Abstract

We present a case study of a 61-year-old Vietnamese woman who presents with features of dermatomyositis (DM), including Gottron’s papules, heliotrope rash, cutaneous ulcers, generalised weakness and pain, and weight loss with normal levels of creatine kinase (CK). She demonstrated features of interstitial lung disease and subsequently tested positive for anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 and anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 activating enzyme antibodies, which belong to a DM subtype known as clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis and do not present with raised CK. She received standard treatment for DM, including oral prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, mycopheonlate and topical betamethasone. The treatment successfully reversed skin changes; however, the patient remained generally weak and unable to carry out her activities of daily living.

Keywords: general practice / family medicine, rheumatology, dermatology

Background

There is currently limited evidence on the mode of presentation, serological investigation and optimal treatment of newly described forms of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), which is associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD). This case study outlines the presentation, diagnosis and subsequent management of a patient admitted under the Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology at Princess Alexandra Hospital.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old Vietnamese woman presented in February 2019 with a 4-month history of a violaceous, erythematous rash with scaling on her arms, thighs, scalp and face, weight loss from 54 kg down to 38 kg, and associated arthralgias and weakness resulting in falls and need for a walker to mobilise. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (875 mg/125 mg) by her general practitioner 3 weeks prior to presentation for skin infections due to persistent scratching. There was no history of any fevers, rigours, travel or sick contacts. There was a vague history of exertional dyspnoea but no chest pains, palpitations or other symptoms suggestive of cardiac failure.

Her medical history was significant for a 16-year history of Graves disease (requiring a total thyroidectomy in 2004), diverticulosis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia with chronic back pain and depression. There was no known history of malignancy. Her medications on admission included amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (875 mg/125 mg), thyroxine 100 µg daily, amitriptyline 35 mg at night, paracetamol with codeine (500 mg/30 mg) one tablet three times a day as needed and fenofibrate 145 mg/day (patient self-commenced 1 week prior to admission following it being prescribed 1 year ago but never commenced). There was no known statin use. She did not smoke, drank minimal alcohol, lived with her two daughters, and prior to onset of her illness was independent with all activities and instrumental activities of daily living.

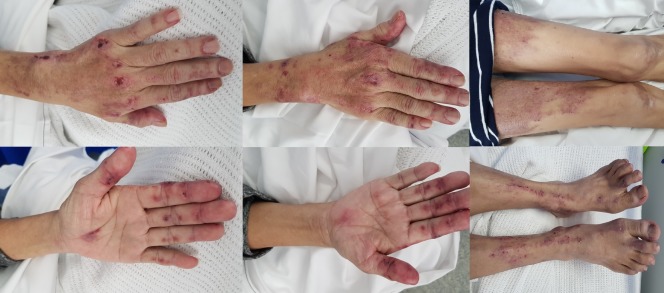

On examination, all her vital observations were normal. She appeared severely malnourished and weighed 38 kg. She had a diffuse pruritic rash over her upper limbs and lower limbs, with ulcers and Gottron’s papules over her hands, which were painful to touch (figure 1). There were ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold erythema, but no sclerodactyly. There was a heliotrope rash with periorbital swelling in addition to a diffuse erythematous rash with violaceous patches with overlying scale and hyperpigmentation. There was diffuse tenderness over most of her joints but no joint effusions. She had generalised weakness in all limbs with significant upper and lower limb muscle wasting and normal tone and reflexes. Bi-basal fine crackles were heard on lung auscultation but heart sounds were dual without murmurs. The abdominal examination was normal.

Figure 1.

Dermatological changes seen in this patient’s hands and legs (including pruritic rash, ulcers and Gottron’s papules over hands).

Investigations

Her full blood count and biochemistry, including serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate, were normal. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 84 mm/hour (<20 mm/hour) and C-reactive protein mildly elevated at 22 mg/L (<5 mg/L). Serum creatine kinase (CK) was normal. C3 was decreased at 0.84 g/L (0.9–1.8 g/L) but C4 was normal at 0.19 g/L (0.1–0.4 g/L). Serum electrophoresis showed an IgG of 25 g/L (6.0–16.0 g/L), IgA of 5.1 g/L (0.8–3.0 g/L) and IgM of 1.6 g/L (0.4–2.5 g/L). Tests for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) (performed with 1:40 HEp-2 cell dilution), Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. Urinary protein/creatinine and albumin/creatinine ratios were within the normal range. Thyroid function tests initially showed a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 0.5 mU/L (0.3–4.5 mU/L) and fT4 of 24 pmol/L (7.0–17 pmol/L), but these normalised 2 months after her thyroxine dose was reduced to 75 mcg daily.

Skin biopsies (with immunofluorescence testing) of the rashes over her thigh, chest and hand were consistent with mild lichenoid dermatitis. Differentials included dermatomyositis (DM) and systemic lupus erythematosus.

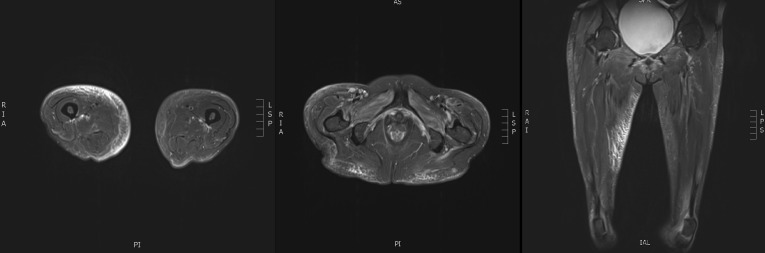

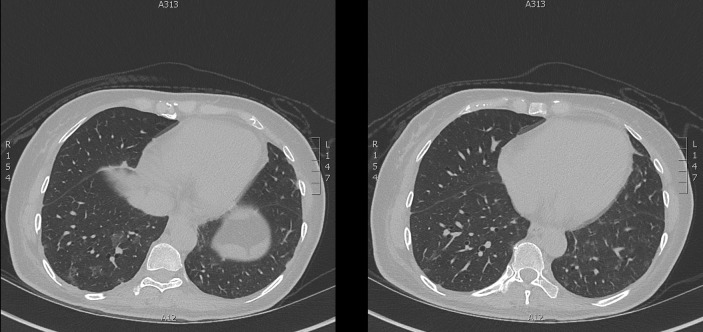

An MRI scan of her muscles showed patchy multifocal myositis involving several muscle groups, predominantly the right gluteus medius, right quadratus internus, right adductor muscles and right iliac psoas (figure 2). A high-resolution CT chest (HRCT) scan showed bilateral peribronchovascular and peripheral areas of ground-glass opacification with small areas of subpleural reticulation and parenchymal bands, all suggestive of ILD (figure 3). Respiratory function tests (RFTs) showed decreased diffusing lung capacity of 43% predicted value (pred.) and residual volume of 67% pred. (1.06 L), with total lung capacity of 86% pred. (2.97 L), forced expiratory ventilation in 1 s (FEV1) of 80% of pred. (1.36 L), forced vital capacity (FVC) of 85% pred. (1.75 L) and FEV1/FVC ratio of 78%. Echocardiogram showed normal right ventricular systolic pressure with left ventricular ejection fraction of 50%–55% and no valvular abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Areas of myositis observed on soft tissue MRI of lower limbs.

Figure 3.

Ground-glass changes at bases of lungs on patient’s high-resolution CT chest.

A muscle biopsy was considered but not performed due to the anticipated lack of further diagnostic utility given myositis on MRI, suggestive skin biopsy findings, ILD on HRCT and RFTs, clinical signs for DM and subsequent positivity for anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) and anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 activating enzyme (SAE1) antibodies.

In screening for occult malignancies, the only significant finding on CT scans of her chest, abdomen and pelvis and transvaginal ultrasound was a short segment of circumferential thickening within the caecum and proximal ascending colon. Colonoscopy and upper endoscopy showed no malignancy.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the skin abnormalities included Sweet’s syndrome, drug-related eruption, cutaneous systemic lupus erythematosus and undifferentiated connective tissue disease.

At day 15 of admission, results of an extended spectrum of serological tests were received, which disclosed the presence of anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies.

Treatment

Based on a provisional diagnosis of DM, the patient was commenced on prednisolone 40 mg/day (1 mg/kg) and topical betamethasone 0.05% two times per day. Her inflammatory markers remain elevated and because of recurrent skin ulcers, mycophenolate (MMF) 500 mg/day was commenced. Generalised musculoskeletal pain was treated with controlled release oxycodone and naloxone 5 mg/2.5 mg two times per day, paracetamol 1 g three times per day and oxycodone 2.5–5 mg every 4 hours as needed. Fenofibrate had been stopped immediately on presentation. At day 21 of admission, she was discharged with dermatology, rheumatology and respiratory clinic follow-up.

On second presentation 1 month later, the patient had deteriorated further with ongoing weight loss, increasing frequency of falls, rising inflammatory markers and worsening of pain associated to cutaneous ulcers and back pain. She was treated with intravenous and oral antibiotics (flucloxacillin). Subsequently, her MMF dose was increased to 750 mg two times per day, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 200 mg/day was commenced and her prednisolone was weaned down to 20 mg/day. Control of her pain required titration of tapentadol to 100 mg two times per day and duloxetine 60 mg/day. She was discharged after 11 days with community follow-up by the palliative care service to manage persisting pain.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s prognosis and level of functioning remain poor due to ongoing weakness, wasting and pain, which have proven refractory to current immunosuppressive treatment, despite some improvement in her skin disease. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) had been considered; however, the patient declined. Other treatment options such as rituximab and cyclophosphamide were not considered appropriate given her rapid deterioration, stable ILD and the development of infectious complications, including osteomyelitis in her right elbow, left distal third metacarpal and base of proximal phalanx of left middle finger related to infected skin ulcers.

Discussion

Anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies associated with DM have only been identified relatively recently.1 2 Without appropriate DM-specific antibody screening, it is easy to overlook the correct diagnosis in cases that do not demonstrate elevated CK levels.

In 2005, Sato et al identified a 140 kDa protein detected in Japanese patients with DM and CADM.1 This specific protein was found to be associated with CADM and RPILD and was named anti-MDA5 antibody due to its reactivity against the MDA5 protein expressed in cells transfected with full-length MDA5 complementary DNA.1 2 In addition, the MDA5 protein acts as an RNA sensor with antiviral activity against picornaviruses, such as coxsackievirus.3–5 Fiorentino et al subsequently recognised that autoimmunity to MDA5 was linked to cutaneous ulcers and RPILD, lending credence to the theory that MDA5 antibody associated DM is an autoimmune response to viruses.2 3 6

Between 4.7% and 13.1% of cases of DM and 10.0% to 8.8% of cases of CADM may be associated with the anti-MDA5 antibody.7 Significant racial and regional differences in the clinical manifestations of DM associated with anti-MDA5 antibodies may be attributed to genetic differences such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1 gene polymorphisms.8 For instance, anti-MDA5 antibody positivity in Japan is seen in 80% of cases of CADM, 90% of cases of ILD and 70% of cases of RPILD, and is associated with a mortality rate of 30%–50%.8 In contrast, in East Asia, while the prevalence of RPILD and the mortality rate for anti-MDA5 antibody associated DM are similar to that seen in Japan, the antibody is seen in less than 40% of cases of CADM.8 In North America, the antibody prevalence in cases of CADM is 50%, and in cases of RPILD only 20%.8

In 2007, the anti-SAE1 antibody was discovered by Betteridge et al,9 this being a myosin-specific antibody, which only occurs in 1.5%–8.0% of cases of DM.10 SAE1 is a protein involved in post-translational modification of protein kinases and transcription factors, which may have a role in the development of inflammatory diseases, including primary biliary cirrhosis, which is commonly associated with DM.9 11–13 This antibody has a variable frequency globally, being detected in 3% of Chinese cases of DM, 1.8% of Japanese patients, 8% of British Caucasian patients and 6.7% of Greek and Italian patients.14–18 It has a strong association with HLA-DQB1*03, HLA-DRB1*04 and HLA-DQA1*03 haplotypes.16

This case study highlights unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by atypical presentations of DM. Over 90% of DM cases present with myopathic disease with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness and raised CK.19 20 In contrast, MDA5 antibody associated DM presents with the CADM phenotype in 80% of cases where muscle weakness and elevated CK levels are not seen.21 Our patient uniquely did not have raised CK but was diffusely weak, and otherwise had stereotypical skin features of DM. Anti-MDA5 antibodies are also associated with skin features (70% of cases), including distinct punched out cutaneous ulcers, Gottron’s papules (53.5%), Gottron’s sign (69.6%), RPILD (20%–90%), arthritis (31.2%), alopecia (34%) and heliotrope rash.2 21 The disease commonly causes death within the first 6 months of diagnosis, due to respiratory failure from RPILD.2 21 22 Only one case study with anti-MDA5 antibody positivity had concurrent cardiomyopathy, although DM is commonly associated with cardiac complications such as myocarditis, ischaemia, arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies.23–25

Anti-SAE1-antibodies are also associated with CADM and skin features (80% of cases) with Gottron’s papules (64%), Gottron’s sign (64%), heliotrope rash (82%) and a distinct diffuse pruritic erythema, which is more common in Asians (50% of cases) than Caucasians (7.3%).9 14 26 Anti-SAE1 antibodies are also associated with dysphagia (78%), higher rates of malignancy compared with other forms of DM (18.7% to 57% vs 9.4%) and less severe forms of ILD.9 15 26 27 There are no known reports of cardiomyopathy associated with anti-SAE1 antibodies.

In our patient, the diagnosis of DM was strongly suspected on the basis of clinical features, including Gottron’s papules, skin rashes, cutaneous ulcers and weakness. However, similar to many other rheumatological conditions, the presence of specific antibodies can engender specific clinical features, which guide treatment options. However, only 50%–70% of cases of DM and CADM have been shown on past studies to have identifiable myositis-specific antibodies, including anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies, resulting in many seronegative cases.21 28 29 In our patient, anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies were only detected at a later stage of illness, due to logistical delays in laboratory testing (including batch collection and the myositis blot testing itself).

The treatment of DM associated with anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies is similar to that of other variants of DM, with systemic corticosteroids being first line agents, and other drugs being used according to response to steroids and the predominance of cutaneous, respiratory or muscle symptoms. Steroids improve muscle function (with 25% of patients regaining full strength) but do not improve survival.30 31 Cutaneous features of DM are typically treated with topical steroids, usually with good efficacy.32 MMF is useful in refractory disease, as exemplified by our patient, as well as in patients with ILD or significant skin disease, with around 83% improvement in skin features, combined with decrease in CK levels (when elevated) and improved muscle strength after 22 months.33–36 MMF also acts as a steroid-sparing agent, allowing average maintenance dose of prednisone being weaned from 13.7 to 8.5 mg/day.34 Adjunctive treatment with HCQ has no effect on muscle disease and is only effective for skin disease, with a 75% response rate.37–40 Because of its expense and difficulty in sourcing, IVIG is reserved for DM associated with life-threatening weakness or severe dysphagia, although it may have some effect on skin disease.41–46 Unfortunately, in our patient, only her skin disease partially responded to multiple medications. Rituximab has been utilised in refractory and progressive ILD related to anti-MDA5 antibody positive DM.47 This was not considered in our case given the stability of the ILD and development of infectious complications, including osteomyelitis.

Patient’s perspective.

I was very surprised to be diagnosed with such a rare condition. I had so many tests and did not expect to have so many specialist areas involved. I did feel like a laboratory rat after all the skin biopsies, scans, endoscopies, colonoscopies, blood tests and medical reviews. However, I was lucky to be supported by the hospital, though there are still a lot of difficulties carrying out daily activities of living.

Learning points.

Dermatomyositis (DM) can still present with significant muscular weakness and wasting, alongside typical skin features, despite no elevation in levels of creatine kinase. DM with either anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) or anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SAE1) antibodies often is amyopathic.

Although positivity for DM-related antibodies yields a more specific diagnosis, management is ultimately guided by clinical features.

Anti-MDA5 antibodies are strongly associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and cutaneous ulcers, as opposed to solid tumour malignancies. Anti-SAE1 antibodies are associated with diffuse pruritic rash, malignancies and less severe ILD.

Response to treatment can be limited and protracted, despite numerous immunosuppressive options of corticosteroids and other disease-modifying agents.

Footnotes

Contributors: Supervised by SM, HB and IAS. Patient under the care of SM and HB. Report written by CK, SM, HB and IAS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Next of kin consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kD polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1571–6. 10.1002/art.21023 10.1002/art.21023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, et al. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:25–34. 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sato S, Hoshino K, Satoh T, et al. Rna helicase encoded by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is a major autoantigen in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: association with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2193–200. 10.1002/art.24621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saito T, Hirai R, Loo Y-M, et al. Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:582–7. 10.1073/pnas.0606699104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christensen ML, Pachman LM, Schneiderman R, et al. Prevalence of Coxsackie B virus antibodies in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1365–70. 10.1002/art.1780291109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 2006;441:101–5. 10.1038/nature04734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borges IBP, Silva MG, Shinjo SK. Prevalence and reactivity of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA-5) autoantibody in Brazilian patients with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol 2018;93:517–23. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Endo Y, Koga T, Ishida M, et al. Recurrence of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis after long-term remission. Medicine 2018;97:e11024 10.1097/MD.0000000000011024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Betteridge Z, Gunawardena H, North J, et al. Identification of a novel autoantibody directed against small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme in dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3132–7. 10.1002/art.22862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McHugh NJ, Tansley SL, myositis Ain. Autoantibodies in myositis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:290–302. 10.1038/nrrheum.2018.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dohmen RJ. Sumo protein modification. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004;1695:113–31. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pichler A, Melchior F. Ubiquitin-Related modifier SUMO1 and nucleocytoplasmic transport. Traffic 2002;3:381–7. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Janka C, Selmi C, Gershwin ME, et al. Small ubiquitin-related modifiers: a novel and independent class of autoantigens in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2005;41:609–16. 10.1002/hep.20619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ge Y, Lu X, Shu X, et al. Clinical characteristics of anti-SAE antibodies in Chinese patients with dermatomyositis in comparison with different patient cohorts. Sci Rep 2017;7:188 10.1038/s41598-017-00240-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Low prevalence of anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme antibodies in dermatomyositis patients. Autoimmunity 2013;46:279–84. 10.3109/08916934.2012.755958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Betteridge ZE, Gunawardena H, Chinoy H, et al. Clinical and human leucocyte antigen class II haplotype associations of autoantibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier enzyme, a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen target, in UK Caucasian adult-onset myositis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1621–5. 10.1136/ard.2008.097162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tarricone E, Ghirardello A, Rampudda M, et al. Anti-SAE antibodies in autoimmune myositis: identification by unlabelled protein immunoprecipitation in an Italian patient cohort. J Immunol Methods 2012;384:128–34. 10.1016/j.jim.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zampeli E, Venetsanopoulou A, Argyropoulou OD, et al. Myositis autoantibody profiles and their clinical associations in Greek patients with inflammatory myopathies. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:125–32. 10.1007/s10067-018-4267-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, et al. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1997;84:223–43. 10.1006/clin.1997.4412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bohan A, Peter JB, Bowman RL, et al. A computer-assisted analysis of 153 patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Medicine 1977;56:255–86. 10.1097/00005792-197707000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chaisson NF, Paik J, Orbai A-M, et al. A novel dermato-pulmonary syndrome associated with MDA-5 antibodies: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2012;91:220–8. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182606f0b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurtzman DJB, Vleugels RA. Anti-Melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5 (MDA5) dermatomyositis: a Concise review with an emphasis on distinctive clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:776–85. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundberg IE. The heart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Rheumatology 2006;45:iv18–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tisseverasinghe A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA. Arterial events in persons with dermatomyositis and polymyositis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1943–6. 10.3899/jrheum.090061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibáñez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:1097–102. 10.1111/jdv.12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jia E, Wei J, Geng H, et al. Diffuse pruritic erythema as a clinical manifestation in anti-SAE antibody-associated dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:2189–93. 10.1007/s10067-019-04562-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barnes BE, Mawr B. Dermatomyositis and malignancy. A review of the literature. Ann Intern Med 1976;84:68–76. 10.7326/0003-4819-84-1-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mammen AL. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis: clinical presentation, autoantibodies, and pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1184:134–53. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gunawardena H, Betteridge ZE, McHugh NJ. Myositis-Specific autoantibodies: their clinical and pathogenic significance in disease expression. Rheumatology 2009;48:607–12. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carpenter JR, Bunch TW, Engel AG, et al. Survival in polymyositis: corticosteroids and risk factors. J Rheumatol 1977;4:207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, et al. Guidelines of care for dermatomyositis. American Academy of dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:824–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Quain RD, Werth VP. Management of cutaneous dermatomyositis: current therapeutic options. Am J Clin Dermatol 2006;7:341 10.2165/00128071-200607060-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneider C, Gold R, Schäfers M, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in the therapy of polymyositis associated with a polyautoimmune syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2002;25:286–8. 10.1002/mus.10026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pisoni CN, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment in resistant myositis. Rheumatology 2007;46:516–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rowin J, Amato AA, Deisher N, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in dermatomyositis: is it safe? Neurology 2006;66:1245–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000208416.32471.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Majithia V, Harisdangkul V. Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept): an alternative therapy for autoimmune inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatology 2005;44:386–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. James WD, Dawson N, Rodman OG. The treatment of dermatomyositis with hydroxchloroquine. J Rheumatol 1985;12:1214–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cosnes A, Amaudric F, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis without muscle weakness. long-term follow-up of 12 patients without systemic corticosteroids. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:1381–5. 10.1001/archderm.131.12.1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dawkins MA, Jorizzo JL, Walker FO, et al. Dermatomyositis: a dermatology-based case series. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:397–404. 10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70496-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olson NY, Lindsley CB. Adjunctive use of hydroxychloroquine in childhood dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 1989;16:1545–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dalakas MC, Illa I, Dambrosia JM, et al. A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1993–2000. 10.1056/NEJM199312303292704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Peake MF, Perkins P, Elston DM, et al. Cutaneous ulcers of refractory adult dermatomyositis responsive to intravenous immunoglobulin. Cutis 1998;62:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Helmers SB, Dastmalchi M, Alexanderson H, et al. Limited effects of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment on molecular expression in muscle tissue of patients with inflammatory myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1276–83. 10.1136/ard.2006.058644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sadayama T, Miyagawa S, Shirai T. Low-Dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for intractable dermatomyositis skin lesions. J Dermatol 1999;26:457–9. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Femia AN, Eastham AB, Lam C, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for refractory cutaneous dermatomyositis: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:654–7. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bounfour T, Bouaziz J-D, Bézier M, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulins for the treatment of dermatomyositis skin lesions without muscle disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:1150–7. 10.1111/jdv.12223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. So H, Wong VTL, Lao VWN, et al. Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:1983–9. 10.1007/s10067-018-4122-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]