Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to translate and culturally adapt the original version of the STarT Back Screening Tool (SBST) to Spanish for different population subgroups.

Design

Translation and cultural adaptation of a questionnaire.

Setting

Primary care settings.

Method

Thirty-eight people distributed by: gender; adults and elderly; and with or without pain. Phases: a) Forward translation (English-Spanish); b) Evaluation of the clarity, the acceptability and the familiarity of the content of the obtained Spanish version by means of cognitive interviews to participants, and c) Translation of the final Spanish version of the questionnaire back into the original language.

Results

The participants interviewed indicated that most of the items of the questionnaire were clear and comprehensible, showing greater difficulty in understanding in the dimensions of disability and anxiety. Furthermore, the questionnaire was more difficult to undertand by the elderly and patients with a previous non-specific low back pain episode.

Conclusion

The Spanish version of the SBST questionnaire was obtained, which was shown to be comprehensible and adapted to the general population in Spain. Due to being short and easy to use, it is a potentially useful tool for use in primary care.

Keywords: Low back pain, Primary care, Spanish, Adults, Classification

Resumen

Objetivo

El objetivo de este estudio fue traducir y adaptar culturalmente la versión original del STarT Back Screening Tool (SBST) al español en diversos subgrupos de población.

Emplazamiento

Centros de Atención Primaria.

Diseño

Traducción y adaptación de un cuestionario.

Método

Treinta y ocho personas, distribuidos por: género, adultos y ancianos, y con o sin dolor. Fases: a) la traducción (inglés-español); b) evaluación de la claridad, la aceptabilidad y la familiaridad de los contenidos de la versión en español obtenidos por medio de entrevistas cognitivas a los participantes, y c) retro-traducción de la versión final en español del cuestionario de nuevo en el idioma original.

Resultados

Los participantes entrevistados indicaron que los ítems del cuestionario fueron claros y comprensibles en la mayoría de ellos, mostrando una mayor dificultad de comprensión de las dimensiones de la discapacidad y la ansiedad. Además, el cuestionario ha mostrado mayor dificultad de comprensión en los ancianos y las personas con un anterior episodio de dolor lumbar.

Conclusión

Se obtuvo la versión española del cuestionario SBST. El cuestionario español SBST ha demostrado ser comprensible y adaptado a la población general en España. Debido a su nivel más bajo y facilidad de uso es una herramienta potencialmente útil para su uso en Atención Primaria.

Palabras clave: Dolor de espalda baja, Atención Primaria, Español, Adultos, Clasificación

Introduction

Non-specific low back pain (of unknown origin) is one of the most frequent ailments in primary care consultations, with visit rates ranging between 7 and 9% of affected by lumbar ailments in the general population.1 It is impossible to know the original cause of 80 per cent of these episodes.2, 3 Low back pain consumes an enormous amount of health care resources through consultations, checkups, and prescriptions, and also societal resources, predominantly from sick leave.4 A majority of the costs attributable to low back pain is caused by the small proportion of patients who develop chronic symptoms.4 As a consequence, there is consensus among the research community that the provision of methods to help clinicians identify patient subgroups that are at risk of persistent pain and disability is a high research priority.5

The STarT Back Screening Tool (SBST) was recently published as a prognostic stratification method to identify subgroups of patients to guide the provision of early secondary prevention in primary care.6 The tool uses prognostic indicators that are potentially modifiable by treatment within a brief screening tool format, with established scoring rules to classify patients into one of three subgroups; low, medium and high risk.6 The SBST has been demonstrated as having equivalent psychometric properties to the popular tool “Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire” (OMPSQ),7 in addition to being shorter and simpler.8

The SBST, while available in the English language, is currently not available in Spanish. We therefore designed this study to translate and culturally adapt the SBST into Spanish and to obtain a reliable and feasible Spanish version of SBST.

Material and methods

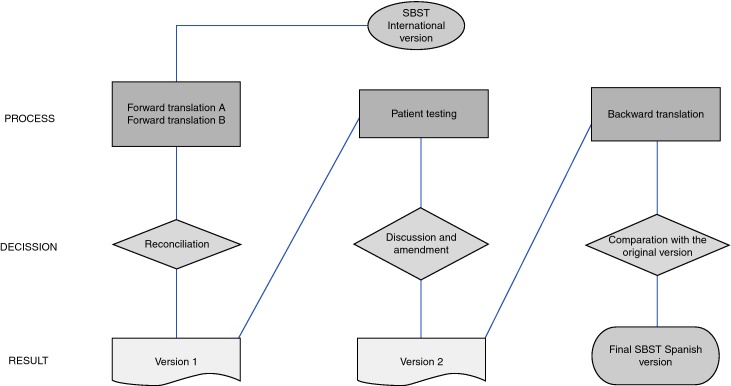

We applied the recommended methodology for the translation and cultural adaptation of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaires used in others studies,9 including direct and inverse translation and cognitive interviews.10, 11 An overview of the translation used and cultural adaptation processes are described in the scheme of the study image.

Phase 1; Forward translation

First, two native Spanish translators, bilingual in the language of the original tool (English), performed two forward translation versions of the SBST: each translator independently produced a forward translation of the original items, instructions and response options. To produce a combined version (version 1) both translators and one local project manager discussed the two translations and agreed on a single version with the aim to produce a conceptually, semantic and easy to understand equivalent translation12, 13 of the original questionnaire. This process led to additional changes to the original version where words or concepts were untranslatable, or where words or terms had a specific meaning in one language but a semantically different or secondary meaning in the Spanish language.

Phase 2; Patient testing using cognitive interviews

The next step (patient testing) was to administer the translated questionnaire to a sample of adult respondents to determine whether the translation (items, instructions and responses options) was acceptable, easy to understand, and to evaluate the tool's clarity. This was tested by means of cognitive interviews using “probing and paraphrasing” methodology10, 11 to provide patient feedback in respect to errors or misunderstandings produced by the translation process. Such cognitive interview techniques are known to minimise measurement error introduced by the translation process and enable respondent misunderstandings to be rectified.14

Cognitive interviews were face to face and were conducted in an egalitarian manner by a native Spanish speaker with 38 adults aged 35 to 80 years old, and findings were collated and stratified using gender (male or female), age (35-54 or 55-80 years) and ailment (healthy or back pain) (Table 1). All participants signed a written informed consent.

Table 1.

Number of men and women in the interview sample stratified by younger and older adults and whether or not they had experienced a recent episode of low back pain.

| Younger adults (Aged 35 to 55) |

Older adults (Aged 55 to 80) |

Total (Mean age = 59 ± 4.2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Backache | Healthy | Backache | Healthy | Backache | |

| Women | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Men | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 |

The interviews consisted of:

-

a)

An evaluation of the ease of comprehension of each item using dichotomous response options of either: 1) clear and comprehensible or 2) difficult to understand.

-

b)

An evaluation of the ease of comprehension of each item using a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10 (0 very easy to understand to 10 very difficult to understand).

-

c)

An investigation of individuals’ interpretations of SBST items with suggestions for improvements by asking those interviewed to express in their own words the perceived meaning of each item and then to re-phrase each item to verify their understanding.

Where problems were identified, alternative linguistic changes were proposed and following this process version 2 of the questionnaire was obtained.

Phase 3; Back-translation

The final phase was to back-translation of the Spanish version 2 of the SBST into English using a local professional translator, who was a native speaker of English and fluent in Spanish) and was blind to the original English version of the SBST questionnaire. The back-translated SBST was then compared to the original by the local project manager and the author of the original English SBST to detect any misunderstandings or inaccuracies in the translation process.

The translation methodology used was designed to reduce the cultural and social bias that may have resulted if only one translator was responsible for the translation, and aimed to ensure that the final version obtained had conceptual and semantic equivalence to the English SBST with respect to the items, instructions and response options.

General scheme of the study. STarT Back Screening Tool.

Results

Phase 1; Forward translation

The results from the two independent forward translations of the SBST are provided in Table 2. Following a joint discussion between the translators about some of the words, concepts and terms used, a few small changes were made to produce version 1:

-

-

In the 9th item, we decided to use “estado molestando” instead of “como de molesto”.

-

-

In the first item, we used “se ha irradiado” instead of “se ha extendido”.

-

-

In the 3th item, we used “he tenido” instead of “yo he tenido” to reflect a more colloquial Spanish style.

-

-

For item 4, we used the word “debido a” instead of “a causa de” again to reflect a more colloquial form of Spanish.

-

-

For item 6 we used the word “por mucho tiempo” instead of “un montón de tiempo” as this would be better understood.

-

-

For item 7, we used the verb “notar” instead of “sentir” again to reflect a more colloquial form of Spanish.

-

-

For item 8, we decided to use “habitualmente” instead of “normalmente” because it was agreed that this sounded better.

Table 2.

Items in the Spanish version of the STarT Back Screening Tool

| 1. Mi dolor de espalda se ha extendido a lo largo de mi pierna(s) en alguna ocasión en las últimas dos semanas |

| 2. Me ha dolido el hombro o cuello en alguna ocasión en las dos últimas semanas |

| 3. En las últimas dos semanas, solo he caminado distancias cortas por mi dolor de espalda |

| 4. En las dos últimas semanas, me he vestido más lentamente de lo normal por mi dolor de espalda |

| 5. No es seguro ser físicamente activo con mi dolor de espalda |

| 6. Me he preocupado mucho por mi dolor de espalda en las dos últimas semanas |

| 7. Noto que mi dolor de espalda es terrible y que nunca irá a mejor |

| 8. En general en las últimas dos semanas, no he disfrutado de las cosas lo que habitualmente disfruto |

| 9. En general, ¿como le ha molestado su espalda en las dos últimas semanas? |

Phase 2; Patients testing using cognitive interviews

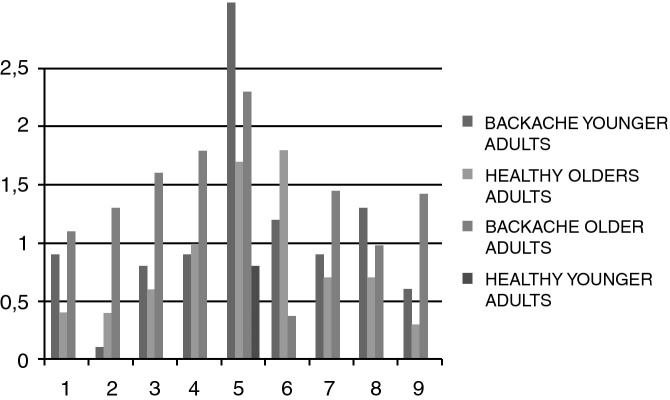

The second version of the questionnaire obtained is presented in Table 2. Patients did not identify any major difficulties in comprehension of first version, as all the participants reported the questionnaire as clear and comprehensible on the dichotomous response options. However, the more sensitive measure of the numerical response rating revealed that there was a degree of greater difficulty of understanding for items 5 and 6 (disability and anxiety items) across the younger and older age groups (Figure 1). Therefore these items were slightly modified; for item 5 (disability) the wording was changed from “no es realmente seguro para una persona como yo ser físicamente activo” to the more direct phrasing of “no es seguro ser físicamente activo con dolor de espalda”. For the 6th item the wording was changed from “preocupaciones han estado pasando a través de mi mente durante mucho tiempo en las últimas dos semanas” to an active voice form of “me he preocupado mucho por mi dolor de espalda en las últimas dos semanas”.

Figure 1.

Average difficulty of items 1-9 by age and ailment. Scale range was from 0 to 10 (0 very easy to understand to 10 very difficult to understand).

The investigation of individuals’ interpretations of SBST items and paraphrasing exercise verified that the majority of people interviewed fully understood each of the SBST items. However, it was observed that a number of participants used a direct question that included the infinitive form of the verbs included and the items written in the perfect past tense were repeated when using their own words with the simple past tense. Therefore, it was decided to use the infinitive and simple past verb forms as much as possible in the definitive version. Never the less, during the re-formulation (paraphrasing) of the items by the subjects, they consistently re-phrased the referred leg pain item translated as “irradiar a través de mi pierna” to “extender a través de mi pierna”, and so for this reason the verb ‘extending’ was used instead of ‘radiating’. In addition, the results from the cognitive interviews revealed that participants were more likely to recommend changes if they had experienced a recent episode of low back pain or were in the older age category (Figure 1).

Phase 3; Back-translation

The back-translation of the SBST is included in Table 2. When this was presented to the authors of the original English version of the tool, no further additional changes were required.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to translate and culturally adapt the original version of the SBST into Spanish. This was performed using a sample of younger and older adults with and without recent low back pain to ensure the translated version had face validity and was easily understood. To our knowledge, this is the first Spanish screening tool for idiopathic low back pain in primary care and provides a standardised methodology with which to develop future translations and cultural adaptations of this tool.

This study has been carried out using a sample from the general population of equally distributed younger and older adults and participants with and without idiopathic low back pain. The strength of this methodology is that it is likely to provide a translation that is comprehensible and generalisable to the Spanish general population. However, one weakness was that the current study did not test the translated tool's ease of understanding among individuals with cognitive difficulties or whose pain was controlled using pain medication. According to Andresen EM et al.,15 subjects with previous episodes of non-specific low back pain and elderly people report a poor Self-rated Health and it is very important to study cognitive responses in elderly people in health related questionnaires,16 and some authors propose developing questionnaires with help of elderly people as their comprehension is essential.17

Further studies need to analyse the measurement properties of the translated SBST including reliability, validity and feasibility among the Spanish general population and among patients with idiopathic low back pain. However, this tool can add value to assess the effects of interventions such as physical therapies or pharmachological treatments.that can identify subgroups of patients to guide the provision of early secondary prevention in primary care.6 Nevertheless, this translated Spanish version of the SBST will provide a practical and user friendly tool to identify prognostic subgroups of patients with low back pain that require targeted and increasing complexity of treatment, which is a major reason for visits to primary care.

Key points

What is already known on this subject?

-

•

SBST is one of the most internationally used tools for screening low back pain and is noted for its ease of administration, validity and reliability, development in different cultures and applicability in economic analysis.

-

•

There is not a direct and specific Spanish version of SBST.

What does this study contribute?

-

•

The Spanish version of SBST for adult and elderly.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement

Junta of Extremadura (Young & Sports, Health & Dependence Ministeries) for granting Exercise Looks After You (El Ejercicio Te Cuida).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.aprim.2010.05.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Dunn K.M., Croft P.R. Classification of low back pain in primary care: using “bothersomeness” to identify the most severe cases. Spine. 2005;30:1887–1892. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000173900.46863.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jager J.P., Ahern M.J. Improved evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain: guidelines from the National Health and Medical Research Council are now available. Med J Aust. 2004;181:527–528. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European guidelines for the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002; 73 Suppl:20-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.González Viejo M.A., Condón Huerta M.J. Disability from low back pain in Spain. Med Clin (Barc). 2000;114:491–492. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster N.E., Dziedzic K.S., van der Windt D.A., Fritz J.M., Hay E.M. Research priorities for non-pharmacological therapies for common musculoskeletal problems: nationally and internationally agreed recommendations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill J.C., Dunn K.M., Lewis M., Mullis R., Main C.J., Foster N.E. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:632–641. doi: 10.1002/art.23563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westman A., Linton S.J., Ohrvik J., Wahlen P., Leppert J. Do psychosocial factors predict disability and health at a 3-year follow-up for patients with non-acute musculoskeletal pain? A validation of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill J.C., Dunn K.M., Main C.J., Hay E.M. Subgrouping low back pain: A comparison of the STarT Back Tool with the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gusi N., Badía X., Herdman M., Olivares P.R., Translation Cultural Adaptation of the Spanish Version of EQ-5D-Y Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents. Aten Primaria. 2009;41:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsyth B.H., Lessler J.T. Cognitive laboratory methods: a taxonomy. In: Biemer P.P., Groves R.M., Lyberg L.E., Mathiowetz N.A., Sudman S., editors. Measurement errors in surveys. Wiley; New Yersey: 2004. pp. 390–418. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad F, Blair J, Tracy E. Verbal reports are data! A theorical approach to cognitive interviews. FCSM Conference; 1999.

- 12.Herdman M., Fox-Rushby J., Badia X. ’Equivalence’ and the translation and adaptation of health-related quality of life questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:237–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1026410721664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herdman M., Fox-Rushby J., Badia X. A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:323–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1024985930536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varni J.W., Seid M., Kurtin P.S. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andresen E.M., Vahle V.J., Lollar D. Proxy reliability: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:609–619. doi: 10.1023/a:1013187903591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senin U., Cherubini A. Functional status and quality of life as main outcome measures of therapeutic efficacy in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1996;22(Suppl 1):567–572. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(96)87000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sixma H.J., van Campen C., Kerssens J.J., Peters L. Quality of care from the perspective of elderly people: the QUOTE-elderly instrument. Age Ageing. 2000;29:173–178. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.