Abstract

Extensive evidence suggests that exposure to childhood abuse can lead to harmful health effects across a lifetime. To contribute to the literature, the current study examined whether and how a history of parental childhood abuse affects exposure to and severity appraisal of daily stressors in adulthood, as well as emotional reactivity to these stressors. We analyzed 14,912 daily interviews of 2,022 respondents from the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences. Multilevel modeling was utilized to analyze nested data, in that each person provided repeated measures of daily experience for eight consecutive study days. Results showed that more frequent experience of maternal childhood abuse was associated with more severe appraisal of daily stressors. In addition, adults with more frequent maternal childhood abuse exhibited greater emotional reactivity to daily stressors. The current study provides evidence that a history of parental childhood abuse may serve as a vulnerability factor in the process of experiencing and responding to stressful events encountered in daily life. Future research should further explore the long-term health effects of daily stress and emotional experience among adults with a history of parental childhood abuse. Interventions for these adults should focus on promoting emotional resilience in the face of daily stress.

Keywords: childhood maltreatment, daily stressor exposure, daily stressor severity, daily emotional reactivity

Exposure to childhood maltreatment is a well-documented risk factor for negative health outcomes in adulthood, including greater mortality risks, accelerated aging processes, and more psychiatric problems such as depression (Chen, Turiano, Mroczek, & Miller, 2016; Green et al., 2010; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2011). One of the recognized mechanisms for these long-term harmful health effects is victims’ maladaptive responses to stress in childhood, such as elevated emotional reactivity (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Shapero et al., 2014). However, there is an obvious research gap regarding the effects of parental childhood abuse on the ways in which adults experience, interpret, and respond to stressful events in their daily lives. The study of daily stress processes can offer a framework for understanding how parental childhood abuse may (a) disrupt day-to-day stress experiences and (b) affect the individual’s well-being, both of which can have the potential to impair long-term health outcomes (Brosschot, 2010; Mroczek et al., 2013). Furthermore, rigorous evidence can be obtained through a daily diary approach that captures the association between the experience of daily stressors and changes in affect within an individual (Almeida, 2005; Larson & Almeida, 1999). To address this gap in the literature, the current study aimed to examine whether and how histories of parental childhood abuse affect daily stress processes in adulthood, with a specific focus on exposure to daily stressors, subjective severity ratings of daily stressors, and emotional reactivity to daily stressors. Using the National Study of Daily Experiences–II (NSDE II, 2004–2009) combined with the longitudinal National Survey of Midlife in the United States (MIDUS I and II), we examined 2,022 respondents’ daily experiences over eight consecutive days.

Exposure and Reactivity to Daily Stressors

Daily stressors are defined as minor events arising out of day-to-day living, which include both routine and unexpected occurrences (e.g., work-related concerns, arguments with spouse/partner) that can pose a challenge and disruption in daily life (Almeida, 2005; Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). The primary foci of daily stress research have been exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. First, “exposure” refers to the frequency of experiencing daily stressors, whereas “reactivity to daily stressors” is defined as the difference in an individual’s level of health and well-being on days when stressors occur, compared with days when no stressors occur (Almeida & Davis, 2011; Almeida, Serido, & McDonald, 2006; Howland, Armeli, Feinn, & Tennen, 2017). Greater reactivity to daily stressors represents emotional and/or physical vulnerabilities to stimuli that may lead to cumulative health risks over time (Leger, Charles, & Almeida, 2018; Piazza and Charles, 2006; Uchino, Holt-Lunstad, Bloor, & Campo, 2005). Prior studies suggest that accumulated days with persistent frustrations and overload can be as damaging as major life events, resulting in more serious, chronic stress reactions and the attendant impairments in long-term health and functioning (Brosschot, 2010; Mroczek et al., 2013). Another aspect of daily stress research involves the subjective severity of the stressors people experience (Stawski, Almeida, Lachman, Tun, & Rosnick, 2010). According to prior research findings, there are individual differences, such as gender, in subjective severity reports of the daily stressors (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Stawski et al., 2010) that may significantly affect daily emotional well-being (Scott, Sliwinski, & Blanchard-Fields, 2013).

Effects of Parental Childhood Abuse on Daily Stress Processes

Considerable research has examined individual differences associated with resilience or vulnerability to daily stress processes based on ascribed characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity), socioeconomic status (e.g., educational attainment), and psychosocial factors (e.g., social support; Almeida, 2005; Almeida, Stawski, & Cichy, 2010; Zautra, 2003). In the current study, we proposed that parental childhood abuse, a life-course factor, would contribute to susceptibility and vulnerability to daily stressors. First, adults with histories of parental childhood abuse may experience more frequent exposure to daily stressors, possibly because of psychosocial correlates of childhood abuse (e.g., a low self-esteem, lack of social competence, and use of mal-adaptive problem-solving skills) that can deteriorate previously abused adults’ ability to function and interact with others on a daily basis (Alink, Cicchetti, Kim, & Rogosch, 2012; Coates, Dinger, Donovan, & Phares, 2013; Riggs, 2010). According to Infurna, Rivers, Reich, and Zautra (2015), adults who experienced emotional, physical, and sexual abuse during childhood reported more frequent exposure to daily negative events, but not to daily positive events. Second, parental childhood abuse may affect an individual’s appraisal of daily stressors. Considering the significant link between insecure adult attachment and negative stress appraisal (Bryant & Guthrie, 2005; McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010), adults with a history of parental childhood abuse may amplify the severity or threats/risks associated with the daily stressors they experience.

Another goal of this study was to examine the effects of parental childhood abuse on emotional reactivity to daily stressors. Violence at the hands of parents, who are supposed to serve as a source of security and safety, can lead to the maladaptive development of physiological and emotional regulatory processes in children, which facilitate disruptions/vulnerabilities in emotional experience and expression in the face of stressful situations, such as elevated emotional reactivity to stress (McLaughlin et al., 2010; Schuengel, Oosterman, & Sterkenburg, 2009; Shapero et al., 2014). Only a few studies have addressed the effects of childhood adversity on emotional responses to daily stressors. Poon and Knight (2012) found that women with a history of maternal emotional abuse showed greater emotional reactivity to network stressors (i.e., one type of stressors that refers to anything happened to a close friend or relative that turned out to be stressful) compared with women who reported less maternal emotional abuse. Glaser, van Os, Portegijs, and Myin-Germeys (2006) revealed that a history of childhood sexual and/or physical trauma was associated with heightened emotional reactivity to daily stressors. Similarly, Infurna and colleagues (2015) showed that a history of childhood trauma was associated with a greater decrease in daily positive affect when experiencing daily negative events.

The Current Study

The current study used a daily diary design to examine the effects of parental childhood abuse on daily stress processes among a national sample of middle-aged and older adults from the NSDE II. Based on a review of previous research, we predicted that parental childhood abuse would be linked to greater exposure and emotional reactivity to daily stressors. Three questions regarding this link motivated the current study: First, is parental childhood abuse associated with greater exposure to daily stressors? Second, is parental childhood abuse associated with how individuals rate the severity of the stressors they report experiencing? Third, does parental child abuse moderate the associations between exposure to and severity of daily stressors and daily affect? Consistent with previous literature showing parental childhood abuse as a risk factor for adult health and well-being, we hypothesized that individuals with more frequent experiences of parental childhood abuse would (a) exhibit greater exposure to daily stressors, (b) assess the stressors as more severe, and (c) be more emotionally reactive to daily stressors (i.e., a greater change in daily affect on stressor days compared with nonstressor days) compared with individuals who reported less frequent experiences of parental childhood abuse.

Method

Data Set and Study Sample

MIDUS is a national longitudinal study of 7,108 individuals who were first surveyed in 1995 to 1996. All eligible participants were noninstitutionalized, English-speaking adults in the United States, aged 25 to 74 years. The original MIDUS study sample comprised adults from four subsamples: a national random digit dialing (RDD) sample (n = 3,487), oversamples from five metropolitan areas (n = 757), siblings of individuals from the RDD sample (n = 950), and a national RDD sample of twin pairs (n = 1,914). A longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS study (MIDUS II) was conducted in 2004 to 2006, in which 75% of the surviving original respondents (n = 4,963) participated.

The NSDE II (2004–2009) is one of the ancillary projects of MIDUS II. A representative subsample of 2,022 MIDUS II participants completed short telephone interviews about their daily experiences across eight consecutive days. Computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPIs) were conducted to incorporate skip patterns and open-ended probe questions as well as to key-punch data during the interview. Data collection was spread throughout the year and consisted of separate “flights” of interviews with each flight representing the 8-day sequence of interviews from approximately 20 respondents. The focal point of the NSDE II was to examine how sociodemographic factors, health status, or personality characteristics modify patterns of exposure to day-to-day life stressors as well as physical and emotional reactivity to these stressors. The respondents completed an average of seven out of the eight daily interviews, resulting in a total of 14,912 valid daily interviews (92% completion rate).

Measures

Childhood abuse.

Parental childhood abuse was measured by six items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). Emotional abuse was measured by the following item: “During your childhood, how often did your (a) mother or the woman who raised you; (b) father or the man who raised you insult you or swear at you, sulk or refuse to talk to you, stomp out of the room, do or say something to spite you, threaten to hit you, smash or kick something in anger?” Physical abuse was measured by the following items: “During your childhood, how often did (c) your mother or the woman raised you; (d) father or the man raised you push, grab, or shove you, slap you, throw something at you?” and “During your childhood, how often did your (e) your mother or the woman raised you; (f) father or the man raised you, kick, bite, or hit you with a fist, hit or try to hit you with something, beat you up, choke you, burn or scald you?”

Respondents rated the items on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often). Based on the previous literature, as well as the results of a factor analysis of the six items, we averaged the three abuse items for mother and father separately and created two predictors: maternal childhood abuse (α = .80) and paternal childhood abuse (α = .82).

Daily affect.

Daily negative and positive affect were assessed using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scales (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Daily negative affect was measured by responses to 14 negative emotions, including being restless or fidgety, nervous, worthless, everything was an effort, and hopeless (α = .85). Daily positive affect was measured by responses to 13 positive emotions, including being in good spirits, cheerful, confident, enthusiastic, and satisfied (α = .94). Respondents rated the items on a 5-point scale (0 = none of the time, 4 = all of the time). The total scores were calculated by averaging the specific affect items. For daily negative affect, the square root transformation was applied to minimize the impact of skewness on the assumption of normality.

Any daily stressor.

Daily stressors were assessed through the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida et al., 2002). The instrument contains seven questions for identifying whether stressful events occurred (yes = 1, no = 0) within the past 24 hr in various life domains that include (a) having had an argument or disagreement with someone; (b) almost having had an argument or disagreement but having avoided it; (c) having had a stressful event happen at work or school; (d) having had a stressful event happen at home; (e) experiencing race, gender, or age discrimination; (f) having had something bad happens to a relative or close friend; and (g) having had anything else bad or stressful happen. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Surachman, Wardecker, Chow, & Almeida, 2019; Wong & Shobo, 2017), we created a binary daily stressor variable summarizing across the seven categories that indicated whether (= 1) or not (= 0) any daily stressor had occurred on the day of the interview. To assess respondents’ overall exposure to stressors, we created a person-level stressor exposure variable by calculating the proportion of study days that any stressors had occurred.

Daily stressor severity.

Participants were asked to rate the subjective severity of each stressor (i.e., “how stressful was this for you?”) they actually experienced on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all stressful) to 3 (very stressful).

Covariates.

Several sociodemographic characteristics were included in the analyses as covariates, including gender, race, age, marital status, education, and self-reported physical health. In addition, we controlled for respondent’s other adverse experiences during childhood: whether (= 1) or not (= 0) the respondent had experienced (a) parental substance abuse issues (i.e., drinking problems and use of drugs) and (b) parental divorce. Father’s highest level of education was included to assess childhood socioeconomic status.

Analytic Strategy

A multilevel modeling approach was used to account for the nested data structure where an individual is considered a cluster (Level 2), and repeated measures across the 8 days are considered variations within an individual (Level 1). First, to test for the effects of parental childhood abuse on the exposure to any daily stressors (coded as 0 if no stressor occurred, and 1 if any stressors occurred), we estimated multilevel logistic models predicting the exposure to daily stressors as a function of maternal and paternal childhood abuse and the covariates. Second, to test for the effects of parental childhood abuse on subjective stressor severity, we modeled a multilevel linear model treating the severity ratings as a continuous dependent variable.

Third, multilevel linear models were estimated to examine the moderating effects of parental childhood abuse on the within-person association between daily stressor experience and daily affect. The equations for the analysis model are as follows:

where B0i is the intercept indicating person i’s level of negative/positive affect on days with no stressor, B1i is changes in negative/positive affect from a nonstressor day to a stressor day, indicating emotional reactivity of person i to daily stressors. Error term εdi represents a unique effect associated with person i. In the Level 2 equation, the within-person intercept coefficient (B0i) was modeled as a function of between-person differences in terms of person i’s average exposure to daily stressors over the 8 days, maternal and paternal childhood abuse, and the list of covariates. The within-person slope coefficient (B1i) was modeled as a function of parental childhood abuse to test whether these reactivity slopes varied by histories of parental childhood abuse. Specific parameters of interest were γ11 and γ12, indicating the difference in daily stressor reactivity with respect to a unit increase in the frequency of maternal and paternal childhood abuse. Interindividual fluctuations from the level and slope were indicated by μ0i and μ1i, respectively. In addition, the identical multilevel models were estimated to examine the effect of the subjective stressor severity on daily affect, by replacing any daily stressors and average daily stressor exposure with the within-person and between-person daily stressor severity. Stata 14 was used for the set of analyses, and missing data were dealt by a full information maximum likelihood approach.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. On average, maternal and paternal abuse occurred rarely based on the 4-point scale (M = 1.55, SD = 0.68; M = 1.59, SD = 0.71, respectively). About half of the sample was male (42.8%, n = 865), and the majority were White (82.7%, n = 1,672) and married (68.6%, n = 1,387). The average age was 56.3 years with a range of 33 to 84 years. About 10% of respondents experienced parental divorce and parental substance abuse problems. In addition, respondents reported experiencing, on average, at least one stressor on 40% of the study days (M = 0.40, SD = 0.27).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics of Study Sample and Key Variables (N = 2,022).

| N/M (SD) | %/Minimum/Maximum | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal childhood abuse | 1.55 (0.68) | 1/4 |

| Paternal childhood abuse | 1.59 (0.71) | 1/4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 865 | 42.78 |

| Female | 1,157 | 57.22 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1,672 | 82.69 |

| Others | 291 | 14.39 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1,387 | 68.60 |

| Nonmarried | 633 | 31.31 |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Good/very good/excellent | 1,729 | 85.51 |

| Poor/fair | 292 | 14.44 |

| Age | 56.25 (12.20) | 33/84 |

| Years of education | 7.26 (2.53) | 1/12 |

| Years of father’s education | 4.84 (3.00) | 1/12 |

| Experience of other childhood adversity | ||

| Parental divorce | 607 | 9.13 |

| Parental substance abuse problems | 533 | 9.59 |

| Any daily stressorsa | 0.40 (0.27) | 0/1 |

| Daily negative affecta | 0.31 (0.26) | 0/1.59 |

| Daily positive affecta | 2.72 (0.71) | 0/4 |

Repeated measures were averaged across the eight study days.

Parental Childhood Abuse and Exposure and Severity of Daily Stressors

Table 2 shows the results of multilevel models predicting daily stressor exposure and severity as a function of parental childhood abuse. The results indicated that more frequent experience of maternal and paternal childhood abuse was not significantly associated with exposure to daily stressors, whereas more frequent experience of maternal childhood abuse predicted more severe ratings of stressors they experienced (est. = 0.09, p < .01). In terms of key sociodemographic predictors, excellent/good self-rated health was not associated with daily stressor exposure but significantly associated with more severe ratings of stressors. Older age was associated with reduced exposure to stressors and lower severity ratings. More years of education was significantly associated with greater exposure to daily stressors.

Table 2.

Effects of Parental Childhood Abuse on Exposure and Severity of Daily Stressors.

| Any Daily Stressor | Stressor Severity | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Est. (SE) | |

| Maternal childhood abuse | 1.12 | 0.09** |

| Paternal childhood abuse | 1.10 | 0.00 |

| Female | 1.27** | 0.34*** |

| White | 1.21 | 0.06 |

| Married | 0.98 | −0.00 |

| Good health status | 0.82 | −0.34*** |

| Age | 0.98*** | −0.01** |

| Years of education | 1 11*** | 0.00 |

| Years of father’s education | 1.05*** | 0.00 |

| Parental divorce | 1.15 | 0.08 |

| Parental substance abuse | 1.05 | 0.02 |

Note. N = 2,022. Any daily stressor was coded a binary variable indicating as to whether (= 1) or not (= 0) any daily stressor had occurred across the 8 days. The subjective severity of each stressor respondents experienced was rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all stressful, 3 = very stressful).

Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Parental Childhood Abuse and Emotional Reactivity to Daily Stressors

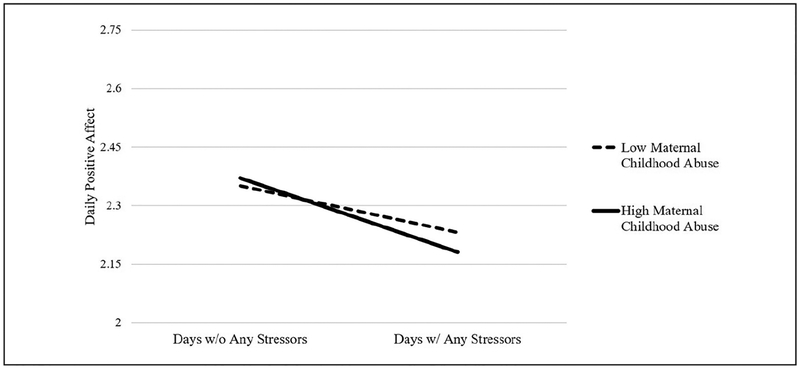

Table 3 presents the results of the effects of daily stressor exposure and severity ratings on daily affect. We found that maternal childhood abuse moderated the association between daily stressors and daily negative affect (est. = 0.03, p < .05). In other words, the positive association between daily stressors and daily negative affect (i.e., reactivity to daily stressors) was stronger for adults who reported more frequent maternal childhood abuse (Figure 1). A similar pattern was found in the model predicting daily positive affect: Experiencing any daily stressors related to lower daily positive affect, but the within-person association was stronger for adults who reported more frequent maternal childhood abuse (est. = −0.05, p < .01; Figure 2). In addition, we found the significant main effects of subjective ratings of daily stressor severity on both daily negative and positive affect, but the associations were not specific to parental childhood abuse. In other words, more frequent childhood abuse from the mother or father did not moderate the associations between daily stressor severity and daily affect. Excellent/good self-rated health, older age, and more years of educations showed greater daily emotional well-being (i.e., lower negative affect and higher positive affect).

Table 3.

Emotional Stress Reactivity: Moderation by History of Childhood Abuse.

| Daily Negative Affect | Daily Positive Affect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE) | ||||

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.40 (0.02)*** | 0.34 (0.04)*** | 2.36 (0.08)*** | 2.79 (0.10)*** |

| Average daily stressor exposure (BP) | 0.27 (0.02)*** | −0.49 (0.08)*** | ||

| Average daily stressor severity (BP) | 0.15 (0.01)*** | −0.30 (0.03)*** | ||

| Maternal childhood abuse | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.03) |

| Paternal childhood abuse | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.05 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.03) |

| Any daily stressors (WP) | 0.21 (0.01)*** | −0.15 (0.01)*** | ||

| Maternal Childhood Abuse × Any Daily Stressors (WP) | 0.03 (0.01)* | −0.05 (0.02)** | ||

| Paternal Childhood Abuse × Any Daily Stressors (WP) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Stressor severity (WP) | 0.08 (0.01)*** | −0.12 (0.01)*** | ||

| Maternal Childhood Abuse × Stressor Severity (WP) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.02) | ||

| Paternal Childhood Abuse × Stressor Severity (WP) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Female | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.04)* |

| White | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.00 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.11 (0.06) |

| Married | −0.03 (0.01)* | −0.04 (0.02)* | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05)* |

| Good health status | −0.15 (0.02)*** | −0.14 (0.02)*** | 0.45 (0.06)*** | 0.36 (0.06)*** |

| Age | −0.00 (0.00)** | −0.00 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)*** | 0.01 (0.00)*** |

| Years of education | −0.01 (0.00)* | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Years of father’s education | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01)* |

| Parental divorce | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.07) |

| Parental substance abuse problems | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.14 (0.06)* | −0.15 (0.06)* |

| Random effects | ||||

| Variance of intercept | 0.17*** | 0.05* | 0.64*** | 0.58* |

| Variance of daily stressors (severity) | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.14*** | 0.08*** |

| Covariance between intercept and daily stressor (severity) | 0.01 | 0.43 | −0.32 | 0.45 |

| Residual variance | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| AIC | 213.68 | 1,131.81 | 11,223.80 | 5,433.96 |

| BIC | 354.59 | 1,253.70 | 11,364.71 | 5,555.85 |

Note. BP = between person; WP = within person; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Significance levels are denoted as

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Emotional reactivity to daily stressors: Negative affect.

Figure 2.

Emotional reactivity to daily stressors: Positive affect.

Discussion

The current study investigated the effects of parental childhood abuse on daily stress processes in adulthood. Our specific focus was whether and how histories of parental childhood abuse were associated with exposure and severity ratings of daily stressors, and whether parental childhood abuse moderated the within-person associations between daily stressor exposure/severity and daily affect. Overall, our findings offer evidence that a history of parental childhood abuse may serve as a vulnerability factor in the process of experiencing and responding to stressful events encountered in daily life.

Maternal Childhood Abuse Linked to Severity Ratings of Daily Stressors

Contrary to our hypothesis, parental childhood abuse was not significantly associated with exposure to daily stressors. However, we did find that more frequent exposure to maternal childhood abuse was associated with more severe appraisals of the daily stressor experienced. This result is somewhat consistent with prior studies that indicated a significant link between a history of childhood abuse and a global assessment of stress. For example, Hyman, Paliwal, and Sinha (2007) found that adults who experienced more severe childhood maltreatment showed greater levels of perceived stress (i.e., subjective appraisals of the stressfulness of recent life events) than adults who reported less severe childhood maltreatment. These results suggest that histories of parental childhood abuse may have more to do with the ways of interpreting the intensity of the daily stressors experienced, rather than the actual occurrence of daily stressors.

Maternal Childhood Abuse Linked to Heightened Emotional Reactivity to Daily Stressors

Our hypothesis was partially supported, namely, that adults with more frequent experiences of maternal childhood abuse were emotionally more reactive to daily stressors than adults who reported less frequent experience of maternal childhood abuse. Paternal childhood abuse was not significantly associated with emotional reactivity to daily stressors. In addition, the effect of stressor severity on daily affect did not differ between abused and nonabused adults, suggesting that an individual’s appraisal of stressor severity may not explain greater emotional responses for previously abused adults, but stressor exposure itself may do. However, we can at least say that adults with greater exposure to maternal childhood abuse may experience more days with negative emotions and fewer days with positive emotions, considering that maternal childhood abuse was associated with more severe ratings of the daily stressor experienced, which had direct effects on daily affect.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown the significant effects of mother–child relationship quality on daily stress and emotional experience in adulthood. For example, Poon and Knight (2012) asserted that the quality of the mother–child relationship can influence stress and coping in later adulthood based on their findings: (a) Adult daughters who recalled more frequent maternal emotional abuse showed greater daily emotional distress across study days and (b) adult daughters’ recalled emotional closeness with their mother attenuated emotional reactivity to daily network stressors (i.e., anything happened to a close friend or relative that turned out to be stressful). Similarly, Mallers, Charles, Neupert, and Almeida (2010) identified the protective aspect of childhood relationships with mothers by showing that a high-quality mother–child relationship was significantly associated with less exposure to daily stressors and reduced daily psychological distress across the study days.

Furthermore, our findings regarding the specific risks associated with childhood abuse from mothers, but not fathers, may be in line with the large body of literature on attachment theory. Bowlby (1988) and Bartholomew (1990, 1993) emphasize the significance of a secure emotional connection between children and their primary caretaker, especially mothers for currently middle-aged and older adults, on individual development across life. Negative internal working modes of self and others (i.e., a view/perception of the self as unworthy and unlovable and others as untrustworthy and non-available)—which are strong correlates of maternal childhood abuse (Crawford & Wright, 2007; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994)—influence the ways in which individuals cope with and respond to stressful situations or distress (Browne & Winkelman, 2007; Lopez, Mauricio, Gormley, Simko, & Berger, 2001; Mikulincer, Shaver, & Pereg, 2003; Wei, Vogel, Ku, & Zakalik, 2005). Future research should explore the impact of the adult attachment system as a consequence of dysfunctional parent–child relationships on daily stress processes to better understand how the underpinning beliefs of the self and others can be manifested throughout daily life.

Effects of Health, Education, and Age on Daily Stress Experience and Well-Being

We note significant findings regarding the effects of self-rated health status, age, and socioeconomic status on daily stress experiences and well-being. Consistent with the findings of prior studies (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Hill et al., 2018; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007), excellent/good self-rated health status and older age were associated with less severe ratings of stressors and greater daily well-being. As discussed in prior studies (e.g., Almeida, Piazza, Stawski, & Klein, 2011), more years of education was associated with lower negative affect, although it was associated with more frequent exposure to daily stressors.

Limitations and Implications

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, childhood abuse measures were based on retrospective self-reports that could involve recall errors (Macmillan, 2009). In addition, the measures lacked certain specific details, such as the timing and duration of abuse. Second, the study sample may not reflect characteristics of the general population because of the attrition in the MIDUS II. According to Radler and Ryff (2010), higher retention rates for the MIDUS II were found among respondents who were White, female, and married, as well as those with better self-reported health and higher levels of education. We also note that the longitudinal MIDUS sample and the NSDE subsample had similar distributions for age as well as for marital and parenting status. However, the NSDE subsample had better educated participants, on average, along with more female and fewer minority participants. In terms of the daily stressors measure, we focused on examining the exposure to any daily stressors that occurred in the past 24 hr rather than differentiating specific stressor types. In accordance with this approach, we also averaged stressor severity ratings across different types of stressors. Although much of previous daily stress studies (e.g., Surachman et al., 2019; Wong & Shobo, 2017) relied on this any daily stressor approach to offer a comprehensive examination across a diverse venue of potential stressor exposures as well as to increase statistical power, future research may incorporate examining the interactive health effects of childhood adversity and specific daily stressor types.

Despite these noted limitations, the current study further advances existing knowledge by demonstrating that, at the micro, daily level, adults with a history of maternal childhood abuse may experience heightened emotional vulnerabilities in the face of stressors that can pose long-term cumulative risks on their health and well-being (Brosschot, 2010; Mroczek et al., 2013). Our approach was to integrate life-course perspectives into the daily stress framework by positing that stressors are not limited to contemporary time frames but rather can, in fact, be “more distally located in the life course” (Pearlin, 2010, p. 213). Future research should continue to explore the intersection between interindividual characteristics embedded in the life-course experiences and transitions and daily stress processes. It also warrants further research to empirically test the cumulative effects of these microlevel stress processes on long-term health and functioning of adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. In addition, future research may conceptualize childhood adversity based on the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) framework to acknowledge that parental abuse often co-occurs with other traumatic experiences, such as neglect and household dysfunction (Danielson & Sanders, 2018; Felitti et al., 1998). This inquiry will expand the well-established ACEs literature by positing daily stress experiences and well-being as potential mechanisms linking childhood adversity and negative health outcomes in later adulthood.

This study also provides important implications for practice. First, adults who experienced dysfunctional interactions with their mothers during childhood should be aware that past abuse has repercussions for the ways they interpret and respond to daily stressful events. This self-awareness may help reduce emotional vulnerabilities of these adults by enhancing their sense of control over daily situations or stressors (Koffer et al., 2017). In addition, practitioners can facilitate previously abused adults’ positive appraisal of daily stressors and help them use adaptive coping strategies to ameliorate negative emotional experience and increase emotional resilience in daily life.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging Grants T32 AG049676 and K02 AG039412 to The Pennsylvania State University. Since 1995, the MIDUS study has been funded by the following: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network, National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166), and National institute on Aging (U19-AG051426).

Author Biographies

Jooyoung Kong, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Social Work. Her research focuses on examining whether and how adults with a history of childhood maltreatment continue to be distressed, or victimized, in relationships with the parent(s) who abused and/or neglected them or in the process of providing care to their abusive parent(s).

Lynn M. Martire, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the Penn State University. Her research aims to identify the ways in which close relationships in adulthood affect health and chronic illness management, and the effects of chronic illness on close relationships.

Yin Liu, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Human Development and Family Studies at Utah State University. She is a developmental psychologist by training with an interdisciplinary research background focused on individuals’ health and well-being across adulthood and old age.

David M. Almeida, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the Penn State University. His primary research interest has been the role of daily stress on healthy aging, focusing on specific populations and contexts, such as the workplace and family interactions, parents of children with developmental disabilities, and family caregivers.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alink LRA, Cicchetti D, Kim J, & Rogosch FA (2012). Longitudinal associations among child maltreatment, social functioning, and cortisol regulation. Developmental Psychology, 48, 224–236. doi: 10.1037/a0024892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, & Davis KD (2011). Workplace flexibility and daily stress processes in hotel employees and their children. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638, 123–140. doi: 10.1177/0002716211415608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, & Horn MC (2004). Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In Brim OG, Ryff CD, & Kessler RC (Eds.), How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife (pp. 425–451). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Piazza JR, Stawski RS, & Klein LC (2011). The speedometer of life: Stress, health and aging. In Schaie KW & Willis SL (Eds.), The Handbooks of Aging. 3 vols.: Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 191–206). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Serido J, & McDonald D (2006). Daily life stressors of early and late baby boomers. In Whitbourne SK & Willis SL (Eds.), The baby boomers at midlife: Contemporary perspectives on middle age. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Stawski RS, & Cichy KE (2010). Combining checklist and interview approaches for assessing daily stressors: The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events. In Contrada RJ & Baum A (Eds.), The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health (pp. 583–595). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Kessler RC (2002). The daily inventory of stressful experiences (DISE): An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment, 9, 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147–178. doi: 10.1177/0265407590072001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K (1993). From childhood to adult relationships: Attachment theory and research. In Duck SW (Ed.), Understanding relationship processes 2: Learning about relationships (pp. 30–62). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF (2010). Markers of chronic stress: Prolonged physiological activation and (un)conscious perseverative cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne C, & Winkelman C (2007). The effect of childhood trauma on later psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 684–697. doi: 10.1177/0886260507300207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, & Guthrie RM (2005). Maladaptive appraisals as a risk factor for posttraumatic stress: A study of trainee firefighters. Psychological Science, 16, 749–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, & Miller GE (2016). Association of reports of childhood abuse and all-cause mortality rates in women. JAMA Psychiatry, 73, 920–927. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates EE, Dinger T, Donovan M, & Phares V (2013). Adult psychological distress and self-worth following child verbal abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 22, 394–407. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2013.775981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E, & Wright MO (2007). The impact of childhood psychological maltreatment on interpersonal schemas and subsequent experiences of relationship aggression. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 7, 93–116. doi: 10.1300/J135v07n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson R, & Sanders GF (2018). An effective measure of childhood adversity that is valid with older adults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 82, 156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J, van Os J, Portegijs PJM, & Myin-Germeys I (2006). Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61, 229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D, & Bartholomew K (1994). Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 430–445. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Sin NL, Turiano NA, Burrow AL, & Almeida DM (2018). Sense of purpose moderates the associations between daily stressors and daily well-being. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52, 724–729. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland M, Armeli S, Feinn R, & Tennen H (2017). Daily emotional stress reactivity in emerging adulthood: Temporal stability and its predictors. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 30, 121–132. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1228904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Paliwal P, & Sinha R (2007). Childhood maltreatment, perceived stress, and stress-related coping in recently abstinent cocaine dependent adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 233–238. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Rivers CT, Reich J, & Zautra AJ (2015). Childhood trauma and personal mastery: Their influence on emotional reactivity to everyday events in a community sample of middle-aged adults. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0121840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Gouin J, Weng N, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf DQ, & Glaser R (2011). Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73, 16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffer R, Drewelies J, Almeida DM, Conroy DE, Pincus AL, Gerstorf D, & Ram N (2017). The role of general and daily control beliefs for affective stressor-reactivity across adulthood and old age. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 242–253. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, & Almeida DM (1999). Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 5–20. doi: 10.2307/353879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2018). Let it go: Lingering negative affect in response to daily stressors is associated with physical health years later. Psychological Science, 29, 1283–1290. doi: 10.1177/0956797618763097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez FG, Mauricio AM, Gormley B, Simko T, & Berger E (2001). Adult attachment orientations and college student distress: The mediating role of problem coping styles. Journal of Counseling and Development, 79, 459–464. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01993.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R (2009). The life course consequences of abuse, neglect, and victimization: Challenges for theory, data collection, and methodology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallers MH, Charles ST, Neupert SD, & Almeida DM (2010). Perceptions of childhood relationships with mother and father: Daily emotional and stressor experiences in adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1651–1661. doi: 10.1037/a0021020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, & Gilman SE (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40, 1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, & Pereg D (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 77–102. doi: 10.1023/A:1024515519160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Stawski RS, Turiano NA, Chan W, Almeida DM, Neupert SD, & Spiro A III. (2013). Emotional reactivity and mortality: Longitudinal findings from the VA normative aging study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 398–406. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, & Charles ST (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, 216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (2010). The life course and the stress process: Some conceptual comparisons. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 207–215. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza J, & Charles ST (2006). Mental health and the baby boomers. In Whitbourne SK & Willis SL (Eds.), The baby boomers grow up: Contemporary perspectives on midlife (pp. 111–146). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Poon CYM, & Knight BG (2012). Emotional reactivity to network stress in middle and late adulthood: The role of childhood parental emotional abuse and support. The Gerontologist, 52, 782–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler BT, & Ryff CD (2010). Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 307–331. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti R, Taylor S, & Seeman T (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330–366. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs S (2010). Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: What theory and research tell us. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19, 5–51. doi: 10.1037/a0021319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuengel C, Oosterman M, & Sterkenburg PS (2009). Children with disrupted attachment histories: Interventions and psychophysiological indices of effects. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, & Blanchard-Fields F (2013). Age differences in emotional responses to daily stress: The role of timing, severity, and global perceived stress. Psychology and Aging, 28, 1076–1087. doi: 10.1037/a0034000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapero BG, Black SK, Liu RT, Klugman J, Bender RE, Abramson LY, & Alloy LB (2014). Stressful life events and depression symptoms: The effect of childhood emotional abuse on stress reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 209–223. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawski RS, Almeida DM, Lachman ME, Tun PA, & Rosnick DB (2010). Fluid cognitive ability is associated with greater exposure and smaller reactions to daily stressors. Psychology and Aging, 25, 330–342. doi: 10.1037/a0018246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, & Steinmetz SK (1980). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New York, NY: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Surachman A, Wardecker B, Chow SM, & Almeida D (2019). Life course socioeconomic status, daily stressors, and daily well-being: Examining chain of risk models. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Bloor LE, & Campo RA (2005). Aging and cardiovascular reactivity to stress: Longitudinal evidence for changes in stress reactivity. Psychology and Aging, 20, 134–143. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Vogel DL, Ku TY, & Zakalik RA (2005). Adult attachment, affect regulation, negative mood, and interpersonal problems: The mediating roles of emotional reactivity and emotional cutoff. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 14–24. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JD, & Shobo Y (2017). The moderating influences of retirement transition, age, and gender on daily stressors and psychological distress. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85, 90–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A (2003). Emotions, stress, and health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]