Abstract

Compulsive eating characterizes many binge-related eating disorders, yet its neurobiological basis is poorly understood. The insular cortex subserves visceral-emotional functions, including taste processing, and is implicated in drug craving and relapse. Here, via optoinhibition, we implicate projections from the anterior insular cortex to the nucleus accumbens as modulating highly compulsive-like food self-administration behaviors that result from intermittent access to a palatable, high-sucrose diet. We identified compulsive-like eating behavior in female rats through progressive ratio schedule self-administration and punishment-resistant responding, food reward tolerance and escalation of intake through 24-h energy intake and fixed-ratio operant self-administration sessions, and withdrawal-like irritability through the bottle brush test. We also identified an endocrine profile of heightened GLP-1 and PP but lower ghrelin that differentiated rats with the most compulsive-like eating behavior. Measures of compulsive eating severity also directly correlated to leptin, body weight and adiposity. Collectively, this novel model of compulsive-like eating symptoms demonstrates adaptations in insula-ventral striatal circuitry and metabolic regulatory hormones that warrant further study.

Subject terms: Feeding behaviour, Motivation, Reward

Introduction

Compulsive eating is a promising construct [1–3], operationalized for human study in one form as the Yale Food Addiction Scale [4–6], which putatively resembles diagnostic features of substance use disorders. Proposed symptoms include food reward tolerance, escalation of intake, increased effort/time to obtain food, loss of control over intake, eating despite (risk of) adverse consequences, and negative emotional symptoms upon abstinence, with food used to relieve negative mood (i.e., negative reinforcement) [3, 7, 8]. By this definition, compulsive eating is most prevalent in binge-related eating disorders [4, 6], which afflict ~8–10% of Western women [9, 10]. Compulsive eating is also prevalent in a subset of overweight people (~33%) [6]. As most men and women are overweight [11], tens of millions of Americans may engage in compulsive eating. Alas, the neurobiological bases of compulsive eating are poorly understood, and, accordingly, treatments are limited.

The insular cortex represents homeostatically relevant bodily states [12, 13] that influence behavior as “somatic markers” [12]. Increased insula responses to palatable foods or their associated cues are seen in YFAS-defined food addiction, obesity, and binge-related eating disorders [14, 15]. Greater insula responses predict fat gain [16] and craving [17, 18], and show high connectivity to the ventral striatum [19, 20], which subserves food reward and reinforcement [21–23]. Independently, the insula is implicated in compulsive substance use [24], subserving salient visceroemotional drug withdrawal, craving, and use states. In rodents, glutamatergic projections from the anterior insular cortex (AIC) to the nucleus accumbens (Acb) promote alcohol drinking despite aversive conflict; optoinhibition of this projection reduced compulsive-like quinine- and punishment-resistant-drinking, but not regular drinking [25]. Disturbed insula-striatal functional connectivity has been reported in eating pathologies through human neuroimaging studies; particularly hypoactivation of both regions have been observed in patients with anorexia [26, 27]. Collectively the reported roles of this circuitry in both animal models of compulsive-like drinking and human subjects with disordered eating leads to the hypothesis that the insula-accumbens circuit is a critical modulator of compulsive eating as well.

To address these gaps, we developed an animal model of compulsive-like eating symptoms, that, guided by models of substance use disorders, used intermittent short or long access to highly preferred food to elicit binge-like intake in rodents [28–33]. To test the influence of access on the development of compulsive-like eating, adolescent female rats with continuous or intermittent short (30 min/day) or long (24 h/day) access to a high-sucrose, chocolate-flavored diet were assessed per modified DSM/YFAS criteria. Escalated overeating was assessed through intake measurements and fixed-ratio (FR) self-administration of the palatable diet upon renewed access. Negative emotional state during “withdrawal” from the palatable diet was assessed via irritability-like behavior in handling and bottle-brush provocation tests [34]. Compulsive-like eating-directed behavior that persisted despite incorrect or adverse outcomes [35, 36] was defined as increased effort to obtain the diet under a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule (see Wade et al.) [37] and responding despite punishment, since PR as a sole measure of compulsivity has been debated (see Hopf and Lesscher for review) [38]. To test whether nucleus accumbens-projecting neurons from the anterior insula influenced compulsive-like food self-administration, self-administration was assessed during targeted optoinhibition of the glutamatergic projection from the anterior insula to nucleus accumbens. As per Seif et al. [25], we predicted reduction of compulsive-like, but not non-compulsive-like self-administration. Finally, because people with “food addiction” reportedly show unique endocrine profiles [39], we identified hormone profiles that distinguished those intermittent access rats that developed the most compulsive-like responding as well as profiles that distinguished rats with intermittent vs. continuous palatable food access.

Materials and Methods

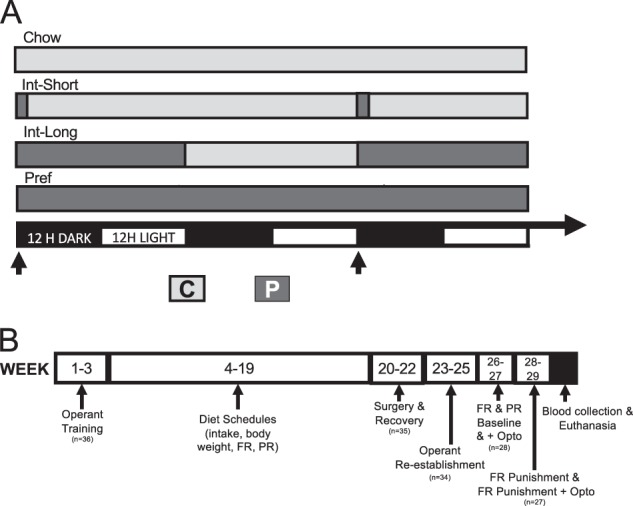

Animals

Because disordered eating is disproportionately prevalent in women [9, 10], we studied pair-housed young adult (n = 36, 125–150 g upon arrival) female Wistar rats (Charles River) separated by a plastic divider, in wire-topped plastic cages in a temperature- (22 °C) and humidity- (60%) controlled vivarium (12:12 h reverse light cycle). Before experiments, rats had ad libitum chow (45-mg pellets, 5TUM TestDiet, St. Louis, MO) and water. Body weights and food intake were recorded daily for 2–5 days before experiments. Procedures (Fig. 1b) adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by The Scripps Research Institute’s Institutional Care and Use Committee.

Fig. 1.

Diet schedules and experimental timeline. a Schematic shows diet schedules for Chow, Int-Short, Int-Long, and Pref rats on standard chow (C) or preferred (P) diets in relation to reverse light-dark cycle. Arrows indicate timing of operant self-administration sessions. b Schematic shows training and experimental timeline

Operant self administration training

Rats (n = 36) learned to self-administer chow pellets in previously described operant chambers [32] with 2 levers (one active/one inactive) equipped for optogenetic manipulation. Water was available ad libitum. Upon completion of a ratio requirement at the active lever, one pellet was delivered 0.5 s later, followed by a 3.75 s post-reinforcement timeout to promote pellet intake, during which responses had no consequences and were deemed “time-out” responses [40]. Responses at an inactive lever had no consequences. No explicit cues or lights were utilized in training or test sessions, and house lights remained off for the entire session. For training, all rats received the following operant sessions over 3 weeks reinforced by 5TUM chow, during which they received ad libitum 5TUM chow in their home cages. Training began with a single 24-h fixed ratio 1 (FR1) session, run together with their cagemate, which in our laboratory, accelerates performance and only occurs the first day. To accustom rats to briefer windows of self-administration, rats then received one or two individual 2-h FR1 sessions until a criteria of ≥75% discrimination between active vs. inactive lever was achieved followed by three to five individual 30-min FR1 sessions until each rat reached a criterion of 10 pellets/session. Finally, rats received one progressive ratio (PR) session whereby the response requirement increased exponentially with successive reinforcers (food pellets) following the progression described in Cottone et al. [41]: response ratio = [4 × (e# of reinforcer*0.075) − 3.8], rounded to the nearest integer. PR sessions ended when rats did not acquire another reinforcer in 14 min, with a maximum duration of 2-h. The “breakpoint” was the last response requirement completed.

Diet schedules

Rats were matched for baseline chow intake, body weight, percent body fat, and operant self-administration to 1 of 4 groups: ad libitum chow access (Chow); ad libitum access to the more preferred diet only (Pref); intermittent access (Int) to the preferred diet for 30 min (Short) or 24 h (Long) beginning at dark cycle onset for 3 nonconsecutive days/week with chow access otherwise (Fig. 1a). The diet, preferred over chow (80–91% mean preference, shown by all rats we have tested [31, 41], was sucrose-rich, chocolate-flavored, nutritionally complete 45-mg pellets (5TUL, Test Diets, St. Louis, MO) with similar macronutrient composition (~67% carbohydrates, 21% protein, and 13% fat by kcal) and caloric density (~3.44 kcal/g) vs. chow (3.30 kcal/g). Food intake was measured daily and body weights weekly.

Operant self-administration

Following training and assignment to diet schedule, all rats performed two weekly FR1 sessions (hereafter presented as the average of the two weekly sessions) and one weekly PR session at dark onset. These sessions took place on days that Int rats received access to the preferred diet, access to the preferred diet began at session start, and each rat responded for its group’s respective diet. The remainder of the duration of preferred diet access for rats with intermittent long access then occurs in the home cage, following the operant session. Three intermittent shock punishment (FR3), continuous food reinforcement (FR1) operant sessions were performed prior to optoinhibition (see below) during which a 0.1 mA, 0.5-s foot shock was delivered upon every third food reinforcer (pellet) earned. One standard 30 min FR1 session intervened each intermittent punishment session to promote and confirm recovery of responding. Following all operant sessions, all rats were returned to their home cage where their assigned diet and water were available ad libitum.

Body composition analysis

Whole body fat and lean mass were determined in awake rats via EchoMRI (Echo MRI-900, ACQ-SYS v.2008, Houston, TX) and expressed as % body weight 1 week before and 16 weeks after the diet schedule start.

Irritability bottle brush test

Rats were tested for irritability-like behavior 8–9 weeks after the diet schedule start at dark cycle onset, 45–47 h after the previous operant session. A treatment-naive experimenter measured responses of rats to 10 bottle brush trials as in Kimbrough et al. [34]; aggressive behaviors included: biting, boxing, following, mounting, tail rattling; defensive behaviors included: escape, digging, jumping/startle, and climbing cage walls. Counter-balanced and one week apart, rats were tested in an “uncued” state in a novel procedure room immediately after being placed in a clean cage with no additional stimuli and a “cued” state, whereby they were placed in the self-administration chamber for 7 min with no lever access and assessed immediately thereafter in the same room.

Stereotaxic surgery

After 17–18 weeks, rats received bilateral stereotactic infusion (0.6 µL/side; 0.1 µL/min) of AAV5-CaMKIIa-eYFP-Arch3.0 T (4 × 1012 vg/ml dissolved in 350 mM NaCl + 5% D-Sorbitol in PBS) or non-opsin control (AAV5-CaMKIIa-eYFP; 7.4 × 1012 vg/ml dissolved in 350 mM NaCl + 5% Sorbitol in 1xPBS (UNC Chapel Hill Viral Vector Core) into the AIC (AP + 2.8, ML +/− 4.8 from bregma; from dura DV −4.6 mm; with a 10-min post-injection wait before injector removal. Two mono-fiber optic cannula were implanted bilaterally in the Acb (AP + 2, ML +/− 2.6; DV −6.6 mm with 8° tilt away from midline). Following surgery, 34 rats continued in the study, as one rat was excluded for non-recovery of operant behavior and one was excluded following surgery complications.

Optoinhibition

After 2–3 weeks of recovery, self-administration was re-established for 3 weeks (eight operant sessions) whereby rats were tethered from their cannula via spring-shielded, fiber optic tethers and a rotary-joint splitter (Doric Lenses) to an (inactive) 532 nm laser (Shanghai Laser Century). Two rats were excluded from optoinhibition studies for loose/broken fiber optic cannulas. In tethered sessions, levers were extended after 5 min to allow acclimation. During weeks 24–25, tethered rats received six FR1 (30 min) and three PR sessions (mean ± SEM duration: 35 ± 4 min, max 2 h) without illumination (control) and one corresponding session with laser illumination (optoinhibited). Tests were separated by one intervening FR1 session to control for carry-over effects. Laser illumination began 5 min before session start for acclimation, lasted throughout the session, and produced ~10 mW [42–44] of light output, as measured pre-session (ThorLabs Photodiode Power Meter: Slim Sensor). During weeks 26–27 (6–8 weeks following surgery; within the window of maximal expression of an AAV5 virus) [45], tethered rats were tested for punished FR1 self-administration (30-min) without vs. with optoinhibition, with an intervening unpunished FR1 session for recovery of responding. Each reinforcement schedule (FR, PR, punished) was tested once under optoinhibition, in that order. Baselines were calculated as the average of the final two non-illuminated tethered sessions before the corresponding optoinhibition condition. Experimental conditions were not counterbalanced; to prevent day of testing artifacts, however, cohorts of rats, balanced for diet groups, were tested in staggered fashion across the test periods.

Opsin validation was performed in separate rats (n = 9) not on the diet schedules that were injected with opsin or control virus. Detailed methods for validation of opsin functionality and viral transfection (for animals under behavioral study) can be found in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Hormone assays

Cardiac blood from anaesthetized rats (sodium pentobarbital; 100 mg/kg i.p.) was immediately stabilized on ice with 0.5 M EDTA (1:10 v/v), DPP-IV Inhibitor (1:100) (EMD Millipore Corp), and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100) (P8340, Sigma-Aldrich). Plasma was obtained by centrifugation (15 min, 3000 × g, 4 °C) and stored at −20 °C until assayed for ghrelin, GLP-1, insulin, leptin, and pancreatic peptide (PP) levels via a rat multiplex hormone panel (RMHMAG-84K, Millipore Sigma) using a MAGPIX® System (Millipore Sigma).

Data analysis

Diet schedule-induced changes in food intake, body weight, and self-administration were analyzed using mixed-design two-way ANOVA; Group was a between-subjects factor and time (Week) a within-subject factor. Two-way ANOVA assessed Group differences (between-subject) in irritability-like behavior in cued vs. uncued conditions (within-subject). One-way ANOVA assessed differences between diet groups in change in body composition from baseline to 16 weeks. PR breakpoint survival was assessed by Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test. For optoinhibition and hormone profile analysis, Int rats were categorized as being high (vs. low) responders if they had PR responding > 2 standard deviations higher than the mean of all ad libitum fed rats (calculated from the final two control pre-opto tethered sessions relative to Chow and Pref pooled) [32]. Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used to interpret Group and Group × Time effects. Optoinhibition data were analyzed as mixed factorial two-way ANOVAs to identify key Group × Laser interactions. An acknowledged limitation of the present study is that a three-way ANOVA (Group × Laser × Active/Control virus) was not performed, because this would have required full No-Opsin virus groups for each diet condition. Instead, specificity of effects were determined in no opsin virus-injected controls, using paired t-tests (opto vs. baseline) and change of behavior as 1-tailed t-test vs. 0 to increase sensitivity to detect non-specific effects. Pearson and Spearman correlations were performed on z-scores, standardized separately for intermittent vs. ad libitum-fed diet groups, to understand how PR and punished FR self-administration measures related with one another, with escalated binge-like self-administration (non-punished FR) or total daily intake, or with initial or developed body weight and fat. For parameters collected over many weeks, data were averaged beginning from the first week they stabilized (FR active lever presses at weeks 4–6, PR pellets at weeks 6–9, intake at weeks 4–6, and body weight at weeks 4–9 when the slope of weight gain had decreased).

Multivariate hormone profiles that distinguished groups were identified via linear discriminant function analysis of z-scores for each hormone (GLP-1, ghrelin, leptin, insulin, PP). Two linear discriminant functions were identified that most discriminated group-related variance in the model (LD1 and LD2). This procedure identifies multivariate functions comprised by the hormone predictors that maximally distinguish subjects according to their a priori classifications as Chow, Pref, Int-Low or Int-High. Each rat’s LD1 and LD2 scores were then correlated with the above behavioral and ponderal measures. Correlations (rcorr[Hmisc]) and LDA (lda[MASS]) were performed in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing); other analyses involved GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

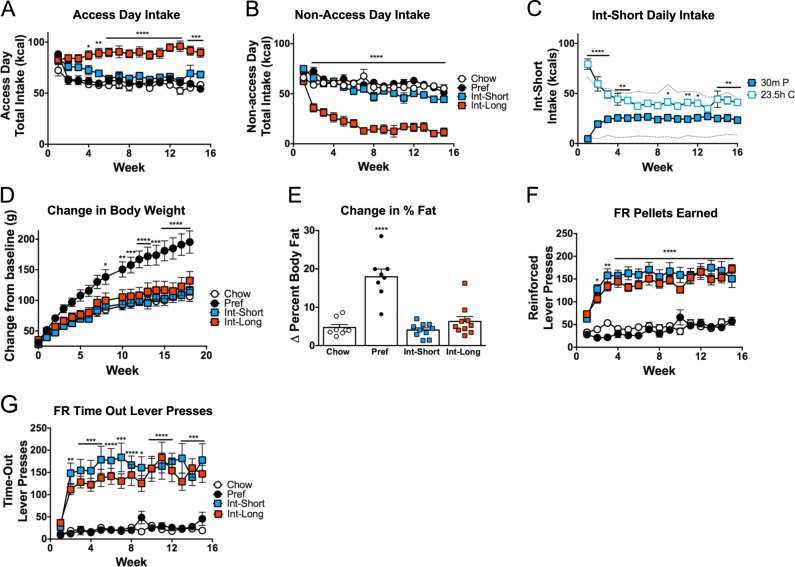

Daily energy intake and body weight

To test the hypothesis that rats with intermittent access to the preferred diet would develop food reward tolerance, daily caloric intake was measured. On access days to the preferred diet, Int-Long rats progressively ate more than all other groups (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 3.643, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a). On days that Int rats received chow only, Int-Long rats progressively under-ate vs. all other groups, stabilizing at levels ~25% of ad lib controls by week 7 (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 4.433, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Intake, Body Composition, and Fixed-ratio self-administration. a Int-Long rats have significantly greater food intake during days which they have access to the preferred diet by 4 weeks on the diet schedules compared with all other groups. b Int-Long rats have significantly less food intake by week 2 on days which they have access to the chow diet compared with all other groups. c By week 5, Int-Short rats do not eat significantly different amounts of chow diet in 23.5 h than they do of the preferred diet in 30 min. Dashed lines indicate average consumption of Chow rats during 23.5 h (upper line) and 30 min (lower line). d Pref rats have significantly greater body weight gain compared with all other groups by week 7. e Pref rats gained a significantly greater percentage of body fat by week 16 compared with baseline. f By week 2, both Int groups had significantly more reinforced and g non-reinforced (time-out) active lever presses compared with ad lib groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 8–10 per group in each panel

Despite showing normal overall daily intake, Int-Short rats changed how they ate on access days (Diet × Week: F(15, 270) = 14.29, p < 0.0001): By 6 weeks, they ate ~40% of their daily intake during 30 min of preferred diet access and had decreased chow intake during the remaining 23.5 h (Fig. 2c).

To test the hypothesis that rats with ad libitum but not intermittent access to the preferred diet have disproportionate weight and fat gain compared with rats with chow access only, as previously reported, weekly body weights and three body composition measurements were taken. Despite having intake similar to Chow rats (Fig. 2a, b), Pref rats gained significantly more weight over time compared with all other groups (Group × Week: F (51,544) = 7.507, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2d) and weighed significantly more at week 16 (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 10.22, p < 0.0001) (Fig. S1C). Pref rats increased percent body fat over 16 weeks (F(3,32) = 25.73, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2e) while having greater fat mass (F (3,32) = 11.37, p < 0.0001), but similar lean mass, at week 16 (F (3,32) = 1.9994, p = 0.1346) (Fig. S1A-B).

Fixed-ratio operant self administration

To assess the hypothesis that intermittent access would drive increased self-administration behavior in relation to the duration of access, rats were tested under an FR1 reinforcement schedule. Int rats progressively and comparably made more active lever presses (Fig. S1D) than ad libitum (both Chow and Pref) groups (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 4.099, p < 0.0001) by week 2 (q’s (480) > 4.86, p’s < 0.0037) with no differences in inactive presses (F(3,32) = 0.2039, p = 0.8929) (Fig. S1E).

More active lever presses reflected that Int rats of both access durations progressively and comparably earned more pellets (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 4.588, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2f) and had more non-reinforced “timeout” responses (Fig. 2g) than both ad lib fed groups (Group × Week: F(42,448) = 2.588, p < 0.0001). Over time, Int rats of both access durations disproportionately demonstrated greater ratios of “timeout” to reinforced presses (Group × Week: F(42,434) = 1.556, p < 0.02).

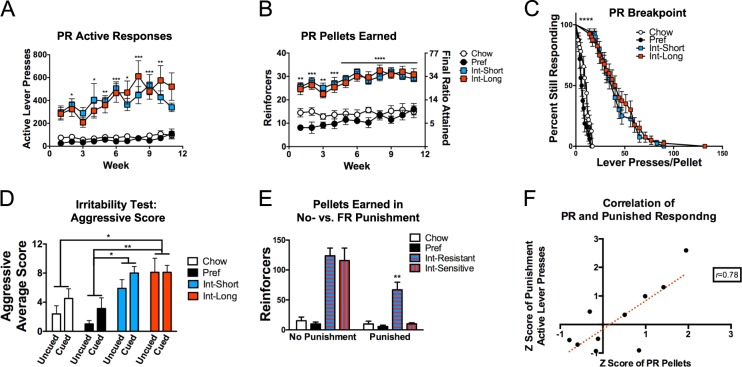

Progressive-ratio responding

Persistent responding under progressive ratio reinforcement schedules can indicate greater reinforcing efficacy of a substance [46] and, at high ratio requirements, has been proposed to indicate compulsive-like responding wherein responding perseverates despite “incorrect” (nonreinforced) outcomes [37]. To test the hypothesis that INT access promotes increased PR responding, rats were tested under an exponentially increasing progression. Int rats progressively and comparably showed more active lever presses in PR testing vs. both ad lib groups (Group × Week F (30,320) = 1.78, p < 0.009) (Fig. 3a) and obtained more reinforcers (pellets) and greater final ratios (Group F(3,32) = 44.13, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b). Survival analysis showed that each Int rat persisted lever-pressing beyond all ad lib rats (X2(3) = 183.7, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Progressive and intermittently punished fixed-ratio responding and irritability. a Both Int groups have significantly more active lever presses and b reinforcers earned through greater final ratios attained on the PR schedule compared with ad lib fed rats. c Significant group differences are present in breakpoint (lever presses/pellet) curves among Int and ad lib fed rats. d In the bottle-brush irritability test, both Int groups, regardless of cue/uncued state showed more aggressive responses that Pref rats, and Int-Long rats had more aggressive responses than Chow rats. e A subset (63%) of Int rats termed “Resistant” earned significantly more pellets during FR1 self-administration despite intermittent (FR3) contingent foot shock compared with “Sensitive” Int rats and all ad libs. f Progressive ratio and intermittently punished fixed ratio responding significantly correlate among Int-High rats. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 6–10 per group in each panel

Fixed-ratio punishment responding

Compulsive-like responding also has been operationalized as persistent responding despite adverse outcomes [46]. We therefore tested the hypothesis that INT access would promote continued self-administration despite intermittent punishment. A subset (63%) of Int rats (Int-shock resistant), representing both access durations persist in escalated responding for pellets (2 standard deviations > controls) despite a mild foot shock contingent on every 3rd pellet delivery (Group × Punishment interaction: F(3,29) = 6.565, p < 0.002) and had elevated numbers of reinforcers (pellets) earned (Group × Punishment interaction: F(3,29) = 9.639, p < 0.0002; punishment condition: Int-shock resistant vs. all other groups for active lever presses and reinforcers earned t’s(58) > 4.288, p’s < 0.02) (Figs. S2B & 3E).

Irritability-like behavior

Irritability-like behavior was assessed to test the hypothesis that rats with intermittent but not ad libitum access develop a negative emotional state when they do not have access to the preferred diet, as seen during ethanol withdrawal [34]. When confronted with a spinning bottle brush [34], Int rats showed increased aggressive-like responses toward the brush, irrespective of cue conditions (Group effect F(3,32) = 7.57, p < 0.0007). Both Int access groups showed more aggressive-like responses than Pref rats (q’s(32) > 4.715, p’s < 0.02), and Int-Long rats aggressed more than Chow rats (q(32) = 4.498, p < 0.02) (Fig. 3d). Irrespective of cue conditions, a Group main effect (F(3,32) = 3.212, p < 0.04) reflected that Pref rats made more defensive-like responses, but only reached significance in pairwise comparison to Int-Long rats (q(32) = 3.857, p < 0.05) (Fig. S2A).

High vs. low PR rats

In accordance with previous observations [32] and the hypothesis that a subset of rats with intermittent access may be uniquely susceptible to escalated progressive ratio responding for a preferred diet, when rats of both ad lib groups and both Int groups were combined, respectively, a subset of Int rats (54%) showed exacerbated (2 standard deviations > mean of all ad lib rats’ progressive ratio responding (Chow and Pref combined due to statistically comparable behavior, p > 0.99). These rats had with significantly higher PR active lever presses vs. all others (Int-High) (Group effect: F(3,20) = 12.84, p < 0.0001, q’s(20) > 5.09, p’s < 0.009) (Fig. 4e). Both putative measures of compulsive-like self-administration were highly correlated in Int-High rats (PR pellets to Punished active responses: Spearman rho = 0.64; Pearson r = 0.78 p < 0.01) (Fig. 3f). While the Int-High classification was based on performance during optogenetic tethered control conditions at study end, the escalated PR responding of this subgroup was highly stable and evident weeks earlier in the study (see Fig. S2C&D), similar to our previous reports [32].

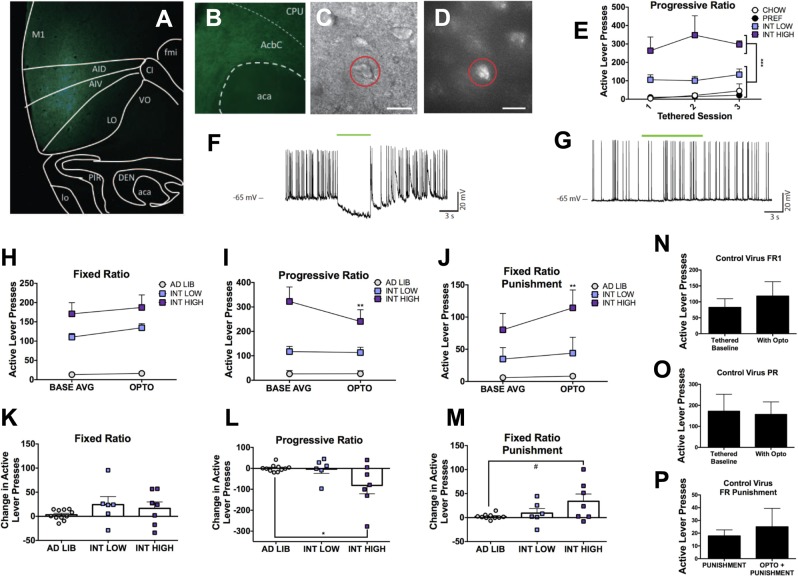

Fig. 4.

Optoinhibition. Representative images showing a eYFP expression at the anterior insular cortex injection site, b eYFP-labeled fibers in the nucleus accumbens core, and c differential interference contrast image of an d eYFP-labeled neuron for electrophysiology recording. e A subset of intermittent access rats of both diet durations demonstrated significantly elevated progressive ratio active lever presses compared with all other groups, here designated as “Int-High”. f Injected-current-evoked traces showing cessation of neuronal activity in the presence of LED light activation with Arch3.0 T virus. g Injected-current-evoked traces showing no effect in the presence of LED light activation with control virus. In vivo behavioral changes are shown in (h); an overall increase, but no diet specific effects on active lever presses observed in FR1 self-administration in the presence of optoinhibition compared with baseline. i Only Int rats classified as high-responding on PR self-administration show significant decreases in lever pressing in the presence of optoinhibition compared with baseline. j In contrast, the same Int-High responding rats increase lever pressing in the presence of optoinhibition compared with baseline fixed ratio punished FR1. Expressed as the average of individual change in active lever presses with optoinhibition from baseline: there was no significant differences in change in FR active lever presses between groups (k), a decrease of Int-High compared with ad lib PR lever presses (l), and a trend toward an increase of fixed ratio punished active lever presses between Int-High and ad lib rats (m). No significant difference without or with optoinhibition for animals injected with control virus in n FR1 active lever presses, o PR active lever presses, or p fixed ratio punishment active lever presses. *p < 0.05, #p < 0.06 compared with other diet groups. n = 5–10 per group

Behavioral and physiologic correlations

In previous studies, high progressive ratio-responding female rats overate more than Int-Low rats and displayed physiologic differences including a fat-sparing phenotype [32]. To further test the hypothesis that this subset of intermittent access rats with high levels of progressive ratio and intermittently punished responding, also had metabolic adaptations as has been seen in humans with compulsive eating pathologies [39], behavioral and physiologic measures were analyzed for correlation (Table 1) (Supplementary Fig. S3A-F). Uniquely, Int-High rats showed correlation of progressive ratio responding to percent body fat at study onset (week 0) (Spearmanʼs rho = 0.70, Pearsonʼs r = 0.76; p < 0.02) (Fig. S3A).

Table 1.

Behavioral and physiologic correlations were computed for rats of each diet classification

| a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates | r | p | |

| Insulin | Leptin | 0.5537 | 0.0007 |

| GLP.1 | PP | 0.4615 | 0.0060 |

| Leptin | LD1 | 0.8900 | 0.0000 |

| Ghrelin | LD2 | 0.5019 | 0.0025 |

| GLP.1 | LD2 | −0.7445 | 0.0000 |

| PP | LD2 | −0.6576 | 0.0000 |

| b | Chow | Pref | Int-Low | Int-High | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| FR active presses | PR pellets | – | – | 0.8412 | 0.0177 | – | – | – | – |

| FR active presses | Shock active | – | – | 0.9499 | 0.0011 | – | – | – | – |

| FR active presses | Intake | – | – | 0.8697 | 0.0110 | – | – | – | – |

| PR pellets | Shock active | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7842 | 0.0073 |

| PR pellets | Body mass | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.8303 | 0.0029 |

| PR pellets | % Fat mass week 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7624 | 0.0103 |

| PR pellets | % Fat mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6351 | 0.0485 |

| Shock active | Intake | – | – | 0.7966 | 0.0320 | 0.8433 | 0.0043 | – | – |

| Shock active | Body mass | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7229 | 0.0182 |

| Shock active | % Fat mass week 0 | – | – | – | – | −0.7747 | 0.0142 | 0.6795 | 0.0307 |

| Shock active | % Fat mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6358 | 0.0482 |

| Intake | Body mass | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6714 | 0.0335 |

| Intake | % Fat mass week 0 | – | – | – | – | −0.7548 | 0.0187 | – | – |

| Body mass | % Fat mass week 0 | 0.8438 | 0.0170 | – | – | – | – | 0.8897 | 0.0006 |

| Body mass | % Fat mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.9053 | 0.0003 |

| Body mass | % Lean mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.8374 | 0.0025 |

| % Fat mass week 0 | % Fat mass week 16 | 0.8136 | 0.0260 | – | – | – | – | 0.9002 | 0.0004 |

| % Fat mass week 0 | % Lean mass week 16 | −0.8103 | 0.0271 | – | – | – | – | −0.8416 | 0.0023 |

| % Fat mass week 16 | % Lean mass week 16 | −0.9866 | 0.0000 | −0.9863 | 0.0000 | −0.9518 | 0.0001 | −0.9841 | 0.0000 |

| % Lean mass week 16 | Leptin | −0.9602 | 0.0006 | – | – | −0.9708 | 0.0000 | −0.8063 | 0.0048 |

| LD1 | PR pellets | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6917 | 0.0267 |

| LD1 | Shock active | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7575 | 0.0112 |

| LD1 | Intake | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6853 | 0.0287 |

| LD1 | Body mass | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7220 | 0.0184 |

| LD1 | % Fat mass week 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7606 | 0.0106 |

| LD1 | % Fat mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | 0.8310 | 0.0055 | 0.6745 | 0.0324 |

| LD1 | % Lean mass week 16 | – | – | – | – | −0.8058 | 0.0087 | −0.6425 | 0.0451 |

| LD2 | Intake | – | – | – | – | 0.7646 | 0.0164 | – | – |

| LD2 | % Fat mass week 0 | – | – | −0.8312 | 0.0205 | – | – | – | – |

Int-High rats uniquely have correlations of measures of compulsivity (PR Pellets and Shock-contingent Active lever presses) with one another and with metabolic measures including body mass, and percent body fat at both weeks 0 and 16. Further, the hormone profile LD1, largely correlated with leptin concentrations, also uniquely correlated with the compulsive measures in Int-High rats. All significant (p < 0.05) correlations are presented as correlation coefficient (r) and p-value (p)

Circulating hormone levels at study end identified Pref rats as having elevated leptin levels (F(3,30) = 9.591, p < 0.0002) (Fig. S4F). Using discriminant function analysis, two unique hormone profiles were identified among all rats: LD1 scores, largely indicating jointly greater leptin and lower ghrelin levels, were greater in Pref rats (F(3,30) = 15.53, p < 0.0001) and also correlated to both PR and intermittently punished FR responding in Int-High rats (Spearman rho’s > 0.68, Pearson r’s > 0.69; p’s < 0.03). LD2 scores, relating to jointly lower GLP-1 and PP levels and higher ghrelin levels, were uniquely low in Int-High rats (F(3,30) = 5.308, p < 0.005) (Fig. S4E).

Optoinhibition of insula-nucleus accumbens projections

To test the hypothesis that the insula-nucleus accumbens projections modulate compulsive-like responding, optoinhibition of the circuit was performed during operant self-administration sessions. Placement of virus and fiber optics were verified (Fig. 4a, b), and the opsin was validated for inhibitory effect in neurons expressing Arch3.0 T + eYFP or eYFP alone (Fig. 4c, d). In Arch3.0T expressing AIC neurons, light inhibited current-induced action potential frequency from baseline while having no effect in eYFP-only neurons (n = 9; t(4) = 5.528, p < 0.0052) (Fig. 4f, g, also see Fig. S5G &H).

In vivo optoinhibition of CaMKIIa-expressing projections from the AIC-Acb resulted in a descriptively small (~20 lever presses), but reliable, effect of laser optoinhibition (F(1,21) = 6.072, p < 0.03) to increase FR active lever presses (Fig. 4h). The mean increase in active lever presses did not differ between groups (F(2,21) = 1.194, p > 0.3) and was of such small magnitude that no individual group differed from theoretical no change when analyzed individually (p’s > 0.2) (Fig. 4k). Likewise, optoinhibition modestly increased the number of pellets obtained in all groups (F(1,21) = 4.354, p < 0.05), but did not reliably alter time out responding (p > 0.13) (Fig. S5 A &B).

In contrast, in the PR paradigm, a significant Group × Laser Condition interaction (F(2,21) = 4.196, p < 0.03) (Fig. 4i) indicated that “Int-High” rats showed significantly decreased active lever presses during optoinhibition vs. no laser control conditions (t(21) = 3.475, p < 0.007); this decrease significantly differed compared with the lack of such a change observed in all ad lib fed rats (t(21) = 2.739, p < 0.04) (Fig. 4l). Likewise, optoinhibition selectively reduced the breakpoint achieved by Int-High rats (Group × Laser Condition: F (2,21) = 4.631, p < 0.022; t(21) = 3.539, p < 0.006) (Fig. S5D), but did not reach significance in the resulting number of pellets earned (F(2,21) = 1.914, p > 0.17) (Fig. S5C).

Optoinhibition also elicited modest diet-specific effects on intermittently punished fixed-ratio food self-administration (Group × Laser Condition: F(2,20) = 3.394, p < 0.054). Here, unlike in PR, optoinhibition increased average active lever presses by the same Int-High rats (t(20) = 3.564, p < 0.006) (Fig. 4j). The increase in active lever presses shown by Int-High rats trended higher than the change seen in all ad lib rats (t(20) = 2.556, p < 0.056) (Fig. 4m). Optoinhibition resulted in a significantly increased number of pellets earned in the intermittently punished FR self-administration condition overall (Laser main effect: p < 0.02) (Fig. S5E) as well as an increase in time out responses during the punished fixed-ratio session that was selectively seen in Int-High rats (Group × Laser Condition: F(2,20) = 4.036, p < 0.034; t(20) = 3.725, p < 0.005) (Fig. S5F).

In contrast to positive results seen when grouped by progressive ratio performance, effects of optoinhibition did not differ according to assigned groups based on schedule of access to the preferred diet (Int-Short, Int-Long, Chow, Pref) (Fig. S6A-F).

Rats injected with the control virus were not significantly affected by optoinhibition in any reinforcement schedule or outcome measure (Fig. 4n–p & Fig. S7 A-F). Rats with either virus injection anatomical “misses” (n = 4) were not included in any analyses, but descriptively, the rats injected with the opsin virus (n = 3) did not show a similar pattern of opto-induced changes when the laser was on. Rather than a reduction of PR responding, we saw a non-significant mean increase of 24.9 active presses; rather than a modest increase in FR responding, we saw a non-significant mean decrease of 13.3 presses; and on FR punished responding we saw a non-significant mean increase of 24.5 presses.

Discussion

Towards modeling food addiction symptoms per diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders and food addiction [1–3], this report demonstrates that rats given intermittent access to palatable food develop addiction-like behaviors that resemble tolerance, escalation of intake, withdrawal irritability, and compulsive use. As reported in humans [39, 47], the development of compulsive-like behavior was associated with unique endocrine profiles in rats. Optogenetic analysis implicated differential recruitment of neurocircuitry projecting from the anterior insular cortex to the nucleus accumbens in high-responding rats that modulated their compulsive-like self-administration behavior.

Food reward tolerance

As previously shown [31, 32], rats with intermittent long, but not continuous, access to a high-sucrose, chocolate-flavored diet ate less chow, in weight and calories, than all other rats on days which they did not have access to the preferred diet. This effect was not present in rats with intermittent short access. Both Int groups instead increased their preferred diet intake; Int-Short rats ate as much preferred diet in 30 min as they did during the other 23.5 h with chow.

Escalation of intake

Binge-like fixed-ratio self-administration developed in rats with intermittent access. By week 2, rats on intermittent schedules of both durations had ~3-fold increased reinforced lever presses, compared with ad libitum fed groups, while not differing from one another.

Withdrawal-like state

Negative emotional state was measured as hyper-irritability in intermittent-access rats during “withdrawal” from the preferred diet. We assessed irritability via a bottle brush test [34] in both cued and uncued states after the period of nonaccess to the preferred diet typical for each intermittent-access group (24–48 h). We hypothesized that, similar to drug use cues [48], frustrative food use cues would promote even greater withdrawal irritability. In fact, both intermittent access groups had similarly elevated aggressive behaviors toward the bottle brush in cued vs. uncued states. Pref rats instead had increased defensive responses. The lack of effect of the chamber context might reflect a ceiling effect of irritable responses within brief trials or the presence of implicit cues (e.g., experimenters, transport) in the uncued condition in a novel testing room. Hyperirritability is a motivating negative emotional state common to drug withdrawal [49]; other negative emotions that may perpetuate the addiction cycle, including anxiety, depression, and anhedonia, warrant further study.

Increased effort to obtain food

Under a progressive-ratio [32, 46] schedule of operant self-administration, rats with intermittent access of either duration developed increased active lever presses, reinforcers earned, and elevated breakpoints vs. both ad libitum fed groups, while not differing from one another. Under a fixed-ratio schedule, intermittent access rats showed disproportionately increased food-directed responding during the “timeout” period.

Eating despite risk of adverse consequences

When every third pellet delivery resulted in a foot shock, a subset of rats with intermittent access, equally from both duration schedules, persisted despite punishment (Int-Resistant); the remaining rats (Int-Sensitive) reduced responding to the low levels of ad libitum fed rats. Punishment resistance strongly correlated with increased effort to obtain food (PR breakpoints). These individual differences resemble models of drug dependence [50–52] and binge eating proneness [53–55], wherein only a subset of animals with access to the drug or palatable food develop compulsive-like behavior. The collective findings also model individual vulnerability in humans to develop compulsive use after access to palatable food or substances of abuse [56].

Metabolic characteristics

Rats with continuous access to the preferred diet became heavier and fattier, despite daily caloric intake similar to chow controls, suggesting an influence of diet palatability, sucrose or other micronutrients on ponderal outcomes [31]. Although intermittent access rats collectively did not gain more weight than controls, within the highly compulsive subset, greater initial adiposity prospectively correlated with future compulsive-like behaviors (PR responding). However, given the small sample size of highly compulsive animals and their variability, these findings warrant further investigation on the causal and/or mechanistic basis of this relationship.

Because human obese patients diagnosed with food addiction are hypothesized to show unique hormone profiles [39], we sought to identify what endocrine profiles differentiate our compulsive eating model. Discriminant function analysis showed that Int high-responders had jointly higher GLP-1 and PP with lower ghrelin levels than other groups. A second function, reflecting greater leptin levels, correlated with more compulsive self-administration (higher PR and punished responding) and baseline body fat in high-responder intermittent rats, and not low-responder or ad lib access rats. Unlike studies of obese, food-addicted patients, intermittent access rats maintained a normal body weight, a key influence on these ingestive and metabolic regulatory hormones. As consensus on hormonal changes in “food addicted” humans remains unclear, we propose that study of the present differentiating hormone profiles merits further study in non-obese and obese “food addicted” populations.

Insula-accumbens involvement

Since the insular cortex has been implicated in addiction-related behavior [24] and its projections from the anterior region to the nucleus accumbens have been shown to mediate compulsive-like alcohol intake in rats [25] and be dysregulated in disordered eating in humans [26, 27], we hypothesized that these projections may be involved in compulsive-like food intake. Optoinhibition of the anterior insula-accumbens-projecting neurons resulted in a marginal increase in (putatively non-compulsive) fixed-ratio responding overall. As predicted, optoinhibition reduced progressive-ratio responding selectively in high-responding rats. Unexpectedly, the same high-responding rats significantly and uniquely increased their responding when the insula-accumbens projection was optoinhibited during punished responding.

As the insula also subserves nociception and associated evaluative interoception [12], optoinhibition may have disrupted representation of the aversive shock, leading to a greater release from shock suppression in Int-High rats. These findings are also compatible with the hypothesis that optoinhibition of this circuit may reduce the salience of a visceral determinant of behavior such that in the PR paradigm, the optoinhibition reduces the appetitive aspect, whereas in the punishment setting it reduced the prevailing aversive aspect. Whatever the basis, optoinhibition selectively influenced the two measures of conflicted self-administration only in the high-responder subset of intermittent access rats. The results support the hypothesis that insula-accumbens projections gain a greater modulatory role in compulsive, addictive-like eating. These findings warrant further investigation of this circuit in the context of compulsive-like eating, and is an area of ongoing work, including investigating abnormalities of this circuit and its excitability in highly compulsive-like animals.

Conclusion

A subset of rats with intermittent access to palatable food develop food addiction symptoms in broad agreement with a hypothesized compulsivity construct [1–3] and modified diagnostic symptoms of substance use disorders [5, 6]. Behavioral signs include intake measures of food reward tolerance and escalation of intake; hyper-irritability during withdrawal; and escalated progressive ratio self-administration and punishment-resistant responding. Projections from the anterior insular cortex to the nucleus accumbens appear to modulate the most compulsive-like eating behaviors in our model. Finally, a unique endocrine profile involving heightened GLP1- and PP with lower ghrelin characterized rats with the most addictive-like eating, as well as correlative relations of compulsive eating to both leptin and adiposity. These novel neurobiological and metabolic adaptations associated with addictive-like eating in a rodent model warrant further investigation.

Funding and disclosure

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under awards AA06420, AA020608, AA026638, AA027700 as well as the Pearson Center for Alcoholism and Addiction Research, NIH/NIAAA Institutional Training Grant T32 AA007456, National Institutes of Health Clinical Translational Science Award (NIH CTSA) STSI TL1 Training Program TR002551. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Paul Schweitzer for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Samantha Spierling, Email: samspier@scripps.edu.

Eric P. Zorrilla, Email: ezorrill@scripps.edu

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-019-0538-x).

References

- 1.Moore CF, Sabino V, Koob GF, Cottone P. Pathological overeating: emerging evidence for a compulsivity construct. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;42:1375–89. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore CF, Sabino V, Koob GF, Cottone P. Neuroscience of compulsive eating behavior. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:469. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parylak SL, Koob GF, Zorrilla EP. The dark side of food addiction. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pursey KM, Stanwell P, Gearhardt AN, Collins CE, Burrows TL. The prevalence of food addiction as assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2014;6:4552–90. doi: 10.3390/nu6104552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Development of the Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2016;30:113–21. doi: 10.1037/adb0000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, Carter JC, Kaplan AS, Kennedy JL. Evidence that ‘food addiction’ is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite. 2011;57:711–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avena NM, Bocarsly ME, Hoebel BG, Gold MS. Overlaps in the nosology of substance abuse and overeating: the translational implications of “food addiction”. Curr Drug Abus Rev. 2011;4:133–9. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104030133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagl M, Jacobi C, Paul M, Beesdo-Baum K, Hofler M, Lieb R, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and natural course of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among adolescents and young adults. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25:903–18. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0808-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr., Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fryar CD, Gu Q, Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2011–2014. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 3, Analytical Studies. 2016;1–46. [PubMed]

- 12.Craig AD. How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalon E, Hong JY, Tobin C, Schulte T. Psychological and neurobiological correlates of food addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2016;129:85–110. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutelle KN, Wierenga CE, Bischoff-Grethe A, Melrose AJ, Grenesko-Stevens E, Paulus MP, et al. Increased brain response to appetitive tastes in the insula and amygdala in obese compared with healthy weight children when sated. Int J Obes. 2015;39:620–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stice E, Yokum S. Gain in body fat is associated with increased striatal response to palatable food cues, whereas body fat stability is associated with decreased striatal response. J Neurosci. 2016;36:6949–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4365-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wonderlich JA, Breithaupt LE, Crosby RD, Thompson JC, Engel SG, Fischer S. The relation between craving and binge eating: Integrating neuroimaging and ecological momentary assessment. Appetite. 2017;117:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Lacadie C, Small DM, Sherwin RS, Potenza MN. Neural correlates of stress- and food cue-induced food craving in obesity: association with insulin levels. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:394–402. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank GK, Shott ME, Riederer J, Pryor TL. Altered structural and effective connectivity in anorexia and bulimia nervosa in circuits that regulate energy and reward homeostasis. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e932. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KR, Ku J, Lee JH, Lee H, Jung YC. Functional and effective connectivity of anterior insula in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Neurosci Lett. 2012;521:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro DC, Cole SL, Berridge KC. Lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum roles in eating and hunger: interactions between homeostatic and reward circuitry. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:90. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesner RP, Gilbert PE. The role of the agranular insular cortex in anticipation of reward contrast. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88:82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank S, Kullmann S, Veit R. Food related processes in the insular cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:499. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naqvi NH, Bechara A. The hidden island of addiction: the insula. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seif T, Chang SJ, Simms JA, Gibb SL, Dadgar J, Chen BT, et al. Cortical activation of accumbens hyperpolarization-active NMDARs mediates aversion-resistant alcohol intake. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1094–100. doi: 10.1038/nn.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner A, Aizenstein H, Mazurkewicz L, Fudge J, Frank GK, Putnam K, et al. Altered insula response to taste stimuli in individuals recovered from restricting-type anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;33:513–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shott ME, Pryor TL, Yang TT, Frank GK. Greater insula white matter fiber connectivity in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:498–507. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parylak SL, Cottone P, Sabino V, Rice KC, Zorrilla EP. Effects of CB1 and CRF1 receptor antagonists on binge-like eating in rats with limited access to a sweet fat diet: lack of withdrawal-like responses. Physiol Behav. 2012;107:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cottone P, Sabino V, Steardo L, Zorrilla EP. Opioid-dependent anticipatory negative contrast and binge-like eating in rats with limited access to highly preferred food. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;33:524–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corwin RL. Binge-type eating induced by limited access in rats does not require energy restriction on the previous day. Appetite. 2004;42:139–42. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreisler AD, Garcia MG, Spierling SR, Hui BE, Zorrilla EP. Extended vs. brief intermittent access to palatable food differently promote binge-like intake, rejection of less preferred food, and weight cycling in female rats. Physiol Behav. 2017;177:305–16. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spierling SR, Kreisler AD, Williams CA, Fang SY, Pucci SN, Kines KT, et al. Intermittent, extended access to preferred food leads to escalated food reinforcement and cyclic whole-body metabolism in rats: Sex differences and individual vulnerability. Physiol Behav. 2018;192:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cifani C, Polidori C, Melotto S, Ciccocioppo R, Massi M. A preclinical model of binge eating elicited by yo-yo dieting and stressful exposure to food: effect of sibutramine, fluoxetine, topiramate, and midazolam. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:113–25. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimbrough A, de Guglielmo G, Kononoff J, Kallupi M, Zorrilla EP, George O. CRF1 receptor-dependent increases in irritability-like behavior during abstinence from chronic intermittent ethanol vapor exposure. Alcohol, Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:1886–95. doi: 10.1111/acer.13484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koob GF. Theoretical frameworks and mechanistic aspects of alcohol addiction: alcohol addiction as a reward deficit disorder. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2013;13:3–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-28720-6_129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vendruscolo LF, Barbier E, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Whitfield TW, Jr., Logrip ML, et al. Corticosteroid-dependent plasticity mediates compulsive alcohol drinking in rats. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7563–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0069-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wade CL, Vendruscolo LF, Schlosburg JE, Hernandez DO, Koob GF. Compulsive-like responding for opioid analgesics in rats with extended access. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;40:421–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopf FW, Lesscher HM. Rodent models for compulsive alcohol intake. Alcohol. 2014;48:253–64. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedram P, Sun G. Hormonal and dietary characteristics in obese human subjects with and without food addiction. Nutrients. 2014;7:223–38. doi: 10.3390/nu7010223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fekete EM, Zhao Y, Szucs A, Sabino V, Cottone P, Rivier J, et al. Systemic urocortin 2, but not urocortin 1 or stressin 1-A, suppresses feeding via CRF2 receptors without malaise and stress. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1959–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cottone P, Sabino V, Steardo L, Zorrilla EP. Intermittent access to preferred food reduces the reinforcing efficacy of chow in rats. Am J Physiol Regulatory, Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1066–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90309.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deisseroth, K. Predicted irradiance values: model based on direct measurements in mammalian brain tissue. http://www.stanford.edu/group/dlab/cgi-bin/graph/chart.php.

- 43.Gradinaru V, Mogri M, Thompson KR, Henderson JM, Deisseroth K. Optical deconstruction of parkinsonian neural circuitry. Science. 2009;324:354–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1167093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tye KM, Prakash R, Kim SY, Fenno LE, Grosenick L, Zarabi H, et al. Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety. Nature. 2011;471:358–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mason MRJ, Ehlert EME, Eggers R, Pool CW, Hermening S, Huseinovic A, et al. Comparison of AAV serotypes for gene delivery to dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Ther. 2010;18:715–24. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134:943–4. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gearhardt AN, Boswell RG, White MA. The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eat Behav. 2014;15:427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pickens CL, Airavaara M, Theberge F, Fanous S, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:411–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koob GF. Neurocircuitry of alcohol addiction: synthesis from animal models. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;125:33–54. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Walther D, Brannock C, Ladenheim B, McCoy MT, et al. Increased expression of proenkephalin and prodynorphin mRNAs in the nucleus accumbens of compulsive methamphetamine taking rats. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37002. doi: 10.1038/srep37002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelloux Y, Everitt BJ, Dickinson A. Compulsive drug seeking by rats under punishment: effects of drug taking history. Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:127–37. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giuliano C, Pena-Oliver Y, Goodlett CR, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET, et al. Evidence for a long-lasting compulsive alcohol seeking phenotype in rats. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;43:728–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oswald KD, Murdaugh DL, King VL, Boggiano MM. Motivation for palatable food despite consequences in an animal model of binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:203–11. doi: 10.1002/eat.20808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calvez J, Timofeeva E. Behavioral and hormonal responses to stress in binge-like eating prone female rats. Physiol Behav. 2016;157:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinclair EB, Culbert KM, Gradl DR, Richardson KA, Klump KL, Sisk CL. Differential mesocorticolimbic responses to palatable food in binge eating prone and binge eating resistant female rats. Physiol Behav. 2015;152:249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kendler KS, Myers J. Addiction resistance: definition, validation and association with mastery. Drug alcohol Depend. 2015;154:236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.