Abstract

A key mutational process in cancer is structural variation, in which rearrangements delete, amplify or reorder genomic segments that range in size from kilobases to whole chromosomes1–7. Here we develop methods to group, classify and describe somatic structural variants, using data from the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium of the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which aggregated whole-genome sequencing data from 2,658 cancers across 38 tumour types8. Sixteen signatures of structural variation emerged. Deletions have a multimodal size distribution, assort unevenly across tumour types and patients, are enriched in late-replicating regions and correlate with inversions. Tandem duplications also have a multimodal size distribution, but are enriched in early-replicating regions—as are unbalanced translocations. Replication-based mechanisms of rearrangement generate varied chromosomal structures with low-level copy-number gains and frequent inverted rearrangements. One prominent structure consists of 2–7 templates copied from distinct regions of the genome strung together within one locus. Such cycles of templated insertions correlate with tandem duplications, and—in liver cancer—frequently activate the telomerase gene TERT. A wide variety of rearrangement processes are active in cancer, which generate complex configurations of the genome upon which selection can act.

Subject terms: Cancer genomics, Genomic instability

Whole-genome sequencing data from more than 2,500 cancers of 38 tumour types reveal 16 signatures that can be used to classify somatic structural variants, highlighting the diversity of genomic rearrangements in cancer.

Main

Mutations that arise in somatic cells are the driving force of cancer development. Structural variation—in which genomic rearrangement acts to amplify, delete or reorder chromosomal material at scales that range from single genes to entire chromosomes—is an especially important class of somatic mutation. Previous analyses of both cancer and germline genomes have enabled the description of several distinctive patterns of structural variants1–7, and hypotheses about the underlying basis of several of these patterns have been proposed on the basis of their clustering, orientation and associated copy-number changes. Hypothesis-driven in vitro studies are now beginning to reveal some of the mechanistic processes that generate these structures9–13, and generate further predictions that can be assessed in the genomic data. However, the landscape of structural variation in human cancer remains incompletely mapped and there are many complex structures that elude formal description.

The PCAWG Consortium aggregated whole-genome sequencing data from 2,658 cancers across 38 tumour types, generated by the ICGC and TCGA projects. These sequencing data were aligned to the human genome (reference build hs37d5) and analysed with standardized, high-accuracy pipelines to call somatic and germline variants of all classes8. Here, we analyse the patterns and signatures of structural variants across the PCAWG data. We propose a working classification scheme that encompasses known and newly identified classes of structural variants. We develop methods for annotating the observed structural variants in a given cancer genome, identifying a class of replication-based rearrangement processes that generate clusters of several structural variants. We explore the size, activity and genome-wide distribution of classifiable structural variant types across the cohort, using signature analysis to define how they correlate within patients. Other papers produced by PCAWG address complementary aspects of structural variants, including inference of positive selection acting on recurrently rearranged regions of the genome14, how structural variants affect the transcriptome15 and chromosome topology16, patterns of somatic retrotransposition17 and distribution of chromothripsis across cancer types18.

Classification of structural variants

A ‘structural variant’ manifests as a ‘junction’ between two ‘breakpoints’ in the genome (terms in inverted commas here and below refer to those defined in the glossary in Extended Data Table 1). Generally, there will be a change in copy number across a given breakpoint if only one side of the break is rescued by a structural variant; if both sides of a double-stranded DNA break are rescued, a ‘reciprocal’ or ‘balanced’ structural variant will result, without substantial copy-number change. We sometimes observe ‘clusters of structural variants’ in which several breakpoints occur close together, in time or in genomic space—usually both. Such spatial and/or temporal proximity generally, but not always, implies that the structural variants within a cluster are mechanistically linked. Clusters can be ‘phased’ (in which case all structural variants in the cluster resolve to a single derivative chromosome) or ‘unphased’, in which case the structural variants are carried on different derivative chromosomes. An example of the latter is a reciprocal translocation that results in two derivative chromosomes, each with a single interchromosomal breakpoint junction (Fig. 1).

Extended Data Table 1.

Glossary of key terms

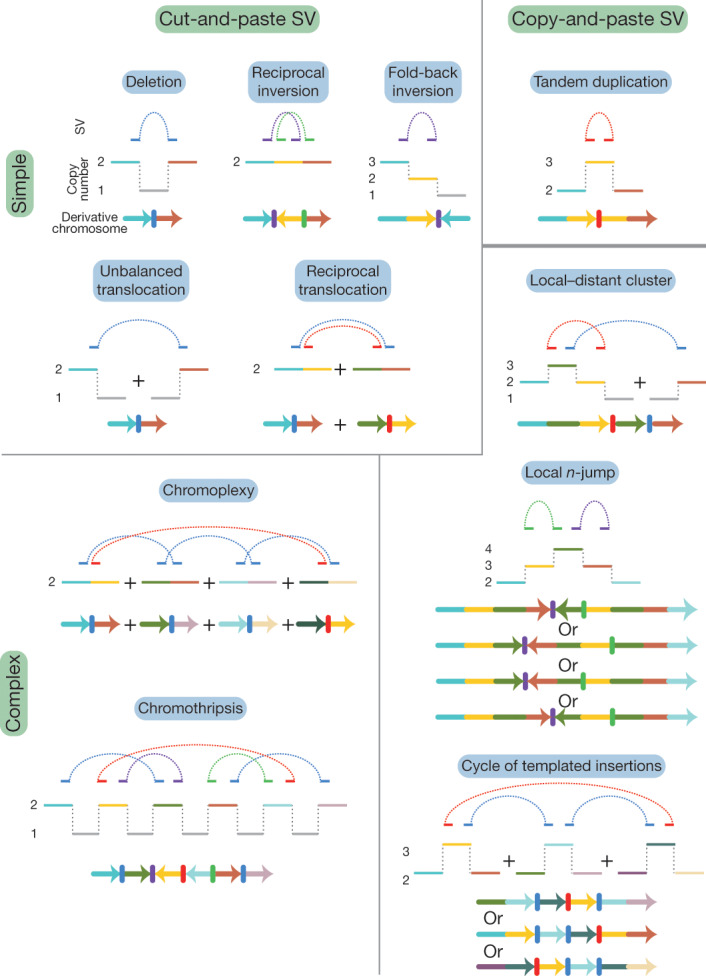

Fig. 1. Classification of structural variants in cancer genomes.

Schematics of major structural-variant (SV) classes, grouped according to whether they are simple or complex and arise through cut-and-paste or copy-and-paste processes. Each schematic comprises three parts. The top segment shows dotted arcs for each rearrangement junction that joins two chromosomal segments together. The middle segment shows the copy number of genomic segments that are involved. The bottom segment shows the configuration of the final derivative chromosome that results from the structural variant; the colour of the segments corresponds to the colour of that segment in the copy-number schematic. + indicates the different derivative chromosomes created for some of the classes: that is, the structural variants are not phased to a single derivative.

We recognize distinct ‘classes of structural variant’ from the orientation of the two segments at the junction and associated copy-number changes (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Some classes of structural variant (such as isochromosomes and rearrangements between extended, highly homologous sequences) are difficult to detect with short-read sequencing data; these classes are not considered further here. We propose categorizing classes of structural variant across two facets: the number of breakpoints involved (simple or complex) and by whether the patterns are likely to arise from ‘cut-and-paste’ or ‘copy-and-paste’ rearrangement processes. A cut-and-paste process generates a cluster of structural variants consistent with reshuffling or loss of extant genomic segments, and a copy-and-paste process is one in which copies of genomic ‘templates’ are newly replicated or synthesized and inserted during the rearrangement process. Deletions, reciprocal inversions, unbalanced translocations and reciprocal translocations are examples of simple cut-and-paste structural variants, as they can be reconstructed from the incorrect religation of chromosomal breaks. Tandem duplications are simple copy-and-paste structural variants, as they arise through the local insertion of a newly generated extra copy of a genomic template.

More-complex cut-and-paste processes that produce structural variants also occur in cancer. ‘Breakage–fusion–bridge’ events result from cycles of DNA breakage, end-to-end sister chromatid fusions, mitotic bridges and further DNA breakage. These events manifest as one or a few proximate, inverted breakpoint junctions with associated copy-number change, which we call ‘fold-back inversions’1,2,19 (Fig. 1). ‘Chromoplexy’5,20—which is particularly frequent in prostate cancers—results from several simultaneous double-stranded DNA breaks in several chromosomes that are rejoined incorrectly, leading to balanced chains of rearrangements. ‘Chromothripsis’3, in which chromosome shattering and rearrangement occur in a single catastrophic event9,21, leads to a pattern of oscillating copy-number changes and localized clustering of tens to hundreds of breakpoints22.

In the germline, more-complex copy-and-paste classes of structural variant have previously been described, which involve small duplications and triplications and are thought to arise from the stalling of the replication fork leading to template switching4,23,24. Here we describe a wide range of complex copy-and-paste types of somatic structural variant that occur in human cancers, and that are typically characterized by copy-number gains and frequent inverted rearrangements.

Annotation of structural-variant classes

We analysed 2,559 whole cancer genomes across 38 tumour types (alongside matched germline DNA) that passed the most stringent PCAWG quality-control criteria: 1 or more somatic structural variants were detected in 2,429 tumours8. As described in an accompanying Article8, structural variants were identified using aberrantly mapping and/or split reads in paired-end sequencing data25. We used four somatic structural-variant callers20,25–27, and the final structural-variant dataset comprised events that were returned by ≥2 callers, merged by a graph-based consensus method8. We consider only somatically acquired structural variants in this analysis, and exclude somatic retrotransposition events. Validation of structural-variant calls was undertaken using both manual inspection and pull-down with resequencing of breakpoints. With these approaches, we estimate the sensitivity of the consensus structural-variant call set to be 90% for true calls generated by any 1 of the 4 callers; specificity was estimated as 97.5%8. A mean of 3.22 algorithms of the 4 that we used called each structural variant in the consensus set genome-wide, and this differed little across repetitive elements: the mean for short interspersed nuclear elements was 3.22, and the mean for long interspersed nuclear elements was 3.21.

Because the structural variants from a given cancer are often highly clustered, we grouped rearrangements into clusters on the basis of the proximity of breakpoints, the overall number of events in that genome and the size distribution of these events (Supplementary Methods). Essentially, a particular cluster contains structural variants that are significantly closer together than expected by chance, given the overall number and orientation of structural variants in that patient. Alongside the clustering, we computed an in silico library of all possible genomic configurations that result from sequential simple structural variants (deletions, tandem duplications, inversions, translocations, and chromosome duplications or losses), to a depth of five rearrangements. We could then compare the genomic configuration of each observed cluster of structural variants against the library to determine how it might have arisen.

This methodology has the advantage that breakpoint junctions are classified according to the wider genomic context in which they occur. This means that, for example, true deletions will be identifiably different from breakpoint junctions that happen to have a deletion-type orientation but arise within (for instance) a chromothripsis event of markedly different mechanism and properties. Over half the breakpoint junctions that we observed arise within clusters of several or many structural variants (Fig. 2a): removing these junctions from the catalogues of true deletions, tandem duplications and inversions enables a more-precise description of the properties of simple structural variants.

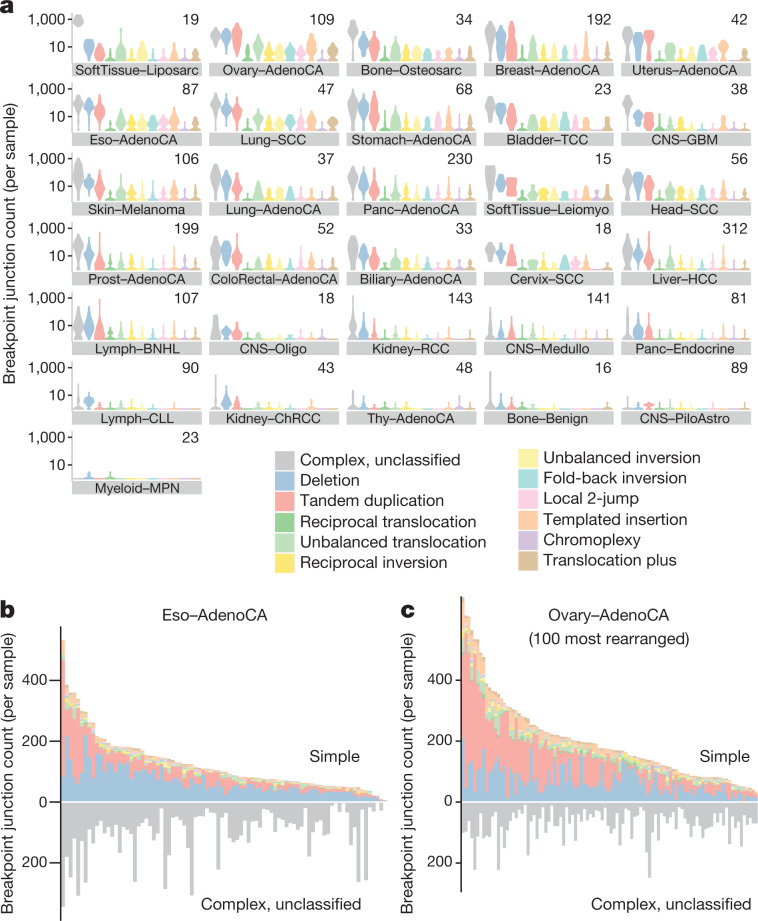

Fig. 2. Frequency of structural-variant classes across tumour types.

a, Violin plots of density of classified structural-variant categories across patients within each histology group. Tumour type panels are sorted in descending order of the average number of structural-variant breakpoints per sample. Within each tumour type, the frequency distribution (y axis) of different structural-variant categories (x axis) across patients is shown as a density: regions of highest density have the greatest width of shaded area. In each panel, the number of patients is indicated at the top right. AdenoCA, adenocarcinoma; BNHL, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; ChRCC, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CNS, central nervous system; GBM, glioblastoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; leiomyo, leiomyosarcoma; medullo, medulloblastoma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; eso, oesophageal; oligo, oligodendrocytic; panc, pancreatic; piloastro, pilocytic astrocytoma; prost, prostate; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; sarc, sarcoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TCC, transitional cell carcinoma; thy, thyroid. b, Per-sample counts of complex (bottom) and classified (top) structural-variant breakpoint junctions for oesophageal adenocarcinoma. c, Per-sample counts of complex (bottom) and classified (top) structural-variant breakpoint junctions for ovarian adenocarcinoma.

Among the classes of simple structural variants, deletion was the most common, followed by tandem duplication and then unbalanced translocation. Reciprocal translocations and reciprocal inversions were uncommon events (Fig. 2a). There was considerable variability in the overall numbers and distribution of classes of structural variant across tumour types and across patients within a given tumour type (Extended Data Fig. 1). For example, oesophageal adenocarcinomas were characterized by many deletions and a large number of complex clustered rearrangements (Fig. 2b), and ovarian cancers often carried high numbers of tandem duplications and/or deletions with moderate numbers of unbalanced translocations (Fig. 2c).

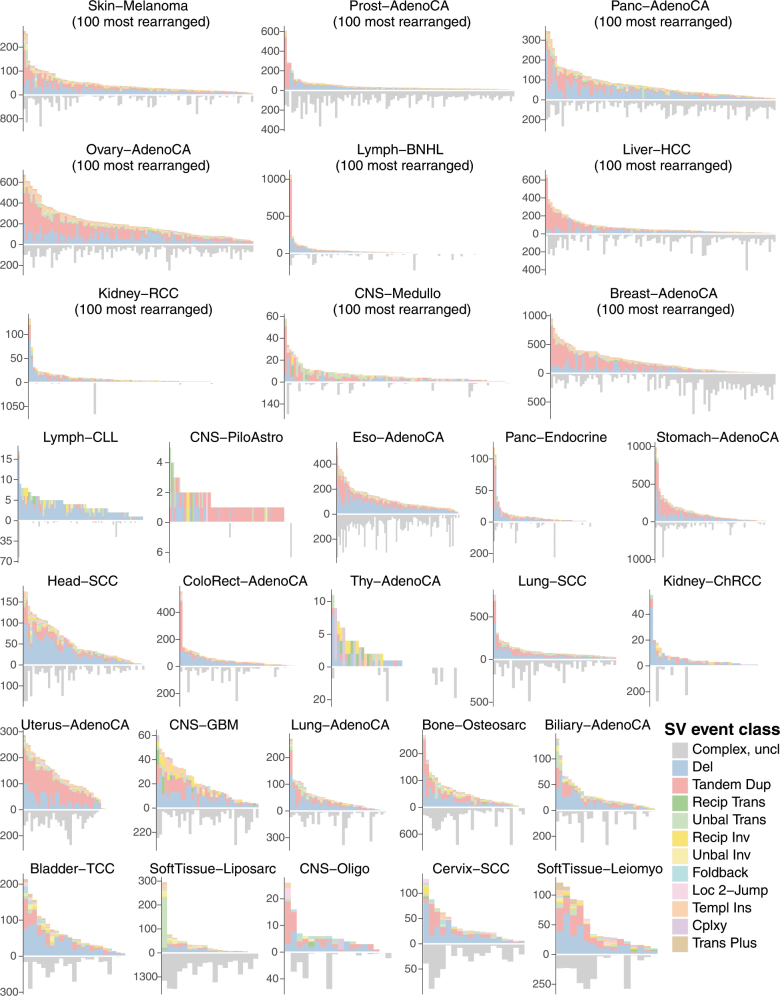

Extended Data Fig. 1. Per-sample counts of structural-variant breakpoint junctions by histology group.

Counts of simple, classified structural variants are shown above the x axis and counts of complex breakpoint junctions below the x axis. Patients within each tumour type are ranked by frequency of simple structural variants.

Cycles of templated insertions

We next examined clusters that contain 2–10 structural variants. One newly identified configuration consisted of several segments of copy-number gains, typically on different reference chromosomes, linked together through structural variants (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 2). A sequential path through consecutive segments can be formed by following the breakpoint junctions, which suggests that each cluster represents a string of duplicated templates inserted into a single derivative chromosome, probably acquired concurrently. Although it is theoretically possible that the structural variants in such clusters are not phased on the same derivative chromosome or do not occur concurrently, we think this is unlikely for several reasons. First, we found examples of RNA transcripts that spliced together exons separated by two junctions in the structural-variant cluster (Supplementary Fig. 2), which suggests that they are phased on the same derivative chromosome. Second, long-read sequencing data (reported in an accompanying Article8) supported the phasing of structural variants that link templated insertions. Third, we found that the clonal fraction of tumour cells tended to be more similar for structural variants within these clusters than for randomly chosen structural variants in each patient (Supplementary Fig. 3), which suggests that they co-occur in evolutionary time. Fourth, the level of copy-number gain for individual segments in the cluster tended to be identical (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 2).

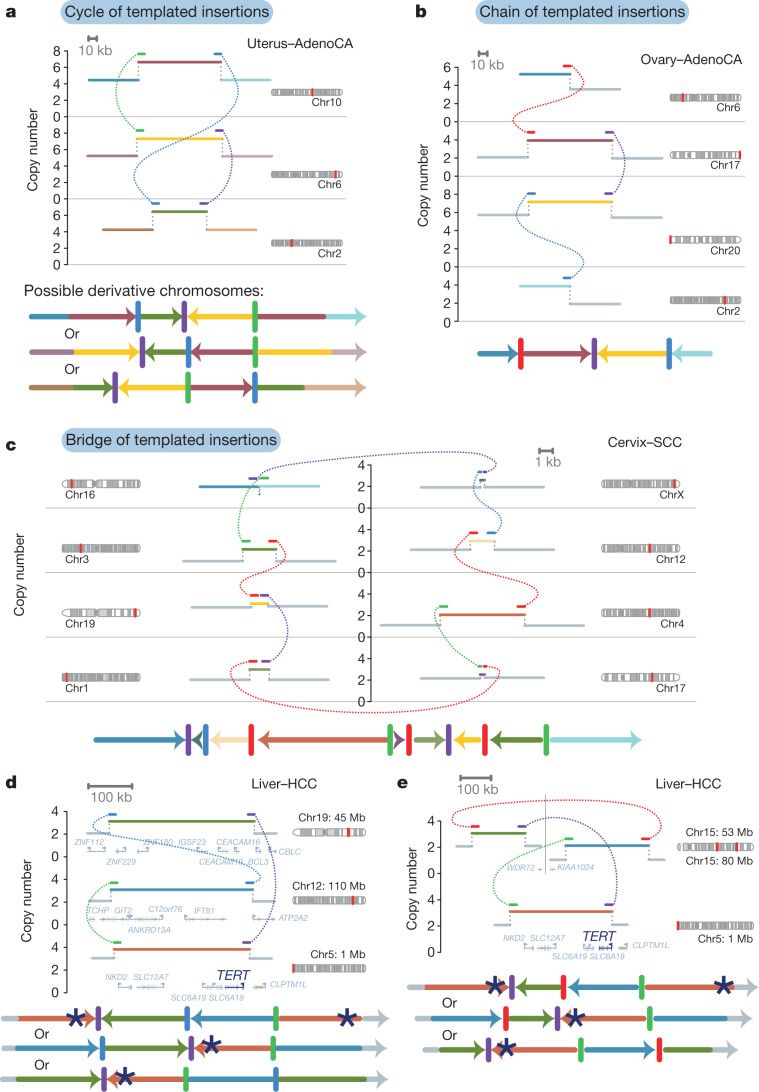

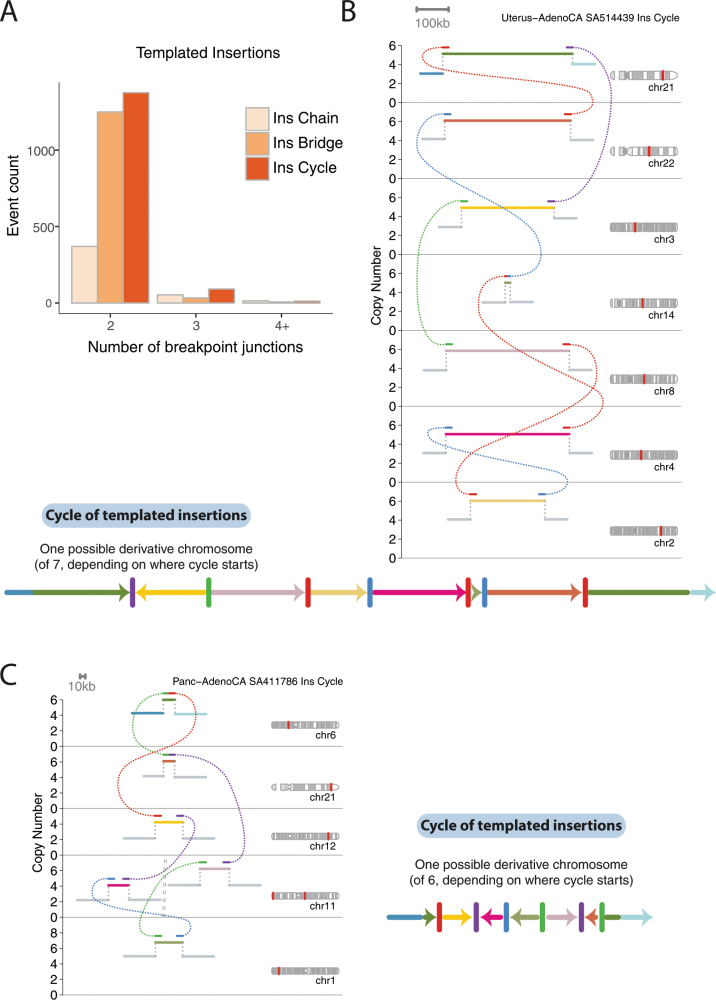

Fig. 3. Chains, cycles and bridges of templated insertions.

a–c, Examples of a typical cycle (a), chain (b) and bridge (c) of templated insertions. The estimated copy-number profile is shown as in Fig. 1, with structural variants shown as dotted arcs linking two copy-number segments. The derivative chromosome(s) that could explain the copy-number and structural-variant profile is shown below. d, e, Cycles of templated insertions that affect the TERT gene, in two hepatocellular carcinomas. KIAA1024 is also known as MINAR1.

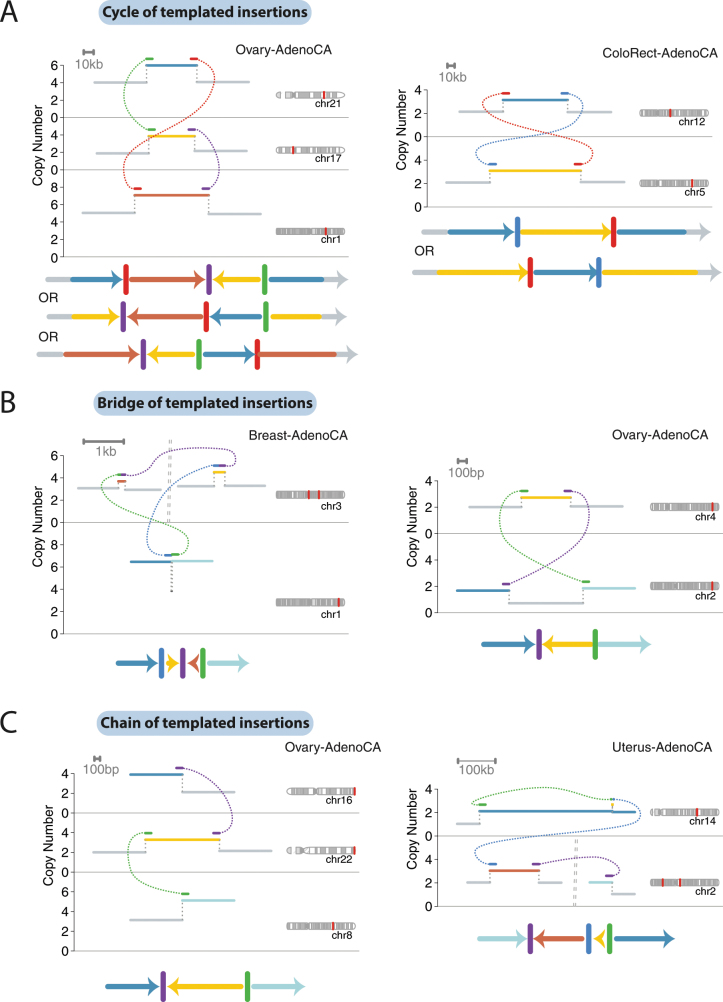

Extended Data Fig. 2. Further examples of templated insertion chains, cycles and bridges.

Schematics follow the same structure as in Fig. 3.

We define three basic categories on the basis of whether or not the string of inserted segments returns to the original chromosome: we term strings of inserted segments that do not return ‘chains’ of templated insertions and those strings that do return ‘bridges’ (which leave a gap on the host chromosome) or ‘cycles’ (which rereplicate a segment on the host chromosome). In the PCAWG dataset overall, we observed 1,467 cycles and 1,275 bridges of templated insertions (Fig. 3a, b, Extended Data Fig. 2). In chains of templated insertions, the string of genomic segments does not return to the chromosome of departure (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 2) but it is similarly associated with copy-number gains at each templated segment. There were 285 instances of such chains in the dataset, commonly manifesting as unbalanced translocations joined through one or more intermediary templated insertions.

Most templated insertion events involve only two breakpoint junctions, but this can extend to three, four or more linked rearrangements (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The longest such event—from a cervical squamous cell cancer—had seven templated insertions strung together on an eighth host chromosome (Fig. 3c; other examples of long templated insertion events are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Number of breakpoint junctions in cycles, bridges and chains of templated insertions.

a, Histogram of numbers of breakpoint junctions in templated insertion cycles, chains and bridges across all samples in all tumour types in the cohort. b, c, Two examples of particularly long cycles of templated insertions in the cohort. Examples are depicted in a similar manner to those in Fig. 3.

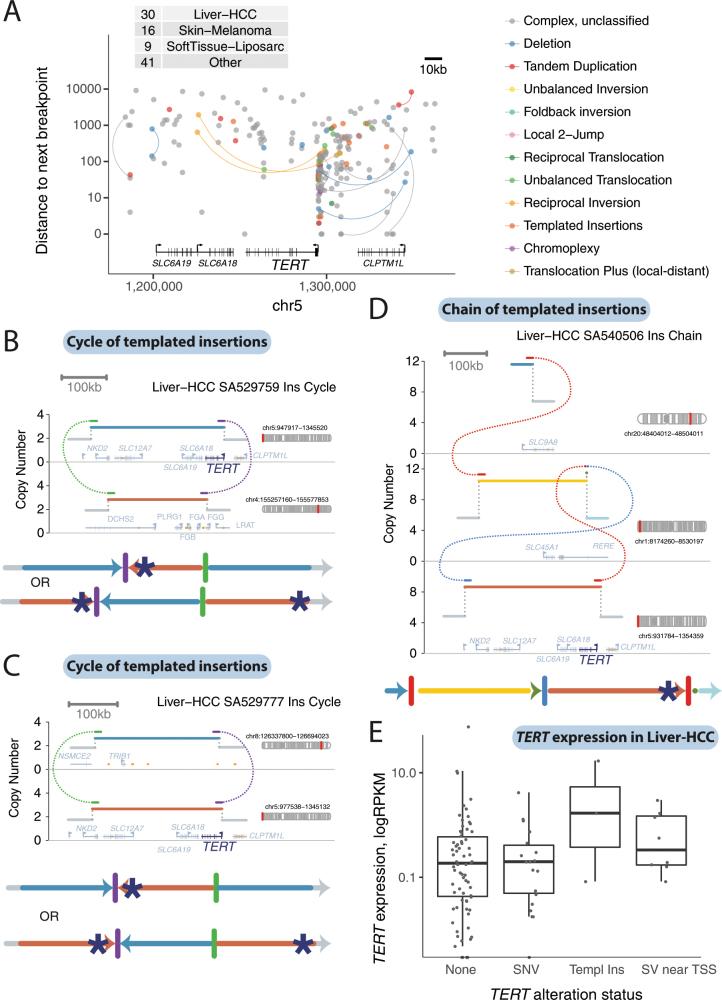

Templated insertions that affect TERT

Structural variants drive tumour development through their effects on cancer genes, whether by altering gene copy number, disrupting tumour-suppressor genes, creating fusion genes or juxtaposing the coding sequence of one gene with the regulatory apparatus of another. We found that many liver cancers had cycles of templated insertions that affect TERT (Fig. 3d, e, Extended Data Fig. 4). Point mutations in the TERT promoter are present in 54% of liver cancers, and a further 5–10% of liver cancers have structural variants that activate the gene28. Of the 30 patients with liver cancer that had structural variants that affect TERT, we find that 10 of these variants were templated insertion events (mostly cycles). All of these events duplicated the entire TERT gene and linked it to duplications of whole genes, fragments of genes or regulatory elements from elsewhere in the genome, and led to increased expression of TERT (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Thus, this particular rearrangement process is distinctive for the precision with which cancer copy-and-pastes normally disparate functional elements of its genome together without wholesale instability.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Templated insertion events that activate TERT in hepatocellular carcinoma.

a, The positions of all structural-variant breakpoints in the TERT region in the PCAWG cohort (including 50-kb flanks either side of TERT), coloured by classification and vertically spaced by the distance to the next breakpoint in the cohort. If the two sides of a breakpoint junction are contained within the plotting window, they are joined by a curved line. The number of samples with a breakpoint in the plotting window is annotated in the table in the top left. b–d, Examples of two cycles and a chain of templated insertions that affect TERT in hepatocellular carcinomas. e, Expression levels of TERT in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 187 patients), separated by whether TERT was wild type, had an activating promoter point mutation, structural variants in a templated insertion or other class. Individual patient data are shown as points. The box shows the median expression level as a thick black line, with the range of the box denoting the interquartile range. The whiskers show the range of data or 1.5× the interquartile range (whichever is lower).

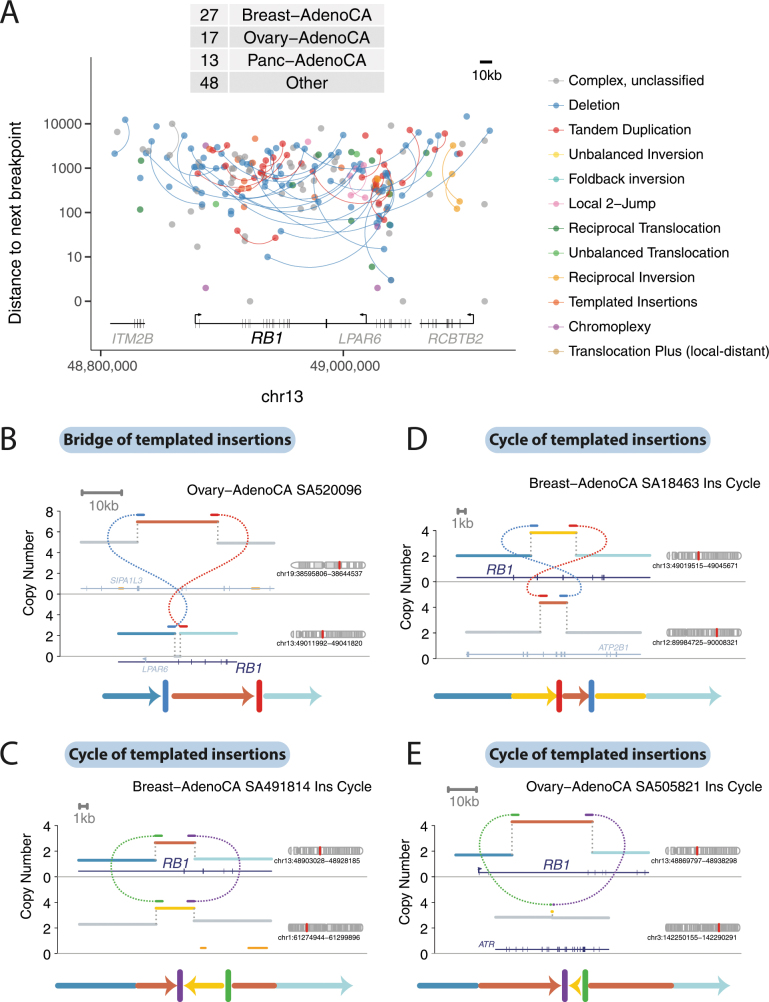

Tumour-suppressor genes were also inactivated by templated insertions (Extended Data Fig. 5). For example, among many straightforward deletions, RB1 was hit by cycles of templated insertions, a templated insertion with deletion and one instance of the linked, inverted duplications detailed in ‘Local n-jumps and local–distant clusters’. These events typically generated duplications of internal exons in RB1 and/or insertions of exons from other genes, all of which presumably rendered a non-functional transcript.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Templated insertion events inactivating RB1 in breast and ovarian carcinomas.

a, The positions of all structural-variant breakpoints in the RB1 region in the PCAWG cohort (including 50-kb flanks either side of RB1), coloured by classification and vertically spaced by the distance to the next breakpoint in the cohort. If the two sides of a breakpoint junction are contained within the plotting window, they are joined by a curved line. The number of samples with a breakpoint in the plotting window is annotated in the table in the top left. b–e, Examples of three cycles and a bridge of templated insertions that affect RB1 in breast and ovarian carcinomas.

Local n-jumps and local–distant clusters

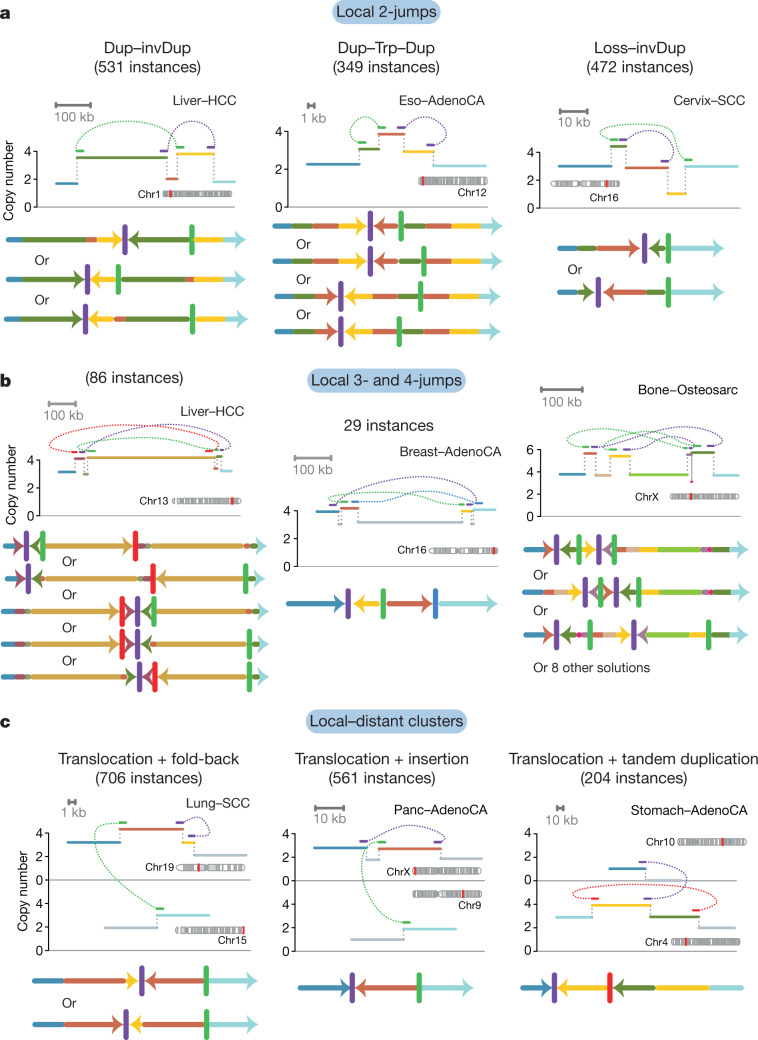

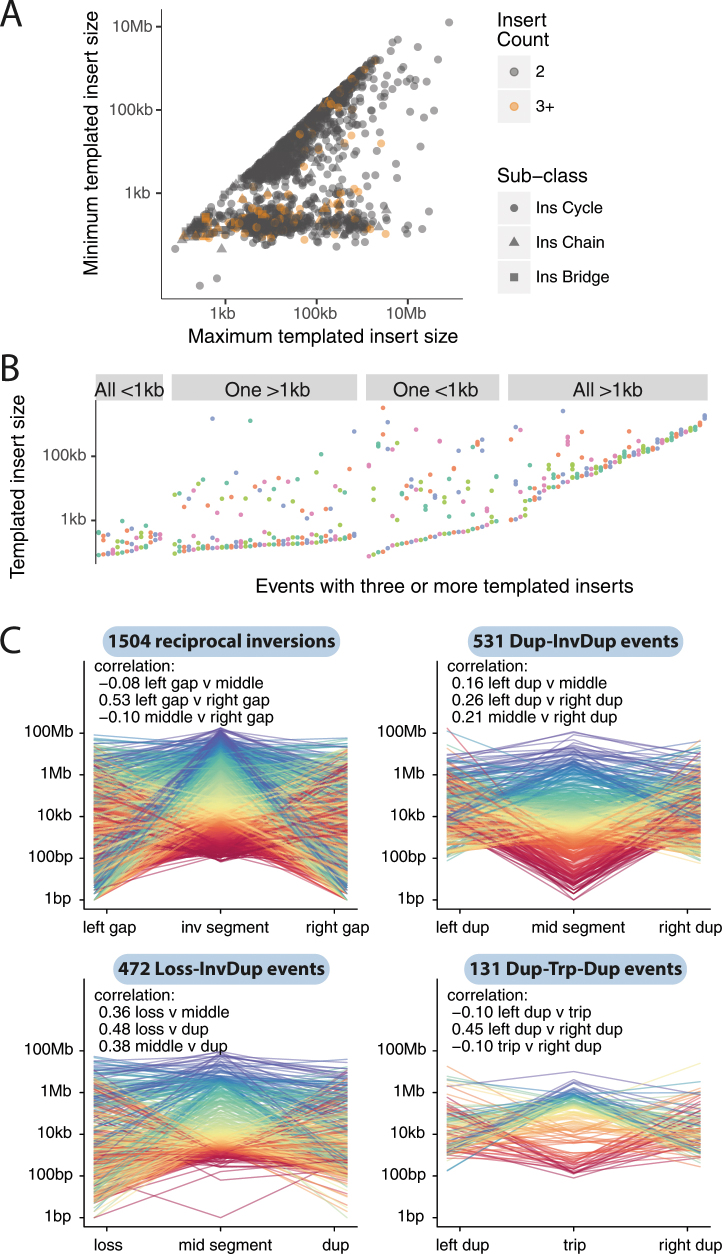

Many clusters of 2–10 structural variants in the dataset were confined to a single genomic region. Of those clusters that comprised two local rearrangements, some had straightforward explanations, such as nested or adjacent tandem duplications. However, many did not have a trivial explanation (Fig. 4a). These included a duplication–inverted-triplication–duplication structure that has previously been observed in germline structural variants24 (349 instances); a structure of two duplications linked by inverted rearrangements (531 instances); and structures of copy-number loss plus nearby duplication linked by inverted rearrangements (472 instances). All of these patterns had solutions in which breakpoints were phased to a single derivative chromosome (Fig. 4a), although non-phased solutions are theoretically possible (if unlikely). Beyond clusters of two rearrangements (two-jumps), we also found examples involving three, four or more rearrangements confined to one genomic locale (Fig. 4b). All of these configurations of clusters of structural variants can be phased to a single derivative chromosome, with tightly grouped breakpoints.

Fig. 4. Examples of clusters of 2–5 rearrangements seen in human cancers.

a, Structures created by two local rearrangements that cannot easily be explained by simple structural-variant classes (which we call local 2-jumps). The estimated copy-number profile is shown as in Fig. 1, with structural variants shown as dotted arcs linking two copy-number segments. Possible configurations of the derivative chromosome are shown below; multiple solutions are possible for each example. Dup, duplication; invDup, duplication linked by inverted rearrangement; trp, triplication. b, Structures created by 3–4 local rearrangements that cannot easily be explained by simple structural-variant categories. c, Structures created by one local rearrangement and one rearrangement that reaches elsewhere in the genome (local–distant clusters).

Beyond clusters confined to a single genomic region, we found clusters of 2–10 structural variants that combined local jumps with rearrangements that reach into one or more distant regions of the genome (Fig. 4c). Simple examples of these events include unbalanced translocations or large deletions with a locally derived fragment inserted at the breakpoint, but there was also an extensive range of more-complex patterns. In some cases, the source of the inserted fragment was distal to the major break, and the structural variant could feasibly result from several concurrent DNA breaks in close spatial proximity to the capture of a short DNA fragment during repair (cut-and-paste). In other cases, the origin of the inserted fragment was proximal to the major break and associated with a gain in copy number. This pattern is difficult to explain by a cut-and-paste mechanism, because the copy-number gain implies the inserted segment was a duplicate of the original template rather than a separated fragment redistributed from its original locus. Instead, a copy-and-paste mechanism may be the more parsimonious explanation for these events.

A comparison of local footprints linked together through distant rearrangements revealed a strong connectivity of footprints with the same or similar structure, often enriched tenfold or more than expected by chance (see ‘Footprint connectivity analysis’ in Supplementary Results). The reasons for this are unclear, but it may reflect innate structural symmetry introduced through the generation or the resolution of rearrangements, or through the repeated action of a mechanism that imparts consistent structural motifs.

Copy-and-paste patterns of clusters

The diverse patterns of 2–10 clustered structural variants (Figs. 3, 4) share important morphological features: (1) genomic configurations that can be phased to a single derivative chromosome; (2) low-level gains in copy number, especially duplications and triplications; (3) a high frequency of inverted rearrangements in addition to noninverted rearrangements; (4) occurrence on a chromosome background with similar average copy number to the tumour overall; and (5) tight proximity of breakpoints within the local footprint (typically <1 Mb).

Using our in silico library of genomic configurations, we could define all possible routes by which sequential structural variants could generate these structures through the classically defined repertoire of deletion, tandem duplication, inversion and translocation (Supplementary Fig. 4). These routes typically would require implausible machinations of chromosomes (Supplementary Results). In particular, the high prevalence of inverted breakpoint junctions and local copy-number gains is difficult to recreate using sequential simple rearrangements. Simple inversion events are uncommon in cancers (Fig. 1d) and they tend not to generate copy-number gains, except through breakage–fusion–bridge cycles: these latter also cause terminal deletions2, which are not seen in the events discussed here.

If these events cannot be satisfactorily explained by sequential simple rearrangements, another possible explanation is a complex cut-and-paste mechanism such as chromothripsis, chromoplexy or repeated breakage–fusion–bridge cycles. However, the patterns of the 2–10 clustered structural variants do not fit with these processes either (Supplementary Results). Although chromothripsis with copy-number gain has previously been described3,11,19,22, the resulting copy number and rearrangement patterns have different properties to those we observed. Chromoplexy, in which chromosome breaks lead to a balanced interchange at multiple breakpoint junctions5,20, typically generates unphased solutions. Repeated breakage–fusion–bridge cycles tend to cause high-level copy-number gains associated with inverted, fold-back rearrangements1,2, unlike the structures reported here.

Instead, we believe that many of these locally complex clusters of structural variants with low-level copy-number gains are generated in a single event by a copy-and-paste process. That is, the copying of genomic templates is an intrinsic aspect of the structural variation process in these events, with the extra copies being inserted in the resulting derivative chromosome. If the genomic templates all originate locally, we would observe local n-jumps (such as in Fig. 3a, b) with a tight clustering of breakpoints, phased solutions, frequent copy-number gains and a mix of inverted and noninverted breakpoint junctions. If the original templates for the copied segments derive from across the genome, chains, cycles and bridges of templated insertions would arise (Fig. 2).

Genomic properties of structural variants

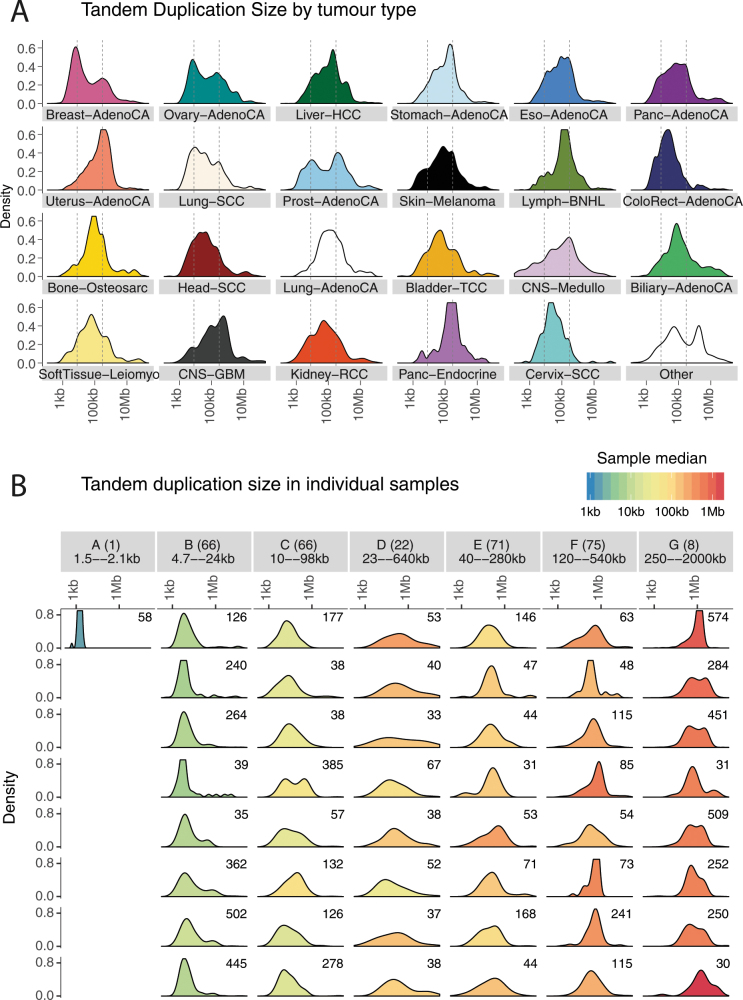

The size of tandem duplications and deletions followed complex—often multimodal—distributions across tumour types (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 6a). However, as previously reported6,29, individual patients tend to have a simpler—usually unimodal—distribution of deletions or tandem duplications (Extended Data Fig. 6b), which implies that the complexity seen in a given tumour type results from combining samples with different profiles. The sizes of individual fragments in templated insertion events were also distinctly multimodal, with varying peak heights across tumour types (Fig. 5b). When correlating template sizes within a given event, two patterns emerged: one in which template sizes were closely correlated with one another, and one in which a small (<1 kb) template was linked with one of any size (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). Likewise, the sizes of segments within a given local two-jump event showed moderately strong correlations with one another (Extended Data Fig. 7c).

Fig. 5. Size distribution and genomic properties of classified structural variants.

a, Size distribution of deletions per histology group, with tumour types ordered according to total number of events seen. Vertical dashed lines represent the two prominent modes. b, Size distribution of segments of templated insertion per histology group. For each tumour type, the three distributions for cycles, bridges and chains of templated insertions are superimposed. Ins, insertion. c, Associations between a subset of the genomic properties (rows) and classes of structural variant (columns). Each density curve represents the quantile distribution of the genomic property values at observed breakpoints compared to random genome positions. Asterisks indicate a significant departure from uniform quantiles after multiple hypothesis correction on a one-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test based on a sample size of 2,559 genomes containing structural variants: *false-discovery rate < 0.01, **false-discovery rate < 0.001, ***false-discovery rate < 10−6. Cells with significant property associations are shaded by the magnitude of the shift of the median observed quantile above (blue) or below (red) 0.5. The interpretation of each property from left to right is indicated by the axes to the right of the property label. Complex uncl, complex clusters unclassified; cplxy, chromoplexy; del, deletion; inv, inversion; ins, insertion; LAD, lamina-associated domain; recip, reciprocal; TAD, topologically associated domain; TD, tandem duplication; trans, translocation; unbal, unbalanced. d, Rearrangement counts as a function of bases of junction microhomology, fit to three linear functions consistent with different formation mechanisms. NHEJ, non-homologous end joining; MMEJ, microhomology-mediated end joining; SSA, single-strand annealing. e, Enrichment or depletion of breakpoint junctions between regions of the genome with particular annotations, compared with a permuted background that preserves breakpoint positions but swaps breakpoint partners. Centre points are the mean fold change over the permuted background; error bars represent three s.d. Analysis is based on a sample size of 2,559 genomes containing structural variants. LTR, long terminal repeat; SINE, short interspersed nuclear element; LINE, long interspersed nuclear element; heterochrom, heterochromatin.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Size distribution of tandem duplications.

a, Size distribution of tandem duplications per histology group. b, Samples with more than 20 tandem duplications were grouped using hierarchical clustering according to the within-patient distribution of tandem-duplication size. Seven clusters emerged, with the size distribution of up to eight randomly chosen samples per cluster illustrated. The numbers in the top right of each panel denote the number of tandem duplications in that sample.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Size properties of clustered structural-variant classes.

a, Comparison of the minimum and maximum templated-insert size for multi-insert cycles, chains and bridges of templated insertions. b, All events with three or more templated inserts, grouped by combination of insert sizes. c, Correlations (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) and raw sizes of individual genomic segments for reciprocal inversions and local two-jumps. Each individual event is shown as a line that links the size of the individual segments in that event. The sample sizes for each event class are shown in the labels for each panel.

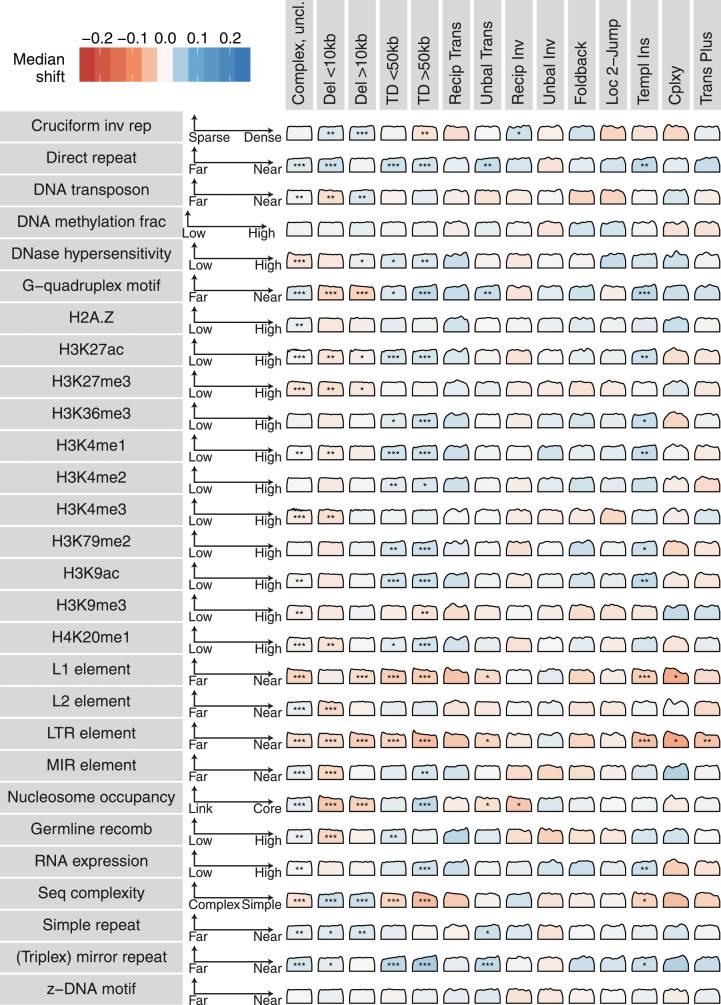

A number of genomic properties (such as replication timing, transcriptional activity and chromatin state) influence the density of point mutations30,31 and copy-number alterations32, but how this relates to individual classes of structural variant is unclear. From the literature, we compiled a library of the genome-wide distribution of 38 features including replication timing, GC content, repeat density, gene density and distance to G-quadruplex motifs, among others. Replication timing had the strongest association with the occurrence of structural variants; deletions are enriched in late-replicating regions, and tandem duplications and unbalanced translocations occur preferentially in early-replicating regions (Fig. 5c, Extended Data Fig. 8). For individual patients with high numbers of deletions or tandem duplications, we observed notable heterogeneity in the distribution of these structural variants according to replication timing: some had events that occurred predominantly in late-replicating regions, others had events that occurred exclusively in early-replicating regions, and in others events were distributed more evenly (Supplementary Fig. 5). Regions of active chromatin and increased gene density correlated positively with the rate of rearrangement.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Relationship of an extended panel of genomic properties with structural-variant categories.

Associations between a subset of the genomic properties (rows) and classes of structural variant (columns). Each density curve represents the quantile distribution of the genomic property values at observed breakpoints, compared to random genome positions. Asterisks indicate significant departures from uniform quantiles after multiple hypothesis correction by the Benjamini–Yekutieli method on a one-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, based on a sample size of 2,559 genomes containing structural variants: *false-discovery rate < 0.01, **false-discovery rate < 0.001, ***false-discovery rate < 10−6. Cells with significant property associations are shaded by the magnitude of the shift of the median observed quantile above (blue) or below (red) 0.5. The interpretation of each property from left to right is indicated by the axes to the right of the property label.

A structural variant requires DNA repair pathways to join two sequences together, and several repair mechanisms are available to somatic cells. Some require sequence homology between the two ends, and others can operate to join non-homologous sequences. As previously reported2,25,33, we find across the PCAWG data that many structural variants do not have sequence homology at the breakpoint junction (Fig. 5d) and therefore arise through non-homologous end joining. Nonetheless, a sizable fraction of structural variants has more microhomology than expected by chance, with an apparently bimodal distribution of microhomology lengths. One set of structural variants has 2–7 bp of microhomology, probably generated by microhomology-mediated end joining, and a second set of structural variants has 10–30 bp of microhomology, probably generated through single-strand annealing or other forms of homologous recombination (including microhomology-mediated break-induced replication). Repetitive sequences in the genome, such as short and long interspersed nuclear elements, are the likely substrate of such structural variants, and we find enrichment for structural variants joining such elements (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 6).

Signatures of structural variation

The heterogeneous spectrum of point mutations across cancers can be reconstructed from the differential action of a relatively limited repertoire of mutational processes, each with a characteristic signature34. The differences across patients in the size distribution of tandem duplication and deletion—together with the widely varying frequency and patterns of structural variant across tumour types and genome topology—suggested that we could similarly learn such correlations across individual classes of structural variant.

We divided the set of structural variants of each patient into mutually exclusive categories. We split the most frequent classes of simple structural variant (deletions and tandem duplications) into 11 categories according to size, replication timing and occurrence at fragile sites. Other configurations of structural variants and copy-number changes seen more than 50 times in the cohort were included as further categories, including cycles, chains and bridges of templated insertions (also split by size), local n-jumps and local–distant clusters.

We applied two methods for signature discovery, which yielded comparable results. We identified 16 structural-variant signatures: the 12 most prevalent of these signatures are shown in Fig. 6a. Signature extraction on the cohort randomly split into two halves identified ten highly correlated signatures (Supplementary Fig. 7), which closely matched the signatures called in the full cohort despite the lower power. Three signatures of deletions emerged, split by size: the signature of small (<50-kb) deletions included small reciprocal inversions and the signature of large (>500-kb) deletions included large reciprocal inversions. This implies that the frequencies of deletions and reciprocal inversions are correlated across the cohort, and both follow similar size distributions within an individual patient.

Fig. 6. Structural-variant signatures in human cancers.

a, The 12 most distinctive structural-variant signatures extracted by the Bayesian hierarchical Dirichlet process algorithm, run on a sample size of 2,559 genomes containing structural variants. Here the lengths of the bars represent the estimated proportion of each event class assigned to each signature (rows sum to one); the black line segments represent the 95% posterior interval for bar length from the Markov chain. FB, fold-back; mid, mid-sized. b, Association of pathogenic mutations (germline and somatic combined) in key DNA repair genes with structural-variant signatures. The sample size of patients who have pathogenic variants in the specific genes assessed is shown in brackets after each gene label (y axis). Hypothesis tests and effect sizes for each gene are derived from linear models for signature intensity after correction for histology. Significant associations from two-sided tests with correction for multiple hypothesis testing are shown. The colour and size of the points represent the estimated effect sizes. MSH refers to MSH2, MSH3, MSH4 and MSH6, genes in the mismatch repair pathway; FANC refers to genes associated with Fanconi anaemia, namely FANCA, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCI, FANCL and FANCM.

We identified five signatures of tandem duplications, split by size and replication timing. Cycles, bridges and chains of templated insertions were particularly prominent in signatures of early-replicating tandem duplications, whereas local two-jump structures were more closely associated with late-replicating tandem duplications. All of these patterns exemplify the copy-and-paste concept, in which extra copies of genomic templates are produced and inserted as an integral feature of the structural-variant process.

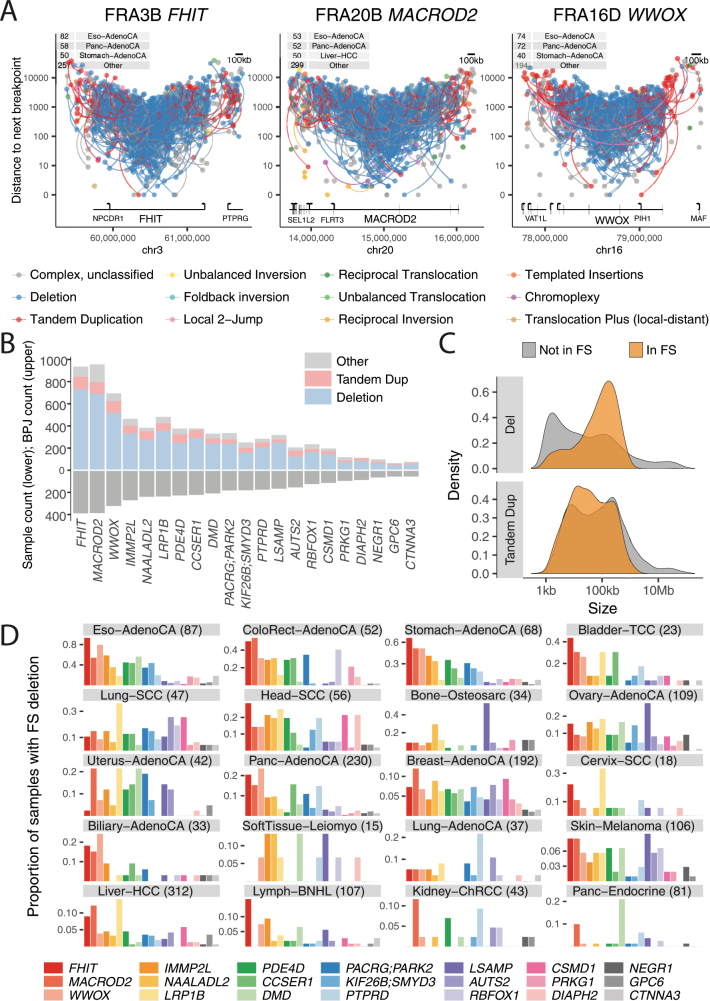

Another signature was characterized by deletions and tandem duplications at chromosomal fragile sites35. Tandem duplications were more prominent at the edges of the fragile site, and deletions were concentrated in the centre (Extended Data Fig. 9a, b). The size range of fragile site deletions peaked at around 100 kb, similar to the larger deletion signature, whereas the rarer fragile-site tandem duplications showed no strong size peak (Extended Data Fig. 9c). Sites of fragility varied extensively across tumour types (Extended Data Fig. 9d).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Properties of structural variants at chromosomal fragile sites.

a, Structural-variant breakpoints in the most affected fragile sites: FHIT, MACROD2 and WWOX. These are coloured by classification and vertically spaced by the distance to the next breakpoint in the cohort. If the two sides of a breakpoint junction are contained within the plotting window, they are joined by a curved line. The number of samples with a breakpoint in the plotting window is annotated in the tables at the top left. b, Number of deletions and tandem duplications (top) and number of affected samples (bottom) for the 18 fragile sites considered in this analysis. c, Size distribution of deletions and tandem duplications in fragile sites (FS) compared to the rest of the genome. d, Fragile-site preference for 20 cancer histology groups as indicated by the proportion of samples that contains a deletion in each of the 18 fragile sites considered here. The number of samples is indicated in parentheses.

Unbalanced translocations comprised their own signature, which suggests that they derive from a distinct rearrangement process in cancer genomes. A further signature comprised both the fold-back inversions that are a hallmark of breakage–fusion–bridge cycles and similar structures such as translocations adjacent to fold-back inversions. Finally, there was a signature of balanced rearrangements, including reciprocal translocations and chromoplexy clusters5. This signature probably arises from several double-stranded DNA breaks (potentially occurring in interphase), in which both sides of the break are incorrectly repaired through ligation to other, simultaneously broken regions of the genome.

DNA repair genes and tumour type

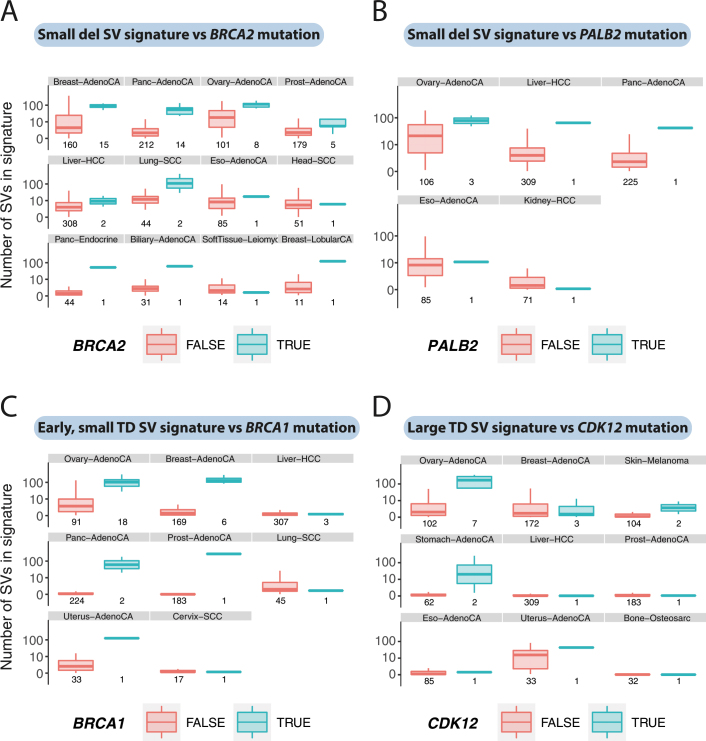

We grouped annotations of pathogenic germline variants and somatic driver mutations in DNA-repair genes across the cohort8, correlating their presence with activity of the structural-variant signatures (Fig. 6b). As previously described for breast and ovarian cancers6,29, BRCA1 mutations are significantly associated with small tandem duplication signatures, the mechanistic basis of which is increasingly well understood10. As previously described6,36, CDK12 variants predicted signatures of mid-sized-to-large tandem duplications. BRCA2 variants correlated with small deletions, as expected from previous work29, and also with the reciprocal structural-variant signature that includes chromoplexy. PALB2 variants showed the same correlations with signatures of small deletions and reciprocal structural variants as does BRCA2: PALB2 colocalizes with, stabilizes and assists BRCA2 during homologous recombination37, so we might have predicted that inactivation of either gene would lead to a similar structural-variant signature. These associations between driver mutations and structural-variant signatures were consistently evident across many types of tumour (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Consistency of associations between signatures and mutations in DNA-repair genes.

a, Box-and-whisker plots showing the number of structural variants attributed to the small-deletion signature in different types of tumour, split by BRCA2 status (BRCA2 wild type in orange; BRCA2 mutant in cyan). The box denotes the interquartile range, with the median marked as a horizontal line. The whiskers extend as far as the range or 1.5× the interquartile range, whichever is lower. Outlier patients are shown as points. There is an increase in events attributed to the small-deletion signature when BRCA2 is mutated, across multiple types of tumour (breast, pancreatic, ovarian, prostate, lung squamous and so on). b, Box-and-whisker plots as for a, showing the number of structural variants attributed to the small-deletion signature in different types of tumour, split by PALB2 status. c, Box-and-whisker plots as for a, showing the number of structural variants attributed to the early-replicating, small-tandem-duplication signature in different types of tumour, split by BRCA1 status. d, Box-and-whisker plots as for a, showing the number of structural variants attributed to the large-tandem-duplication signature in different types of tumour, split by CDK12 status.

The structural-variant signatures showed considerable heterogeneity in their activity across tumour types and among patients within a given tumour type (Supplementary Fig. 8). Tumours of the gastrointestinal tract—including colorectal and oesophageal adenocarcinomas—showed high rates of the fragile-site signature. Prostate cancer was notable for the prevalence of the chromoplexy signature, as previously reported5,20, and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung were characterized by the fold-back inversion signature.

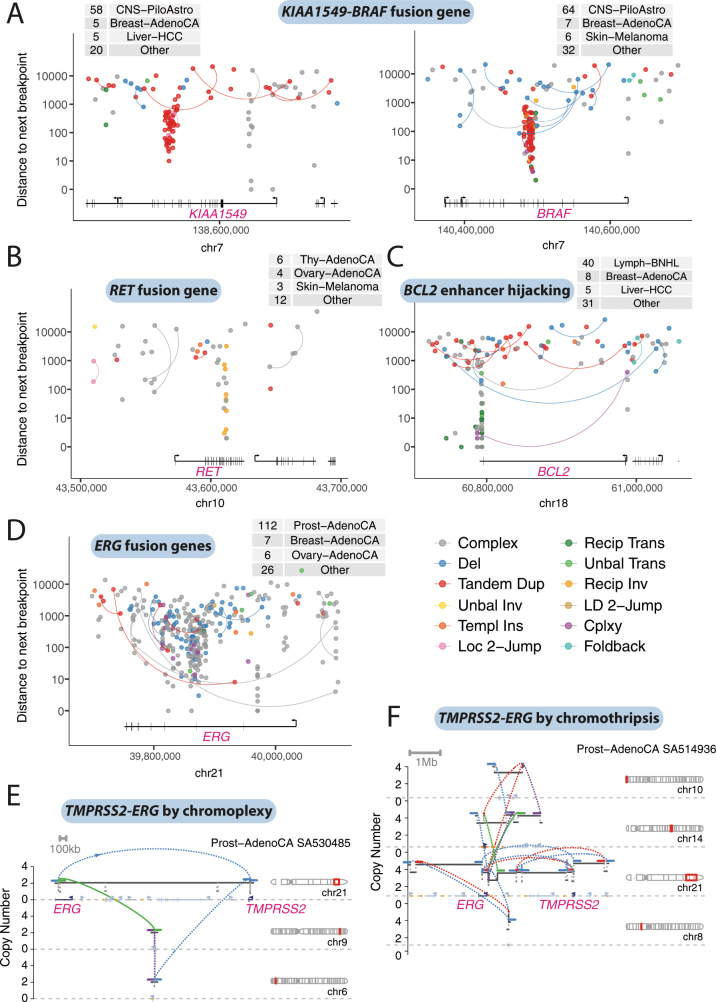

We assessed how classes of structural variant altered known cancer genes (Supplementary Table 1). Some cancer genes acquire oncogenic potential only with specific structural events, such as fusion genes or enhancer hijacking. Not surprisingly, these genes typically showed little variability in which classes of structural variant could generate such events (Extended Data Fig. 11a–c)—although there were exceptions. The TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene of prostate cancer, for example, was generated by a range of processes (including simple deletions, chromoplexy and chromothripsis), all of which are prevalent signatures in this tumour type (Extended Data Fig. 11d–f).

Extended Data Fig. 11. Patterns of structural variants causing fusion genes and enhancer hijacking.

a, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints in the genes KIAA1549 and BRAF, commonly fused together through a tandem duplication in pilocytic astrocytomas. Structural variants are coloured by classification and arranged vertically by the distance to the next breakpoint in the cohort. If the two sides of a breakpoint junction are contained within the plotting window, they are joined by a curved line. The number of samples with a breakpoint in the plotting window is annotated in the table at the top of each panel. b, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect RET, commonly fused to CCDC6 by inversion in papillary thyroid cancer. c, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect BCL2, commonly hijacked to the IGH immunoglobulin locus by translocations in B cell lymphomas. d, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect ERG, commonly fused with TMPRSS2 by deletion or more-complex events in prostate adenocarcinoma. e, Example of a TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene in a prostate adenocarcinoma created by a chromoplexy cycle. The estimated copy-number profile is shown as black horizontal segments, with structural variants shown as dotted arcs linking the edges of two copy-number segments. f, Example of a TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene in a prostate adenocarcinoma created by chromothripsis.

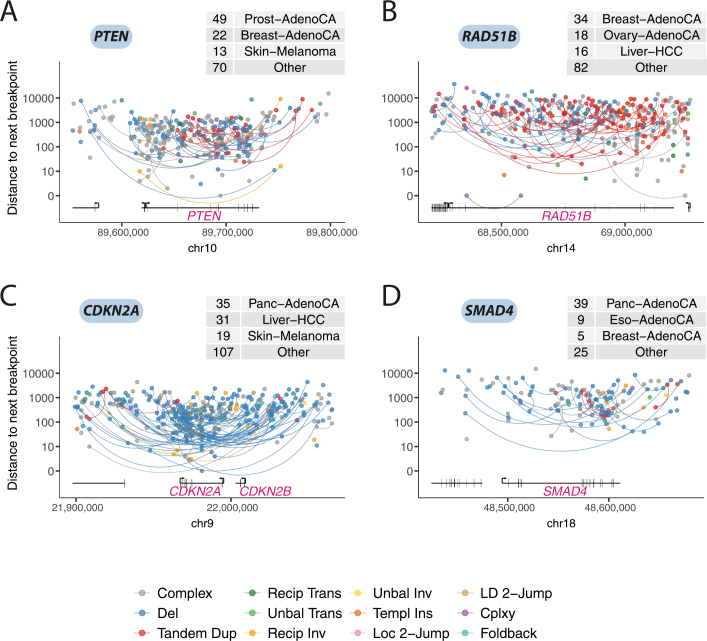

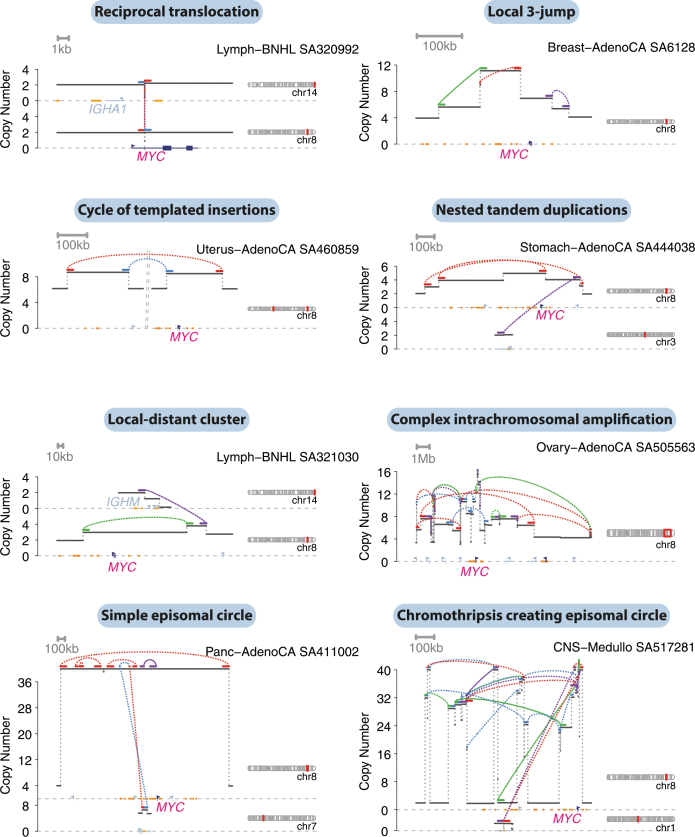

Tumour-suppressor genes and recurrently amplified genes showed more variability in which types of structural variant were observed, and these were shaped by signatures active in the relevant tumour types. For example, the tumour-suppressor genes, PTEN and RAD51B, which are commonly inactivated in breast and ovarian cancers, were often targeted by tandem duplications generating out-of-frame exon duplications (Extended Data Fig. 12a, b). By contrast, deletions were the predominant events that inactivated SMAD4 and CDKN2A, in keeping with their prevalence in cancers of the gastrointestinal tract (Extended Data Fig. 12c, d). MYC, one of the most commonly amplified genes across all types of cancer, showed considerable diversity in the mechanisms of its rearrangement: nested tandem duplications in breast cancer, translocations or chromoplexy with IGH in lymphoma, as well as chromothripsis, cycles of templated insertions, local n-jumps and local–distant clusters in other types of tumour (Extended Data Fig. 13).

Extended Data Fig. 12. Patterns of structural variants that affect selected tumour-suppressor genes.

a, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints in the gene PTEN, commonly inactivated in breast and ovarian adenocarcinomas, in which tandem-duplication signatures are frequent. Structural variants are coloured by classification and arranged vertically by the distance to the next breakpoint in the cohort. If the two sides of a breakpoint junction are contained within the plotting window, they are joined by a curved line. The number of samples with a breakpoint in the plotting window is annotated in the table at the top of each panel. b, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect RAD51B, commonly inactivated in breast and ovarian adenocarcinomas. c, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect CDKN2A, commonly inactivated in tumours of the gastrointestinal tract, in which deletion signatures are common. d, Rainfall plot of structural-variant breakpoints that affect SMAD4, commonly inactivated in tumours of the gastrointestinal tract.

Extended Data Fig. 13. Examples of structural variants increasing the copy number of MYC.

The estimated copy-number profile is shown as black horizontal segments, with structural variants shown as dotted arcs linking the edges of two copy-number segments.

Discussion

We have described the patterns and signatures of structural variation in a large cohort of uniformly analysed cancer genomes. A major grouping of patterns in structural variants that emerges from our study is one in which extra copies of genomic templates are inserted during the rearrangement process. This includes simple events such as tandem duplications, as well as a range of more-complex events with duplications and triplications that are rearranged locally as well as inserted distantly. Our signature analysis grouped a large proportion of these more-complex events together with tandem duplications, which suggests that they represent a continuum of processes that share underlying properties. A replication-based mechanism has previously been proposed to explain local two-jumps4,23,24, in which stalled replication forks or other DNA lesions cause the DNA polymerase to switch templates and continue replication in a new location. Studies in experimental models are now revealing that a wide range of mechanisms and DNA lesions can result in templated insertions: these mechanisms include tandem duplications in BRCA1 deficiency10, translocations with templated insertions caused by dysregulated strand invasion38 and distant templated insertions in the absence of replication helicases39.

Genomic instability in cancer is not a single phenomenon. Instead, many different mutational processes can act to restructure the genome and, in doing so, generate a notably flexible array of possible structures. Any given tumour draws on a subset of the available processes, shaped by the cell of origin, germline predisposition and other, unknown, factors: selection then does the rest, promoting the clone that has chanced on the structure that increases its potential for self-determination.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

A detailed description of the methods used in this paper and many additional results are described in Supplementary Information. Here, we summarize the key aspects of the analysis.

Generation of the structural-variant call set

The final set of structural variants used in this Article was generated by the Technical Working Group of the PCAWG Consortium and is described in the main PCAWG paper8. In brief, four variant callers were used to identify somatically acquired structural variants from matched tumour and germline whole genome sequencing data: SvABA (Broad pipeline), DELLY (DKFZ pipeline), BRASS (Sanger pipeline) and dRanger (Broad pipeline). These were merged into a final call set using a graph-based algorithm to identify overlapping breakpoint junctions across algorithms. Detailed visual inspection of structural-variant calls suggested that a simple approach of accepting all structural-variant calls made by two or more of the four algorithms gave the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.

Structural-variant clustering and annotation

To identify clusters of structural variants, we developed a method for grouping structural variants into clusters and footprints to allow structural and mechanistic inferences to be made systematically. In parallel, we processed the somatic copy-number data and merged it with structural-variant junctions to enable us produce rearrangement patterns from the generated structural-variant clusters and footprints. We produced normalized representations of structural-variant cluster patterns, which enable us to tabulate the number of different cluster and footprint patterns and analyse their features. Finally, we performed manual and simulation-assisted interpretation of the recurrently observed cluster and footprint patterns. The individual steps of the structural-variant classification pipeline are outlined below and detailed in the subsequent subsections: (1) computing the exact breakpoint coordinates from clipped reads; (2) removing redundant ‘segment-bypassing’ structural variants; (3) merging rearrangement breakpoints with copy-number data to yield structural-variant breakpoint-demarcated, normalized, absolute copy-number data; (4) clustering individual structural variants into structural-variant clusters and footprints; (5) heuristically refining structural-variant clusters and footprints; (6) filtering artefactual fold-back-type structural variants with insufficient support; (7) determining balanced overlapping breakpoints (this step is to distinguish very short templated insertions from mutually overlapping balanced breakpoints); and (8) computing rearrangement patterns and categories.

Distribution of structural variants across the genome

We divided the hg19 human reference genome (autosomes and chromosome X) into 3,036,315 pixels of 1 kb, and calculated a suite of metrics per pixel to summarize a variety of genome properties with potential relevance to the distribution of rearrangements, as listed in the Supplementary Information. Properties were matched as closely as possible to the tissue of origin for cancer samples from the PCAWG data. All other genome properties were held fixed across all tissues. To test for associations between structural-variant event classes and the library of genome properties, the genome property metrics were compared between real structural-variant positions (randomly choosing one side of each breakpoint junction to reduce dependence between observations) and one million uniform random positions from the callable genome space. To compare the tissue-specific properties, each random position was assigned a random tissue type, drawing from the observed tissue-type distribution in the structural-variant call set. For each genome property and each event class, the real observations were pooled amongst the random ones, and then rank-transformed and normalized on a scale from 0 to 1. Under the null hypothesis of no event-versus-property association, the ranks of the real observations would follow a uniform distribution. We tested this in each case with a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test then applied a Benjamini–Yekutieli correction for false-discovery rate across the entire suite of tests and set the threshold for significance reporting at 0.01.

Structural-variant-signature analysis

We used two algorithms for extracting structural-variant signatures. Both used the same input files, comprising a matrix of counts per patient (across all patients) of structural-variant clusters falling into a number of mutually exclusive categories. These categories included the major classes of structural variants, with the more-common events (deletions, tandem duplications and inversions) split by size and/or replication timing. The two algorithms that were used for extracting the signatures were (1) a hierarchical Dirichlet process and (2) non-negative matrix factorization. Further details on the implementation of these algorithms are available in the Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41586-019-1913-9.

Supplementary information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Results, References and a list of participants in ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium.

Supplementary Table 1: Counts of patients with SVs in different classes affecting genes in the Cancer Gene Census.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, Pediatric Low-Grade Astrocytoma Fund and the Fund for Innovation in Cancer Informatics. P.J.C. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Clinical Fellow (WT088340MA). We acknowledge the contributions of the many clinical networks across ICGC and TCGA, which provided samples and data to the PCAWG Consortium, and the contributions of the Technical Working Group and the Germline Working Group of the PCAWG Consortium for the collation, realignment and harmonized variant-calling of the cancer genomes used in this study. We thank the patients and their families for their participation in the individual ICGC and TCGA projects.

Extended data figures and tables

Author contributions

Y.L., N.D.R., J.A.W. and O.S. contributed equally to this manuscript, undertaking evaluation and curation of structural-variant calls, merging structural-variant call sets from four separate algorithms into a final dataset. Y.L. performed the clustering and classification of structural variants, and identified patterns of rearrangement, with assistance from N.D.R. and M.I. N.D.R. performed the analysis of structural-variant signatures with assistance from Y.L. N.D.R., J.A.W. and O.S. analysed the distribution of structural variants across the genome, with input from J.E.H., E.K., K.K. and S.E.S. S.W. and J.O.K. contributed to the analysis of how germline variants influenced signatures of structural variants. J.W., R.B. and P.J.C. jointly oversaw the project, assisted with data interpretation and wrote the paper, with input from all authors.

Data availability

Somatic and germline variant calls, mutational signatures, subclonal reconstructions, transcript abundance, splice calls and other core data generated by the ICGC/TCGA PCAWG Consortium are described in an accompanying Article8 and are available for download at https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/PCAWG. Additional information on accessing the data, including raw read files, can be found at https://docs.icgc.org/pcawg/data/. In accordance with the data access policies of the ICGC and TCGA projects, most molecular, clinical and specimen data are in an open tier that does not require access approval. To access information that could potentially identify participants, such as germline alleles and the underlying sequencing data, researchers will need to apply to the TCGA data access committee via dbGaP (https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/aa/wga.cgi?page=login) for access to the TCGA portion of the dataset, and to the ICGC data access compliance office (http://icgc.org/daco) for the ICGC portion of the dataset. In addition, to access somatic single-nucleotide variants derived from TCGA donors, researchers will also need to obtain dbGaP authorization.

Code availability

The core computational pipelines used by the PCAWG Consortium for alignment, quality control and variant calling are available to the public at https://dockstore.org/search?search=pcawg under the GNU General Public License v.3.0, which allows for reuse and distribution. These are described in detail in an accompanying Article8. The code for grouping structural variants into structural-variant clusters and footprints is available at https://github.com/cancerit/ClusterSV/ (version 1.0). The code for simulating rearrangements can be found at https://github.com/cancerit/SimSvGenomes (version 1.0). The code for sampling from the hierarchical Dirichlet process for identification of mutational signatures is implemented as an R package at https://github.com/nicolaroberts/hdp (version 0.1.1).

Competing interests

R.B. owns equity in Ampressa Therapeutics; M.M. is the scientific advisory board chair of—and consultant for— OrigiMed, and receives research funding from Bayer and Ono Pharma, and patent royalties from LabCorp.; J.W. is a consultant for Nference Inc.; C.-Z.Z. is a cofounder and equity holder of Pillar Biosciences, a for-profit company specializing in the development of targeted sequencing assays.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature thanks Don Conrad, Ben Lehner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yilong Li, Nicola D. Roberts, Jeremiah A. Wala, Ofer Shapira

A list of members and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper

A list of members and their affiliations appears online

Change history

1/25/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41586-022-05597-x

Contributor Information

Joachim Weischenfeldt, Email: joachim.weischenfeldt@bric.ku.dk.

Rameen Beroukhim, Email: rameen_beroukhim@dfci.harvard.edu.

Peter J. Campbell, Email: pc8@sanger.ac.uk

PCAWG Structural Variation Working Group:

Kadir C. Akdemir, Eva G. Alvarez, Adrian Baez-Ortega, Rameen Beroukhim, Paul C. Boutros, David D. L. Bowtell, Benedikt Brors, Kathleen H. Burns, Peter J. Campbell, Kin Chan, Ken Chen, Isidro Cortés-Ciriano, Ana Dueso-Barroso, Andrew J. Dunford, Paul A. Edwards, Xavier Estivill, Dariush Etemadmoghadam, Lars Feuerbach, J. Lynn Fink, Milana Frenkel-Morgenstern, Dale W. Garsed, Mark Gerstein, Dmitry A. Gordenin, David Haan, James E. Haber, Julian M. Hess, Barbara Hutter, Marcin Imielinski, David T. W. Jones, Young Seok Ju, Marat D. Kazanov, Leszek J. Klimczak, Youngil Koh, Jan O. Korbel, Kiran Kumar, Eunjung Alice Lee, Jake June-Koo Lee, Yilong Li, Andy G. Lynch, Geoff Macintyre, Florian Markowetz, Iñigo Martincorena, Alexander Martinez-Fundichely, Matthew Meyerson, Satoru Miyano, Hidewaki Nakagawa, Fabio C. P. Navarro, Stephan Ossowski, Peter J. Park, John V. Pearson, Montserrat Puiggròs, Karsten Rippe, Nicola D. Roberts, Steven A. Roberts, Bernardo Rodriguez-Martin, Steven E. Schumacher, Ralph Scully, Mark Shackleton, Nikos Sidiropoulos, Lina Sieverling, Chip Stewart, David Torrents, Jose M. C. Tubio, Izar Villasante, Nicola Waddell, Jeremiah A. Wala, Joachim Weischenfeldt, Lixing Yang, Xiaotong Yao, Sung-Soo Yoon, Jorge Zamora, and Cheng-Zhong Zhang

PCAWG Consortium: