Abstract

Background

Antipsychotic drugs are usually given orally but compliance may be problematic. The development of depot injections in the 1960s gave rise to their extensive use as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment. Pipotiazine palmitate is a depot from the phenothiazine family of antipsychotic drugs.

Objectives

To assess the clinical, social and economic effects of depot pipotiazine palmitate and undecylenate compared with placebo, oral antipsychotics and other depot antipsychotic preparations for people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

For this update we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 2003). We also inspected references of all identified trials for more studies and contacted relevant industries.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised clinical trials comparing depot pipotiazine palmitate and undecylenate to oral antipsychotics or other depot preparations for people with schizophrenia.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably selected, quality rated and independently extracted data from relevant studies. We calculated the random effects relative risk (RR), the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and, where possible the number needed to treat (NNT) on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we calculated weighted mean differences (WMD). We only presented scale data for those tools that had attained pre‐specified levels of quality.

Main results

When pipotiazine palmitate was compared with 'standard' oral antipsychotic no differences were found for outcomes of global impression (n=53, 1 RCT, RR 2.57, CI 0.8 to 8.6), relapse (n=124, 1 RCT, RR 1.55 CI 0.76 to 3.2), study attrition (n=219, 3 RCTs, RR 1.37 CI 0.8 to 2.4) and behaviour (n=124, 1 RCT, WMD 4.65, CI ‐1.1 to 10.4). There was also no reported difference in adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia or the need for anticholinergic drugs. Sixteen studies compared pipotiazine palmitate with other depot preparations (n=1123). Pipotiazine palmitate was consistently equivalent to other depots in terms of a range of outcomes, including global impression (n=217, 4 RCTs, RR not improved 0.99 CI 0.91 to 1.07), relapse (n=239, 5 RCTs, RR relapse by 1 year 0.98 CI 0.55 to 1.75), and adverse effects (n=337, 5 RCTs, RR needing anticholinergic medication 0.98 CI 0.84 to 1.15).

Authors' conclusions

Although well‐conducted and reported randomised trials are still needed to fully inform practice (no trial data exists reporting hospital and services outcomes, satisfaction with care and economics) pipotiazine palmitate is a viable choice for both clinician and recipient of care.

Plain language summary

Depot pipotiazine palmitate and undecylenate for schizophrenia

We undertook this review to determine the effects of pipotiazine palmitate for schizophrenia in comparison to placebo, other oral antipsychotics and other depot antipsychotics. We included results of 12 medium term trials, two long term trials, three short term trials and one trial that looked at immediate effects. We found that depot pipotiazine is effective for the treatment of schizophrenia, but overall was similar in effect to other depots and oral typical antipsychotic drugs.

Background

One in every 10,000 people per year is diagnosed with schizophrenia, with a lifetime prevalence of about 1% (Jablensky 1992). This illness often runs a chronic course with acute exacerbations and frequent partial remissions. Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay treatment for this illness (Dencker 1980b). These are generally regarded as highly effective, especially in controlling such symptoms as hallucinations and fixed false beliefs (delusions) (Kane 1998). They seem to reduce the risk of acute relapse. A systematic review undertaken over a decade ago suggested that, for those with serious mental illness, stopping antipsychotics resulted in 58% of people relapsing, whereas only 16% of those who were still on the drugs became acutely ill within a one year period (Davis 1986). Evidence also points to the fact that experiencing a relapse of schizophrenia lowers a person's level of social functioning and quality of life (Curson 1985). Relapse prevention also has enormous financial implications. For example, within the UK, a Department of Health burden of disease analysis in 1996 indicated that schizophrenia accounted for 5.4% of all National Heath Service in‐patient expenditure, placing it behind only learning disability and stroke in magnitude (DoH 1996).

Antipsychotic drugs are usually given orally (Aaes‐Jorgenson 1985) but compliance with medication given by this route may be difficult to quantify. Problems with treatment adherence are common throughout medicine (Haynes 1979). Those who suffer from long term illnesses such as schizophrenia where the treatments may have uncomfortable side effects (Kane 1998) and individuals have cognitive impairments (David 1994) and erosion of insight, are especially prone not to take medication on a regular basis. The development of depot injections in the 1960s and initial clinical trials (Hirsch 1973) gave rise to extensive use of depots as a means of long‐term maintenance treatment. Depots mainly consist of an ester of the active drug held in an oily suspension. This is injected intramuscularly and is slowly released. Depots may be given every one to six weeks. Individuals may be maintained in the community with regular injections administered by community psychiatric nurses, sometimes in clinics set up for this purpose (Barnes 1994).

This review of pipotiazine esters is one in a series investigating the effects of all depot antipsychotic preparations. The prevalence of use of the pipotiazine depots remains unknown despite contact with the company producing this preparation. We would welcome any information relating to the use of depot pipotiazine.

Technical background of Pipotiazine Pipotiazine (previous nomenclature Pipothiazine) is from the phenothiazine family and has a piperidine side chain. It is also known as 10‐[3‐[4‐(2‐hydroxyethyl)piperidino]propyl]‐N,N‐dimethyl‐phenothiazine‐2‐sulfonamide, pipotiazine, piportil and piportil Spécia. Its depot forms can be known as piportil longum‐4 (palmitate ester), piportyl palmitat, piportil depot (palmitate), lonseren (palmitate), piportil L 4 (palmitate ester), 19.552 RP, and piportil M 2 (undecylenate ester), 19.551 RP. Pipotiazine is a dopamine antagonist. Intervals between successive administrations of the palmitate depot are about four weeks, with peak levels after approximately two weeks. The undecylenate depot is no longer available (Reynolds 1993).

Objectives

To assess the effects of depot pipotiazine palmitate and undecylenate versus placebo, oral antipsychotics and other depot antipsychotic preparations for people with schizophrenia in terms of clinical, social and economic outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where a study was described as 'double‐blind' and it was implied that the study was randomised, and where the demographic details of each group's participants were similar, trials were included. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

Participants included people with schizophrenia or other similar psychotic disorders, diagnosed by any criteria, irrespective of gender, age or nationality. We included trials where a study described the participant group as suffering from 'serious mental illnesses' and did not give a particular diagnostic grouping. The exception to this rule was when the majority of those randomised clearly did not have a functional non‐affective psychotic illness.

Types of interventions

1. Pipotiazine palmitate: any dose 2. Pipotiazine undecylenate: any dose 3. Placebo 4. Oral antipsychotic drugs: any dose 5. Other depot antipsychotic drugs: any dose

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were grouped into immediate (0‐5 weeks), short term (6 weeks‐5 months), medium term (6 months‐1 year) and longer term (over 12 months).

Primary outcomes

1. Clinical response 1.1 Relapse

1.2 Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

2. Service utilisation outcomes 2.1 Hospital admission

Secondary outcomes

1. Death, suicide or natural causes

2. Leaving the study early

3. Clinical response 3.1 Average score/change in global state 3.2 Clinically significant response on psychotic symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.3 Average score/change on psychotic symptoms 3.4 Clinically significant response on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.5 Average score/change in positive symptoms 3.6 Clinically significant response on negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.7 Average score/change in negative symptoms

4. Extrapyramidal side effects 4.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs 4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects

5. Other adverse effects, general and specific

6. Service utilisation outcomes 6.1 Days in hospital

7. Economic outcomes

8. Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers 8.1 Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Average score/change in quality of life/satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Electronic searches for update (June 2003)

1.1 We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 2003) using the phrase:

[(pipotiazine* or piportil* or pipothiazine* in title) or (or * pipotiazine* or *piportil* or *pipothiazine*) and ((decanoate or (depot* or (long and acting) or (delay* and action)) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE) or (pipothiazine* or pipotiazin* in interventions of STUDY)]

The Schizophrenia Groups trials register is based on regular searches of BIOSIS Inside; CENTRAL; CINAHL; EMBASE; MEDLINE and PsycINFO; the hand searching of relevant journals and conference proceedings, and searches of several key grey literature sources. A full description is given in the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's module.

2. Details of previous searches

2.1. Electronic searching 2.1.1 We searched the Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (PIPOTHIA* next PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* next UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG next ACTING) or (DELAY* next ACTION)) next (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN* )) or (PIPOTHIAZINE* ME and DELAYED‐ACTION‐PREPARATIONS* ME))]

2.1.2 We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 1998) using the phrase:

(PIPOTHIA* and PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* and UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG and ACTING) or (DELAY* and ACTION)) and (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN* )) or (#44 =158 and #44 =703)

2.1.3 We searched Biological Abstracts (January 1982 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase: [and (PIPOTHIA* near1 PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* near1 UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN* ))]

2.1.4 We searched EMBASE (January 1980 to June 1998) was using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (PIPOTHIA* near1 PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* near1 UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN* )) or "PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE"/ all subheadings] or "PIPOTHIAZINE UNDECLEYNATE"/ all subheadings]

2.1.5 We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (PIPOTHIA* near1 PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* near1 UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN* )) or ("PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE"/ all subheadings and explode "DELAYED‐ACTION‐PREPARATIONS"/ all subheadings)) or ("PIPOTHIAZINE UNDECLYENATE"/ all subheadings and explode "DELAYED‐ACTION‐PREPARATIONS"/ all subheadings))]

2.1.6 We searched PsycLIT (January 1974 to June 1998) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for both randomised controlled trials and schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[and (PIPOTHIA* near1 PALMITATE) or (PIPOTHIA* near1 UNDECLYLENATE) or ((DEPOT* or (LONG near4 ACTING) or (DELAY* near2 ACTION)) near (PIPOTHIA* or PIPORTIL* DECANOATE* or PIPORTYL* PALMITATE* or LONSEREN*))]

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching We also inspected the references of all identified trials for more studies. We sought each of the included studies as a citation on the SCISEARCH database. We inspected reports of articles that had cited these studies in order to identify further trials.

2. Personal contact We contacted the first author of each included studyfor information regarding unpublished trials. 3. Drug companies We also contacted companies producing depots for published and unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Study selection The principle reviewer, David Anthony, (inspected all identified citations or studies. A randomly selected sample of 10% of all reports was re‐inspected by the secondary reviewer, Seema Quraishi, in order to ensure selection was reliable. Where disagreement occurred we resolved this by discussion, or where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, we independently decided whether they met the review criteria. If disagreement occurred, again we attempted to resolve this by discussion and when this was not possible sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment. For the update MD inspected all identified citations or studies.

2. Assessment of methodological quality We allocated trials to three quality categories as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Alderson 2004). When disputes arose as to which category a trial was allocated, again, we attempted resolution by discussion. When this was not possible, and further information was necessary, we did not enter data into the analyses and assigned the study to the list of those awaiting assessment. We only included trials in Category A or B in the review.

3. Data management 3.1 Data extraction We each independently extracted data. When further clarification was needed, we contacted the authors of trials to provide missing data. When disputes arose we attempted resolution by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter the data but added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

3.2 Intention to treat analysis Where more than 30% of those randomised were lost to follow‐up by six months, or 50% by beyond six moths, we felt that data were too prone to bias to use and did not report the findings. We presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis. We assumed that all those who were lost to follow up had the negative outcome, with the exception of the outcome of death. For example, for the outcome of relapse, those who were lost to follow up all relapsed.

4. Data analysis 4.1 Binary data For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the random effects risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). We also calculated the weighted number needed to treat statistic (NNT), and its 95% confidence interval (CI). If heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.2 Continuous data 4.2.1 Skewed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, the following standards were applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale started from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), it is difficult to tell whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. Skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants would have been entered in additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data poses less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large and would have been entered into a synthesis.

4.2.2 Summary statistic: for continuous outcomes a weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups was estimated. Again, if heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.2.3 Rating scales: A wide range of instruments is available to measure mental health outcomes. These instruments vary in quality and many are not valid, or are ad hoc. We included continuous data from rating scales only if: (a) the psychometric properties of the instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal; (b) the instrument is either: (¡) a self report, or (¡¡) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). Unpublished instruments are frequently employed and are more likely to represent statistically significant findings than those that have been put into print (Marshall 2000).

4.2.4 Endpoint versus change data: where possible we presented endpoint data and if both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcome then we reported only the former in this review.

4.2.5 Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

5. Test for inconsistency Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. We then visually inspected the graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented using, primarily, the I‐squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I‐squared estimate was greater than or equal to 75%, this was interpreted as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Data were then re‐analysed using a random effects model to see if this made a substantial difference. If it did, and results became more consistent, falling below 75% in the estimate, we added the studies to the main body of trials. If using the random effects model did not make a difference and inconsistency remained high, data were not summated, but were presented separately and reasons for heterogeneity investigated. (This paragraph has been reworded for the update of 2003 taking into account new developments in software and statistics.)

6. Addressing publication bias We entered data from all included studies into a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) in an attempt to identify the likelihood of significant publication bias (Egger 1997).

7. General Where possible, we entered data into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the treatment depots.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Included and Excluded studies table.

1. Excluded studies We excluded 31 studies from the review. Twenty three studies were excluded as they were not randomised trials. Five were excluded as the interventions were different from focus of this review. Three studies were excluded as they did not have any usable data. In the latter case we contacted authors requesting raw data, for most of these we have not yet received any replies.

2. Awaiting assessment No studies are awaiting assessment.

3. Ongoing studies We are not aware of any ongoing studies.

4. Included studies We identified 18 studies for inclusion, four of which are seen for the first time in this update (June2003). Two of these studies were awaiting assessment in previous versions of this review and two (Bechelli 1986, Chai 1998) we found in the latest update search. All included studies were randomised.

4.1 Length of trials Depot preparation has a slow absorption and long duration of action. Twelve of the included studies were of medium term duration (6‐12 months), two studies had a long‐term duration of more than a year, and three had short term durations of between six weeks to five months. One study lasting 22 days (Bechelli 1986) looked at immediate effects.

4.2 Participants All participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Only six studies included participants with operationalised diagnoses by RDC, ICD9 or DSM II. Most of the studies included people of both sexes although two studies (Albert 1980, Bechelli 1985) used all male participants. Two studies (Schlosberg 1978, Schneider 1981) failed to mention the sex of participants. Ages ranged between 18 and 75 years and the majority had a long history of illness.

4.3 Setting Several studies (Dencker 1973, Dencker 1978, Simon 1978) used participants from both hospital and community settings and four failed to mention the setting used (Albert 1980, Schlosberg 1978, Schneider 1981, Steinert 1986). Five studies Bechelli 1985, Chouinard 1978, Robak 1973, Singh 1979 and Woggon 1977 were conducted in the community and six studies Bechelli 1986, Chai 1998, Jain 1975, Robak 1973, Vereecken 1972Yan‐hua 1993 took place in a hospital setting.

4.4 Study size Chai 1998 was the largest study (209 participants) while Vereecken 1972 randomised only 26 people. Nine trials had fewer than 50 participants, six had 50 to 100participants and three included more than 100 people.

4.5 Interventions The dose of pipotiazine administered ranged widely from 25 mg/IM monthly to 250 mg IM twice weekly. Three trials compared pipotiazine palmitate with oral antipsychotics (Robak 1973, Simon 1978, Bechelli 1986). Fourteen studies compared pipotiazine palmitate to another depot, and one used the pipotiazine undecylenate ester as an intervention (Vereecken 1972).

4.6 Outcomes Many of the trials presented their findings in graphs or by p‐values alone. Graphical presentation made it impossible to acquire raw data for synthesis. Requests for raw data from authors have so far failed. It was also common to use p‐values as a measure of association between intervention and outcomes instead of showing the strength of the association.

4.6.1 Outcome scales The scales listed below were commonly used to measure outcomes:

4.6.1.1 Global state scales 4.6.1.1.1 Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) The CGI is a three‐item scale commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. The items are: severity of illness; global improvement and efficacy index. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery

4.6.1.2 Mental state scales 4.6.1.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The BPRS is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has sixteen items, but a revised eighteen‐item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0‐126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

4.6.1.2.2 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1983) This scale allows a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia (impoverished thinking), affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attention impairment. Assessments are made on a six‐point scale (0=not at all to 5=severe). Higher scores indicate a greater degree of symptoms.

4.6.1.2.3 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms ‐ SAPS (Andreasen 1983) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

4.6.1.2.4 The Hamilton rating scale for depression ‐ HRSD (Hamilton 1960) This instrument is designed to be used only on those patients already diagnosed as suffering from affective disorder of a depressive type. It is used for quantifying the results of an interview, and its value depends entirely on the skill of the interviewer in eliciting the necessary information. The scale contains 17 variables measured on either a five‐point or a three‐point rating scale, the latter being used where quantification of the variable is either difficult or impossible. Among the variables are: depressed mood, suicide, work and loss of interest, retardation, agitation, gastro‐intestinal symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, loss of insight, and loss of weight. It is useful to have two raters independently scoring a patient at the same interview. The scores of the patient are obtained by summing the scores of the two physicians. A score of 11 is generally regarded as indicative of a diagnosis of depression.

4.6.1.3 Behavioural rating scales 4.6.1.3.1 Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honigfeld 1965) This is an 80‐item scale with items rated on a five‐point scale from zero (not present) to four (always present). Ratings are based on the participants behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are social competence, social interest, personal neatness, cooperation, irritability, manifest psychosis and psychotic depression. The total score ranges from 0‐320 with high scores indicating a poor outcome.

4.6.1.4 Adverse effects scales 4.6.1.4.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Side Effects Scale ‐ AIMS (Guy 1976) The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale has been used to assess abnormal involuntary movements associated with antipsychotic drugs, such as tardive dyskinesia and chronic akathisia, as well as 'spontaneous' motor disturbance related to the illness itself. Tardive dyskinesia is a long‐term, drug‐induced movement disorder. However, using this scale in short‐term trials may also be helpful to assess some rapidly occurring abnormal movement disorders such as tremor. Scoring consists of rating movement severity in the anatomical areas (facial/oral, extremities, and trunk) on a five point scale (0=none, 4=severe).

4.6.1.4.2 Bordeleau Scale (Bordeleau 1967) This is a rating scale for extrapyramidal symptoms. We are currently seeking a fuller description of this scale.

4.6.1.4.3 Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale ‐ ESRS/EPS (Chouinard 1980) This consists of a questionnaire relating to parkinsonian symptoms (nine items), a physician's examination for parkinsonism and dyskinetic movements (eight items), and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. Each item is rated on a seven point scale. High scores indicate severe levels of movement disorder.

4.6.1.4.4 Simpson Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) The SAS is a 10‐item scale used to evaluate the presence and severity of drug‐induced parkinsonian symptomatology. The ten items focus on rigidity rather than bradykinesia, and do not assess subjective rigidity or slowness. Items are rated for severity on a 0‐4 scale, with a scoring system of 0‐4 for each item. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism.

4.6.1.4.5 Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale/Form (TESS/F) (Guy 1976). This checklist assesses a variety of characteristics for each adverse event, including severity, relationship to the drug, temporal characteristics (timing after a dose, duration and pattern during the day), contributing factors, course, and action taken to counteract the effect. Symptoms can be listed a priori or can be recorded as observed by the investigator.

4.6.1.5 Missing outcomes. None of the studies evaluated hospital/service outcomes, satisfaction with care and economic outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation No study specified the process of random allocation. Bechelli 1985 did state that allocation was stratified by schizophrenia subgroups. As poor reporting of randomisation has consistently been associated with an overestimate of effect (Schulz 1994) all allocation concealment has been rated as 'unclear' or quality 'B'. The results in these trials are likely to be a 30‐40% overestimate of effect (Schulz 1994, Moher 1998).

2. Blindness All but four studies were described as 'double blind': Leong 1989 described the trial as being partially blinded, Simon 1978 and Chai 1998 described the trial as open, Robak 1973 failed to mention if conditions were double blind or not. Of those authors who stated a double blind procedure was undertaken, none reported this being tested. Two questions, one to the participant ‐ "what do you think you have been given?" and one to the rater ‐ "what drug do you think this person was allocated?" would have clarified the situation. Failure to test double blinding may cast doubt on the quality of trial data. Scale data, as was often measured in the included studies, may be prone to bias when unblinding has taken place.

3. Loss to follow‐up Two studies had high drop rates. Dencker 1978 lost 46% of people by one year (63% of the pipotiazine group). Reasons for withdrawal were well described (side effects, shifts to other medications, moving to another place and refused to continue medication). Schneider 1981 reported 42% loss at one year on. No reasons for withdrawal were given. Apart from the outcome of 'leaving the study early' data from these trials were not entered into the analysis.

Effects of interventions

COMPARISON 1. PIPOTIAZINE PALMITATE versus TYPICAL ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS

1. Mental state No difference between those on depot medication and those allocated oral antipsychotics was found for the outcome of relapse at 18 months (n=124, 1 RCT, RR 1.55 CI 0.8 to 3.2). Rating scale scores of mental state (BPRS) at 18 months supported this finding (WMD ‐2.36 CI ‐7.2 to 2.4). BPRS data for the immediate term 22 days was also equivocal.

2. Leaving the study early Almost 20% of people taking pipotiazine left the study early (22/112) compared to 14% on the control group, but there were no apparent differences between the groups (n=219, 3 RCTs, RR 1.37 CI 0.77 to 2.44).

3. Behaviour Simon 1978 reported behaviour rating scale scores (NOSIE) at 18 months. Ratings were similar for people allocated pipotiazine decanoate and those given oral antipsychotic (n=124, WMD 4.65 CI ‐1.1 to 10.4).

4. Global impression: No important clinical response In Bechelli 1986 eight out of 27 people in the group allocated to pipotiazine showed no change while three out of 26 in the control group showed no change (n=53, RR 2.57 CI 0.8 to 8.6).

5. Adverse effects The number of people needing anticholinergic drugs for unspecified reasons was no different between those taking the depot and those allocated to standard antipsychotic drugs . The incidence of tardive dyskinesia was comparable between groups at the end of 18 months. The extrapyramidal adverse effects of dystonia, stiff gate and tremor were similar for pipotiazine and oral antipsychotics.

COMPARISON 2. PIPOTIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT PREPARATIONS

1. Global impression One study (Leong 1989, n=60) reported the rate of 'severe illness' (the majority in both groups) and found no difference between pipotiazine palmitate and fluphenazine decanoate (RR 0.97, CI 0.86 to 1.08). Four studies reported on 'no important global change' and again no significant difference was seen between pipotiazine palmitate and fluphenazine decanoate (n=217, RR 0.99 CI 0.9 to 1.1). Three studies (Albert 1980, Bechelli 1985, Chouinard 1978) reported that fewer people (p=0.06) in the other depot group required additional antipsychotics (RR 1.91 CI 0.97 to 3.8) compared to those in the pipotiazine palmitate group. Global impression scores were found to significantly favour pipotiazine palmitate when compared to fluphenazine decanoate in Schlosberg 1978 and Chai 1998 (n=220, WMD ‐0.35 CI ‐0.6 to ‐0.1). When severity of illness was compared at the end of the study by Chai 1998 it was found to be significantly reduced in the pipotiazine group (n=209, WMD ‐0.50, CI ‐0.8 to ‐0.2).

2. Mental state Seven studies found no differences in relapse rates between those allocated pipotiazine palmitate and those on other depots (n=417, RR 0.97 Cl 0.7 to 1.4). Dichotomised BPRS scores from Dencker 1973 also reported no difference between the groups (n=67, RR 1.09 CI 0.7 to 1.7) at a cut‐off of 'severely ill'. This was supported by summated BPRS endpoint scores from three trials (n=368, WMD ‐1.41 CI ‐2.9 to 0.1). Mental state scores of depression showed no difference (n=97, RR 0.89 CI 0.7 to 1.1). In this update dichotomised BPRS reported by Yan‐hua 1993 was equivocal (n=102, RR 1.18, CI 0.8 to 1.8). Chai 1998 assessed symptoms using SANS and SAPS and reported a significant reduction in symptoms for the pipotiazine group, but data were skewed and are not reported graphically.

3. Leaving the study early Eleven studies found no significant difference between those randomised to pipotiazine palmitate or the other depot group (n=608, RR 1.38 CI 1.0 to 1.8) but these were heterogeneous data (Chi square 18.36, df=10).

4. Adverse effects No differences between depots were reported for 'general' adverse effects (n=157, RR 0.80 CI 0.6 to 1.0). The prevalence of movement disorders was similar between groups, as was that of parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia and tremor. Six studies reported no significant difference in the number of people requiring anticholinergic medication, but the reasons for its use was unspecified. Blurred vision and dry mouth was equally present in both groups. Chai 1998 assessed adverse effects using the SAS and TESS scales and found low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects in the pipotiazine group, but data were skewed and are not reported graphically.

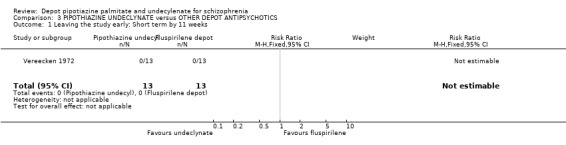

COMPARISON 3. PIPOTIAZINE UNDECYLENATE versus FLUSPIRILENE( Vereecken 1972)

There was only one study comparing pipotiazine undecylenate with other antipsychotics. There were no data on global impression, mental state or behavioural outcomes in this small short study (n=26, duration 11 weeks).

1. Leaving the study early No people left the study from either group by the 11 weeks.

2. Adverse effects The study found no differences in rates of movement disorders between pipotiazine undecylenate and fluspirilene (RR 1.00 CI 0.1 to 14.3). Parkinsonism was comparable between groups (RR 1.00 CI 0.1 to 14.3) and as was the rate of needing anticholinergic drugs (RR 1.67 CI 0.9 to 3.2).

3. Missing outcomes No study reported on hospital and service outcomes or commented on participants' overall satisfaction during or after the trial. No included trial reported economic outcomes.

Discussion

1. Applicability of results Diagnoses were based on varied criteria (DSM II, DSM III, French classification of mental illness, ICD‐9, RDC) but ten out of the 18 included trials did not specify which diagnostic criteria were used. The failure of studies to report the tool used to diagnose schizophrenia, and differences in criteria used, suggests that diagnoses could be heterogeneous. This heterogeneity should increase external validity of the findings of this review. Where a description was available (8/18 trials) participants had long histories of schizophrenia (duration of illness ranged from <1‐34 years) and most were in hospital. All trials evaluated doses of depot pipotiazine that would be used in the 'real world'.

Compliance is currently a major concern in modern‐day treatments of schizophrenia. Observing the effect of oral and depot antipsychotic drugs in terms of clinical efficacy, adverse effects and social implications has a wide role to play in constructing a sound basis for the choice the clinician makes when prescribing medication. The main benefit of depot formulations is that covert non‐compliance is eliminated and if relapse does occur under these circumstances then non‐compliance can be ruled out. Those entering clinical trials, however, are usually reasonably compliant people. This must always compromise the applicability of the results of trials of depot preparations to the real community, where non‐compliance or failure to turn up to depot clinics is commonplace.

2. COMPARISON 1. PIPOTIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS 2.1 All outcomes There was no difference between pipotiazine palmitate and 'standard antipsychotics' for any of the outcomes. These included measures of relapse, mental state (endpoint BPRS), leaving the study early, behaviour (endpoint NOSIE score) and adverse effects. Currently there is no trial‐based evidence that pipotiazine has any advantages, or drawbacks, when compared to oral drugs.

Bearing in mind the issues of generalisability discussed above, and the likely minimisation of covert non‐compliance associated with oral antipsychotic medication within trials, the use of a depot preparation in the 'real world' seems attractive. If by prescribing depots, covert non‐compliance would be resolved, and relapse and mental state treated as effectively as by oral medication, this is important. It needs to be ascertained however, whether the use of this depot would affect a person's performance in other areas of functioning, such as social behaviour, life skills or cognitive capacity to a greater or lesser extent than oral antipsychotics.

3. COMPARISON 2. PIPOTIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT PREPARATIONS Sixteen studies (n=1123, duration 12 weeks to three years) compared pipotiazine palmitate with other depots. In comparison to other depot preparations pipotiazine palmitate is well researched within trials.

3.1 Global impression Improvement was rare and no different for those allocated to pipotiazine palmitate or fluphenazine decanoate (the comparator in all three trials that provided data for this result). The participants in these studies were, for the most part, extremely ill, and it may be asking a great deal of any treatment to have much of an effect on those whose illnesses were so entrenched. Additional antipsychotics were required in the pipotiazine palmitate group more frequently than for those allocated other depots. This could suggest that the dosage of pipotiazine palmitate was too low in the three studies (Albert 1980, Bechelli 1985, Chouinard 1978, range 25 mg/IM/month ‐ 150 mg/IM/month). Two studies (Schlosberg 1978, Chai 1998) provide Clinical Global Impression endpoint scores favouring pipotiazine palmitate over fluphenazine decanoate. As with many continuous outcomes, it is difficult to interpret these data.

3.2 Mental state There was no difference in the number of people relapsing between pipotiazine palmitate and other depots (n=417, about 15% in both groups by one year). Dichotomous and continuous BPRS scores and depression scores also reported no difference between groups. These are the most convincing and consistent results in this review and suggest no difference between depot preparations. Chai 1998 showed reduction in scores for positive and negative symptoms using SANS and SAPS. The SD for these scores were high and so we did not include these in the final analysis.

3.3 Leaving the study early Twenty three percent of participants left the studies before completion (by about one year). There were no differences between groups. In this update two more studies were added (Woggon 1977 and Yan‐hua 1993). Adding these data did not result in any substantive changes.

3.4 Adverse effects Pipotiazine palmitate causes a range of adverse effects, but no more frequently than other depot preparations. At least one third of people given pipotiazine palmitate will develop movement disorders and approaching 60% will be prescribed anticholinergic medication. Again, these findings are largely based on a greater total number of trial participants than has been seen in other depot reviews. Chai 1998 used the TESS and SAS scales to look at side effects. Though they showed a better outcome for the pipotiazine group, the data were skewed and therefore not included in the final analysis.

4. COMPARISON 3. PIPOTIAZINE UNDECYLENATE versus FLUSPIRILENE Vereecken 1972 (n=26, duration 11 weeks) compared this pipotiazine ester with fluspirilene.

4.1 All outcomes Vereecken 1972 was an unusual trial in that no data for global impression or mental state were reported. No one left the study before completion. There were no discernible differences in adverse effects of movement disorders, parkinsonism or in the requirement for anticholinergic medication. All findings are based on very small numbers.

According to an industry‐based register of antipsychotic drugs (http://www.psychiatrylink.com/PsychotropicsDatabase/default.htm) accessed in May 1999, the undecylenate depot ester of pipotiazine is no longer used in clinical practice.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For clinicians Currently, considerable trial‐based data suggests that pipotiazine palmitate is neither better nor worse than other depot preparations. These data should assist the process of deciding which depot to give and personal preference, clinical judgement and accessibility must also play a major part. These trials do not inform clinicians if pipotiazine palmitate has advantages or drawbacks over oral antipsychotics.

2. For people with schizophrenia Pipotiazine palmitate is a well‐researched depot. No convincing differences are evident when comparing the pipotiazine esters with oral antipsychotic drugs or with other depot formulations. There are no discernible differences, illustrated within clinical trials, between the different depots in terms of clinical improvement, acceptability of treatment, or severity of adverse effects. This does not mean that real differences do not exist but the numbers in the pipotiazine palmitate versus other depot comparisons were reasonably large. Currently choices to receive depot or not could be based on personal preference as could the decision regarding which depot to take.

3. For managers or policy makers No direct data on hospital and services outcomes, satisfaction with care and economics were available. If depot formulations do promote compliance and this leads to a reduction in relapses, this would have important implications for patients and the services that care for them. Any suggestion that pipotiazine palmitate reduces relapse and hospital care is not based on trial data.

Implications for research.

1. General If the recommendations of the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001) had been anticipated by trialists much more data would have been available. Allocation concealment is essential for the result of a trial to be considered valid and gives the assurance that selection bias is kept to the minimum. Well‐described and tested blinding could have encouraged confidence in the control of performance and detection bias. It is also important to know how many, and from which groups, people were withdrawn, in order to evaluate exclusion bias. It would have been helpful if authors had presented data in a useful manner which reflected association between intervention and outcome, for example, relative risk, odds‐ratio, risk or mean differences, as well as raw numbers. Binary outcomes should be calculated in preference to continuous results, as they are easier to interpret. If p‐values are used, the exact value should be reported.

2. Specific In comparison to other depot antipsychotics, the effects of pipotiazine palmitate have been well investigated within trials. Nevertheless, there are no data on service use, social and cognitive functioning, satisfaction with care and economics. Depending on the prevalence of use ‐ and this information has, at the time of writing, been impossible to find ‐ more trials are needed to finally, fully evaluate this potent drug preparation. Well‐planned, conducted and reported 'real world' clinical trials (Simon 1995) would overcome some of the problems of applicability of the data presented in this review.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Review first published: Issue 3, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Clive Adams, Leanne Roberts and Tessa Grant for their help and support. We would also like to thank Dr Cookson, Dr McCreadie and Dr Zuardi for their assistance.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global impression: No important clinical response ‐ immediate by 3 weeks | 1 | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.57 [0.76, 8.63] |

| 2 Mental state: 1. Relapse ‐ longer term by 18 months | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.55 [0.76, 3.18] |

| 3 Mental state: 2. BPRS ‐ immediate by 22 days (endpoint, high score=poor) | 1 | 53 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [‐3.56, 5.76] |

| 4 Mental state: 3. BPRS ‐ longer term by 18 months (endpoint, high score=poor) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.36 [‐7.14, 2.42] |

| 5 Leaving the study early | 3 | 219 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.77, 2.44] |

| 5.1 immediate (up to 5 weeks) | 1 | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.85 [0.46, 32.22] |

| 5.2 medium term (6 months to 1 year) | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.0 [0.38, 128.61] |

| 5.3 longer term (more than 1 year) | 1 | 118 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.53, 1.88] |

| 6 Behaviour: NOSIE‐30 ‐ longer term by 18 months (endpoint, high score=poor) | 1 | 124 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.65 [‐1.13, 10.43] |

| 7 Adverse effects: 1. Movement disorders | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 needing anticholinergic drugs ‐ reason unspecified | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.71, 1.10] |

| 7.2 tardive dyskinesia | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.22, 4.92] |

| 8 Adverse effects: 2. Extrapyramidal adverse effects | 1 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.52, 1.61] |

| 8.1 dystonia | 1 | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.04, 2.89] |

| 8.2 stiff gate | 1 | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.52, 3.19] |

| 8.3 tremor | 1 | 53 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.39, 1.88] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Global impression: No important clinical response ‐ immediate by 3 weeks.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Mental state: 1. Relapse ‐ longer term by 18 months.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Mental state: 2. BPRS ‐ immediate by 22 days (endpoint, high score=poor).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Mental state: 3. BPRS ‐ longer term by 18 months (endpoint, high score=poor).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Leaving the study early.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 6 Behaviour: NOSIE‐30 ‐ longer term by 18 months (endpoint, high score=poor).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 7 Adverse effects: 1. Movement disorders.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus ORAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 8 Adverse effects: 2. Extrapyramidal adverse effects.

Comparison 2. PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global impression: 1. CGI ‐ Severity of illness ‐ longer term by 28 weeks | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.86, 1.08] |

| 2 Global impression: 2. CGI ‐ Not improved | 4 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.91, 1.08] |

| 2.1 short term (6 weeks to 5 months) | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.47, 3.09] |

| 2.2 medium term (6 months to 1 year) | 2 | 127 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.89, 1.08] |

| 2.3 longer term (more than 1 year) | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.88, 1.06] |

| 3 Global impression: 3. Needing additional antipsychotic treatment ‐ medium term, 6 months to 1 year | 3 | 106 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.91 [0.97, 3.76] |

| 4 Global impression: 4. CGI ‐ Endpoint data (high score=poor) | 2 | 220 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.57, ‐0.12] |

| 4.1 short term by 6 weeks | 1 | 209 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐0.53, ‐0.07] |

| 4.2 longer term by 15 months | 1 | 11 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.39 [‐2.50, ‐0.28] |

| 5 Global impression: 5. CGI ‐ Severity of illness ‐ short term by 12 weeks | 1 | 209 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.5 [‐0.84, ‐0.16] |

| 6 Mental state: 1. Relapse | 7 | 417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.66, 1.41] |

| 6.1 medium term (6 months to 1 year) | 5 | 239 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.55, 1.75] |

| 6.2 longer term (more than 1 year) | 2 | 178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.58, 1.58] |

| 7 Mental state: 2. BPRS ‐ Severly ill ‐ medium term by 12 months | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.70, 1.70] |

| 8 Mental state: 3. BPRS ‐ No improvement ‐ medium term by 6 months | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.78, 1.77] |

| 9 Mental state: 4. BPRS (endpoint, high score=poor) | 3 | 368 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.41 [‐2.94, 0.12] |

| 9.1 short term by 6 weeks | 1 | 209 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.50 [‐3.75, 0.75] |

| 9.2 medium term by 6 months | 1 | 41 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.10 [‐3.43, 1.23] |

| 9.3 longer term by 18 months | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.31 [‐7.09, 2.47] |

| 10 Mental state: 5. Depression ‐ medium term 6 months to 1 year | 2 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.69, 1.13] |

| 11 Mental state: 6. SANS/SAPS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 11.1 negative symptoms (SANS, high=poor) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 11.2 positive symptoms (SAPS, high=poor) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12 Leaving the study early | 11 | 608 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [1.04, 1.83] |

| 12.1 short term (6 weeks to 5 months) | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.50, 31.74] |

| 12.2 medium term (6 months to 1 year) | 8 | 451 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.85, 1.76] |

| 12.3 longer term (more than 1 year) | 2 | 127 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.98, 2.47] |

| 13 Adverse effects: 1. General | 3 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.61, 1.04] |

| 14 Adverse effects: 2. Anticholinergic effects | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 blurred vision | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.58] |

| 14.2 dry mouth | 2 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.57, 2.75] |

| 14.3 needing anticholinergic drugs ‐ reason unspecified | 5 | 337 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.84, 1.15] |

| 15 Adverse effects: 3. Movement disorders | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 movement disorder | 6 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.71, 1.09] |

| 15.2 needing anticholinergic drugs ‐ reason unspecified | 6 | 370 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.85, 1.17] |

| 15.3 parkinsonism | 1 | 118 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.06, 14.59] |

| 15.4 tardive dyskinesia | 2 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.75, 2.81] |

| 15.5 tremor | 5 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.62, 1.15] |

| 16 Adverse effects: 4. SAS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 17 Adverse effects: 5. TESS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data) | Other data | No numeric data |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Global impression: 1. CGI ‐ Severity of illness ‐ longer term by 28 weeks.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Global impression: 2. CGI ‐ Not improved.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Global impression: 3. Needing additional antipsychotic treatment ‐ medium term, 6 months to 1 year.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Global impression: 4. CGI ‐ Endpoint data (high score=poor).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Global impression: 5. CGI ‐ Severity of illness ‐ short term by 12 weeks.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 6 Mental state: 1. Relapse.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 7 Mental state: 2. BPRS ‐ Severly ill ‐ medium term by 12 months.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 8 Mental state: 3. BPRS ‐ No improvement ‐ medium term by 6 months.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 9 Mental state: 4. BPRS (endpoint, high score=poor).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 10 Mental state: 5. Depression ‐ medium term 6 months to 1 year.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 11 Mental state: 6. SANS/SAPS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (skewed data).

| Mental state: 6. SANS/SAPS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| negative symptoms (SANS, high=poor) | ||||

| Chai 1998 | Pipotiazine | 20.10 | 23.10 | 103 |

| Chai 1998 | Control | 29.60 | 18.90 | 106 |

| positive symptoms (SAPS, high=poor) | ||||

| Chai 1998 | Pipotiazine | 9.40 | 14.70 | |

| Chai 1998 | Control | 13.60 | 12.40 | |

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 12 Leaving the study early.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 13 Adverse effects: 1. General.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 14 Adverse effects: 2. Anticholinergic effects.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 15 Adverse effects: 3. Movement disorders.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 16 Adverse effects: 4. SAS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data).

| Adverse effects: 4. SAS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N | Notes |

| Chai 1998 | Pipotiazine | 1.00 | 2.10 | 103 | |

| Chai 1998 | Control | 5.10 | 5.60 | 106 | |

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 PIPOTHIAZINE PALMITATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 17 Adverse effects: 5. TESS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data).

| Adverse effects: 5. TESS ‐ short term by 12 weeks (high score=poor, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| Chai 1998 | Pipotiazine | 2.60 | 3.90 | 103 |

| Chai 1998 | Control | 7.80 | 7.20 | 106 |

Comparison 3. PIPOTHIAZINE UNDECLYNATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early: Short term by 11 weeks | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Adverse effects: Movement disorders | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 movement disorders | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.34] |

| 2.2 needing anticholinergic drugs ‐ reason unspecified | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.86, 3.22] |

| 2.3 parkinsonism | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.34] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 PIPOTHIAZINE UNDECLYNATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early: Short term by 11 weeks.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 PIPOTHIAZINE UNDECLYNATE versus OTHER DEPOT ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Adverse effects: Movement disorders.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Albert 1980.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 39 weeks (drug stabilization period, 2 months ‐ 3 treatment groups). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: chronic illness, average length of hospitalisation 16‐21 years. N=33. Age: "mid 40s". Sex: all male. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 100 mg/IM/month. N=11. 2. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 150 mg/IM/month. N=11. 3. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose 50 mg/IM/biweekly. N=11. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects. Unable to use ‐ Global impression: CGI (no SD). Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Adverse effects: NOSIE (no SD). |

|

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bechelli 1985.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, stratified by schizophrenia subgroups. Blindness: double. Duration: 6months (preceeded by 7 day washout). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (RDC). History: >2 episodes, stabilized for 3 months, duration ill ‐ mean 12 years (SD 9 years), informed consent. N=41. Age: range 19‐50 years, mean range 30‐33. Sex: all male. Setting: out‐patient clinic. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 75mg/IM/month**, range 50‐125 mg/injection. N=20. 2. Haloperidol decanoate: dose mean 100mg/IM/month, range 50‐100 mg/injection. N=21. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS.

Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects: AIMS, Bordeleau Scale. Unable to use ‐ Global impression: CGI (no data). Weight measures: non‐clinical outcomes (data not usable). |

|

| Notes | * Spitzer 1997 ** Mean dose of PP reported as 75 mg in the abstract and 65mg in paper. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bechelli 1986.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, stratified by schizophrenia subgroups. Blindness: double. Duration: 22 days. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (ICD 9). History: all previously had two or more episodes/admissions to hospital and were admitted with acute episode, duration ˜50 days. N=53. Age: 20‐29 years, mean age 30.1+/‐ 7.2 years. Sex: all male. Setting hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1 . Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 100 mg/IM (once). N=27. 2. Haloperidol decanoate: dose 20 mg/IM/ (one dose) and drops of haloperidol 20 mg/day for 22 days. N=26. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS. Global state: CGI. Leaving the study early. Adverse effects. EPS. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chai 1998.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: open. Duration: 12 weeks preceded by a one week washout period. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: length of illness 1‐10 years. N=209. Age: mean 30 years. Sex: 127M, 82F. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 50‐150 mg/4 weeks. N=103. 2. Haloperidol decanoate: dose 50‐150 mg/4 weeks. N=57. 3. Fluphenzine decanoate: dose 25‐75 mg/2 weeks. N=49. | |

| Outcomes | Global impression: CGI. Mental state: BPRS, SANS, SAPS. Adverse effects: TESS, SAS. | |

| Notes | Skewed data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chouinard 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 9 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: informed consent given. N=32. Age: 20‐60 years. Sex: 16M, 16F. Setting: community. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose range 25‐100 mg/IM/month. N=16.

2. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose range 6.25‐100 mg/IM/biweekly. N=16. Dose adjusted to therapeutic response. |

|

| Outcomes | Global impression: CGI.

Mental state: BPRS.

Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects: HRSD, EPS, TESE. Unable to use ‐ Adverse effects (no SD). Physiological measures (non‐clinical outcomes, data not usable). |

|

| Notes | Statistics: last observation carried forward. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dencker 1973.

| Methods | Allocations: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 1 year (3 phases: adjustment ‐ 3 months, 1st maintenance ‐ 3 months, 2nd maintenance ‐ 6 months). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: duration ill >5years. N=67. Age: mean 41 years, range 18‐65. Sex: 51M, 14F. Setting: community & hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 50 mg/IM/month, range 25‐400 mg/IM. N=31. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean 6.25 mg/IM/month, range 3.1‐50 mg/IM. N=34. | |

| Outcomes | Global rating.

Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects: EPS, TESE.

Depression: HRSD. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Cognitive function: handwriting test (no usable data). Work capacity: ADL, SRE (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dencker 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 3 years. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: not reported. N=36. Age: mean 41 years. Sex: 29M, 7F. Setting: hospitalised (1 year), community (2 years). | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 152.3 mg/IM/month. N=33. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean 27.8 mg/IM/month. N=34. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Additional medication. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no data). Adverse effects: HRSD, EPS (no data). Work capacity: ADL (data not usable). |

|

| Notes | 63% attrition is reported in the treatment group. Only data used is leaving the study early. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jain 1975.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 20 weeks (preceeded by 2 week washout period). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: hospitalized for <1year. N=30. Age: mean 49 years, range 24‐61. Sex: 14F, 16M. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 250 mg/IM/biweekly. N=15. 2. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose mean 125 mg/IM/biweekly. N=15. | |

| Outcomes | Global impression: CGI.

Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no data). Adverse effects: TESS (no data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Leong 1989.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: partial. Duration: 28 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (ICD‐295). History: informed consent given. N=60. Age: mean 38 years, range 18‐65. Sex: 27M, 33F. Setting: community. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose range 25‐50 mg/IM/frequency not reported. N=30. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 12.5‐50 mg/IM/frequency not reported. N=30. | |

| Outcomes | Global Impression: CGI.

Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects: checklist, EPS. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Robak 1973.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: open. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: duration ill ˜ 25 years. N=48. Age: <20‐69 years. Sex: 17F, 31M. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 113.4 mg/IM/month. N=24. 2. Control group (different oral antipsychotics) no further details. N=24. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no data). Behaviour: NOSIE (no data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Schlosberg 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 12 months (9 months depot, 3 months placebo, preceeded by 2 week wash‐out period). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: duration ill mean 17 years, 'highly resistant to treatment'. N=75, 12 in placebo trial. Age: mean 42 years. Sex: not reported. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose range 6.25‐50 mg/IM/month. N=30. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 6.25‐50 mg/IM/month. N=30. | |

| Outcomes | Global impression.

Leaving the study.

Adverse effects. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no SD). Behaviour: NOSIE (no SD). Social functioning (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Schneider 1981.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 1 year (preceeded by 2 week wash‐out). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II). History: duration ill mean 21 years, informed consent. N=59. Age: mean 45 years, range 21‐65. Sex: 51M, 8F. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose range 50‐40 mg/IM/2‐5 weeks. N=32. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 12.5‐100 mg/IM/2‐5 weeks. N=27. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Global impression: CGI (no data). Blood samples: (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | 67% attrition occured in the control group by the end of 1year, therefore data could not be used. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Simon 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: open. Duration: 18 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (French classification system). History: duration ill <3years, range 3‐10 years. N=181. Age: 21‐45 years. Sex: 117M, 64F. Setting: community/hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 90 mg/IM/25 days. N=61. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose mean 88 mg/IM/22 days. N=57. 3. Standard oral neuroleptics: dose (no further details). N=63. | |

| Outcomes | Global impression: CGI. Mental state: BPRS. Behaviour: NOSIE. Leaving the study early. Additional medication. Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Singh 1979.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 44 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐II). History: duration ill mean 4 years, range 3‐32. N=30. Age: mean 44 years, range 29‐59. Sex: 24M, 6F. Setting: community. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 125 mg/IM/month, range 100‐15 mg/IM. N=15. 2. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose mean 44.2 mg/IM/month, range 25‐75 mg/IM. N=15. | |

| Outcomes | Adverse effects. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no usuable data). Laboratory tests (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Steinert 1986.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 12 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: informed consent. N=39. Age: mean 42.5 years. Sex: 24M, 15F. Setting: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose mean 100 mg/IM/month. N=23. 2. Flupenthixol decanoate: dose mean 40 mg/IM/biweekly. N=16. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS.

Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: CPRS, ZDS (no data). Adverse effects: EPS, General SE's Scale (no data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Vereecken 1972.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 11 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II). History: duration ill mean 34 years, all on depot prior to trial. N=26. Age: range 25‐75 years, mean 61. Sex: all female. Setting: hospitalised. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine undecylenate: dose mean 103.8 mg/IM/biweekly. N=13. 2. Fluspirilene: dose mean 9.46 mg/IM/week. N=13. Doses individually tailored. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early.

Additional medication.

Adverse effects. Unable to use ‐ Occupational therapy (data not usuable). Blood samples (data not usable). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Woggon 1977.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: double. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagosis: schizophrenia (ICD). History: chronic illness. N=61. Age: 21‐79. Sex: 36M, 25F. Setting: community. | |

| Interventions | Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 100 mg/IM/4 weekly. N=31. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose 25‐37.5 mg/IM/3 weekly. N=30. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: AMP (no mean or SD). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Yan‐hua 1993.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blindness: one group of pipothiazine and fluphenazine double blinded and one pipothiazine group non‐blinded. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: chronic illness. N=152. Age: range 26‐47 years. Sex: 79M, 60F. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Pipothiazine palmitate: dose 50 mg/IM/2 weekly. N=102. 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose 25 mg/IM/2 weekly. N=50. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS. Leaving study early. Adverse effects: TESS. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Diagnostic tools: DSM ‐ Diagnostic Statistical Manual. ICD‐9 ‐ International Classification of Diseases, version 9. RDC ‐ Research Diagnostic Criteria.

Rating scales Global impression: CGI ‐ Clinical Global Impression.

Behaviour: NOSIE ‐ Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation.

Mental state: AMP ‐ No details available ‐ published, German language scale. BPRS ‐ Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. CPRS ‐ Comprehensive Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Side effects: AIMS ‐ Abnormal Involuntary Movement Side effects. DOTES ‐ Dosage Record & Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale. EPMS ‐ Extrapyramidal Motor Side‐effects. EPS ‐ Extrapyramidal Symptoms. HRSD ‐ Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. MARDRS‐ Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale. SAS ‐ Simpson and Angus Scale. STESS ‐ Total Score of Side Effects Self Rating. TESS/F ‐ Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale/Form. TESE ‐ Treatment Emergent Side Effects. UKU ‐ Side Effects Rating Scale. ZDS ‐ Zung's depression Scale.

Work capacity: ADL ‐ Activities of Daily Living. SRE ‐ Schedule of Recent Events.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ahlfors 1973 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: fluphenazine enanthate versus pipotiazine undecylenate. Outcomes: no usable data, authors contacted. |

| Angst 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Aref 1980 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Arrojo 1978 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Astrup 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Balon 1982 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Bechelli 1983 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: oral pipothiazine, not depot. |

| Deberdt 1971 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Demerdash 1981 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Dencker 1980a | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Dom 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Faltus 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Floru 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Gallant 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Itil 1978 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Kistrup 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Kistrup 1991 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Knudsen 1985 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Knudsen 1985b | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Lapierre 1983 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: pipothiazine palmitate versus fluphenazine decanoate. Outcomes: no usable data. |

| Lopez1971 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Masiak 1976 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Matkowski 1979 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Pietzcker 1993 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: not given. |

| Rojo 1971 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Ropert 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Rysanek 1982 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Salvesen 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Tanghe 1972 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Tunninger 1994 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Vranckx‐Haenen 1979 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Zonda 1992 | Allocation: not randomised. |

Contributions of authors