Abstract

Background

In pregnancies complicated by diabetes the major concerns during the third trimester are fetal distress and the potential for birth trauma associated with fetal macrosomia.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effect of a policy of elective delivery, as compared to expectant management, in term diabetic pregnant women, on maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (24 July 2004). We updated this search on 24 July 2009 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

All available randomized controlled trials of elective delivery, either by induction of labour or by elective caesarean section, compared to expectant management in diabetic pregnant women at term.

Data collection and analysis

The reports of the only available trial were analysed independently by the three co‐reviewers to retrieve data on maternal and perinatal outcomes. Results are expressed as relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

The participants in the one trial included in this review were 200 insulin‐requiring diabetic women. Most had gestational diabetes, except 13 women with type 2 pre‐existing diabetes (class B). The trial compared a policy of active induction of labour at 38 completed weeks of pregnancy, to expectant management until 42 weeks. The risk of caesarean section was not statistically different between groups (relative risk (RR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 ‐ 1.26). The risk of macrosomia was reduced in the active induction group (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 ‐ 0.98) and three cases of mild shoulder dystocia were reported in the expectant management group. No other perinatal morbidity was reported.

Authors' conclusions

The results of the single randomized controlled trial comparing elective delivery with expectant management at term in pregnant women with insulin‐requiring diabetes show that induction of labour reduces the risk of macrosomia. The risk of maternal or neonatal morbidity was not different between groups, but, given the rarity of maternal and neonatal morbidity, the number of women included does not permit to draw firm conclusions. Women's views on elective delivery and on prolonged surveillance and treatment with insulin should be assessed in future trials.

[Note: The one citation in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Plain language summary

Elective delivery in diabetic pregnant women

Induction of labour at 38 weeks pregnancy for women with diabetes treated with insulin lowers the chances of delivering a large baby.

Women with diabetes or gestational diabetes are more likely to have a large baby, which can cause problems around birth. Early elective delivery (labour induction or caesarean section) aims to avoid these complications. However, early elective delivery can also cause problems. The review found only one trial of labour induction for women with diabetes treated with insulin. Induction of labour lowered the number of large babies without increasing the risk of caesarean section. However, there was not enough evidence to definitively assess this intervention.

Background

Diabetes complicates 2.6% of pregnancies (Cunningham 1997). This disease is classified as type 1 (insulin dependent), type 2, and gestational diabetes. Most (90%) cases of diabetes complicating pregnancy are gestational diabetes. Complications during pregnancy vary according to the type of diabetes and the severity of the disease.

In pregnancies complicated by pregestational diabetes, the major concerns during the third trimester are late fetal death, complications necessitating premature delivery (eg pre‐eclampsia) and the potential for birth trauma associated with fetal macrosomia (Hanson 1993; Cousins 1987). This is especially the case in women with type 1 diabetes. In the past, some authors have proposed to perform elective delivery, either by induction of labour or by caesarean section, before full term in these women, because of increased perinatal mortality during the third trimester (Hunter 1989). Early labour induction may increase the risk of pulmonary complications related to the immaturity of the fetus. Perinatal mortality has decreased over time, both in general and in diabetic pregnancies (Blatman 1995). This reduction was contemporaneous with more intensive management of diabetic pregnancies, resulting in better blood sugar control. Nowadays, some authors advocate that uncomplicated pregnancies in diabetic women may be continued safely until the expected date of delivery, provided that metabolic control is good (Coustan 1995). In women diagnosed with gestational diabetes, the main complication is fetal macrosomia. These large for gestational age fetuses are at risk of birth trauma, including shoulder dystocia, bone fractures and brachial plexus injury. Neonates born to diabetic women are also at risk of hypoglycemia and other transient metabolic disorders. Although rarer than in type 1 diabetes, perinatal mortality may be increased with insulin‐requiring gestational diabetes (Johnstone 1990).

The rationale for performing an elective delivery include a potential reduction in perinatal complications, especially those related to macrosomia (Brudenell 1989). Many obstetricians prefer to induce labour at 38 weeks of gestation in the presence of a favourable cervix or after documenting fetal lung maturity (Blatman 1995; Pedersen 1986). In women with an unfavourable cervix, both expectant management and cervical ripening with prostaglandins or by mechanical methods followed by induction of labour, are proposed (Coustan 1995).

Expectant management might be the preferred option, to avoid a potentially higher risk of prolonged labour and of caesarean section following induction of labour, especially in women with an unfavourable cervix (Macer 1992). Caesarean section, including elective caesarean, may increase the risk of maternal morbidity, including urinary tract infection, haemorrhage, wound infection and scar dehiscence or uterine rupture during subsequent labour (Irion 1998).

The choice between a policy of early elective delivery (either by induction of labour or by Caesarean section) and expectant management in diabetic women should take into consideration perinatal mortality and perinatal morbidity related to macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, fetal distress and respiratory morbidity related to prematurity. Regarding maternal morbidity, caesarean section, instrumental delivery and women's views of their care need to be evaluated.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of a policy of elective delivery at or near term, as compared to expectant management, in diabetic pregnant women, on maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All known randomized controlled trials evaluating elective delivery at or near term (either by induction of labour or by caesarean section) in pregnancies complicated by diabetes (either pregestational or gestational) were included. Fetal wellbeing in the expectant management group could have been assessed by any method (eg fetal heart rate monitoring, biophysical profile).

Types of participants

Trials including both pregnant women diagnosed with pregestational, either type I or type II, diabetes or with gestational diabetes, treated by insulin or diet alone, are eligible for the review. However, these sub‐groups will be analysed separately if possible, as the effect of the intervention (elective delivery) might be different according to the type of diabetes.

Types of interventions

Studies comparing elective delivery, either by induction of labour or by caesarean section, at 37 to 40 weeks (259 to 280 days) to expectant management. Induction of labour by any method was considered.

Types of outcome measures

Prespecified outcome measures were: Primary outcomes: perinatal mortality, traumatic delivery (intracranial haemorrhage, fracture, brachial plexus injury), long term disability in childhood, caesarean section. Other outcome measures: Maternal morbidity: instrumental delivery, third and fourth degree perineal tears, any perineal trauma, perineal and abdominal pain after delivery. Women's views of their care. Perinatal outcomes: shoulder dystocia (as defined by authors), neonatal asphyxia (low arterial cord blood pH, low 5 minutes Apgar score, as defined by authors), hypoglycemia, admissions to neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal seizures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (6 July 2004). We updated this search on 24 July 2009 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We assessed for inclusion all potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy and extracted data independently. We designed a data extraction form to facilitate the process of data extraction and to request additional (unpublished) information from the authors of the original report. There were no disagreements between reviewers with respect to inclusion/exclusion of studies or data extraction.

Statistical analyses

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2002). For dichotomous data, results are presented as summary relative risk with 95% confidence intervals.

If more than one trial is included in the future, we will apply tests of heterogeneity between trials, reported as fixed effect summary, using the I² statistic. Where we identify high levels of heterogeneity among the trials, levels exceeding 50%, this will be explored by prespecified subgroup analysis and a sensitivity analysis. We will use a random effects meta‐analysis as an overall summary.

Results

Description of studies

The described search strategy found only one randomized controlled trial (Kjos 1993). (One report is awaiting assessment.) Kjos 1993 compared induction of labour with expectant management in insulin‐requiring diabetic pregnant women at term (see characteristics of included studies). Two hundred women were included, 100 in each group. Most women (187) had gestational diabetes treated with insulin, but 13 women with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin were also included. Induction of labour was performed in 70% of women in the induction group, as compared to 49% in the expectant management group. The mean delay from randomization to delivery was 6.4 days in the induction group, while it was 12.8 days in the expectant group. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

Another study was identified (Khojandi 1974). The results of this study were not included, because it was unclear which interventions were compared (vaginal delivery and cesarean section at 38 weeks, but women with spontaneous labour before 38 weeks were seemingly included in the "vaginal delivery" group). The method of random allocation is also unclearly reported.

Risk of bias in included studies

The method of randomization and of concealment of the allocation was not reported in the identified trial (Kjos 1993). In this study, inclusion of only insulin‐requiring pregnant women with good metabolic control was appropriate and improved the homogeneity of the participants with respect to the severity of the disease. Because of strict inclusion criteria, only 200 women among 944 insulin‐requiring diabetic pregnant women were enrolled in the trial.

Effects of interventions

One trial, involving 200 women, was included.

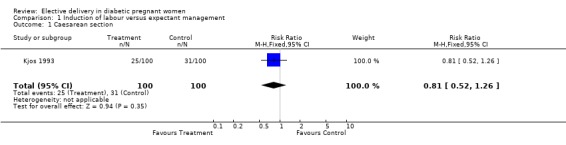

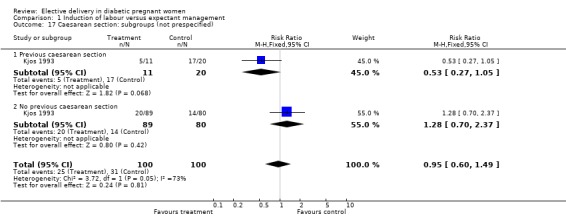

The risk of caesarean section (elective or in labor) was not statistically different between groups (relative risk (RR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.26). More women in the expectant management group had a previous cesarean section as compared to the induction group (20% and 11%, respectively). Elective caesarean section was performed in 8% of women in the induction group, and 7% in the expectant group. Little information is available on other maternal outcomes.

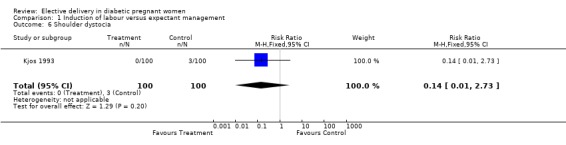

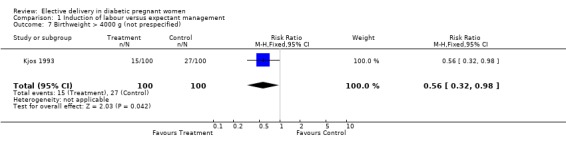

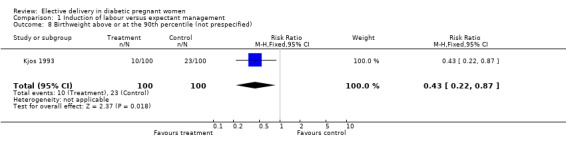

The risk of macrosomia, defined as birthweight above 4000 g, was reduced in the active induction group (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.98), while two infants in the expectant group had a birthweight of more than 4500 g. Mean birthweight and proportion of large‐for‐gestational age infants (at or above 90th percentile) were higher in the expectant management group. Perinatal morbidity was rare. Three cases of mild shoulder dystocia (without brachial plexus injury or bone fracture and with Apgar scores at 5 minutes higher than 7) were observed in the expectant management group, while none were reported in the induction group. No other perinatal morbidity was reported.

Results of the 187 women with insulin‐requiring gestational diabetes can not be analysed separately from the results of the 13 women with pregestational diabetes.

Discussion

A policy of induction of labour at 38 weeks of gestation in diabetic women treated with insulin was associated with a reduction in the frequency of birth weight above 4000 g and above the 90th percentile. This is not surprising, given that gestational age at delivery was one week earlier in the active induction group. We had not prespecified these outcome measures, as they are intermediate risk factors for substantive adverse outcomes (e.g. trauma during delivery). This intervention did not appear to increase the risk of caesarean section. Neonatal morbidity was rare and similar between groups. However, only one randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess this intervention. Fifty percent of women in the expectant management group had labour induction for various obstetric indications. This decreases the power of the study to show differences between groups. Only 13 women with pregestational diabetes were included. Therefore, no conclusion can be generalised to this sub‐group of women.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of the single randomized controlled trial comparing elective delivery with expectant management at term in pregnant women with insulin‐requiring diabetes show that induction of labour reduces the risk of macrosomia. The risk of maternal or neonatal morbidity was not different between groups, but, given the rarity of these outcomes, the number of women included does not permit to draw firm conclusions. There might be little advantage in delaying delivery beyond 38‐39 weeks and induction of labour might be a reasonable option for these women. The study was too small to assess the effect on perinatal mortality.

[Note: The one citation in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Implications for research.

Further randomized controlled trials, with a large sample size, are needed to evaluate elective delivery in diabetic pregnant women. Expectant management might be associated with anxiety because of the possible risk of unexpected fetal distress. Maternal inconvenience because of surveillance and treatment with insulin should be assessed. Future trials should include these outcome measures. Research should also be performed in the group of women with gestational diabetes treated with diet only.

Feedback

Coomarasamy and Gee, October 2000

Summary

Types of participant Women with pre‐existing diabetes have a poorer outcome than those with gestational diabetes. Only 13 women in this review had pre‐existing diabetes, so these data are not applicable to this group of women. Also, a history of previous caesarean section reduces the chance of having a vaginal birth. The 31 women with previous caesarean section included in the single trial (Kjos 1993) were not evenly distributed across the groups (20 in the expectant group and 11 in induction). The possible effect of this difference should be explored and accounted for.

Types of outcome What is 'mild shoulder dystocia', and is this a reproducible and valid outcome? What is the justification for 4000g as the cut off for macrosomia?

Discussion The strength of a systematic review is in combining data, thereby increasing power. Systematic reviews should not be based on one trial, particularly if the study is small and important outcomes are rare. If a systematic review identifies only one trial, as this one does, it should not be published on the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Using the hierarchy of evidence, evidence from systematic reviews is rated higher than randomised trials. A systematic review with a single trial is therefore raising the status of that study, without any additional data.

[Summary of comments from A Coomarasamy and H Gee, May 2000 and October 2000.]

Reply

A comment about the limited data for women with pre‐existing diabetes has been added to the end of the discussion. Data for women who have not had a previous caesarean section have now been presented separately. The definition for mild shoulder dystocia is in the Results text. The data for birthweight are now labelled as not pre‐specified.

The strength of a systematic review is in reducing bias as well as increasing power. Of equal, or perhaps greater, importance as synthesis of data is the systematic search for studies. For this reason it is quite valid to have a review with no studies, or with just a single trial. A review with a single trial does give more information than a single trial without a systematic search, as it demonstrates the overall lack of evidence. Identifying areas where there is little or no evidence is of great clinical importance, particularly for consumers, and will often stimulate new trials.

[Summary of response from Michel Boulvain and Catalin Stan, January 2001]

Contributors

A Coomarasamy and H Gee.

Fraser, September 2002

Summary

This is an uncharitable review of a single randomised study of the greatest clinical importance. No other trial of any quality has addressed this question, and the authors should be congratulated.

The arguments are simple, the case for early delivery is to avoid mature stillbirths and birth trauma. There is no difference in the risk of these complications between gestational and pregestational diabetics, and the basis for the reviewers' comment that "the effect of intervention (elective delivery) might be different according to the type of diabetes" is unclear. The case against early delivery is to reduce caesarean section rates, and its associated morbidity.

The study is as good as you are likely to get, and clearly makes a case for elective delivery. We can assume stillbirth will be avoided with early delivery, and there is no increase in the risk of caesarean section, and a likely reduction in birth trauma.

Therefore, unlike the reviewers I think this small trial does allow us to draw conclusions. My conclusion is that any further trials addressing this question would be unethical.

[Summary of comments received from Robert Fraser, September 2002.]

Reply

We agree that the authors of this trial should be congratulated on their study, and that it "is as good as you are likely to get". We cannot find any statement suggesting the opposite in our review.

We do not, however, agree that the risk of morbidity and mortality is the same for the different types of diabetes. There is a wide spectrum of severity of clinical presentation. From minor gestational diabetes easily controlled by diet alone (with probably no increased morbidity, except from medical interventions) through to insulin dependant diabetes (type I) associated with increased risk of perinatal mortality in the absence of medical interventions.

The results of the single trial in our review do not validate the hypothesis that elective delivery reduces the risk of stillbirth. Also, it remains unclear whether the risk of caesarean section is increased following induction of labour, despite reassuring results from this study which did not show a major increase in caesarean section.

As we cannot draw firm conclusions from limited data, we believe it is better to say so, and to let the reader and the women decide what is best in her clinical situation. We do not believe that a further trial would be unethical, as this study does not show a clear benefit for either management option. Such a trial would require a large sample size, given the low risk with current management.

[Summary of response from Michel Boulvain, December 2002]

Contributors

Robert Fraser.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 July 2009 | Amended | Search updated. One new report identified and added to Studies awaiting classification (Ghosh 1979). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 July 2004 | New search has been performed | Search updated. We identified one new trial which has been excluded (Khojandi 1974). |

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the referees, especially the consumers, for their very detailed and useful comments on the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Induction of labour versus expectant management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.52, 1.26] |

| 2 Instrumental delivery | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Third and fourth degree perineal tear | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Pain after delivery | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Women's views of their care | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Shoulder dystocia | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.73] |

| 7 Birthweight > 4000 g (not prespecified) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.32, 0.98] |

| 8 Birthweight above or at the 90th percentile (not prespecified) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.22, 0.87] |

| 9 Fracture | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Brachial plexus injury | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Neonatal asphyxia | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Hypoglycaemia | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Neonatal seizures | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

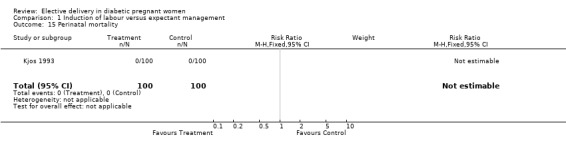

| 15 Perinatal mortality | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Long‐term disability in childhood | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Caesarean section: subgroups (not prespecified) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.60, 1.49] |

| 17.1 Previous caesarean section | 1 | 31 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.27, 1.05] |

| 17.2 No previous caesarean section | 1 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.70, 2.37] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Caesarean section.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 6 Shoulder dystocia.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 7 Birthweight > 4000 g (not prespecified).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 8 Birthweight above or at the 90th percentile (not prespecified).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 9 Fracture.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 10 Brachial plexus injury.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 11 Neonatal asphyxia.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 12 Hypoglycaemia.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 15 Perinatal mortality.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Induction of labour versus expectant management, Outcome 17 Caesarean section: subgroups (not prespecified).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kjos 1993.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial (no details given in the report on the methods for generating the list or on concealment of the allocation). | |

| Participants | 200 women (100 in the elective delivery group, 100 in the expectant management group). Inclusion criteria: diabetic (either type I or type II, or gestational diabetes) pregnant women treated by insulin; good metabolic control (preprandial BS =<5 mmol/L and postprandial BS =<6.7 mmol/L for at least 90% of the readings); term >=38 weeks (266 days); normal biophysical assessment of the fetus; singleton; vertex presentation; estimated fetal weight <3800 g; no evidence of IUGR; no other medical or obstetrical complications; no more than 2 previous caesarean sections. | |

| Interventions | Active induction of labour by IV oxytocin within 5 days. For pregnancies with unclear gestational age, amniocentesis was performed, and induction delayed until lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio >= 2.0. Expectant management until 42 weeks with twice weekly antenatal testing and weekly consultation. Induction of labour indicated by fetal distress, preeclampsia, poor metabolic control (see above definition), estimated fetal weight >4200 g, or term >42 weeks (294 days). | |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery (caesarean section rate was the primary outcome measure). Birthweight (mean, >= 4000 g, >= 4500 g, and large for gestational age >= 90th percentile). Neonatal morbidity (shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, asphyxia, hypoglycemia) and mortality. | |

| Notes | Information on methods of randomization requested. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

BS: blood sugar IUGR: intrauterine growth retardation iv: intravenous

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Khojandi 1974 | Compares vaginal (with or without induction of labour) with abdominal delivery at 38 weeks of gestation. Unclear method of randomisation (by an "objective" clerk). Very large difference in maternal weight between groups, suggesting a bias in the allocation. The management of the two groups is also unclear (women with spontaneous labour prior to 38 weeks were included, seemingly, all in the "vaginal" group). |

Contributions of authors

All three reviewers contributed to the development of the protocol, extracted the data and wrote the text of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Geneva, Switzerland.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Kjos 1993 {published data only}

- Henry OA, Kjos SL, Montoro M, Buchanan TA, Mestman JH. Randomized trial of elective induction vs expectant management in diabetics. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;166:304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjos SL, Henry OA, Montoro M, Buchanan TA, Mestman JH. Insulin‐requiring diabetes in pregnancy: a randomized trial of active induction of labor and expectant management. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;169:611‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Khojandi 1974 {published data only}

- Khojandi M, Tsai AY/M, Tyson JE. Gestational diabetes: the dilemma of delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1974;43:1‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Ghosh 1979 {published data only}

- Ghosh S, Khakoo H, Pillari VT, Carmona RA, Rajegoda BK, Poliak A. Timing of delivery in rigidly controlled class B diabetes [abstract]. 9th World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 1979 October 26‐31; Tokyo, Japan. 1979:270‐1.

Additional references

Blatman 1995

- Blatman RN, Barss VA. Obstetrical management. In: Brown FM, Hare JW editor(s). Diabetes complicating pregnancy: the Joslin Clinic method. 2nd Edition. New York: Wiley and Sons Inc, 1995:135‐65. [Google Scholar]

Brudenell 1989

- Brudenell M, Doddridge M. Delivering the infant. In: Lind T editor(s). Current reviews in obstetrics and gynecology. Diabetic pregnancy. Vol. 13, New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1989:70‐83. [Google Scholar]

Cousins 1987

- Cousins L. Pregnancy complications among diabetic women: review 1965‐1985. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 1987;42:140‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coustan 1995

- Coustan DR. Delivery: timing, mode and management. In: Reece EA, Coustan DR editor(s). Diabetes mellitus in pregnancy. Principles and practice. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, 1995:353‐60. [Google Scholar]

Cunningham 1997

- Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap III LC, Hankins GDV, et al. Williams obstetrics. 20th Edition. London: Prentice‐Hall International, 1997:1203‐21. [Google Scholar]

Hanson 1993

- Hanson U, Persson B. Outcome of pregnancies complicated by type 1 insulin‐dependent diabetes in Sweden: acute pregnancy complications, neonatal mortality and morbidity. American Journal of Perinatology 1993;10:330‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hunter 1989

- Hunter DJS. Diabetes in pregnancy. In: Chalmers I, Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC editor(s). Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989:578‐93. [Google Scholar]

Irion 1998

- Irion O, Hirsbrunner Almagbaly P, Morabia A. Planned vaginal delivery versus elective caesarean section: a study of 705 singleton term breech presentations. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1998;105:710‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnstone 1990

- Johnstone FD, Nasrat AA, Prescott RJ. The effect of established and gestational diabetes on pregnancy outcome. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;97:1009‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Macer 1992

- Macer JA, Macer CL, Chan LS. Elective induction versus spontaneous labor: a retrospective study of complications and outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;166:1690‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pedersen 1986

- Pedersen ML, Kuhl C. Obstetric management in diabetic pregnancy: the Copenhagen experience. Diabetologia 1986;29:13‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2002 [Computer program]

- Version 4.2 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan).. Version 4.2 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2002.