Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is a worldwide public health concern, and approximately 85% of deaths occurs in developing countries. Thus study is designed to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice towards cervical cancer screening in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

We conducted a facility-based cross-sectional study. In this research, we used a multi-stage sampling procedure to select 520 participants. Information on socio-demographics, knowledge, attitude, and cervical cancer screening related questionnaires were collected using face-to-face interviews. Data were entered and cleaned in Epi-Data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. For the analysis, we used logistic regression along with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The statistical significance was determined by p <0.05.

Results

Approximately 154 (43.1%) of women had good knowledge, 235 (45.5%) had a favorable attitude, and nearly a quarter (118; 22.9%) had been screened for cervical cancer. Women 30–34 years [AOR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.11, 8.24), women with degree/diploma level of education [AOR=7.3, 95% CI 2.53–21.01), and having sourced information from a health professional [AOR=2.3, 95% CI: 1.27–4.17) were associated with good knowledge of cervical cancer screening. Being single [AOR=3.47, 95% CI: 1.03–11.75] and good knowledge of cervical cancer [AOR=4.76, 95%:2.65–8.57) were significant predictors of a positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening. Women who knew cervical cancer patients[AOR=2.47, 95% (1.37–4.44)] and high monthly income [AOR=3.8, 95% CI: 1.86–7.77] were associated with good practice related to cervical cancer screening.

Conclusion

Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards cervical cancer screening were shallow. The concerned body should aggressively disseminate information on cervical cancer screening, improve the economic status of women, and provide counseling about cervical cancer during health care delivery visits.

Keywords: knowledge, attitude, practice, cervical cancer screening, Ethiopia

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a global public health concern and a chronic non-communicable disease caused by the Human Papilloma Virus. Previous global study report estimated 527,600 cervical cancer cases and 265,700 deaths occurred. Among female cancers, cervical cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world.1,2 Usually, women with cervical cancer do not observe symptoms, especially in the early stages. Therefore, the presentation of malignancy in late-stage is vaginal bleeding, invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis.3,4 In addition to presenting a significant burden in terms of morbidity and mortality, cervical cancer also increases economic risk, which imposes very high direct costs on health systems, communities, households and lost the productivity of patients, premature death, and disability.5 The occurrence of cervical cancer-related death is rare in high-income countries.

The average risk of dying from cervical cancer before age 75 is three times higher in resource-poor countries than in more developed regions.6,7 Cervical carcinoma is still the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among women on the African continent. Mortality remains high. Globally it is 50% mainly because of late presentation, advanced stage of the disease, and absence of access to cervical cancer screening programs for most developing countries.1,8

A study in the Tikur Anbessa showed that 30.3% of all cancers diagnosed patients were identified as cervical cancer patients. A study in Ethiopia showed that annually the number of new cases was 7619 with 6081 deaths every year. In addition, 534,000 women over age 15 living with HIV in Ethiopia are among the most vulnerable to cervical cancer. However, very few women receive screening services in Ethiopia.9,10

The best predictor of high risk for cervical cancer is age, and the current incidence and mortality of cervical cancer under the age of 30 years is rare. Younger women tend to present with low-grade lesions, which frequently spontaneously regress to normal. In older women, however, the regression rate decreases, resulting in injuries. The WHO recommends “women younger than 30 years old should not be screened for cervical cancer”. Evidence related to knowledge, attitude with the practice of cervical cancer screening was limited, particularly in the study area. Therefore, to establish the cervical cancer prevention program and control strategy, this study aimed to assess the level of knowledge attitude and practice of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among females in the reproductive age group.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a facility-based cross-sectional study from January-February, 2017, in Wolaita Zone. Wolaita Zone divided into 15 districts and three town administrations. The population of Wolaita Zone, based on the 2007 population and housing census projection was 1,928,196, of whom 969,883 (50.3%)are male and 958,313 are female (49.7%), respectively (Source CSA). Females in the reproductive age group constitute 23% of the total population. According to the Wolaita Zone health office report, there was one teaching referral hospitals, two NGO general hospitals, four primary hospitals, 67 health centers, 342 health posts, and 143 private clinics providing services to the community.

Source and Study Population

All 30–49 years old women attending hospitals in Wolaita zone were the population, while a randomly selected women between 30–49 years of age were the sample.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included women aged over 30 years and attended ANC, Family Planning, Postnatal care services, and other Outpatient Departments (OPDs); whereas, we excluded women with known mental illness, in labor, and were critically ill.

The Sample Size and Sampling Procedures

We calculated the sample size by using the single population proportion formula. We also, used the Open-Epi statistical software version 3.03 with an assumption of knowledge about cervical cancer screening at 19%, taken from the study done at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia11 and confidence interval 95% (Z α/2=1.96) power of the test 80% and margin of error 5%, design effect (DE) 2.0. The calculated sample size was 472 and adding a 10% non –response rate, the final sample size was 520.

We used a multi-stage sampling technique. There are 15 districts with seven hospitals. Among the seven hospitals, four were selected using a simple random sampling method. Sample sizes allocated based on the size of population proportion to the respective hospitals. Finally, the selection of the study participants made by using a systematic sampling technique until the allocated sample size was reached.

Data Collection

We collected data using a structured questionnaire that is adopted from a similar study.12 It has four sections including, socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge about cervical cancer and screening, attitude towards cervical cancer screening, and practice of cervical cancer screening. We collected the data using eight trained nurses who deliver reproductive health services. Data collectors and supervisors received training before the actual data collection regarding the approach, objective of the study and ethical issues. We prepared the questionnaire in English and translated it to Amharic. To check the consistency with the meaning of the Amharic, an expert in language back-translated to English.

Data Management

We made checkups for completeness and consistency of the data through the supervisors. Quantitative data tools were pre-tested before the actual data collection to check the accuracy of responses, clarity of language, and appropriateness of the questionnaire. The study was pre-tested by testing 5% of the total sample size, which was 26. It was done at Christian Hospital a week before the actual data collection.

Operational Definitions

Cervical Cancer

Abnormal growth or proliferation of cells on the opening of the uterus.13

Cancer Screening

A procedure that is performed to identify the presence of abnormal cells in a particular tissue.

Knowledge

Questions were delivered to study participants in “Yes” or “No” options, and they were agreed or disagree based on their awareness. Each correct response was given a score of 1 and a wrong answer given a score of 0. Modified Bloom’s cut off points were used to categorized the knowledge as good 80–100%, satisfactory 50–79%, and poor below 50%. We computed the mean score to determine the overall knowledge of cervical cancer screening of respondents and it was further classified as poor and good for describing and comparison purposes.14

Attitude

we assessed the attitude using a Likert scale. The scoring system used was: strongly disagree =1, disagree=2, indifferent=3, agree= 4, strongly agree=5.The responses were summed and a total score was obtained. Then we calculated the mean score. Those who scored the mean score and above were considered as having a positive attitude, whereas those the women who scored below the mean score were categorized as negative in attitudes towards cervical cancer screening.

Poor Practice

Respondents who never underwent screened for cervical cancer.

Good Practice

Respondents who had been screened for cervical cancer at least once.

Data Processing and Analysis

We entered the data into Epi-Data version 3.1 and exported into SPSS version 20 for analysis using binary and multivariable logistic regression to determine the frequencies and associations between independent and outcome.

We checked all factors with a p< 0.05 in the bivariate logistic regression analysis for further confounding effect control by running multivariate logistic regressions. All the continuous data were checked for normality using a histogram and other visual tests. We also checked multicollinearities. We computed the Cronbach’s alpha for attitude towards cervical cancer screening and considered >0.7 as adequate.

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test was used to assess the fitness of the model during multivariate analysis, at p > 0.05. The crude and adjusted odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval were reported to measure the strength of the association between independent and outcome variables. The results of multivariate logistic regression were considered statistically significant at p <0.05.

Ethical Consideration

We obtained ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board of the College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University. The permission letter was obtained from Wolaita Zone Health Department and selected hospitals. We explained the aim of the study to the study participants. We received the informed written consent from each respondent. They were told that documents were kept confidential and they had the right to refuse their participation at any time without penalty. Participants who had cervical cancer during data collection were counseled for better investigation and treatment options as soon as possible.

Results

A total of 516 women participated in the study, which made the response rate to be 99.2%. The overall knowledge of cervical cancer screening, positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening, practice towards cervical cancer screening were 46.1%, 45.5%, and 22.9% respectively.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

From 516 total respondents, 188 (36.4%) were in the age range 30–34, the mean age was 36.8 (± SD 4.98), and the minimum and maximum age were 30 and 49. Most 309 (59.9%) were married. Approximately 266 (51.6%) were Protestants, followed by Orthodox, 168 (32.6%). More than one-third, 177 (34.3%) of the respondents held a diploma or degree, while 110 (21.3%) had no formal education. Most respondents 125 (24.2%) were housewives, 107 (20.7%) were private employees, and 100 (19.4%) were governmental employees. More than half (345; 66.9%) were urban residence with monthly income below 2000 Ethiopian birr 329 (63.8%) (Table 1)

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Respondents at Woliata Zone, Ethiopia, 2017

| Variable (n=516) | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30–34 | 188 | 36.4 |

| 35–39 | 164 | 31.8 | |

| 40–44 | 97 | 18.8 | |

| 45–49 | 67 | 13.0 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 168 | 32.6 |

| Protestant | 36 | 7.0 | |

| Catholic | 266 | 51.6 | |

| Muslim | 46 | 8.9 | |

| Marital status | Single | 159 | 30.8 |

| Married | 309 | 59.9 | |

| Divorced | 24 | 4.7 | |

| Widowed &separated | 24 | 4.7 | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 110 | 21.3 |

| Primary school | 103 | 20.0 | |

| Secondary school | 126 | 24.4 | |

| Diploma or degree | 177 | 34.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | 345 | 66.9 |

| Rural | 171 | 33.1 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 125 | 24.2 |

| Student | 54 | 10.5 | |

| Private employ | 107 | 20.7 | |

| Daily labor | 29 | 5.6 | |

| Merchant | 101 | 19.6 | |

| Gov,employee | 100 | 19.4 | |

| Monthly income | 50–2000 | 329 | 63.8 |

| >2000 | 187 | 36.2 |

Reproductive Characteristics

Table 2 showed that most respondents (498; 98.5%) had never had sexual intercourse, and most of them (174; 34.2%) had their first sex at the age 15–18 years and 64 (12.6%) at under 15years. The mean age for first sexual intercourse was 19.57 (± SD 3.77) years with a minimum of 12 and a maximum of 35 years. Most respondents (388; 75.9%) had had a single partner while the remaining 123 (24.1%) had had multiple sexual partners. Of all the participants, 305 (61.2%) had used modern contraceptives. Of those 104 (20.2%) used oral contraceptive. Regarding cigarette smoking, 45 (8.7%) respondents were smokers at the time of the survey. Among the respondents who used oral contraceptives, 99 (19.8%) were currently using oral contraceptives. Most respondents 252 (50.4%) had not used a condom during sex. Moreover, 241 (46.7%) knew a mother diagnosed with cervical cancer. Regarding parity 74 (14.3%) were multipara (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reproductive Characteristics of the Respondents Attending Wolaita Zone Hospitals, Southern Ethiopia, 2017

| Variable (516) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Every had sex | Yes | 498 | 96.5 |

| No | 18 | 3.5 | |

| Age of first sex | <15 years | 64 | 12.6 |

| 15–18 years | 174 | 34.2 | |

| >18 years | 271 | 53.2 | |

| History of casual sex | Yes | 123 | 24.1 |

| No | 398 | 75.9 | |

| Modern contraceptives user | Yes | 305 | 61.2 |

| No | 193 | 38.8 | |

| Oral contraceptives user | Yes | 104 | 33.9 |

| No | 203 | 66.1 | |

| History of condom use | Yes | 248 | 49.6 |

| No | 252 | 50.4 | |

| History of cigarette –smoking | Yes | 45 | 8.7 |

| No | 471 | 91.3 | |

| Knew mother with CC | Yes | 241 | 46.7 |

| No | 275 | 53.3 | |

| Currently OCP user | Yes | 99 | 19.8 |

| No | 400 | 80.2 | |

| Parity | 0 | 156 | 30.2 |

| 1–4 | 286 | 55.4 | |

| >4 | 74 | 14.3 |

Knowledge of Cervical Cancer and Its Screening

Regarding symptom-related knowledge, 297 (57.6%) had a poor knowledge with the most known symptom mentioned by respondents being vaginal bleeding (223; 66.8%), and foul-smelling vaginal discharges (213; 63.8%); 282 (54.5%) had poor knowledge of the prevention and risk factors of cervical cancer. The most known risk factors that predispose to cervical cancer mentioned by respondents were multiple sexual partners (225; 67.4%), early sexual intercourse (186; 55.7%), long term OCP use (130; 38.9%).

The known prevention methods reported by the study subjects were avoiding multiple sexual partners (228; 63.8%), avoiding early sexual intercourse (195; 58.3%), avoiding long term use of OCP (123; 36.8%), and spacing children.

Regarding treatment, most respondents (442; 85.7%) had poor knowledge. Surgery (151; 54.8%), was the most familiar treatment to those who heard of cervical cancer.

Knowledge related to cervical cancer screening were assessed, 362 (70.2%) had poor knowledge about availability, 400 (77.6%) had poor knowledge about screening interval, 382 (74%) had poor knowledge about screening eligibility, and 429 (83.1%) had poor knowledge about screening methods. Some (202; 60.5%) knew that there is screening for cervical lesions; 77 (38.1%) knew the age at which one can screen, and 62 (68.9%) aware at least of one method of screening.

To determine the overall knowledge of cervical cancer screening of response of the study subject’s scores were pooled, and the mean score computed. Respondents who scored above the mean score knowledge were considered as having good knowledge; in this case, respondents who scored above mean value numbered 154 (46.1%), the rest (180; 53.9%) had poor knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3.

Composite Knowledge Distribution of Response Among Women Who Heard Cervical Cancer and Its Screening, South Ethiopia 2017, n=516

| Knowledge of Cervical Cancer | Response n (%), n=334 | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Knowledge related to the symptom of cervical cancer (CC): Poor 297 (57.6%), Good 219 (42.4%) | ||

| Vaginal bleeding | 223 (68.8%) | 111 (33.2%) |

| Vaginal foul smelling discharges | 213 (63.8%) | 121 (36.2%) |

| Pain during sex | 153 (45.8% | 181 (54.2%) |

| Knowledge related to risk factor of CC: Poor 281 (54.5%), Good 235 (45.5%) | ||

| Acquiring HPV | 66 (19.8%) | 268 (80.2%) |

| Multiple sex partner | 225 (67.4%) | 109 (32.6%) |

| Multi parity | 163 (48.2%) | 171 (51.2%) |

| Early sexual intercourse | 186 (55.7%) | 148 (44.3%) |

| Long term OCP use | 130 (38.9%) | 204 (61.1%) |

| Cigarette smoking | 149 (44.6%) | 185 (55.4%) |

| Do not know risk factor | 60 (18%) | 274 (82%) |

| Knowledge related to prevention of CC: Poor 282 (54.5%), Good 234 (45.3%) | ||

| Vaccination for HPV | 52 (15.6%) | 281 (84.4%) |

| Avoid multiple sex partner | 228 (68.3%) | 106 (31.7%) |

| Avoid early sexual intercourse | 195 (58.3) | 139 (41.6%) |

| Spacing children | 159 (47.6%) | 175 (52.4%) |

| Avoid long term use of OCP | 123 (36.8%) | 211 (63.2%) |

| Early screening | 144 (43.2%) | 189 (56.8%) |

| No smoking | 150 (44.9%) | 184 (55.1%) |

| Do not know prevention | 49 (14.7%) | 285 (85.3%) |

| Knowledge related to the treatment of CC: Poor 442 (85.7%), Good 74 (14.3%) | ||

| Surgery | 151 (54.8%) | 183 (45.2%) |

| Chemotherapy | 58 (17.4%) | 276 (82.6%) |

| Radiotherapy | 128 (38.3%) | 206 (61.7%) |

| Do not know | 77 (23.1%) | 257 (76.9%) |

| Knowledge of cervical cancer screening | Response (n=202) | |

| Availability of screening service | Yes | No |

| Is the there screening for CC | 202 (60.5%) | 132 (39.5%) |

| Knowledge related to screening interval: Poor 400 (77.6%), Good 116 (22.4%) | ||

| Every year | 56 (27.7%) | 146 (72.3%) |

| Every three year | 39 (19.3%) | 163 (80.7%) |

| Every five year | 77 (38.1%) | 125 (61.9%) |

| Do not know | 30 (14.9%) | 172 (85.1%) |

| Knowledge related to screening eligibility: Poor 382 (74%), Good 134 (26%) | ||

| Women 30 years age and above | 134 (66.3%) | 68 (33.7%) |

| Prostitute (15–29) | 43 (21.3%) | 159 (78.3%) |

| Elderly women | 12 (5.9%) | 190 (94.1%) |

| Do not know | 13 (6.4%) | 189 (93.6%) |

| Knowledge related to CC screening procedure: Poor 429 (83.1%), Good 87 (16.9%) | ||

| VIA | 68 (33.7%) | 134 (65.3%) |

| PAP | 30 (14.9%) | 172 (85.1%) |

| Do not know | 104 (51.5%) | 98 (48.5%) |

| Composite Knowledge score | ||

| Poor Knowledge | 180 (53.9%) | – |

| Good knowledge | 154 (46.1%), | – |

Abbreviation: CC, Cervical cancer.

Attitude Towards Cervical Cancer and It Screening

Eight questions assessed the attitude of respondents (Table 4), which resulted in a mean score of 19.3 (± SD 6.6), the minimum score was 8, and a maximum score was 32. Based on the mean score, the respondents who scored below the mean score of 281 (54.5%) of the respondents were classified as having negative attitudes and those with higher than the mean score numbered 235 (45.1%) indicating respondents with positive attitudes towards cervical cancer and screening. From all the respondents 174 (33.5%) agreed that cervical cancer is becoming a problem in Ethiopia and also 114 (22.1%) of them strongly agreed that anyone including themselves could have cervical cancer. However, most (197; 38.2%) agreed that cervical cancer screening was essential and 217 (42.1%) were willing to undergo cervical cancer screening (Table 4)

Table 4.

Attitude of Cervical Cancer and in Wolaita Zone, 2017

| Variable (n=516) | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Carcinoma of the cervix is highly prevalent in Ethiopia | ||

| Strongly agree | 147 | 28.5 |

| Agree | 174 | 33.7 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 76 | 14.7 |

| Disagree | 112 | 21.7 |

| Strongly disagree | 7 | 1.4 |

| Carcinoma of the cervix is the leading cause of death among all malignance in Ethiopia | ||

| Strongly agree | 129 | 25 |

| Agree | 207 | 40.1 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 76 | 14.7 |

| Disagree | 104 | 20.2 |

| Strongly disagree | 129 | 25 |

| Any adult woman including you can acquire cervical carcinoma | ||

| Strongly agree | 114 | 22.1 |

| Agree | 201 | 39 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 82 | 15.9 |

| Disagree | 118 | 22.9 |

| Strongly disagree | 1 | 0.2 |

| Carcinoma of the cervix cannot be transmitted from one person to another | ||

| Strongly agree | 58 | 11.2 |

| Agree | 161 | 31.2 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 128 | 24.8 |

| Disagree | 166 | 32.2 |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 0.6 |

| Screening helps in prevention of carcinoma of the cervix | ||

| Strongly agree | 109 | 21.1 |

| Agree | 197 | 38.2 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 109 | 21.1 |

| Disagree | 101 | 19.6 |

| Strongly disagree | 197 | 38.2 |

| Screening causes no harm to the client | ||

| Strongly agree | 107 | 20.7 |

| Agree | 206 | 39.9 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 97 | 18.8 |

| Disagree | 103 | 20 |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 0.6 |

| Cervical cancer screening is not expensive | ||

| Strongly agree | 93 | 18 |

| Agree | 170 | 32.9 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 86 | 16.7 |

| Disagree | 165 | 32 |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.4 |

| If screening is free and causes no harm will you screen | ||

| Strongly agree | 217 | 42.1 |

| Agree | 173 | 33.5 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 33 | 6.4 |

| Disagree | 91 | 17.6 |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 0.4 |

The Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening

Most (398; 77.1%) had never screened for cervical cancer. However, 441 (85.5%) had screened for any reproductive issue such as HIV, STI, and only 118 (22.9%) had only one exposure for the practice of cervical cancer screening. Most (116; 98.3%) had been screened in hospitals and 62 (52.5%) were screened at the initiation of a health professional, 51 (43.2%) were self-initiated and the rest were initiated by friends, community, and mass media (Table 5).

Table 5.

The Response Rate of Respondents Towards Cervical Cancer Screening

| Variable (516) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever screened for reproductive health services like HIV, STI | No | 75 | 14.5 |

| Yes | 441 | 85.5 | |

| Have you ever screened for cervical cancer | No | 398 | 77.1 |

| Yes | 118 | 22.9 | |

| Where did you screen | Hospital | 116 | 98.3 |

| Other | 2 | 1.7 | |

| How many times you screened | Only one | 118 | 100 |

| When was last time you screened | Last one year | 30 | 5.8 |

| Within the past three years | 17 | 3.3 | |

| More than three years ago | 23 | 4.5 | |

| In this year | 52 | 10.1 | |

| Who initiated you to be screened | Health professional | 62 | 52.5 |

| Self-initiated | 51 | 43.2 | |

| Mass media | 17 | 14.4 | |

| Others | 42 | 35.6 |

Reasons for Not to Be Screened by Cervical Cancers

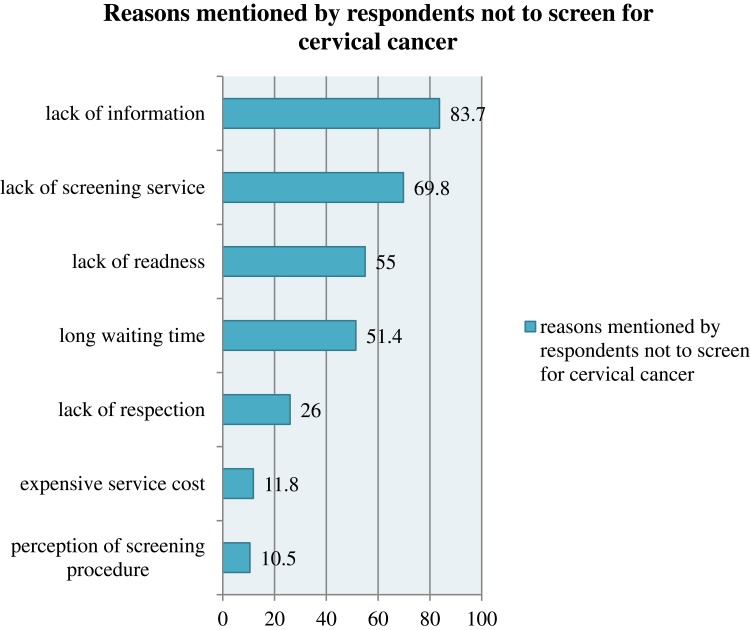

Among the reasons mentioned for non-screening, 83.7% mentioned a lack of information and lack of screening service (69.8%), lack of readiness (55%), long waiting time (51.4%), lack of respect (26%), expensive service cost (11.8%), and perception of screening procedure (10.5%) (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Reasons for not having the practice to use cervical cancer screening among study subjects in southern Ethiopia, 2017, n=516.

Note: Percent exceed 100% because of multiple responses.

Factors Associated with Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening

Among the socio-demographic factors age, educational status, and residence was significantly associated with knowledge of cervical cancer screening. Other factors, such as having knowledge with cervical cancer, knowing someone with cervical cancer and those women’s source of information from the health professional and community, age of first sex, were associated with the outcome variable.

In multivariate analysis, age, educational status, source of information from health professionals were associated with the outcome variable. The association of age with knowledge of cervical cancer screening among women attending hospital revealed that women in age group 30–34 were three times more likely to have good knowledge of cervical cancer screening than women 45–49 years of age [AOR=3.02; 95% CI:1.11–8.24].

The association of educational status with outcome variable among women showed that mothers who had a secondary level of education were about five times more knowledgeable about cervical cancer screening compared with those who did not attend formal education [AOR= 5.2;95% CI:1.73–15.65]. Women who had a degree/or diploma level education were about seven times more knowledgeable about cervical cancer screening compared with those who did not attend formal education [AOR=7.3, 95% CI:2.53–21.01].

Women who had a source of information from health professionals were two times more knowledgeable about cervical cancer screening compared with women who had not had a source of information from health professionals [AOR=2.3; 95% CI:1.27–4.17] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors Associated with Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening in Wolaita Zone, 2017 (n=516)

| Variable (516) | Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good Knowledge | Poor Knowledge | |||

| Age-group | ||||

| 30–34 | 66 (58.9%) | 46 (41.1%) | 2.97 (1.44–6.11)** | 3.02 (1.11–8.24)* |

| 35–39 | 49 (49.5%) | 50 (50.5%) | 2.03 (0.97–4.21) | 1.54 (0.57–4.19) |

| 40–44 | 24 (31.2%) | 53 (68.8%) | 0.94 (0.43–2.05) | 0.92 (0.32–2.69) |

| 45–49 | 15 (32.6%) | 31 (67.4%) | 1 | |

| Educational status | ||||

| No formal education | 9 (18.4%) | 26 (74.3%) | 1 | |

| Primary education | 6 (11.3%) | 47 (88.7%) | 0.57 (0.19–1.73) | 0.90 (0.21–3.85) |

| Secondary education | 43 (50%) | 43 (50%) | 4.44 (1.92–10.27)*** | 5.2 (1.73–15.65)** |

| Degree &above | 96 (65.8%) | 50 (34.2%) | 8.35 (3.84–18.99) *** | 7.3 (2.53–21.01) *** |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 117 (50.4%) | 115 (49.6%) | 1.79 (1.11–2.89) * | 0.73 (0.35–1.52) |

| Rural | 37 (36.3%) | 65 (63.7%) | 1 | |

| Know someone diagnose with cervical cancer | ||||

| No | 52 (34.2%) | 100 (65.8%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 102 (56%) | 80 (44%) | 2.45 (1.57–3.83) *** | 1.44 (0.77–2.70) |

| Source of information (HW) | ||||

| No | 40 (28.6%) | 100 (71.4%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 114 (58.8%) | 80 (41.2%) | 3.56 (2.24–5.67) *** | 2.3 (1.27–4.17) ** |

| Source of information (community) | ||||

| No | 129 (49.6%) | 31 (36.5%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 25 (34.2%) | 10 (66.7%) | 53 (0.31–0.91) * | 0.65 (0.31–1.39) |

| Age at first sex | ||||

| <15 | 27 (61.4%) | 17 (38.6%) | 1 | |

| 15–18 | 53 (47.7%) | 58 (52.3%) | 0.58 (0.28–1.17) | 0.85 (0.32–2.26) |

| >18 | 70 (40.5%) | 103 (59.5%) | 0.43 (0.22–0.84) * | 0.59 (0.23–1.52) |

| Currently OCP users | ||||

| No | 117 (52.2%) | 107 (47.8%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 29 (29.6%) | 69 (70.4%) | 0.38 (0.23–0.64) * | 1.45 (0.72–2.91) |

Notes: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The Associated Factors with the Attitude Towards Cervical Cancer Screening in Wolaita Zone

Analysis of our result found that knowledge of cervical cancer, marital status, and monthly income was associated with the outcome variable in multivariable regression. Women who had good knowledge of cervical cancer 4.8 times more likely to have positive attitudes towards cervical cancer screening than women who had poor knowledge of cervical cancer [AOR=4.76, 95% CI:2.65–8.57].

The association of marital status with the attitude towards cervical cancer screening indicated that women who were single were 3.47times more likely to have a positive attitudes towards cervical cancer screening than widowed[AOR=3.47, 95% CI: 1.03–11.75].

The association of income status with the attitude towards cervical cancer screening indicated that women who had a monthly income higher than 2000 Ethiopian birr were 2.46 times more likely to have a positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening compared with women who had a low monthly income [AOR=2.46, 95% CI:1.26–4.82] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Factors Associated with the Attitude Towards Cervical Cancer Screening in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2017 (n=516)

| Variable | Attitude Towards Cervical Cancer Screening | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Attitude | Negative Attitude | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 116 (73%) | 43 (27%) | 3.78 (1.56–9.14)* | 3.47 (1.03–11.75)** |

| Married | 97 (31.4%) | 212 (68.6%) | 0.64 (0.28–1.49) | 0.7 (0.23–2.19) |

| Divorced | 12 (50%) | 12 (50%) | 1.4 (0.45–4.38) | 1.28 (0.30–5.45) |

| Widowed | 10 (41.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | 1 | |

| Educational status | ||||

| Primary education | 50 (48.5%) | 53 (51.5%) | 0.73 (0.43–1.25) | 1.42 (0.55–3.67) |

| Secondary education | 59 (46.8%) | 67 (53.2%) | 0.68 (0.41–1.14) | 0.82 (0.36–1.86) |

| Diploma/or degree | 64 (36.2%) | 113 (63.8%) | 0.44 (0.27–0.71)* | 0.47 (0.21–1.05) |

| No formal education | 62 (56.4%) | 48 (43.6%) | 1 | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 22 (40.7%) | 32 (59.3%) | 1.10 (0.58–2.12) | 0.95 (0.37–2.44) |

| Private employ | 42 (39.5%) | 65 (60.7%) | 1.04 (0.61–1.76) | 0.46 (0.19–1.15) |

| Daily labor | 15 (51.5%) | 14 (48.3%) | 1.72 (0.76–3.87) | 0.65 (0.17–2.45) |

| Merchant | 38 (37.6%) | 63 (62.4%) | 0.97 (0.56–1.66) | 0.4 (0.42–1.49) |

| Government employ | 70 (70%) | 30 (30%) | 3.74 (2.14–6.55)* | 1.07 (0.44–2.62) |

| House wife | 48 (38.4%) | 77 (61.6%) | 1 | |

| Income | ||||

| >2000 | 100 (53.5%) | 87 (46.5%) | 1.65 (1.15–2.37)* | 2.2 (1.16–4.19)* * |

| 50–2000 | 135 (41%) | 194 (59%) | 1 | |

| Knowledge of CC | ||||

| Poor | 81 (45.5%) | 97 (54.5%) | 1 | |

| Good | 117 (75%) | 39 (25%) | 3.59 (2.25–5.73)* | 4.76 (2.65–8.57)** |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 90 (52.6%) | 81 (47.4%) | 1 | |

| Urban | 145 (42% | 200 (58%) | 0.44 (0.27–0.71)* | 0.97 (0.54–1.73) |

Notes: *Statistically significant in COR, **statistically significant in AOR.

Factors Associated with Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening

The association of age with the practice of cervical cancer screening among women who were attending hospital revealed that women age group 30–34 were seven times more likely to have good practice in cervical cancer screening compared with women 45–49years of age [AOR=7,95% CI:2.35–21.02]. Women in age group 35–39 were 6.7 times more likely to have a good practice of cervical cancer screening compared with women 45–49 years of age [AOR=6.7,95% CI:2.25–20.10].

The association of education with practice of cervical cancer screening among women attending hospital showed that women who had degree/diploma level of education were 5.2 times more likely to have a good practice regarding cervical cancer screening compared with those did not attend formal education [AOR=5.2,95% CI:1.57–17.49].

Women who had known someone diagnosed with cervical cancer were 2.47 times more likely to have a good practice of cervical cancer screening when compared with mothers who did not know who diagnosed with cervical cancer [AOR=2.47,95% CI:1.37–4.44].

The association of monthly income with outcome variable among women attending hospital revealed that women who had monthly income more than 2000 birr were 3.8 times more likely to have a good practice regarding cervical cancer screening compared with mothers with low income [AOR=3.8,95% CI: 1.86–7.77] (Table 8).

Table 8.

Factors Associated with Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening in Wolaita Zone, 2017

| Variable | Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | |||

| Age | ||||

| 30–34 | 53 (28%) | 135 (71.8%) | 4.9 (1.86–12.78)*** | 7.03 (2.35–21.02)*** |

| 35–39 | 48 (29.3%) | 116 (70.7%) | 5.1 (1.94–13.55)*** | 6.7 (2.25–20.10)** |

| 40–44 | 12 (12.4%) | 85 (87.6%) | 1.8 (0.59–5.23) | 2.05 (0.61–6.89) |

| 45–49 | 5 (7.5%) | 62 (92.5%) | 1 | |

| Education | ||||

| No formal education | 5 (4.5%) | 105 (95.5%) | 1 | |

| Primary education | 48 (29.3%) | 92 (89.3%) | 2.5 (0.84–7.49) | 1.69 (0.42–6.71) |

| Secondary education | 12 (12.4%) | 101 (80.2%) | 5.2 (1.92,14.11)** | 2.5 (0.71–8.56) |

| Degree/diploma | 77 (43.5%) | 100 (56.5%) | 16.2 (6.28–41.61)*** | 5.2 (1.57–17.49)** |

| Occupation | ||||

| Housewife | 14 (11.2%) | 111 (88.8%) | 1 | |

| Student | 17 (31.5%) | 37 (63.5%) | 3.6 (1.64–8.10)** | 1.5 (0.51–4.37) |

| Private employ | 39 (36.4%) | 68 (63.6%) | 4.6 (2.30–8.99)** | 0.6 (0.21–1.72) |

| Daily labor | 6 (20.7%) | 23 (79.3%) | 2.1 (0.72–5.95) | 3.99 (0.87–18.25) |

| Merchant | 20 (19.8%) | 81 (80.2%) | 2 (0.93–4.11) | 0.8 (0.26–2.21) |

| Government employ | 22 (22%) | 78 (78%) | 2.2 (1.08–4.64) | 0.93 (0.18–1.56) |

| Monthly income | ||||

| 50–2000 | 50 (15.2%) | 119 (63.6%) | ||

| >2000 | 68 (36.4%) | 279 (84.8%) | 3 (2.09–4.87)*** | 3.8 (1.86–7.77)*** |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 92 (26.7%) | 253 (73.3%) | 2.03 (1.25,3.28)** | 0.72 (0.36–1.44) |

| Rural | 26 (15.2%) | 145 (84.8%) | ||

| Lack of screening service | ||||

| No | 55 (35.3%) | 101 (64.7%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 63 (17.5%) | 297 (82.5%) | 0.039 (0.25–0.59)*** | 0.31 (0.17–0.56)*** |

| Know someone diagnosed with CC | ||||

| No | 39 (14.2%) | 236 (85.8%) | 1 | |

| Yes | 79 (32.8%) | 162 (67.2%) | 3 (1.92–4.55)*** | 2.47 (1.37–4.44)** |

| Knowledge of cervical cancer | ||||

| Poor knowledge | 43 (23.9%) | 137 (76.1%) | 1 | |

| Good knowledge | 62 (40.3%) | 92 (59.7%) | 2.2 (1.34–3.44)** | 0.78 (0.40–1.50) |

Notes: **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Discussion

Our study confirmed that the practice of cervical screening in Wolaita Zone is low. The overall knowledge of cervical cancer screening, positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening, practice towards cervical cancer screening were 46.1%, 45.5%, 22.9%, respectively. Age, educational status, knowing someone diagnosed with cervical cancer, sources of information from health professionals were predictors of knowledge of cervical cancer screening. Marital status, monthly income, and good knowledge were significant predictors of attitude towards cervical cancer screening. Age, education, income, and knowing someone diagnosed with cervical cancer was found to be significantly associated with the practice of cervical cancer screening.

The level of knowledge of cervical cancer screening of women attending the hospital of Wolaita zone of this study was 46.1%. This ding was comparable with the research done in Dessie referral hospital and Dessie health Center, northeast Ethiopia, which was 44 0.2% (38). It was congruent with the survey done in Kathmandu Nepal which was15 but slightly higher than a similar study in Northwest Ethiopia, Gabon, Tanzania.16–18 This could be due to the variation in study setting.

Of respondents 45.5% had good knowledge about risk factors for cervical cancer, which was less than the 73.5% finding in a Saudi Arabia study which was conducted among reproductive-age women (35). This difference may be due to cultural and socio-economic differences between these populations.

Women in age group 30–34 were three times more likely to have good knowledge of cervical cancer screening compared with women 45–49 years of age [AOR=3.02 95% CI (1.11, 8.24 which is in line with a Hospital-based cross-sectional study done in Indian.14 Women who had a degree/or diploma level of education were 7.3 times more knowledgeable about cervical cancer screening compared with that mother did not attend formal education [AOR= 95% CI (2.53, 21.01). Our findings confirmed a previous study was done in Dessie referral hospital and Dessie health center in northeast Ethiopia.19

Participants who mentioned health professionals as their source of information were statistically significant predicted to have good knowledge of cervical cancer screening. This finding is consistent with other studies in Malaysia and Gabonese17,20 and might be explained because information gained from health professionals could be comprehensive and more detailed than other sources of information.

Nearly half 45.5% of the respondents had a positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening. This finding is comparable with a study in Northeast Ethiopia, which showed 42.1% (18), but this finding is lower than the research done in Cameroon and Zimbabwean.21,22 This could be explained by the socio-economic difference between countries. We found that good knowledge of cervical cancer was a predictor of positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening. Previous studies conducted in Northwest Ethiopia, Burkinafaso, and India also confirmed this14,23,24 and could be explained by information being provided on the importance of cervical cancer screening leading to an increase in the healthcare-seeking behavior of respondents. Monthly income >2000 birr was a significant predictor of positive attitude towards cervical cancer screening and this is in line with a hospital-based study in India.14 Of respondents 22.9% had a good practice related to screening for cervical cancer. The result is higher than a study three teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2008. This discrepancy might be due to the study period11 but it was comparable with a study in Tanzania, Burkinafaso, and Kenya.18,24,25 On the other hand, it was lower than research conducted in Cameroon, Botswana, showing 55.7%, and 39%, respectively.15,18 This difference might be due health care provision strategies and health promotion being different bewteen countries.

We found that women in age group 30–34 were significantly associated with good practice towards cervical cancer screening. The finding is in line with research in India14 and explained by women aged 30–34 years being more likely to visit health care facilities. Women’s education is one of the predictors of the practice for cervical cancer screening. Our result matches research in a hospital-based study done in India.14

Women who knew someone diagnosed with cervical cancer had a statistically significant association with screening practice which agrees with a Gondar study.16 Moreover, this study found that lack of screening service at the health facility level was negatively associated with screening practice. The finding matches the research in Addis Ababa and Kenya.11,18 Common reasons mentioned by respondents for not to be screened for cervical cancer was lack of information (83.7%), lack of screening service (69.8%), lack of readiness at health facility (55%), long waiting time (51.4%), and expensive service cost (10.8%). Studies in Addis Ababa, Tanzania, and Kenya confirm our result (11, 20, 26).

Limitation of the Study

This is the cross-sectional study; hence it is not possible to differentiate cause and effect between variables. Also, its generalizability to the general population is limited because it is an institution based study.

Conclusion

This study revealed that knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer screening were moderate while practice was low. Respondents’ knowledge of cervical cancer regarding gynecologic symptoms, risk factors, prevention methods, treatment options, frequency of screening, screening methods, screening eligibility, and screening procedures were low. Age, educational status, and source of information from health professionals were statistically significant predictors of good knowledge. Positive attitude was predicted by monthly income, knowledge of cervical cancer and marital status. Similarly, knowing someone with cervical cancer, income status, and lack of screening service were significant predictors of screening practice. Therefore, health education and awareness creation regarding cervical cancer should be implemented at primary health care units. Finally, further study is recommended at the community level, including a qualitative component.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Wolaita Zone Health Department, data collectors and supervisors for their unreserved effort throughout the study.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical clearance was obtained from the College of Health Science and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. Informed written consent was obtained from the individual participants.

Data Sharing Statement

Data are available to provide for all interested persons on request from the principal author.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and also agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Wolaita Zone Health Department funded this research.

Disclosure

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Board SAHA. Cervical cancer and human papillomavirus: South African guidelines for screening and testing. South Afr j Gynecol Oncol. 2010;23:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azam S. Awareness and perspectives on cervical cancer and practices related to it: how far it has promoted? Recent Adv Cervical Cancer. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eleje G, Eke A, Igberase G, Igwegbe A, Eleje L. Palliative interventions for controlling vaginal bleeding in cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(2). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang F, Wang J, Chen Y, Ma C. Expression of microRNA (miR)-145 and miR-34a in different cervical lesion tissues of Uygur and Han females in Xinjiang, China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9(10):10382–10389. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Souza JA, Hunt B, Asirwa FC, Adebamowo C, Lopes G. Global health equity: cancer care outcome disparities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(1):6–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int j Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morhason-Bello IO, Odedina F, Rebbeck TR, et al. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: a perspective from the African Organisation for Research and Training in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):e142–e51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pathfinder international Ethiopia: combatingcervical cancer in Ethiopia. April, 2010. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/99b6/cc78b2d1429352631ea388b6e627e458d67e.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- 10.WHO/ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers in Americas. Summary Report 2010. Available from: www. who. int/hpvcentre. Accessed 20 January, 2020.

- 11.Yifru T, Asheber G. Knowledge, attitude and practice of screening for carcinoma of the cervix among reproductive health clients at three teaching hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Reprod Health. 2008;2:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aweke YH, Ayanto SY, Ersado TL, Robboy SJ. Knowledge, attitude and practice for cervical cancer prevention and control among women of childbearing age in Hossana Town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: community-based crosssectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welfare AIoHa. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016. Cervical Screening in Australia 2013–2014. Cancer Series No. 97. Cat. No. CAN 95. Canberra: AIHW; 2016:97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansal AB, Pakhare AP, Kapoor N, Mehrotra R, Kokane AM. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to cervical cancer among adult women: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6(2):324. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.159993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrestha J, Saha R, Tripathi N. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding cervical cancer screening amongst women visiting tertiary centre in Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2013;2:85–90. doi: 10.3126/njms.v2i2.8941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun F, Mazengia F, Abuhay M, Birhanu Z. Comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer is low among women in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assoumou SZ, Mabika BM, Mbiguino AN, Mouallif M, Khattabi A, Ennaji MM. Awareness and knowledge regarding of cervical cancer, Pap smear screening and human papillomavirus infection in Gabonese women. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0193-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyimo FS, Beran TN. Demographic, knowledge, attitudinal, and accessibility factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in a rural district of Tanzania: three public policy implications. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andargie A, Reddy PS. Knowledge, attitude, practice and associated factors of cervical cancer screening among women in Dessie Referral Hospital and Dessie Health Center, Northeast Ethiopia. Glob J Res Anal. 2016;4(12). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Naggar RA, Low W, Isa ZM. Knowledge and barriers towards cervical cancer screening among young women in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(4):867–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekane GEH, Obinchemti TE, Nguefack CT, et al. Pap smear screening, the way forward for prevention of cervical cancer? A community based study in the Buea Health District, Cameroon. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;5(4):226. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2015.54033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mupepi SC, Sampselle CM, Johnson TR. Knowledge, attitudes, and demographic factors influencing cervical cancer screening behavior of Zimbabwean women. J Women’s Health Care. 2011;20(6):943–952. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DBaW Y. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards cervical cancer screening among Arsi University female students. J Women’s Health Care. 2016;5(6):6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawadogo B, Gitta SN, Rutebemberwa E, Sawadogo M, Meda N. Knowledge and beliefs on cervical cancer and practices on cervical cancer screening among women aged 20 to 50 years in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2012: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.175.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kei RM, M’Ndegwa JK, Ndwiga T, Masika F. Challenges of cervical cancer screening among women of reproductive age in Kisii Town, Kisii County, Kenya. Sci J Public Health. 2016;4:296. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varadheswari T, Dandekar RH, Sharanya T. A study on the prevalence and KAP regarding cervical cancer among women attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Perambalur. Int J Pre Med Res. 2015;1(3):71–78. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Pathfinder international Ethiopia: combatingcervical cancer in Ethiopia. April, 2010. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/99b6/cc78b2d1429352631ea388b6e627e458d67e.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2020.