Abstract

Background

Many patients use opioids chronically before surgery; it is unclear if surgery alters the likelihood of ongoing opioid consumption in these patients.

Methods

We performed a population-based matched cohort study of adults in Ontario, Canada undergoing one of 16 non-orthopaedic surgical procedures and who were chronically using opioids, defined as (1) an opioid prescription that overlapped the index date and (2) either a total of 120 or more cumulative calendar days of filled opioid prescriptions, or 10 or more prescriptions filled in the prior year. Each surgical patient was matched based on age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and daily preoperative opioid dose to three non-surgical patients who were also chronic opioid users. The primary outcome was time to opioid discontinuation.

Results

The cohort included 4755 surgical and 14 265 matched non-surgical patients. After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities, surgery was associated with an increased likelihood of opioid discontinuation (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27, 1.42). Among surgical patients, factors associated with a reduced odds of discontinuation included a mean preoperative opioid dose above 90 morphine milligram equivalents (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.32, 0.49) or filling a prescription for oxycodone (aOR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.56, 0.98). Receipt of an in-patient Acute Pain Service consultation (aOR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.69) or residing in the highest neighbourhood income quintile (aOR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.79) were associated with a greater odds of opioid discontinuation.

Conclusions

For chronic opioid users, surgery was associated with an increased likelihood of discontinuation of opioids in the following year compared with non-surgical chronic opioid users.

Keywords: analgesics, chronic opioid therapy, opioid discontinuation, opioid prescription, prescription, surgery

Editor's key points.

-

•

There has been concern that continued opioid prescribing after surgery may contribute to increased risk of long-term use. For patients on opioids before operation, the effect of surgery on the likelihood of continuing on long-term opioids is not known.

-

•

This matched cohort study of >18 000 patients found that undergoing surgery (36.6%) compared with no surgery (29%) was associated with an increased chance of stopping opioid use within 1 year.

-

•

Factors associated with a decreased chance of stopping included higher daily morphine equivalent doses before operation and oxycodone use, while input from an acute pain service was associated with an increased chance of stopping.

-

•

Further work to explore these factors may be useful in developing interventions to support opioid discontinuation.

Perioperative use of opioids is now a global concern, but the majority of this focus has been on postoperative prescribing.1 North Americans consume two-thirds of opioids globally, achieving the highest per capita prescribing in the world as of 2014.2 As a result, a significant proportion of patients presenting for surgery may have a history of prescription opioid use.3, 4, 5

While many studies have investigated the association between preoperative opioid use and postoperative morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilisation,6, 7, 8, 9, 10 major evidence gaps still persist. For instance, it is unknown whether surgery alters the trajectory of ongoing opioid consumption among chronic opioid users over the longer term. Surgical patients may be more likely to discontinue opioids if surgery treated their chronic pain or provided an opportunity for health practitioners to coordinate efforts to reduce opioid use. Conversely, it is conceivable that an acute, painful event, such as surgery, may lead to continued chronic opioid use. This may be because of excess opioid prescribing in the perioperative period11,12 or a reduced tolerance to poorly controlled surgical pain in chronic opioid users.13

We therefore sought to determine the prevalence of chronic opioid use at the time of surgery, and to assess the relationship between surgery and opioid discontinuation in the year after surgery among chronic opioid users. We evaluated chronic opioid users undergoing surgical procedures not primarily indicated to reduce chronic pain and hypothesised that these patients were less likely to discontinue opioids in the year of follow-up compared with chronic opioid users in the general population. Finally, we sought to identify factors associated with opioid discontinuation among surgical patients.

Methods

Study design and data sources

After approval by Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), we performed a population-based, matched, retrospective cohort study using linked health administrative data at ICES in Ontario, Canada. For details of datasets and their validation, see Supplementary Methods. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES. All Ontario residents, approximately 14 million individuals, obtain their healthcare services from a single payer and provider. Each individual is assigned a unique health card number which is captured in administrative databases at all healthcare encounters. Encrypted into a unique encoded identifier to maintain patient privacy, the health card number permits linkage deterministically across provincial and national health administrative databases. These databases have high linkage rates, little missing information, and are regularly used in health services research.14, 15, 16

Exposure definition

Surgical patient cohort

The exposed surgical cohort was defined as patients undergoing one of 18 surgical procedures between July 1, 2013 and March 31, 2016 (see Supplementary Table S1 for surgical procedures). These procedures were chosen as they are frequently performed17 and they have been previously used to evaluate postoperative opioid consumption in opioid-naïve patients.18 Orthopaedic procedures were excluded as these often have treatment pathways that include rehabilitation and pain management. This list was ultimately reduced to 16 procedures because of small numbers of patients undergoing open gastric bypass repair and gastroesophageal reflux surgery. The index date for surgical patients was defined as the date of admission (inpatient surgery) or the date of surgery (outpatient surgery). A look-back window of 1 yr before the index date was used to evaluate opioid use, and to identify baseline and clinical characteristics.

We restricted the cohort to chronic opioid users who were at least 18 yr of age. Chronic opioid use was defined as having been done previously as (1) an opioid prescription that overlaps the index date and (2) either a total of 120 or more cumulative calendar days of filled opioid prescriptions or 10 or more prescriptions filled in the year before surgery.19,20 Oral formulations, buccal strips, and transdermal patches of the most commonly prescribed outpatient opioids were included.21

We excluded patients if they had any surgical procedure in the year before the index date, or were dispensed methadone or buprenorphine in the year before the index date, as these are often used in the management of opioid use disorder.22 Patients were also excluded if they received palliative care in the year before the index date, as their opioid use may be for end-of-life care.23

Comparison cohort

We assembled a cohort of non-surgical chronic opioid users to measure the natural rate of opioid discontinuation in the general population that may occur because of pain resolution, the side-effect profile of opioids, patient concerns about opioid use disorder, or physician intervention.24

Patients in this comparison cohort were first identified by having been dispensed at least one eligible opioid in the recruitment period. Consistent with previous research,18,25 we then randomly assigned an index date within the recruitment period that matched the distribution of index dates for the surgical cohort. Next, we restricted this cohort to patients who met the same definition of chronic opioid use as with our surgical patient cohort and did not have a surgical procedure in the year before this index date. Both surgical and non-surgical patients had to meet the same exclusion criteria.

To mitigate differences between the two groups, surgical patients were then matched to three non-surgical patients on sex, age (within 5 yr), Charlson comorbidity score (four categories: no hospitalisations, 0, 1, or ≥2), and mean daily opioid dose category (>0–25, 26–50, 51–75, 76–100, 100–1000, >1000 morphine milligram equivalents; MMEs) on the day before the index date, using greedy nearest neighbour matching.26 MMEs were calculated using methods described previously.27, 28, 29 Although matched analyses may force the analysis of a non-representative sample, they enabled us to compare patients with similar characteristics who were likely to be eligible for surgery. We chose to include a higher number of non-surgical patients to improve the precision of our estimates; however, we limited the number of non-surgical patients to three to minimise the risk of matching each surgical patient to increasingly dissimilar controls.30

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the time to discontinuation of opioids. We defined discontinuation as the greater of the following two options: (1) opioid-free for twice the duration of the previous prescription or (2) a minimum grace period of 30 opioid-free days. We calculated time to discontinuation as the number of days from the start of the follow-up period to the last day of the last opioid prescription dispensed before discontinuation. The start of the follow-up period was defined as one of: (1) the date of discharge from index hospitalisation (inpatient surgery), (2) the date of surgery (outpatient surgery), or (3) the index date (non-surgical cohort).

As a secondary analysis, we sought to identify factors associated with opioid discontinuation at any point in the year after surgery. Therefore, the outcome of interest was a binary outcome of discontinuation of opioids at any time in the year, as defined above.

While we excluded patients prescribed methadone or buprenorphine before the index date, prescriptions for these medications in the follow-up period were included, as this prevented misclassification of these patients as having discontinued opioids. Similarly, to ensure that patients with leftover opioids from a prescription dispensed before the index date were not misclassified as having discontinued, the last pre-index date prescription for each patient was evaluated. Patients were given the longer of (1) their remaining days supplied or (2) 30 days to fill their first prescription after operation. For details, see Supplementary Figure S1.

Other covariates and risk factors for continued opioid use

Risk factors for continued chronic opioid use were included based on both biologic plausibility and previous literature.31, 32, 33, 34 For details, see Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of surgical and non-surgical groups before and after matching using standardised differences, which, relative to tests of significance, are often less sensitive to large sample sizes.35 We considered a standardised difference of greater than 0.10 to represent a meaningful covariate imbalance between two groups.35 As less than 0.1% of patients had missing data, complete case analyses were performed for all comparisons.

We compared the time to discontinuation of opioids between the surgical and non-surgical groups using a Kaplan–Meier model. We used Cox proportional hazards regression modelling to estimate the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for time to discontinuation of opioids within the year after the index date. To account for the correlation within matched groups, we used a marginal Cox model with robust sandwich covariance matrix, adjusting for covariates.36,37 Patients were right censored at the earlier of death, at 365 days of follow-up, or at the end of the study follow-up period set as March 31, 2017. We included the following patient characteristics in each model: rural status, neighbourhood income quintile, number of physician claims in the year before the index date, Ontario Marginalization Index, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and preoperative benzodiazepine use. As patients were matched on age, sex, Charlson comorbidity category, and preoperative opioid dose category, these were not included in the model.38,39 We then stratified, by surgery type, where patients undergoing the procedure and only their matched controls were included in the model. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using a time-dependent exposure covariate and by inspection of log-log survival curves. Finally, we calculated the aHR for opioid discontinuation in surgical vs non-surgical patients for each consecutive 30-day period in the year of follow-up.

As a secondary analysis, we examined the association between specific factors and opioid discontinuation after surgery. We performed a regression using generalised estimating equation models with a binomial distribution and logit link function on the surgical cohort alone (without the comparison cohort). These models allowed estimation of the odds of discontinuation within the year after surgery, accounting for hospital-level clustering. While controlling for the variables in Table 1, we evaluated specific risk factors including: age (>65 yr), sex, neighbourhood income quintile, rural dwelling, preoperative benzodiazepine use, surgery type, primary opioid type, receipt of an acute pain services consultation, teaching hospital status, and opioid dose on the day before surgery. These covariates were chosen because they have been shown to be associated with either chronic opioid use or opioid discontinuation.31, 32, 33, 34

Table 1.

Characteristics of surgical and non-surgical cohorts before and after matching.

| Overall cohort |

Matched cohort |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-surgical N=158 475 |

Surgical N=4755 |

Standardised difference | Non-surgical N=14 265 |

Surgical N=4755 |

Standardised difference | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 58 (50-70) | 55 (46-64) | 0.29 | 55 (46-64) | 55 (46-64) | 0 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 85 793 (54.1) | 3207 (67.4) | 0.28 | 9621 (67.4) | 3207 (67.4) | 0 |

| Charlson category,∗n (%) | ||||||

| No hospitalisation | 106 032 (66.9) | 3036 (63.8) | 0.06 | 9108 (63.8) | 3036 (63.8) | 0 |

| 0 | 26 493 (16.7) | 1013 (21.3) | 0.12 | 3039 (21.3) | 1013 (21.3) | 0 |

| 1 | 11 868 (7.5) | 366 (7.7) | 0.01 | 1098 (7.7) | 366 (7.7) | 0 |

| ≥2 | 14 082 (8.9) | 340 (7.2) | 0.06 | 1020 (7.2) | 340 (7.2) | 0 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6774 (4.3) | 217 (4.6) | 0.01 | 648 (4.5) | 217 (4.6) | 0 |

| Asthma | 16 500 (10.4) | 581 (12.2) | 0.06 | 1616 (11.3) | 581 (12.2) | 0.03 |

| Cancer diagnosis | 13 942 (8.8) | 406 (8.5) | 0.01 | 1065 (7.5) | 406 (8.5) | 0.04 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11 255 (7.1) | 219 (4.6) | 0.11 | 711 (5.0) | 219 (4.6) | 0.02 |

| COPD | 44 255 (27.9) | 1193 (25.1) | 0.06 | 3799 (26.6) | 1193 (25.1) | 0.04 |

| Dementia | 11 863 (7.5) | 85 (1.8) | 0.27 | 506 (3.5) | 85 (1.8) | 0.11 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 090 (25.9) | 1269 (26.7) | 0.02 | 3426 (24.0) | 1269 (26.7) | 0.06 |

| Hypertension | 83 526 (52.7) | 2442 (51.4) | 0.03 | 6580 (46.1) | 2442 (51.4) | 0.1 |

| Prior myocardial infarct | 6537 (4.1) | 103 (2.2) | 0.11 | 432 (3.0) | 103 (2.2) | 0.05 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 42 265 (26.7) | 1520 (32.0) | 0.12 | 4425 (31.0) | 1520 (32.0) | 0.02 |

| Physician service claims,† median (IQR) | 37 (19–65) | 51 (31–80) | 0.43 | 36 (18–61) | 51 (31–80) | 0.47 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile, n (%) | ||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 43 301 (27.3) | 1235 (26.0) | 0.03 | 4084 (28.6) | 1235 (26.0) | 0.06 |

| 2 | 35 137 (22.2) | 1002 (21.1) | 0.03 | 3253 (22.8) | 1,002 (21.1) | 0.04 |

| 3 | 30 765 (19.4) | 1020 (21.5) | 0.05 | 2700 (18.9) | 1020 (21.5) | 0.06 |

| 4 | 27 454 (17.3) | 808 (17.0) | 0.01 | 2411 (16.9) | 808 (17.0) | 0 |

| 5 (highest) | 21 818 (13.8) | 690 (14.5) | 0.02 | 1817 (12.7) | 690 (14.5) | 0.05 |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 25 661 (16.2) | 834 (17.5) | 0.04 | 2286 (16.0) | 834 (17.5) | 0.04 |

| Ontario Marginalization Index,‡ median (IQR) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 0.12 | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 0.10 |

| Preoperative drug use,¶n (%) | ||||||

| Barbiturate | 492 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | 0.01 | 41 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | 0.01 |

| Benzodiazepine | 57 060 (36.0) | 1837 (38.6) | 0.05 | 5517 (38.7) | 1837 (38.6) | 0 |

| Pre-operative diagnosis,§n (%) | ||||||

| Opioid overdose | 49 (0.0) | ≤5 | 0.01 | ≤5 | ≤5 | 0.01 |

| Non-opioid overdose | 98 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 0.03 | 10 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 0.02 |

| Preoperative opioid dose (MME),||n (%) | ||||||

| 0–25 | 61 273 (38.7) | 1719 (36.2) | 0.05 | 5157 (36.2) | 1719 (36.2) | 0 |

| 25–50 | 37 846 (23.9) | 1185 (24.9) | 0.02 | 3555 (24.9) | 1185 (24.9) | 0 |

| 50–75 | 15 036 (9.5) | 524 (11.0) | 0.05 | 1572 (11.0) | 524 (11.0) | 0 |

| 75–100 | 8576 (5.4) | 253 (5.3) | 0 | 759 (5.3) | 253 (5.3) | 0 |

| 100–1000 | 34 525 (21.8) | 1039 (21.9) | 0 | 3130 (21.9) | 1039 (21.9) | 0 |

| >1000 | 1219 (0.8) | 35 (0.7) | 0 | 92 (0.6) | 35 (0.7) | 0.01 |

| Primary opioid medication,#n (%) | ||||||

| Codeine | 40 801 (25.7) | 1116 (23.5) | 0.05 | 3523 (24.7) | 1116 (23.5) | 0.03 |

| Fentanyl | 11 467 (7.2) | 323 (6.8) | 0.02 | 910 (6.4) | 323 (6.8) | 0.02 |

| Hydromorphone | 22 434 (14.2) | 530 (11.1) | 0.09 | 1892 (13.3) | 530 (11.1) | 0.06 |

| Meperidine | 387 (0.2) | 17 (0.4) | 0.02 | 38 (0.3) | 17 (0.4) | 0.02 |

| Morphine | 12 044 (7.6) | 404 (8.5) | 0.03 | 1104 (7.7) | 404 (8.5) | 0.03 |

| Oxycodone | 60 928 (38.4) | 1967 (41.4) | 0 | 5757 (40.4) | 1967 (41.4) | 0.02 |

| Tramadol | 9800 (6.2) | 375 (7.9) | 0.07 | 994 (7.0) | 375 (7.9) | 0.04 |

| Cough medication∗∗ | 614 (0.4) | 23 (0.5) | 0.01 | 47 (0.3) | 23 (0.5) | 0.02 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MME, morphine milligram equivalent.

Deyo Method,66 a 5-yr lookback period from the index date was used to calculate the Charlson score.

Defined as the number of Ontario Health Insurance Plan claims where a physician billing code was used in the year before the index date.

Defined by Matheson and colleagues.67

Defined as one or more prescription(s) filled in the year before the index date.

A 1-yr lookback period was used to identify overdoses.

Defined as the average daily dose (MME) of all prescriptions overlapping the day before the index date.

Defined as the medication contributing the greatest proportion of the average daily MME dose on the day before surgery.

Defined as medications primarily used as antitussives and which most commonly contain either hydrocodone or codeine.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed multiple sensitivity analyses to evaluate the effect of matching, and the potential misclassification of patients with our outcome definitions of time to opioid discontinuation and opioid discontinuation in the year after surgery. For details, see Supplementary Methods.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software (Enterprise Edition, Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 152 462 surgical patients who had one of 16 surgical procedures, 4755 (3.1%) were chronic opioid users before surgery (Table 1). These patients were matched to 14 265 non-surgical patients with chronic opioid use (see Supplementary Fig. S2 for flow diagram).

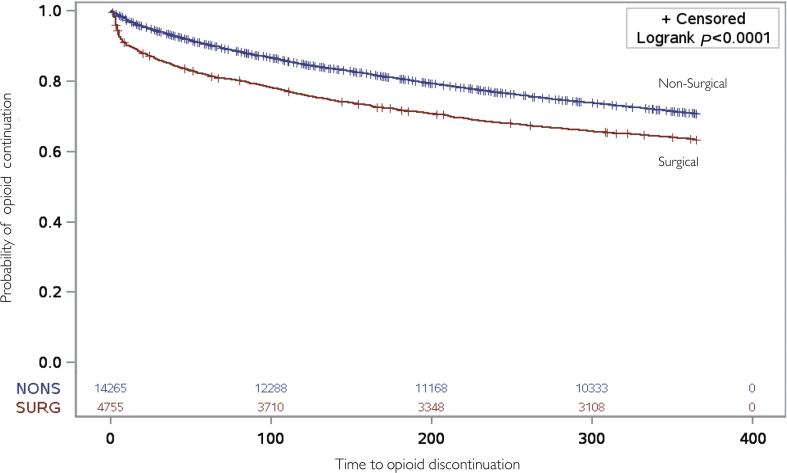

Rates of discontinuation of opioids

Overall, surgical patients (36.6%) were more likely than non-surgical individuals (29.0%) to discontinue opioids within 1 yr of follow-up (Fig. 1; unadjusted HR: 1.38; 95% CI 1.30, 1.46); this difference remained significant after adjustment for available covariates (aHR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.27, 1.42, see Supplementary Table S2 for full model). The results remained qualitatively unchanged after multiple sensitivity analyses (Table 2). Relative to their matched non-surgical controls in analyses restricted to specific procedures, patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (aHR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.28, 1.64), varicose vein stripping (aHR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.08, 2.38), laparoscopic gastric bypass (aHR: 2.03; 95% CI: 1.63, 2.52), carpal tunnel release (aHR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.37), hysterectomy (aHR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.24, 1.64), and laparoscopic colectomy (aHR: 1.97; 95% CI: 1.44, 2.70) were more likely to discontinue opioids during the follow-up period (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves depicting time-to-discontinuation of opioids. Survival curves represent time to discontinuation of opioids in the surgical (red) and non-surgical (blue) groups. Listed at the bottom of the figure are the number susceptible for discontinuation of opioids in the surgical (SURG) and non-surgical (NONS) groups.

Table 2.

Adjusted association between surgery and time to discontinuation, including sensitivity analyses.

| Total surgical patients, n | Surgical patients discontinued, n (%) | Total non-surgical individuals, n | Non-surgical individuals discontinued, n (%) | Adjusted hazard ratio for surgery (95% CI)∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (matched cohort) analysis† | 4755 | 1738 (36.5) | 14 265 | 4137 (29.0) | 1.34 (1.27, 1.42) |

| Unmatched cohort analysis‡ | 4755 | 1738 (36.5) | 158 475 | 46 948 (29.6) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) |

| 90-day definition of opioid discontinuation¶ | 4755 | 803 (16.9) | 14 265 | 1953 (13.6) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.36) |

| Length of hospital stay <7 days§ | 4537 | 1635 (36.0) | 13 611 | 3918 (28.8) | 1.22 (1.12, 1.33) |

CI, confidence interval.

All models control for the number of physicians seen in the year before the index date, a composite measure of marginalisation, neighbourhood income quintile, rural residence, and all comorbidities listed in Table 1. The Unmatched Cohort Analysis also includes variables for age, sex, Charlson comorbidity category, and average opioid dose on the day before the index date.

The entire surgical cohort relative to the matched non-surgical patients. Clustering within matched groups was accounted for in adjusted analysis. Complete model data are available in Supplementary Table S2.

The entire surgical cohort relative to all non-surgical patients.

Changing the primary outcome (discontinuation) to allow for a minimum grace period of 90 opioid-free days. Clustering within matched groups was accounted for in this adjusted analysis.

Including only surgical patients with hospital length of stay of less than 7 days and their matched controls. Clustering within matched groups was accounted for in adjusted analysis.

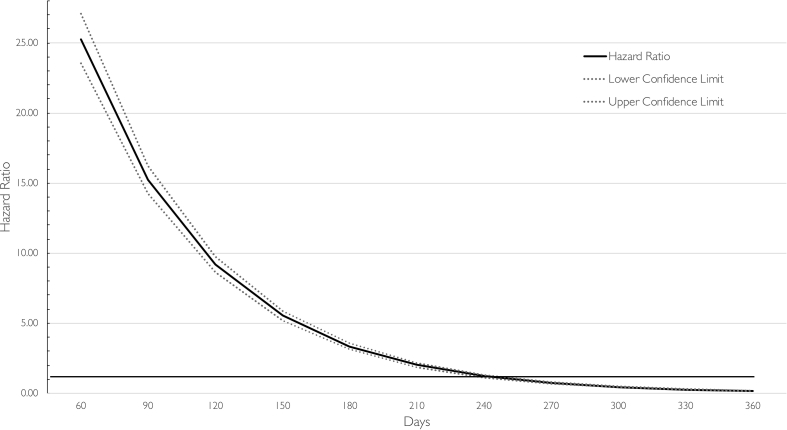

The association between surgery and opioid discontinuation varied significantly by time (Fig. 2; time-dependent covariate P-value: P<0.001). Surgery was associated with the greatest hazard of discontinuation at Day 60 (aHR: 25.1; 95% CI 23.4, 26.9). After Day 270, surgical patients who continued to be prescribed opioids were less likely to discontinue opioids than those in the general population (aHR: 0.73; 95% CI 0.67, 0.79; see Supplementary Table S3 for full table).

Fig 2.

Stratified hazard ratio (solid line) and 95% point-wise confidence bands (dashed lines) for time-to-discontinuation of opioids in surgical vs non-surgical patients per 30 days. The horizontal line at 1 indicates no difference in likelihood of opioid discontinuation.

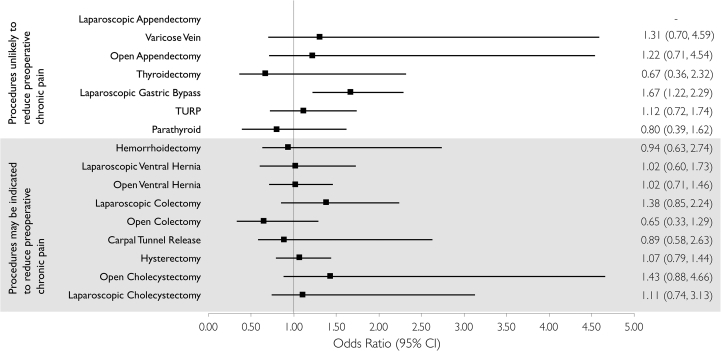

Factors associated with opioid discontinuation among surgical patients

Relative to laparoscopic appendectomy, laparoscopic gastric bypass was the only procedure associated with increased odds of opioid discontinuation within 1 yr of follow-up (aOR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.19, 2.23; Fig. 3 and Table 3). Of patient factors assessed, opioid dose on the day before the index date had the strongest association with discontinuation, with high opioid dose (>90 MME) associated with lower odds (aOR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.31, 0.49) (Table 3). While sex was not associated with opioid discontinuation (aOR: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.97, 1.26), age >65 yr was associated with increased odds of discontinuation (aOR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.19, 1.68). Relative to morphine, oxycodone dispensed on the day before surgery was associated with a lower likelihood of discontinuation (aOR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.98), while a prescription for codeine (aOR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.33, 2.49), tramadol (aOR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.58, 3.41), or cough-related medications (aOR 4.44; 95% CI: 1.76, 11.19) were associated with greater odds of discontinuation. The majority of measured comorbidities were not associated with opioid cessation; however, a diagnosis of COPD (aOR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.64, 0.88) or dementia (aOR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.91) was associated with reduced odds of discontinuation. Relative to individuals in the lowest neighbourhood income quintile, those in the highest (aOR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.79) and second highest income quintiles (aOR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.14, 1.76) were more likely to discontinue opioids. Finally, receipt of an inpatient Acute Pain Service consult was associated with increased odds of discontinuation (aOR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.69). The results remained qualitatively similar after excluding the 70 (1.5%) surgical patients who died within the year of follow-up (see Supplementary Table S4 for full model).

Fig 3.

Adjusted analyses evaluating the association between surgery type and discontinuation of opioids in the year after discharge among chronic opioid users in Ontario. CI, confidence interval; TURP, transurethral resection of prostate.

Table 3.

Adjusted analyses evaluating the association between patient and hospital characteristics and discontinuation of opioids in the year after discharge from surgery among surgical chronic opioid users in Ontario (n=4755).

| Adjusted analysis∗ |

||

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Surgery type | ||

| Laparoscopic appendectomy | – | |

| Varicose vein | 1.30 (0.73, 2.31) | 0.37 |

| Open cholecystectomy | 1.34 (0.72, 2.52) | 0.36 |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 1.09 (0.82, 1.45) | 0.54 |

| Open appendectomy | 1.20 (0.67, 2.16) | 0.54 |

| Haemorrhoidectomy | 0.94 (0.67, 1.34) | 0.74 |

| Thyroidectomy | 0.66 (0.36, 1.23) | 0.19 |

| Carpal tunnel release | 0.90 (0.67, 1.20) | 0.45 |

| Hysterectomy | 1.05 (0.78, 1.42) | 0.73 |

| Laparoscopic colectomy | 1.18 (0.75, 1.85) | 0.48 |

| Open colectomy | 0.60 (0.31, 1.16) | 0.12 |

| Laparoscopic ventral hernia | 1.02 (0.60, 1.71) | 0.95 |

| Open ventral hernia | 0.99 (0.70, 1.42) | 0.97 |

| Laparoscopic gastric bypass | 1.63 (1.19, 2.23) | 0.002 |

| TURP | 1.10 (0.71, 1.71) | 0.66 |

| Parathyroid | 0.73 (0.36, 1.49) | 0.38 |

| Age >65 yr | 1.42 (1.19, 1.68) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.11 (0.97, 1.26) | 0.119 |

| Charlson category† ≥2 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.18) | 0.18 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.25 (0.90, 1.73) | 0.19 |

| Asthma | 1.15 (0.95, 1.40) | 0.16 |

| Cancer diagnosis | 1.09 (0.86, 1.38) | 0.50 |

| Heart failure | 0.85 (0.59, 1.22) | 0.39 |

| COPD | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 0.58 (0.37, 0.91) | 0.019 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) | 0.129 |

| Hypertension | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) | 0.62 |

| Prior myocardial infarct | 1.02 (0.67, 1.56) | 0.91 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 1.06 (0.93, 1.22) | 0.38 |

| Specialist visits‡ | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.007 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||

| 1 (lowest) | – | |

| 2 | 1.10 (0.90, 1.33) | 0.35 |

| 3 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | 0.83 |

| 4 | 1.41 (1.14, 1.76) | <0.001 |

| 5 (highest) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76) | 0.024 |

| Ontario marginalization index¶ | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.49 |

| Rural residence | 1.03 (0.89, 1.20) | 0.66 |

| Preoperative drug use§ | ||

| Benzodiazepine | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.61 |

| Preoperative opioid dose|| | ||

| >90 MME | 0.39 (0.31, 0.49) | <0.001 |

| Primary opioid medication# | ||

| Morphine | – | |

| Oxycodone | 0.74 (0.55, 0.98) | 0.041 |

| Fentanyl | 1.37 (0.93, 2.03) | 0.112 |

| Hydromorphone | 1.16 (0.86, 1.58) | 0.33 |

| Codeine | 1.82 (1.33, 2.49) | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | 2.32 (1.58, 3.41) | <0.001 |

| Cough medication∗∗ | 4.44 (1.76, 11.20) | 0.002 |

| Meperidine | 1.92 (0.64, 5.78) | 0.25 |

| Length of stay >7 days | 1.27 (0.92, 1.77) | 0.15 |

| Year of surgery | ||

| 2013 | – | |

| 2014 | 1.19 (0.99, 1.43) | 0.059 |

| 2015 | 0.99 (0.83, 1.19) | 0.95 |

| 2016 | 1.18 (0.93, 1.50) | 0.180 |

| Acute pain services during hospitalisation | 1.34 (1.06, 1.70) | 0.011 |

| Teaching hospital | 1.12 (0.96, 1.31) | 0.142 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; SD, standard deviation; TURP, transurethral resection of prostate.

Generalised estimating equations evaluated the association between specific variables and discontinuation of opioids in the year of discharge from surgery among chronic opioid users in Ontario, while accounting for hospital-level clustering. The dependent variable was discontinuation within 1 year of follow-up.

Deyo Method,66 a5-year lookback period from the index date was used to calculate the Charlson score.

Defined as the number of visits where a specialist billing code was used in the year before the index date.

Defined by Matheson and colleagues.67

Defined as one or more prescription(s) filled in the year before the index date.

Defined as the average daily dose (MME) of all prescriptions overlapping the day before the index date.

Defined as the medication contributing the greatest proportion of the average daily MME dose on the day before surgery.

Defined as medications primarily used as antitussives and most commonly contain either hydrocodone or codeine.

Discussion

Relative to a control group of non-surgical chronic opioid users, we found that chronic opioid users undergoing surgery were more likely to discontinue opioids, with a shorter time to discontinuation, in the year of follow-up. This increased likelihood of discontinuation was restricted to the early period after surgery. Surgical patients who were susceptible to discontinue opioids may have done so within 270 days after surgery.40 After this point, the remaining surgical patients were less likely to discontinue opioids than those in the general population.

These findings were contrary to our hypothesis that surgical patients would be less likely than non-surgical individuals to discontinue opioids for the entire follow-up period. The increased likelihood of opioid discontinuation early after surgery may be attributable to a variety of factors. Similar to other chronic diseases, such as smoking cessation,41 it is possible that surgery represents an acute life-altering event, where a variety of interventions happen that may encourage discontinuation or treatment compliance. A recent study identified that discontinuation is almost always driven by physicians.24 Although this requires further investigation, it is possible that the perioperative period provides an opportunity for physicians to facilitate opioid discontinuation. Indeed, the association between receipt of acute pain services and discontinuation may be a marker of better teaching with respect to opioid management. Many physicians could be part of a team in this perioperative period, including the surgeon, anaesthesiologist, or pain specialist; while anaesthesiology societies have advocated for a larger role in the perioperative care of patients,42 the best model of caregivers to facilitate interventions and teaching remains to be elucidated.

The procedures we chose were similar to those described by Brummett and colleagues18 in their evaluation of opioid use after surgery among opioid-naïve patients. They demonstrated that the rate of new persistent opioid use was largely similar between minor and major surgery (6.5% and 5.9%, respectively). Our findings and those of Brummett and colleagues18 highlight that perhaps opioid consumption after surgery may not be the consequence of the severity of surgery. Indeed, if this were the case then major surgical procedures, which are often considered more painful, would be associated with a lower rate of opioid discontinuation. However, relative to laparoscopic appendectomy, only laparoscopic gastric bypass was associated with discontinuation of opioids in our adjusted analysis of surgical patients. Similarly, while surgical patients may be discontinuing opioids because surgery provided relief from pain, patients who had procedures that may be indicated to reduce pain, such as carpal tunnel release or haemorrhoidectomy, were just as likely to discontinue opioids as those with other surgical presentations.

We identified the characteristics of patients at high risk for continuing opioids in the year after surgery. Among comorbidities, COPD and dementia were strongly associated with continued opioid use. In Ontario, more than 70% of older patients with COPD use opioids for chronic muscle pain, insomnia, or persistent cough,43 despite being associated with severe respiratory44 and cardiac45 morbidity and mortality. In Denmark, opioid use was notably higher in older patients with dementia when compared with older patients without dementia,46 as opioids may be used for end-of-life-care or to treat behavioural symptoms in this population.47 The development of multidisciplinary programs, such as a transitional pain service, to manage the biopsychosocial aspects of chronic pain after surgery, may help to address the postoperative needs of high-risk patients.48, 49, 50 We also found that preoperative opioid dose was the strongest predictor of opioid discontinuation in the year after surgery. An interdisciplinary approach to preoperative opioid reduction has been proposed, which addresses both the high burden of physical and mental illness in this population.51 Moreover, relative to morphine, patients primarily filling prescriptions for oxycodone were less likely to discontinue opioids. Oxycodone may be more amenable to opioid abuse because of a low subjective side-effect profile and high likeability, defined as positive subjective psychoactive effects.52 We also identified that patients residing in lower neighbourhood income quintiles were less likely to discontinue opioids. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating the concentration of the opioid epidemic in low-income areas, and the high associated rate of opioid-related harm in this population.53,54 As such, when planning future opioid-related public health interventions, policymakers should take into consideration health inequities. Finally, the receipt of acute pain services may be associated with an increased likelihood of discontinuation. Although nerve blockade may not be associated with a reduced likelihood of chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total knee5 or shoulder4 arthroplasty, a multifaceted approach to opioid management that involves bundled care pathways, patient and provider education, or hospital-specific prescribing guidelines, have shown promise in opioid-naïve populations.55, 56, 57, 58

This study builds on the current literature in several ways. While the incidence of chronic or persistent opioid use after surgery among opioid-naïve patients has been extensively addressed,18,25,32,59,60 this study provides key information on opioid use after surgery among the chronic opioid use population. Furthermore, the research that has been performed in chronic opioid users presenting for surgery has been limited to specific populations in the USA such as veterans, or those who are insured by specific insurance plans.61,62 This study included all patients in a large Canadian population, irrespective of age or insurance status. Similarly, previous studies that evaluated opioid discontinuation in surgical cohorts typically have not considered the baseline likelihood of opioid discontinuation in the general population.61, 62, 63 We were able to address this issue and use non-surgical individuals who use opioids chronically in the general population as a reference group.

This study also has limitations. While we attempted to account for measured differences between the surgical and non-surgical cohorts, we cannot exclude the possibility that the association we describe is the result of unmeasured confounding. For instance, surgical patients may represent a population with greater access to broader healthcare services and, hence, are more likely to be encouraged to discontinue opioids. We used prescription claims data, which are accurate at capturing medication dispensing; however, they cannot capture actual opioid consumption, patient-reported outcomes, pain, or the clinical indication for these prescriptions. There is a rising concern that patients receiving long-term prescription opioid therapy are being forced by physicians to taper their opioids rapidly. This trend may be the result of new tapering guidelines, the growing concern about patients on high-dose opioid therapy, and resulting stigma about patients with opioid use disorder.64 Abrupt discontinuation can lead to severe withdrawal, pain, loss of function, and may also be associated with increased suicide risk in patients who use opioids chronically.65 Our study was unable to determine whether patients were forced to cease opioid consumption abruptly by physicians; however, this would not represent an improvement in patient care.

Conclusions

This population-based matched cohort study found surgery to be associated with a decreased time to discontinuation of opioids among chronic opioid users. Importantly, among surgical patients, oxycodone use, higher opioid dose, COPD, and dementia were associated with reduced odds of discontinuation. Surgery and hospitalisation may offer an opportunity to help work towards discontinuing opioids. Further research is needed to evaluate whether preoperative opioid weaning, in-hospital interventions, or postoperative transitional pain services can influence opioid discontinuation, particularly in high-risk patients.

Authors' contributions

Conceived and designed the study: NJ, DS, TG, JB, DW, HW.

Interpreted the data: NJ, DS, TG, JB, DW, HW: RP.

Acquired, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript: NJ.

Assisted in drafting the manuscript: DS, TG, JB, DW, HW.

Provided statistical review: RP.

Revised the work critically for important intellectual content: all authors.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

National Institutes of Health to HW (R01DA042299). New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Endowed Chair in Translational Anaesthesiology Research at St. Michael’s Hospital and University of Toronto to DNW. Merit Awards from the Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain Medicine at the University of Toronto to DNW and HW. DS holds Operating Grants from the Canadian Institute for Health Research. This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. We thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database.

Handling editor: Lesley Colvin

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Neuman M.D., Bateman B.T., Wunsch H. Inappropriate opioid prescription after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393:1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30428-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tadrous M. Opioids in Ontario: the current state of affairs and a path forward. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11:927–929. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2018.1516142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilliard P.E., Waljee J., Moser S. Prevalence of preoperative opioid use and characteristics associated with opioid use among patients presenting for surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:929–937. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller K.G., Memtsoudis S.G., Mariano E.R., Baker L.C., Mackey S., Sun E.C. Lack of association between the use of nerve blockade and the risk of persistent opioid use among patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty: evidence from the Marketscan database. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1014–1020. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun E.C., Bateman B.T., Memtsoudis S.G., Neuman M.D., Mariano E.R., Baker L.C. Lack of association between the use of nerve blockade and the risk of postoperative chronic opioid use among patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: evidence from the Marketscan database. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:999–1007. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Ari A., Chansky H., Rozet I. Preoperative opioid use is associated with early revision after total knee arthroplasty: a study of male patients treated in the veterans affairs system. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2017;99:1–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cron D.C., Englesbe M.J., Bolton C.J. Preoperative opioid use is independently associated with increased costs and worse outcomes after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265:695–701. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waljee J.F., Cron D.C., Steiger R.M., Zhong L., Englesbe M.J., Brummett C.M. Effect of preoperative opioid exposure on healthcare utilization and expenditures following elective abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265:715–721. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore J.F., Jr., Olleik G., El-Kefraoui C. Preventing opioid prescription after major surgery: a scoping review of opioid-free analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh T.K., Jeon Y.T., Choi J.W. Trends in chronic opioid use and association with five-year survival in South Korea: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shei A., Rice J.B., Kirson N.Y. Sources of prescription opioids among diagnosed opioid abusers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:779–784. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1016607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volkow N.D., McLellan A.T. Opioid abuse in chronic pain--misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1253–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shipton E.A. The transition from acute to chronic post surgical pain. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:824–836. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tu J.V., Chu A., Donovan L.R. The Cardiovascular Health in Ambulatory Care Research Team (CANHEART): using big data to measure and improve cardiovascular health and healthcare services. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcome. 2015;8:204–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juurlink D.N., Mamdani M.M., Lee D.S. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the randomized aldactone evaluation study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:543–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes T., Khuu W., Martins D. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2018;362 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg A.E., Porter J., Saskin R., Rangrej J., Urbach D.R. Regional variation in the use of surgery in Ontario. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E310–E316. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brummett C.M., Waljee J.F., Goesling J. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanch B., Buckley N.A., Mellish L., Dawson A.H., Haber P.S., Pearson S.A. Harmonizing post-market surveillance of prescription drug misuse: a systematic review of observational studies using routinely collected data (2000-2013) Drug Saf. 2015;38:553–564. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parente S.T., Kim S.S., Finch M.D. Identifying controlled substance patterns of utilization requiring evaluation using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:783–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasricha S.V., Tadrous M., Khuu W. Clinical indications associated with opioid initiation for pain management in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study. Pain. 2018;159:1562–1568. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuckit M.A. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1596–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanuseputro P., Budhwani S., Bai Y.Q., Wodchis W.P. Palliative care delivery across health sectors: a population-level observational study. Palliat Med. 2017;31:247–257. doi: 10.1177/0269216316653524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovejoy T.I., Morasco B.J., Demidenko M.I., Meath T.H., Frank J.W., Dobscha S.K. Reasons for discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy in patients with and without substance use disorders. Pain. 2017;158:526–534. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun E.C., Darnall B.D., Baker L.C., Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1286–1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin P.C. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33:1057–1069. doi: 10.1002/sim.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse J.W., Craigie S., Juurlink D.N. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189:E659–E666. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomes T., Mamdani M.M., Dhalla I.A., Paterson J.M., Juurlink D.N. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes T., Redelmeier D.A., Juurlink D.N., Dhalla I.A., Camacho X., Mamdani M.M. Opioid dose and risk of road trauma in Canada: a population-based study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:196–201. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin P.C. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-one matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1092–1097. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam A., Gomes T., Bell C.M. Long-term analgesic use: sometimes less is not more-reply. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1189–1190. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke H., Soneji N., Ko D.T., Yun L., Wijeysundera D.N. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edlund M.J., Martin B.C., Fan M.Y., Devries A., Braden J.B., Sullivan M.D. Risks for opioid abuse and dependence among recipients of chronic opioid therapy: results from the TROUP study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edlund M.J., Steffick D., Hudson T., Harris K.M., Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austin P.C. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38:1228–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Austin P.C. A tutorial on multilevel survival analysis: methods, models and applications. Int Stat Rev. 2017;85:185–203. doi: 10.1111/insr.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee E.W., Wei L.J., Amato D.A., Leurgans S. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. In: Klein J.P., Goel P.K., editors. Survival analysis: state of the art. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 1992. pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colson K.E., Rudolph K.E., Zimmerman S.C. Optimizing matching and analysis combinations for estimating causal effects. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23222. doi: 10.1038/srep23222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen T.L., Collins G.S., Spence J. Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:78. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernan M.A. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology. 2010;21:13–15. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong J., Lam D.P., Abrishami A., Chan M.T., Chung F. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:268–279. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vetter T.R., Boudreaux A.M., Jones K.A., Hunter J.M., Jr., Pittet J.F. The perioperative surgical home: how anesthesiology can collaboratively achieve and leverage the triple aim in health care. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:1131–1136. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vozoris N.T. Prescription opioid use in advanced COPD: benefits, perils and controversies. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1700479. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00479-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vozoris N.T., Wang X., Fischer H.D. Incident opioid drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:683–693. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01967-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vozoris N.T., Wang X., Austin P.C. Adverse cardiac events associated with incident opioid drug use among older adults with COPD. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen-Dahm C., Gasse C., Astrup A., Mortensen P.B., Waldemar G. Frequent use of opioids in patients with dementia and nursing home residents: a study of the entire elderly population of Denmark. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Husebo B.S., Ballard C., Sandvik R., Nilsen O.B., Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clarke H. Transitional Pain Medicine: novel pharmacological treatments for the management of moderate to severe postsurgical pain. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:345–349. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2016.1129896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang A., Katz J., Clarke H. Ensuring safe prescribing of controlled substances for pain following surgery by developing a transitional pain service. Pain Manag. 2015;5:97–105. doi: 10.2217/pmt.15.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katz J., Weinrib A., Fashler S.R. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:695–702. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S91924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassamal S., Haglund M., Wittnebel K., Danovitch I. A preoperative interdisciplinary biopsychosocial opioid reduction program in patients on chronic opioid analgesia prior to spine surgery: a preliminary report and case series. Scand J Pain. 2016;13:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wightman R., Perrone J., Portelli I., Nelson L. Likeability and abuse liability of commonly prescribed opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:335–340. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0263-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cairncross Z.F., Herring J., van Ingen T. Relation between opioid-related harms and socioeconomic inequalities in Ontario: a population-based descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2018;6:E478–E485. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20180084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedman J., Kim D., Schneberk T. Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:469–476. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holland E., Bateman B.T., Cole N. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after Cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91–97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartford L.B., Van Koughnett J.A.M., Murphy P.B. Standardization of Outpatient Procedure (STOP) Narcotics: a prospective non-inferiority study to reduce opioid use in outpatient general surgical procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.09.008. 81–8 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee J.S., Howard R.A., Klueh M.P. The impact of education and prescribing guidelines on opioid prescribing for breast and melanoma procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:17–24. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6772-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rojas K.E., Manasseh D.M., Flom P.L. A pilot study of a breast surgery Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocol to eliminate narcotic prescription at discharge. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hah J.M., Bateman B.T., Ratliff J., Curtin C., Sun E. Chronic opioid use after surgery: implications for perioperative management in the face of the opioid epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1733–1740. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soneji N., Clarke H.A., Ko D.T., Wijeysundera D.N. Risks of developing persistent opioid use after major surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1083–1084. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin B.C., Fan M.Y., Edlund M.J., Devries A., Braden J.B., Sullivan M.D. Long-term chronic opioid therapy discontinuation rates from the TROUP study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1450–1457. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1771-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanderlip E.R., Sullivan M.D., Edlund M.J. National study of discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy among veterans. Pain. 2014;155:2673–2679. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mudumbai S.C., Oliva E.M., Lewis E.T. Time-to-cessation of postoperative opioids: a population-level analysis of the veterans affairs health care system. Pain Med. 2016;17:1732–1743. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Darnall B.D., Juurlink D., Kerns R.D. International stakeholder community of pain experts and leaders call for an urgent action on forced opioid tapering. Pain Med. 2019;20:429–433. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Demidenko M.I., Dobscha S.K., Morasco B.J., Meath T.H.A., Ilgen M.A., Lovejoy T.I. Suicidal ideation and suicidal self-directed violence following clinician-initiated prescription opioid discontinuation among long-term opioid users. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2017;47:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quan H., Sundararajan V., Halfon P. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matheson F.I., Dunn J.R., Smith K.L., Moineddin R., Glazier R.H. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: a new tool for the study of inequality. Can J Public Health. 2012;103:S12–S16. doi: 10.1007/BF03403823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.