Abstract

Binasal hemianopia is a rare visual field defect. A teenage girl presented with blurred vision and persistent headaches following a minor head injury. The ocular examination was normal except for a binasal hemianopia, and subsequent neuroimaging was also unremarkable. Her older sister was found to have the same visual field defect, also with normal neuroimaging. This represents the first reported case of binasal hemianopia found in siblings. Given that no neurological or ocular cause was identified in either sister, this supports the theory of an unknown congenital aetiology.

Keywords: ophthalmology, visual pathway

Background

True, binasal (heteronymous) visual field defects are rarely seen. There are several reports of incomplete binasal visual hemianopia.1 2 However, only one report describes a complete binasal hemianopia in two unrelated females.3 This is therefore the first reported case of binasal hemianopia in siblings, providing further evidence to suggest an unknown congenital cause.

Case presentation

A 16-year-old female patient (sister 1), with no significant medical or ophthalmic history, presented to the emergency department with intermittently blurred vision, headaches and nausea. One day, she had tripped and fallen, hitting her forehead on the curb of a road without loss of consciousness. A CT head scan was normal. However, her headaches and visual symptoms persisted and so an optometric assessment was arranged. Visual field testing demonstrated a repeatable, binasal hemianopia. She was referred for an ophthalmology opinion.

Subsequently her older sister (Sister 2), aged 18, attended the same optometrist for a routine examination. She had no visual symptoms. Visual field testing showed an almost identical binasal hemianopia. She was also referred to the same department of ophthalmology.

Investigations

Sister 1

She did not have a refractive error, and her unaided vision was normal, as were the pupil reactions. The anterior segment examination was unremarkable. The intraocular pressures were 14 mm Hg (right) eye and 16 mm Hg (left eye). Funduscopy showed no abnormality and both optic discs appeared healthy. In particular, the optic discs were not tilted, anomalous or hypoplastic and showed no clinical evidence of disc drusen (figure 1). Automated perimetry confirmed the presence of a complete binasal hemianopia (figure 2), almost perfectly respecting the vertical midline. A brain MRI scan was unremarkable, showing a normal pituitary gland and optic nerves. Blood tests were also normal showing satisfactory inflammatory markers, glucose, thyroid function tests, bone profile, liver function, renal function and full blood count.

Figure 1.

Optic disc photograph for sister 1.

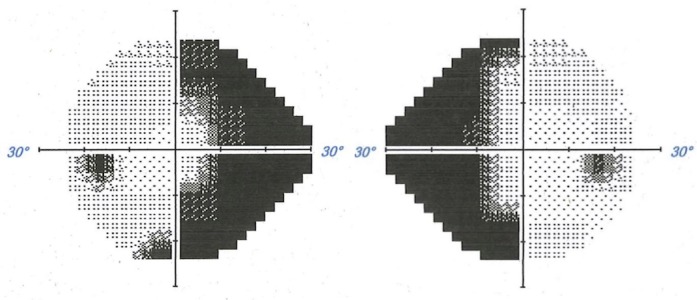

Figure 2.

Automated perimetry for sister 1.

Sister 2

A detailed neurological and ophthalmic examination was also normal apart from an identical visual field defect, also confirmed by automated perimetry (figure 3). Unaided visual acuity was normal and she had no significant refractive error. The optic discs did not show any abnormality (figure 4). A brain MRI scan also showed no abnormality.

Figure 3.

Automated perimetry for sister 2.

Figure 4.

Optic disc photograph for sister 2.

Differential diagnosis

Visual field defects can occur due to either ocular or neurological pathologies. The most common ocular cause of a visual field defect is glaucoma due to damage to the retinal nerve fibre layer, but other ocular causes include optic nerve head pathology, and retinal pathologies such as detachment or retinal vascular disease. Neurological causes of visual field defects include lesions to the optic nerve, optic chiasm, optic radiation or occipital cortex, and the resulting visual field defect can be explained by the location of lesions. Homonymous hemianopias occur when pathologies in the visual pathway are present distal to the optic chiasm, whereas heteronymous hemianopias are due to pathology at the optic chiasm, such as pituitary gland enlargement. Pressure on the medial aspect of the chiasm causes a bitemporal visual defect due to the decussation of medial fibres. In contrast, a binasal hemianopia occurs when nerve fibres at both lateral aspects of the chiasm are affected. This scenario is exceedingly rare.

Binasal hemianopia has been described in association with bilateral internal carotid artery atherosclerosis,4 a distended third ventricle in internal hydrocephalus,5 brain tumour,6 empty sella syndrome,7 8 chronic raised intracranial pressure,9 olfactory groove meningioma,5 spontaneous intracranial hypertension10 and bilateral neurosyphilis.9 A variety of ocular causes have been described including glaucoma, optic nerve drusen, ischaemic optic neuropathy, congenital optic nerve pits, retinitis pigmentosa2 and keratoconus.1

Treatment

Sister 1

The headaches persisted, and so, a general paediatrics review was arranged. Migraine was suspected, and a trial of Pizotifen was commenced. Her headaches and visual symptoms of blurred vision gradually resolved.

Sister 2

She remained asymptomatic, and so, no treatment was required.

Outcome and follow-up

Both sisters underwent repeat visual field testing, an electrodiagnostic assessment, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans. The findings are outlined below.

Humphrey visual fields on both sisters confirmed repeatable symmetrical binasal hemianopic field loss. Binocular visual field testing (ie, a field test completed using both eyes simultaneously) showed full binocular fields in both sisters. Reliability indices for all tests were good.

Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) were recorded using the Apkarian technique, using both full and half-field stimulation. In both sisters, there was a delay of the ipsilateral response to flash stimulation and reduced responses on stimulating the nasal hemifields of either eye. The VEPs were otherwise normal in terms of amplitude and peak time to flash and pattern stimulation.

OCT scanning confirmed that the retina and optic discs were healthy. The retinal nerve fibre layer was unremarkable, and the thickness of the retinal ganglion cell layer was normal in both eyes of both sisters.

Discussion

In this case report, we present two sisters with binasal hemianopia with no identifiable intraocular or cerebral cause. Both individuals were previously unaware of their visual field defects, and neither complain of any persisting visual symptoms. Given the completely normal ocular appearances, normal retinal OCT and normal visual acuities, we do not believe a retinal pathology could explain the stark binasal field detects which almost completely respect the vertical meridian. Healthy optic nerve appearances and an intact nerve fibre layer also make optic neuropathy unlikely. Furthermore, normal neuroimaging and an otherwise normal neurological examination make ischaemia, atrophy or mass effect unlikely causes of such a defect.

Consequently, the exact aetiology of the observed visual field defect in our patients is medically unexplained. This category of field loss is sometimes termed ‘functional’; this group may include conscious malingering or deception. However, we believe that the results of the hemifield VEP tests, and the full binocular visual field test results, makes this possibility unlikely in our patients. It is not possible to consciously influence the result of a hemifield VEP test, and if a test subject is malingering, then an abnormal binocular field result would be expected. Furthermore, there was no apparent secondary gain from the visual field defects, and in case 1, the field defect was identified as an incidental finding following a head injury, again making this possibility unlikely.

Since neither the retinal nerve fibre layer or retinal ganglion cell thickness is affected, then this would suggest that the abnormality lies posterior to the chiasm. It is plausible that the abnormality is within the temporal sides of the lateral geniculate nucleus bilaterally. The fact that the field defects almost completely respect the vertical midline strongly suggests an underlying neurological cause.

Our patients are related, unaware of any visual defect and did not report any significant changes to their vision. In the circumstances, it seems reasonable to assume a congenital aetiology. Proving that these defects were present from birth is not possible. However, given that patients with congenital homonymous hemianopias are often asymptomatic, it is conceivable that the sisters’ field defects are longstanding.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of complete binasal hemianopia in siblings with no identifiable cause. It is only the second ever report of complete binasal hemianopia. In 2014, Bryan et al described two unrelated females with the same binasal hemianopic visual field defect, picked up on routine eye testing.3 Both were asymptomatic and had otherwise normal ocular examinations and unremarkable neuroimaging, similar to our patients. The authors postulated a congenital temporal retinal axon mis-sorting syndrome or, in the absence of optic atrophy, a pathology located along the postgeniculate visual pathways. This could conceivably disrupt cortical representation of the retinal ganglion cells from the temporal half of each retina, resulting in a binasal hemianopia without any identifiable structural abnormality. Although currently medically unexplained, our findings of binasal hemianopia in sisters therefore support this theory of a congenital axonal mis-sorting syndrome. Considering all four documented cases were incidental findings, we propose that a small proportion of the population may live their lives completely unaware of such a visual field defect, contributing to its rarity.

Learning points.

Complete binasal hemianopias, in contrast to bitemporal hemianopias, are extremely rare.

Functional visual field loss (including malingering) should always be considered in medically unexplained cases.

True binasal hemianopia may have a congenital aetiology.

Our patients were completely symptom free. It is therefore conceivable that there is a percentage of the population with congenital binasal hemianopias who are completely unaware of their condition, contributing to its rarity.

In the absence of identifiable neurological or ocular pathology, a retinal axon mis-sorting syndrome as previously postulated,3 or a postchiasmal lesion in both temporal sides of the lateral geniculate nuclei might be causing such a visual field defect. This requires additional study to confirm.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS: planned, researched and wrote the article; GM: edited the manuscript; PG: provided neurophysiology data and advice.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ashwin PT, Quinlan M. Interpreting binasal hemianopia: the importance of ocular examination. Eur J Intern Med 2006;17:144–5. 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salinas-Garcia RF, Smith JL. Binasal hemianopia. Surg Neurol 1978;10:187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bryan BT, Pomeranz HD, Smith KH. Complete binasal hemianopia. Proc 2014;27:356–8. 10.1080/08998280.2014.11929158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamann S, Obaid HG, Celiz PL. Binasal hemianopia due to bilateral internal carotid artery atherosclerosis. Acta Ophthalmol 2015;93:486–7. 10.1111/aos.12565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Connell JEA, Boulay EPGHD, Du Boulay EP. Binasal hemianopia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1973;36:697–709. 10.1136/jnnp.36.5.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cushing H, Walker C. Distortions of the visual fields in cases of brain tumor (third paper): binasal hemianopsia. Arch Ophthalmol 1912;41:559–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charteris DG, Cullen JF. Binasal field defects in primary empty sella syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol 1996;16:110–4. 10.1097/00041327-199606000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanawa K, Oshitari T, Nagata H, et al. Binasal visual field defects in cases of empty sella syndrome. Chiba Med J 2007;83:177–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pringle E, Bingham J, Graham E. Progressive binasal hemianopia. The Lancet 2004;363:1606 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16204-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horton JC, Fishman RA. Neurovisual findings in the syndrome of spontaneous intracranial hypotension from dural cerebrospinal fluid leak. Ophthalmology 1994;101:244–51. 10.1016/S0161-6420(94)31340-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]