Abstract

Background and Aims

This study aimed to identify the utility of <sup>18</sup>F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (<sup>18</sup>F-FDG-PET/CT) as a predictor of the response of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) to lenvatinib.

Methods

We evaluated 28 consecutive patients with HCC diagnosed by dynamic CT or magnetic resonance imaging combined with <sup>18</sup>F-FDG-PET/CT. The tumor-to-normal liver standardized uptake value ratio (TLR) of the target tumor was measured before treatment using <sup>18</sup>F-FDG-PET/CT, with a TLR ≥2 classified as a high potential for malignant HCC. The treatment response was evaluated 2 weeks after the initiation of lenvatinib using modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Results

Of the 28 patients, 12 (43%) presented with a TLR ≥2. Evaluation of the treatment response at 2 weeks in these 12 patients revealed that 2 (17%) exhibited a complete response, 8 (67%) a partial response, 2 (17%) stable disease, and none with progressive disease. Therefore, 10 of the 12 patients (83%) experienced an objective response to lenvatinib. On the other hand, 7 of the 16 patients with a TLR <2 (44%) experienced an objective response. Thus, the objective response rate was higher in patients with a TLR ≥2 than in those with a TLR <2. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a TLR ≥2 (odds ratio 10.53; p = 0.028) is a useful predictor of an early objective response at 2 weeks.

Conclusion

Patients with unresectable HCC showed a good early treatment response to lenvatinib. High TLR (≥2) may be a useful predictor of an extremely rapid treatment response.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Lenvatinib, Malignant potential, Poorly differentiated, Positron emission tomography

Introduction

Recently, prior to its approval elsewhere in the world, lenvatinib became available in Japan as a new molecular targeted agent for the first-line treatment of unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT) positivity was reported to be strongly associated with poorly differentiated HCC [2]. 18F-FDG-PET/CT-positive HCC is usually a negative predictor of the response to various treatments (i.e., surgical resection, transarterial chemoembolization [TACE], and sorafenib) [3, 4, 5, 6]. However, the usefulness of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in predicting the response to lenvatinib treatment is not clear. Various tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKIs) are currently available, although their early responses after the initiation of treatment have not been determined, especially in cases of poorly differentiated HCC. Because the progression of poorly differentiated HCC is usually rapid, determining the early treatment response while liver function remains preserved can provide an opportunity to switch to another TKI if the effect of the current TKI is insufficient. The main aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the relationship between the tumor-to-normal liver standardized uptake value ratio (TLR) on 18F-FDG-PET/CT and the early tumor response to lenvatinib (2 weeks after initiation) to verify the utility of 18F-FDG-PET for predicting the response to lenvatinib treatment.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

From April 2018 to June 2019, 80 patients received systemic anticancer treatment using lenvatinib for unresectable HCC at the Department of Hepatology, Toranomon Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) dynamic CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed prior to the initiation of lenvatinib, (2) a tumor showing hyperenhancement in the arterial phase of dynamic CT or MRI, (3) 18F-FDG-PET/CT performed prior to initiation of lenvatinib, (4) triple-phase dynamic CT or MRI performed to evaluate the treatment response 2 weeks after initiation of lenvatinib, (5) Child-Pugh class A liver function at the time of lenvatinib initiation, (6) Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage A–C tumor(s), (7) an unresectable HCC with the patient not wanting to undergo local ablation or chemoembolization therapy for various reasons (i.e., tumor size, number, and location; extrahepatic metastasis; TACE failure/refractoriness [7]; and various complications), (8) no treatment history of lenvatinib, (9) a treatment interval >28 days since previous TKI (sorafenib or regorafenib) therapy, and (10) an observation period of ≥4 weeks. A total of 28 patients met these inclusion criteria.

Diagnosis of HCC

The diagnosis of HCC was based predominantly on imaging analysis using dynamic CT or MRI. When a liver nodule showed hyperattenuation in the arterial phase of the dynamic study and washout in the portal or delayed phase, the nodule was diagnosed as HCC.

Imaging Analysis of HCC Using 18F-FDG-PET/CT

Within the month prior to the initiation of lenvatinib, 18F-FDG-PET/CT was performed using a dedicated whole-body PET scanner (Biograph mCT Flow40, Siemens Healthcare, Germany). Using SYNAPSE VINCENT v4 (Fujifilm Medical Systems, Japan) software for semiquantitative analysis, the volume of interest (VOI) was drawn along the outline of the tumor, and maximum standardized uptake value (SUV-max) and mean SUV (SUV-mean) in each intra- and extrahepatic target tumor were calculated. Of the lesions measured, that with the highest 18F-FDG up take was selected and used to calculate the TLR. Next, to measure normal liver activity, 3 non-overlapping spherical 1-cm3 VOIs were drawn in the liver (2 in the right lobe and 1 in the left) on the axial PET images, avoiding the HCC areas seen on dynamic CT. The TLR was calculated using the following equation: TLR = SUV-max of the tumor/SUV-mean of the normal liver. Based on previous reports [3, 6, 8], we selected a TLR ≥2 to indicate high malignant potential.

Lenvatinib Treatment and Assessment of Adverse Events

Lenvatinib (Eisai, Tokyo, Japan) was given orally (8 mg/day to the patients weighing <60 kg, or 12 mg/day to those weighing ≥60 kg). Treatment was discontinued when any unacceptable or serious adverse events (AEs) or significant clinical tumor progression were observed. According to the guidelines for the administration of lenvatinib, the drug dose should be reduced or the treatment interrupted if a patient develops grade ≥3 AEs or any unacceptable drug-related grade 2 AEs. AEs were assessed using the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 [9]. If a drug-related AE occurred, a dose reduction or temporary interruption was implemented until the AE improved to grade 1 or 2, according to the guidelines provided by the manufacturer.

Treatment Response Evaluation

Treatment response was evaluated according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) [10]. The tumor was examined by dynamic CT or MRI at 2 weeks.

Follow-Up Protocol

Physicians examined the patients every 1–2 weeks after the initiation of lenvatinib, and biochemical laboratory and urine tests were also performed. After initiation of lenvatinib, patients underwent dynamic CT or MRI to evaluate the early treatment response at 2 weeks. After evaluation of the treatment response, dynamic CT or MRI was performed every 2–3 months.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as median (range). Differences in background features between each parameter were analyzed by means of the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Progression-free survival (PFS), post-progression survival (PPS), and overall survival (OS) rates were calculated from the time of lenvatinib administration using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in the PFS according to the TLR value were determined by the log-rank test. Independent factors associated with the treatment response were evaluated by multivariate logistic regression analysis. Potential prognostic factors for an objective response at 2 weeks after initiation of lenvatinib included the following: sex, age, body mass index, etiology of background liver disease, platelet count, prothrombin activity, levels of serum albumin, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, α-fetoprotein (AFP), and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), the tumor diameter, the number of tumors, extrahepatic metastasis, TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT, and initial lenvatinib dose. In the multivariate analysis, the integrated score was excluded to detect true factors.

For the univariate and multivariate analyses, several variables were transformed into categorical data consisting of 2 simple ordinal numbers (i.e., 1 and 2). All factors that were at least marginally associated with the objective response (p< 0.15) in the univariate analysis were then entered into the multivariate analysis. Significant variables were selected by a stepwise forward selection method. Atwo-tailed pvalue <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, v26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical Profiles and Laboratory Data

Table 1 summarizes the clinical profiles and laboratory data of the 28 HCC patients treated with lenvatinib in this study. All patients received an initial dose of lenvatinib according to their body weight. Based on the pretreatment imaging analysis, the median tumor diameter was 25.4 mm. Of the 17 patients with BCLC stage A/B disease, 14 (82%) met the up-to-seven criteria. Eleven of the 28 patients (39%) had BCLC stage C disease, 2 of whom (18%) presented with macrovascular invasion (Vp2 and Vv2) and 10 (91%) with extrahepatic metastasis. The median levels of AFP and DCP were 68.5 µg/L and 58.5 AU/L, respectively. The median pretreatment TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT was 1.6 and 12 of the 28 patients (43%) presented with a TLR ≥2. At the time of data lock (28 July 2019), the median observation period was 8.1 months. Optional data on the relative dose intensity (RDI) of lenvatinib were expressed as median (range) as follows: 80% (40–100%) at 2 weeks, 70% (32–100%) at 4 weeks, 60% (30–100%) at 8 weeks, and 55% (30–100%) at 12 weeks.

Table 1.

Clinical profiles and laboratory data of patients with HCC treated with lenvatinib

| Patient characteristics and laboratory data | |

| Total number of patients | 28 |

| Male:female, n | 19:9 |

| Age, years | 75 (53–87) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21.9 (11.9–30.1) |

| HCV:HBV:no HBV/HCV, n | 13:3:12 |

| Platelet count, ×103/µL | 128 (52–305) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.8 (3.2–4.5) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.3–1.5) |

| Prothrombin activity, | 89.1 (64.9–124.8) |

| AST, IU/L | 32 (15–125) |

| AFP, μg/L | 68.5 (0.8–17,264.3) |

| DCP, AU/L | 58.5 (13–41,109) |

| Child-Pugh score 5:6 | 18 (64):10 (36) |

| Initial lenvatinib dose, 8 mg:12 mg | 15 (54):13 (46) |

| Initial lenvatinib dose, mg/kg | 0.17 (0.14–0.23) |

| A history of other TKI treatment | 3 (11) |

| Tumor characteristics | |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 25.4 (10.7–65.0) |

| Number of tumors | 3 (1–200) |

| Macrovascular invasion | 2 (7) |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 10 (36) |

| BCLC stage A:B:C | 5 (18):12 (43):11 (39) |

| TACE failure or refractoriness | 21 (75) |

| Pretreatment TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT | 1.6 (1.2–9.4) |

Values are expressed as median (range) or n (%), unless otherwise indicated. AFP, α-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DCP, des-γ-carboxyprothrombin; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TLR, tumor-to-normal liver ratio.

Evaluation of the Treatment Response to Lenvatinib at Two Weeks

According to the treatment response evaluation using mRECIST conducted at 2 weeks, 4 of 28 patients (14%) exhibited a complete response (CR), 13 (46%) a partial response (PR), and 11 (39%) had stable disease (SD). No patient had progressive disease (PD). Therefore, 17 of 28 patients (61%) experienced a rapid objective response at 2 weeks.

Relationship between an Early Treatment Response at Two Weeks and the TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT

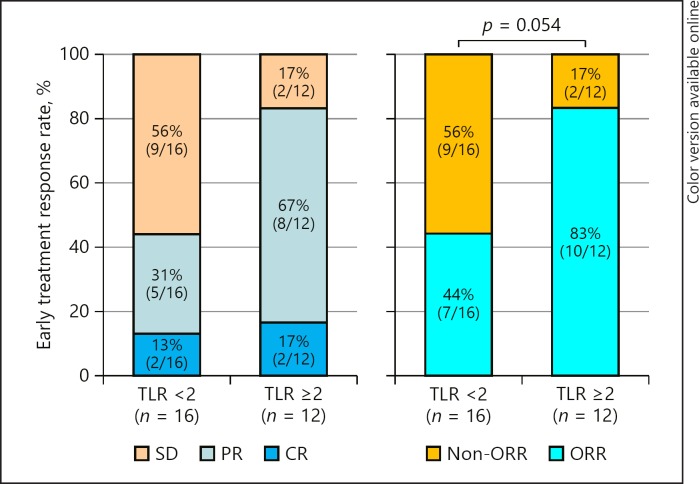

In this study, a cut-off TLR of 2 was used to define HCC with a high malignant potential. Of the 12 patients with a TLR ≥2, 2 (17%) had a CR, 8 (67%) a PR, and 2 (17%) an SD. No patient had a PD. Finally, 10 patients (83%) achieved an objective response early after treatment initiation (2 weeks). In contrast, of the 16 patients with a TLR <2, 2 (13%) had a CR, 5 (31%) a PR, and 9 (56%) an SD, with no patient having a PD. Finally, 7 (44%) with a TLR <2 achieved an objective response. The objective response rate tended to be higher in patients with a TLR ≥2 (p = 0.054) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between the early treatment response to lenvatinib at 2 weeks and the tumor-to-normal liver standardized uptake value ratio (TLR) measured by 18F-FDG-PET/CT. CR, complete response; ORR, objective response rate; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease. The composition ratio is rounded off to the first decimal place and therefore the total will not necessarily be 100.

Predictors of an Objective Response Two Weeks after Lenvatinib Initiation among Baseline Clinical Variables

Of the multiple baseline clinical variables evaluated in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, only 1 independent predictor of an early objective response 2 weeks after lenvatinib initiation was identified: a TLR ≥2 (odds ratio [OR] 10.53; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30–85.65; p = 0.028) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of an early treatment response to lenvatinib

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Gender | 0.232 | |||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.37 (0.07–1.89) | |||

| Age, | 0.102 | |||

| <70 years | 1 | |||

| ≥70 years | 3.9 (0.76–20.0) | |||

| Body mass index | 0.699 | |||

| <22 kg/m2 | 1 | |||

| ≥22 kg/m2 | 1.35 (0.30–6.18) | |||

| Others: HCV | 0.110 | |||

| Others | 1 | |||

| HCV | 3.81 (0.74–19.66) | |||

| Platelet count | 0.823 | |||

| <100 ×103/µL | 1 | |||

| ≥100 ×103/µL | 1.22 (0.22–6.92) | |||

| Albumin | 0.737 | |||

| <3.5 g/dL | 1 | |||

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 0.72 (0.11–4.82) | |||

| Total bilirubin | 0.393 | |||

| <1.0 mg/dL | 1 | |||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 1.97 (0.42–9.32) | |||

| Prothrombin activity | 0.327 | |||

| <80 | 1 | |||

| ≥80 | 3.56 (0.28–4.88) | |||

| AST | 0.658 | |||

| <40 IU/L | 1 | |||

| ≥40 IU/L | 1.45 (0.28–7.64) | |||

| AFP | 0.934 | |||

| <100 μg/L | 1 | |||

| ≥100 μg/L | 1.07 (0.23–4.89) | |||

| DCP | 0.506 | |||

| <300 AU/L | 1 | |||

| ≥300 AU/L | 1.88 (0.29–11.97) | |||

| Tumor diameter | 0.823 | |||

| <30 mm | 1 | |||

| ≥30 mm | 0.84 (0.18–3.88) | |||

| Number of tumors | 0.110 | |||

| <4 | 1 | |||

| ≥4 | 3.81 (0.74–19.66) | |||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 0.132 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 4.00 (0.66–24.30) | |||

| TLR | 0.044 | 0.028 | ||

| <2.0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥2.0 | 6.43 (1.05–39.32) | 10.53 (1.30–85.6) | ||

| TACE failure/refractoriness | 0.506 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.53 (0.08–3.40) | |||

| Initial lenvatinib dose | 0.393 | |||

| <0.16 mg/kg | 1 | |||

| ≥0.16 mg/kg | 0.51 (0.11–2.40) | |||

AFP, α-fetoprotein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; DCP, des-γ-carboxyprothrombin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; OR, odds ratio; TLR, tumor-to-normal liver ratio.

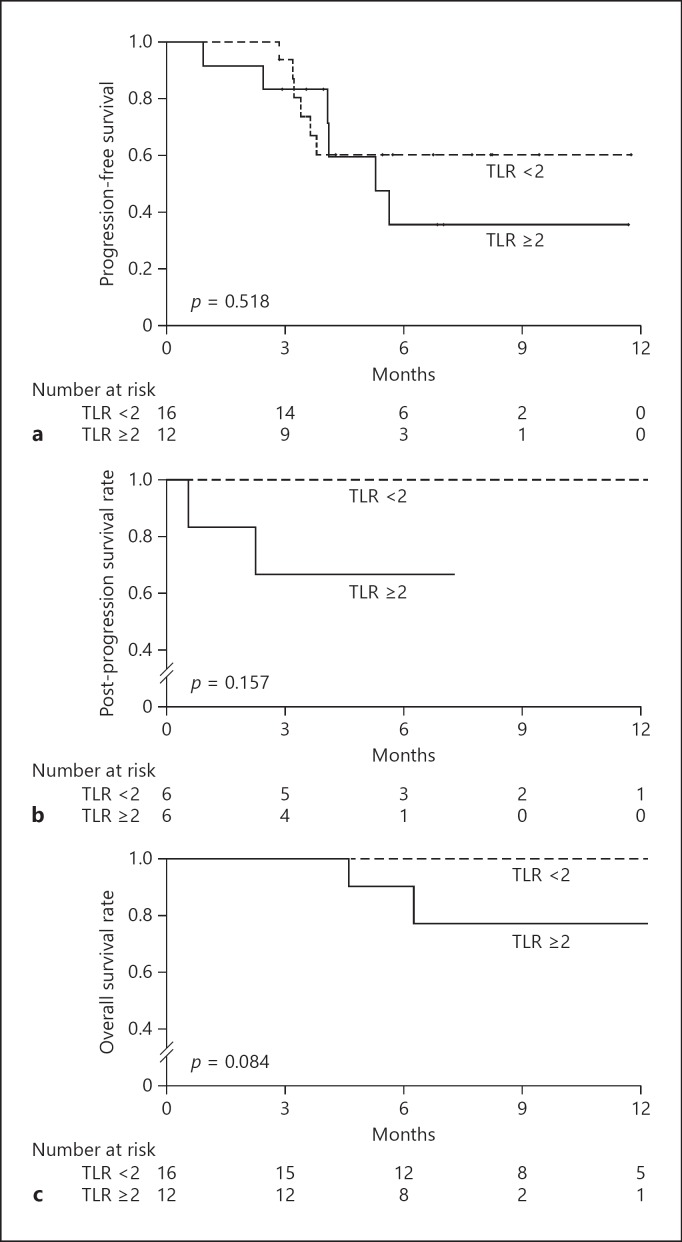

PFS Rate according to the TLR

The cumulative PFS rate after initiation of lenvatinib was 93.8% after 3 months, 60.3% after 6 months, and 60.3% after 9 months in patients with a TLR <2 versus 83.3%, 35.7%, and 35.7%, respectively, in patients with a TLR ≥2. The cumulative PFS rates were not significantly different according to the TLR (p = 0.518) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Progression-free survival rate after the initiation of lenvatinib, according to the tumor-to-normal liver standardized uptake value ratio (TLR) on 18F-FDG-PET/CT. b Post-progression survival rate with lenvatinib treatment, according to the TLR measured by 18F-FDG-PET/CT. c Overall survival rate after initiation of lenvatinib, according to the TLR measured by 18F-FDG-PET/CT.

PPS Rate according to the TLR

In patients with a TLR <2, the cumulative PPS rate after diagnosis of a PD was 100% after 3 and 6 months compared with 66.7% at both these times in patients with a TLR ≥2. These cumulative PFS rates according to the TLR were not significantly different (p = 0.157) (Fig. 2b). Seven patients were diagnosed with a PD state within the observation period, with 6 (86%) continuing to receive lenvatinib treatment.

OS Rate according to the TLR

Only 2 patients in the PET-positive (TLR ≥2) group died during the observation period. The cumulative OS rate after initiation of lenvatinib remained at 100% after 3, 6, and 9 months in patients with a TLR <2, compared with 100%, 90%, and 77.1%, respectively, in patients with a TLR ≥2. The cumulative OS rates tended to be higher in patients with a TLR <2 than in those with a TLR ≥2 (p = 0.084) (Fig. 2c).

Discussion

18F-FDG-PET/CT is considered a useful method for predicting the degree of histological differentiation on imaging analysis. 18F-FDG-PET/CT positivity has been reported to be strongly associated with poorly differentiated HCC [2] and is therefore often a negative predictor of the response to various treatments [3, 4, 5, 6]. However, the usefulness of 18F-FDG-PET/CT for predicting the response to lenvatinib treatment is not clear. As mentioned above, because 18F-FDG-PET/CT-positive HCC is highly associated with histologically poor differentiation, it is desirable to determine the effect of treatment at an early time point. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the relationship between the TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT and the early tumor response 2 weeks after lenvatinib initiation to determine the utility of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in predicting the response to lenvatinib treatment.

The results of our multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that a TLR ≥2 was predictive of an early objective response at 2 weeks (OR 10.53; p = 0.028) and associated with an acceptable PFS and OS rate compared with a TLR <2 (Fig. 2a, c).

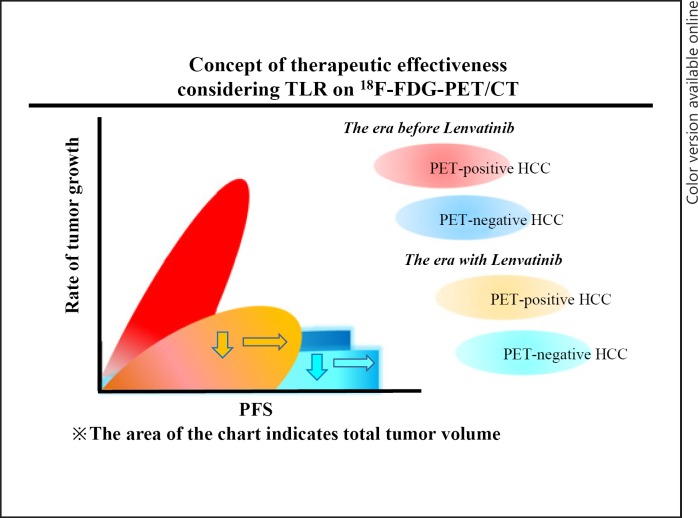

Figure 3 illustrates our concept of the therapeutic effectiveness of considering TLR on 18F-FDG-PET/CT.

Fig. 3.

Concept of therapeutic effectiveness by consideration of the tumor-to-normal liver standardized uptake value ratio (TLR). Regardless of the TLR value, the rate of tumor growth decreased (downward arrows) and progression-free survival (PFS) was extended (rightward arrows). However, a high malignant potential hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), i.e., with a TRL ≥2, was associated with poor post-progression survival. We therefore predict that the prognosis of patients with a PET-positive HCC will not exceed that of patients with a PET-negative HCC.

In this study, HCC nodules with a TLR ≥2 showed a significant early tumor response, although there was no significant difference in PFS according to the TLR value. On the other hand, the PPS was relatively poor in the TLR ≥2 group. We speculated that even if the HCC has a high malignant potential (TLR ≥2), if an objective response is achieved, this does not affect PFS. However, PPS and OS tended to be higher in patients with a TLR <2 than in those with a TLR ≥2. These results indicate that lenvatinib decreases the rate of tumor growth and extends PFS, regardless of the TLR value. However, from many previous reports and our study results, the estimated PPS and OS of PET-positive HCC is poor. We therefore predict that the prognosis of a patient with a PET-positive HCC will not exceed that of a patient with a PET-negative HCC.

Several years ago, Harimoto et al. [11]reported that increased FGFR2 expression correlated significantly with poor histological differentiation, a higher incidence of portal vein invasion, and a high AFP level. As previously mentioned, there is evidence that 18F-FDG-PET/CT-positive HCC is associated strongly with poor histological differentiation. Therefore, potential FGFR inhibition by lenvatinib may have influenced our results. Alternatively, these results may have been influenced by the small sample size, making it necessary to verify the results in a future multicenter study on a greater number of patients.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective, single-center, cohort study on a small number of patients. Second, the diagnosis of HCC was based exclusively on imaging analysis. Third, the follow-up period of the trial was short compared with that of the global Phase III REFLECT trial [12] (i.e., a median follow-up period of 8.1 and 27.7 months, respectively). It was therefore not possible to carry out a high-quality prognostic analysis. Fourth, although FDG-PET/CT analysis is an optional imaging tool, for various reasons it is not as easy to perform as other types of imaging such as CT or MRI, e.g., the relatively high cost and the small number and uneven distribution of the required instruments. A large-scale, multicenter study is necessary to evaluate the utility of 18F-FDG-PET in predicting the response of HCC to lenvatinib.

In conclusion, lenvatinib resulted in a good early treatment response in unresectable HCC. In addition, a high TLR (≥ 2) may be a useful predictor of a rapid treatment response.

Statement of Ethics

This retrospective, noninterventional study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Toranomon Hospital (protocol No. 1438-H/B). It was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

Yusuke Kawamura, Masahiro Kobayashi, Junichi Shindoh, and Hiromitsu Kumada report honoraria from Eisai. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

Funding was provided by the Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development.

Author Contributions

Yusuke Kawamura was responsible for the study concept and design, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript; Masahiro Kobayashi for the acquisition of data and statistical analysis; Junichi Shindoh for the acquisition of data and critical revision; and Kenji Ikeda for the acquisition of data, statistical analysis, and study supervision. All other authors were involved in the acquisition of data.

References

- 1.Ikeda K, Kudo M, Kawazoe S, Osaki Y, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, et al. Phase 2 study of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;52((4)):512–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, Hara T, Tada M, Tamaki N, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Jan;13((2 Pt 1)):427–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, Seo S, Nakamoto Y, Yamanaka K, et al. Preoperative FDG-PET predicts recurrence patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Jan;19((1)):156–62. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1990-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song MJ, Bae SH, Lee SW, Song DS, Kim HY, Yoo IR, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT predicts tumour progression after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013 Jun;40((6)):865–73. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung PS, Park HL, Yang K, Hwang S, Song MJ, Jang JW, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma as a prognostic predictor in patients with sorafenib treatment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018 Mar;45((3)):384–91. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatano E, Ikai I, Higashi T, Teramukai S, Torizuka T, Saga T, et al. Preoperative positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose is predictive of prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J Surg. 2006 Sep;30((9)):1736–41. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Okusaka T, Miyayama S, et al. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan Transarterial chemoembolization failure/refractoriness: JSH-LCSGJ criteria 2014 update. Oncology. 2014;87(Suppl 1):22–31. doi: 10.1159/000368142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyun SH, Eo JS, Lee JW, Choi JY, Lee KH, Na SJ, et al. Prognostic value of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0 and A hepatocellular carcinomas: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016 Aug;43((9)):1638–45. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3348-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Treated and Diagnosis Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Adverse events/CTCAE. Available at: https: //ctepcancergov/ protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctchtm#-ctc_40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Feb;30((1)):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harimoto N, Taguchi K, Shirabe K, Adachi E, Sakaguchi Y, Toh Y, et al. The significance of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 expression in differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2010;78((5-6)):361–8. doi: 10.1159/000320463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Mar;391((10126)):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]