Abstract

Background

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay treatment for schizophrenia and similar psychotic disorders. Long‐acting depot injections of drugs such as fluspirilene are extensively used as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment.

Objectives

To review the effects of depot fluspirilene versus placebo, oral anti‐psychotics and other depot antipsychotic preparations for people with schizophrenia in terms of clinical, social and economic outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (September 2005), inspected references of all identified studies, and contacted relevant pharmaceutical companies.

Selection criteria

We included all relevant randomised trials focusing on people with schizophrenia where depot fluspirilene, oral anti‐psychotics, other depot preparations, or placebo were compared. Outcomes such as death, clinically significant change in global function, mental state, relapse, hospital admission, adverse effects and acceptability of treatment were sought.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were reliably selected, quality rated and data extracted. For dichotomous data, we calculated relative risk (RR) with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, the number needed to treat statistic (NNT) was calculated. Analysis was by intention‐to‐treat. We summated normal continuous data using the weighted mean difference (WMD). We presented scale data only for those tools that had attained pre‐specified levels of quality.

Main results

We included twelve randomised studies in this update of which five are additional studies. One trial compared fluspirilene and placebo and did not report important differences in the global improvement (n=60, 1 RCT, RR "no important improvement "0.97 CI 0.9 to 1.1). Though movement disorders (n=60, 1 RCT, RR 31.0 CI 1.9 to 495.6, NNH 4) were found only in the fluspirilene group, there were no convincing data showing the advantage of oral chlorpromazine or other depot antipsychotics over fluspirilene decanoate. We found no difference between depot fluspirilene and other oral antipsychotics with regard to relapses or to the number of people leaving the study early. Global state data (CGI) were not significantly different, in the short term when comparing fluspirilene with other depots (n=90, 2 RCTs, RR "no important improvement" 0.80 CI 0.2 to 2.8). No significant difference were apparent between fluspirilene and other depots with respect to the number of people leaving the trial early (n=83, 2 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.1 to 2.3) or relapse rates (n=109, 3 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.1 to 2.3). Extrapyramidal adverse effects were significantly less prevalent in the fluspirilene groups (n=164, 4 RCTs, RR 0.50 CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNH 5). Other adverse effects were not significantly different. Attrition in the one comparison between fluspirilene in weekly versus biweekly administration (n=34, RR 3.00 CI 0.1 to 68.8) and relapse rates (n=34 RR 3.18 CI 0.1 to 83.8) were not significantly different. There were no significant difference for movement disorders in one short term study. No study reported on hospital and service outcomes or commented on participants' overall satisfaction with care. Economic outcomes were not recorded by any of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

Participant numbers in each comparison were small and we found no clear differences between fluspirilene and oral medication or other depots. The choice of whether to use fluspirilene as a depot medication and whether it has advantages over other depots cannot, at present, be informed by trial‐derived data. Well‐conducted and reported randomised trials are still needed to inform practice.

Keywords: Humans; Administration, Oral; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/administration & dosage; Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use; Delayed‐Action Preparations; Delayed‐Action Preparations/administration & dosage; Delayed‐Action Preparations/therapeutic use; Fluspirilene; Fluspirilene/administration & dosage; Fluspirilene/therapeutic use; Injections, Intramuscular; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Schizophrenia; Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Depot fluspirilene for schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a serious, chronic and relapsing mental illness with a worldwide lifetime prevalence of about one percent. Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia, but compliance with medication is often poor due to the adverse effects profile of the drugs and/or the patient's beliefs about their illness. Non‐compliance with medication is a major cause of relapse with significant personal, social and economic costs.

Depot antipsychotics were developed in the 1960's specifically to promote treatment compliance and gave rise to extensive use of depots as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment. Depot antipsychotics are administered intramuscularly and the drug is released into the body slowly over an extended period of time. These antipsychotics need to be injected only once every 2‐4 weeks.

Fluspirilene is a relatively long‐acting injectable depot antipsychotic drug used for schizophrenia. We updated the original systematic review (David 1999) on Depot fluspirilene for schizophrenia with five additional studies. Twelve randomised trials are included. Study sizes are small and most were of short term duration. This cannot be very informative for a drug that is meant for long‐term maintenance treatment. However, from the studies we were able to include, fluspirilene decanoate does not differ greatly from other depot antipsychotics (fluphenazine decanoate, fluphenazine enathate, perphenazine onanthat, pipotiazine undecylenate) with respect to treatment efficacy, response or tolerability. Outcomes suggest that fluspirilene does not differ significantly from oral antipsychotics or in different weekly regimens, although much cannot be inferred because of the shortage of trials.

Background

One in every 10,000 people per year are diagnosed with schizophrenia, with a lifetime prevalence of about 1% (Jablensky 1992). It often runs a chronic course with acute exacerbations and often partial remissions. The antipsychotic group of drugs is the mainstay treatment for this illness (Dencker 1980). These are generally regarded as highly effective, especially in controlling such symptoms as hallucinations and delusions (Kane 1998). They seem to reduce the risk of acute relapse. A systematic review undertaken over a decade ago suggested that, for those with serious mental illness, stopping anti‐psychotics resulted in 58% of people relapsing, whereas only 16% of those who were still on the drugs became acutely ill within a one year period (Davis 1977). Evidence also points to the fact that experiencing a relapse of schizophrenia lowers a person's level of social functioning and quality of life (Curson 1985). Relapse prevention also has enormous financial implications. For example, within the UK, a Department of Health burden of disease analysis in 1996 indicated that schizophrenia accounted for 5.4% of all National Heath Service in‐patient expenditure, placing it behind only learning disability and stroke in magnitude (DoH 1996).

Antipsychotic drugs are usually given orally (Aaes‐Jorgenson 1985) but compliance with medication may be difficult to quantify. Problems with treatment adherence are common throughout medicine (Haynes 1979). Those who suffer from long term illnesses such as schizophrenia, where the treatments may have uncomfortable side effects (Kane 1998) and individuals have cognitive impairments (David 1994) and erosion of insight, are especially prone to not take medication on a regular basis. The development of depot injections in the 1960s and initial clinical trials (Hirsch 1973) gave rise to extensive use of depots as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment. Depots mainly consist of an ester of the active drug held in an oily suspension. This is injected intramuscularly and is slowly released. Depots may be given approximately every 2 to 4 weeks. Individuals may be maintained in the community with regular injections administered by community psychiatric nurses, sometimes in clinics set up for this purpose (Barnes 1994).

Fluspirilene decanoate belongs to the dephenylbutylpiperidine class of drugs. It differs from other depots because it is not added to (esterified with) an inert fatty acid. It can be directly administered intramuscularly, allowing gradual absorption of the active drug. It is given once weekly and it has been suggested that it improves psychotic symptoms and social behaviour (Chouinard 1971). We have tried to obtain data on its prevalence of use for schizophrenia but have been unsuccessful; any information relating to its frequency of use would be most welcome. It appears to be used in Germany to treat anxiety disorders (Schmidt 1989) but fell out of favour in some centres due to reports of local injection site reactions (McGee 1983). Fluspirilene decanoate used to be marketed in the UK under the trade name Redeptin by Smith‐Kline French. However, since 1993 its production in the UK has ceased, though it is possible to import it on a patient‐ prescription basis. It is, however, in use in countries like Argentina, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Holland, Ireland and Israel. That makes up approximately 190 million people. This implies that fluspirilene decanoate is available to approximately 3% of the total world population.

Objectives

To review the effects of depot fluspirilene versus placebo, oral anti‐psychotics and other depot antipsychotic preparations for people with schizophrenia in terms of clinical, social and economic outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a study was described as 'double‐blind' and it was implied that the study was randomised, and where the demographic details of each group's participants were similar, trials were included. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

People with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders, irrespective of mode of diagnosis, age, ethnicity and sex. We included studies describing the participant group as suffering from 'serious mental illnesses' without stating a particular diagnostic grouping. The exception to this rule was when the majority of those randomised clearly did not have a functional, non‐affective, psychotic illness.

Types of interventions

1. Fluspirilene decanoate: any dose 2. Placebo 3. Oral anti‐psychotic drugs: any dose 4. Other depot antipsychotic drugs: any dose.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were:

1. Death, suicide or natural causes

2. Leaving the study early

3. Clinical response 3.1 Relapse* 3.2 Clinically significant response in global impression ‐ as defined by each of the studies* 3.3 Average score/change in global impression 3.4 Clinically significant response on psychotic symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.5 Average score/change on psychotic symptoms 3.6 Clinically significant response on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.7 Average score/change in positive symptoms 3.8 Clinically significant response on negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.9 Average score/change in negative symptoms

4. Extrapyramidal side effects 4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects

5. Other adverse effects, general and specific

6. Service utilisation outcomes 6.1 Hospital admission* 6.2 Days in hospital

7. Economic outcomes

8. Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers 8.1. Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Average score/change in quality of life/satisfaction

Outcomes were grouped into immediate (0‐5 weeks), short term (6 weeks‐5 months), medium term (6 months‐1 year) and longer term (over 12 months).

* Primary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

1. Electronic searches for the 2006 update: 1.1 We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (May 2006) using the phrase:

[(fluspiril* or redeptin* or imap* or spirodifl* or kivat* in REFERENCES title, abstract and indext fields) OR (fluspiril* or redeptin* or imap* or spirodifl* or kivat* in STUDY interventions field)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Electronic searches for the first 1999 version of this review

2.1 We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 1998) using the phrase:

(FLUSPIR* and DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG and ACTING) or (DELAY* and ACTION)) and (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN* )) or (#44=58 and #44=544)

#44 is the field in the register that contains intervention codes and 58 and 544 are codes for fluspirilene.

2.2 We searched the Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (FLUSPIR* next DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG next ACTING) or (DELAY* next ACTION)) next (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN* )) or (FLUSPIRILENE* ME and DELAYED‐ACTION‐PREPARATIONS* ME))]

2.3 We searched Biological Abstracts (January 1982 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (FLUSPIR* near1 DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN* ))]

2.4 We searched EMBASE (January 1980 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (FLUSPIR* near1 DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN* )) or "FLUSPIRILENE‐DECANOATE"/ all subheadings]

2.5 We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (FLUSPIR* near1 DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN* )) or ("FLUSPIRILENE‐DECANOATE"/ all subheadings and explode "DELAYED‐ACTION‐PREPARATIONS"/ all subheadings))]

2.6 We searched PsycLIT (January 1974 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (FLUSPIR* near1 DECANOATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (FLUSPIR* or IMAP* or REDEPTIN*))]

3. Reference searching We inspected reference lists of all identified trials for further studies and each of the included studies was sought as a citation on the SCISEARCH database. Reports of articles citing these studies were inspected in order to identify further trials.

4. Personal contact We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials. Also companies producing depots were contacted for published and unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Study selection AA inspected all identified citations or studies. CEA re‐inspected a randomly selected sample (10%) of all reports to ensure selection reliability. Where disagreement occurred attempts were made to resolve this by discussion, where doubt still remained we acquired the full article for further inspection. AA and CEA independently decided whether the selected studies met the review criteria. Again, where disagreement occurred attempts were made to resolve this through discussion; if doubt still remained we added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment pending acquisition of further information.

2. Assessment of methodological quality We allocated trials to three quality categories, as described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2005). When disputes arose as to which category a trial should be allocated, again resolution was attempted by discussion. When this was not possible we did not enter the data and the trial was added to the list of those awaiting assessment until further information could be obtained. We assessed the methodological quality of included trials in this review using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2005). It is based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect (Schulz 1995). The categories are defined below:

A. Low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment) B. Moderate risk of bias (some doubt about the results) C. High risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment).

For the purpose of the analysis in this review update, trials were included if they met the Cochrane Handbook criteria A or B.

3. Data extraction AA and CEA independently extracted data from selected trials. When disputes arose, we attempted to resolve them by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and this outcome was added to the list of those awaiting assessment.

4. Data synthesis 4.1 Data types We assessed outcomes using continuous (for example changes on a behaviour scale), categorical (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as 'little change', 'moderate change' or 'much change') or dichotomous (for example, either 'no important changes' or 'important changes' in a person's behaviour) measures. Currently RevMan does not support categorical data so we were unable to analysis this.

4.2 Incomplete data We did not include trial outcomes if more than 40% of people were not reported in the final analysis.

4.3 Dichotomous ‐ yes/no ‐ data We carried out an intention to treat analysis. On the condition that more than 60% of people completed the study, everyone allocated to the intervention were counted, whether they completed the follow‐up or not. It was assumed that those who dropped out had the negative outcome, with the exception of death. Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. If the authors of a study had used a predefined cut off point for determining clinical effectiveness we used these where appropriate. Otherwise it was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score, this could be considered as a clinically significant response. Similarly, a rating of 'at least much improved' according to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (Guy 1976) was considered as a clinically significant response.

The relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated based on the random effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios which tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. We inspected data to see if an analysis using a fixed effects model made any substantive difference in outcomes that were not statistically significantly heterogeneous. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number‐needed‐to‐harm (NNH).

4.4 Continuous data 4.4.1 Normally distributed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale started from the finite number (such as zero), the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them.

For change data (endpoint minus baseline), the situation is even more problematic. In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if data are skewed, though this is likely. After consulting the ALLSTAT electronic statistics mailing list, the reviewers presented change data in MetaView in order to summarise available information. In doing this, it was assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analyses could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Without individual patient data it is impossible to test this assumption. Where both change and endpoint data were available for the same outcome category, only endpoint data were presented. We acknowledge that by doing this much of the published change data were excluded, but argue that endpoint data is more clinically relevant and that if change data were to be presented along with endpoint data, it would be given undeserved equal prominence. Authors of studies reporting only change data are being contacted for endpoint figures. Non‐normally distributed data were reported in the 'other data types' tables.

4.4.2 Rating scales: A wide range of instruments are available to measure mental health outcomes. These instruments vary in quality and many are not valid, or even ad hoc. For outcome instruments some minimum standards have to be set. It has been shown that the use of rating scales which have not been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000) are associated with bias, therefore the results of such scales were excluded. Furthermore, we stipulated that the instrument should either be a self report or be completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist), and that the instrument could be considered a global assessment of an area of functioning. However, as it was expected that therapists would frequently also be the rater, such data were included but commented on as 'prone to bias'.

Whenever possible we took the opportunity to make direct comparisons between trials that used the same measurement instrument to quantify specific outcomes. Where continuous data were presented from different scales rating the same effect, both sets of data were presented and the general direction of effect inspected.

4.4.3 Summary statistic For continuous outcomes we estimated the weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups, again based on the random effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity.

4.4.4 Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997,Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

5. Investigation for heterogeneity Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. Then we visual inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented using, primarily, the I‐squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I‐squared estimate was greater than or equal to 75%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). If inconsistency was high, we did not summate data, but presented the data separately and investigated the reasons for heterogeneity.

6. Addressing publication bias We entered data from all identified and selected trials into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias.

7. General Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for fluspirilene.

Results

Description of studies

Please see Excluded and Included Studies Table.

1. Excluded studies Seventeen studies were excluded (including the 5 studies excluded in the original 1999 review) as they were not randomised. Winter 1973 was clearly relevant but it was impossible to use any data. Attempts are being made to contact the authors but it is unlikely that any data will be found. Eight studies were not randomised, five did not fit the intervention criteria, and four studies did not have any extractable data.

2. Studies awaiting assessment One study (Pluymakers 1971), the reference to which was obtained from one of our included studies, claims to be an RCT according to the title. We are attempting to acquire the study report.

3. Ongoing studies We are not aware of any studies that are ongoing.

4. Included studies We identified 12 studies in total for inclusion, five additional studies were added during this 2006 update. All were randomised studies.

4.1 Duration One study (Chouinard 1986) was of immediate term duration (4 weeks), but most trials (n=8) were short term lasting between 6 weeks to 5 months. Two studies (Magnus 1979 and Russell 1982) were medium term, both six months duration. Malm 1974 was the only longer term study lasting two years.

4.2 Participants All participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia or some other similar psychotic disorder. Most of the studies included people of both sexes although one study included only women (Vereecken 1972). Galfi 1973, Magnus 1979 and Tegeler 1979 failed to mention the sex of the participants. Age ranged between 16 and 80 years. The majority of those who participated had long histories of illness.

4.3 Setting The trials were based in hospital but Magnus 1979 used participants from both hospital and community settings. Russell 1982 and Villeneuve 1970 failed to mention the setting used.

4.4 Study size All studies were underpowered with sample sizes per study ranging from 24 to 62 participants.

4.5 Interventions One trial compared fluspirilene (Galfi 1973) with placebo. Two trials compared fluspirilene (Bankier 1973 and Chouinard 1986) with oral antipsychotic. Nine other studies compared fluspirilene with other depot formulations and, lastly, Borger 1978 compared two different frequencies of administration.

4.6 Outcomes Apart from leaving the study early and use of additional medication, most outcomes, even those later dichotomised, were measured on the rating scales listed below. Many of the trials presented their findings in graphs or by p‐values alone. Graphical presentation made it impossible to acquire raw data for synthesis. Requests for raw data from authors have so far failed. Often studies reported p‐values as a measure of association between intervention and outcomes instead of showing the strength of the association.

4.6.1 Outcome scales:

4.6.1.1 Global functioning 4.6.1.1.1 Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) A rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. Angst 1973, Borger 1978, Frangos 1978, Galfi 1973, Tegeler 1979 and Villeneuve 1970 reported data from this scale.

4.6.1.2 Adverse effects 4.6.1.2.1 Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale ‐ EPRS (Chouinard 1980) This consists of a questionnaire relating to parkinsonian symptoms (nine items), a physician's examination for parkinsonism and dyskinetic movements (eight items), and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. High scores indicate severe levels of movement disorder. Magnus 1979 reported data from this scale.

4.6.1.2.2 AMP‐System (Ban 1978) The German psychiatrists collaborating in the Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Neuro‐Psychopharmakologie (AGNP) designed a system for drug studies. The AMP system is a multiple page, optical mark reader scale, comprehensively covering the entire field of psychiatric symptomatology and side effects, including full EPS documentation. Rating is along a five step severity scale. On the forms, the items are arranged in functional categories. Computer systems are available for the evaluation of efficacy as well as for the evaluation of relationships between drug response and 1) diagnostic groups, 2) socio‐economic groups 3) other symptoms or symptom clusters. Angst 1973 used this scale.

4.7 Missing outcomes. None of the studies evaluated hospital/service outcomes, satisfaction with care and economic outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation Frangos 1978 and Magnus 1979 were the only studies to specify how participants were allocated to interventions (randomisation code, and pre‐arranged prescribing list respectively). As poor reporting of randomisation has consistently been associated with an overestimate of effect (Schulz 1994) all allocation concealment has been rated as 'unclear' or quality 'B'. The results in these trials are likely to be a 30‐40% overestimate of effect (Schulz 1994; Moher 1998).

2. Blinding at outcome Eight studies were described as double blind. Of those authors who stated that a double blind procedure was undertaken none reported this being tested. The two questions, one to the participant ‐ "what do you think you have been given?" and one to the rater ‐ "what drug do you think this person was allocated?" would have clarified the situation. Failure to test double blinding may cast doubt on the quality of trial data. One study (Magnus 1979) was open label and two studies (Tegeler 1979 and Villeneuve 1970) did not report whether blinding was used. Bankier 1973 reported using identical capsules but did not clarify whether double blinding was used.

3. Loss to follow‐up Five studies did not report numbers of participants completing the study, or data were presented in such a way to make calculations impossible. Vereecken 1972 reported no people leaving the study early when comparing fluspirilene decanoate with another depot. Borger 1978 assessed varying interval times between injections of fluspirilene and reported one person dropping out from the group administered the drug biweekly. Overall, attrition rates were low for fluspirilene versus oral antipsychotics (short term 8%,1 RCT) and also for the fluspirilene versus other depot antipsychotics comparison (medium term 5%, 3 RCTs).

Effects of interventions

1. The search The search (2006) produced 21 citations and we were able to include five additional studies during the 2006 update. The review has a total of 12 relevant randomised controlled trials with a total of 489 participants. Seventeen trials did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Table of Excluded Studies).

2. COMPARISON 1: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus PLACEBO

For this 2006 update we identified Galfi 1973, a small (n=60) short term study.

2.1 Global impression We found CGI scores 'no important improvement' were not significantly different (Galfi 1973, n=60, RR 0.97 CI 0.9 to 1.2) at short term assessment.

2.2 Adverse effects Movement disorders were found exclusively in those allocated to fluspirilene (Galfi 1973,n=60, RR 31.0 CI 1.9 to 495.6, NNH 4 CI 2 to 107,assume baseline risk =1%).This is of statistical significance, though the confidence intervals are very wide.

3. COMPARISON 2: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

In this 2006 update we identified Bankier 1973, a small (n=24) short term study.

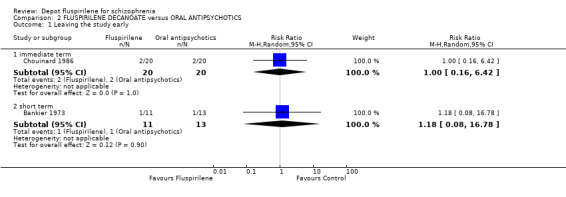

3.1 Leaving the study early Attrition rates for both immediate (Chouinard 1986) and short term (Bankier 1973) data were low, with all outcomes being equivocal.

3.2 Mental state: Relapse Taking into consideration our pre‐designed protocol, we assumed and counted the unexplained departure of participants from studies as relapses. Both immediate term data (Chouinard 1986, n=40, RR 0.50 CI 0.1 to 5.1) and short term data (Bankier 1973, n=24, RR 1.18 CI 0.1 to 16.8) are equivocal.

3.3 Adverse effects 3.3.1a Movement disorders ‐ needing anticholinergic drugs We found immediate term data from the Chouinard 1986 study to be non‐significant, although data almost reached statistical significance (p=0.05, n=40, RR 1.36 CI 1.0 to 1.8). Short term data were also not significantly different (Bankier 1973, n=24, RR 0.07 CI 0.0 to 1.1) between depot fluspirilene and those given oral antipsychotics.

3.3.1b Movement disorders‐ oculogyric crises and extreme restlessness Only Bankier 1973 reported on this specific movement disorder and data were not significantly different between treatment groups.

3.3.2 Specific others We found data reported by Chouinard 1986 for frequency of dizziness (RR 0.59 CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNH 3 CI 2 to 24), drowsiness (RR 0.42 CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNH 2 CI 2 to 4) and dry mouth (RR 0.21 CI 0.1 to 0.6, NNH 2 CI 2 to 4) were significantly greater in the control group who were given chlorpromazine, but these results are based upon a sample of just 40 participants.

4. COMPARISON 3: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS

We identified two new studies(Tegeler 1979 and Villeneuve 1970) in addition to the five studies which were included in the original review.

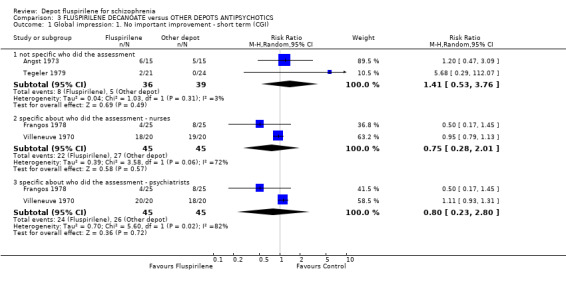

4.1 Global impression: No important improvement (Clinical Global Impression) ‐ short term We found data from two studies (Frangos 1978 and Villeneuve 1970) gave similar results on the CGI scale when assessed by psychiatrists (n=90, RR "no important improvement" 0.80 CI 0.2 to 2.8) and by nurses (n=90, RR "no important improvement" 0.75 CI 0.3 to 2.0). One would assume that discrepancies in the assessment made by the two types of personnel must have prompted the separate assessments to be observed. However, both assessments have provided extremely similar results: showing no important improvements in either intervention groups, in the short term. Data pooled from two studies (Angst 1973 and Tegeler 1979), analysed without specifying who the assessors were, also provided an equivocal result.

4.2 Global impression: Poor tolerability ‐ short term We found no significant differences for poor tolerability between treatment groups (Tegeler 1979, n=45, RR 2.29 CI 0.2 to 23.4).

4.3 Mental state Delusions were reported in most participants but no significant differences occurred between groups (Vereecken 1972, n=23, RR 1.09 CI 0.8 to 1.4). Hallucinations were also equivocal (Vereecken 1972, n=26, RR 1.10 CI 0.8 to 1.6). We found no significant differences in relapse rates between the depot fluspirilene and other depot antipsychotics group (n=109, 3 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.1 to 2.3).

4.4 Leaving the study early Four studies (2 short term and 2 medium term) reported on patients leaving the study early. We found data to be equivocal at both short and medium term outcome.

4.5 Adverse effects 4.5.1 Anticholinergic effects Three studies reported on visual disturbances, three on dry mouth and one on constipation but none are statistically significant.

4.5.2 Change in body weight One study (Vereecken 1972) reported data for weight change but scores had wide confidence intervals (skewed data) and are not shown graphically.

4.5.3 General unspecified Though three studies were reported to give significant data in the original review (using odds ratio), we having used relative risk rather than odds ratio as a statistical tool, have not found any statistically significant data.

4.5.4 Movement disorders Four studies (n=166) reported on extrapyramidal side effects being lower in the fluspirilene groups and provided statistically significant data (RR 0.50 CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNH 5 CI 4 to 12). We found no significant difference for 'needing anticholinergic drugs' (n=206, 5 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.3 to 1.1) between treatment groups. Four studies reported on incidence of tremors but data were equivocal. Only one study (Angst 1973) reported the following variables: akathisia, ataxia, muscular hypotony, paroxysmal dyskinesia. These were not significantly different across both groups in the short term. Two short term studies took into account symptoms of parkinsonism, but were not statistically significant (n=76, 2 RCTs, RR 0.68 CI 0.1 to 3.9).

4.5.5 Neurological defects The neurological defects 'muscular restlessness' and 'muscular rigidity' were not statistically significant by short term assessment.

4.5.6 Other problems Three studies (n=120) reported on 'sleep disturbance' and 'weakness/fatigue' but we found no significant difference between groups. One study (Villeneuve 1970) assessed nausea, and vomiting with a slightly higher prevalence in the fluspirilene groups, but data were not statistically significant. Other outcomes, arousal, 'sedation' and 'pain at injection site' were equivocal.

5. COMPARISON 4: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly versus biweekly

5.1 Global Impression: No important improvement (Clinical Global Impression) ‐ short term We found no significant difference in the global impression of patients (Borger 1978, n=34) between fluspirilene decanoate administered weekly and those injected every two weeks (RR 1.00 CI 0.8 to 1.3).

5.2 Mental state: Relapse ‐ short term Relapse rates between the two groups were comparable (Borger 1978, n=34, RR 3.00 CI 0.1 to 68.8).

5.3 Leaving the study early ‐ short term No significant differences in the numbers leaving early were found (Borger 1978, n=34, RR 3.00 CI 0.1 to 68.8).

5.4 Adverse effects: Movement disorders (general) ‐ short term We found no significant difference in the incidence of movement disorder between the groups (n=34, RR 0.57 CI 0.2 to 1.6).

6. Missing outcomes No study reported on hospital and service outcomes or commented on participants' overall satisfaction during or after the trial. Economic outcomes and death were not reported by any of the included studies.

Discussion

1. Generalisability of results Participants: The diagnoses were based on varied criteria (DSM II, DSM III, ICD‐9) but 9 out of the 12 included trials did not specify which diagnostic criteria were used. The failure of studies to report the diagnostic tool suggests that diagnoses could be heterogeneous. However, it must also be noted that operational criteria for diagnosis of schizophrenia, such as DSM III, exclude many people seen in routine practice who are being treated with anti‐psychotic medication for schizophrenia and other related disorders. The heterogeneity of diagnosis should increase external validity of the findings of this review. Where descriptions were available (4/13 trials) participants had long histories of schizophrenia (duration of illness ranged from 2‐34 yrs) and most were in hospital.

Compliance is currently a major concern in modern‐day treatments of schizophrenia. Observing the effect of oral and depot antipsychotic drugs in terms of clinical efficacy, side effects and social implications has a wide role to play in constructing a sound basis for the choice the clinician makes as to what medication to prescribe. The main benefit of depot formulations is that covert non‐compliance is eliminated and if relapse does occur under these circumstances then non‐compliance can be ruled out. However, those entered into clinical trials are usually the more compliant patients compared to those seen in 'real‐world' practice. This must compromise the applicability of the results into the community, where non‐compliance or failure to turn up to depot clinics is commonplace.

This review compared depot fluspirilene with placebo, oral antipsychotics or other depot formulations. The results of this review should be reasonably generalizable, especially to those with long‐term illnesses. As data on social functioning and quality of life are absent it is difficult to generalise from other results to comment on these important outcomes.

2. COMPARISON 1: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus PLACEBO

2.1 Global impression Updating this review in 2006 still identified studies from over three decades ago. This small, short study by Galfi 1973 was never powered to be able to really highlight clear differences as is illustrated by the no difference between placebo and the depot for the outcome of no important clinical improvement.

2.2 Adverse effects Even this small study does suggest that fluspirilene is a potent cause of movement disorders, with a rough estimate number‐needed‐to‐harm of only four (CI 2 to 107).

3. COMPARISON 2: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

3.1 Leaving the study early In the two trials presenting data on this comparison (Chouinard 1986 and Bankier 1973) there are no difference between the depot preparation and oral antipsychotics for the outcome of leaving the study early.

3.2 Mental state Relapse rates were low in the studies we were able to include and extract data from. No differences were found from limited data and it is not possible to draw any conclusions as to whether fluspirilene offers an advantage in the reduction of relapse compared with oral antipsychotics.

3.3 Adverse effects Again, data available were limited and we found no significant difference in needing anticholinergic drugs or frequency of movement disorders. Three adverse effects that were significantly higher in the oral antipsychotic group (chlorpromazine) were dizziness (NNH 3), drowsiness (NNH 2) and dry mouth (NNH 4). This antipsychotic (chlorpromazine) has a marked sedative and hypotensive adverse effects profile, and fluspirilene may offer a distinct advantage over chlorpromazine on these particular adverse effects.

4. COMPARISON 3: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS

4.1 Global impression Frangos 1978 (n=50, duration 16 weeks) and Villeneuve 1970 (n=40, duration 18 weeks) compared fluspirilene decanoate to fluphenazine and reported no difference in the rate of clinically important global improvement between groups at the end of the study (irrespective of who assessed the CGI). Similarly, data analysed without specifying who conducted the assessments (Angst 1973 and Tegeler 1979) were also non‐significant. This shows that in the short term, fluspirilene is no lesser effective than other depot antipsychotics (fluphenazine decanoate, perphenazine or fluphenazine enathate) in improving the global state. Tegeler 1979 was the only study reporting on poorer tolerability in the global state in the fluspirilene group, however, one study is insufficient to make any inference.

4.2 Mental state Delusions and hallucinations were not found to be significantly different and with such a small sample size (n=26) real clinical effects are unlikely to emerge. Counting participants leaving the study early, without any reason, as "relapses", we did not find any significant differences.

4.3 Leaving the study early Study retention was generally good and no differences were found between intervention groups for short (27%) and medium (8%) term study attrition rates. Depot fluspirilene was no better or worse, when interpreted as a proxy measure for treatment acceptability, than other depots antipsychotics.

4.4 Adverse effects: Anticholinergic effects were not found to be different between groups and larger studies of longer duration are needed to adequately assess this outcome. Unspecified general adverse effects were also equivocal (all three comparator groups used fluphenazine as the control), although if significant data were found it would have had limited clinical usefulness. Only one movement disorder (extrapyramidal side effects) was statistically significant, being lower in the depot fluspirilene group (NNH 5). Data came from four studies (Frangos 1978, Magnus 1979, Vereecken 1972 and Villeneuve 1970) and all but one (Villeneuve 1970) used fluphenazine as the control drug. However, all other measures of movement disorder were found to be equivocal including 'needing anticholinergic medication'. More robust data is needed to support this one significant result, given the other assessments of anticholinergic effects did not support this finding. Other adverse effects including muscular restlessness, rigidity, sleep, sedation, fatigue were limited by sample size and produced non‐significant results.

5. COMPARISON 4: FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs. biweekly

5.1 Global impression Only Borger 1978 (n=34, duration 12 weeks) compared weekly or biweekly fluspirilene decanoate. Clinical global Impression scores were not affected by the type of treatment scheduling with data being non‐significant.

5.2 Mental state Relapse data were also equivocal with only one participant (weekly group) experiencing a relapse.

5.3 Leaving the study early Again, data were equivocal with neither treatment schedule being significantly different.

5.4 Adverse effects We found movement disorders were not significantly different but with sample sizes of only 17 for each treatment group the chances of a significant difference being found are limited.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For clinicians Whether depot fluspirilene is more beneficial than placebo is not known. Currently the choices of whether to give fluspirilene depot or oral medication must be based on personal preference, clinical judgement and non‐trial based evidence. There is no trial evidence that fluspirilene depot is worse or better than other depot preparations so, again, personal preference and clinical judgement must guide choice.

2. For those with schizophrenia No convincing differences are evident when comparing depot fluspirilene with oral antipsychotic drugs or with other depot formulations. There are no discernible differences, illustrated within clinical trials, between the different depots in terms of clinical improvement, acceptability of treatment, or severity of adverse effects. This does not mean that real differences do not exist. Most studies and summations of studies contained too few participants to be able to identify anything but gross differences. Currently the choice to prescribe depot or not could be based on patient or clinician preference as could the decision regarding which depot to use.

3. For managers or policy makers No direct data on hospital and services outcomes, satisfaction with care or economics are available. If depot formulations do promote compliance and this leads to a reduction in relapses, this would have important implications for patients and the establishments that care for them. Any suggestion that fluspirilene depot reduces relapse and hospital care is not based on trial data.

Implications for research.

1. General If the recommendations of the CONSORT statement (Begg 1996) had been anticipated by trialists much more data would have been available to inform practice. Only two out of 12 included studies specified how participants were allocated to treatment. Allocation concealment is essential for the result of a trial to be considered valid and gives the assurance that selection bias is kept to the minimum. Well described and tested blinding could have encouraged confidence in the control of performance and detection bias. It is also important to know how many, and from which groups, people were withdrawn, in order to evaluate exclusion bias. It would have been helpful if authors had presented data in a useful manner which reflects association between intervention and outcome, for example, relative risk, odds‐ratio, risk or mean differences, as well as raw numbers. Binary outcomes should be calculated in preference to continuous results, as they are easier to interpret. If p‐values are used, the exact value should be reported.

2. Specific This review update highlights the need for good, 'real world' clinical trials (Simon 1995) to investigate the effects of using depot fluspirilene for those with schizophrenia. This depot compound has not been adequately evaluated by modern standards. More trials for this depot preparation are needed to assess clinical outcomes, social and cognitive functioning and adverse effects. Future studies should randomise within a 'real world' care setting, and report service utilisation data, as well as satisfaction with care and economic outcomes. For a suggested design of future studies please see Table 1.

1. Suggested design for future studies.

| Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Allocation: randomised, explicit description. Blindness: double, and tested. Duration: 1 year at least. | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (any criteria). History: acute and chronic episodes. N=300.* Age: mean˜ 44.15 years, range :(31.4‐58.4) years. Sex: 150M,150F. Setting: hospitalised. | 1. Fluspiriline decanoate: dose 1.5 to 13 mg/IM/wk.N=150. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate:12.5 to 100 mg/IM/wk.N=150 | 1. Not improved to an important extent (CGI).* 2. Healthy days.Quality of life / satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers 3. Mental state. 4. Relapses. 5. Extrapyramidal side effects 5.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 5.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects | * number needed to identify difference of 20% in binary outcome with reasonable level of probability. |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 May 2012 | Amended | Additional table linked to text |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1999 Review first published: Issue 3, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 23 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 November 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group internal peer review complete (see Module). External peer review scheduled.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Rathbone for editing the entire update and useful comments. Daniela Faldus, without whose help we couldn't have extracted data from the Czech papers. Many thanks to Janssen‐Cilag , medical department and especially to Clive Rogers for information about fluspirilene marketing in the UK as well as for reference to one of the trials conducted on fluspirilene. We would also like to thank Seema Quraishi for her previous contributions to the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus PLACEBO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global impression: No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI) | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.86, 1.08] |

| 2 Adverse effects: Movement disorders ‐ short term | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 31.0 [1.94, 495.61] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Global impression: No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Adverse effects: Movement disorders ‐ short term.

Comparison 2. FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 immediate term | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.42] |

| 1.2 short term | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.08, 16.78] |

| 2 Mental state: Relapse | 2 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.13, 4.16] |

| 2.1 immediate term | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 5.08] |

| 2.2 short term | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.08, 16.78] |

| 3 Adverse effects: 1a. Movement disorders ‐ needing anticholinergic drugs | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 immediate term | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [1.00, 1.84] |

| 3.2 short term | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.00, 1.07] |

| 4 Adverse effects: 1b. Movement disorders ‐ occulogyric crisis and extreme restlessness ‐ short term | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.5 [0.16, 78.19] |

| 5 Adverse effects: 2. Specific others ‐ immediate term | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 dizziness | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.37, 0.95] |

| 5.2 drowsiness | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.24, 0.73] |

| 5.3 dry mouth | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.07, 0.63] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Mental state: Relapse.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Adverse effects: 1a. Movement disorders ‐ needing anticholinergic drugs.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: 1b. Movement disorders ‐ occulogyric crisis and extreme restlessness ‐ short term.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: 2. Specific others ‐ immediate term.

Comparison 3. FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global impression: 1. No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 not specific who did the assessment | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.53, 3.76] |

| 1.2 specific about who did the assessment ‐ nurses | 2 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.28, 2.01] |

| 1.3 specific about who did the assessment ‐ psychiatrists | 2 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.23, 2.80] |

| 2 Global impression: 2. Poor tolerability ‐ short term | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.29 [0.22, 23.44] |

| 3 Mental state | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 delusion | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.82, 1.44] |

| 3.2 hallucinations | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.75, 1.60] |

| 3.3 relapse | 3 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.14, 2.27] |

| 4 Leaving the study early | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 short term | 2 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.43, 1.80] |

| 4.2 medium term | 2 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.14, 2.27] |

| 5 Adverse effects: 1. Anticholinergic effects | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 constipation ‐short term | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.47, 3.09] |

| 5.2 dry mouth | 3 | 106 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.07, 48.04] |

| 5.3 visual disturbances ‐short term | 3 | 106 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.34, 5.76] |

| 6 Adverse effects: 2. Change in body weight ‐ short term (skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7 Adverse effects: 3. General unspecified | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 short term | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.52, 1.01] |

| 7.2 medium term | 2 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.12, 4.00] |

| 8 Adverse effects: 4. Movement disorders | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 akathesia | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.05, 4.94] |

| 8.2 ataxia ‐short term | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 3.85] |

| 8.3 extrapyramidal side effects | 4 | 166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.32, 0.79] |

| 8.4 muscular hypertony‐short term | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.42, 2.40] |

| 8.5 needing anticholinergic drugs‐reason unspecified | 5 | 206 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.27, 1.09] |

| 8.6 parkinsonism ‐short term | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.12, 3.91] |

| 8.7 paroxysmal dyskinesia ‐short term | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.48, 5.76] |

| 8.8 tremor | 4 | 146 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.61, 1.64] |

| 9 Adverse effects: 5. Neurological defects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 muscular restlessness ‐short term | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.44 [0.52, 3.97] |

| 9.2 muscular rigidity ‐short term | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.57, 3.33] |

| 10 Adverse effects: 6. Other problems ‐ short term | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 arousal ‐ sedation | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.34] |

| 10.2 arousal ‐ sleep disturbance | 3 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.55, 1.79] |

| 10.3 gastric ‐ nausea | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.5 [0.83, 14.83] |

| 10.4 gastric ‐ vomiting | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.69, 13.12] |

| 10.5 others ‐ pain at injection site | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.6 others ‐ weakness/fatigue | 3 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.55, 5.49] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Global impression: 1. No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Global impression: 2. Poor tolerability ‐ short term.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Mental state.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Leaving the study early.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: 1. Anticholinergic effects.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 6 Adverse effects: 2. Change in body weight ‐ short term (skewed data).

| Adverse effects: 2. Change in body weight ‐ short term (skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| Vereecken 1972 | Fluspirilene decanoate | ‐1.13 | 2.22 | 13 |

| Vereecken 1972 | other depot antipsychotics | ‐0.68 | 3.65 | 13 |

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 7 Adverse effects: 3. General unspecified.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 8 Adverse effects: 4. Movement disorders.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 9 Adverse effects: 5. Neurological defects.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus OTHER DEPOTS ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 10 Adverse effects: 6. Other problems ‐ short term.

Comparison 4. FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs biweekly.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global impression: No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI) | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.78, 1.28] |

| 2 Mental state: relapse ‐ short term | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 68.84] |

| 3 Leaving the study early ‐ short term | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 68.84] |

| 4 Adverse effects: Movement disorders ‐ general ‐ short term | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.20, 1.60] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs biweekly, Outcome 1 Global impression: No important improvement ‐ short term (CGI).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs biweekly, Outcome 2 Mental state: relapse ‐ short term.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs biweekly, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early ‐ short term.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 FLUSPIRILENE DECANOATE versus INTERVAL STUDIES ‐ weekly vs biweekly, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: Movement disorders ‐ general ‐ short term.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Angst 1973.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 3 months (pre‐trial fluspirilene administered to all). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: acute and chronic episodes. N=30. Age: mean 44.15, range 31‐58 years. Sex: 15 M,15 F. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose mean ˜ 4 mg/IM/week. N=15. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean ˜25 mg/IM/3 weeks. N=15. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Global impression: CGI.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal (AMP‐System), vegetative side effects. Unable to use ‐ Parkinson scale (no usable data). Laboratory investigations (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bankier 1973.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: unclear, identical tablets. Duration: 16 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: acutely disturbed. N=24. Age: ˜33 years. Sex: 9 M,15 F. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose mean ˜ 6.5 mg/IM/week+ placebo/p.o/day. N=11. 2. Trifluoperazine: dose mean ˜40 mg p.o/b.d+ placebo/IM/week. N=13. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects, oculogyric crisis with extreme restlessness. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Behaviour: NOSIE (no SD). Laboratory studies (no usable data). Body weight, BP, ECG (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Borger 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 12 weeks (preceded by 6 weeks of individually adjusted doses). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: hospitalisation 1‐46 years. N=34. Age: range 16‐80 years. Sex: 20 M, 14 F. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose range 1‐20 mg/IM/biweekly. N=17. 2. Fluspirilene: dose range 1‐20 mg/IM/weekly. N=17. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Global Impression: CGI.

Adverse effects. Unable to use ‐ Social functioning: PUK [Psychiatrische Universiteits Kliniek Scale Rating Scale] (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chouinard 1986.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 4 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM III). History: informed consent given. N=40. Age: mean 40 years, range 18‐60. Sex: 20 M, 20 F. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose range 11‐23 mg/IM/week + chlorpromazine placebo tablets. N=20. 2. Chlorpromazine: dose range 370‐720 mg, p.o/b.d+ fluspirilene placebo injections. N=20. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects, others (drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness). Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Global impression: CGI (no SD). Plasma Prolactin Concentration. (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Frangos 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised by "randomisation code". Blindness: double. Duration: 16 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: 2 year hospitalisation period. N=50. Age: mean 44.2 years, range 21‐62. Sex: 25 M, 25 F. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene decanoate: dose mean 12 mg/IM/week, range 2‐20 mg/IM. N=25. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean 76 mg/IM/biweekly, range 25‐150 mg/IM + placebo biweekly. N=25. | |

| Outcomes | Global Impression: CGI.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects, anticholinergic effects, others. Unable to use ‐ Leaving the study early (no clear data). Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Behaviour: NOSIE‐30 (no SD). Adverse effects: antipsychotic effects (no SD). |

|

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Galfi 1973.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (crossover). Blindness: double. Duration: 5 months (2 periods‐ 10 weeks each). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: not reported. N=60. Age: mean 38 years. Sex: not reported. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose 1.5 mg to 13 mg/week, up to 8th week then 13 mg/week. N=30. 2. Placebo (sodium chloride). N=30. | |

| Outcomes | Global Impression: CGI.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal. Unable to use ‐ Leaving the study early. (no clear data). Psychological investigations. (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Magnus 1979.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised by "pre‐arranged prescribing list". Blindness: open. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: newly admitted patients with 1st illness/relapses. N=50. Sex: not reported Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose range 6‐12 mg/IM/week. N=24.

2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 50‐100 mg/IM/2‐3 weeks. N=26. Individually adjusted doses. |

|

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects, requiring anticholinergics‐ using EPRS scale. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Behaviour: NOSIE (no SD). Social function: Wing's Rating Scales (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Malm 1974.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 25 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: duration ill mean 15 years, range 2‐39. N=62*. Age: 18‐65 years. Sex: 21 M, 36 F. Setting: hospitalised (multicenter). | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose mean 5.7 mg/IM/week, range 1‐14 mg. N=31*.

2. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose mean 28.5 mg/IM/biweekly, range 7.5‐50 mg. N=26. Chlormethiazole for antiparkinsonism. |

|

| Outcomes | Adverse effects: additional medication (anticholinergic drugs). Unable to use ‐ Leaving the study early. (no clear data). Ward behaviour: ADL (no data). Symptoms: S‐Scale (no data). Adverse effects: SE scale (no SD). Physiological responses. (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | Denominators are in question. * five participants not accounted for after randomisation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Russell 1982.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (ICD‐9). History: duration ill 9 years, informed consent. N=33. Age: mean ˜36 years. Sex: male and female. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene decanoate: dose mean 3 mg/IM/week, maximum 10.94 mg/IM. N=20. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean 12.5 mg/IM/2‐3 wks, maximum 25.5 mg/IM + placebo. N=13. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Global Impression: CGI (no SD). Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Adverse effects: Simpson & Angus (no data). Behaviour: MACC Behavioural Adjustment Scale (no data). |

|

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Tegeler 1979.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: not stated. Duration: 15 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (ICD). History: 9‐10 years recurrent illness. N=45. Age: 21‐62 years. Sex: not reported. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose 8 mg/week. N=21.

2. Perphenazine onanthat: dose 100 mg/biweekly with placebo biweekly. N=24. Biperiden for extrapyramidal side effects; nitrazepam for sleep disturbance. |

|

| Outcomes | Global Impression: CGI, tolerability. Unable to use ‐ Leaving the study early. (no clear data). Mental state: AMP System, PD‐S Paranoid ‐Depressive‐Scale von v. Zerssen (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Vereecken 1972.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 11 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II). History: duration ill mean 34 years, all on depot prior to trial. N=26. Age: mean 49 years, range 25‐75. Sex: all female. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene: dose mean 10.77 mg/IM/week. N=13.

2. Pipothiazine undecylenate: dose mean 103.8 mg/IM/biweekly+placebo. N=13. Doses individually tailored; antiparkinsonian agents:dexetimide, R16470,orphenadrine. |

|

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Mental state: Harris scale.

Occupational behaviour: Harris Scale.

Adverse effects: additional medication, pain at injection site, list, body weight. Unable to use ‐ Occupational therapy: "two ergotherapeutic rating scales" (no numerical data). Blood samples. (no numerical data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Villeneuve 1970.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: not mentioned. Duration: 18 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: not reported. N=40. Age: mean 43 years, range 33‐53. Sex: 21 M, 19 F. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Fluspirilene decanoate: dose mean 6.6 mg/IM/week. N=20. 2. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose mean 51.9 mg/IM/biweekly. N=20. | |

| Outcomes | Global Impression: CGI (Psychiatrist's assessment and Nurse's assessment).

Adverse effects: extrapyramidal side effects, neurovegetative disorders. Unable to use ‐ Leaving the study early. (no clear data). Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Behaviour: NOSIE (no SD). Adverse effects: EEG, ECG (no usable data). Laboratory findings. (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Diagnostic tools DSM ‐ Diagnostic Statistical Manual. ICD ‐ International Classification of Diseases.

Rating scales:

Global impression ‐ CGI ‐ Clinical Global Impression.

Mental state ‐ BPRS ‐ Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Behaviour ‐ NOSIE ‐ Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation.

Daily Functioning ‐ ADL ‐ Activities of Daily Living.

Adverse effects ‐ AIMS ‐ Abnormal Involuntary Movement Side effects. EPRS ‐ Extrapyramidal Side‐effects Rating Scale. UKU ‐ Side Effects Rating Scale.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Angst 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Chouinard 1983 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluspirilene versus chlorpromazine. Outcomes: no usable data. |

| Demerdash 1981 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Den Boer 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: ritanserin versus placebo. |

| Faltus 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Faltus 1976 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Gravem 1981 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Huygens 1973 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: dexetimide versus placebo. |

| Immich 1970 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Linden 1973 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluspirilene (oral) versus penfluridol. |

| Moller 2004 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: zotepine versus placebo. |

| Schmider 1999 | Allocation: unclear (crossover). Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: lorazepam versus oxazepam. |

| Skopova 1985 | Allocation: randomised (crossover). Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluspirilene versus fluspirilene dexetimide. Outcomes: no usable data. |

| Tanghe 1972 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Vereecken 1971 | Allocation: not clear. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluspirilene versus pipothiazine. Outcomes: no usable data. |

| Vranckx‐Haenen 1979 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Winter 1973 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluphenazine decanoate versus fluspirilene decanoate. Outcomes: no usable data. |

Contributions of authors

For the 2006 update:

Akhil Abhijnhan‐ undertook new searches, selected and acquired studies, extracted data, summated data, updated the text.

Anthony David‐ final editing of the text.

Clive Adams‐ double checked: selection and extraction of data, updated the text.

Mehmet Ozbilen‐extracted data from German studies and edited the text.

For the original review:

Seema Quraishi ‐ prepared protocol, undertook searches, selected and acquired studies, extracted data, summated data, produced report.

Anthony David ‐ acquired funding, helped prepare protocol, select studies, extract data, and produce the report.

Clive Adams ‐ acquired funding, helped prepare protocol and undertake searches, select and aquire studies, extract and summate data, and produce the report.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

NHS‐R&D Health Technology Assessment Programme, UK.

Declarations of interest

None.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Angst 1973 {published data only}

- Angst J, Frei M, Scharfetter C. The depot neuroleptic agent fluspirilene [Das Depotneurolepticum Fluspirilen. Klinische Pruefung im offenen Versuch und als Doppelblindstudie im Vergleich zu Fluphenazin Decanoat]. Pharmakopsychiatrie und Neuropsychopharmakologie 1973;6(1):13‐28. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bankier 1973 {published data only}

- Bankier RG. A comparison of fluspirilene and trifluoperazine in the treatment of acute schizophrenic psychosis. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and The Journal of New Drugs 1973;13(1):44‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borger 1978 {published data only}