Abstract

Objectives

Current studies in cardiothoracic clinical research frequently fail to use endpoints that are most meaningful to patients, including measures associated with quality of life. Patient- reported outcomes (PRO) represent an underutilized but important component of high quality patient-centered care. Our objective was to highlight important principles of PRO measurement, describe current use in cardiothoracic surgery, and discuss the potential for and challenges associated with integration of PROs into large clinical databases.

Methods

We performed a literature review using the PubMed/EMBASE databases. Clinical articles that focused on the use of PROs in cardiothoracic surgery outcomes measurement or clinical research were included in this review.

Results

PROs measure the outcomes that matter most to patients and facilitate the delivery of patient-centered care. When effectively used, PRO measures have provided detailed and nuanced quality of life data for comparative effectiveness research. However, further steps are needed to better integrate PRO into routine clinical care.

Conclusions

Incorporation of PRO into routine clinical practice is essential for delivering high quality patient-centered care. Future integration of PRO into prospectively collected registries and databases, including that the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database, has the potential to enrich comparative effectiveness research in cardiothoracic surgery.

Keywords: Outcomes, Postoperative Care, Quality of Life

Introduction

Much of the existing clinical outcomes research in cardiothoracic surgery has focused on objective endpoints, including perioperative morbidity, and short and long-term survival [1, 2]. While these measures are important and influence treatment decisions, they often do not fully encompass outcomes that are meaningful to patients. As patient-centered care is coming to the forefront of high value healthcare delivery, incorporation of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) into clinical practice and research is critical. PROs are measures of patient physical, mental and emotional well being obtained by patient self-report. This review will detail important concepts of PROs, discuss the rationale for use, provide current examples of PRO measures in the cardiothoracic surgical literature, and highlight key issues regarding its implementation and incorporation into the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database (STS ND).

Methods

We aimed to review all studies that provided high quality examples of applications of HRQoL instruments in cardiothoracic surgery. We performed a review of relevant studies using PubMed and EMBASE databases. Our search strategy involved a combination of the following (MESH) terms: “patient-reported outcomes,” “cardiac surgery,” “thoracic surgery,” and “esophagectomy.” Abstracts were first reviewed for general pertinence to HRQoL measures and PRO in cardiothoracic surgical research. Once an abstract was determined to be relevant, the article was reviewed in full. We performed an additional literature search by reviewing the reference lists of articles. Our search process concluded in April 2018.

PROs, Patient-Centered Care, and Comparative Effectiveness Research

PROs are integral to patient-centered healthcare delivery. Outcomes that are meaningful to patients extend beyond traditionally reported measures of survival and morbidity [3]. These often include determinants of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [1, 4]. While commonly measured outcomes including long-term survival and perioperative complications are important to patients, they often provide an incomplete picture of what patients value, and undermine the decision making power they have regarding their care. For example, when choosing two treatment options for lung cancer, a patient may value post-treatment functional status, pain quality, and time off from work as important aspects for consideration along with traditional measures [5].

PRO measures are reported directly by patients and are an important way for obtaining accurate data on patient HRQoL. Many of the traditional instruments used for assessing patient HRQoL, especially in the postoperative period, have relied on clinician-based assessments. Clinician-based assessments have been shown to deviate widely from the actual patient perspective [6, 7]. PRO measures thus offer several advantages, as they provide a more reliable means for the longitudinal evaluation of patients. Additionally, they can allow for more complete comparative effectiveness research [1, 8].

There have been several barriers to the routine collection and evaluation of HRQoL in cardiothoracic research [9]. The subjectivity associated with HRQoL has caused concern regarding the validity of HRQoL studies. In part, this is due to the significant variability in HRQoL instruments. Additionally, there has been a perceived lack of sensitivity and flexibility in PRO instruments to detect more minor changes in symptoms. Another barrier to routine use of HRQoL is the increased work required to successfully implement HRQoL data collection. HRQoL instruments are survey-based, making data collection and analysis potentially labor intensive and time-consuming, especially when compared to endpoints that are already available from databases or medical records [7].

There is a need for the routine collection of PRO data to improve clinical care. PRO measures can give us a more accurate picture of patients’ clinical status, allowing for early intervention. For example, studies have shown that changes in QOL scores are independent predictors of survival in patients with lung cancer [10]. In addition to better informing clinicians on the postoperative course of their patients, PRO measures can provide cardiothoracic surgeons with quality information to help patients make treatment-related decisions. Many surgeons rely on anecdotal knowledge to provide patients with information on postoperative HRQoL, and are unable to effectively offer data-driven advice regarding differences in QOL between treatments that directly reflect a patient’s experience [11]. As such, PRO measures are increasingly viewed as the optimal measurement for quality and accuracy in patient-centered care.

Additionally, there has been a greater national recognition for the integration of PROs into outcomes measurement and comparative effectiveness research (CER). Several national organizations, including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), National Quality Forum, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) advocate for integration of PRO into the measurement of patient outcomes and assessments of clinical performance [12]. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) has included PRO measures as part of their guidelines for lung cancer care, recommending the routine use of HRQoL instruments in clinical care [13]. For the evaluation of new devices and drug therapies, the FDA has recommended that PRO measures be incorporated into primary and secondary study outcomes [14]. The Center for Medical Technology Policy has advocated for the use of PRO in all prospective, adult oncology CER studies [1]. With the Affordable Care Act, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) was created to promote high-quality CER, and has provided nearly $2 billion of funding thus far [15]. PCORI’s main mission is to improve healthcare delivery and outcomes through the promotion of high-integrity, evidence-based information that is derived from all stakeholders involved. Thus, capturing patients’ voices through the routine use of PRO is an integral component of PCORI’s mission.

It is critical for future studies engaged in CER to incorporate PRO measures. Broadly speaking, there is still a great need for PRO in clinical practice and cardiothoracic research. In a survey of the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS), 54.4% all surgeons surveyed did not incorporate PRO into their clinical practice [11]. We review some examples of how PRO were implemented in the design of cardiothoracic surgery comparative effectiveness research.

Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cardiothoracic Surgery

There are several studies within the cardiothoracic surgical literature that have investigated PROs and HRQoL. Many instruments have been used to collect these data as illustrated in Table 1. As the importance of PROs is increasingly recognized, these assessments have been more heavily utilized [2, 5, 16, 17]. This is particularly true in cardiac surgery where a number of recent major prospective trials have included HRQoL measures as primary and secondary endpoints in CER. This is in contrast to the general thoracic surgery literature, where oncologic outcomes such as 5-year survival and recurrence predominate. Even in the cardiac surgery literature, the traditional endpoints in most studies have focused on major adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. For example, in one review of 34 randomized clinical trials in cardiac surgery, the majority of studies did not include any assessment of PROs [18].

Table 1:

Select Commonly Used Quality of Life and Patient-Reported Outcomes instruments

| Generic Questionnaires: |

| • Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) |

| • Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) and Short Form 12 (SF-12) |

| • Rotterdam Symptom Checklist |

| • Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) |

| • Dyspnea Index |

| • Nottingham Health Profile |

| Thoracic Specific: |

| • European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Modules |

| • Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ C-30) |

| • QLQ Oesophagus Module (OES-18) |

| • QLQ Lung Cancer Module (LC13) |

| • Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Oncologic and Organ-Specific Modules |

| • Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Health Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (GERD-HRQL) |

| • Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index |

| Cardiac Specific: |

| • Seattle Angina Questionnaire |

| • Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| • Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire |

| • Cardiac Symptom Survey |

| • Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire, CROQ |

| • Duke Activity Status Index |

| • Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory, HSSI |

Several of the more recent major prospective studies in cardiac surgery have included HRQoL endpoints for evaluation of comparative efficacy. A few examples of larger, randomized prospective studies include the Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX), Surgical Replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI), and the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trials [19–21]. Each of these studies is an excellent example of the valuable information gained when HRQoL endpoints are included as endpoints within prospective studies. The SYNTAX investigators utilized the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, finding greater relief from patient-reported angina at 6 and 12 months in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass (CABG), when compared with PCI. However, patient-reported physical limitation was worse at 1 month in the CABG cohort [19]. The SURTAVI investigators utilized the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, finding significant improvement in HRQoL scores after both surgical and transcatheter valve replacement through 24 months. At one month, HRQoL scores were better in the transcatheter cohort with no difference identified thereafter [20]. Similar results were seen in the PARTNER and PARTNER II trials, utilizing the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy and Short-Form 12 questionnaires [21]. In a randomized, prospective comparison of mitral valve repair vs replacement, mitral replacement resulted in a non-significant trend towards greater improvement in HRQoL as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire [22]. Similar studies have included HRQoL endpoints in comparisons of robotic assisted and standard CABG [23], on- and off-pump coronary bypass [24, 25], tissue versus mechanical prostheses [26], cardiac surgery in the elderly [27, 28] and a variety of other cardiac surgery interventions [29].

A variety of both retrospective and prospective studies have similarly examined PRO and HRQoL results after surgery for thoracic malignancies [2, 10, 30–37]. A summary of select studies examining PRO after lung cancer surgery is shown in Table 2. These studies are relatively small, single center, observational studies. However, valuable information can still be gleaned from them. For example, several of these studies have compared non-operative vs. operative therapy, VATS vs. thoracotomy, and sublobar resection vs. lobectomy, among other important questions. Overall, these studies show an expected initial decline in physical function, dyspnea, and quality of life scores after surgery, with most studies showing a return to baseline within 6 months to a year.

Table 2:

Summary of select HRQoL studies in patients undergoing surgery for non-small cell lung cancer

| Author, Year | Instrument Used | n | Time Frame Analyzed | Aim of Study | Select Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al., 2002 [55] | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 | 51 | Range 6–84 months | Evaluate HRQoL comparing VATS versus thoracotomy. | No significant difference between the two groups in functioning and symptom scales. |

| Kenny et al., 2008 [51] | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 | 173 | Preoperative to 2 years | Evaluate HRQoL and survival in the 2 years after surgery | Half of patients continue to experience symptoms and functional limitations 2 years after surgery. Patients with recurrence of cancer reported continued deterioration of HRQoL, while most disease-free survivors experienced recovery. |

| Balduyck et al., 2008[56] | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13 | 30 | Preoperative to 1 year | Evaluate HRQoL after sleeve lobectomy and pneumonectomy | Patients reported less impact on physical functioning, role functioning, cognitive functioning, and shoulder dysfunction after sleeve lobectomy, compared with pneumonectomy. |

| Ferguson et al., 2009[57] | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, DASS-21 | 124 | Time from resection 2.6 ± 1.6 years | Compare HRQoL, mood, and clinical factors in patients < and ≥ 70 | Patients older than 70 reported worse physical function, fatigue, and dyspnea. However, the differences were not statistically significant. |

| Sartipy et al., 2009[38] | SF-36 | 117 | Preoperative to 6 months | Compare HRQoL in lobectomy versus pneumonectomy | Pneumonectomy had a larger impact on physical aspects of HRQoL than lobectomy at 6 months. There was no difference in mental component scores. |

| Fagundes et al., 2015[35] | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory | 60 | Preoperative to 3 months | Longitudinal PRO assessments to define symptom recovery trajectory | Fatigue, pain, shortness of breath, disturbed sleep, drowsiness severity peaked 3–5 days after surgery with recovery by 3 months |

| Fernando et al., 2015[36] | SF-36, SOBQ | 212 | Preoperative to 2 years | Evaluate HRQoL in high-risk patients undergoing sublobar resection | Patients reported worse dyspnea scores with segmentectomy (compared with wedge) and thoracotomy (compared with VATS). Poor baseline QoL scores was not associated with survival. |

| Zhao et al., 2015[58] | SF-36 | 217 | Postoperative 1 month to 1 year | Evaluate QoL following lobectomy, comparing VATS with thoracotomy | Bodily pain, energy, and physical role scores were better after VATS, compared with thoracotomy. |

| Yun et al., 2016[10] | EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-LC13, HADS, PTGI | 809 | Single survey in 1 year survivors only | Evaluate prognostic value of QoL for predicting survival | Physical functioning, dyspnea, personal strength, and anxiety were independent predictors of survival |

| Khullar et al., 2017 | PROMIS | 127 | Preoperative to 6 months | Integrate PRO into the STS-GTSD and to describe pattern of PRO after surgery | Physical function, pain, fatigue and sleep impairment are significantly worse than preop at 30 days after surgery, however recover towards baseline over 6 months |

HRQoL: Health-Related Quality of Life; EORTC: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QLQ-30: Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; QLQ-LC13: Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer Module; DASS-21: Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; SF-36: Short Form Health Survey; SOBQ: San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire; VATS: Video-assisted thoracic surgery; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PTGI: Post Traumatic Growth Inventory; PROMIS: Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System; PRO: patient reported outcomes; STS-GTSD: Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database. Reprinted from Khullar OV, Fernandez FG. Patient reported outcomes in thoracic surgery. Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 2017; 27:279–290, with permission from Elsevier.

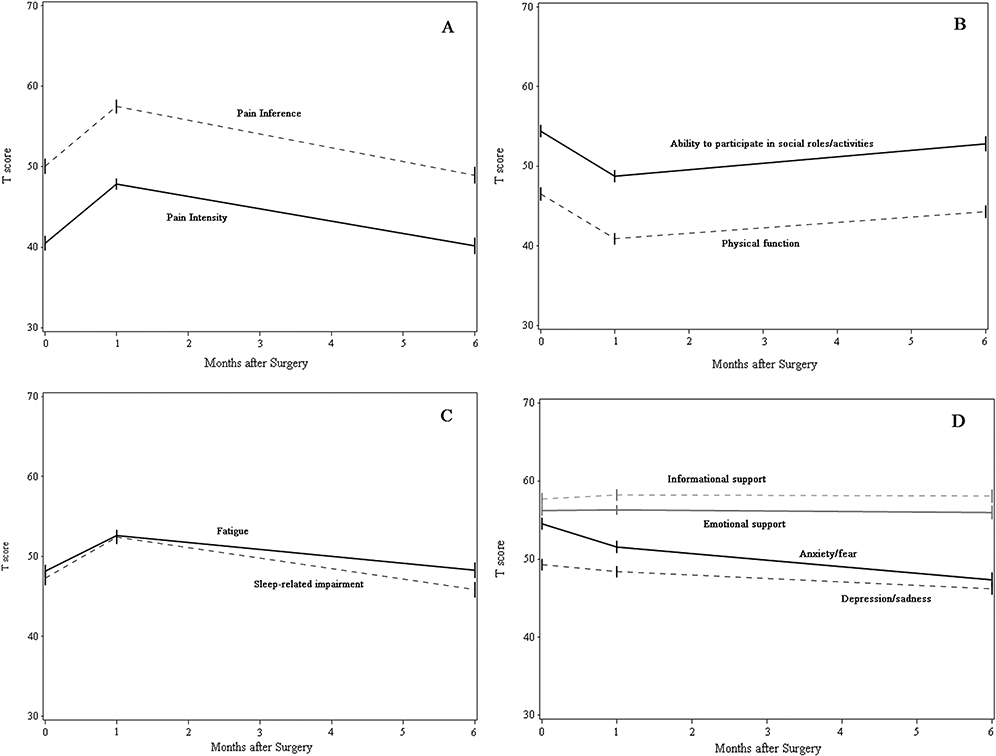

For example, in a prospective, observational study intended to show the feasibility and ease of incorporating PRO results into the STS General Thoracic Database (GTSD), two of the authors of this review (OK, FF) utilized the NIH-sponsored Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to assess 127 patients undergoing lung cancer resection. This study found a significant decline in patient-reported pain, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and physical function at 1 month after surgery, with near complete return to baseline by 6 months (Figure 1). Additionally, patients undergoing minimally invasive thoracoscopy, when compared with thoracotomy, reported better scores in physical function, pain intensity, fatigue, and ability to participate in social activities at the preoperative baseline assessment and 1-month postoperative assessment. When comparing PROs between patients treated with lobectomy vs. sublobar resection, no differences were identified [2].

Figure 1.

Postoperative PROMIS scores in patients who underwent lung cancer resection: (A) pain intensity and interference, (B) physical function, fatigue, and sleep-related impairment, (C) anxiety/fear and depression/sadness, and (D) ability to participate in social activities, emotional support, and informational support. Reprinted with permission from Khullar OV, Rajaei MA, Force SD et al. Pilot Study to Integrate Patient Reported Outcomes After Lung Cancer Operations Into The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2017; 104(1): 245–253.

Similarly, in a prospective observational study using the Short-Form 36 questionnaire, Zhao et al. found pain, energy and physical functioning to be worse after thoracotomy [37]. A secondary analysis of HRQoL in the ACOSOG Z4032 study cohort (n=212) showed significantly worse dyspnea scores at long-term follow-up after thoracotomy (compared with VATS), segmentectomy (compared with wedge resection), and with T1b tumors (compared with T1a) in high-risk operable lung cancer patients. Most importantly, poor baseline HRQoL scores were not associated with a higher risk of postoperative adverse events or worse survival [36].

In another excellent example of CER, Sartipy et al. performed a prospective comparison of patients undergoing lobectomy (n = 101) versus pneumonectomy (n = 16) using the Short-Form 36 questionnaire. Results from their analysis found a significantly greater decrease in physical function scores after pneumonectomy [38]. Lastly, in one of the largest studies, Yun et al. conducted surveys of over 800 patients undergoing lung cancer surgery. They investigated the relationship between PRO and long-term survival and found postoperative physical function, dyspnea, personal strength, and anxiety to be independent predictors of long-term survival [10].

A number of studies have been completed examining PRO after esophagectomy, with one review identifying a total of 58 studies, 41 prospective and 17 retrospective [30]. Most of these studies have similar findings showing that there is a considerable decline in HRQoL within one month after esophagectomy, with symptoms persisting between several months to several years [32–34, 39–41]. For example, Lagergren et al. found that physical function, breathlessness, diarrhea, and reflux were significantly worse one month after surgery (n=90). While some improvement was seen, all four symptoms remained significantly worse than baseline even after 3 years [39].

In another example of CER including PRO, de Boer et al. randomized approximately 200 patients to transhiatal or transthoracic esophagectomy and measured HRQoL utilizing the Short-Form 20 questionnaire from baseline up to 3 years postoperatively. At three months, patients in the transhiatal group reported fewer physical symptoms and better activity levels. However there were no differences identified at any time point afterwards [42]. In one prospective, randomized trial comparing surgical and non-surgical treatment for esophageal cancer HRQoL scores, Bonnetain et al. used the Spitzer QoL Index and found lower scores in the surgical arm at 3 months after surgery. However, no difference was found between the surgical and non-surgical arms in long-term follow-up as far as 2 years after treatment [34].

Potential for Incorporation of Patient-Reported Outcomes into the STS National Database

The STS ND is widely recognized as one of the premier clinical databases in the world. The database is particularly recognized for its comprehensive granularity, accurate risk-adjustment of common procedures, a variety of risk-calculators to guide preoperative decision making, and measurements of provider performance [43]. More recently, the STS ND has created composite quality measures that compare participant performance and are available for public reporting [43]. The STS ND, like other large national databases, currently measures surgical outcomes with standard clinical metrics including complication rates, readmission, and perioperative mortality [44, 45]. These outcomes are objective and relatively easy to measure and interpret. However, these traditional outcomes may not reflect what is most important to patients. Many adverse clinical outcomes such as operative mortality following many cardiothoracic operations (such as coronary artery bypass or lung cancer resection) are rare. These issues render routine outcome measures inadequate for evaluating the true quality of care delivered and for reliably comparing performance between institutions [3]. A critical gap in the STS ND is the absence of PROs. Incorporation of PROs into a large, national database such as the STS ND would allow surgeons to provide more patient-centered care and accelerate the implementation of patient-centered outcomes research.

Consider a patient with critical aortic valve stenosis seeking aortic valve replacement. Traditional outcomes for surgery in this patient include operative morbidity and mortality, long-term survival, re-intervention rate and heart function on echocardiogram. However, this patient sought surgery because of symptoms such as angina, dyspnea and/or syncope. Therefore, the most appropriate patient-centered outcomes metrics would be durable resolution of symptoms and restoration of quality of life. These PROs need to be assessed longitudinally, including the preoperative, postoperative, and long-term phases of care. Measurement at these time intervals allows assessment of the patient’s baseline function, any decrement in function following surgery, and the magnitude and durability of improvement over time.

The PROMIS is one platform that may be used to incorporate patient self-reporting into the STS ND [46]. PROMIS was specifically designed to establish a national resource for accurate, efficient, secure, and standardized measurement of patient-reported symptoms and other health outcomes in clinical research and clinical practice. PROMIS provides item banks for creating specific physical, mental, and social health status assessment instruments. PROMIS also includes Computer Adaptive Testing (CAT) based software that administers the most informative set of questions based on responses to previous questions. This capability provides for the efficient and precise measurement of PROs. PROMIS results are reported and analyzed using a standardized scoring system based on responses to the same questions in the United States general population [47]. The average score is for each instrument is 50 and each deviation of 10 points represents one standard deviation from the mean.

The STS recognizes the importance of PRO measurement and has commissioned a Task Force to explore the incorporation of PRO measures into the STS ND. Such an undertaking is challenging at an institutional level, and even more so for a national database comprised of thousands of institutions using a wide variety of medical records and information technology platforms. However, single institution studies have demonstrated the feasibility of collecting PRO data and integration with STS database records [2]. Early efforts have focused on identification of PRO measurement platforms and best practices for secure and efficient data collection. The STS plans to conduct pilot testing of PRO data collection in the near future to investigate the feasibility of incorporation of PROs into the STS ND.

Implementation of PROs: Data Collection, Analysis, and Potential Challenges

Implementing PROs into routine care is essential to accurately reflect the priorities of the patients reporting them. Moreover, even with seamless integration of PRO metrics into clinical workflow, the use of PROs must add value to patient care. Several randomized trials have indicated that incorporating HRQoL data into clinical practice facilitates patient-physician discussion of HRQoL issues and improves HRQoL without prolonging the clinic encounter [6, 48]. PROs are currently used in comparative effectiveness research and as primary outcomes in clinical trials. However, the shift towards patient-centered care and using PROs in routine clinical practice is a relatively new concept.

The two main considerations when implementing PROs into clinical care are workflow and infrastructure [49]. Workflow can further be categorized into PRO collection, score reporting and action (how the data will be used to guide care). Once the PRO questionnaire(s) have been developed for a particular patient group, considerations regarding PRO collection include: timing, mode and setting of administration. Timing of PRO assessment can be guided by HRQoL literature. For example, after lung cancer resection, up to 60% of patients continue to have pain at 6 months and half have increased dyspnea and fatigue, and decline in physical function at 2 years [50, 51]. Therefore, long-term PRO assessment for patients undergoing lung cancer resection is relevant. PROs can be obtained via paper, interview or electronically (computer, tablet or smartphone). The setting of PRO collection (home versus clinic visit) may influence which mode is used. As 80% of American households have at least one regular internet user, an electronic mode of PRO collection is ideal.

The sequence of PRO collection, followed by scoring, needs to occur in a way that allows for optimal use of this information by the clinician. In an ideal setting, PRO results would be available at clinic appointments in real-time and reviewed by clinical staff to help inform patient progress and medical decision-making. In the most basic example, patients may complete PRO questionnaires at home prior to a clinic visit. Alternatively, patients may complete questionnaires at specified intervals separate from outpatient visits. For this workflow, clinical staff need to track changes in PRO status and address issues via phone or EHR messaging. Another important workflow detail is determining who will receive the PRO reports [52]. In some health care teams, a nurse navigator may manage these reports. Processes for analyzing the PRO results and coordinating care in response to PRO responses are paramount. Some systems may provide patients with their results and if so, adequate context to interpret the results needs to be included in the report [52]. Clinicians need to receive useful PRO data to detect significant changes in HRQoL and determine whether a change in plan of care is needed. A useful PRO report includes both the raw and standardized scores and how those have changed over time. Lastly, prior to implementation of a PRO system, clinicians need to understand the meaning of the scores and approaches to responding to them. To assist clinicians in implementing PRO assessment, the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) has developed a User’s Guide for Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice [52, 53].

In terms of infrastructure, electronic collection of PRO data is preferred in the clinical setting and is associated with lower rates of missing data than paper forms [49]. Electronic collection involves either using a licensed or internet-based PRO system or using the built-in PRO assessment tool available in some EHRs [1]. In a review of electronic PRO (ePRO) systems, only 44% were directly integrated into the EHR [8]. However, there is increasing use of the EHR as a comprehensive system for managing clinical care. This increases the importance of integrating PRO data into the EHR which allows for PRO review at point of care alongside other relevant clinical data [49]. In its 2012 software release, Epic Systems Corporation (Verona, WI) included PROMIS measures [49]. Epic can be programmed to administer PRO at specified intervals or in response to patient encounters (clinic visit, surgery). In the 2017 version, there are 8 CAT domains with a limited number of short-forms available for additional purchase. PRO administration is designed to occur outside of the clinical encounter via patient portal (MyChart). Best practices for integrating PRO data into the EHR are currently unclear. To facilitate implementation of PRO into the EHR, a multidisciplinary team of PRO experts published the User’s Guide to Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes in Electronic Health Records [54]. This guide provides useful examples for a variety of health care systems ranging from low to high integration of PRO within the EHR. Successful implementation requires institutional commitment from leadership and the input and coordination of all stakeholders including patients, clinicians and administrators [8]. By minimizing burden and maximizing clinical relevance, PRO can have a meaningful impact on patient care.

Only one study has successfully measured PROs using PROMIS in patients undergoing lung cancer resection [2]. In that study, patients completed a PRO survey on the Assessment CenterSM website using a touch-screen tablet device at baseline and at 1 and 6 months after surgery. Importantly, PRO data were exported from the Assessment CenterSM and electronically merged with an institutional clinical database. This study established the feasibility of collecting PRO data and integrating these into an institutional clinical database [2]. The next step is to design a system whereby PRO data can simultaneously provide benefit for both clinical care and research in real time.

Conclusion

Integration of PROs into routine clinical practice and cardiothoracic studies is essential for providing high-quality patient care and optimizing CER. There is a greater push by multiple healthcare organizations and funding agencies to include PROs as primary or secondary outcomes. While there are examples of the use of PRO instruments in current cardiothoracic surgical research, there is still room for improvement. Incorporation of PROs into the STS ND will allow surgeons to provide more patient-centered care and accelerate the implementation of patient-centered outcomes research.

References

- 1.Basch E, Snyder C. Overcoming barriers to integrating patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice and electronic health records. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(10):2332–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khullar OV, Rajaei MH, Force SD et al. Pilot Study to Integrate Patient Reported Outcomes After Lung Cancer Operations Into The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2017; 104(1):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ. Measuring the quality of surgical care: structure, process, or outcomes? J Am Coll Surg 2004; 198(4):626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khullar OV, Fernandez FG. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Thoracic Surgery. Thorac Surg Clin 2017; 27(3):279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RS, Stukenborg GJ. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Use in Surgical Care: A Scoping Study. J Am Coll Surg 2017; 224(3):245–254.e241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288(23):3027–3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen MA, Larsen H, Pedersen L et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in palliative care: comparing patient and physician assessments. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42(8):1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen RE, Snyder CF, Abernethy AP et al. Review of electronic patient-reported outcomes systems used in cancer clinical care. J Oncol Pract 2014; 10(4):e215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pompili C, Absolom K, Velikova G et al. Patients reported outcomes in thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10(2):703–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun YH, Kim YA, Sim JA et al. Prognostic value of quality of life score in disease-free survivors of surgically-treated lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2016; 16:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pompili C, Novoa N, Balduyck B, Group EQolaPSW. Clinical evaluation of quality of life: a survey among members of European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015; 21(4):415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder CF. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer: a review of recent research and policy initiatives. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57(5):278–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colt HG, Murgu SD, Korst RJ et al. Follow-up and surveillance of the patient with lung cancer after curative-intent therapy: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(5 Suppl):e437S–e454S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical outcome assessment qualification program [http://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/drugdevelopmenttoolsqualificationprogram/ucm284077.htm]

- 15.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA 2012; 307(15):1583–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basch E, Torda P, Adams K. Standards for patient-reported outcome-based performance measures. JAMA 2013; 310(2):139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleif J, Waage J, Christensen KB, Gögenur I. Systematic review of the QoR-15 score, a patient- reported outcome measure measuring quality of recovery after surgery and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120(1):28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldfarb M, Drudi L, Almohammadi M et al. Outcome Reporting in Cardiac Surgery Trials: Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4(8):e002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen DJ, Van Hout B, Serruys PW et al. Quality of life after PCI with drug-eluting stents or coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(11):1016–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(14):1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Wang K et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) Trial (Cohort A). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60(6):548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein D, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns AC et al. Two-Year Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Severe Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(4):344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonaros N, Schachner T, Wiedemann D et al. Quality of life improvement after robotically assisted coronary artery bypass grafting. Cardiology 2009; 114(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishawi M, Shroyer AL, Rumsfeld JS et al. Changes in health-related quality of life in off-pump versus on-pump cardiac surgery: Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 95(6):1946–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelini GD, Culliford L, Smith DK et al. Effects of on- and off-pump coronary artery surgery on graft patency, survival, and health-related quality of life: long-term follow-up of 2 randomized controlled trials. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137(2):295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vicchio M, Della Corte A, De Santo LS et al. Tissue versus mechanical prostheses: quality of life in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85(4):1290–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folkmann S, Gorlitzer M, Weiss G et al. Quality-of-life in octogenarians one year after aortic valve replacement with or without coronary artery bypass surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 11(6):750–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conaway DG, House J, Bandt K et al. The elderly: health status benefits and recovery of function one year after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42(8):1421–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noyez L, de Jager MJ, Markou AL et al. Quality of life after cardiac surgery: underresearched research. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011; 13(5):511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straatman J, Joosten PJ, Terwee CB et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in the surgical treatment of patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29(7):760–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poghosyan H, Sheldon LK, Leveille SG et al. Health-related quality of life after surgical treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 2013; 81(1):11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derogar M, Lagergren P. Health-related quality of life among 5-year survivors of esophageal cancer surgery: a prospective population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(4):413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courrech Staal EF, Bloemendal KM, Bloemer MC et al. Oesophageal cancer treatment in a tertiary referral hospital evaluated by indicators for quality of care. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012; 38(2):150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnetain F, Bouché O, Michel P et al. A comparative longitudinal quality of life study using the Spitzer quality of life index in a randomized multicenter phase III trial (FFCD 9102): chemoradiation followed by surgery compared with chemoradiation alone in locally advanced squamous resectable thoracic esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 2006; 17(5):827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagundes CP, Shi Q, Vaporciyan AA et al. Symptom recovery after thoracic surgery: Measuring patient-reported outcomes with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 150(3):613–619.e612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernando HC, Landreneau RJ, Mandrekar SJ et al. Analysis of longitudinal quality-of-life data in high-risk operable patients with lung cancer: results from the ACOSOG Z4032 (Alliance) multicenter randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 149(3):718–725; discussion 725–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Zhao Y, Qiu T et al. Quality of life and survival after II stage nonsmall cell carcinoma surgery: Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy lobectomy. Indian J Cancer 2015; 52 Suppl 2:e130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sartipy U Prospective population-based study comparing quality of life after pneumonectomy and lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 36(6):1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagergren P, Avery KN, Hughes R et al. Health-related quality of life among patients cured by surgery for esophageal cancer. Cancer 2007; 110(3):686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avery KN, Metcalfe C, Barham CP et al. Quality of life during potentially curative treatment for locally advanced oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 2007; 94(11):1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Best LM, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS. Non-surgical versus surgical treatment for oesophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3:CD011498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Boer AG, van Lanschot JJ, van Sandick JW. Quality of life after transhiatal compared with extended transthoracic resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(20):4202–4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.STS National Database [http://www.sts.org/national-database]

- 44.Kozower BD, O’Brien SM, Kosinski AS et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Composite Score for Rating Program Performance for Lobectomy for Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 101(4):1379–1386; discussion 1386–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez FG, Kosinski AS, Burfeind W et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Lung Cancer Resection Risk Model: Higher Quality Data and Superior Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 102(2):370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.[www.healthmeasures.net/index.php]

- 47.PROMIS Scoring Manuals [http://www.assessmentcenter.net]

- 48.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(4):714–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen RE, Rothrock NE, DeWitt EM et al. The role of technical advances in the adoption and integration of patient-reported outcomes in clinical care. Med Care 2015; 53(2):153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayman EO, Brennan TJ. Incidence and severity of chronic pain at 3 and 6 months after thoracotomy: meta-analysis. J Pain 2014; 15(9):887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kenny PM, King MT, Viney RC et al. Quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(2):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res 2012; 21(8):1305–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aaronson N, Choucair A, Elliott T, et al. User’s Guide to Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. In.; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.WA S Users’ Guide to Integrating Patient-Reported Outcomes in Electronic Health Records. In.; 2017.

- 55.Li WW, Lee TW, Lam SS et al. Quality of life following lung cancer resection: video-assisted thoracic surgery vs thoracotomy. Chest 2002; 122(2):584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balduyck B, Hendriks J, Lauwers P et al. Quality of life after lung cancer surgery: a prospective pilot study comparing bronchial sleeve lobectomy with pneumonectomy. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3(6):604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferguson MK, Parma CM, Celauro AD et al. Quality of life and mood in older patients after major lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 87(4):1007–1012; discussion 1012–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ji Q, Zhao H, Mei Y et al. Impact of smoking on early clinical outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg 2015; 10:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]