Abstract

Phthalates are endocrine disrupting compounds commonly found in consumer products, exposure to which may influence reproductive maturation. Effects from exposure in utero on the onset and progression of sexual development are understudied. We examined longitudinal associations between gestational phthalate exposure and sexual maturation at two points in adolescence (8–14, 9–18 years). Gestational exposure was quantified using the geometric mean of 3 trimester-specific urinary phthalate metabolite measurements. Sexual maturation was assessed using Tanner stages and menarche onset for girls and Tanner stages and testicular volume for boys. Generalized estimating equations for correlated ordinal multinomial responses were used to model relationships between phthalates and odds of transitioning to the next Tanner stage, while generalized additive (GA) mixed models were used to assess the odds of menarche. All models were adjusted for child age (centered around the mean), BMI z-score, change in BMI between visits, time (years) between visits (ΔT), and interactions between ΔT and mean-centered child age and the natural log of exposure metabolite concentration. Among girls, a doubling of gestational MBzP concentrations was associated with increased odds of being at a higher Tanner stage for breast development at 8–14 years (OR=4.62; 95% CI: 1.38, 15.5), but with slower progression of breast development over the follow-up period (OR=0.65 per year; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.92) after adjustment for child age and BMI z-score. Similar results were found for ΣDEHP levels and breast development. In boys, a doubling of gestational MBP concentrations was associated with lower odds of being at a higher Tanner stage for pubic hair growth at 8–14 years (OR=0.37; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.95) but with faster progression (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 0.97, 1.69). These results indicate that gestational phthalate exposures may impact the onset and progression of sexual development, and that these relationships differ between boys and girls.

Keywords: Phthalates, maternal-child health, puberty, pregnancy exposures, biomarkers, breast development

1. Introduction

Decreasing age at pubertal onset has become an increasingly common global problem in the last decade (Aksglaede et al., 2008; Biro and Greenspan, 2013; Herman-Giddens et al., 2012). Several different mechanisms have been proposed as influencing this trend including genetic factors (Elks et al., 2010; Ong et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2014), increasing trends in BMI (Aksglaede et al., 2009; Boyne et al., 2010; Buyken et al., 2008; Kleber et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010, 2007; Sørensen et al., 2010), and endocrine disruption (Buck Louis et al., 2008), but true underlying factors are still poorly understood.

Phthalates are a class of endocrine disrupting compounds commonly used in the manufacture of consumer products including food storage containers, medical tubing, and personal care products. Exposure to phthalates is widespread in the population (A. M. Calafat et al., 2015) and has been linked to numerous adverse health outcomes including altered reproductive function throughout the life cycle (Hauser and Calafat, 2005). Exposure among pregnant women specifically has been investigated (Arbuckle et al., 2014; Cantonwine et al., 2014; Valvi et al., 2015; Zeman et al., 2013) and found to be linked to adverse birth outcomes including low birth weight, birth length, head circumference, gestational age, and risk of spontaneous abortion and preterm birth (Casas et al., 2016; Dereumeaux et al., 2016; Ferguson et al., 2014a, 2016; Ko et al., 2013; Meeker et al., 2009; Mu et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2016; Smarr et al., 2015; Toft et al., 2012; Watkins et al., 2016).

Previous research has demonstrated significant associations between sexual maturation outcomes and phthalate exposures measured during childhood (Binder et al., 2018; Kasper-Sonnenberg et al., 2017; A. Mouritsen et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015) and adolescence (Frederiksen et al., 2012; Srilanchakon et al., 2017; Wolff et al., 2010). Animal studies have demonstrated that in utero phthalate exposure may lead to a myriad of adverse reproductive outcomes, particularly inhibition of testosterone synthesis in the testes among males and reduced fertility among females (X. Chen et al., 2017; Howdeshell et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2013; Kay et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2017), but human studies are still lacking. Furthermore, studies that do utilize gestational phthalate exposure do not use multiple adolescent follow-up visits to assess influence on the rate of progression of sexual development. Previous research coming from the ELEMENT cohort utilized gestational phthalate concentrations to assess relationships with odds of onset of sexual maturation at 8–14 years, but we now have additional data at a second adolescent follow-up visit (ages 9–18 years) that was not available previously (Watkins et al., 2017a, 2017b). Therefore, the goal of this analysis was to build on previous ELEMENT work by utilizing multiple gestational measures of urinary phthalate biomarkers to test for associations with initiation and progression of sexual maturation at two different adolescent follow-up visits.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

The present study was conducted as part of the Early Life Exposure in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants (ELEMENT) project, a longitudinal pregnancy cohort in Mexico City. Women were recruited from 1997 to 2004 during their first trimester from maternity hospitals (Lewis et al., 2013). Urine samples were collected and interview-based questionnaires were completed by mothers at up to three time points during pregnancy. Mean gestational ages, which were estimated based on the self-reported date of last menstrual period, were 13.5 weeks (range 9–24 weeks), 25.1 weeks (range 19–37 weeks) and 34.4 weeks (range 28–43 weeks) at each visit. A subset of adolescent children from these mothers were followed-up over two adolescent study visits, one beginning in 2011 and one in 2015, where they provided anthropometry and demographic information. Ages of children ranged from 8 to 14 years at the first adolescent visit and 9 to 18 years at the second visit (there was not a fixed number of years between study visits). The World Health Organization child reference curves for age and sex were used to calculate age-specific BMI z-scores (World Health Organization, 2007). The present analysis included children with data at both adolescent follow-up visits for at least one pubertal outcome, and whose mothers provided at least one urinary phthalate measurement during pregnancy, resulting in a final sample size of 103 girls and 91 boys. Among those 103 girls, a total of 2, 16, and 85 mothers provided urine samples at 1, 2, and 3 gestational visits, respectively. Among those 91 boys, a total of 9, 10, and 72 mothers provided urine samples at 1, 2, and 3 gestational visits, respectively. Supplementary Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of mothers included in the present analysis compared to all ELEMENT mothers who had children eligible for inclusion this study (N=554). Research protocols were approved by the ethics and research committees of the Mexico National Institute of Public Health and the University of Michigan, and all participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment.

2.2. Urinary phthalate measurements

Spot urine samples were collected from participants. Samples were frozen, kept at −80°C, and transported to the University of Michigan for analysis at NSF International (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Nine phthalate metabolites were measured including monoethyl phthalate (MEP), mono-n-butyl phthalate (MnBP), monoisobutyl phthalate (MiBP), monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP), mono-3-carboxypropyl phthalate (MCPP), mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP), mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl phthalate (MEHHP), mono-2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl phthalate (MEOHP), and mono-2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl phthalate (MECPP) using isotope dilution–liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (ID–LC–MS/MS), described elsewhere (Lewis et al., 2013). A summary measure of DEHP (ΣDEHP) exposure was calculated by dividing the concentrations of each metabolite by their molar mass and then summing the results. Specific gravity was measured at the time of sample analysis using a handheld digital refractometer (Atago Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All concentrations measured below the limit of detection (LOD) were replaced by the LOD/√2.

2.3. Sexual maturation outcome assessment

Tanner stages are measured on a standardized scale from 1 to 5 to indicate various stages of sexual maturation, with stage 1 indicating that an individual has not yet initiated development, stages 2–4 indicating progression through sexual development, and stage 5 indicating adulthood (Marshall and Tanner, 1970, 1969). In the present study, Tanner stages among all children were determined according to standard methods (Chavarro et al., 2017) by two trained physicians. Among girls, breast development was used as an indicator of puberty and pubic hair growth was used as an indicator of adrenarche. We utilized self-reported onset of menarche as an additional indicator of puberty. Among boys, genital development was used as an indicator of puberty and pubic hair growth was used as an indicator of adrenarche. We utilized testicular volume measurements as an additional indicator of puberty. Both right and left testicular volume were measured using an orchidometer and the larger of the two measurements was retained. Categories of testicular volume were set to ≤3 mL (prepubertal), >3 – 20 mL (peripubertal), and >20 mL (adulthood) (Mouritsen et al., 2013).

2.4. Statistical methods

Arithmetic means and standard deviations were calculated for age and BMI at each adolescent follow up visit. Total N and percent of the population at each stage of sexual maturation, in addition to the mean age and standard deviation at each development stage, were determined at each study visit. Phthalate biomarker measurements were natural log transformed for subsequent individual analyses. Geometric means were calculated from all available phthalate metabolite measurements from multiple trimesters to represent overall gestational exposure for each participant. Additional analyses were conducted where we stratified results by trimester of phthalate exposure but no notable differences were observed (data not shown).

Because two visits were available per participant, methods for correlated outcome data were utilized to examine the association between phthalate exposure and sexual development. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) for correlated ordinal multinomial responses with an independent correlation structure were used to model relationships between gestational phthalate exposure and odds of being at a higher Tanner stage or category of testicular volume at baseline (age 8–14 years). Generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) were used to assess the relationship between exposures and the binary menarche outcome at baseline. The use of these models allows for examination of both baseline development stages and progression between study visits, and accommodation of intraindividual correlation of exposure and outcome variables. Models included time (in years) between first and second adolescent follow up visits (ΔT), the natural log of the phthalate metabolite concentration, and interaction between ΔT and the natural log of the phthalate metabolite concentration. Coefficients from these models were used to estimate (1) the odds of being at a higher versus a lower development stage (or menarche yes vs. no) at the initial adolescent follow up visit (age 8–14 years) per doubling in gestational phthalate concentration (the main effect of the metabolite), and (2) the effects of gestational phthalate exposure on the tempo at which individuals progressed through puberty and adrenarche (the interaction term between phthalate metabolite concentration and time between study visits). The following equations were used to calculate effects estimates and confidence intervals for a doubling in phthalate exposure:

Tempo results are presented as the odds of being at a higher versus a lower development stage per year following the initial adolescent visit associated with a doubling in gestational phthalate exposure, among those with mean age at the initial adolescent visit. Tempo does not refer to the time it takes to progress from one preestablished maturation milestone to another, but rather the general amount of progression that occurs in one year. A tempo odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that higher phthalate concentrations are associated with a faster rate of development, while a tempo odds ratio less than 1 would indicate a slower rate of development.

Child age (centered around the mean) and BMI z-score at the first adolescent visit were included as covariates, in keeping with previous work published by our group (Watkins et al., 2017b) and from a priori knowledge of associations with phthalates (Harley et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017) and sexual maturation (C. Chen et al., 2017; Kaplowitz, 2008; Rosenfield et al., 2009). Final models also adjusted for change in BMI between the first and second adolescent visits, interaction between mean-centered age at first adolescent visit and ΔT, and interaction between ΔT and the natural log of the phthalate metabolite concentration. Other covariates that were explored for potential confounding effects included maternal age, education level, and socioeconomic status during pregnancy. None of these exploratory covariates were associated with both exposures and outcomes and were thus excluded from final models. All phthalate metabolites were adjusted for specific gravity before inclusion in the model to account for differences in urinary dilution. To address the issue of possible false discovery from conducting many comparisons, we calculated q values using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Each sexual maturation outcome was treated as a family of tests (10 tests for each phthalate metabolite per outcome, run separately for main effect p-values and tempo p-values). High p-values were viewed as being at a higher risk of being false-positives, and q-values<0.1 were interpreted with greater confidence.

3. Results

3.1. Phthalate concentrations through pregnancy

Detailed descriptions of prenatal phthalate exposure distributions among ELEMENT girls and boys are published elsewhere (Watkins et al., 2017b, 2017a) and are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, all metabolites except for MiBP were detected in at least 90% of samples. After adjustment for specific gravity, most median metabolite concentrations were higher among women expecting a female than a male child throughout gestation. Median concentrations of phthalate metabolites were at their highest in the third trimester among girls (except MEP and MECPP) and boys. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were the highest for MEP and the lowest for MCPP among girls and MBzP among boys.

3.2. Sexual progression of the study population

Sexual maturation descriptive statistics over the study duration are shown in Table 1. On average, both girls and boys were 10 years old at the first adolescent study visit and just under 14 years old at the second visit. Both girls and boys had, on average, slightly lower BMI at baseline than age-matched children in other populations (BMI z-scores of 0.87 and 0.88 among girls and boys, respectively).

Table 1:

Outcome descriptive statistics among boys and girls at two adolescent follow-up visits

| Girls (N=103) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | |||||

| Mean (sd) | N (%) | Mean Age (sd) | Mean (sd) | N (%) | Mean Age (sd) | |

| Age (years) | 9.98 (1.52) | 13.3 (1.63) | ||||

| ΔT (years)* | --- | 3.40 (0.400) | ||||

| BMI | 19.4 (3.59) | 21.8 (4.10) | ||||

| BMI - z Score | 0.870 (1.25) | --- | ||||

| ΔBMI | --- | 2.35 (1.93) | ||||

| Breast Development Tanner Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 74 (71.9%) | 9.31 (0.960) | 5 (4.90%) | 11.5 (0.350) | ||

| 2 | 16 (15.5%) | 10.9 (1.36) | 12 (11.8%) | 12.2 (0.850) | ||

| 3 | 11 (10.7%) | 12.6 (0.470) | 45 (44.1%) | 12.7 (1.10) | ||

| 4 | 2 (1.90%) | 13.0 (0.500) | 23 (22.5%) | 13.8 (1.61) | ||

| 5 | 0 | --- | 17 (16.7%) | 15.5 (1.11) | ||

| Pubic Hair Tanner Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 84 (81.6%) | 9.42 (1.01) | 9 (8.80%) | 11.6 (0.490) | ||

| 2 | 14 (13.5%) | 12.2 (0.730) | 38 (37.2%) | 12.6 (1.05) | ||

| 3 | 4 (3.90%) | 13.0 (0.440) | 26 (25.5%) | 13.3 (1.43) | ||

| 4 | 1 (1.00%) | 13.3 (NA) | 17 (16.7%) | 14.3 (1.60) | ||

| 5 | 0 | --- | 12 (11.8%) | 15.5 (1.16) | ||

| Menarche | ||||||

| No | 87 (84.5%) | 9.51 (1.13) | 23 (22.5%) | 12.1 (0.850) | ||

| Yes | 16 (15.5%) | 12.5 (0.610) | 79 (77.5%) | 13.6 (1.60) | ||

| Boys 1 N=91) | ||||||

| P20 | P01 | |||||

| Mean (sd) | N (%) | Mean Age (sd) | Mean (sd) | N (%) | Mean Age (sd) | |

| Age (years) | 10.2 (1.52) | 13.5 (1.70) | ||||

| ΔT (years)* | --- | 3.32 (0.440) | ||||

| BMI | 18.9 (3.08) | 20.4 (3.85) | ||||

| BMI - z Score | 0.880 (1.22) | --- | ||||

| ΔBMI | --- | 1.53 (1.71) | ||||

| Genital Development Tanner Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 49 (53.8%) | 9.41 (1.00) | 7 (7.70%) | 11.8 (0.390) | ||

| 2 | 33 (36.3%) | 10.5 (1.34) | 17 (18.7%) | 12.4 (0.820) | ||

| 3 | 8 (8.80%) | 12.9 (0.540) | 22 (24.1%) | 12.5 (1.10) | ||

| 4 | 1 (1.10%) | 13.2 (NA) | 30 (33.0%) | 14.0 (1.28) | ||

| 5 | 0 | --- | 15 (16.5%) | 15.9 (1.13) | ||

| Pubic Hair Tanner Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 79 (86.8%) | 9.80 (1.25) | 27 (29.7%) | 12.0 (0.79) | ||

| 2 | 10 (11.0%) | 12.6 (0.70) | 15 (16.5%) | 12.8 (1.01) | ||

| 3 | 2 (2.20%) | 12.6 (0.920) | 25 (27.5%) | 13.6 (1.19) | ||

| 4 | 0 | --- | 12 (13.2%) | 15.0 (1.46) | ||

| 5 | 0 | --- | 12 (13.2%) | 15.8 (1.23) | ||

| Testicular Volume | ||||||

| [0, 3] | 14 (15.4%) | 9.29 (0.930) | 0 | --- | ||

| (3,20] | 76 (83.5%) | 10.3 (1.51) | 59 (64.8%) | 12.7 (1.20) | ||

| (20, 25] | 1 (1.10%) | 13.8 (NA) | 32 (35.2%) | 15.0 (1.51) | ||

Refers to the time, in years, between visits 1 and 2.

Among girls, initiation of breast development occurred earlier than menarche and adrenarche, with 28.1% of girls having initiated breast development at the first study visit compared to only 18.4% and 15.5% of girls having initiated pubic hair growth and menarche, respectively. Similarly, a larger portion of girls had reached sexual maturity (Tanner Stage = 5) by the second study visit with respect to breast development (16.7%) compared to pubic hair growth (11.8%). The majority of girls progressed 2 stages (N=46) for breast development [median(IQR): 2(1)] and 1 stage (N=41) for pubic hair growth [median(IQR): 1(1)].

Among boys, the patterns for puberty and adrenarche were more discordant. Adrenarche occurred much later than puberty, with only 13.2% of boys having initiated pubic hair development by the first study visit, compared to 46.2% of boys having initiated genital development and 84.6% of boys having a testicular volume greater than 3 mL. In contrast, a larger portion of boys had reached stage 5 by the second study visit with respect to genital development (16.5%) compared to pubic hair growth (13.2%). Furthermore, only 70.3% of the male population had initiated pubic hair growth by the second study visit. The majority of boys progressed 2 stages (N=35) for genital development [median(IQR): 2(1)], 0 or 2 stages (N=27 and 26, respectively) for pubic hair growth [median(IQR): 2(2)], and 0 or 1 category (N=47 and 43, resepectively) for testicular volume [median(IQR): 0(1)].

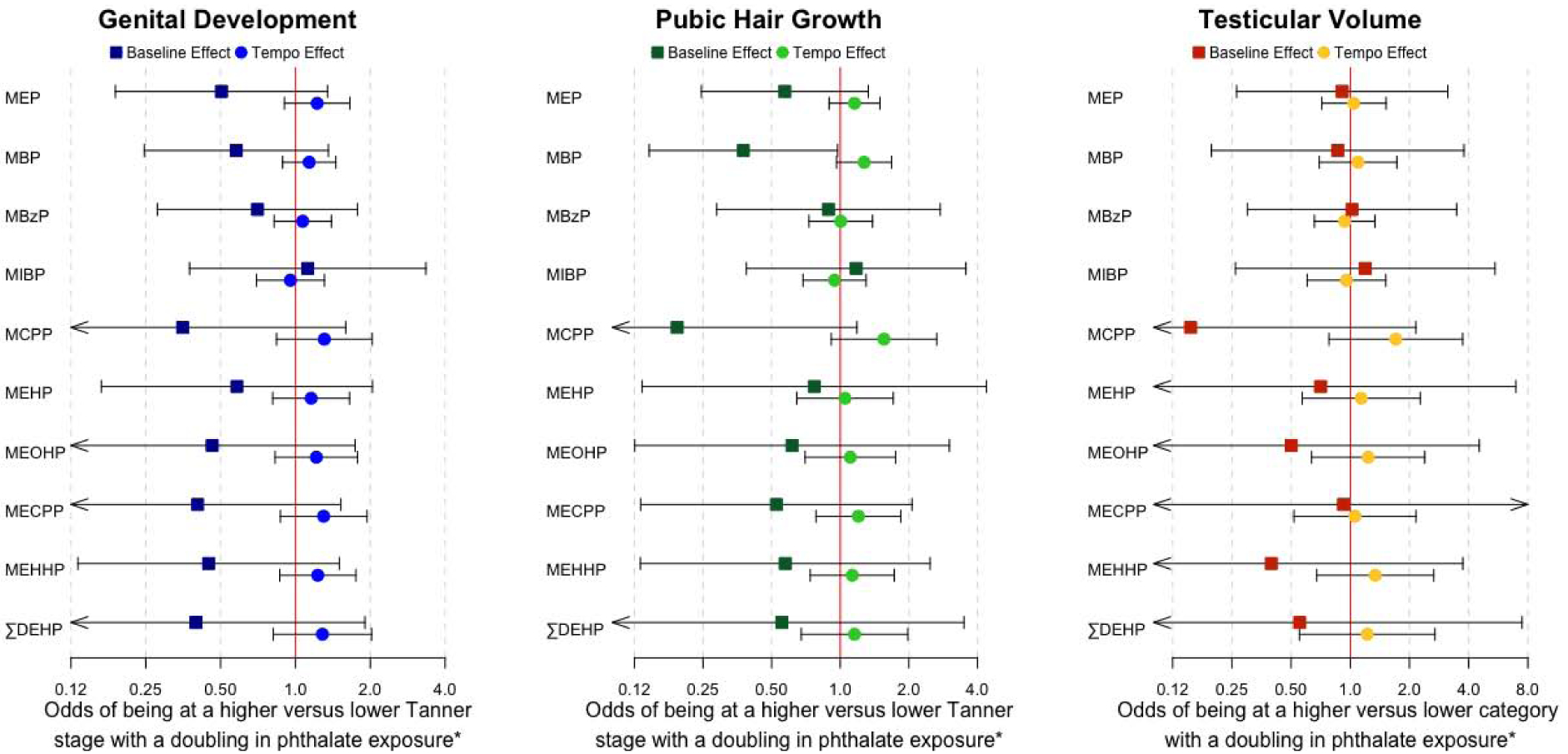

3.3. Phthalate associations with sexual maturation among girls

Associations between gestational phthalate biomarker concentrations and sexual development outcomes among girls are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3. A doubling of ΣDEHP metabolites was associated with increased odds of being at a higher breast development Tanner Stage at the initial study visit (OR: 2.76, 95%CI: 1.09, 6.96), and also with reduced tempo of breast development over the study period (OR: 0.76, 95%CI: 0.58, 1.00). Similar results were found among DEHP metabolites at the initial study visit [MECPP (OR: 2.50, 95%CI: 1.03, 6.03), MEHHP (OR: 2.76, 95%CI: 1.07, 7.14), MEOHP (OR: 2.90, 95%CI: 1.16, 7.23)], and with MBzP (OR: 4.62, 95%CI: 1.38, 15.5). The tempo of breast development over the study period was reduced per each doubling of MBzP, MEOHP, MEHHP and ΣDEHP (OR range: 0.62 – 0.76), though not all of these results reached statistical significance.

Figure 1: Among girls, the odds of being at a higher tanner stage or menarche at the first adolescent study visit and the tempo of sexual maturation progression, with a doubling in gestational phthalate exposure (N=103).

* Baseline estimates correspond to effects at the first follow-up visit at 8–14 years of age. Tempo estimates correspond to effects per year following the initial study visit.

Odds of being at a higher versus a lower Tanner Stage for pubic hair growth at baseline were marginally higher with a doubling of gestational MEP concentration (OR: 2.24, 95%CI: 0.97, 5.14). Odds of having reached menarche by the first study visit were marginally higher (OR: 3.86, 95%CI: 0.96, 15.5), and the tempo of progression to menarche was slower (OR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.47, 1.02), with a doubling of gestational MBzP concentration.

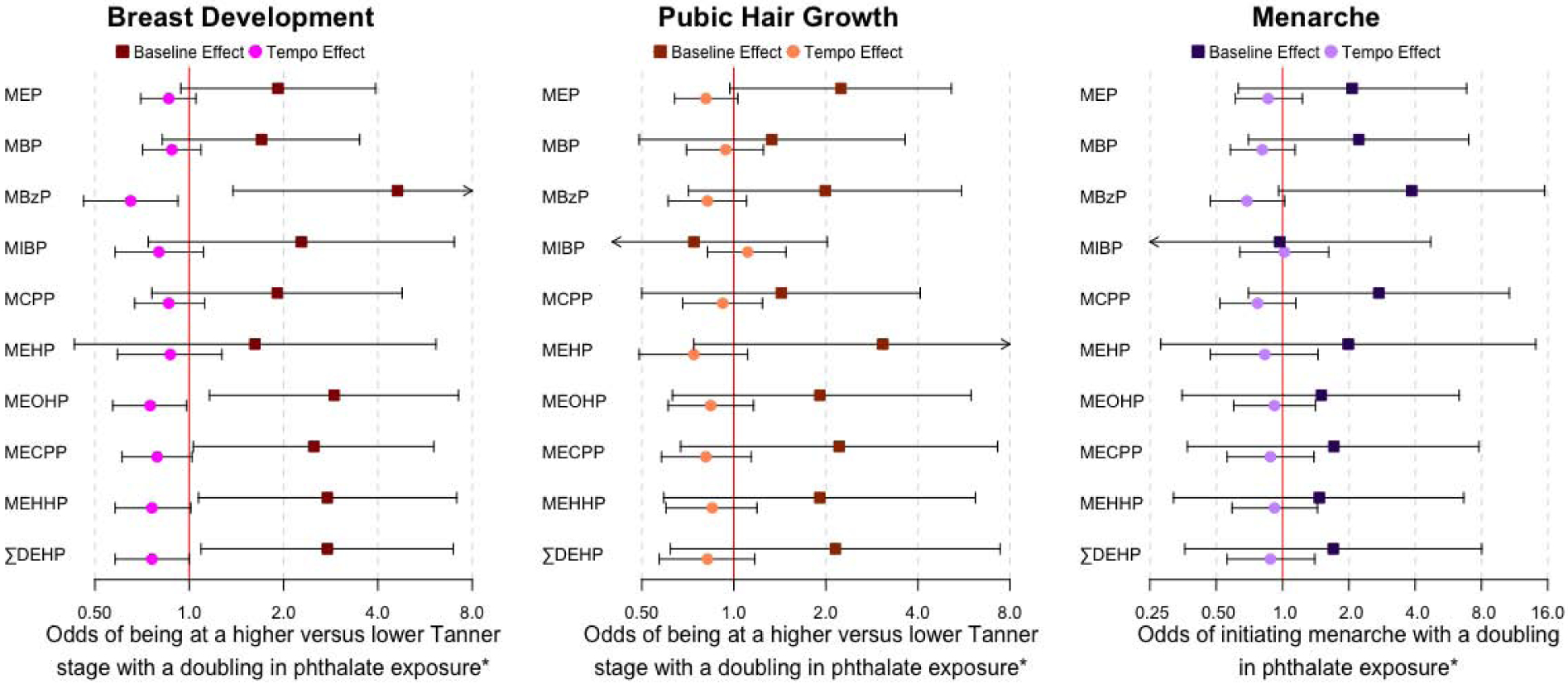

3.4. Phthalate associations with sexual maturation among boys

Associations between gestational phthalate biomarker concentrations and sexual development outcomes among boys are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4. A doubling of gestational MBP concentration was associated with decreased odds of being at a higher Tanner Stage for pubic hair growth among boys at the first study visit (OR: 0.38, 95%CI: 0.15, 0.97), and with a marginally increased tempo of progression of pubic hair growth (OR: 1.27, 95%CI: 0.96, 1.68). Measures of gestational phthalate exposure were generally associated with decreased odds of being at a higher Tanner Stage for genital development at the first study visit and increased tempo of progression (except MIBP) through genital development over the study period, but none of these relationships were statistically significant. There were no clear patterns of association between gestational phthalate levels and testicular volume.

Figure 2: Among boys, the odds of being at a higher tanner stage or testicular volume category at the first adolescent study visit and the tempo of sexual maturation progression, with a doubling in gestational phthalate exposure (N=91).

* Baseline estimates correspond to effects at the first follow-up visit at 8–14 years of age. Tempo estimates correspond to effects per year following the initial study visit.

4. Discussion

We assessed relationships between geometric mean gestational phthalate metabolite concentrations, and onset and progression of sexual maturation outcomes among girls and boys over two adolescent follow-up visits. Our findings suggest that higher gestational exposure to phthalates among females was associated with earlier onset and slower progression of sexual development, while the opposite patterns were seen among males (i.e., later onset and faster progression). The most marked results were seen with high molecular weight phthalate metabolites (MBzP and DEHP metabolites) and breast development in girls, and low molecular weight phthalate metabolites (MBP) and pubic hair growth in boys.

This is one of the first studies to assess relationships between gestational phthalate exposure and the tempo of sexual maturation progression. Several previous studies have explored associations between onset of puberty and the rate of progression to sexual maturity, and most found that those with early onset of puberty progressed to adulthood significantly slower than those with late onset of puberty (German et al., 2018; Pantsiotou et al., 2008; Vizmanos et al., 2004). This apparent compensatory mechanism may function to ensure that age at sexual maturity remains within a normal range. In the present study, we found that onset and tempo of sexual maturation outcomes generally showed opposite relationships with increasing phthalate exposures, with onset being earlier and tempo being slower among girls, and onset being later and tempo being faster among boys. These associations suggest that the biological response to increasing phthalate exposures may exacerbate basal trends that are seen among individuals with early and late onset of puberty, or that innate physiology works to maintain homeostatic conditions by compensating for the effects of phthalate exposures.

Gestational urinary biomarkers of phthalate exposure have previously been assessed for relationships with sexual development later in life in numerous studies coming from two cohorts – ELEMENT and CHAMACOS. Early ELEMENT studies assessed relationships between third trimester phthalate measurements and sexual development at a single follow-up visit at age 8–14 years among girls (Watkins et al., 2014) and boys (Ferguson et al., 2014b), and found that odds of pubic hair growth were generally increased among girls and reduced among boys with greater gestational phthalate exposures. Subsequent ELEMENT studies examined measures of phthalate exposure across gestation in relation to odds of onset of sexual development in girls (Watkins et al., 2017b) and boys (Watkins et al., 2017a). Their results suggested that higher gestational exposure to MEP was associated with greater odds of initiation of menarche, higher gestational exposure to MEHP was associated with decreased odds of initiation of breast development, and higher gestational exposure to MBzP was inversely associated with odds of initiating pubic hair growth in boys. Except for MEHP and breast development, the direction of associations found in our study were consistent to those found previously, though not statistically significant. The majority of our study population had initiated sexual development by the second follow-up visit and thus the stages of development were more evenly distributed across participants compared to the first visit. This allowed us to utilize a statistical model which takes advantage of the ordinal nature of Tanner Stage outcomes in the present work, while former studies were only able to assess odds of initiating development (Tanner Stage > 1) versus not (Tanner Stage = 1).

Multiple studies looking at gestational phthalate exposure relationships with sexual maturation outcomes have come from the CHAMACOS birth cohort in southern California (N = 179 girls and 159 boys). Urine samples were taken at two time points during pregnancy (mean 14 and 26.9 weeks) to measure metabolite concentrations of high (Berger et al., 2018) and low molecular weight (Harley et al., 2019) phthalates, and the geometric mean of these concentrations was used as an overall measure of gestational phthalate exposure. Children were followed to assess sexual development outcomes every 9 months between the ages of 9 and 13 years, and results were presented as the adjusted mean shift in age at onset of each sexual maturation outcome. Some results in the current study were consistent with those seen in the CHAMACOS cohort, including associations between gestational MEP exposure and earlier onset of pubic hair growth in girls, and between gestational MBzP and ΣDEHP metabolites and earlier onset of breast development in girls. However, various additional associations were found in the CHAMACOS studies that were not observed in our study. Sexual development stages were generally reached at a later age among ELEMENT girls compared to CHAMACOS girls, and distributions of some phthalate metabolite concentrations were different between ELEMENT and CHAMACOS, including those of several DEHP metabolites (median concentrations of MEHP, MEHHP, and MECPP were higher in ELEMENT), which may have contributed to differences in results. Additionally, the participants in the CHAMACOS cohort reside in a community where pesticide exposure is high (Castorina et al., 2003), reducing the generalizability of the results. Lastly, the CHAMACOS study utilized accelerated failure time models (AFTs) which accommodate data with outcomes occurring before or between follow-up visits, but do not allow for estimation of the rate of sexual maturation.

An additional study conducted in Australia looked at associations between maternal serum concentrations of phthalate metabolites during pregnancy and measures of reproductive development in female children of those mothers (Hart et al., 2014). They found marginally significant increased odds of onset of menarche with an increasing sum of MEHP and MECPP concentrations, results that were not seen in our study. Differences in methodology including their use of serum phthalate measurements instead of the preferred urinary measurements (A. Calafat et al., 2015; Johns et al., 2015), pooling of gestational serum samples rather than using repeated measures, and introduction of recall bias from asking participants to recall at what age they initiated menarche (Dorn et al., 2013), may have contributed to differing results between our studies. Lastly, a study conducted in Taiwan measured third trimester phthalate concentrations and tested for associations with various indicators of sexual development later in life (Su et al., 2015). Most outcomes assessed were not consistent with those measured in our study, and children were only followed until 11 years of age when most of them likely had not reached sexual maturity.

Although mechanisms of potential phthalate disruption on sexual development are poorly understood, female rodent studies have shown that exposure to DEHP at various times through the life cycle can alter estradiol concentrations, possibly via upstream deregulation of FSH synthesis or cholesterol transport (Brehm et al., 2017; Davis et al., 1994; Hirosawa et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006; Moyer and Hixon, 2012; Svechnikova et al., 2007). An increase in estradiol concentration is necessary for initiation of enlargement of breast tissue (DiVall and Radovick, 2009), thus these animal studies point to the need to study estrogen disruption as being on the causal pathway from phthalate exposure to altered sexual development.

Our finding that MBP was inversely associated with onset of pubic hair growth in boys suggests that phthalates may have the capacity to disrupt adrenal function. In order for pubic hair growth to begin, DHEA-S from the adrenal gland must travel to target tissues where hair follicles and dermal exocrine glands possess the necessary enzymes to convert DHEA-S into dihydrotestosterone (Auchus and Rainey, 2004). Thus is it local synthesis of testosterone from upstream adrenal regulation, not circulating androgens, that are critical for the initiation of pubic hair growth. Previous animal studies have suggested that in utero phthalate exposure can alter expression of adrenal transcription factors (Lee et al., 2016), reduce serum aldosterone concentrations (Martinez-Arguelles et al., 2011), and down-regulate expression of genes required for cholesterol transport and steroid synthesis (Saillenfait et al., 2013), all possible mechanisms by which phthalates may interfere with adrenal regulation of pubic hair growth.

The present study had several limitations. Though we measured phthalate metabolite concentrations at up to three time points during pregnancy, phthalates are relatively short lived inside the body (Braun et al., 2012; Johns et al., 2015) and thus three measurements may not fully characterize overall gestational exposure. We also did not adjust for adolescent phthalate exposure which could have confounded our results. Additionally, phthalate exposure always occurs as a mixture of metabolites and we did not adjust for concurrent phthalate exposures. It is possible that BMI acts as a mediator on the causal pathway between prenatal phthalate exposure and sexual development, thus our adjustment for BMI at baseline and change in BMI between study visits may have introduced bias to our results. We were not able to begin follow-up before all children initiated puberty, nor were we able to conduct numerous visits thereafter, and thus the exact timing of initiation and progression of maturation from one stage to the next cannot be known. However, the majority of our population had initiated sexual maturation by the second follow-up visit which allowed us to more reliably measure onset and tempo of progression. This builds on previous work from the ELEMENT cohort because we have multiple measures of maturation outcomes. Lastly, our sample size was relatively small and thus our statistical power to detect true associations may be limited.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that gestational phthalate exposure is associated with earlier onset and slower progression of sexual maturation outcomes in girls, particularly breast development. Conversely, gestational phthalate exposure was associated with later onset and faster progression of sexual maturation outcomes in boys, though most associations did not reach statistical significance. Some of our results align with those of previous studies, but our study is methodologically unique. More studies looking at phthalate effects on tempo of sexual maturation among a larger sample of children with more frequent follow-up visits are needed to substantiate our results. Future research will also utilize longitudinal hormone measurements through adolescence to test for possible interactions between hormones and phthalates and the resulting impacts on sexual development.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High molecular weight phthalates were associated with later onset of breast growth

A low molecular weight phthalate was associated with early onset of male pubic hair

Trends of onset and tempo of development were generally in opposite directions

Significant metabolites and directions of associations differed between sexes

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) grants RD834800 and RD83543601 and National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grants P20 ES018171, P01 ES02284401, R01 ES007821, and P30 ES017885. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US EPA. Further, the US EPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication. This work was also supported and partially funded by the National Institute of Public Health, Ministry of Health of Mexico.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aksglaede L, Olsen LW, Sørensen TIA, Juul A, 2008. Forty Years Trends in Timing of Pubertal Growth Spurt in 157, 000 Danish School Children. PLoS One 3, 1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksglaede L, Sørensen K, Petersen JH, Skakkebæk NE, Juul A, 2009. Recent Decline in Age at Breast Development: The Copenhagen Puberty Study. Pediatrics 123, e932 LP–e939. 10.1542/peds.2008-2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle TE, Davis K, Marro L, Fisher M, Legrand M, LeBlanc A, Gaudreau E, Foster WG, Choeurng V, Fraser WD, 2014. Phthalate and bisphenol A exposure among pregnant women in Canada - Results from the MIREC study. Environ. Int 68, 55–65. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchus RJ, Rainey WE, 2004. Adrenarche – physiology, biochemistry and human disease. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 6, 288–296. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berger K, Eskenazi B, Kogut K, Parra K, Lustig RH, Greenspan LC, Holland N, Calafat AM, Ye X, Harley KG, 2018. Association of Prenatal Urinary Concentrations of Phthalates and Bisphenol A and Pubertal Timing in Boys and Girls. Environ. Health Perspect 126, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder AM, Corvalan C, Calafat AM, Ye X, Mericq V, Pereira A, Michels KB, 2018. Childhood and adolescent phenol and phthalate exposure and the age of menarche in Latina girls. Environ. Heal 17, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro AFM, Greenspan LC, 2013. Onset of Breast Development in a Longitudinal Cohort. Pediatrics 132, 1019–1027. 10.1542/peds.2012-3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyne MS, Thame M, Osmond C, Fraser RA, Gabay L, Reid M, Forrester TE, 2010. Growth, body composition, and the onset of puberty: longitudinal observations in Afro-Caribbean children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 95, 3194–3200. 10.1210/jc.2010-0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Smith KW, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Berry K, Ehrlich S, 2012. Variability of Urinary Phthalate Metabolite and Bisphenol A Concentrations before and during Pregnancy. Environ. Health Perspect 120, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm E, Rattan S, Gao L, Flaws JA, 2017. Prenatal Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Causes Long-Term Transgenerational Effects on Female Reproduction in Mice. Endocrinology 159, 795–809. 10.1210/en.2017-03004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck Louis GM, Gray LE, Marcus M, Ojeda SR, Pescovitz OH, Witchel SF, Sippell W, Abbott DH, Soto A, Tyl RW, Bourguignon J-P, Skakkebaek NE, Swan SH, Golub MS, Wabitsch M, Toppari J, Euling SY, 2008. Environmental Factors and Puberty Timing: Expert Panel Research Needs. Pediatrics 121, S192 LP–S207. 10.1542/peds.1813E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyken AE, Karaolis-Danckert N, Remer T, 2008. Association of prepubertal body composition in healthy girls and boys with the timing of early and late pubertal markers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 89, 221–230. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat A, Longnecker M, Koch H, Swan S, Hauser R, Goldman L, Lanphear B, Rudel R, Engel S, Teitelbaum S, Whyatt R, Wolff M, 2015. Optimal Exposure Biomarkers for Nonpersistent Chemicals in Environmental Epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect 123, 2009–2011. 10.1289/ehp.7212.Hines [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Valentin-Blasini L, Ye X, 2015. Trends in Exposure to Chemicals in Personal Care and Consumer Products. Curr. Environ. Heal. Reports 2, 348–355. 10.1007/s40572-015-0065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantonwine DE, Cordero JF, Rivera-González LO, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, Crespo N, Jiménez-Vélez B, Padilla IY, Alshawabkeh AN, Meeker JD, 2014. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among pregnant women in Northern Puerto Rico: Distribution, temporal variability, and predictors. Environ. Int 62, 1–11. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas M, Valvi D, Ballesteros-Gomez A, Gascon M, Fernández MF, Garcia-Esteban R, Iñiguez C, Martínez D, Murcia M, Monfort N, Luque N, Rubio S, Ventura R, Sunyer J, Vrijheid M, 2016. Exposure to bisphenol a and phthalates during pregnancy and ultrasound measures of fetal growth in the INMA-sabadell cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 124, 521–528. 10.1289/ehp.1409190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castorina R, Bradman A, McKone TE, Barr DB, Harnly ME, Eskenazi B, 2003. Cumulative organophosphate pesticide exposure and risk assessment among pregnant women living in an agricultural community: A case study from the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 111, 1640–1648. 10.1289/ehp.5887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro JE, Watkins DJ, Afeiche MC, Zhang Z, Sánchez BN, Cantonwine D, Mercado-garcía A, Blank-goldenberg C, Meeker JD, Téllez-rojo MM, Peterson KE, 2017. Validity of Self-Assessed Sexual Maturation Against Physician Assessments and Hormone Levels. J. Pediatr 186, 172–178.e3. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Zhang Y, Sun W, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Song Y, Lin Q, Zhu L, Zhu Q, Wang X, Liu S, Jiang F, 2017. Investigating the relationship between precocious puberty and obesity: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China. BMJ Open 7, 1–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li L, Li H, Guan H, Dong Y, Li X, Wang Q, Lian Q, Hu G, Ge R, 2017. Prenatal exposure to di-n -butyl phthalate disrupts the development of adult Leydig cells in male rats during puberty. Toxicology 386, 19–27. 10.1016/j.tox.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BJ, Maronpot RR, Heindel JJ, 1994. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Suppresses Estradiol and Ovulation in Cycling Rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 128, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereumeaux C, Saoudi A, Pecheux M, Berat B, de Crouy-Chanel P, Zaros C, Brunel S, Delamaire C, le Tertre A, Lefranc A, Vandentorren S, Guldner L, 2016. Biomarkers of exposure to environmental contaminants in French pregnant women from the Elfe cohort in 2011. Environ. Int 97, 56–67. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiVall SA, Radovick S, 2009. Endocrinology of female puberty. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn L, Sontag-Padilla L, Pabst S, Tissot A, Susman E, 2013. Longitudinal Reliability of Self-Reported Age at Menarche in Adolescent Girls: Variability Across Time and Setting. Dev. Psychol 49, 1187–1193. 10.1037/a0029424.Longitudinal [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elks CE, Perry JRB, Sulem P, Chasman DI, Franceschini N, He C, Lunetta KL, Visser JA, Byrne EM, Cousminer DL, Gudbjartsson DF, Esko T, Feenstra B, Hottenga J-J, Koller DL, Kutalik Z, Lin P, Mangino M, Marongiu M, McArdle PF, Smith AV, Stolk L, van Wingerden SH, Zhao JH, Albrecht E, Corre T, Ingelsson E, Hayward C, Magnusson PKE, Smith EN, Ulivi S, Warrington NM, Zgaga L, Alavere H, Amin N, Aspelund T, Bandinelli S, Barroso I, Berenson GS, Bergmann S, Blackburn H, Boerwinkle E, Buring JE, Busonero F, Campbell H, Chanock SJ, Chen W, Cornelis MC, Couper D, Coviello AD, d’Adamo P, de Faire U, de Geus EJC, Deloukas P, Döring A, Smith GD, Easton DF, Eiriksdottir G, Emilsson V, Eriksson J, Ferrucci L, Folsom AR, Foroud T, Garcia M, Gasparini P, Geller F, Gieger C, Consortium TG, Gudnason V, Hall P, Hankinson SE, Ferreli L, Heath AC, Hernandez DG, Hofman A, Hu FB, Illig T, Järvelin M-R, Johnson AD, Karasik D, Khaw K-T, Kiel DP, Kilpeläinen TO, Kolcic I, Kraft P, Launer LJ, Laven JSE, Li S, Liu J, Levy D, Martin NG, McArdle WL, Melbye M, Mooser V, Murray JC, Murray SS, Nalls MA, Navarro P, Nelis M, Ness AR, Northstone K, Oostra BA, Peacock M, Palmer LJ, Palotie A, Paré G, Parker AN, Pedersen NL, Peltonen L, Pennell CE, Pharoah P, Polasek O, Plump AS, Pouta A, Porcu E, Rafnar T, Rice JP, Ring SM, Rivadeneira F, Rudan I, Sala C, Salomaa V, Sanna S, Schlessinger D, Schork NJ, Scuteri A, Segrè AV, Shuldiner AR, Soranzo N, Sovio U, Srinivasan SR, Strachan DP, Tammesoo M-L, Tikkanen E, Toniolo D, Tsui K, Tryggvadottir L, Tyrer J, Uda M, van Dam RM, van Meurs JBJ, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Wareham NJ, Waterworth DM, Weedon MN, Wichmann HE, Willemsen G, Wilson JF, Wright AF, Young L, Zhai G, Zhuang WV, Bierut LJ, Boomsma DI, Boyd HA, Crisponi L, Demerath EW, van Duijn CM, Econs MJ, Harris TB, Hunter DJ, Loos RJF, Metspalu A, Montgomery GW, Ridker PM, Spector TD, Streeten EA, Stefansson K, Thorsteinsdottir U, Uitterlinden AG, Widen E, Murabito JM, Ong KK, Murray A, 2010. Thirty new loci for age at menarche identified by a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet 42, 1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Meeker JD, 2014a. Environmental phthalate exposure and preterm birth. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 61–67. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Chen YH, Mukherjee B, McElrath TF, 2016. Urinary phthalate metabolite and bisphenol A associations with ultrasound and delivery indices of fetal growth. Environ. Int 94, 531–537. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, Peterson KE, Lee JM, Mercado-garcía A, Blank-goldenberg C, Téllez-rojo MM, Meeker JD, 2014b. Prenatal and peripubertal phthalates and bisphenol A in relation to sex hormones and puberty in boys. Reprod. Toxicol 47, 70–76. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen H, Sørensen K, Mouritsen A, Aksglaede L, Hagen CP, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE, Andersson A, Juul A, 2012. High urinary phthalate concentration associated with delayed pubarche in girls. Int. J. Androl 35, 216–226. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German A, Shmoish M, Belsky J, Hochberg Z, 2018. Outcomes of pubertal development in girls as a function of pubertal onset age. Eur. J. Endocrinol 179, 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley KG, Berger K, Rauch S, Kogut K, Claus Henn B, Calafat AM, Huen K, Eskenazi B, Holland N, 2017. Association of prenatal urinary phthalate metaboite concentrations and shildhood BMI and obesity. Pediatr. Res 82, 405–415. 10.1038/pr.2017.112.Association [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley KG, Berger KP, Kogut K, Parra K, Lustig RH, Greenspan LC, Calafat AM, Ye X, Eskenazi B, 2019. Association of phthalates, parabens and phenols found in personal care products with pubertal timing in girls and boys. Hum. Reprod 34, 109–117. 10.1093/humrep/dey337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart R, Doherty DA, Frederiksen H, Keelan JA, Hickey M, Sloboda D, Pennell CE, Newnham JP, Skakkebaek NE, Main KM, 2014. The influence of antenatal exposure to phthalates on subsequent female reproductive development in adolescence: A pilot study. Reproduction 147, 379–390. 10.1530/REP-13-0331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Calafat AM, 2005. Phthalates and human health. Occup. Environ. Med 62, 806–818. 10.1136/oem.2004.017590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Giddens M, Steffes J, Harris D, Slora E, Hussey M, Dowshen SA, Wasserman R, Serwint JR, Smitherman L, Reiter EO, 2012. Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys : Data From the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics 130, 1058–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosawa N, Yano K, Suzuki Y, Sakamoto Y, 2006. Endocrine disrupting effect of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on female rats and proteome analyses of their pituitaries. Proteomics 6, 958–971. 10.1002/pmic.200401344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdeshell KL, Rider CV, Wilson VS, Gray LE, 2008. Mechanisms of action of phthalate esters, individually and in combination, to induce abnormal reproductive development in male laboratory rats. Environ. Res 108, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Du G, Zhang W, Huang H, Chen D, Wu D, Wang X, 2013. Short-term neonatal / prepubertal exposure of dibutyl phthalate (DBP) advanced pubertal timing and affected hypothalamic kisspeptin / GPR54 expression differently in female rats. Toxicology 314, 65–75. 10.1016/j.tox.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns LE, Cooper GS, Galizia A, Meeker JD, 2015. Exposure assessment issues in epidemiology studies of phthalates. Environ. Int 85, 27–39. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz PB, 2008. Link Between Body Fat and the Timing of Puberty. Pediatrics 121, S208–S217. 10.1542/peds.2007-1813F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper-Sonnenberg M, Wittsiepe J, Wald K, Koch HM, Wilhelm M, 2017. Pre-pubertal exposure with phthalates and bisphenol A and pubertal development. PLoS One 12, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay VR, Bloom MS, Foster WG, 2014. Reproductive and developmental effects of phthalate diesters in males. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 44, 467–498. 10.3109/10408444.2013.875983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber M, Alexandra S, Thomas R, 2011. Obesity in children and adolescents: relationship to growth, pubarche, menarche, and voice break. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab 10.1515/jpem.2011.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko KP, Kim SW, Ma SH, Park B, Ahn Y, Lee JW, Lee MH, Kang E, Kim LS, Jung Y, Cho YU, Lee B, Lin JH, Park SK, 2013. Dietary intake and breast cancer among carriers and noncarriers of BRCA mutations in the korean hereditary breast cancer study1–3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 98, 1493–1501. 10.3945/ajcn.112.057760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Lumeng JC, 2007. Weight Status in Young Girls and the Onset of Puberty. Pediatrics 119, e624–30. 10.1542/peds.2006-2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Kaciroti N, Appugliese D, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Lumeng JC, 2010. Body Mass Index and Timing of Pubertal Initiation in BoysBMI and Timing of Pubertal Initiation in Boys. JAMA Pediatr. 164, 139–144. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Martinez-Arguelles DB, Campioli E, Papadopoulos V, 2016. Fetal Exposure to Low Levels of the Plasticizer DEHP Predisposes the Adult Male Adrenal Gland to Endocrine Disruption. Endocrinology 158, 304–318. 10.1210/en.2016-1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RC, Meeker JD, Peterson KE, Lee JM, Pace GG, Cantoral A, Téllez-rojo MM, 2013. Predictors of urinary bisphenol A and phthalate metabolite concentrations in Mexican children. Chemosphere 93, 2390–2398. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Kondo T, Ban S, Umemura T, Kurahashi N, Takeda M, Kishi R, 2006. Exposure of Prepubertal Female Rats to Inhaled Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate Affects the Onset of Puberty and Postpubertal Reproductive Functions. Toxicol. Sci 93, 164–171. 10.1093/toxsci/kfl036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM, 1970. Variations in the Pattern of Pubertal Changes in Boys. Arch. Dis. Child 45, 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM, 1969. Variations in Pattern of Pubertal Changes in Girls. Arch. Dis. Child 44, 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Arguelles DB, Guichard T, Culty M, Zirkin BR, Papadopoulos V, 2011. In Utero Exposure to the Antiandrogen Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Decreases Adrenal Aldosterone Production in the Adult Rat1. Biol. Reprod 85, 51–61. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Hu H, Cantonwine DE, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Calafat AM, Ettinger AS, Hernandez-Avila M, Loch-Caruso R, Téllez-Rojo MM, 2009. Urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to preterm birth in Mexico City. Environ. Health Perspect 117, 1587–1592. 10.1289/ehp.0800522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen Annette, Aksglaede L, Soerensen K, Hagen CP, Petersen JH, Main KM, Juul A, 2013. The pubertal transition in 179 healthy Danish children : associations between pubarche, adrenarche, gonadarche, and body composition. Eur. J. Endocrinol 168, 129–136. 10.1530/EJE-12-0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen A, Frederiksen H, Sorensen K, Aksglaede L, Hagen C, Skakkebaek NE, Main KM, Andersson AM, Juul A, 2013. Urinary phthalates from 168 girls and boys measured twice a year during a 5-year period: Associations with adrenal androgen levels and puberty. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 98, 3755–3764. 10.1210/jc.2013-1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer B, Hixon ML, 2012. Reproductive effects in F1 adult females exposed in utero to moderate to high doses of mono-2-ethylhexylphthalate (MEHP). Reprod. Toxicol 34, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu D, Gao F, Fan Z, Shen H, Peng H, Hu J, 2015. Levels of Phthalate Metabolites in Urine of Pregnant Women and Risk of Clinical Pregnancy Loss. Environ. Sci. Technol 49, 10651–10657. 10.1021/acs.est.5b02617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KK, Elks CE, Li S, Zhao JH, Luan J, Lars B, Gillson CJ, Glaser B, Golding J, Hardy R, Khaw K, 2009. Genetic variation in LIN28B is associated with the timing of puberty. Nat. Genet 41, 729–733. 10.1038/ng.382.Genetic [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantsiotou S, Papadimitriou A, Douros K, Priftis K, Nicolaidou P, Fretzayas A, 2008. Maturational tempo differences in relation to the timing of the onset of puberty in girls. Acta Paediatr. 97, 217–220. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F, Ji W, Zhu F, Peng D, Yang M, Liu R, Pu Y, Yin L, 2016. A study on phthalate metabolites, bisphenol A and nonylphenol in the urine of Chinese women with unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Environ. Res 150, 622–628. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JRB, Day F, Elks CE, Sulem P, Thompson DJ, Ferreira T, He C, Chasman DI, Esko T, Thorleifsson G, Albrecht E, Ang WQ, Corre T, Cousminer DL, Feenstra B, Franceschini N, Ganna A, Johnson AD, Kjellqvist S, Lunetta KL, McMahon G, Nolte IM, Paternoster L, Porcu E, Smith AV, Stolk L, Teumer A, Tšernikova N, Tikkanen E, Ulivi S, Wagner EK, Amin N, Bierut LJ, Byrne EM, Hottenga J-J, Koller DL, Mangino M, Pers TH, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Hua Zhao J, Andrulis IL, Anton-Culver H, Atsma F, Bandinelli S, Beckmann MW, Benitez J, Blomqvist C, Bojesen SE, Bolla MK, Bonanni B, Brauch H, Brenner H, Buring JE, Chang-Claude J, Chanock S, Chen J, Chenevix-Trench G, Collée JM, Couch FJ, Couper D, Coviello AD, Cox A, Czene K, D’adamo AP, Davey Smith G, De Vivo I, Demerath EW, Dennis J, Devilee P, Dieffenbach AK, Dunning AM, Eiriksdottir G, Eriksson JG, Fasching PA, Ferrucci L, Flesch-Janys D, Flyger H, Foroud T, Franke L, Garcia ME, García-Closas M, Geller F, de Geus EEJ, Giles GG, Gudbjartsson DF, Gudnason V, Guénel P, Guo S, Hall P, Hamann U, Haring R, Hartman CA, Heath AC, Hofman A, Hooning MJ, Hopper JL, Hu FB, Hunter DJ, Karasik D, Kiel DP, Knight JA, Kosma V-M, Kutalik Z, Lai S, Lambrechts D, Lindblom A, Mägi R, Magnusson PK, Mannermaa A, Martin NG, Masson G, McArdle PF, McArdle WL, Melbye M, Michailidou K, Mihailov E, Milani L, Milne RL, Nevanlinna H, Neven P, Nohr EA, Oldehinkel AJ, Oostra BA, Palotie A, Peacock M, Pedersen NL, Peterlongo P, Peto J, Pharoah PDP, Postma DS, Pouta A, Pylkäs K, Radice P, Ring S, Rivadeneira F, Robino A, Rose LM, Rudolph A, Salomaa V, Sanna S, Schlessinger D, Schmidt MK, Southey MC, Sovio U, Stampfer MJ, Stöckl D, Storniolo AM, Timpson NJ, Tyrer J, Visser JA, Vollenweider P, Völzke H, Waeber G, Waldenberger M, Wallaschofski H, Wang Q, Willemsen G, Winqvist R, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Wright MJ, Study, A.O.C., Network, T.G., kConFab, Study, T.L.C., Consortium, T.I., Consortium, E.G.G. (EGG), Boomsma DI, Econs MJ, Khaw K-T, Loos RJF, McCarthy MI, Montgomery GW, Rice JP, Streeten EA, Thorsteinsdottir U, van Duijn CM, Alizadeh BZ, Bergmann S, Boerwinkle E, Boyd HA, Crisponi L, Gasparini P, Gieger C, Harris TB, Ingelsson E, Järvelin M-R, Kraft P, Lawlor D, Metspalu A, Pennell CE, Ridker PM, Snieder H, Sørensen TIA, Spector TD, Strachan DP, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Widen E, Zygmunt M, Murray A, Easton DF, Stefansson K, Murabito JM, Ong KK, 2014. Parent-of-origin-specific allelic associations among 106 genomic loci for age at menarche. Nature 514, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML, 2009. Thelarche, Pubarche, and Menarche Attainment in Children With Normal and Elevated Body Mass Index. Pediatrics 123, 84–88. 10.1542/peds.2008-0146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saillenfait AM, Sabaté JP, Robert A, Rouiller Fabre V, Roudot AC, Moison D, Denis F, 2013. Dose-dependent alterations in gene expression and testosterone production in fetal rat testis after exposure to di-n-hexyl phthalate. J. Appl. Toxicol 33, 1027–1035. 10.1002/jat.2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarr MM, Grantz KL, Sundaram R, Maisog JM, Kannan K, Louis GMB, 2015. Parental urinary biomarkers of preconception exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates in relation to birth outcomes. Environ. Heal. A Glob. Access Sci. Source 14, 1–11. 10.1186/s12940-015-0060-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen K, Aksglaede L, Petersen JH, Juul A, 2010. Recent Changes in Pubertal Timing in Healthy Danish Boys : Associations with Body Mass Index. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 95, 263–270. 10.1210/jc.2009-1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srilanchakon K, Thadsri T, Jantarat C, Thengyai S, 2017. Higher phthalate concentrations are associated with precocious puberty in normal weight Thai girls. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab 30, 1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su P, Chang C, Lin C, Chen H, Liao P, Hsiung CA, Chiang H, Wang S, 2015. Prenatal exposure to phthalate ester and pubertal development in a birth cohort in central Taiwan : A 12-year follow-up study. Environ. Res 136, 324–330. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svechnikova I, Svechnikov K, Söder O, 2007. The influence of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on steroidogenesis by the ovarian granulosa cells of immature female rats. J. Endocrinol 194, 603–609. 10.1677/JOE-07-0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft G, Jönsson BAG, Lindh CH, Jensen TK, Hjollund NH, Vested A, Bonde JP, 2012. Association between pregnancy loss and urinary phthalate levels around the time of conception. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 458–463. 10.1289/ehp.1103552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvi D, Monfort N, Ventura R, Casas M, Casas L, Sunyer J, Vrijheid M, 2015. Variability and predictors of urinary phthalate metabolites in Spanish pregnant women. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 218, 220–231. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizmanos B, Monasterolo RC, Subı JE, 2004. Onset of puberty at eight years of age in girls determines a specific tempo of puberty but does not affect adult height. Acta Paediatr. 93, 874–879. 10.1080/08035250410025979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yang Q, Liu W, Yu M, Zhang Z, Cui X, 2016. DEHP exposure in utero disturbs sex determination and is potentially linked with precocious puberty in female mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 307, 123–129. 10.1016/j.taap.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Milewski S, Domino SE, Meeker JD, Padmanabhan V, 2016. Maternal phthalate exposure during early pregnancy and at delivery in relation to gestational age and size at birth: A preliminary analysis. Reprod Toxicol 65, 59–66. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.06.021.Maternal [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Sánchez BN, Téllez-Rojo MM, Lee JM, Mercado-García A, Blank-Goldenberg C, Peterson KE, Meeker JD, 2017a. Impact of phthalate and BPA exposure during in utero windows of susceptibility on reproductive hormones and sexual maturation in peripubertal males. Environ. Heal. A Glob. Access Sci. Source 16, 1–10. 10.1186/s12940-017-0278-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Sánchez BN, Téllez-Rojo MM, Lee JM, Mercado-García A, Blank-Goldenberg C, Peterson KE, Meeker JD, 2017b. Phthalate and bisphenol A exposure during in utero windows of susceptibility in relation to reproductive hormones and pubertal development in girls. Environ. Res 159, 143–151. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.07.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Téllez-Rojo MM, Ferguson KK, Lee JM, Solano-Gonzalez M, Blank-Goldenberg C, Peterson KE, Meeker JD, 2014. In utero and peripubertal exposure to phthalates and BPA in relation to female sexual maturation. Environ. Res 134, 233–241. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff MS, Teitelbaum SL, McGovern K, Windham GC, Pinney SM, Galvez M, Calafat AM, Kushi LH, Biro FM, 2014. Phthalate exposure and pubertal development in a longitudinal study of US girls. Hum. Reprod 29, 1558–1566. 10.1093/humrep/deu081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff MS, Teitelbaum SL, Pinney SM, Windham G, Liao L, Biro F, Kushi LH, Erdmann C, Hiatt RA, Rybak ME, Calafat AM, 2010. Investigation of relationships between urinary biomarkers of phytoestrogens, phthalates, and phenols and pubertal stages in girls. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 1039–1046. 10.1289/ehp.0901690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2007. Growth reference data for 5–19 years [WWW Document]. URL https://www.who.int/growthref/en/ (accessed 5.8.19).

- Yang C, Peterson KE, Meeker JD, Sánchez BN, Zhang Z, Cantoral A, Solano M, Tellez-rojo MM, 2017. Bisphenol A and phthalates in utero and in childhood: association with child BMI z-score and adiposity. Environ. Res 156, 326–333. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman FA, Boudet C, Tack K, Floch Barneaud A, Brochot C, Péry ARR, Oleko A, Vandentorren S, 2013. Exposure assessment of phthalates in French pregnant women: Results of the ELFE pilot study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 216, 271–279. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cao Y, Shi H, Jiang X, Zhao Y, Fang X, Xie C, 2015. Could exposure to phthalates speed up or delay pubertal onset and development ? A 1. 5-year follow-up of a school-based population. Environ. Int 83, 41–49. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Gao L, Flaws JA, 2017. Prenatal exposure to an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture disrupts reproduction in F1 female mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 318, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.