Abstract

Introduction

Minimally invasive gynecological surgery such as hysteroscopy has a small risk of complications. These include uterine perforation (with or without adjacent pelvic organ lesion), bleeding and infection, and are more common in the presence of risk factors such as smoking, history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and endometriosis.

Case Presentation

A patient submitted to a diagnostic hysteroscopy with no immediate complications was admitted five days later to the emergency department in septic shock. The diagnosis of ruptured tubal abscess was made, requiring emergency laparotomy with sub-total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy. Despite multiple organ failure requiring admission to the intensive care unit, the patient made a full recovery.

Conclusion

Ascending infection can be a life-threatening complication of hysteroscopy, even in the absence of previously known risk factors.

Keywords: Hysteroscopy, Complications, Risk factors, Multiple organ failure, Sepsis

Highlights

-

•

Septic shock can be a serious complication of office hysteroscopy.

-

•

Ascending infection can occur even with no prior history of sexual intercourse.

-

•

Patient awareness of alarm signs is key in preventing complications.

-

•

Prompt recognition and treatment of sepsis are needed to avoid morbidity.

1. Introduction

Any procedure requiring genito-urinary manipulation, such as hysteroscopy, hysterosonography or hysterosalpingography, carries a small risk of ascending infection. This complication is more likely in the presence of risk factors such as young age (under 25 years), active bacterial vaginosis, smoking, endometriosis, previous pelvic surgery, multiple sexual partners or recent change in partner. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is readily diagnosed when the patient presents with fever, pelvic tenderness and vaginal discharge. In the case presented here, however, the patient did not recognize or value the symptoms and presented late. Left untreated, PID can cause sepsis, and in this case, life-threatening complications such as respiratory distress, kidney failure and shock.

2. Case Presentation

This is a case of a 39-year-old woman (virgo intacta) with a history of heavy menstrual bleeding due to a submucous leiomyoma (FIGO type 2). She was submitted to an office hysteroscopy to evaluate the possibility of resection, but, due to active bleeding, a decision to postpone the procedure to allow for administration of GnRH agonists was made. A second-look office diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed the next month, uncomplicated except for a difficult entry into the uterine cavity. Upon inspection, the leiomyoma's dimensions were considered to be incompatible with resection in an out-patient setting. The procedure was stopped, and the patient was discharged home after administration of GnRH agonist (goserelin).

The following day, the patient was admitted to the emergency department complaining of mild pelvic pain and one episode of vomiting, with no fever or bleeding. Ultrasound revealed the previously described leiomyoma, with no free pelvic fluid. Blood analysis showed no leukocytosis and normal level of C-reactive protein. She was prescribed paracetamol and discharged. On the fifth day, the patient presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of intermittent fever, abdominal pain and distension. For the previous 2 days, she had had multiple episodes of vomiting, limiting her capacity for oral intake. Upon observation, she was found to be normotensive, with a normal heartrate and a tympanic temperature of 37,3 °C. The patient presented facial flushing with signs of distal hypoperfusion (cold extremities and mottled skin). Immediate care was provided, including 2 large-bore venous catheters with IV fluid infusion and administration of large-spectrum antibiotics. Blood and urine samples were collected for culture and laboratory evaluation.

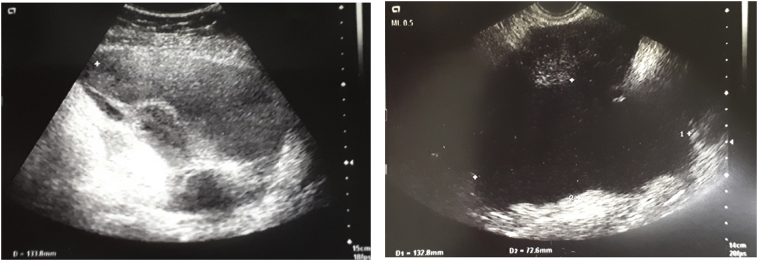

Vaginal ultrasound was performed to assess the pelvic cavity, documenting a normal-sized uterus with the previously described leiomyoma, with no signs of perforation and a virtual uterine cavity. Both adnexa were found to be in retro-uterine position, with limited mobility, suggesting previously undiagnosed endometriosis. A 13-centimeter fluid-filled cystic mass was found to occupy the lateral pelvic recess, consistent with a dilated right fallopian tube (Fig. 1). The left ovary and fallopian tube showed no abnormal findings. The ultrasound exam detected no free fluid in the pelvic cavity and was only mildly painful.

Fig. 1.

Vaginal ultrasound performed in the Emergency Department, showing a 13-centimeter anechoic mass adjacent to the ovary, suggestive of fallopian tube collection.

The patient was transferred to an intermediate care unit for monitoring. Blood analysis showed no signs of anemia but revealed elevated inflammatory parameters (leukocytosis of 16.630/mL, with 91% neutrophilia and C-reactive protein of 291 mg/dL, reference value <5 mg/dL). Acute renal lesion was diagnosed, based on anuric status despite high-volume crystalloid infusion and blood creatinine levels of 4.54 mg/dL. Arterial blood gasometry revealed primary metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.57, pCO2 43.4 mmHg, HCO3– 39.9 mEq/L, lactate 31 mmol/L). An abdominal X-ray (Fig. 2) showed distension of the stomach and small bowel, with no signs of pneumoperitoneum.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal X-ray showing distension of gastric chamber and initial portion of small bowel, with no signs of pneumoperitoneum.

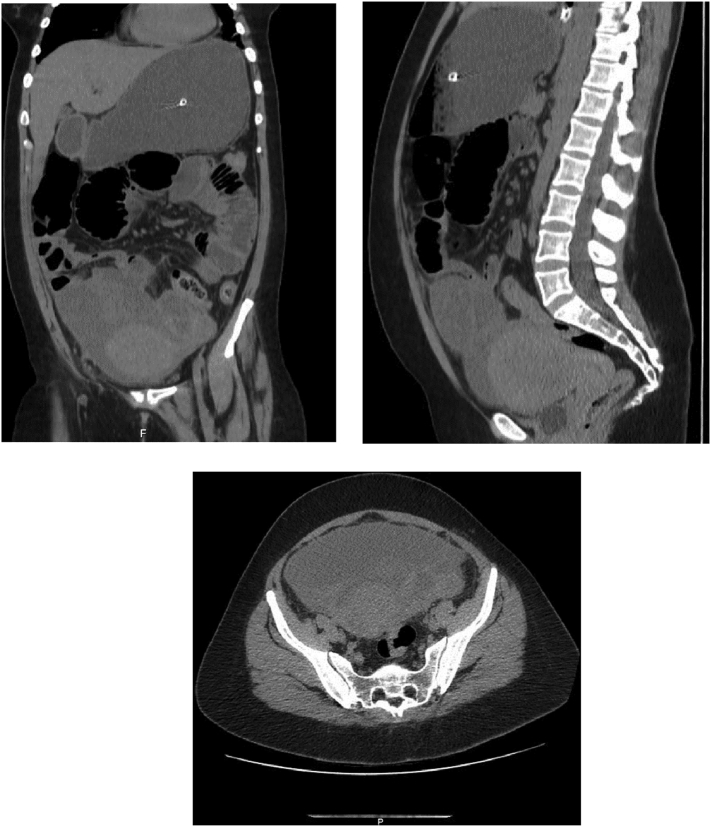

A computerized tomography (CT) scan was ordered and revealed “Marked distension of gastric chamber and proximal small bowel with no apparent extrinsic compression. Fluid collection in the pelvis, possibly cystic (CT scan with no intra-venous contrast). Normal-looking liver, biliary ducts, pancreas and kidneys. No sign of hydronephrosis” (Fig. 3). The surgical team decided to carry out an emergency exploratory laparotomy, which discovered a ruptured right fallopian tube with a significant volume of hemoperitoneum and generalized pelvic infection. Samples were collected for microbial analysis (which later revealed ampicillin-sensitive E. coli). Sub-total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy was performed and the patient was transferred to an intensive care unit for recovery. Stage 4 multiple organ failure followed the surgery, requiring mechanical ventilation and administration of vasopressors (dopamine) to ensure adequate hemodynamics.

Fig. 3.

Computerized tomography (CT) scan, highlighting the presence of a large pelvic mass involving the uterus and right fallopian tube.

Despite the hypoperfusion acute kidney injury (KDIGO 3), the patient responded well to fluid resuscitation and aminergic support. Full recovery of kidney function was achieved on the 5th day post-operatively. The patient was discharged home on the 12th day, with oral antibiotics.

On post-operative evaluation the patient was found to be well. Histological findings included acute salpingitis, peritonitis, endometriotic cysts in both ovaries and uterine leiomyomas. No features suggestive of uterine perforation were found in the specimen. These results were discussed with the patient, and she was counselled regarding initiation of hormone replacement therapy.

3. Discussion

Hemorrhage, pain and fluid absorption are widely recognized as the most frequent of hysteroscopic complications [1]. Infection occurs less frequently, with reported rates ranging from 0,2–1,5% [2]. This case illustrates the importance of ascending infection even in generally safe procedures. Being alert for and enquiring about known risk factors (smoking, history of PID, endometriosis, multiple partners or recent change in sexual partner) can help reduce the incidence of post-procedure infection. Currently, there is no evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis prior to transcervical procedures reduces infection rates [3]. Although vaginal disinfection is also not mandatory, it can still be performed electively at the surgeon's discretion or in the presence of vaginal discharge.

Communication with the patient is paramount in explaining the alarm signs that require medical assessment, such as fever, persistent pelvic pain or vomiting, heavy vaginal bleeding or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. Even though toxic shock syndrome presenting shortly after office hysteroscopy has been described [4], our patient had a late onset of septic shock. Had she presented earlier, timely intervention with antibiotic coverage would have likely prevented the need for invasive major surgery and ICU admission.

Once systemic infection is detected, prompt initiation of monitoring – continuous electrocardiography and pulse oximetry – is recommended. Septic shock or multiple organ failure should be treated as a medical emergency, requiring intensive care admission and organ-adjusted support [5]. Resuscitation measures should be expeditiously undertaken - IV fluid infusion and large-spectrum antibiotics, according to the institution's protocol. Blood and urine samples should be collected for culture, aimed at identifying the pathogen. In the presence of a large pelvic abscess, drainage is generally indicated – the choice of percutaneous or abdominal drainage, and laparotomic or laparoscopic surgical route, will be dictated by technique availability and surgeon experience.

Although rare, systemic infection arising from genito-urinary manipulation should not be neglected, as it can generate complications requiring surgical intervention and, in extreme cases, ICU admission.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Tânia Meneses contributed to data acquisition and analysis, and drafting of the manuscript.

Joana Faria contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, and manuscript revision.

Ana Teresa Martins contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, and manuscript revision.

Elsa Delgado contributed to data acquisition.

Maria do Carmo Silva contributed to manuscript revision.

All authors saw and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

Funding

No funding from an external source supported the publication of this case report.

Patient Consent

Obtained.

Provenance and Peer Review

This case report was peer reviewed.

References

- 1.McGurgan P.M., McIlwaine P. Complications of hysteroscopy and how to avoid them. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2015-10-01;29(7):982–993. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agostini A., Cravello L., Shojai R., Ronda I., Roger V., Blanc B. Postoperative Infection and surgical hysteroscopy. Fertil. Steril. 2001;77(4):766–768. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thinkhamrop J., Laopaiboon M., Lumbiganon P. Prophylactic antibiotics for transcervical intrauterine procedures. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005637.pub2. CD005637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhagat N., Karthikeyan A., Kalkur S. Toxic shock syndrome within 24 H of an office hysteroscopy. J. Midlife Health. 2017 Apr-Jun;8(2):92–94. doi: 10.4103/jmh.JMH_93_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger P, Roy A, Parillo JE, Severe sepsis and septic shock in Critical Care Medicine: Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult, 24, (323–345.e5).