Abstract

Background/Aim

Post-progression treatment following tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI) failure in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (u-HCC) is important to prolong post-progression survival (PPS), which has a good correlation with overall survival (OS). This study aimed to elucidate the clinical features of progressive disease (PD) in patients treated with lenvatinib (LEN).

Materials/Methods

From March 2018 to June 2019, 156 u-HCC patients with Child-Pugh A were enrolled (median age: 71 years, Child-Pugh score 5:6 = 105:51, BCLC A:B:C = 8:56:92, modified albumin-bilirubin grade (mALBI) 1:2a:2b = 59:42:55, past history of sorafenib:regorafenib = 57:17). Clinical features were retrospectively evaluated.

Results

The median observation period was 8.5 months. Median OS was not obtained, while median time to decline to Child-Pugh B (CPB) was 11.4 months, median time to progression (TTP) was 8.4 months, and the period of LEN administration was 7.3 months. When we compared predictive values for time to decline to CPB based on Child-Pugh score and mALBI, values for Akaike information criterion (AIC) score and c-index of mALBI were superior as compared to Child-Pugh score (AIC: 592.3 vs. 599.7) (c-index: 0.655 vs. 0.597). Of the 73 patients with PD, 32 (43.8%) showed no decline to CPB or death. After excluding 3 without alpha-fetoprotein data at PD determination, only 14 (20.0%) of 70 showed REACH-2 eligibility. Non-mALBI 1/2a at the start of LEN was a significant risk factor for decline to CPB during LEN treatment (HR 2.552, 95% CI: 1.577–4.129; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Introduction of TKI therapy including LEN for u-HCC patients with better hepatic function (mALBI 1/2a: ALBI score ≤–2.27), when possible, increases the chance of undergoing post-progression treatment, which can improve PPS.

Keywords: Lenvatinib, Child-Pugh class, Modified albumin-bilirubin grade, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Ramucirumab

Introduction

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) administration has become an important therapeutic option for improving the prognosis of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (u-HCC). Sorafenib (SOR) was the first TKI developed for u-HCC treatment [1, 2], after which regorafenib (REG) became available as a second-line option in 2017 [3]. Nevertheless, there remains an unmet need because of lack of a next therapeutic option for patients beyond RESORCE criteria or with REG failure. In March 2018, lenvatinib (LEN) was made available in Japan as a new first-line TKI treatment drug [4]. Since its development, LEN has been recognized as an effective TKI that can be used for second- and third-line as well as first-line treatment [5, 6]. Indeed, TKI sequential treatment including LEN has been reported to show favorable effectiveness for prolonging prognosis [7]. Additionally, ramucirumab (RAM) has recently been developed as a second-line treatment option for u-HCC patients with an elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level (≥400 ng/mL) who show SOR failure [8].

Treatment to prolong post-progression survival (PPS) has been reported to be the most important factor for prolonging overall survival (OS) [9]. As for obtaining better prognosis of u-HCC patients treated with LEN, the recent increase in therapeutic options has increased the importance of post-progression treatment to prolong PPS and improve OS. However, no report has indicated the percentage of progressive disease (PD) patients who have obtained a favorable condition including hepatic function following LEN treatment. We aimed to elucidate the clinical features of u-HCC patients during LEN treatment including hepatic reserve function in order to determine candidates for post-progression treatment with another molecular targeting agent (MTA) including TKI drugs and RAM.

Materials and Methods

From March 2018 to June 2019, 256 u-HCC patients were treated with LEN (Lenvima®; Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 14 different institutions in Japan. Following exclusion of those given a reduced starting dose, with a Child-Pugh class of B (CPB) or greater, and/or with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 2 or greater, 156 patients were finally enrolled. We retrospectively examined the clinical records of the enrolled cohort at the start of LEN therapy and evaluated clinical data obtained at the time of PD determination or decline to CPB. Patients positive for anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) were judged to have HCC due to HCV, while those positive for hepatitis B virus surface antigen were judged to have HCC due to hepatitis B virus.

Assessments of Hepatic Reserve Function, Therapeutic Response, and Prognosis

The Child-Pugh classification [10] and albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade were used to assess hepatic reserve function. ALBI grade was calculated based on serum albumin and total-bilirubin values using the following formula: ALBI score = (0.66 × log10 bilirubin [µmol/L]) + (–0.085 × albumin [g/L]), with the result defined by the following scores: ≤–2.60 = Grade 1, >–2.60 to ≤–1.39 = Grade 2, and >–1.39 = Grade 3 [11, 12, 13]. For more detailed evaluations of patients with the middle grade of ALBI (grade 2), we used modified ALBI (mALBI) grading consisting of 4 levels, which included subgrading for the middle grade of 2 (2a and 2b) based on an ALBI score of −2.27 as the cut-off, which was previously reported as the value for indocyanine green retention after 15 min (ICG-R15) of 30% [14, 15].

Local physicians at each institution evaluated tumors in the present patients using dynamic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedures performed 4, 8, and 12 weeks and then every 12 weeks thereafter from the introduction of LEN, as possible, in accordance with the modified RESPONSE Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) guideline [16, 17].

Diagnosis of HCC

HCC was diagnosed based on an increasing course of AFP, as well as dynamic CT [18], MRI [19, 20], contrast enhanced ultrasonography with perflubutane (Sonazoid®, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [21, 22], and/or pathological findings. Tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, determined as previously reported in a study for staging of HCC conducted by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (LCSGJ) 6th edition [23] (TNM-LCSGJ), was used for evaluation of tumor progression.

LEN Treatment, Assessment of Adverse Events, and Definition of Eligibility for Post-Progression Treatment following LEN

After obtaining written informed consent, LEN was orally administered at 8 mg/day to patients weighing <60 kg and at 12 mg/day to those ≥60 kg and discontinued with development of any unacceptable or serious adverse event (AE), or when clinical tumor progression was observed. According to the guidelines for administration of LEN, the drug dose was reduced or treatment interrupted when a patient developed a grade 3 or more severe AE, or if any unacceptable grade 2 drug-related AE occurred. Furthermore, according to the guidelines provided by the manufacturer, if a drug-related AE occurred, dose reduction or temporary interruption was maintained until the symptom was resolved to grade 1 or 2. Non-eligibility for post-progression TKI treatment following LEN at the time of judgment of PD in the present analysis was defined as CPB or greater and ECOG PS 2 or more.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Fisher's exact test, the Kaplan-Meier method, a log-rank test, and Cox hazard analysis with a backward stepwise regression model. Akaike information criterion (AIC) and c-index values were used for evaluating prognostic predictive values for each hepatic function. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Easy R (EZR), version 1.29 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) [24], a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient Clinical Features

The clinical features of the 156 enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. Median age was 71 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 64–77 years). Child-Pugh score 5 was noted in 105 (67.3%), while mALBI 1 was noted in 59, 2a in 42, and 2b in 55. A past history of SOR was seen in 36.5% (n = 57), while that of REG was seen in 10.9% (n = 17). As for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage (BCLC), it was A in 8, B in 56, and C in 92, while TNM-LCSGJ I was noted in 1, II in 16, III in 57, IVa in 17, and IVb in 65. An elevated level of AFP (≥400 ng/mL) was observed in 46 (29.5%) of the enrolled patients.

Table 1.

Clinical background of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients classified as Child-Pugh A (n = 156)

| Age, years | 71 (64–77)a |

| Gender, male:female | 113:43 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 (20.6–24.1)a |

| ECOG PS 0:1 | 136:20 |

| Etiology, HCV:HBV:alcohol:others | 67:31:22:36 |

| Platelets, ×104/µL | 13.6 (10.7–16.8)a |

| AST, IU/L | 43 (28–63)a |

| ALT, IU/L | 32 (19–49)a |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.6 (0.2–0.7)a |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.7 (3.4–4.0)a |

| Prothrombin time, | 88.8 (80.0–97.0)a |

| Child-Pugh score, 5:6 | 105:51 |

| Modified ALBI grade, 1:2a:2b | 59:42:55 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 52 (6.7–790.9)a |

| AFP ≥400 ng/mL, n (%) | 46 (29.5) |

| Past history of sorafenib, n (%) | 57 (36.5) |

| Past history of regorafenib, n (%) | 17 (10.9) |

| Vessel invasion, | |

| Vp1:Vp2:Vp3:Vp4:Vv1:Vv2:Vv3 | 6:11:8:2:1:4:4 |

| BCLC stage A:B:C | 8:56:92 |

| TNM-LCSGJ stage, I:II:III:IVa:IVb | 1:16:57:17:65 |

| Starting dose of lenvatinib, 8:12 mg | 68:88 |

| Observation period, months | 8.5 (5.9–11.2)a |

BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; modified ALBI grade, modified albumin-bilirubin grade; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; TNM LCSGJ 6th, tumor node metastasis stage by Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan 6th edition; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage.

Median value (interquartile range).

OS, Period of LEN Administration, and Time to Progression

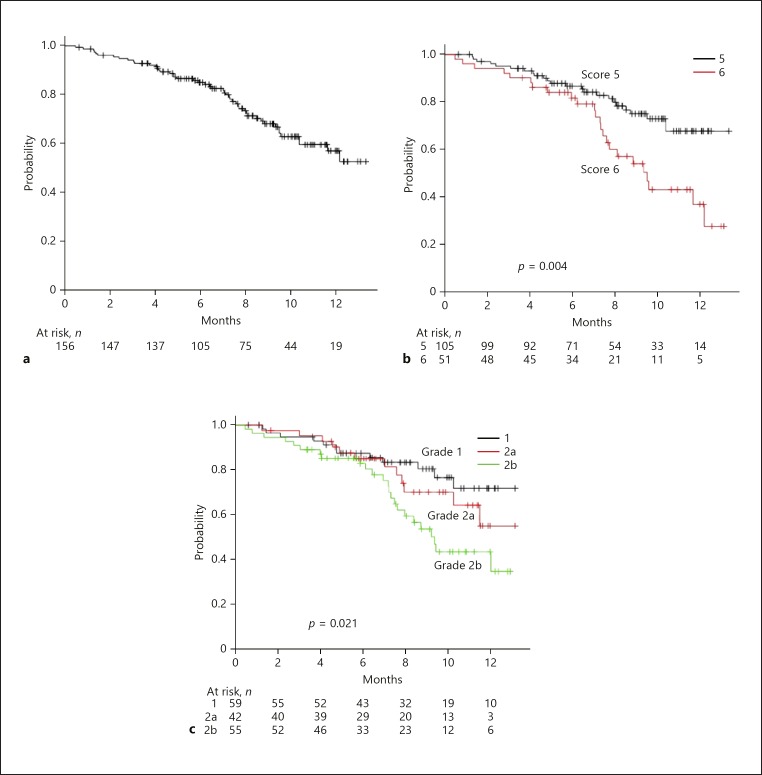

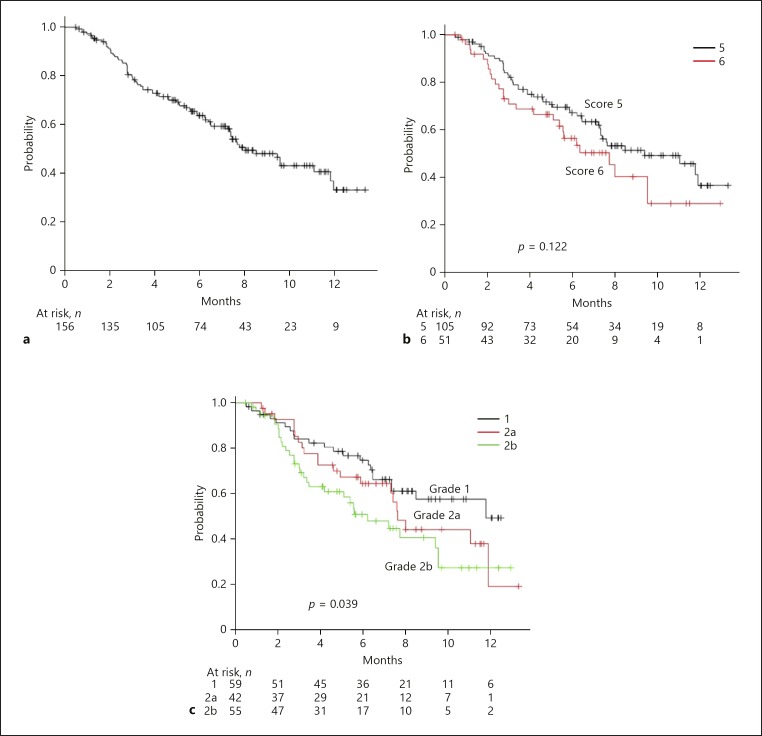

In the present study, median OS was not reached during the period of observation (8.5 months) (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, OS was predicted using both Child-Pugh score and mALBI (Fig. 1b, c). Although AIC scores were similar between them (426.9 vs. 427.1), the c-index of mALBI was better than that of Child-Pugh score (0.591 vs. 0.580). The median period of LEN administration was 7.3 months (online suppl. Fig. 1a; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000503031). In the assessment of period of administration of LEN, the AIC score and c-index of mALBI were better than those of Child-Pugh score (AIC: 824.6 vs. 826.2) (c-index: 0.565 vs. 0.535) (online suppl. Fig. 1b, c). Median time to progression (TTP) was 8.4 months (Fig. 2a). When we compared the predictive values of TTP for Child-Pugh score and mALBI, the AIC score and c-index of mALBI were better than those of Child-Pugh score (AIC: 648.0 vs. 650.9) (c-index: 0.580 vs. 0.554) (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 1.

a Overall survival (OS) of all 156 patients. Median survival time (MST): not reached (NR) during the present observation period. b OS according to Child-Pugh score. OS was better in patients with a Child-Pugh score of 5 than in those with a score of 6 (MST: NR vs. 10.1 months, p = 0.004). c OS according to modified albumin-bilirubin grade (mALBI). Median OS in patients with mALBI 1, 2a, and 2b was NR, NR, and 10.1 months, respectively (p = 0.021).

Fig. 2.

a Time to progression (TTP) of all 156 patients (median: 8.4 months). b TTP according to Child-Pugh score. There was no significant difference in TTP between Child-Pugh score 5 and 6 (median TTP: 9.3 vs. 6.9 months, p = 0.122). c TTP according to modified albumin-bilirubin grade (mALBI). Median TTP in patients with mALBI 1, 2a, and 2b was 9.3, 8.3, and 6.1 months, respectively (p = 0.039).

Period of Decline to CPB

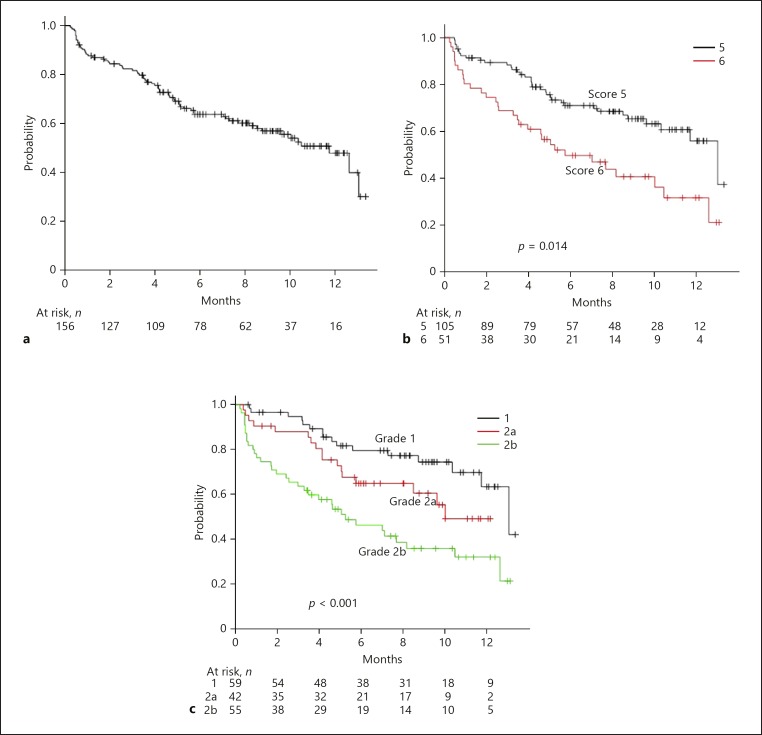

The median period of time to decline to CPB for all patients was 11.4 months (Fig. 3a). When we compared the predictive values for time to decline to CPB using Child-Pugh score and mALBI, AIC and c-index values for mALBI were better as compared to Child-Pugh score (AIC: 592.3 vs. 599.7) (c-index: 0.655 vs. 0.597) (Fig. 3b, c). Only hepatic reserve function (non-mALBI 1/2a) at the time of LEN introduction was a significant risk factor for decline to CPB, as shown by Cox hazard analysis with a backward stepwise regression method (Table 2). There were 12 patients who abandoned LEN due to AEs before first assessment of therapeutic response of LEN at 4 weeks, and 10 of them showed deterioration to CPB at discontinuation of LEN.

Fig. 3.

a Period of decline to Child-Pugh B (CPB) or greater in all 156 patients (median: 11.4 months). b Period of decline to CPB or greater according to Child-Pugh score. There was a significant difference between Child-Pugh score 5 and 6 (median: 12.8 vs. 5.7 months, p = 0.014). c Period of decline to CPB or greater according to modified albumin-bilirubin grade (mALBI). Median period for decline to CPB or greater in patients with mALBI 1, 2a, and 2b was 12.8, 10.4, and 5.5 months, respectively (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Cox hazard analysis (with backward stepwise regression method) for risk of decline to Child-Pugh B

| HR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | |||

| Elderly (≥75 years old) | 1.088 | 0.615–1.924 | 0.772 |

| Female gender | 0.728 | 0.409–1.296 | 0.281 |

| BMI ≥22.0 kg/m2 | 0.808 | 0.470–1.389 | 0.441 |

| Etiology (viral hepatitis) | 0.721 | 0.395–1.317 | 0.287 |

| Positive for intake of BCAA | 0.856 | 0.455–1.616 | 0.634 |

| Platelets (×104/µL; 10 or more) | 1.571 | 0.868–2.845 | 0.136 |

| Child–Pugh score 6 | 1.395 | 0.661–2.944 | 0.383 |

| Non-mALBI 1/2a | 2.059 | 0.987–4.293 | 0.054 |

| Past history of sorafenib | 0.823 | 0.438–1.543 | 0.543 |

| Past history of regorafenib | 2.071 | 0.887–4.837 | 0.092 |

| AFP ≥400 ng/mL | 1.892 | 1.079–3.318 | 0.026 |

| Tumor occupancy rate (liver; 50% or more) | 1.510 | 0.760–3.001 | 0.239 |

| Positive for vessel tumor invasion | 1.153 | 0.581–2.291 | 0.685 |

| TNM-LCSGJ stage IV | 1.093 | 0.584–2.045 | 0.781 |

| Result of backward stepwise regression method | |||

| Non-mALBI 1/2a | 2.552 | 1.577–4.129 | <0.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; BCAA, branched chain amino acid; mALBI, modified albumin-bilirubin grade; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; TNM LCSGJ 6th, tumor node metastasis stage by Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan 6th edition.

Eligibility for Post-Progression Treatment after LEN at Time of PD Determination

Seventy-three patients were determined to have PD during the present study period. After exclusion of 3 without AFP data at the time of PD determination, 23 (32.9%) showed a high level of AFP (≥400 ng/mL). Of all 73 patients with PD, 32 (43.8%) were considered eligible for post-progression treatment from the view of maintaining Child-Pugh A and ECOG PS 0/1. After exclusion of 1 without AFP data at the time of PD determination, 14 showed AFP elevation (≥400 ng/mL) of them (45.2% [14/31]). The percentage of patients with mALBI 1/2a who showed eligibility for post-progression treatment was significantly greater as compared to those with mALBI 2b (58.1% [25/43] vs. 23.3% [7/30], p = 0.037). As a result, the percentage of those with PD who met the criteria for the REACH-2 trial was only 20.0% (n = 14) among patients with both PD and AFP data (n = 70). Although there was no statistical significance, the percentage of patients who met the criteria for the REACH-2 trial at PD was larger in the patients with mALBI 1/2a than those with mALBI 2b after excluding 1 patient without AFP data at the time of PD determination (52.0% [13/25] vs. 16.7% [1/6]) (p = 0.185).

Discussion

A previous study noted that even among patients with the best possible Child-Pugh score (5 points), the prognosis of those with ALBI 1 (same as mALBI 1) who were treated with SOR was superior to that of those with ALBI 2 [25]. Therefore, it is considered that a detailed assessment of hepatic function is necessary for clinical practice. However, the middle grade of ALBI (grade 2) covers a wide range and its prognostic value is weak, resulting in underestimation of hepatic function in some patients [26]. Previously, we proposed modification of the ALBI grade by dividing grade 2 into two subgrades based on a cutoff of ALBI score −2.27 for predicting ICG-R15 30% [15].

When considering TKI sequential treatment for u-HCC, hepatic reserve function evaluated using ALBI score has been reported to be the most important factor [7, 27]. Because deterioration of ALBI score was observed at 4 weeks after introducing LEN in each mALBI grade (mALBI 1: −2.82 to −2.53, mALBI 2a: −2.46 to −2.31, and mALBI 2b/3: −1.90 to −1.75) in our past report [28], detailed assessment ability of ALBI score for hepatic function was very useful in TKI treatment. In addition, Ueshima et al. [29] reported that better ALBI grade (ALBI 1) affected objective response (odds ratio: 3.32, 95% CI: 1.04–10.50) and discontinuation of LEN due to AEs (odds ratio: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.06–0.69) in 82 patients treated with LEN. In our past report, mALBI 2b or greater (ALBI score >–2.27) was shown to be a prognostic factor for poor prognosis of u-HCC patients receiving LEN, while Child-Pugh score was not found to be indicative of prognosis [30], indicating that ALBI and four-grade mALBI have a better assessment ability regarding hepatic function as compared to Child-Pugh score with regard to patients undergoing LEN treatment for u-HCC. In the present study, non-mALBI grade 1/2a at the start of LEN indicated a significant risk for decline to CPB during LEN treatment (HR 2.552, 95% CI: 1.577–4.129; p < 0.001). Based on these results, hepatic function at the start of LEN might have a great impact on the prognosis of u-HCC patients treated with LEN.

In the present cohort of 73 patients with PD, 43.8% (n = 32) were considered eligible for additional post-progression treatment with LEN. Post-progression LEN therapy is currently an unmet clinical need. Among our 156 patients, 36.5% (n = 57) received LEN as second- or third-line treatment. In other words, for some patients, there are few additional therapeutic options available other than RAM. In the REACH-2 trial, that drug only showed therapeutic efficacy when given as second-line treatment in patients with SOR failure and elevated AFP (≥400 ng/mL). Thus, a current question in real-world clinical practice is whether RAM can be used for effective post-progression treatment following LEN failure in patients with elevated AFP. Of the present cohort, only 20.0% met the eligibility criteria for RAM at the time of PD determination, which was similar to the percentage of patients treated with SOR who were found eligible for RAM (23.3%) in the study by Kuzuya et al. [31]. Introducing LEN in patients with better hepatic function (mALBI 1/2a) might enhance the possibility of eligibility for RAM as a post-progression treatment. Clinical trial findings and accumulation of real-world data regarding RAM treatment as post-progression treatment following LEN treatment are necessary.

Prolonging PPS in u-HCC patients might contribute to improve OS [9]. Terashima found that the correlation between median OS and median TTP was weak (r = 0.50), while that between median OS and median PPS was strong (r = 0.78) [32]. The process of development of new anti-cancer drugs for u-HCC is complicated and difficult; thus, establishment of the best sequential order of currently available MTA is a matter of urgency. In a future study, we intend to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of MTA given as therapy in different sequences.

The present study has some limitations, including its retrospective nature. Furthermore, though multiple centers participated, the number of analyzed patients was small and the observation period limited. Nevertheless, when possible, introduction of TKI/MTA therapy including LEN is important for patients with better hepatic reserve function (mALBI 1/2a), as that can increase the chance of undergoing post-progression treatment, which has the potential to improve PPS.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent for performing TKI treatment was obtained from all patients. The present study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital (No. 30–66).

Disclosure Statement

Conflicts of interest of Dr. Takashi Kumada (2018): lecture − Eisai. Conflicts of interest of Prof. Masatoshi Kudo, MD, PhD (2018): lecture − Bayer, Eisai, MSD; grant − EA Pharma, Eisai, Gilead, Takeda, Otsuka, Taiho; advisory consulting − Eisai, Ono, MSD, BMS. Conflicts of interest of Dr. Koichi Takaguchi (2018): lecture − AbbVie.

Author Contributions

Atsushi Hiraoka: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing original draft; Takashi Kumada: conceptualization, review, editing; Kunihiko Tsuji, Koichi Takaguchi, Ei Itobayashi, Kazuya Kariyama, Hironori Ochi, Kazuto Tajiri, Masashi Hirooka, Taeang Arai, Noritomo Shimada, Toru Ishikawa, Akemi Tsutsui, Hiroshi Shibata, Toshifumi Tada, Hidenori Toyoda, Kazuhiro Nouso, Norio Itokawa, Kouji Joko, Yoichi Hiasa, Kojiro Michitaka, Michitaka Imai, Masanori Atsukawa, Korenobu Hayama, Takuya Nagano, Yohei Koizumi, Shinya Fukunishi, Keisuke Yokohama: data curation; Masatoshi Kudo: review, editing.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. SHARP Investigators Study Group Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul;359((4)):378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Jan;10((1)):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. RESORCE Investigators Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan;389((10064)):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Mar;391((10126)):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kariyama K, Takaguchi K, Itobayashi E, Shimada N, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and the HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Therapeutic potential of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in clinical practice: multicenter analysis. Hepatol Res. 2019 Jan;49((1)):111–7. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kariyama K, Takaguchi K, Atsukawa M, Itobayashi E, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group, HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Clinical features of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions: multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019 Jan;8((1)):137–46. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group. HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Important clinical factors in sequential therapy including lenvatinib against unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2019 Jul;:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000501281. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, Kudo M. Ramucirumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in REACH-2: the true value of α-fetoprotein. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Apr;20((4)):e191. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Takata N, Nakagawa H, Toyama T, Arai K, et al. Post-progression survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated by sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2016 Jun;46((7)):650–6. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973 Aug;60((8)):646–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb;33((6)):550–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Michitaka K, Toyoda H, Tada T, Ueki H, et al. Usefulness of albumin-bilirubin grade for evaluation of prognosis of 2584 Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May;31((5)):1031–6. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kudo M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Itobayashi E, et al. Real-Life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics) Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Grade as Part of the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology: A Comparison with the Liver Damage and Child-Pugh Classifications. Liver Cancer. 2017 Jun;6((3)):204–15. doi: 10.1159/000452846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Kumada T, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Kokudo N, et al. Validation and Potential of Albumin-Bilirubin Grade and Prognostication in a Nationwide Survey of 46,681 Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients in Japan: The Need for a More Detailed Evaluation of Hepatic Function. Liver Cancer. 2017 Nov;6((4)):325–36. doi: 10.1159/000479984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Tsuji K, Takaguchi K, Itobayashi E, Kariyama K, et al. Validation of Modified ALBI Grade for More Detailed Assessment of Hepatic Function in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Multicenter Analysis. Liver Cancer. 2019 Mar;8((2)):121–9. doi: 10.1159/000488778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009 Jan;45((2)):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Feb;30((1)):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruix J, Sherman M, Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005 Nov;42((5)):1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Martino M, Marin D, Guerrisi A, Baski M, Galati F, Rossi M, et al. Intraindividual comparison of gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MR imaging and 64-section multidetector CT in the Detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Radiology. 2010 Sep;256((3)):806–16. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sano K, Ichikawa T, Motosugi U, Sou H, Muhi AM, Matsuda M, et al. Imaging study of early hepatocellular carcinoma: usefulness of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2011 Dec;261((3)):834–44. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiraoka A, Ichiryu M, Tazuya N, Ochi H, Tanabe A, Nakahara H, et al. Clinical translation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma following the introduction of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with Sonazoid. Oncol Lett. 2010 Jan;1((1)):57–61. doi: 10.3892/ol_00000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiraoka A, Hiasa Y, Onji M, Michitaka K. New contrast enhanced ultrasonography agent: impact of Sonazoid on radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Apr;26((4)):616–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan . 6th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 2015. The general rules for the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer; p. p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013 Mar;48((3)):452–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kudo M, Hirooka M, Koizumi Y, Hiasa Y, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics) Hepatic Function during Repeated TACE Procedures and Prognosis after Introducing Sorafenib in Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: multicenter Analysis. Dig Dis. 2017;35((6)):602–10. doi: 10.1159/000480256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Suzuki E, Kanogawa N, Saito T, et al. Liver function assessment according to the Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) grade in sorafenib-treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2015 Dec;33((6)):1257–62. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yukimoto A, Hirooka M, Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Ochi H, Joko K, et al. Using ALBI score at the start of sorafenib treatment to predict regorafenib treatment candidates in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jan;49((1)):42–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, et al. On behalf of the Real-Life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Early relative change in hepatic function with lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2019 Aug;:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000502095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueshima K, Nishida N, Hagiwara S, Aoki T, Minami T, Chishina H, et al. Impact of Baseline ALBI Grade on the Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated with Lenvatinib: A Multicenter Study. Cancers (Basel) 2019 Jul;11((7)):11. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group, HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Prognostic factor of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions-Multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019 Jul;8((8)):3719–28. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuzuya T, Ishigami M, Ito T, Ishizu Y, Honda T, Ishikawa T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of candidates for second-line therapy, including regorafenib and ramucirumab, for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after sorafenib treatment. Hepatol Res. 2019 Apr;:hepr.13358. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Toyama T, Arai K, Kawaguchi K, Kitamura K, et al. Surrogacy of Time to Progression for Overall Survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Systemic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Liver Cancer. 2019 Mar;8((2)):130–9. doi: 10.1159/000489505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data