Abstract

Background

Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CC) is a rare liver malignancy that contains features of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma (MFCCC). Three classification systems for HCC-CC are described in literature and the majority of these tumors appear to be of the transitional type. The aim of this study is to evaluate the characteristics of transitional HCC-CC and to compare long-term oncological outcomes with HCC and MFCCC in surgically treated patients.

Summary

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies analyzing demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with transitional HCC-CC and evaluating treatments and outcomes associated with this neoplasm. Only comparative, retrospective analyses were included. A total of 14 studies, involving 13,613 patients with primary liver malignancy, were analyzed. All patients underwent surgery, either liver resection or transplantation. Four hundred and thirty-seven patients were affected by transitional HCC-CC (3.2%). For further analysis, patients with transitional HCC-CC were divided into 2 groups, the resection group and the transplantation group. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) of these patients were analyzed and compared to long-term oncological outcomes of patients with HCC and/or MFCCC, who underwent the same treatment. In the resection group, DFS rate at 5-year was 15, 31.6, and 20.3% for patients with transitional HCC-CC, HCC, and MFCCC, respectively; OS rate at 5-year was 32.7, 47.5, and 30.3% for patients with transitional HCC-CC, HCC, and MFCCC, respectively. In the transplantation group, DFS rate at 5-year was 40.9 and 87.4% for patients with transitional HCC-CC and HCC, respectively; OS rate at 5-year was 49.4 and 80.3% for patients with transitional HCC-CC and HCC, respectively.

Key Messages

Transitional HCC-CC patients have significantly worse DFS and OS rates compared to HCC patients in both the resection group and the transplantation group. However, in the resection group, both DFS and OS rates of transitional HCC-CC patients are not statistically different from those of MFCCC patients.

Keywords: Liver neoplasms, Hepatocholangiocarcinoma, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CC) is an uncommon variety of primary liver malignancy containing histopathological characteristics of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma (MFCCC) [1, 2, 3]. This rare entity of primary liver cancer was first reported by Wells in 1903. Its incidence, reported in literature, varies amongst different studies and regions between 0.4 and 14.2% of all primary liver carcinomas [2, 4, 5, 6, 7]. HCC-CC is commonly considered an aggressive liver malignancy associated with poor long-term oncological outcomes [8] and misdiagnosed, at the pre-operative radiological examinations, as a more common form of liver malignancy such as HCC or MFCCC. Case reports and single-center, retrospective analyses based on small series of patients have focused on HCC-CC. However, etiology, demographic characteristics, clinical features, and appropriate treatment for HCC-CC remain ill-defined and poorly understood, reflecting the uncommonness of this tumor as well as the lack of comprehensive reviews on HCC-CC. The purpose of this study is to evaluate clinical characteristics of HCC-CC and compare long-term oncological outcomes with HCC and MFCCC in surgically treated patients.

Classification

The first classification of HCC-CC was developed in 1949 by Allen and Lisa [6] in their examination of 5 livers that displayed histopathological evidence of both HCC and MFCCC. They classified HCC-CC into 3 types: type A (HCC and MFCCC are present at different sites within the same liver), type B (HCC and MFCCC are present at adjacent sites), type C (HCC and MFCCC are combined within the same tumor). In a subsequent review of 24 cases, Goodman et al. [1] developed a more inclusive classification system. Similar to the first classification system, they divided HCC-CC into 3 types: type I (“collision tumor”; a coincidental occurrence of HCC and MFCCC within the same liver), type II (“transitional tumor”; in which there is a transition from elements of HCC to elements typical of MFCCC), type III (“fibrolamellar tumor”, which resembles the fibrolamellar sub-type of HCC; however, it contains mucin-producing pseudoglands). The last classification system was introduced in 2010 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [9], which divides HCC-CC into classical type (similar to Allen and Lisa [6] type C), and sub-types with stem-cell features. However, recent studies showed that stem-cell features can be found in other types of primary liver malignancies, therefore the WHO classification groups are not as distinctly separable as previously thought [10]. Even though HCC and MFCCC may develop autonomously in the same liver, the majority of HCC-CC appears to be Goodman transitional type (type II)/Allen and Lisa [6] type C/WHO classical type tumors [11]. In our systematic literature search, we considered studies focused on this type, from now mentioned as transitional HCC-CC.

Molecular Characteristics

The genesis and development of transitional HCC-CC may be elucidated by the theory of stem cells and its origin from a bi-potent hepatic progenitor cell which differentiates into both hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells [12, 13, 14]. Hepatic progenitor cell and stem-cell markers which have been studied in relation to transitional HCC-CC include CD133, CD13, CD90, CD44, epithelial cell adhesion molecule, nuclear cell adhesion molecule(CD56), OV6, c-kit, YAP1, SALL4, and Delta-like 1 homolog [15, 16, 17, 18].

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed according to PRISMA guidelines [19].

Literature Search

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to identify relevant articles published between April 2002 and September 2018 analyzing demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with a diagnosis of transitional HCC-CC and evaluating possible treatment methods and long-term oncological outcomes associated with this neoplasm. Comparative, retrospective analyses were included in the review. No restriction was set for number, age or sex of the patients. The search was limited to articles in English.

The following combinations of terms were used for the search strategy:

“Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma” AND “HCC” OR “cholangiocellular carcinoma” OR “intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma”;

“Mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma” AND “HCC” OR “cholangiocellular carcinoma” OR “intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma”;

“HCC-CC” AND “HCC” OR “cholangiocellular carcinoma” OR “intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma.”

Both free-text and medical subject heading (MeSH) searches were used for keywords. The search was further broadened by extensive cross-checking of all the references in the articles retrieved which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, to identify eventual additional non-indexed literature.

Study Selection Criteria and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

The authors screened data from studies identified in the electronic search, and the following inclusion criteria were set to include the studies in the review:

Studies focused on transitional type HCC-CC;

Retrospective analyses comparing disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients with transitional HCC-CC and patients with HCC and/or patients with MFCCC;

Comparative, retrospective analyses evaluating surgical treatments for transitional HCC-CC (liver resection or liver transplantation);

Comparative, retrospective analyses reporting at least one of the following characteristics of transitional HCC-CC: viral markers (HBsAg positive, anti-hepatitis C virus [HCV] positive), background of liver cirrhosis, tumor markers, tumor size, number of tumor nodules (single, multiple), lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion (micro-vascular, macro-vascular).

The exclusion criteria were set as follows:

Non-relevant topic papers or when outcomes, surgical treatment or transitional HCC-CC characteristics were not included;

Studies in which the classification system was not specified;

Non-comparative studies;

Studies analyzing non-surgical treatments;

Duplicate studies;

Studies not written in English;

Studies published prior to April 2002;

Studies assessed as at “critical risk” of bias.

To assess bias in the non-randomized observational studies included in our systematic review, the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies − of Interventions tool [20] was used. The risk of bias was assessed for the following 7 domains: pre-intervention (confounding and participants selection bias), at intervention (bias related to classification of intervention), post-intervention (bias due to deviation from intended intervention and missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes and selection of the reported results). The categories for risk of bias judgments are “low risk,” “moderate risk,” “serious risk” and “critical risk” of bias. If a study was identified as non-inferior to a randomized trial in all domains, the risk of bias was considered low. Studies assessed as at “critical risk” of bias were excluded from the systematic review.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, clinical-laboratoristic, histopathological characteristics, long-term oncological outcomes (DFS and OS) and follow-up were analyzed using basic statistics. All categorical results are presented as number and percentage. All continuous variables are presented as mean, SD from the mean, and 95% CI. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.050. Data analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Studies Included

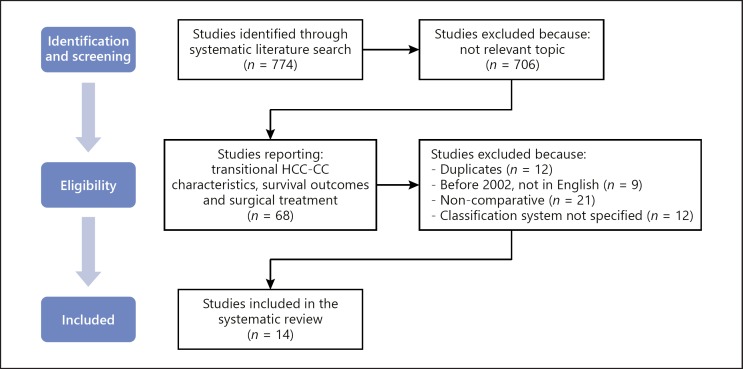

Firstly, current literature was reviewed and a total of 774 studies were identified through systematic literature search. Seven hundred and six studies were excluded because they were not eligible on the basis of the pre-established inclusion criteria. After elimination of duplicates (n = 12), the remaining 56 studies were reviewed. Based on the methodological exclusion criteria, 42 additional studies were excluded. The remaining 14 studies [2, 4, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] were included in the review and analyzed (Fig. 1). All of the selected studies were comparative, retrospective analyses (Table 1). Any disagreement was resolved by consensus of the authors.

Fig. 1.

Selection of studies. This flow-chart details the process used for the selection of studies included in the systematic review. Initially, the literature search yielded 774 studies. Seven hundred and six studies were excluded because they did not report transitional HCC-CC characteristics, surgical treatment or survival outcomes. Fifty-four duplicate, non-comparative, not specifying the classification system, not in English language, published before 2002 studies were excluded. Eventually, 14 studies were selected and analyzed by the authors. HCC-CC, hepatocholangiocarcinoma.

Table 1.

Studies included in the review

| Authors | Publication year | Journal | Country | HCC-CC patients, n | HCC patients, n | MFCCC patients, n | Resected HCC-CC patients | Transplanted HCC-CC patients | Mean follow-up, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. [21] | 2018 | Chin J Cancer Res | China | 35 | 908 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 24 |

| Chang et al. [22] | 2017 | Ann Transplant | Taiwan | 11 | 290 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 23.9 |

| Yoon et al. [23] | 2016 | J Gastrointest Surg | Korea | 53 | 1,452 | 149 | 53 | 0 | 31.2 |

| Lee et al. [24] | 2014 | Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int | Korea | 42 | 90 | 45 | 42 | 0 | 21.6 |

| Kim et al. [25] | 2014 | Eur J Surg Oncol | Korea | 30 | 0 | 77 | 30 | 0 | 22 |

| Sapisochin et al. [26] | 2014 | Ann Surg | Spain | 15 | 84 | 27 | 0 | 15 | 51 |

| Yin et al. [27] | 2012 | Ann Surg Oncol | China | 103 | 6,679 | 389 | 103 | 0 | 25 |

| Sapisochin et al. [28] | 2011 | Liver Transpl | Spain | 10 | 30 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 32 |

| Lee et al. [29] | 2011 | J Clin Gastroenterol | Korea | 30 | 60 | 60 | 30 | 0 | 18.3 |

| Zuo et al. [30] | 2007 | Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int | China | 15 | 132 | 44 | 15 | 0 | − |

| Tang et al. [31] | 2006 | J Gastrointest Surg | Japan | 13 | 509 | 41 | 13 | 0 | 57.7 |

| Lee et al. [4] | 2006 | Surg Today | Korea | 33 | 832 | 78 | 33 | 0 | 46.8 |

| Yano et al. [32] | 2003 | Jpn J Clin Oncol | Japan | 26 | 1,093 | 53 | 26 | 0 | 33.2 |

| Jarnagin et al. [2] | 2002 | Cancer | USA | 21 | 27 | 23 | 21 | 0 | 38.3 |

This table shows the characteristics of all the comparative, retrospective analyses included in the systematic review. HCC-CC, hepatocholangiocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MFCCC, mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma.

Patients Included

A total of 13,613 patients with a diagnosis of primary liver malignancy (HCC, MFCCC or transitional HCC-CC) treated with surgery, either liver resection or liver transplantation, were analyzed. The majority of the selected patients were affected by HCC (89.5%). Nine hundred and ninety patients were affected by MFCCC (7.3%). Four hundred and thirty-seven patients were affected by transitional HCC-CC (3.2%).

Transitional HCC-CC Characteristics

Demographic and Clinical-Laboratoristic Characteristics

The mean age of the 437 patients with transitional HCC-CC at the time of surgical treatment was 55.7 years (49–61). Three hundred and forty-five patients were male (79%). Two hundred and sixty-four patients were HBsAg positive (60.4%); 39 patients were anti-HCV positive (8.9%). The mean alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 588 ng/mL (normal <5 ng/mL). The mean carcinoembryonic antigen level was 4 ng/mL (normal <5 ng/mL). The mean carbohydrate antigen 19.9 level was 73 UI/mL (normal <37 UI/mL; Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of resected and transplanted transitional HCC-CC patients

| Transitional HCC-CC characteristics | n (%) | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Studies with missing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | − | 55.7 | 3.9 | 53.4–58 | None |

| Gender, male | 345 (79) | − | − | − | None |

| Viral markers | |||||

| HBsAg + | 264 (60.4) | − | 23.9 | 38.7–66.4 | None |

| Anti–HCV + | 39 (8.9) | − | 18.6 | 5.5–28 | [21] |

| Tumor markers | |||||

| Serum AFP, ng/mL | − | 588 | 16.9 | 140–1,321 | [21, 24] |

| Serum CEA, ng/mL | − | 4 | 1.3 | 2.3–5.6 | [21, 26, 27, 28, 29] |

| Serum Ca 19.9, UI/mL | − | 73 | 2.1 | 52–100 | [21, 26, 27, 28, 29] |

| Cirrhosis | 226 (51.7) | − | 27.4 | 40.9–77.7 | [22, 23, 28] |

| Tumor size, cm | − | 5.3 | 1.8 | 4–6.4 | [24, 30] |

| Tumor number | |||||

| Single | 291 (66.6) | − | 24 | − | [28, 29, 31, 32] |

| Multiple | 146 (33.4) | − | 4.5 | − | [28, 29, 31, 32] |

| Lymph nodes MTX | 35 (8) | − | 8.9 | 3.1–15.1 | [25, 26, 29] |

| Vascular invasion | |||||

| Macro-vascular | 49 (11.2) | − | 9.6 | − | [2, 28, 29] |

| Micro-vascular | 127 (29) | − | 3.6 | − | [23, 27, 29, 30] |

This table details the analysis of the pre-operative and post-operative characteristics of 437 patients with transitional HCC-CC treated with either liver resection or transplantation selected from the studies included in the systematic review. Demographic, clinical, laboratoristic, and histopathological characteristics were evaluated.

HCC-CC, hepatocholangiocarcinoma; HBsAg +, hepatitis B virus infection; Anti-HCV+, hepatitis C virus infection; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; Ca 19.9, carbohydrate antigen 19.9; MTX, metastases.

Histopathological Characteristics

Two hundred and twenty-six patients with transitional HCC-CC had a histopathological diagnosis of liver cirrhosis (51.7%). The mean tumor size was 5.3 cm. Two hundred and ninety-one patients were affected by a single tumor (66.6%); 146 patients were affected by multiple tumors (33.4%). Thirty-five patients were affected by lymph nodes metastases (8%). Forty-nine patients had macro-vascular invasion (11.2%) and 127 patients had micro-vascular invasion (29%; Table 2).

Transitional HCC-CC Treatment and Oncological Outcomes

All the studies included in the review reported the type of surgical treatment for transitional HCC-CC. The majority of the selected patients underwent liver resection (91.8%); 36 patients underwent liver transplantation (8.2%). For further analysis, patients with transitional HCC-CC were divided into 2 groups, the resection group and the transplantation group. DFS and OS of these patients were compared with the long-term oncological outcomes of patients with HCC and/or MFCCC, who underwent the same treatment.

Liver Resection

Four hundred and one patients with transitional HCC-CC underwent liver resection and their oncological outcomes were compared with the outcomes of 11,782 patients with HCC and 990 patients with MFCCC who underwent the same treatment. At a mean follow-up of 31.8 months, 247 patients with transitional HCC-CC (61.6%) had tumor recurrence. Ninety-five patients had liver recurrence (38.5%); 57 patients had extra-hepatic recurrence (23%); in 95 patients site was not specified (38.5%). Eleven patients were treated with radio-frequency ablation, 2 patients were treated with percutaneous ethanol injection, 66 patients were treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, 131 patients were treated with chemotherapy, 17 patients were treated with a liver re-resection, 20 patients were not treated for recurrence. At a mean follow-up of 31.8 months, 5,554 patients with HCC (47.2%) had tumor recurrence, 516 patients with MFCCC (52.2%) had tumor recurrence. The mean DFS was 14.2, 43.1, and 17.8 months for transitional HCC-CC, HCC, and MFCCC, respectively (Table 3). The mean DFS rate at 1-, 3-, and 5-year was 46.5, 24.6, and 15% for patients with transitional HCC-CC; 72.8, 47.4, and 31.6% for patients with HCC; 59.6, 34.2, and 20.3% for patients with MFCCC (Table 3). At a mean follow-up of 31.8 months, 228 patients with transitional HCC-CC (56.9%), 4,179 patients with HCC (35.5%), and 374 patients with MFCCC (35.1%) died. The mean OS was 37.1, 66.8, and 32.2 months for transitional HCC-CC, HCC, and MFCCC, respectively (Table 3). The mean OS rate at 1-, 3-, and 5-year was 66.6, 41.5, and 32.7% for patients with transitional HCC-CC; 84.4, 65.2, and 47.5% for patients with HCC; 66.6, 37.8, and 30.3% for patients with MFCCC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of long-term oncological outcomes between resected patients with transitional HCC-CC, HCC, and MFCCC

| Outcomes | Transitional HCC-CC, mean (95% CI) | HCC, mean (95% CI) | p value* | MFCCC, mean (95% CI) | p value° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFS, months | 14.2 (0.3–28.1) | 43.1 (18–68.2) | 0.001 | 17.8 (4.4–31.2) | 0.061 |

| DFS rate, % | |||||

| 1-year | 46.5 (33.1–59.8) | 72.8 (32.4–113.1) | 0.030 | 59.6 (33.4–85.8) | 0.074 |

| 3-year | 24.6 (18.8–30.3) | 47.4 (21.8–72.9) | 0.022 | 34.2 (17.9–50.3) | 0.078 |

| 5-year | 15 (0.9–28.9) | 31.6 (10.5–52.6) | 0.001 | 20.3 (3.7–28.2) | 0.275 |

| OS, months | 37.1 (22.4–51.7) | 66.8 (47.4–86) | 0.016 | 32.2 (19.8–44.4) | 0.375 |

| OS rate, % | |||||

| 1-year | 66.6 (54.7–78.4) | 84.4 (79.4–89.4) | 0.032 | 66.6 (40.5–92.6) | 0.089 |

| 3-year | 41.5 (30.5–52.4) | 65.2 (56.5–73.9) | 0.017 | 37.8 (14.4–61.1) | 0.057 |

| 5-year | 32.7 (20.5–44.8) | 47.5 (37.5–57.4) | 0.024 | 30.3 (17.7–42.7) | 0.065 |

This table details the long-term oncological outcomes of patients who underwent liver resection. Mean DFS and OS are reported and compared between the 3 different types of primary liver malignancy.

p value*: correlation between transitional HCC-CC and HCC; p value°: correlation between transitional HCC-CC and MFCCC. Statistically significant values are expressed in bold.

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; HCC-CC, hepatocholangiocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MFCCC, mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma.

Liver Transplantation

Thirty six patients with transitional HCC-CC underwent liver transplantation and their oncological outcomes were compared with the outcomes of 404 patients with HCC who underwent the same treatment. None of the patients with MFCCC underwent liver transplantation. At a mean follow-up of 35.6 months, 13 patients with transitional HCC-CC (36.1%) had tumor recurrence. Five patients had liver recurrence (38.5%) and 8 patients had extra-hepatic recurrence (61.5%). Six patients were treated with chemotherapy, 7 patients were not treated for recurrence. At a mean follow-up of 35.6 months, 31 patients with HCC (7.7%) had tumor recurrence. The mean DFS rate at 1-, 3-, and 5-year was 69, 58.4, and 40.9% for patients with transitional HCC-CC; 93.6, 92.2, and 87.4% for patients with HCC (Table 4). At a mean follow-up of 35.6 months, 15 patients with transitional HCC-CC (41.6%) and 65 patients with HCC (16.1%) died. The mean OS rate at 1-, 3-, and 5-year was 84, 65.9, and 49.4% for patients with transitional HCC-CC; 95.4, 83.7, and 80.3% for patients with HCC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of long-term oncological outcomes between transplanted patients with transitional HCC-CC and HCC

| Outcomes | Transitional HCC-CC, mean (95% CI) | HCC, mean (95% CI) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFS rate, % | |||

| 1-year | 69 (58–80) | 93.6 (47.8–139.3) | 0.001 |

| 3-year | 58.4 (46.7–78.6) | 92.2 (72.3–112) | 0.037 |

| 5-year | 40.9 (35–46.7) | 87.4 (31.4–143.3) | 0.001 |

| OS rate, % | |||

| 1-year | 84 (70.1–97.8) | 95.4 (83.5–107.2) | 0.055 |

| 3-year | 65.9 (55.5–76.2) | 83.7 (36.9–130.4) | 0.050 |

| 5-year | 49.4 (25.3–73.3) | 80.3 (40.9–119.5) | 0.018 |

This table details the long-term oncological outcomes of patients who underwent liver transplantation. Mean DFS and OS are reported and compared between transitional HCC-CC and HCC.

p value*: correlation between transitional HCC-CC and HCC. Statistically significant values are expressed in bold.

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; HCC-CC, hepatocholangiocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Transitional HCC-CC patients have significantly worse DFS and OS rates compared to HCC patients in both the resection group and the transplantation group (5-year DFS: 15 vs. 31.6%, p = 0.001; 5-year OS: 32.7 vs. 47.5%, p = 0.024 and 5-year DFS: 40.9 vs. 87.4%, p = 0.001; 5-year OS: 49.4 vs. 80.3%, p = 0.018, respectively). However, in the resection group, both DFS and OS rates of transitional HCC-CC patients are not statistically different from those of MFCCC patients (5-year DFS: 15 vs. 20.3%, p = 0.275; 5-year OS: 32.7 vs. 30.3%, p = 0.065).

Discussion

Risk Factors

The varying incidence of primary liver malignancies in diverse geographical areas reflects different levels of risk factors in different populations. Chronic liver damage and subsequent liver cirrhosis represent strong oncogenic factors. Hepatitis B virus, HCV, and alcohol abuse represent the most relevant etiological agents. Hepatitis B virus infection rates are highly prevalent in China and Southeast Asia, where infection is acquired at a young age, resulting in a high incidence of HCC [33]. On the contrary, in North America and Europe, HCV infection and alcohol intake represent the most important risk factors for the development of HCC [34]. In three studies [35, 36, 37], transitional HCC-CC is considered a variant of classic HCC with cholangiocellular characteristics and no significant differences as regards etiological factors between transitional HCC-CC and HCC have been found. The low incidence of HCV infection in transitional HCC-CC patients analyzed in our review can be explained by the fact that the majority of the studies selected are retrospective analyses from Asian centers.

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of transitional HCC-CC is similar to that of HCC and MFCCC. Usually, this rare form of neoplasm is clinically silent until advanced states. Symptoms include: jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, weight loss, pruritus, ascites, acute cholangitis, fever, and hepatomegaly [3]. In the majority of patients with primary liver malignancies, a series of abnormal tumor markers can be found in the serum. Usually, elevation of AFP can be detected in HCC patients, while carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 can reach high concentrations in MFCCC patients. Elevation of these 3 tumor markers in transitional HCC-CC has been reported in three studies [24, 38, 39]; moreover, 2 of the selected studies [29, 31] reported extremely high AFP serum levels in transitional HCC-CC patients, which might have affected the overall mean value in our analysis. Although these 3 tumor markers are not specific for transitional HCC-CC and may be elevated even in non-malignant conditions or be normal despite malignancy, a simultaneous increase of their levels in a patient with a liver mass detected on imaging studies can strongly suggest a diagnosis of transitional HCC-CC [31]. In primary liver malignancies, the radiographic imaging represents one of the most important tool for the selection of patients for treatment. Imaging studies help in detecting extended intra-hepatic disease, vascular invasion, liver cirrhosis, and extra-hepatic involvement. Historically, the pre-operative diagnosis of transitional HCC-CC has been subtle on radiographic imaging and the majority of cases were initially misdiagnosed as either HCC or MFCCC, while correct diagnosis was only reached in surgical resection specimens. Transitional HCC-CC is considered to have heterogeneous imaging characteristics with overlapping features of both HCC and MFCCC. Precise pre-operative diagnosis is crucial, especially discrimination from HCC, as it may be influential in determining the optimal modality of treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Liver Resection

Surgery represents the only curative treatment for HCC-CC [3]. Many factors may influence the feasibility of surgery including liver background status, general medical conditions of the patient, tumor dimension, and extent of vascular invasion. Garancini et al. [40] reported that invasive treatment for HCC-CC was significantly associated with prolonged survival compared to non-surgical treatment (p < 0.001) and minor and major hepatectomies were independently associated with better OS. Moreover, major hepatectomy for HCC-CC was associated with higher 5-year OS and DFS rates compared to minor hepatectomy; therefore, it should be considered the best surgical approach. Ma and Chok [41] reported that in patients with multifocal HCC-CC, a resection margin >1 cm was associated with better 1-year DFS (40 vs. 0%, p = 0.012), assuming that a wide resection margin would remove residual satellite tumor cells and micro-tumors located in the same hepatic area. Transitional HCC-CC resembles HCC in terms of portal and hepatic vein infiltration and MFCCC in terms of lymph node invasion [1]. Three studies [3, 24, 39] recommended liver resection with regional lymph node dissection for patients with transitional HCC-CC for oncological radicality; however, whether lymphadenectomy improves prognosis or not has not been established [35, 36, 42].

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation is a well-established surgical option for patients with HCC; however, whether this type of treatment for HCC-CC improves long-term oncological outcomes when compared to conventional liver resection, remains controversial. Few studies focused on patients with HCC-CC undergoing transplantation. This type of neoplasm has been described as an aggressive tumor with poor survival outcomes and high recurrence rates after liver transplantation [28, 37] and usually patients undergoing transplantation were radiologically misdiagnosed as HCC at the pre-operative imaging. On the contrary, Ma et al. [43] selected 54 patients with a diagnosis of either HCC-CC or MFCCC and performed a propensity score match in a 1:5 ratio, dividing the patients into transplantation and resection groups, reporting significantly better 5-year OS rates for transplanted patients (77.8 vs. 36.6%, p = 0.013). However, significant differences between the 2 groups were observed, as patients treated with liver transplantation were younger and with earlier tumor staging. Moreover, Garancini et al. [40] reported that, in the univariate analysis, liver transplantation for HCC-CC was associated with higher 5-year OS rates compared to liver resection (p = 0.039). However, liver transplantation was mostly performed in patients with small tumors (<3 cm), whereas resection was performed for larger tumors (>3 cm). Thus far, the role and indications of liver transplantation for HCC-CC have yet to be defined.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with transitional HCC-CC is generally considered poor and it largely depends on the disease stage at the time of diagnosis and the recurrence rate after surgical treatment. The extent of disease at diagnosis is the predominant determinant of resectability. Usually, patients with transitional HCC-CC present with relatively large tumors, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion, and satellite nodules, similar to patients with MFCCC, requiring more extended surgical procedures to obtain oncological radicality [2]. The rate of lymph node invasion in patients with transitional HCC-CC reported in our systematic review was relatively low (8%); however, the majority of studies selected were performed in Asian centers; therefore it is difficult to say if the same result may be applicable to Western patients also. A retrospective analysis performed by Garancini et al. [40], which was not included in our systematic review because it did not state the classification method used for the diagnosis of HCC-CC, analyzed the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, mostly composed of Western patients, and identified 465 patients with a diagnosis of HCC-CC. Amongst 54 patients with HCC-CC who underwent lymph node dissection, 24.1% had lymph node metastases, and the absence of lymph node invasion was considered a positive prognostic factor (p < 0.001). The most common extra-hepatic recurrence sites are lymph nodes, which are seen in MFCCC patients. Usually these patients receive systemic therapy of best supportive care with a limited impact on survival [24]. The survival rates of patients with transitional HCC-CC or MFCCC were lower compared to patients with HCC in all the analyzed studies, suggesting that the clinical behavior of transitional HCC-CC more closely resembles that of MFCCC. This indicates that in HCC-CC, the cholangiocellular component rather than the hepatocellular component dictates the outcome.

Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, this systematic review was subject to limitations due to retrospective works using observational data collected at a specific moment in various centers, with no updated follow-up. Second, general medical conditions and liver background status of the selected patients might have influenced the long-term oncological results. Final, the analysis of transitional HCC-CC characteristics and outcomes was limited by a lack of data in some of the studies reviewed. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, the current systematic review includes the largest published number of patients with a diagnosis of transitional HCC-CC treated with surgery, either liver resection or liver transplantation.

Conclusions

In summary, transitional HCC-CC patients have significantly worse DFS and OS rates compared to HCC patients in both the resection group and the transplantation group. However, in the resection group, both DFS and OS rates of transitional HCC-CC patients are not statistically different from those of MFCCC patients. Further, multi-institutional, case-matched analyses with HCC and MFCCC patients are necessary to better evaluate clinical characteristics of transitional HCC-CC patients and define prognostic factors and optimal treatment of this rare entity of primary liver malignancy.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to disclose.

Author Contributions

D.G. and M.D.: study conception and design. D.G. and M.D: data acquisition. D.G., M.D., A.L., L.T., and A.A.: risk-of-bias assessment. D.G., M.D., A.L., L.T., and A.A.: analysis and interpretation of data. D.G. and M.D.: drafting of manuscript. All authors: critical revision and final approval.

Acknowledgements

This study did not receive any grant support or assistance.

References

- 1.Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Langloss JM, Sesterhenn IA, Rabin L. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. A histologic and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1985 Jan;55((1)):124–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850101)55:1<124::aid-cncr2820550120>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarnagin WR, Weber S, Tickoo SK, Koea JB, Obiekwe S, Fong Y, et al. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2002 Apr;94((7)):2040–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassahun WT, Hauss J. Management of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Clin Pract. 2008 Aug;62((8)):1271–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee WS, Lee KW, Heo JS, Kim SJ, Choi SH, Kim YI, et al. Comparison of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2006;36((10)):892–7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee CC, Wu CY, Chen JT, Chen GH. Comparing combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: a clinicopathological study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002 Nov-Dec;49((48)):1487–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen RA, Lisa JR. Combined liver cell and bile duct carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1949 Jul;25((4)):647–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh KC, Lee H, Choi MS, Lee JH, Paik SW, Yoo BC, et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2005 Jan;189((1)):120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stavraka C, Rush H, Ross P. Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC): an update of genetics, molecular biology, and therapeutic interventions. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2018 Dec;6:11–21. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S159805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH. 4th ed. Fr IARC; 2010. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System; pp. pp. 134–46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunt E, Aishima S, Clavien P, Fowler K, Gores G, Gouw A, et al. cHCC-CCA: Consensus Terminology for Primary Liver Carcinomas With Both Hepatocytic and Cholangiocytic Differetation. HHS Public Access. 2019;68:113–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.29789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taguchi J, Nakashima O, Tanaka M, Hisaka T, Takazawa T, Kojiro M. A clinicopathological study on combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996 Aug;11((8)):758–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoyama M, Hata M, Yamanegi K, Yamada N, Ohyama H, Hirano H, et al. Expression of both hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma phenotypes in hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma components in combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Med Mol Morphol. 2012 Dec;45((1)):7–13. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh MM. Pathology of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Sep;25((9)):1485–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Park C, Han KH, Choi J, Kim YB, Kim JK, et al. Primary liver carcinoma of intermediate (hepatocyte-cholangiocyte) phenotype. J Hepatol. 2004 Feb;40((2)):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim R, Kim SB, Cho EH, Park SH, Park SB, Hong SK, et al. CD44 expression in patients with combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015 Jul;89((1)):9–16. doi: 10.4174/astr.2015.89.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka Y, Aishima S, Kohashi K, Okumura Y, Wang H, Hida T, et al. Spalt-like transcription factor 4 immunopositivity is associated with epithelial cell adhesion molecule expression in combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2016 Apr;68((5)):693–701. doi: 10.1111/his.12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akiba J, Nakashima O, Hattori S. Clinicopathologic Analysis of Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma According to the Latest WHO Classification. 2013;37:496–505. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827332b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeda H, Harada K, Sato Y, Sasaki M, Yoneda N, Kitamura S, et al. Clinicopathologic Significance of Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma With Stem Cell Subtype Components With Reference to the Expression of Putative Stem Cell Markers. 2013;140:329–41. doi: 10.1309/AJCP66AVBANVNTQJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul;6((7)):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 Oct;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Wu X, Bi X, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Lu H, et al. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of four rare subtypes of primary liver carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018 Jun;30((3)):364–72. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CC, Chen YJ, Huang TH, Chen CH, Kuo FY, Eng HL, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: experience of a single center. Ann Transplant. 2017 Feb;22:115–20. doi: 10.12659/aot.900779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon YI, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, et al. Postresection Outcomes of Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Cholangiocarcinoma, Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Feb;20((2)):411–20. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-3045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SD, Park SJ, Han SS, Kim SH, Kim YK, Lee SA, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma after surgery. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014 Dec;13((6)):594–601. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(14)60275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SH, Park YN, Lim JH, Choi GH, Choi JS, Kim KS. Characteristics of combined hepatocelluar-cholangiocarcinoma and comparison with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014 Aug;40((8)):976–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sapisochin G, de Lope CR, Gastaca M, de Urbina JO, López-Andujar R, Palacios F, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing liver transplantation: a Spanish matched cohort multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2014 May;259((5)):944–52. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin X, Zhang BH, Qiu SJ, Ren ZG, Zhou J, Chen XH, et al. Combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: clinical features, treatment modalities, and prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Sep;19((9)):2869–76. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sapisochin G, Fidelman N, Roberts JP, Yao FY. Mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2011 Aug;17((8)):934–42. doi: 10.1002/lt.22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Chung GE, Yu SJ, Hwang SY, Kim JS, Kim HY, et al. Long-term prognosis of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection comparison with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Jan;45((1)):69–75. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181ce5dfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuo HQ, Yan LN, Zeng Y, Yang JY, Luo HZ, Liu JW, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of 15 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007 Apr;6((2)):161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang D, Nagano H, Nakamura M, Wada H, Marubashi S, Miyamoto A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of Allen's type C classification of resected combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a comparative study with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006 Jul-Aug;10((7)):987–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yano Y, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Sakamoto Y, Yamasaki S, Shimada K, et al. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 26 resected cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jun;33((6)):283–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Bosch MA, Defreyne L. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012 Aug;380((9840)):469–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruix J, Boix L, Sala M, Llovet JM. Focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2004 Mar;5((3)):215–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Abdalla EK, Arens JF, Nemr RA, Wei SH, et al. Is extended hepatectomy for hepatobiliary malignancy justified? Ann Surg. 2004 May;239((5)):722–30. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124385.83887.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki A, Kawano K, Aramaki M, Ohno T, Tahara K, Takeuchi Y, et al. Clinicopathologic study of mixed hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma: modes of spreading and choice of surgical treatment by reference to macroscopic type. J Surg Oncol. 2001 Jan;76((1)):37–46. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200101)76:1<37::aid-jso1007>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groeschl RT, Turaga KK, Gamblin TC. Transplantation versus resection for patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2013 May;107((6)):608–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.23289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chantajitr S, Wilasrusmee C, Lertsitichai P, Phromsopha N. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: clinical features and prognostic study in a Thai population. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13((6)):537–42. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KH, Lee SG, Park EH, Hwang S, Ahn CS, Moon DB, et al. Surgical treatments and prognoses of patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Mar;16((3)):623–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garancini M, Goffredo P, Pagni F, Romano F, Roman S, Sosa JA, et al. Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma : A Population-Level Analysis of an Uncommon Primary Liver Tumor. 2014;20:952–959. doi: 10.1002/lt.23897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma KW, Chok KS. Importance of surgical margin in the outcomes of hepatocholangiocarcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2017 May;9((13)):635–41. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i13.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ravaioli M, Grigioni WF, Cescon M, Gardini A, et al. The role of lymphadenectomy for liver tumors: further considerations on the appropriateness of treatment strategy. Ann Surg. 2004 Feb;239((2)):202–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109154.00020.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma KW, Chok KS, She WH, Cheung TT, Chan AC, Dai WC, et al. Hepatocholangiocarcinoma/intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: are they contraindication or indication for liver transplantation? A propensity score-matched analysis. Hepatol Int. 2018 Mar;12((2)):167–73. doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]