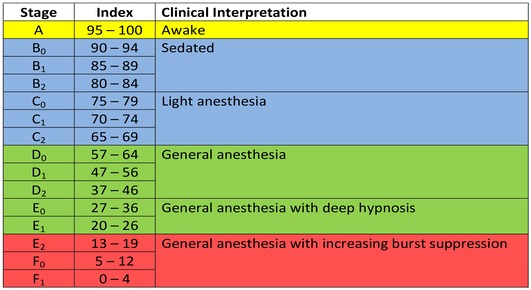

Processed EEG monitors are monitors that acquire, integrate, analyse and convert raw EEG data through a proprietary multivariable algorithm to a dimensionless number meant to reflect anaesthetic depth. One such commercially available monitor is the Narcotrend. After an automatic artefact analysis, the raw EEG signal is processed using a multiparametric mathematical algorithm based on visual pattern recognition using a scale originally proposed by German neurophysiologist Kugler.22 It then classifies EEG into six stages ranging from A (awake) to F (increasing burst suppression progressing to electrical silence) (figure 8). The Narcotrend stages are further subdivided into indexes from 100 (awake) to 0 (electrical silence) allowing for statistical analysis for scientific studies.23 The recommended Narcotrend stage ensuring adequate anaesthetic depth is between D0 and E1.

Figure 8.

Narcotrend stage (A–F), Narcotrend index (0–100) and clinical interpretation.

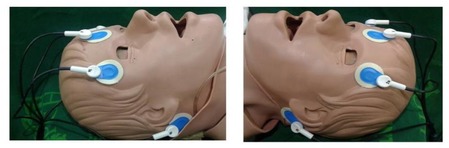

Narcotrend is available in two modes, the one-channel and two-channel mode. The one-channel mode is the one used for standard depth of anaesthesia evaluation employing three ECG pads placed on the forehead (figures 9 and 10). The two-channel mode involves placement of three ECG pads on the forehead and two ECG pads along the mastoid process (figure 11). The two-channel mode is peculiar to the Narcotrend and is not available in other currently commercially available processed EEG monitors. In this mode, raw EEG data from both hemispheres of the brain are collected and displayed simultaneously on top of each other on the upper half of the monitor screen allowing the user to visually compare the signals from both sides.23 24

Figure 9.

Narcotrend one-channel mode lead placement.

Figure 10.

Narcotrend screen showing the one-channel mode.

Figure 11.

Narcotrend two-channel mode lead placement.

EEG waveforms are the net result of neuronal electrical activity. It is closely related to cerebral blood flow (CBF), such that, varying degrees of ischaemia will lead to a characteristic EEG pattern. Once CBF drops to 25–35 mL/100 g brain tissue, there is decrease in faster frequencies (alpha, beta). At 12–18 mL/100 g brain tissue, there is an increase in slower frequencies (delta). If it decreases further, there is electrical silence and the EEG becomes isoelectric.25 26 It is postulated that by using the two-channel mode of Narcotrend, if significant ischaemia ensues, decreased cortical activity will be reflected on the affected side serving as an early warning during the surgery. This mode was created to monitor CBF during carotid endarterectomy. The two-channel mode of Narcotrend is similar to the Neurotrac (Interspec, Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, USA) which has previously been shown to detect ischaemic events during carotid clamping.27 To date, there is still a paucity of literature regarding the two-channel mode of Narcotrend.

Another unique feature of the Narcotrend is the incorporation of age-related EEG changes in its processing algorithm.22 28 29 Upon turning on the machine, the main menu requires entering first the patient’s birthdate before you can proceed with the other functions. This is a step that cannot be bypassed and is crucial in the interpretation of the collected raw EEG signals from the patient. Details regarding the two-channel mode and relationship of patient’s age in the calculation of Narcotrend stage and index are proprietary and not available to the public.

Ensuring adequate anaesthetic depth in a Trisomy 21 patient, maintaining adequate spinal cord perfusion and detecting inadvertent vertebral artery compression leading to cerebral ischaemia are interrelated goals facilitated with the use of Narcotrend. Trisomy 21 patients have been shown to have lesser CNS catecholamine levels suggesting that deep levels of anaesthesia can be achieved with a lower minimum alveolar concentration, that is, lower dose of volatile anaesthetic.30 31 Maintaining BP at or slightly above the patient’s baseline is recommended to maintain perfusion during cervical spine surgery since patients with chronically compressed cervical cord seem to have inadequate perfusion reserves making them vulnerable to ischaemic injury.32 Traditionally, haemodynamic values (BP, HR) are used as surrogate markers of cortical activity, that is, low BP denotes deeper level of hypnosis and vice versa. With the Narcotrend in use, it was possible to assess the degree of cortical activity and aid in deciding on whether a low BP reading necessitates decreasing the volatile anaesthetic or giving additional fluids and vasopressor (ephedrine) bolus.28 On the other hand, inadequate depth of anaesthesia can easily be ruled out as a cause of high BP. This is particularly important since there are portions in the surgery wherein epinephrine-soaked cottonoids are placed in the field to minimise blood loss.

To detect inadvertent vertebral artery compression-induced cerebral ischaemia, the two-channel mode of Narcotrend was used instead of the one-channel mode. The raw EEG signals from both sides are displayed independently and simultaneously together with the Narcotrend index. It is hypothesised that the two-channel mode of Narcotrend will reflect the cortical activity on both hemispheres during the surgery. Recently, other processed EEG monitors (BIS, cerebral state monitor) have attempted to simulate the two-channel mode of the Narcotrend to monitor cerebral hypoperfusion during carotid endarterectomy under general anaesthesia by using two separate units to monitor the right and left side of the brain independently and simultaneously.33 34

The lack of variation between the raw EEG waves from both sides during the surgery could be attributed to the following factors: (1) BP was maintained within the recommended range, (2) use of navigation system, (3) use of 3D printed patient-specific drill guide templates for pedicle screw fixation. These contributed to preventing iatrogenic vertebral artery compression and was duly documented by the Narcotrend.

It is worth noting that during its early years in the market, the Narcotrend was shown to be unreliable in detecting consciousness during general anaesthesia based on the isolated forearm technique.35 The isolated forearm technique was first described by Tunstall in the 1970s to detect wakefulness among parturients having caesarean section under general anaesthesia.36 A forearm is isolated from paralysis using a cuffed tourniquet. The ability of a patient to squeeze her hand after a verbal command is indicative of an awake state. Although considered the current gold standard for connected consciousness monitoring, to date, there is no publication indicating its sensitivity and specificity. In addition, in a randomised controlled trial wherein the control group were exposed to meaningless radio static, the incidence of hand movement was similar on the intervention group (received verbal command) and the control group.37

Another group showed that the Narcotrend did not differentiate between awareness and unconsciousness.38 It is worth mentioning that in this study, the Narcotrend was used to analyse prerecorded digitalised EEG readings collected from another depth of anaesthesia monitor. This may have contributed to the results it yielded.

Currently, there are evidences supporting the value of Narcotrend in titrating drug dosages both in the adult and paediatric population in the operating room and the non-operating room setting.39–44

Additional concerns among paediatric Trisomy 21 patients are their impaired cell-mediated immunity and collagen abnormalities making them vulnerable to infection, delayed healing, junctional instability and bone graft resorption.45 Records from a multicentre cooperative study group revealed a high complication rate (64%) after posterior fusion in children with AAI.46 These complications include loss of reduction, pedicle fracture and fusion extension. Providing a stress-free and relatively if not completely immobile state during the postoperative course is important in such cases.

The patient was kept intubated and sedated postoperatively to lessen the risk of graft displacement. A multimodal technique, including local anaesthetic, strong opioid and NSAID, was employed to provide adequate pain control. Mixed agonist–antagonist opioid was used because it does not have an effect on the detrusor muscle allowing early assessment of bladder control.47

Although no ischaemic episodes were detected intraoperatively, this case illustrates the ability of the two-channel mode of the Narcotrend to display cortical activity from both cerebral hemispheres independently and simultaneously allowing real-time visual comparison. To date, the Narcotrend has been reported to promptly detect two intraoperative episodes of cerebral hypoperfusion on a patient undergoing cryoablation allowing the team early and rapid detection of the ongoing insult.48 In addition, it was also shown to detect a malfunctioning syringe pump leading to inadvertent light anaesthesia.49 These two scenarios show that Narcotrend can quickly detect cortical activity either through a sudden hypoperfusion leading to electrical silence or failure of anaesthetic delivery leading to awakening allowing physicians to recognise and address the impending issue. It shows how cortical activity can be affected by various factors and physicians should be quick to recognise it to correct reversible causes.

In summary, a balanced anaesthesia technique addressing adequate anaesthetic depth, perfusion to the spinal cord and brain, intraoperative and postoperative analgesia all contributed in the successful uneventful completion of the surgical procedure. Determining the significance and implication of the information derived from processed EEG monitors is still an ongoing process. It is important to correlate all information clinically and not allow a single number or EEG pattern be a determinant of decision making.

Learning points.

In patients at risk for developing intraoperative vertebral artery injury-induced cerebral ischaemia, the two-channel mode of the Narcotrend monitor can be considered as a potentially useful adjunct monitoring tool as it simultaneously shows the signals from the two hemispheres of the brain.

During cervical spine surgery, maintaining normotension or even slightly higher blood pressure than the baseline is beneficial in preventing spinal cord and cerebral ischaemia.

Multimodal analgesia (NSAID, strong mixed agonist–antagonist opioid, local anaesthetic infiltration) addresses acute postoperative pain and allows for a smooth weaning postoperatively.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge PD Dr med, Dr hort Arthur Schultz and PD Dr med Barbara Schultz (Department of Anesthesiology Hannover Medical School).

Footnotes

Contributors: The main author (EKV) consolidated all the data, created the first draft and created the final manuscript after being critically perused by the coauthor. The coauthor (DV and RB) actively contributed in acquiring the data (details regarding patient’s case profile, perioperative care), conceptualising the outline of the discussion as well as participated in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Marion RW, Levy PA. Chromosomal disorders : Marcdante KJ, Kliegman RM, Nelson essentials of pediatrics. 8th ed Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2019: 180. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ali FE, Al-Bustan MA, Al-Busairi WA, et al. Cervical spine abnormalities associated with Down syndrome. Int Orthop 2006;30:284–9. 10.1007/s00264-005-0070-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crostelli M, Mariani M, Mazza O, et al. Cervical fixation in the pediatric patient: our experience. Eur Spine J 2009;18 Suppl 1:20–8. 10.1007/s00586-009-0980-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendenhall S, Mobasser D, Relyea K, et al. Spinal instrumentation in infants, children, and adolescents: a review. J Neurosurg 2019;23:1–15. 10.3171/2018.10.PEDS18327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verhofste BP, Glotzbecker MP. Perioperative acute neurological deficits in instrumented pediatric cervical spine fusions. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zuccaro M, Zuccaro J, Samdani AF, et al. Intraoperative neuromonitoring alerts in a pediatric deformity center. Neurosurg Focus 2017;43:E8 10.3171/2017.7.FOCUS17364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fehlings MG, Brodke DS, Norvell DC, et al. The evidence for intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgery: does it make a difference? Spine 2010;35:S37–46. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d8338e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laratta JL, Ha A, Shillingford JN, et al. Neuromonitoring in spinal deformity surgery: a multimodality approach. Global Spine J 2018;8:68–77. 10.1177/2192568217706970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagarajan L, Ghosh S, Dillon D, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiology monitoring in scoliosis surgery in children. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2019;4:11–17. 10.1016/j.cnp.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tobert DG, Glotzbecker MP, Hresko MT, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring for pediatric cervical spine surgery. Spine 2017;42:974–8. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mohammad W, Lopez D, Isley M, et al. The recognition, incidence, and management of spinal cord monitoring alerts in pediatric cervical spine surgery. J Pediatr Orthop 2018;38:e572–6. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson–Holden TJ, Padberg AM, Lenke LG, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative monitoring for pediatric patients with spinal cord pathology undergoing spinal deformity surgery. Spine 1999;24:1685–92. 10.1097/00007632-199908150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang S, Zhang J, Tian Y, et al. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring to patients with preoperative spinal deficits: judging its feasibility and analyzing the significance of rapid signal loss. Spine J 2017;17:777–83. 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy. 14th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2017: 12. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peng CW, Chou BT, Bendo JA, et al. Vertebral artery injury in cervical spine surgery: anatomical considerations, management, and preventive measures. Spine J 2009;9:70–6. 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu WK, Kannan A, Mai HT, et al. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Vertebral Artery Injury in 16 582 Cervical Spine Surgery Patients: An AOSpine North America Multicenter Study. Global Spine J 2017;7:21S–7. 10.1177/2192568216686753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsai Y-F, Doufas AG, Huang C-S, et al. Postoperative coma in a patient with complete basilar syndrome after anterior cervical discectomy. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 2006;53:202–7. 10.1007/BF03021828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dickerman RD, Zigler JE. Atraumatic vertebral artery dissection after cervical corpectomy: a traction injury? Spine 2005;30:E658–661. 10.1097/01.brs.0000184557.81864.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg AJ, Jensen CD, Jeavons RP, et al. Unexplained perioperative vertebrobasilar stroke in a patient undergoing anterior cervical decompression and disc arthroplasty. Int J Spine Surg 2015;9:4 10.14444/2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jonnavithula N, Cherukuri K, Durga P, et al. Transient brain stem ischemia following cervical spine surgery: an unusual cause of delayed recovery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2014;30:432–3. 10.4103/0970-9185.137290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gunter A, Ruskin KJ. Intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring: utility and anesthetic implications. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016;29:539–43. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schultz B, Grouven U, Schultz A, et al. Automatic classification algorithms of the EEG monitor Narcotrend for routinely recorded EEG data from general anaesthesia: a validation study. Biomed Tech 2002;47:9–13. 10.1515/bmte.2002.47.1-2.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kreuer S, Wilhelm W. The Narcotrend monitor. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2006;20:111–9. 10.1016/j.bpa.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Somchai A. Monitoring for depth of anesthesia: a review. J Biomed Graph Comput 2012;2:119–27. 10.5430/jbgc.v2n2p119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Messick JM, Casement B, Sharbrough FW, et al. Correlation of regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) with EEG changes during isoflurane anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy: critical rCBF. Anesthesiology 1987;66:344–9. 10.1097/00000542-198703000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foreman B, Claassen J. Quantitative EEG for the detection of brain ischemia. Crit Care 2012;16:216 10.1186/cc11230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tempelhoff R, Modica PA, Grubb RL, et al. Selective shunting during carotid endarterectomy based on two-channel computerized electroencephalographic/compressed spectral array analysis. Neurosurgery 1989;24:339–44. 10.1227/00006123-198903000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weber F, Hollnberger H, Gruber M, et al. The correlation of the Narcotrend index with endtidal sevoflurane concentrations and hemodynamic parameters in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2005;15:727–32. 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dennhardt N, Arndt S, Beck C, et al. Effect of age on Narcotrend Index monitoring during sevoflurane anesthesia in children below 2 years of age. Pediatr Anaesth 2018;28:112–9. 10.1111/pan.13306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bhattarai B, Kulkarni AH, Rao ST, et al. Anesthetic consideration in downs syndrome--a review. Nepal Med Coll J 2008;10:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kobel M, Creighton RE, Steward DJ, et al. Anaesthetic considerations in Down's syndrome: experience with 100 patients and a review of the literature. Can Anaesth Soc J 1982;29:593–9. 10.1007/BF03007747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hindman BJ, Palecek JP, Posner KL, et al. Cervical spinal cord, root, and bony spine injuries: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2011;114:782–95. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182104859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Skordilis M, Rich N, Viloria A, et al. Processed electroencephalogram response of patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy: a pilot study. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:909–12. 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zheng JX. Bilateral bispectral index monitoring to detect cerebral hypoperfusion during carotid endarterectomy under general anesthesia. Saudi J Anaesth 2018;12:125–7. 10.4103/sja.SJA_347_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russell IF. The Narcotrend 'depth of anaesthesia' monitor cannot reliably detect consciousness during general anaesthesia: an investigation using the isolated forearm technique. Br J Anaesth 2006;96:346–52. 10.1093/bja/ael017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tunstall ME. Detecting wakefulness during general anaesthesia for caesarean section. BMJ 1977;1:1321 10.1136/bmj.1.6072.1321-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Millar K, Watkinson N. Recognition of words presented during general anaesthesia. Ergonomics 1983;26:585–94. 10.1080/00140138308963377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schneider G, Kochs EF, Horn B, et al. Narcotrend does not adequately detect the transition between awareness and unconsciousness in surgical patients. Anesthesiology 2004;101:1105–11. 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kreuer S, Biedler A, Larsen R, et al. Narcotrend monitoring allows faster emergence and a reduction of drug consumption in propofol-remifentanil anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2003;99:34–41. 10.1097/00000542-200307000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kreuer S, Bruhn J, Stracke C, et al. Narcotrend or bispectral index monitoring during desflurane-remifentanil anesthesia: a comparison with a standard practice protocol. Anesth Analg 2005;101:427–34. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000157565.00359.E2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Amornyotin S, Chalayonnawin W, Kongphlay S, et al. Deep sedation for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a comparison between clinical assessment and NarcotrendTM monitoring. MDER 2011;4:43–9. 10.2147/MDER.S17236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sponholz C, Schuwirth C, Koenig L, et al. Intraoperative reduction of vasopressors using processed electroencephalographic monitoring in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Monit Comput 2019;7 10.1007/s10877-019-00284-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dennhardt N, Boethig D, Beck C, et al. Optimization of initial propofol bolus dose for EEG Narcotrend Index-guided transition from sevoflurane induction to intravenous anesthesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2017;27:425–32. 10.1111/pan.13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weber F, Walhout LC, Escher JC, et al. The impact of Narcotrend™ EEG-guided propofol administration on the speed of recovery from pediatric procedural sedation-A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Anaesth 2018;28:443–9. 10.1111/pan.13365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McKay SD, Al-Omari A, Tomlinson LA, et al. Review of cervical spine anomalies in genetic syndromes. Spine 2012;37:E269–77. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823b3ded [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tauchi R, Imagama S, Ito Z, et al. Complications and outcomes of posterior fusion in children with atlantoaxial instability. Eur Spine J 2012;21:1346–52. 10.1007/s00586-011-2083-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kubica-Cielińska A, Zielińska M. The use of nalbuphine in paediatric anaesthesia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 2015;47:252–6. 10.5603/AIT.2015.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rinösl H, Fleck T, Dworschak M, et al. Brain ischemia instantaneously tracked by the narcotrend EEG device. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2013;27:e13–14. 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Niu K, Guo C, Han C, et al. Equipment failure of intravenous syringe pump detected by increase in Narcotrend stage: a case report. Medicine 2018;97:e13174 10.1097/MD.0000000000013174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]