Abstract

Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer (HLRCC) is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by heterozygous pathogenic germline variants in the fumarate hydratase (FH) gene. It is characterized by cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas and an increased risk of developing renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which is usually adult-onset. HLRCC-related RCC tends to be aggressive and can metastasize even when the primary tumor is small. Data on children and adolescents are scarce. Herein, we report two patients from unrelated Dutch families, with HLRCC-related RCC at the ages of 15 and 18 years, and a third patient with an FH mutation and complex renal cysts at the age of 13. Both RCC’s were localized and successfully resected, and careful MRI surveillance was initiated to monitor the renal cysts. One of the patients with RCC subsequently developed an ovarian Leydig cell tumor. A review of the literature identified 10 previously reported cases of HLRCC-related RCC in patients aged younger than 20 years, five of them presenting with metastatic disease. These data emphasize the importance of recognizing HLRCC in young patients to enable early detection of RCC, albeit rare. They support the recommendations from the 2014 consensus guideline, in which genetic testing for FH mutations, and renal MRI surveillance, is advised for HLRCC family members from the age of 8–10 years onwards.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10689-019-00155-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hereditary leiomyomatosis, Fumarate hydratase, Renal cell carcinoma, Children, Adolescents, FH mutation, HLRCC

Introduction

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by heterozygous germline variants in the fumarate hydratase (FH) gene, associated with an increased risk of developing renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

The first report describing a family with HLRCC was published in Finland in 2001, and over 300 affected families from various countries have been described since [1–4]. Other clinical manifestations of HLRCC include multiple cutaneous leiomyomas in 73–100% of FH mutations carriers and uterine leiomyomas in ± 75% of female carriers [4–6]. Additionally, germline mutations in the FH gene have been identified in a small percentage of patients with paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas [7, 8].

The FH gene, located on chromosome region 1q42.1, is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes the enzyme fumarate hydratase (fumarase), which plays a role in both the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in mitochondria, as well as the response to DNA double strand breaks in the nucleus [3, 9]. Somatic inactivation of the second allele can be demonstrated in most, but not all, HLRCC-related tumors [2, 10–12]. Biallelic germline mutations are rare and cause a syndrome known as fumarase deficiency, characterized by early onset, severe encephalopathy [5]. In patients with fumarase deficiency, mutations are usually missense or in-frame duplications that do not necessarily result in complete loss of enzyme activity [13]. More than 200 distinct variants spread over the entire coding region of the FH gene have been published in the Leiden Open (source) Variation Database system (LOVD) [13] and so far, a clear correlation between the type or location of the FH mutation and cancer risk has not been observed [5].

The absolute risk of developing RCC is estimated to be 10–15%, with a median age of onset of 40–41 years [4, 14]. RCC can be the first manifestation of HLRCC. Histologically, loss of staining for FH and positive staining for 2-succino-cysteine (2SC), which accumulates in the setting of FH deficiency, can support the diagnosis of HLRCC-related RCC [14, 15].

In adults, HLRCC-related RCC is known to be aggressive and can metastasize even when the primary tumor is small. Data on children and adolescents are scarce. We herein report three young patients from unrelated Dutch families, aged 15, 18 and 13 years respectively, as well as the results of a systematic literature review on HLRCC-related RCC in patients younger than 20 years. This review contributes to existing recommendations for genetic testing, tumor surveillance and resection in children and adolescents.

Methods

Patients were evaluated at the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology (case 1 and 3) and Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen (case 2). Genetic, radiological and histopathological studies were reviewed. All patients as well as the parents in case 1 and 3, gave informed consent for inclusion of their clinical data in this manuscript.

For the literature review, databases of PubMed and Embase were searched for HLRCC-related renal tumors occurring in patients < 20 years (Supplementary Table 1). After removing duplicates, the search yielded 1221 articles (Supplementary Fig. 1). Any report (manuscript or conference abstract), written in English, Dutch, German, French or Spanish, describing a HLRCC-related renal tumor in a patient younger than 20 years of age, was eligible for inclusion. After title/abstract screening, a total of 86 reports were eligible for full text screening, during which 77 articles were excluded based on full text not being available, only including patients ≥ 20 years old, only reviewing or describing previously reported patients, or lack of germline genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis of HLRCC.

Case presentation

Case 1

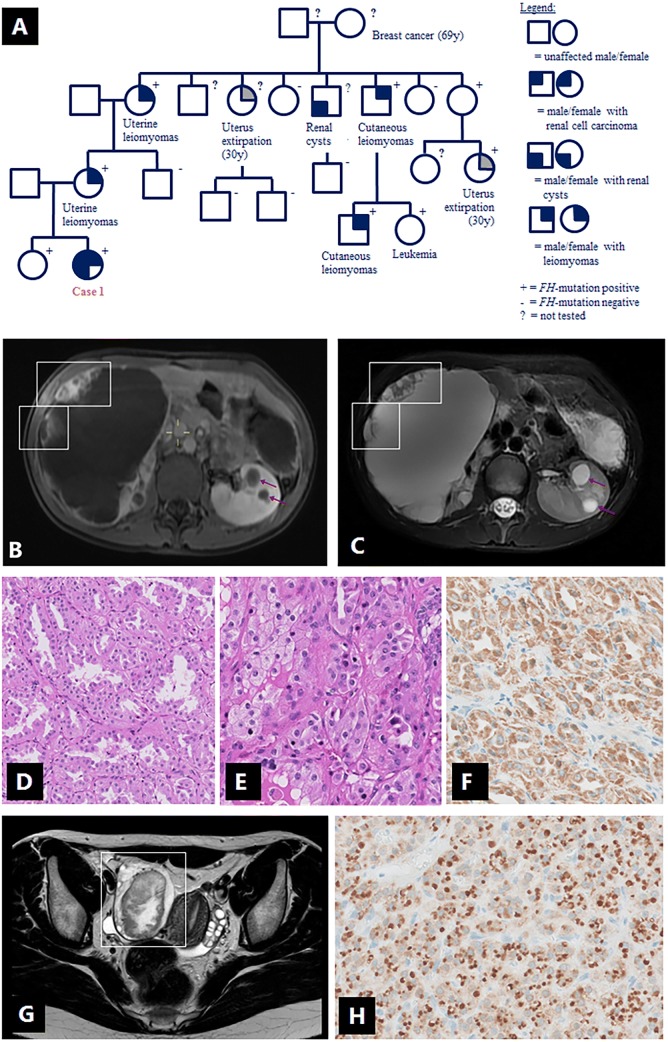

A 15-year old female presented with a large right-sided abdominal mass. Her family history included uterine and cutaneous leiomyomas and a confirmed FH mutation in mother’s family (Fig. 1a). Physical examination revealed small, cutaneous lesions of the lower legs, suggestive for leiomyomas. On MRI using a customized HLRCC-protocol (Table 1), the mass was mostly cystic with peripheral solid nodules (Fig. 1b, c). The nodules showed strong enhancement after contrast administration and restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). In the left kidney, multiple cystic lesions were observed without solid components. Brain MRI and total body FDG-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) did not reveal signs of metastatic spread. Right-sided nephrectomy revealed an RCC with a maximum diameter of 20 cm (T2N0M0, four lymph nodes sampled), with tumor cells lining the cysts. There was no spread beyond the kidney and resection margins were free of tumor. Solid areas consisted of vital epithelial tumor with a predominantly tubular, partially papillary growth pattern of strongly eosinophilic cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia (Fig. 1d, e) and diffuse 2SC staining (Fig. 1f). Prominent nucleoli were seen only in rare areas with papillary architecture, without perinucleolar halos. Germline genetic testing by MLPA confirmed the presence of the familial heterozygous deletion of the FH gene (c.(?_1)_(*1_?)del) in the patient and her 18-year old healthy sister, a deletion which has been previously reported in other patients with HLRCC [3, 6, 16–18]. The left kidney is monitored with MRI’s at 3 and 6 months after diagnosis, then every 6 months for 3 years, and yearly thereafter. Whereas the kidney appeared unchanged, the patient developed an ovarian lesion (Fig. 1g) after a follow-up of 30 months, at the age of 18, which was successfully resected and histologically characterized as a Leydig cell tumor; a well-demarcated lesion with uniform cells showing large, round nuclei, prominent nucleoli and lack of necrosis, nuclear atypia or mitotic figures. The tumor showed diffuse 2SC staining (Fig. 1h). Whole exome sequencing (Illumina NovaSeq platform) was performed on the Leydig cell tumor, but a second hit in the FH gene was not identified.

Fig. 1.

Case 1 (female, 15 years, renal cell carcinoma and Leydig cell tumor): a family pedigree; b–c contrast-enhanced T1W-MRI (b) and abdominal T2W-MRI (c) showing large right-sided kidney mass, which is mostly cystic with peripheral solid nodules (boxes). In the left kidney, multiple cystic lesions (arrows) are observed without solid components; d–f histology of the renal tumor: vital epithelial tumor with a predominantly tubular, partially papillary growth pattern (d) of strongly eosinophilic cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia (e), and diffuse 2SC staining (f). g T2W-MRI of the pelvic region showing a right-sided ovarian lesion (box) with both solid and cystic components. h Ovarian Leydig cell tumor showing diffuse 2SC staining

Table 1.

Scan parameters and surveillance schedule for renal MRI surveillance in patients with HLRCC

| Parameter | T2w-fat suppression | 3D-T2 | DWI | T1 pre/post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse sequence | 2-D MultiVane with spectral fat saturation | 3-D turbo spin-echo with variable flip angle | 2-D single-shot spin-echo with spectral fat saturation | 2-D ultrafast spoiled gradient echo with fat suppression |

| Repetition time (ms) | 2450 | 449 | 1611 | 3,89 |

| Echo time (ms) | 100 | 90 | 79 | 1,82 |

| Flip angle (degree) | 90 | – | 90 | 10 |

| Slice orientation | axial | axial | axial | axial |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 3 | 0.9–1.15 | 5 | 4 |

| Slice gap (mm) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Echotrain length | 30 | 85 | 1 | 1 |

| Field of view (mm2) | 400 | 400 | 450 | 380 |

| B-values (s/mm2) | – | – | 0, 150, 1000 | – |

Case 2

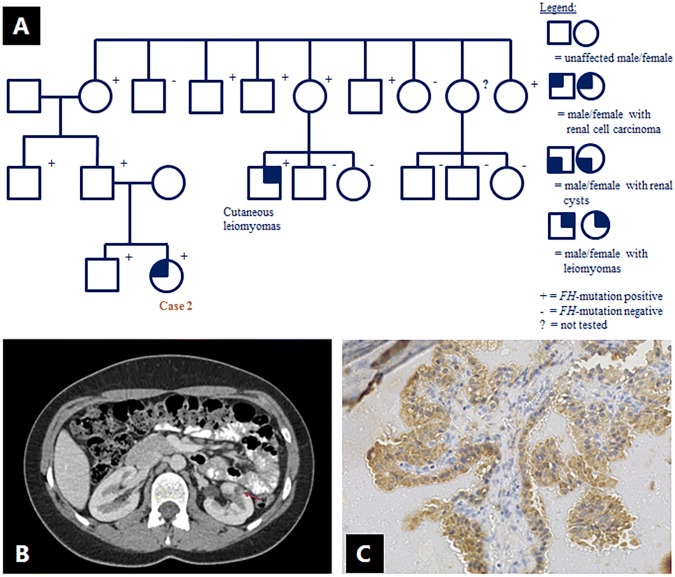

An 18-year old female, carrier of an FH mutation (c.1330delA; p.Arg444 fs; NM_000143.3), was referred for a suspect lesion in the left kidney, observed on renal MRI surveillance. The mutation was derived from her asymptomatic father and had been previously identified in a distant adult cousin with cutaneous leiomyomas (Fig. 2a). This mutation has not been previously reported. Subsequent CT-imaging with contrast administration showed a 9 mm cystic lesion, with an area of increased density suspect for nodular enhancement (Fig. 2b). A chest X-ray did not reveal signs of lung metastases. A partial nephrectomy was performed; the resected cyst showed focal papillary proliferations with a lining of atypical epithelial cells with some prominent nucleoli. The nucleoli were not significantly enlarged, strongly eosinophilic or surrounded by halos. No necrosis or strong mitotic activity were present. 2SC immunohistochemical staining was positive (Fig. 2c), and the lesion was characterized as an early stage of HLRCC-related RCC. A second hit analysis was not performed. The patient is doing well after a follow-up of 45 months.

Fig. 2.

Case 2 (female, 18 years, renal cell carcinoma): a family pedigree; data are missing on the presence of leiomyomas in FH mutation carriers; b abdominal CT after contrast administration, showing a 9 mm cystic lesion in the left kidney, with an area of increased density (arrow) suspect for nodular enhancement. c Tumor cells showing diffuse 2SC staining

Case 3

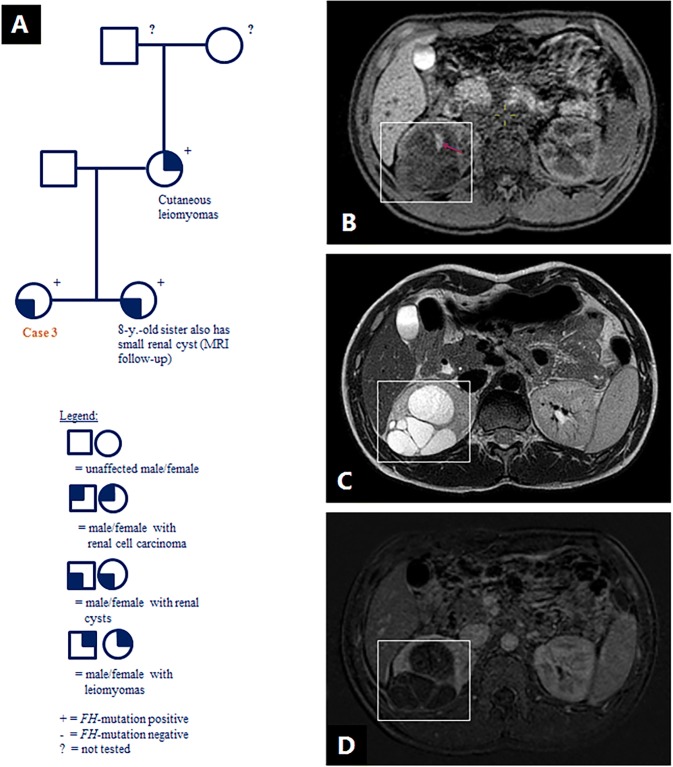

A 13-year old female and her 8-year old sister were referred for ultrasound screening because of a recently confirmed FH mutation (c.1210G>T; p.Glu404*; NM_000143.3). The FH mutation was initially detected in the girls’ mother who had cutaneous leiomyomas (Fig. 3a), and this specific mutation was previously published in a case series [19]. In the 13-year old girl, the ultrasound identified two lesions in the right kidney which required further assessment, and the suspicion of RCC was discussed with the family. Subsequent MRI demonstrated two complex cystic lesions with variable hemorrhagic content in the right kidney with a maximum diameter of 7.1 cm and 2.2 cm respectively (Fig. 3b–d). No nodular enhancement was detected. An international review of the MRI scans agreed with this interpretation. After 18 months follow-up, the cysts had grown in size but no solid components appeared, with MRI’s performed at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months after the initial referral.

Fig. 3.

Case 3 (female, 13 years, complex renal cysts): a family pedigree; b–d abdominal T1 MRI (b) showing multilocular cysts (box) in the right kidney with area suspect for hemorrhagic content (arrow). Abdominal T2W MRI (c) and subtraction MRI (d) showing no nodular enhancement

Literature review

The literature review revealed 10 additional patients with HLRCC-related RCC diagnosed between 10 and 18 years of age (Table 2) [12, 18, 20–25]. Additionally, a Wilms tumor was identified in a 2-year-old female patient who later developed cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas at the age of 25. She was confirmed to carry a germline c.1189G>A (p.Gly397Arg; NM_000143.3) mutation in the FH gene. Since no tissue from the Wilms tumor was available, FH expression could not be evaluated and the causal relationship remains uncertain [26]. This particular mutation has been described in other patients with HLRCC, including the 11-year old patient with HLRCC-related RCC in Table 2 [22].

Table 2.

HLRCC-related renal cell carcinoma (RCC) before the age of 20 years (confirmed FH mutation)

| # | References | FH mutation | Age | Sex | Presentation | Histology | Disease stage | Outcome (FU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alam et al. [17]a | n.a. | 16 | F | Symptomatic | Collecting duct tumour | Metastatic | Died (2 years) |

| 2 | Merino et al. [12]a | n.a. | 17 | F | NA | HLRCC-associated RCC | Localized | NA |

| 3 | 18 | F | NA | Metastatic | NA | |||

| 4 | Al Refae et al. [21]a |

c.1293del (exon 8) |

17 | M | Symptomatic | Papillary type 2 RCC | Metastatic | Died (15 months) |

| 5 | Alrashdi et al. [22]a, b |

c.1189G>A (exon 8) |

11 | M | Surveillance | Papillary type 2 RCC | Localized | NED (3 years) |

| 6 | Gardie et al. [18]a, c |

c.1123del (exon 8) |

17 | M | NA | Papillary type 2 RCC | Metastatic | Died (2 years) |

| 7 | Van Spaendonck-Zwarts et al. [23]a |

c.1002T>G (exon 7) |

18 | F | Symptomatic | Papillary type 2 RCC, focally showing prominent nucleoli surrounded by a clear halo | Metastatic | Died (8 months) |

| 8 |

Nix et al. [24]d (meeting abstract) |

n.a. | 10 | NA | NA | RCC, not specified | NA | NA |

| 9 |

Toubaji et al. [25] (meeting abstract) |

n.a. | 18 | NA | NA | RCC, not specified | NA | NA |

| 10 | Bhola et al. [27] |

c.1430-1437dup (exon 10) |

15 | F | Symptomatic | Tubulo-papillary carcinoma | NA | NA |

| 11 | This report | Whole gene deletion | 15 | F | Symptomatic | HLRCC-associated RCC | Localized | Second tumor (Leydig cell tumor), 2 years after initial diagnosis |

| 12 | This report |

c.1210G>T (exon 8) |

18 | F | Surveillance | HLRCC-associated RCC | Localized | NED (4 years) |

Mutations are described using NM_000143.3

FU follow-up time since diagnosis, NED no evidence of disease, n.a. not available

aPreviously included in literature review by Van Spaendonck-Zwarts et al. [23]

bFollow-up data reported in Van Spaendonck-Zwarts et al. [23]

cFollow-up data reported in Van Spaendonck-Zwarts et al. [23] and Wong et al. [28]

dThis 10-year old patient is also referred to in Menko et al. [14] (describes personal communication with Dr. Linehan)

In two of the described young patients with RCC, histology was not further specified [24, 25]. Among the other patients, two tumors were described as HLRCC-associated RCC with a variety of histological patterns [12], whereas four tumors were described as papillary type 2 RCC [18, 21–23], one as tubulopapillary RCC [27] and one as a collecting duct tumor [20]. Although most patients were symptomatic at presentation, an 11-year old male patient was diagnosed with localized RCC at his first surveillance visit [22]. Overall, five out of ten patients presented with metastatic disease [12, 18, 20, 21, 23], two had localized disease [12, 22], and disease stage was not reported for the remaining three. Follow-up data were available of five patients, of whom four died within 2 years after diagnosis [20, 21, 23, 28]. The one patient with localized disease and follow-up data, showed no evidence of disease after 3 years [22]. The exact mutation was specified in 5/10 cases, including single nucleotide deletions in exon 8 in two patients [21, 28], a missense mutation in exon 8 [22], a missense mutation in exon 7 [23], and a duplication in exon 10 [27].

Discussion

Including the two new cases in this report, a total of 12 RCC’s have been reported to date in FH mutation carriers younger than 20 years of age. Its aggressive nature, as illustrated by our literature review, emphasizes the importance of early genetic testing and surveillance.

Recently, a large, national series of French patients with HLRCC was published, in which 34 (19%) out of 182 FH mutation carriers developed RCC [4]. In this study, FH mutation carriers were identified through the two national laboratories accredited for FH germline testing. It is remarkable that none of the tumors in the French cohort occurred before the age of 20 years, illustrating that this early manifestation of HLRCC is rare and our literature review is likely to be influenced by a publication bias. Nevertheless, it may well be that FH germline testing is not always performed when RCC occurs in young patients from families that are not yet diagnosed with HLRCC. Notably, these patients may not yet have developed the typical clinical features of HLRCC.

In these patients the young age at diagnosis of RCC and characteristics of the tumor can trigger awareness for an underlying syndrome. Tumor characteristics typically associated with HLRCC, include papillary type 2 RCC and prominent nucleoli surrounded by a clear halo [12]. Yet, a recent review on histopathological features of FH-deficient RCC, concluded that a complex architecture with multiple histological patterns was more characteristic than the presence of perinucleolar halos. Moreover, histological patterns other than papillary type 2 RCC predominated in 40% of cases [29]. Interestingly, focused genetic testing in 212 RCC’s registered in the Children’s Oncology Group, revealed three FH-deficient RCC’s that were initially classified as RCC-NOS, in patients aged 17–18 years [30]. Since germline genetic data are lacking for these patients, a diagnosis of HLRCC could not be confirmed. Yet, these studies demonstrate the value of FH/2SC-immunostaining and genetic testing in unclassified or morphologically complex RCC, in both children and adults. Currently, HLRCC-associated RCC is recognized as a separate category in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of renal tumors [31].

Leydig cell tumors, as identified in case 1, have been previously described in three patients with HLRCC, including two males with testicular Leydig cell tumors and a female with bilateral steroid cell tumors and metastatic RCC [32, 33]. With this fourth patient, we provide further evidence for an association between HLRCC and Leydig cell tumors. The three previously reported patients each had a different missense mutation in FH, and in contrast to the Leydig cell tumor of case 1, loss of the wild-type FH allele was demonstrated in the two testicular tumors [31]. Immunostaining for FH or 2SC was not performed in the previously reported cases, while in our patient, both the RCC and the Leydig cell tumor showed 2SC positivity, as expected in FH-deficient tumors.

In the past, in The Netherlands, it was advised to start genetic testing of HLRCC family members at the age of 20 years, but this changed based on evidence of early-onset RCC in this syndrome, including an 18-year old Dutch female from a known HLRCC family who presented with metastatic RCC and died 8 months after diagnosis [23]. Five out of the 12 young patients in our case series and literature review, presented with symptoms, of whom three died of disease [20, 21, 23, 27]. International recommendations for genetic testing and renal tumor surveillance were published in a 2014 consensus guideline, following discussions during the Fifth Symposium on Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome and Second Symposium on HLRCC [14]. Based on the report of a 10-year old patient [14, 24], the guideline recommends to offer FH mutation testing to children of affected families from the age of 8–10 years onwards, and if positive to start annual renal MRI screening (Box 1) [14, 34].

Box 1

| Recommended schedule for renal surveillance in FH mutation carriers | |

|---|---|

| Yearly MRI scans from the age of 8–10 years onwards | |

| If renal cysts are detected, closer monitoring is indicated: | |

| 1st year: at 3, 6 and 12 months after detection of cysts, if no solid nodules appear: | |

| 2nd–4th year: every 6 months, if no solid nodules appear: | |

| 5th year and onwards: yearly MRI scans | |

| If solid nodules are detected, perform brain MRI and total body FDG-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for staging (repeat 1 × after 3 months) | |

| References: Menko et al. [14] and personal communication with Dr. W.M. Linehan |

MRI is preferred over abdominal ultrasound, because of the low sensitivity of ultrasound to detect small lesions [14]. MRI is also considered superior to CT-imaging because radiation is avoided, which is particularly relevant in this young age category, and because of a better soft tissue resolution to identify small nodules that may be present in cyst walls. A specific HLRCC MRI-protocol (Table 1) is recommended, using 1–3 mm slices through the kidneys. If solid lesions are detected, a surgical resection with wide surgical margins is warranted, independent of the size of the lesions, unlike other hereditary renal cancer syndromes where surgical intervention is only recommended for tumors that exceed 3 cm [14].

It is unclear to what extent renal cysts have the potential to undergo malignant transformation. In 2006, Lehtonen et al. observed a higher prevalence of renal cysts in FH mutation carriers compared to the general population, but they did not find RCC to be more frequent in FH mutation carriers with renal cysts, compared to those without renal cysts [35]. Since then, three reports have been published suggesting that renal cysts may represent a potential preneoplastic lesion of the HLRCC-related renal cell carcinoma, based on the presence of atypical cells [12, 36] or 2SC uptake [37] in the lining of resected cysts. Therefore, we recommend to intensify surveillance if renal cysts are detected in FH mutation carriers, using shorter intervals between scans (Box 1).

A potential downside of early surveillance is the anxiety it may cause to patients and their families, particularly when a suspicious lesion requires further assessment, as illustrated by case 3 in this report. The risk and benefit of surveillance needs to be balanced in individual cases, in fair communication with the parents (shared decision making), and requires referral to expert centers with multidisciplinary teams.

Overall, our findings suggest that the incidence of HLRCC-related RCC is low but not negligible in patients younger than 20 years of age, emphasizing the importance of early genetic testing and renal surveillance in HLRCC family members. These data support the recommendations from the 2014 consensus guideline on HLRCC, in which genetic testing for FH mutations, and renal MRI surveillance, is advised from the age of 8–10 years onwards.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. A. Bex, Dr. W.M. Linehan and Dr. A.A. Malayeri for their expert advice on case 1 and 3, and Dr. W.M. Linehan and Dr. A.A. Malayeri for sharing their MRI protocol and reviewing the MRI scans.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lehtonen HJ. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: update on clinical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer. 2011;10(2):397–411. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(6):3387–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051633798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomlinson IP, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, et al. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;30(4):406–410. doi: 10.1038/ng849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller M, Ferlicot S, Guillaud-Bataille M, et al. Reassessing the clinical spectrum associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome in French FH mutation carriers. Clin Genet. 2017;92(6):606–615. doi: 10.1111/cge.13014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pithukpakorn M, Toro JR, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smit DL, Mensenkamp AR, Badeloe S, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families referred for fumarate hydratase germline mutation analysis. Clin Genet. 2011;79(1):49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro-Vega LJ, Buffet A, De Cubas AA, et al. Germline mutations in FH confer predisposition to malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(9):2440–2446. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark GR, Sciacovelli M, Gaude E, et al. Germline FH mutations presenting with pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):E2046–2050. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulkowski PL, Sundaram RK, Oeck S, et al. Krebs-cycle-deficient hereditary cancer syndromes are defined by defects in homologous-recombination DNA repair. Nat Genet. 2018;50(8):1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiuru M, Launonen V, Hietala M, et al. Familial cutaneous leiomyomatosis is a two-hit condition associated with renal cell cancer of characteristic histopathology. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(3):825–829. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61757-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz-Ortega J, Vocke C, Stratton P, Linehan WM, Merino MJ. Morphologic and molecular characteristics of uterine leiomyomas in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(1):74–80. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825ec16f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto P, Linehan WM. The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(10):1578–1585. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804375b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayley JP, Launonen V, Tomlinson IP. The FH mutation database: an online database of fumarate hydratase mutations involved in the MCUL (HLRCC) tumor syndrome and congenital fumarase deficiency. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13(4):637–644. doi: 10.1007/s10689-014-9735-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardella C, El-Bahrawy M, Frizzell N, et al. Aberrant succination of proteins in fumarate hydratase-deficient mice and HLRCC patients is a robust biomarker of mutation status. J Pathol. 2011;225(1):4–11. doi: 10.1002/path.2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Wortham NC, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of FH mutations in multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer, and fumarate hydratase deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(11):1241–1252. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam NA, Olpin S, Leigh IM. Fumarate hydratase mutations and predisposition to cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas and renal cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardie B, Remenieras A, Kattygnarath D, et al. Novel FH mutations in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) and patients with isolated type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 2011;48(4):226–234. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badeloe S, van Geel M, van Steensel MA, et al. Diffuse and segmental variants of cutaneous leiomyomatosis: novel mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene and review of the literature. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15(9):735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al. Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(2):199–206. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al Refae M, Wong N, Patenaude F, Begin LR, Foulkes WD. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: an unusual and aggressive form of hereditary renal carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(4):256–261. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alrashdi I, Levine S, Paterson J, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma: very early diagnosis of renal cancer in a paediatric patient. Fam Cancer. 2010;9(2):239–243. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Badeloe S, Oosting SF, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer presenting as metastatic kidney cancer at 18 years of age: implications for surveillance. Fam Cancer. 2012;11(1):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nix J, Shuch B, Chen V, et al. Clinical features and management of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) J Urol. 2012;187(4):e810. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toubaji A, Al-Ahmadie HA, Fine SW, et al. Clinicopathologic features of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) encountered as sporadic kidney cancer. Lab Invest. 2013;93:252A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badeloe S, van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Steensel MA, et al. Wilms tumour as a possible early manifestation of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer? Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(3):707–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhola PT, Gilpin C, Smith A, Graham GE. A retrospective review of 48 individuals, including 12 families, molecularly diagnosed with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) Fam Cancer. 2018;17(4):615–620. doi: 10.1007/s10689-018-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong MH, Tan CS, Lee SC, et al. Potential genetic anticipation in hereditary leiomyomatosis-renal cell cancer (HLRCC) Fam Cancer. 2014;13(2):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s10689-014-9703-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller M, Guillaud-Bataille M, Salleron J, et al. Pattern multiplicity and fumarate hydratase (FH)/S-(2-succino)-cysteine (2SC) staining but not eosinophilic nucleoli with perinucleolar halos differentiate hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma-associated renal cell carcinomas from kidney tumors without FH gene alteration. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(6):974–983. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cajaiba MM, Dyer LM, Geller JI, et al. The classification of pediatric and young adult renal cell carcinomas registered on the children’s oncology group (COG) protocol AREN03B2 after focused genetic testing. Cancer. 2018;124(16):3381–3389. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carvajal-Carmona LG, Alam NA, Pollard PJ, et al. Adult leydig cell tumors of the testis caused by germline fumarate hydratase mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):3071–3075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora R, Eble JN, Pierce HH, et al. Bilateral ovarian steroid cell tumours and massive macronodular adrenocortical disease in a patient with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome. Pathology. 2012;44(4):360–363. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e328353bf5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:253–260. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S42097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehtonen HJ, Kiuru M, Ylisaukko-Oja SK, et al. Increased risk of cancer in patients with fumarate hydratase germline mutation. J Med Genet. 2006;43(6):523–526. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghosh A, Merino MJ, Linehan MW. Are cysts the precancerous lesion in HLRCC? The morphologic spectrum of premalignant lesions and associated molecular changes in hereditary renal cell carcinoma: their clinical significance. Lab Invest. 2013;93:212A. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ristau BT, Kamat SN, Tarin TV. Abnormal cystic tumor in a patient with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome: evidence of a precursor lesion? Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:303872. doi: 10.1155/2015/303872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.