Abstract

The U.S. Army’s Standards of Medical Fitness (AR 40-501) states: “Prior burn injury (to include donor sites) involving a total body surface area of 40 percent or more does not meet the standard”. However, the standard does not account for the interactive effect of burn injury size and air temperature on exercise thermoregulation.

Purpose:

To evaluate whether the detrimental effect of a simulated burn injury on exercise thermoregulation is dependent upon air temperature.

Methods:

On eight occasions, nine males cycled for 60 min at a fixed metabolic heat production (6 W·kg−1) in air temperatures of 40°C or 25°C with simulated burn injuries of 0% (Control), 20%, 40%, or 60% of total body surface area (TBSA). Burn injuries were simulated by covering the skin with an absorbent, vapor-impermeable material to impede evaporation from the covered areas. Core temperature was measured in the gastrointestinal tract via telemetric pill.

Results:

In 40°C conditions, greater elevations in core temperature were observed with 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries vs. Control (P < 0.01). However, at 25°C, core temperature responses were not different vs. Control with 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA simulated injuries (P = 0.97). The elevation in core temperature at the end of exercise was greater in the 40°C environment with 20%, 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries (P ≤ 0.04).

Conclusion:

Simulated burn injuries ≥20% TBSA exacerbate core temperature responses in hot, but not temperate, air temperatures. These findings suggest that the U.S. Army’s standard for inclusion of burned soldiers is appropriate for hot conditions, but could lead to the needless discharge of soldiers who could safely perform their duties in cooler training/operational settings.

Keywords: sweat rate, evaporative heat loss, core temperature, heat stress, burn survivor

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 500,000 Americans per year suffer burn injuries (1) and severe burns account for ~10% of battlefield casualties in military conflicts since World War II (2). Based on these figures, U.S. Army policies pertaining to personnel with burn injuries can have an important impact on the recruitment and retention of qualified soldiers. Presently, the U.S. Army’s Standards of Medical Fitness [AR 40–501 (3)] state that “Prior burn injury (to include donor sites) involving a total body surface area of 40% or more does not meet the standard.” This exclusion criterion stems in part from the profound thermoregulatory dysfunction that attends extensive burn injuries and subsequent skin grafting (4-9), which can raise the risk of heat illness in burned Army personnel. Although the percentage of total body surface area injured (%TBSA) is often used to characterize the severity of a burn injury, the thermoregulatory consequences of a burn injury likely depend on a variety of physical factors beyond the relative size of the injury, including the air temperature in which an Army recruit or soldier with a burn injury must perform their duties.

During prolonged physical activity, humans are able to achieve stable elevations in core temperature across a wide range of ambient temperatures provided that the rate of sweat evaporation required to attain heat balance (i.e., the sum of the rates of metabolic heat production and dry heat dissipation) does not exceed the capacity for whole-body evaporative heat dissipation (determined by mean skin temperature, ambient vapor pressure, air velocity, clothing properties, and the extent to which the skin can be saturated with sweat). At a given rate of metabolic heat production, the evaporative requirement for heat balance varies with air temperature due to differences in the skin-air temperature gradient and ensuing differences in the rate of dry heat loss or gain (10-12). The requirement for sweat evaporation is low in cool environments as a wide skin-air temperature gradient enables high rates of dry heat loss. At increasingly higher air temperatures, the requirement for evaporation increases as the skin-air temperature gradient narrows and the corresponding rate of dry heat loss decreases. In hot air temperatures greater than ~35°C, the requirement for sweat evaporation is further augmented, as reversal of the skin-air temperature gradient promotes dry heat gain from the environment. Exposure to such hot conditions may be precarious for burn survivors with extensive skin grafts. Following a burn injury, excision of damaged tissue and the transplantation of split-thickness skin grafts onto wounded sites disrupt the structure and innervation of sweat glands within grafted skin sites. The ensuing suppression of sweat rate within grafted areas (4, 7, 8, 13) limits the absolute surface area of skin that can be saturated with sweat, thus lowering the capacity for whole-body evaporative heat dissipation (9, 14). It follows that for burn survivors with extensive skin grafts who must perform prolonged work in hot conditions, exposure to a high air temperature coupled with a reduced evaporative capacity can induce physiologically uncompensable conditions that exacerbate the rise in core temperature compared to individuals without a burn injury (6). However, it is presently unclear how the size of a burn injury affects the physiological compensability of exercise in different air temperatures. With reference to the U.S. Army’s current standard, it is conceivable that exercise in temperate air temperatures is physiologically compensable among burn survivors with injuries ≥40% TBSA, while exposure to hot air temperatures may be uncompensable even for burn survivors with injuries <40% TBSA. Investigating these possibilities is important to avoid the potentially needless separation of highly-trained soldiers from the Army while simultaneously ensuring the safety and performance of Army personnel with burn injuries.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether the extent to which a burn injury is detrimental to exercise thermoregulation is dependent upon air temperature. Using a simulated burn injury model to replicate the impact of 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA burn injuries on whole-body evaporative heat dissipation during fixed-duration exercise, the following hypotheses were tested: (i) for a given %TBSA injury, elevations in core temperature are greater in a hot environment (40°C) compared to a temperate environment (25°C); (ii) larger %TBSA injuries exacerbate the elevation in core temperature in a hot (40°C), but not a temperate (25°C), environment compared to a non-injured ‘Control’ condition.

METHODS

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, and the Human Research Protections Office of the Defense Health Agency. Participants were fully informed of the study procedures and the potential risks of participation before providing informed written consent. All procedures conformed to standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Nine nonsmoking and physically-active males completed the study. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. Participants were not taking any prescribed medications, and reported no known cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, or neurological disease.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 ± 10 | 20 – 46 |

| VO2peak (L·min−1) | 3.73 ± 0.70 | 2.70 – 4.66 |

| VO2peak (mL·kg–1·min−1) | 51.8 ± 14.0 | 34.0 – 75.1 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 74.30 ± 10.12 | 59.19 – 88.89 |

| Height (m) | 1.79 ± 0.06 | 1.67 – 1.88 |

| Body Surface Area (m2) | 1.92 ± 0.15 | 1.66 – 2.15 |

| Body Mass Index (kg·m−2) | 23.2 ± 2.2 | 20.3 – 26.1 |

Data are means ± standard deviations for nine participants.

VO2peak, peak rate of oxygen uptake.

Measurements

Body mass (Mettler Toledo PBD655-BC120, Toledo, OH) and standing height (Detecto stadiometer, Webb City, MO) measurements were used to calculate body surface area according to the equation of DuBois and DuBois (15). Urine specific gravity (USG) was determined with a refractometer (Atago Inc., Bellevue, WA). Core temperature was measured in the gastrointestinal tract using a telemetric pill ingested ~2 h prior to exercise (HQ Inc., Palmetto, FL). Whole-body sweat losses (WBSL) were determined from changes in body mass, with the extent of dehydration estimated as the percentage body mass loss (%BML). Heart rate was captured from an electrocardiogram (GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI). Core temperature and heart rate responses were recorded throughout the protocol at a sampling frequency of 25 Hz (Biopac MP150, Santa Barbara, CA). Expired gases were analyzed for rates of oxygen consumption (VO2) and CO2 production (VCO2). Metabolic rate (M) was calculated from VO2 and the respiratory exchange ratio (RER, i.e. VCO2/VO2):

The rate of metabolic heat production was calculated as the difference between the metabolic rate and external work rate (Lode Corival, Groningen, Netherlands).

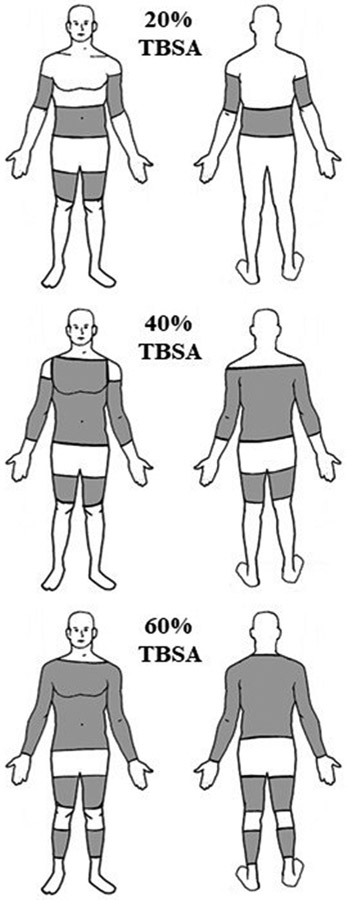

To mimic the effect of a burn injury on whole-body evaporative heat loss, absorbent pads with a vapor-impermeable exterior were cut to the calculated %TBSA (20%, 40%, and 60%) and affixed to the skin on the arms, legs, and torso (Figure 1) using surgical tape (3M Transpore, London, ON) and tubular net bandages (Owens & Minor MediChoice, Mechanicsville, VA). With this approach, secreted sweat is absorbed and sequestered within the absorbent material, preventing evaporative heat loss over the area covered by the absorbent pads.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic showing the standard locations and surface areas covered with absorbent pads to achieve 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries.

Experimental Protocol

Participants visited the laboratory on nine occasions (one preliminary trial and eight experimental trials) separated by at least 48 hours. During the preliminary trial, screening procedures were performed, including a resting 12-lead electrocardiogram and blood pressure measurements. Participants then completed a graded exercise test for the determination of peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) in 20.3 ± 0.7°C and 34.8 ± 1.2% RH conditions. Participants completed three 4-min stages of cycling at workload of increasing intensity to provide a warmup and to predict the workload required to elicit the target rate of metabolic heat production during subsequent experimental visits. After a 10-min rest, the graded exercise test commenced at an external work rate of 1 W·kg−1 of total body mass, and increased by 20 or 25 W·min−1 until volitional exhaustion. The highest 30-s VO2 was taken as the participant’s VO2peak.

Participants completed eight experimental visits, with simulated burn injuries of 0% (Control), 20%, 40%, and 60% in air temperatures of approximately 40°C and 25°C. The order of the experimental trials was randomized, but performed at a similar time of day to avoid the potentially confounding effect of circadian variation. In preparation for each trial, participants were asked to avoid alcohol and strenuous exercise for 24 h, avoid caffeine for 12 h, and to consume a light meal and ~500 ml of water 2 h befog re arrival. At the start of each visit, a urine sample was collected to confirm euhydration, which was accepted based on a urine specific gravity measurement ≤1.025 (16). Participants recorded their nude body mass, and then dressed in a standard clothing ensemble consisting of cotton running shorts, socks, and running shoes. Following instrumentation, including application of the absorbent material over the skin surface to simulate a burn injury, participants entered the environmental chamber. Ambient conditions were 39.5 ± 0.4°C and 21.5 ± 1.9% RH in the hot condition (40°C), and 24.5 ± 0.4°C and 23.1 ± 3.3% RH in the temperate condition (25°C). After a 30-min equilibration period, participants cycled for 60 min at an external work rate that targeted a rate of metabolic heat production of 6.0 W·kg−1 of total body mass, which is similar to the rate of heat production during military foot patrol (17). Measurements of VO2 were taken at rest, and during 0–10, 25–35, and 50–60 min of exercise. Work rate was adjusted as necessary to maintain the target rate of heat production. Participants were permitted to consume water maintained at body temperature ad libitum. Upon completion of the exercise task, participants were de-instrumented and again recorded their nude body mass.

Data and Statistical Analyses

Core temperature and heart rate data were analyzed as average values collected over 2-min time periods ending at 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min of exercise. In one participant, core temperature reached the upper ethical limit of 39.5°C before completing the exercise protocol in the 40°C environmental condition with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury. Given the physiologically uncompensable nature of the experimental conditions, and thus the fixed-rate linear increase in core temperature over time (18), a 60-min core temperature value for this participant was imputed based on the observed rate of change in core temperature from 15 to 45 min of exercise during this trial. Data are reported throughout as means ± standard deviations.

For each air temperature, a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the repeated factors of time (five levels: 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min) and %TBSA simulated burn injury (four levels: Control, 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA) was performed to compare elevations in core temperature and heart rate. In the event of a significant %TBSA-by-time interaction, post hoc analyses were performed using a Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. For each %TBSA, end-exercise core temperature and heart rate values were compared between 25°C and 40°C air temperatures using paired t-tests. Additionally, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to compare WBSL and %BML, with a Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) with alpha set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Across all experimental trials, the external work rate averaged 100 ± 7 W, eliciting a rate of metabolic heat production of 6.0 ± 0.6 W·kg−1 and corresponding to a relative intensity of 43.5 ± 8.5% of VO2peak.

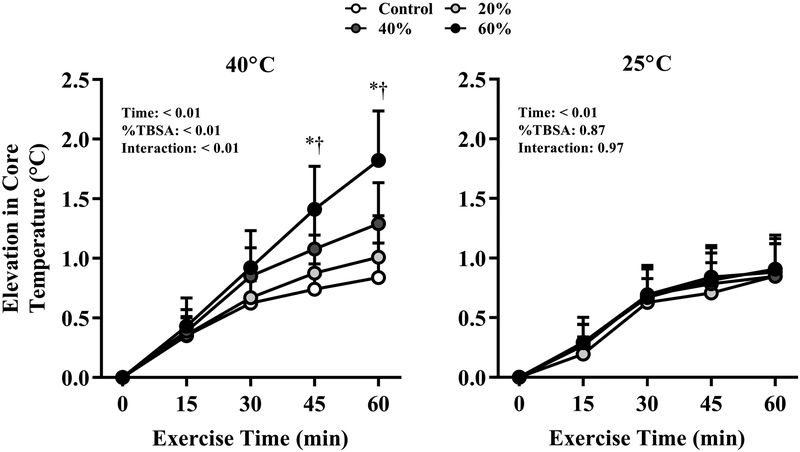

Figure 2 shows the time-dependent elevations in core temperature at each %TBSA simulated burn injury during exercise in air temperatures of 40°C and 25°C. Compared to the Control condition, in the 40°C environment the elevation in core temperature was greater with 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries at 45 and 60 min (P ≤ 0.04). However, core temperature responses were not different across any %TBSA in the 25°C environment. End-exercise elevations in core temperature were significantly greater in the 40°C environment compared to the 25°C environment for the 20%, 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries (P ≤ 0.04), but not in the Control trial (P = 0.70).

FIGURE 2.

Elevations in core temperature after 60 min of exercise in air temperatures of 40°C (left) and 25°C (right) with simulated burn injuries of 20%, 40%, or 60% total body surface area, as well as a Control condition (i.e., no simulated burn injury). *Significantly greater with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury vs. Control at the indicated time point. †Significantly greater with a 40% TBSA simulated burn injury vs. Control at the indicated time point. Data represent means ± standard deviations for nine participants.

Table 2 shows WBSL and %BML values. Greater WBSL and %BML were observed at 40°C vs. 25°C for each %TBSA simulated burn injury level (P ≤ 0.01). Within the 40°C environment, WBSL and %BML were greater with 60% simulated burn injuries vs. Control (P ≤ 0.01). At 25°C, WBSL and %BML were higher in all simulated burn injury condition compared to Control (P ≤ 0.01).

Table 2.

Sweat losses and dehydration.

| Air Temperature |

%TBSA Simulated Burn Injury | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 20% | 40% | 60% | ||

| WBSL (g) | 40°C | 1210 ± 195* | 1270 ± 215* | 1465 ± 282* | 1690 ± 384*† |

| 25°C | 607 ± 99 | 690 ± 113† | 782 ± 109† | 915 ± 159† | |

| %BML | 40°C | 1.7 ± 0.3* | 1.7 ± 0.3* | 2.0 ± 0.5* | 2.3 ± 0.7*† |

| 25°C | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2† | 1.1 ± 0.2† | 1.3 ± 0.3† | |

Data are means ± standard deviations for nine participants.

%TBSA, percentage of total body surface area.

WBSL, whole body sweat losses.

%BML, percentage body mass loss.

Greater in 40°C vs. 25°C at the same %TBSA.

Greater than Control at the same air temperature.

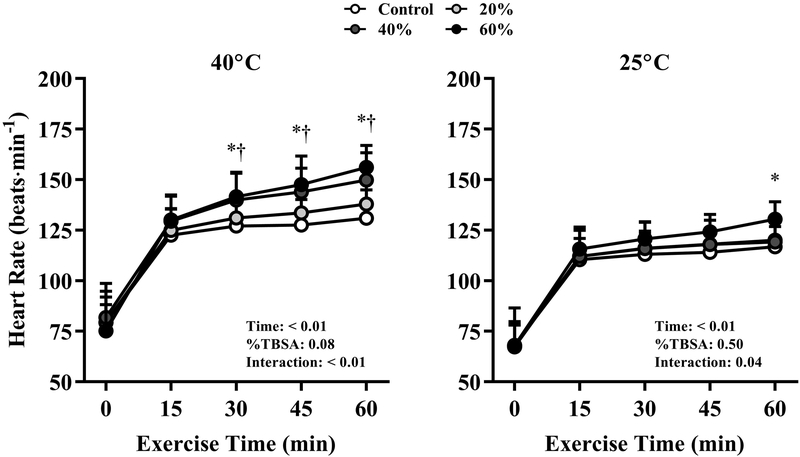

Heart rate responses at the 40°C and 25°C air temperatures with each %TBSA simulated burn injury are presented in Figure 3. At 40°C, heart rate was significantly elevated with 40% and 60% simulated burn injuries compared to Control at each time point from 30 to 60 min of exercise (P ≤ 0.04). In the 25°C environment, heart rate was significantly greater at 60 min compared to Control with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury only (P = 0.02). At the end of exercise, heart rate was significantly elevated at every %TBSA level in 40°C compared to 25°C (P < 0.01).

FIGURE 3.

Heart rate responses throughout 60 min of exercise in air temperatures of 40°C (left) and 25°C (right) with simulated burn injuries of 20%, 40%, or 60% total body surface area, as well as a Control condition (i.e., no simulated burn injury). *Significantly greater with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury vs. Control at the indicated time point. †Significantly greater with a 40% TBSA simulated burn injury vs. Control at the indicated time point. Data represent means ± standard deviations for nine participants.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the interactive effect of air temperature (hot: 40°C; temperate: 25°C) and burn injury size (no injury, 20%, 40%, and 60% of TBSA) on core temperature responses to prolonged exercise. The results show that simulated burn injuries of 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA exacerbate the elevation in core temperature during moderate-intensity exercise in a 40°C environment compared to a 25°C environment. Additionally, 40% and 60% TBSA simulated injuries caused higher elevations in core temperature compared to a Control (non-injured) condition within a 40°C environment, but the elevation in core temperature with 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries in a 25°C environment was not different than that observed in a non-injured Control condition. Overall, these findings indicate that the detrimental effect of a burn injury on exercise thermoregulation is influenced by air temperature. As such, the current U.S. Army standard for inclusion of recruits/soldiers with burn injuries should perhaps consider the air temperature in which that recruit or soldier will perform their duties.

Only one study to date has examined the relationship between air temperature and the %TBSA injured among individuals with burn injuries, vis à vis core temperature responses to prolonged exercise. Roskind et al. (6) assessed the upper bound of the ‘prescriptive zone’—the upper air temperature limit for physiological compensability (19)—among groups of burn survivors with injuries spanning an average of 9% (N=4), 17% (N=2), or 46% (N=2) of TBSA. In that study, 60 min of exercise was performed at an intensity eliciting ~4 W·kg−1 of metabolic heat production under corrected effective temperatures of 15–30°C, corresponding to dry-bulb temperatures of ~18–36°C with 50% RH and negligible air flow (20). The upper bound of the prescriptive zone for burn survivors with smaller injuries of 9% and 17% TBSA was found to be an air temperature of ~33°C and similar to that reported for individuals without a burn injury, but only ~28°C for burn survivors with a 46% TBSA injury, indicating that larger burn injuries diminish the critical air temperature above which a heat load becomes uncompensable. Although the current study did not set out to define prescriptive zone boundaries for burn survivors based on the %TBSA injured, and used different experimental conditions of ambient humidity and exercise intensity, the present results show a similar pattern to those of Roskind et al. (6). Specifically, the physiological compensability of moderate-intensity exercise was dependent on the prevailing air temperature at higher %TBSA burn injuries.

Maintenance of heat balance—and thus a stable elevation in core temperature—during exercise depends on the rate of sweat evaporation required for heat balance, which varies with air temperature for a given exercise intensity (i.e., rate of metabolic heat production) (10-12), and the capacity for evaporative heat dissipation. In cool/temperate air temperatures, the skin-air temperature gradient favors dry heat loss via convection and radiation, which lowers the requirement for sweat evaporation. In ambient air temperatures greater than ~35°C, the skin-air temperature gradient promotes dry heat gain, exacerbating the requirement for evaporative heat loss. In burn survivors, the ability to compensate for the additional heat load imposed by exposure to a hot environment compared to a temperate environment should depend on the magnitude of the reduction in the capacity for evaporative heat dissipation, secondary to the absolute skin surface area available for heat dissipation. In the present study, the core temperature responses in the Control conditions were not different between air temperatures of 40°C and 25°C, but significantly greater with 20%, 40%, and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries when the air temperature was 40°C (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that with burn injuries ≥20% TBSA, the reduction in evaporative heat loss potential is sufficiently large such that the rate of sweat evaporation required to balance the thermal load associated with exercise in hot vs. temperate conditions could not be achieved.

In the 25°C environment, elevations in core temperature were similar across %TBSA simulated burn injuries compared to Control (Fig. 1), indicating that exercise in a temperate environment produced a thermal load that was effectively compensated despite reductions in the skin surface area for evaporative heat dissipation up to 60% of TBSA. In the 40°C environment, greater elevations in core temperature were observed with 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries vs. Control despite the same total heat load, indicating that at these %TBSA, the capacity for evaporative heat dissipation is reduced to the extent that the thermolytic requirements associated with this combination of metabolic/environmental heat stress could not be met. It has been previously demonstrated that in well-healed burn survivors performing exercise in the heat, elevations in core temperature are strongly associated with the skin surface area available for evaporative heat dissipation (i.e., the skin surface area of non-injured skin) (5). The current data extend these observations, indicating that the limit of physiological compensability during moderate-intensity exercise in hot-dry conditions with minimal clothing occur at ~20% TBSA or, based on the participants tested in this study, an absolute skin surface area available for evaporation heat dissipation of ~1.5 m2 (Table 1).

Heart rate was assessed to examine the interactive effect of air temperature and the %TBSA burn injury on cardiovascular strain. Heart rate was greater with 40% and 60% TBSA simulated burn injuries vs. Control in the 40°C environment from 30–60 of exercise (Fig. 2), and end-exercise heart rate was greater in 40°C vs. 25°C in each %TBSA condition. The increase in heart rate during prolonged fixed-intensity exercise is heightened in hot vs. temperate conditions (21-24), which reflects the direct influence of internal temperature on sinoatrial and atrioventricular node firing rates, as well as sympathetic and parasympathetic effects on cardiac pacemaker cells (25-27). Thus, heart rate responses to exercise in the heat follow a similar pattern to that of core temperature across %TBSA injury levels. Additionally, end-exercise heart rate was greater with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury vs. Control in the 25°C environment despite similar elevations in core temperature between conditions. In addition to increased core temperature, heart rate also increases with skin temperature during exercise (28) to support the greater skin blood flow requirement that attends a narrow core-skin thermal gradient (29, 30). The absorbent material used to simulate a burn injury would have restricted dry and evaporative heat loss to a greater extent with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury compared to the Control condition, likely resulting in a greater mean skin temperature and a consequently greater heart rate response. Whether burn survivors with large %TBSA injuries exhibit similar skin temperature-dependent alterations in the heart rate response to exercise in a temperate environment is unknown.

Whole-body sweat losses and the percentage dehydration were greater at 40°C compared to 25°C (Table 2). Additionally, sweat losses and the percentage dehydration were greater with a 60% TBSA simulated burn injury in the 40°C environment, but greater in all three simulated burn injury conditions compared to Control at 25°C (Table 2). Whole-body sweat production is associated with the evaporative requirement for heat balance (10-12) and inversely related to the maximum potential for evaporation (14, 31). At each %TBSA, exercise in 40°C vs. 25°C would have led to a skin-air thermal gradient that favors dry heat gain, resulting in greater sweat production to meet a higher evaporative requirement for heat balance. When comparing sweat losses and dehydration levels within each air temperature, higher %TBSA simulated burn injuries would have reduced the maximum potential for evaporation, necessitating additional sweat production in attempt to meet the evaporative requirement for heat balance (32).

Perspectives

The U.S. Army’s current Standards of Medical Fitness disqualifies recruits and soldiers with burn injuries ≥40% TBSA. The present findings suggest that a U.S. Army soldier with a burn injury of ≥20% TBSA performing continuous moderate-intensity work in a hot environment will experience greater elevations in core temperature and thus be at a greater risk of heat illness compared to an individual without a burn injury. In contrast, work at the same intensity conducted in a temperate environment (i.e., 25°C) would be physiologically compensable even with a large burn injury of 60% TBSA. In such cases, recruits or soldiers with large burn injuries (up to 60% TBSA) could be retained but assigned to cooler climates without incurring additional heat illness risk compared to soldiers with smaller burn injuries or those without burn injuries. Therefore, the present findings could inform a nuanced revision of the Standard to prevent soldiers with large burn injuries from participating in training/operations in hot conditions, but allow participation in such activities in temperate or cool conditions. Such an update to the Standards of Medical Fitness could potentially avoid the needless discharge of otherwise qualified recruits and highly-trained active-duty personnel who pose no additional risk to themselves or others. However, any such revision to the Standard will also need to consider other important physical (e.g., humidity, work intensity) and physiological (e.g., aerobic fitness, heat acclimatization status) factors, which are discussed below.

The results of the present study could also be used to recommend environmental exposure limits for burn survivors partaking in post-injury exercise training. Exercise is an important component of rehabilitation following a burn injury (34), but heat intolerance is a major problem in well-healed burn survivors (35). Based on the present findings, clinicians and trainers should remind burn survivors with very high %TBSA injuries (i.e., 60% TBSA) that during hotter months, moderate-intensity activities should be performed at cooler parts of the day, in climate-controlled environments, or for a shorter duration if conducted in the heat, while those burn survivors with low %TBSA injuries could safely perform the same activities at hotter ambient temperatures. However, in temperate climate conditions (e.g., ~25°C), individuals with burn injuries up to 60% TBSA could safely perform exercise at a mild-to-moderate intensity without an added risk of a heat-related illness.

Considerations

One participant completed only 45 min of the 60-min exercise protocol after reaching the cut-off for core temperature of 39.5°C set by the Institutional Review Board during the 40°C / 60% TBSA experimental condition. Since core temperature increases linearly under physiologically uncompensable conditions (18), the missing 60-min data point was replaced with an imputed value based on a rate of change in core temperature of 0.03°C·min−1 leading up to the 45-min time point. Compared to the responses with the imputed value (see Figure 1), re-analysis of the dataset following removal of this participant’s data would have slightly altered the mean 60-min change in core temperature in the 40°C environment (Control: 0.76 ± 0.19°C; 20%: 0.93 ± 0.27°C; 40%: 1.26 ± 0.36°C; 1.74 ± 0.36°C), but the 60-min elevation in core temperature would have remained significantly different in 40°C vs. 25°C at the 40% and 60% TBSA levels, and between the 40% and 60% TBSA levels vs. Control in the 40°C environment.

The application of absorbent pads restricted evaporation from the covered skin sites, but also created a barrier to dry heat exchange, which would have reduced the rate of dry heat dissipation via convection and radiation compared to grafted skin in the 25°C environment. It is noteworthy, however, that the impact of restricting dry heat loss in the 25°C environment was insufficient to alter the compensability of the experimental conditions, as no differences in the elevations in core temperature across %TBSA conditions were observed (Fig. 1). In the 40°C environment, the insulation of the absorbent pads would have resisted body heat gain via convection and radiation, but the overall effect would have been minimal given the narrow skin-air temperature gradient between the environmental and the covered skin surface (~2°C).

The present study was conducted at only one exercise intensity, set to a rate of metabolic heat production typically observed during moderate-intensity military activities (17, 36). Metabolic heat is the principal heat source during prolonged exercise, and thus the main driver of core temperature responses (11, 37) and the rate of evaporative heat dissipation required for heat balance (10, 38). Therefore, the results of the present experiment are dependent on the exercise intensity selected. Relative humidity was set to 20% at both air temperatures, making the current findings applicable in dry conditions only. Higher humidity levels would have led to a lower capacity for evaporative heat loss at every %TBSA simulated burn injury, and likely would have minimized the differences between %TBSA conditions. It should be noted that the same relative humidity at different air temperatures leads to different ambient vapor pressures, and that the drive for evaporative heat loss is determined in part by ambient vapor pressure, not relative humidity per se. Finally, environmental limits to physiological compensability are affected by both aerobic fitness (i.e., VO2peak) as well as heat acclimation (39). The participants included in this study were active individuals, but were not acclimated to the heat prior to testing. Undertaking heat acclimation prior to the study may not have altered the core temperature responses at 25°C, but a greater capacity for evaporative heat loss induced by heat acclimation would have led to a smaller elevation in core temperature at 40°C, particularly with the simulated burn injuries. Although heat acclimation improves thermoregulatory capacity in burn survivors (40), the implications of heat acclimation on the Army’s Standards of Medical Fitness pertaining to burn survivors has not been examined.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated the core temperature responses to prolonged exercise in hot (40°C) and temperate (25°C) air temperatures with simulated burn injuries of 20%, 40%, and 60% of total body surface area, as well as Control condition (i.e., no simulated burn injury). Simulated burn injuries of 20%, 40%, and 60% of total body surface area led to significantly elevated core temperature in 40°C vs. 25°C conditions, and greater core temperature responses compared to the non-injured Control condition in the 40°C environment. In the 25°C environment, the elevation in core temperature was not different between each simulated burn injury level and the non-injured Control condition. Since the detrimental effect of a burn injury on exercise thermoregulation is influenced by air temperature, our findings suggest that the air temperature in training and operational settings may be an important consideration when determining whether a U.S. Army soldier or recruit with a burn injury meets the Standards of Medical Fitness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are sincerely grateful to the study volunteers for their time and effort. We thank Amy Adams, Sarah Bailey, Manall Jaffery, Naomi Kennedy, Kelly Lenz, and Jan Petric for their contributions to the study. We also thank Ollie Jay for his input toward the experimental design, as well as Michael Kohl for composing the image in Figure 1. This work was supported by awards from the Department of Defense (W81XWH-15–1-0647 to C.G.C.), National Institutes of Health (R01GM068865 to C.G.C.), and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Postdoctoral Fellowship (to M.N.C.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Burn Association. 2016 National Burn Repository: Report of Data from 2006–2015. Chicago, IL: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancio LC, Horvath EE, Barillo DJ, et al. Burn support for Operation Iraqi Freedom and related operations, 2003 to 2004. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26(2):151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of the Army. Army Regulation 40–501. Standards of Medical Fitness. 2007.

- 4.McGibbon B, Beaumont WV, Strand J, Paletta FX. Thermal regulation in patients after the healing of large deep burns. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;52(2):164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganio MS, Schlader ZJ, Pearson J, et al. Nongrafted Skin Area Best Predicts Exercise Core Temperature Responses in Burned Humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(10):2224–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roskind JL, Petrofsky J, Lind AR, Paletta FX. Quantitation of thermoregulatory impairment in patients with healed burns. Ann Plast Surg. 1978;1(2):172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, et al. Impaired cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in grafted skin during whole-body heating. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(3):427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis SL, Shibasaki M, Low DA, et al. Sustained impairments in cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in grafted skin following long-term recovery. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(4):675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganio MS, Gagnon D, Stapleton J, Crandall CG, Kenny GP. Effect of human skin grafts on whole-body heat loss during exercise heat stress: a case report. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34(4):e263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnon D, Jay O, Kenny GP. The evaporative requirement for heat balance determines whole-body sweat rate during exercise under conditions permitting full evaporation. J Physiol. 2013;591(Pt 11):2925–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen M Die regulation der korpertemperatur bei muskelarbeit. Skand Arch Physiol. 1938;79:193–230. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen B, Nielsen M. On the regulation of sweat secretion in exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 1965;64:314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway H Sweating Function of Transplanted Skin. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1939;69:756–61. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro Y, Epstein Y, Ben-Simchon C, Tsur H. Thermoregulatory responses of patients with extensive healed burns. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53:1019–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DuBois D, DuBois EF. A formula to estimate surface area if height and weight are known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17:863–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheuvront SN, Ely BR, Kenefick RW, Sawka MN. Biological variation and diagnostic accuracy of dehydration assessment markers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau WM, Roberts W, Forbes-Ewan C. Physiological performance of soldiers conducting long range surveillance and reconnaissance in hot, dry environments. Melbourne, Australia: DSTO Aeronautical and Maritime Research Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravanelli N, Cramer M, Imbeault P, Jay O. The optimal exercise intensity for the unbiased comparison of thermoregulatory responses between groups unmatched for body size during uncompensable heat stress. Physiol Rep. 2017;5(5):e13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lind AR. A physiological criterion for setting thermal environmental limits for everyday work. J Appl Physiol. 1963;18:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedford T Environmental Warmth and its Measurement Medical Research Council War Memorandum no. 17. London: HMSO; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galloway SD, Maughan RJ. Effects of ambient temperature on the capacity to perform prolonged cycle exercise in man. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:1240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Périard JD, Caillaud C, Thompson MW. The role of aerobic fitness and exercise intensity on endurance performance in uncompensable heat stress conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(6):1989–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams CG, Bredell GA, Wyndham CH, et al. Circulatory and metabolic reactions to work in heat. J Appl Physiol. 1962;17:625–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowell LB, Marx HJ, Bruce RA, Conn RD, Kusumi F. Reductions in cardiac output, central blood volume, and stroke volume with thermal stress in normal men during exercise. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1801–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark AJ. The effect of alterations of temperature upon the functions of the isolated heart. J Physiol. 1920;54(4):275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jose AD, Stitt F, Collison D. The effects of exercise and changes in body temperature on the intrinsic heart rate in man. Am Heart J. 1970;79(4):488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crandall CG, Wilson TE. Human cardiovascular responses to passive heat stress. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(1):17–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JM. Regulation of skin circulation during prolonged exercise. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977;301:195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowell LB. Circulatory adjustments to dynamic exercise and heat stress: competing controls Human Circulation: Regulation during Physical Stress. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. p. 363–406. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawka MN, Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW. High skin temperature and hypohydration impair aerobic performance. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(3):327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bain AR, Deren TM, Jay O. Describing individual variation in local sweating during exercise in a temperate environment. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer MN, Jay O. Compensatory hyperhidrosis following thoracic sympathectomy: a biophysical rationale. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R352–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montain SJ, Coyle EF. Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1340–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter C, Hardee JP, Herndon DN, Suman OE. The role of exercise in the rehabilitation of patients with severe burns. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2015;43(1):34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holavanahalli RK, Helm PA, Kowalske KJ. Long-term outcomes in patients surviving large burns: the skin. J Burn Care Res Off Publ Am Burn Assoc. 2010;31(4):631–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawka MN, Pandolf KB. Physical Exercise in Hot Climates: Physiology, Performance, and Biomedical Issues Medical Aspects of Harsh Environments. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Army; 2002. p. 87–133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jay O, Bain AR, Deren TM, Sacheli M, Cramer MN. Large differences in peak oxygen uptake do not independently alter changes in core temperature and sweating during exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R832–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cramer MN, Jay O. Explained variance in the thermoregulatory responses to exercise: the independent roles of biophysical and fitness/fatness-related factors. J Appl Physiol. 2015;119(9):982–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravanelli N, Coombs GB, Imbeault P, Jay O. Maximum Skin Wettedness after Aerobic Training with and without Heat Acclimation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(2):299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlader ZJ, Ganio MS, Pearson J, et al. Heat acclimation improves heat exercise tolerance and heat dissipation in individuals with extensive skin grafts. J Appl Physiol. 2015;119(1):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]