Abstract

Purpose

To identify and to describe patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in lung cancer patients and to evaluate the feasibility and utility of PROs into surveillance strategies, a review was carried out.

Patients and Methods

A systematic search in bibliographic databases evaluating the instruments used in PROs of non-small-Cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients was done.

Results

From August 2014 to August 2019, 33 studies were included in this review and 16,491 patients were evaluated. PROs were divided into 6 different categories: 1) PROs as a guide in therapeutic choice, 2) PROs as indicator of disease progression, 3) agreement between PROs and the evaluated parameters, 4) PROs to evaluate the effects of immunotherapy, 5) need to deepen the knowledge of PROs, and 6) use of new electronic PROs.

Conclusion

The most frequently used instruments are EORTC QLQ-30 (16, 50%) and EORTC LC-13 (14, 43.75%) and in some studies (37.5%) they are used together. For different reasons (disease progression, adverse event, death, incomplete participation, etc.), the completion of these instruments decreased over time from baseline to subsequent measurements. This review demonstrates that PROs can play an important role as part of health care, and that routine use implementation could improve patient management in addition to the traditionally collected outcome.

Keywords: quality of life, lung cancer, patient-reported outcomes, PROs

Introduction

Lung cancer still has a particularly poor prognosis: 60-month survival ranges are between 68% in patients with stage I disease, to 0–10% in stage IV patients. It is the leading cause of cancer deaths in Western countries.1,2 Due to its symptom-free course, lung cancer is often diagnosed in an advanced stage and the most frequent and clinically relevant disease-related symptoms experienced by patients in an advanced stage are pain, fatigue, dyspnea, and cough, with a significant impact on the health-related quality of life (HR QoL).3,4 It must be emphasized that patients with advanced/metastatic lung cancer during the course of the disease develop devastating physical and psychosocial symptoms, though new target therapies and immunotherapies are changing the situation of advanced/metastatic lung-cancer patients, improving disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).5 However, old and new therapies for metastatic lung cancer show adverse effects that can worsen the quality of life and worsen the prognosis if not promptly diagnosed and treated. Some studies reported that incorporating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) into surveillance strategies for advanced lung cancers appears to improve both quality of life and outcome in patients with advanced/metastatic lung cancer.6 Therefore, to analyze the role of PROs in the management of patients with advanced/metastatic lung cancer, we performed a review regarding feasibility and utility of incorporating patient-reported outcomes into surveillance strategies for advanced lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

A systematic search in the bibliographic databases, PubMed, Cochrane Library and EMBASE to identify all relevant publications was performed. In accordance with the guideline Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA),7 the latest database search was conducted on 19 Aug 2019 using the following search terms: “reported outcomes” AND “advanced lung cancer” with the restricted publication date “last 5 years”. For each study, data about authors, year of publication, type of study, number of patients included, treatment, instruments were used to asses QoL and timing for data collection were extracted. Only prospective observational studies, randomized-controlled trials and a post-hoc analysis are reported in this review. Two authors (LC and CC) independently evaluated the paper for the potential eligibility in this systematic review based on the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved by consensus with the third author. We cannot evaluate utility and feasibility of PROs directly, using a parameter common to all PROs, so we reported them evaluating clinical applicability but also the limits.

Instruments Utilized in the Reviewed Studies

In the articles analyzed, a total of 21 different PROs were described focused on different dimensions of the QoL (ie functional, physical, emotional and social function). The quality-of-life instruments evaluated can be categorized in general (ESAS), cancer-specific (EORTC QLQ-C30, RALS, PMC, FACT - G, SF-36, PRO-CTCAE, MDASI), lung-cancer-specific (EORTC LC-13, LCSS, FACT - L, LCS, NSCLC-SAQ, MDASI-LC), specific symptoms (FACT- F and SCFS for fatigue, FAACT and PG-SGA for Anorexia/Cachexia/nutrition and EAT-10 and SWAL-QoL for dysphagia), specific for Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAIGH) and instruments to evaluate the caregivers’ burdens (ZBI).

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)8 is a standardized cancer-specific instrument for measuring HRQL and symptom and functional domains consisting of 30 items, with subscales related to physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning, global health status/quality of life, symptoms and financial issues. Scores are reported on a scale of 0–100.

The EORTC Lung Cancer-13 (EORTC LC-13)9 is a standardized instrument that measures lung-cancer-specific symptoms (dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis and site-specific pain), chemotherapy/radiotherapy-related side effects and medication use for pain. Scores are reported on a scale of 0–100.

The Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS)10,11 is a standardized instrument for measuring lung cancer symptoms and HRQL; it evaluates different symptoms (pain, loss of appetite, fatigue, cough, dyspnea and hemoptysis) and general effects related to QoL. Each item is measured using a visual analogue scale, with scores reported on a scale of 0–100.

The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) and lung cancer module of the MDASI (MDASI-LC)12,13 is a multi-symptom patient-reported outcome measurement for clinical and research use. It includes symptoms found to have the highest frequency and/or severity in patients with various cancers and treatment types. The MDASI-LC is specific for lung cancer. It includes coughing.

The Rotterdam Activity Level Scale (RALS) of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL)14 was developed to measure the symptoms reported by cancer patients participating in clinical trials but it is also applicable to monitoring the levels of the patient’s anxiety and depression, and reflects the presence of psychological illness.

The Patients’ symptoms via the Patient Care Monitor (PCM) v2.015–17 is a review of system surveys with different lengths depending on gender. Each question is scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10. This instrument has been validated and demonstrates a significant correlation with other validated instruments.

The FACT measurement system includes FACT - G Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General, FACT - L Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung Cancer, FACT - F Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Fatigue, FAACT Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment.18–20 Since 1987 the FACT measurement system has been developed; FACT - G was developed to measure QoL in cancer patients receiving therapy. Now it is also a well-established instrument in cancer-related treatment evaluations and clinical interventions. To this questionnaire, problems that are specific to a particular type of cancer can be added. The FACT - L questionnaire asks about symptoms reported by lung cancer patients which may affect their quality of life. The FACT - F questionnaire assessing fatigue and anemia-related concerns in people with cancer; the FAACT uses an anorexia-cachexia subscale as a marker of QoL in patients with advanced lung cancer and cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome.

The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)21,22 is a generic questionnaire that generates eight subscale scores with values from 0 to 100. It can be used to evaluate the physical and mental condition of the patient.

The Lung Cancer Subscale (LCS) of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung (FACT - L)23,24 is an independently validated tool to assess symptoms of lung cancer. The maximum score is 28; lower scores represent more severe symptoms.

The Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale (SCFS)25 is a reliable and valid patient-reported measure of fatigue severity with a 5-point scale to generate a score ranging from 6 to 30.

The Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA)26 is a highly sensitive and specific screening tool to identify the need for nutritional intervention in patients with cancer; data produce 3 categories: well-nourished, moderately malnourished and severely malnourished.

The Patient-Reported Outcomes version of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE)27 is a validated PRO measurement system developed by the US NCI to assess symptoms possibly related to cancer treatments. PRO-CTCAE items are listed in publicly available libraries and cover 78 symptoms, each item reflects specific symptom attributes included in the corresponding CTCAE.

The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10)28 is used to obtain a self-reported prevalence estimate for both oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia in the samples.

The Swallowing Quality of Life instrument SWAL-QoL is used to measure the impact of dysphagia on QoL.29

The Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC-SAQ)30 is a 7-item PRO measurement for use in advanced NSCLC. It uses a 7-day recall period and verbal rating scale.

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment: General Health (WPAI: GH)31 is a validated, non-disease-specific tool and consists of items about work (employment status, hours missed from work, etc.) used to give four data: work time missed; impairment while working; overall work impairment; and activity impairment.

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI)32 is a validated scale that measures feelings of the burdens of caregivers for patients with a range of medical and psychological conditions.

The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS)33 consists of 9 common symptoms that patients rate on an 11-point scale, from 0 to 10: pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, inappetence, malaise and dyspnea.

Results

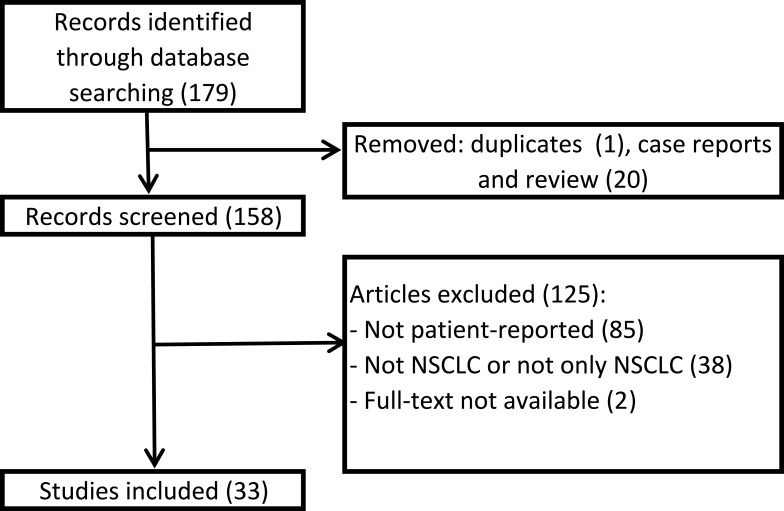

The search yielded a total of 179 articles (Figure 1). After removing duplicates and case reports, 21 were excluded. We screened 158 articles and 126 were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria: 84 used instruments not patient-reported, 39 included patients suffering from different types of cancer, not lung cancer or not only lung cancer, 2 reports were available only in abstract form. Finally, 33 studies were included (Table 1). Four articles were published in 2015, 5 in 2016, 10 in 2017, 8 in 2018 and 6 in 2019. Seventeen studies are randomized clinical trials, 15 observational studies and 1 is a post-hoc analysis. The number of patients included in the studies ranges from a minimum of 32 to a maximum of 1466 for a total of 16,491 included patients. In most studies, the PROs reported data on standard chemotherapy (first or second line), or target therapy, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), or immunotherapy. Other studies also use chemoradiotherapy, second-line and maintenance therapies. Fifteen (45.45%) compare the QoL of patients treated with two different therapeutic regimens; 1 (3.03%) was a validation study, 2 (6.06%) evaluated PROs ability to detect symptom, 4 (12.12%) evaluated symptom severity, 2 (6.06%) evaluated QoL of patients treated with a specific regimen (nivolumab and brigatinib), 1 (3.03%%) evaluated the QoL of patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation, 8 (24.24%) analyzed the correlation between QoL and different factors: age, EGFR mutation, brain metastasis, Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome, dysphagia, disease progression, physical activity and patients’ and caregivers’ burdens.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1.

Identified Literature Overview

| Author | Year | Study Type | Patient Number | Treatment | Methods | PROs Outcomes | Results | Category | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | King-Kallimanis et al56 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 695 | Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC LC-13, LCSS baseline and after 3 months | Examine age-related differences in patient-reported symptoms and functional domains | No large differences at baseline or in the distributions of change from baseline in PROS between younger and older patients | C4 |

| 2 | Wu et al68 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 301 | Afatinib vs chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-C30 every 21 days until progression | EGFR Mutation Type Influence patient-reported outcomes | First-line afatinib improved lung cancer-related symptoms and GHS/QoL compared with chemotherapy | C1 |

| 3 | Bordoni et al57 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 850 | Atezolizumab or docetaxel | EORTC QLQ-30, EORTC LC-13 day 1 of every cycle and at treatment discontinuation | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with atezolizumab or docetaxel | PROS data support the clinical benefit of atezolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic NSCLC | C4 |

| 4 | Lee et al59 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 419 | Osimertinib Versus Chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-30, EORTC LC-13 baseline, 3 months, 1 year | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with Osimertinib or Chemotherapy | A higher proportion of patients treated with osimertinib had improvement in global health status/quality of life | C4 |

| 5 | Walker et al40 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 145 | Platinum-based doublets including combinations with bevacizumab or pemetrexed | EORTC QLQ-30, EORTC LC-13, MDASI, RALS baseline,1 year | Effect of Brain Metastasis on patient reported outcomes | PROSmeasures show disease progression is associated with worsening HR QoL. Delaying disease progression can sustain better HRQL and reduce symptom burden | C2 |

| 6 | McCarrier et al62 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 51 | Routine cancer care | NSCLC-SAQ | Development of a patient reported outcome Instrument | NSCLC-SAQ is currently undergoing quantitative testing to confirm its measurement properties and support FDA qualification | C6 |

| 7 | Blackhall et al52 | 2015 | Post hoc analysis | 343 | Crizotinib vs chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-30, EORTC LC-13, EQ-5D baseline, day 1 of each cycle and end of treatment | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with crizoinib or Chemotherapy | The benefits of crizotinib in improving symptoms and QoL are demonstrated regardless of whether the comparator is pemetrexed or docetaxel | C3 |

| 8 | LeBlanc et al53 | 2016 | Prospective observational | 97 | Chemotherapy or palliative | Electronic patient-reported outcomes: Patient Care Monitor Patient Care Monitor(PCM) v2.0 four assessments in 6 months | Characterized patients’ symptoms | Patients with aNSCLC face a significant symptom burden, which increases with proximity to death | C3 |

| 9 | LeBlanc et al41 | 2015 | Prospective observational | 99 | Routine cancer care | FACT - G, FACT - L, FACT - F, FAACT four assessments in 6 months | Correlation between CACS and PROs | The weight-based definition is useful in identifying patients with advanced NSCLC who are likely to have significantly inferior survival and who will develop more precipitous declines in physical function and QoL | C2 |

| 10 | Von Verschuer et al51 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 1239 | Carboplatin or cisplatin based doublet chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-30, EORTC LC-13 each visit, any change in treatment or every 6 months | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with carbo or cisplatin | HR QoL data comparing treatments show no difference between carboplatin and cisplatin | C3 |

| 11 | Shallwani et al50 | 2016 | Observational | 47 | First line chemotherapy | SF-36,LCS, SCFS, PG-SGA pre and post chemotherapy | Identify predictors of change in HR QOL in patients undergoing chemotherapy | Pre-chemotherapy 6MWT distance and fatigue severity predicted change in the mental component of HR QOL in patients with advanced NSCLC undergoing chemotherapy, while physical performance declined during treatment | C3 |

| 12 | Sebastian et al34 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 161 | Chemotherapy vs osimertinib | PRO-CTCAE first weekly for 18 weeks and then every 3 weeks for up to 57 weeks | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with chemo or osimertinib | Symptoms were generally mild and not frequent, with some differences in symptom patterns between the two treatment groups | C1 |

| 13 | Brady et al65 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 72 | Surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy | EAT-10, SWAL- QOL | Impact of dysphagia on QOL | Dysphagia is a potential symptom in advanced lung cancer which may impact QOL | C3 |

| 14 | Walker et al49 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 147 | First line (±bevacizumab) | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, MDASI-LC, RALS every cycle during active treatment and monthly in fu for up to 1 year | Impact of disease progression on effectiveness outcomes and QoL | Newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC patients with baseline BM experienced a significantly faster and clinically meaningful deterioration in PRO-based HR QOL compared with those without baseline BM | C3 |

| 15 | Felip et al48 | 2017 | Randomized controlled trials | 795 | 1ʹ Platinum-Based Chemotherapy, 2ʹ Afatinib Versus Erlotinib | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 first visit of each treatment at the end of treatment, and 28 days after treatment | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with afatinib or erlotinib | Significantly more patients who received afatinib versus erlotinib experienced improved scores for GHS/QoL | C3 |

| 16 | Brahmer et al58 | 2017 | Randomized controlled trials | 299 | Pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, EQ-5D baseline and w15 | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy | Pembrolizumab improves or maintains health-related QOL compared with that for chemotherapy | C4 |

| 17 | Reck et al66 | 2018 | Randomized controlled trials | 582 | Nivolumab or docetaxel | LCSS, EQ-5D at baseline, on day 1 of every other cycle for 6 months, two follow-up visits after treatment discontinuation; EQ-5D assessments continued every 3 months for 12 months and then every 6 months thereafter | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with nivolumab or docetaxel | Nivolumab improved disease-related symptoms and overall health status versus docetaxel for second-line treatment of advanced non-squamous NSCLC | C3 |

| 18 | Denis et al43 | 2017 | Randomized controlled trials | 60 | Chemotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitor | E-FAP every three months | Web-mediated follow-up (SR) improved OS due to early relapse detection and better PS at relapse | A web-mediated follow-up algorithm based on self-reported symptoms improved OS due to early relapse detection and better performance status at relapse | C2 |

| 19 | Sztankay et al36 | 2017 | Prospective observational | 83 | First-line palliative chemotherapy | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 each chemotherapy cycle to the start of second-line palliative chemotherapy or at study completion | Symptom severity during MT compared with first-line therapy | HR QOL and symptom burden improve between first-line treatment to MT, the integration of patient-reported outcomes is required to enable shared decision-making and personalised healthcare | C1 |

| 20 | Sloan et al42 | 2016 | Prospective observational | 1466 | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy | NCCTG, EORTC QLQ-LC13, FACT - L, LCSS follow-up | Correlation between being physically active and QOL | Being physically active was related to profound advantages in QOL and survival in a large sample of lung cancer survivors | C2 |

| 21 | Wang et al61 | 2016 | Prospective observational | 92 | IMRT, BPT, 3DCRT, chemoradiotherapy | MDASI baseline, weekly during and after therapy for up to 12 weeks | Valutate MDASI ability to detect symptom | Patients receiving PBT reported significantly less severe symptoms than did patients receiving IMRT or 3DCRT | C5 |

| 22 | Spigel et al67 | 2019 | Randomized controlled trials | 1426 | Nivolumab | EQ-5D, LCSS every 3 months for the first 12 months, then every 6 months | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with nivolumab | The median overall survival for patients with an ECOG PS of 2 was lower than for the overall population but comparable with historical data | C1 |

| 23 | Nguyen et al46 | 2018 | Prospective observational | 32 | Concurrent chemoradiation | EORTC QLQ-C30 baseline, during therapy, at therapy stop and till 1 year after therapy end every 3 months | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with concurrent chemoradiation | Measuring PROs can help to identify issues for improvement of the value of care delivered | C3 |

| 24 | Mendoza et al60 | 2019 | Prospective observational | 460 | Treatment-naïve | MDASI between 30 days prediagnosis and 45 days postdiagnosis | Assessment of baseline QoL for palliative therapy evaluation, disease-related symptoms differentation and control | Quantification of pretreatment symptom burden can inform patient-specific palliative therapy and differentiate disease-related symptoms from treatment-related toxicities. Poorly controlled symptoms could negatively affect treatment adherence and therapeutic outcomes | C5 |

| 25 | Novello et al47 | 2015 | RANDOMIZED controlled trials | 1314 | Nintedanib plus docetaxel vs placebo plus docetaxel | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, EQ-5D, EQ-5D screening, day 1 of each cycle, at the end of active treatment, first FU | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with second-line nintedanib | The significant OS benefit observed with the addition of nintedanib to docetaxel therapy was achieved with no detrimental effect on patient self-reported QoL | C3 |

| 26 | Pèrol et al44 | 2016 | Randomized controlled trials | 1253 | Ramucirumab plus docetaxel vs placebo plus docetaxel | LCSS baseline, every 3-week cycle, the summary visit,and at the 30-day FU | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with ramucirumab plus docetaxel vs placebo plus docetaxel | Adding ramucirumab to docetaxel did not impair patient QoL, symptoms, or functioning | C3 |

| 27 | Boye et al45 | 2016 | Randomized controlled trials | 218 | Pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by gefitinib maintenance therapy or gef monotherapy | LCSS baseline, at each study visit, after discontinuation | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by gef maintenance therapy or gef monotherapy | LCSS scoresn were more favorable in the G group than in the PC/G group | C3 |

| 28 | Wood et al54 | 2019 | Prospective observational | 1030 | First line | EQ-5D, WPAI:GH, EORTC QLQ-C30 (+ZBI for caregivers) | Linking patient clinical factors to patient and caregiver burden | As patients’ functionality deteriorates as measured by the ECOG-PS, so do their outcomes related to health utility, work productivity, activity impairment and HR QoL. This deterioration is also reflected in increased caregiver burden and activity impairment | C3 |

| 29 | Barlesi et al55 | 2019 | Randomized controlled trials | 1034+427 caregivers | Pembrolizumab vs Docetaxel | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, EQ-5D cycles 1, 2, 3, 5, and every 4 cycles until discontinuation and30-day safety assessment | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with pembrolizumab vs docetaxel | HR QoL and symptoms are maintained or improved to a greater degree with pembrolizumab than with docetaxel | C4 |

| 30 | Geater et al35 | 2015 | Randomized controlled trials | 364 | Afatinib or gemcitabine followed by cisplatin d1 and gem d8 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 randomization and every 3 weeks until PD or start of new treatment | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with Afatinib Versus Cisplatin/Gemcitabine | Afatinib improved PFS and PROs versus chemotherapy in EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients. Progression was associated with statistically significant worsening in QoL | C1 |

| 31 | Reck et al39 | 2019 | Randomized controlled trials | 583 | Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy | LCSS, EQ-5D baseline, w6, w12, w18, w24, w30, w36 | Evaluate the QoL of patient treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy | First-line nivolumab þ ipilimumab demonstrated early, sustained improvements in PROs versus chemotherapy | C2 |

| 32 | Kawata et al38 | 2019 | Randomized controlled trials | 208 | Two dosing regimens of brigatinib | EORTC QLQ-C30 every cycle | Evaluate the impact of brigatinib treatment on health utilities using two published algorithms | Converting QLQ-C30 scores into utilities in trials using established mapping algorithms can improve evaluation of medicines from the patient perspective. Both algorithms suggested that brigatinib improved health utility in crizotinib-refractory ALK + NSCLC patients | C1 |

| 33 | McGee et al37 | 2018 | Retrospective observational | 528 | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy | ESAS prior to each outpatient consultation | ESAS scale to identify patient-reported factors that may predict for treatment decisions in advanced NSCLC | Novel role for the ESAS as a prognostic tool that could complement existing patient assessment models | C1 |

Abbreviations: CACS, Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome; 6MWT, 6-minWalk Test; BM, brain Metastasis; GHS, global Health Status; MT, maintenance Therapy; PC/G, maintenance Gefitinib; G, gefitinib Monotherapy; IMRT, Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy; 3DCRT, three-Dimensional Conformal Radiation Therapy; PBT, Proton-Beam Therapy; C1, PROs as Guide in Therapeutic Choice; C2, PROs as Indicator of Disease Progression; C3, Agreement Between PROs and the Evaluated Parameter; C4, PROs to Evaluate the Effects of Immunotherapy; C5, Need to Deepen the Knowledge of PRO; C6, Use of a New Electronic PRO.

We can classify the results of these articles into six categories (Table 2); the first includes all those studies where results indicate the use of PROs as a guide in therapeutic choice: the PRO-CTCAE has the potential to bring the patient’s voice to clinical trials, and to provide insights into the patient’s experiences of treatment,34 the use of PROs measures in addition to PFS in the development of new treatments and as a consideration when choosing available treatment options for patients in the out-patient clinics were provided;35 the integration of PROs generated in clinical trials as well as at an individual patient level is required to enable shared decision-making and personalized health care based on a mutual understanding of treatment objectives and expectations.36 The ESAS questionnaire has a key role for the data it provides not only as a guide to symptom management for improved quality of life, but also in the development of optimal treatment plans and estimation of OS.37 In addition, it was reported that converting QLQ-C30 scores into utilities in trials using established mapping algorithms can improve the evaluation of medicines from a patient’s perspective.38

Table 2.

Results Classification in Categories About the Topic of the Article

| Topic | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| PROs as guide in therapeutic choice | 7 |

| PROs as indicator of disease progression | 5 |

| Agreement between PROs and the evaluated parameter | 13 |

| PROs to evaluate the effects of immunotherapy | 5 |

| Need to deepen the knowledge of PRO | 2 |

| Use of a new electronic PRO | 1 |

Abbreviation: PROs, Patient-Reported Outcomes.

The second part of the article concerns the use of PROs as an indicator of disease progression, patient’s QoL and survival. The differences of HR QoL evaluated with different PROs for patients treated with the two treatments under evaluation and their concordance about the outcome evaluated in the study were reported.39 Disease progression had a significant adverse impact on many PROs’ endpoints;40 PROs showed that they were useful in identifying patients with advanced NSCLC who are likely to have significantly lower survival.41 The prognostic power of overall QoL on the survival of lung cancer patients and the advantages for lung cancer survivors reporting to be physically active was demonstrated versus those who were not physically active;42 the early detection of symptomatic relapse and management of symptoms through a web-mediated individualized follow-up strategy provided an improvement in quality of life and overall survival.43

The third group included the studies that evaluated the agreement between the PROs and the evaluated parameters: concordance between LCSS and ECOG PS measurements and tumor-related symptoms is reported.44,45 The use of PROs for the accurate assessment of health-related QoL in patients with lung cancer and to identify instruments to improve the value of care delivered was reported.46,47 The utility of PROs to evaluate improvements in HR QoL and symptoms burden of the subgroups of patients treated with nivolumab and to analyze the AEs between the two treatment groups was reflected in PRO outcomes.48 The correlation between PRO scores and deterioration of HR QoL in patient with brain metastases at the diagnosis of lung cancer was evaluated.49 Using the EAT-10 and SWAL-QoL questionnaires, dysphagia was demonstrated a potential symptom in advanced lung cancer which may impact QoL, and some studies reported change in the mental component of HR QoL related to PROs outcomes50 or showed the symptoms that need to be addressed in routine care of advanced NSCLC;51 different studies reported that PROs are arguably more representative of the patient perspective than physician-reported outcomes.52–54

The fourth group concerned the evaluation of the role of PROs in assessing the effects of immunotherapy: the EORTC QLQ-LC13 instrument may not adequately reflect the experiences of patients who receive new therapies.55 They concluded that commonly occurring symptoms attributed to immunotherapy can be found by using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC13 questionnaires. PROs disease questionnaire find some, but not all relevant symptoms in a disease area and are unlikely to discover several common toxicities related to immunotherapy drugs.56 PROs assessments should be considered standard tools in the future of cancer immunotherapy research because their use will lead to a better understanding of the effect of immunotherapy on patients’ outcomes. Beyond the traditional parameters of OS and radiographic endpoints,57 some authors reported the need to develop instruments capable of evaluating the treatment-related symptoms hand-in-hand with the introduction of new therapies with specific related symptoms,58 the prospective evaluation of PROs with the appropriate hypothesis and instruments, is vital particularly in clinical trials that evaluate new therapeutics in incurable cancers.59

Another group of studies expresses the need to deepen the knowledge of PROs: the MDASI scale was used to evaluate patient-reported symptoms. This scale does not evaluate coughing, a common symptom in lung cancer; as a standard of care and in clinical trials, the MDASI-LC test, which includes coughing, must be used to a complete evaluation of the patient’s symptoms.60 Widely used PRO-based symptom assessment tools are needed to facilitate a comparison of results with those of other published studies.61 Only one study62 reported the use of a new electronic PRO: the NSCLC-SAQ, after Food and Drug Administration (FDA) qualification, will be publicly available to capture patient-reported NSCLC-related symptoms via electronic data entry platforms. The use of PROs in the studies evaluated, it is not always a primary outcome. In some cases, especially for studies that evaluate PROs as a guide in therapeutic choice, PROs as indicators of disease progression and agreement between PROs and the evaluated parameters, the data obtained from the use of PROs is a secondary outcome of the study.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify and describe peer‐reviewed PROs used to evaluate QoL in lung cancer patients and to evaluate the feasibility and utility of PROs in surveillance strategies. Worldwide, lung cancer remains a disease with severe morbidity and mortality. Therefore, in addition to survival, the QoL of the patient is of great importance. There is a growing interest in measuring the QoL with the aid of PROs.63 The subjective data about how therapies and diseases can modify patients’ lives can be useful for the physicians and can compensate for the lack of time the physicians have for outpatients to understand the patients’ point of view. In the studies reviewed, PRO-based endpoints are indicative of clinical benefit in terms of patient symptoms and overall quality of life. The addition of PROs to traditionally collected outcome measures (OS, PFS, DFS) can offer a comprehensive overview of patient status. In an optimal setting, the PROs should allow for an overall assessment of QoL, along with specific questionnaires to assess specific effects associated with the disease and treatment. The most frequently used instruments are EORTC QLQ-30 (16, 50%) and EORTC LC-13 (14, 43.75%) and in some studies (37.5%) EORTC QLQ-C30 was supplemented with the EORTC QLQ-LC13, result in agreement with the European literature.64

There was great dispersion in data collection timing: the baseline is often collected, and subsequent checks ranging from a few weeks to some years or until PD or the start of a new treatment.

It must be emphasized that there is much evidence in the literature about the benefits of collecting and using PROs in lung cancer populations, for treatment monitoring,35,38-40,44–48,51,55,57-59,65–67 detection of symptoms,36,37,41,50,53,54,60,65 the role of patient or pathology characteristics on QoL,40,42,56,68 to improve patient-clinician communication and patient satisfaction.43,61,62 Only one study about the effect of disease progression on QoL was identified49 assessing the use of PROs related to efficacy outcomes (PFS, OS). Data on PRO completion rates are available for 20 studies (60.61%) (Table 3), only in 3 studies (15%) was it lower than 80%;44,47,59 for the others 17 (85%) it was higher than 80%.35,36,39,40,45,48,49,51,52,55-58,61,66-68 Only in one study (5%) did the authors report a completion rate of 100%.52 In most cases, frequencies decreased over time from baseline to subsequent measurements. The reasons given in the different studies were the increasing number of patients who discontinued the study due to disease progression, physician decision, adverse events, or death and the incomplete patient participation at each time point.

Table 3.

Literature Data

| Author | Number of Patients Complied PROs (%) | Compliance | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| King-Kallimanis et al56 | 695 (100) | 90–80% >95% |

No large differences at baseline or in the distributions of change from baseline in PROs between younger and older patients |

| Wu et al68 | 301(100) | 90% | First-line afatinib improved lung cancer-related symptoms and GHS/QoL compared with chemotherapy |

| Bordoni et al57 | 850(100) | >95%, >80% | PROs data support the clinical benefit of atezolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic NSCLC |

| Lee et al59 | 419(100) | 88–72% 60% |

A higher proportion of patients treated with osimertinib had improvement in global health status/quality of life |

| Walker et al40 | 145(100) | 98% | PROs measures show disease progression is associated with worsening HR QOL. Delaying disease progression can sustain better HRQL and reduce symptom burden |

| McCarrier et al62 | 10(19.6) | nr | NSCLC-SAQ is currently undergoing quantitative testing to confirm its measurement properties and support FDA qualification |

| Blackhall et al52 | 343(100) | 83–100% | The benefits of crizotinib in improving symptoms and QOL are demonstrated regardless of whether the comparator is pemetrexed or docetaxel |

| LeBlanc et al53 | 97(100) | nr | Patients with a NSCLC face a significant symptom burden, which increases with proximity to death |

| LeBlanc et al41 | 99(100) | nr | The weight-based definition is useful in identifying patients with advanced NSCLC who are likely to have significantly inferior survival and who will develop more precipitous declines in physical function and QOL |

| von Verschuer et al51 | 495(39.96) | 87–68% | HR QOL data comparing treatments show no difference between carboplatin and cisplatin |

| Shallwani et al50 | 47(100) | nr | Pre-chemotherapy 6MWT distance and fatigue severity predicted change in the mental component of HR QOL in patients with advanced NSCLC undergoing chemotherapy, while physical performance declined during treatment |

| Sebastian et al34 | 161(100) | nr | Symptoms were generally mild and not frequent, with some differences in symptom patterns between the two treatment groups |

| Brady et al65 | 72(100) | nr | Dysphagia is a potential symptom in advanced lung cancer which may impact QOL |

| Walker49 | 147(100) | 98% | Newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC patients with baseline BM experienced a significantly faster and clinically meaningful deterioration in PRO-based HR QOL compared with those without baseline BM |

| Felip et al48 | 795(100) | 95% | Significantly more patients who received afatinib versus erlotinib experienced improved scores for (GHS)/QoL. |

| Brahmer et al58 | 299(100) | 90–80% | Pembrolizumab improves or maintains health-related QOL compared with that for chemotherapy |

| Reck et al66 | 582(100) | 98% | Nivolumab improved disease-related symptoms and overall health status versus docetaxel for second-line treatment of advanced non-squamous NSCLC |

| Denis et al43 | 60(100) | nr | A web-mediated follow-up algorithm based on self-reported symptoms improved OS due to early relapse detection and better performance status at relapse |

| Sztankay et al36 | 83(100) | 84% | HR QOL and symptom burden improve between first-line treatment to MT, the integration of patient-reported outcomes is required to enable shared decision-making and personalized healthcare |

| Sloan et al42 | 1466(100) | nr | Being physically active was related to profound advantages in QOL and survival in a large sample of lung cancer survivors |

| Wang et al61 | 92(100) | 96% | Patients receiving PBT reported significantly less severe symptoms than did patients receiving IMRT or 3DCRT |

| Spigel et al67 | 1426(100) | 80% | The median overall survival for patients with an ECOG PS of 2 was lower than for the overall population but comparable with historical data |

| Nguyen et al46 | 32(100) | nr | Measuring PROs can help to identify issues for improvement of the value of care delivered |

| Mendoza et al60 | 460(100) | nr | Quantification of pretreatment symptom burden can inform patient-specific palliative therapy and differentiate disease-related symptoms from treatment-related toxicities. Poorly controlled symptoms could negatively affect treatment adherence and therapeutic outcomes |

| Novello et al47 | 1051(79.98) | 70% | The significant OS benefit observed with the addition of nintedanib to docetaxel therapy was achieved with no detrimental effect on patient self-reported QoL |

| Pèrol et al44 | 1253(100) | 75% | Adding ramucirumab to docetaxel did not impair patient QoL, symptoms, or functioning |

| Boye et al45 | 236(100) | 92% | LCSS scores were more favorable in the G group than in the PCnrG group |

| Wood et al54 | 1030(100) | nr | As patients’ functionality deteriorates as measured by the ECOG-PS, so do their outcomes related to health utility, work productivity, activity impairment and HR QoL. This deterioration is also reflected in increased caregiver burden and activity impairment |

| Barlesi et al55 | 1034+427 (100) |

95–85% | HR QoL and symptoms are maintained or improved to a greater degree with pembrolizumab than with docetaxel |

| Geater et al35 | 364(100) | 96–88% | Afatinib improved PFS and PROs versus chemotherapy in EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients. Progression was associated with statistically significant worsening in QoL |

| Reck et al39 | 583(100) | 90–80% | First-line nivolumab vs ipilimumab demonstrated early, sustained improvements in PROs versus chemotherapy |

| Kawata et al38 | 208(100) | nr | Converting QLQ-C30 scores into utilities in trials using established mapping algorithms can improve evaluation of medicines from the patient perspective. Both algorithms suggested that brigatinib improved health utility in crizotinib-refractory ALK + NSCLC patients |

| McGee et al37 | 528(100) | nr | Novel role for the ESAS as a prognostic tool that could complement existing patient assessment models |

Abbreviations: CACS, Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome; 6MWT, 6-minWalk Test; BM, brain metastasis; GHS, global Health Status; MT, maintenance Therapy; PCnrG, maintenance Gefitinib; G, gefitinib Monotherapy; IMRT, Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy; 3DCRT, three-Dimensional Conformal Radiation Therapy; PBT, Proton-Beam Therapy; Nr, not reported.

PROs are primarily collected in the context of scientific research. Moreover, the majority of the clinical trials do not use generic instruments but give preference to disease-specific instruments as they are more sensitive to subtle changes. Assessment of HRQL can help to better understand the physical, mental, and emotional implications of cancer and the effects of treatment on patients. PRO use was developed in scientific research to understand the efficacy of a treatment and to evaluate symptom type and impact on QoL and to act in a timely manner to control the symptom and its consequences on QoL. They become important also to evaluate new therapies taking into consideration, in addition to clinical results, also the quality of life of the patient. Since the association of QoL with survival PROs use appears to be a strong and independent factor in the prediction of survival in lung cancer.64,69

The literature demonstrates that the use of PROs continues to increase, the collected data support the hypothesis that PROs can play an important role as part of the health care and that routine use implementation could improve patient management: early identification of symptoms and adverse events due to treatment, monitor the patient’s response to therapy and improve communication between patient, health care professional and caregivers70 with a consequent reduction of costs for exams, therapies and hospitalizations avoidable with a timely intervention. Steps for routine implementation of PROs were previously reported71 but cost-effectiveness of the use of PROs is still under evaluation. Despite the good psychometric properties and all the possible advantages of instruments already mentioned, the feasibility of the routine implementation of PROs finds some practical difficulties: the availability of personnel, programming of training for the correct administration and interpretation of PROs, costs, time required and the need for people able to analyze the data collected.72 Without proper preparation and organization, their use is disruptive to normal work routines. One of the things that made the PROs easier to administer, but mostly simplified the data collection and analysis phase, was the transition from paper versions to electronic platforms, with a significant reduction of time.73

Considering the fact that there are almost 200 tumor types, PROs are not cancer-specific because they do not consider that different cancers involved different symptoms, as well as they do not specify selected treatment benefits or toxicity. There is no objective consideration and no comparison between the questionnaires that can be formulated. Further studies would be useful to assess the symptoms associated with different therapies such as immunotherapy.

However, there are many considerations that need attention to enable long-term, quality collection and use of PRO data within routine clinical settings.71 These include identifying the goals of PROs collection; patient selection; setting and timing of assessments; choice of questionnaire; scale of interpretation and the way to facilitate it, developing strategies for responding to issues detected by the questionnaires and evaluating the impact of the PROs in the practice. To our knowledge, there are no comparison parameters between the various PROs and therefore it is difficult to find a method of evaluation of utility and feasibility applicable in the comparison between the different used tools. Utility and feasibility are described by the assessment of costs, times, staff required, limits of applicability and interpretation issues.

The limitations of this revision are the reduced time period of publication, the choice of PROs also not specific for lung cancer and the exclusion of studies in which PROs were not the primary objective. PROs results, obtained in a routine collection could provide the basis on which adapt therapy and interventions to the needs of the patient, to improve both QoL and the probability of survival. A study carried out in 201174 shows the improvement of the communication between the patient and the health care professional, and the monitoring of the response to treatment and the satisfaction of the patient when routinely collecting PROs. More recently, a randomized clinical trial investigated the influence of routinely collecting PROs in cancer patients.75 It evaluated the use of e-mail alerts to severe symptoms or to usual care; the e-mail system allowed an immediate action such as medications or access to the emergency room. The results were a better control of symptoms in the e-mail group, resulted in a better HR QoL, fewer visits to the emergency room, fewer hospitalizations, longer duration of palliative chemotherapy and both improved one-year survival and quality-adjusted survival.76 PROs are also applied in the field of palliative care, where different studies have tried to evaluate the impact on the OS and patients QoL but the factors to be evaluated, including those related to the families and the patient’s caregivers are complex. The number of studies is still reduced and the results are difficult to compare.77,78

The inclusion of PROs as endpoints in clinical trials is encouraged by the FDA, the European Medicines Agency (EMA)79 and scientific societies as the European Society of Medical Oncology.80 US Food and Drug Administration has recently published guidelines on the review and evaluation of PROs to encourage their appropriate use in regulatory studies and decisions.

Conclusion

A great variety of PROs are used with lung cancer patients in order to improve quality of care. A general questionnaire to assess overall QoL, which can be supplemented with disease-specific questionnaires allowing for the assessment of QoL of different treatment methods seems to be most effective. PROs can be used for different purposes and can be focused on the specific disease or symptoms or related to the progression of the disease. The standard routine use of PROs is still not widely recognized, despite the positive aspects reported. This can be related to organization, timing and personnel difficulties. A step towards solving these problems is the introduction of electronic PROs. We emphasized the unmet need for focused research to justify and to guide the analytic method of PROs to facilitate the interpretation of patient experience. Future research should assess the applicability of PROs in routine clinical practice.

Abbreviations

SF-36, 36-item Short-Form Health Survey; MDASI, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; DFS, disease-free survival; EAT-10, Eating Assessment Tool; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FAACT, Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment; FACT - F, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Fatigue; FACT - G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General; FACT - L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Lung Cancer; HR QoL, health-related quality of life; LCSS, Lung Cancer Symptom Scale; NSCLC-SAQ, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire; OS, overall survival; PROs, Patient Reported Outcomes; PG-SGA, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment; PRO-CTCAE, Patient-Reported Outcomes version of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; PCM, Patients’ symptoms via the Patient Care Monitor; RALS, Rotterdam Activity Level Scale; SWAL-QoL, Swallowing Quality of Life instrument; LCS, The Lung Cancer Subscale; SCFS, The Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; WPAIGH, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment: General Health; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Luigi Cavanna reports consulting and advisory roles for AstraZeneca and Merck; travel and accommodation expenses from Celgene, Pfizer, and Ipsen. The other authors have no financial support or relationships that may pose a conflict of interest with this work.

References

- 1.Duma N, Santana-Davila R, Molina JR. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(8):1623–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tishelmann C, Degner LF, Rudman A, et al. Symptoms in patients with lung carcinoma: distinguishing distress from intensity. Cancer. 2005;104:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooley ME. Symptoms in adults with lung cancer: a systematic research review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:137–153. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00150-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giroux Leprieur E, Dumenil C, Julie C, et al. Immunotherapy revolutionises non-small-cell lung cancer therapy: results, perspectives and new challenges. Eur J Cancer. 2017;78:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouazza YB, Chiairi I, El Kharbouchi O, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in the management of lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Kaasa S, Sullivan M. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Question- naire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC study group on quality of life. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(5):635–642. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Kris MG, Potanovich LM. Quality of life assessment in indi- viduals with lung cancer: testing the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS). Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(Suppl 1):S51–8. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(05)80262-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Kris MG, et al. Measurement of quality of life in patients with lung cancer in multicenter trials of new therapies. Psychometric assess- ment of the lung cancer symptom scale. Cancer. 1994;73(8):2087–2098. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson symptom inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Lu C, et al. Measuring the symptom burden of lung cancer: the validity and utility of the lung cancer module of the M. D. Anderson symptom inventory. Oncologist. 2011;16:217–227. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Haes JCJM, Olschewski M, Fayers PM, et al. Measuring the Quality of Life of Cancer Patients with the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist: a Manual. Groningen, The Netherlands: Northern Centre for Healthcare Research (NCH); 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abernethy AP, Herndon JE 2nd, Wheeler JL, et al. Feasibility and acceptability to patients of a longitudinal system for evaluating cancer related symptoms and quality of life: pilot study of an e/Tablet data collection system in academic oncology. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;37(6):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abernethy AP, Herndon JE 2nd, Wheeler JL, et al. Improving health care efficiency and quality using tablet personal computers to collect research-quality, patient-reported data. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):1975–1991. doi: 10.1111/hesr.2008.43.issue-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Uronis H, et al. Validation of the patient care monitor (Version 2.0): a review of system assessment instrument for cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40(4):545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:192e211. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cella D, Eton DT, Fairclough DL, et al. What is a clinically meaningful change on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) Questionnaire? Results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Study 5592. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:285e295. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00477-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:547e561. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00529-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopman WM, Towheed T, Anastassiadeset T, et al. Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163(3):265–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE Jr. SF-36 Health Survey Update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(24):3130–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella DF, Bonomi E, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12(3):199–220. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):207–221. doi: 10.1023/A:1015276414526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz A, Meek P. Additional construct validity of the schwartz cancer fatigue scale. J Nurs Meas. 1999;7(1):35–45. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.7.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabrielson DK, Scaffidi D, Leung E, et al. Use of an abridged scored patient-generated subjective global assessment (abPG-SGA) as a nutritional screening tool for cancer patients in an outpatient setting. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65(2):234–239. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.755554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US National Cancer Institute. Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE™). Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/. Accessed 9May 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the eating assessment tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(12):919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHorney CA, Robbins J, Lomax K, et al. The SWAL- QOL and SWAL- CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17(2):97–114. doi: 10.1007/s00455-001-0109-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarrier KP, Atkinson TM, DeBusk KP, et al. Qualitative development and content validity of the Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC-SAQ), a patient-reported outcome instrument. Clin Ther. 2016;38(4):794–810. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlated of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. doi: 10.1177/082585979100700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sebastian M, Rydén A, Walding A, Papadimitrakopoulou V. Patient-reported symptoms possibly related to treatment with osimertinib or chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;122:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geater SL, Xu CR, Zhou C, et al. Symptom and quality of life improvement in LUX-Lung 6: an open-label phase III study of afatinib versus cisplatin/gemcitabine in Asian patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(6):883–889. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sztankay M, Giesinger JM, Zabernigg A, et al. Clinical decision-making and health-related quality of life during first-line and maintenance therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): findings from a real-world setting. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:565. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3543-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGee SF, Zhang T, Jonker H, et al. The impact of baseline edmonton symptom assessment scale scores on treatment and survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(1):e91–e99. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawata AK, Lenderking WR, Eseyin OR, et al. Converting EORTC QLQ-C30 scores to utility scores in the brigatinib ALTA study. J Med Econ. 2019;22(9):924–935. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1624080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reck M, Schenker M, Lee KH, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with high tumour mutational burden: patient-reported outcomes results from the randomised, open-label, phase III CheckMate 227 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker MS, Wong W, Ravelo A, Miller PJE, Schwartzberg LS. Effectiveness outcomes and health related quality of life impact of disease progression in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC treated in real-world community oncology settings: results from a prospective medical record registry study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0735-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBlanc TW, Nipp RD, Rushing CN, et al. Correlation between the international consensus definition of the Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome (CACS) and patient-centered outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloan JA, Cheville AL, Liu H, et al. Impact of self-reported physical activity and health promotion behaviors on lung cancer survivorship. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:66. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0461-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, et al. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9):djx029. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pérol M, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, et al. Quality of life results from the Phase 3 REVEL randomized clinical trial of ramucirumab-plus-docetaxel versus placebo-plus-docetaxel in advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients with progression after platinum-based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2016;93:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boye M, Wang X, Srimuninnimit V, et al. First-line pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by gefitinib maintenance therapy versus gefitinib monotherapy in East Asian never-smoker patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: quality of life results from a randomized phase III trial. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17(2):150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen PAH, Vercauter P, Verbeke L, Beelen R, Dooms C, Tournoy KG. Health outcomes for definite concurrent chemoradiation in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Respiration. 2019;97(4):310–318. doi: 10.1159/000493984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novello S, Kaiser R, Mellemgaard A, et al. LUME-LUNG 1 study group. Analysis of patient-reported outcomes from the LUME-Lung 1 trial: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III study of second-line nintedanib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(3):317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felip E, Hirsh V, Popat S, et al. Symptom and quality of life improvement in LUX-lung 8, an open-label phase III study of second-line afatinib versus erlotinib in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the lung after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;19–1:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker MS, Wong W, Ravelo A, Miller PJE, Schwartzberg LS. Effect of brain metastasis on patient-reported outcomes in advanced NSCLC treated in real-world community oncology settings. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;19–2:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shallwani SM, Simmondsc MJ, Kasymjanova G, Spahija J. Quality of life, symptom status and physical performance in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy: an exploratory analysis of secondary data. Lung Cancer. 2016;99:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Verschuera U, Schnellb R, Tessenc HW, et al. Treatment, outcome and quality of life of 1239 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer-final results from the prospective German TLK cohort study. Lung Cancer. 2017;112:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackhall F, Kim DW, Besse B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life in PROFILE 1007: a randomized trial of crizotinib compared with chemotherapy in previously treated patients with nALK-Positive advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1625–1633. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LeBlanc TW, Nickolich M, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, Locke SC, Abernethy AP. What bothers lung cancer patients the most? A prospective, longitudinal electronic patient-reported outcomes study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3455–3463. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2699-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood R, Taylor-Stokes G, Lees M. The humanistic burden associated with caring for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in three European countries-a real-world survey of caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1709–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4419-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barlesi F, Garon EB, Kim DW, et al. Health-related quality of life in KEYNOTE-010: a phase II/III study of pembrolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced, programmed death ligand 1-expressing NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(5):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.King-Kallimanis BL, Kanapuru B, Blumenthal GM, Theoret MR, Kluetz PG. Age-related differences in patient-reported outcomes in patients with advanced lung cancer receiving anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Semin Oncol. 2018;45:201–209. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bordoni R, Ciardiello F, vonPawel J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in OAK: a phase III study of atezolizumab versus docetaxel in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19:441–449.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brahmer JR, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Health-related quality-of-life results for pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced, PD-L1-positive NSCLC (KEYNOTE-024): a multicentre, international, randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1600–1609. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30690-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee CK, Novello S, Rydén A, Mann H, Mok T. Patient-reported symptoms and impact of treatment with osimertinib versus chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the AURA3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18):1853–1860. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendoza TR, Kehl KL, Bamidele O, et al. Assessment of baseline symptom burden in treatment-naïve patients with lung cancer: an observational study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3439–3447. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4632-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, et al. Prospective study of patient-reported symptom burden in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing proton or photon chemoradiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(5):832–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCarrier KP, Atkinson TM, Debusk KPA, Liepa AM, Scanlon M, Coons SJ. Qualitative development and content validity of the Non‐small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC‐SAQ), A patient‐reported outcome instrument. Clin Ther. 2016;38(4):794‐810. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Damm K, Roeske N, Jacob C. Health-related quality of life questionnaires in lung cancer trials: a systematic literature review. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sloan JA, Zhao X, Novotny PJ, et al. Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and non-small-cell lung cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:pp.1498–1504. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brady GC, Roe JWG, O’ Brien M, Boaz A, Shaw C. An investigation of the prevalence of swallowing difficulties and impact on quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:515–519. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3858-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reck M, Brahmer J, Bennett B, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab or docetaxel in CheckMate 057. Eur J Cancer. 2018;102:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spigel DR, McCleod M, Jotte RM, et al. Safety, efficacy, and patient-reported health-related quality of life and symptom burden with nivolumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, including patients aged 70 years or older or with poor performance status (CheckMate 153). J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(9):1628–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu Y-L, Hirsh V, Lecia V, et al. Does EGFR mutation type influence patient-reported outcomes in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small- cell lung cancer? Analysis of two large, phase iii studies comparing afatinib with chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 3 and LUXLung 6). Patient. 2018;11:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0287-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ediebah DE, Coens C, Zikos E, et al. Does change in health-related quality of life score predict survival? Analysis of EORTC 08975 lung cancer trial. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:pp.2427–2433. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boyce MB, Browne JP. Does providing feedback on patient-reported outcomes to healthcare professionals result in better outcomes for patients? A systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:pp.2265–2278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0390-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:pp.1305–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gralla RJ. Quality-of-life evaluation in cancer: the past and the future. Cancer. 2015;121:pp.4276–4278. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Stewart JA, Meharchand JM, Wierzbicki R, Leighl N. Can a computerized format replace a paper form in PROSand HRQL evaluation? Psychometric testing of the computer-assisted LCSS instrument (eLCSS-QL). Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:pp.165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1507-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:pp.211. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:pp.557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dudgeon D. The Impact of Measuring Patient-Reported Outcome Measures on Quality of and Access to Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S1):S76–S80. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Toscani I, et al. Can early palliative care with anticancer treatment improve overall survival and patient-related outcomes in advanced lung cancer patients? A review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(9):2945–2953. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4184-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marquis P, Caron M, Emery MP, Scott JA, Arnould B, Acquadro C. The role of health-Related quality of life data in the drug approval processes in the US and Europe. Pharm Med. 2012;25:pp. 147–160. doi: 10.1007/BF03256856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann Oncol. 2015;26:pp.1547–1573. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- US National Cancer Institute. Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE™). Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/. Accessed 9May 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]