Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to illuminate nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion to patients in the home care context.

Design

A phenomenological–hermeneutical approach was used.

Methods

The data comprised of texts from interviews with 12 nurses in a home care context. Informed consent was sought from participants regarding participation in the study and the storage and handling of data for research purposes.

Results

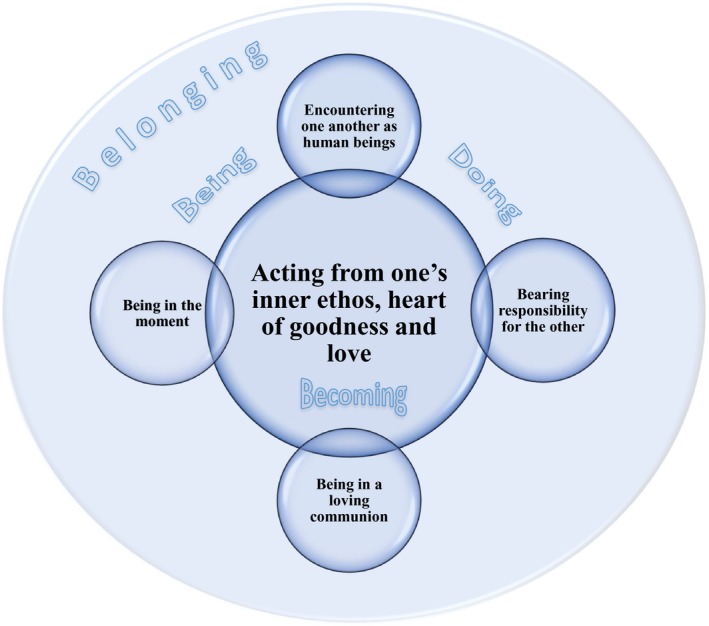

Four themes were seen: Encountering one another as human beings, Being in the moment, Bearing responsibility for the other and Being in a loving communion. The overall theme was Acting from one's inner ethos, heart of goodness and love. Mediating compassion as belonging can be interpreted as the “component” that holds the caring relationship together and unites the different levels of health as doing, being and becoming in the ontological health model. Further research should focus on revealing compassion from the perspective of patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

In this study, we focused on the phenomenon of compassion, which can be seen as the heart of caring (Chambers & Ryder, 2009, 2012). Compassion is also considered to be the basis for ethical codes in nursing (Tehranineshat, Rakhshan, Torabizadeh, & Fararouei, 2018) and is one of the five values required of a professional nurse (International Council of Nurses, 2012). In the American Nurses Association's Code of Ethics for Nurses (2015), to uphold the inherent dignity of each person, nurses should practice with compassion and respect. Compassion is perceived to be a fundamental aspect of caring and described as the “capacity to bear witness to, suffer with and hold dear within our heart the sorrow and beauties of the world” (Watson, 2008, p. 78). Compassion may be nursing's most vital and precious asset (Burnell, 2009; Cornwell, Donaldson, & Smith, 2014), but is poorly defined in current nursing literature (Adamson & Dewar, 2015; Dewar, Adamson, Smith, Surfleet, & King, 2014; Kenny, 2016; McCaffrey & McConnell, 2015). Still, compassion has recently emerged as a growing topic of interest in nursing literature (Bramley & Matiti, 2014; Brito‐Pons & Librada‐Flores, 2018; Department of Health & NHS Commissioning Board, 2012; McCaffrey & McConnell, 2015; Sinclair et al., 2018; Sinclair, McClement, et al., 2016a; Sinclair, Norris, et al., 2016b; Zamanzadeh, Valizadeh, Rahmani, Cingel, & Ghafourifard, 2018).

2. BACKGROUND

Compassion is a core concept in nursing (Chambers & Ryder, 2009) and caring science (Eriksson, 2006). In research, compassion is described as a complex and multifaceted psychological and social process part of human nature (Gilbert, 2009) and deeply relational (Sinclair, Norris, et al., 2016b; Spandler & Stickley, 2011). Different attributes such as sensitivity, dignity and respect (Chambers & Ryder, 2009), listening and responding (Chambers & Ryder, 2009; van der Cingel, 2011), attentiveness, confronting, involvement, helping, presence and understanding (van der Cingel, 2011) and genuine connection (Burnell, 2009) have been associated with compassion. Compassion is also perceived to be a virtue that should be cultivated as an aspect of individual character (Bradshaw, 2009; Burnell, 2009; Jull, 2001; McCaffrey & McConnell, 2015; Schantz, 2007; von Dietze & Orb, 2000). In the Oxford English Dictionary (1989), compassion is defined as: (1) Suffering together with another, participation in suffering; fellow‐feeling, empathy; (2) The feeling of emotion, when a person is moved by the suffering or distress of another; (3) Sorrowful emotion, sorrow, grief. Compassion entails a deep awareness of and strong willingness to try to relieve others’ suffering (Chochinov, 2007; Gilbert, 2009; Jull, 2001; Schantz, 2007; Sinclair, Norris, et al., 2016b), an active empathic presence from others and an understanding and appreciation of a person's unique way of being in the world (Spandler & Stickley, 2011). Compassion is related to the ethical aspects of nursing care and nurses’ virtuous response to the suffering of others (Frampton, Guastello, & Lepore, 2013; Sinclair et al., 2018; Sinclair, Norris, et al., 2016b). Compassion can be understood as a moral virtue, where the expression of compassion requires action from the compassionate individual. Not only can compassion be cultivated as a virtue (Saunders, 2015), but the characteristics of one's early childhood care also influence one's development of compassion, even into adult life (Gluschkoff et al., 2018). In a study where dispositional compassion was self‐reported, researchers found that individuals who attended centre‐based care at an early age had a higher degree of compassion in later life (Gluschkoff et al., 2018). For nurses, expressing compassion includes mediating compassion to patients and providing a deep response to others’ suffering (Jull, 2001). Consequently, compassion in care can be considered an essential process through which nurses and patients are motivated and empowered to cooperate to achieve relevant care outcomes (Dewar & Cook, 2014).

Saunders (2015) underscores that compassion is the missing component in care and failures in providing compassion in care were seen in reports by the Health Service Ombudsman in England (Health Service Commissioner for England, 2011) and the Care Quality Commission (2011). Hassmiller (2018) maintains that not only compassion but also heart, as unique nursing contributions, are neglected and should be brought to the forefront of care. McCaffrey and McConnell (2015) highlight that the influence of institutional environments can facilitate or limit the expression of compassion. Godlaski (2015) states that care professionals’ perspectives on the role of compassion are lacking and questions whether researchers view compassion as being “unscientific” or difficult to measure. Jakimowicz, Perry, and Lewis (2017) maintain that few studies have concentrated on exploring compassion from nurses’ perspectives, finding that compassion satisfaction (vs. compassion fatigue) among intensive care nurses can be improved through patient‐centred nursing. Other researchers note that patients’ perspectives on compassion in care have been explored in only a few studies (Bramley & Matiti, 2014; Sinclair, McClement, et al., 2016a).

Compassion is also seen to be a crucial element for alleviating suffering among patients in home care (Ebenstein, 1998). Saunders (2015) notes that more research on the elements that contribute to care professionals’ compassion is needed, because the true meaning of compassion is seldom explored: the assumption exists that what compassion means is understood and it is (assumed to be) a good thing. To our knowledge, research including a focus on nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion is sparse, which is why we chose to investigate this particular context.

2.1. Research question

What are nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion to patients in the home care context?

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework is based on Eriksson's theory of caritative caring (Eriksson, 2007; Lindström, Nyström, & Zetterlund, 2018) and on Watson's philosophy and theory of transpersonal caring (Willis & Leone‐Sheehan, 2018). In caritative theory, the human being is the centre of nursing care and should therefore be treated with dignity (Eriksson, 2007; Lindström et al., 2018). From a caring science perspective, the patient's suffering can be alleviated in a caring relationship where the nurse views each patient as a unique human being and strives to preserve the patient's dignity despite suffering (Eriksson, 2006). In caring, compassion is considered profound and pivotal to the alleviation of the patient's suffering. Acknowledging suffering is also a “message” that one is available for the other.

Compassion can also be understood in relation to what Watson (2005a) describes as the ethics of belonging before being. Referencing Levinas (2000), Watson maintains that belonging, that is, our connectedness to others, precedes our separate ontology of being and thus our rational–intellectual worldly endeavours. Through belonging, we are enabled to bring caring and love together in a field of reverence and dwelling in infinity (Watson, 2005b). Using the metaphors “holding another's life in our hands” and “ethics of face,” Watson (2003) argues that it is perhaps love that underpins and connects human beings with one another, reminding us of another dimension through which we can sustain our humanity at a deeper level.

3.2. Design and method

A phenomenological–hermeneutical approach developed by Lindseth and Norberg (2004) in accordance with Ricoeur’s (1991) philosophy was used. The data were comprised of texts from interviews with 12 nurses about their experiences of views on mediating compassion to patients in the home care context. The data material consisted of texts from interviews with 12 Finnish nurses (age range 23–64) about their experiences of what compassion means and how compassion is mediated to patients in the home care context. Nurses (11 females and 1 male, age 23–64) were recruited in collaboration with head nurses from various home care contexts: two public care organizations and one private home care organization. The participants came from both urban and rural areas in Finland, but all had the same socioeconomic background. They had between 1–43 years of experience in different nursing contexts: primarily home care but also hospital care, for example, cancer care.

The interviews, lasting between 60–90 min, were conducted in 2018 in Swedish at Åbo Akademi university where the first author worked or at the offices of the care organizations where the participants worked. To maintain privacy, most interviews were conducted in an undisturbed environment. All interviews were transcribed by the first researcher and subject to a phenomenological–hermeneutical analysis comprising three interpretive steps (Lindseth & Norberg, 2004).

3.3. Analysis

In the first interpretative step of the phenomenological–hermeneutical analysis, both researchers independently read all the transcribed interview material, whereafter they individually each formulated a first naïve understanding of the meaning of the text as a whole. The researchers then together discussed and came to consensus on a final version of the naïve understanding. In the second interpretive step, structural analysis occurred when the researchers first independently divided the text into meaning units and then together discussed and came to consensus on a final version of the meaning units. Afterwards, the meaning units were condensed and abstracted into subthemes and themes. In the third and final step, the interpreted whole, the researchers together reflected on the themes in relation to the naïve understanding and the theoretical framework until a main theme emerged, through which a new possible understanding of compassion as an ontological phenomenon was revealed. To facilitate transparency in the interpretive process, the presentation of findings below is structured in accordance with the methodological approach. As this study aims at illuminating nurses’ experiences formulations about how compassion might affect patients are made from the nurses’ perspective rather than describing “how it is.”

3.4. Ethics

Ethical permission to conduct the study was granted from the three organizations were the participants were recruited. During the recruitment process, willingness to participate in the study was indicated when potential participants stated that their names could be forwarded to the researchers conducting this study. Those selected for participation were contacted personally by one of the researchers via an initial phone call. Afterwards, the participants also received a detailed email including all information about the study: study purpose, confidentiality, withdrawal of consent and intent to publish. Informed consent regarding participation in the study and the storage and handling of data for research purposes was also sought. The Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics (2012) granted approval for the study, and its guidelines for ethical research were followed throughout the course of the study.

4. RESULTS

Mediating compassion to patients in the home care context can be understood as acting from one's heart and having the courage to be present for the other in a trustful caring relationship.

4.1. Naïve understanding

Mediating compassion to patients in a home care context can be understood as acting from one's heart and having the courage to be present for the other in a trustful caring relationship.

4.2. Structural analysis

We sought to reveal how compassion can be mediated in the caring relationship. The thematic, structural analysis resulted in four themes and ten subthemes. The themes were as follows: Encountering one another as human beings; Being in the moment; Bearing responsibility for the other; and Being in a loving communion. The themes and their content are delineated below, with the subthemes indicated by italics. All describe nurses’ perceptions of the subject matter.

4.2.1. Encountering one another as human beings

In this theme, the nurse acts in an honest and humble way and treats the patient with dignity by indicating that the patient is at the centre of the caring relationship, which is essential for mediating compassion. Encountering one another as human beings entails to show genuine interest so that trust may be created with the patient as a basis for mediating compassion. One way of showing interest is to use nonverbal expressions:

I make eye contact I look them in the eyes so that they can see an honest look and that [I am] humble… they can decide how they want it…everything is on their terms. (P6)

Encountering one another as human beings as a basis for mediating compassion also entails to be honest and natural. The nurse can do this by being present and “there” for the patient without selfish demands. Such, in turn, can generate possibilities for the establishment of fundamental trust, where the patient perceives the nurse to be reliable. Trust is the basis on which compassion can be mediated. According to the participants, the patient is aware of whether nurses are natural and honest in their being. Trust can evolve as a consequence of nurses being reliable and faithful. Encountering one another as human beings even includes to enhance the patient's dignity:

Definitely… [nurses have to place themselves on a lower level than the patient] since I am a guest in the patients’ home. I come there on their terms. And then I see what we can do together… Everything has to be according to the wishes of the patient. If I don’t work that way… then there will be no compassion… (P7)

By sitting down and being calm, for example, the nurse communicates that he/she intends to humbly listen to the patient and that the patient is worth investing time and engagement in.

4.2.2. Being in the moment

In this theme, the nurse acts in a manner that allows them to “be” in the moment with the patient, which is fundamental for mediating compassion. Being in the moment entails to have the courage to be present, where the nurse creates a space for the patient to express his/her suffering. The participants nonetheless noted that not all patients are able to express their suffering in words. Therefore, the nurses not only mediate compassion in response to a patient's narratives but also through being together in silence. Nurses sometimes need to “sit on their hands,” that is, refrain from acting, rather than performing different tasks. The participants perceived that being impatient and starting to perform different tasks was a threat to the patient's dignity, because through such the patient could experience that he/she was not important. One participant stated that “being out of the moment” and acting rather than “being in the moment” and waiting in silence could reawaken a patient's suffering and “shut [the relationship] down [snaps her fingers]… just like that.” (P6).

Being in the moment as a basis for mediating compassion also entails to be close to someone. The participants considered such closeness to be a means to communicate to the patient that they as nurses were present, available and willing to share the suffering of the other:

When we sit close some kind of tension arises… and I think that I’m open to receive [whatever the person may wish to open up about] and [compassion] opens a way to it. (P2)

As revealed above, closeness does not merely include physical closeness, but also being emotionally close in a way that can create space for patients to express their suffering. Being in the moment as a basis for mediating compassion consequently entails demonstrating that one is available for the other and willing to approach that which might be painful both to bear and share.

4.2.3. Bearing responsibility for the other

In this theme, the nurse needs to have a natural willingness to care for and to be responsive to the patient, as a basis for mediating compassion. This entails that nurses, for example, should be aware of the patient's surroundings and life situation, including the patient's next of kin. Nurses can get to know the patient by talking about non‐patient‐related things that the patient is interested in, that is to say they can implement person‐centred nursing. Bearing responsibility for the other is based on an inner natural care for the fellow human being who is suffering:

If one wants to see… if one wants to hear. And if one wants to help. Then there is no problem. …One has to be perceptive to the matter. Because I will not perceive it if I do not want to. (P10)

Bearing responsibility for the other as a basis for mediating compassion also entails to not abandon. This implies that nurses continue to be the patient's supportive fellow human being, which is dependent on nurses’ ability to understand and demonstrate compassion so that a sense of personal security can be mediated to the patient:

My task is to coax them to rise above the darkness in the valley… And first and foremost to help them reach higher. But also that I walk with them on the journey down… …and when there are setbacks and it goes downhill, then this same security [me, the nurse] follows along… often when they get bad news, then I am this security [that does not abandon], but still remains stable [although everything else changes]. (P10)

4.2.4. Being in a loving communion

In this theme, mediating compassion is considered to be a matter of sharing, not only the other's suffering but one's own vulnerability and through communion nurses can embrace this duality. Being in a loving communion allows nurses to share suffering, which is a way to “be with” and “be for” the other in a way that is also perceived as supportive:

I believe that they receive strength from me… and that they are not alone … It is a communion… I mediate that ‘I am here with you’… (P10)

Being in a loving communion as a basis for mediating compassion also entails to share one's own vulnerability. Thus, mediating compassion also involves that nurses share something about themselves, for example, expressions of being touched by the other's suffering. To be oneself as a fellow human being and reveal that one is not without fault requires not only courage but also vulnerability:

Yes, precisely… [the tears of the nurse can show the patient] that one is a human being…and that also enables even the toughest ones to be allowed to be vulnerable together with me. Because they see that I am also vulnerable, so they too may have the courage to show themselves [as being] vulnerable. (P6)

4.3. Interpreted whole

The interpreted whole can be understood as a synthesis of the naïve understanding, the findings from the structural analysis and the theoretical frame of reference. Encountering one another as human beings and Being in the moment were crucial for mediating compassion. Intertwined with Bearing responsibility for the other and Being in a loving communion, an overall theme emerged where nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion in the home care context could be understood as, “Acting from one's inner ethos, heart of goodness and love.” The profound ethos and focus on the other seen here also revealed that mediating compassion not only pertains to suffering alongside the patient while striving to alleviate the patient's suffering, but also ensuring the patient's dignity. The overall theme can be compared to Watson (2005b) theory of belonging before being, where all humans are placed in a shared universal field of infinite love, where love and caring are united in a deep human‐to‐human connection. Extrapolating thus, having a true willingness to care, for example, is based on the experience of a shared belonging (Watson, 2005b), expressed as a wish not only to understand but also to respond to what the patient expresses (cf. Watson, 2005b). Mediating compassion as belonging (cf. Watson, 2005b) can therefore be interpreted as the “component” that holds the caring relationship together and which unites the different levels of health as doing, being and becoming, in accordance with Eriksson's ontological health model (Lindström et al., 2018) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study findings: mediating compassion

Nurses mediate compassion when they are present and share a moment with a patient by “being” (e.g., sitting a beside patient or holding a patient's hand), which can help the patient find the courage to also be in the moment. The dignity of the patient is also confirmed when nurses are there for a patient in an honest and humble way and wait in silence, which involves both physical and emotional closeness. Nurses can violate a patient's dignity if they engage in immediate action in an attempt to avoid being touched by the suffering of the other or if they display powerlessness during difficult moments, because patients can through such actions perceive that they are not allowed to reveal suffering or may perceive that expressions of suffering need to be immediately “fixed” (cf. Eriksson, 2006). By being in and sharing the moment of suffering and vulnerability, nurses can create space whereby patients can approach their own vulnerability and acknowledge and approach their suffering in a new way. When suffering is shared and vulnerability reciprocated, both the nurse and patient can experience a becoming in relation to life and health. Such closeness also facilitates nurses in mediating compassion through doing, because this enables nurses to engage in compassionate actions that relieve suffering and thereby offer patients a respite (if only for a moment) from suffering (cf. Hemberg, 2015). By mediating compassion not only through action but also as an expression of shared humanity, nurses enable patients to perceive nurses’ expressions of compassion as expressions of love and concern rather than “pity.”

5. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to illuminate nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion to patients in the home care context. We found that the basis for mediating compassion is when nurses act from their inner ethos, heart of goodness and love, actions that originate in belonging, a deep human‐to‐human connection between nurse and patient (cf. Watson, 2005b; Wiklund Gustin & Wagner, 2013). This is in line with earlier research where compassion was identified as a virtue (Bradshaw, 2009; Burnell, 2009; Jull, 2001; McCaffrey & McConnell, 2015; Schantz, 2007; von Dietze & Orb, 2000). Here, we have not focused on understanding compassion but have instead focused on understanding nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion, in contrast to earlier research. Consequently, through this study we have been able to add new insight into what it means to be compassionate and therefore also the meaning of compassionate care.

As seen here, compassionate care is not only a matter of nurses getting to know each patient as a human being. It is also about nurses making themselves available in a way that provides a foundation for a reciprocal nurse–patient relationship, transcending the asymmetry of the care relationship where one person is dependent on the good will and professionalism of the other. This is in line with the personal bond described by Sundin and Jansson (2003), which can be understood as supporting the patient in the struggle with suffering (Eriksson, 2006). In line with this, Godlaski (2015) states that compassion is in many ways more akin to friendship than anything else. He notes that while such a view might be unfamiliar or even construed as being unsafe when considered in a professional health context, the difference between the two lies in that compassion occurs on the professional level while such friendship (i.e., what others consider compassion) occurs not so much on the personal level as on the professional level. Godlaski (2015) continues, writing that: “The compassionate clinician is much like a professional friend who helps us live through and talk through the experiences of illness, suffering, loss and grief, all the while making his compassion evident” (p. 944). Also, Pellegrino and Thomasma (1993) maintain that professionals (viewed as a professional friend) have a lot of helpful knowledge and experience, which “non‐professional” friends typically lack. Godlaski (2015) argues that the meaning of care is to grieve, that is, to experience sorrow or pain and cry out with another individual. He also claims that compassion is not actually something one does, but rather something that the suffering of another individual brings out in one, stating that: “She and I are linked in a kind of moral dance where no one is leading and no one is being led” (Godlaski, 2015, p. 946). According to Young‐Mason (1994), connectedness is absolutely vital for compassion and by being compassionate an individual learns something more about the vulnerability of being human. Such learning informs the imaginative understanding necessary for a person's understanding and “self‐transposal” into another's situation (Jull, 2001; Pence, 1983). As Jull (2001) notes, compassion requires action from the compassionate. Nevertheless, we found here that the most profound compassionate action might be to be in the moment and refrain from acting, giving instead one's time and presence in the moment to the other.

We found that mediating compassion is an act of love, courage and goodness. This can be compared to Numminen, Repo, and Leino‐Kilpi’s (2017), Arman & Hök (2007), Lindwall, Bouissad, Kulzer, and Wigerblad (2012) and Thorup, Rundqvist, Roberts, and Delmar (2012) thoughts on moral courage in care being realized through engagement and manifested as love and compassion. We also saw that mediating compassion requires nurses to be willing to bear responsibility for the other, not only as a patient but also as a fellow human being. This is furthermore reflected in the finding here that nurses should care from their hearts. We question whether nurses today have the sufficient time to or the understanding that they should focus on their willingness to care for each patient with compassion and as a human being, rather than focusing on their duty of care and responsibility for patients’ “obvious” and visible/tangible needs. To remedy this situation, a greater focus should be placed on nurses’ compassion competence and not solely practical and technical nursing skills during nursing education. Bray, O’Brien, Kirton, Zubairu, and Christiansen (2014) state that education is essential for developing compassionate caregivers and enhancing compassionate care delivery, while Lown (2014) maintains that teaching compassion is vital to fostering compassionate care in healthcare organizations. With regard to teaching compassion, researchers have found that compassionate care delivery is best taught through role models (Straughair, 2012a, 2012b).

We even saw that silence, closeness and a humble approach are vital for mediating compassion. Being in silent connectedness enables nurses’ understanding of the other (cf. Sundin & Jansson, 2003) and can be compared to the kind of intuitive knowing described by van der Cingel (2014). Care based on intuitive knowledge entails nurses waiting for patients and being present, available and prepared to face the darkness and suffering in the present moment (cf.; Hemberg, 2017; van der Cingel, 2011, 2014). Saunders (2015) notes that, “Compassion belongs at the patient's bedside or sick room, not in the office of the public health physician or epidemiologist” (p. 122). Saunders also states that sympathy is not to be confused with compassion, because sympathy is too weak for the serious states and conditions where compassion is suitable and needed. More than good manners, compassion requires time and occasionally requires silence, that is, waiting and a sense of mutuality (Saunders, 2015). We maintain that the ability and courage to be in silent connectedness with patients, seen here as being present and together in silence, can be challenging for some nurses, especially novice nurses, given that such skills are more easily acquired through work and life experience. Being in silent connectedness with patients and refraining from acting to mediate compassion should be emphasized and practised during clinical nursing education and time should be given for reflection and discussion on such actions’ associated outcomes in nursing educational programmes.

By understanding mediating compassion as an aspect of mutuality and belonging, one can also shed light on what has been described as compassion energy or compassion satisfaction (Dunn, 2009; Hegney et al., 2014). This means that even though mediating compassion requires courage and a willingness to encounter not only the patient's suffering but also one's own vulnerability and indeed can be perceived as a challenge, it can also be a positive experience for nurses.

5.1. Limitations

One limitation is possibly related to the study's recruitment process, because the head nurse of each home care organization part of the study selected the potential participants. We nonetheless considered such an approach relevant, because we sought to explore the mediation of compassion (compassionate care) on a profound level. The strategy employed, where people who were acknowledged by others as experts in their practice of compassionate care were approached (cf. Nåden, 1998), enabled us to obtain rich and vivid data about the phenomenon being studied. Thus, the findings here are based on knowledgeable nurses’ experiences, which is beneficial when aiming for an understanding of core issues. Furthermore, we are of the opinion that the question on which the research was based has been well‐answered thanks to the rich data. Another limitation could be the lack of variation among participants regarding age and gender. Still, given that most experienced nurses in the context are middle‐aged women, there is limited variation to begin with.

That the first researcher alone conducted the initial data analysis might seem as a limitation. Nevertheless, such an approach also facilitated distanciation, which Ricoeur (1991) describes as essential for a valid interpretation. Involving the second researcher subsequent to the initial, preliminary analysis, enabled reflection on the (proposed) subthemes and themes as text free from the first researcher's contextual preunderstanding.

It would be valuable to see whether our interpretation of nurses’ experiences of mediating compassion in the home care context is also valid in other contexts and with respect to variations in nurses’ and patients’ ages, genders and cultures. We are aware that our findings do not describe the ontology of the phenomenon or stipulate what mediating compassion “is.” Rather, our findings indicate what compassion “is about” and therefore provides a basis for further exploration.

6. CONCLUSION

Mediating compassion can be understood as an element of human connectedness, mutuality and belonging. Such knowledge of mediating compassion will support nurses in understanding that sometimes they do not necessarily have to act but rather can engage in encountering the patient with humbleness and love, being in the moment and bearing responsibility for the patient. This may lead to a caring communion that alleviates suffering. Understanding that the key to mediating compassion does not involve doing but being may possibly relieve some stress for nurses who might feel obliged to act during nurse–patient encounters in the home care context.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors stated that there are no sources of conflicts.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jessica Hemberg contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis and discussion, and drafted the manuscript at all stages. Lena Wiklund Gustin contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis and discussion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the individuals who participated in this study.

Hemberg J, Wiklund Gustin L. Caring from the heart as belonging—The basis for mediating compassion. Nursing Open. 2020;7:660–668. 10.1002/nop2.438

Funding information

The scholarship fund “Sjuksköterskeföreningen i Finland rf” generously provided financial support for this study.

REFERENCES

- Adamson, E. , & Dewar, B. (2015). Compassionate care: Student nurses’ learning through reflection and the use of story. Nurse Education in Practice, 15, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/ [Google Scholar]

- Arman, M. , & Hök, J. (2007). Self-care follows from compassionate care–chronic pain patients’ experience of integrative rehabilitation. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 30(2), 374–381. 10.1111/scs.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, A. (2009). Measuring nursing care and compassion: The McDonaldised nurse? Journal of Medical Ethics, 35, 465–468. 10.1136/jme.2008.028530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, L. , & Matiti, M. (2014). How does it really feel to be in my shoes? Patients’ experiences of compassion within nursing care and their perceptions of developing compassionate nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 2790–2799. 10.1111/jocn.12537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, L. , O’Brien, M. R. , Kirton, J. , Zubairu, K. , & Christiansen, A. (2014). The role of professional education in developing compassionate practitioners: A mixed methods study exploring the perceptions of health professionals and pre‐registration students. Nurse Education Today, 34, 480–486. 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito‐Pons, G. , & Librada‐Flores, S. (2018). Compassion in palliative care: A review. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliat Care, 12, 472–479. 10.1098/SPC.0000000000000393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell, L. (2009). Compassionate care: A concept analysis. Home Health Care Management & Pract, 21, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission (2011). Dignity and nutrition inspection programme: National overview. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Care Quality Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, C. , & Ryder, E. (2009). Compassion and caring in nursing. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, C. , & Ryder, E. (2012). Excellence in compassionate nursing care: Leading the change. Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov, H. M. (2007). Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. British Medical Journal, 335, 184–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, J. , Donaldson, J. , & Smith, P. (2014). Nurse Education Today: Special issue on compassionate care. Nurse Education Today, 34, 1188–1189. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & NHS Commissioning Board (2012). Cummings J., & Bennett V. (Eds.), Compassion in practice: Nurs midwifery and care staff: Our vision and strategy. London UK. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar, B. , Adamson, E. , Smith, S. , Surfleet, J. , & King, L. (2014). Clarifying misconceptions about compassionate care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 1738–1747. 10.1111/jan-12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar, B. , & Cook, F. (2014). Developing compassion through a relationship centred appreciative leadership programme. Nurse Education Today, 34, 1258–1264. 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, D. J. (2009). The intentionality of compassion energy. Holistic Nursing Practice, 23, 222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebenstein, H. (1998). From the world of practice. They were once like us: Learning from home care workers who care for the elderly. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 30, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. (2006). Peterson C., Zetterlund J. (Eds.). The suffering human being. Chicago, IL: Nordic Studies Press; English edition. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. (2007). The theory of caritative caring: A vision. Nursing Science Quarterly, 20, 201–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics . (2012). Responsible conduct of research and produces for handling allegations of misconduct in Finland – RCS guidelines. Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved from http://www.tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/HTK_ohje_2012.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Frampton, S. B. , Guastello, S. , & Lepore, M. (2013). Compassion as the foundation of patient‐centered care: The importance of compassion in action. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 2, 443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. London, UK: Constable‐Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Gluschkoff, K. , Oksman, E. , Knafo‐Noam, A. , Dobewall, H. , Hintsa, T. , Keltikangas‐Järvinen, L. , & Hintsanen, M. (2018). The early roots of compassion: From child care arrangements to dispositional compassion in adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 28–32. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godlaski, T. M. (2015). On compassion. Substance Use & Misuse, 50, 942–947. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1007694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller, B. S. (2018). Bringing compassion back to the forefront of care. JONA: the Journal of Nursing Administration, 48, 175–176. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Service Commissioner for England (2011). Care and compassion? Report of the Health Service Ombudsman on ten investigations into NHS care of older people. London, UK: The Stationary Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hegney, D. G. , Craige, M. , Hemsworth, D. , Osseiran‐Moissin, R. , Aoun, S. , Francis, K. , & Drury, V. (2014). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, anxiety, depression and stress in registered nurses in Australia: Study 1 results. Journal of Nursing Management, 22, 506–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J. (2015). The source of life, love – Health’s primordial wellspring of strength. (In Swedish: Livets källa kärleken – hälsans urkraft). Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J. (2017). The dark corner of the heart – Understanding and embracing suffering as portrayed by adults. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31, 995–1002. 10.1111/scs.12424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakimowicz, S. , Perry, L. , & Lewis, J. (2017). Insights on compassion and patient‐centred nursing in intensive care: A constructivist grounded theory. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 1599–1611. 10.1111/jocn.14231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jull, A. (2001). Compassion: A concept exploration. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand Inc, 17, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, G. (2016). Compassion for simulation. Nurse Education in Practice, 16, 160–162. 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, E. (2000). Totality and infinity. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar]

- Lindseth, A. , & Norberg, A. (2004). A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18, 145–153. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, U. Å. , Nyström, L. L. , & Zetterlund, J. E. . (2018). Katie Eriksson. Theory of caritative caring In Alligood M. R. (Ed.), Nursing theorists and their work (9th ed., pp. 448–461). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier – Health Sciences Division. [Google Scholar]

- Lindwall, L. , Bouissad, L. , Kulzer, S. , & Wigerblad, A. (2012). Patient dignity in psychiatric nursing practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 569–576. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown, B. A. (2014). Toward more compassionate healthcare systems. Comment on “Enabling compassionate healthcare: Perils, prospects and perspectives”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2, 199–200. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, G. , & McConnell, S. (2015). Compassion: A critical review of peer‐reviewed nursing literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 3006–3015. 10.1111/jocn.12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nåden, D. (1998). When nursing becomes an art. An inquiry of some necessary prerequisites of nursing as art. (In Swedish: Når Sykepleie er kunstutövelse. En undersökelse av noen nödvendige forutsetninger for sykepleie som kunst.) (Doctoral thesis). Department of Caring Science, Åbo Akademi University, Vasa. [Google Scholar]

- Numminen, O. , Repo, H. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2017). Moral courage in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 24, 878–891. 10.1177/0969733016634155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, E. , & Thomasma, D. C. (1993). The virtues in medical practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pence, G. E. (1983). Can compassion be taught? Journal of medical ethics, 9(4), 189–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P. (1991). From text to action – Essays in hermeneutics II. London, UK: The Athlone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J. (2015). Compassion. Clinical Medicine, 15, 121–124. 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantz, M. L. (2007). Compassion: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 42, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. , Hack, T. F. , Raffin‐Bouchal, S. , McClement, S. , Stajduhar, K. , Singh, P. , … Chochinov, H. M. (2018). What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: A grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. British Medical Journal Open, 8, e019701 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. , McClement, S. , Raffin‐Bouchal, S. , Hack, T. F. , Hagen, N. A. , McConnell, S. , & Chochinov, H. M. (2016a). Compassion in health care: An empirical model. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51, 193–203. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. , Norris, J. M. , McConnell, S. J. , Chochinov, H. M. , Hack, T. F. , Hagen, N. A. , … Bouchal, S. R. (2016b). Compassion: A scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliative Care, 15 10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spandler, H. , & Stickley, T. (2011). No hope without compassion: The importance of compassion in recovery‐focused mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straughair, C. (2012a). Exploring compassion: Implications for contemporary nursing. Part 1. British Journal of Nursing, 21, 160–164. 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.3.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straughair, C. (2012b). Exploring compassion: Implications for contemporary nursing. Part 2. British Journal of Nursing, 21, 239–244. 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.4.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, K. , & Jansson, L. (2003). ‘Understanding and being understood’ as a creative caring phenomenon – In care of patients with stroke and aphasia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 107–116. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehranineshat, B. , Rakhshan, M. , Torabizadeh, C. , & Fararouei, M. (2018). Nurses’, patients’ and family caregivers’ perceptions of compassionate nursing care. Nursing Ethics, 26, 1707–1720. 10.1177/0969733018777884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses . (2012). International council of nurses. 978–92‐95094‐95‐6 (Switzerland). Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%2520eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.) (Eds.) (1989). Random house Webster’s unabridged dictionary (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Thorup, C. , Rundqvist, E. , Roberts, C. , & Delmar, C. (2012). Care as a matter of courage: Vulnerability, suffering and ethical formation in nursing. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 26, 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Cingel, M. (2011). Compassion in care: A qualitative study of older people with a chronic disease and nurses. Nursing Ethics, 18, 672–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Cingel, M. (2014). Compassion: The missing link in quality of care. Nurse Education Today, 34, 1253–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dietze, E. , & Orb, A. (2000). Compassionate care: A moral dimension of nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 7, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. (2003). Love and caring. Ethics of face and hand – An invitation to return to the heart and soul of nursing and our deep humanity. Nurs Adm, 27, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. (2005b). Caring science: Belonging before being as ethical cosmology. Nursing Science Quarterly, 18, 304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. (2005a). Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. (2008). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring (Rev. Ed., pp. 45–199). Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund Gustin, L. , & Wagner, L. (2013). The butterfly effect of caring – Clinical nursing teachers’ understanding of self‐compassion as a source to compassionate care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27, 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, D. G. , & Leone‐Sheehan, M. L. (2018). Watson’s philosophy and theory of transpersonal caring In Alligood M. R. (Ed.), Nursing theorists and their work (9th ed., pp. 66–79). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Young‐Mason, J. (1994). An understanding of compassion in Nepo’s Acre of light. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 8, 156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V. , Valizadeh, L. , Rahmani, A. , van der Cingel, M. , & Ghafourifard, M. (2018). Factors facilitating nurses to deliver compassionate care: A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32, 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]