Abstract

Background

Epigenetics could facilitate greater understanding of disparities in the emergence of childhood obesity. While blood is a common tissue used in human epigenetic studies, saliva is a promising tissue. Our prior findings in non-obese preschool-aged Hispanic children identified 17 CpG dinucleotides for which differential methylation in saliva at baseline was associated with maternal obesity status. The current study investigated to what extent baseline DNA methylation in salivary samples in these 3–5-year-old Hispanic children predicted the incidence of childhood obesity in a 3-year prospective cohort.

Methods

We examined a subsample (n = 92) of Growing Right Onto Wellness (GROW) trial participants who were randomly selected at baseline, prior to randomization, based on maternal phenotype (obese or non-obese). Baseline saliva samples were collected using the Oragene DNA saliva kit. Objective data were collected on child height and weight at baseline and 36 months later. Methylation arrays were processed using standard protocol. Associations between child obesity at 36 months and baseline salivary methylation at the previously identified 17 CpG dinucleotides were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

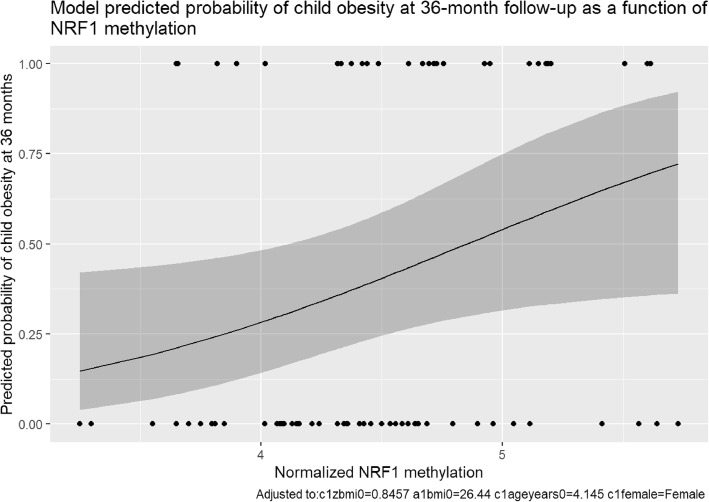

Among the n = 75 children eligible for analysis, baseline methylation of Cg1307483 (NRF1) was significantly associated with emerging childhood obesity at 36-month follow-up (OR = 2.98, p = 0.04), after adjusting for child age, gender, child baseline BMI-Z, and adult baseline BMI. This translates to a model-estimated 48% chance of child obesity at 36-month follow-up for a child at the 75th percentile of NRF1 baseline methylation versus only a 30% chance of obesity for a similar child at the 25th percentile. Consistent with other studies, a higher baseline child BMI-Z during the preschool period was associated with the emergence of obesity 3 years later, but baseline methylation of NRF1 was associated with later obesity even after adjusting for child baseline BMI-Z.

Conclusions

Saliva offers a non-invasive means of DNA collection and epigenetic analysis. Our proof of principle study provides sound empirical evidence supporting DNA methylation in salivary tissue as a potential predictor of subsequent childhood obesity for Hispanic children. NFR1 could be a target for further exploration of obesity in this population.

Keywords: Obesity, Hispanic children, Epigenetics, Methylation, Saliva

Background

The prevalence of pediatric obesity has been increasing at an alarming rate in the last forty years [1, 2]. Although pediatric obesity prevalence is a global issue, the United States is facing epidemic levels of pediatric obesity [3, 4]. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that the prevalence of obesity among children aged 2–19 years old has risen from 13.9% in 2000 to 18.5% in 2016 [5]. However, some ethnic groups have an even higher obesity prevalence [1, 6]. For example, the 2015–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reported 25.8% of Hispanic 2–19 year-olds were obese compared to 14.1% of their non-Hispanic white counterparts [7]. Identifying what influences different populations is critical to successfully reducing obesity-related health disparities.

Childhood is a particularly sensitive period for neurological, endocrine, and metabolic development. For example, obesity at a young age contributes to an increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood [8–10]. Recent literature indicates that susceptibility to obesity within an “obesogenic” environment differs among individuals [11, 12]. It is not clear what mechanisms are responsible for obesity variation, but many studies identify a dynamic interaction of genetic and environmental exposures at sensitive periods of development [13, 14]. While monogenic DNA mutations exist and are associated with obesity, common forms of childhood obesity have frustrated the scientific community with the so-called problem of missing heritability. It appears that obesity is a multi-trait, multi-state phenotype. The field of epigenetics, modifications that affect transcriptional plasticity, might offer insights into the emerging phenotype of childhood obesity. Epigenetic patterns, often measured by DNA methylation, change rapidly in response to environmental factors such as nutrition and physical activity and are specifically vulnerable to changes during early childhood development. Moreover, epigenetic patterns vary between ethnic groups and could explain differing susceptibility to early emerging obesity and its commonly associated later chronic diseases [15–18].

Epigenetic patterns are tissue-dependent. While blood is a common tissue used in studies of human epigenetic changes, saliva is also a promising tissue. Saliva could be particularly valuable in studying pediatric populations given the ease of tissue access, cost-efficiency, and the ability to collect it in multiple settings [19, 20]. Abraham and colleagues illustrated that when comparing DNA fragmentation, quality, and genotype concordance, saliva is comparable to blood samples [21]. When examining methylation patterns, both saliva and blood reliably assess epigenetic modifications [22]. In comparing the collection of blood and saliva samples, saliva collection is associated with lower infection rates, decreased cost, increased patient acceptance, and higher participant compliance [23]. Saliva also has the advantage of offering insight into the gastrointestinal tract, which could be useful when examining obesity. The ease of saliva collection coupled with DNA fidelity could allow for a more practical source of DNA collection for children. Given that salivary tissue is used less often for epigenetic studies, this approach is novel.

Recently, Oelsner et al. examined 92 saliva samples from 3 to 5-year-old Hispanic children who were at risk for obesity but not yet obese and analyzed 936 genes previously associated with obesity [24]. The cross-sectional study identified 17 CpG dinucleotides that demonstrated an association between baseline differential child DNA methylation and maternal BMI (obese versus non-obese). While this analysis was conducted on baseline saliva samples, these children subsequently participated in a three-year longitudinal study where more than a third of children became obese. The current study investigates to what extent baseline child salivary DNA methylation patterns were associated with the emerging incidence of childhood obesity in this 3-year prospective cohort of young Hispanic children [25].

Methods

Informed consent

Trained, bilingual study staff administered written consents to the parent or legal guardian of the child of interest in the language of their choice (English or Spanish). The parent or legal guardian provided consent for both themselves and their child. Because this was a low health literacy population, the consenting process utilized specific measures to ensure participant understanding including a “teach-back” method and protocol visual aids [26]. The study was approved by Vanderbilt University Review Board (IRB No. 120643).

Sample population study subjects

We examined a subsample (n = 92) of Growing Right Onto Wellness (GROW) trial participants [24]. They were randomly selected at baseline, before randomization, based on maternal phenotype. One group of children had obese mothers (BMI ≥30 and waist circumference ≥ 100 cm), and the other had non-obese mothers (BMI < 30 and waist circumference < 100 cm). The two groups were matched on child age and gender. The current study examines this subsample as a prospective cohort, after a 3-year follow-up.

Child participant eligibility criteria in the original GROW study included: 3–5 years old, no known medical conditions, and being at risk for obesity (high normal weight or overweight) but not yet obese (BMI ≥50th and < 95th percentile). Three children were excluded due to being obese at baseline. Parent eligibility criteria included: ≥18 years old, signed written consent to participate in a 3-year trial, consistent phone access, spoke English or Spanish, and no known medical conditions that would preclude routine physical activity. Families were recruited from East Nashville and South Nashville. All parents self-reported that at least one person in their household was eligible to participate in a program that qualified them as underserved. The underserved programs included but were not limited to TennCare (Medicaid), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), CoverKids, Food Stamps, and/or reduced-price school meals [25]. To be eligible for analysis in the epigenetic study reported here, child BMI must have been collected at the 36-month follow-up (n = 75).

Saliva collection and assay method

Baseline saliva samples from children were collected voluntarily from interested participants using a separate consenting form in the participant’s language of choice. Saliva was collected from children at baseline using the Oragene DNA saliva kit. Children were asked to fast for 30 min and rinse their mouths with water immediately before collection. Two mL of saliva was collected from children using saliva sponges, inserted between the cheek and gums in the upper cheek pouch without swabbing the buccal mucosa. Samples were collected at home or in community centers. To ensure safety and decrease contamination, trained sample collectors wore gloves and capped the samples as soon as the saliva was collected. After samples were properly collected and labeled, the samples were sent to the Vanderbilt Technology for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE) core at Vanderbilt University. DNA was then extracted from the saliva using the PrepIT L2P reagent with guidance from DNA Genotek’s recommendations and stored at − 80 degrees Centigrade.

Anthropometric data

Objective height and weight for parent-child pairs were collected and used to calculate BMI (kg/m2) at baseline and 36 months. Trained research staff collected weight and height of participants using standard anthropometric procedures, and participants wore only light clothing and no shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Perspective Enterprise, Portage, MI), and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated scale. BMI measurements were collected using the trial protocol [27]. BMI-Z was calculated based on each child’s BMI, gender, and age, and BMI categories were defined using CDC guidelines: normal weight (<85th percentile); overweight (≥85th and < 95th percentile); and obese (≥95th percentile).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to evaluate baseline differences. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to evaluate baseline differences.

Genome-wide DNA methylation was conducted on the 92 saliva samples using the Infinium Illumina HumanMethylation 450 K BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Methylation arrays were processed using a standard protocol [24, 28] and quality control was done using the Methylation module (V1.9.0). Samples with a call rate lower than 98% were excluded, resulting in the removal of one sample (total baseline eligible sample n = 91). The Background Subtraction method [29] was used for methylation array normalization. In this method, the average signals of built-in negative controls represent background noise and are subtracted from all probe signals to make unexpressed targets equal to zero. Outliers were removed using the median absolute deviation method. Lastly, the normalized values were log-transformed and multiplied by 10 to put degree of methylation on a continuous scale from 0 to 10 for statistical analysis.

Associations between child obesity at 36 months and baseline methylation levels were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression models. Other variables were included in the models as covariates, including child age, child baseline BMI-Z, child gender, and parent baseline BMI. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using R software (www.r-project.org) version 3.5.0.

Results

Of the original 92 participants in the baseline subsample, 75 met quality control and eligibility requirements and were included for analysis. The mean age was 4.3 years (SD = 0.8), and the mean baseline BMI was 16.7 (SD = 0.8). Within the analytic sample, at baseline, 64.0% (n = 48) were normal weight, and 36.0% (n = 27) were overweight, and 73.3% (n = 55) were Hispanic-Mexican. Among parents, 48.0% (n = 36) were obese (stratified by design for this subsample). Refer to Table 1 for further baseline demographic descriptions of the sample. At the study’s conclusion, 37% (n = 28) of children were obese.

Table 1.

Demographics of Sample Populationa

| Child Characteristics | Total (n = 75) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 (46.7%) |

| Female | 40 (53.3%) |

| Age at anthropometry collection (years) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| Age category (years) | |

| 3 | 34 (45.3%) |

| 4 | 26 (34.7%) |

| 5 | 15 (20.0%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.7 (0.8) |

| BMI-Z | 0.9 (0.5) |

| BMI category | |

| Normal weight | 48 (64.0%) |

| Overweight | 27 (36.0%) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 53.4 (3.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic Mexican | 55 (73.3%) |

| Hispanic non-Mexican | 20 (26.7%) |

| Parent Characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 32.0 (5.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 (7.3) |

| BMI category | |

| Normal weight | 28 (37.3%) |

| Overweight | 11 (14.7%) |

| Obese | 36 (48.0%) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.9 (16.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, BMI-Z BMI z-score

a Values are mean (SD) or frequency (percent)

Comparing children who were non-obese at 36 months (n = 47) to those who were obese at 36 months (n = 28), there were no statistically significant differences in baseline child characteristics, although, descriptively, baseline weight-related characteristics appeared to be lower in children who were not obese at follow-up. Parents did not have any significantly different baseline characteristics between the two groups, although mean age was descriptively slightly younger in parents of children who became obese at 36 months (33.0 vs. 30.4) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Child Obesity Status at 36 monthsa

| Child Characteristics | Child not obese at 36 months (n = 47) | Child obese at 36 months (n = 28) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.32 | ||

| Male | 24 (51.1%) | 11 (39.3%) | |

| Female | 23 (48.9%) | 17 (60.7%) | |

| Age at anthropometry collection (years) | 4.3 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.8) | 0.90 |

| Age category (years) | 0.93 | ||

| 3 | 21 (44.7%) | 13 (46.4%) | |

| 4 | 17 (36.2%) | 9 (32.1%) | |

| 5 | 9 (19.1%) | 6 (21.4%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.6 (0.7) | 16.9 (0.8) | 0.06 |

| BMI-Z | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.06 |

| BMI category | 0.05 | ||

| Normal weight | 34 (72.3%) | 14 (50.0%) | |

| Overweight | 13 (27.7%) | 14 (50.0%) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 52.9 (2.6) | 54.3 (3.6) | 0.13 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.41 | ||

| Hispanic Mexican | 36 (76.6%) | 19 (67.9%) | |

| Hispanic non-Mexican | 11 (23.4%) | 9 (32.1%) | |

| Parent Characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 33.0 (5.2) | 30.4 (6.0) | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.2 (7.4) | 29.7 (7.3) | 0.88 |

| BMI category | 0.67 | ||

| Normal weight | 18 (38.3%) | 10 (35.7%) | |

| Overweight | 8 (17.0%) | 3 (10.7%) | |

| Obese | 21 (44.7%) | 15 (53.6%) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.0 (16.2) | 99.3 (16.1) | 0.47 |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, BMI-Z BMI z-score

a Values are mean (SD) or frequency (percent)

b Wilcoxon rank-sum test used for continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-squared used for categorical variables

Table 3 describes the associations between children’s continuous degree of baseline methylation at each CpG dinucleotide and childhood obesity at 36 months for the 75 children with follow-up data. The multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for child gender, baseline age, baseline BMI-Z, and adult baseline BMI. After accounting for these covariates, higher baseline methylation of cg01307483 (NRF1) was significantly associated with a higher probability of childhood obesity at 36 months (odds ratio = 2.98, 95% CI = [1.06, 8.38], p = 0.04). PPARGC1B methylation was potentially associated with decreased obesity at 36 months but was not statistically significant. SORCS2 methylation was not statistically significant for cg03218460 or cg18431297 [30, 31].

Table 3.

Association of Baseline Methylationa at Each CpG Dinucleotide With Child Obesity Status at 36-Month Follow-Up

| Unique CpG Dinucleotide | Associated Gene | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg21790991 | FSTL1 | 1.35 | [0.88, 2.06] | 0.16 | Regulate endothelial cell function and vascular remodeling in response to hypoxic ischemia [30, 40] |

| cg03218460 | SORCS2 | 2.08 | [0.83, 5.21] | 0.12 | Functions to regulate fasting insulin levels and secretion of insulin, diabetes susceptibility [41, 42] |

| cg23241637 | ZNF804A | 1.47 | [0.61, 3.49] | 0.39 | Schizophrenia [43, 44] |

| cg04798490 | SHANK2 | 1.51 | [0.6, 3.8] | 0.38 | Autism [45, 46] |

| cg01307483 | NRF1 | 2.98 | [1.06, 8.38] | 0.04* | Innate immune response governing adipocyte inflammation, cytokine expression, and insulin resistance [34–36] |

| cg19312314 | CBS | 0.75 | [0.27, 2.13] | 0.59 | Catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to cystathionine, associated with homocystinuria and hydrogen sulfide production [47] |

| cg14321859 | DLC1 | 1.82 | [0.69, 4.81] | 0.23 | Regulates Rho GTP-binding proteins, cytoskeletal signaling, tumor suppressor, adipocyte differentiation [48, 49] |

| cg03067613 | ATP8B3 | 1.24 | [0.4, 3.8] | 0.71 | Reproduction [37] |

| cg11296553 | CEP72 | 0.99 | [0.03, 32.38] | 0.99 | Ulcerative colitis [38] |

| cg16509445 | CRYL1 | 1.04 | [0.23, 4.63] | 0.96 | Heptocellular carcinoma [50] |

| cg16344026 | PPARGC1B | 0.27 | [0.04, 2.04] | 0.21 | Fat oxidation, non-oxidative glucose metabolism, and energy regulation, ubiquitous in duodenum and small intestines [51, 52] |

| cg15354625 | ODZ4 | 0.78 | [0.12, 4.94] | 0.79 | Bipolar disorder [53] |

| cg23836542 | CHN2 | 1.13 | [0.14, 9.07] | 0.91 | Encodes GTP-metabolizing protein that regulates cell proliferation and migration, insulin resistance [54, 55] |

| cg07511564 | NXPH1 | 1.02 | [0.34, 3.03] | 0.97 | Forms a tight complex with alpha neurexins, promoting adhesion between dendrites and axons, diabetic neuropathy [56, 57] |

| cg18799510 | GRIN3A | 1.02 | [0.32, 3.28] | 0.98 | Schizophrenia [31, 58] |

| cg14996807 | UNC13A | 3.17 | [0.64, 15.76] | 0.16 | ALS [59, 60] |

| cg18431297 | SORCS2 | 1.01 | [0.51, 1.99] | 0.98 | Neuropeptide receptor activity, strongly expressed in the central nervous system, acts with IGF1 in the setting of cardiovascular disease [42, 61] |

a Degree of methylation was a continuous variable calculated by log-transforming the normalized values and multiplying by 10 to put it on a scale from 0 to 10 (see Methods section)

In the logistic regression model analyzing the NRF1 dinucleotide, child gender, child baseline age, and baseline parent BMI, were not significant predictors of childhood obesity at 36 months (Table 4). However, in this model, child baseline BMI-Z and baseline differential methylation of NRF1 were significant predictors of childhood obesity at 36 months. Figure 1 displays the model-predicted probability of child obesity at 36-month follow-up as a function of increasing NRF1 methylation. Child baseline BMI-Z was a significant predictor in all but two CpG dinucleotide models (odds ratio = 3.09–4.08, p < 0.05). Median degree of baseline methylation at each CpG dinucleotide examined in this study is shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Table 4.

Association of baseline differential DNA methylationa with obesity at 36 months, adjusted for co-variates

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Baseline BMI-Z | 3.25 | [1.00, 10.50] | 0.049 |

| Baseline age | 1.50 | [0.76, 2.94] | 0.24 |

| Gender (male) | 0.59 | [0.21, 1.63] | 0.31 |

| Parent | |||

| Baseline BMI | 0.99 | [0.92, 1.07] | 0.86 |

| CpG Baseline Methylation | |||

| Cg10307483 (NRF1) | 2.98 | [1.06, 8.38] | 0.04 |

a Degree of methylation was a continuous variable calculated by log-transforming the normalized values and multiplying by 10 to put it on a scale from 0 to 10 (see Methods section)

Fig. 1.

Model Predicted Probability of Child Obesity at 36-month Follow-up as a Function of NRF1 Methylation. Figure 1 displays the logistic regression model-predicted probability of child obesity at 36 months as a function of the degree of methylation of cg01307483 (NRF1). The solid line indicates the predicted probability, and the gray shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval. As the degree of methylation of NRF1 increases, the probability of child obesity at 36 months increases significantly

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study that investigates DNA methylation collected via salivary samples as a predictor of childhood emerging obesity among 3–5-year-old Hispanic children. Although other studies have investigated DNA methylation patterns in children who are already obese, our prospective study investigated how these patterns might be used to predict the future emergence of obesity in non-obese preschool-aged children above and beyond what is provided by their age, gender, baseline BMI-Z, and their mother’s BMI. After adjusting for these covariates, baseline methylation of Cg1307483 (NRF1) was significantly associated with emerging childhood obesity at 36-month follow-up with a significant positive odds ratio (OR = 2.98, p = 0.04). To place this odds ratio finding into context and enhance interpretation, the model estimated a 48% chance of child obesity at 36-month follow-up for a child at the 75th percentile of NRF1 methylation versus only a 30% chance of obesity for a similar child at the 25th percentile.

Consistent with other studies, a higher baseline child BMI-Z during the preschool period was associated with the emergence of obesity 3 years later, but baseline methylation of NRF1 was associated with later obesity even after adjusting for baseline BMI-Z. NRF1 is associated with the innate immune response governing adipocyte inflammation and cytokine expression, as well as brown adipose tissue thermogenic adaption. It also plays a role in insulin resistance [34–36]. The current results build on the existing literature by demonstrating that DNA methylation of a critical CpG dinucleotide within the NRF1 gene in 3–5-year-old non-obese children is associated with the emergence of obesity 3 years later. This provides a potential target of further investigation and suggests that adipocyte inflammation might already be affected before the phenotypic emergence of childhood obesity in Hispanic children. Other studies demonstrate that early life exposures can affect later health and disease outcomes. This life-course understanding of emerging phenotypes might contribute to health disparities.

It is important to note that prior studies implicated NRF1 associated with existing obesity and young Hispanic children using blood and skeletal muscle samples as well [36]. Comuzzie and colleagues investigated chromosome 7q in Hispanic children and found unique loci contributing to pediatric obesity [33]. As in our study, the genes significantly associated with obesity suggest a strong inflammatory influence. While our study does not confirm this hypothesis, it does provide supplemental data supporting this theory. Because NRF1 is a major transcription factor in metabolic regulation and stimulates the expression of PPARGC1B, these look like promising targets for further research and intervention approaches. Although direct comparisons between saliva and blood cannot be made in the current study, the fact that we noted the same association in saliva as found in blood and skeletal muscle further bolsters support for the use of saliva as a useful tissue for epigenetic inquiry.

Other genes could also play an important role in both predicting later obesity and understanding the pathways that lead to obesity. For example, PPARGC1B methylation had a potentially strong association with decreased obesity at 36 months but was not statistically significant. PPARGC1B is associated with fat oxidation, non-oxidative glucose metabolism, and energy regulation [37, 38]. Similarly, SORCS2 methylation, which functions to regulate fasting insulin levels and secretion of insulin, was potentially associated with increased obesity at 36 months but was not statistically significant in this relatively small sample [31, 39]. Repeating this work in a larger sample is necessary for further understanding these and other epigenetic contributions to the early emergence of obesity in populations who experience higher health disparities associated with obesity. Moreover, while the small analytic sample size precluded moderation analysis in the current study, it would be interesting for future research to explore whether the potential relationships between methylation and subsequent obesity status depend on initial BMI status or other potential moderators of interest (e.g., gender, ethnicity, income, etc.).

To-date, many epigenetic studies have focused on the exploration of molecular pathways. While it is not yet known if these DNA methylation patterns can be used as biomarkers, our study provides a proof-of-principle demonstrating that even in non-obese Hispanic children, some differential methylation patterns are associated with the later emergence of obesity. While it is clear that susceptibility to obesity within an “obesogenic” environment varies among individuals, it is not clear why. This line of epigenetic inquiry using saliva as an accessible tissue for pediatric study holds promise for guiding further exploration in both understanding and intervening before the emergence of childhood obesity.

Although NFR1 was significantly related to child obesity at 36-month follow-up, the relatively small sample size analyzed in this study might have contributed to a failure to detect important relationships for the other CpG dinucleotides. Expanding the current analysis to include larger sample sizes would help to confirm and validate the findings. While there was a strict collection protocol for saliva collection, contamination and human collection error are possible when collecting salivary DNA. Although previous literature indicates DNA methylation in saliva and blood samples are similar, the current study only investigated methylation patterns in saliva and cannot be used to make direct comparisons to blood. Furthermore, although this sample yields insight into Hispanic 3–5-year-olds, DNA methylation patterns should be studied in children of various ages and race/ethnicities.

Conclusions

Saliva offers a non-invasive means of DNA collection and epigenetic analysis. This proof of principle study provides empirical evidence supporting the idea that DNA methylation assessed using salivary tissue collected in non-obese children could be used as an important predictor of childhood obesity 3 years later. NFR1 could be a target for further exploration of obesity in Hispanic children.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. CpG Dinucleotide Methylation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the participation of the Hispanic families involved in this study.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BMI-Z

Body Mass Index Z-score

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- GROW

The Growing Right Onto Wellness Trial

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- VANTAGE

The Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics

- WIC

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed experiment: SB, AR; Analyzed the data: SZ, ES; Wrote the paper: SB, AR, SZ, ES, EP. All authors edited and proofed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants (U01 HL103620) with additional support for the remaining members of the COPTR Consortium (U01HL103622, U01HL103561, U01HD068890, U01HL103629) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Institute of Child Health and Development. This research was also supported by grants 5P30DK092986–03 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and 5UL1TR0045 from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR). The NHLBI and NICHD played an advisory role in all phases of the study, including the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The genetic dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series access number GSE72556 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE72556).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data were collected after written informed consent was obtained by parent/legal guardian. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 120643).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amanda Rushing, Email: arushi@lsuhsc.edu.

Evan C. Sommer, Email: evan.c.sommer@vumc.org

Shilin Zhao, Email: shilin.zhao.1@vumc.org.

Eli K. Po’e, Email: eli.poe@vumc.org

Shari L. Barkin, Email: shari.barkin@vumc.org

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12881-020-0968-7.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2410–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25. doi: 10.1080/17477160600586747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;288:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: questionnaires, datasets, and related documents. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes. Accessed 1 Jan 2019.

- 8.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsen TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1802–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kit BK, Kuklina E, Carroll MD, Ostchega Y, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Prevalence of and trends in dyslipidemia and blood pressure among US children and adolescents, 1999-2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):272–279. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation. 2008;117(25):3171–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois L, Ohm Kyvik K, Girard M, Tatone-Tokuda F, Perusse D, Hjelmborg J, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to weight, height, and BMI from birth to 19 years of age: an international study of over 12,000 twin pairs. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchard L, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Faraj M, Lavoie ME, Mill J, Perusse L, et al. Differential epigenomic and transcriptomic responses in subcutaneous adipose tissue between low and high responders to caloric restriction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(2):309–320. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrera BM, Keildson S, Lindgren CM. Genetics and epigenetics of obesity. Maturitas. 2011;69(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey KM, Sheppard A, Gluckman PD, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, McLean C, et al. Epigenetic gene promoter methylation at birth is associated with child's later adiposity. Diabetes. 2011;60(5):1528–1534. doi: 10.2337/db10-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg Z, Feil R, Constancia M, Fraga M, Junien C, Carel JC, et al. Child health, developmental plasticity, and epigenetic programming. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(2):159–224. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamtani M, Kulkarni H, Dyer TD, Goring HH, Neary JL, Cole SA, et al. Genome- and epigenome-wide association study of hypertriglyceridemic waist in Mexican American families. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:6. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni H, Kos MZ, Neary J, Dyer TD, Kent JW, Jr, Goring HH, et al. Novel epigenetic determinants of type 2 diabetes in Mexican-American families. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(18):5330–5344. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King K, Murphy S, Hoyo C. Epigenetic regulation of Newborns' imprinted genes related to gestational growth: patterning by parental race/ethnicity and maternal socioeconomic status. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(7):639–647. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshizawa JM, Schafer CA, Schafer JJ, Farrell JJ, Paster BJ, Wong DT. Salivary biomarkers: toward future clinical and diagnostic utilities. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(4):781–791. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonne NJ, Wong DT. Salivary biomarker development using genomic, proteomic and metabolomic approaches. Genome Med. 2012;4(10):82. doi: 10.1186/gm383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham JE, Maranian MJ, Spiteri I, Russell R, Ingle S, Luccarini C, et al. Saliva samples are a viable alternative to blood samples as a source of DNA for high throughput genotyping. BMC Med Genet. 2012;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langie SAS, Moisse M, Declerck K, Koppen G, Godderis L, Vanden Berghe W, et al. Salivary DNA methylation profiling: aspects to consider for biomarker identification. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;121(Suppl 3):93–101. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffe T, Cooper-White J, Beyerlein P, Kostner K, Punyadeera C. Diagnostic potential of saliva: current state and future applications. Clin Chem. 2011;57(5):675–687. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.153767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oelsner KT, Guo Y, To SB. Non AL, Barkin SL. Maternal BMI as a predictor of methylation of obesity-related genes in saliva samples from preschool-age Hispanic children at-risk for obesity. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Po'e EK, Heerman WJ, Mistry RS, Barkin SL. Growing right onto wellness (GROW): a family-centered, community-based obesity prevention randomized controlled trial for preschool child-parent pairs. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(2):436–449. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heerman WJ, White RO, Hotop A, Omlung K, Armstrong S, Mathieu I, et al. A tool Kit to enhance the informed consent process for community-engaged pediatric research. IRB. 2016;38(5):8–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkin SL, Gesell SB, Po'e EK, Escarfuller J, Tempesti T. Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):445–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bibikova M, Fan JB. GoldenGate assay for DNA methylation profiling. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;507:149–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-522-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedeurwaerder S, Defrance M, Bizet M, Calonne E, Bontempi G, Fuks F. A comprehensive overview of Infinium HumanMethylation450 data processing. Brief Bioinform. 2014;15(6):929–941. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Zhou S, Smas CM. Downregulated expression of the secreted glycoprotein follistatin-like 1 (Fstl1) is a robust hallmark of preadipocyte to adipocyte conversion. Mech Dev. 2010;127(3–4):183–202. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwood TA, Lazzeroni LC, Calkins ME, Freedman R, Green MF, Gur RE, et al. Genetic assessment of additional endophenotypes from the consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia family study. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradfield JP, Taal HR, Timpson NJ, Scherag A, Lecoeur C, Warrington NM, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new childhood obesity loci. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):526–531. doi: 10.1038/ng.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL, Voruganti VS, Haack K, Gibbs RA, et al. Novel genetic loci identified for the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartelt A, Widenmaier SB, Schlein C, Johann K, Goncalves RLS, Eguchi K, et al. Brown adipose tissue thermogenic adaptation requires Nrf1-mediated proteasomal activity. Nat Med. 2018;24(3):292–303. doi: 10.1038/nm.4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Chan JY. Nrf1 is targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane by an N-terminal transmembrane domain. Inhibition of nuclear translocation and transacting function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(28):19676–19687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, Kashyap S, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atikuzzaman M, Alvarez-Rodriguez M, Vicente-Carrillo A, Johnsson M, Wright D, Rodriguez-Martinez H. Conserved gene expression in sperm reservoirs between birds and mammals in response to mating. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3488-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGovern DP, Gardet A, Torkvist L, Goyette P, Essers J, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association identifies multiple ulcerative colitis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):332–337. doi: 10.1038/ng.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu JN, Nguyen N, Aghazarian M, Tan Y, Sevrioukov EA, Mabuchi M, et al. Grim promotes programmed cell death of Drosophila microchaete glial cells. Mech Dev. 2010;127(9–12):407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattiotti A, Prakash S, Barnett P, van den Hoff MJB. Follistatin-like 1 in development and human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(13):2339–2354. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2805-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato H, Nomura K, Osabe D, Shinohara S, Mizumori O, Katashima R, et al. Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2) gene with type 2 diabetes in the Japanese. Genomics. 2006;87(4):446–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paterson AD, Waggott D, Boright AP, Hosseini SM, Shen E, Sylvestre MP, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a novel major locus for glycemic control in type 1 diabetes, as measured by both A1C and glucose. Diabetes. 2010;59(2):539–549. doi: 10.2337/db09-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chow Tze Jen, Tee Shiau Foon, Loh Siew Yim, Yong Hoi Sen, Abu Bakar Abdul Kadir, Tang Pek Yee. Variants in ZNF804A and DTNBP1 assessed for cognitive impairment in schizophrenia using a multiplex family-based approach. Psychiatry Research. 2018;270:1166–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porcelli S, Lee SJ, Han C, Patkar AA, Albani D, Jun TY, et al. Hot genes in schizophrenia: how clinical datasets could help to refine their role. J Mol Neurosci. 2018;64(2):273–286. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-1016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bai Y, Qiu S, Li Y, Li Y, Zhong W, Shi M, et al. Genetic association between SHANK2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to autism spectrum disorder. IUBMB Life. 2018;70(8):763–776. doi: 10.1002/iub.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim R, Kim J, Chung C, Ha S, Lee S, Lee E, et al. Cell-type-specific Shank2 deletion in mice leads to differential synaptic and behavioral phenotypes. J Neurosci. 2018;38(17):4076–4092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2684-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabin MA, Werther GA, Kiess W. Genetics of obesity and overgrowth syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(1):207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sim CK, Kim SY, Brunmeir R, Zhang Q, Li H, Dharmasegaran D, et al. Regulation of white and brown adipocyte differentiation by RhoGAP DLC1. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao YC, Lo SH. Deleted in liver cancer-1 (DLC-1): a tumor suppressor not just for liver. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(5):843–847. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang Y, Zheng J, Chen D, Li F, Wu W, Huang X, et al. Transcriptome profiling identifies a recurrent CRYL1-IFT88 chimeric transcript in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(25):40693–40704. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park KS, Shin HD, Park BL, Cheong HS, Cho YM, Lee HK, et al. Putative association of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1beta (PPARGC1B) polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2006;23(6):635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koelwyn GJ, Corr EM, Erbay E, Moore KJ. Regulation of macrophage immunometabolism in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(6):526–537. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shinozaki G, Potash JB. New developments in the genetics of bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(11):493. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suliman SG, Stanik J, McCulloch LJ, Wilson N, Edghill EL, Misovicova N, et al. Severe insulin resistance and intrauterine growth deficiency associated with haploinsufficiency for INSR and CHN2: new insights into synergistic pathways involved in growth and metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58(12):2954–2961. doi: 10.2337/db09-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams JN, Raffield LM, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Ng MC, Carr JJ, et al. Analysis of common and coding variants with cardiovascular disease in the diabetes heart study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:77. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-13-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vallée Marcotte Bastien, Guénard Frédéric, Cormier Hubert, Lemieux Simone, Couture Patrick, Rudkowska Iwona, Vohl Marie-Claude. Plasma Triglyceride Levels May Be Modulated by Gene Expression of IQCJ, NXPH1, PHF17 and MYB in Humans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(2):257. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayes MG, Pluzhnikov A, Miyake K, Sun Y, Ng MC, Roe CA, et al. Identification of type 2 diabetes genes in Mexican Americans through genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):3033–3044. doi: 10.2337/db07-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brietzke E, Trevizol AP, Fries GR, Subramaniapillai M, Kapczinski F, McIntyre RS, et al. The impact of body mass index in gene expression of reelin pathway mediators in individuals with schizophrenia and mood disorders: a post-mortem study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diekstra FP, Van Deerlin VM, van Swieten JC, Al-Chalabi A, Ludolph AC, Weishaupt JH, et al. C9orf72 and UNC13A are shared risk loci for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a genome-wide meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(1):120–133. doi: 10.1002/ana.24198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daoud H, Belzil V, Desjarlais A, Camu W, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. Analysis of the UNC13A gene as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(4):516–517. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granhall C, Park HB, Fakhrai-Rad H, Luthman H. High-resolution quantitative trait locus analysis reveals multiple diabetes susceptibility loci mapped to intervals<800 kb in the species-conserved Niddm1i of the GK rat. Genetics. 2006;174(3):1565–1572. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.062208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. CpG Dinucleotide Methylation.

Data Availability Statement

The genetic dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series access number GSE72556 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE72556).