Abstract

Background

Sertindole is an atypical antipsychotic, which is thought to give a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects at clinically effective doses than typical antipsychotic drugs. In December 1998, Lundbeck Ltd., the manufacturers of sertindole, voluntarily suspended the availability of the drug due to concerns about cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death associated with its use. However, based on the advice of an appointed expert group, the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) lifted the suspension of sertindole in October 2001, a decision that was ratified by the European Commission on the 26th of June 2002. Lundbeck have committed to the CPMP to carry out two post‐marketing surveillance (PMS) studies (which were initiated in July 2002) to provide additional epidemiological data under conditions of normal drug usage. Initial marketing of the product will be restricted and Lundbeck is currently in discussions with the US health authorities (FDA) to investigate whether, and if so when, it would be possible to launch Serdolect in the US market.

Objectives

To determine the effects of sertindole compared with placebo, typical and other atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia and related psychoses.

Search methods

Our Initial searches included electronic searches of Biological Abstracts (1980‐1999), The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 1999), The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (August 2000), EMBASE (1980‐1999), LILACS (1982‐1996), MEDLINE (1966‐1999), PSYNDEX (1977‐1995) and PsycLIT (1974‐1999). In addition, we searched pharmaceutical databases on the Dialog Corporation Datastar and Dialog services. We searched references of all identified studies for further trials. We contacted the manufacturer of sertindole and authors of trials.

We updated the literature search by searching the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register in April 2003.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials that compared sertindole to placebo or other antipsychotic (atypical or typical) drug treatments for patients with schizophrenia or related psychosis .

Data collection and analysis

We independently inspected citations and, where possible abstracts; ordered papers for re‐inspection and quality assessment and independently extracted data.

For homogeneous dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio (RR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and, where appropriate, the number needed to treat (NNT) or number needed to harm (NNH) on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we calculated weighted mean differences (WMD). We inspected all data for heterogeneity.

Main results

Currently the review includes three studies with a total of 1,104 participants. One was a medium term (eight weeks) placebo controlled study that examined three different doses of sertindole (8, 12 and 20mg/day). The remaining two studies compared the use of sertindole with haloperidol (10mg/day). One was a short term study (six weeks) that looked at four different doses of sertindole (8, 16, 20, 24mg/day) and the other was a long term study (one year) that evaluated the use of sertindole 24mg/day in participants attending outpatients.

We excluded two large important studies because they did not report any usable data. (Both had greater than 50% loss to follow‐up and data on 'leaving the study early' was inadequately reported).

Sertindole versus placebo:

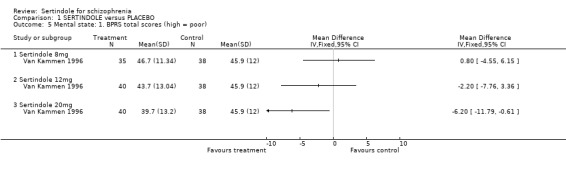

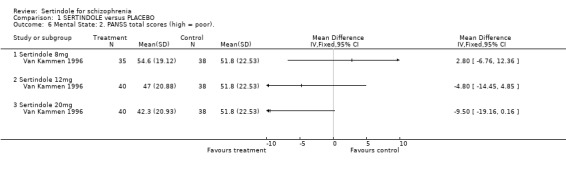

Sertindole at 20mg/day was found to be more effective than placebo in terms of BPRS total scores (1 study, n=78, MD 6.2, CI ‐11.8 to ‐0.6) and CGI total end point scores (1 study, n=78, MD ‐0.9, CI ‐1.6 to ‐0.2). A marginally statistically significantly greater number of participants that were treated with 20 mg of sertindole were reported to have been 'very much improved' as compared to those taking placebo (1 study, n=102, RR 7.6, CI 1.0 to 57.9, NNT 7.9, CI 4.3 to 41.1). There was no statistically significant difference between sertindole at 8 or 12 mg/day and placebo for these three outcome measures.

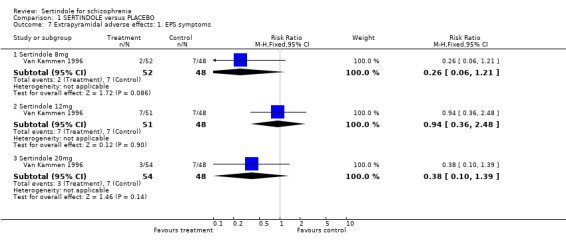

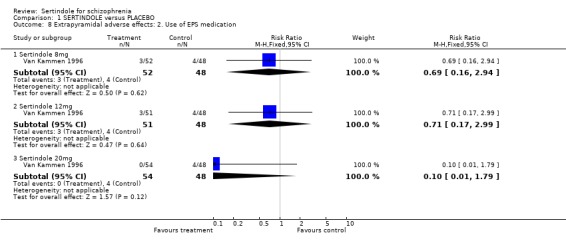

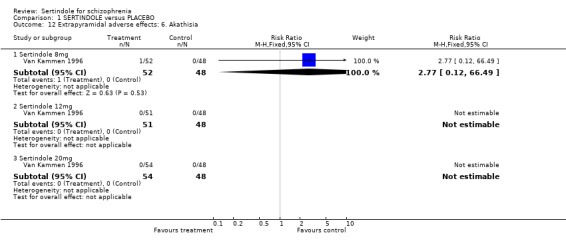

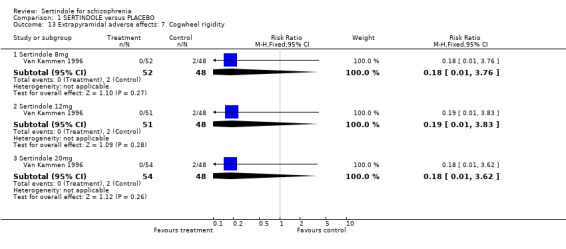

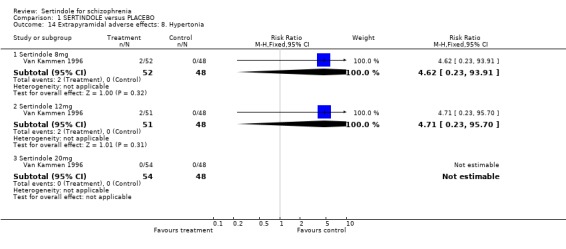

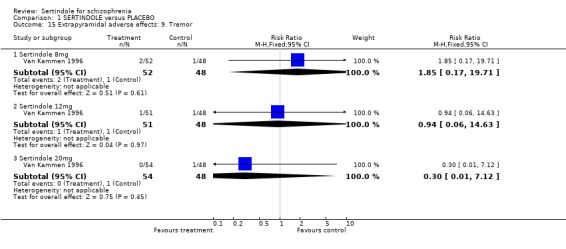

There were no statistically significant differences between sertindole (8, 12 or 20 mg) and placebo for the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, extrapyramidal related events or use of medication to avoid extrapyramidal symptoms. There were no statistically significant differences found between sertindole and placebo for the movement disorders akathisia, cogwheel rigidity, hypertonia and tremor or somnolence.

At eight weeks a statistically significant difference between placebo and all sertindole groups (8, 12 and 20 mg) for mean change from baseline in the QT and QTc intervals were observed (p values and SD were not reported).

There was a statistically significant greater mean weight gain among participants taking sertindole (20 mg, mean weight gain of 3.3 kg) as compared to placebo (mean weight gain of 0.8 kg; p<0.05).

Sertindole versus haloperidol:

At one year, a greater number of participants who were treated with haloperidol as compared to sertindole (24mg/day) were leaving the study early due to any reason (1 study, n=282, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNH 8.8, CI 4.7 to 74.0) or non‐compliance (1 study, n=282, RR 0.2, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 12.8, CI 7.7 to 37.8). However, at six weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between sertindole (at 8, 16, 20, or 24mg) and haloperidol for this latter outcome.

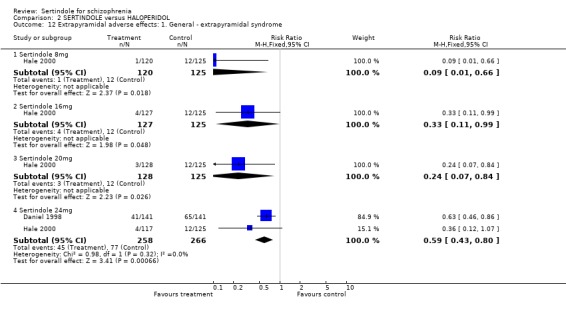

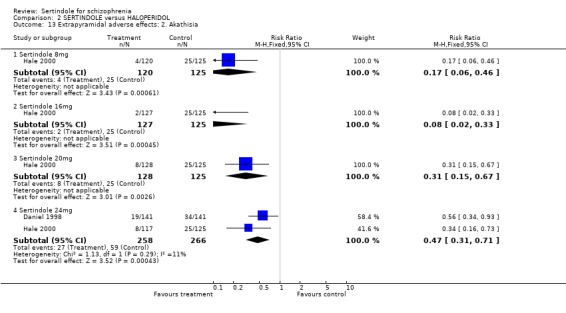

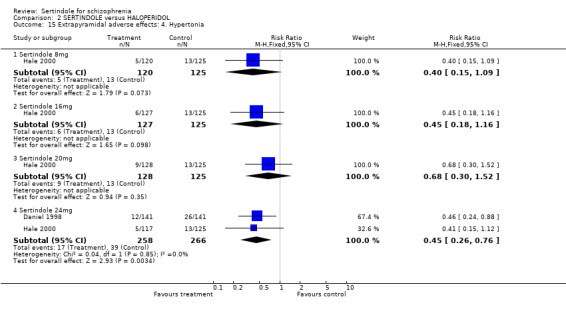

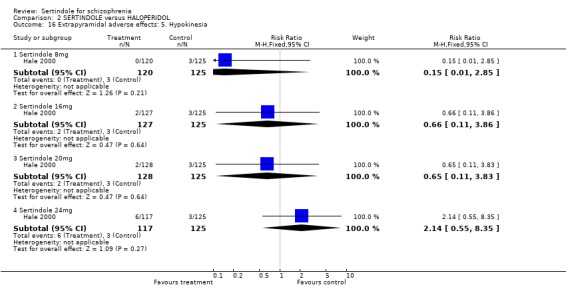

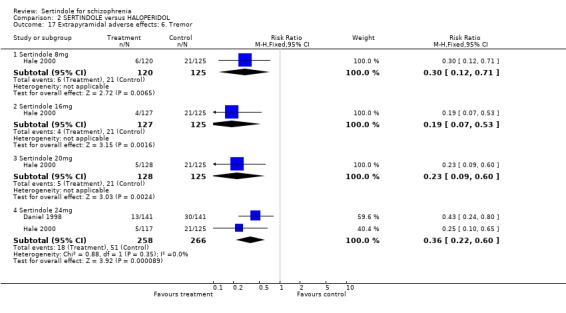

The incidence of EPS was higher among those treated with haloperidol than sertindole at 8, 16, 20 or 24mg/day (8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 11.4, CI 7.1 to 29.8; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.3, CI 0.1 to 1.0, NNH 15.5, CI 8.0 to 217.9; and 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.8, NNH 13.7, CI 7.7 to 68.3; 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 0.8, NNH 8.7, CI 5.4 to 23.0). More participants treated with haloperidol experienced akathisia, tremor and hypertonia than those treated with sertindole (Akathisia ‐ 8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.5, NNH 6.0, CI 4.1 to 11.2; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.3, NNH 5.4, CI 3.9 9.0; 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.3, CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNH 7.3, CI 4.6 to 17.9; 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.5, CI 0.3 to 0.7, NNH 8.6, CI 5.6 to 18.3. Tremor ‐ 8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.3, CI 0.1 to 0.7, NNH 8.5, CI 5.2 to 24.0; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.5, NNH 7.3, 4.8 to 15.6; 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.6, NNH 7.8, CI 4.9 to 18.1; 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.4, CI 0.2 to 0.6, NNH 8.2, CI 5.6 to 15.3. For Hypertonic ‐ 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.5, CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNH 12.4, CI 7.5 to 35.0; for sertindole 8, 16 and 20mg there was no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups).

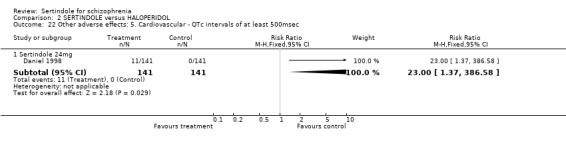

One study reported that at six weeks, there was a statistically significant greater increase from baseline to final value in mean QTc interval in the sertindole 16, 20 and 24mg groups (20, 26, and 24msec, respectively) than in the haloperidol group (0msec; p value was not reported), but no SD or any other measure of variance for the effect sizes were reported. For one long term study only one participant from the sertindole group (24mg) had a QT interval that exceeded 500msec (1 study, n=282, RR 3.0 CI 0.1 to 73.0), but 11participants treated with Sertindole had QTc intervals of at least 500msec, compared to none in the haloperidol treated group (1 study, n=282, RR 23.0, CI 1.4 to 386.6, NNH 12.8, CI 8.2 to 29.6).

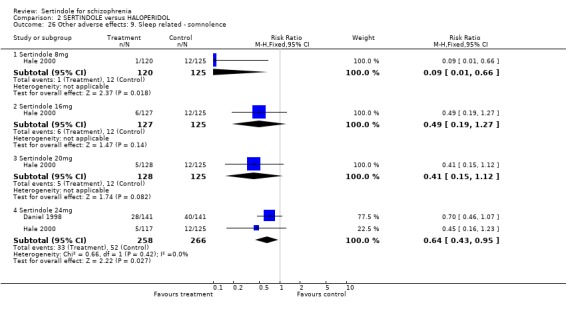

At six weeks, fewer participants treated with sertindole at 8mg or 24mg were affected by somnolence than those treated with haloperidol (sertindole 8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 11.4, CI 7.1 to 29.8; 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNH 14.8, CI 7.7 to 205.2).

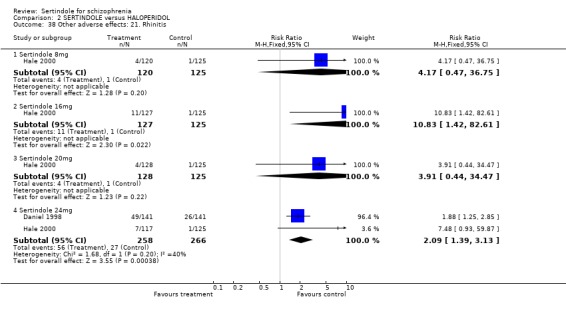

The incidence of rhinitis was found to be statistically significantly higher among those taking sertindole at 16 or 24mg as compared to haloperidol (16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 10.8, CI 1.4 to 82.6, NNH 12.7, CI 7.7 to 36.7; 24mg: 2 studies, n= 524, RR 2.1, CI 1.4 to 3.1, NNH 8.7, CI 5.6 to 18.6).

At one year, 33 participants treated with sertindole (24mg) had experienced the sexual adverse event of decreased ejaculatory volume, compared with six participants treated with haloperidol. However the number of included male participants was not reported and therefore the RR could not be calculated.

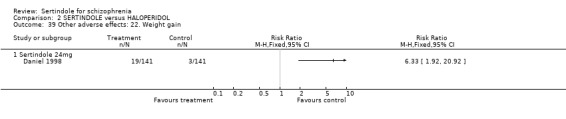

At one year, more participants taking sertindole (24mg/day) had put on weight compared to those taking haloperidol (1 study, n=282, RR 6.3, CI 1.9 to 20.9, NNH 8.8, CI 5.7 to 19.1). At six weeks, all of the sertindole groups showed an increase in body weight from baseline to final evaluation ranging from 1.3kg to 1.9kg, all of which represented a statistically significantly different weight change than that recorded for the haloperidol treatment group (‐0.1Kg). However, the actual weight gain for each sertindole dosage group was not reported and no SD or any other measure of variance was given.

Authors' conclusions

Sertindole at a dose of 20mg/day was found to be more antipsychotic than placebo. When used at 8, 12 or 20mg/day it appears to be as acceptable as placebo (in terms of various adverse events including movement disorders and somnolence), but seems to be associated with more cardiac problems (8, 12 or 20mg/day) and an increase in weight gain (20mg/day) than placebo.

Sertindole at a dose of 24mg/day was better tolerated than haloperidol (in terms of participants leaving the study early). It was also found to be was associated with fewer movement disorders (at 8, 16, 20 or 24mg/day) and sedation (8 or 24mg/day) than haloperidol. However, it was shown to cause more cardiac anomalies (16, 20 or 24mg/day), weight gain (all doses combined), rhinitis (16 or 24mg/day), and problems with sexual functioning (24mg/day) than haloperidol. One short term study reported that sertindole 16mg/day was the most optimal dose.

Plain language summary

Sertindole for schizophrenia

This review includes three studies with a total of 1104 participants. We excluded two large important studies because they did not report any usable data. The three that were included suggested that sertindole (20 mg/day) was more antipsychotic than placebo, as acceptable as placebo (in terms of various adverse events including movement disorders and somnolence) and better tolerated than haloperidol. Sertindole was associated with fewer movement disorders than haloperidol, but was shown to cause more weight gain and the possible side effect of male sexual dysfunction. Cardiac problems (QTc intervals of at least 500 msec) were evident even in the randomised trials. Sertindole used at 16 mg/day (reported to be the most optimal dose by one study) caused more rhinitis than haloperidol.

Background

In treating people with schizophrenia, choosing the most appropriate, effective and tolerable antipsychotic drug is a key to maximising the usefulness of medication. The main choice is between conventional (usually known as 'typical') agents and the newer 'atypical' agents. According to recent treatment guidelines, both classes of antipsychotic drugs may be reasonable choices in the treatment of schizophrenia (APA 1997, RCP 1999).

Typical antipsychotic drugs such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine and trifluoperazine are widely used as the first line treatment for people with schizophrenia, in the acute as well as in chronic forms of the illness (APA 1997, Silverstone 1995). However, the atypical class of antipsychotic drugs, most of which have been formulated relatively recently, are making important inroads into this traditional approach (Adams 1999, Wood 1998).

'Atypical' is a widely used term for describing some antipsychotics which have a low propensity to produce movement disorders, sedation and raised serum prolactin (Kerwin 1994). There is some suggestion that the different adverse effect profiles of atypical antipsychotic groups make them more acceptable to people with schizophrenia (Casey 1997). Certainly the adverse effects of the typical drugs, such as movement disorders and sedation, are problematic and can result in poor compliance with treatment (CWG 1998).

Although the positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking) of schizophrenia are responsive to both the typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs it is believed that negative symptoms (poverty of speech, lack of motivation, apathy and inability to express emotions ‐ Carpenter 1994), which are very disabling, may respond better to atypical antipsychotic drugs (APA 1997, Silverstone 1995), although this has not yet been adequately established (Kane 1996).

Atypical antipsychotics are more expensive than conventional drugs (Meltzer 1996), but it has been suggested that if they do indeed reduce a person's need for inpatient services their use would result in a net reduction of costs (Buckley 1997, Glazer 1997).

Sertindole (Serdolect) is an atypical antipsychotic agent that was discovered and patented by H Lundbeck (Copenhagen, Denmark). It was approved in the UK in 1996 and by 1997 sertindole had been approved in 23 countries and marketed in 17 countries. However, the potential of sertindole to prolong the QTc interval, an abnormality of cardiac electrical conduction associated with cardiac arrhythmias, was well recognised and warnings relating to this were included in product information. It was also recommended that an ECG be performed before commencing treatment with sertindole to establish the patient's baseline QT interval (Lundbeck Ltd. 1997).

By the end of November 1998, the Committee on Safety of Medicines and the Medicines Control Agency (MCA) had been notified of 36 suspected adverse drug reactions with a fatal outcome. In addition, 13 reports of serious but non‐fatal cardiac arrhythmia were reported in the UK across the same time period. However, not all of these reports related to sudden cardiac deaths, and in many cases other medical conditions may have been an important contributory factor.

Based on these findings it was considered that risks of sertindole therapy outweighed the potential benefits. In order to fully investigate the safety concerns, Lundbeck Ltd, the manufacturers of sertindole, voluntarily suspended its marketing and use from 02 December 1998. The availability of sertindole was therefore suspended pending a full evaluation of its risks and benefits in collaboration with the UK MCA and other European regulatory authorities.

In June 2001, the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) appointed an ad hoc expert group to study and give advice on the preclinical and epidemiological evidence for sertindole. The recommendation of the expert group, to lift the suspension, was adopted by the CPMP in October 2001, and was ratified by the European Commission on the 26 June 2002. Lundbeck have committed to the CPMP to carry out two post‐marketing surveillance (PMS) studies to provide additional epidemiological data under conditions of normal drug usage. The PMS studies were initiated in July 2002 and will include all patients taking sertindole. Initial marketing of the product will be restricted. Lundbeck is currently in discussions with the US health authorities (FDA) to investigate whether, and if so when, it would be possible to launch Serdolect in the US market.

Technical background Sertindole is a phenylindole derivative (1‐[2‐[4‐[5‐chloro‐1‐(4‐fluorophenyl)‐1H‐indol‐3‐yl]‐1‐piperidinyl] ethyl‐2‐imidazolidinone) which is manufactured by Lundbeck Ltd. and was sold as Serdolect or Serlect (in several European countries) in 4mg, 12mg, 16mg and 20mg tablets. It is a long acting 5‐HT2 / alpha1 antagonist and a very mild D2 antagonist.

Objectives

To determine the clinical effects and safety of sertindole compared with placebo, typical and other 'atypical' antipsychotics used to treat schizophrenia and related psychoses.

As secondary objectives, it was proposed to investigate whether: 1. People with schizophrenia described as 'treatment resistant' differed in their response from those whose illness was not designated as such; 2. People having predominantly positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia were more responsive to sertindole than those without this designation; and 3. People experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia differed in their response from those at a later stage of their illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We did not include quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included people with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, however diagnosed. We also included those with schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder or 'psychotic illness' . If possible we excluded people with dementing illnesses, depression and primary problems associated with substance misuse.

Types of interventions

1. Sertindole (any dose) 2. Placebo 3. Any other antipsychotic agent, divided into the atypical (amisulpride, sulpiride, clozapine, loxapine, molindone, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, zotepine) and the typical antipsychotics.

Types of outcome measures

1. Death ‐ suicide or natural causes.

2. Leaving the study early.

3. Clinical response: 3.1 clinically significant responses in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.2 average score/change in global state 3.3 clinically significant responses in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.4 average score/change in mental state 3.5 clinically significant responses on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.6 average score/change in positive symptoms 3.7 clinically significant response on negative symptoms‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.8 average score/change in negative symptoms.

4. Extrapyramidal side effects (or movement disorders): 4.1 incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 4.2 clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects.

5. Other adverse effects, general and specific.

6. Service utilization outcomes: 6.1 hospital admission 6.2 days in hospital 6.3 change in hospital status.

7. Economic outcomes.

8. Quality of life/ satisfaction with care for either recipients or carers measured by directly asking participants: 8.1 significant change as defined by each of the studies 8.2 average score/change in quality of life/ satisfaction.

All outcomes were summarised for the short term (up to six weeks), medium term (7‐26 weeks) and long term (more than 26 weeks).

Search methods for identification of studies

The initial search strategy included the following:

Electronic searches

1. We searched biological Abstracts (Jan 1980 ‐ Feb 1999) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

2. We searched Centerwatch Clinical Trials Listing (http://www.centerwatch.com/main.htm ‐ accessed 25/8/2000) using the phrase:

[sertindole or serdolect or serlect]

3. We searched The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 1999) using the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

4. We searched The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (August 2000) using the phrase:

[sertindole or serdolect or serlect]

5. We searched Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ ‐ accessed 25/8/2000) using the phrase:

[sertindole or serdolect or serlect]

6. We searched EMBASE (January 1980 ‐ February 1999) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect or explode "SERTINDOLE"/ all subheadings)]

7. We searched LILACS (January 1982 ‐ February 1996) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

8. We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 ‐ February 1999) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

9. We searched the National Institutes of Health Clinical Studies (http://clinicalstudies.info.nih.gov/index.html ‐ accessed 25/8/2000) with the phrase:

[sertindole or serdolect or serlect]

10. We searched the National Research Register (Issue 3, 2000) using the phrase:

[sertindole or serdolect or serlect]

11. We searched PsycLIT (January 1974 ‐ January 1999) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

12. We searched PSYNDEX (January 1977 ‐ February 1995) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both RCTs and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (sertindole or serdolect or serlect)]

13. We undertook specific searches for RCTs of sertindole in the following databases:

Pharmaceutical databases available on the Dialog Corporation Datastar service: ADIS Inpharma (indexes 2000 international medical & biomedical journals); ADIS LMS drug alerts (indexes 2,300 international medical & biomedical journals); IDIS Drug File (indexes 140 English language medical journals); PharmLine (indexes 100 journals in drugs and professional pharmacy); Pharma Marketing Service (indexes 200 international journals and other non‐journal publications)

Pharmaceutical databases available on the Dialog Corporation Dialog service: CAB Health (international coverage of health journal and non‐journal material); Conference Papers Index; Derwent Drug File; Dissertation Abstracts; Extramed; Federal Research in Progress (US federally funded research); International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (indexes 800 pharmaceutical and medical journals); JICST‐EPLus (Japanese Science and Technology); Mental Health Abstracts; NTIS (National Technical Information Service); Pascal; Pharmaprojects; USP‐DI ‐ Drug information for the health care professional

We used the following schizophrenia search terms: schizo$ psychotic$ psychoses psychosis ((chronic$ or sever$) near2 mental$) near2 (ill$ or disorder$)

combined with the following RCT search terms: trial$ random$ (singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) near (blind$ or mask$) placebo or standard adj treatment study or studies rct$ crossover$ control or controlled or controls

and the phrase: [and (sertindole or serdolect or serelect)]

We updated the literature search reported above during 2003 with the following search:

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (April 2003) using the phrase:

(sertindole* or serdolect* or serlect* in title, or *sertindole* or *serdolect* or *serlect* in abstract, index or title terms of REFERENCE] or [Sertindole* in interventions of STUDY]}

The Schizophrenia Groups trials register is based on regular searches of BIOSIS Inside; CENTRAL; CINAHL; EMBASE; MEDLINE and PsycINFO; the hand searching of relevant journals and conference proceedings, and searches of several key grey literature sources. A full description is given in the Group's module.

Searching other resources

1. We carried out citation searches on key authors.

2. Reference lists We searched all references of articles selected for further relevant trials.

3. Authors of studies We contacted authors of studies when necessary to clarify data and enquire about additional studies.

4. Pharmaceutical company We contacted Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals to obtain data on unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials We independently inspected the citations identified in the search outlined above. We identified potentially relevant abstracts and ordered full papers and reassessed these for inclusion and methodological quality. Any disagreement was discussed and resolved, if necessary by a third reviewer.

2. Assessment of quality We allocated trials to three quality categories, as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Mulrow 1997), again working independently. When disputes arose as to which category a trial was allocated, again, we attempted resolution by discussion. We only included those trials in Category A or B in the review.

3. Data management 3.1 Data extraction We (RL, AMB) performed this independently, and where further clarification was needed the we contacted the authors of trials to provide missing data. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion.

3.2 Intention to treat analysis (ITT) We excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up (this does not include the outcome of 'leaving the study early').

Where feasible (i.e. for dichotomous outcomes), we considered people leaving early to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of death. However, the authors of included studies reported that they used 'the last observational carried forward' method for their ITT analyses of rating scales (continuous outcomes), which did not include all recruited participants (see Table of Characteristics of included studies for details of which participants were included in these analyses).

Due to the small number of included studies we did not perform any sensitivity analyses.

4. Data analysis We pooled studies using the fixed effects model.

4.1 Binary data For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). We also calculated he number needed to treat statistic (NNT) and the number needed to harm statistic (NNH) in case of significant results.

4.2 Continuous data 4.2.1 Skewed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data it was decided a‐priori that the following standards would be applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations (SDs) and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from a finite number (such as zero), the SD, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996). Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and this rule can be applied to them. However, for scales which start at values higher than zero (such as the BPRS and the PANNS) this rule was modified to take into account the scale's starting point. In these cases skewness was considered to be present if the SD multiplied by two was greater than S‐Smin, where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum sore.

Because the statistics used in MetaView are quite robust towards skewness non‐normally distributed data have been presented under 'Other data' (rather than not being reported).

4.2.2 Summary statistic: for continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups.

4.2.3 Valid scales: we only included continuous data from rating scales if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal and the instrument used self report or was completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist).

4.2.4 Endpoint versus change data: where possible we presented endpoint data. If both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcomes then we only reported the former in this review.

5. Test for heterogeneity A chi‐square test was used, as well as visual inspection of graphs, to investigate the possibility of heterogeneity. We interpreted a significance level less than 0.10 as evidence of heterogeneity.

6. Addressing publication bias There were insufficient included studies to produce a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias (Egger 1997).

7. Sensitivity analyses We had hoped to investigate whether there were differences between:

·People with schizophrenia described as 'treatment resistant' and those whose illness was not designated as such;

·People having predominantly positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia and those without this designation; and

·People experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia and those at a later stage of their illness.

However, there were insufficient data to enable us to do this.

8. General Where possible we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for sertindole.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of studies please see 'Included and excluded studies' tables.

1. Excluded studies We excluded twenty‐two studies (53 references). We excluded two important studies (Potkin 1994, Zimbroff 1997) due to having greater than 50% loss to follow‐up. Potentially therefore, the only outcome that we could have included was 'leaving the study early'. Unfortunately, it was not possible to use this data as it was not specified to which treatment group the participants who left the study early had been allocated. We incldued a further eight studies because they were reviews (which included one abstract) and one was a discussion paper. Three studies were not reported to have been randomised, five did not have a comparison group and one was a case history. The final three studies included two that reported an outcome that was not within the scope of this review (PET scans) and one that discussed the use of a PATH analysis for two randomised trials, but did not present the results. Both these references were conference abstracts and we included the two trials that were referred to in the PATH analysis in the review.

2. Awaiting assessment There are three studies awaiting assessment, all of which were presented as conference abstracts only and there is insufficient information available to include them in their present format (Azorin, 2002, Martin 1994, McEvoy 1993). One study was a randomised controlled trial of sertindole (n=97) versus risperidone (n=89) for people with treatment resistant schizophrenia (Azorin, 2002). The study was originally designed to include 360 patients, but was prematurely terminated when sertindole was suspended.

3. Ongoing studies No ongoing studies have been identified.

4. Included studies We identified three studies for inclusion in the review (Daniel 1998, Hale 2000, Van Kammen 1996). All were randomised and double blind. Two studies were reported to have been sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, (Daniel 1998, Van Kammen 1996) and all three had a drug company employee as a named author.

4.1 Length of trials Two studies (Hale 2000, Van Kammen 1996) were of short to medium duration (six and eight weeks respectively), and one (Daniel 1998) was a comparatively long term study, lasting one year.

4.2 Participants All three studies included participants who met the operationalised diagnosis of schizophrenia by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (APA 1997) criteria.

Van Kammen 1996 only included people who had active psychosis of at least moderate severity (combination score of at least eight on any two of the positive symptoms of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)). The study also only included those who had a history of previous response to antipsychotic drugs.

Hale 2000 included participants who required hospitalisation and had a score greater than two for at least two of the following Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) items: conceptual disorganisation, hallucinatory behaviour, suspiciousness, unusual thought content, and less than three for all items on Simpson‐Angus scale and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). The mean number of days since hospitalisation for the five treatment groups were: sertindole 8mg 100days; sertindole 16mg 130 days; sertindole 20mg 169 days; sertindole 24mg 154 days; and haloperidol 10mg 148 days.

Daniel 1998 only included participants with a positive response to a neuroleptic agent (excluding clozapine) in the five years before the study. They enrolled stable outpatients with moderate illness defined by a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (part 1) score of four or less.

Two studies (Daniel 1998, Van Kammen 1996) were reported to have excluded individuals with tardive dyskinesia as measured on the AIMS. Hale 2000 reported excluding non‐responders to any antipsychotic agent within the preceding five years or participants with a decrease in PANSS score greater than or equal to 20 over a seven day placebo run in period.

None of the studies were noted to have included participants with treatment resistant schizophrenia, or those with predominantly negative or positive symptoms. In addition, none of the included studies looked at participants who were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia.

4.3 Setting Two studies (Hale 2000, Van Kammen 1996) included participants that were in hospital and one study (Daniel 1998) recruited subjects that were attending outpatients.

4.4 Study size Hale 2000 was the largest study with 617 participants (divided into five treatment groups), Daniel 1998 had 282 (two treatment groups) and Van Kammen 1996 205 (four treatment groups). Only one study (Daniel 1998) reported a power calculation, the results of which showed that their sample size was too small (recommended sample size was 150 participants in each treatment group).

4.5 Interventions Hale 2000 examined four different doses of sertindole (ranging from 8 to 24mg/day), Van Kammen 1996 investigated three different doses (ranging from 8 to 20mg/day) and Daniel 1998 used 24mg/day. One study (Van Kammen 1996) used placebo as the comparison drug and two studies (Daniel 1998, Hale 2000) used haloperidol at 10mg/day.

4.6 Outcomes 4.6.1 Death None of the included studies looked at death, either due to suicide or natural causes as an outcome measure. However, one study did report some data on suicidal tendency and suicidal attempt (Hale 2000).

4.6.2 Leaving study early All three studies report data on the outcome leaving the study early.

4.6.3 Clinical improvement: as defined by individual studies Only two studies (Hale 2000, Van Kammen 1996) reported data on this outcome. Hale 2000 evaluated treatment group differences in the percentage of responders as determined by the PANSS total score (40‐50% improvement) and CGI score (at least very much improved) at the final evaluation, but the actual results of the latter analysis were not presented. Van Kammen 1996, defined a responder for PANSS and BPRS as a 10%, 20%, 30%, and 50% improvement from baseline to final evaluation, and for CGI a responder was defined as very much improved, at least much improved, and at least minimally improved from baseline. Only data on the outcome 'very much improved' for the sertindole 20mg and placebo treatment groups were presented.

4.6.4 Continuous data Details of the scales that were used by the included studies are shown below. Reasons for exclusion of data from other instruments are given under 'outcomes' in the 'included studies' section. It was not stated how the instruments were completed in all three studies.

a. Global state Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ CGI Scale (Guy 1976) This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement.

b. Mental state Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1986) This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from 0‐6 or 1‐7. Scores can range from 18‐126 or 0‐108, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Positive and negative syndrome scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1987) This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from one ‐ absent to seven ‐ extreme. This scale can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1984) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia, affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

c. Side effects Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale ‐ AIMS (Guy 1976) This is a 40‐item scale. It has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long‐term, drug‐induced movement disorder. The AIMS can be used to assess some short‐term movement disorders such as tremor.

Barnes Akathisia Scale ‐ BAS (Barnes 1989) The scale comprises of items rating the observable, restless movements that characterise akathisia, a subjective awareness of restlessness, and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from zero ‐ normal to three ‐ severe. In addition, there is an item for rating global severity (from zero ‐ absent to five ‐ severe). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia.

COSTART Terms (COSTART 1990) This is a list drawn up by the US Food and Drug Administration in order to help consistent description of adverse reaction. It is not a scoring system.

Simpson Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) This ten‐item scale with a scoring system of 0‐4 for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short‐term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

4.6.5 Side effects All three studies collected data on the use of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) medication and measured the incidence of EPS related adverse events as well as using specific movement rating scales. All studies also coded adverse events according to the Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms (COSTART) III dictionary.

4.6.6 Economic outcomes Only one study (Daniel 1998) reported data on service utilisation. No other economic outcomes were reported.

4.6.7 Missing outcomes None of the trials focused on clinically relevant outcomes such as 'the quality of daily functioning', 'employment', 'trouble with the police' and 'satisfaction with care'.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomisation All three studies fell into category B as the method of randomisation was not stated. It can not therefore be assured that the introduction of biases was minimised at this crucial stage. It has been shown that the quality of reporting of randomisation can influence the odds of presenting 'significant' outcomes (Chalmers 1983, Moher 1998, Schulz 1995, Verhagen 1999).

Blinding to interventions and outcomes In one study (Hale 2000), trial medication was reported to have been administered in a double‐dummy fashion with all participants receiving three capsules and two tablets a day (i.e. randomised treatment and matching placebo). The remaining two studies were reported to be double blind, but neither described the blinding process in detail.

Follow‐up One study (Daniel 1998) had more than 75% of the participants completing the study and a second had 61% (Hale 2000). Van Kammen 1996 (a placebo controlled trial), on the other hand, had 49% loss to follow up. Once participants leave a study, unless the trialists continue to follow and collect data on them, assumptions have to be made about outcome. All three studies stated that they analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis using the last observation carried forward (see Methods of the review, ITT analyses). This practice may well overestimate the treatment effect. In the review, where feasible, we considered those leaving the studies early to have had a 'bad outcome' and analysed them accordingly. Whatever the management of lost data, interpretation of results with large degrees of attrition must be undertaken with caution.

Effects of interventions

COMPARISON 1. SERTINDOLE versus PLACEBO

Only one included trial compared the use of sertindole with placebo (Van Kammen 1996). Therefore all the following results are based on a single trial.

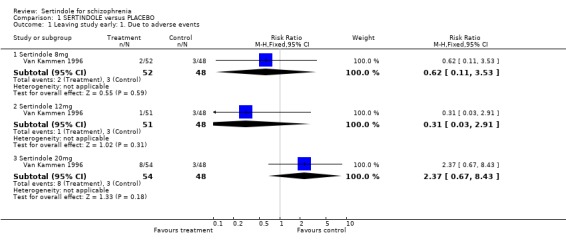

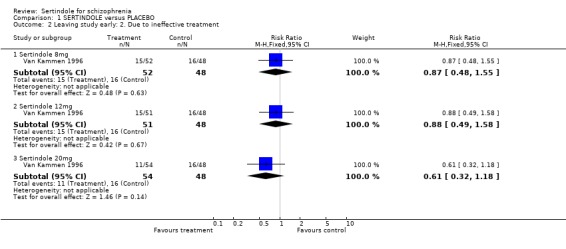

1. Leaving the study early There was no statistically significant difference between the sertindole and placebo groups in terms of the number of participants leaving the study early. The percentage of participants leaving the study early due to adverse events was 7% (11/157; 8mg 4%, 12mg 2%, 20mg 15%) in the sertindole group and 6% (3/48) in the placebo group. The percentage of people leaving due to ineffective treatment was 26% (41/157; 8mg 29%, 12mg 29%, 20mg 20%) in the sertindole group and 33% (16/48) in the placebo group.

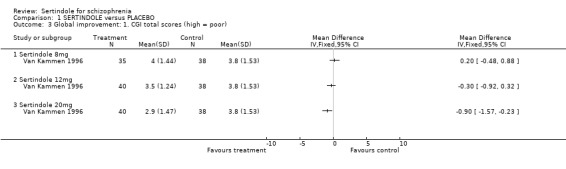

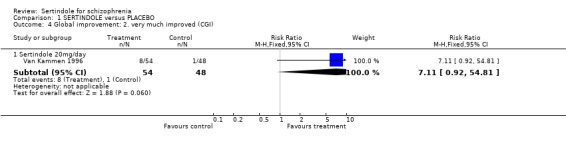

2. Clinical response 2.1. Global effect CGI total end point scores, at six weeks, for three different doses of sertindole (8, 12 or 20mg/day) were reported. The findings showed skewed data for the 20mg sertindole group. The positive skewness was minimal and therefore a decision was made to deviate from the protocol. When these data were included in the analyses, the average difference, for the 20mg sertindole group showed a statistically significant decline in favour of sertindole as compared to placebo (1 study, n=78, MD ‐0.9, CI ‐1.6 to ‐0.2). For the 12mg sertindole group the average difference showed a decline in favour of the sertindole group (1 study, n=78, MD ‐0.3, CI ‐0.9 to 0.3) and for the 8mg group there was a decline in favour of the placebo group (1 study, n=73, MD 0.2 , CI ‐0.5 to 0.9) . However, the difference between sertindole and placebo, for both doses of 8mg and 12mg, was not found to be statistically significant. Some results on improvement according to CGI were also reported by the placebo controlled trial. A marginally statistically significantly greater number of participants (n=8/54) that were treated with 20mg of sertindole were reported to have been 'very much improved' as compared to those taking placebo (n=1/48) (1 study, n=102, RR 7.6, CI 1.0 to 57.9, NNT 7.9, CI 4.3 to 41.1). Information relating to the doses of either 8mg or 12mg of sertindole was not reported.

2.2. Mental state For BPRS, sertindole at 20mg/day was found to be statistically significantly more effective than placebo (1 study, n=78, MD ‐6.2, CI ‐11.8 to ‐0.6). Doses of 8mg and 12mg, however, were not found to be significantly better than placebo (8mg: 1 study, n= 73, MD 0.8, CI ‐4.6 to 6.2; 1 study, 12mg: 1 study, n=78, MD ‐2.2, CI ‐7.8 to 3.4). When reporting total PANSS scores, no significant difference was found between sertindole, at any dose, and placebo (20mg: 1 study, n=78, MD ‐9.5, CI ‐19.2 to 0.2; 8mg: 1 study, n=73 MD 2.8, CI. ‐6.8 to 12.4; 12mg: 1 study, n=78, MD ‐4.8, CI ‐14.5 to 4.9). Mean change data on PANSS broken down for the positive and negative symptoms scales were also reported, but no SD or any other measure of variance were reported and as such the MD between placebo and sertindole groups could not be calculated (see Data Analysis, under Methods of the Review). The mean change for the placebo group was ‐1.6 points for the positive scale and ‐1.3 for the negative scale. Comparable mean change for the sertindole 8mg group was ‐1.6 and ‐0.2, respectively. In the sertindole 12mg group they were ‐3.0 and ‐2.1, and in sertindole 20mg group they were ‐3.5 and ‐3.0. 3. Extrapyramidal adverse effects The study reported on the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms and use of medication to avoid extrapyramidal symptoms; the results of which showed no statistically significant differences between the sertindole and placebo groups.

Data were reported for the BAS, SAS and AIMS endpoint scores for three different doses of sertindole (8mg, 12mg, 20mg). However, the findings showed the data to be skewed and the results are therefore presented in the 'Other data' tables.

There were no statistically significant differences found between sertindole (8, 12 or 20mg) and placebo for the outcomes of akathisia, cogwheel rigidity, hypertonia and tremor. However, the data for these outcomes were taken from a separate publication, where the number of participants with either akathisia, hypertonia or tremor in the sertindole 8mg group (n=5/52) does not correspond with the data reported in the main publication for this study, where it was reported that 2/52 participants treated with sertindole at 8mg/day experienced extrapyramidal symptoms.

4. Other adverse effects 4.1. Cardiovascular problems Observed differences between sertindole and placebo with regard to ECG findings and heart rate were reported. Statistically significant difference in mean change from baseline (the authors did not report the p value), in the QT and QTc intervals, were observed between the placebo and all sertindole groups (8, 12 and 20mg). This was also true of heart rate differences between placebo and the 20mg sertindole group. Mean baseline ranges in the sertindole dose groups were: QT=355.3‐359.5ms, QTc=392.7‐395.6ms, and heart rate=80.2‐83.3bpm. The final values in the sertindole groups during the study were: QT=369.6‐373.1ms, QTc=408.8‐417.4ms, and heart rate=83.3‐85.8bpm. Mean baseline values in the placebo group were QT=361.5+/‐22.71ms, QTc=396.7+/‐18.53ms, and heart rate=80.3+/‐11.57. The final mean values in the placebo group during the study were QT=362.2+/‐23.67ms, QTc=394+/‐17.13ms, and heart rate=79.0+/‐12.5bpm. However, as the authors did not provide the SD, we could not calculate the WMD.

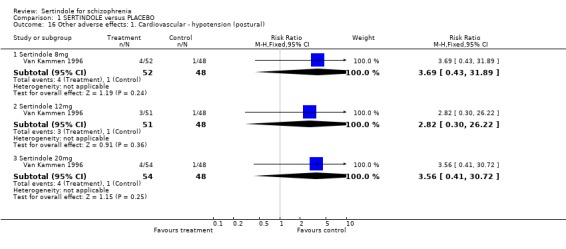

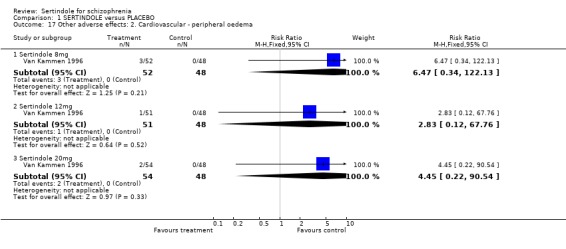

There was no statistically significant difference found between participants taking sertindole (8, 12 or 20mg) and those in the placebo group for the incidence of either postural hypotension or peripheral oedema.

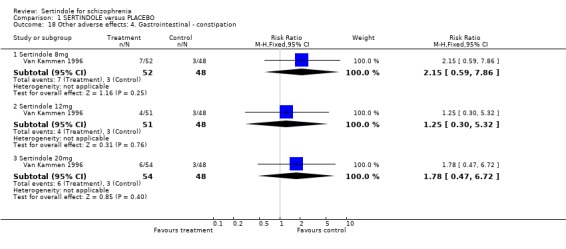

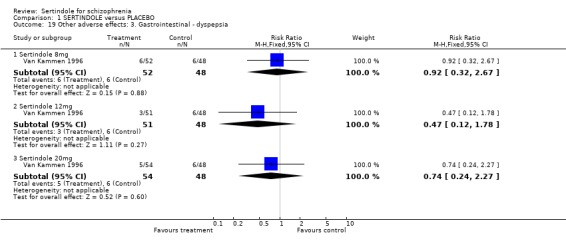

4.2. Gastrointestinal problems There was no statistically significant difference between sertindole and placebo for the outcome of constipation or dyspepsia.

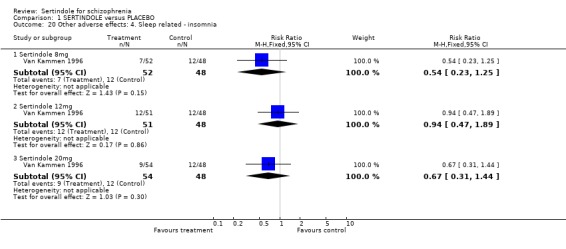

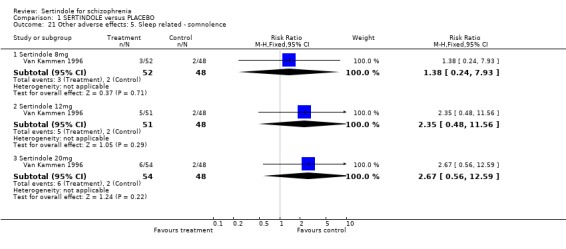

4.3. Sleep problems There was no statistically significant difference between sertindole and placebo for the outcomes insomnia and somnolence.

4.4. Weight changes There was a greater mean weight gain among participants taking sertindole as compared to placebo, with a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the 20mg sertindole (mean weight gain of 3.3kg) and placebo (mean weight gain of 0.8kg). However, the SD was not reported, which means that the WMD could not be calculated.

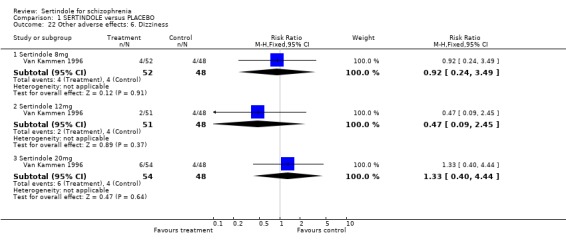

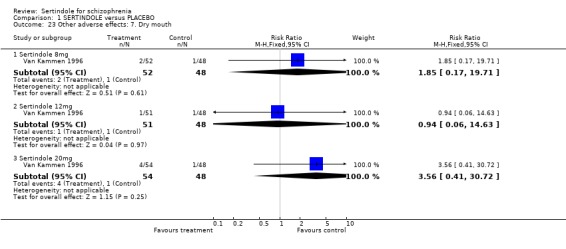

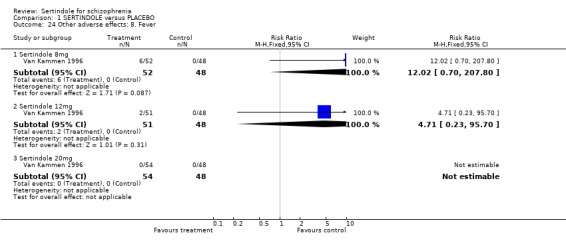

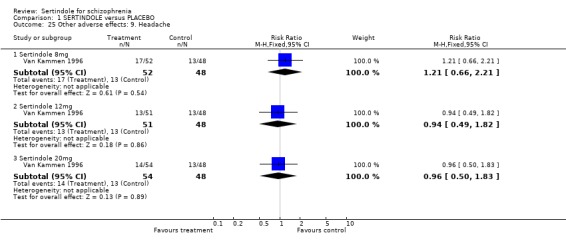

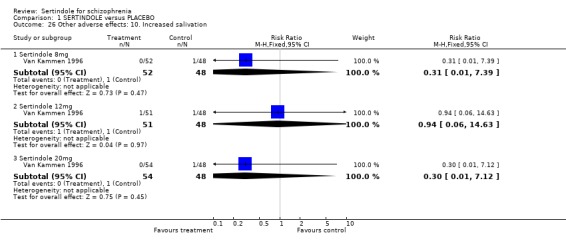

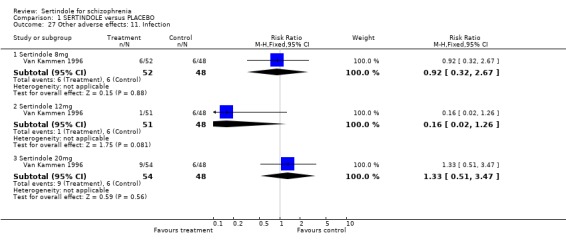

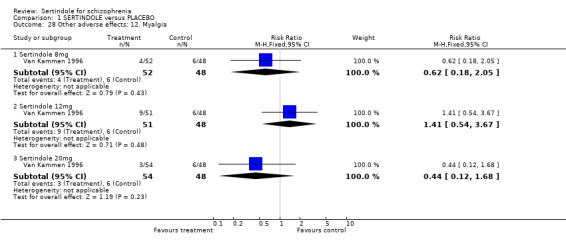

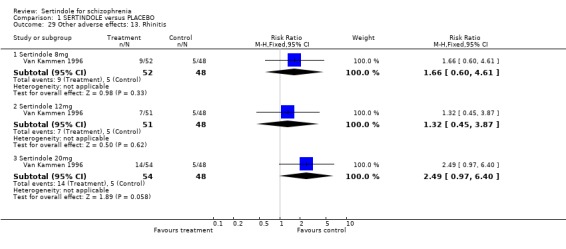

4.5. Other problems The incidence of rhinitis was marginally statistically significantly higher in the sertindole 20mg group than placebo (1 study, n=102, RR 2.5, CI 1.0 to 6.4), but there was no statistically significant difference between sertindole at 8 or 12mg/day and placebo. There was no clear difference between sertindole and placebo for the outcomes of dizziness, dry mouth, fever, headache, increased salivation, infection and myalgia.

Data were reported for the number of participants who had abnormal ejaculation, but the exact number of male participants, was not reported (˜95%) and therefore the RR could not be calculated. Only one patient who received placebo had abnormal ejaculation compared with one in the sertindole 8mg group, four in the 12mg group, and nine in the 20mg group (p<0.05).

5. Missing outcomes The included study did not examine death as an outcome measure, nor did it report on service utilisation, economic outcomes, quality of life or satisfaction with care. The long term effects of sertindole were not evaluated.

COMPARISON 2. SERTINDOLE versus HALOPERIDOL

Two studies compared the use of sertindole to haloperidol (10mg/day; Daniel 1998, Hale 2000). One was a short term study (six weeks) that examined four different doses of sertindole (8, 16, 20 or 24mg /day) and one was a long term study (one year) that used sertindole at 24 mg/day.

1. Death One study (Hale 2000) reported that the most common serious adverse events were suicidal tendency (n=4) and suicidal attempt (n=4). However, the authors did not report which dose of sertindole these participants were taking and it was unclear as to whether the incidence was zero in the haloperidol group.

Neither study reported data on death due to natural causes nor those related to taking sertindole.

2. Leaving the study early

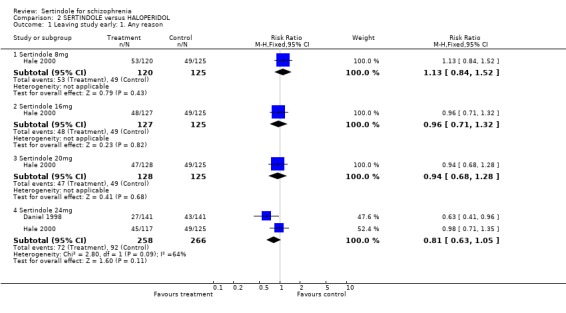

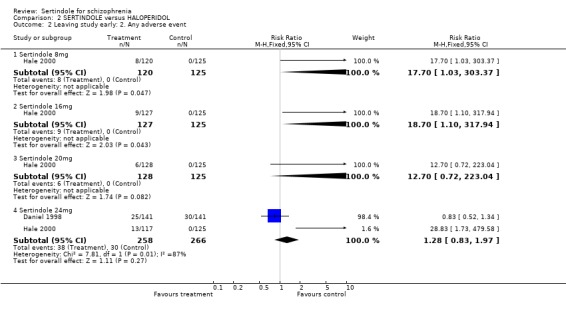

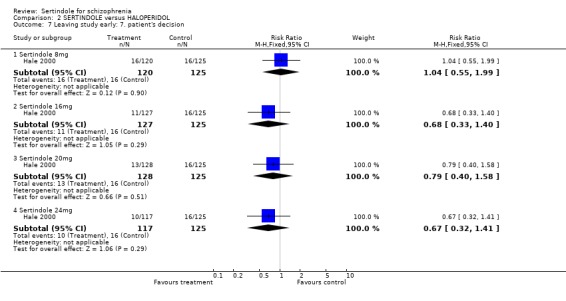

When considering the overall findings from the two studies for discontinuation due to any reason (for sertindole 24mg) there was statistically significant heterogeneity between the studies (p=0.09). This is not surprising bearing in mind that both studies differed in their length of follow‐up(Daniel 1998 one‐year, Hale 2000 six weeks); and in terms of recruited participants (Daniel 1998 included those in outpatients settings and Hale 2000 included those in hospital settings). When considering the findings of the two studies individually, Daniel 1998 found a statistically significantly greater number of participants leaving the study due to any reason in the haloperidol group than in the sertindole group (1 study, n=282, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNH 8.8, CI 4.7 to 74.0) and Hale 2000 found no statistically significant difference between the two groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups when examining 8mg, 16mg or 20 mg of sertindole, according to one study (Hale 2000). Both studies reported on the outcome leaving the study early due to any adverse event, however, once again there was statistically significant heterogeneity between the two studies. In Daniel 1998, 25 participants (18%) treated with sertindole (24mg) discontinued treatment compared to 30 participants (21%) in the haloperidol group. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. In the second study (Hale 2000), according to one publication, no participants discontinued treatment in the haloperidol group because of adverse events compared to 36 treated with sertindole (sertindole 8mg n=8; sertindole 16mg n=9; sertindole 20mg n=6; sertindole 24mg n=13). The difference between the two interventions was statistically significant for sertindole 8 and 16mg (but with very wide confident intervals). However, according to a second article (reporting adverse events data for the same study) published in the same journal, nine patients receiving haloperidol discontinued treatment due to adverse events compared to 35 participants taking sertindole (sertindole 8mg n=8; sertindole 16mg n=8; sertindole 20mg n=6; sertindole 24mg n=13), Which would result in a non statistically significant difference between the intervention groups for all sertindole dosages. This means that the results presented in the figures (although found to be statistically significant) are unreliable. Because of this (as well as the presence of statistically significant heterogeneity) the results of the two studies have not been pooled.

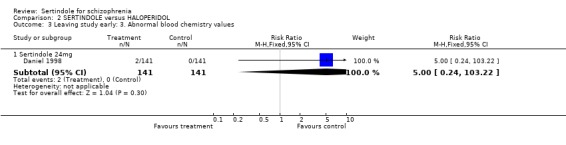

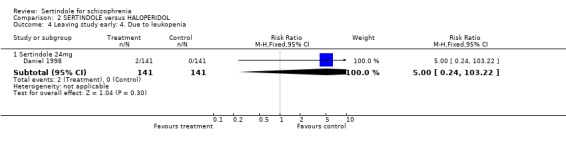

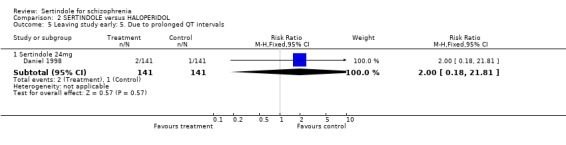

In one study (Daniel 1998), two participants were reported to have discontinued treatment due to abnormal blood chemistry (both treated with sertindole: one had elevated SGPT/ALT and one had elevated glucose without a known history of diabetes mellitus), two participants (both in the sertindole group) discontinued treatment due to leukopenia and three because of prolonged QT intervals (two in the sertindole group and one in the haloperidol group). The same study also reported that significantly more sertindole treated participants discontinued their medication because of decreased ejaculatory volume (9% sertindole versus 0% haloperidol), but these results were only reported as percentages for which the denominators were not reported and therefore the RR could not be calculated.

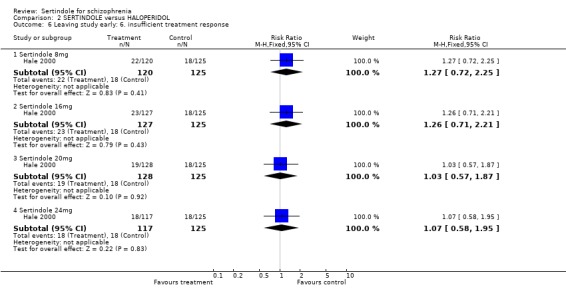

Hale 2000 reported on participants who withdrew from the study due to unacceptable treatment response or the patient's decision to leave, for which there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups for any of the sertindole dosage levels (8, 16, 20 or 24mg). Eighty‐two (17%) out of 492 participants treated with sertindole discontinued due to unacceptable treatment response and 50 (10%) due to the patients' decision, compared to 18 (14%) and 16 (13%), respectively, in the haloperidol group (n=125).

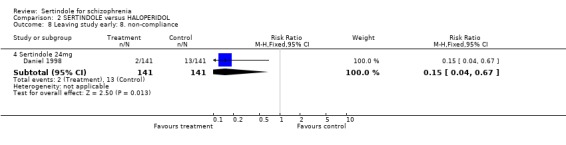

Daniel 1998 reported on the outcome leaving the study early due to non‐compliance which was found to be statistically significantly higher among participants who were on haloperidol (13/141) as compared to those in the sertindole treated group (2/141) (1 study, n=282, RR 0.2, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 12.8, CI 7.7 to 37.8).

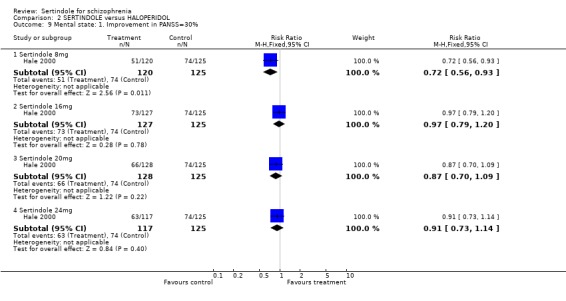

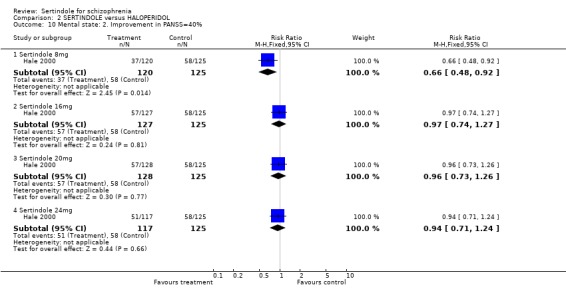

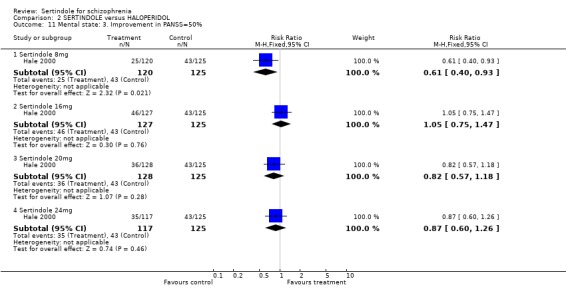

3. Clinical response: Global effect and mental state Hale 2000 reported the number of participants with at least 30, 40 or 50% improvement in PANSS score. There were statistically significantly more haloperidol treated participants with a 30% (1 study, n=245, RR 0.7, CI 0.6 to 0.9, NNT 6.0, CI 3.4 to 33.0), 40% (1 study, n=245, RR 0.7, CI 0.5 to 0.9, NNT=6.4, CI 3.6 to 28.3) and 50% (1 study, n=245, RR 0.6, CI 0.4, 0.9, NNT 7.4, CI 4.1 to 39.8) improvement in PANSS score than those treated with sertindole 8mg. For all other sertindole dosages examined (16, 20 and 24mg), there was no statistically significant difference between sertindole and haloperidol.

Although both studies reported the mean change from baseline or final data for PANSS score (Hale 2000 also reported PANSS component sub scale scores), Daniel 1998 reported the mean improvement in SANS total score, and Hale 2000 reported the final CGI‐severity end point score, no SD or any other measure of variance were reported and therefore the MD could not be estimated. At 12 months, the mean improvement from baseline in PANNS total end point score was 5.8 points for sertindole at 24mg compared to 1.4 for haloperidol (Daniel 1998). This difference was not found to be statistically significant (p value not given). At 8 weeks, the mean PANNS total end point score for haloperidol was 46.6 points and for the sertindole groups they were: 51.5 for 8mg, 48.3 for 16mg, 50.0 for 20mg, and 47.9 for 24mg (Hale 2000). The PANNS positive end point score for haloperidol was 10.0 and for the sertindole groups they were: 12.3 for 8mg, 11.0 for 16mg, 11.1 for 20mg, and 11.4 for 24mg (Hale 2000). The PANNS negative end point score for haloperidol was 14.3 and for the sertindole groups they were: 14.7 for 8mg, 12.4 for 16mg, 14.7 for 20mg, and 14.5 for 24mg (Hale 2000). At 12 months, the mean improvement from baseline in total SANS score was 3.9 for sertindole at 24mg compared to 0.1 for haloperidol (Daniel 1998). At 8 weeks, the CGI‐severity end point score for haloperidol was 3.0 points and for the sertindole groups they were: 3.1 for 8mg, 3.0 for 16mg, 3.1 for 20mg, and 3.0 for 24mg (Hale 2000).

Hale 2000 used the Jonckheere‐Terpstra analysis (a distribution free test) as the primary analysis of efficacy, to assess whether there was a monotonic ordering of treatment response. The Jonckheere‐Terpstra analysis of change in total PANSS score showed no statistically significant difference between sertindole 16, 20 and 24mg, but it showed a direct relationship between clinical response and dose of sertindole between 8 and 16 mg (p=0.05). There was no increase in efficacy for sertindole at dosages above 16mg, which was thus considered to be the optimal dose.

4. Extrapyramidal adverse effects

Daniel 1998 reported the percentage (from which the numbers presented in the figures in the forest plot were calculated) of participants that experienced EPS‐related adverse events (haloperidol 46%; sertindole (24mg) 29%) and Hale 2000 reported on the number of participants who experienced extrapyramidal syndrome (which includes abnormal movements classified as akathisia, dyskinesia and pseudo‐parkinsonism). The incidence of EPS was statistically significantly higher among those treated with haloperidol than sertindole for all doses of sertindole (8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 11.4, CI 7.1 to 29.8; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.3, CI 0.1 to 1.0, NNH 15.5, CI 8.0 to 217.9; and 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.8, NNH 13.7, CI 7.7 to 68.3; 24mg: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 0.8, NNH 8.7, CI 5.4 to 23.0).

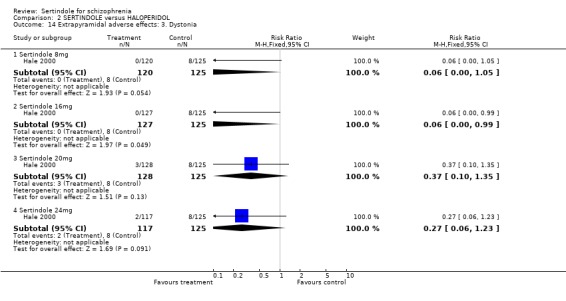

Both studies reported on the outcomes of akathisia, hypertonia and tremor. Pooled results (for sertindole 24mg) for all three outcomes showed a statistically significantly greater incidence rate reported amongst haloperidol treated participants as compared to sertindole (akathisia: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.5, CI 0.3 to 0.7, NNH 8.6, CI 5.6 to 18.3; hypertonia: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.5, CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNH 12.4, CI 7.5 to 35.0; tremor: 2 studies, n=524, RR 0.4, CI 0.2 to 0.6, NNH 8.2, CI 5.6 to 15.3). For the other sertindole dosages (8, 16 and 20mg) there was no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups for hypertonia, but statistically significantly more participants suffered from akathisia (8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.5, NNH 6.0, CI 4.1 to 11.2; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.3, NNH 5.4, CI 3.9 9.0; 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.3, CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNH 7.3, CI 4.6 to 17.9) or tremor (8mg: 1 study, n=245, RR 0.3, CI 0.1 to 0.7, NNH 8.5, CI 5.2 to 24.0; 16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.5, NNH 7.3, 4.8 to 15.6; 20mg: 1 study, n=253, RR 0.2, CI 0.1 to 0.6, NNH 7.8, CI 4.9 to 18.1) in the haloperidol group than those treated with sertindole, but these findings were based on a single study (Hale 2000).

Hale 2000 reported on dystonia and hypokinesia for which there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention groups.

Hale 2000 also presented the change in BAS, SAS and AIMS scores graphically (without giving the actual scores or the SD) which means that the MD could not be calculated.

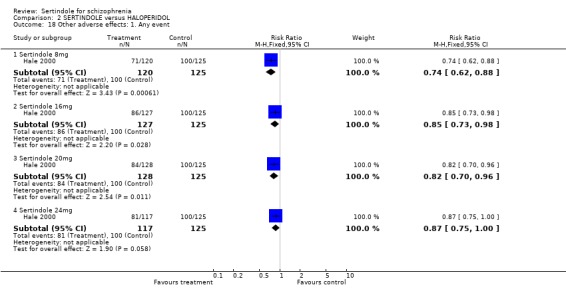

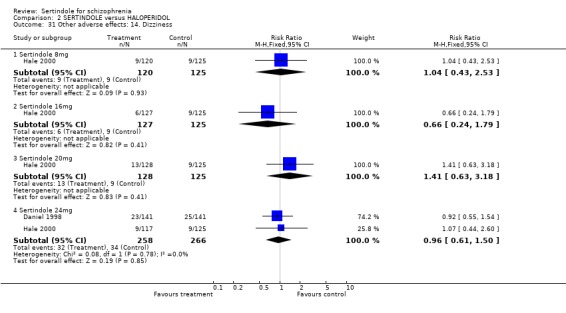

5. Other adverse effects 5.1. Any adverse event Hale 2000 reported the number of participants who experienced the most frequently reported (=10% in any treatment group) or statistically significant treatment emergent adverse events. Statistically significantly less participants treated with sertindole at 8mg (1 study, n=245, RR 0.7, CI 0.6 to 0.9; NNH 4.8, CI 3.1 to 10.4), 16mg (1 study, n=252, RR 0.9, CI 0.7 to 1.0; NNH 8.1 CI 4.3 to 64.7) or 20mg (1 study, n=253, RR 0.8, CI 0.7 to 1.0; NNH 7.0, 4.0 to 28.1) experienced any of these adverse events than those treated with haloperidol (10mg).

5.2. Cardiovascular problems

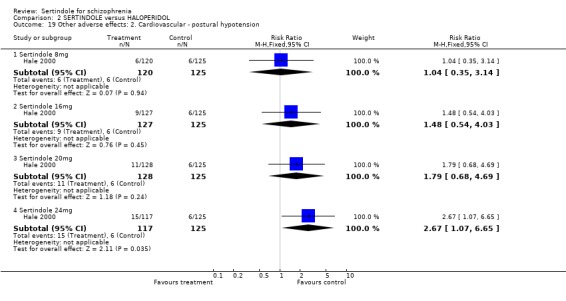

Hale 2000 reported on the incidence of postural hypotension for which there was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups, except for sertindole used at a dosage level of 24mg. Fifteen participants treated with sertindole had postural hypotension as compared to six participants treated with haloperidol (1 study, n=242, RR 2.7, CI 1.1, 6.7, NNH 12.5, CI 6.6 to 111.5).

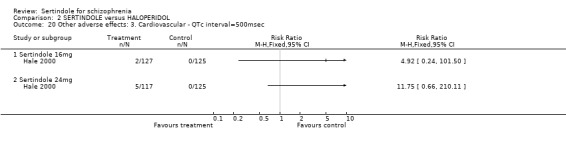

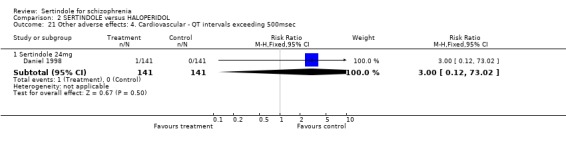

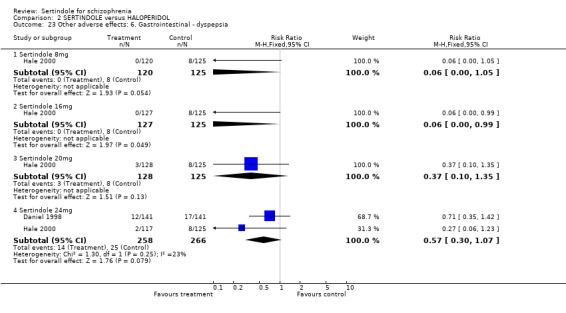

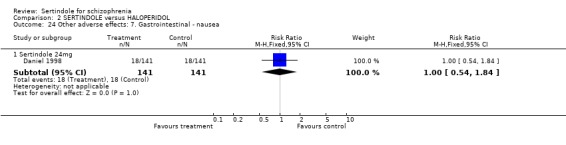

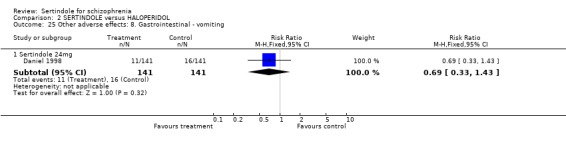

Both Daniel 1998 and Hale 2000 reported on the incidence of adverse events relating to QT and QTc intervals. For Hale 2000, the number of participants with QTc (cube root correction of the QT interval) equal to 500msec was greater in the sertindole 16mg (n=2) and 24mg (n=5) groups than in the haloperidol group (n=0; neither comparison was statistically significant). The authors noted that the increases from baseline to final value in mean QTc interval in the sertindole 16, 20 and 24mg groups (20, 26, and 24msec, respectively) were statistically significantly (p value was not reported) greater than in the haloperidol group (0msec), but no SD or any other measure of variance for the effect sizes were reported. The authors also noted that the mean change from baseline in QTc interval in the sertindole 8mg and haloperidol groups were not statistically different (actual results were not presented). For Daniel 1998 only one participant, from the sertindole group (24mg) had a QT interval that exceeded 500msec (1 study, n=282, RR 3.0 CI 0.1 to 73.0). However, 11 sertindole treated participants had QTc intervals of at least 500msec, compared to none in the haloperidol treated group (1 study, n=282, RR 23.0, CI 1.4 to 386.6, NNH 12.8, CI 8.2 to 29.6). 5.3. Gastrointestinal problems Both studies reported on dyspepsia and one study (Daniel 1998) reported on the incidence of nausea and vomiting. The results showed no real difference between the sertindole and haloperidol treated groups for any of these outcomes, with the incidence of dyspepsia being marginally higher among those treated with haloperidol.

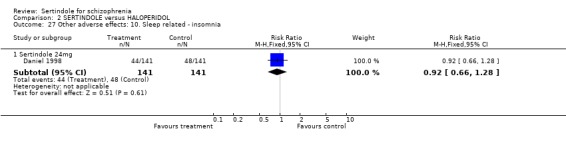

5.5. Sleep problems Both studies reported on somnolence which occurred less frequently in the sertindole treated groups, when used at 8mg (1 study, n=245, RR 0.1, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNH 11.4, CI 7.1 to 29.8) or 24mg (2 studies, n=524, RR 0.6, CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNH 14.8, CI 7.7 to 205.2), than haloperidol. This difference was found to be statistically significant. For sertindole used at 16 or 20mg there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups, with the incidence being slightly higher among those treated with haloperidol (Hale 2000). There was no significant difference between sertindole and haloperidol for the outcomes of insomnia as reported by a single study (Daniel 1998).

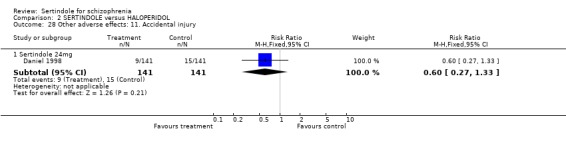

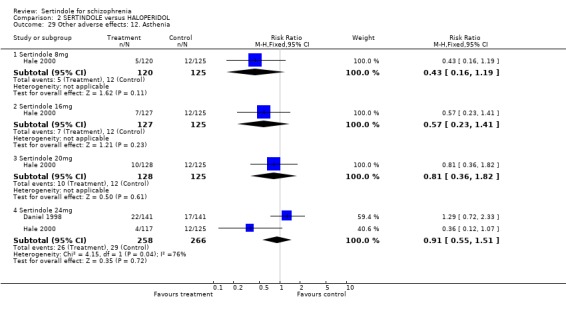

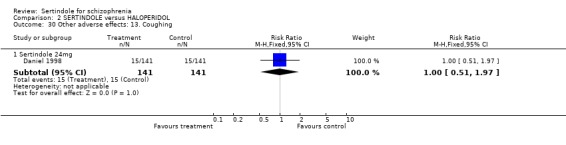

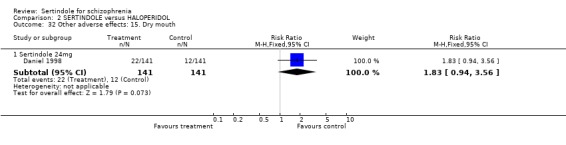

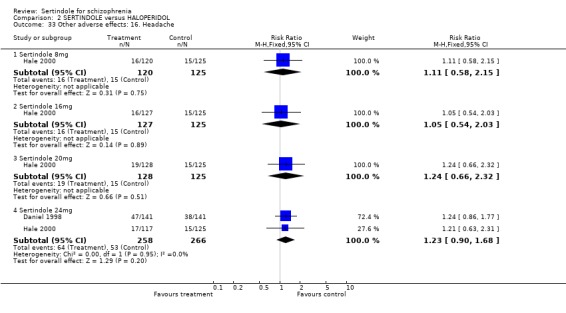

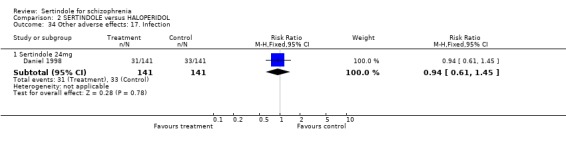

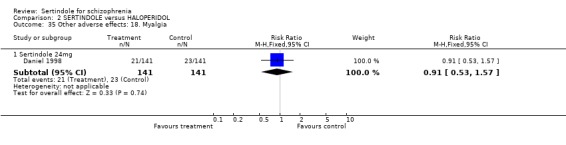

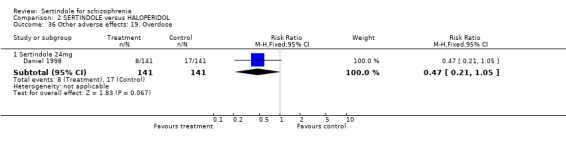

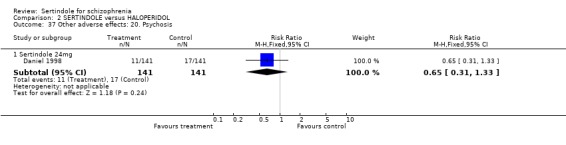

5.6. Other problems There was no statistically significant difference between the haloperidol treated participants and those taking sertindole (at any dosage level) for the following adverse events: accidental injury, asthenia, increased coughing, dizziness, dry mouth, headache, infection, myalgia, overdose, and psychosis. Both studies reported on asthenia, dizziness and headache, with the incidence of headache being fairly similar in both treatment groups (for sertindole 8 or 16mg) or slightly higher among those treated with sertindole (at dosages 20 and 24mg). For asthenia the incidence was slightly higher among those treated with haloperidol than sertindole at 8 and 16mg, but similar for the other two dosage groups. The results of two studies using 24mg/day of sertindole were heterogeneous. For dizziness the incidence was fairly similar for both sertindole and haloperidol treated participants for all dosages. Only one study (Daniel 1998; sertindole at 24mg) reported on psychosis, accidental injury, overdose, and dry mouth, and only one study (Daniel 1998) reported on the outcomes infection, myalgia, and increased coughing where there was no clear difference between sertindole and haloperidol.

Both studies reported on the incidence of rhinitis, which was found to be statistically significantly higher among those taking sertindole at 16 or 24mg as compared to haloperidol (16mg: 1 study, n=252, RR 10.8, CI 1.4 to 82.6, NNH 12.7, CI 7.7 to 36.7; 24mg: 2 studies, n= 524, RR 2.1, CI 1.4 to 3.1, NNH 8.7, CI 5.6 to 18.6). For sertindole used at the dosage level of 8 or 16mg there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups, with the incidence being slightly higher among those taking sertindole when compared to haloperidol at 10mg (Hale 2000).

Both studies reported the number of participants who experienced sexual dysfunction. However, neither study reported the denominators for these outcomes and therefore RR could not be calculated. (Both studies reported data on patient demographics, including male/female ratio, for the study's ITT population (Hale 2000 n=595, Daniel 1998 n=203) but not according to the number randomised (Hale 2000 n=617; Daniel 1998 n=242)). According to Hale 2000, a statistically significantly greater number of participants experienced abnormal ejaculation among those treated with sertindole (at any dose) than those treated with haloperidol (sertindole 8mg n=13; 16mg n=15; 20mg n=10; 24mg n=9; haloperidol n=2; p=0.05). Daniel 1998 reported the number of participants who experienced decreased ejaculatory volume (sertindole (24mg) n=33; haloperidol n=6; p>/= 0.05) or vaginitis (sertindole (24mg) n=0; haloperidol n=4).

Only one study (Daniel 1998) reported usable data on the incidence of weight gain. A significantly greater number of sertindole treated participants (n=19/141) were reported to have gained weight as compared to haloperidol treated participants (n=3/141) (1 study, n=282, RR 6.3, CI 1.9 to 20.9, NNH 8.8, CI 5.7 to 19.1). However, Hale 2000 reported that all of the sertindole groups showed an increase in body weight from baseline to final evaluation ranging from 1.3kg to 1.9kg. The authors noted that each of these changes in weight was statistically significantly different from the weight change recorded for the haloperidol treatment group (‐0.1Kg). However, the actual weight gain for each sertindole dosage group was not reported and no SD or any other measure of variance was given.

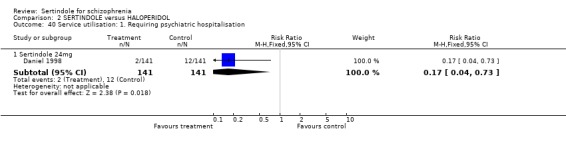

5. Service utilisation Daniel 1998 measured service utilisation in terms of the number of participants who required psychiatric hospitalisation, the number of psychiatric inpatient days and number of psychiatric hospitalisations. This was a long‐term study (one year) which included participants attending outpatients. They reported that a statistically significantly greater number of participants treated with haloperidol required psychiatric hospitalisation than those taking sertindole (24mg; 1 study, n=282, RR 0.2, CI 0.0 to 0.7, NNT 14.1, CI 8.3 to 47.9). The number of psychiatric hospitalisations was 11 for the sertindole group compared to 29 for the haloperidol group. In addition, participants treated with sertindole (n=94) were reported to have spent a total of 630 days in hospital as compared to 1,613 days by those treated with haloperidol (n=109).

7. Missing outcomes No studies reported economic outcomes (apart from service utilisation), quality of life or satisfaction with care.

Discussion

1. Generalisability All the included studies were multicentre and set in North America. All the participants met the DSM‐III‐R or DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. Most participants were in hospital, although Daniel 1998 included people who were attending outpatients. The generalisability of the findings of the review may, for this reason alone, be limited.

2. Limited data The quality of data reporting was disappointing. All three included studies had results which could not be used due to inadequate reporting. This is despite the publication of the CONSORT statement (Begg 1996) that encouraged high standard of trial reporting. Only one trial (Daniel 1998) reported on long‐term outcomes (one year) as well as service utilisation. No studies reported on economic outcomes, quality of life or directly on subject satisfaction. No studies included death as an outcome measure (although Hale 2000 reported some data on suicidal tendency and suicidal attempt). No studies included participants with treatment resistant schizophrenia or participants with predominantly negative or positive symptoms or first episode schizophrenia.

3. Sensitivity analysis and publication bias It was not possible for us to undertake the proposed funnel graph for publication bias or to do sensitivity analyses for people with schizophrenia described as 'treatment resistant', people having predominantly positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia and people experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia. This was due to the small number of full studies with useful data, the exclusion of patients who were treatment‐resistant and the inclusion of mainly those with chronic schizophrenia as opposed to first episode schizophrenia.

No more than one study looked at most outcome measures.

4. COMPARISON 1. SERTINDOLE versus PLACEBO The comparison of sertindole and placebo was based on a single medium term study that examined three different doses of sertindole (8, 12, and 20mg/day).

4.1. Leaving the study early Over a short period (six weeks) sertindole appears to be as well tolerated as placebo. There was no real difference in the number of participants leaving the study early due to adverse events and the number of participants leaving the study early due to ineffective treatment was marginally lower in the group treated with sertindole, but this difference was not statistically significant.

4.2. Clinical response 4.2.1. Global effect At six weeks, there was no statistically significant difference between sertindole (12 or 8mg/day) and placebo in CGI end point scores. The data for sertindole, used at 20mg/day showed very slight positive skewness. When a post hoc decision was made to include these data the results showed a statistically significant difference in global improvement in favour of the sertindole 20mg as compared to placebo. In terms of the binary outcome for global improvement, there was a marginally statistically significant number of participants treated with sertindole 20mg that were 'very much improved' as compared to placebo.

4.2.2. Mental state For mental state, at six weeks, the total endpoint scores, as measured by BPRS, favoured sertindole 20mg over placebo. Sertindole at doses of either 8mg or 12mg was not found to be better than placebo. When reporting total PANSS endpoint scores, no significant difference was found between sertindole, at any dose, and placebo.

4.3. Extrapyramidal adverse effects Sertindole was not found to cause more movement disorders than placebo. There was no statistically significant difference between sertindole and placebo for the incidence of akathisia, tremor, cogwheel rigidity or hypertonia. There was also no difference between the treatment groups in terms of general EPS symptoms, EPS related events or use of EPS medication.

4.4. Other adverse effects 4.4.1. Cardiac problems There was little usable data reported on the incidence of cardiac problems when comparing sertindole with placebo. Observed differences between treatment groups with regard to ECG findings and heart rate were reported. There was a statistically significant difference in mean change from baseline, in the QT intervals, QTc intervals, and heart rate observed between the placebo and sertindole groups, in favour of placebo. However, as the authors did not provide the SD, the WMD could not be calculated.

4.4.2 Gastrointestinal problems There were no significant differences between sertindole and placebo.

4.4.3 Sleep related problems The placebo controlled trial did not indicate that sertindole caused more somnolence or insomnia than placebo.

4.4.4 Other problems There was a significant difference between sertindole (20mg, n=9) and placebo (n=1) for the occurrence of decreased ejaculation (p<0.05). Sexual function is of crucial concern to people with schizophrenia given the side effects of medication, yet this outcome measure was inadequately reported with the actual number of male participants included in the study not being presented.

Sertindole appears to cause weight gain. There was a greater observed mean weight gain among participants taking sertindole as compared to placebo. However, the SD was not reported, which means that the data could not be used. Weight gain is an important outcome which unfortunately is consistently poorly reported (Duggan 1999).

5. COMPARISON 2. SERTINDOLE versus HALOPERIDOL Two studies that compared the use of sertindole to haloperidol were included. One was a short term study that examined four different doses of sertindole (8, 16, 20 or 24mg /day) and one was a long term study that used sertindole at 24 mg/day.

5.1. Leaving study early When considering discontinuation of treatment due to any reason (including lack of treatment response), one study found that there was a statistically significantly greater number of participants treated with sertindole (24mg) leaving the study early compared to haloperidol at one year, whilst the second study found no real difference between sertindole (8, 16, 20 or 24mg) and haloperidol at six weeks.

There were marginally fewer participants leaving the study early due to any adverse effects in the sertindole (24mg) group than in the haloperidol (10mg) group over a one year period (according to one study that included patients attending outpatients), but this difference was not found to be statistically significant. This outcome was not clearly reported in the second included study (see results section). Two sertindole treated participants also discontinued treatment due to abnormal blood chemistry values and a further two participants because of leukopenia. One study also reported on the number of participants who had to leave the study due to abnormal ECG or blood chemistry values, none of which were found to be statistically significant. Three people discontinued treatment due to prolonged QT intervals, which included two who were treated with sertindole and only one with haloperidol.

At one‐year non‐compliance was found to be statistically significantly higher among participants taking haloperidol (10mg/day) than those on sertindole (24mg/day).

5.2. Clinical response: global impression and mental state One long term study presented no usable data for global impression or mental state outcomes. The only usable data for these outcomes reported in the second short term study was the number of participants with at least 30, 40, and 50% improvement in PANSS score, for which there was no significant difference between sertindole (16, 20 or 24mg/day) and haloperidol (haloperidol was found to be more effective than sertindole at 8mg). Based on their own statistical analysis (Jonckheere‐Terpstra analysis), Hale 2000 concluded that sertindole 16mg/day was the most optimal dose.

5.3. Extrapyramidal adverse effects Sertindole was shown to cause less movement disorders than haloperidol (10mg/day). The incidence of EPS was statistically significantly higher among haloperidol treated participants than those who received sertindole. More specifically, the incidence of akathisia, hypertonia (for 24mg/day only) and tremor was statistically significantly higher among haloperidol treated participants than sertindole. There was no real difference between treatment groups for dystonia and hypokinesia (and hypertonia for sertindole used at 8, 16 or 20mg/day). Change in BAS and SAS scores could not be analysed due to poor reporting of results.

5.4. Other adverse effects 5.4.1. Cardiovascular problems Sertindole appears to cause more cardiovascular problems than haloperidol. Both studies reported statistically significantly greater incidence of adverse events relating to QT and QTc intervals in the sertindole group compared to haloperidol. One short term study also reported the baseline and final values for QTc intervals, but did not report the SD. For sertindole used at 24mg, there was a marginal statistically significant difference in favour of haloperidol (10mg) for the outcome hypotension (at six weeks).

5.4.2 Gastrointestinal problems No statistically significant difference was found between sertindole and haloperidol for the following gastrointestinal adverse effects: dyspepsia, nausea, and vomiting.

5.4.3 Sleep related problems Sertindole 8 and 24mg/day seems to be less sedating than haloperidol. No statistically significant difference was found between sertindole and haloperidol for insomnia.

5.4.4 Other problems No statistically significant difference was found between sertindole and haloperidol for the following adverse effects: accidental injury, asthenia, dizziness, dry mouth, dyspepsia, headache, increased coughing, infection, insomnia, myalgia, nausea, psychosis and vomiting.

Sertindole appears to cause sexual dysfunction in terms of abnormal ejaculation but although both studies reported data that indicated this neither study reported usable data. Again this is a symptom of great concern to men with schizophrenia.

Sertindole at 16 and 24mg/day appears to cause more rhinitis than haloperidol.

Sertindole (24mg/day) seems to cause more weight gain than 10mg of haloperidol. Although both studies reported data that indicated this, only one long term study reported usable data. Weight gain can be a real problem with antipsychotics and when ranked for importance by those with schizophrenia may well be higher than movement disorders.

5.5. Service utilisation One long term study measured service utilisation in terms of the number of participants who required psychiatric hospitalisation, the number of psychiatric inpatient days and number of psychiatric hospitalisations. This was a one year study which included participants who were attending outpatients. A significantly greater number of participants treated with haloperidol (10mg/day) required psychiatric hospitalisation than those taking sertindole (24mg/day). Similarly, the number of psychiatric hospitalisations was reported to be greater among haloperidol treated participants as compared to those in the sertindole group. However, there was no SD reported for both the number of psychiatric hospitalisations or the number of days spent in hospital and therefore the WMD could not be calculated.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. People with schizophrenia Sertindole at a dose of 20mg/day was found to be more antipsychotic than placebo. It appears to be as acceptable as placebo, better tolerated than haloperidol and produced few movement disorders. However, it has also been shown to cause cardiac anomalies, weight gain, rhinitis and problems with sexual functioning in men.

Sertindole was not associated with statistically significantly more extrapyramidal side‐effects than placebo. This finding must be interpreted cautiously, because the result may be due to insufficient power to show any statistically significant difference between the groups.

2. Clinicians At higher doses, sertindole appears to be more effective (as an antipsychotic) than haloperidol at 10mg/day, but seems to be associated with increased weight gain and problems with sexual functioning. When used at any dose, it appears to cause less movement disorders than haloperidol (10mg/day) but also results in more cardiac abnormalities. Lower doses of sertindole seem to be associated with less sedation than haloperidol (10mg/day).

3. Administrators Until the clinical relevance of QTc prolongation associated with sertindole has been clarified, the drug can not be used in every day practice.

4. Governments and health policy makers Although sertindole appears to be better tolerated than haloperidol and produced few movement disorders, it's propensity to cause cardiac problems limits it's suitability as a first line alternative to haloperidol when other a‐typical antipsychotics are available (see other related Cochrane reviews). However, no completed studies comparing sertindole with other a‐typical antipsychotics were found, and it is therefore difficult to really assess it's usefulness as an alternative to other a‐typical antipsychotics.