Abstract

Background

The social, normative nature of alcohol use may make college students with social anxiety vulnerable to problematic alcohol use. Yet, social anxiety is typically unrelated to drinking quantity or frequency. One potential explanation is that researchers primarily use a variable-centered approach to examine alcohol use among students with social anxiety, which assumes population homogeneity.

Methods

The current study utilized a person-centered approach to identify distinct classes among 674 college students (69.6% female) based on social anxiety characteristics and alcohol use behaviors, and tested how these classes differed in their experience of adverse outcomes.

Results

Latent profile analysis resulted in six distinct classes of students - two classes with low levels of social anxiety and non-problematic drinking behaviors that differed based on frequency of alcohol use, three classes with moderate levels of social anxiety that differed based on quantity, frequency, and extent of problematic drinking behaviors, and one class with high levels of social anxiety and low, frequent problematic drinking behaviors. Two classes - moderate levels of social anxiety and heavy, problematic drinking behaviors or high levels of social anxiety and light, problematic drinking behaviors - appeared to have riskier profiles due to endorsing more social anxiety-specific beliefs about social impressions while drinking and more emotional distress.

Conclusions

Current findings offer clarity surrounding the role of alcohol use in the association between social anxiety and problematic alcohol use. Although preliminary, findings demonstrate that comorbid social anxiety and alcohol use disorder symptoms appear to place students at greater risk for adverse outcomes.

Keywords: social anxiety, alcohol use, college students, person-centered analysis

Social anxiety and alcohol use disorders often co-occur such that nearly 50% of individuals with social anxiety disorder (SAD) have co-occurring alcohol use disorder (AUD), and the onset of social anxiety symptoms tends to predate the onset of AUD symptoms (Buckner, Timpano, Zvolensky, Sachs-Ericsson, & Schmidt, 2008). Among college students with a past-year anxiety disorder, phobia disorders are the most prevalent (9–11%; Auerbach et al., 2016), and one study found past-year prevalence of SAD was 7.9% (Izgic, Akyuz, Dogan, & Kugu, 2004). College students with social anxiety may be particularly vulnerable to problematic alcohol use given their tendency to experience heightened physiological arousal and psychological distress in social evaluative situations (Kashdan & Steger, 2006). Book and Randall (2002) highlight that students with social anxiety tend to make decisions based on their social fears, impacting academic, social and emotional functioning. Although social avoidance is the primary coping strategy, coping-motivated alcohol use is common among students (Buckner & Heimberg, 2010). Therefore, students with social anxiety may be more susceptible to engage in problematic alcohol use to reduce anxiety or to manage social impressions.

The self-medication hypothesis is commonly referenced to explain co-occurring social anxiety and alcohol use (Carrigan & Randall, 2003). Accordingly, researchers have found positive alcohol expectancies (e.g., beliefs that alcohol will reduce stress) and negative reinforcement drinking motives (e.g., drink to reduce negative affect) explain the relationship between social anxiety and problematic alcohol use (Ham, Bacon, Carrigan, Zamboanga, & Casner, 2016; O’Hara, Armeli, & Tennen, 2015). Yet, Schry and White (2013) found differential associations between social anxiety and alcohol-related outcomes, such that students with social anxiety endorse more hazardous drinking and negative drinking consequences regardless of their rates of alcohol use. While seemingly paradoxical, the college student literature has primarily evaluated social anxiety and alcohol-related outcomes using a variable-centered approach, which assumes population homogeneity (Jung & Wickrama, 2008). Examining the heterogeneity of social anxiety in relation to alcohol use behaviors may help inform student risk for adverse consequences.

Social anxiety symptoms can arise across social situations (e.g., attending social gatherings; performing behaviors in public) and college students with more severe social anxiety tend to endorse alcohol use in social interactions as compared to social performance situations (Villarosa-Hurlocker, Whitley, Capron, & Madson, 2017). Additionally, social anxiety is a multidimensional construct, comprising perceived social deficits, evaluative fears, social avoidance, physiological arousal, and low positive affect and reliance on alcohol may vary based on these dimensions (Buckner, Heimberg, Ecker, & Vinci, 2013). Prior research has found students with social anxiety endorse alcohol use to cope (Buckner & Heimberg, 2010), to fit in with peers (Lewis et al., 2008), and to increase positive mood (Villarosa, Madson, Zeigler-Hill, Noble, & Mohn, 2014). Thus, examining the dimensions and contexts of social anxiety can further inform student drinking patterns.

Given the heterogeneity of social anxiety and its relation to alcohol use behaviors, novel methods for conceptualizing and evaluating comorbidity are warranted. Most empirical studies have evaluated social anxiety using total scores on self-report measures in relation to alcohol use behaviors. Less is known about the individual patterns of social anxiety and alcohol use behaviors. As such, person-centered approaches may be a valuable alternative (Collins & Lanza, 2010) given their ability to examine participant response patterns and establish distinct latent classes based on observed mean scores on indicator variables. Specifically, latent profile analysis (LPA) is a flexible person-centered approach, such that class membership is probabilistic, meaning class membership size takes into account participant probability of fitting into each of the classes.

Only one prior study, to our knowledge has utilized a person-centered approach to establish distinct profiles of students based on social anxiety and alcohol use. Brook and Willoughby (2016) found five distinct classes - high social anxiety-high alcohol use, high social anxiety-low alcohol use, moderate social anxiety-low alcohol use, low social anxiety-high alcohol use, and low social anxiety-moderate alcohol use. These findings highlight that, contrary to variable-centered findings, certain subgroups of students with social anxiety engage in high levels of alcohol use. However, the authors only used one measure of social anxiety and did not evaluate the composition of alcohol use behaviors (i.e., consumption, hazardous drinking, and negative drinking consequences). Expanding on their work, it is important to determine if there are distinct profiles of students based on social anxiety dimensions and alcohol use behaviors, and whether these distinct student profiles differ in their experience of cognitive, emotional, and academic outcomes.

Purpose of Study

The current study is a secondary analysis of data from a project of cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors that underlie social anxiety and drinking patterns of college students (Villarosa-Hurlocker, Madson, Zeigler-Hill, Mohn, & Nicholson, 2018). The purpose of this study was to identify distinct classes of students based on social anxiety characteristics and alcohol use behaviors. The multidimensionality of social anxiety reflects its heterogeneity, and a comprehensive evaluation of social anxiety and alcohol use behaviors may aid in identifying those students at greatest risk. The goals of the study were threefold. First, we identified distinct classes of students based on three of the five social anxiety dimensions (i.e., perceived social deficits in two situation types [interaction and performance social anxiety]; physiological arousal; and evaluation fears; Buckner et al., 2013) and alcohol use behaviors (i.e., quantity/frequency of alcohol use; hazardous drinking; and negative drinking consequences). Second, we explored whether participant gender and age predicted likelihood of class membership. Prior evidence has found gender and age differences in anxiety and alcohol use behaviors among college students (e.g., Gross, 1993; Misra & McKean, 2000), suggesting significant differences in class membership across these variables may emerge. Finally, we evaluated mean differences in cognitive (i.e., beliefs about social impressions while drinking), emotional (e.g., depression) and academic (i.e., GPA) outcomes across classes.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 674 traditional-age college students (69.6% female; M=20.07; SD=1.52) from a mid-size Southeastern university who endorsed alcohol use in the past month. Students were recruited through SONA, an online data management system, and received research credit in exchange for their participation. Although SONA is used in several psychology classes, the majority of participants are recruited from the introduction to psychology course, which is part of the university general education curriculum and is representative of the undergraduate population of the university. Eligible participants were directed to a secure website (Qualtrics) to sign an electronic, IRB-approved consent document and completed measures on mental health and alcohol use variables. Most participants were freshmen (36.4%), followed by sophomore (24.7%), junior (22.9%), and senior (16%). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was White, non-Hispanic (62.7%), African American/Black (29.5%), Hispanic (1.8%), American Indian/Alaska Native (1.2%), Asian (1%), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.4%), and Other (3.3%).

Measures

Social anxiety indicators

The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) and the Social Phobia Scale (SPS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) are companion measures designed to evaluate the perceived social deficits dimension of social anxiety in two social contexts. The 20-item SIAS assesses severity of interaction fears (“I have difficulty making eye contact with others”), and the 20-item SPS assesses severity of performance-related fears (“I get tense when I speak in front of other people”). Both measures have response scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), with higher scores indicative of more social anxiety symptoms. A score of 34 or higher on the SIAS and 24 or higher on the SPS is indicative of clinically-indicated levels of social anxiety (Brown et al., 1997; Heimberg, Mueller, Holt, Hope, & Liebowitz, 1992). The internal consistencies were good with the current sample (SIAS=.92; SPS=.95).

The 8-item Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation (BFNE; Rodebaugh et al., 2004) is an abbreviated version of the original FNE scale (Leary, 1983), that assesses the evaluative fears dimension of social anxiety (“I am afraid that people will not approve of me”). Participants respond using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (Extremely characteristic of me), with higher scores indicative of more evaluative fears. A score of 25 or higher on the BFNE is indicative of clinically-indicated levels of social anxiety (Carleton, Collimore, McCabe, & Antony, 2012). The internal consistency of the BFNE was good in the current sample (α=.94).

The 18-item Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986) evaluates the physiological arousal dimension of anxiety by assessing anxiety sensitivity in three domains. The ASI - social concerns domain was used in the current study to assess the physiological arousal dimension of social anxiety (“When I tremble in the presence of others, I fear what people might think of me”). Participants respond using a five-point scale ranging from 0 (Very little) to 4 (Very much) with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety sensitivity. The internal consistency of the ASI-social was adequate with the current sample (α=.79).

Alcohol use indicators

Average weekly alcohol use was assessed with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Park, & Marlatt, 1985). Respondents indicate the number of standard alcoholic beverages, on average, they consumed each day of the week during the past month. Number of standard drinks per day were summed to obtain the number of drinks consumed in a typical week (DDQ-Q) and number of drinking days were summed to obtain the frequency of alcohol use in a typical week (DDQ-F).

Hazardous drinking was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). The AUDIT is a 10-item, self-report screener for hazardous drinking (“How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion”). A score of 8 or higher is indicative of hazardous/harmful drinking (Reinert & Allen, 2002). The internal consistency for the AUDIT was good with the current sample (α=.81).

Negative drinking consequences were evaluated using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). The RAPI is a 23-item, self-report measure that assesses the frequency of negative consequences using a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (> 10 times), with higher scores indicating more consequences. The internal consistency for the RAPI was good with the current sample (α=.95).

Auxiliary variables

We assessed empirically-supported auxiliary variables surrounding cognitive, emotional, and academic factors. The cognitive and emotional measures are psychometrically strong and have been validated with college student populations (Buckner & Matthews, 2012; Osman et al., 2012). The academic measure was a single item asking participants to indicate their current GPA.

The 35-item Social Impressions while Drinking Scale (SIDS; Buckner & Matthews, 2012) was used to assess beliefs around others impressions of drinking among individuals with social anxiety. Respondents answer items with the stem “If I were drinking alcohol, others would think I...” using a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). Four of the subscales were included in the current study given their direct correspondence with the four social anxiety measures: interaction fears (SIDS-IF; “I feel I’ll say something embarrassing when talking”), observation fears (SIDS-OF; “I am worried that people will think my behavior odd”), evaluation fears (SIDS-EF; “I’m worried about the kind of impression I make”), and tension-reduction (SIDS-TR; “I’m less tense when I speak in front of people”). Internal consistencies for the subscales were adequate (SIDS-IF=88; SIDS-OF=.84; SIDS-EF=.91; SIDS-TR=.77)

Three facets of emotional distress were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The DASS is a 21-item, self-report measure that assesses the severity of emotional distress using a response scale ranging from 0 (Did not apply to me at all) to 3 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time). Three subscales are derived from the DASS - Depression (DASS-D; “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to”), Anxiety (DASS-A; “I felt scared without any good reason”), and Stress (DASS-S; “I found it hard to wind down”). Internal consistencies for the subscales were adequate (DASS-D=.91; DASS-A=87; DASS-S=87).

Analytic plan

A latent profile analysis (LPA) was performed to evaluate distinct profiles of social anxiety and alcohol use behaviors using M-plus (Muthen & Muthen, 2017). In this study, latent profiles were evaluated based on social anxiety constructs (i.e., SIAS, SPS, BFNE, ASI-S) and alcohol use behaviors (i.e., DDQ-Q, DDQ-F, AUDIT, RAPI). Latent models for eight different class solutions were evaluated, and two indicators of model fit were used to determine the optimal class solution (i.e., Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC] and Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test [LMRT]). Lower values on the BIC are indicative of a better-fitting model, and a significant difference on the LMRT between class solutions (i.e., k vs. k −1) are indicative that k class solution is a superior fit than the k −1 class solution (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthen, 2007). Finally, model entropy was evaluated to determine accuracy of classification with the current data. Entropy values range from 0 to 1, with a score of .8 or higher indicative of adequate classification precision. Standardized parameters were estimated using full information maximum likelihood to account for missing data, and parameters of interest were prevalence and conditional response means for each class.

An evaluation of demographic characteristics (age, gender) that likely associate with class membership was performed using a three-step maximum likelihood method that analyzes predictors of latent classes while accounting for classification error in the original measurement model (Vermunt, 2010). We also evaluated differences in auxiliary variables (beliefs about social drinking, emotional distress, and GPA) using the BCH method, which estimate means of auxiliary variables across latent classes, taking into account classification error (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of social anxiety and alcohol use behavior indicators are reported in Table 1. The sample endorsed relatively high levels of social anxiety and hazardous drinking. Specifically, 35% of the sample exceeded the cutoff score on the SIAS, 45.5% exceeded cutoff score on the SPS, and 24.8% exceeded cutoff scores on the BFNE. Further, 38.7% exceeded the cutoff score on the AUDIT.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of LPA indicators

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SIAS | ||||||||

| 2. SPS | .67** | |||||||

| 3. BFNE | .60** | .58** | ||||||

| 4. ASI-S | .57** | .61** | .55** | |||||

| 5. DDQ-quantity | .04 | −.01 | −.03 | .04 | ||||

| 6. DDQ-frequency | .02 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .22** | |||

| 7. RAPI | .25** | .20** | .18** | .24** | .45** | .15** | ||

| 8. AUDIT | .16** | .12** | .13** | .16** | .54** | .16** | .58** | |

| M | 27.35 | 26.94 | 19.55 | 14.03 | 14.58 | 5.56 | 10.94 | 7.26 |

| SD | 15.32 | 18.30 | 8.28 | 5.35 | 16.90 | 2.09 | 13.17 | 5.36 |

Note. SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; SPS = Social Phobia Scale; BFNE = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation; ASI-S = Anxiety Sensitivity Index – Social; DDQ = Daily Drinking Questionnaire; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

p < .01

Class enumeration

Across the eight different class solutions, the six-class solution appeared to be the best fitting model with the current sample (see Table 2). Given that the BIC value decreased across the eight class solutions, we chose the six-class solution based on the LMRT. Specifically, the LMRT was significant for the six-class solution and non-significant for the seven-class solution, indicating the six-class solution fit significantly better than the five-class solution and the seven-class solution did not fit significantly better than the six-class solution. Finally, the entropy value was 0.91, indicating adequate classification accuracy.

Table 2.

Latent profile analysis for class solutions 1 through 8

| Classes (k) | LMRT | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38519.05 | ||

| 2 | 932.50** | 37629.26 | .807 |

| 3 | 561.19** | 37117.11 | .876 |

| 4 | 400.80** | 36768.09 | .911 |

| 5 | 319.99** | 36501.26 | .918 |

| 6 | 248.02* | 36307.63 | .912 |

| 7 | 200.22 | 36162.61 | .899 |

| 8 | 184.81 | 36033.27 | .898 |

Note. LMRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion

p < .001

p < .01

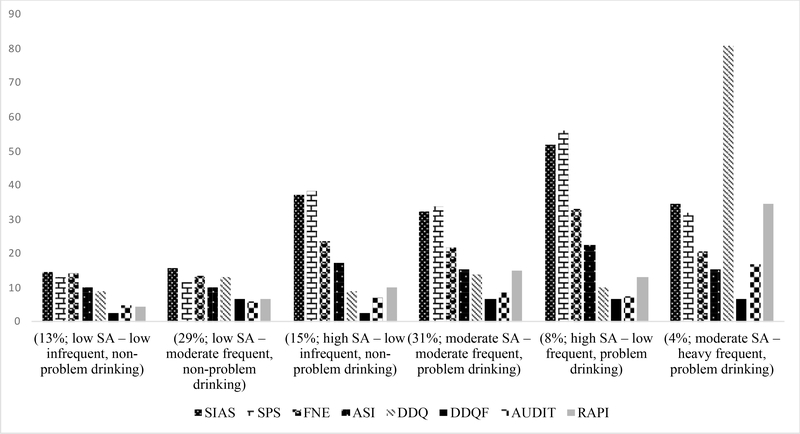

The estimated pattern of means on social anxiety characteristics and alcohol use behaviors across the six latent classes is provided in Table 3. Mean values across social anxiety and alcohol use measures are depicted in Figure 1. Broadly, classes differed based on severity of social anxiety characteristics and distinct alcohol use behaviors. Participants in class 1 (n = 89.10; 13.22%) were characterized by low levels of social anxiety, low drinking quantity and frequency, and non-problem drinking behaviors. Participants in class 2 (n = 196.69; 29.18%) were characterized by low levels of social anxiety, moderate drinking quantity, high drinking frequency, and non-problem drinking behaviors. Class 3 (n = 100.33; 14.89%) was characterized by moderate levels of social anxiety, low drinking quantity and frequency, and non-problematic drinking behaviors. Participants in Class 4 (n = 209.40; 31.07%) were characterized by moderate levels of social anxiety, moderate drinking quantity, high drinking frequency, and problematic drinking behaviors. Participants in class 5 (n = 52.86; 7.84%) were characterized by high levels of social anxiety, low drinking quantity, high drinking frequency, and problematic drinking behaviors. Finally, class 6 (n = 25.62; 3.80%) was characterized by moderate levels of social anxiety, heavy drinking quantity (range: 54–98 drinks), high drinking frequency, and problematic drinking behaviors.

Table 3.

Mean comparisons across latent classes on social anxiety constructs and alcohol use behaviors (N = 674)

| Class 1 (13%; low SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 2 (29%; low SA – moderate frequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 3 (15%; moderate SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 4 (31%; moderate SA – moderate frequent, problem drinking) | Class 5 (8%; high SA – low frequent, problem drinking) | Class 6 (4%; moderate SA – heavy frequent, problem drinking) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw scores | ||||||

| SIAS | 14.46a | 15.53a | 37.30b | 32.08c | 51.91d | 34.41b,c |

| SPS | 13.05a | 11.65a | 38.25b | 33.65c | 56.13d | 31.89b,c |

| BFNE | 14.36a | 13.54a | 23.53b | 21.81c | 33.14d | 20.77c |

| ASI-S | 10.20a | 10.15a | 17.16b | 15.49c | 22.48d | 15.52c |

| DDQ-Q | 9.05a | 13.23b,c | 8.97a | 13.96b | 10.03a,c | 80.69d |

| DDQ-F | 2.41a | 6.81b | 2.42a | 6.78b | 6.81b | 6.61b |

| AUDIT | 4.82a | 5.97a,b | 6.95c | 8.43d | 7.47b,c,d | 16.92e |

| RAPI | 4.39a | 6.59b | 9.95c | 14.89d | 13.05c,d | 34.65e |

| Standardized scores (z-scores) | ||||||

| SIAS | −.91a | −.87a | .71b | .37c | 1.72d | .50b,c |

| SPS | −.82a | −.96a | .67b | .46c | 1.69d | .31b,c |

| BFNE | −.71a | −.81a | .55b | .32c | 1.75d | .17c |

| ASI-S | −.77a | −.85a | .64b | .36c | 1.70d | .30c |

| DDQ-Q | −.33a | −.12b,c | −.33a | −.06b | −.29a,c | 3.87c |

| DDQ-F | −1.51a | .60b | −1.52a | .59b | .60b | .50b |

| AUDIT | −.48a | −.30a,b | −.04c | .27d | .03b,c,d | 1.82e |

| RAPI | −.53a | −.40b | −.04c | .36d | .14c,d | 1.82e |

Note. Means in a row that share a subscript indicate mean scores are not significantly different from each other. SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; SPS = Social Phobia Scale; BFNE = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation; ASI-S = Anxiety Sensitivity Index – Social; DDQ-Q = Daily Drinking Questionnaire-Quantity; DDQ-F = Daily Drinking Questionnaire-Frequency; SA = social anxiety

Figure 1.

Six latent classes depicted by pattern of means scores on social anxiety constructs and alcohol use behaviors.

Predictors of class membership

Table 4 reflects the effects of age and gender on class membership with Class 6 as the reference group. No differences in age emerged across the classes. However, women were more likely to be in class 1 (77%; 23% men), 2 (79%; 21% men), 3 (83%; 17% men), and 5 (57%; 43% men) when compared to class 6 (25%). No gender differences emerged between class 4 (42% women; 58% men) and 6 (25% women; 75% men).

Table 4.

Predictors of class membership with Class 6 (moderate SA – heavy frequent, problem drinking) as the Reference Class

| Class 1 (13%; low SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 2 (29%; low SA – moderate frequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 3 (15%; moderate SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 4 (31%; moderate SA – moderate frequent, problem drinking) | Class 5 (8%; high SA – low frequent, problem drinking) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | B (SE) | OR | 95% CI | B (SE) | OR | 95% CI | B (SE) | OR | 95% CI | B (SE) | OR | 95% CI | B (SE) | |

| Age | 1.16 | .84,1.59 | .14(.16) | 1.07 | .78,1.46 | .07(.16) | .92 | .62,1.36 | −.09(.20) | 1.22 | .87,1.71 | .20(.17) | .93 | .65,1.32 | −.07(.18) |

| Female | 10.60 | 3.60,31.18 | 2.36(.55)* | 11.65 | 3.93,34.53 | 2.46(.55)* | 15.03 | 3.66,61.77 | 2.71(.72)* | 2.46 | .78,7.76 | .90(.59) | 3.89 | 1.25,12.13 | 1.36(.58) |

Note. SA = Social anxiety; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

significantly different from the reference class (class 6)

Equality of means

Table 5 shows the mean differences in auxiliary variables across the classes. Significant differences in beliefs of others’ impression of them while drinking, academic performance, and emotional distress emerged across classes. Participants in class 1 had significantly fewer beliefs surrounding interaction, observation, and tension-reduction fears than participants in all other classes, and participants in class 1 and 2 had fewer evaluation fears-related beliefs than participants in other classes. Participants in class 6 had significantly more beliefs surrounding evaluation fears than participants in all other classes, as well as more interaction, observation, and tension reduction fears that participants in all other classes except class 5. Participants in class 5 had the highest GPA, and this class was significantly higher than participants in class 6. Participants in class 1 and 2 endorsed lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress than all other classes. Participants in class 5 and 6 had significantly higher depression, anxiety, and stress than all other classes.

Table 5.

Mean comparisons across latent classes on auxiliary outcomes

| Class 1 (13%; low SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 2 (29%; low SA – moderate frequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 3 (15%; moderate SA – low infrequent, non-problem drinking) | Class 4 (31%; moderate SA – moderate frequent, problem drinking) | Class 5 (8%; high SA – low frequent, problem drinking) | Class 6 (4%; moderate SA – heavy frequent, problem drinking) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

| SIDS-IF | 7.92a | .34 | 8.87b | .30 | 12.85c | .49 | 12.49c,d | .36 | 14.68c,e | .92 | 15.56e | .87 |

| SIDS-OF | 6.89a | .31 | 7.76b | .25 | 11.03c | .40 | 10.90c | .33 | 12.60d | .72 | 13.04d | .66 |

| SIDS-EF | 10.58a | .48 | 11.26a | .36 | 16.21b | .65 | 16.24b | .49 | 17.23b | 1.07 | 22.26c | 1.16 |

| SIDS-TR | 8.23a | .40 | 9.43b | .29 | 12.85c | .38 | 12.41c,d | .31 | 13.97c,d,e | .74 | 14.04e | .48 |

| GPA | 3.04a,b,c | .07 | 3.12a,b,c | .05 | 3.07a,b,c | .07 | 3.07a,b,c | .05 | 3.22b | .08 | 2.90c | .12 |

| Depression | 1.97a | .37 | 1.83a | .28 | 5.66b | .48 | 4.98b | .32 | 8.08c | .87 | 8.04c | 1.09 |

| Anxiety | 1.45a | .29 | 1.75a | .23 | 5.27b | .43 | 4.63b | .32 | 7.69c | .82 | 8.20c | .88 |

| Stress | 2.68a | .38 | 2.99a | .30 | 6.63b | .42 | 6.38b | .33 | 8.94c | .76 | 8.84c | .90 |

Note. Means in a row that share a subscript indicate mean scores are not significantly different from each other.

SE = Standard errors; SIDS = Social Impression while Drinking Scale; IF = interaction fears; OF = observation fears; EF = evaluation fears; TR = tension reduction; GPA = grade point average; SA = social anxiety

Discussion

Existing literature seeking to understand the high comorbidity between social anxiety and alcohol use among college students have primarily focused on students with high versus low levels of social anxiety, assuming that such groups are homogeneous. Social anxiety can have a diverse symptom presentation, commonly diagnosed based on type and severity of feared social situations, and represented by several dimensions. The present study used a latent profile analysis to identify distinct classes of students based on social anxiety characteristics and alcohol use behaviors. In support of our hypotheses, we identified six latent classes that varied based on severity of social anxiety symptoms, quantity/frequency of alcohol use, and extent of problematic drinking behaviors. Two classes comprised participants with low levels of social anxiety and non-problematic drinking behaviors that varied based on the frequency and quantity of drinking. Three classes comprised students with moderate levels of social anxiety that varied based on quantity and frequency of weekly drinking and the extent of problematic drinking patterns. The final class comprised students with high levels of social anxiety and frequent, problematic drinking behaviors despite drinking at low quantities. Collectively, it appears that a person-centered approach provides clarity on the role of alcohol use in the association between social anxiety and risky drinking behaviors among students.

The current findings are consistent with Brook and Willoughby (2016) such that distinct classes emerged based on social anxiety symptoms and alcohol use behaviors. However, the distinction between classes based on only social anxiety severity, as opposed to social anxiety dimensions, was somewhat surprising given that four distinct measures of social anxiety were included in the present study. One potential explanation is that the current sample endorsed higher levels of social anxiety, on average, than what is commonly seen in the epidemiological literature (Izgic et al., 2004). There may be less distinction across the social anxiety dimensions as students’ social anxiety becomes more severe. Further, prior person-centered research on social anxiety found distinct classes of individuals based on type and number of feared social situations (Peyre et al., 2016), two aspects of how social anxiety develops that were not assessed in the current study.

Another potential explanation is that students’ beliefs, rather than actual experience of social anxiety symptoms may contribute to the co-development of these disorders. Current findings revealed that class membership differed by student beliefs about how others perceive them while drinking, such that those with moderate or high levels of social anxiety and more problematic drinking patterns were more likely to hold interaction, observation, and evaluation fears-related beliefs while drinking in public. Thus, students may experience varying levels of social anxiety symptoms collectively, but their risk for co-morbid alcohol use problems may be associated with specific behavioral and cognitive impression management strategies (Buckner & Matthews, 2012).

The two classes comprising students with either moderate levels of social anxiety and heavy, problematic drinking behaviors (class 4) or high levels of social anxiety and light, problematic drinking behaviors (class 6) appeared to have riskier profiles given their endorsement of higher levels of emotional distress. Although one of these classes represented only 4% of the sample (class 6), there are several potential explanations for the class differences. First, students with social anxiety likely differ in their anxiety-management methods. The two other classes (3 and 4) with moderate levels of social anxiety endorsed lower quantities of alcohol use, as compared to the quantities for the highest-risk class, suggesting that a subgroup of students with social anxiety actively avoid social situations where alcohol is unavailable (Buckner & Heimberg, 2010) or avoid drinking in social situations to avoid negative social evaluation (Book & Randall, 2002). Relatedly, students with social anxiety may vary based on their responsiveness to risky behaviors. Kashdan and Hofmann (2008) found two subgroups of students with moderate-to-high levels of social anxiety that demonstrated approach- versus avoidant-oriented behaviors, and Lipton, Weeks, Daruwala, and De Los Reyes (2016) identified two subgroups of students with high social anxiety that demonstrated high versus low levels of impulsivity. Thus, some students may internalize their symptoms whereas others engage in externalizing behaviors. Importantly, those students deemed ‘less risky’ due to their lack of associated problematic drinking still endorsed high levels of emotional distress, highlighting that alternative, maladaptive coping mechanisms geared toward reducing social anxiety (e.g., avoid social interactions) may still be problematic.

Gender differences across classes also demonstrate an important distinction when considering those with elevated risk. Students in the two riskier classes (4 and 6) had a higher representation of men as compared to the other classes. One potential explanation for this finding is that men tend to engage in riskier alcohol use as compared to women, particularly in adherence to masculine gender norms (Whitley, Madson, & Zeigler-Hill, 2018). Additionally, men may be more inclined to consume alcohol and other drugs to alleviate their social anxiety symptoms as compared to women (Xu et al., 2012). Finally, although some studies with non-college adults find that women are more likely to drink to cope with internal distress such as social anxiety (e.g., Karpyak et al., 2016), our findings that women were more representative of the less risky classes are consistent with a meta-analysis of college students that found a significant inverse relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use among women (Schry & White, 2013). To further clarify which students with social anxiety may represent riskier drinking patterns, future work should investigate other personality (e.g., impulsivity) and demographic (e.g., race/ethnicity or academic status) as predictors of class membership.

There are several clinical implications. Prevention efforts that are designed to promote healthy methods to manage anxiety and increase social engagement without alcohol may minimize the risk for students with social anxiety to engage in problematic drinking patterns. Brief motivational interventions (BMIs) have resulted in poorer treatment outcomes for students with social anxiety (Terlecki, Buckner, Larimer, & Copeland, 2011). Assessing alcohol use and social anxiety symptoms, particularly in social situations can be beneficial given that treatment goals may vary based on the quantity/frequency of alcohol use or the reliance on other anxiety management methods. These students may also benefit from mindfulness/relaxation interventions designed to teach clients how to stay present.

Findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, the positive affect or social avoidance dimensions of social anxiety (Buckner et al., 2013) were not assessed. With a primary concern that the survey length may generate undue burden on the participants, these two dimensions of social anxiety were not assessed for two reasons: the parent study was largely focused on examining the psychosocial factors theorized to underlie the social anxiety-alcohol use relationship and, as a result, the authors chose the most frequently used measures to assess social anxiety in college students. Further, prior person-centered analyses of social anxiety found support for distinct classes based on type of feared situations (Peyre et al., 2016). Future research may better distinguish these classes by including all five dimensions and a list of commonly feared social situations. Second, eligible students had to endorse past-month alcohol use, likely excluding a subgroup of students with social anxiety. The current sample endorsed higher levels of social anxiety than what is typically seen in epidemiological data (Izgic et al., 2004), and, while consistent with prior work at this institution (e.g., Villarosa et al., 2014), warrants replication of current findings at other universities throughout the US. Finally, the study was correlational in nature and data comprised primarily White, non-Hispanic females. Replication of the current study using a multi-site, longitudinal design with a more diverse sample is needed.

The current findings support the claim that comorbid social anxiety and alcohol use symptoms place students at greater risk for adverse outcomes (Schneier et al., 2010). Expanding on prior work, findings revealed that students with subclinical social anxiety and more problematic drinking behaviors were more likely to hold interaction, observation, and evaluation fear-related beliefs while drinking and endorsed more academic and emotional impairment. Examining subgroups of students with social anxiety, regardless of drinking status, and identifying the composition of coping methods they may use to manage their anxiety may inform how best to mitigate adverse outcomes.

Highlights.

College students with social anxiety are vulnerable to alcohol use problems.

Latent profile analysis found six classes of social anxiety and drinking behaviors.

Subclinical social anxiety and drinking problems represented the riskiest profile.

Comorbid social anxiety and alcohol use symptoms increase risk of adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgement

MCH is supported by a training grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32AA018108. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG,…Bruffaerts R (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46, 2955–2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, & Vermunt JK (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling, 23, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Book SW, & Randall CL (2002). Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use. Alcohol Research and Health, 26, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Brook CA, & Willoughby T (2016). Social anxiety and alcohol use across the university years: Adaptive and maladaptive groups. Developmental Psychology, 52, 835–845. 10.1037/dev0000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, & Barlow DH (1997). Validation of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Timpano KR, Zvolensky MJ, Sachs-Ericsson N, & Schmidt NB (2008). Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 1028–1037. 10.1002/da.20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, & Heimberg RG (2010). Drinking behaviors in social situations account for alcohol-related problems among socially anxious individuals. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 640–648. 10.1037/a0020968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Heimberg RG, Ecker AH, Vinci C, 2013. A biopsychosocial model of social anxiety and substance use. Depress and Anxiety, 30, 276–284. 10.1002/da.22032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, & Matthews RA (2012). Social impressions while drinking account for the relationship between alcohol-related problems and social anxiety. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 533–536. 10.1016/i.addbeh.2011.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Collimore KC, McCabe RE, & Antony MM (2011). Addressing revisions to the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale: Measuring fear of negative evaluation across anxiety and mood disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan MH, & Randall CL (2003). Self-medication in social phobia: A review of the alcohol literature. Addictive Behaviors, 28, 269–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA, 1985. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross WC (1993). Gender and age differences in college students’ alcohol consumption. Psychological Reports, 72, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Bacon AK, Carrigan MH, Zamboanga BL, & Casner HG (2016). Social anxiety and alcohol use: The role of alcohol expectancies about social outcomes. Addiction Research and Theory, 24, 9–16. 10.3109/16066359.2015.1036242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Mueller GP, Holt CS, Hope DA, & Liebowitz MR (1992). Assessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Behavior Therapy, 23, 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Izgic F, Akyuz G, Dogan O, & Kugu N (2004). Social phobia among university students and its relation to self-esteem and body image. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, & Wickrama KAS (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Karpyak VM, Biernacka JM, Geske JR, Abulseoud OA, Brunner MD, Chauhan M, & Onsrud DA (2016). Gender specific effects of comorbid depression and anxiety on the propensity to drink in negative emotional states. Addiction, 111, 1366–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Hofmann SG (2008). The high-novelty-seeking, impulsive subtype of generalized social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & McKnight PE (2010). The darker side of social anxiety: When aggressive impulsivity prevails over shy inhibition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Steger MF (2006). Expanding the topography of social anxiety. Psychological Science, 17, 120–128. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR (1983). A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Hove MC, Kirkeby BS, Oster-Aaland L, Whiteside U, Lee CM,…Larimer ME (2008). Fitting in and feeling fine: Conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22, 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton MF, Weeks JW, Daruwala SE, & De Los Reyes A (2016). Profiles of social anxiety and impulsivity among college students: A close examination of profile differences in externalizing behavior. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38, 465–475. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, & Lovibond SH (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, & Clarke C (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fears and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 455–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra R, & McKean M (2000). College students’ academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management, and leisure satisfaction. American Journal of Health Studies, 16, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (2017). M-plus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthen BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Armeli S, & Tennen H (2015). College students’ drinking motives and social- contextual factors: Comparing associations across levels of analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 420–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Guiterrez PM, & Lozano G (2012). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales—21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 13221338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyre H, Hoertel N, Rivollier F, Landman B, McMahon K, Chevance A,…Limosin F (2016). Latent class analysis of the feared situations of social anxiety disorder: A population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, & Allen JP (2002). The Alcohol Use Identification Disorder Test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 26, 272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, & McNally RJ (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Woods CM, Thissen DM, Heimberg RG, Chambless DL, & Rapee RM (2004). More information from fewer questions: The factor structure and item properties of the original and brief fear of negative evaluation scale. Psychological Assessment, 16, 169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction, 88, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Foose T, Hasin DS, Heimberg RG, Liu SM, Grant BF, & Blanco C (2010). Social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine, 40, 977–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schry AR, & White SW (2013). Understanding the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use in college students: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 38, 2690–2706. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecki MA, Buckner JD, Larimer ME, & Copeland AL (2011). The role of social anxiety in a brief alcohol intervention for heavy-drinking college students. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25, 7–21. 10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpq025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa MC, Madson MB, Zeigler-Hill V, Noble JJ, & Mohn RS (2014). Social anxiety symptoms and drinking behaviors among college students: The mediating effects of drinking motives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 710–718. 10.1037/a0036501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Madson MB, Zeigler-Hill V, Mohn RS, & Nicholson BC (2018). Social anxiety and alcohol-related outcomes: The mediating role of drinking context and protective strategies. Addiction Research and Theory, 26, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Whitley RB, Capron DW, & Madson MB (2018). Thinking while drinking: Fear of negative evaluation predicts drinking behaviors of students with social anxiety. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 160–165. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, 1989. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RB, Madson MB, & Zeigler-Hill V (2018). Protective behavioral strategies and hazardous alcohol use among male college students: Conformity to male gender norms as a moderator. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 19, 477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Schneier F, Heimberg RG, Princisvalle K, Liebowitz MR, Wang S, & Blanco C (2012). Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic sample on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]