Abstract

Literature on Latino men and intervention for intimate partner violence/abuse (IPV/A) is slim. Over 100 men have voluntarily sought help for IPV/A perpetration from “The Men’s Group” (TMG) at St. Pius V parish in Chicago, IL (US) and remained engaged for extended periods. Given the rarity of prolonged non-court mandated engagement in batterer intervention programs (BIPs), a case study was conducted to explore how TMG functions. Drawing on multiple data sources, this study examined development and implementation of TMG, while also investigating contextual factors, motivators and facilitators of participants’ involvement. Data revealed that TMG functions within a supportive community context by using a mixture of traditional techniques and innovative practices, creating a unique treatment modality. The program was found to be culturally-sensitive and spirituality-based. Reasons for initial attendance varied but included: (1) fear of losing or actual loss of their partner/family; (2) acknowledging a problem and desiring to change for self or others; and (3) a desire to reach inner peace. Three themes shed light on why men remain engaged in TMG, including: (1) being met with respect by facilitators; (2) experiencing TMG as “family”; and (3) gaining benefits. Reliance upon the criminal justice system is not enough to address IPV/A perpetration. This program shows promise as an alternative or supplement to traditional BIPs, which typically rely on clients being court-mandated to attend treatment. Given the widespread nature of IPV/A, understanding the operation of potential community-based alternatives or supplements to BIPs is critical in widening access to treatment.

Keywords: domestic violence, behavioral issues, intimate partner violence, social support, psychosocial and cultural issues, behavior modification/change, masculinity, gender issues and sexual orientation

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines Intimate Partner Violence/Abuse (IPV/A) as “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner” (Breiding et al., 2015, p. 11). Nearly one in three women and one in ten men in the United States have experienced physical assault, sexual assault, and/or stalking by an intimate partner (Black et al., 2011). IPV/A, commonly referred to as domestic violence (DV), has been associated with negative consequences for individuals, families, and communities. Identified as a pervasive yet preventable public health problem, the World Health Organization has noted intervention for perpetrators as one of the most important areas of focus in the efforts to end IPV/A (Rothman et al., 2003). Thus far, research has focused on court-mandated programming, which has received significant criticism related to engagement and effectiveness.

Traditional Interventions for IPV Perpetration

The U.S. criminal justice system has responded to DV by criminalizing certain forms of IPV/A. However, it is estimated that only 1% of men who commit DV are actually arrested and convicted (Stark, 2007). Upon conviction, many offenders are subsequently court-mandated to obtain treatment as a condition of their parole or probation (Dalton, 2007). DV offenders may participate in batterer intervention programs (BIPs) in addition to or in lieu of incarceration (Herman et al., 2014). Also known as partner abuse intervention programs (PAIPs), most state standards endorse group-style psycho-educational or cognitive behavioral focused treatment. Even though 90% of PAIP participants enter treatment because of court-mandate, usually only 50% complete treatment (Daly & Pelowski, 2000). Increased attendance and engagement are strongly linked to reduced recidivism (Gondolf, 2012). However, the overall evidence on traditional PAIPs effectiveness in reducing DV remains mixed (Arias et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2019). A number of innovations have been introduced to PAIPs (including voluntary programming) in an effort to improve attendance and engagement. Yet, significant gaps in knowledge about voluntary community-based PAIPs remain.

Faith-Based Partner Abuse Intervention

One form of alternative community-based programming has been faith-based intervention. While religion can be used as a means of control within intimate partnerships (Davis, 2015; Lira et al., 1999; Starr, 2017), some suggest religion may also be used in treatment for challenging and dismantling the problem of IPV/A. Theologian Jeanne Hoeft (2009) endorses religion and culture as useful tools for encouraging the resistance of IPV/A because of the power they hold in guiding many people’s lives. This line of thought and similar philosophies have led to the development of a number of faith-based PAIPs (Kroeger & Nason-Clark, 2010).

There is no clear or uniform definition for what it means to be a “faith-based” social service organization (Jeavons, 1997). Several scholars have noted that such inconsistencies in the definition of “faith-based” organizations cause confusion in understanding the true nature of social service provision (Ebaugh et al., 2006; Sider & Unruh, 2004). Ebaugh et al. (2006) suggest that categorization can range from faith-related to faith-saturated, with faith-based acting as a mid-point. Regardless, little is known about the context and function of faith-based PAIPs or their participants.

Nason-Clark et al. (2004) published the first empirical study documenting characteristics of faith-based PAIP participants. Review of 1,059 closed case files revealed that participants in a Washington state faith-based PAIP were more likely to be white (79.8%), married (47.3%), and be employed (87.4%), when compared to participants in a secular program. Furthermore, when compared to court mandated participants, men who were encouraged by religious leaders to enroll in a PAIP were more likely to complete treatment (Nason-Clark et al., 2004).

In depth interviews (n = 55) with program completers of an Oregon state program shed light on the implementation of a faith-based program that was certified to treat both court mandated and voluntary clients. Participants reported that group facilitators did not proselytize, appeal to the participant’s spiritual heart to reduce perpetration, or require religious or spiritual reflection. Instead, data revealed that the client controlled how their religio-spirituality1 was integrated into treatment (Nason-Clark & Fisher-Townsend, 2015). Contrary to reports about secular PAIPs being confrontational (Crane & Eckhardt, 2013), participants in the Oregon state faith-based PAIP reported feeling part of a non-judgmental environment and were held accountable in a non-confrontational manner. Faith-based PAIP staff used a participants’ voluntary use of religious language as a resource for positive change and incorporated relevant components of the person’s faith into the individuals’ treatment process (Nason-Clark & Fisher-Townsend, 2015).

Culturally-Sensitive Intervention for IPV Perpetration with Latino Men

Generally, cultural sensitivity is considered a hallmark of strong intervention programming (Barrera et al., 2013). Despite the Latinx2 population being the largest ethnic group in the US (Flores, 2017), and rates of IPV estimated as being between 17%–68% (Black et al., 2011; Caetano et al., 2000; Klevens, 2007; Straus & Smith, 1990), a dearth of investigation on IPV/A perpetration amongst Latino men remains (Cummings et al., 2013).

Few studies have examined culturally relevant PAIP programming for Latino men (Babcock et al., 2016). Celaya-Alston (2010) conducted a study that resulted in a community defined DV intervention for Mexican immigrant men. The curriculum was designed in collaboration with Latino men in order to incorporate culturally-specific topics relevant to IPV/A cessation. Although pre-post testing showed improvement in knowledge, the sample size (n = 9) was too small for statistical analyses. A smaller number of qualitative post-treatment interviews (n = 3) suggested that the participants expanded their definitions of DV, were satisfied with the program and would attend more sessions. Parra-Cardona et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative evaluation study of Latino men (n = 21; 20 Mexican immigrant) in a culturally-adapted Spanish version of the Duluth3 model program. Men in the study reported that the program helped them to engage in self-reflexivity, recognize the need for egalitarian relationships, and challenge violence as acceptable, while also integrating discussions about Latino values (i.e., respect, machismo) and experiences (i.e., discrimination).

The Need for the Co-Existence of Spirituality and Culture in Programs for Latino Men

Two innovative studies have looked at the need for or incorporation of both spirituality and culturally-specific programming into PAIP treatment for Latino men. Welland and Ribner (2001) surveyed 159 Mexican immigrant men mandated to attend a California PAIP. Ninety-five percent of respondents self-identified as Christian. Of these, 80% were Catholic. Eighty-nine percent stated that their religion was important in their daily life, and for 51% [religion] was very important (Welland & Ribner, 2001). A follow-up qualitative study revealed that male Mexican immigrant PAIP participants, “. . .placed considerable value on their spiritual beliefs and stated that they wished to be guided by them in their behavior. They [participants] also agreed that their church is against violence to one’s partner, and endorses values [such] as respect and love for others, and caring for one’s family” (Welland & Ribner, 2010, p. 804). The findings from this study suggested that the following specialized content was needed for a culturally adapted PAIP servicing Latino IPV/A offenders (Welland & Wexler, 2007, p. xvii):

Emphasis on the discussion of gender roles, masculinity, and machismo

Teaching about the treatment and education of children

Recognition of the experience of discrimination against immigrants and women

Discussion of the changes in the roles of people after immigration

Open discussion of sexual abuse in intimate relationships

Inclusion of spirituality associated with the prevention of family violence

Research on culturally-tailored and faith-based PAIPs serving Latino men is scant. Most programming and the largest studies have focused on mandated participants of secular programs (Babcock et al., 2016; Cannon, 2016). With the exception of a few studies (Gottzén, 2019; Tutty et al., 2019), there are also substantial gaps in the literature on voluntary participation in PAIPs. The purpose of this article is to help fill some of these gaps by reporting on an in-depth case study of a culturally sensitive, spiritually-based and voluntary PAIP serving Latino men. No published study to date has examined the combination of all these elements in a BIP.

The Current Study

Setting

Chicago, IL is a large Midwestern city in the United States with the second largest Mexican-born population in the country (Misra, 2014). Pilsen is a neighborhood in Chicago’s lower southwest region. Eighty-seven percent of Pilsen residents are Hispanic/Latinx (predominately Mexican immigrant). Low socio-economic status is a risk factor for IPV perpetration (Cunradi et al., 2000; Mancera et al., 2017) and 52.47% of residents in Pilsen live below the poverty line.

St. Pius V, a Catholic parish located in Pilsen, has developed a rich history of social and political engagement in Pilsen (Dahm & Harper, 1999; Grossman et al., 2000; Pallares & Flores-González, 2010) while also becoming the community’s most populous church (Badillo, 2005). By 2013, St. Pius V was home to the largest known parish-based DV program in the United States (Starkey, 2015). The HOPE Family Services program (referred to hereafter as the HOPE program) provides parenting courses, survivors support, children’s support services, youth dating violence prevention, services for perpetrators, and individual and couples4 counseling. Since 2011, over 400 men have voluntarily sought help for IPV/A perpetration through “The Men’s Group” (TMG), which is a service within the HOPE program. Anecdotal and program reports suggest that over 100 of these men have remained consistently engaged in the TMG for several sessions and/or years.

Approach

This study employed a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, a process that unites community members and researchers in equal partnership to design and conduct meaningful research for the community (Israel et al., 1998). This approach was selected to: (a) ensure that the program under study would gain useful information; (b) invert the historically exclusionary research practices in communities of color into a collaborative research model, whereby the community acts as a true partner; and (c) improve the validity of the study by enhancing and refining procedures based on the insights of community members. A guiding collaborative/advisory board (CAB) with relevant stakeholders was convened to achieve the goal of conducting sound and safe research. The CAB consisted of representatives from a local DV victim-survivor service agency, two local traditional PAIPs (serving primarily court-mandated participants), a co-founder of the HOPE program/St. Pius V Associate Pastor, a representative of a local School of Social Work, and the principal investigator. An intrinsic case study was adopted as the method for investigation because of the uniquely high number of voluntary participants in TMG (Creswell & Poth, 2017; Stake, 1995).

Dependability and Credibility

Creswell (2003) describes qualitative case study as a method that is employed to gain an in-depth understanding of a “program, an event, an activity, a process, of one or more individuals” (p. 15). Case studies are interested in the “process. . .in context rather than a specific variable, in discovery rather than confirmation” (Merriam, 1998, p. 19). A goal of case study research is to provide a holistic description of the case and doing so was necessary for examining how TMG functions. Often referred to as reliability in quantitative research, dependability in qualitative research is predicated upon a relative certainty that another researcher could obtain similar findings regarding the process of TMG. Validity, which is referred to as credibility in a qualitative case study, is facilitated by drawing upon multiple sources as a mechanism of constant assessment and re-assessment of data to ensure that findings accurately represent the case that is under investigation. Per expert recommendations, multiple data sources (i.e., interviews, focus groups, direct observations, archived document review, and researcher reflexivity notes) were used to inform findings (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003).

Sampling

This case study employed three purposeful sampling strategies (Creswell & Poth, 2017). Outlier (also known as “extreme or deviant”) sampling was used in selecting the site because of the unusually high numbers of voluntary participants. Criterion sampling was selected to collect data from individuals who were thought to be intimately familiar with TMG. This sampling was limited to interviews with staff, clergy, or administrators of the HOPE Program and to focus groups with currently engaged participants of TMG. For obtaining new leads and taking advantage of unexpected data points, an opportunistic or emergent sampling strategy was selected for conducting participant and non-participant observations (Patton, 2002). Emergent sampling was also used in selecting artifacts included in document review.

Data Collection

The PI collected artifacts associated with TMG as both contextual and facilitative evidence. These artifacts included marketing materials, parish newsletters, event invitations, posters, and educational materials. Newspaper articles, websites, videos, publicly available reports and internal documents were collected, reviewed, and assessed for relevance to the study and included as archival data. During the investigation, the PI visited websites and social media posts/sites regularly to capture any relevant changes.

Semi-structured individual interviews with parish leaders, administrators and staff were conducted in English by the PI (n = 4) and audio recorded. No incentive was provided to administrators, staff, or clergy. Recruitment for admin/staff interviews was done by posting flyers on site at St. Pius V. Recruitment for current participant focus groups was done by posting flyers at group meeting sites. Facilitators also announced the opportunity to participate at the end of two group sessions. Informed consent was conducted individually in the preferred language of the prospective participant prior to the focus group by the principal investigator (PI) and two Masters level research assistants (RAs). Attestation of informed consent was obtained from all participants. Focus groups with new and senior participants were convened and conducted in Spanish (n = 18; two groups of nine). A semi-structured interview, based on a pre-drafted and translated script, was used to direct the discussion. The questions were drafted by the PI in collaboration with the CAB member representing the parish (see Appendix A). The focus groups were audio recorded and translated into English by the member of the research team that facilitated the focus groups in Spanish. The focus groups were conducted at a local University to promote confidentiality. A $50 cash incentive and $10 cash travel stipend was provided to each person who participated.

A bilingual focus group leader was hired by the CAB in order to conduct the focus groups. She was also later hired by the PI to translate and record English versions of both focus groups. Two bilingual graduate social work student RAs were present to take observational notes on participant body language and summarize discussion content. Both RAs were available to assist with translation, back-translation, and confirmation that data was translated as accurately as possible. Each RA received 40–60 hr of DV training prior to joining the research team. Both the PI and focus group facilitator had masters degrees in social work, backgrounds in psychology, over 60 hr of DV training and a combined four years of experience facilitating Duluth model group treatment for court-mandated clients. The content expertise and training of the entire research team allowed the focus groups to be facilitated with a humanistic approach, relevant follow-up questions to be asked and notes to be taken from an IPV/A informed and social psychology perspective (Stewart & Shamdasani, 2015). Each focus group lasted approximately 2.5 hr.

The PI conducted observations of TMG sessions, programmatic events, community events, church services and functions over a period of nine months. Over 60 hr of observation and 30 pages of direct observation field notes and reflective memos were included as data in this study. The PI lived in the Pilsen neighborhood for 12 consecutive months during the data collection as a means of complete community immersion. After translation was conducted by the research team member and audio recorded in English, audio data from the focus groups and other interviews were all transcribed by a professional transcription service.

Ethical Considerations

The PI and RAs adopted best practices in assuring that participants, especially TMG members, understood what it meant to be a research participant. A short quiz of recommended best practices in consenting court-involved PAIP participants was adapted and included at the end of the consent procedure (Crane et al., 2013). CAB members and PhD-level scholars reviewed the semi-structured staff interview guide and participant focus group questions for appropriate language, substantive areas and length. The Internal Review Board of Washington University in St. Louis approved all procedures (ID #201611098; ID # 201607054).

Data Analysis

A constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was used to guide data analysis. Artifacts, including internal documents, newspaper articles, data from websites, social media posts/sites, newsletters and videos, were first examined for meaningful pieces of data. Pertinent information was then thoroughly read, interpreted, and reviewed by the PI multiple times in an iterative process as data from other sources were also collected and analyzed (Bowen, 2009). Supplementary to interviews and observations, these artifacts provided entirely new information, were scrutinized for both contradictions of and support for data from other sources (Altheide et al., 2008). The PI organized and sorted data from artifacts/documents using codes as they were developed and refined throughout the duration of the study. This data was then used to inform the research questions.

Dedoose, a web-based program, was used for data management of human subject data, direct observation field notes and reflective memos. The PI listened to (English version) audio files and read the transcripts multiple times to familiarize herself with the data. As Bernard (2013) describes, qualitative data analysis is “the search for patterns in data and. . .ideas that help explain why those patterns are there in the first place” (p. 394). An inductive approach was used to develop categories and subcategories through open coding, a process that organizes data into “boxes” as transcripts were reviewed line-by-line (Miles et al., 2013). The PI wrote and used a codebook based on the interview/focus group guiding questions for the initial independent sorting. The codebook and definitions were continuously revised/refined as needed. The PI then trained a RA, who was familiar with Mexican cultures, on qualitative coding procedures utilizing the previously written codebook. The RA then independently coded transcripts. The PI and RA then engaged in consensus coding and a third coder was available to decide on any unsettled discrepancies (Hill et al., 2005). This process was followed by axial coding, a process to “fit the pieces of the data puzzle together” (Miles et al., 2013). Using thematic analysis, central themes shedding light on the case were identified, selected, refined and used to inform research questions (Israel et al., 1998).

Strategies for Rigor

For quality assurance, member checking, triangulation (i.e., verifying information through multiple sources), rich descriptions, researcher reflexivity (i.e., memoing) and prolonged engagement were used as strategies to improve both dependability and credibility. Member checking was done throughout the study in a variety of forms as a mechanism for minimizing the researchers’ beliefs being imposed onto the data. RAs briefly summarized the main discussion points of the focus groups and verified the content with participants at the end of each focus group. Staff and administrators were provided verbatim transcripts of their recorded interviews to ensure the accuracy of their statements. In another act of member checking, preliminary findings were presented to staff, administrators, and clergy affiliated with the HOPE program in order to verify the results accurately represented TMG. Members confirmed findings, provided clarity, and corrected inaccuracies through open discussion. An example of corrections made were the descriptive terms used for naming weekly topic discussions (i.e., healthy relationship communication instead of relationship communication).

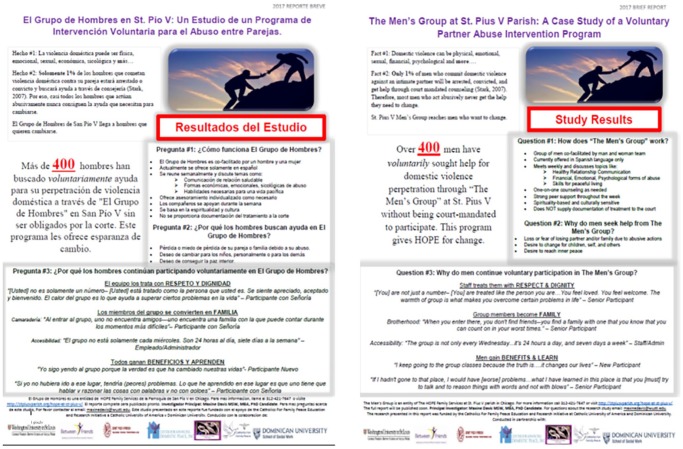

A member of the CAB and the PI co-designed a one-page brief summary of the study findings. RAs translated the brief in Spanish and translations were edited by the same (bilingual) board member before finalization. The brief (in both English and Spanish) was then provided to members of TMG to ensure that the findings accurately reflected their perception of how the group functions, why men join the program, and why men continue to be engaged in the group. The following statement was made in both Spanish and English as printed copies of the brief report were provided at the end of the final group session that the PI and RA observed (See Appendix B for the brief report):

Even though you may see us around from time to time, tonight is the last night that [RA/translator name] and I will be here in group. We would like to thank you all for welcoming us to learn more about the men’s group. It has been a pleasure to have been in this sacred space [referencing being present for six group session observations]. You have been vulnerable in front of us—for that I am grateful and I do not take it for granted. Please know that we will abide by the confidentiality of this group. No one’s names or detailed stories will be a part of our report. Here is a brief summary of the results—the full report will be available later. If you are interested in what I think I found you can look here [referencing handout Appendix B] in Spanish and English or talk to us. If we did not get it correct or if you think there is a problem with the way we describe the group please notify me or pass a message through [the group facilitators]. If I don’t hear anything, I will assume everything is ok and will move forward in publishing the report…..

(Principal Investigator, March 22, 2017)

Four months passed before the research team proceeded with writing up findings. Members of TMG made no requests to correct, change, or edit study findings. These strategies for quality assurance were adopted and employed because they are considered gold standard practices in qualitative data collection and analyses (Creswell & Clark, 2016).

Findings and Results

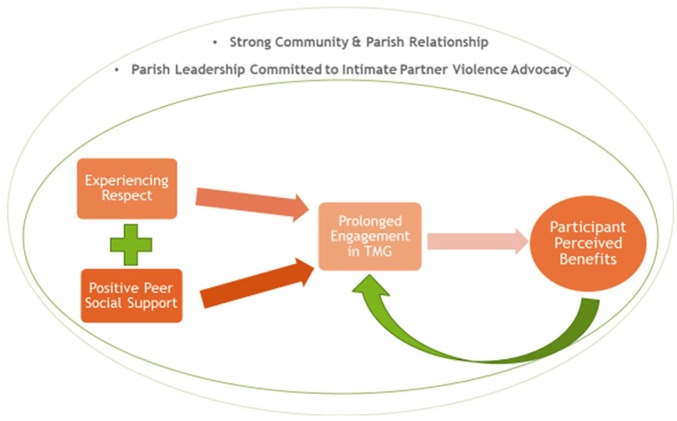

This study explored three major research questions. A snapshot of the results is presented in Table 1. However, these findings rest within the contextual conditions surrounding TMG, which are detailed at the beginning of this section. Of further importance, the major findings of this study led to the development of a theoretical model explaining prolonged engagement of non-court mandated men in partner abuse intervention programming, which is presented at the end of this section (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Brief Findings and Results Overview.

| Research Question | Data Sources/ Methods | Findings & Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1. What is TMG and how does function? (i.e., how did it start, any important contextual factors, how is it funded, what is it, who is it for, what do they do, etc.) | • Observations • Staff/Administrators Interviews • Participant Focus Groups • Archived Document Review |

TMG is a voluntary culturally-tailored, spirituality-based, and trauma-informed partner abuse intervention program for Spanish speaking men. TMG is part of a larger domestic violence service provider that is based out of St. Pius V parish in Chicago, IL. TMG encourages group members to volunteer, bond and support each other socially outside of group sessions. |

| 2a. What motivates currently involved participants to initially attend TMG? | • Participant Focus Groups • Staff/Administrators Interviews |

Participants of TMG are motivated to attend sessions for a variety of reasons. The most commonly reported factors involved desire for inner peace, fear of losing family or children, and acknowledging the presence of a problem |

| 2b. Why do currently involved participants remain engaged in TMG? | • Participant Focus Groups • Observations • Staff/Administrators Interviews |

Three primary themes emerged to answer the question of why men voluntarily remain as participants. They reported being met with respect and dignity by staff as a primary factor. They also emphasized the familial-like bonds they created with other group members, and a value of perceived learning benefits. |

Figure 1.

Emerging theoretical model for prolonged engagement of non-court mandated men in a parish-based partner abuse intervention program.

RQ 1: What is “The Men’s Group” (TMG) and how does it function?

Contextual Conditions Surrounding The Men’s Group

The larger context in which the HOPE program and TMG exists is integral to understanding how the TMG program developed and serves the participants. The two critical factors surrounding the environment of TMG are as follows:

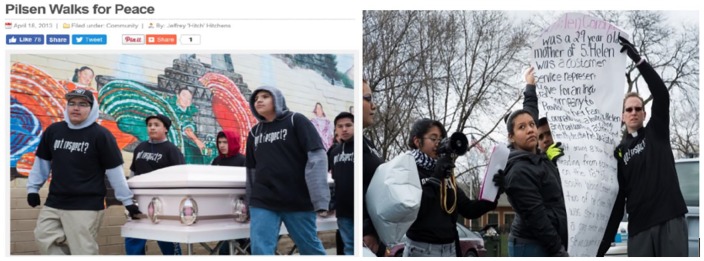

Strong Community and Parish Relationship

Based on numerous artifacts, including newspaper articles, scholarly publications exploring the community, and social media commentary, the parish leaders of St. Pius V are considered pillars of the Pilsen community (see Photo 1). These sources indicated that Parish leadership has had a long history of being involved in social issues of importance to the community, such as education enhancement, activism, economic empowerment, community peace building, and immigration reform.

Photo 1.

Context 1: Photo evidence of strong community and parish relationship.

Photo credits: Jeffrey “Hitch” Hitchens from: www.thegatenewspaper.com Permissions for reprint obtained.

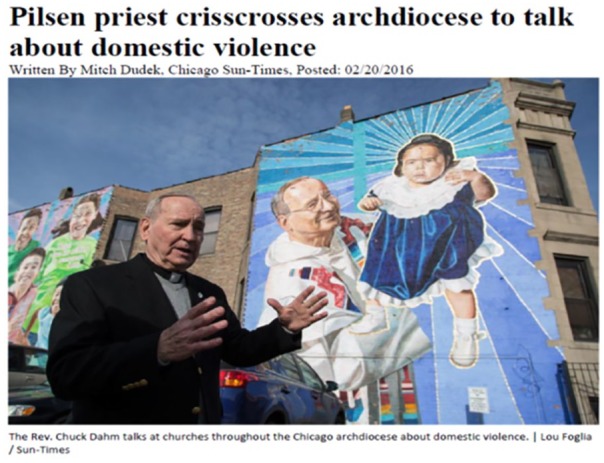

Parish Leadership Committed to Intimate Partner Violence Advocacy

Associate Pastor of St. Pius V Parish, Fr. Chuck Dahm, regularly speaks from the pulpit about domestic violence [sic]. This work extends beyond his home parish. In fact, the HOPE program at St. Pius V, co-founded by Fr. Dahm, sparked the creation of the Archdiocese of Chicago Domestic Violence Outreach (ACDVO) Network in 2011. As the Director of the ACDVO Network, Fr. Dahm has preached at more than 121 parishes throughout the Chicago area on the topic, in both Spanish and English. He has also trained and supported over 90 parishes in the Chicago area in establishing their own parish-based DV ministries. Fr. Dahm is a well-known and trusted advocate for family peace and the church’s role in achieving that goal (see Photo 2).

Photo 2.

Context 2: Parish leadership bold stance against intimate partner violence and abuse.

Photo credit: Chicago Sun-Times—permission for reprint obtained.

Observational data, reflective memos, and transcripts from archived video data indicate that his homilies/sermons on the topic of IPV/A were straightforward, research-based, and engaging, but also compassionate. The homilies invite people who have perpetrated or experienced violence and abuse to seek help. Indeed, two of the focus group participants cited the reason they sought help from TMG from hearing a sermon on DV that was given by “a St. Pius V priest”. As one participant stated

the priest from St. Pius went to my church …. And…when I heard the story of domestic violence, of abuse…I thought this is almost my life. So, then I, after the mass, I met with the priest and told him, ‘You were speaking almost [all] of my life. I’ve tried to change my life, but for some reason I haven’t been able to achieve that change.’ So that’s when he told me, ‘Go to St. Pius. There we can help you.’ So then, that’s why I went.

Tracing the Development of The Men’s Group

Rev. Charles W. Dahm, O.P. Ph.D. became pastor of St. Pius V parish in 1986. In April of 1996, he hired a social worker who found that DV was the most frequently noted and greatest concern of parishioners seeking assistance. In May of 1996, Fr. Dahm hired another social worker and began preaching about DV at St. Pius V. The social worker developed and led women’s survivor support groups as a first step to addressing the issue beyond building awareness through the homilies and individual counsel. By 1998 and 1999, women of the support group began to request that the church provide help for their children who had witnessed the abuse as well as service to help their male partners become non-violent. At the same time, the men themselves also began to request help for changing their behavior. As a result, in 2001, TMG at St. Pius V parish began with a focus on meeting this need.

Financial Sustainability

From the group’s inception, it was co-facilitated by a man/woman team. However, due to budgetary constraints, at times the group has operated with one facilitator instead of two. As of March 2017, TMG was maintained by one modest full-time staff salary position with a continued goal of establishing a second permanent facilitator. Free on-site childcare is provided to group participants in order to make it possible for them to attend group sessions. Although the total HOPE Program budget grew to nearly $500,000 annually, the scope of services offered and continuing efforts to improve services, means that identifying funding is always a priority. The primary sources of funding have historically included financial awards by the City of Chicago, the State of Illinois, private foundations, individual donors, and the parish. There is no fee for participants in TMG, but donations are accepted. At the end of every weekly group session, members collect donations amongst themselves to support continuation of the program. The anonymity of participant-donors and participant non-donors is maintained by placing donations on a chair. After group facilitators leave, a volunteer participant then collects and gives the donations to the facilitator(s).

Referral Sources

Interviews, focus groups and observational data all indicated that the HOPE program does not actively recruit participants to join TMG. Staff and clergy reported that members act as the primary referral source, sharing the perceived benefits with others who they think may find the group useful. This means sharing their experiences with friends, family, co-workers, or neighbors. Participants may also become aware of TMG through clergy, their family, those seeking other services of the HOPE program, or community based social workers who are aware of TMG.

Procedures

Staff reported that no written procedures were in place regarding the process in which members join TMG, rather staff operated on a shared set of known processes. The following procedures were developed by piecing together data collected during interviews and refined during member checking. Initial engagement usually begins with a potential participant calling program staff. Staff record general demographic information, conduct a brief phone screening, in which, staff ask questions about the caller’s perception of and behaviors in their intimate relationships. If staff think the client might benefit from TMG, they invite the client to attend a group session. Participants are required to be 18 or older (17 and under are referred for youth/children services in the HOPE program). TMG is essentially open to all Spanish speaking men. Staff did not recall ever rejecting a man from TMG or not extending an invitation. After attending one group session, an individual session with a group co-facilitator is typically scheduled and completed. This first individual session may be used to learn more about the client, conduct a more thorough assessment, discuss how the group would be beneficial for the participant, or serve as a general counseling session. If additional individual sessions are requested, a group co-facilitator provides those concurrently with weekly group sessions. TMG meets once a week for approximately 2 hr. The group is exclusively voluntary. Staff or volunteers do not supply any documentation of participation to the court on behalf of group members. Court mandated clients are not prohibited from attending the groups or receiving individual counseling, but court requirements must be met outside TMG by a court-approved program.

Attendance and Demographic Data. Attendance data from 2011 to 2015 (the most recent available) indicated that over 400 men have attended at least one session of TMG. Analysis revealed that the average weekly group size in 2015 was 23 men and the largest group size recorded was 43 men in 2012. Attendance data from these five years indicated that the average “length of stay” for a man was eight sessions (n = 399) with a minimum of one session and maximum of 74 sessions.

The 18 focus group participants in this study ranged in age from 33 to 48 years (M = 41, SD = 6.08), self-reported 100% Catholic and 100% Latino, Hispanic, or Mexican. Focus group participants and staff reported that not all members of TMG are Catholic or belong to a religious group. Not all group members live in or near Pilsen; some have traveled up to 2–3 hr each week (one-way driving distance) in order to participate in TMG.

The focus group participants self-reported length of membership/attendance to TMG ranged from three sessions to 8 years. Five participants completed 3-8 sessions, two participants completed 15-16 sessions, two participants had been attending group for 5-6 months, three participants had been attending for 1-2 years, two participants had been attending for four years, and three participants had been attending 6, 7, and 8 years respectively. Group members attendance and engagement was not bound to consecutive weeks of participation, rather participants were permitted to engage for periods of time continuously or take leaves of absence for periods and resume engagement at any time. For example, the average number of sessions attended across 2011–2015 was eight, but this did not mean that all sessions were attended consecutively or even within the same year. Some participants attend weekly, some bi-weekly or others attend as they deem necessary. There is no defined end of treatment within TMG, making engagement difficult to measure and evaluate.

Group Atmosphere, Content and Activities

Observational data served as the primary source for examining group atmosphere and activities. Soft instrumental music was played in the lobby of the building prior to designated group meeting times. During the beginning of group, meditative nature-like music was played. During group sessions, the first hour was usually dedicated to a check-in, in which new participants shared the story that led them to seek help from TMG. Established members could also use the first hour to share a situation on which they would like to receive group advice or feedback. Exchanges were not confrontational. Notably, participants and group facilitators rarely interrupted one another while speaking, allowing full expression of thoughts, emotions, and perspectives. The second hour was typically dedicated to providing education/information on various topics and included group discussion. The following list of topics were based on observational data and data obtained from document review:

| • Healthy Relationship Communication • Financial, Emotional, Psychological forms of abuse • Strategies and skills for Peaceful (Non-Violent) Living • Effects of Violence on Children • Cultural or Religious Acceptance of Violence Perpetration • Self-Esteem • Parenting • Machismo/Manhood/Traditional Sex Roles based on Gender Identity • Socio-political factors that impact household stress/Stress management |

• Effects of trauma on men • Power and Control • Partnership • Negotiation and Fairness • Support and Trust • Respect • Non-threatening behavior • Sexual Respect • Accountability and Honesty • Jealousy • Anger and control |

These topics are neither a prioritized nor an exhaustive list. Observational, interview and document review data indicated that topics are presented at the discretion of the co-facilitators and are based on participant discussion in the first hour or what women partners comment about in their support group (i.e., shouting, sexual abuse)5. Special topics could also be requested by members of TMG and integrated into sessions. For example, if participants desired to talk about “negotiating major life decisions” (i.e., a major move), then the facilitators followed through with leading discussion and presenting educational materials that have been developed over the years. There were often brief periods of silence throughout the session, in which participants were asked to pause and personally reflect upon topics or materials discussed during group. Dialogue, questions, and reflection were encouraged throughout the group session. There is no exact “end of treatment” or recommended number of sessions to “complete” the program. TMG is open, meaning that participants can join or re-join at any time, topics are repeated, and participants can remain as long as they wish. Facilitators also supplement material presented in group by suggesting additional resources such as books that can be reviewed outside of group sessions. A commonly suggested reading is The Knight in Rusty Armor, a short story chronicling the journey of a man “in search of his true self” (Fisher, 1987, p. 1).

Culturally Focused

Staff and administrators noted that the HOPE program was built in response to the demographic that initially sought and continued to seek help from the parish. The neighborhood is comprised primarily of Mexican immigrants, but TMG was designed to be sensitive to the unique needs of Latino men, regardless of ancestry. Staff estimated that at least 90% of participants identify as Mexican, however it was also noted that there are men in TMG with Puerto Rican, Caribbean, Central and South American heritage. TMG is facilitated in Spanish and accompanying educational resources (i.e., videos, books) are most often presented in Spanish. Some group members were monolingual (Spanish) and others were Bilingual (Spanish/English). The physical space also reflected the intention of serving Latinx families, as the building in which TMG meets was decorated with traditional Mexican artwork.

Furthermore, TMG content includes a focus on examining the positive and negative aspects of cultural traditions with which many participants identify (i.e., strong sense of responsibility to family and view of women as subordinate to men within machismo). On the other hand, one staff member noted that “not all Latinos are the same” and very careful attention is given to making sure that each participant is understood in their own right.

Spirituality Based

Sessions begin with a short prayer that is led by a volunteering group member. The prayer is followed by a moment of silence for meditation. The content of the prayer changes depending upon which man offers it. Based on observational data, the prayer was usually general in nature, giving thanks to God for the group and its members as a resource. One facilitator noted that “It’s not religion because I have people from different religions…. I’m always careful with that”-Admin/Staff A. Another staff member noted

We try not to make any religious formal stuff directly into the group to protect that everybody feels very welcome. It’s hard sometimes because there’s such a dominating…Christian presence [of] those physically in the room. And we don’t want it to dominate if someone’s not from a Christian perspective [so we] dance delicately with that. (Admin/Staff B).

Interview data indicated that religion and spiritual faith are incorporated in the group to the extent that participants initiate it.

If faith is brought up during the group discussion, [it is] free to talk about, in terms of how it impacts [a group member] or their relationship decisions. . .In the Latino community faith is very important. So, people come and talk about faith, and I never stop them. (Admin/Staff A)

Internal document review indicated that spirituality was incorporated into group through exploring the following topics: (1) Control of thoughts and actions; (2) Inner Harmony/Peace; (3) Superior Power concept (based on 12 steps philosophy) and (4) Repairing damages (based on 12 steps philosophy). Data revealed that religious related content was introduced in TMG by acknowledging sacred times of the year and through supplemental media that explored topics relevant to TMG. For example, one archived document (authored by a staff member) noted “During the year at some specific times of the liturgical calendar some topics related to participants’ religious practices are mentioned or connected to group life (i.e., Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter)”. This document noted that Christian movies like Fireproof (2008), Courageous (2011), and Cicatrices (Scars) (2005) which explore issues such as marital conflict, fatherhood and DV are used as supplemental resources. Similarly, Christian films like The Grace Card (2011) and The Good Lie (2014), which focus on personal growth in a broader sense are also noted as resources.

Socialization and Volunteerism Outside of Formal Group Sessions

Group facilitators encourage group members to support one another inside and outside of group sessions. At the end of each group an announcement is made that urges senior members to exchange contact information with new group members. One staff member noted:

It is very regular that there are leaders in the group who share their cell number with others and almost everyone has at least one other cell number of someone else in their group. There’s a lot of peer contact out of the group. So they reach out to one another for advice or to, to be another listener, to what they’re struggling with or they’re about to act or what they think they want to do or, for um, unhealthy behavior. (Admin/Staff B)

Peer contact is not limited to support in times of distress. For example, one Admin/Staff recounted a time in which discussions in group about gender roles helped participants realize that several of the men did not know how to cook because cooking was seen as an activity reserved for women. This revelation led to group participants independently deciding to meet up to experiment with recipes and learn how to cook. Others have supported each other in seeking additional supports such as attending Alcoholics Anonymous together. Other group members seek additional time to discuss books about IPV/A or attend meditation together. The nature of outside activity depends on the group members’ interests, therefore changing over time.

TMG participants are invited by facilitators or their peers to engage in a variety of service or community-building activities. For example, group participants have helped organize events that celebrate the international day of women and hosted events that raise community awareness about DV. As observed throughout the study, these activities occurred year-round. Observation data suggested that members of TMG who participated in these events were not concerned with possible stigma but were proud to be seen as members of TMG. Three events that participants of TMG played key roles in were selected to serve as examples (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Sample Events that The Men’s Group Participate in Outside of Weekly Group Sessions.

| Purpose | Organizers | Attendees | Men’s Group Role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event #1: The Annual Kermes (Jun. 3rd, 4th, 5th 2016) | An annual street festival, organized by the church, live music, dancing, games, food tents | St. Pius V Parish | [700+] Open to General Public: Police officers, Community members, parishioners, Group facilitators, Clergy, Children of all ages | Kitchen cleaning, outdoor sweeping. Participate as attendees. |

| Event #2: Community Educational Event (10/14/16) | Provide awareness about domestic violence, commitment to peaceful living | The Men’s Group | [40-50+] Open to General Public: Local health service providers, Clergy, Children of all ages | Give presentation to attendees about the elements needed for a healthy partnership. Participate as attendees. |

| Event #3: Dance/HOPE Program Fundraiser (2/10/17) | Formal banquet dinner, Live music, traditional Mexican band, dancing | HOPE Program Staff & Couples Group1 | [300+] Not open to general public (limited by invitation only): HOPE Program Service recipients, Family of service recipients, Donors, Clergy, Children of all ages | Sell tickets to family and friends in order to raise money for the program. Participate as attendees. |

See above footnote on “couples”. Interview data revealed that the HOPE program provides a couples group for those who have successfully sought help for domestic violence separately before being approved to join the couples group.

Treatment Modality and Goals

Staff and clergy reported that the main goals of TMG are for participants to become self-aware, stop violence/abuse, understand that violence is not a way to resolve relationship problems, and learn healthy ways of dealing with problems that may arise within intimate relationships. A facilitator reported drawing on the Duluth Model (Pence & Paymar, 1993) as a guiding curriculum, but the approach observed by the PI reflected an approach that integrated cognitive-behavioral (CBT), trauma-informed care, and motivational interviewing techniques. More differences from the Duluth model were observed in TMG than similarities. For example, TMG did not require participants to document abusive behaviors in a control log, focus extensively on the power and control wheel, nor sign a release of information. TMG did not follow a 28-week model of treatment like Duluth or cycle 3-week themes for topics (Pender, 2012). TMG explored a wide range of topics, adding the intersection of culture, spirituality and meditative strategies to enhance the curriculum and reflect participant needs. Given the innovative strategies for supplementing curricular content, particularly the programs opportunities for engagement with staff and peers beyond weekly meetings, TMG was found to be more than a Duluth derivative adapted for Latino men, and instead reflected a unique treatment modality that drew on a variety of treatment models.

RQ 2a: What motivated currently involved participants to initially attend TMG?

Regardless of original referral source, men identified a variety of motivations for initially joining the group. The following were reported by staff/administration/clergy and TMG participants as the most common reasons for joining the group:

- Fear of losing or actual loss of their partner or family due to their abusive actions/Pressure from a partner to get help:I have ten years married with my wife but in these ten years I had committed domestic violence…there was abuse from my part…I was also an alcoholic. And then there came a moment where my wife stopped me and she told me that everything was gonna end and I then started to look for help and that’s when an acquaintance told me that in Saint Pius, they offered a program that could maybe help me…that is how I started in the group. (Group member)

Acknowledging a problem and desiring to change for children, self, and others: “I went by myself, and it was because of the problems I had. I understand that by ourselves, we can’t make the change. We can’t do it alone. That’s why I went to the group, and I’m learning from them.” – Group member

- A desire to reach inner peace:I went to the group, the men’s group, because I couldn’t find peace anymore. I couldn’t find peace. I was desperate. There were fights in my house, fights with my kids. A lot of the time, I would be mad. I didn’t even know what I wanted, where I was or what I was doing. I worked harder [but] there wasn’t anything that could fill me inside so that’s what made me look for all of this. (Group member)

RQ 2b: Why do currently involved participants remain engaged in TMG?

Three primary themes emerged that shed light on understanding why men remain engaged after initially joining TMG. These themes were focused on respect, support, and learning and served as the basis for theory development related to retention.

Being Met with Dignity and Respect

One of the major themes raised by men related to continued involvement in TMG was the positive interaction with group facilitators. These interactions were perceived as being positive, thought provoking, and supportive:

What I like most is how my counselor responds to me…not in the way I want to hear, because if I wanted for him to respond with what I want to hear, well then, (laughs) I’m wasting my time there. He responds to me like a total professional. After he’s heard me, he has all the time and the patience. Sometimes I’ve extended myself with him two to three hours. He has a lot of patience. (Group member)

One staff member noted that it was important to allow incoming members enough space to vent relationship frustrations so that they would return to more group sessions and not be put off by a barrage of interruptions and challenges. This approach was confirmed through observations that revealed non-combative and respectful interactions with incoming group members. Participants reported that the respect they experienced from staff acknowledged their human dignity and worth. As one group member described it: “(You) are not just a number– (You) are treated like the person you are… You feel loved. You feel welcome. The warmth of group is what makes you overcome certain problems in life”

Administration and clergy highlighted that to meet group members with respect, intentionality was required. For example, facilitators encouraged participants to take leadership roles during sessions (i.e., transferring control of drafting a power point slide on discussion content to a group member rather than a co-facilitator). Acknowledging and highlighting the strengths/skills of group members seemed to build confidence and reinforce the value that each group member brought to TMG (whether new or established).

Photo 3.

HOPE Program Staff at “Domestic Violence Benefit Gala 2017 on the occasion of Fr. Charles Dahm’s 80th birthday”.

Permission to print photo obtained.

Establishment of Group Members as “Family”

Participants perceived that the relationships they experienced with other members were akin to a brotherhood, which facilitated recurring involvement with TMG. One group member explained it by stating: “When you enter there, you don’t find friends, you find a family with one that you know that you can count on in your worst times.” This brotherhood appeared predicated upon the accessibility that group members had to one another on an ongoing basis. One group member recounted the following:

When someone has a necessity to talk or is in crisis or needs help or a suggestion, there’s always a freedom of … I call you. ‘Do you have some time to talk? We can go for coffee. We could do it via phone.’ Almost always, there’s availability from one of us.. . . If it’s not one, it’s another, and we see each other outside of group…There does exist that support outside of group. That’s why my colleagues mention that we find almost like a brotherhood. We find another family.

This social support was also noted and encouraged by administrators and staff. As one staff member highlighted, “The group is not only every Wednesday…it’s 24 hours a day, and seven days a week” – Staff/Admin C. Furthermore, this support extended beyond the confines of discussing interpersonal or relationship issues. One group member highlighted such an example by sharing

Like today, I got here late, because I was helping one of the colleagues to move. He had a surgery, and he couldn’t, so his wife was the one doing most of the movement, so I went to help them, because …it came up (in group), and he asked if I can help him…

Gaining Benefits from the Program

Another major theme pertaining to prolong-engagement centered on the knowledge participants reported gaining from TMG.

I keep going to the group classes because the truth is, it changes the perspective of each one of us that’s here present, and I think they won’t let me lie. We don’t change from night to day, but I think this is something that we do step-by-step…the truth is it changes our lives. (Group member)

I went for my own need. Nobody obligated me or nothing, okay. I’ve been very comfortable there because there’s a lot of information. Videos, book recommendations, there’s a lot of information. That’s why it’s been working for me. (Group member)

Participants perceived the knowledge gained from TMG as being strongly connected to positive growth in their cognitive processing of disputes and resulting behavior.

There’s been a radical change in my life. I see life in a different way, I try to be with my family as well as I can. There’s more communication…more focus on the children and hopefully this message gets to the ears of more men with our problems. (Group member)

If I hadn’t gone to that place, I would be with problems…with civil problems, with the government, with the police….What I have learned in this place is that you gotta try to talk and to reason things with words and not with blows (Group member)

Learning and experiencing growth because of the group served as a reason that senior group members continued to participate even when their own needs for intervention might have subsided. In this case, mentoring with the intention of passing on knowledge and support was also a motivation for continuously returning to group.

For many participants, reasons for continued participation were not limited to one theme alone, but due to the combined effect of two or three themes. As one group member stated:

There came a point I had given up and I knew I needed help and so I looked, right? At that moment, my ex-mother-in-law told me about the group and that I could change…so I said, ‘Let’s see what the group can help me with’…Now, after two years, I’ve seen it’s a community of men where one helps the other and one can open oneself…without judgment, but they give us tools to help make our lives better and that’s why I’ve stayed in this group because I know that in this group, I have found more than help. I have found friends. I have found family. (Group member)

Theory Generated

The initial theoretical model built from this case study suggests that both respect experienced from program staff and social support experienced from group peers influence prolonged engagement amongst the men. Participants perceived benefits have a reciprocal relationship with their ongoing engagement in TMG. The proposed theoretical model, illustrated in Figure 1, fits well with the data in this study, which is a strong marker for its potential validity (Eisenhardt, 1989). Feeling respected by program staff was a prerequisite for incoming participants to build long-lasting relationships with other group members. Experienced respect was also a necessary factor in incoming members feeling comfortable enough to return to subsequent group sessions. Experiencing social support in the form of friendship or kinship facilitated connectedness to other group members. These relationships were reported as being essential to men making changes towards peaceful living.

The theoretical model is embedded in the mezzo/meso level environmental factors that surround the function of TMG. The relationship between the parish and the larger Pilsen community was strong, indicating a degree of mutual trust. The parish leadership also demonstrated a commitment to bringing awareness to the issue of IPV/A and advocated for an end to violence and abuse perpetration within families.

Discussion

This study examined functioning of the TMG at St. Pius V and factors associated with participants’ engagement in a voluntary PAIP. Understanding the nature and context of such a unique program can offer insight into reaching populations that perpetrate non-criminalized, yet harmful forms of abuse, through interventions that are supported, developed and led within their community. The first crucial element of such programming is strong community support. In the case of TMG, this community-level support is reflected in the parish’s relationship with the community and in parish leadership’s commitment to IPV/A advocacy. This community support may be similar to a coordinated community response, which has been identified as essential in a criminal justice system response to DV (Shepard & Pence, 1999). The theoretical model explaining current men’s engagement in TMG reveals both micro and mezzo/meso level factors that correspond with the socio-ecological framework on IPV/A (Heise, 1998) which integrates systems theory, feminist perspectives, and other theoretical views on IPV/A. These findings underscore the findings of previous research, indicating that community, group, and individual level factors collectively and independently contribute to PAIP participants behaviors within intimate relationships (Sheehan et al., 2012).

Our findings provide practitioners and researchers with a practical example of how a PAIP may tailor or design service to a particular population and introduce innovative strategies to foster therapeutic relationships between facilitators and group members. TMG functions by integrating group-based psycho-education, cognitive behavior therapy, individual counseling, techniques of motivational interviewing, trauma-informed care and techniques of the 12-step philosophy through a culturally focused and spirituality-based lens. This integration reflects recent calls for BIPs to move away from the traditional one-size-fits-all model and takes individual needs, such as stage of change into consideration (Kistenmacher & Weiss, 2008; Maiuro & Eberle, 2008; Musser et al., 2008). These findings are important because they offer a deeper understanding of the program activities while also shedding light on why currently involved participants remain engaged in TMG. Scholars have advocated for the creation of environments that allow men to openly share their experiences while learning from others in efforts to reduce IPV/A perpetration (Mancera et al., 2017). The findings in this study (related to why men stay engaged) provide evidentiary support to previously published theoretical considerations for enhancing retention and engagement. For example, using techniques familiar to motivational interviewing, such as speaking to clients in a way in which they feel heard and/or respected (Murphy & Maiuro, 2009) was reported to be a key factor in participants ongoing engagement.

The study identified positive peer support and staff respect towards participants as key elements for engagement of men (without court-mandates) into the program. The findings on peer support are consistent with extant literature suggestions for PAIP program enhancement, such as participants building relationships within and outside of the BIP as a reported factor facilitating behavior change (Sheehan et al., 2012). A unique element of TMG is the degree to which group members socialize and support one another outside of formal group sessions. Despite research suggesting that developing relationships within and outside of PAIPs may be a necessary predecessor in changing the behaviors of partner violent men (Sheehan et al., 2012), traditional practice has discouraged outside socialization in fear of possible collusion of members that could lead to problems like unchallenged victim blaming. Facilitators tend to have some degree of autonomy in PAIPs, which has resulted in reports of some programs establishing buddy systems amongst group members or encouraging former participants to mentor (sponsor) group members (Muldoon & Gary, 2011). While concerns about the possibility of sponsor-mentee collusion to encourage violence may deserve attention (Almeida & Bograd, 1991), the present study provides some empirical support for the potential benefits of positive peer relationships and contrast the traditional use of male peer social support theory, which focuses on the reinforcement of negative behaviors (DeKeseredy & Schwartz, 2013). It has been nearly 10 years since Barbara Hart (2009) suggested examining the power of positive male peer support within PAIPs as a mechanism towards reducing IPV/A, yet we are unaware of investigations exploring this potential program enhancement. In order to advance the field, differing approaches must be thoroughly documented and outcomes evaluated across populations to see if such controversial approaches like peer support may be a key component of successful programs.

Respect was a consistent theme reported by both participants and staff in regard to engagement and retention. Although the National Association of Social Workers highlight the importance of meeting clients with respect, irrespective of the issue in which they seek help, actual practice behaviors may differ (DiFranks, 2008). Specialized training may be needed to ensure the implementation of core social work principles when working with populations that may be perceived as deviant. Rapport building is a necessary skill in any direct practice setting, but without clients experiencing a fundamental sense of respect, treatment efforts may be substantially reduced if not removed entirely (Corvo & Johnson, 2003). Participants descriptions of experiencing respect may have been an expression of facilitators establishing and developing therapeutic bonds with participants, which scholars have argued is key to successful treatment for IPV perpetration (Taft et al., 2016).

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

The strengths of the study include contribution to the literature on partner abuse interventions via a case-study of a community based voluntary PAIP. Since such programs are usually mandatory, studies are needed to develop, implement and evaluate voluntary PAIP intervention programs with diverse groups in the US. A primary limitation of the study was that the PI did not speak fluent Spanish. To help combat this challenge, two bilingual RAs were hired to assist with translation, data collection, and analysis throughout the study. Additionally, the analysis of focus group data was conducted in English, after translation from Spanish. Information could have been lost during translation, therefore having multiple bilingual research team members present in focus groups and available to review translations helped to reduce errors related to language limitations. Due to the qualitative nature of this study, there was a risk of the PI imposing her own conceptual understanding onto the data. Sharing and discussing results with stakeholders as they unfolded helped to assure understanding, improve accuracy, and mitigate this concern.

Although the data collection period spanned nine months, the group itself has been in operation for over 15 years. If the study had taken place at a different point in the life of the program, results may have varied. For example, group observations for this study began shortly after the program relocated the meeting site. Although participants indicated there were no differences based on this change, without observing the group in the former setting, comparative observational data analysis was not possible. In addition, many of the established processes likely resulted from lessons learned at specific points in program development that could not be identified retrospectively. Similarly, it is not clear if participation and outcomes will remain constant. There is an increased role of the associate pastor in regional IPV/A efforts. The new senior pastor at St. Pius V has not yet demonstrated a strong commitment to supporting parish-affiliated domestic violence programming. Given the unique origins and focus of TMG, it is not clear how changes in leadership will impact sustainability. Given the scant extant literature on voluntary PAIPs and the even smaller literature specific to the population served (Emezue et al., 2019) this in-depth description may provide valuable insight to others seeking to evaluate or replicate the approach.

Focus group participants cannot be considered a random representation of Men’s Group members. Those who volunteered to participate in the focus groups may have differing opinions or experiences than those who did not elect to participate in this study or those who are not currently engaged in TMG. On the other hand, case studies by nature are designed and conducted for in-depth description rather than generalizability (Yin, 2003). The case study information triangulated well with the data that was kept by the program on attendance across the years—suggesting remarkable levels of engagement for a voluntary PAIP. However, the dosage of treatment that senior participants reported is ambiguous. It is unclear how well “years of engagement” correlates with the number of sessions attended and topics covered. Further, given the extended reach of group engagement and reports of learning from peers outside of formal sessions, further investigation is needed to understand if dosage of sessions has separate impact from interactions with the informal support network.

Despite the limitations, this study is a significant contribution to the field of PAIP. TMG at St. Pius V is one of a few known models that target voluntary participants in a culturally informed and/or spiritually sensitive manner. Because research has focused on traditional models provided for mandated clients, it is not clear how many models similar to TMG exist or how effective these are. While the current study advanced understanding the inner workings of the program and participant perceptions of TMG, it was not possible to assess effectiveness. It is important to examine behavioral outcomes with some type of comparison or control. Further, given that the proposed model was built within a specific community and institution upon requests from survivors and men who sought help without a court mandate, it is not known if similar engagement and retention results may be obtainable for different communities, institutions, cultural groups or mandated clients.

As a result of the current study and the general lack of research literature on voluntary PAIPs (especially within the United States), numerous questions were raised for future study. For example, even though buddy systems have been incorporated as a tool for socialization within some PAIPs (Faulkner et al., 1992), no testing to date has been done on the impact of peer socialization in improving outcomes with partner abusive men. Future work should examine if there is any association between improved outcomes of treatment and peer socialization outside of group or perceptions of peer connectivity. Additionally, research on PAIP participants’ perceptions of staff/facilitator respect for them are limited. Future research should examine how PAIP group members experience respect in the context of group treatment so that it can be tested as a potential contributing factor in participant outcomes. It is also unclear how and when spiritually or faith-based programming may enhance program participation or outcomes. Similarly, it is important for future research to examine how differences in program language of faith-engaged social services (i.e., faith-based vs. spirituality-based) might influence service provision or client perceptions of services. Given the widespread occurrence of IPV/A and the many criticisms of current approaches to PAIPs, it is imperative that intervention research in this area extend beyond traditional approaches to understand how to improve participation and outcomes. Additionally, it is unknown how similar or different the men served in this program are compared to a typical court-mandated population of men. There may or may not be differences in readiness to change, prior tactics of abuse perpetrated, severity of violence, substance abuse, mental health history, or other areas. A recent study in Canada compared the characteristics of court-mandated PAIP participants to non-court mandated men in a PAIP and found relatively few demographic differences and similar outcomes between the groups after treatment (Tutty et al., 2019). Future work is underway to further investigate differences/similarities between those in TMG and court-mandated participants of a traditional PAIP. Future research also will examine intervention outcomes longitudinally across the two groups. It is hoped that this article will encourage research on innovative and voluntary program approaches to intervening with men who have acted abusively against their intimate partner(s) so that society may effectively reduce the occurrence and impact of this important social issue.

Summary

Intimate partner violence perpetration is a significant social and public health problem. The name of the PAIP examined (The Men’s Group) is critically important to note, when considering the labeling of trauma-informed care for men who have engaged in violence or abuse within intimate (romantic-interest or sexual) relationships. Group structured PAIPs should be aware of the potential impact that positive male peer social support outside of group and perceived respect demonstrated by group facilitators may have on men’s engagement in PAIPs. It is speculated that these aspects when paired with group work could prove useful in efforts to engage and retain men in treatment. Our findings also indicated that mezzo/meso level factors such as parish leadership openly advocating against IPV/A and a strong community-parish relationship in general were key to building a community environment that promotes and sustains engagement in a voluntary spirituality-based PAIP.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Case_Study_Final_Spanish_Version_1_10_20_1 for The Men’s Group at St. Pius V: A Case Study of a Parish-Based Voluntary Partner Abuse Intervention Program by Maxine Davis, Melissa Jonson-Reid, Charles Dahm, Bruno Fernandez, Charles Stoops and Bushra Sabri in American Journal of Men’s Health

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the study participants, the HOPE program/Men’s Group at St. Pius V parish, the research assistants, and the many entities represented on the community collaborative board. To obtain a Spanish version of this publication please follow this link. The Spanish version was not peer-reviewed by the American Journal of Men’s Health; Para obtener una versión de esta publicación en Español, por favor, siga este vínculo:

Appendix

Appendix A.

Focus Group Questions/Script (English).

| I. Introduction Note—as participants are entering the room, the facilitator will: • Ask the participant to make a name tag with any first name the participant wants to use for today’s group Thank you all for coming to participate in this focus group. My name is __________. I will be facilitating this session. Next to me is ____. S/he will be helping me take notes for this session. II. Ground Rules Before we start, I wanted to review some basic group rules. We will be talking about some topics that may feel very personal. And so: • Please remember that you do not need to answer any questions that make you feel uncomfortable. If you become upset during the discussion, it is OK to step out of the room. Please try to stay nearby so that ____or I can go check to make sure you are OK. • Please try to respect others confidentiality. Please address people by the name they use today and have on their name tags. Although every precaution will be taken to safeguard your confidentiality, it cannot be guaranteed in a group setting. • Please respect that others may have different opinions and experiences than you. We are interested in hearing about ALL of your opinions. Feel free to express your disagreement with what others may say, but please try to do so in a respectful manner without putting down or discounting anyone. • You’ll notice we have tape recorders here. We are audio taping the discussions. This helps us to catch all that you say. You might find that at some point I need to ask one person to speak at a time, so that we can catch everything. • Are there any ground rules that you would like to add or is there anything else we can do as a group to make you feel safe and comfortable during the focus group? Before we begin, does anyone have any questions about the focus group process? III. Focus group questions: Let’s go around the room. Please tell us either your first name or a pseudo name for today, and an estimate of how many St. Pius “Men’s Group” sessions you have attended, or how long you have been going to The Men’s Group. [Signal non-verbally where you’d like the responses to start] (1) Why did you start going to the group? (2) What were the reasons you went to a church for this type of help? (3) You were not court mandated to attend the Men’s group, so what influenced you to keep returning? (4) What would need to occur to motivate more men to attend other groups like “The Men’s” Group”? (5) Is culture and faith incorporated into the Men’s Group? If so, how? (6) What are the things you like best about the program? (7) What would you change about the program? OK, we’re going to switch gears and little 1) What factors do you think can lead to a man to be abusive toward his partner? 2) Has faith or religion influenced you to stop abusive treatment of your partner?—If so how? 3) Were there times that you used faith or religion to control your partner?—If so how? 4) What are other important things about domestic violence would you like to talk about? We are getting close to the end of our discussion. I’m going to ask ________to give us a summary of the key issues you’ve talked about. Then we need to know from you— • Did we hear you right? • Did we leave anything out that you think we should put in? IV. Wrap up: Thank you again very much for participating in this group (this evening). If you have any questions for me or the researcher, feel free to contact us, using the information provided on your consent form. Additionally, we recognize that we have discussed some very sensitive topics today. If there is something that you need to discuss further please see your group facilitator. We also have a list of resources that may be helpful if desired. If there was anything else you wanted to share, but more privately, you may write it on a notecard and place it in this box. Thank you. |

Adapted from (Celaya-Alston, 2010).

Appendix B.

Brief Study Report.

Unlike spirituality’s more individualistic quest for meaning and connection to the sacred, religion is often distinguished as an organized, more formal system of worldwide views, behaviors and rituals used to assist one’s closeness to God (Koenig et al., 2001). Religion can be understood as an expression of faith, whereas spirituality can be understood as the personal experience of “the sacred and divine” (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006). Therefore, religion often involves spirituality; however, the reverse is not necessary.

Latinx is a gender inclusive term used by scholars and activists as part of a “linguistic revolution” in order to move beyond gender binaries. It is an alternative to Latino and Latina, when the gender identities of the population being described is unknown. Using the term Latinx acknowledges gender queer, gender non-conforming, and transgender people. In this article Latinx is used to describe national population and the residents of Pilsen, however Latino is used to describe members of the men’s group, because the group is exclusive to men only.