Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine antimicrobial resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from clinical samples from patients hospitalized during 2015–2017 in hospitals of Masovian district in Poland.

Materials and Methods

Antimicrobial resistance of 112 MRSA isolates was tested with a disc diffusion method. Isolates were examined for methicillin resistance using a 30 µg cefoxitin disk. Resistance was confirmed by PCR detection of the mecA gene. PCR was also used to determine spa gene polymorphism in X-region.

Results

A large number of MRSA isolates showed resistance to levofloxacin (83.9%), ciprofloxacin (83%), erythromycin (77.7%) and clindamycin (72.3%). A lower number of MRSA isolates showed resistance to tetracycline (10.7%), amikacin (14.2%), gentamicin and trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole (8.0%). None of the MRSA isolates were resistant to linezolid and teicoplanin. Among MRSA isolates, 92.9% were multidrug-resistant (MDR). Resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin was the most common resistance pattern among MDR MRSA isolates. The highest number of isolates was resistant to 4 groups of antimicrobials (53.8%). The number of drugs to which MRSA isolates were resistant in 2017 was significantly higher than that in 2016 (p = 0.002). The size polymorphism analysis of X fragment of the spa gene revealed high genetic diversity of the investigated group MRSA isolates.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that in the hospital environment, MRSA isolates can quickly acquire new antimicrobial resistance determinants and that knowledge of current resistance patterns is important for the effective treatment of infections caused by MDR MRSA.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Spa types

Significance of the Study

In the hospital environment, MRSA isolates can quickly acquire new antimicrobial resistance determinants.

These results are significant for the empirical use of antibiotics and effective treatment of infections caused by MDR MRSA.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of nosocomial infections and is one of the most common causes of bacteremia and is a bacterial pathogen that rapidly acquires antibiotic resistance [1]. Microbial infections with antimicrobial resistant strains increased the risk of mortality and increased costs related to treatment compared to infections caused by susceptible strains [2]. Antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus (MRSA) is associated with the acquisition of a mobile genetic element called the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, which carries the mecA gene, encoding the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 2a and confers resistance to the β-lactam antibiotics [3]. A new mec variant, named mecC, which shows only 70% nucleotide sequence homology with the classical mecA gene was described in 2011 and from this time, MRSA strains containing mecC have been sporadically isolated from both humans and animals. Resistance to cefoxitin was reported as correctly identifying mecC-positive MRSA [4]. MRSA, besides resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, are frequently resistant to other antimicrobial agents such as macrolides, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol and fluoroquinolones may rapidly spread in hospital environment through infected or colonized patients, or colonized personnel [5]. MRSA are widespread in various countries both in hospital environments and occur in community, and livestock MRSA is endemic in hospitals worldwide [6, 7]. Infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains lead to prolonged hospital stay, increased mortality and have been routinely detected in hospitalized patients including those in high-income countries. These infections are estimated to affect >150,000 patients annually in the European Union [8]. MDR may infect different parts of the body including wounds, respiratory tract, soft tissue, skin and bloodstream particularly in immunocompromised, elderly or young patients [9]. The rise of drug-resistant MRSA is a serious problem in the treatment and control of staphylococcal infections. The aim of this study was to determine antimicrobial resistance profiles of MRSA isolates from different clinical materials from patients hospitalized during 2015–2017 in hospitals of Masovian district in Poland.

Materials and Methods

MRSA Isolates

A total of 112 MRSA isolates from clinical materials from swabs from wounds (22), anus (14) and samples of blood (11), bronchoalveolar washings (26), respiratory tract (19), urine (4), pus (3), sputum (3) and from other samples (swabs from nose, throat, tracheotomy tube, endotracheal tube and catheter; 10) were studied. The MRSA isolates were obtained from hospitals in Siedlce and Warsaw (Poland) in 2015–2017. The MRSA isolates were collected in these hospitals as part of routine diagnostic microbiology and came from different patients. The numbers of MRSA isolates obtained in 2015, 2016 and 2017 were 18, 23 and 71, respectively. Identification of isolates as S. aureus was confirmed by Gram's staining, positive test for catalase activity and tube test for coagulase. The PCR analysis to amplify the part of the nuc gene, encoding thermostable nuclease specific for S. aureus was used to confirm that the isolates belong to the S. aureus species [10].

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

All staphylococcal isolates were examined for methicillin resistance by disc diffusion assay. Resistance to methicillin was confirmed by PCR to detect the mecA gene [11]. The susceptibility of the isolates was tested with a disc diffusion method [12] using the following antibiotic discs (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK): penicillin (10 U), teicoplanin (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), amikacin (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg) and linezolid (30 µg). S. aureus ATCC 29213 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were used as control strains.

Isolation of DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from bacterial cells by using the NucleoSpin Microbial DNA (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. 2.5 µL of the total extracted material from each test sample was used as a template DNA for PCR application.

Primers and PCR Conditions

The primers specific for the nuc, mecA, blaZ[13], and spa [14] synthesized by DNA-Gdańsk (Gdańsk, Poland) are listed in Table 1. The monoplex PCR for each gene was performed in a 25 µL volume containing 2.5 µL of DNA template, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), the specific primers at 150 nM, and 1 U of RedTag Genomic DNA polymerase (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). The amplifications of fragments specific for the nuc, blaZ and mecA genes were carried out in the following conditions: initial denaturation (94°C, 4 min), followed by 35 subsequent cycles consisting of denaturation (94°C, 30 s), primer annealing (55°C, 30 s), extension (72°C, 30 s), and final extension (72°C, 5 min). The highly polymorphic region X of the spa gene was amplified by PCR according to Szweda et al. [15].

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in the study

| Primers | Sequence (5′→ 3′) | Amplicon length, bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nuc (F) nuc (R) |

GCGATAGATGGTGATACGGTT AGCCAAGCCTTGACGAACTAAAGC |

270 | [10] |

|

mecA (F) mecA (R) |

AAAATCGATGGTAAAGGTTGGC AGTTCTGCAGTACCGGATTTGC |

533 | [11] |

|

blaZ (F) blaZ (R) |

AAGAGATTTGCCTATGCTTC GCTTGACCACTTTTATCAGC |

517 | [13] |

|

spa (F) spa (R) |

CAAGCACCAAAAGAGGAA CACCAGGTTTAACGACAT |

100–388 | [14] |

Amplifications were carried out in the Eppendorf Mastercycler nexus gradient (Hamburg, Germany). The PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Molecular size markers (Sigma-Aldrich) were also run for verification of product size. The gel was electrophoresed in 2× Tris-borate buffer at 70 V for 1.5 h. The PCR amplicons were visualized using UV light (Syngen Imagine, Syngen Biotech, Wrocław, Poland).

Statistical Analysis

One-factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to evaluate the relationship of the level of MDR with the clinical specimens from which MRSA isolates were obtained. One-factorial ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's test were used to evaluate significance of differences between the number of drugs to which MRSA isolates were resistant in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

Results

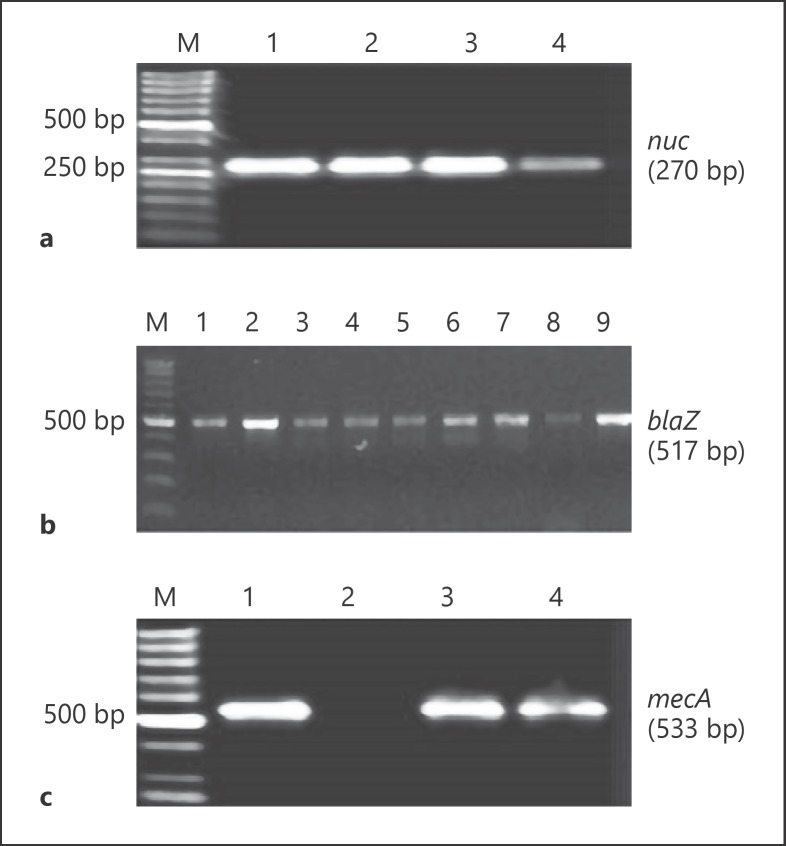

The PCR product specific for the nuc gene, encoding thermostable nuclease in S. aureus was detected in all isolates (Fig. 1a). The isolates were resistant to penicillin and the blaZ gene encoding β-lactamase was present in these isolates (Fig. 1b). All isolates were resistant to cefoxitin, and mecA gene was detected in all isolates (Fig. 1c). A large number of MRSA isolates showed resistance to fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin −83% and levofloxacin −83.9%, macrolides (erythromycin −77.7%) and lincosamides (clindamycin −72.3%. The percentage of MRSA isolates resistant to levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin and erythromycin varied in the years 2015–2017, but the highest percentage of isolates resistant to these antibiotics was found in 2017 (Table 2). A lower number of MRSA isolates showed resistance to tetracycline (10.7%), amikacin (14.2%), gentamicin (8.0%) and trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole (8.0%). None of the MRSA isolates was resistant to linezolid and teicoplanin (Table 2). The MRSA isolates were tested against 9 groups of antimicrobials, and resistance to at least 3 groups indicated that the isolates were MDR. Out of 112 MRSA isolates, 104 (92.9%) were MDR. Besides resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin was the most common resistance pattern among MDR MRSA isolates (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel PCR products obtained by using specific primers for nuc (a), blaZ (b) and mecA gene (c). Line M − molecular weight markers (GenoPlast Biochemicals, Poland), Lines: 1, 2, 3, 4 − products (270 bp) specific for nuc gene (a); 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 − products (517 bp) specific for blaZ gene (b); 1, 3, 4 − products (533 bp) specific for mecA gene (c).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance of MRSA isolated from patients hospitalized in 2015–2017

| Antimicrobial category | Antimicrobial agent | Resistant isolates in years, n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 (n = 18) | 2016 (n = 23) | 2017 (n = 71) | total (n = 112) | ||

| β-Lactams | Penicillin | 18 (100) | 23 (100) | 71 (100) | 112 (100) |

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin | 2 (11.1) | 0 | 14 (19.7) | 16 (14.2) |

| Gentamicin | 3 (16.6) | 0 | 6 (8.4) | 9 (8.0) | |

| Fluoroquinolones | Levofloxacin | 15 (83.3) | 13 (56.5) | 66 (92.9) | 94 (83.9) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 15 (83.3) | 12 (52.2) | 66 (92.9) | 93 (83) | |

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | 8 (44.4) | 16 (69.6) | 57 (80.3) | 81 (72.3) |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | 13 (72.2) | 16 (69.6) | 58 (81.7) | 87 (77.7) |

| Glycopeptides | Teicoplanin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline | 4 (22.2) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (7.0) | 12 (10.7) |

| Oxazolidinones | Linezolid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 1 (5.5) | 0 | 8 (11.3) | 9 (8.0) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 3.

Resistance patterns of MRSA isolates from different clinical specimens

| Resistance patterns | Antibiotic groups to which resistance was seen | Strains to which resistance was seen, n (%) | Specimen |

|---|---|---|---|

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX | 4 | 48 (42.8) | Respiratory tract (9), blood (7), urine (1), anus (7), bronchoalveolar washings (13), wound (7), purulence (1), other (3) |

| P/E/CC | 3 | 9 (8.0) | Blood (2), anus (3), wound (2), purulence (2) |

| P/E/CIP/LVX | 3 | 9 (8.0) | Respiratory tract (4), urine (1), anus (3), wound (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/AN | 5 | 8 (7.1) | Blood (1), sputum (1), bronchoalveolar washings (4), wound (1), other (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/TE | 5 | 4 (3.6) | Respiratory tract (1), sputum (1), bronchoalveolar washings (1), wound (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/GM/SXT | 6 | 2 (1.8) | Respiratory tract (1), bronchoalveolar washings (1) |

| P/E/CIP/LVX/GM | 4 | 2 (1.8) | Respiratory tract (1), other (1). |

| P/CIP/LVX/TE | 3 | 2 (1.8) | Blood (1), wound (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/AN/SXT | 6 | 2 (1.8) | Bronchoalveolar washings (1), wound (1) |

| P/E/CC/TE | 4 | 2 (1.8) | Wound (1), other (1) |

| P/CC/CIP/LVX | 3 | 2 (1.8) | Wound (2) |

| P/CIP/LVX/AN | 3 | 2 (1.8) | Bronchoalveolar washings (2) |

| P/E/CIP/LVX/GM/AN/SXT | 5 | 1 (0.9) | Bronchoalveolar washings (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/GN/SXT/TEC | 7 | 1 (0.9) | Urine (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/GM/AN/SXT | 6 | 1 (0.9) | Anus (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/AN/GM/SXT | 6 | 1 (0.9) | Wound (1) |

| P/CIP/LVX/GM/AN/TE | 4 | 1 (0.9) | Wound (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/LVX/LZD | 5 | 1 (0.9) | Anus (1) |

| P/CIP/LVX/GM/TE | 4 | 1 (0.9) | Wound (1) |

| P/CC/CIP/LVX/TE | 4 | 1 (0.9) | Urine (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP/AN | 5 | 1 (0.9) | Other (1) |

| P/CC/CIP/LVX | 3 | 1 (0.9) | Bronchoalveolar washings (1) |

| P/E/CC/CIP | 4 | 1 (0.9) | Anus (1) |

| P/CC/TE | 3 | 1 (0.9) | Sputum (1) |

| Total of MDR MRSA | 104 (92.9) | ||

P, penicillin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LVX, lewofloxacin; E, erythromycin; CC, clindamycin; AN, amikacin; TE, tetracycline; GM, gentamicin; SXT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; TEC, teicoplanin; LZ, linezolid; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MDR, multidrug-resistant.

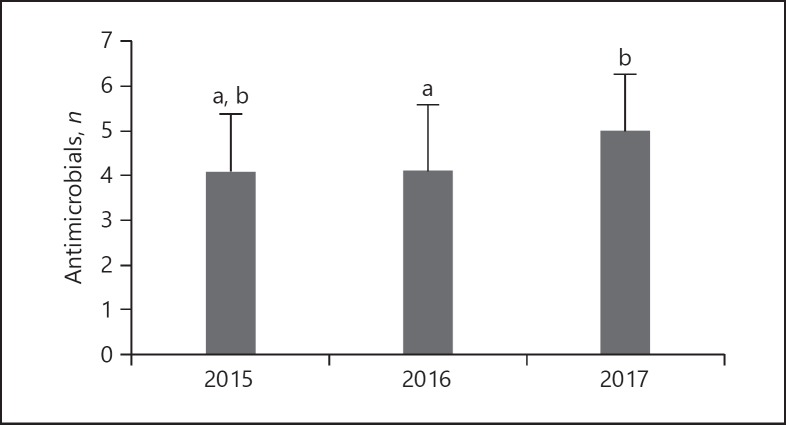

In all, 53.8% of the MDR MRSA isolates were resistant to 4 groups of antimicrobials, and 25% showed resistance to 3 groups of antimicrobials. Most of the isolates resistant to 3 groups of antimicrobials were resistant to β-lactams, macrolides and lincosamides or fluoroquinolones. The resistance to 5 groups of antimicrobials was observed in 14.4% of MDR MRSA isolates from bronchoalveolar washings (6), sputum (2), wound (2), blood (1), respiratory tract (1), anus (1) and from other samples (2). The resistance to β-lactams, macrolides, lincosamides, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides or tetracycline was the most common among them. Six MDR MRSA isolates (5.8%) resistant to 6 group of antimicrobials were isolated from respiratory tract (1), bronchoalveolar washing (2), wound (2) and anus (1). One isolate from urine was resistant to seven groups of antimicrobials (Table 3). One-factorial ANOVA showed that the level of MDR was not significantly associated with the clinical specimens from which MRSA isolates were obtained (p = 0.251). The mean number of drugs to which MRSA isolates were resistant in 2015, 2016 and 2017 was 4.4 ± 1.2, 3.9 ± 1.5 and 5.0 ± 1.3 respectively. Statistical analysis using Tukey's test showed that the level of multi-drug resistance in 2015 and 2016 did not significantly differ, but the isolates from 2017 were resistant to significantly more antimicrobials compared to those obtained in 2016 (p = 0.002; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The level of MDR among MRSA isolated in 2015–2017. The mean number of antimicrobials to which MRSA isolates were resistant was compared irrespective of the specimen type. Different letter (a, b) superscripts indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p = 0.002). The mean number of drugs to which MRSA isolates in 2017 were resistant was significantly higher than that isolated in 2016 (Tukey's test, p = 0.002).

The genotypic diversity of the investigated MRSA isolates was revealed by the size polymorphism analysis of X fragment of the spa gene coding protein A. Amplification of the X-region of spa yielded a single amplicon for each isolate. Eleven differently sized amplicons of approximately 148-388 bp were detected. The number of repeats of the 24 nucleotide sequence in X-region in tested isolates was between 4 and 14. The MRSA isolates with 8, 9, 10 and 11 repeats in the amplified region were detected most frequently (22.3, 10.7, 13.4 and 28.6%; Table 4).

Table 4.

Diversity of the 24 bp repeats in X-region of the spa gene in MRSA isolates from patients hospitalized in 2015–2017

| 24 bp repeats in X-region of spa | Size of the PCR product, bp | Isolates with repeats in region X, n (%) |

Total (n = 112) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 (n = 18) | 2016 (n = 23) | 2017 (n = 71) | |||

| 4 | 148 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| 5 | 172 | 3 (16.7) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (5.3) |

| 6 | 196 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 2 (2.8) | 3 (2.7) |

| 7 | 220 | 1 (5.5) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (8.4) | 9 (8.0) |

| 8 | 244 | 2 (11.1) | 1 (4.3) | 22 (31.0) | 25 (22.3) |

| 9 | 268 | 4 (22.2) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (8.4) | 12 (10.7) |

| 10 | 292 | 1 (5.5) | 4 (17.4) | 10 (14.1) | 15 (13.4) |

| 11 | 316 | 8 (44.4) | 9 (39.1) | 15 (21.1) | 32 (28.6) |

| 12 | 340 | 0 | 9 (39.1) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| 13 | 364 | 0 | 0 | 6 (8.4) | 6 (5.3) |

| 14 | 388 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (1.8) |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Discussion

S. aureus is recognized as one of the most frequent causative agents of hospital-associated and device-associated infections [16]. The hospital environment and the endogenous microflora of patients and health care workers may play important roles as the source, reservoirs and vectors for the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Research on the dynamics of resistance development, identification of high-risk strains and molecular basis of resistance are very important and required. The association of S. aureus with antimicrobial resistance profiles can provide useful information for the clinical treatment of infection caused by this microorganism. MRSA have emerged as a significant threat in both the hospital and community environment. Limited treatment options of infections caused by MRSA result in higher mortality and increased financial costs. Among MDR bacteria, MRSA is a major cause of healthcare-associated infections in the EU. In 2008, MRSA caused in the UE 44% of healthcare-associated infections, 22% of attributable extra deaths and 41% of extra days of hospitalization associated with these infections [17]. In the United States, MRSA causes between 11,000 and 18,000 deaths annually and 80,000 invasive infections [18].

In the current study, we investigated drug resistance of MRSA isolates from different clinical materials from hospitalized patients in Masovian district in Poland. We have undertaken studies evaluating the resistance of MRSA isolates because they represent a high percentage among of S. aureus isolates from clinical materials in many countries. MRSA accounts for about 60% of clinical S. aureus isolates from intensive care units in the United States [19] and the same percentage of hospital S. aureus strains in China and Nepal [20, 21]. The proportion of MRSA among all S. aureus isolates reached 35.8% in Italy [22], above 40% in Philippines [23] and 68.4% in Ethiopia [7]. This is of concern because MRSA limit the choice of antibiotics for treating infections caused by them. The previous study conducted in Poland by Łuczak-Kadłubowska et al. [24] who investigated S. aureus isolates from 39 hospitals showed that the proportion of MRSA isolates depended on the hospital and ranged from 3.7 to 63.1% (average 22.7%). In our study, we investigated the susceptibility of MRSA isolates to 9 groups of antimicrobials, and a very high percentage (92.9%) of isolates was MDR. According to Campanile et al. [22], all MRSA isolates from nosocomial infections isolated in 2012 in Italy were MDR organisms. A high percentage of S. aureus strains (82.3%) from hospitalized patients in Ethiopia were resistant to 3 or more antimicrobials [7]. A high percentage of our MDR isolates were resistant to 4 groups of antimicrobials (53.8%). Some isolates were resistant to 3, 5 or 6 groups of antibiotics, and one isolate was resistant to 7 groups of antibiotics. These results indicate that the possibilities of treating infections caused by MDR MRSA using available antibiotics are very limited. The level of resistance to fluoroquinolones, clindamycin and erythromycin of our MRSA isolates was similar to the resistance level of MRSA isolates in Italy, while percentages of isolates resistant to gentamicin and tetracycline in Italy [22] was slightly higher than in our research. Our study revealed that the percentage of strains resistant to amikacin, gentamicin, tetracycline and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was lower compared to other results [7, 25]. Our study also showed that the level of MDR among of MRSA isolates in Poland increased as the number of drugs to which isolates were resistant in 2017 was significantly higher than in 2016, and also higher (although insignificantly) compared to 2015. The development of resistance to many antibiotics by S. aureus is associated with acquisition of determinants by horizontal gene transfer of mobile genetic elements and can also emerge by mutations that alter the drug-binding sites on molecular targets and by the expression of endogenous efflux pumps [26].

Our study revealed substantial genetic diversity of the analyzed group of MRSA isolates, which rather excludes their origin from the same initial strain and indicates that these isolates have emerged from outside the hospitals. Grundmann et al. [27] showed that spa types MRSA in Europe form distinctive geographical clusters and genetic diversity of MRSA differed considerably among the countries. The number of spa types of MRSA isolates in 26 European countries was 155. The highest number of spa types among MRSA isolates was showed in France (27), Ireland (26) and Belgium (25). In our research, we found 11 spa types, which were similar to number of spa types in Bulgaria (11), Croatia (13), Italy (15) and Portugal (13) [27]. We found that 83% of MRSA isolates had >7 repeats in X-region of spa gene. S. aureus with repeats more than 7 in the X-region are more transmissible and these isolates are involved in epidemic outbreaks, while the presence of 7 or less repeats is indicative of a non-epidemic phenotype [28]. The allele with 11 repeats was the most common (28.6%). Similar results was obtained by Montesinos et al. [29] who investigated MRSA isolates from hospitalized patients and outpatients in Spain. In the present study, isolates with 8, 9 and 10 repeats in the amplified region of spa gene were also frequently detected. Similar results were obtained by other authors [15, 30] who investigated S. aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Poland, which may indicate that these spa types are widespread in Poland.

Conclusion

About 93% of MRSA isolates from different clinical materials from hospitalized patients in Masovian district in Poland were MDR organisms. A high percentage of MRSA isolates showed resistance to fluoroquinolones, macrolides and lincosamides, while a fewer of them showed resistance to tetracycline, aminoglycosides and trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole. Resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin was the most common resistance pattern among MDR MRSA isolates. No MRSA isolates were resistant to linezolid and teicoplanin. It is important to note that these data shows that the isolates from 2017 were resistant to a significantly higher number of antimicrobials compared to those obtained in 2016, which indicates rapid acquisition of new antimicrobial resistance determinants by MRSA isolates in the hospital environment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Siedlce University of Natural Science and Humanities (Scientific Research Project No. 316/12/S).

References

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan;48((1)):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulvey MR, Simor AE. Antimicrobial resistance in hospitals: how concerned should we be? CMAJ. 2009 Feb;180((4)):408–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katayama Y, Ito T, Hiramatsu K. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000 Jun;44((6)):1549–55. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1549-1555.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupieux C, Bouchiat C, Larsen AR, Pichon B, Holmes M, Teale C, et al. Detection of mecC-positive Staphylococcus aureus: what to expect from immunological tests targeting PBP2a? J Clin Microbiol. 2017 Jun;55((6)):1961–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00068-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ness T. [Multiresistant bacteria in ophthalmology] Ophthalmologe. 2010 Apr;107((4)):318–22. doi: 10.1007/s00347-009-2076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kot B, Piechota M, Wolska KM, Frankowska A, Zdunek E, Binek T, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance of staphylococci from bovine milk. Pol J Vet Sci. 2012;15((4)):677–83. doi: 10.2478/v10181-012-0105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tadesse S, Alemayehu H, Tenna A, Tadesse G, Tessema TS, Shibeshi W, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients with infection at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018 May;19((1)):24. doi: 10.1186/s40360-018-0210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köck R, Becker K, Cookson B, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Harbarth S, Kluytmans J, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): burden of disease and control challenges in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2010 Oct;15((41)):19688. doi: 10.2807/ese.15.41.19688-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG., Jr Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Jul;28((3)):603–61. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brakstad OG, Aasbakk K, Maeland JA. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992 Jul;30((7)):1654–60. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1654-1660.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami K, Minamide W, Wada K, Nakamura E, Teraoka H, Watanabe S. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991 Oct;29((10)):2240–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2240-2244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CLSI . CLSI Supplement M100. 26th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2016. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vesterholm-Nielsen M, Olhom Larsen M, Elmerdahl Olsen J, Moller Aarestrup F. Occurrence of the blaZ gene in penicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Denmark. Acta Vet Scand. 1999;40((3)):279–86. doi: 10.1186/BF03547026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frénay HM, Bunschoten AE, Schouls LM, van Leeuwen WJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Verhoef J, et al. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996 Jan;15((1)):60–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01586186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szweda P, Schielmann M, Milewski S, Frankowska A, Jakubczak A. Biofilm production and presence of ica and bap genes in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with mastitis in the eastern Poland. Pol J Microbiol. 2012;61((1)):65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danzmann L, Gastmeier P, Schwab F, Vonberg RP. Health care workers causing large nosocomial outbreaks: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Feb;13((1)):98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/European Medicines Agency (ECDC/EMEA) Joint technical report The bacterial challenge: time to react. Stockholm: ECDC/EMEA; 2009 Available from: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/0909_TER_The_Bacterial_Challenge_Time_to_React.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgenstern M, Erichsen C, Hackl S, Mily J, Militz M, Friederichs J, et al. Antibiotic resistance of commensal Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci in an international cohort of surgeons: a prospective point-prevalence study. PLoS One. 2016 Feb;11((2)):e0148437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noskin GA, Rubin RJ, Schentag JJ, Kluytmans J, Hedblom EC, Smulders M, et al. The burden of Staphylococcus aureus infections on hospitals in the United States: an analysis of the 2000 and 2001 Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Aug;165((15)):1756–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng H, Yuan W, Zeng F, Hu Q, Shang W, Tang D, et al. Molecular and phenotypic evidence for the spread of three major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones associated with two characteristic antimicrobial resistance profiles in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013 Nov;68((11)):2453–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upreti N, Rayamajhee B, Sherchan SP, Choudhari MK, Banjara MR. Prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, multidrug resistant and extended spectrum β-lactamase producing gram negative bacilli causing wound infections at a tertiary care hospital of Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018 Oct;7((1)):121. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campanile F, Bongiorno D, Perez M, Mongelli G, Sessa L, Benvenuto S, et al. AMCLI − S. aureus Survey Participants Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in Italy: first nationwide survey, 2012. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2015 Dec;3((4)):247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juayang AC, de Los Reyes GB, de la Rama AJ, Gallega CT. Antibiotic resistance profiling of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical specimens in a tertiary hospital from 2010 to 2012. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2014;2014:898457. doi: 10.1155/2014/898457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Łuczak-Kadłubowska A, Sulikowska A, Empel J, Piasecka A, Orczykowska M, Kozinska A, et al. Countrywide molecular survey of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in Poland. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Sep;46((9)):2930–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00869-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udo EE, Boswihi SS. Antibiotic resistance trends in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Kuwait hospitals: 2011-2015. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26((5)):485–90. doi: 10.1159/000481944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster TJ. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017 May;41((3)):430–49. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundmann H, Aanensen DM, van den Wijngaard CC, Spratt BG, Harmsen D, Friedrich AW, European Staphylococcal Reference Laboratory Working Group Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 2010 Jan;7((1)):e1000215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frénay HM, Theelen JP, Schouls LM, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Verhoef J, van Leeuwen WJ, et al. Discrimination of epidemic and nonepidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1994 Mar;32((3)):846–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.846-847.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montesinos I, Salido E, Delgado T, Cuervo M, Sierra A. Epidemiologic genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis at a university hospital and comparison with antibiotyping and protein A and coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Jun;40((6)):2119–25. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2119-2125.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuźma K, Malinowski E, Lassa H, Kłossowska A. Analysis of protein A gene polymorphism in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine mastitis. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2005;49:41–4. [Google Scholar]