Abstract

The proper regulation of mRNA processing, localization, translation, and degradation occurs on mRNPs. However, the global principles of mRNP organization are poorly understood. We utilize the limited, but existing, information available to present a speculative synthesis of mRNP organization with the following key points. First, mRNPs form a compacted structure due to the inherent folding of RNA. Second, the ribosome is the principal mechanism by which mRNA regions are partially decompacted. Third, mRNPs are 50%–80% protein by weight, consistent with proteins modulating mRNP organization, but also suggesting the majority of mRNA sequences are not directly interacting with RNA-binding proteins. Finally, the ratio of mRNA-binding proteins to mRNAs is higher in the nucleus to allow effective RNA processing and limit the potential for nuclear RNA based aggregation. This synthesis of mRNP understanding provides a model for mRNP biogenesis, structure, and regulation with multiple implications.

INTRODUCTION

The biosynthesis and function of eukaryotic mRNAs is a complex process in which the mRNA interacts with a series of RNA processing, localization, translation, or degradative complexes. The interaction of the mRNA with these cellular machines is determined and regulated by a diverse set of RNA-binding proteins (RNA-BPs) that taken together make up assemblies referred to as mRNA–protein complexes, or mRNPs (Singh et al. 2015). The overall organization, dynamics, and architecture of mRNPs is poorly understood. In this essay, we consider mRNP structure from the perspective of how mRNAs fold, how ribosomes remodel mRNA structure and protein composition, and how the density of proteins on mRNAs impacts mRNP organization.

NONTRANSLATING mRNAS FORM COMPACTED STRUCTURES

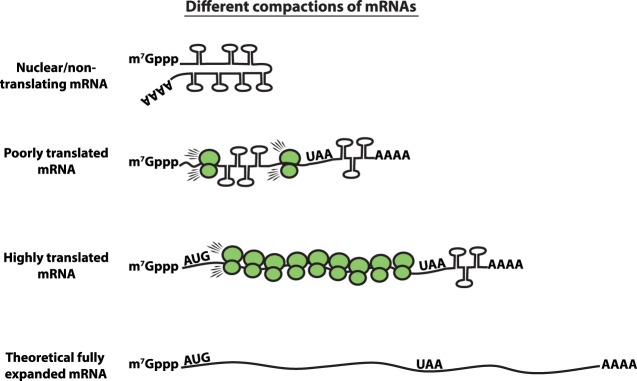

Several observations argue that mRNPs in vivo form compacted structures, particularly when not engaged in translation (Fig. 1). This was first suggested by the EM analysis of the Balbiani long mRNA (37 kb) in dipteran Chironomus tentans, which forms a dense 50 nm mRNP particle resulting in a ∼200-fold compaction of the mRNA relative to its linear length when it is fully extended and unstructured (Wurtz et al. 1990a). Similarly, EM analysis of nuclear pretranslational mRNPs isolated from yeast shows these mRNPs are also compacted by at least ∼15-fold (Batisse et al. 2009). More recently, single-molecule FISH (smFISH) analysis using probes to different regions of mammalian long mRNAs in the cytosol or nucleus demonstrates they are similarly compacted by ∼40–55-fold when they are not translated (Adivarahan et al. 2018; Khong and Parker 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the different levels of compaction of mRNAs. (i) Nuclear and nontranslating mRNAs represent the most compact form. (ii) Ribosomes decompact the mRNA by unfolding the mRNA. (iii) mRNAs that are more engaged in translation (more ribosomes loaded) are more decompact than mRNAs that are not as well translated. (iv) Finally, the theoretical fully expanded mRNA.

Two observations argue that the compaction of mRNPs seen in cells is driven primarily by the inherent tendency of RNA to fold. First, a wide variety of RNAs in vitro, including various mRNAs, are observed to fold into compact structures. For example, on average, the Ef2 and RpoB mRNAs are compacted more than 50-fold compared to their linear lengths in vitro as analyzed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (Borodavka et al. 2016). Similarly, RNA compaction on shorter RNAs (975–2777) showed an approximately six- to 12-fold compaction compared to their linear lengths as visualized by Cryo-EM (Gopal et al. 2012). In addition, genome-wide structural probing studies demonstrate nontranslating mRNAs in vivo have extensive RNA secondary structures that resemble RNA secondary structures in vitro (Rouskin et al. 2014; Beaudoin et al. 2018).

Some observations suggest that the inherent folding of RNA may contribute to the formation of the “closed-loop” nature of mRNPs. For example, the ends of purified mRNAs folded in vitro are close (<10 nm) in solution (Fang et al. 2011; Yoffe et al. 2011; Clote et al. 2012; Leija-Martínez et al. 2014; Lai et al. 2018). This distance is significantly smaller than the overall size of the mRNA when compacted. This inherent RNA structure may provide a closed-loop arrangement of RNA molecules that proteins have evolved to bind and utilize for mRNA regulation. One example would be the protein–protein interactions between the cap-binding complex (eIF4F) and the poly(A) tail binding protein (PABP), which can modulate translation initiation and mRNA decapping.

RIBOSOMES DECOMPACT mRNPS

Several lines of evidence argue that ribosomes decompact mRNAs. This was first suggested by the strong helicase activity of elongating ribosomes (Takyar et al. 2005). In addition, analysis of mammalian mRNP compaction by smFISH has revealed that translating mRNPs are more extended than nontranslating mRNAs (Adivarahan et al. 2018; Khong and Parker 2018). The degree of mRNA compaction is due to ribosomes loaded on the mRNAs since the compaction of the translating mRNP is inversely correlated with the number of ribosomes loaded on the message (Adivarahan et al. 2018), and when ribosomes run-off the mRNA following inhibition of translation initiation, the 5′ portion of the mRNA compacts before the 3′ region (Adivarahan et al. 2018; Khong and Parker 2018). Since the compaction of translating mRNPs is not affected by inhibition of translation elongation (Khong and Parker 2018), it suggests even stalled ribosomes on the ORF are sufficient to decompact the mRNA.

A second line of evidence that ribosomes decompact mRNA secondary structure comes from genome-wide structure probing in zebrafish wherein translating mRNAs contain fewer CDS secondary structures than nontranslating mRNAs (Beaudoin et al. 2018). Similarly, a neural network study that combines numerous ribosome density studies and structural probing studies suggests that ribosome density plays a strong role in disassembling mRNA secondary structures (Yu et al. 2019). Therefore, ribosomes are decompacting mRNPs, and one should anticipate a range of mRNP compaction with a nontranslating mRNP being most compacted and with translating mRNAs being more extended in a manner proportional to ribosome density (Fig. 1).

An important point is that translating mRNPs are still compacted relative to its contour length (Adivarahan et al. 2018; Khong and Parker 2018). The simplest model of this compaction is due to the formation of secondary structures of mRNA sequences between elongating ribosomes, which is supported by the spacing of ribosomes on mRNAs. For example, translatome-wide studies suggest one ribosome is found per 156 and 183 CDS nucleotides, which is ∼1/5 and ∼1/6 of the maximal packing density in yeast and mammalian cells (Arava et al. 2003; Hendrickson et al. 2009). Moreover, single-molecule translation studies suggest the average inter-ribosome distance is between 200–2000 nt on mammalian reporter mRNAs (Morisaki et al. 2016; Pichon et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2016). Since a ribosome footprint is ∼30 nt (Steitz 1969; Wolin and Walter 1988), this argues that the majority (∼80%–99%) of the mRNA is not coated with ribosomes. This suggests that translating mRNAs will likely compact by secondary structure formation between elongating ribosomes (Fig. 1). Since spontaneous intramolecular RNA folding can be very fast, in hundreds of microseconds (Gralla and Crothers 1973; Pörschke 1974), whereas eukaryotic translation elongation is slower at approximately every 50–350 msec/nt (Boehlke and Friesen 1975; Ingolia et al. 2011; Morisaki et al. 2016; Pichon et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2016), one anticipates that mRNA sequences between ribosomes will collapse into RNA secondary structures, which are continuously unwound by each elongating ribosome (Fig. 1).

The unwinding of local RNA structure by ribosomes may couple initiation and elongation rates. Specifically, since secondary structures can slow down ribosome translocation speed (Somogyi et al. 1993; Wen et al. 2008; Qu et al. 2011; Tholstrup et al. 2012; Charneski and Hurst 2013; Chen et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2014), subsequent ribosomes transiting behind an initial ribosome may exhibit faster elongation rates as long as the trailing ribosomes are close enough to the first ribosome to limit extensive secondary structure formation. Supporting this idea, two studies suggest faster translation initiation rates correlate with faster translation elongation rates (Arava et al. 2005; Riba et al. 2019). A similar phenomenon has been suggested for mRNAs with extensive secondary structures where subsequent ribosomes catch up with the first ribosome resulting in increased mRNA decompaction and more efficient elongation (Tuller et al. 2010; Zur and Tuller 2012; Mao et al. 2014).

IS THE CLOSED-LOOP ARCHITECTURE SPECIFIC FOR NONTRANSLATING mRNPS?

An unresolved issue is whether the closed-loop model of mRNP structure can form on translating, nontranslating, or both types of mRNAs. The closed-loop model of mRNPs is the concept that the 5′ and 3′ ends of mRNAs interact through protein–protein interactions to regulate translation and mRNA degradation (Kahvejian et al. 2001; Jackson et al. 2010; Hinnebusch 2014). This model is based on two major types of observations. First, that 3′ regulatory elements, including the poly(A) tail, can affect 5′ events such as translation initiation and mRNA decapping (Jacobson and Favreau 1983; Gallie 1991; Muhlrad et al. 1994). Second, that the 3′ poly(A) tail binding protein (PAB1) interacts with the eIF4G component of the cap-binding complex suggesting a possible direct physical link between the 5′ and 3′ ends (Tarun and Sachs 1996; Wells et al. 1998).

The analysis of long mRNAs by smFISH suggests that the closed-loop architecture, in some cases, may be limited to nontranslating mRNAs. The key observation is that for multiple long mRNAs (AHNAK, DYNC1H1, MDN1, PRPF8, and POLA1), the 5′ and 3′ ends of the mRNA are generally too far apart when the mRNAs are engaged in translation for the closed-loop to form, although the ends are found in proximity when the mRNAs exit translation (Adivarahan et al. 2018; Khong and Parker 2018). Thus, in some cases when mRNAs are engaged in translation, they are not in a closed-loop formation.

In contrast, EM analysis of polysomes in cells can reveal circular or hairpin polysome arrangements where the 5′ and 3′ ends are in proximity when the mRNAs are engaged in translation (Palade 1955; Warner et al. 1962; Wettstein et al. 1963; Christensen et al. 1987; Shelton and Kuff 1996; Christensen and Bourne 1999; Yazaki et al. 2000). Moreover, genome-wide methods utilizing proximity ligation reveal RNA–RNA interactions between the 5′ and 3′ ends, indicating the ends can interact, although it is not clear if these are in translating or nontranslating mRNPs (Sugimoto et al. 2015; Aw et al. 2016; Lu et al. 2016; Ziv et al. 2018). One possibility is that the formation of the closed-loop architecture during translation is specific to certain types of mRNAs or occurs in a dynamic nature. An important issue in future work will be exploring how closed-loop architecture is dynamically regulated and specific to some translating mRNAs and thus, how closed loops interactions can modulate mRNA function.

HOW DO mRNAS FOLD?

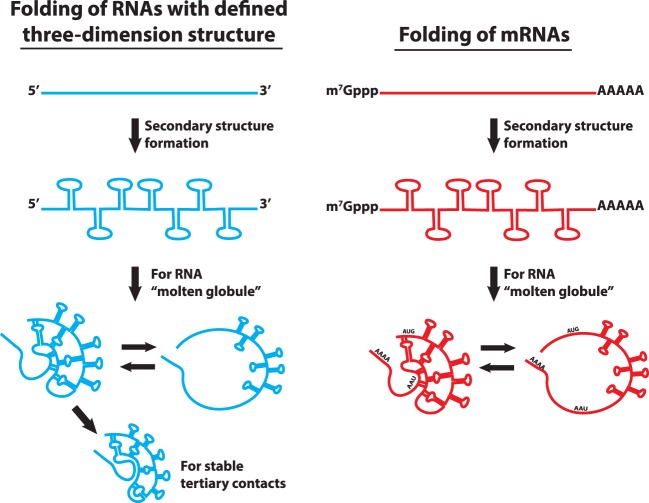

As nascent mRNAs are extruded from RNA polymerase, they will form secondary structures. One unresolved issue is whether a given mRNA will have a defined 3D structure analogous to the folding of a functional ncRNA (e.g., rRNA, tRNA, catalytic RNAs) in which specific tertiary interactions stabilize interactions in a defined manner between secondary structure elements (Herschlag et al. 2018). In the absence of defined tertiary interactions, we should expect mRNAs to form a collapsed state of RNA secondary structures similar to an RNA “molten globule” that is observed as a folding intermediate in the folding of catalytic RNAs (Fig. 2; Russell et al. 2002). Given that the estimated density of nucleotides in folded mRNAs is less dense that rRNA (we estimate a ribosome as 0.84 bases/nm3, nuclear balbani ring mRNP as 0.56 bases/nm3), the simplest hypothesis is that mRNAs will form extensive secondary structure, but fail to form a fully defined unique 3D fold. However, local regions of mRNAs, such as regions of the 3′-UTR, can clearly form defined tertiary folds with functional consequences (Berry et al. 1991; Badis et al. 2004; Jambor et al. 2014). One anticipates the possibility that mRNAs with unique biological roles, such as localizing to specific regions of the cell, may have a more fully defined tertiary structure, which should be revealed by evolutionary conservation of both secondary and tertiary RNA interactions.

FIGURE 2.

Stepwise ncRNA folding versus mRNA folding. RNA has a propensity to fold into secondary structures rapidly forming a “molten globule” state. Functional ncRNAs which have defined tertiary interactions, enable further compaction into specific structures. In contrast, mRNA lacking defined tertiary interactions stays in a “molten globule” state.

A second unresolved issue of mRNA folding is how diverse the patterns of secondary structure are even for a single mRNA sequence. RNAs are well known to form multiple conformers when refolded in vitro. For example, structural probing studies indicate a single mRNA sequence adopts multiple conformations in vitro due to the extensive existence of both single-stranded and double-stranded reads at the individual nucleotide level (Kertesz et al. 2010; Wan et al. 2014; Kaushik et al. 2018). Similarly, ssRNAs often adopt many different structures in vitro as assessed by using cryo-EM, 3D reconstruction of SAXS form factors, and MD simulations (Gopal et al. 2012). Moreover, mRNAs are predicted to form multiple conformations with very similar minimum free energy (Yoffe et al. 2008). These in vitro experiments suggest that mRNAs are expected to form a diverse array of conformers based on stochastic events in RNA folding.

One key difference for mRNA folding in the cell as compared to in vitro is that folding will occur in a 5′ to 3′ direction as the RNA is extruded from RNA polymerase or the ribosome. This raises the possibility that directional information, and/or the binding of RNP-BP, might lead to a more limited, or unique, set of RNA folding patterns. However, structure probing of nontranslating mRNAs in cells, which would be influenced by directional folding, and refolded mRNAs in vitro, which refold as a full-length RNA, argues they have a similar set of variable structures (Rouskin et al. 2014; Beaudoin et al. 2018). Consistent with that view, computational analysis of intramolecular cross-links in RNA molecules suggests that mRNAs have a less consistent structure that other RNAs with defined folds, such as rRNA, snoRNAs, and snRNAs (Yu et al. 2019). This leads one to argue that directional folding of RNA, imposed as the RNA is extruded from the polymerase or from elongating ribosomes, or the binding of RNA-BP, does not generally make a large impact on the overall fold of mRNAs, although it could in some cases be significant.

Taken together, one anticipates that mRNA structure will be made up of three components when just considering the RNA. First, mRNAs will form an extensive secondary structure due to the inherent folding of RNA sequences. Second, due to stochastic events in RNA folding, mRNAs, in general, will form multiple RNA conformers, which can have alternative fates (e.g., alternative splicing). Third, some local secondary and tertiary structures in mRNAs will be functional and will be evolutionarily conserved. Finally, the folding of mRNAs in some cases will be influenced by the binding of RNP-BP, including the ATP dependent binding of DEAD/DExH box proteins. Work on determining the diversity of mRNA folding patterns, how those generally are affected by protein binding, will be of future interest.

HOW MANY PROTEINS ARE BOUND TO INDIVIDUAL mRNAS?

In the cell, RNA folding and the overall organization of mRNPs may be influenced by RNA-BPs. In order to understand mRNP organization in cells, and how proteins influence mRNPs, one starting point is to consider how much protein is bound to mRNAs, and how that might change during the mRNA life cycle.

Numerous studies have identified hundreds of proteins that reproducibly cross-link to eukaryotic mRNAs, collectively referred to as the RNA-BP proteome (Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012; Mitchell et al. 2013; Bao et al. 2018; Queiroz et al. 2019; Trendel et al. 2019; Urdaneta et al. 2019). Based on these cross-linking experiments, current estimates suggest that over 1000 proteins in human cells can bind to mRNAs. This gives the impression that mRNAs are coated with a myriad of proteins, although there is little actual data about how many molecules of protein are bound to an individual mRNA molecule.

Two recent studies estimate the degree with which mRNAs are bound to proteins in the nucleus or in the entire cell by RNase-mediated protein footprint sequencing (Silverman et al. 2014; Gosai et al. 2015). They suggest on average each mRNA molecule contains ∼16 protein-protected fragments in HeLa cells and ∼13 protein-protected fragments in Arabidopsis nuclei. Given that on average mRNA in mammalian cells (MW ∼ 1000 kilodaltons) weighs twenty times more than the average proteins (MW ∼ 55 kDa), this translates to a range of protein to RNA composition for mRNPs between ∼40%–50% protein to ∼50%–60% RNA. These studies do not distinguish translating versus nontranslating mRNPs, which might vary in the RNP-BP composition.

Another way to estimate the number of RNA-BPs associated with an mRNA is to determine the buoyant density of mRNPs in CsCl2 gradients, which is a function of the relative mass of protein and RNA in a particle (Perry and Kelley 1966). For example, analysis of the nuclear form of the 37 kb Balbiani ring mRNP indicates this mRNP is 60% protein/40% RNA (Wurtz et al. 1990b). This approximates to one 50 kDa protein per 100 bases of mRNA. Additional analysis suggests that the average density of hnRNPs is between 1.3–1.5 gm/cm3 (Wurtz et al. 1990b), suggesting a range of protein to RNA composition for nuclear mRNPs from 80% protein to 50% protein. Although these are crude estimates based on limited data, it is reassuring that the numbers are more or less in line with the RNase-mediated protein footprint studies.

One can estimate what such mRNP compositions would suggest for mRNAs of different sizes (Supplemental Table S1). For example, for an “average” human mRNA of 3000 bases, 50% protein composition would imply ∼1,000,000 g/mole of protein /mRNA, whereas 80% protein composition by mass would imply ∼4,000,000 g/mole of protein/mRNA. A typical cytoplasmic mRNP would be expected to have ∼500 kDa of protein-bound from just the eIF4F complex and two molecules of the poly(A) binding protein on the 3′ poly(A) tail. This implies that since most cytoplasmic mRNAs have ∼500,000 kDa of protein from these core mRNP complexes, short mRNAs will have a higher ratio of protein to mRNA simply by this “ubiquitous” complex. In contrast, longer mRNPs will have their ratio of protein to RNA more heavily influenced by proteins binding to coding and 3′-UTR regions.

Given a range of protein/mRNA, one can also estimate the number of RNA-BPs associated with an mRNA, and therefore the amount of RNA sequence that is covered by protein (Supplemental Table S1A,B). While this is a very rough calculation and will vary depending on the assumptions made for the average size of an RNA-BP and the number of nucleotides covered by the average RNA-BP, these estimates suggest that between 3.3% to a maximum of 50% of an mRNA will be coated with proteins.

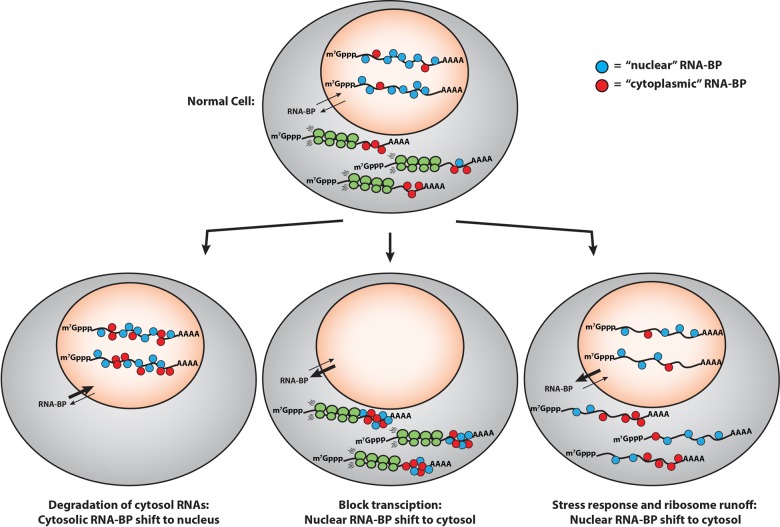

An important implication of these buoyant density experiments and RNase-mediated footprint assays is some RNA sequences in an mRNA are not coated with proteins. For example, if we use the estimate of 80% protein/20% mRNA, which is the highest amount of protein on nuclear mRNPs from CsCl2 sedimentation (Wurtz et al. 1990b), estimate the average size of RNA-BP as 50 kDa, and assume each RNA-BP covers 10 bases of RNA, then ∼23%–25% of an mRNA will be coated with protein (Supplemental Table S1A,B). Since the ratio of RNA-BP to RNA is higher in the nucleus than in the cytosol (see Supplemental Table S2; Fig. 3), this suggests an upper limit for how many proteins are binding to an mRNA, with significantly less mRNA coated with proteins in the cytosol. Regions of mRNAs that are not coated by proteins have the potential to interact in trans, thus contributing to the formation of large RNP granules (Van Treeck and Parker 2018).

FIGURE 3.

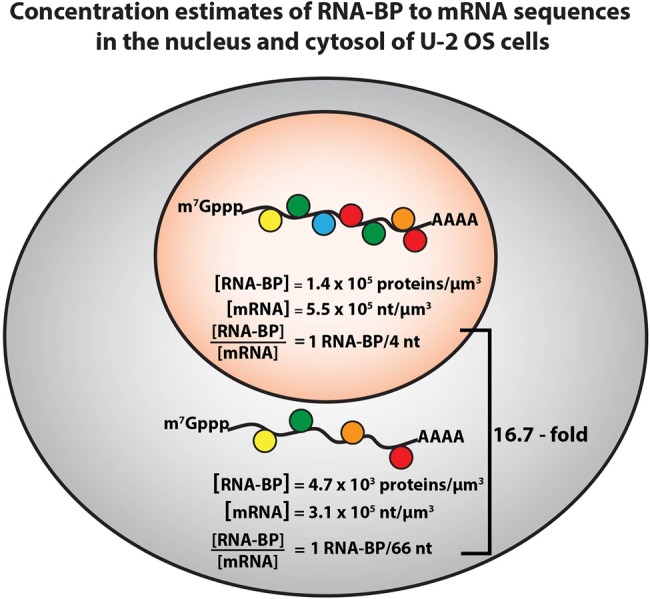

Estimates of mRNA and RNA-BP concentrations in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The estimates are derived from analyzing a number of data sets (Alberts 2002; Beck et al. 2011; Wühr et al. 2015; Piovesan et al. 2016; Khong et al. 2017) (see Supplemental Calculation #1). RNA-BPs are estimated to be ∼30-fold more concentrated in the nucleus than in the cytosol in U-2 OS cells. mRNA (in terms of RNA nucleotides) is ∼1.8-fold more concentrated in the nucleus than in the cytosol. Therefore, the ratio of RNA-BPs to mRNA sequences is higher in the nucleus than the cytoplasm (∼16.7-fold more RNA-BPs per nucleotide).

RNA-BINDING PROTEINS ARE AT HIGHER CONCENTRATIONS IN THE NUCLEUS

Since the biogenesis of nuclear mRNA requires mRNA processing, and there are no ribosomes to occupy the coding region in the nucleus, we speculated that the nucleus might have a higher concentration of RNA-BPs than the cytosol. Increased RNA-BPs in the nucleus would then function to bind nascent RNA, facilitate RNA processing, and prevent intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions that might otherwise trigger nuclear RNA aggregation (Van Treeck and Parker 2018). To this end, we estimated the concentration of RNA and RNA-BPs in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.

We estimated the relative concentrations of RNA-binding proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm based on quantitative mass spectrometry in U-2 OS cells (Beck et al. 2011), and the known localization of RNA-BPs (Supplemental Table S2; Wühr et al. 2015). Strikingly, there is a clear bias for abundant RNA-BPs to be enriched in the nucleus. For example, 94 of the 110 most abundant RNA-BPs in U-2 OS cells are predominantly nuclear (Supplemental Table S2). Summing up the molecules of RNA-BPs (top 110), we estimate ∼140,000 RNA-BPs/µm3 are in the nucleus and ∼4700 RNA-BPs/µm3 in the cytosol (See Supplemental Calculation # 1). Although these are very crude estimates, and we do not account for effective accessible cytoplasm and nucleus, these calculations demonstrate RNA-BPs are significantly more concentrated in the nucleus than the cytosol by a substantial factor (∼30-fold).

THE RATIO OF RNA-BP TO RNA IS HIGHER IN THE NUCLEUS THAN CYTOSOL

We can also estimate the concentration of mRNA in the nucleus as compared to the cytosol. These estimates are based on (i) the average human mature mRNA being 3392 bases (Piovesan et al. 2016), (ii) the average human precursor mRNA being 66,700 bases (Piovesan et al. 2016), (iii) the number of pre-mRNAs present in the nucleus at any one time is 1% of the cytoplasmic pool of mature mRNAs, and (iv) U-2 OS cells have ∼330,000 mRNAs in the cytoplasm (Khong et al. 2017). This calculation estimates that there are 1.12 × 109 nt of cytosolic mRNA or ∼3.1 × 105 nt/µm3 in the cytosol, and 2.2 × 108 nucleotides of nuclear pre-mRNA, or ∼5.5 × 105 nt/µm3 in the nucleus (for methods of calculations see Supplemental Calculation #1). Thus, the concentration of pre-mRNA in terms of RNA nucleotides is ∼1.8 times higher in the nucleus than the cytosol (Fig. 3).

This analysis suggests that the ratio of RNA-BPs to mRNA sequences is higher in the nucleus by a factor of ∼16.7-fold with more RNA-BPs per RNA sequences in the nucleus (Fig. 3). A simple explanation for this difference between the cytosol and the nucleus is that the large size of introns and complex RNA processing reactions that occur in the nucleus requires a large number of RNA-BP to bind the pre-mRNA and orchestrate RNA processing. In addition, given the tendency of RNA to form intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions (Van Treeck and Parker 2018), the higher concentration of nuclear RNA-BP may be important to bind RNA sequences and limit intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions, which would otherwise lead to the formation of nuclear RNA granules that would hinder RNA processing and function.

The lower concentration of RNA-BP per RNA sequence in the cytosol makes sense since there are fewer nucleotides per RNA molecule, and over 50% of the average human mRNA is the coding region, which is limited in stable RNA-BPs interactions due to the process of translation elongation displacing proteins bound to the ORF. Thus, fewer RNA-BPs are needed in the cytosol. This also provides a rationale for why mRNAs form stress granules through intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions when the vast majority of mRNAs exit translation during stress response (Khong et al. 2017; Van Treeck and Parker 2018; Van Treeck et al. 2018). There are simply not sufficient RNA-BPs in the cytosol to limit intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions triggering RNA condensation.

The broader implications from this analysis, limited as it is to these rough estimates, is that the ratio of RNA-BP/mRNA is higher in the nucleus and then decreases in the cytosol. This implies that the highest density of proteins bound to mRNAs occurs in the nucleus and then decreases in the cytosol. When mRNAs exit translation, they reveal the ORF region as naked RNA, which can either be coated with proteins, form extensive secondary structures which compact the RNA, and/or form intermolecular interactions that drive RNA–RNA aggregation and lead to the formation of stress granules.

COMBINING RNA FOLDING AND PROTEIN COMPOSITION: WHAT DO mRNPS LOOK LIKE?

Taken together, we propose a model for nontranslating mRNP structure with the following key points. First, whenever possible, the mRNA will fold in cis to compact the RNA into a folded structure. Second, since mRNAs are generally not coated with RNA-BP, and since the relative size of a protein on average is 10 times smaller than an mRNA, we expect the protein binding would then minimally affect RNA structure. Moreover, since mRNA folding in vitro correlates with nontranslating mRNP architecture in terms of compactness, shape, and the close proximity of the 5′ and 3′ ends, we suggest the intrinsic property of mRNA folding is largely driving nontranslating mRNP architecture.

One can make two speculations on how mRNA-binding proteins will interact with mRNAs. First, we speculate that RNA-BPs will predominantly decorate the surface of the mRNA core RNA structure, not unlike the architecture of other well-known RNP assemblies (ribosome, spliceosome, and telomerase) where RNA is central to the assemblies. Second, we speculate that intrinsically disordered regions of RNA-BPs that bind RNA (Castello et al. 2016) may intertwine into the RNA secondary and stabilize the overall mRNA secondary structure. This latter possibility is based on the observation that many similar tails of ribosomal proteins intertwine into the secondary structure elements of the ribosome and stabilize the overall fold.

BINDING SITES FOR RNA-BINDING PROTEINS AND THEIR DYNAMIC DISTRIBUTIONS

Several observations lead us to suggest that the distribution of RNA-BP between the nucleus and cytoplasm will be influenced by the availability of binding sites on RNA molecules (Fig. 4). Supporting this idea, many RNA-BPs are known to shuttle between the nucleus and cytosol, thus allowing those proteins, in principle, to interact with either cytosolic or nuclear mRNAs (Piñol-Roma and Dreyfuss 1992). In addition, when nuclear RNA concentration is reduced by blocking transcription, many RNA-BPs accumulate in the cytosol (Hamilton et al. 1997). Moreover, when cytoplasmic mRNAs are widely degraded by the action of RNase L or viral nucleases, many RNA-BPs show increased accumulation in the nucleus (Clyde and Glaunsinger 2010; Gilbertson et al. 2018; Burke et al. 2019). Finally, when cells undergo a stress response and ribosomes run-off of mRNAs exposing the ORF RNA, a number of nuclear RNA-BPs show increased distribution in the cytosol (Kedersha et al. 1999).

FIGURE 4.

The shuttling of RNA-BPs between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is highly dependent on mRNA concentration in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. (i) When mRNAs in the cytoplasm are degraded by viral ribonucleases or RNase L, a rapid accumulation of cytoplasmic RNA-BPs in the nucleus has been observed (Clyde and Glaunsinger 2010; Gilbertson et al. 2018; Burke et al. 2019). (ii) Similarly, when transcription is blocked, many nuclear RNA-BPs accumulate in the cytoplasm (Hamilton et al. 1997). (iii) Finally, when ribosomes run-off mRNAs due to cellular stress and expose the ORF, several nuclear RNA-BPs move to the cytosol (Kedersha et al. 1999).

Taken together, this suggests a model whereby the distribution of RNA-BPs is influenced by the presence of RNA-binding substrates. Binding to RNA would be expected to affect both the rate of export from the nucleus since mRNA export can carry along with proteins bound to the mRNA. Similarly, binding to cytoplasmic mRNAs would limit the reimport of RNA-BPs into the nucleus.

The redistribution of RNA-BPs between the nucleus and cytosol can impact gene expression in multiple ways. First, in cases where there is an increase in available cytosolic RNA, such as a stress response or defects in mRNA turnover, some nuclear RNA-BPs will redistribute to the cytosol, which decreases the concentration in the nucleus. A decrease in nuclear RNA-BPs would be expected to alter RNA processing, which might occur in multiple manners. For example, the well-described decrease in 3′ end processing and polyadenylation of mRNAs could be due to decreased concentration of nuclear RNA-BPs that modulate 3′ end processing (Vilborg and Steitz 2017). Conversely, the accumulation of TDP-43 in the cytosol and its corresponding depletion from the nucleus can expose cryptic polyadenylation sites that were normally blocked by TDP-43 binding, thereby allowing premature 3′ end processing and polyadenylation (Melamed et al. 2019). In another example, the inhibition of transcription can lead to the accumulation of numerous RNA-BP in the cytosol, some of which compete with RNA decay factors leading to the stabilization of cytosolic mRNAs (Brennan and Steitz 2001), thus maintaining mRNA levels despite the decreased transcription rate.

mRNP ORGANIZATION AND INTERMOLECULAR INTERACTIONS OF mRNPS

An interesting question is how this view of mRNP architecture impacts the interactions of mRNPs with RNP processing and translation machines. In this section, we consider how this view of mRNP organization would ripple through the biology of mRNA biogenesis and function.

Impact on mRNA synthesis and RNA processing

As mRNAs are being synthesized and emerging from the RNA polymerase, they will fold into secondary structures. In the absence of any input, the mRNA would fully fold by extrusion from RNA polymerase. However, during extrusion, mRNAs are beginning to be bound by RNA-BPs and snRNAs for splicing. Indeed, the optimal time to recognize a binding site in an mRNA is immediately after extrusion from the polymerase since it is single-stranded and optimally presented for recognition by small RNAs or proteins. The principle of mRNA folding and then competing for recognition with trans-acting factors provides a biophysical basis for cotranscriptional splicing, where the snRNAs recognize the mRNA during extrusion. Note that one can utilize RNA-BP to modulate mRNA folding and allow certain regions to stay accessible for later recognition. This provides a mechanistic view for all the various RNA-BP that bind precursors and modulate alternative splicing. One also has to consider the possibility that cells utilize a variety of RNA unfolding machines to allow for rearrangements in RNA structure that prevent elements from being completely hidden from recognition.

Entry and exit of translation

We anticipate two ways mRNP folding will influence the interaction with ribosomes. A nontranslating mRNP will be assembled into a structure that is essentially the size of the 40S ribosome. To get the multifactor complex (MFC) to load on an mRNA, the 5′ UTR will need to be accessible. The current model is that the 5′ end will be bound by either nuclear cap-binding complex or eIF4F, and this will recruit eIF4A or Ded1/DDX3, which would then unwind the 5′UTR. An alternative view is that the role of eIF4A is to extract the 5′ end of the mRNA from the overall mRNA structure, thereby allowing for assembly of Ded1/Ddx3 and cis unwinding of the 5′ UTR to allow MFC loading (Yourik et al. 2017). In contrast, since the 3′-UTR is more structured that the coding region (in zebrafish, fruit flies, worm, and humans) (Li et al. 2012; Wan et al. 2014; Beaudoin et al. 2018), RNA structures in the 3′UTR may help terminate translation by stalling ribosomes at the stop codon.

General effects on recognition of regulatory sites in mRNAs

There appears to be a conundrum created by the local folding of mRNA in that such folding will limit the ability of important sites to be recognized in trans. In principle, there are several mechanisms to ensure efficient recognition of regulatory sites in mRNAs in the face of mRNA folding. First, sites can be recognized during synthesis as they emerge from RNA polymerase II. Second, RNAs can evolve structures and/or local RNA-BPs that load early and dictate the RNA structure in a manner that ensures recognition of a key regulatory site. Finally, cells may utilize RNA helicases to keep RNA structure in mRNAs dynamics and thereby allow for the reexamination of the sequence space by trans-acting components.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Olke C. Uhlenbeck (University of Colorado Boulder) and Daniel Herschlag (Stanford) for providing ideas and feedback on the manuscript and Anne Webb for assembling the figures. This work was supported by Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (A.K.) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.P.).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.073601.119.

REFERENCES

- Adivarahan S, Livingston N, Nicholson B, Rahman S, Wu B, Rissland OS, Zenklusen D. 2018. Spatial organization of single mRNPs at different stages of the gene expression pathway. Mol Cell 72: 727–738.e725. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B. 2002. Molecular biology of the cell. Garland Science, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Arava Y, Wang Y, Storey JD, Liu CL, Brown PO, Herschlag D. 2003. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 3889–3894. 10.1073/pnas.0635171100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arava Y, Boas FE, Brown PO, Herschlag D. 2005. Dissecting eukaryotic translation and its control by ribosome density mapping. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 2421–2432. 10.1093/nar/gki331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw JG, Shen Y, Wilm A, Sun M, Lim XN, Boon KL, Tapsin S, Chan YS, Tan CP, Sim AY, et al. 2016. In vivo mapping of eukaryotic RNA interactomes reveals principles of higher-order organization and regulation. Mol Cell 62: 603–617. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badis G, Saveanu C, Fromont-Racine M, Jacquier A. 2004. Targeted mRNA degradation by deadenylation-independent decapping. Mol Cell 15: 5–15. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhäusser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, Youngs N, Penfold-Brown D, Drew K, Milek M, et al. 2012. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 46: 674–690. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Guo X, Yin M, Tariq M, Lai Y, Kanwal S, Zhou J, Li N, Lv Y, Pulido-Quetglas C, et al. 2018. Capturing the interactome of newly transcribed RNA. Nat Methods 15: 213–220. 10.1038/nmeth.4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batisse J, Batisse C, Budd A, Böttcher B, Hurt E. 2009. Purification of nuclear poly(A)-binding protein Nab2 reveals association with the yeast transcriptome and a messenger ribonucleoprotein core structure. J Biol Chem 284: 34911–34917. 10.1074/jbc.M109.062034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin JD, Novoa EM, Vejnar CE, Yartseva V, Takacs CM, Kellis M, Giraldez AJ. 2018. Analyses of mRNA structure dynamics identify embryonic gene regulatory programs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25: 677–686. 10.1038/s41594-018-0091-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Schmidt A, Malmstroem J, Claassen M, Ori A, Szymborska A, Herzog F, Rinner O, Ellenberg J, Aebersold R. 2011. The quantitative proteome of a human cell line. Mol Syst Biol 7: 549 10.1038/msb.2011.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MJ, Banu L, Chen YY, Mandel SJ, Kieffer JD, Harney JW, Larsen PR. 1991. Recognition of UGA as a selenocysteine codon in type I deiodinase requires sequences in the 3′ untranslated region. Nature 353: 273–276. 10.1038/353273a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlke KW, Friesen JD. 1975. Cellular content of ribonucleic acid and protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a function of exponential growth rate: calculation of the apparent peptide chain elongation rate. J Bacteriol 121: 429–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodavka A, Singaram SW, Stockley PG, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A, Tuma R. 2016. Sizes of long RNA molecules are determined by the branching patterns of their secondary structures. Biophys J 111: 2077–2085. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CM, Steitz JA. 2001. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 266–277. 10.1007/PL00000854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Moon SL, Matheny T, Parker R. 2019. RNase L reprograms translation by widespread mRNA turnover escaped by antiviral mRNAs. Mol Cell 75: 1203–1217.e1205. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, et al. 2012. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149: 1393–1406. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A, Fischer B, Frese CK, Horos R, Alleaume AM, Foehr S, Curk T, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW. 2016. Comprehensive identification of RNA-binding domains in human cells. Mol Cell 63: 696–710. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charneski CA, Hurst LD. 2013. Positively charged residues are the major determinants of ribosomal velocity. PLoS Biol 11: e1001508 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Zhang H, Broitman SL, Reiche M, Farrell I, Cooperman BS, Goldman YE. 2013. Dynamics of translation by single ribosomes through mRNA secondary structures. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 582–588. 10.1038/nsmb.2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AK, Bourne CM. 1999. Shape of large bound polysomes in cultured fibroblasts and thyroid epithelial cells. Anat Rec 255: 116–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AK, Kahn LE, Bourne CM. 1987. Circular polysomes predominate on the rough endoplasmic reticulum of somatotropes and mammotropes in the rat anterior pituitary. Am J Anat 178: 1–10. 10.1002/aja.1001780102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clote P, Ponty Y, Steyaert JM. 2012. Expected distance between terminal nucleotides of RNA secondary structures. J Math Biol 65: 581–599. 10.1007/s00285-011-0467-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyde K, Glaunsinger BA. 2010. Getting the message direct manipulation of host mRNA accumulation during gammaherpesvirus lytic infection. Adv Virus Res 78: 1–42. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385032-4.00001-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang LT, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. 2011. The size of RNA as an ideal branched polymer. J Chem Phys 135: 155105 10.1063/1.3652763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR. 1991. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev 5: 2108–2116. 10.1101/gad.5.11.2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson S, Federspiel JD, Hartenian E, Cristea IM, Glaunsinger B. 2018. Changes in mRNA abundance drive shuttling of RNA binding proteins, linking cytoplasmic RNA degradation to transcription. Elife 7: e37663 10.7554/eLife.37663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal A, Zhou ZH, Knobler CM, Gelbart WM. 2012. Visualizing large RNA molecules in solution. RNA 18: 284–299. 10.1261/rna.027557.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosai SJ, Foley SW, Wang D, Silverman IM, Selamoglu N, Nelson AD, Beilstein MA, Daldal F, Deal RB, Gregory BD. 2015. Global analysis of the RNA-protein interaction and RNA secondary structure landscapes of the Arabidopsis nucleus. Mol Cell 57: 376–388. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralla J, Crothers DM. 1973. Free energy of imperfect nucleic acid helices. II. Small hairpin loops. J Mol Biol 73: 497–511. 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90096-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BJ, Burns CM, Nichols RC, Rigby WF. 1997. Modulation of AUUUA response element binding by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 in human T lymphocytes. The roles of cytoplasmic location, transcription, and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 272: 28732–28741. 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson DG, Hogan DJ, McCullough HL, Myers JW, Herschlag D, Ferrell JE, Brown PO. 2009. Concordant regulation of translation and mRNA abundance for hundreds of targets of a human microRNA. PLoS Biol 7: e1000238 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag D, Bonilla S, Bisaria N. 2018. The story of RNA folding, as told in epochs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10: a032433 10.1101/cshperspect.a032433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. 2014. The scanning mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu Rev Biochem 83: 779–812. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. 2011. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 147: 789–802. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. 2010. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 113–127. 10.1038/nrm2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A, Favreau M. 1983. Possible involvement of poly(A) in protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res 11: 6353–6368. 10.1093/nar/11.18.6353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambor H, Mueller S, Bullock SL, Ephrussi A. 2014. A stem–loop structure directs oskar mRNA to microtubule minus ends. RNA 20: 429–439. 10.1261/rna.041566.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahvejian A, Roy G, Sonenberg N. 2001. The mRNA closed-loop model: the function of PABP and PABP-interacting proteins in mRNA translation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 66: 293–300. 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik K, Sivadas A, Vellarikkal SK, Verma A, Jayarajan R, Pandey S, Sethi T, Maiti S, Scaria V, Sivasubbu S. 2018. RNA secondary structure profiling in zebrafish reveals unique regulatory features. BMC Genomics 19: 147 10.1186/s12864-018-4497-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. 1999. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2α to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol 147: 1431–1442. 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz M, Wan Y, Mazor E, Rinn JL, Nutter RC, Chang HY, Segal E. 2010. Genome-wide measurement of RNA secondary structure in yeast. Nature 467: 103–107. 10.1038/nature09322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khong A, Parker R. 2018. mRNP architecture in translating and stress conditions reveals an ordered pathway of mRNP compaction. J Cell Biol 217: 4124–4140. 10.1083/jcb.201806183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khong A, Matheny T, Jain S, Mitchell SF, Wheeler JR, Parker R. 2017. The stress granule transcriptome reveals principles of mRNA accumulation in stress granules. Mol Cell 68: 808–820.e805. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WC, Kayedkhordeh M, Cornell EV, Farah E, Bellaousov S, Rietmeijer R, Salsi E, Mathews DH, Ermolenko DN. 2018. mRNAs and lncRNAs intrinsically form secondary structures with short end-to-end distances. Nat Commun 9: 4328 10.1038/s41467-018-06792-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leija-Martínez N, Casas-Flores S, Cadena-Nava RD, Roca JA, Mendez-Cabañas JA, Gomez E, Ruiz-Garcia J. 2014. The separation between the 5′–3′ ends in long RNA molecules is short and nearly constant. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 13963–13968. 10.1093/nar/gku1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zheng Q, Ryvkin P, Dragomir I, Desai Y, Aiyer S, Valladares O, Yang J, Bambina S, Sabin LR, et al. 2012. Global analysis of RNA secondary structure in two metazoans. Cell Rep 1: 69–82. 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Zhang QC, Lee B, Flynn RA, Smith MA, Robinson JT, Davidovich C, Gooding AR, Goodrich KJ, Mattick JS, et al. 2016. RNA duplex map in living cells reveals higher-order transcriptome structure. Cell 165: 1267–1279. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Liu H, Liu Y, Tao S. 2014. Deciphering the rules by which dynamics of mRNA secondary structure affect translation efficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 4813–4822. 10.1093/nar/gku159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed Z, López-Erauskin J, Baughn MW, Zhang O, Drenner K, Sun Y, Freyermuth F, McMahon MA, Beccari MS, Artates JW, et al. 2019. Premature polyadenylation-mediated loss of stathmin-2 is a hallmark of TDP-43-dependent neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 22: 180–190. 10.1038/s41593-018-0293-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SF, Jain S, She M, Parker R. 2013. Global analysis of yeast mRNPs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 127–133. 10.1038/nsmb.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisaki T, Lyon K, DeLuca KF, DeLuca JG, English BP, Zhang Z, Lavis LD, Grimm JB, Viswanathan S, Looger LL, et al. 2016. Real-time quantification of single RNA translation dynamics in living cells. Science 352: 1425–1429. 10.1126/science.aaf0899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad D, Decker CJ, Parker R. 1994. Deadenylation of the unstable mRNA encoded by the yeast MFA2 gene leads to decapping followed by 5′→3′ digestion of the transcript. Genes Dev 8: 855–866. 10.1101/gad.8.7.855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade GE. 1955. A small particulate component of the cytoplasm. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1: 59–68. 10.1083/jcb.1.1.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RP, Kelley DE. 1966. Buoyant densities of cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein particles of mammalian cells: distinctive character of ribosome subunits and the rapidly labeled components. J Mol Biol 16: 255–268. 10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80171-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon X, Bastide A, Safieddine A, Chouaib R, Samacoits A, Basyuk E, Peter M, Mueller F, Bertrand E. 2016. Visualization of single endogenous polysomes reveals the dynamics of translation in live human cells. J Cell Biol 214: 769–781. 10.1083/jcb.201605024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñol-Roma S, Dreyfuss G. 1992. Shuttling of pre-mRNA binding proteins between nucleus and cytoplasm. Nature 355: 730–732. 10.1038/355730a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovesan A, Caracausi M, Antonaros F, Pelleri MC, Vitale L. 2016. GeneBase 1.1: a tool to summarize data from NCBI gene datasets and its application to an update of human gene statistics. Database (Oxford) 2016: baw153 10.1093/database/baw153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pörschke D. 1974. Thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of an oligonucleotide hairpin helix. Biophys Chem 1: 381–386. 10.1016/0301-4622(74)85008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Wen JD, Lancaster L, Noller HF, Bustamante C, Tinoco I. 2011. The ribosome uses two active mechanisms to unwind messenger RNA during translation. Nature 475: 118–121. 10.1038/nature10126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz RML, Smith T, Villanueva E, Marti-Solano M, Monti M, Pizzinga M, Mirea DM, Ramakrishna M, Harvey RF, Dezi V, et al. 2019. Comprehensive identification of RNA-protein interactions in any organism using orthogonal organic phase separation (OOPS). Nat Biotechnol 37: 169–178. 10.1038/s41587-018-0001-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riba A, Di Nanni N, Mittal N, Arhné E, Schmidt A, Zavolan M. 2019. Protein synthesis rates and ribosome occupancies reveal determinants of translation elongation rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116: 15023–15032. 10.1073/pnas.1817299116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouskin S, Zubradt M, Washietl S, Kellis M, Weissman JS. 2014. Genome-wide probing of RNA structure reveals active unfolding of mRNA structures in vivo. Nature 505: 701–705. 10.1038/nature12894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Millett IS, Tate MW, Kwok LW, Nakatani B, Gruner SM, Mochrie SG, Pande V, Doniach S, Herschlag D, et al. 2002. Rapid compaction during RNA folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 4266–4271. 10.1073/pnas.072589599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton E, Kuff EL. 1996. Substructure and configuration of ribosomes isolated from mammalian cells. J Mol Biol 22: 23–24. 10.1016/0022-2836(66)90177-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman IM, Li F, Alexander A, Goff L, Trapnell C, Rinn JL, Gregory BD. 2014. RNase-mediated protein footprint sequencing reveals protein-binding sites throughout the human transcriptome. Genome Biol 15: R3 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Pratt G, Yeo GW, Moore MJ. 2015. The clothes make the mRNA: past and present trends in mRNP fashion. Annu Rev Biochem 84: 325–354. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-080111-092106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Jenner AJ, Brierley I, Inglis SC. 1993. Ribosomal pausing during translation of an RNA pseudoknot. Mol Cell Biol 13: 6931–6940. 10.1128/MCB.13.11.6931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz JA. 1969. Polypeptide chain initiation: nucleotide sequences of the three ribosomal binding sites in bacteriophage R17 RNA. Nature 224: 957–964. 10.1038/224957a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Vigilante A, Darbo E, Zirra A, Militti C, D'Ambrogio A, Luscombe NM, Ule J. 2015. hiCLIP reveals the in vivo atlas of mRNA secondary structures recognized by Staufen 1. Nature 519: 491–494. 10.1038/nature14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takyar S, Hickerson RP, Noller HF. 2005. mRNA helicase activity of the ribosome. Cell 120: 49–58. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Sachs AB. 1996. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J 15: 7168–7177. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01108.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholstrup J, Oddershede LB, Sørensen MA. 2012. mRNA pseudoknot structures can act as ribosomal roadblocks. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 303–313. 10.1093/nar/gkr686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendel J, Schwarzl T, Horos R, Prakash A, Bateman A, Hentze MW, Krijgsveld J. 2019. The human RNA-binding proteome and its dynamics during translational arrest. Cell 176: 391–403.e319. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuller T, Waldman YY, Kupiec M, Ruppin E. 2010. Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 3645–3650. 10.1073/pnas.0909910107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urdaneta EC, Vieira-Vieira CH, Hick T, Wessels HH, Figini D, Moschall R, Medenbach J, Ohler U, Granneman S, Selbach M, et al. 2019. Purification of cross-linked RNA-protein complexes by phenol-toluol extraction. Nat Commun 10: 990 10.1038/s41467-019-08942-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Treeck B, Parker R. 2018. Emerging roles for intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions in RNP assemblies. Cell 174: 791–802. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Treeck B, Protter DSW, Matheny T, Khong A, Link CD, Parker R. 2018. RNA self-assembly contributes to stress granule formation and defining the stress granule transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115: 2734–2739. 10.1073/pnas.1800038115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilborg A, Steitz JA. 2017. Readthrough transcription: how are DoGs made and what do they do? RNA Biol 14: 632–636. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1149680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Qu K, Zhang QC, Flynn RA, Manor O, Ouyang Z, Zhang J, Spitale RC, Snyder MP, Segal E, et al. 2014. Landscape and variation of RNA secondary structure across the human transcriptome. Nature 505: 706–709. 10.1038/nature12946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Han B, Zhou R, Zhuang X. 2016. Real-time imaging of translation on single mRNA transcripts in live cells. Cell 165: 990–1001. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner JR, Rich A, Hall CE. 1962. Electron microscope studies of ribosomal clusters synthesizing hemoglobin. Science 138: 1399–1403. 10.1126/science.138.3548.1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB. 1998. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell 2: 135–140. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80122-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen JD, Lancaster L, Hodges C, Zeri AC, Yoshimura SH, Noller HF, Bustamante C, Tinoco I. 2008. Following translation by single ribosomes one codon at a time. Nature 452: 598–603. 10.1038/nature06716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein FO, Staehelin T, Noll H. 1963. Ribosomal aggregate engaged in protein synthesis: characterization of the ergosome. Nature 197: 430–435. 10.1038/197430a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SL, Walter P. 1988. Ribosome pausing and stacking during translation of a eukaryotic mRNA. EMBO J 7: 3559–3569. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03233.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Eliscovich C, Yoon YJ, Singer RH. 2016. Translation dynamics of single mRNAs in live cells and neurons. Science 352: 1430–1435. 10.1126/science.aaf1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr M, Güttler T, Peshkin L, McAlister GC, Sonnett M, Ishihara K, Groen AC, Presler M, Erickson BK, Mitchison TJ, et al. 2015. The nuclear proteome of a vertebrate. Curr Biol 25: 2663–2671. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz T, Lönnroth A, Daneholt B. 1990a. Biochemical characterization of Balbiani ring premessenger RNP particles. Mol Biol Rep 14: 95–96. 10.1007/BF00360431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz T, Lönnroth A, Daneholt B. 1990b. Higher order structure of Balbiani ring premessenger RNP particles depends on certain RNase A sensitive sites. J Mol Biol 215: 93–101. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80098-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Hoek TA, Vale RD, Tanenbaum ME. 2016. Dynamics of translation of single mRNA molecules in vivo. Cell 165: 976–989. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JR, Chen X, Zhang J. 2014. Codon-by-codon modulation of translational speed and accuracy via mRNA folding. PLoS Biol 12: e1001910 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki K, Yoshida T, Wakiyama M, Miura K. 2000. Polysomes of eukaryotic cells observed by electron microscopy. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 49: 663–668. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jmicro.a023856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe AM, Prinsen P, Gopal A, Knobler CM, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. 2008. Predicting the sizes of large RNA molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 16153–16158. 10.1073/pnas.0808089105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe AM, Prinsen P, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. 2011. The ends of a large RNA molecule are necessarily close. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 292–299. 10.1093/nar/gkq642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yourik P, Aitken CE, Zhou F, Gupta N, Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR. 2017. Yeast eIF4A enhances recruitment of mRNAs regardless of their structural complexity. Elife 6: 31476 10.7554/eLife.31476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Meng W, Mao Y, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Tao S. 2019. Deciphering the rules of mRNA structure differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in vivo and in vitro with deep neural networks. RNA Biol 16: 1044–1054. 10.1080/15476286.2019.1612692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv O, Gabryelska MM, Lun ATL, Gebert LFR, Sheu-Gruttadauria J, Meredith LW, Liu ZY, Kwok CK, Qin CF, MacRae IJ, et al. 2018. COMRADES determines in vivo RNA structures and interactions. Nat Methods 15: 785–788. 10.1038/s41592-018-0121-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zur H, Tuller T. 2012. Strong association between mRNA folding strength and protein abundance in S. cerevisiae. EMBO Rep 13: 272–277. 10.1038/embor.2011.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]