Abstract

Background

Gastroesophageal varices are the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in patients with cirrhosis. Vitamin K1 is commonly administered to patients presenting with UGIB and elevated international normalized ratio, despite limited evidence to support this practice.

Objectives

The primary objective was to describe the incidence of rebleeding within 30 days after vitamin K1 administration in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB. The secondary objective was to describe prescribing patterns for vitamin K1.

Methods

This retrospective, descriptive multicentre study involved patients with cirrhosis and UGIB who were admitted to any of the 4 adult acute care hospitals in Calgary, Alberta, from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016. Patients were divided into 2 groups: those who received vitamin K1 and those who did not.

Results

A total of 370 patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 243 received vitamin K1 and 127 did not. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups. Greater proportions of patients in the vitamin K1 group received transfusions of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin concentrate during their admissions. There was no significant difference in the duration of octreotide and pantoprazole infusions. Among patients in the vitamin K1 group, there were more admissions to the intensive care unit and longer lengths of stay. More patients in the no vitamin K1 group had esophageal varices evident on endoscopy that required endoscopic treatment. Forty of the patients (16.5%) in the vitamin K1 group and 7 (5.5%) in the no vitamin K1 group had rebleeding within 30 days of the initial bleed. The median total vitamin K1 dose administered was 25 mg.

Conclusions

The study results suggest that vitamin K1 does not reduce the incidence of rebleeding within 30 days of the initial bleed in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB.

Keywords: vitamin K1, phytonadione, liver cirrhosis, esophageal and gastric varices, gastrointestinal hemorrhage

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte

Les varices oesophagiennes sont la cause la plus fréquente de l’hémorragie gastro-intestinale supérieure (HGIS) parmi les patients atteints de cirrhose. On administre communément de la vitamine K1 aux patients présentant une HGIS et dont la mesure du rapport international normalisé (RIN) est élevée, malgré le manque de preuves soutenant cette pratique.

Objectifs

L’objectif principal consistait à décrire la fréquence de la reprise du saignement dans les 30 jours après l’administration de la vitamine K1 à des patients atteints de cirrhose et de HGIS. L’objectif secondaire consistait à décrire les schémas de prescription de la vitamine K1.

Méthode

Cette étude multicentrique, descriptive et rétrospective comprenait des patients atteints de cirrhose et de HGIS, ayant été admis à n’importe lesquels des quatre hôpitaux de soins actifs pour adultes de Calgary, Alberta, du 1er janvier 2014 au 31 décembre 2016. Les patients étaient répartis en deux groupes : ceux ayant reçu de la vitamine K1 et ceux n’en ayant pas reçu.

Résultats

Le nombre total de 370 patients correspondait aux critères d’inclusion. Parmi ceux-ci, 243 avaient reçu de la vitamine K1 et 127 n’en n’avaient pas reçu. Les caractéristiques de base étaient similaires entre les groupes. Un plus grand nombre de patients du groupe « Vitamine K1 “avaient reçu une transfusion d’un concentré de globules rouges, de plasma frais congelé, de plaquettes, de cryoprécipité ou de concentré de prothrombine au cours de leur séjour hospitalier. On n’a noté aucune différence significative dans la durée des injections de pantoprazole et d’octréotide. Le nombre d’admissions de patients du groupe « Vitamine K1 » à l’unité de soins intensifs était plus élevé et le séjour de ceux-ci était plus long. L’endoscopie a montré qu’un plus grand nombre de patients du groupe « Sans vitamine K1 » présentaient des varices oesophagiennes nécessitant un traitement endoscopique. Dans les 30 jours après le saignement initial, quarante (16,5 %) patients du groupe « Vitamine K1 » et 7 (5,5 %) du groupe « Sans vitamine K1 » ont subi une nouvelle hémorragie. La dose moyenne totale de vitamine K1 administrée était de 25 mg.

Conclusions

Les résultats de l’étude tendent à démontrer que la vitamine K1 ne réduit pas la fréquence de la reprise du saignement dans les 30 jours qui suivent le saignement initial parmi les patients atteints de cirrhose et de HGIS.

Mots-clés: vitamine K1, phytonadione, cirrhose du foie, varices oesophagiennes et gastriques, hémorragie gastro-intestinale

INTRODUCTION

One in 10 Canadians has some form of liver disease.1 The most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in patients with cirrhosis is gastroesophageal varices, which are present in nearly 50% of these patients.2 Variceal hemorrhage occurs at a rate of 10% to 15% per year and depends on the severity of liver disease, the size of varices, and the presence of red wale marks.2 Patients who recover from a first episode of variceal hemorrhage have a 60% risk of rebleeding in the first year.2 The mortality rate at 6 weeks after an episode of variceal hemorrhage is 15% to 25%.2 In addition, coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis is complex and is affected by numerous factors, including coagulopathic imbalances, infection, endogenous heparinoids, renal failure, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).3,4 As a result, these patients often present with elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and prolonged prothrombin time.4

Administration of vitamin K1 to patients with cirrhosis who present with UGIB is commonly used in clinical practice to improve hemostasis and to reverse potential vitamin K deficiency and INR elevation. Vitamin K1 acts a cofactor in γ-carboxylation of multiple glutamate residues, allowing for the formation of coagulation factors and binding to γ-carboxylated proteins such as prothrombin; factors VII, IX, and X; and proteins C and S.4 However, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and the American College of Gastroenterology do not mention vitamin K1 in their guidelines for the treatment of UGIB in patients with cirrhosis.2–5 In addition, the dose, frequency, and duration of vitamin K1 administration varies in clinical practice. No randomized controlled trials have examined the benefits or harms of vitamin K1 in patients with liver disease and UGIB.6 The primary objective of the current study was to describe the incidence of rebleeding at 30 days in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB who did and did not receive vitamin K1. The secondary objective was to describe the prescribing patterns for vitamin K1 administered to patients with cirrhosis and UGIB.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective, descriptive, multicentre study. Patients with cirrhosis and UGIB admitted to any of the 4 adult acute care hospitals in Calgary, Alberta, from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016, were eligible for the study.

Data Sources

A computerized search was conducted using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes within the Data Integration Measurement and Reporting (DIMR) hospital discharge abstract administrative database. Patients were identified by cross-referencing the DIMR list with Sunrise Clinical Manager, the electronic medical record used within the Calgary Zone, which was then used to gather information on demographic characteristics, laboratory values, blood products and medications administered, and discharge information. The provincial Pharmacy Information Network was used to retrieve medication information. Endoscopy reports were obtained from EndoPro (Pentax Medical Company), a database used by the Department of Gastroenterology, Calgary Zone, Alberta Health Services.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients who were 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of cirrhosis and UGIB, as defined by the ICD-10 codes, were included. Patients whose duration of admission was less than 3 days and those with no electronic discharge summary or endoscopy report were excluded. For patients with multiple admissions during the study period, only the first admission was included in the analysis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of rebleeding within 30 days after the initial bleed, in relation to whether or not vitamin K1 was administered. This outcome was based on rebleeding that occurred during the index admission, as well as postdischarge UGIB leading to readmission to any of the 4 adult acute care sites within 30 days. Rebleeding rates were compared between patients who and did not receive vitamin K1. Resolution of the initial bleed was defined as occurring on the date of endoscopy. Rebleeding was defined as a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of more than 20 g/L after endoscopy or bleeding leading to transfusion of 2 or more units of packed red blood cells.7 The secondary outcome was a description of vitamin K1 prescribing patterns, including dose, route, frequency, and total number of doses administered.

Patient Characteristics and Data Collection

Demographic data were collected for each patient, including age, sex, weight, and cirrhotic complications and characteristics (previous variceal and nonvariceal UGIB, portal hypertensive gastropathy, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatic encephalopathy). Baseline laboratory values collected included hemoglobin, platelet count, serum creatinine, and INR. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score8 and the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score9 were calculated. Additional risk factors for bleeding were collected from the discharge summary and Pharmacy Information Network data. Prescriptions for anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, nonselective β-blockers, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) within 180 days before and 30 days after the hospital admission were determined from the Pharmacy Information Network.

Data on admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU), total length of stay, death during the study period, and standard endoscopic treatment and findings were also collected. Endoscopic findings associated with increased risk of rebleeding include high-risk stigmata of peptic ulcer disease, defined as active spurting vessel, nonbleeding visible vessel, or adherent clot.5 The presence and severity of esophageal varices—where severity was based on the size of the varices and the presence or absence of red colours, as accepted by the US, European, and Asian-Pacific associations for the study of liver disease—were collected.10 Data on adverse events attributed to vitamin K1 administration were also collected.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Continuous variables that were normally distributed were described using means and standard deviations, whereas continuous variables that were not normally distributed were described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were described using frequency counts and proportions. Test of proportions were used to compare proportions between the study groups, and χ2 tests were used to study correlations between pairs of categorical variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare medians between 2 groups. Binary logistic regression was used to determine the factors associated with whether or not a patient received vitamin K1 and to determine the factors associated with rebleeding for the vitamin K1 subgroup only. Univariate logistic regression was used to determine whether any of these factors were significant. For the final multivariate model, the most parsimonious model was chosen, on the basis of clinical and statistical significance. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used to perform all statistical testing, and 2-sided tests were used for all of the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

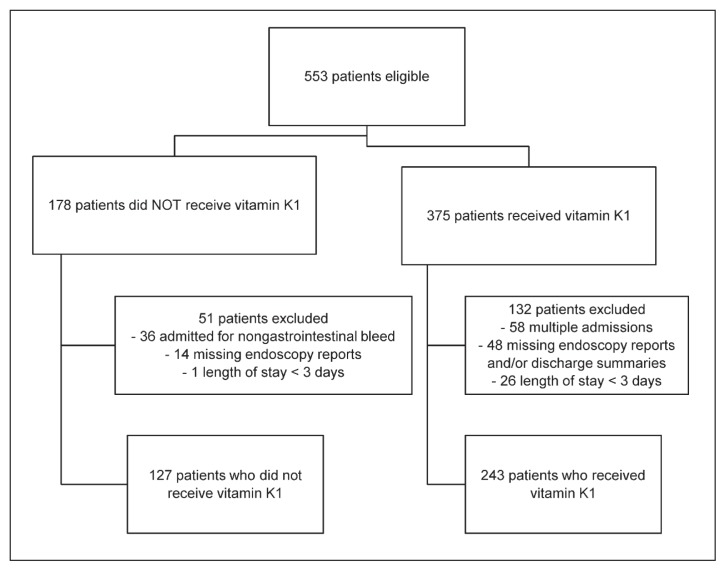

A total of 553 patients were eligible for the study (Figure 1), of whom 370 met the inclusion criteria. Of these patients, 243 had received vitamin K1, and 127 had not received vitamin K1. Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups; however, a greater proportion of patients in the no vitamin K1 group had prior portal vein thrombosis, and a greater proportion of this group had a prescription for PPI before admission (Table 1). The proportion of patients with a prescription for nonselective β-blocker before admission was similar between the 2 groups. Hemoglobin level, INR, and MELD score, were similar on presentation to the hospital.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient enrolment and exclusions.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| Characteristic | Study Group; No. (%) of Patients* | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Vitamin K1 (n = 243) | No Vitamin K1 (n = 127) | ||

| Sex, male | 169 (69.5) | 78 (61.4) | 0.12 |

|

| |||

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 56.8 ± 11.7 | 60 ± 8 | 0.002 |

|

| |||

| Weight (kg) (mean ± SD)† | 84 ± 23 | 79.5 ± 4.6 | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Complications of cirrhosis | |||

| Ascites | 94 (38.7) | 58 (45.7) | 0.20 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 47 (19.3) | 25 (19.7) | 0.95 |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | 116 (47.7) | 67 (52.8) | 0.36 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 11 (4.5) | 17 (13.4) | 0.002 |

| Previous variceal bleed | 31 (12.8) | 24 (18.9) | 0.12 |

| Previous nonvariceal bleed | 13 (5.3) | 11 (8.7) | 0.22 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 10 (4.1) | 4 (3.1) | 0.64 |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | 3 (1.2) | 4 (3.1) | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Blood components | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) (mean ± SD) | 97 ± 28.1 | 94 ± 25.1 | 0.28 |

| Hemoglobin < 70 g/L | 53 (21.8) | 23 (18.1) | 0.40 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) (median and IQR) | 106 (73–161) | 126 (87–174) | 0.019 |

| Platelets < 50 × 109/L | 22 (9.1) | 10 (7.9) | 0.70 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) (median and IQR) | 81 (59–130) | 73 (55–109) | 0.019 |

|

| |||

| INR (mean ± SD) | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.99 |

|

| |||

| MELD score (mean ± SD) | 19.4 ± 7.8 | 13 ± 5 | 0.98 |

|

| |||

| Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (mean ± SD)‡ | 9.5 ± 4 | 11.2 ± 4.1 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Home medications | |||

| Warfarin | 9 (3.7) | 1 (0.8) | 0.10 |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 4 (1.6) | 6 (4.7) | 0.08 |

| Fondaparinux | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0.17 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 3 (1.2) | 0 0.21 | |

| Clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor | 1 (0.4) | 3 (2.4) | 0.08 |

| NSAID | 45 (18.5) | 25 (19.7) | 0.79 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 87 (35.8) | 64 (50.4) | 0.007 |

| Nonselective ß-blocker | 64 (26.3) | 39 (30.7) | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| ICU admission | 65 (26.7) | 14 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Length of stay (days) (median and IQR) | 10 (5–19) | 5 (4–9) | < 0.001 |

ICU = intensive care unit, INR = international normalized ratio, IQR = interquartile range, MELD = model for end-stage liver disease (calculated from serum creatinine, INR, and total bilirubin), NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Weight was not documented for 26 patients in the group that received vitamin K1 and 16 patients in the group that did not receive vitamin K1.

Derived from urea, hemoglobin, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, sex, presence of melena, history of recent endoscopy, recent syncope, and presence of heart failure and/or liver disease.

Greater proportions of patients who had received vitamin K1 received transfusions of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and prothrombin concentrate and received tranexamic acid during the admission (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of the dose, frequency, or duration of IV octreotide and pantoprazole or the duration of antibiotic therapy for management of acute UGIB (data not shown). More patients in the vitamin K1 group had high-risk stigmata evident on endoscopy that required endoscopic treatment. A greater proportion of patients in the no vitamin K1 group had esophageal varices evident on endoscopy that required endoscopic treatment (Table 2). Two patients who had received vitamin K1 and 4 patients who had not received vitamin K1 were positive for Helicobacter pylori on biopsy. In addition, 13 patients who had received vitamin K1 and 5 patients who had not received vitamin K1 received empiric therapy for eradication of H. pylori (p = 0.55).

Table 2.

Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) and Endoscopy Results

| Variable | Study Group; No. (%) of Patients | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Vitamin K1 (n = 243) | No Vitamin K1 (n = 127) | ||

| Management of UGIB | |||

| Received packed red blood cells | 164 (67.5) | 71 (55.9) | 0.028 |

| Received fresh frozen plasma | 133 (54.7) | 14 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

| Received platelets | 59 (24.3) | 8 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Received cryoprecipitate | 16 (6.6) | 2 (1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Received 4-factor prothrombin concentrate | 10 (4.1) | 0 0.02 | |

| Received factor VII | 1 (0.4) | 0 0.47 | |

| Received tranexamic acid | 21 (8.6) | 3 (2.4) | 0.020 |

|

| |||

| Endoscopy findings | |||

| Active spurting vessel | 11 (4.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0.14 |

| Nonbleeding visible vessel | 7 (2.9) | 5 (3.9) | 0.59 |

| Adherent clot | 14 (5.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0.06 |

| Patients with high-risk stigmata requiring endoscopic treatment* | 14 (5.8) | 5 (3.9) | 0.45 |

| Esophageal varices | 145 (59.7) | 101 (79.5) | < 0.001 |

| Gastric varices | 14 (5.8) | 5 (3.9) | 0.45 |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | 28 (11.5) | 17 (13.4) | 0.60 |

| Gastroesophageal varices requiring treatment | 75 (30.9) | 58 (45.7) | 0.005 |

| Other causes of bleeding† | 31 (12.8) | 24 (18.9) | 0.12 |

IQR = interquartile range.

Active spurting vessel, nonbleeding visible vessel, and/or adherent clot.

Other causes of bleeding included (but were not limited to) esophagitis, erosive gastroduodenopathy, gastric antral vascular ectasia, malignancy, Mallory-Weiss tear, angiodysplasia, Dieulafoy lesion, telangectasia.

There was an approximate 2-fold increase in frequency of ICU admission (26.7% versus 11%, p < 0.001) and length of stay (10 days versus 5 days, p < 0.001) for patients in the vitamin K1 group. Significantly more patients in the no vitamin K1 group than in the vitamin K1 group were given a prescription for nonselective β-blocker upon discharge (84 [66.1%] of 127 versus 114 [46.9%] of 243; p < 0.001). More patients in the vitamin K1 group than in the no vitamin K1 group were given a prescription for twice-daily oral PPI upon hospital discharge (68.7% versus 58.3%; p = 0.045). There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients for whom once-daily oral PPI was prescribed (38 [15.6%] of 243 who receive vitamin K1 versus 30 [23.6%] of 127 who did not received vitamin K1; p = 0.06).

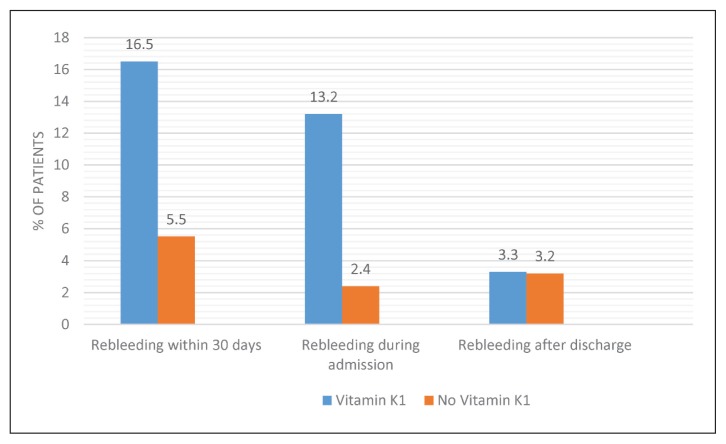

A significantly greater proportion of patients in the vitamin K1 group had rebleeding within 30 days after the initial bleed (p= 0.003) (Figure 2). In particular, the rate of rebleeding during the index hospital admission was 13.2% (32/243) in the vitamin K1 group and 2.4% (3/127) in the no vitamin K1 group (p = 0.038). Because only a few patients in the no vitamin K1 group had rebleeding, we were unable to complete the regression analysis to determine the impact of vitamin K1 on rebleeding in cirrhotic patients presenting with UGIB. However, length of stay, ICU admission, and higher values for the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score were more likely to be associated with rebleeding within the vitamin K1 group (Table 3). In the comparative regression analysis of vitamin K1 versus no vitamin K1, INR was more likely than other factors considered in the analysis to be associated with increased risk of rebleeding (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Incidence of rebleeding within 30 days of initial bleed with and without administration of vitamin K1.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Rebleeding among Patients Who Received Vitamin K1

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| High-risk stigmata on endoscopy* | 1.416 (0.354–5.667) | 0.62 |

| INR | 1.102 (0.497–2.443) | 0.81 |

| MELD score | 1.024 (0.933–1.124) | 0.62 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score | 0.787 (0.674–0.919) | 0.003 |

| ICU admission | 4.604 (1.330–15.939) | 0.016 |

| Length of stay | 1.026 (1.007–1.046) | 0.007 |

| Esophageal varices | 0.561 (0.173–1.821) | 0.34 |

| Anticoagulation before admission | 0.691 (0.070–6.790) | 0.75 |

| Nonselective ß-blocker | 0.358 (0.106–1.207) | 0.10 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1.949 (0.461–8.237) | 0.36 |

CI = confidence interval, ICU = intensive care unit, INR = international normalized ratio, MELD = model for end-stage liver disease score.

Active spurting vessels, nonbleeding visible vessels, and/or adherent clot.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Rebleeding among Patients Who Did and Did Not Receive Vitamin K1

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Esophageal varices | 0.590 (0.153–2.275) | 0.44 |

| High-risk stigmata on endoscopy* | 4.515 (0.526–38.745) | 0.17 |

| Anticoagulation before admission | 1.333 (0.165–10.759) | 0.79 |

| Nonselective ß-blocker | 1.109 (0.288–4.278) | 0.88 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1.204 (0.255–5.688) | 0.81 |

| ICU admission | 2.956 (0.516–16.950) | 0.22 |

| Length of stay | 1.035 (0.974–1.101) | 0.27 |

| INR | 4.621 (1.587–7.655) | 0.003 |

| MELD score | 0.998 (0.872–1.144) | 0.98 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score | 0.885 (0.751–1.043) | 0.14 |

CI = confidence interval, ICU = intensive care unit, INR = international normalized ratio, MELD = model for end-stage liver disease score.

Active spurting vessels, nonbleeding visible vessels, and/or adherent clot

Overall, 123 (33.2%) of the 370 patients died during the study period. In particular, 59 (24.3%) of the 243 patients in the vitamin K1 group died during the index admission, as compared with 2 (1.6%) of the 127 patients in the no vitamin K1 group (p < 0.001). Death was most commonly attributed to end-stage liver disease.

The dose of vitamin K1 most commonly prescribed was 10 mg, for IV or oral administration (Table 5). The median cumulative vitamin K1 dose was 25 mg administered over 3 days. Eighty-nine (36.6%) of the 243 patients in the vitamin K1 group received a single dose. No adverse effects of vitamin K1 were reported.

Table 5.

Summary of Vitamin K1 Prescribing Patterns (n = 1079 Doses)

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Smallest dose prescribed (mg) | 2.5 |

| Largest dose prescribed (mg) | 20 |

| Dose (mg) (mean ± SD) | 10 ± 0 |

| No. (%) 10-mg doses prescribed | 787 (72.9) |

| Cumulative dose per patient (mg) (median and IQR) | 25 (10–40) |

| Cumulative doses received per patient (median and IQR)* | 3 (1–5)* |

| No. (%) of doses by route of administration | |

| IV | 624 (57.8) |

| Oral | 422 (39.1) |

| Intramuscular | 3 (0.3) |

| Subcutaneous | 30 (2.8) |

Eighty-nine patients received only a single dose of vitamin K1

DISCUSSION

The administration of vitamin K1 for acute management of UGIB in patients with cirrhosis is common practice, despite limited supporting evidence. Patients with chronic liver disease have altered hemostasis, because liver disease profoundly affects coagulation through abnormalities in platelet-vessel interactions, thrombin generation and inhibition, clotting factor production, and clot dissolution.11,12 Underlying conditions that increase the risk of bleeding in patients with cirrhosis include portal hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, bacterial infection, thrombo cytopenia, development of endogenous heparin-like substances, and renal failure.11,13 In the current study, there was no significant difference in portal hypertensive gastropathy, renal function, or duration of prophylactic antibiotic therapy. The patients who received vitamin K1 had more severe thrombocytopenia and received significantly more platelet transfusions. A platelet count as low as 50–60 × 109/L in patients with cirrhosis is usually sufficient to preserve thrombin generation, and counts above 100 × 109/L show little extra benefit relative to controls.11,12 In the current study, there was no significant difference between groups in the proportion of patients with platelet count less than 50 × 109/L. Patients with cirrhosis have increased levels of von Willebrand factor, which increases the adhesive capacity of platelets, resulting in increased effectiveness of the limited number of platelets.4,11,12

The patients who received vitamin K1 appeared to have greater clinical instability than those who did not receive vitamin K1, as demonstrated by the statistically significant difference in ICU admissions and the increased length of stay. This greater clinical instability is also indicated by the increased proportions of patients who received packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, or prothrombin concentrate during their admission. Patients who received vitamin K1 also received more tranexamic acid to control UGIB, which suggests that they exhibited greater coagulopathy than the patients who did not receive vitamin K1.14 We propose that vitamin K1 was administered to those with more advanced liver disease and more severe, life-threatening hemorrhage. Indeed, a greater proportion of patients in the vitamin K1 group than the no vitamin K1 group died before hospital discharge due to end-stage liver disease.

Our study showed that the greater the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score, the greater the risk of rebleeding in patients who received vitamin K1. This bleeding score is derived from urea, hemoglobin, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, sex, presence of melena, history of recent endoscopy, recent syncope, and presence of heart failure and/or liver disease. It is a formal risk assessment tool for UGIB to identify patients who require urgent medical or endoscopic therapy (i.e., score > 2),15,16 although it has not been validated to assess the risk of rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB. The score predicted urgent intervention for all of the included patients. Despite the statistically significant difference between the 2 groups, the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score did not influence rebleeding, as shown by the results of the regression analysis. This result may have been influenced by the low number of patients with rebleeding in the no vitamin K1 group.

Our study also suggested that the greater the INR, the greater the risk of rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis presenting with UGIB. Among patients in the vitamin K1, the INR was 46% higher than among those in the no vitamin K1 group, although the difference was not statistically significant. INR is a measure of vitamin K1–dependent clotting factors that was originally developed in the early 1980s for standardization of therapeutic anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists in healthy volunteers. However, it has not been validated for patients with chronic liver disease.11,12,17 In patients with cirrhosis, coagulopathy is complex, and their elevated INR may be a result of multiple factors, including decreased synthesis of clotting factors due to intrinsic hepatic impairment, rather than vitamin K1 deficiency. INR is not a predictor of rebleeding in nonvariceal UGIB.18 Nevertheless, in practice, the INR is typically measured for patients with cirrhosis who present with UGIB, and those with elevated INR values often receive parenteral vitamin K1.4 Vitamin K1 can reduce INR by 0.2 to 0.3 in some patients with cirrhosis-associated coagulopathy; however, those with more advanced liver disease (MELD score > 30) rarely experience a reduction in INR with such treatment.3,19

Nonselective β-blockers reduce portal pressure and are used in the primary and secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.20 The goal of therapy is to achieve a heart rate of 55 to 60 beats/min, while maintaining systolic blood pressure above 90 mm Hg.2 In the current study, we were unable to investigate whether patients achieved this goal. There is a clinical window within which β-blockers are associated with higher rates of survival. The clinical window opens when moderate to large esophageal varices develop, and patients may present with or without variceal bleeding.20 The clinical window closes when refractory ascites, hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 100 mm Hg or mean arterial pressure below 82 mm Hg), serum sodium below 120 mmol/L, acute kidney injury, hepatorenal syndrome, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, sepsis, or severe alcoholic hepatitis develops, leading to unfavourable hemodynamic effects in advanced cirrhosis.2,20 Relative to baseline, there were increases of 78% in the use of nonselective β-blockers in the vitamin K1 group and 115% in the no vitamin K1 group. Nonselective β-blockers reduce the risk of recurrent variceal bleeding from 63% to 42% (number needed to treat 5).21 This may have contributed to the lower number of recurrent bleeds in the no vitamin K1 group.

The doses of vitamin K1 commonly administered in clinical practice range from 0.5 to 10 mg daily, but limited evidence exists concerning the route or frequency of administration. The most common dose of vitamin K1 prescribed in the current study was 10 mg, with a median cumulative dose of 25 mg. Most patients received 3 doses. The most common route of administration was oral or parenteral. These data are similar to the dose, route of administration, and frequency of administration that have been described previously.3,4,19

Selection bias may have existed, given the differences in baseline characteristics, endoscopic results, and management of UGIB between the 2 groups. This is a limitation of the study design, given that this was a retrospective, descriptive study from which we cannot explicitly derive treatment effect.

CONCLUSION

Despite the lack of evidence to support the efficacy of vitamin K1 to reduce the risk of rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB, vitamin K1 administration is common. This descriptive study suggests that vitamin K1 does not reduce the incidence of rebleeding within 30 days after an initial bleed in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB. Because the study was retrospective and descriptive, we cannot explicitly conclude a treatment effect. Patients who received vitamin K1 were more likely than those who did not receive vitamin K1 to be clinically unstable. This difference in clinical stability may have resulted in the observed differences in pharmacological management at discharge, which in turn may have influenced rebleeding. Prospective randomized studies are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of vitamin K1 for patients with hepatic cirrhosis and UGIB.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Maurice Maslen, Data Analyst with Calgary Zone Clinical Services IT, Alberta Health Services, for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding: None received.

References

- 1.Liver disease in Canada: a crisis in the making. Markham (ON): Canadian Liver Foundation; 2013. Mar, [cited 2018 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.liver.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Liver-Disease-in-Canada-E-3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Live Diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.28906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer AV, Green M, Pautler HM, Kornblat K, Deal EN, Thoelke MS. Impact of vitamin K administration on INR changes and bleeding events among patients with cirrhosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(2):113–7. doi: 10.1177/1060028015617277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldrich SM, Regal RE. Routine use of vitamin K in the treatment of cirrhosis-related coagulopathy: is it A-O-K? Maybe not, we say. P T. 2019;44(3):131–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, et al. International Consensus Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Conference Group. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):101–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martí-Carvajal AJ, Solà I. Vitamin K for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people with acute or chronic liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD004792. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004792.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulman S, Kearon C Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(1):91–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen IC, Hung MS, Chiu TF, Chen JC, Hsiao CT. Risk scoring systems to predict need for clinical intervention for patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):774–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abby-Phillips C, Sahney A. Oseophageal and gastric varices: historical aspects, classification and grading: everything in place. Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;4(3):186–95. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gow018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripodi A, Mannucci PM. The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):147–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northup PG, Caldwell SH. Coagulation in liver disease: a guide for the clinician. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1064–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saja MF, Abdo AA, Sanai FM, Shaikh SA, Gader AGM. The coagulopathy of liver disease: does vitamin K help? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(1):10–7. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835975ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Brancaccio V, Balzano A. Coagulation disorders in liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(1):83–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatten K, Purssell H, Banerjee AK, Soteriadou S, Ang Y. Glasgow Blatchford Score and risk stratifications in acute upper gastrointestinal bleed: can we extend this to 2 for urgent outpatient management? Clin Med (Lond) 2018;18(2):118–22. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-2-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srygley FD, Gerardo CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonardi F, De Maria N, Villa E. Anticoagulation in cirrhosis: a new paradigm? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23(1):13–21. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shingina A, Barkun AN, Razzaghi A, Martel M, Bardou M, Grainek I RUGBE Investigators. Systematic review: the presenting international normalised ratio (INR) as a predictor of outcome in patients with upper nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(9):1010–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivoscecchi RM, Kane-Gill SL, Garavaglia J, MacLasco A, Johnson H. The effectiveness of intravenous vitamin K in correcting cirrhosis-associated coagulopathy. Int J Pharm Prac. 2017;25(6):463–5. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge PS, Runyon BA. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):767–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1504367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandorfer M, Reiberger T. Beta blockers and cirrhosis 2016. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]