Abstract

Bone and soft tissue sarcomas of the head and neck are a heterogenous group of tumors with overlapping features. Distinguishing between the various subtypes is challenging but necessary for appropriate diagnosis and management. The purpose of this article is to discuss the role of imaging in evaluating head and neck tumors, provide a general radiographic approach in differentiating between benign versus malignant lesions and give examples of selected subtypes of bone and soft tissue sarcomas in the head and neck with classic or pathognomonic imaging findings.

Keywords: Bone and soft tissue sarcomas, Imaging, Radiology, Head and neck, Sarcomas

Introduction

Sarcomas represent a rare and diverse group of malignant neoplasms arising from mesenchymal tissue. They account for about 1% of all solid malignancies in adults and 21% of those in children [1]. These tumors are widely distributed throughout the body, found most commonly in the extremities, trunk and viscera [2]. Sarcomas of the head and neck are relatively uncommon–accounting for about 5–15% of all sarcomas and 1% of all head and neck malignancies [3, 4]. Though rare, they are of immense significance due to the potential for aggressive behavior and poor prognosis.

The diagnosis of head and neck sarcomas is challenging as the presenting signs and symptoms are often nonspecific. Differentiating between the more than 50 known histologic subtypes is important as treatment strategies vary depending on the tumor type. As prognosis worsens with histologic grade, tumor extent, and metastatic involvement, early detection and diagnosis are essential in improving treatment outcomes. Imaging remains one of the key components in the initial evaluation, management, and follow-up of head and neck tumors. In this article, we discuss the role of imaging in the diagnosis of head and neck tumors, provide a radiographic approach for differentiating non-aggressive versus aggressive lesions, and discuss common sarcoma subtypes with their associated imaging findings.

Role of Imaging in the Evaluation of Head and Neck Lesions

The differentiation of head and neck tumors is difficult owing to the inherent anatomic complexity and numerous varying pathologies occurring in this region. In addition to identifying, localizing and characterizing the tumors, imaging helps to establish the extent of local involvement, bone invasion, nodal disease and distant metastasis. Imaging provides critical information in guiding tissue biopsy, surgical resection, and targeted chemotherapy or radiation. Following definitive tissue diagnosis and appropriate treatment, imaging plays an important role in the assessment of treatment response and disease recurrence.

Cross sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the mainstay of imaging head and neck pathologies. CT is most often used in the initial evaluation of palpable head and neck masses or non-specific symptoms. Multi-detector arrays acquire x-ray data in a helical pattern which is then reconstructed into images that are based on tissue density, measured in Hounsfield units (“HU”). For example, air measures − 1000 HU, fat measures approximately − 70 HU, water measures 0 HU, soft tissues such as muscle and brain measure approximately 30–40 HU, bone and calcium measure approximately 300–800 HU, and metals measure approximately 1000–3000 HU. CT is particularly useful in the evaluation of bony structures and calcifications. The use of intravenous high-density iodinated contrast agents can augment soft tissue features based on vascularity.

Magnetic resonance imaging provides superior soft-tissue detail compared to CT. MR images are based upon a tissue’s proton content and re-alignment within a magnetic field when introduced to an external radiofrequency energy. A variety of MRI sequences based upon different electromagnetic properties of tissue protons are collectively used to evaluate a lesion. Table 1 summarizes the main MRI sequences which include T1-weighted, T2-weighted, T1-weighted post-contrast, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

Table 1.

Main MRI sequences in the evaluation of head and neck lesions

| Sequence | Basic concept | Clinical utility |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | Evaluates tissue content by detecting time to longitudinal relaxation of protons following exposure to an external radiofrequency energy | Materials that exhibit high T1 signal intensity include gadolinium, fat, protein, melanin, and certain stages of blood breakdown products |

| T2 | Evaluates tissue content by detecting time to transverse relaxation of protons following exposure to an external radiofrequency energy | T2 hyperintensity is associated with fluid-heavy tissue seen in inflammation/edema and various tumors. T2 hypointensity reflects hypercellularity, where there is a relative lack of fluid within the tumors |

| T1 post-contrast | Evaluates tissue vascularity using gadolinium-based contrast which shortens T1 relaxation time and results in high T1 signal | Hypervascularity and rapid soft tissue tumor enhancement may suggest malignancy, though there are known exceptions |

| DWI and ADC | Suggests lesion cellularity by detecting Brownian motion of water protons, which is lower in hypercellular tissues | Malignant lesions are often hypercellular and demonstrate low diffusivity, seen as bright signal on DWI and dark signal on ADC |

DWI diffusion-weighted imaging, ADC apparent diffusion coefficient

Ultrasonography can be used in the evaluation of superficial head and neck tumors. A transducer transmits high frequency sound waves that travel at varying speeds through different media and are then reflected off tissue surfaces back to the transducer to generate an image. With the use of color doppler, additional information regarding tissue vascularity can be obtained, and is useful for distinguishing between cysts and solid tumors. Another advantage of ultrasonography is the ability to perform the scanning in real-time which facilitates biopsy of tumors.

F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (F-18 FDG PET) is typically an adjunct modality used in the staging of cancers following tissue diagnosis. PET employs the notion that more metabolically active tissues, including tumors, exhibit glucose uptake, measured in standardized uptake values (SUV). In general, the greater the metabolic activity, the higher the SUV value. PET helps localize metabolically active tumors and additional sites of metastatic disease throughout the body. PET can also be used post-treatment in the assessment of treatment response and in the surveillance of recurrent disease.

Imaging Approach to Benign Versus Malignant Features

The approach to lesion characterization described in Table 2 provides a general guideline for recognizing typical features of benign versus malignant tumors. This includes the evaluation of tumor size, morphology, margins, contrast enhancement, restricted diffusion, metabolic activity, as well as local and distant extension. Independently, these features are generally nonspecific, but the presence of multiple concordant findings can substantially narrow the differential diagnosis, particularly when coupled with additional clues from the clinical history including age, sex, genetic predisposition, history of radiation, and other risk factors. Specifically in the recognition of sarcomas, several features have been found to be suggestive of malignancy and higher grade: progressive size enlargement, lesion heterogeneity, irregular contours, irregular internal septations, internal necrosis, intratumoral hemorrhage, early prolonged enhancement, peritumoral edema, and adjacent soft tissue, bone or neurovascular invasion [5–8]. Bone erosion is best identified on X-ray or CT as destruction of the cortical bone. Marrow involvement is best demonstrated on MRI and seen on T1-weighted images as replacement of normal fat high signal intensity [9]. Metastatic adenopathy features enlarged lymph nodes or irregular lymph nodes often with replacement of the normal fatty hilum, central necrosis, and increased heterogeneous enhancement.

Table 2.

General imaging features of benign versus aggressive tumors

| Imaging feature | Benign | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Size/Growth | Size alone is nonspecific, however slow-growing tumors are more often indolent and more likely to be benign or non-aggressive | Fast-growing tumors tend to be more aggressive and always warrant additional work-up |

| Tumor Morphology | Homogeneity is a feature of benignity. Simple cysts, with thin smooth walls and fluid density on CT or high T2 signal on MRI, can be definitively characterized as benign | Increasing tumor complexity with thick walls, internal septations, solid components and enhancement may be benign or malignant |

| Tumor Margin | Benign lesions tend to respect fat and fascial planes, displaying smooth and well-circumscribed margins | Malignant lesions are often more infiltrative, demonstrating irregular, indistinct or obscured margins which can extend beyond fat or fascial planes |

| Contrast Enhancement | Tumors that demonstrate non-enhancement tend to be benign | Rapid and prolonged enhancement are more suspicious for malignancy, though many benign tumors also demonstrate vascularity [6] |

| Diffusivity | Benign lesions do not often demonstrate restricted diffusivity | Malignant lesions often demonstrate low diffusivity, which corresponds to a high signal on DWI and low signal on ADC. ADC has been shown to correlate with stage of tumor cell differentiation and presence of necrotic tissue [7] |

| Metabolic Activity | Increased FDG uptake is not typically seen in benign entities. Infection and inflammation are exceptions | Aggressive tumors generally exhibit increased metabolic activity. High-grade sarcomas typically demonstrate significantly higher SUVs than do low-grade sarcomas [8] |

| Tumor Extension | Large benign lesions may cause mass effect but do not typically cause locoregional invasion or result in distant spread | Malignant lesions may invade into adjacent structures including bones, nerves and lymph nodes |

Selected Sarcomas of the Head and Neck

Sarcomas comprise over 50 different histologic subtypes that are classified according to their line of differentiation, some of which are summarized in Table 3. About 80% of sarcomas within the head and neck originate in the soft tissues and 20% originate in the bones. The most frequently reported adult sarcomas in the head and neck include undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (previously malignant fibrous histiocytoma or MFH), leiomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. In children and adolescents, the most common sarcomas include rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. The clinical and imaging features of selected head and neck sarcomas are highlighted below.

Table 3.

Classification of head and neck soft tissue and bone tumors [7]

| Tissue Origin | Benign | Intermediate (locally aggressive or rarely metastatic) | Malignant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone |

Osteoma Osteoid osteoma Osteoblastoma |

Osteosarcoma Ewing sarcoma |

|

| Cartilage |

Chondroma Chondroblastoma |

Chondrosarcoma subtypes – Conventional – Mesenchymal |

|

| Adipose |

Lipoma Lipoblastoma Hibernoma Lipomatosis |

Well-differentiated liposarcoma |

Liposarcoma subtypes – Dedifferentiated – Myxoid – Pleomorphic |

| Smooth Muscle |

Leiomyoma Angioleiomyoma |

Leiomyosarcoma | |

| Skeletal Muscle | Rhabdomyoma |

Rhabdomyosarcoma subtypes – Alveolar – Embryonal – Pleomorphic – Spindle cell |

|

| Fibrous |

Nodular fasciitis Deep fibromatosis Fibromatosis coli Myofibroma Giant cell angiofibroma |

Desmoid-type fibromatosis Solitary fibrous tumor Inflammatory pseudotumor |

Fibrosarcoma |

| Nerve Sheath |

Schwannoma Neurofibroma |

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | |

| Vascular |

Hemangioma Lymphangioma |

Hemangioendothelioma Kaposi sarcoma |

Angiosarcoma |

| Pleomorphic | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

Osteosarcomas are malignant mesenchymal neoplasms characterized by the production of osteoid matrix. Osteosarcomas are seen most commonly in the metaphysis of long bones, and only about 10% occur in the head and neck [4, 11]. Classic craniofacial locations include the mandible, maxilla and calvarium. Unlike extremity osteosarcomas which occur in the younger population, head and neck osteosarcomas are typically seen in patients in 3rd or 4th decade, and could be primary or secondary in the setting of prior radiation, fibrous dysplasia and Paget’s disease. All histological subtypes have been reported in the head and neck although the conventional type is the most common. Metastatic disease is uncommon and local recurrence is the major cause of morbidity and mortality. The imaging hallmarks of osteosarcomas include production of osteoid matrix, bone destruction, aggressive periosteal reaction and an associated soft-tissue mass (Case 1) [10, 12]. The osteoid matrix pattern exhibits an amorphous solid cloud-like or ivory-like density. Periosteal reaction with sunburst and Codman triangle appearances, classically seen in long bones, are rare in craniofacial osteosarcomas [12, 13]. Tumor matrix mineralization and calcifications can be identified on CT in more than half of cases [12]. At MRI, osteosarcomas are heterogenous tumors with nonspecific low to intermediate T1 and high T2 signal intensity. Unenhanced T1-weighted images are useful to identify medullary bone invasion as low-signal regions within normally hyperintense medullary fat.

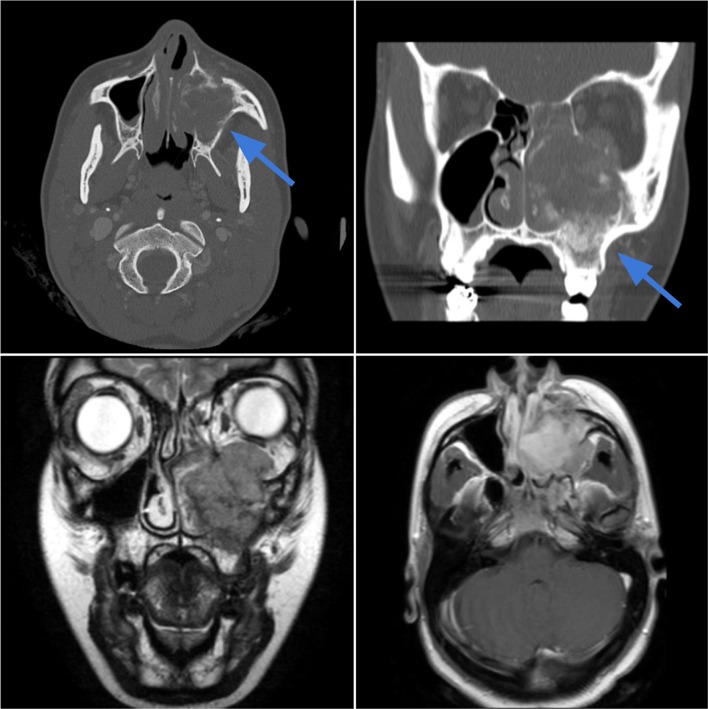

Case 1.

Osteosarcoma of the maxilla in a 36-year-old female with left upper molar pain, paresthesia, and progressive eyelid edema. Axial and coronal CT images (top left, top right) in bone window demonstrate a 5.0 cm left maxillary sinus soft-tissue mass with cloud-like osteoid matrix and aggressive cortical destruction of the maxillary walls and hard palate (blue arrows). The mass extends into the premaxillary soft tissues, buccal space, and left orbit. The mass demonstrates mixed heterogeneous signal intensity on T2-weighted image (bottom left) with heterogeneous enhancement (bottom right)

Chondrosarcomas are aggressive tumors arising from cartilage-producing cells that account for 20% of primary malignant bone tumors. The peak incidence is between 30 and 50 years, with a slight male predominance. Secondary chondrosarcomas may arise from pre-existing benign cartilaginous tumors such as enchondroma or osteochondroma, or in the setting of Paget’s disease or fibrous dysplasia. About 5–10% of tumors are located in the head and neck, where they are seen more commonly in the skull base, maxilla, nasal cavity, and larynx. Skull base lesions often localize at synchondroses and petroclival junction, often resembling clival chordomas. Two main subtypes include conventional and mesenchymal chondrosarcomas, and the following descriptions mainly refer to the conventional subtype. At CT, the chondroid matrix is seen as mixed lytic and sclerotic areas with a characteristic ring-and-arc or popcorn-like pattern (Case 2) [14]. High-grade lesions and de-differentiated chondrosarcomas demonstrate aggressive features of moth-eaten and permeative destruction. At MR, the lesions appear multilobulated with low to intermediate T1 and high T2 signal intensity, corresponding to non-calcified cartilage. Heterogeneous curvilinear septal or peripheral rim-like enhancement correspond to fibrovascular septations surrounding lobules of hyaline cartilage. Calcification can be identified on MR as stippled areas of low signal intensity [7].

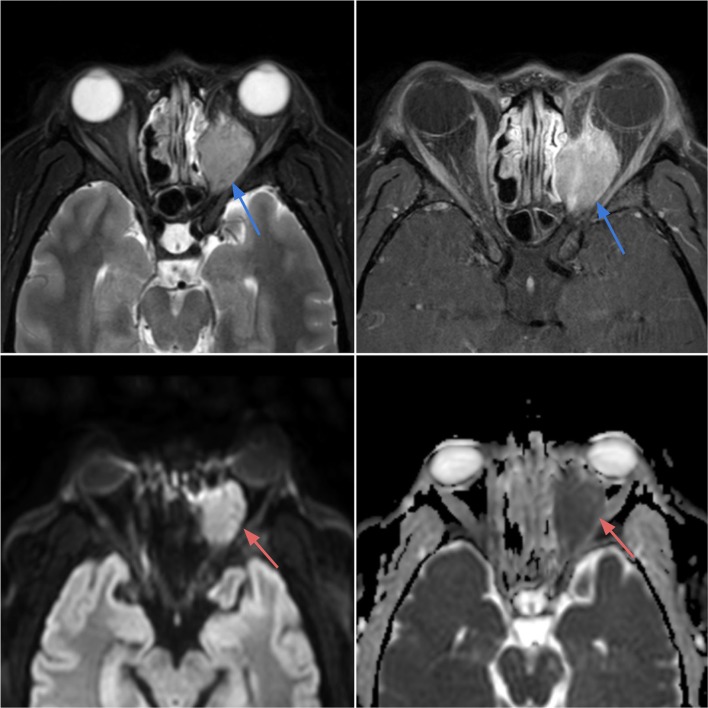

Case 2.

Chondrosarcoma of the larynx in an 80-year-old male with an incidental laryngeal mass found at intubation for knee surgery. Axial CT image in bone window (top left) demonstrates an expansile lesion with ring-and-arc chondroid-type calcifications (blue arrow) arising from the left cricoid cartilage with glottic and subglottic airway narrowing. On axial T2-weighted (top right), T1-weighted pre-contrast (bottom left) and T1-weighted post-contrast (bottom right) images, the lesion demonstrates a lobulated appearance with heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity, T1 hypointensity, and mild heterogeneous enhancement

Ewing sarcomas are aggressive malignant primary tumors of small round cell neuroectodermal origin that occur primarily in children and young adults with a slight male predominance. They are the second most common malignant bone tumors in children after osteosarcomas, with a predilection for the extremities, axial skeleton and pelvis. About 3–9% of cases arise in the head and neck, where they are more commonly seen in the calvarium, mandible and maxilla [15]. At CT, they appear as poorly marginated osteolytic lesions with bone expansion, cortical destruction and almost always a soft tissue mass (Case 3). Aggressive moth-eaten permeative lucency and laminated onion skin periostitis are classic findings [7, 14]. Calcification may be seen either within the intraosseous or soft tissue component, and some of it may represent spicules of destroyed bone. MRI features low to intermediate T1, intermediate to high T2 signal intensity, and restricted diffusion presumably due to the high cellularity. Enhancement is often diffuse, nodular or heterogenous along the periphery [7, 14] The differential for an aggressive lytic lesion in the head and neck in a child includes eosinophilic granuloma and metastatic neuroblastoma.

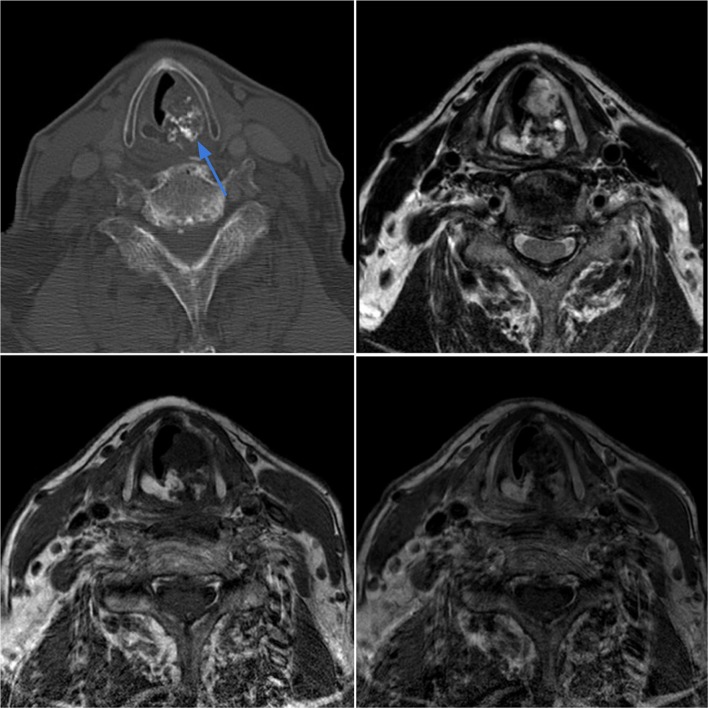

Case 3.

Ewing sarcoma of the left nasopharynx in a 3-year-old female with left ear pain and a visible oropharyngeal mass. Axial contrast-enhanced CT (top left) shows an infiltrative soft tissue mass in the left nasopharynx which displaces the nasal septum and invades the nasal cavity floor and roof of the soft palate. The lesion demonstrates intermediate T2 signal intensity (top right) with heterogeneous contrast enhancement on T1-weighted sequences (bottom images)

Liposarcomas (LPS) account for 10–35% of all soft tissue sarcomas, and approximately 4% occur in the head and neck [16]. The peak incidence is between 40 and 70 years, with a slight male predominance. The majority of tumors are found in the retroperitoneum and extremities. Only 2–6% occur in the head and neck, where they are most commonly seen in the larynx, pharynx or subcutaneous tissues of the neck and cheek [7, 17]. An important distinguishing imaging feature is the presence of adipose tissue, which is seen as fat attenuation on CT (− 70 HU), high signal intensity on T1-weighted images, intermediate signal on T2-weighted images, and show signal drop-out on fat-suppressed MR sequences. There is great imaging variability among the different histologic subtypes, depending on the degree of adipocytic differentiation. Well-differentiated LPS are well-circumscribed with predominantly adipose content. They can be distinguished from simple lipomas due to the presence of enhancing septa and non-lipomatous soft tissue [16]. Non-adipose elements measuring more than 1 cm raises concern for dedifferentiation (Case 4), typically exhibiting density similar to slightly lower than that of skeletal muscle, and signal intensity that is low to intermediate on T1- and intermediate to high on T2-weighted images. These changes are thought to represent varying degrees of myxoid, cellular or fibrous content within the dedifferentiated region [16]. Myxoid liposarcomas typically present as benign-appearing cystic mass on CT with marked T2 hyperintensity and brisk enhancement on MRI reflecting its myxoid matrix [16].

Case 4.

De-differentiated liposarcoma of the right upper neck in a 67-year-old male. Axial and coronal CT images in soft tissue window demonstrates a 6.0 × 3.7 cm soft tissue mass in the right submandibular and submental regions with a lateral component at near-fat attenuation (blue arrows) and a non-lipomatous medial component with attenuation slightly lower than that of skeletal muscle (red arrows)

Rhabdomyosarcomas are highly malignant tumors derived from undifferentiated skeletal muscle. They are the most common pediatric and adolescent soft tissue sarcoma but rarely occur in adults. About 35–50% occur in the head and neck especially in the parameningeal (nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, middle ear, mastoid and infratemporal fossa), non-parameningeal (tongue, palate, parotid and other sites) and orbital spaces [18, 19]. Parameningeal tumors have the worst prognosis given their location next to the vital structures, whereas non-parameningeal and orbital tumors have better prognosis. Four histological subtypes of rhabdomyosarcoma are recognized. The most common embryonal subtype (50%) typically occurs in the first decade, affecting the head and neck region and genitourinary system. Alveolar RMS (30%), is often seen adolescents in the extremities and in the peri-maxillary region in young adults. Pleomorphic RMS typically occurs in older adults involving the proximal extremity and the rare spindle cell–sclerosing subtype, which was added to the WHO classification in 2013, occurs in both children and adults [20]. On CT, they appear as ill-defined soft tissue lesions with homogeneous muscle attenuation, adjacent bone destruction and multi-compartmental spread [21, 22]. At MR, they present as bulky masses with low to intermediate T1 signal intensity that is similar to muscle and heterogeneous T2 signal that is hyperintense to muscle (Case 5) [7, 21]. Contrast enhancement is variable but often marked and heterogeneous [23]. Destruction of the adjacent bone is frequent, seen in approximately 25%, almost exclusively with tumors of the head and neck region [23–25]. Hemorrhage, necrosis and calcification are rare except in the pleomorphic subtype [21, 22]. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas present as infiltrative heterogenous soft tissue masses with moderately high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and prominent areas of necrosis [26]. Serpentine flow voids and lobulated architecture may also be present. Lymph node involvement is seen in 33–45% of patients with adult rhabdomyosarcoma and is most frequent with the alveolar subtype [27].

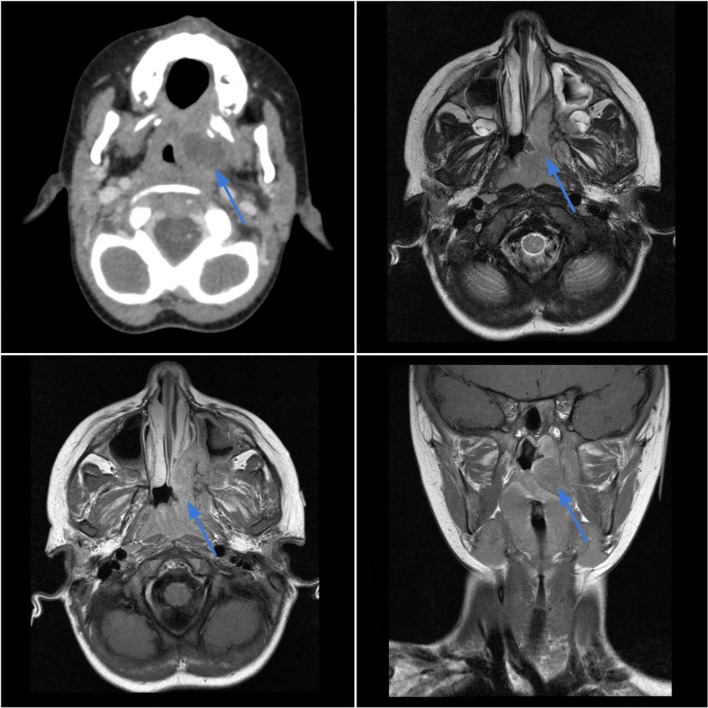

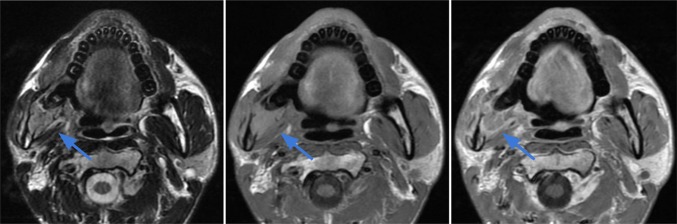

Case 5.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the left orbit in a 28-year-old female with blurry vision, proptosis and orbital pain with movement. Axial T2-weighted (top left) and T1 post-contrast (top right) images demonstrate a T2 heterogeneously hyperintense mass with avid enhancement within the left posterior orbit (blue arrows), with extraconal components eroding the medial orbital wall and extending into the nasal cavity. The mass exhibits bright signal on DWI (bottom left) and dark signal on ADC (bottom right) reflecting low diffusivity in keeping with the highly cellular tumor (red arrows)

Angiosarcomas are aggressive tumors with high rates of local recurrence and distant metastases. Angiosarcoma commonly occurs in the deep muscles of the lower extremities but can present in the head and neck, typically as cutaneous lesions in the face and scalp [28, 29]. Risk factors include chronic lymphedema, prior radiation therapy, and exposure to carcinogenic agents [7, 30]. Because of the infiltrative nature of the tumor and difficulty in obtaining wide surgical margins, local recurrence rates are high and prognosis is poor [30, 31]. On MRI, lesions are of intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, with marked, often heterogenous enhancement (Case 6) [7, 32]. Hemorrhage and necrosis may be seen in larger tumors [7, 32].

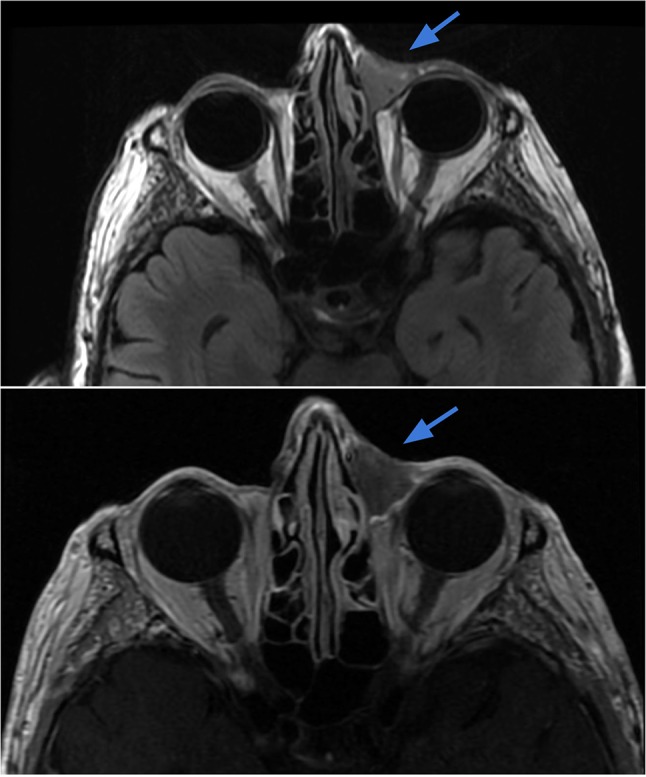

Case 6.

Angiosarcoma of the medial canthus region in a 70-year-old male. Axial T2-weighted (top image) and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (bottom) images demonstrate a mildly enhancing subcutaneous soft tissue lesion medial to the left orbit extending from the roof of the orbit to the left maxillary frontal process. The tumor abuts the globe and appears to contact the sclera

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was included in soft tissue sarcomas for the first time in the 2013 WHO classification (previously categorized as tumors of the skin) [20]. DFSP is a locally aggressive tumor of fibroblasts, comprising of 6% of soft tissue sarcomas. DFSP most commonly occurs in the third to fifth decade with slight male preponderance [33]. The most common sites of involvement are the trunk (50%), followed by proximal extremities (35–40%) and the head and neck (10–15%). DFSP arises in the dermis and can show infiltrative growth into the deep subcutaneous soft tissues. Local recurrence is common, seen in up to 20% of cases [33–35]. Although majority of the tumors are intermediate in grade and rarely metastasize, fibrosarcomatous transformation to higher grade with metastatic potential may occur in up to 20% of cases [36]. MR imaging demonstrates a lobular or nodular enhancing intermediate signal intensity lesion involving the subcutaneous fat and the skin, often causing a focal protuberance (Case 7) [34, 35]. Hemorrhage and necrosis are uncommon, except in fibrosarcomatous transformation [36].

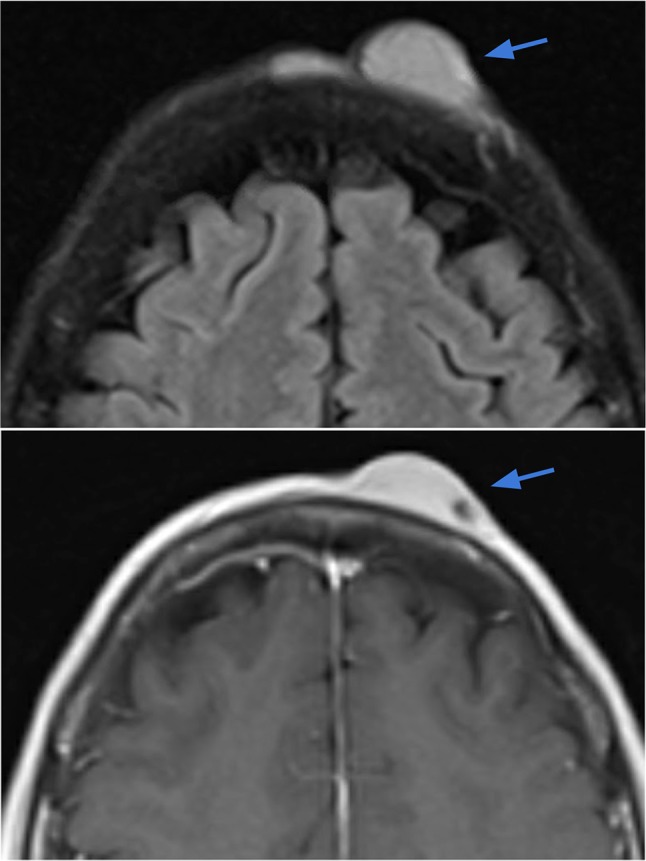

Case 7.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) of the scalp. Axial T2-weighted (right image) and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (left image) demonstrate a 2.6 × 0.8 cm circumscribed lentiform lesion with T2 hyperintensity and avid contrast enhancement within the left frontal scalp, extending up to the skin surface. The underlying periosteum along the outer table of the skull appears intact

Alveolar soft part sarcomas (ASPS) are extremely rare sarcomas, predominantly affecting the lower extremities but can occur in the head and neck especially in children and young adults [33]. The periorbital region and tongue are the most common sites in the head and neck [20, 37]. ASPS are highly vascular tumors often presenting as pulsating masses with bruits. On imaging, ASPS are usually well-circumscribed lobulated masses with nodular architecture, moderately high T1 and T2 signal intensity, and intense heterogenous contrast enhancement with central necrosis [40]. Large vessels at the periphery converging centrally, multiple flow voids, and high signal intensity on T1 are characteristic imaging features [38–41]. Although the appearance is similar to other aggressive soft tissue sarcomas, ASPS should be suggested when children or young adults present with a highly vascular mass, especially with concurrent lung metastases. ASPS has a high propensity for hematogenous metastases, most frequently to the lungs, bones and brain (Case 8) [40–42].

Case 8.

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) in the right mandible of a 29-year-old male. Axial T2 (left image), T1 (middle image) and T1 post contrast (right image) demonstrate a destructive lobulated T2 hyperintense and T1 hyperintense lesion centered in the right mandibular ramus, angle and posterior body with replacement of the normal marrow signal and associated cortical bone destruction. The extraosseous soft tissue mass extends medially into the masticator space

Conclusion

Sarcomas of the head and neck represent a small but diverse group of malignancies which are challenging to diagnose based on imaging findings alone. Knowledge of the clinical presentation, typical locations, and classic features on each imaging modality is essential in formulating the differential diagnosis. When imaging findings are nonspecific or nondiagnostic, the recognition of indolent versus aggressive features is key in the decision to obtain tissue for definitive diagnosis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Burningham Z, Hashibe M, Spector L, Schiffman J. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiller CA, Trama A, Serraino D, Rossi S, Navarro C, Chirlaque MD, Casali PG. Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):664–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockstein B. Management of sarcomas of the head and neck. Curr Oncol Rep. 2004;6(4):321–327. doi: 10.1007/s11912-004-0043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sturgis EM, Potter BO. Sarcomas of the head and neck region. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15(3):239–252. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Schepper AM, Bloem JL. Soft tissue tumors: grading, staging, and tissue-specific diagnosis. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;18(6):431–444. doi: 10.1097/rmr.0b013e3181652220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rijswijk CS, Geirnaerdt MJ, Hogendoorn PC, et al. Soft-tissue tumors: value of static and dynamic gadopentetate dimeglumine–enhanced MR imaging in prediction of malignancy. Radiology. 2004;233(2):493–502. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razek AA, Huang BY. Soft tissue tumors of the head and neck: imaging-based review of the WHO classification. Radiographics. 2011;31(7):1923–1954. doi: 10.1148/rg.317115095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastiaannet E, Groen H, Jager PL, et al. The value of FDG-PET in the detection, grading and response to therapy of soft tissue and bone sarcomas; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(1):83–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tshering Vogel DW, Thoeny HC. Cross-sectional imaging in cancers of the head and neck: how we review and report. Cancer Imaging. 2016;16(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s40644-016-0075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandell J. Core radiology: a visual approach to diagnostic imaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendenhall WM, Fernandes R, Werning JW, Vaysberg M, Malyapa RS, Mendenhall NP. Head and neck osteosarcoma. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg. 2010;32(6):597–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YY, Van Tassel P, Nauert C, Raymond AK, Ediken J. Craniofacial osteosarcomas: plain film, CT and MR findings in 46 cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 1988;9:379–385. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkordy MA, ElBaradie TS, Elsebai HI, et al. Osteosarcoma of the jaw: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;30(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scelsi C, Wang A, Garvin C, Bajaj M, Forseen S, Gilbert B. Head and neck sarcomas: a review of clinical and imaging findings based on the 2013 World Health Organization classification. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;212(3):1–11. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juergens H, Grevener K, Dirksen U, Ranft A. Ewing sarcoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):E20516. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphey MD, Arcara LK, Fansburg-Smith J. Imaging of musculoskeletal liposarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1371–1395. doi: 10.1148/rg.255055106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis EC, Ballo MT, Luna MA, et al. Liposarcoma of the head and neck: the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Head Neck. 2009;31(1):28–36. doi: 10.1002/hed.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Neill JP, Bilsky MH, Kraus D. Head and neck sarcomas: epidemiology, pathology, and management: epidemiology, pathology, and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Lee MS, Lee BH, Choe DH, Do YS, Kim KH, Cho KJ. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in adults: MR and CT findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(10):1923–1928. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Zhang J, Tang G, Hu S, Zhou G, Liu Y, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging observations of rhabdomyosarcoma in the head and neck. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(1):155–160. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagiwara A, Inoue Y, Nakayama T, Yamato K, Nemoto Y, Shakudo M, et al. The “botryoid sign”: a characteristic feature of rhabdomyosarcomas in the head and neck. Neuroradiology. 2001;43(4):331–335. doi: 10.1007/s002340000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez DP, Orscheln ES, Koch BL. Masses of the nose, nasal cavity, and nasopharynx in children. Radiographics. 2017;37(6):1704–1730. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen SD, Moskovic EC, Fisher C, Thomas JM. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma: cross-sectional imaging findings including histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(2):371. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freling NJ, Merks JH, Saeed P, et al. Imaging findings in craniofacial childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1723–1738. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1787-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousem DM, Lexa FJ, Bilaniuk LT, Zimmerman RI. Rhabdomyosarcomas in the head and neck: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 1990;177:683–686. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saboo SS, Krajewski KM, Zukotynski K, Howard S, Jagannathan JP, Hornick JL, et al. Imaging features of primary and secondary adult rhabdomyosarcoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(6):W694–W703. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Vliet M, Kliffen M, Krestin GP, van Dijke CF. Soft tissue sarcomas at a glance: clinical, histological, and MR imaging features of malignant extremity soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1499–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gründahl JE, Hallermann C, Schulze HJ, Klein M, Wermker K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of head and neck: a new predictive score for locoregional metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel SH, Hayden RE, Hinni ML, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: the Mayo Clinic experience. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:335–340. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullins B, Hackman T. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19(3):191–195. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chikarmane SA, Gombos EC, Jagadeesan J, Raut C, Jagannathan JP. MRI findings of radiation-associated angiosarcoma of the breast (RAS) J Magn Reson Imaging (JMRI) 2015;42(3):763–770. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torreggiani WC, Khalid AI, Munk PL, Nicolau S, O’Connell JX, Knowling MA. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans MR imaging features. AJR. 2002;178:989–993. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.4.1780989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Millare GG, Guha-Thakurta N, Sturgis EM, El- Naggar AK, DebnAm JM. Imaging findings of head and neck dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. AJNR. 2014;35:373–378. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoesly PM, Lowe GC, Lohse CM, Brewer JD, Lehman JS. Prognostic impact of fibrosarcomatous transformation in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(3):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarville MB, Muzzafar S, Kao SC, et al. Imaging features of alveolar soft-part sarcoma: a report from Children’s Oncology Group study ARST0332. AJR. 2014;203:1345–1352. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HS, Lee HK, Weon YC, Kim HJ. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the head and neck: clinical and imaging features in five cases. AJNR. 2005;26:1331–1335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suh JS, Cho J, Lee SH, Shin KH, Yang WI, Lee JH, et al. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: MR and angiographic findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(12):680–689. doi: 10.1007/s002560000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian L, Cui CY, Lu SY, Cai PQ, Xi SY, Fan W. Clinical presentation and CT/MRI findings of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a retrospective single-center analysis of 14 cases. Acta Radiol. 2016;57(4):475–480. doi: 10.1177/0284185115597720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viry F, Orbach D, Klijanienko J, Freneaux P, Pierron G, Michon J, et al. Alveolar soft part sarcoma-radiologic patterns in children and adolescents. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43(9):1174–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00247-013-2667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sood S, Baheti AD, Shinagare AB, Jagannathan JP, Hornick JL, Ramaiya NH, et al. Imaging features of primary and metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma: single institute experience in 25 patients. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1036):20130719. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]