Abstract

NHP are important translational models for understanding the genomic underpinnings of growth, development, fetal programming, and predisposition to disease, with potential for the development of early health biomarkers. Understanding how prenatal gene expression is linked to pre- and postnatal health and development requires methods for assessing the fetal transcriptome. Here we used RNAseq methodology to analyze the expression of cell-free fetal RNA in the amniotic fluid supernatant (AFS) of vervet monkeys. Despite the naturally high level of degradation of free-floating RNA, we detected more than 10,000 gene transcripts in vervet AFS. The most highly expressed genes were H19, IGF2, and TPT1, which are involved in embryonic growth and glycemic health. We noted global similarities in expression profiles between vervets and humans, with genes involved in embryonic growth and glycemic health among the genes most highly expressed in AFS. Our study demonstrates both the feasibility and usefulness of prenatal transcriptomic profiles, by using amniocentesis procedures to obtain AFS and cell-free fetal RNA from pregnant vervets.

Abbreviations: AF, amniotic fluid; AFS, AF supernatant; cffRNA, cell-free fetal RNA; hAFS, human AFS; vAFS, vervet monkey AFS

Genetic and environmental factors acting during fetal development have been postulated to have long-lasting consequences on health and represent important risk factors for various diseases. For both humans and NHP, insight into the in utero environment and fetal development can be obtained from amniotic fluid (AF). Conventional AF analysis predominantly supports prenatal genetic diagnostics and biochemical assessments, for example, proteomic9 and neuroendocrine6 analyses, and, recently, as a source of fetal stem cells for modeling human diseases4 and regenerative medicine.12 In addition, AF is increasingly used as a source of nucleic acids—that is, DNA and RNA—for genetic and gene expression analysis.

AF bathes numerous fetal tissues, including skin, oropharynx, lung, and the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts and carries transcripts expressed in these tissues. Amniotic fluid supernatant (AFS) contains cell-free fetal RNA (cffRNA), which is exclusively of fetal origin and is the biomaterial that represents gene expression purely from fetal tissues.17 Transcriptome-wide analysis of gene expression in AFS, by using either microarrays13,18-20,31, 40 or, more recently, RNAseq26,27approaches, is increasingly applied to studies of human prenatal development and its links to health and disease.

Transcriptomic profiling of cffRNA from AF might also shed light on evolutionary differences and similarities in prenatal development between humans and other primate species. Such a perspective would be particularly important for NHP species frequently used as models in biomedical research. Here, we performed the first comparison of AFS transcriptomes between humans and vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus), which are an Old World monkey species widely used as a translational model for human disease and developmental studies.23,24

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement.

All animals were housed in the Vervet Research Colony at the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, NC). These facilities are AAALAC-certified. The animal handling and sample collection procedures in this study were performed by a veterinarian after review and approval by the Wake Forest School of Medicine IACUC (protocol no. A15-218). Both housing and sample collection were in compliance with the US National Research Council's Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals21 and meet or exceed all standards of the Public Health Service's Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.34

Humane care guidelines.

AF samples were obtained from adult female African green or vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus) that are from a multigenerational pedigreed colony. Animals are descendants of 57 original founders imported from St Kitts, West Indies, and have remained a closed colony since 1985.23 During the study, animals were housed as 16 matrilineal social groups in corrals with approximately 300 ft2 indoors and 1200 ft2 outdoors. Both indoor and outdoor sections were fitted with elevated perches, platforms, and climbing structures. Monkeys were fed commercial primate laboratory chow (Lab Diet no. 5038, Purina, St Louis MO) supplemented with fresh fruits and vegetables. All animals had unrestricted access to food, water, and opportunities to exercise. Group sizes ranged from 11 to 23 animals, with 1 or 2 intact adult males included in each group. Unfamiliar males are rotated into each group every 3 to 5 y.

We collected AF from 12 pregnant vervet monkeys through ultrasound-guided amniocentesis during their second and third trimesters. A volume of at least 3 mL was collected and was noted to be clear and free of gross blood contamination. The viability of the fetus was confirmed during the ultrasound examination by measuring fetal structures and assessment of heart function, as previously described.28

We regularly screen the colony for SIV, simian T-lymphotropic virus, SA6 African green monkey CMV, and SA8 viruses and, except for CMV, the colony is consistently negative. CMV is not typically associated with abortion and stillbirth. All available aborted fetus, stillbirth, or neonatal death was subjected to a full pathological examination including gross and histopathological review by a veterinary pathologist. Evaluations included pathogen testing when indicated by the pathologist's review. In this study cohort, no infectious causes of death were considered present.29

Sample collection and processing.

The collected AF was spun down (1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C) immediately after collection to remove residual vernix, and the supernatant (vAFS) was collected and instantaneously flash frozen by submerging in liquid nitrogen; samples subsequently were stored below –80 °C. For the transcriptomic analysis, we selected 3 samples with large volumes of vAFS (4.5 to 5 mL) and without visible blood contamination. These 3 samples were obtained from pregnancies resulting in a healthy born infant, a stillborn infant, and a single spontaneously aborted fetus (Table 1). The amniocentesis procedure was not believed to be related to stillbirth or abortion, given that factors relating to these outcomes have been examined28 and the frequency of fetal loss is not higher in animals that undergo amniocentesis compared with animals that do not (data not shown).

Table 1.

Study subjects and samples selected for RNAseq analysis

| Mother | Infant | ||||||||

| ID no. | Age (Y) | ID no. | Cranial diameter (cm) | Sex | Status | AFS volume (mL) | RNA integrity number | RNA yield (ng) | No. of RNAseq reads |

| 2008–100 | 7 | 2015–008 | 2 | F | stillborn | 4.5 | 1.3 | 107 | 66,267,374 |

| 2006–020 | 9 | 2015–011 | 2.8 | M | live | 4.5 | 2.5 | 341 | 47,814,071 |

| 1999–034 | 16 | 2203 | 2.2 | unknown | aborted | 5 | 1.8 | 376 | 57,761,334 |

Selected females represent a range of maternal ages, but all had comparable birth outcomes (6 births, 83.3% surviving).

The extraction of total RNA from the AFS samples was conducted according to a previous protocol.10 RNA was extracted within 30 to 45 d after collection. Briefly, we used a QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD) for RNA isolation; after extraction and for cleanup after DNase treatment, we purified the RNA by using an RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen).

RNAseq analysis.

We created cDNA libraries from 100 ng of total RNA by using the Ovation cDNA Synthesis/SPIA Amplification Kit (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA). Sequencing was conducted on a HiSeq2500 instrument by using RAPID (version 2) chemistry and generating 50-bp pair-end reads at 47.8 to 66.3 million reads per sample. The RNAseq reads were aligned to the Chlorocebus_sabeus 1.1 reference genomic assembly (GCF_000409795.2).45 Our dataset is deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus, under accession number GSE119908.

RNAseq reads were aligned to the vervet genomic assembly Chlorocebus_sabeus 1.1 GCF_000409795.245 by using the STAR aligner.11 Fragment counts were derived by using HTseq.3

We conducted a comparative analysis of the vervet AFS transcriptome with similar human samples and vervet postnatal tissues for which gene expression data sets are publically available in the NCBI repository. For the comparative analysis with human AFS (hAFS), we used transcriptomic data from hAFS generated through either RNAseq (a total of 21 samples: 5 samples from GSE4989046 and 16 samples from GSE68180)26 or by using expression microarray technology (a total of 74 samples: 14 samples from GSE16176, 11 samples from GSE25634, 12 samples from GSE33168, 16 samples from GSE46286, 16 samples from GSE48521, and 5 samples from GSE49891).13,19,20 For the comparative analysis with vervet postnatal tissues, we used RNAseq data that we had generated previously from 6 tissues (blood, fibroblasts, adrenal, pituitary, caudate, and hippocampus) from 59 or 60 vervets that ranged in age from neonates to adults.24 The RNAseq dataset from postnatal vervet tissues is available at NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus as bioproject PRJNA490653 (series GSE119908).

For comparative analysis of vAFS and vervet postnatal tissues (all datasets generated through RNAseq), we applied quantile normalization to all samples together. For comparative analysis of vAFS, vervet postnatal tissues, and hAFS datasets (comprising of both RNAseq and microarray datasets), we applied quantile normalization to all samples together (including 3 vervet samples and all other samples); batch effect was adjusted by using Combat.25 The top 1000 most-variable genes were selected for multidimensional scaling. We conducted MDS analysis by using the plotMDS function in edgeR39 to visualize the distance between the vAFS samples we analyzed herein and the reference datasets. For gene-annotation enrichment analysis, we used Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID), version 6.8.16 This tool maps genes to associated biologic terms (such as Gene Ontology terms and other annotations) and identifies the most over-represented terms among the genes of interest. We used a false discovery rate of 0.05 as a threshold for enriched terms.

Results

The amniocentesis procedure typically yields 10 to 20 mL of AF from humans17 and, based on our experience, 0.75 to 5 mL (average, 3.4 mL) from vervet monkeys. vAF was separated by centrifuge into 2 fractions: AFS containing cffRNA and pellets comprising amniocytes and vernix. From 3 AFS samples, we generated cDNA libraries, which subsequently were used for the RNAseq analysis.

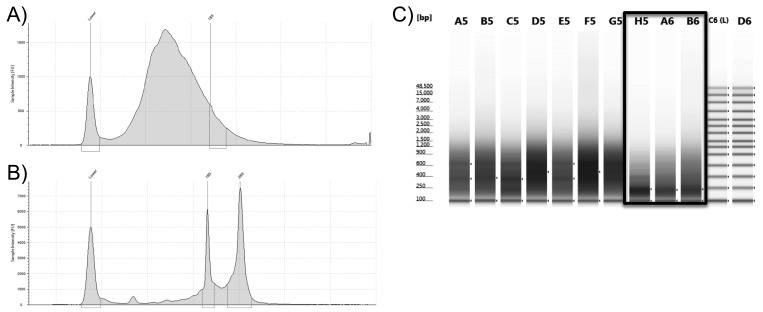

As expected, free-floating cffRNA, unprotected by cellular structures, showed a naturally high level of RNA degradation, with RNA integrity numbers ranging from 1.3 to 2.5 (Table 1). Because of natural cffRNA fragmentation or degradation, cDNA amplification generated transcripts smaller than average transcripts from intact RNA from cells and tissues (Figure 1). However, we still obtained usable cDNA libraries, in which we detected 23,276 genes expressed overall by using RNAseq.

Figure 1.

Quality of total RNA and cDNA libraries from cffRNA from vervet AFS. The integrity of (A) cffRNA from vervet AFS compared with (B) exceptionally high-quality total RNA. (C) cDNA libraries generated from cffRNA from vervet AFS (black frame) and from high-quality RNA.

Global gene expression profiles.

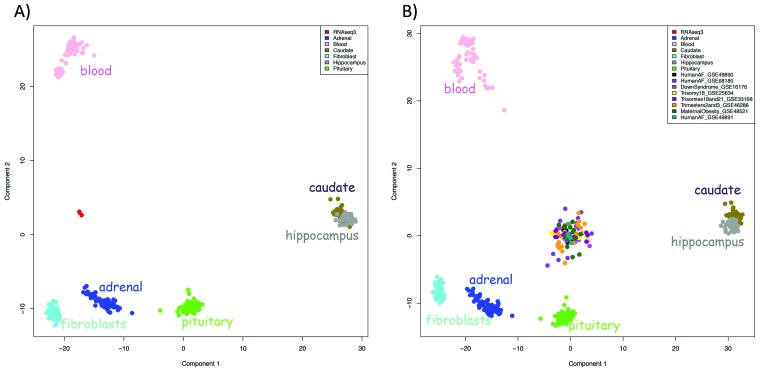

First, we compared global expression profiles between vAFS cffRNA from 3 different pregnancies and cellular RNA from 6 postnatal vervet tissues (hippocampus, caudate, adrenal, pituitary, skin fibroblasts, and whole blood) that we had characterized previously by using RNAseq.24 The first 2 dimensions from the multidimensional scaling analysis showed clear clustering according to sample type (Figure 2 A). The postnatal tissues clustered separately from each other (except for the 2 brain regions—the caudate and hippocampus— which showed a slight overlap) and distantly from a cluster of vAFS samples.

Figure 2.

MDS plot of gene expression. (A) Samples generated through RNAseq of cffRNA from vervet AFS form a distinct cluster separate from samples from various vervet postnatal tissues yet (B) cluster with transcripts from human AFS samples analyzed by using both RNAseq and a microarray platform. Different colors indicate different datasets as indicated in the key (the vervet AFS samples are shown in red; they form a cluster in the center of both plots).

Next, we compared our vAFS samples with 95 hAFS samples from 8 datasets generated by using microarray and RNAseq (Figure 2 B). Although the global gene expression profiles from the vAFS formed a distinct cluster, which was well separated from the vervet postnatal tissues, they clustered together with both microarray and RNAseq samples from hAFS. This analysis demonstrated that vAFS has an expression profile distinct from multiple postnatal tissues in the vervet and shows marked similarities with hAFS.

vAFS transcriptome.

In vAFS, we detected 23,276 gene transcripts overall, including 10,229 gene transcripts with robust expression (that is, 1 or more fragments per kilobase of transcript per 1 million mapped reads). Among the 10,229 expressed genes, 2093 genes were LOC genes, for which no human orthologs have been determined and usually with uncertain function. The list of the 100 most-expressed genes in vAFS is presented in Table 2 the most-expressed genes were H19, IGF2, and TPT1.

Table 2.

The top 100 most-expressed genes in vervet AFS

| Gene symbol | Gene description | Gene type | Rank vAFS GSE119908 | Rank hAFS GSE49890 | Rank hAFS GSE68180 |

| H19 | H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript | noncoding RNA | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| IGF2 | insulin like growth factor 2 | protein coding | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| TPT1 | tumor protein, translationally controlled 1 | protein coding | 3 | 5 | 42 |

| EEF1A1 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 α 1 | protein coding | 4 | 20 | 19 |

| RPS11 | ribosomal protein S11 | protein coding | 5 | 24 | 27 |

| FTL | ferritin light chain | protein coding | 6 | 18 | 9 |

| LOC103238605 | 40S ribosomal protein S13 | protein coding | 7 | NA | NA |

| RPS6 | ribosomal protein S6 | protein coding | 8 | 82 | 43 |

| LOC103226991 | 60S ribosomal protein L31 pseudogene | pseudogene | 9 | NA | NA |

| RPS16 | ribosomal protein S16 | protein coding | 10 | 85 | 50 |

| VIM | vimentin | protein coding | 11 | 146 | 132 |

| LOC103227869 | 40S ribosomal protein S20 | protein coding | 12 | NA | NA |

| RPS12 | ribosomal protein S12 | protein coding | 13 | 79 | 46 |

| LOC103236652 | 40S ribosomal protein S24 pseudogene | pseudogene | 14 | NA | NA |

| RPLP0 | ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 | protein coding | 15 | 180 | 105 |

| S100A6 | S100 calcium binding protein A6 | protein coding | 16 | 1172 | 127 |

| S100A11 | S100 calcium binding protein A11 | protein coding | 17 | 35 | 26 |

| LOC103233092 | 40S ribosomal protein S12 pseudogene | pseudogene | 18 | NA | NA |

| RPS8 | ribosomal protein S8 | protein coding | 19 | 61 | 31 |

| RPL24 | ribosomal protein L24 | protein coding | 20 | 917 | 128 |

| LOC103229159 | translationally controlled tumor protein pseudogene | pseudogene | 21 | NA | NA |

| WFDC2 | WAP 4-disulfide core domain 2 | protein coding | 22 | 211 | 171 |

| PABPC1 | poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 1 | protein coding | 23 | 97 | 53 |

| RPS5 | ribosomal protein S5 | protein coding | 24 | 95 | 65 |

| RPL19 | ribosomal protein L19 | protein coding | 25 | 103 | 69 |

| GNB2L1 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), β polypeptide 2-like 1 | protein coding | 26 | 105 | 87 |

| RPS25 | ribosomal protein S25 | protein coding | 27 | 108 | 35 |

| RPL27 | ribosomal protein L27 | protein coding | 28 | 127 | 92 |

| LOC103216818 | translationally-controlled tumor protein pseudogene | pseudogene | 29 | NA | NA |

| LOC103228928 | elongation factor 1- α 1 pseudogene | pseudogene | 30 | NA | NA |

| LOC103216022 | 40S ribosomal protein S15a | pseudogene | 31 | NA | NA |

| RPL4 | ribosomal protein L4 | protein coding | 32 | 199 | 76 |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium binding protein A10 | protein coding | 33 | 176 | 39 |

| LOC103238863 | uncharacterized LOC103238863 | pseudogene | 34 | NA | NA |

| LOC103226548 | 60S ribosomal protein L5 pseudogene | pseudogene | 35 | NA | NA |

| LOC103226449 | 60S ribosomal protein L4-like | protein coding | 36 | NA | NA |

| ANXA1 | annexin A1 | protein coding | 37 | 261 | 24 |

| LOC103215865 | annexin A8 | protein coding | 38 | NA | NA |

| LOC103244702 | 40S ribosomal protein S7 pseudogene | pseudogene | 39 | NA | NA |

| RPS3 | ribosomal protein S3 | protein coding | 40 | 83 | 190 |

| LOC103226189 | ferritin heavy chain | protein coding | 41 | NA | NA |

| LOC103216271 | nucleophosmin pseudogene | pseudogene | 42 | NA | NA |

| LOC103214626 | 60S ribosomal protein L30 | protein coding | 43 | NA | NA |

| EIF4G2 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 γ 2 | protein coding | 44 | 185 | 124 |

| RPL7 | ribosomal protein L7 | protein coding | 45 | 218 | 45 |

| RPL11 | ribosomal protein L11 | protein coding | 46 | 49 | 41 |

| LOC103236378 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | protein coding | 47 | NA | NA |

| LOC103233336 | 60S ribosomal protein L41 | protein coding | 48 | NA | NA |

| KRT24 | keratin 24 | protein coding | 49 | 681 | 292 |

| ANXA2 | annexin A2 | protein coding | 50 | 30 | 89 |

| LOC103244020 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 | protein coding | 51 | NA | NA |

| RPL14 | ribosomal protein L14 | protein coding | 52 | 371 | 141 |

| LOC103218934 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 pseudogene | pseudogene | 53 | NA | NA |

| RPL27A | ribosomal protein L27a | protein coding | 54 | 1932 | 648 |

| LOC103237685 | elongation factor 1- α pseudogene | pseudogene | 55 | NA | NA |

| LOC103237602 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 | protein coding | 56 | NA | NA |

| LOC103245600 | 60S ribosomal protein L18 | protein coding | 57 | NA | NA |

| SNAI2 | snail family transcriptional repressor 2 | protein coding | 58 | 354 | 269 |

| RPL10A | ribosomal protein L10a | protein coding | 59 | 152 | 55 |

| LOC103241228 | putative elongation factor 1- α -like 3 | pseudogene | 60 | NA | NA |

| LOC103242980 | protein S100-A11 pseudogene | pseudogene | 61 | NA | NA |

| RPS20 | ribosomal protein S20 | protein coding | 62 | 337 | 140 |

| LOC103220002 | annexin A2 pseudogene | pseudogene | 63 | NA | NA |

| PDLIM1 | PDZ and LIM domain 1 | protein coding | 64 | 167 | 311 |

| RPS27 | ribosomal protein S27 | protein coding | 65 | 29 | 7 |

| LOC103234934 | 40S ribosomal protein S26-like | protein coding | 66 | NA | NA |

| LOC103238540 | nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit α | protein coding | 67 | NA | NA |

| LOC103220486 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 pseudogene | pseudogene | 68 | NA | NA |

| RPS7 | ribosomal protein S7 | protein coding | 69 | 244 | 144 |

| LOC103238226 | 40S ribosomal protein S25 pseudogene | pseudogene | 70 | NA | NA |

| OST4 | oligosaccharyltransferase complex subunit 4, noncatalytic | protein coding | 71 | 151 | 40 |

| LOC103217050 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a pseudogene | pseudogene | 72 | NA | NA |

| RPLP1 | ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P1 | protein coding | 73 | 42 | 52 |

| LOC103216627 | 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform-like | protein coding | 74 | NA | NA |

| ACTB | actin β | protein coding | 75 | 28 | 49 |

| EEF1G | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 γ | protein coding | 76 | 69 | 84 |

| RPL36AL | ribosomal protein L36a like | protein coding | 77 | 360 | 148 |

| TUBA1B | tubulin α 1b | protein coding | 78 | 68 | 106 |

| LOC103240897 | 60S ribosomal protein L19 pseudogene | pseudogene | 79 | NA | NA |

| LOC103221872 | 40S ribosomal protein S27-like | protein coding | 80 | NA | NA |

| LOC103246919 | 40S ribosomal protein S19 | protein coding | 81 | NA | NA |

| EEF2 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 | protein coding | 82 | 59 | 98 |

| LOC103246174 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | protein coding | 83 | NA | NA |

| RPL15 | ribosomal protein L15 | protein coding | 84 | 236 | 143 |

| SERPINB9 | serpin family B member 9 | protein coding | 85 | 10611 | 12391 |

| CRIP1 | cysteine rich protein 1 | protein coding | 86 | 202 | 182 |

| CCND2 | cyclin D2 | protein coding | 87 | 224 | 407 |

| TUBB | tubulin β class I | protein coding | 88 | 204 | 2428 |

| RPL28 | ribosomal protein L28 | protein coding | 89 | 62 | 283 |

| RPS18 | ribosomal protein S18 | protein coding | 90 | 32077 | 206 |

| LOC103219323 | actin, cytoplasmic 1 | protein coding | 91 | NA | NA |

| RPL37 | ribosomal protein L37 | protein coding | 92 | 187 | 118 |

| NPC2 | NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 2 | protein coding | 93 | 922 | 273 |

| LOC103232182 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 pseudogene | pseudogene | 94 | NA | NA |

| LOC103240161 | 60S ribosomal protein L7a-like | protein coding | 95 | NA | NA |

| LOC103241403 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 pseudogene | pseudogene | 96 | NA | NA |

| RPL9 | ribosomal protein L9 | protein coding | 97 | 957 | 68 |

| RPL17 | ribosomal protein L17 | protein coding | 98 | 339 | 97 |

| RPS23 | ribosomal protein S23 | protein coding | 99 | 852 | 159 |

| TGM2 | transglutaminase 2 | protein coding | 100 | 181 | 508 |

NA, no corresponding ortholog in human annotation Chlorocebus sabaeus Annotation Release 100.

We focused on the most expressed genes in vAFS. To assess whether any biologic functions are associated with genes highly expressed in vAFS, we conducted gene-annotation analysis in the 500 most-expressed genes in vAFS. The enrichment analysis of biologic terms associated with these genes revealed that the enriched gene functions are predominantly related to ribosomes and their structural constituents, including small and large ribosomal subunits, and the processes of translation, translation initiation, and preinitiation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gene-term enrichment analysis results for the 500 most-expressed genes in vAFS

| Category | Term | Count | P | False discovery rate |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0003735 approximately structural constituent of ribosome | 61 | 6.95E-65 | 7.33E-62 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006412 approximately translation | 59 | 1.36E-56 | 1.49E-53 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005840 approximately ribosome | 47 | 3.51E-49 | 3.53E-46 |

| INTERPRO | IPR011332: Ribosomal protein, zinc-binding domain | 7 | 1.75E-08 | 2.58E-05 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0015934 approximately large ribosomal subunit | 7 | 3.53E-07 | 3.55E-04 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006446 approximately regulation of translational initiation | 7 | 1.15E-06 | 0.0012 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0016282 approximately eukaryotic 43S preinitiation complex | 6 | 2.52E-06 | 0.0025 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0033290 approximately eukaryotic 48S preinitiation complex | 6 | 2.52E-06 | 0.0025 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005852 approximately eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 complex | 6 | 2.52E-06 | 0.0025 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0015935approximately small ribosomal subunit | 6 | 4.25E-06 | 0.0042 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0001731 approximately formation of translation preinitiation complex | 6 | 6.76E-06 | 0.0074 |

BP, biologic process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function

Discussion

Transcriptomic studies across development in NHP have practically been restricted to postnatal tissues collected by using minimally or moderately invasive procedures, such as blood (and sometimes fat, muscle, liver, and skin biopsies) and postmortem tissues harvested during both pre- and postnatal development.5,24,36 Given the importance of NHP as models for biomedical studies, it is important to expand such investigations by introducing evaluations of prenatal development that allow the linking of prenatal fetal transcriptome with potential long-term health consequences. Here we demonstrated the feasibility of characterizing fetal RNAseq profiles from cffRNA in AFS as a proxy sample for fetal gene expression in vervet monkeys, one of the most widely used NHP model species.22,23

Despite the naturally high level of degradation of the free-floating cffRNA in AFS, we detected more than 10,000 genes with robustly measured expression in vervets. Gene-term enrichment analysis showed that genes with high expression were enriched for ribosomal components and translation, especially early stages of this process, which is consistent with intensive yet controlled growth and development during gestation.

Among the most highly expressed genes in vAFS were H19 and IGF2. H19 encodes a precursor of the microRNAs miR-675-5p and miR-675-3p7 and is associated with prenatal and early postnatal growth,14,37 shows tumor suppressor activity,15,30 and is deregulated in cancer progression, metastasis, and fetal growth syndromes.14,32 Deregulation of H19 expression during development causes Beckwith–Wiedemann and Silver–Russell syndromes,35,41 whereas in adults, H19 overexpression is associated with an increased risk of several cancers. H19 is the second most-expressed transcript in placenta.30 IGF2 encodes a hormone that promotes developmental growth during gestation. H19 and IGF2 are both genes that are involved in embryogenesis and are reciprocally imprinted in humans: H19 is expressed from the maternally derived allele, and IGF2 is expressed from the paternally derived allele.38 Genetic variation in these genes is associated with low birth weight in infants.1 In addition to genetic factors, maternal mental health during pregnancy influences H19 and IGF2 methylation status.32,44 Furthermore, intrauterine hyperglycemia is associated with alterations in the expression and methylation status of these genes.42

TPT1 (also known as TCTP) is the third most highly expressed gene in vAFS and is among the most highly expressed genes in hAFS. This gene is crucial for pancreatic cell proliferation during embryogenesis and the adaptation of these cells in response to insulin resistance in postnatal life43 and cancer development.2 Knockout of Tpt1 in mice is embryonically lethal.8

We observed global similarities in AFS expression profiles of vervets and humans. According to gene expression, our vAFS samples (which were analyzed with RNAseq) clustered with hAFS samples regardless of the analysis platform (both microarray and RNAseq). Importantly, IGF2 and TPT1, which are involved in embryonic growth and glycemic health in humans, are among the most highly expressed genes in AFS in both humans and vervets (Table 2). Maternal glycemic health has been implicated as a risk factor associated with infant mortality in vervet monkeys.28

In summary, we demonstrated the feasibility of assessing the fetal transcriptome in vervet monkeys through RNAseq analysis of cffRNA from AFS. This approach required moderately invasive sampling, which can be conducted on pregnant females in NHP breeding colonies to provide valuable insight into early developmental trajectories of fetal gene expression. AFS transcriptome is a possible source for biomarkers and predictors of the effects of genetics and early environmental exposures on prenatal and postnatal growth, development, and health.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a 2014 Mature pilot grant from Comparative Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine (to Kylie Kavanagh): “Effects of antenatal maternal factors on prenatal and postnatal development.” The Vervet Research Colony is supported by NIH grants UL1 TR001420 and P40 OD010965. Dalar Rostamian was involved in this research through the UCLA SRP99 program. We acknowledge the support of the NINDS Informatics Center for Neurogenetics and Neurogenomics (P30 NS062691). We thank Dr Matthew J Jorgensen whose contribution made this project possible.

References

- 1.Adkins RM, Somes G, Morrison JC, Hill JB, Watson EM, Magann EF, Krushkal J. 2010. Association of Birth Weight with Polymorphisms in the IGF2, H19 and IGF2R Genes. Pediatr Res 68:429–434. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181f1ca99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amson R, Pece S, Marine JC, Di Fiore PP, Telerman A. 2013. TPT1/ TCTP-regulated pathways in phenotypic reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol 23:37–46. 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. 2014. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31:166–169. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonucci I, Provenzano M, Rodrigues M, Pantalone A, Salini V, Ballerini P, Borlongan CV, Stuppia L. 2016. Amniotic fluid stem cells: a novel source for modeling of human genetic diseases. Int J Mol Sci 17: 1–14. 10.3390/ijms17040607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakken TE, Miller JA, Ding SL, Sunkin SM, Smith KA, Ng L, Szafer A, Dalley RA, Royall JJ, Lemon T, Shapouri S, Aiona K, Arnold J, Bennett JL, Bertagnolli D, Bickley K, Boe A, Brouner K, Butler S, Byrnes E, Caldejon S, Carey A, Cate S, Chapin M, Chen J, Dee N, Desta T, Dolbeare TA, Dotson N, Ebbert A, Fulfs E, Gee G, Gilbert TL, Goldy J, Gourley L, Gregor B, Gu G, Hall J, Haradon Z, Haynor DR, Hejazinia N, Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Howard R, Jochim J, Kinnunen M, Kriedberg A, Kuan CL, Lau C, Lee CK, Lee F, Luong L, Mastan N, May R, Melchor J, Mosqueda N, Mott E, Ngo K, Nyhus J, Oldre A, Olson E, Parente J, Parker PD, Parry S, Pendergraft J, Potekhina L, Reding M, Riley ZL, Roberts T, Rogers B, Roll K, Rosen D, Sandman D, Sarreal M, Shapovalova N, Shi S, Sjoquist N, Sodt AJ, Townsend R, Velasquez L, Wagley U, Wakeman WB, White C, Bennett C, Wu J, Young R, Youngstrom BL, Wohnoutka P, Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Hohmann JG, Hawrylycz MJ, Hevner RF, Molnár Z, Phillips JW, Dang C, Jones AR, Amaral DG, Bernard A, Lein ES. 2016. A comprehensive transcriptional map of primate brain development. Nature 535:367–375. 10.1038/nature18637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron-Cohen S, Auyeung B, Nørgaard-Pedersen B, Hougaard DM, Abdallah MW, Melgaard L, Cohen AS, Chakrabarti B, Ruta L, Lombardo MV. 2015. Elevated fetal steroidogenic activity in autism. Mol Psychiatry 20:369–376. 10.1038/mp.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai X, Cullen BR. 2007. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA 13:313–316. 10.1261/rna.351707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SH, Wu PS, Chou CH, Yan YT, Liu H, Weng SY, Yang-Yen HF. 2007. A knockout mouse approach reveals that TCTP functions as an essential factor for cell proliferation and survival in a tissue- or cell type-specific manner. Mol Biol Cell 18:2525–2532. 10.1091/mbc.e07-02-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho CK, Shan SJ, Winsor EJ, Diamandis EP. 2007. Proteomics analysis of human amniotic fluid. Mol Cell Proteomics 6:1406–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz JA, Johnson KL, Massingham LJ, Schaper J, Horlitz M, Cowan J, Bianchi M. 2011. Comparison of extraction techniques for amniotic fluid supernatant demonstrates improved yield of cell-free fetal RNA. Prenat Diagn 31:598–599. 10.1002/pd.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. 2012. STAR: ultrafast universal RNAseq aligner. Bioinformatics 29:15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dziadosz M, Basch RS, Young BK. 2016. Human amniotic fluid: a source of stem cells for possible therapeutic use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214:321–327. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edlow AG, Vora NL, Hui L, Wick HC, Cowan JM, Bianchi DW. 2014. Maternal obesity affects fetal neurodevelopmental and metabolic gene expression: a pilot study. PLoS One 9:1–11. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabory A, Jammes H, Dandolo L. 2010. The H19 locus: role of an imprinted non-coding RNA in growth and development. Bioessays 32:473–480. 10.1002/bies.200900170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hao Y, Crenshaw T, Moulton T, Newcomb E, Tycko B. 1993. Tumour-suppressor activity of H19 RNA. Nature 365:764–767. 10.1038/365764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4:44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui L, Bianchi DW. 2013. Recent advances in the prenatal interrogation of the human fetal genome. Trends Genet 29:84–91. 10.1016/j.tig.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui L, Slonim DK, Wick HC, Johnson KL, Bianchi DW. 2012. The amniotic fluid transcriptome: a source of novel information about human fetal development. Obstet Gynecol 119:111–118. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823d4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui L, Slonim DK, Wick HC, Johnson KL, Koide K, Bianchi DW. 2012. Novel neurodevelopmental information revealed in amniotic fluid supernatant transcripts from fetuses with trisomies 18 and 21. Hum Genet 131:1751–1759. 10.1007/s00439-012-1195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui L, Wick HC, Edlow AG, Cowan JM, Bianchi DW.2013. Global gene expression analysis of term amniotic fluid cell-free fetal Rna. Obstet Gynecol 121:1248–1254. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318293d70b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 1985. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. p 85–123. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasinska AJ. 2019. Biological resources for genomic investigation in the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus). p 16–28. In: Turner T, Schmitt C, Cramer J. Savanna monkeys: The genus chlorocebus. Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/9781139019941.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jasinska AJ, Schmitt CA, Service SK, Cantor RM, Dewar K, Jentsch JD, Kaplan JR, Turner TR, Warren WC, Weinstock GM, Woods RP, Freimer NB. 2013. Systems biology of the vervet monkey. ILAR J 54:122–143. 10.1093/ilar/ilt049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jasinska AJ, Zelaya I, Service SK, Peterson CB, Cantor RM, Choi O-W, DeYoung J, Eskin E, Fairbanks LA, Fears S, Furterer A, Huang YS, Ramensky V, Schmitt CA, Svardal H, Jorgensen MJ, Kaplan JR, Villar D, Aken BL, Flicek P, Nag R, Wong ES, Blangero J, Dyer TD, Bogomolov M, Benjamini Y, Weinstock GM, Dewar K, Sabatti C, Wilson RK, Jentsch JD, Warren W, Coppola G, Woods RP, Freimer NB. 2017. Genetic variation and gene expression across multiple tissues and developmental stages in a nonhuman primate. Nat Genet 49:1714–1721. 10.1038/ng.3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. 2007. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8:118–127. 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamath-Rayne BD, Du Y, Hughes M, Wagner EA, Muglia LJ, DeFranco EA, Whitsett JA, Salomonis N, Xu Y. 2015. Systems biology evaluation of cell-free amniotic fluid transcriptome of term and preterm infants to detect fetal maturity. BMC Med Genomics 8:1–11. 10.1186/s12920-015-0138-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang JH, Park HJ, Jung YW, Shim SH, Sung SR, Park JE, Cha DH, Ahn EH. 2015. Comparative transcriptome analysis of cell-free fetal RNA from amniotic fluid and RNA from amniocytes in uncomplicated pregnancies. PLoS One 10:1–13. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavanagh K, Dozier BL, Chavanne TJ, Fairbanks LA, Jorgensen MJ, Kaplan JR. 2011. Fetal and maternal factors associated with infant mortality in vervet monkeys. J Med Primatol 40:27–36. 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendziorski JA, Sherrill C, Davis AT, Kavanagh K. 2019. Microbial translocation into amniotic fluid of vervet monkeys is common and unrelated to adverse infant outcomes. J Med Primatol 48:367–369. 10.1111/jmp.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keniry A, Oxley D, Monnier P, Kyba M, Dandolo L, Smits G, Reik W. 2012. The H19 lincRNA is a developmental reservoir of miR-675 that suppresses growth and Igf1r. Nat Cell Biol 14:659–665. 10.1038/ncb2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larrabee PB, Johnson KL, Lai C, Ordovas J, Cowan JM, Tantravahi U, Bianchi DW. 2005. Global gene expression analysis of the living human fetus using cell-free messenger RNA in amniotic fluid. JAMA 293:836–842. 10.1001/jama.293.7.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansell T, Novakovic B, Meyer B, Rzehak P, Vuillermin P, Ponsonby A-L, Collier F, Burgner D, Saffery R, Ryan J, BIS Investigator team. 2016. The effects of maternal anxiety during pregnancy on IGF2/H19 methylation in cord blood. Transl Psychiatry 6:1–7. 10.1038/tp.2016.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matouk IJ, Halle D, Raveh E, Gilon M, Sorin V, Hochberg A. 2016. The role of the oncofetal H19 lncRNA in tumor metastasis: orchestrating the EMT-MET decision. Oncotarget 7:3748–3765. 10.18632/oncotarget.6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. 2019. PHS policy on humane care and use of laboratory animals. [Cited 13 January 2020]. Available at: https://olaw.nih.gov/policies-laws/phs-policy.htm.

- 35.Okamoto K, Morison IM, Taniguchi T, Reeve AE. 1997. Epigenetic changes at the insulin-like growth factor II/H19 locus in developing kidney is an early event in Wilms tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:5367–5371. 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng X, Thierry-Mieg J, Thierry-Mieg D, Nishida A, Pipes L, Bozinoski M, Thomas MJ, Kelly S, Weiss JM, Raveendran M, Muzny D, Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Schroth GP, Katze MG, Mason CE. 2015. Tissue-specific transcriptome sequencing analysis expands the non-human primate reference transcriptome resource (NHPRTR). Nucleic Acids Res 43 D1:D737–D742. 10.1093/nar/gku1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petry CJ, Seear RV, Wingate DL, Acerini CL, Ong KK, Hughes IA, Dunger DB. 2011. Maternally transmitted foetal H19 variants and associations with birth weight. Hum Genet 130:663–670. 10.1007/s00439-011-1005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reik W, Walter J. 2001. Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nat Rev Genet 2:21–32. 10.1038/35047554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slonim DK, Koide K, Johnson KL, Tantravahi U, Cowan JM, Jarrah Z, Bianchi DW. 2009. Functional genomic analysis of amniotic fluid cell-free mRNA suggests that oxidative stress is significant in Down syndrome fetuses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9425–9429. 10.1073/pnas.0903909106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steenman MJ, Rainier S, Dobry CJ, Grundy P, Horon IL, Feinberg AP. 1994. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 is linked to reduced expression and abnormal methylation of H19 in Wilms’ tumour. Nat Genet 7:433–439. 10.1038/ng0794-433. Erratum: Nat Genet 1994 8:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su R, Wang C, Feng H, Lin L, Liu X, Wei Y, Yang H. 2016. Alteration in expression and methylation of IGF2/H19 in placenta and umbilical cord blood are associated with macrosomia exposed to intrauterine hyperglycemia. PLoS One 11:1–14. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148399.d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai M-J, Yang-Yen H-F, Chiang M-K, Wang M-J, Wu S-S, Chen S-H. 2014. TCTP is essential for β-cell proliferation and mass expansion during development and β-cell adaptation in response to insulin resistance. Endocrinology 155:392–404. 10.1210/en.2013-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vangeel EB, Izzi B, Hompes T, Vansteelandt K, Lambrechts D, Freson K, Claes S. 2015. DNA methylation in imprinted genes IGF2 and GNASXL is associated with prenatal maternal stress. Abstracts of the 45th annual meeting of the International Society of Psychoneuroendocrinology Stress and the Brain: From Fertility to Senility John McIntyre Conference Centre, Edinburgh, 8–10 September 2015. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 61:16 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warren WC, Jasinska AJ, García-Pérez R, Svardal H, Tomlinson C, Rocchi M, Archidiacono N, Capozzi O, Minx P, Montague MJ, Kyung K, Hillier LW, Kremitzki M, Graves T, Chiang C, Hughes J, Tran N, Huang Y, Ramensky V, Choi OW, Jung YJ, Schmitt CA, Juretic N, Wasserscheid J, Turner TR, Wiseman RW, Tuscher JJ, Karl JA, Schmitz JE, Zahn R, O'Connor DH, Redmond E, Nisbett A, Jacquelin B, Müller-Trutwin MC, Brenchley JM, Dione M, Antonio M, Schroth GP, Kaplan JR, Jorgensen MJ, Thomas GW, Hahn MW, Raney BJ, Aken B, Nag R, Schmitz J, Churakov G, Noll A, Stanyon R, Webb D, Thibaud-Nissen F, Nordborg M, Marques-Bonet T, Dewar K, Weinstock G, Wilson RK, Freimer NB. 2015. The genome of the vervet (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus). Genome Res 25:1921–1933. 10.1101/gr.192922.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zwemer LM, Hui L, Wick HC, Bianchi DW. 2014. RNAseq and expression microarray highlight different aspects of the fetal amniotic fluid transcriptome. Prenat Diagn 34:1006–1014. 10.1002/pd.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]