Abstract

Chemotherapeutic drugs are widely utilized in the treatment of human cancers. Painful chemotherapy-induced neuropathy is a common, debilitating, and dose-limiting side effect for which there is currently no effective treatment. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential utility of peptides from the marine snail from the genus Conus for the treatment of neuropathic pain. α-Conotoxin RgIA and a potent analog, RgIA4, have previously been shown to prevent the development of neuropathy resulting from the administration of oxaliplatin, a platinum-based antineoplastic drug. Here, we have examined its efficacy against paclitaxel, a chemotherapeutic drug that works by a mechanism of action distinct from that of oxaliplatin. Paclitaxel was administered at 2 mg/kg (intraperitoneally (IP)) every other day for a total of 8 mg/kg. Sprague Dawley rats that were co-administered RgIA4 at 80 µg/kg (subcutaneously (SC)) once daily, five times per week, for three weeks showed significant recovery from mechanical allodynia by day 31. Notably, the therapeutic effects reached significance 12 days after the last administration of RgIA4, which is suggestive of a rescue mechanism. These findings support the effects of RgIA4 in multiple chemotherapeutic models and the investigation of α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) as a non-opioid target in the treatment of chronic pain.

Keywords: nicotinic, chemotherapy, paclitaxel, taxane, neuropathic pain, α9α10, conotoxin

1. Introduction

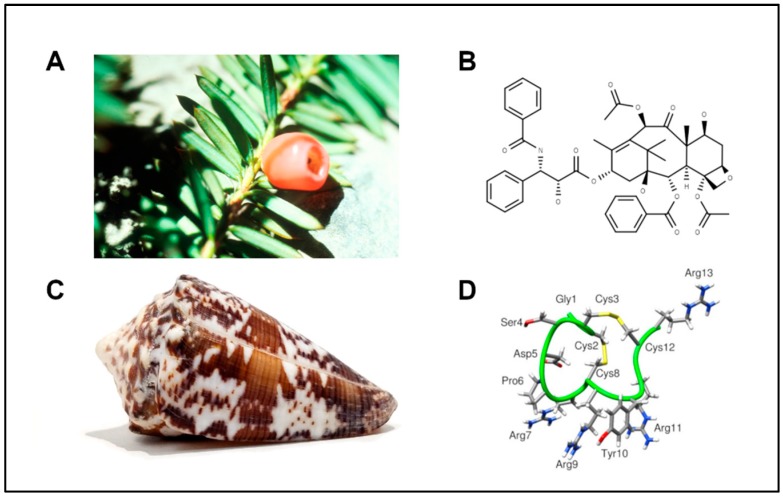

Neuropathic pain is a type of chronic pain that stems from the damage or disease of the sensory nervous system that affects an estimated 6.9–10% of the general population [1]. This type of pathological pain has many causes, including traumatic nerve injury, metabolic disorders such as diabetes, and chemical damage from chemotherapeutics [2]. Paclitaxel (Figure 1) is an anti-cancer drug of the taxane family, initially extracted from the bark of the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), and perhaps the most well-known natural-product chemotherapeutic. It is used as a first-line treatment for breast, ovarian, and non-small cell lung cancers [3]. Several chemotherapies from different drug families, including taxane- and platinum-based drugs, have been characterized to produce painful neuropathies as a side effect. In the context of cancer therapies, these side effects can be more than disruptive as they are often dose-limiting in treatment regimens [4].

Figure 1.

Natural sources of potential therapeutics. (A) The needles and berries of a Pacific yew, characteristic of the tree from which paclitaxel was originally extracted. (B) Chemical structure of paclitaxel. (C) Shell of the worm-hunting snail, Conus regius, from which RgIA was originally characterized. (D) Structure of the short 13-amino-acid peptide RgIA isolated from Conus regius. Image sources: (A) Yew Needles and Berries, National Cancer Institute Visuals Online, no. AV-9100-3761. (C) Conus regius photograph by Peter Huynh.

Patients have exhibited several types of neuropathies, including numbness, chronic pain, and allodynia (painful hypersensitivity) to mechanical or thermal stimuli [5]. Amongst patients, however, the type, duration, and severity of neuropathy can vary [6]. While the prevalence and manifestations of paclitaxel-induced neuropathy have been well documented, the underlying mechanisms are still being characterized. Several adjuvant treatments have been used in an attempt to combat the effects of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). However, there are currently no FDA-approved medications for the prevention or treatment of CIPN.

Cone snails have historically displayed a repertoire of therapeutic molecules. The venomous marine gastropods of the genus Conus are a diverse collection of snails that have developed complex hunting and envenomation strategies. The venoms of these snails contain hundreds of unique peptides, and the contents of these venoms can also change in response to defensive or predatory stimuli [7]. Cone snails have refined a suite of bioactive peptides that can exquisitely and potently discriminate among receptors involved in neurotransmission. These targets include G-protein-coupled receptors and voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels [8]. The chemical arsenal of each snail also contains bioactive compounds that have been characterized as prey-endogenous mimetics, such as the insulin-like peptide used by Conus geographus, which more closely resembles fish insulin than its own [9]. The discovery of this molecular mimicry strategy spurred the characterization of several other hormone/neuropeptide-like peptides in the venom repertoire of these snails [10].

Currently, there are an estimated 750+ species of cone snails whose venom components include small, disulfide-rich peptides that have been classified into at least 28 different superfamilies. These superfamilies are primarily subdivided by their conserved cysteine frameworks. Further characterization of cone snail venom ducts have also revealed the presence of small molecules that contribute to their venom activity [11]. Previous estimates of 50–200 unique compounds per venom have been expanded nearly 10-fold with the advancement of mass spectroscopy and venomics techniques. These estimates yield a collection of greater than 1 million potential lead peptide compounds to be characterized, less than 1% of which (~10,000) have been partially characterized [12,13]. While advancements in genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics have rapidly accelerated the discovery of conotoxin peptides, the structural and pharmacological characterization has been rate-limiting. Notably, the ω-conotoxin MVIIA (Prialt® (ziconotide)), a non-opioid drug for intractable pain, remains the only FDA-approved conotoxin-based drug to date [14,15]. The majority of bioactive wealth from cone snail venoms awaits to be characterized. The classification and therapeutic applications of conotoxins have been reviewed in considerable detail [7,8,10,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Among the smallest of the peptides found in Conus venoms are the α-conotoxins, which competitively inhibit nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [16]. α-conotoxins are typically 13–20 amino acids in length and disulfide-constrained. nAChRs are pentamers typically assembled from α and non-α subunits including α1–α10, β1–β4, and γ, δ, and ε in coordinated distributions. There are also homomeric assemblies consisting only of α-subunits. Together, these subunit combinations yield a large diversity of potential nAChR subtypes.

Previously, we have reported the specific block of α9α10 nAChRs by the α-conotoxin RgIA [21,22]. This 13-amino-acid peptide, isolated from the worm-hunting snail Conus regius, blocked the rodent α9α10 nAChR with high potency; however, it was found to be approximately 300-fold less potent on the human receptor due to a single amino-acid substitution in the α9 nAChR subunit [23]. The second-generation synthetic analog, RgIA4, was engineered to close this affinity gap across the rodent and human α9α10 nAChRs (IC50 rat = 0.9 nM; IC50 human = 1.5 nM), and has also been shown to effectively prevent oxaliplatin-induced pain in rats and mice [24,25]. These findings are consistent with previous behavioral and cellular studies that demonstrate native RgIA can prevent the development and/or progression of neuropathic pain in chronic constriction injury and oxaliplatin-induced injury [26,27,28]. RgIA and several other α-conotoxins from worm-hunting Conus species act on ancestral nAChRs such as α9, α10, or α7-containing subtypes. While these α-conotoxins may incapacitate their native prey, their effect on higher-order species is more nuanced, since the target receptors may play roles outside the neuromuscular junction [29]. Here, we show that, in addition to preventing oxaliplatin-derived neuropathic pain, RgIA4 is efficacious in accelerating recovery from paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain in rats.

2. Results

2.1. RgIA4 Accelerates Recovery from Paclitaxel-Induced Allodynia in Sprague Dawley Rats

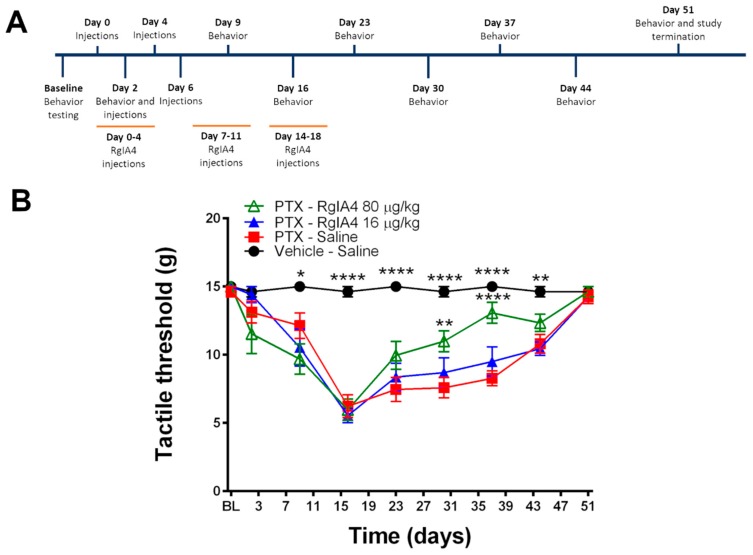

Semisynthetic taxanes, including paclitaxel, are first-line treatments for the most common solid tumors, but taxane-induced peripheral neurotoxicity is a frequent dose-limiting side effect. Sprague Dawley (SD) rats are commonly used to model paclitaxel-mediated CIPN due to the consistent induction of mechanical and thermal allodynia and ease of behavioral readouts compared to mice [30,31,32]. A clinical formulation of paclitaxel was chosen in order to induce a longer-lasting neuropathic pain effect [31]. Adult SD rats were injected four times intraperitoneally (IP) with paclitaxel (2.0 mg/kg) on days 0, 2, 4, and 6, for a total dosage of 8.0 mg/kg. Over the course of the paclitaxel injections and over the next 12 days, rats were also administered daily subcutaneous (SC) injections of RgIA4 at 16 and 80 µg/kg five days per week (days 0–18) (Figure 2A). To assay for mechanoreceptive properties of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain, SD rats were tested through hindpaw von Frey analysis.

Figure 2.

RgIA4 accelerates recovery from mechanical allodynia. (A) Study timeline. Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (n = 8) were treated with either vehicle (intraperitoneally (IP))-saline (subcutaneously (SC)), 8 mg/kg paclitaxel (PTX) (IP)-saline (SC), 8 mg/kg paclitaxel (IP)-RgIA4 (80 μg/kg; SC), or 8 mg/kg paclitaxel (IP)-RgIA4 (16 µg/kg; SC). Animals were tested for behavior prior to the first dose of paclitaxel (baseline (BL)) and over the course of 51 days. (B) Testing results from Von Frey assay. Results are expressed as tactile threshold values in grams (g). Black circles: vehicle-saline; red squares: PTX-saline; blue triangles: PTX-RgIA4 (16 µg/kg); hollow green triangles: PTX-RgIA4 (80 µg/kg). Mean +/- SEM are indicated. Two-way ANOVA was conducted followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, alpha = 0.05. Asterisks denote a significant difference from the PTX-Saline curve (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and **** p < 0.0001).

Compared to vehicle-injected animals, paclitaxel-injected rats showed a robust, painful sensitization to previously non-painful mechanical stimuli by day 9 which persisted through day 44 (Figure 2B). These effects peaked on day 16, where the paclitaxel (PTX)-saline-treated rats exhibited a pain response from the Von Frey filaments, withdrawing or licking their paw at a mean threshold of 6.2 g, compared to the vehicle-saline-treated rats, whose threshold was at a mean force of 14.6 g. Co-administration of RgIA4 (16 or 80 μg/kg; SC) did not produce analgesic effects during the induction of neuropathic pain (days 0–16).

By day 23, the paclitaxel-treated groups began a modest recovery from their mechanical allodynia. However, by day 31, rats treated with 80 μg/kg of RgIA4 showed accelerated recovery from the paclitaxel-induced hypersensitivity, reaching significance compared to the paclitaxel-saline-treated rats (p < 0.01, as determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferonni’s multiple comparison test). The rate of recovery by the RgIA4 (80 μg/kg)-treated rats maximally outpaced all other groups by day 37 (p < 0.0001). Remarkably, this therapeutic effect was first reached 12 days after treatment with RgIA4 had been stopped.

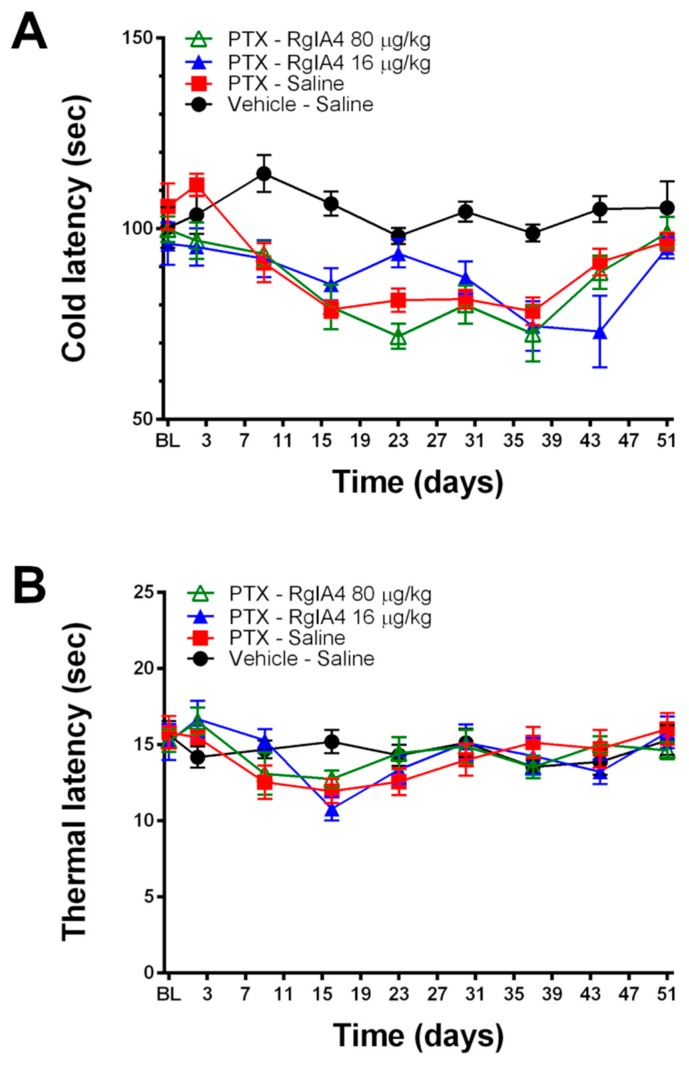

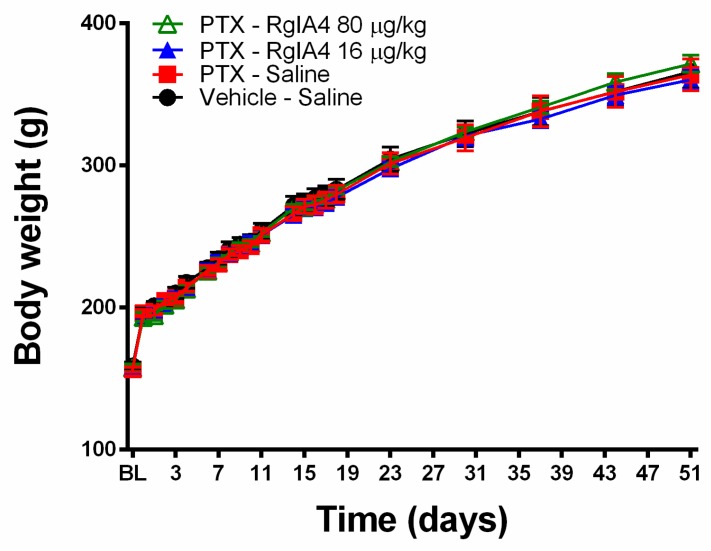

Further analysis of thermoreceptive properties revealed no ameliorative effects of RgIA4 at either dosage as determined by a cold plate assay (Figure 3). Neither paclitaxel nor RgIA4 affected heat allodynia, as measured by the Hargreaves test, nor the weight gain of the animals over the course of the experiment (Figure 4). The dosages of 80 and 16 μg/kg were chosen based on previously characterized regimens that effectively produced relief in neuropathic pain models in mice and rats [24,25]. These dosages have been previously reported to produce no adverse effects in motor coordination nor CNS function based on rotarod and Irwin tests [25].

Figure 3.

RgIA4 did not reverse cold allodynia and paclitaxel did not induce heat allodynia under these conditions. Testing results from (A) cold plate and (B) Hargreaves assays following treatment of SD rats (n = 8 per group, unless otherwise noted) with a total dose of 8 mg/kg paclitaxel with or without RgIA4 at 80 or 16 μg/kg. Animals were tested for behavior from the first dose of paclitaxel (BL) over the course of 51 days. Results are expressed in (A) cold and (B) thermal latency times in seconds (s). Black circles: vehicle-saline; red squares: PTX-saline; blue triangles: PTX-RgIA4 (16 μg/kg); hollow green triangles: PTX- RgIA4 (80 μg/kg). Mean +/- SEM are indicated.

Figure 4.

Neither paclitaxel nor RgIA4 significantly affected body weight over time. Changes in rat body weight (in g) are indicated following treatment with a total dose of 8 mg/kg paclitaxel, with or without RgIA4 at 80 or 16 μg/kg. Readings were taken from cohorts of n = 8 rats per group, unless otherwise specified. Black circles: vehicle-saline; red squares: PTX-saline; blue triangles: PTX-RgIA4 (16 μg/kg); hollow green triangles: PTX-RgIA4 (80 μg/kg). Mean +/- SEM are indicated.

2.2. Paclitaxel Did Not Induce Mechanical Allodynia in C57BL/6J Mice

Rats have been widely used in models of neuropathic pain. When mice are used, the C57BL/6J mouse is perhaps the most commonly used inbred strain; its entire genome has been sequenced, and a wide variety of transgenics are available. The effectiveness of inducing CIPN pain in C57BL/6J mice with paclitaxel, however, has been reported with varying levels of success. Some previous reports showed robust induction of CIPN by paclitaxel in C57BL/6J mice, while others were not able to create this pain state [32,33]. The diverse genetic background of inbred mouse strains has historically resulted in variable levels of CIPN severity. This has been documented across several strains of mice with both paclitaxel and oxaliplatin as the agent of induction [32,34]. Additional, early genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have suggested genetic predispositions to CIPN pain [35]. This is also reflective of clinical reports, where the severity and duration of painful neuropathy varies between patients [4].

In our experiments, administration of C57BL/6J mice with 2.0 mg/kg of paclitaxel (IP) on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 did not produce a statistically significant change in mechanical allodynia as measured by Von Frey (Supplemental Figure S1). As a measure of neurophysiological integrity, the velocity and amplitudes of sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) are commonly used as a readout in both clinical and preclinical settings [36,37]. Previous studies have reported the reduction of action potential amplitude in patients receiving paclitaxel as the duration of their treatment regimen progressed [38]. In our cohort of C57/BL6 mice, there was no change in observed nerve conduction velocities (NCVs) nor amplitudes of SNAPs in the tail between treated and untreated mice (Supplemental Figure S2). Due to the lack of robust induction under these conditions, we did not continue with further behavioral tests in C57BL/6J mice.

3. Discussion

3.1. α9α10 nAChRs as a Target for Pain Treatment

RgIA4 has been previously shown to prevent the induction of CIPN pain by the platinum-based chemotherapeutic, oxaliplatin [24,25]. Since chemotherapeutic agents work by different mechanisms of action to inhibit tumor growth, we wished to assess the activity of RgIA4 in taxane-induced neuropathic pain [39]. Taxanes are effective treatments for breast cancer; however, neuropathic pain is a common side effect. After two years of treatment, over 40% of women indicated that they still experience neuropathy symptoms with compromised long-term quality of life [40,41]. There are currently no recommended agents for the prevention of taxane-induced neuropathic pain. The positive outcome for RgIA4 indicates broader applicability of α9α10 nAChR antagonists for preventing symptoms of CIPN.

In this study, the repeated and intermittent administration of clinically-formulated dosages of paclitaxel produced a robust mechanical allodynia which was consistent with previous reports in both humans and rodents [5]. A previously-observed coasting phenomenon was also present in which symptoms could continue and even intensify after cessation of treatment. In this study, symptoms peaked in intensity on day 16, ten days after the last administration of paclitaxel; a similar phenomenon has been reported in clinical settings and successfully reproduced in rodent models [31,42]. The administration of RgIA4 five days per week for three weeks successfully accelerated the recovery from paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia in a dose-dependent manner. The effects of RgIA4 only became evident after repeated dosages and did not reach significance until day 30, approximately 12 days after the RgIA4 administration had been discontinued. This delay in efficacy is consistent with our previous reports of both native RgIA in chronic constriction injury models of neuropathic pain and RgIA4 in oxaliplatin-mediated neuropathic pain. The time course of symptom relief is consistent with a disease-modifying effect of RgIA4 rather than just a pain-masking effect [24,25,26]. In future studies, it will be of interest to assess the effects of RgIA4 that are administered over a longer time frame.

The diversity of cone snails and their venom components have provided a rich pharmaceutical cornucopia of neuroactive compounds. Previously, α-conotoxins such as Vc1.1 and RgIA have been characterized to produce anti-pain effects in rodent models of chronic pain, as have been members of the ω-conotoxin family such as MVIIA [28,43]. MVIIA is commercially available as Prialt® (ziconotide) for the treatment of intractable pain and acts by blocking N-type calcium channels in the CNS. Notably, N-type calcium channels may be inhibited by stimulation of γ-aminobutyric acid type-B (GABAB) receptors or µ-opioid receptors [44,45,46]. The stimulation of GABAB receptors has been proposed as the mechanism of action for α-conotoxins Vc1.1 and RgIA [47,48,49,50,51,52]. We note, however, that the RgIA analog used in the present study, RgIA4, does not have GABAB or µ–opioid activity [24,25].

It is noteworthy that the analgesic effects of RgIA4 do not become apparent until the discontinuation of treatment. Previous studies of RgIA and RgIA4 have indicated that full analgesic effects may occur after several weeks of treatment [24,25,26]. This efficacy time course is consistent with a disease-modifying effect that we observed in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain, where RgIA4-treated animals demonstrate anti-allodynic benefits for several weeks after the discontinuation of RgIA4 treatment [24]. This suggests that RgIA4 affects the progression of chronic pain development and recovery, yielding pain relief even after the clearance of RgIA4 from circulation. While neuropathic pain has many different causes, a point of convergence in the progression of disease is neuroinflammation and peripheral nerve damage [2]. α9α10 nAChRs have not been shown to be involved in the neurotransmission of pain. However, these receptors have been shown to be expressed in peripheral immune cells and to affect the release of inflammatory cytokines in vitro and the infiltration of immune cells into perineural spaces following chronic constriction injury (CCI) [28,53,54]. While the exact mechanisms by which α9α10 nAChR antagonists exert their therapeutic effects have yet to be elucidated, it is likely that the long-term neuroprotective effects are, at least in part, influenced by neuroimmune-mediated mechanisms.

Other α9α10 antagonists, structurally unrelated to RgIA4, have also been shown to have analgesic activity in CIPN pain and other neuropathic pain models. Small molecule azaaromatic quaternary ammonium analogs selectively block α9α10 nAChRs [55]. The bis-analog, ZZ1-61c, prevented the development of vincristine-induced neuropathic pain [56]. The tetrakis-quaternary ammonium ZZ-204G was analgesic in formalin and CCI models of neuropathic pain [57]. In addition, an entirely different conotoxin peptide, αO-conotoxin GeXIVA, which blocks α9α10 nAChRs noncompetitively and lacks GABAB agonist activity, also reverses oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain and CCI pain [58,59,60].

Conotoxins may be classified by gene superfamily and defined by their signal sequence in the prepropeptide region and their disulfide framework. The α-conotoxins are members of the A-superfamily, which are characterized as two-disulfide-bridged peptides, typically 13–19 amino acids in length, that selectively and competitively inhibit nAChRs [61]. By contrast, αO-conotoxin GeXIVA is from the O1-superfamily, which are three-disulfide-bridged peptides that typically inhibit voltage-gated ion channels [19]. This diverse group of antagonists supports the idea that α9α10 nAChRs are an effective target for reversing and accelerating recovery from neuropathic pain.

3.2. Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain and Block of α9α10 nAChRs

Chemotherapeutics of the taxane, vinca-alkaloid, and platinum-based families have different mechanisms of action. Paclitaxel is a member of the taxane family and produces a robust anti-cancer effect by stabilizing microtubule polymers, effectively preventing the disassembly and progression of mitosis [62,63,64]. Vinca alkaloids also target microtubules, but in a fashion “opposite” to taxanes, do so by destabilizing microtubule formation [65]. By contrast, platinum-based drugs such as oxaliplatin primarily target DNA, creating DNA lesions and adducts, ultimately preventing cell replication [66]. Just as the mechanisms of action between taxanes, vinca alkaloids, and platinum-based drugs are different, the resulting neuropathologies also develop differently. Taxanes cause dysfunction to mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum calcium signaling as a side effect of their microtubule disruption, whereas platinum-based drugs appear to alter surface ion-channel remodeling initially, and eventually lead to neuronal apoptosis after prolonged exposure [67,68,69]. Vincristine has also been shown to upregulate the surface expression of 5-hydroxytryptamine2A (5-HT2A)receptors in neurons in the dorsal horn and dorsal root ganglion (DRG), sensitizing nociceptors [70]. The development and progression of neuropathies between these three distinct classes of chemotherapeutics are multi-faceted, overlapping in certain aspects, and yet diverse in nature [71].

Painful neuropathies caused by oxaliplatin and paclitaxel share some commonalities of neuronal inflammation, altered ion-channel-expression and excitability of peripheral neurons, and dose-dependent severity [69]. However, while several cellular and molecular markers have been characterized in the development of these distinct neuropathies, the pathophysiology still remains poorly understood [72,73,74]. Previously, RgIA4 showed antinociceptive efficacy in oxaliplatin-treated rats with dosages as low as 0.128 μg/kg, compared to this study where effects did not become evident until 80 μg/kg [24,25]. In addition, RgIA4 showed a robust reversal of cold allodynia in these oxaliplatin models of CIPN. The reason for these differences is unknown. As such, the differential efficacy of RgIA4 in paclitaxel-treated animals, as compared to previously-reported oxaliplatin-treated animals, may provide a pharmacological tool that can help investigate the distinct, yet intertwining, disease progression between these two pathologies.

Despite the different mechanisms of neuropathology caused by distinct anti-cancer drug classes, the blockade of α9α10 nAChRs appears to be a potential convergent target for the prevention and/or treatment of neuropathic pain across several models. Separate from the α9α10 nAChR subtype, the closely-related homomeric α7 nAChR and the α74β2 nAChR subtypes have been implicated in the modulation of pain. Selective activation of α7 nAChRs with (R)-(-)-3-methoxy-1-oxa-2,7-diaza-7,10-ethanospiro[4.5]dec-2-ene sesquifumarate ((R)-ICH3) or PNU-282987, positive allosteric modulation with GAT107 or PNU-120596, and silent agonism with (R)-N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-((pyridin-3-yloxy)methyl)pi-perazine-1-carboxamide Dihydrochloride (R-47) have shown efficacy in models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain [75,76,77,78]. Separately, the α4β2 nAChR agonist (R)-5-(2-azetidinylmethoxy)-2-chloropyridine (ABT-594), an analog inspired by the alkaloid epibatidine isolated from poison arrow frog, Epipedobates tricolor, has been shown to result in robust anti-pain effects [79,80]. ABT-594 moved forward into clinical trials but was halted due to adverse side effects.

While chemotherapies are diverse in their mechanisms of action, several drugs across different families have produced similar neuropathies. The use of natural products as a source of therapeutics has proven to be effective but with caveats. Harnessing the evolutionary refinement of these compounds has provided a rich collection of highly specific pharmacological tools. The discovery of paclitaxel was a fortuitous hit from a concerted screening of natural products coordinated by the United States National Cancer Institute looking specifically for compounds that would be efficacious against cancers [3]. Although one of the most widely used chemotherapeutics, the disruptive side effects of paclitaxel are evident. The use of a cone-snail-derived compound as an effective adjuvant treatment highlights the versatility of natural compounds and the importance of continuing the concerted screening and characterization of these molecules for therapeutic applications. The observed efficacy of α9α10 nAChR antagonists in preventing CIPN pain from taxane, platinum-containing, and vinca-alkaloid families of chemotherapeutics suggests a common juncture in the mechanisms of CIPN development across several structural classes of compounds. RgIA4 may be a promising tool in both the treatment of CIPN pain through this mechanism and further characterization of this non-opioid pathway of pain treatment as a molecular probe.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Envigo) weighing 200–300 g were used in all rat experiments. Rats were housed in groups of two rats per cage with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal colony maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00). Male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used in all mouse experiments. Mice were housed in groups of four or five per cage with food and water available ad libitum and on the same light cycle. All rat studies were conducted under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of New England, protocol number 042617-001. All mice experiments were conducted under the approval of the University of Utah IACUC, protocol number 17-08002. The Animal Care and Use Programs and Facilities of the University of Utah are accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International.

4.2. Drug Solutions and Injections

A clinical formulation of paclitaxel was employed. Paclitaxel USP, extracted from Taxus X media ‘Hicksii’ (Hospira, IL, USA), came in solution at a concentration of 6 mg/mL. The vehicle used for dilution consisted of 1 part 1:1 Cremophore:EtOH mixture and 2 parts 0.9% saline, and 2 mg/mL sodium citrate. Rats were given a dose of 2 mg/kg (IP) every two days for a total of 4 doses, at a volume of 1 mL/kg body weight. RgIA4 was dissolved in 0.9% saline and injected (SC) once per day, 5 days a week for a total of 15 doses at 1 mL/kg body weight for rats and 4 mL/kg body weight for mice [25]. Upon completion of animal injections, material underwent HPLC analysis to verify its composition and integrity.

4.3. Von Frey Assay

Tactile allodynia was quantified by measuring the hindpaw withdrawal threshold to Von Frey filament stimulation, using the up-down method previously reported [81,82]. Throughout the study, experimenters were blinded to the identity of the injected compound. Rats were divided into treatment groups of n = 8 unless otherwise specified. Animals were placed in a clear Plexiglass chamber and allowed to habituate for 15–60 min. Touch-Test filaments (North Coast Medical, Morgan Hill, CA, USA) were used for all testing. For rats, the 2.0 g (4.31) filament was used to start. Clear paw withdrawal, shaking or licking was considered a positive or painful response. This up-down method was stopped four measures after the first positive response. The withdrawal threshold was calculated using the up-down Excel program generously provided by Dr. Michael Ossipov (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA). The filament range for rats was 3.61, 3.84, 4.08, 4.31, 4.56, 4.74, 4.93, 5.18.

4.4. Plantar Test

Thermal allodynia was quantified by measuring the hindpaw withdrawal latency to noxious radiant heat application in unrestrained animals using the plantar test apparatus (rats: Ugo Basile), as previously reported [83]. Throughout the study, experimenters were blinded to the identity of the injected compound. Rats were divided into treatment groups of n = 8 unless otherwise specified. Briefly, animals were placed in a clear Plexiglass chamber and allowed to habituate for 15–60 min. A radiant heat source was then focused on the plantar surface of the hindpaw with the paw withdrawal time automatically determined. The intensity of the heat source was adjusted so that baseline latency was approximately 15 s. A test cutoff time of 30 s was observed to avoid tissue damage.

4.5. Cold Plate

Rats underwent cold plate testing to determine if any sensitivity to cold developed following paclitaxel injection. Throughout the study, experimenters were blinded to the identity of the injected compound. Rats were divided into treatment groups of n = 8 unless otherwise specified. A hot/cold plate (Ugo Basile) was used and cooled to 5 °C. To help achieve reliable results a layer of distilled water coated the cold plate. Each rat was placed on the plate, one at a time. The time it took the rat to lick or flick a hind paw or jump to escape the plate was recorded to the nearest 0.1 s. A 5 min cutoff time was used to remove the rat from the plate if they had not yet shown a response to avoid tissue damage.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

In the rat assays, dose- and time-response curves were constructed for each pain model. Mean and standard errors of the mean were calculated. To determine statistical significance either an unpaired t-test or two-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Bonferroni posttest using GraphPad Prism software version 6.07 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA. Significance was established at the p < 0.05 level.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Doju Yoshikami for helping with the design and assembly of the nerve conduction velocity apparatus and the associated modules made in the LabView software. All rat work was conducted by the University of New England’s COBRE Behavior Core and financially supported by NIGMS (grant number P20GM103643).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CCI | Chronic constriction injury |

| CIPN | Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| nAChR | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| NCV | Nerve conduction velocity |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| SD | Sprague Dawley |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SNAP | Sensory nerve action potential |

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/18/1/12/s1, Figure S1: Paclitaxel did not induce mechanical allodynia in C57BL/6J mice, Figure S2: Tail synaptic nerve action potential (SNAP) conduction velocity was not affected by paclitaxel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, and writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: P.N.H., D.G., K.L.T., S.C., and J.M.M.; formal analysis, investigation, and visualization, P.N.H., D.G., and S.C.; software, P.N.H.; funding acquisition, project administration, and resources, K.L.T. and J.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number R01-GM103801 (JMM); the United States Department of Defense, grant number W81XWH1710413 (JMM); and a National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grant, grant number P20GM103643 (D.G., K.L.T.).

Conflicts of Interest

The University of Utah holds patents on conopeptides including RgIA4 for which J.M.M. is an inventor. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.van Hecke O., Austin S.K., Khan R.A., Smith B.H., Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014;155:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calvo M., Dawes J.M., Bennett D.L.H. The role of the immune system in the generation of neuropathic pain. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:629–642. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cragg G.M. Paclitaxel (Taxol®): A success story with valuable lessons for natural product drug discovery and development. Med. Res. Rev. 1998;18:315–331. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199809)18:5<315::AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seretny M., Currie G.L., Sena E.S., Ramnarine S., Grant R., MacLeod M.R., Colvin L.A., Fallon M. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2014;155:2461–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song S.J., Min J., Suh S.Y., Jung S.H., Hahn H.J., Im S.A., Lee J.Y. Incidence of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy receiving treatment and prescription patterns in patients with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 2017;25:2241–2248. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velasco R., Bruna J. Taxane-Induced Peripheral Neurotoxicity. Toxics. 2015;3:152–169. doi: 10.3390/toxics3020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutertre S., Jin A.H., Vetter I., Hamilton B., Sunagar K., Lavergne V., Dutertre V., Fry B.G., Antunes A., Venter D.J., et al. Evolution of separate predation- and defence-evoked venoms in carnivorous cone snails. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3521. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis R.J., Dutertre S., Vetter I., Christie M.J. Conus venom peptide pharmacology. Pharm. Rev. 2012;64:259–298. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safavi-Hemami H., Gajewiak J., Karanth S., Robinson S.D., Ueberheide B., Douglass A.D., Schlegel A., Imperial J.S., Watkins M., Bandyopadhyay P.K., et al. Specialized insulin is used for chemical warfare by fish-hunting cone snails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1743–1748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423857112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson S.D., Li Q., Bandyopadhyay P.K., Gajewiak J., Yandell M., Papenfuss A.T., Purcell A.W., Norton R.S., Safavi-Hemami H. Hormone-like peptides in the venoms of marine cone snails. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2017;244:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neves J.L., Lin Z., Imperial J.S., Antunes A., Vasconcelos V., Olivera B.M., Schmidt E.W. Small Molecules in the Cone Snail Arsenal. Org. Lett. 2015;17:4933–4935. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutertre S., Jin A.H., Kaas Q., Jones A., Alewood P.F., Lewis R.J. Deep venomics reveals the mechanism for expanded peptide diversity in cone snail venom. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013;12:312–329. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin A.H., Muttenthaler M., Dutertre S., Himaya S.W.A., Kaas Q., Craik D.J., Lewis R.J., Alewood P.F. Conotoxins: Chemistry and Biology. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:11510–11549. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennington M.W., Czerwinski A., Norton R.S. Peptide therapeutics from venom: Current status and potential. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:2738–2758. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao B., Peng C., Yang J., Yi Y., Zhang J., Shi Q. Cone Snails: A Big Store of Conotoxins for Novel Drug Discovery. Toxins. 2017;9:397. doi: 10.3390/toxins9120397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giribaldi J., Dutertre S. α-Conotoxins to explore the molecular, physiological and pathophysiological functions of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;679:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green B.R., Bulaj G., Norton R.S. Structure and function of mu-conotoxins, peptide-based sodium channel blockers with analgesic activity. Future Med. Chem. 2014;6:1677–1698. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIntosh J.M., Jones R.M. Cone venom—From accidental stings to deliberate injection. Toxicon. 2001;39:1447–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson S.D., Norton R.S. Conotoxin gene superfamilies. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:6058–6101. doi: 10.3390/md12126058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivera B.M., Quik M., Vincler M., McIntosh J.M. Subtype-selective conopeptides targeted to nicotinic receptors: Concerted discovery and biomedical applications. Channels. 2008;2:143–152. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.2.6276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellison M., Feng Z.P., Park A.J., Zhang X., Olivera B.M., McIntosh J.M., Norton R.S. α-RgIA, a novel conotoxin that blocks the α9α10 nAChR: Structure and identification of key receptor-binding residues. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:1216–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellison M., Haberlandt C., Gomez-Casati M.E., Watkins M., Elgoyhen A.B., McIntosh J.M., Olivera B.M. α-RgIA: A novel conotoxin that specifically and potently blocks the α9α10 nAChR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1511–1517. doi: 10.1021/bi0520129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azam L., Papakyriakou A., Zouridakis M., Giastas P., Tzartos S.J., McIntosh J.M. Molecular interaction of α-conotoxin RgIA with the rat α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharm. 2015;87:855–864. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen S.B., Hone A.J., Roux I., Kniazeff J., Pin J.P., Upert G., Servent D., Glowatzki E., McIntosh J.M. RgIA4 Potently Blocks Mouse α9α10 nAChRs and Provides Long Lasting Protection against Oxaliplatin-Induced Cold Allodynia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017;11:219. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero H.K., Christensen S.B., Di Cesare Mannelli L., Gajewiak J., Ramachandra R., Elmslie K.S., Vetter D.E., Ghelardini C., Iadonato S.P., Mercado J.L., et al. Inhibition of α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors prevents chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E1825–E1832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621433114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Cesare Mannelli L., Cinci L., Micheli L., Zanardelli M., Pacini A., McIntosh J.M., Ghelardini C. α-conotoxin RgIA protects against the development of nerve injury-induced chronic pain and prevents both neuronal and glial derangement. Pain®. 2014;155:1986–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacini A., Micheli L., Maresca M., Branca J.J., McIntosh J.M., Ghelardini C., Di Cesare Mannelli L. The α9α10 nicotinic receptor antagonist α-conotoxin RgIA prevents neuropathic pain induced by oxaliplatin treatment. Exp. Neurol. 2016;282:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vincler M., Wittenauer S., Parker R., Ellison M., Olivera B.M., McIntosh J.M. Molecular mechanism for analgesia involving specific antagonism of α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17880–17884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608715103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hone A.J., McIntosh J.M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in neuropathic and inflammatory pain. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:1045–1062. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrot M. Tests and models of nociception and pain in rodents. Neuroscience. 2012;211:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths L.A., Duggett N.A., Pitcher A.L., Flatters S.J.L. Evoked and Ongoing Pain-Like Behaviours in a Rat Model of Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Pain Res. Manag. 2018;2018:8217613. doi: 10.1155/2018/8217613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith S.B., Crager S.E., Mogil J.S. Paclitaxel-induced neuropathic hypersensitivity in mice: Responses in 10 inbred mouse strains. Life Sci. 2004;74:2593–2604. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makker P.G., Duffy S.S., Lees J.G., Perera C.J., Tonkin R.S., Butovsky O., Park S.B., Goldstein D., Moalem-Taylor G. Characterisation of Immune and Neuroinflammatory Changes Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmiroli P., Riva B., Pozzi E., Ballarini E., Lim D., Chiorazzi A., Meregalli C., Distasi C., Renn C.L., Semperboni S., et al. Susceptibility of different mouse strains to oxaliplatin peripheral neurotoxicity: Phenotypic and genotypic insights. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chua K.C., Kroetz D.L. Genetic advances uncover mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clin Pharm. Ther. 2017;101:450–452. doi: 10.1002/cpt.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park S.B., Lin C.S., Krishnan A.V., Goldstein D., Friedlander M.L., Kiernan M.C. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity: Changes in axonal excitability precede development of neuropathy. Brain. 2009;132:2712–2723. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sittl R., Lampert A., Huth T., Schuy E.T., Link A.S., Fleckenstein J., Alzheimer C., Grafe P., Carr R.W. Anticancer drug oxaliplatin induces acute cooling-aggravated neuropathy via sodium channel subtype Na(V)1.6-resurgent and persistent current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6704–6709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118058109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Augusto C., Pietro M., Cinzia M., Sergio C., Sara C., Luca G., Scaioli V. Peripheral neuropathy due to paclitaxel: Study of the temporal relationships between the therapeutic schedule and the clinical quantitative score (QST) and comparison with neurophysiological findings. J. Neurooncol. 2008;86:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alushin G.M., Lander G.C., Kellogg E.H., Zhang R., Baker D., Nogales E. High-resolution microtubule structures reveal the structural transitions in αβ-tubulin upon GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 2014;157:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandos H., Melnikow J., Rivera D.R., Swain S.M., Sturtz K., Fehrenbacher L., Wade J.L., III, Brufsky A.M., Julian T.B., Margolese R.G., et al. Long-term Peripheral Neuropathy in Breast Cancer Patients Treated With Adjuvant Chemotherapy: NRG Oncology/NSABP B-30. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018;110:djx162. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivera D.R., Ganz P.A., Weyrich M.S., Bandos H., Melnikow J. Chemotherapy-Associated Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients With Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018;110:djx140. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Bent M.J., van Raaij-van den Aarssen V.J., Verweij J., Doorn P.A., Sillevis Smitt P.A. Progression of paclitaxel-induced neuropathy following discontinuation of treatment. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:750–752. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199706)20:6<750::AID-MUS15>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satkunanathan N., Livett B., Gayler K., Sandall D., Down J., Khalil Z. Alpha-conotoxin Vc1.1 alleviates neuropathic pain and accelerates functional recovery of injured neurones. Brain Res. 2005;1059:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrade A., Denome S., Jiang Y.Q., Marangoudakis S., Lipscombe D. Opioid inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels and spinal analgesia couple to alternative splicing. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1249–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seward E., Hammond C., Henderson G. Mu-opioid-receptor-mediated inhibition of the N-type calcium-channel current. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1991;244:129–135. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tedford H.W., Zamponi G.W. Direct G protein modulation of Cav2 calcium channels. Pharm. Rev. 2006;58:837–862. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berecki G., McArthur J.R., Cuny H., Clark R.J., Adams D.J. Differential Cav2.1 and Cav2.3 channel inhibition by baclofen and α-conotoxin Vc1.1 via GABAB receptor activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014;143:465–479. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callaghan B., Haythornthwaite A., Berecki G., Clark R.J., Craik D.J., Adams D.J. Analgesic α-conotoxins Vc1.1 and Rg1A inhibit N-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons via GABAB receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10943–10951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3594-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castro J., Harrington A.M., Garcia-Caraballo S., Maddern J., Grundy L., Zhang J., Page G., Miller P.E., Craik D.J., Adams D.J., et al. α-Conotoxin Vc1.1 inhibits human dorsal root ganglion neuroexcitability and mouse colonic nociception via GABAB receptors. Gut. 2017;66:1083–1094. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huynh T.G., Cuny H., Slesinger P.A., Adams D.J. Novel mechanism of voltage-gated N-type (Cav2.2) calcium channel inhibition revealed through α-conotoxin Vc1.1 activation of the GABA(B) receptor. Mol. Pharm. 2015;87:240–250. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohammadi S., Christie M.J. α9-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors contribute to the maintenance of chronic mechanical hyperalgesia, but not thermal or mechanical allodynia. Mol. Pain. 2014;10:64. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohammadi S.A., Christie M.J. Conotoxin Interactions with α9α10-nAChRs: Is the α9α10-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor an Important Therapeutic Target for Pain Management? Toxins. 2015;7:3916–3932. doi: 10.3390/toxins7103916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng H., Ferris R.L., Matthews T., Hiel H., Lopez-Albaitero A., Lustig L.R. Characterization of the human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha (α) 9 (CHRNA9) and alpha (α) 10 (CHRNA10) in lymphocytes. Life Sci. 2004;76:263–280. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richter K., Mathes V., Fronius M., Althaus M., Hecker A., Krasteva-Christ G., Padberg W., Hone A.J., McIntosh J.M., Zakrzewicz A., et al. Phosphocholine—An agonist of metabotropic but not of ionotropic functions of α9-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28660. doi: 10.1038/srep28660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng G., Zhang Z., Dowell C., Wala E., Dwoskin L.P., Holtman J.R., McIntosh J.M., Crooks P.A. Discovery of non-peptide, small molecule antagonists of α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as novel analgesics for the treatment of neuropathic and tonic inflammatory pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2476–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wala E.P., Crooks P.A., McIntosh J.M., Holtman J.R., Jr. Novel small molecule α9α10 nicotinic receptor antagonist prevents and reverses chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain in rats. Anesth. Analg. 2012;115:713–720. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825a3c72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holtman J.R., Dwoskin L.P., Dowell C., Wala E.P., Zhang Z., Crooks P.A., McIntosh J.M. The novel small molecule α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist ZZ-204G is analgesic. Eur. J. Pharm. 2011;670:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X., Hu Y., Wu Y., Huang Y., Yu S., Ding Q., Zhangsun D., Luo S. Anti-hypersensitive effect of intramuscular administration of αO-conotoxin GeXIVA[1,2] and GeXIVA[1,4] in rats of neuropathic pain. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;66:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo S., Zhangsun D., Harvey P.J., Kaas Q., Wu Y., Zhu X., Hu Y., Li X., Tsetlin V.I., Christensen S., et al. Cloning, synthesis, and characterization of αO-conotoxin GeXIVA, a potent α9α10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E4026–E4035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503617112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang H., Li X., Zhangsun D., Yu G., Su R., Luo S. The α9α10 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonist αO-Conotoxin GeXIVA[1,2] Alleviates and Reverses Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:265. doi: 10.3390/md17050265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos A.D., McIntosh J.M., Hillyard D.R., Cruz L.J., Olivera B.M. The A-superfamily of conotoxins: Structural and functional divergence. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17596–17606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jordan M.A., Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pazdur R., Kudelka A.P., Kavanagh J.J., Cohen P.R., Raber M.N. The taxoids: Paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere) Cancer Treat. Rev. 1993;19:351–386. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(93)90010-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tangutur A.D., Kumar D., Krishna K.V., Kantevari S. Microtubule Targeting Agents as Cancer Chemotherapeutics: An Overview of Molecular Hybrids as Stabilizing and Destabilizing Agents. Curr. Top Med. Chem. 2017;17:2523–2537. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170104145640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jordan M. Mechanism of Action of Antitumor Drugs that Interact with Microtubules and Tubulin. Curr. Med. Chem. Anti-Cancer Agents. 2012;2:1–17. doi: 10.2174/1568011023354290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raymond E., Faivre S., Chaney S., Woynarowski J., Cvitkovic E. Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology of Oxalipaltin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brewer J.R., Morrison G., Dolan M.E., Fleming G.F. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: Current status and progress. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016;140:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Descoeur J., Pereira V., Pizzoccaro A., Francois A., Ling B., Maffre V., Couette B., Busserolles J., Courteix C., Noel J., et al. Oxaliplatin-induced cold hypersensitivity is due to remodelling of ion channel expression in nociceptors. EMBO Mol. Med. 2011;3:266–278. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zajaczkowska R., Kocot-Kepska M., Leppert W., Wrzosek A., Mika J., Wordliczek J. Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1451. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thibault K., Van Steenwinckel J., Brisorgueil M.J., Fischer J., Hamon M., Calvino B., Conrath M. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor involvement and Fos expression at the spinal level in vincristine-induced neuropathy in the rat. Pain. 2008;140:305–322. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jaggi A.S., Singh N. Mechanisms in cancer-chemotherapeutic drugs-induced peripheral neuropathy. Toxicol. 2012;291:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flatters S.J.L., Dougherty P.M., Colvin L.A. Clinical and preclinical perspectives on Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN): A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017;119:737–749. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Starobova H., Vetter I. Pathophysiology of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:174. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dougherty P.M., Cata J.P., Cordella J.V., Burton A., Weng H.R. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain. 2004;109:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bagdas D., Wilkerson J.L., Kulkarni A., Toma W., AlSharari S., Gul Z., Lichtman A.H., Papke R.L., Thakur G.A., Damaj M.I. The α7 nicotinic receptor dual allosteric agonist and positive allosteric modulator GAT107 reverses nociception in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharm. 2016;173:2506–2520. doi: 10.1111/bph.13528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Damaj M.I., Meyer E.M., Martin B.R. The antinociceptive effects of α7 nicotinic agonists in an acute pain model. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2785–2791. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(00)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freitas K., Ghosh S., Ivy Carroll F., Lichtman A.H., Imad Damaj M. Effects of α7 positive allosteric modulators in murine inflammatory and chronic neuropathic pain models. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toma W., Kyte S.L., Bagdas D., Jackson A., Meade J.A., Rahman F., Chen Z.J., Del Fabbro E., Cantwell L., Kulkarni A., et al. The α7 nicotinic receptor silent agonist R-47 prevents and reverses paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice without tolerance or altering nicotine reward and withdrawal. Exp. Neurol. 2019;320:113010. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Di Cesare Mannelli L., Pacini A., Matera C., Zanardelli M., Mello T., De Amici M., Dallanoce C., Ghelardini C. Involvement of α7 nAChR subtype in rat oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: Effects of selective activation. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rowbotham M.C., Duan W.R., Thomas J., Nothaft W., Backonja M.M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ABT-594 in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2009;146:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chaplan S.R., Bach F.W., Pogrel J.W., Chung J.M., Yaksh T.L. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dixon W.J. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu. Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 1980;20:441–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hargreaves K., Dubner R., Brown F., Flores C., Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.