Abstract

Aim

To summarize evidence on the poststroke coping experiences of stroke patients and spousal caregivers living at home in the community.

Design

A scoping review.

Methods

Extensive searches were conducted in credible databases. Articles published in the English language were retrieved. Data were extracted based on study location, aims, study design, sample size, time after stroke and key findings.

Results

Out of 53 identified articles, 17 studies were included in the review. Five key themes were as follows: (a) emotional challenges; (b) role conflicts; (c) lack of strategies in coping; (d) decreased life satisfaction of the couples; and (e) marriage relationship: at a point of change. Couples were not sufficiently prepared to cope and manage with stroke at home on discharge from the hospital. This review emphasized the need for hospitals to implement policies to address the inadequate preparation of couples in coping with stroke.

Keywords: community, coping, couples, experience, manage, nurses, nursing, stroke

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally. It is the fifth leading cause of death of people aged 15–59, claiming 6.2 million lives each year (World Health Organization, 2018). Stroke is a traumatic life event that affects not only the person who has a stroke but also their family caregivers (Singapore National Stroke Association, 2017). Stroke patients who live with disability will require assistance, creating challenges for the family members who care for them. In addition to physical, social and financial demands, the emotional impact of dealing with stroke can place tremendous stress on persons with stroke and their family caregivers (American Stroke Association, 2019).

The supportive care of a spousal caregiver has been considered pivotal to a stroke victim's recovery (Claesson, Gosman‐Hedstrom, Johannesson, Fagerberg, & Blomstrand, 2000; Persson, Ferraz‐Nunes, & Karlberg, 2012). Persons with stroke are usually looked after by their spouse, who gives them extensive support ranging from psychosocial to physical care (Adriaansen, Leeuwen, Visser‐ Meily, Bos, & Post, 2011). Six months after a stroke, approximately 4.6 hr per day is required to care for a person with stroke (Tooth, McKenna, Barnett, Prescott, & Murphy, 2005). With the addition of providing surveillance while caring, the hours required for caregiving could rise up to 14.2 hr per day (van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Berg, Brouwer, & van den Bos, 2005). As stroke has an impact on both patients and their spouse, a better understanding of the experience of couples in coping with managing stroke at home is necessary. This would facilitate the provision of support when a stroke patient is discharged and the responsibility of caring for the patient is transferred from the hospital to the home. Traditionally, the term “spouse” refers to a husband or wife to whom one is legally married. The contemporary definition of a spouse now takes into account heterosexual common law relationships and partnerships (Ferlisi, 2001). The terms “spouse” and “partner” are used interchangeably in this review.

Current studies have examined the caregiver burden after a stroke (Rigby, Gubitz, & Phillips, 2009); the informational needs of stroke patients and their caregivers (Forster et al., 2012); the educational needs of stroke caregivers and persons with stroke (Hafsteinsdóttir, Vergunst, Lindeman, & Schuurmans, 2011); positive experiences of stroke caregiving (Mackenzie & Greenwood, 2012); and the rehabilitative experiences of stroke patients (Peoples, Satink, & Steultjens, 2011). However, there is a dearth of knowledge about coping with stroke at home in the community from the perspective of couples. The aim of this scoping review was to summarize the evidence on the poststroke coping experiences of spousal caregivers and persons with stroke living at home in the community. Such a review will provide the basis for recommending strategies for healthcare professionals and policymakers to consider when devising means to enhance essential discharge preparation procedures and support. The following research questions were raised for this review:

What is known from the existing literature about the coping experiences of couples in the community after the stroke of a spouse?

What is the impact on the spousal relationship after a stroke?

2. METHOD

The scoping review framework of Arskey and O'Malley (2005) was the method selected to underpin this review. Scoping reviews are conducted to understand the range and nature of research activity; to recognize gaps in the research literature; and to summarize key findings for practitioners who may lack the time or resources to carry out such work themselves (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The steps in conducting a scoping review include the following: (a) identifying the research questions; (b) identifying relevant studies, (c) selecting the studies; (d) charting the data; and (e) collating, summarizing and reporting the results (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). A scoping review does not appraise the quality of the evidence but rather rigorously and transparently maps out key research areas (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005).

2.1. Identifying and selecting relevant studies

An extensive literature search was conducted from credible electronic databases. Primary databases that were used in the search for relevant articles included CINAHL, Embase, PubMed and Psych‐Info. The search covered studies published in the English language from 2008–2018. The primary focus of the review was on the experiences of couples coping with stroke in the community. The keywords used in the search were “stroke”, “couples”, “experience”, “coping”, “management” and “community”. The Boolean search was comprised of the following operators and keywords:

Stroke OR cerebrovascular disease

Spouse* OR partner OR (husband or wife)

Coping OR experience* OR manage*

Community OR home

2.2. Charting the data

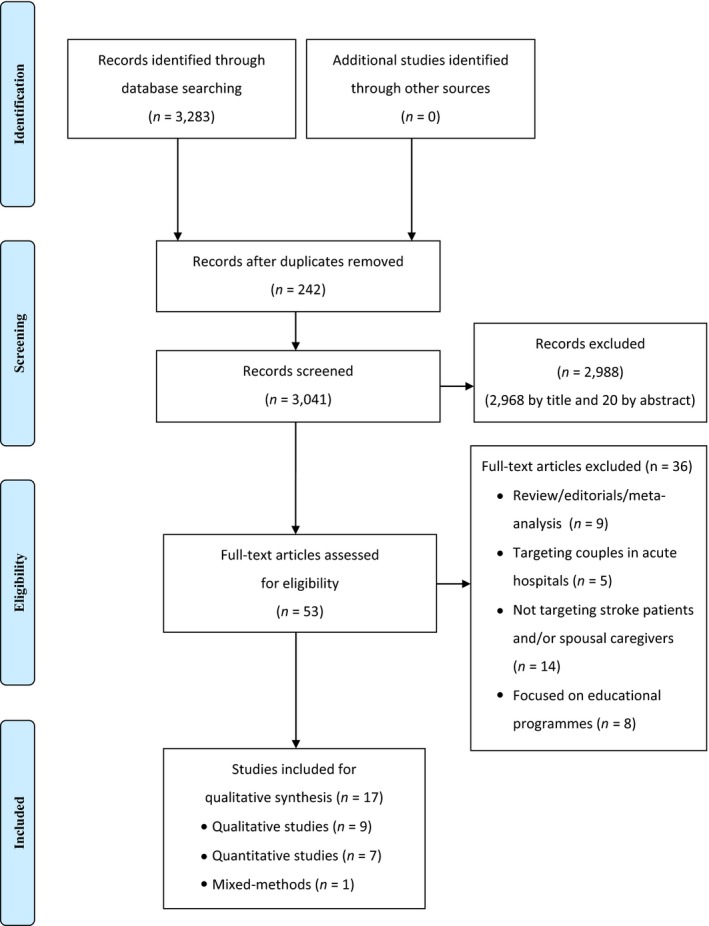

A total of 3,283 publications were identified via a search of the electronic databases. No additional records were identified through a hand or author search. Duplicates were removed with the aid of EndNoteX7 (N = 242). The remaining records (N = 3,041) were screened by title. A total of 2,968 articles were excluded, after which 73 articles remained. The abstracts of these 73 articles were screened, after which a further 20 articles were excluded. The full texts of the resulting 53 articles were then scrutinized using the criteria for inclusion in this scoping review. Thirty‐four articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. In the end, a total of 17 articles, consisting of nine qualitative studies, seven quantitative studies and one mixed‐methods study, were included. The process of screening and selecting the articles for the review is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature screening and selection based on PRISMA

2.3. Collating, summarizing and reporting results

An overview of the studies that were included in this review is given in Table 1. Data from the included studies were systematically extracted using the following headings: authors(s), year of publication, study location, aims of study, design, method, sample size, time after stroke and key findings. Drawing on the principles of thematic analysis put forward by Braun and Clarke (2006), the findings of the review were synthesized in relation to the scoping review questions. Familiarization with the studies was achieved first through reading and re‐reading. This facilitated the systematic organization of the findings from each study into meaningful clusters and their further categorization into the respective key findings in terms of themes.

Table 1.

Overview of the studies

| No | Author/date/location | Aims of study | Design/Methods | Sample size | Time after stroke | Key findings | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies on couples coping poststroke at home | |||||||

| 1 |

Achten, Visser‐Meily, Post, and Schepers, (2012) Nieuwegein, The Netherlands |

To compare the life satisfaction of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers To examine spouses’ variables as determinants of the life satisfaction of patients |

Cross‐sectional survey/questionnaires were administered |

78 couples participated Mean age of stroke patients: 59 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 55 |

3 years poststroke |

|

Decreased life satisfaction of the couples |

| 2 |

Anderson et al. (2017) Alberta, Canada |

To understand the key themes related to the reconstruction and breakdown of marriages poststroke | Qualitative/constructivist grounded theory/semi‐structured interviews were conducted |

18 couples participated Mean age of stroke patients: 62.6 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 62.3 |

Unspecified |

|

|

| 3 |

Ekstam, Tham, & Borell (2011) Stockholm, Sweden |

To identify and describe couples’ approaches to changes in everyday life 1 year poststroke | Qualitative/case study/interviews were conducted |

2 couples Mean age of stroke patients: 78.5 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 74.5 years |

1 year poststroke |

|

Emotional challenges |

| 4 |

Green and King (2009) Calgary, Canada |

To explore male patients and their wife caregivers’ perceptions of factors that affect their quality of life and caregiver strain 1 year poststroke | Qualitative/semi‐structured interviews were conducted |

26 couples Mean age of stroke patients: 63.9 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 58.5 |

1 year postdischarge |

|

|

| 5 |

Godwin, Swank, Vaeth, and Ostwald (2013) Houston, USA |

To examine the longitudinal dyadic relationship between caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ mutuality and caregivers’ and stroke survivors’ perceived stress | Longitudinal survey over 1 year/questionnaires were administered to the participants |

159 stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers Mean age of stroke patients: 62.5 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 60.6 |

12 months poststroke |

|

Marriage relationship: at a point of change |

| 6 |

McCarthy and Bauer (2015) Ohio, USA |

To report findings from qualitative interviews of couples coping with stroke | Qualitative/structured survey followed by open‐ended individual interviews |

31 couples (62 survivors and spouses) participated Mean age of stroke patients: 61.81 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 60.42 |

1–36 months |

|

Emotional challenges |

| 7 |

McCarthy and Lyons (2015) Ohio, USA |

To investigate stroke survivors’ and caregiving spouses’ individual perspectives on survivor cognitive and physical functioning and the extent to which incongruence between the perceptions of the partners affects a spouse's depressive symptoms and overall mental health | Mixed‐methods/questionnaires were administered and interviews were conducted |

35 couples participated Mean age of stroke patients: 60 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 58 years |

1–24 months poststroke |

|

Emotional challenges |

| 8 |

Ostwald et al. (2009) Houston, USA |

To describe levels of stress in stroke survivors and spousal caregivers and identify predictors of stress in couples during their first year at home | Longitudinal survey over 1 year/questionnaires were administered |

159 couples took part Mean age of stroke patients: 66.4 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 62.5 years |

3 months poststroke |

|

Emotional challenges |

| 9 |

Quinn et al. (2014) Bolton, United Kingdom |

To explore the experiences of couples when one partner has a stroke at a young age | Qualitative/semi‐structured interviews were conducted |

8 couples took part Mean age of stroke patients: 51 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 49.63 years |

1–9 years poststroke |

|

|

| 10 |

Rochette et al. (2007) Sherbrooke, Canada |

To describe changes in the process of adaptation in the first 6 months after a stroke and to identify domains of the adaptation process in relation to participation and depressive symptoms for dyads | A short longitudinal survey over 6 months/questionnaires were administered to participants |

88 individuals with first stroke and 47 spouses Mean age of stroke patients: 71.8 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 61.2 years |

2 weeks−6 months poststroke |

|

|

| 11 |

Visser‐Meily, Post, van de Port, van Heugten, & van den Bos, (2008) Maastricht, The Netherlands |

To describe the psychosocial functioning of spouses at 1 and 3 years poststroke and to identify predictors of negative changes in psychosocial functioning | Longitudinal survey over 3 years/questionnaires were administered |

119 stroke couples participated Mean age of stroke patients: 56 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 53 years |

1–3 years poststroke |

|

|

| 12 |

Visser‐Meily et al., (2009) Maastricht, The Netherlands |

To describe the psychosocial functioning of stoke spousal caregivers and examine their coping styles | Longitudinal survey over 3 years/questionnaires were administered |

211 stroke couples participated Mean age of stroke patients: 56 years Mean age of spousal caregivers: 54 years |

3 years poststroke |

|

|

| Studies on the experiences of spousal caregivers caring for stroke patients and coping at home | |||||||

| 13 |

Adriaansen, Leeuwen, Visser‐Meily, Bos, and Post (2011) Amsterdam, The Netherlands |

To examine the course of social support for spousal caregivers and understand the associations between social support and life satisfaction | Prospective cohort study/questionnaires were administered |

180 spouses participated Mean age of spousal caregivers: 53.3 |

2 months (T1), 1 year (T2), and 3 years (T3) poststroke discharge |

|

Decreased life satisfaction of the couples |

| 14 |

Buschenfeld, Morris, and Lockwood (2009) Bristol, United Kingdom |

To investigate the experiences of partners of young stroke survivors (<60 years old) | Qualitative/semi‐structured interviews were conducted |

7 partners of stroke patients participated Mean age of spousal caregivers: 54.6 |

2–7 years poststroke |

|

Lack of strategies for coping |

| 15 |

Gosman‐Hedstrom & Dahlin‐Ivanoff (2012) Goteborg, Sweden |

To explore older women's experiences of their life situation and formal support as carers | Qualitative/focus group interviews were conducted |

16 spousal caregivers participated Mean age of spousal caregivers: 74.3 |

2–15 years |

|

|

| 16 |

Satink, Cup, De Swart, & Sanden (2018) Nijmegen, The Netherlands |

To explain how the partners of stroke patients described their own self‐management and their spouses’ management and how they have been supported postdischarge | Qualitative/focus group interviews were conducted |

33 spouses of stroke patients participated Mean age of spousal caregivers: 59.2 years |

At least 3 months poststroke |

|

Emotional challenges |

| Study on stroke patients’ experiences and coping with spousal caregivers at home | |||||||

| 17 |

Thompson and Ryan (2009) Coleraine, Northern Ireland |

To understand the impact of the consequences of stroke on spousal relationships from the perspective of stroke patients | Qualitative/semi‐structured interviews were conducted |

16 stroke patients participated Mean age of stroke patients: 56 years |

Mean length of time: 18 months poststroke |

|

|

2.4. Ethics

This scoping review exercise was conducted as a desktop study. While statutory ethical approval was not required for such a study, it was carried out in an ethical manner.

3. RESULTS

Amongst the 17 studies that were included, nine were qualitative studies, one was a mixed‐methods study, and seven were quantitative studies. Amongst the seven quantitative studies, five were longitudinal studies, one was a cross‐sectional survey, and one was a cohort study. The included studies were conducted in six different regions or countries. More than half were conducted in Europe (N = 10), namely the Netherlands (N = 5), Sweden (N = 2), Ireland (N = 1) and the UK (N = 2), while the others were conducted in North America: the USA (N = 4) and Canada (N = 3). None of the studies included in the review were conducted in Asia.

Twelve out of the 17 studies focused on couples coping poststroke at home. The number of couples in the studies ranged from 2–211, with an average of 82 and a mean age of 60.8 years (range, 49.6–78.5 years old) (Nos. 1–12). Four studies focused on the experiences of spousal caregivers caring for stroke patients and their coping at home (Nos. 13–16). The mean sample size was 59 spouses (range, 7–180), with a mean age of 60.4 years old (range 53.3–74.3 years). The spousal caregivers had cared for their partner with stroke for 2 months to 15 years since the time of the stroke. One study focused on the stroke patients’ experiences, including those relating to coping with spousal caregivers at home (No. 17). That study included a total of 16 stroke patients with a mean age of 56, who had been living with stroke for an average of 18 months.

Five key themes were identified from the scoping review: (a) emotional challenges; (b) role conflicts; (c) lack of strategies in coping; (d) decreased life satisfaction of the couples; and (e) marriage relationship: at a point of change.

3.1. Theme 1 Emotional challenges

Thirteen reported on the emotional challenges faced by the stroke patients and their spousal caregivers (Nos. 2–4, 6–12, 15–17). These included feelings of emotional overwhelmment, stress, depression, loneliness, irritability and intolerance.

Five studies reported that the couples felt emotionally overwhelmed after the stroke event, which increased their sense of vulnerability (Nos. 2–4, 6, 9). “Vulnerability” was perceived by couples as a lack of control over the poststroke situation (No. 4). They lacked control due to uncertainty over the patient's prognosis; the demand for care because of the stroke patient's physical impairments; and a lack of information and support from healthcare professionals, which triggered feelings of distress, anxiety and frustration in the stroke couples (Nos. 2–4, 6, 9). Two studies examined the stress levels of stroke couples after the stroke patient had been discharged to go home from the rehabilitation hospital (Nos. 8, 10). In both studies, the stress levels of the couples were measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and the Stress Appraisal Measure (SAM). Interestingly, stroke patients who were discharged to go home experienced lower levels of stress (mean score of 10.4, SD 7.30) than those who had been admitted to hospital (mean score of 12.3, SD 7.46) (No. 8). Spousal caregivers at home also experienced a slight decrease in their stress levels (mean score of 13.2, SD 7.12) than those caring for a partner in the hospital (mean score of 14.0, SD 7.25). Overall, spousal caregivers experienced higher levels of stress than the stroke patients, with a positive correlation between the PSS score of the stroke patient and that of the spousal caregiver (p < .01) (No. 8). Another study reported that the stress levels of spousal caregivers did not decline significantly over 6 months after the stroke patient was discharged home (No. 10). The results showed that when compared with stroke patients, spousal caregivers experienced higher levels of stress at home as a result of caring for their spouse with stroke over a period of 6 months to 1 year after the patient's discharge from a rehabilitation hospital.

Three other studies examined the manifestation of depressive symptoms in the spousal caregivers of stroke patients (Nos. 7, 11, 12). The symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) and the Goldberg Depression Scale (GDS). In one study, 51% of spousal caregivers were found to have experienced depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 2) even 1 year after having been discharged to go home (No. 11).

Qualitatively, two studies reported on the spousal caregivers’ feelings of loneliness, helplessness, sadness, guilt and aggression as they struggled to comprehend their partner's poststroke behavioural changes and other symptoms (Nos. 15, 16). Both studies reported on the spouses’ sense of “loneliness and helplessness” and of being “lost” in that they felt as though they were caring for a “different” person after the stroke.

One study that explored the experiences of stroke patients reported that despite being conscious about their feelings of anger, irritability, agitation and intolerance towards their spousal caregivers, stroke patients were unable to control such emotional outbursts after the stroke (No. 17). This led to increased misunderstandings and arguments between couples, which further heightened the stroke patients’ guilt and despair. Overall, emotional challenges are common experiences of couples after a stroke.

3.2. Theme 2 Role conflicts

Five studies included in the review reported on the role conflicts between the stroke patient as the “care recipient” and the spouse as the “protector” after the stroke (Nos. 2, 4, 9, 15, 17). In these studies, male stroke patients felt conflicted about their masculine image and role as protector of the family, as they felt powerless about no longer being able to protect their family (No. 17). At times, they felt infantilized due to their spousal caregiver's hyper‐vigilance and overprotectiveness at home. This led to male stroke patients feeling sensitive about the change in their role to that of “care recipient” and about their inability to contribute financially to their family after a stroke (No. 4, 9). Male stroke patients grieved for their former self, who had been regarded by their wife as a “man” and “spouse” (No. 9).

3.3. Theme 3 Lack of strategies in coping

How stroke patients and their spousal caregivers coped after the stroke was reported in three studies (Nos. 10, 12, 14). These studies measured coping using the Revised Ways of Coping Questionnaire (R‐WCQ) (No. 10). Another study quantitatively reported on the coping of spousal caregivers, using the Utrecht Coping List (UCL) (No.12). The R‐WCQ measures five subscales of coping strategies, including coping through rationalization, hope, escape, openness towards others and giving control to others (No. 10). The UCL consists of seven subscales that measure the coping styles of active tackling, seeking social support, palliative reacting, avoiding, passive reacting, reassuring thoughts and the expression of emotions (No. 12).

Couples’ ways of coping with stroke at 6 months were determined using the R‐WCQ (No. 10). Stroke patients coped through “rationalization” and “giving control to others”, while spousal caregivers coped by “rationalization” and “openness towards others” (No. 10).

The coping styles of spousal caregivers were measured using the UCL (No. 12). It was found that spousal caregivers engaged in passive and avoidance coping at 3 years after a stroke. An example of avoidance coping included spousal caregivers “walking away” from caring for their partner with stroke (No. 12). Another study reported that spousal caregivers engaged in problem‐focused coping and the avoidance of emotional expressions when managing care related to practical tasks at home (No. 14). Spousal caregivers were found to suppress their emotions, disregard what they were feeling and focus on the tasks required to take care of stroke patients at home. Despite frustrations over their partner's inability to do some physical tasks at home, spouses continued to carry out the daily practical tasks of caring for the stroke patient at home (No. 14).

3.4. Theme 4 Decreased life satisfaction of the couples

Three studies explored the life satisfaction of couples living with stroke (Nos. 1, 11, 13). In all three studies, life satisfaction was measured using LiSat‐9 scores. One study reported that 48% of spousal caregivers were dissatisfied with life 1 year after the stroke of their partner (No. 11). Another study reported that more spouses (50%) were dissatisfied with life than stroke patients (28%), with a total LiSat‐9 score of ≤4 at 3 years after the stroke (No. 1). The third study reported that caregiver strain was positively associated with lower life satisfaction in spousal caregivers over 3 years after a stroke (No. 13). This is evidence that following a stroke the spousal caregiver has a lower level of life satisfaction than the stroke patient.

3.5. Theme 5 Marriage relationship: at a point of change

Three other studies reported that couples considered their marriage relationship to be at a point of change after a stroke (Nos. 2, 5, 15). One study reported that three couples who had been married for 11–15 years divorced after a stroke (No. 2). In this study, spousal caregivers felt that their efforts to care for their partner were not appreciated, while patients felt that their spouse lacked sensitivity towards their feelings and physical disability after the stroke. Stroke patients and spousal caregivers, who assumed that their partner was disengaging from the marriage relationship after the stroke, interpreted interactions with their partner in a negative light (No. 2). A quantitative study that measured positive relationship engagement between couples using the Mutuality Scale (MS) found that the mutuality scores of stroke partners decreased significantly at 1 year after a stroke (F = 15.56, p < .0001), which was attributed to a strained relationship (No. 5).

Another study reported that female spousal caregivers felt that “life was a struggle.” They were “tied” to the home while caring for their partner with stroke. They missed their female network and having time for themselves (No. 15). The female spousal caregivers negotiated with their partner to get some “time off for themselves.” The stroke partner was sent to a day rehabilitation centre or nursing home for a few days, with the promise of being picked up later. Overall, the stroke couples found their relationship to be at a point of change during the course of the stroke partner's recovery.

4. DISCUSSION

The most significant finding from this scoping review was that couples were unable to effectively cope with stroke in the community. Globally, an estimated 30 cases of stroke occur every 60 s; thus, a good understanding of stroke patients and their spousal caregiver's experiences and their ways of coping with stroke at home is essential. This would allow healthcare professionals to design appropriate supportive interventions to enhance the coping of couples in managing stroke survivorship at home (World Health Organization, 2018). The results of this review lead to the conclusion that after a stroke, stroke patients and their spousal caregivers face emotional challenges, role conflicts, ways of coping and decreased life satisfaction from managing at home. Although they had tried to cope with the stroke situation at home, the couples found themselves at a point of change in their married life. This information adds to the existing knowledge base about the coping of stroke patients and their spousal caregivers as couples, a subject that was often neglected in previous studies (Harris & Bettger, 2018; Lou, Carstensen, Jørgensen, & Nielsen, 2017). In addition, this scoping review sheds new light on the caregiving situation at home after hospitalization, from the perspective of the couples. Based on the current evidence, the time after the patient has been discharged to return home is a crucial period for addressing the education and support needs of stroke patients and their caregivers (Cameron & Gignac, 2008).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review about how couples cope at home after a stroke. The emotional challenges that such couples face have included feelings of emotional overwhelmment, stress, depression, loneliness, irritability and intolerance (Anderson, Keating, & Wilson, 2017; Ekstam, Tham, & Borell, 2011; Green & King, 2009; Gosman‐Hedstrom & Dahlin‐Ivanoff, 2012; McCarthy & Bauer, 2015; McCarthy & Lyons, 2015; Ostwald, Bernal, Cron, & Godwin, 2009; Quinn, Murray, & Malone, 2014; Rochette, Bravo, Desrosiers, St‐Cyr Tribble, & Bourget, 2007; Satink, Cup, De Swart, & Sanden, 2018; Thompson & Ryan, 2009; Visser‐Meily, Post, van de Port, van Heugten, & van den Bos, 2008; Visser‐Meily et al., 2009). The results are quite similar to those of another review on couples coping with cancer (Traa, De Vries, Bodenmann, & Den Oudsten, 2015). Furthermore, we confirmed with other reviews that the emotional challenges experienced by stroke couples at home have been attributed to a lack of informational support and inadequate discharge preparation on stroke management by healthcare professionals (Forster et al., 2012; Peoples, Satink, & Steultjens, 2011). On the other hand, we found that being a couple and taking care of a spouse's well‐being may have a detrimental effect on the couple's relationship. Some recent studies on the well‐being of married couples have reported that chronic illness is a risk factor for divorce (Badr & Acitelli, 2017;Karraker & Latham, 2015).

This review identified different types of coping strategies that spousal caregivers adopted, such as “rationalization,” “being open towards others,” “passive coping” and “avoidance coping.” Existing studies have indicated that spousal caregivers who relied more on “active coping” and participated more in social activities experienced less stress than those who relied on other approaches (Forsberg‐Wärleby, Möller, & Blomstrand, 2004). It was further suggested that “active coping” maybe prove to be effective as a coping strategy for both stroke patients and their spousal caregivers in dealing with the poststroke situation (Visser‐Meily et al., 2009). If this is the case, more efforts should be made to encourage stroke couples to cope actively with their challenging situation.

It was found in other studies that the physical impairments of stroke patients impose changes in their role and that of their spousal caregiver. Male stroke patients experienced role conflicts when they can no longer acts a “protector” of their family at home (Taule & Råheim, 2014). This highlights the importance of education in addressing, prior to the patient's discharge, the potential challenges of conflicting ideas between stroke couples about the patient's role. It was suggested that female spousal caregivers should be made aware of creating opportunities for male stroke patients to contribute and participate in caring for themselves (Palmer & Palmer, 2011).

Other studies about spouses caring for patients with chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, reported that such spouses experienced caregiver burden and decreased life satisfaction over time (Joling et al., 2015). Similarly, we found in this review that while providing care at home spousal caregivers were more dissatisfied with life than the stroke patients. Therefore, interventions are needed to provide support to help spousal caregivers to cope and prepare to provide care at home (Rubbens, Clerck, & Swinnen, 2016). Li, Xu, Zhou and Loke (2015) systematically developed the Caring for Couples Coping with Cancer (4Cs) intervention programme to support couples in coping with cancer. The intervention was implemented in the hospitals before the patients were discharged to go home, with the aim of improving dyadic communication, dyadic coping, dyadic appraisal and quality of life. Besides the medical management of cancer, the 4Cs intervention emphasizes the importance of healthcare workers treating couples as “people” who require holistic support to cope after a family member has been diagnosed with cancer (Li, Xu, Zhou, & Loke, 2015). Another study examined the effects of a couple‐oriented intervention on patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and their spousal caregivers (Martire, Schulz, Keefe, Rudy, & Starz, 2007). The results of the study indicated that a couple‐oriented interventional approach comprised of support and education is valuable for spouses 6 months postintervention. Spousal caregivers experienced better outcomes in depressive symptoms and mastered their caregiver role after participating in the intervention, thereby indirectly benefiting the care delivered to patients with OA at home in the community (Martire et al., 2007). The various studies confirmed that couple‐oriented interventional approaches for patients and their spousal caregivers better prepare couples for their journey of coping with chronic health conditions.

Support interventions developed by medical and nursing healthcare professionals for couples with medical conditions have been found to have a positive impact on couples coping with home life after one of them has been discharged from the hospital. For example, a 12‐week group support intervention was designed for couples coping with a spouse's first diagnosis of myocardial infarction (Stewart, Davidson, Meade, Hirth, & Weld‐Viscount, 2001). The processes of the intervention included social comparisons, social learning and social exchanges, where emotional, informational and affirmational supports were rendered. The group support intervention had a positive effect on the couples’ coping, confidence, outlook in life and relationship with their partner (Stewart et al., 2001). Interestingly, another focus group study on the experiences of Chinese couples during convalescence from a first heart attack recognized the need for healthcare professionals to be better equipped to establish culturally sensitive support interventions for couples (Wang, Thompson, Chair, & Twinn, 2008). Compared with their Western counterparts, Chinese couples preferred to stay longer in bed and participated passively in exercise sessions that delayed their resumption of normal work on the patient's discharge from hospital. Throughout the phase of transitioning from hospital to home, Chinese couples reported feeling uncertainty and distress and had difficulties in adapting to changes in their lifestyle after a heart attack (Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, prior to developing an intervention, a further qualitative inquiry may need to be conducted to determine the personal values, cultural beliefs and practices in stroke management of stroke patients and their spousal caregivers. One study reported that the Indian Muslim community in South Africa believe that the occurrence of stroke is due to God's will (Bham & Ross, 2005). It is difficult to develop a culturally sensitive support intervention without much knowledge about how people of different ethnic groups experience and cope with the situation of stroke. Therefore, before any interventions are developed for stroke couples, a deeper understanding of the cultural beliefs of this target group should be taken into consideration to strengthen the development of a culturally sensitive intervention.

4.1. Limitations of the review

There are limitations to this scoping review, although it was intended to deepen our current knowledge related to the coping of stroke couples at home in the community. Only articles written in the English language were included. As such, the review might have missed important articles written in other languages. Although quantitative studies were included, some methodological weaknesses were evident. For instance, the generalizability of the quantitative results was limited in the longitudinal, cross‐sectional, cohort and mixed‐methods study designs. The studies included in the review also lacked a power analysis and an explanation of how the sample size was calculated.

4.2. Clinical relevance

The results of this scoping review contribute to knowledge pertaining to stroke couples coping at home in the community and have implications for both nursing policy and practice. It is critical to sufficiently prepare and support stroke patients and their spousal caregivers in their coping before the patient is discharged from hospital. The results of this review highlight the importance of carefully developing and implementing policies in hospitals to address the lack of support for stroke couples to effectively cope at home. Implementing support interventions for stroke couples in the nursing routine care plan would contribute to couples having more confidence in coping with stroke, even after the patient is discharged to go home from the hospital.

4.3. Implications for practice

Nurse educators could play a pivotal role in guiding couples to cope with their stroke situation in hospital settings

Ways of supporting stroke patients and their spousal caregivers could be included in the undergraduate, postgraduate and in‐service education to raise awareness amongst nurses. Further training would enable nurses to better support stroke patients and their spousal caregivers in their everyday professional life.

5. CONCLUSION

It is clear from this review that stroke is a life‐changing event for the patients and the spousal caregivers. Healthcare professionals have a significant role to play in supporting stroke patients and their spousal caregivers during the poststroke trajectory. This review discussed the importance of providing a supportive intervention to better prepare stroke patients and their spousal caregivers, prior to the patient's discharge from hospital. The intervention would be designed to help couples cope at home after a stroke. Such an intervention should be developed based on evidence and on the identified needs of the couples according to the Medical Research Council framework for developing complex interventions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SR, AYL and VCLC: Study design, data collection and data analysis. AYL and VCLC: Study supervision. SR: Manuscript writing. AYL and VCLC: Critical review for important intellectual content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is supported by Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme (HKPFS) (application number: A1600569), award number: project code 1‐904Z.

Ramazanu S, Loke AY, Chiang VCL. Couples coping in the community after the stroke of a spouse: A scoping review. Nursing Open. 2020;7:472–482. 10.1002/nop2.413

REFERENCES

- Achten, D. , Visser‐Meily, J. M. , Post, M. W. , & Schepers, V. P. (2012). Life satisfaction of couples 3 years after stroke. Disability & Rehabilitation, 34(17), 1468–1472. 10.3109/09638288.2011.645994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriaansen, J. J. E. , Leeuwen, C. M. C. , Visser‐Meily, J. M. A. , Bos, G. A. M. , & Post, M. W. M. (2011). Course of social support and relationships between social support and life satisfaction in spouses of patients with stroke in the chronic phase. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(2), 48–52. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Stroke Association (2019). For family caregivers. Available at: https://www.strokeassociation.org/en/help-and-support/for-family-caregivers accessed 21 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S. , Keating, N. C. , & Wilson, D. M. (2017). Staying married after stroke: A constructivist grounded theory qualitative study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 24(7), 479–487. 10.1080/10749357.2017.1342335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badr, H. , & Acitelli, L. K. (2017). Re‐thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 44–48. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bham, Z. , & Ross, E. (2005). Traditional and western medicine: Cultural beliefs and practices of South African Indian Muslims with regards to stroke. Ethnicity & Disease, 15(4), 548–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buschenfeld, K. , Morris, R. , & Lockwood, S. (2009). The experience of partners of young stroke survivors. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(20), 1643–1651. 10.1080/09638280902736338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, J. I. , & Gignac, M. A. M. (2008). “Timing It Right”: A conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient Education and Counseling, 70(3), 305–314. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson, L. , Gosman‐Hedstrom, G. , Johannesson, M. , Fagerberg, B. , & Blomstrand, C. (2000). Resource utilization and costs of stroke unit care integrated in a care continuum: A 1‐year controlled, prospective, randomized study in elderly patients: The Goteborg 70 + stroke study. Stroke, 31, 2569–2577. 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2569 https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstam, L. , Tham, K. , & Borell, L. (2011). Couples' approaches to changes in everyday life during the first year after stroke. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 18(1), 48–58. 10.3109/11038120903578791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlisi, O. (2001). Recognizing a fundamental change: A comment on Walsh, the Charter and the definition of spouse. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/cajfl18%26div=8%26id=%26page= (assessed 16 July 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg‐Wärleby, G. , Möller, A. , & Blomstrand, C. (2004). Psychological well‐being of spouses of stroke patients during the first year after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18(4), 430–437. 10.1191/0269215504cr740oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A. , Brown, L. , Smith, J. , House, A. , Knapp, P. , Wright, J. J. , & Young, J. (2012). Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, 1–76. 10.1002/14651858.CD001919.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, K. M. , Swank, P. R. , Vaeth, P. , & Ostwald, S. K. (2013). The longitudinal and dyadic effects of mutuality on perceived stress for stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ageing & Mental Health, 17(4), 423–431. 10.1080/13607863.2012.756457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosman‐Hedström, G. , & Dahlin‐Ivanoff, S. (2012). 'Mastering an unpredictable everyday life after stroke'–older women's experiences of caring and living with their partners. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 26, 587–597. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, T. L. , & King, K. M. (2009). Experiences of male patients and wife‐caregivers in the first year post‐discharge following minor stroke: A descriptive qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(9), 1194–1200. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.008 https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafsteinsdóttir, T. B. , Vergunst, M. , Lindeman, E. , & Schuurmans, M. (2011). Educational needs of patients with a stroke and their caregivers: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(1), 14–25. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, G. , & Bettger, J. P. (2018). Parenting after stroke: A systematic review. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324163725_Parenting_after_stroke_a_systematic_review accessed 12 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Joling, K. J. , Marwijk, H. W. J. , Veldhuijzen, A. E. , Horst, H. E. , Scheltens, P. , Smit, F. , & Hout, H. P. J. (2015). The two‐year incidence of depression and anxiety disorders in spousal caregivers of persons with dementia: Who is at the greatest risk? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(3), 293–303. 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karraker, A. , & Latham, K. (2015). In sickness and in health? Physical illness as a risk factor for marital dissolution in later life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56(3), 420–435. 10.1177/0022146515596354 https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. , Xu, Y. , Zhou, H. , & Loke, A. Y. (2015). Testing a Preliminary Live with Love Conceptual Framework for cancer couple dyads: A mixed‐methods study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(6), 619–628. 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, S. , Carstensen, K. , Jørgensen, C. R. , & Nielsen, C. P. (2017). Stroke patients’ and informal carers’ experiences with life after stroke: An overview of qualitative systematic reviews. Disability & Rehabilitation, 39(3), 301–313. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1140836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, A. , & Greenwood, N. (2012). Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(17), 1413–1422. 10.3109/09638288.2011.650307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire, L. M. , Schulz, R. , Keefe, F. J. , Rudy, T. E. , & Starz, T. W. (2007). Couple‐oriented education and support intervention: Effects on individuals with osteoarthritis and their spouses. Rehabilitation Psychology, 52(2), 121–132. 10.1037/0090-5550.52.2.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M. J. , & Bauer, E. (2015). In sickness and in health: Couples coping with stroke across the life span. Health & Social Work, 40(3), 92–100. 10.1093/hsw/hlv043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M. J. , & Lyons, K. S. (2015). Incongruence between stroke survivor and spouse perceptions of survivor functioning and effects on spouse mental health: A mixed‐methods pilot study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(1), 46–54. 10.1080/13607863.2014.913551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald, S. K. , Bernal, M. P. , Cron, S. G. , & Godwin, K. M. (2009). Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 16(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/ 10.1310/tsr1602‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S. , & Palmer, J. B. (2011). When your spouse has a stroke: Caring for your partner, yourself and your relationship. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peoples, H. , Satink, T. , & Steultjens, E. (2011). Stroke survivors' experiences of rehabilitation: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 18(3), 163–171. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson, J. , Ferraz‐Nunes, J. , & Karlberg, I. (2012). Economic burden of stroke in a large county in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 341 10.1186/1472-6963-12-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, K. , Murray, C. D. , & Malone, C. (2014). The experience of couples when one partner has a stroke at a young age: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36, 1670–1678. 10.3109/09638288.2013.866699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, H. , Gubitz, G. , & Phillips, S. (2009). A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. International Journal of Stroke, 4(4), 285–292. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochette, A. , Bravo, G. , Desrosiers, J. , St‐Cyr Tribble, D. , & Bourget, A. (2007). Adaptation process, participation and depression over six months in first‐stroke individuals and spouses. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(6), 554–562. 10.1177/0269215507073490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubbens, E. , Clerck, L. D. , & Swinnen, E. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions to decrease the physical and mental burden and strain of informal caregivers of stroke patients: A systematic review. Converging Clinical and Engineering Research on Neurorehabilitation II, Biosystems & Biorobotics, 15, 299–303. 10.1007/978-3-319-46669-9_51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satink, T. , Cup, E. H. C. , De Swart, B. J. M. , & Sanden, M. W. G. N. (2018). The perspectives of spouses of stroke survivors on self‐management – a focus group study. Disability & Rehabilitation, 40(2), 176–184. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1247920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singapore National Stroke Association (2017). Understanding Stroke: A Guide for Stroke Survivors and Their Families. Available at: http://www.snsa.org.sg/understanding-stroke-a-guide-for-stroke-survivors-and-their-families/ accessed 28 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M. , Davidson, K. , Meade, D. , Hirth, A. , & Weld‐Viscount, P. (2001). Group support for couples coping with a cardiac condition. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(2), 190–199. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2001.01652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taule, T. , & Råheim, M. (2014). Life changed existentially: a qualitative study of experiences at 6–8 months after mild stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(25), 2107–2119. 10.3109/09638288.2014.904448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, H. S. , & Ryan, A. (2009). The impact of stroke consequences on spousal relationships from the perspective of the person with stroke. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(12), 1803–1811. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooth, L. , McKenna, K. , Barnett, A. , Prescott, C. , & Murphy, S. (2005). Caregiver burden, time spent caring and health status in the first 12 months following stroke. Brain Injury, 19, 963–974. 10.1080/02699050500110785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traa, M. J. , De Vries, J. , Bodenmann, G. , & Den Oudsten, B. L. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: A systematic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 85–114. 10.1111/bjhp.12094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Exel, N. J. , Koopmanschap, M. A. , van den Berg, B. , Brouwer, W. B. , & van den Bos, G. A. (2005). Burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients. Identification of caregivers at risk of adverse health effects. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 19, 11–17. 10.1159/000081906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser‐Meily, A. , Post, M. , Port, V. I. , Maas, C. , Forstberg‐Wärleby, G. , & Lindeman, E. (2009). Psychosocial functioning of spouses of patients with stroke from initial inpatient rehabilitation to 3 years poststroke: Course and relations with coping strategies. Stroke, 40(4), 1399–1404. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser‐Meily, A. , Post, M. , van de Port, I. , van Heugten, C. , & van den Bos, T. (2008). Psychosocial functioning of spouses in the chronic phase after stroke: Improvement or deterioration between 1 and 3 years after stroke? Patient Education and Counseling, 73(1), 153–158. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. , Thompson, D. R. , Chair, S. Y. , & Twinn, S. (2008). Chinese couples’ experiences during convalescence from a first heart attack: A focus group study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61(3), 307–315. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2018). Facts and figures. Available at: http://www.worldstrokecampaign.org/learn/facts-and-figures.html accessed 24 August 201. [Google Scholar]